The Breakthrough That Changes Everything

Picture this: downloading an entire weekend's worth of movies in seconds. Not on fiber. Not on broadband. Over the air.

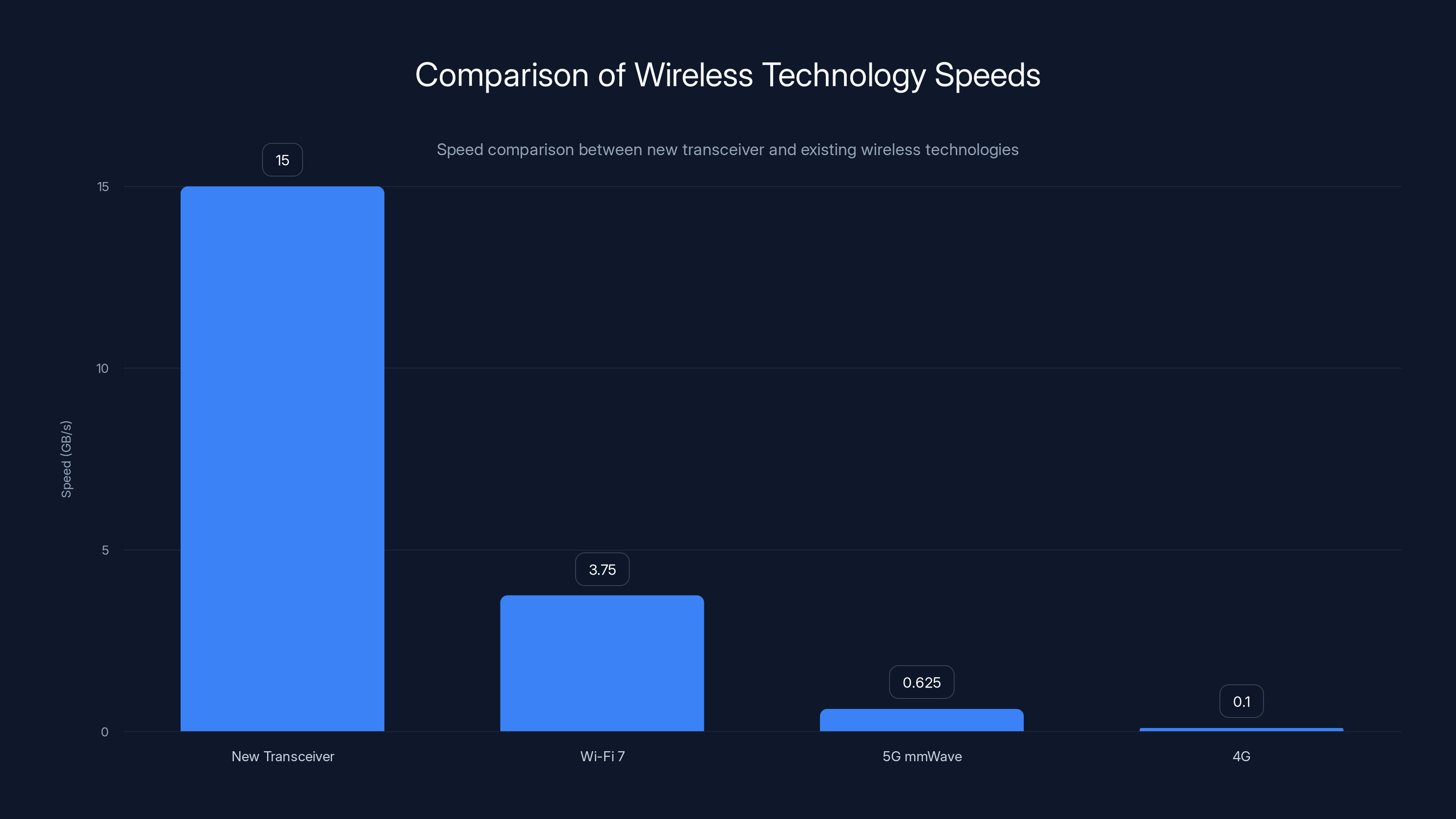

Researchers at the University of California, Irvine just demonstrated a wireless transceiver that achieves something most engineers thought would take another decade to crack. We're talking about data rates of 15 gigabytes per second, or 120 gigabits per second if you prefer the technical units. That's not a typo. That's not theoretical. That's operating hardware, right now, under practical conditions.

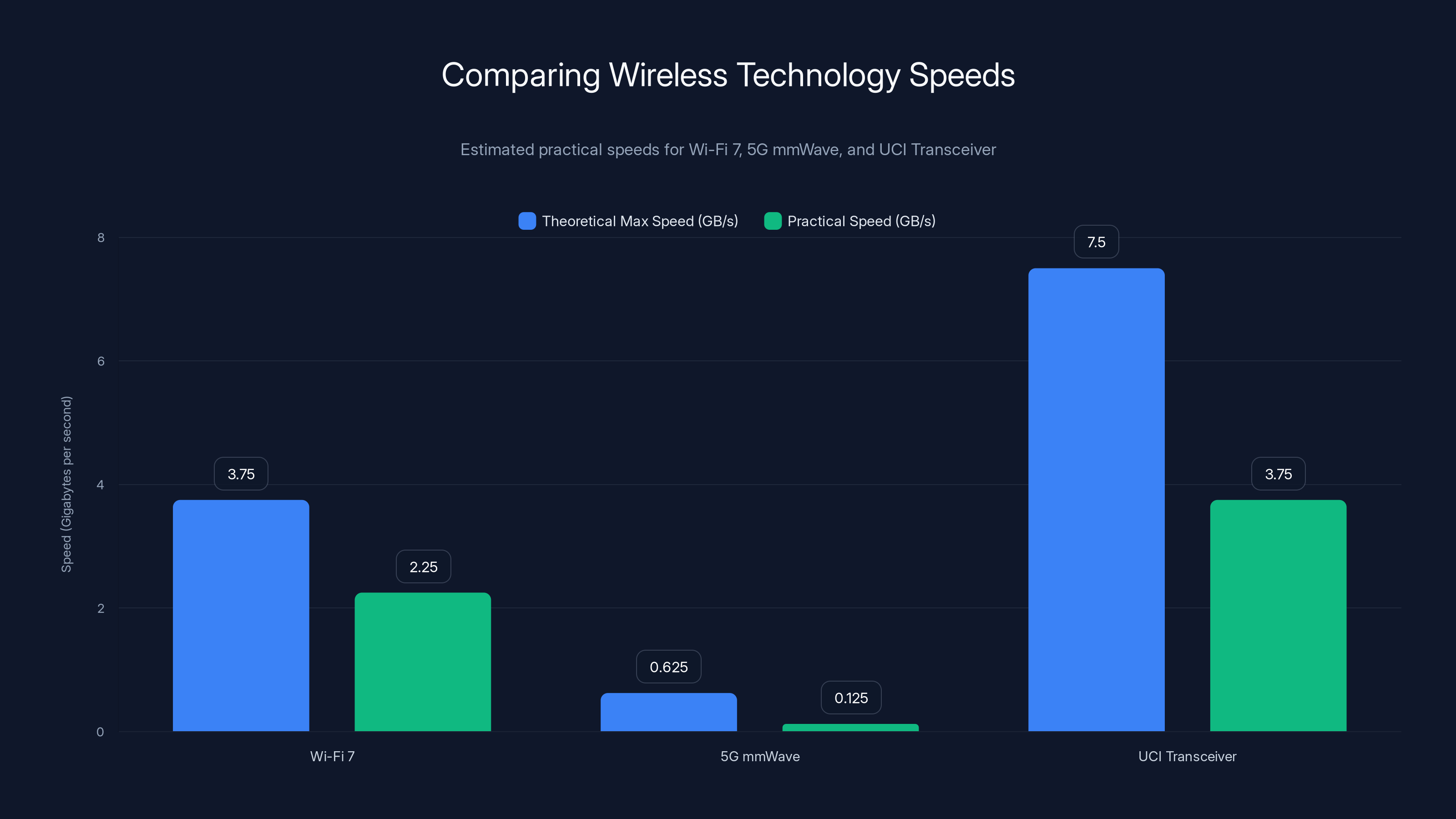

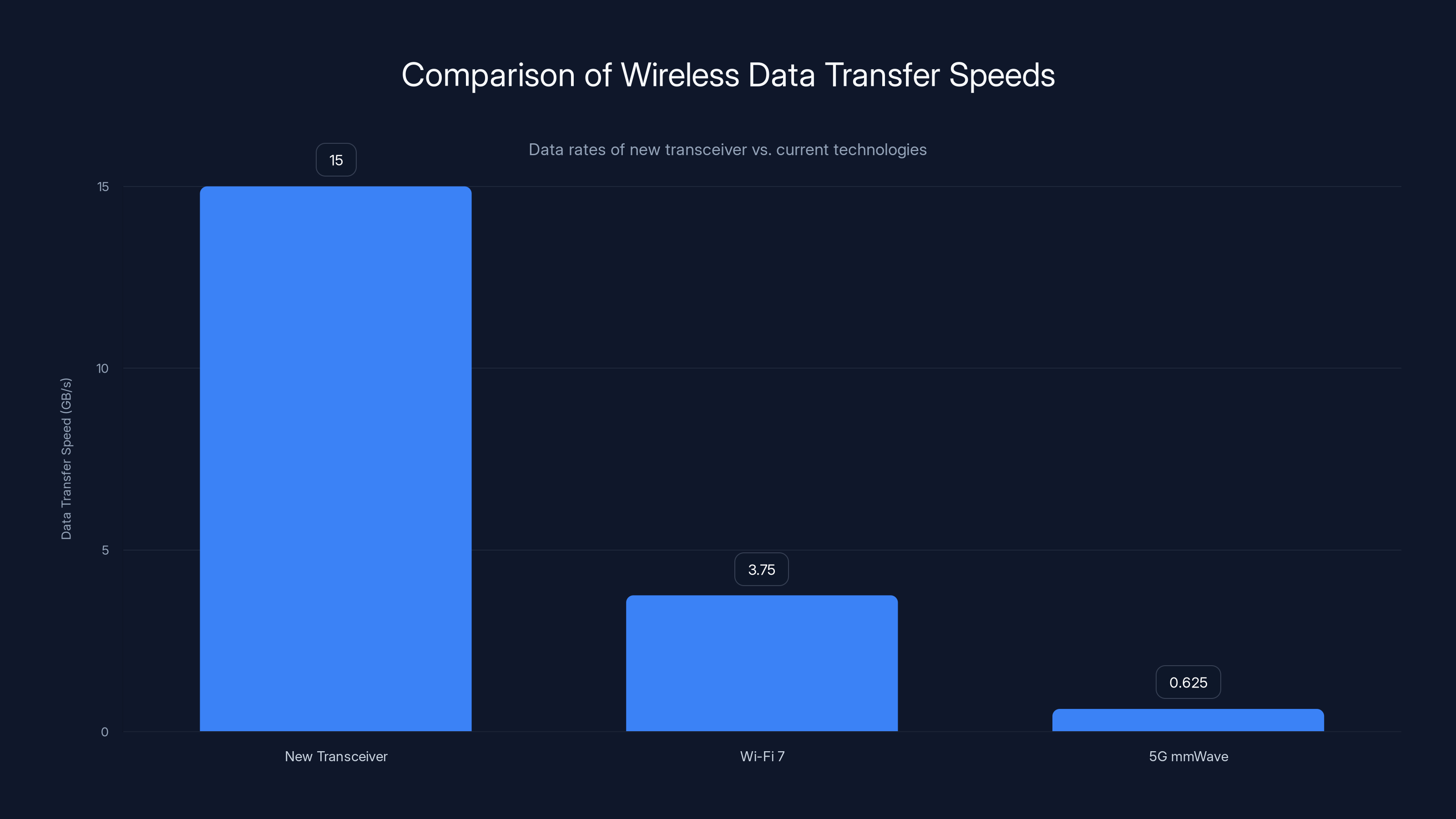

To put this in perspective, your current Wi-Fi 7 router tops out around 3.75 GB/s. Your 5G phone? About 0.625 GB/s on its best day, if you're in a mm Wave coverage area. This new system obliterates both. It's 300% faster than Wi-Fi 7 and roughly 2,300% faster than 5G mm Wave. Those aren't incremental improvements. Those are generational leaps.

But here's what makes this genuinely interesting: it's not magic. It's not some exotic technology requiring quantum computing or materials that don't exist yet. The breakthrough uses something old, proven, and often overlooked: analog signal processing. The team figured out how to do the heavy lifting in analog circuits instead of digital ones, which means the power draw stays reasonable enough for actual devices people carry in their pockets.

This article digs into what makes this work, why it matters beyond the hype, and what real-world applications might actually use this technology. Because right now, the news coverage is fixated on the speed numbers and missing the genuinely interesting engineering underneath.

TL; DR

- 15 GB/s achieved: New transceiver operates at 120 Gbps in the 140GHz frequency band, surpassing Wi-Fi 7 and 5G mm Wave speeds by massive margins

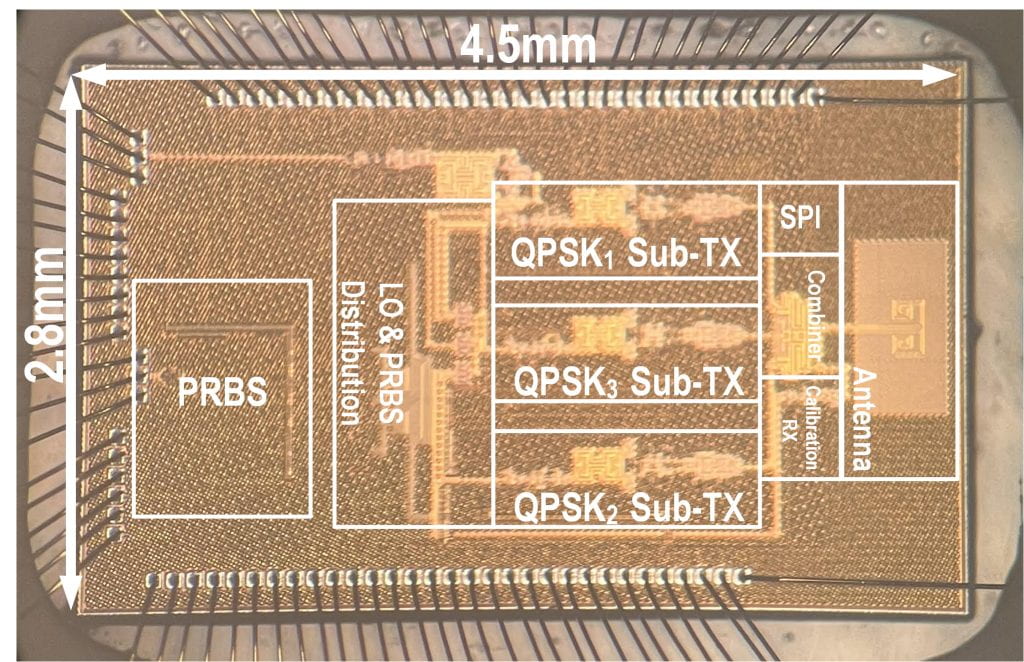

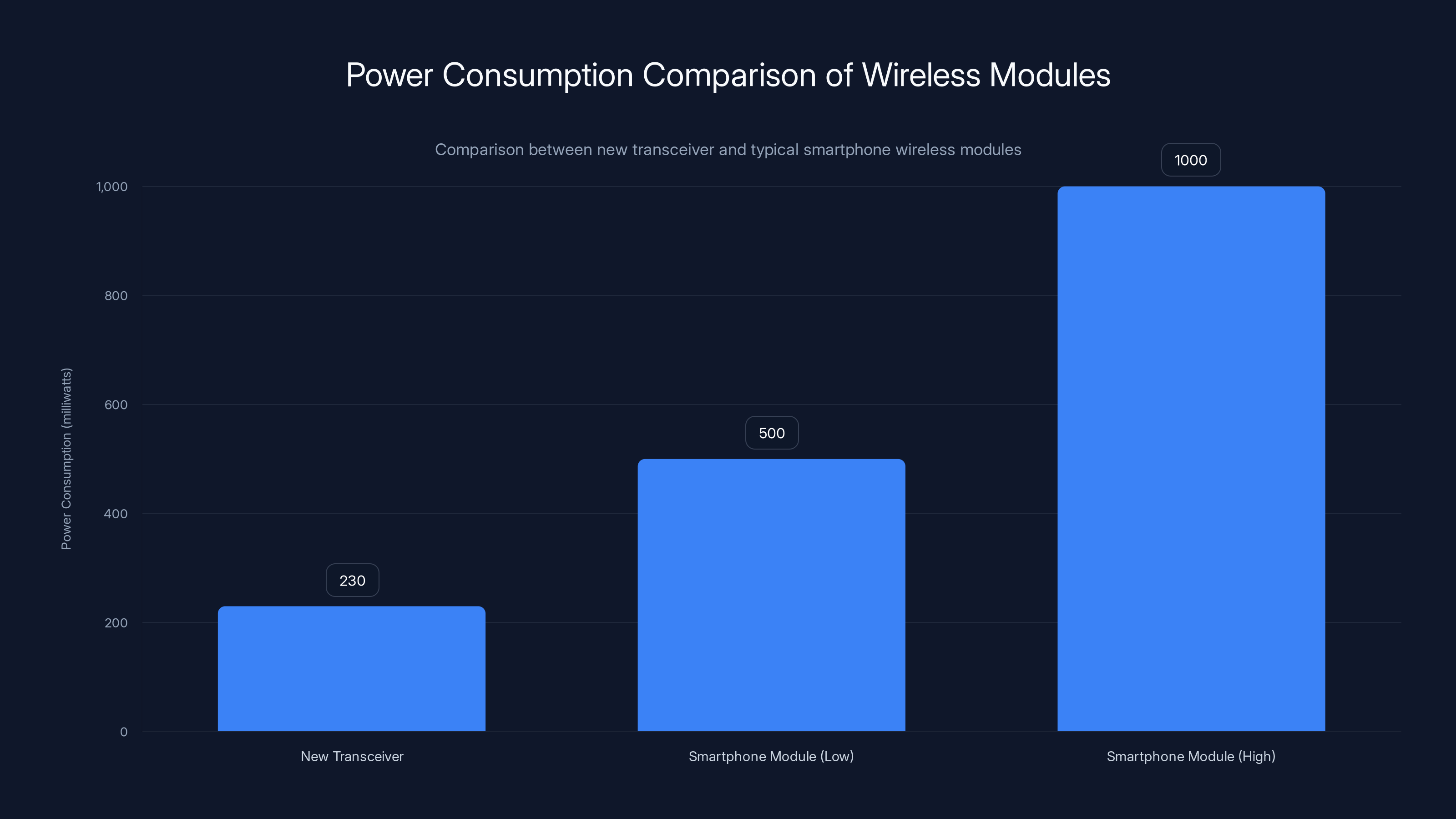

- Analog processing advantage: Uses three synchronized sub-transmitters instead of power-hungry digital-to-analog converters, consuming only 230m W

- Practical manufacturing: Built on 22nm silicon-on-insulator process, simpler than cutting-edge 2nm nodes, enabling easier scale-up

- Range and limitations: Short-range operation at millimeter wave frequencies requires dense infrastructure deployment

- Real-world impact: Potential for wireless data center connectivity and high-speed local area networks within 5-10 years

The new wireless transceiver developed by UC Irvine transmits data at 15 GB/s, significantly outperforming Wi-Fi 7, 5G mmWave, and 4G technologies.

Understanding the Speed Numbers and What They Actually Mean

Speed benchmarks for wireless tech can feel like comparing horsepower across different vehicle types. The numbers matter, but context matters more.

Let's break down what 15 GB/s actually translates to in human terms. A single gigabyte is 1,000 megabytes. Fifteen gigabytes per second means you could download a 4K movie (roughly 50 gigabytes) in about 3.3 seconds. A full Blu-ray disc (50 GB)? Same timeframe. That sounds absurd because our brains are trained by years of waiting for Netflix to buffer.

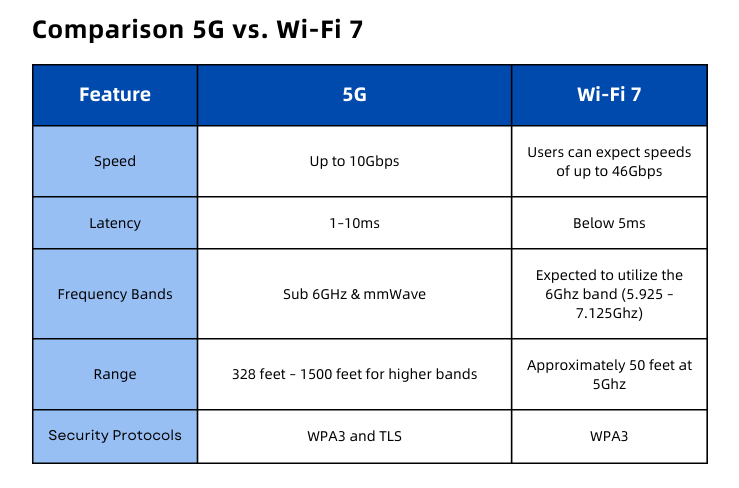

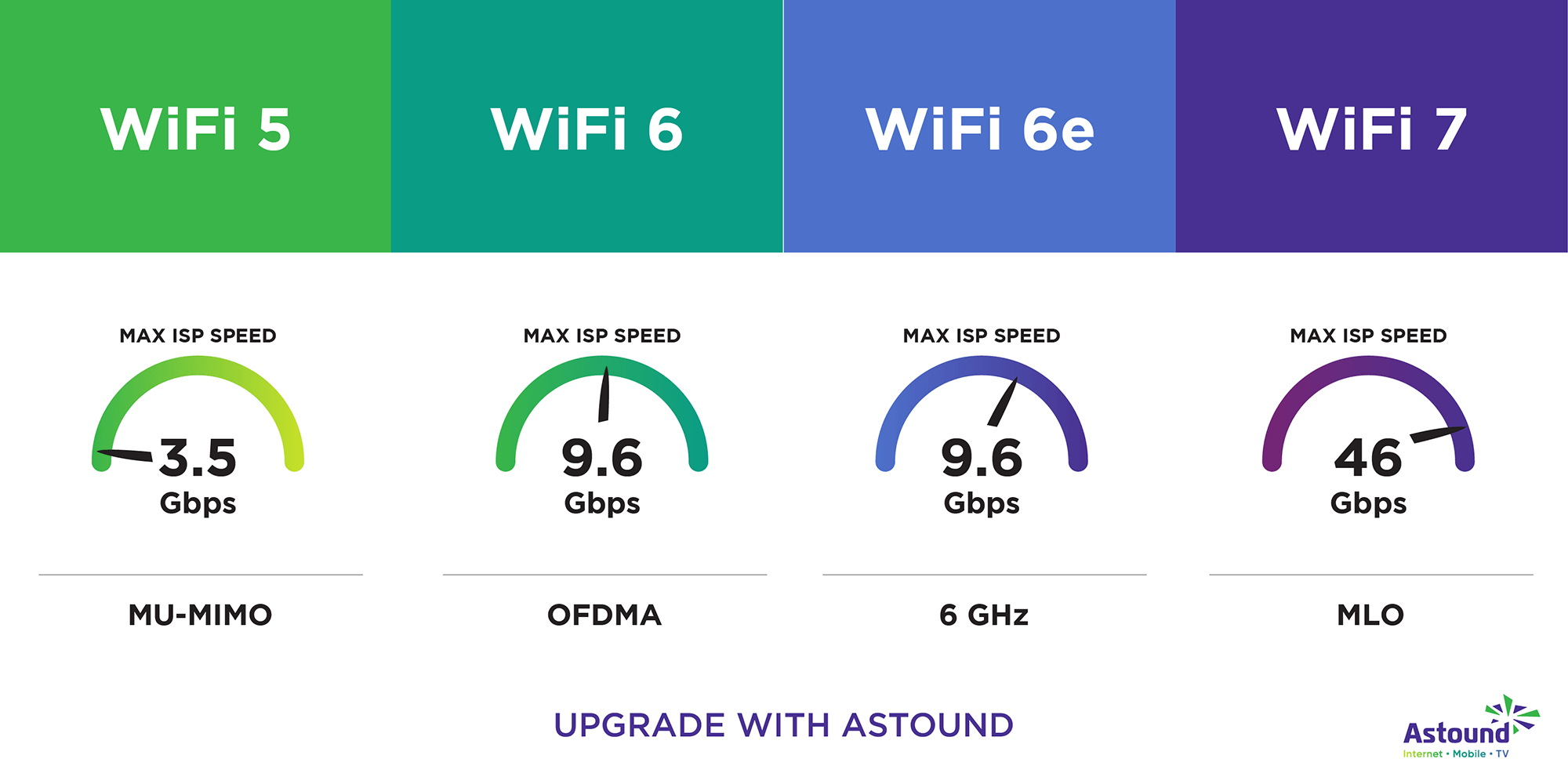

Wi-Fi 7, the current bleeding-edge standard rolling out in 2024-2025, promises theoretical maximums around 30 gigabits per second, which equals 3.75 gigabytes per second. Most real-world implementations hit 60-70% of theoretical max, so expect practical speeds around 2.25 GB/s in the best conditions. That's still incredible compared to Wi-Fi 6, but it's nowhere near this new transceiver.

5G mm Wave is the confusing one because carriers love talking about gigabit speeds. When they say "1 gigabit per second," they mean 1 gigabit, not gigabyte. One gigabit equals 125 megabytes per second, or 0.125 gigabytes per second. Some coverage areas with multiple carrier aggregation can reach 5 gigabits per second (0.625 gigabytes per second), but that's the absolute ceiling under perfect conditions that rarely occur in real life.

This new UCI transceiver operates at 140 GHz, doubling the frequency of current 5G mm Wave systems. Higher frequency means more spectrum available, which means more bandwidth. But there's always a catch.

Higher frequencies also mean shorter range. A 5G mm Wave antenna might cover 300 meters in open space. At 140 GHz, you're looking at substantially shorter distances. The researchers haven't published exact range figures, but physics tells us it'll be measured in tens of meters for practical outdoor use. That doesn't make it useless—it just changes where you'd actually deploy it.

The DAC Bottleneck: Why Previous Approaches Failed

This is where the engineering gets genuinely clever, and where most tech coverage completely whiffs.

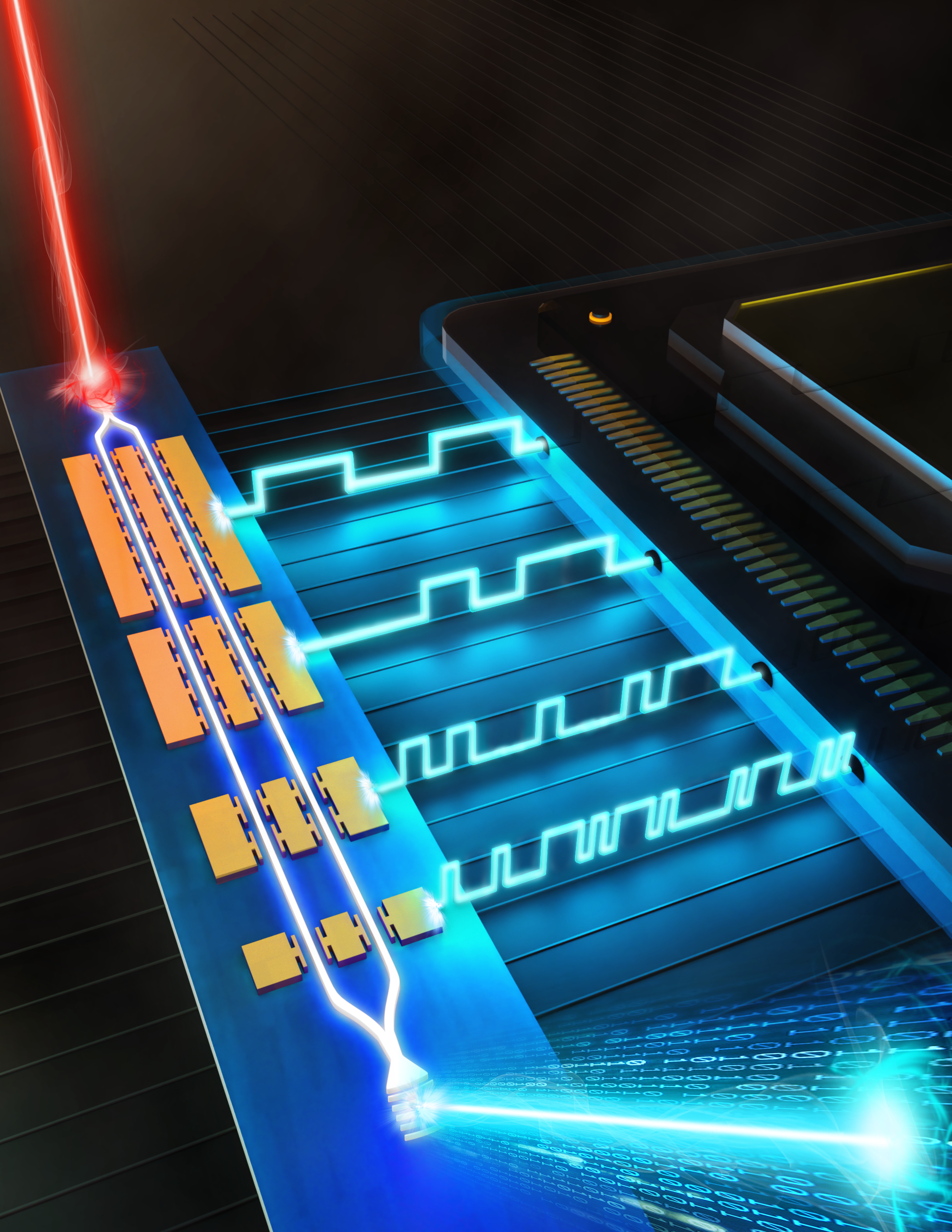

Traditional wireless transmitters work like this: you have digital data (ones and zeros), and you need to convert that into analog radio waves. You use a component called a digital-to-analog converter, or DAC. The DAC samples the digital signal thousands of times per second and produces corresponding voltage levels that feed into the transmitter amplifier.

At 5G speeds, you might need a DAC sampling at tens of gigasamples per second. That's manageable. At 120 gigabits per second, you need a DAC sampling at enormous rates. The power consumption of that DAC scales with the sampling rate. A DAC capable of producing 120 Gbps output would consume several watts of power continuously.

For a wireless device that runs on battery, several watts is catastrophic. It's the difference between all-day battery life and needing a recharge after two hours of heavy use. The researchers identified this as the fundamental constraint limiting higher speeds: the DAC was the bottleneck.

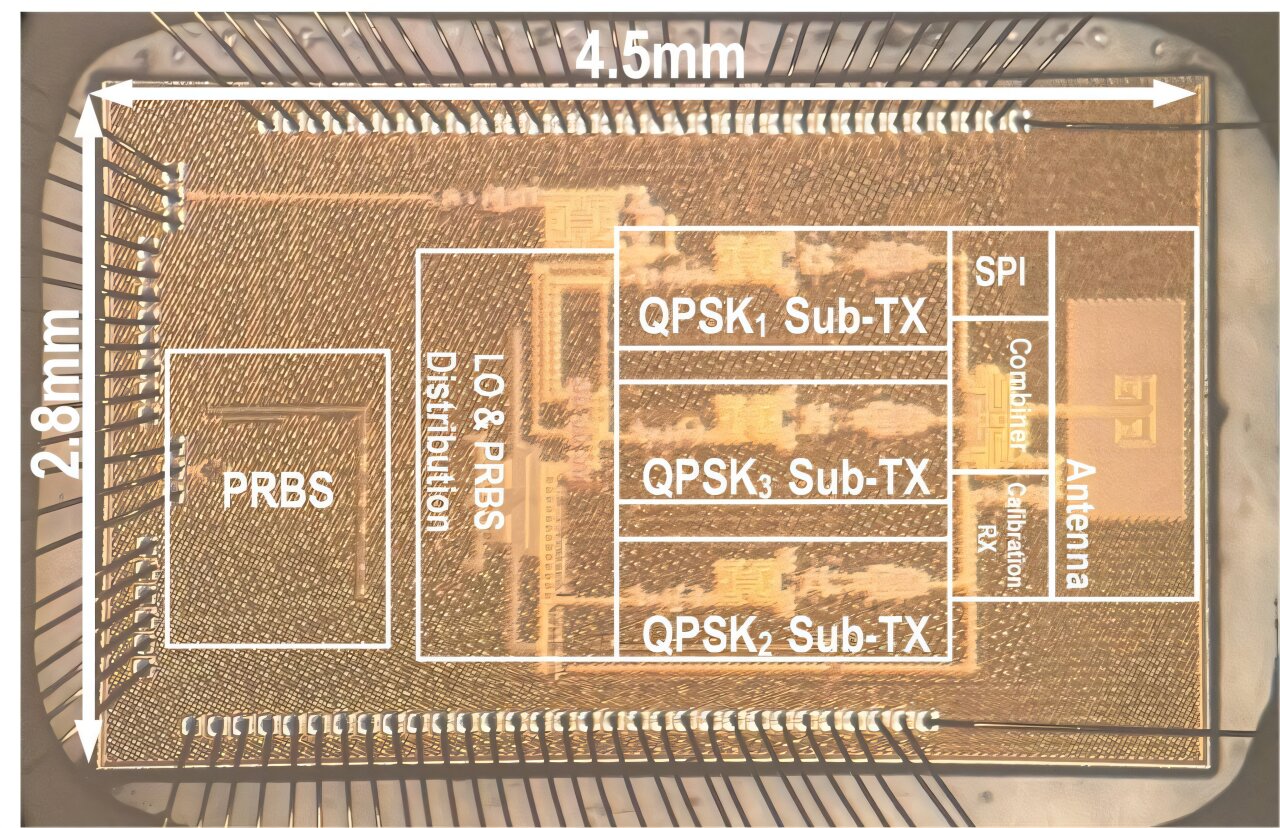

Instead of building a single super-fast DAC, they designed three separate, slower sub-transmitters that operate in a synchronized fashion. Each sub-transmitter handles roughly one-third of the total data rate, which means each DAC runs at a more reasonable sampling speed. The three signals are then combined cleverly in the analog domain to produce the final 120 Gbps output.

The brilliant part: three slower DACs, combined, consume only 230 milliwatts. A single monolithic DAC doing the same job would need multiple watts. That's roughly a 10x improvement in power efficiency just by reimagining the architecture.

This isn't new theory. Analog signal processing has been around for decades. But at modern frequencies and data rates, most engineers had abandoned analog approaches as too imprecise. The UCI team showed that precision matters less than efficiency when you're dealing with millimeter-wave frequencies and modern error correction algorithms.

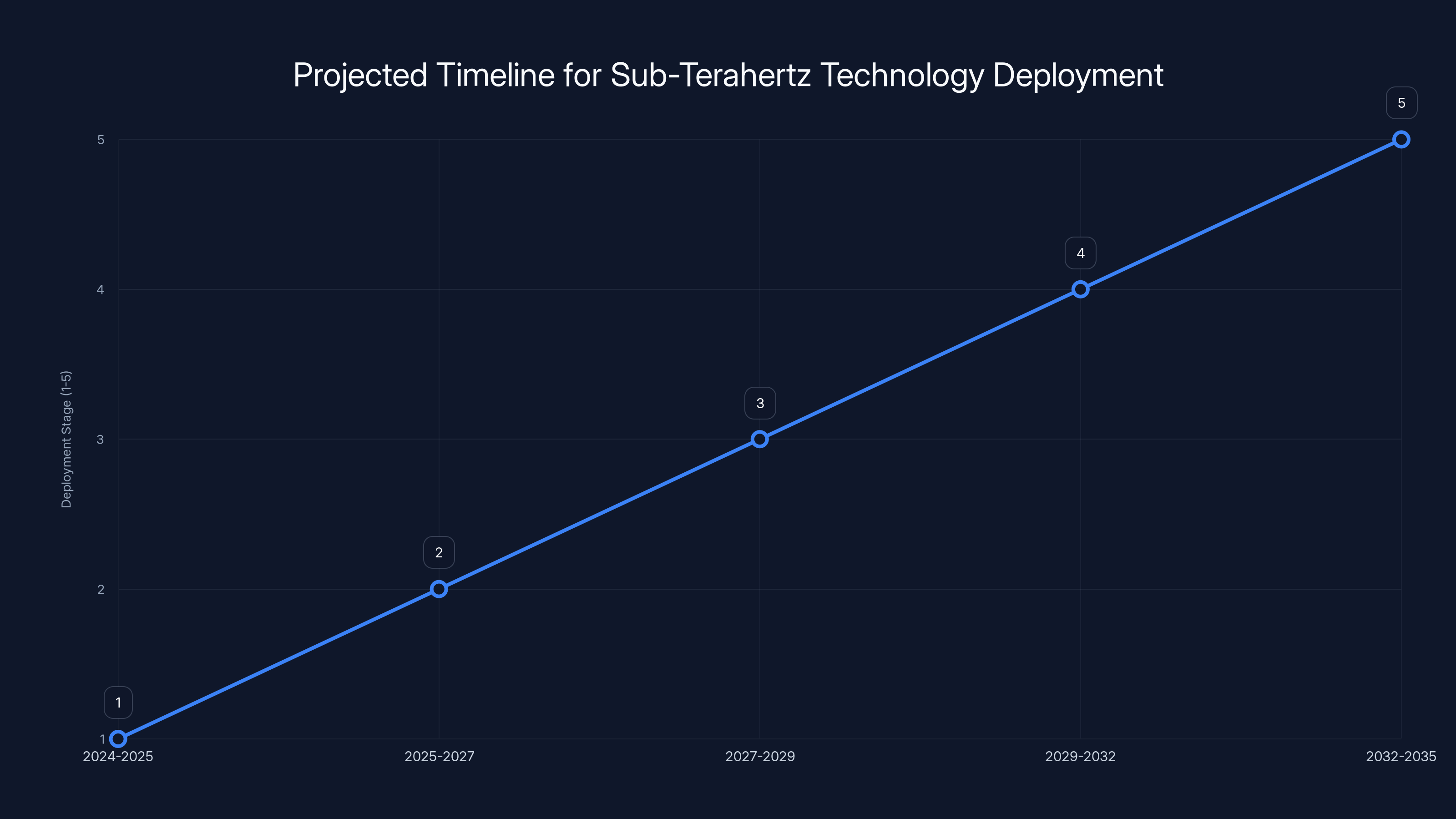

The timeline projects sub-terahertz technology evolving from research to consumer applications over a decade. Estimated data based on historical trends.

Manufacturing Simplicity: Why 22nm Silicon Works Here

Here's another angle that makes this breakthrough pragmatic rather than purely academic.

The transceiver is fabricated on 22-nanometer silicon-on-insulator (SOI) technology. That's... not cutting-edge. TSMC and Samsung are already shipping production chips on 3-nanometer processes. Intel's pushing toward 20 angstroms (2 nanometers) on some experimental chips. Why would researchers choose 22nm for a speed record?

Because 22nm technology is mature, widely available, and proven at massive scale. TSMC's 22nm node is reliable, yields are high, and the process is optimized for production. Leading-edge nodes like 2nm are experimental for most applications outside flagship smartphone processors. They cost exponentially more to design for, yield rates are lower, and production volumes are limited.

For a technology to transition from research to actual products you can buy, manufacturing matters as much as the physics. A breakthrough that only works on exotic leading-edge process nodes stays in research forever. A breakthrough that works on mature, widely-available technology can actually reach real devices.

The UCI team's choice of 22nm reflects realistic thinking about commercialization. They proved the approach works on accessible technology. The next iteration might use 14nm or 7nm as those nodes mature further, but the architecture works across multiple process nodes.

This also affects cost and power consumption. Smaller process nodes use less power per gate generally, but they're more expensive to develop and manufacture in volume. The UCI design uses established silicon processes that companies already use for consumer products like phones and routers.

The Frequency Spectrum: Operating at 140 GHz

The transceiver operates in the 140 GHz band, which is part of the sub-terahertz spectrum. This matters for understanding both the capabilities and limitations.

Current wireless standards live at much lower frequencies. 4G LTE operates in bands ranging from 600 MHz to 2.6 GHz depending on the carrier and region. 5G NR (the official standard for 5G) operates in two main categories: sub-6 GHz for broad coverage, and millimeter-wave (24-71 GHz) for extreme capacity in dense areas.

140 GHz is higher than anything currently deployed for consumer wireless. It sits in a spectrum band that's mostly unused for mobile communications because the technology to use it efficiently didn't exist at reasonable power levels. There's plenty of available spectrum there. The FCC and other regulatory bodies haven't allocated it for consumer use in most countries, but that could change as the technology matures.

Higher frequency means shorter wavelength, which affects antenna design, propagation, and almost everything else about the physics. It also means more available bandwidth. Current 5G mm Wave bands might offer 800 megahertz of total bandwidth in a geographic area. Sub-terahertz bands offer terahertz-scale bandwidth, orders of magnitude more. That's where the data rate improvements come from.

The downside is atmospheric absorption. Higher frequencies are absorbed by oxygen and humidity in the air. 140 GHz signals don't propagate as far through rain, fog, or even humid air as lower frequencies. The effective range shrinks dramatically. This is why the researchers specifically mention this technology is suited for short-range links like data center interconnects, not for covering city blocks.

Power Efficiency: The Real Engineering Achievement

Power consumption is where this breakthrough becomes genuinely valuable for actual deployment.

A transmitter capable of 120 Gbps that draws 230 milliwatts is remarkable because 230 milliwatts is within the realm of battery-powered devices. For comparison, the wireless module in a smartphone uses approximately 500 milliwatts to 1 watt during active data transmission. This transceiver uses less power than a typical cellular radio, despite being 40x faster.

That's the game-changer. Speed without power is academically interesting. Speed with reasonable power consumption is deployable.

The efficiency comes from the analog architecture. By doing signal processing in the analog domain, the designers avoided the overhead of repeatedly converting between analog and digital representations. Each conversion introduces losses. Fewer conversions means less wasted energy.

The three synchronized sub-transmitters also contribute to efficiency because they're smaller, specialized components. Smaller circuitry means less capacitive loading, less parasitic resistance, and lower overall power dissipation. Specialization means each sub-transmitter can be optimized specifically for its job rather than trying to build one general-purpose component that does everything.

Future iterations might push this further. Researchers might implement similar principles on newer process nodes, where transistors are smaller and inherently more efficient. Or they might add more sub-transmitters to distribute the workload even further. But the fundamental insight—that multiple smaller analog processors beat one monolithic digital converter on efficiency—will likely remain valid.

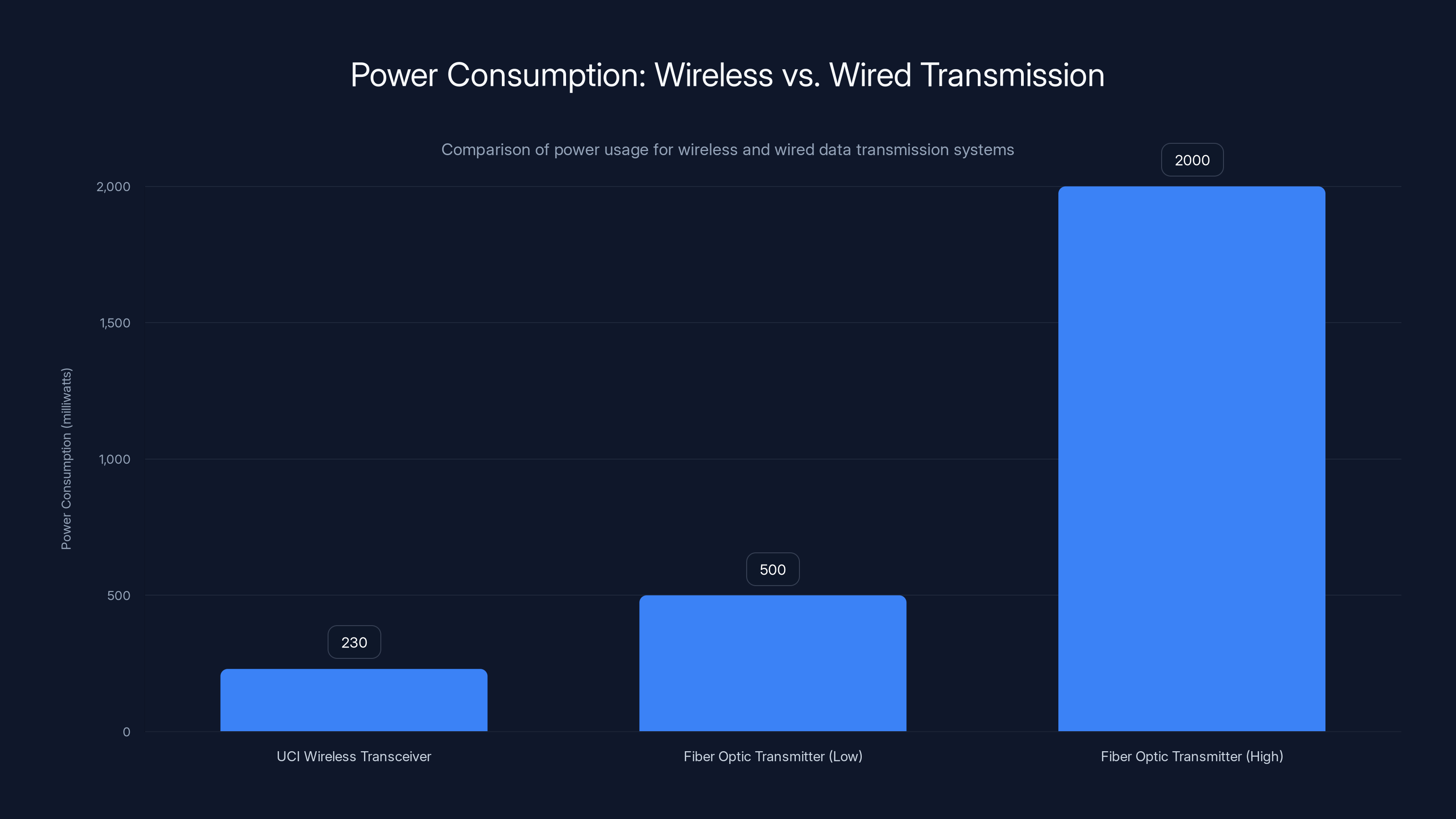

The UCI wireless transceiver consumes significantly less power (230 mW) compared to fiber optic systems, which range from 500 mW to 2000 mW. This efficiency can lead to reduced energy usage and environmental impact in large-scale data centers.

Practical Applications: Where This Actually Gets Deployed

Now for the question everyone's thinking: when can I buy this?

The honest answer is probably five to ten years for any commercial deployment, and even then it won't be what you'd expect.

This technology isn't heading for your phone. Smartphones need wide coverage areas, battery life measured in days, and compatibility with existing networks. Sub-terahertz frequencies with ranges measured in tens of meters don't fit that profile.

Instead, look for this in data centers first. The technology's ideal for wireless interconnect between server racks, between data center buildings, or between colocation facilities. Traditional fiber optic cables work great, but they require careful routing, expensive installation, and become problematic when you need to frequently reconfigure rack layouts. A wireless link at 15 GB/s changes the economics dramatically.

Imagine a data center where you can rapidly reconfigure the network by moving wireless modules around instead of pulling cables. That's worth real money to cloud providers managing massive infrastructure.

The second application is likely military and aerospace. The military funds lots of RF research that eventually becomes civilian. Sub-terahertz links for aircraft, ships, or ground stations have applications in tactical networks. The short range is actually an advantage for security and anti-jamming purposes.

Then consider local area networks (LANs) in challenging environments. Hospitals need wireless connectivity but can't run cables through older buildings. Universities have outdoor areas where cabling is impractical. Office parks with multiple buildings need inter-building links. Sub-terahertz wireless could replace expensive fiber runs in these scenarios.

Mobile backhaul—the network connection between cellular base stations and the core network—is another possibility. Base stations on cell towers or rooftops could use high-speed wireless links to connect to the network instead of relying on fiber, microwave, or millimeter-wave backhaul currently in use.

What you probably won't see in the next decade: consumer gadgets using this. The infrastructure requirements are too demanding, the power efficiency, while excellent for the speed, still exceeds what a smartphone would tolerate for all-day use. When the technology does eventually reach consumer devices, it might be for ultra-short-range communications—maybe 10 to 30 meters—as a replacement for USB-C or Thunderbolt cables for high-speed file transfer.

Comparing to Current Wireless Standards

Let's get specific about how this stacks up against the technologies you actually use.

Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax) operates at 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz, with maximum speeds around 9.6 Gbps (1.2 GB/s). It's designed for wide coverage in homes and offices. Real-world throughput typically runs 600-800 Mbps for most users. The UCI transceiver is about 100x faster.

Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be), rolling out now, adds 6 GHz spectrum and reaches 30 Gbps (3.75 GB/s) theoretical maximum. It's designed for dense deployments where you need more capacity, not longer range. Still, the UCI transceiver is 4x faster.

5G millimeter-wave peaks at around 10-20 Gbps in controlled tests, which translates to roughly 1.25-2.5 GB/s. Real-world speeds in actual coverage areas run 100-500 Mbps depending on how many users share the base station. The UCI transceiver is 6-15x faster than 5G mm Wave's theoretical peak.

5G sub-6 GHz (the more common 5G variant) offers 100-500 Mbps for most users, though theoretical peaks reach about 1-2 Gbps. The UCI transceiver is 7,500x faster than typical 5G sub-6 performance.

Fiber optic links in data centers achieve speeds in the 100+ Gbps range now, with 400 Gbps becoming standard. The UCI transceiver is competitive with deployed fiber infrastructure but doesn't need cables.

The transceiver sits in this interesting gap: it matches or beats the fastest wireless technology deployed today, approaches fiber speeds without the installation hassle, but only works over short distances. That's why data center and inter-building applications make sense.

Range and Coverage: The Fundamental Physical Limitation

This is where you need to temper your excitement with physics.

Electromagnetic waves at higher frequencies get absorbed and scattered by atmospheric particles, rain, humidity, and even dust. The relationship is roughly proportional to the square of the frequency. Double the frequency, and you lose roughly 4x the power over the same distance.

5G millimeter-wave systems at 71 GHz already suffer from range issues. They work great in clear outdoor areas or clean line-of-sight indoor environments, but they struggle with walls, rain, and atmospheric interference. Outdoor coverage typically maxes out around 300 meters in ideal conditions, often much less in reality.

The UCI transceiver operates at 140 GHz, roughly double the frequency of the highest 5G bands. Based on the physics, you're looking at roughly 4x worse propagation. That suggests effective range in the 50-100 meter ballpark in open air, substantially less through walls or in poor weather.

For the intended applications—data center racks, inter-building links, controlled environments—that's acceptable. You're not trying to cover a city. You're trying to connect two buildings 100 meters apart, or two parts of a data center 50 meters apart. Within those constraints, the range works.

But this also explains why this won't replace 5G broadly. You can't build a consumer network where every person carries a device that only communicates over 50 meters. The infrastructure cost would be astronomical. You'd need transmitter stations every city block, each drawing considerable power, and managing interference would become a nightmare.

Wi-Fi 7 offers practical speeds around 2.25 GB/s, while 5G mmWave reaches 0.125 GB/s in real conditions. The UCI Transceiver, operating at 140 GHz, promises practical speeds of 3.75 GB/s. Estimated data.

Synchronization and Signal Processing Challenges

Here's a technical detail that seems small but is actually crucial to why this breakthrough took until 2024 to achieve.

When you split a signal across three sub-transmitters, they need to be synchronized almost perfectly. If they're off by even a few picoseconds, the signals don't combine properly. The result is degraded signal quality, increased error rates, and lost data.

At 140 GHz frequencies, maintaining that synchronization is genuinely difficult. The wavelengths are tiny—just a couple millimeters—so even tiny physical distances introduce phase shifts. Everything from trace length mismatches in the chip layout to voltage supply variations can throw off synchronization.

The UCI researchers apparently solved this through careful analog design. They likely use feedback mechanisms to continuously correct for phase and timing drift. They might use phase-locked loops that monitor the output signals and adjust the sub-transmitter parameters in real-time.

The details aren't obvious from public descriptions of the work, but this synchronization challenge is probably why nobody did this before. It's easy in theory: use three smaller converters instead of one big one. Executing it reliably at 140 GHz requires engineering chops.

This also matters for manufacturing. Every chip produced needs to perform consistently. If synchronization drifts in unpredictable ways across production runs, you'd have yields so low the part would never reach the market. The UCI team clearly figured out how to make the design robust enough for manufacturing.

Error Correction and Signal Integrity

At 120 Gbps, signal integrity becomes critical. Random errors in data transmission become statistically inevitable without good error correction.

Modern communication systems use sophisticated error correction codes that can fix burst errors and single-bit errors. These codes add redundancy—you send extra bits along with your data so the receiver can detect and fix problems. The overhead is typically 20-30% extra data required.

So the real-world throughput might be 90-96 GB/s after accounting for error correction overhead, still absolutely massive but not quite the full 15 GB/s figure. The researchers probably achieved their 120 Gbps figures with error correction factored in—modern systems always do—but the exact details aren't emphasized in popular coverage.

The choice of modulation scheme matters too. Simple modulation (like basic frequency-shift keying) is robust to noise and interference but uses spectrum inefficiently. Complex modulation (like 256-quadrature amplitude modulation) squeezes more data per hertz of spectrum but requires cleaner signals. The UCI team presumably used some intermediate approach optimized for the 140 GHz environment.

Interference and Coexistence Considerations

At 140 GHz, interference from other systems becomes less of a problem than at lower frequencies, but it's not zero.

Fewer devices currently operate at 140 GHz, which means less existing interference. But if multiple systems tried to use the same spectrum in the same area, they'd interfere with each other just like any wireless system. The sub-terahertz bands haven't been heavily allocated to consumer use, so there's not much deployed infrastructure to interfere with.

That said, as these systems become more common, frequency coordination becomes important. Data center operators using this technology would need to manage frequency allocation carefully. If Building A is using 140.5 GHz and Building B next door tries to use 140.3 GHz, they'd need careful placement and shielding to avoid mutual interference.

The short range actually helps here. Signal power drops rapidly with distance at these frequencies, so interference doesn't propagate far. A system operating 200 meters away causes minimal interference.

The new wireless transceiver achieves data rates of 15 GB/s, which is 300% faster than Wi-Fi 7 and roughly 2,300% faster than 5G mmWave, marking a significant generational leap in wireless technology.

Integration with Existing Networks

Here's the practical question: how do you actually integrate this into current infrastructure?

You can't just plug a 140 GHz transceiver into your existing Wi-Fi router. They operate at completely different frequencies and use different protocols. The integration path likely involves dedicated wireless links used for specific high-bandwidth applications, separate from general-purpose Wi-Fi.

A data center might use traditional Ethernet and fiber for general connectivity, then add these high-speed wireless links specifically for rack-to-rack interconnects or building-to-building backhaul. The applications are specialized, not general-purpose.

Over time, as the technology matures and costs decline, you might see broader integration. But the initial deployments will be targeted at specific high-value applications where the speed justifies the costs and complexity.

Software would need updating too. Network protocols and drivers would need support for the new interface. The operating system would need to understand how to route traffic over these links. Standards bodies would need to define protocols for 140 GHz communication. That's years of work even after the hardware is ready.

Future Frequency Bands and Technology Roadmap

The UCI research is likely not the endpoint. It's a proof of concept showing what's possible.

Future iterations might operate at different frequencies in the sub-terahertz range. The 140 GHz band might become congested once multiple manufacturers build systems. The FCC and international regulatory bodies might open different bands. Researchers might find that other frequencies offer better trade-offs between range, data rate, and power consumption.

The architecture—using multiple synchronized analog sub-transmitters instead of a monolithic digital converter—seems likely to persist. It's a fundamentally good approach to the problem, and the physics that makes it necessary (power consumption of fast DACs) doesn't change.

The 22nm process node will probably be outdated in ten years. Future implementations might use 7nm or even smaller nodes, which would improve efficiency further and possibly enable even higher data rates. But the core innovation is architectural, not dependent on the process technology.

Implications for 6G and Beyond

This research feeds directly into 6G development.

6G is still mostly vaporware at this point—no standards, no defined specifications, just a lot of research exploring what's possible. Various industry groups and academic teams are working on different aspects, and high-frequency wireless links are definitely part of the conversation.

The UCI transceiver doesn't prove that 6G will use this exact approach, but it proves that sub-terahertz frequencies can work for high-speed wireless. It provides data points for the standards bodies eventually developing 6G specifications.

6G will likely include a mix of technologies: lower frequencies for coverage, higher frequencies for capacity in dense areas, and probably sub-terahertz for specialized point-to-point links. The UCI work contributes to understanding the high-frequency piece.

But expectations matter here. The consumer tech media often spins research breakthroughs as consumer products arriving imminently. The reality: this transceiver will probably spend the next three to five years in refinement, testing, and optimization. Then another two to three years in niche commercial deployments at high prices. Consumer devices, if they ever use this technology, are probably 10-15 years away.

The new transceiver consumes significantly less power (230 milliwatts) compared to typical smartphone wireless modules, which use between 500 milliwatts to 1 watt, while delivering 40x faster speeds.

Competing Technologies and Alternative Approaches

The UCI team isn't the only group working on millimeter-wave and sub-terahertz wireless. Multiple companies and research institutions are exploring similar problems.

Millimeter-wave backhaul systems already exist from companies like Siklu and Dragon Wave. They operate at 60 GHz and reach distances of a few kilometers for data center backhaul. They're commercial products used in real networks today.

Free-space optical (FSO) systems transmit data using laser light through air. They achieve data rates similar to this transceiver, sometimes higher. They're already deployed for data center interconnect. The UCI transceiver offers advantages over FSO—radio frequencies work better in some weather, while FSO is completely blocked by fog or heavy rain. Neither is universally superior.

Terahertz imaging and communication is another research frontier. Some teams are pushing toward true terahertz frequencies (several hundred GHz to 1 THz or higher). Those systems face even more extreme challenges but offer even higher potential data rates. The UCI work is a stepping stone toward those capabilities.

Optical wireless (visible light communication) and infrared laser communication offer other approaches to high-speed wireless without using traditional RF. Each has trade-offs in range, weather resilience, and power efficiency.

The field is active. The UCI breakthrough will inspire similar work at other institutions. Standards bodies might accelerate frequency allocation for sub-terahertz bands. Competition will drive costs down and capabilities up.

What This Means for Network Architecture

If high-speed wireless links become common, network architecture changes.

Traditionally, you build a network with fiber spines (high-speed backbones) and lower-speed access links to end devices. That's driven by the massive bandwidth gap between long-distance fiber and wireless links.

If wireless links approach fiber speeds, that distinction starts to blur. You might build networks where every node connects wirelessly to every other node, forming true mesh networks instead of hierarchical tree structures. That enables faster failure recovery and better load balancing.

Or you might use wireless selectively for backup links and redundancy. If your primary fiber fails, high-speed wireless can take over without massive capacity reduction.

Data center topologies could change significantly. Instead of rows of servers connected to switches connected to spines in fixed topologies, you could have more fluid configurations where connections are established dynamically based on traffic patterns.

These architectural shifts take years to plan and implement. But as wireless speeds increase, they become economically feasible.

Environmental and Power Considerations

One underappreciated aspect of wireless versus wired: environmental impact.

Wired networks require physical infrastructure. Fiber requires trenching, conduit, and installation labor. That's carbon-intensive. It's also destructive—you're literally digging up land.

Wireless infrastructure requires transmission equipment but no physical cables. In environments where wireless works well, it's arguably more environmentally friendly than traditional wired infrastructure.

The UCI transceiver's 230 milliwatt power consumption for 120 Gbps transmission is extremely efficient. For comparison, plugging an active fiber optic transmitter and receiver might use 500 milliwatts to a few watts depending on the system. The wireless option is competitive or better.

Scaled across a large data center with hundreds of links, power efficiency matters. Lower power consumption means lower cooling requirements, which cascades into lower total energy usage. This matters for both operating costs and environmental footprint.

Timeline to Practical Deployment

Based on how similar technologies have evolved, here's a realistic timeline.

2024-2025 (now): Research paper published, universities and companies intrigued, initial funding for development.

2025-2027: Companies develop prototype products, test in controlled environments, gather performance data, identify engineering challenges.

2027-2029: Small-scale deployments in data centers and military applications, proof of commercial viability, costs remain high ($10k-100k+ per unit).

2029-2032: Broader commercial adoption, costs decline toward $1k-10k per unit, integration with network standards.

2032-2035: Integration into consumer-facing applications becomes possible, costs approach $100-1000 per unit.

This assumes nothing goes catastrophically wrong and progress continues linearly. Breakthroughs could accelerate the timeline. Major technical obstacles could delay it.

Historically, wireless technology timelines match this pattern. 3G was researched in the 1990s, deployed in 2000s, became ubiquitous by 2010s. 4G followed a similar arc. This sub-terahertz technology will likely follow the same S-curve.

Investment and Commercial Potential

Why should you care about this if you're not building data centers?

Investment thesis: High-speed wireless infrastructure is a growing market. Venture capital and strategic corporate investors are funding companies developing these technologies. If you're interested in technology investment, wireless infrastructure is an underappreciated sector compared to consumer-facing tech.

You've got established players like Broadcom, Qualcomm, and Intel funding sub-terahertz research. You've got startups like Vital Telecom, Wireless Telecom Group, and others working on millimeter-wave products. The market is real, growing, and attracting capital.

The total addressable market includes data center operators (multi-billion dollar companies constantly seeking infrastructure improvements), telecommunications carriers (building 5G and future networks), military and defense (always investing in communication systems), and aerospace (satellite and aircraft communication).

That's a substantial market opportunity. Companies that successfully commercialize these technologies will capture significant value.

Common Misconceptions About This Technology

Let's clear up what this breakthrough does and doesn't do.

It's not a replacement for 5G or Wi-Fi. It's complementary technology for specific use cases where you need extreme bandwidth over short distances.

It's not arriving in phones next year. Real commercial products are probably 5+ years away, mainstream deployment is 10+ years away.

It doesn't eliminate the need for fiber. For long-distance, high-capacity links, fiber remains superior. Wireless is best for situations where wires are impractical.

It's not magic. It's good engineering applied to a well-understood problem. The novelty is the specific solution, not the underlying physics.

It won't solve all wireless problems. Short range, susceptibility to weather, and interference management mean it's specialized, not general-purpose.

Expert Perspectives and Industry Response

How are actual RF engineers reacting to this?

The reaction among researchers seems genuinely positive. The approach is clever, the results are credible, and the implications are clear. Nobody's suggesting it's a fraud or flawed.

The practical question most engineers are asking: how do you scale this? A single chip in a lab is one thing. Producing thousands or millions reliably and economically is different. The UCI team chose 22nm specifically to address this—it's proven, available, and reliable.

Manufacturing partners will eventually need to validate the design and optimize the production process. That's not trivial, but it's entirely doable using established semiconductor practices.

Vendors building products around this technology will need to solve integration challenges. How do you couple this transceiver to antennas without losing efficiency? How do you manage thermal dissipation? How do you package it for use in real environments? These are engineering problems, not physics problems. Solvable.

Practical Considerations for Early Adopters

If you're in an organization considering high-speed wireless links, here's what to evaluate.

Current solutions: What are you using now for the same problem? Fiber has been reliable for decades. Free-space optical works well in some environments. Millimeter-wave links from commercial vendors are proven. Any new technology needs to clearly outperform these options.

Cost: Early-stage technologies are expensive. Budget for prototype costs being 10-100x higher than eventual mature pricing.

Time to deployment: New RF products take time to design into systems. Plan on multi-year development timelines before you can actually use them.

Standards and interoperability: Ensure any system you evaluate has clear pathways toward standards compliance. Proprietary systems limit your options later.

Support and reliability: Emerging technologies sometimes have reliability issues. Ensure the vendor has proper support and warranty coverage.

For most organizations, waiting 3-5 years for this technology to mature makes more sense than chasing leading-edge prototypes. Let other organizations find and solve the problems. Then you can deploy proven, stable systems.

The Broader Wireless Evolution

This transceiver fits into a bigger pattern in wireless technology.

We're seeing a transition from "one standard fits all" to "many specialized standards for different applications."

5G started this trend: you have sub-6 GHz for coverage, millimeter-wave for capacity. 6G will likely extend this further with sub-terahertz for super-high-capacity applications, mid-range frequencies for coverage, low frequencies for extended range and penetration.

That means more complexity for device manufacturers and network operators, but it also means better efficiency. You use the right frequency for each application instead of trying to make one frequency work everywhere.

The UCI transceiver is part of this evolution. It represents the high-frequency, extreme-capacity endpoint of a spectrum that includes much lower-frequency options for different purposes.

Closing Thoughts on Practical Impact

Will this technology change the world? Probably not directly. Most people will never interact with a device using this transceiver.

Will it improve the world? Definitely. Better wireless infrastructure means:

- Faster, more reliable data center networks, enabling better cloud services

- Reduced installation costs for network infrastructure, lowering service costs

- Lower power consumption for equivalent bandwidth, reducing energy usage

- More flexible network deployments, enabling better solutions for difficult environments

Those are incremental improvements from an end-user perspective. They're meaningful improvements from an infrastructure operator's perspective.

The most important aspect might be that someone successfully demonstrated that you can achieve extreme data rates using relatively simple, proven silicon processes and smart analog design. That opens up avenues for further innovation. Other teams will build on this. Competition will drive improvements and cost reductions.

That's how technology progress actually works. One team publishes a breakthrough. Others iterate. Standards emerge. Products appear. Adoption grows. What seemed impossible becomes routine.

This UCI transceiver is a milestone in that process. Not an endpoint, not a revolution, but a clear demonstration that the next level of wireless capability is achievable with current technology. That's worth understanding, even if you never personally use it.

FAQ

What exactly is this new wireless transceiver?

It's a research prototype developed by University of California, Irvine engineers that transmits data wirelessly at 120 gigabits per second (15 gigabytes per second) using sub-terahertz frequencies around 140 GHz. Rather than relying on traditional power-hungry digital-to-analog converters, it uses three synchronized analog sub-transmitters that work together efficiently, consuming only 230 milliwatts of power. The entire system is fabricated on silicon using 22-nanometer technology, making it potentially viable for eventual manufacturing at scale.

How does it compare to current wireless technologies?

It significantly outperforms existing wireless standards: Wi-Fi 7 reaches approximately 3.75 GB/s, 5G millimeter-wave peaks at roughly 0.625 GB/s in real-world conditions, and 4G maxes out around 0.1 GB/s. At 15 GB/s, this transceiver is approximately 300% faster than Wi-Fi 7 and 2,300% faster than 5G mm Wave. For comparison, it approaches the speeds of fiber-optic links used in data centers while eliminating the need for physical cables. However, it has much shorter range, working effectively only over tens to hundreds of meters rather than kilometers.

When will consumers be able to use this technology?

Realistically, practical commercial deployment is five to ten years away, and widespread consumer adoption would likely take 10-15 years. The initial applications will be niche: data center interconnects, military systems, inter-building wireless links, and aerospace communication systems where the short range and specialized requirements are acceptable. Consumer gadgets, if they ever incorporate this technology, are probably a decade or more away from market availability.

Why is the power consumption so important?

Power consumption determines whether a technology can be practical in battery-powered or energy-constrained devices. Traditional digital-to-analog converters capable of 120 Gbps would consume several watts continuously, making devices battery-dead within hours. The UCI design's 230-milliwatt consumption is comparable to current cellular radio modules, suggesting battery-powered applications might be feasible for short-range links. This efficiency is what separates a theoretical breakthrough from something potentially deployable in real products.

What makes this better than fiber optic cables?

Fiber optic cables remain superior for long-distance, high-capacity links and don't have the range limitations of wireless. However, this transceiver offers advantages in specific situations: no need to run and maintain physical cables, easier reconfiguration of connections, less destructive installation, and competitive power consumption. It's not a fiber replacement; rather, it's complementary technology solving different problems. Fiber is best for permanent, long-distance links. Wireless is better for temporary, short-distance, or hard-to-cable environments.

What frequency band does it operate in, and is it regulated?

The transceiver operates around 140 GHz in the sub-terahertz spectrum, which sits between current millimeter-wave bands (24-71 GHz) and true terahertz frequencies. This band hasn't been heavily allocated for commercial use in most countries, so there's substantial available spectrum. The FCC and international regulatory bodies would need to define rules for commercial use, which would take years. Military and research applications can operate in this band with appropriate approvals.

How does the analog signal processing approach work compared to traditional digital methods?

Traditional transmitters convert digital data to analog signals using a single high-speed digital-to-analog converter (DAC). This becomes power-intensive at extreme data rates. The UCI approach replaces one fast DAC with three slower synchronized sub-transmitters, each handling roughly one-third of the data. These operate in the analog domain, reducing conversion overhead and dramatically cutting power consumption. Three slower analog processors are more efficient than one ultra-fast digital processor for this specific problem. Modern error correction algorithms ensure signal quality despite the analog processing.

What real-world applications would use this first?

Most likely deployment scenarios include data center rack interconnects (replacing fiber cables within facilities), wireless backhaul for base stations and network infrastructure, inter-building high-speed links for campuses or colocation facilities, military tactical networks, and satellite/aerospace communication systems. These applications accept the short range and specialized requirements in exchange for high speed, reduced installation costs, and flexible reconfiguration. Consumer applications like smartphones or home Wi-Fi would come much later, if ever.

What are the main limitations that prevent broader deployment?

Primary limitations are short operating range (tens to low hundreds of meters), susceptibility to weather and atmospheric interference at high frequencies, lack of established standards and regulatory frameworks, and immature supply chains and manufacturing processes. Additionally, the technology requires line-of-sight transmission, needs careful frequency coordination to avoid interference, and still requires significant engineering work to integrate into practical systems. These aren't deal-breakers for niche applications but currently prevent mainstream deployment.

How does this fit into 6G development?

This research contributes important data points to emerging 6G specifications and capabilities. 6G will likely incorporate multiple frequency bands serving different purposes: lower frequencies for wide-area coverage, mid-range frequencies for standard capacity, and sub-terahertz frequencies for extreme short-range capacity. This transceiver demonstrates that sub-terahertz can work reliably and efficiently, providing confidence to standards bodies and equipment manufacturers planning 6G deployments. It won't necessarily be the exact technology used in 6G, but it proves the viability of the overall approach.

Key Takeaways

- New sub-terahertz transceiver operates at 120 Gbps (15 GB/s), surpassing Wi-Fi 7 by 300% and 5G mmWave by 2,300%

- Analog signal processing using three synchronized sub-transmitters achieves extreme efficiency: only 230 milliwatts power consumption

- Short range (50-100 meters) and need for line-of-sight make it ideal for data centers and infrastructure, not consumer devices

- Uses mature 22nm silicon technology, making scale manufacturing feasible within 3-5 years

- Realistic commercial deployment timeline: 5-10 years for niche applications, 10-15 years for broader adoption

![15 GB/s Wireless Transceiver: The Future of Data Transmission [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/15-gb-s-wireless-transceiver-the-future-of-data-transmission/image-1-1769560691895.jpg)