7 Mind-Bending Science Stories You Nearly Missed [2025]

Every month, thousands of peer-reviewed scientific papers hit publication servers around the world. Most disappear into the academic void, read only by specialists in narrow fields. But every once in a while, something extraordinary slips through the cracks. A discovery so strange, so unexpected, or so fundamentally weird that it deserves way more attention than it gets.

The thing is, you probably missed them. Not because they weren't important. Not because they weren't interesting. But simply because there's too much noise, and not enough signal.

The past year has been remarkable for science. We've seen discoveries that challenge our understanding of physics, unlock secrets of extinct creatures, and reveal how living animals move in ways we never expected. Some of these findings make headlines for a day and vanish. Others languish in academic journals, waiting for someone to translate the technical jargon into human language.

This roundup collects the stories that deserve way more attention. The research that made us pause and think, "Wait, that's actually incredible." From a fossilized bird that literally choked on rocks 120 million years ago to a cosmic event so bizarre it defies easy classification, these are the discoveries that remind us why science keeps surprising us.

What makes these stories special isn't just that they're weird. It's that each one solves a puzzle, answers a question, or reveals something fundamental about how the world actually works. Some required years of detective work. Others involved international teams analyzing data from multiple telescopes scattered across space. All of them tell a story about human curiosity and what happens when we look closely at problems everyone else overlooked.

Let's dive into seven stories from 2025 that nearly slipped by unnoticed. Each one has changed our understanding of something important, even if you haven't heard about it yet.

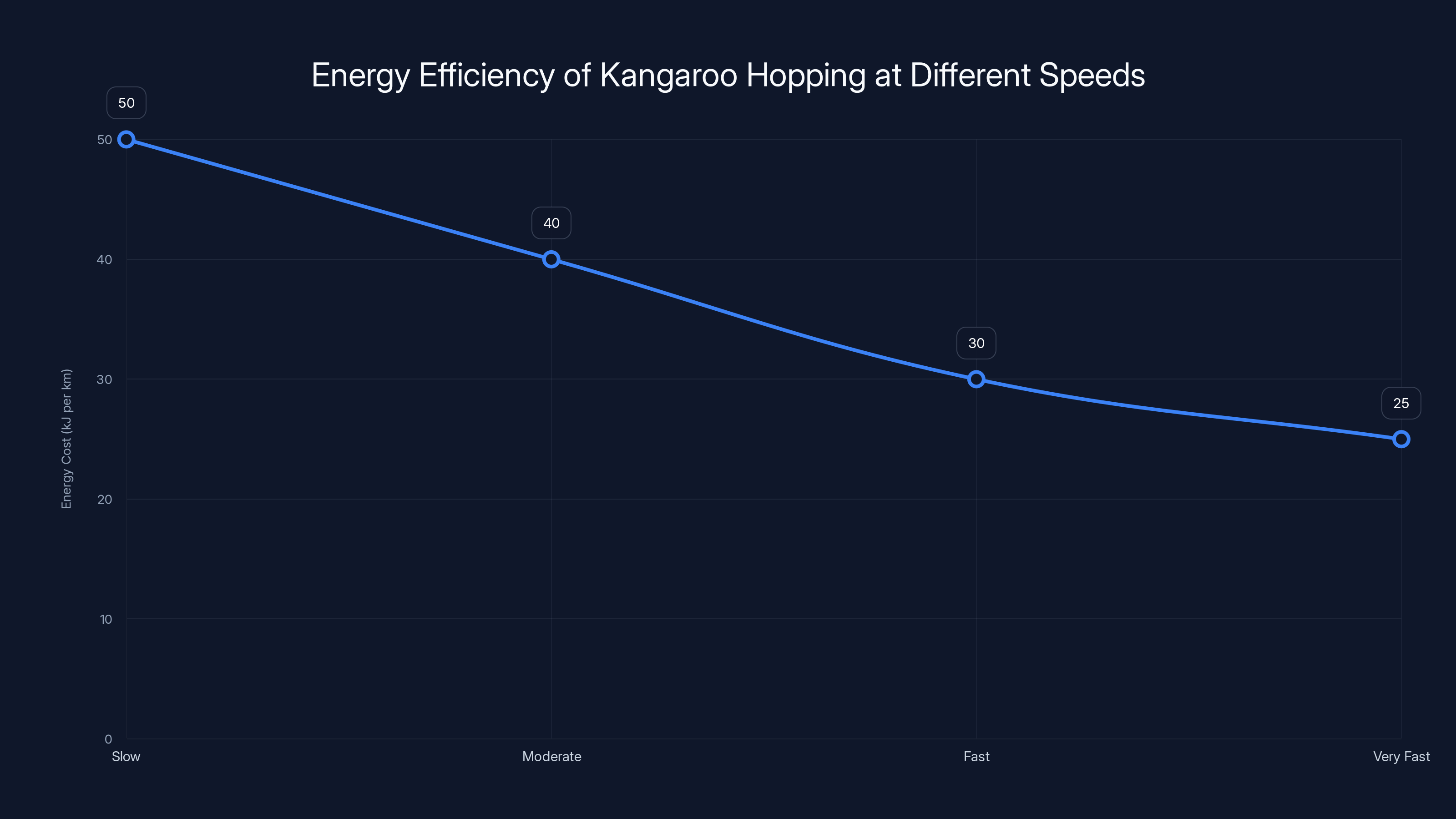

The Kangaroo Mystery: Why Hopping Gets More Efficient at Higher Speeds

Kangaroos are evolutionary oddities. They don't move like most mammals. Instead of galloping or trotting, they bounce. Their entire body launches into the air with each stride, suspended for a moment before landing and launching again. It's an unmistakably peculiar way to get around.

But here's what stumped biomechanists for decades: hopping should be exhausting. In most animals, faster movement requires more energy. A running human burns more calories than a walking human. A galloping horse requires more power than a trotting horse. Speed equals energy cost. That's how physics works.

Except with kangaroos, it doesn't.

Researchers studying red and grey kangaroos discovered something counterintuitive. As these animals increase their hopping speed, the energy required actually decreases. They get more efficient as they go faster. It's like finding a car that uses less fuel the harder you press the accelerator.

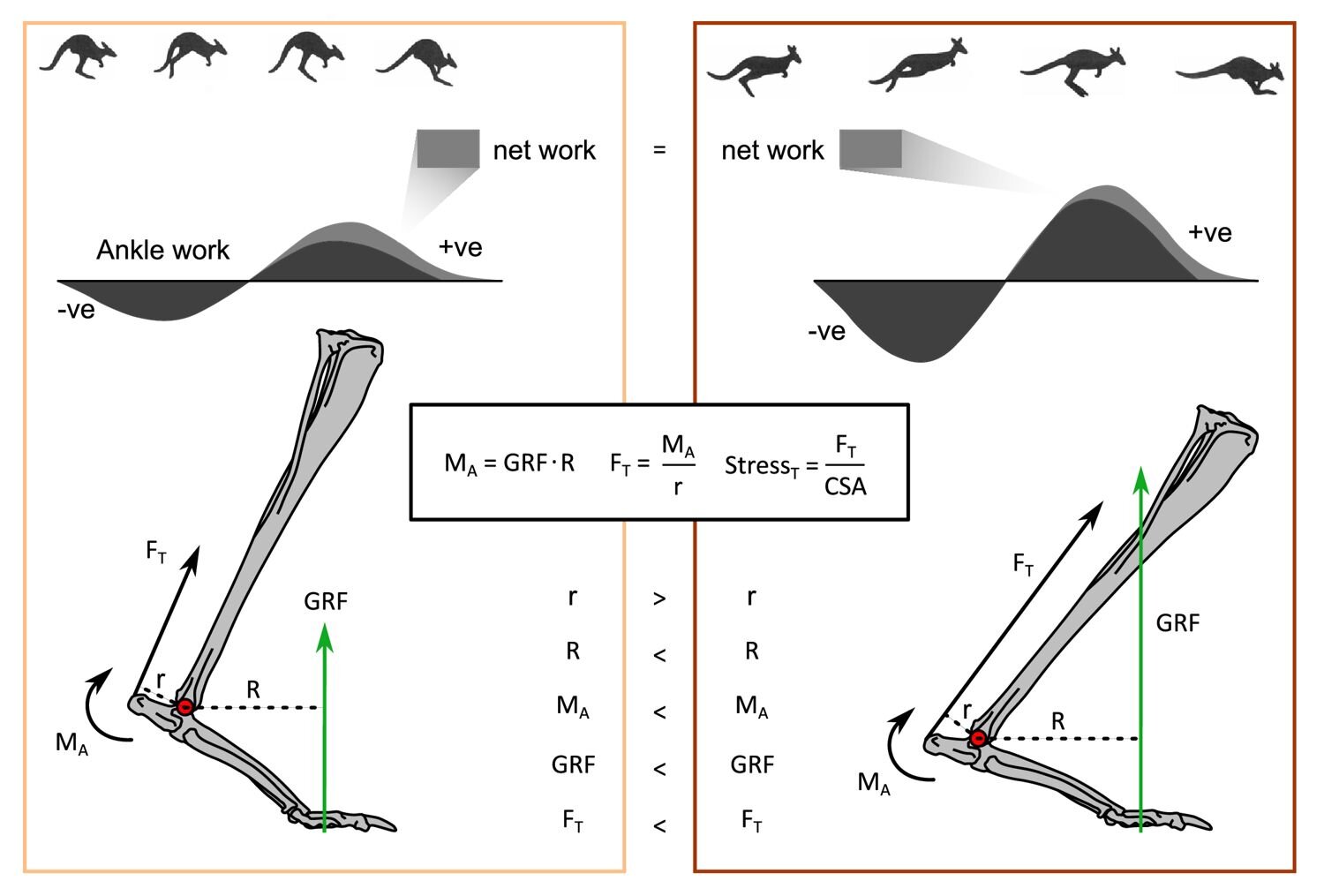

The puzzle deepened when scientists dug into the mechanics. To understand why, researchers used three-dimensional motion capture technology combined with force plates embedded in the ground. These sensors measured exactly where the kangaroo's feet landed, how much force they applied, and when contact occurred. Then came the detailed musculoskeletal modeling, recreating every joint, muscle, and tendon in virtual space.

What they found was elegant. As kangaroos increase their speed, they adjust their posture. Their hindlimbs become more crouched, more compressed, almost like loading a spring. The ankle joint bears increasingly more of the workload with each hop. This crouching position doesn't seem like it would help, but it fundamentally changes how energy flows through the system.

The key insight involves elastic energy storage. When a kangaroo's leg crouches before pushing off, the tendons and muscles stretch. This stretching stores elastic energy, like pulling back a rubber band. When the kangaroo extends its leg to jump, that stored elastic energy releases, reducing the amount of muscular effort required. The faster the hop, the more the kangaroo crouches, the more elastic energy stores, and the less muscle work becomes necessary.

It's a brilliant solution that evolution stumbled onto. By changing posture, kangaroos essentially let their tendons do the work instead of raw muscle. Muscle burns energy through chemical reactions. Tendons are passive structures that store and release mechanical energy with minimal metabolic cost. The faster the animal goes, the more it can rely on this passive elastic system, and the less it needs its muscles to work.

This discovery has implications beyond kangaroo biology. Engineers studying efficient locomotion, prosthetics designers building better artificial limbs, and roboticists creating hopping machines all stand to benefit. Understanding why kangaroos get more efficient at speed teaches us principles about energy use that apply far beyond the Australian outback.

Estimated data shows equal focus on various scientific discoveries, highlighting diverse research interests.

A Fossilized Bird's Final Meal: The Stones That Choked a Species

Palaeontologists at the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature in China stumbled upon something that initially seemed routine. Another fossilized bird from the Cretaceous period, 120 million years old, preserved in remarkable detail. But as researchers examined it more closely, something extraordinary became apparent.

Inside the bird's throat and esophagus were stones. Not a few stones. Not dozens of stones. Over 800 tiny pebbles, densely packed, lodged where they couldn't be swallowed or expelled.

The bird choked to death.

This isn't the first fossil showing a bird with stones in its digestive system. Many modern birds, including chickens and ducks, deliberately swallow small stones and gravel. These gastroliths, as scientists call them, end up in the gizzard, a specialized muscular chamber that grinds food using the stones as tools. It's like carrying a mortar and pestle inside your stomach. For birds without teeth, swallowing rocks is an elegant solution to breaking down tough food items like seeds and plant material.

But the researchers noticed something unusual about this fossil. They started analyzing previous CT scans of other fossilized birds and quantified exactly how many gizzard stones were typically present in healthy birds of this era. The pattern was consistent. Well-preserved fossils showed gizzard stones distributed in an organized cluster, concentrated in that grinding chamber.

This specimen was different. The stones in the newly discovered bird weren't located in the gizzard region. They were scattered throughout the esophagus, the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach. They were essentially stuck in the bird's throat.

Why would a bird swallow that many stones and lodge them in the wrong place? The researchers developed a hypothesis. The bird was sick. Paleontologists have documented that sick birds, particularly birds experiencing respiratory distress or other illnesses, sometimes eat stones. The behavior seems irrational, but it happens. The bird may have been suffering from a parasitic infection, an injury, or another condition that triggered unusual eating behavior.

When the bird attempted to regurgitate these stones, they became impacted. The stones couldn't come up, and they couldn't go down. The esophagus became completely obstructed. The bird suffocated or starved, unable to swallow food or water.

The fossil reveals the exact moment of death. This wasn't a bird that died peacefully in old age, buried gradually by sediment. This was a sudden death event, with the stones locked in place exactly where they'd been when the bird's heart stopped beating. The exceptional preservation captured a moment of tragedy frozen in stone.

The researchers named this species Chromeornis funkyi, an homage to the electronic music duo Chromeo. It's a fitting name for a bird whose death story is, in its own way, a bit funky.

But the significance goes deeper than just an unusual way to die. This fossil provides direct evidence of behavior in extinct species. It shows us that even birds living 120 million years ago exhibited complex responses to illness. It demonstrates that some behaviors, like eating stones when stressed or sick, have deep roots in bird evolution.

Dark matter is estimated to comprise about 85% of all matter in the universe, with visible matter making up only 5% and dark energy around 10%. Estimated data.

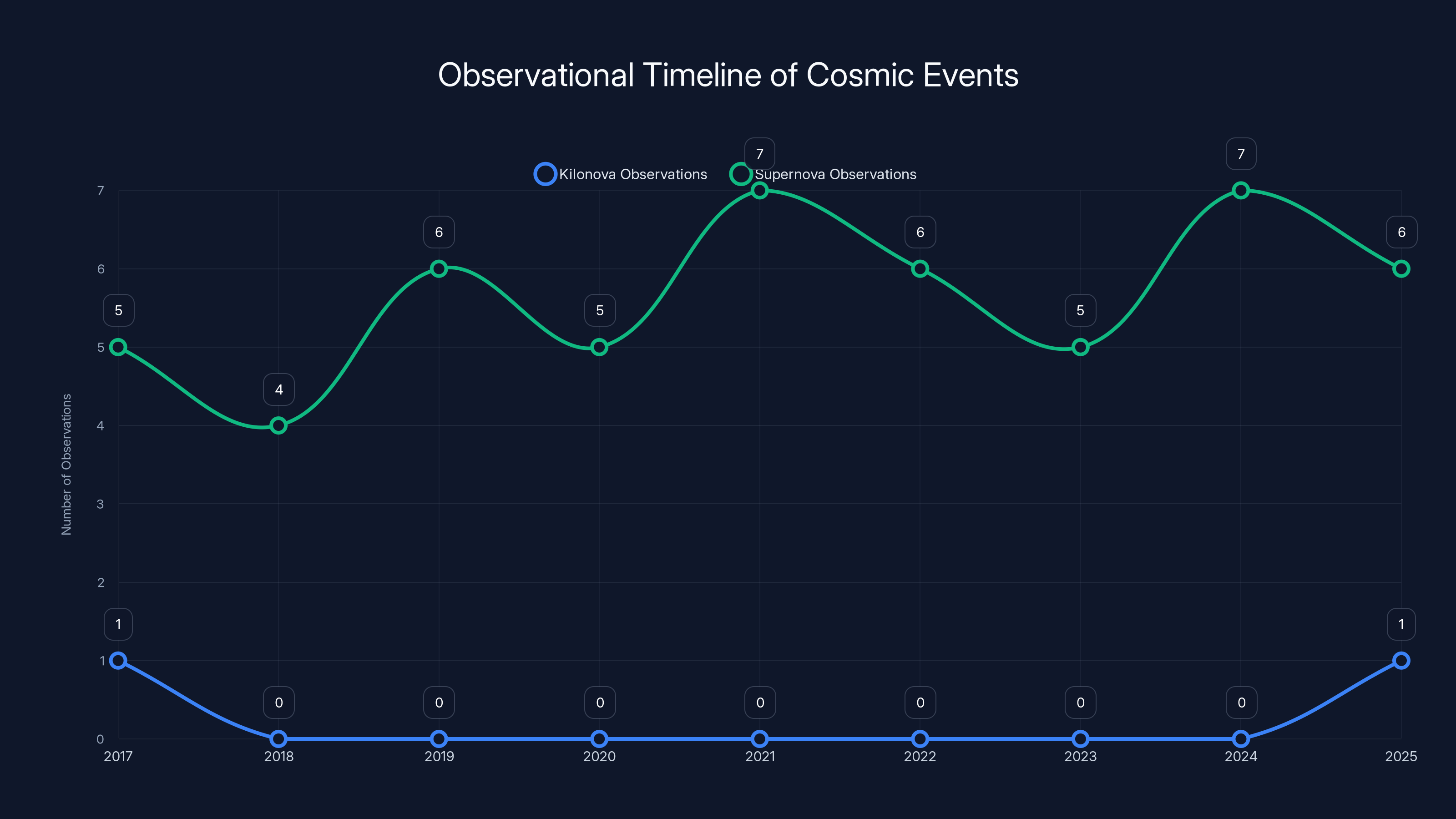

The Superkilonova: When a Supernova Births Twin Neutron Stars

In 2017, astronomers witnessed something that had never been directly observed before. Two neutron stars collided. The event created gravitational waves so powerful they rippled through spacetime itself, detectable by equipment on Earth. It also produced a burst of gamma rays, electromagnetic radiation traveling at light speed from the collision site. This event, called a kilonova, opened a new era in astronomy called multi-messenger astronomy. For the first time, scientists could observe a single cosmic event not just through light, but through gravity itself.

For years, the 2017 kilonova remained unique. Astronomers searched for similar events, hoping to find more examples. But kilonovae are rare. Binary neutron stars have to be precisely aligned, orbiting each other at just the right distance and speed, following a death spiral that culminates in collision. Finding even one is remarkable.

Then in 2025, another candidate appeared. Cataloged as AT2025ulz, this event initially resembled the 2017 kilonova. The spectral signature looked right. The timing seemed appropriate. But as weeks passed and telescopes continued observing, the characteristics began shifting.

AT2025ulz started looking more like a supernova. Supernovae are the tremendous explosions of massive dying stars, far more energetic than ordinary stellar deaths. A massive star eventually exhausts its nuclear fuel. Gravity collapses the core. Temperatures and pressures spike to extraordinary levels. The entire outer atmosphere of the star detonates in a thermonuclear explosion that can briefly outshine an entire galaxy of billions of stars.

But unlike a typical supernova, AT2025ulz didn't behave like a classic example. It shared characteristics of both supernovae and kilonovae, as if it were something in between. Something hybrid.

Astronomers from multiple research teams began collaborative analysis. They pulled data from multiple telescopes observing different wavelengths. They analyzed gravitational wave detections. They looked at radio observations. They examined X-ray and ultraviolet data. Each piece of evidence contributed to a puzzle that slowly revealed an extraordinary picture.

The conclusion stunned the field: AT2025ulz wasn't a simple supernova. It wasn't a straightforward kilonova. It was a multi-stage event. A supernova explosion, it appeared, had somehow created conditions that triggered the formation of two new neutron stars. These newly formed neutron stars then immediately began a death spiral, pulling toward each other. Within hours, they collided and merged.

This would be a superkilonova. A supernova that gives birth to twin neutron stars that immediately die together in a kilonova.

The evidence, while compelling, isn't yet definitive enough to declare victory. Finding one superkilonova candidate isn't the same as confirming the phenomenon. Scientists need more examples. But AT2025ulz provides a tantalizing preview of a type of event that exists at the intersection of stellar physics and relativistic physics.

The implications are profound. Supernovae are how heavy elements get created and distributed through space. The carbon in your body, the iron in your blood, the calcium in your bones—all forged in supernova explosions. If supernovae can spawn neutron stars that immediately collide, the process of element creation becomes even more complex and interesting than previously understood.

Reading an Ancient Fingerprint: The Hand That Touched a Bronze Age Ship

In the 4th century BCE, a military conflict erupted near the coast of Denmark. A small invasion force, approximately four boats strong, launched an attack against an island. The attack failed. The defending islanders emerged victorious and claimed their prize in an unusual way. They took one of the invading boats, loaded it with captured weapons, and deliberately sank it into a bog.

Thousands of years later, archaeologists discovered the submerged wreck. The anaerobic conditions of the bog had preserved it remarkably. The weapons remained. The wood of the boat survived. Even soft tissues can sometimes be preserved in bogs, though in this case, the boat was the primary artifact.

But there was something else. Among the preserved materials was something small and easy to overlook. A fragment of something that didn't seem important at first. A microscopic detail that most excavators might have dismissed.

A fingerprint.

Not a living hand, of course. But an impression, left by someone who'd handled an object in antiquity. The person's finger had pressed against something. Over millennia, that impression somehow survived. Preserved in the materials around it, captured like a ghost print from the Bronze Age.

This discovery is extraordinary because fingerprints almost never survive in the archaeological record. Fingerprints are made of skin cells and dried sweat and oils. These materials decay. They rot. They disappear into the bacterial and chemical processes that break down organic matter. Finding an intact fingerprint from 2,400 years ago isn't just rare. It's nearly impossible.

Yet here it was. A hand reached out and touched something in antiquity. That touch left a mark. That mark survived wars, conquests, cultural shifts, industrial revolutions, and modern history. It waited in a bog for thousands of years until someone noticed it.

The researchers carefully analyzed the fingerprint. Three-dimensional imaging revealed the ridge patterns, the whorls and loops and arches that define each person's unique pattern. The quality was good enough to compare against modern fingerprint databases and known reference materials. They attempted to determine if this was a sailor, a warrior, or someone involved in the conflict in some other way.

What they found was a snapshot of human history. This fingerprint belonged to someone. An actual individual who lived 2,400 years ago. Someone who touched a boat. Someone whose identity is forever unknown but whose physical presence was recorded in the most intimate way possible. Their fingertip, unique and personal, leaving a mark that persisted through time.

The fingerprint offers more than just fascination with ancient DNA or archaeological novelty. It represents a direct physical connection to an unknown person from millennia past. It's evidence that people in antiquity were people. They had unique bodies. They left marks. They touched things. Their fingerprints, like ours today, were one-of-a-kind patterns that no other human would ever replicate.

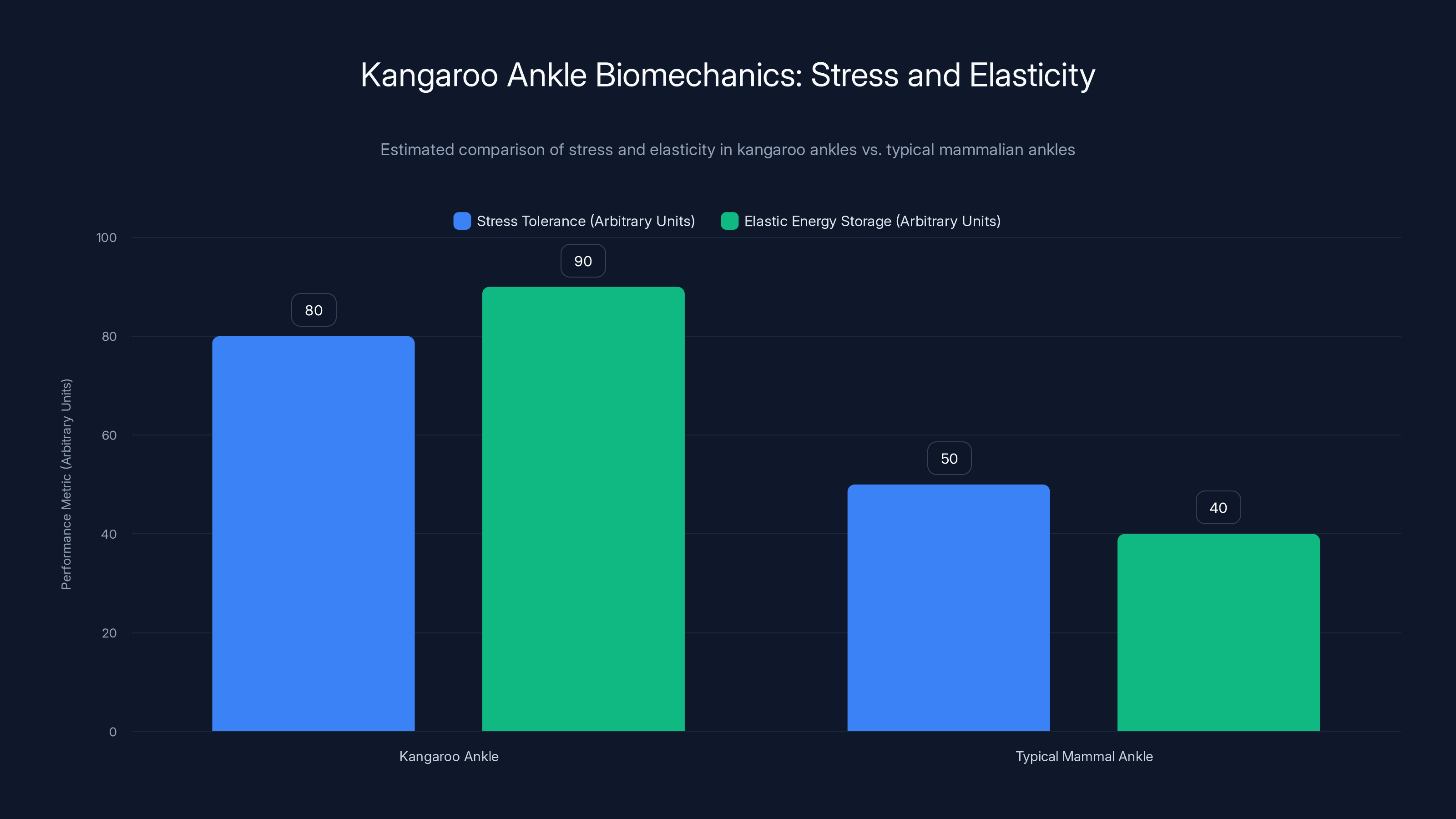

Kangaroo ankles exhibit higher stress tolerance and elastic energy storage compared to typical mammalian ankles, highlighting their evolutionary adaptation for efficient hopping. Estimated data.

Roman Burials in Liquid Gypsum: Preserving Bodies Through Chemistry

The Romans developed countless technologies and techniques that outpaced other civilizations. Concrete. Aqueducts. Roads that still exist today. Sanitation systems. But their burial practices varied widely across the empire and through different time periods.

Archaeologists working in a Roman cemetery site discovered something unexpected. Burials where the deceased had been placed in liquid gypsum. Not solid gypsum, carefully molded around the body. But liquid gypsum solution, poured into the grave, where it hardened around the corpse.

Gypsum is calcium sulfate. When mixed with water, it can form a slurry that slowly hardens into solid material. Modern construction uses gypsum drywall and joint compounds constantly. The Romans repurposed this material for burial purposes.

The effect of gypsum burial is profound. The mineral creates a nearly airtight seal around the body. Oxygen is excluded. Bacteria and fungi need oxygen to decompose organic matter efficiently. Without it, bodies preserved in gypsum don't rot. They mummify instead. The skin dries and leathers. Internal organs desiccate rather than liquefy and dissolve.

What's remarkable is how well preserved these bodies are. Researchers examining these Roman burials found details that normally disappear completely. Soft tissue. Hair. Sometimes even organs. Information that usually requires modern freeze-drying or museum conservation techniques somehow survived in the ground for millennia.

The Romans apparently recognized that gypsum could preserve bodies. The practice appears in specific burial contexts, suggesting intentional selection. This wasn't accidental. Someone made a conscious choice to pour liquid gypsum around the deceased.

Why? Several theories exist. Possibly as a mark of honor. Possibly for religious or spiritual reasons. Possibly as a practical preservation technique. The Romans were pragmatists. If something worked, they used it. They built roads to last. They designed buildings to survive. Perhaps they saw gypsum preservation as another way to make something endure.

These burials offer archaeologists exceptional information. Bodies preserved in gypsum provide details about Roman populations. Health status. Disease prevalence. Age at death. Skeletal markers of labor and injury. Information that helps reconstruct what life was actually like in Roman settlements.

The practice also raises questions about belief systems. Did Romans who chose gypsum burial believe it mattered for the afterlife? Did they think gypsum preservation extended the body's existence in some meaningful way? These questions can't be answered definitively from bones alone, but they hint at a Roman understanding of chemistry and preservation that deserves more recognition.

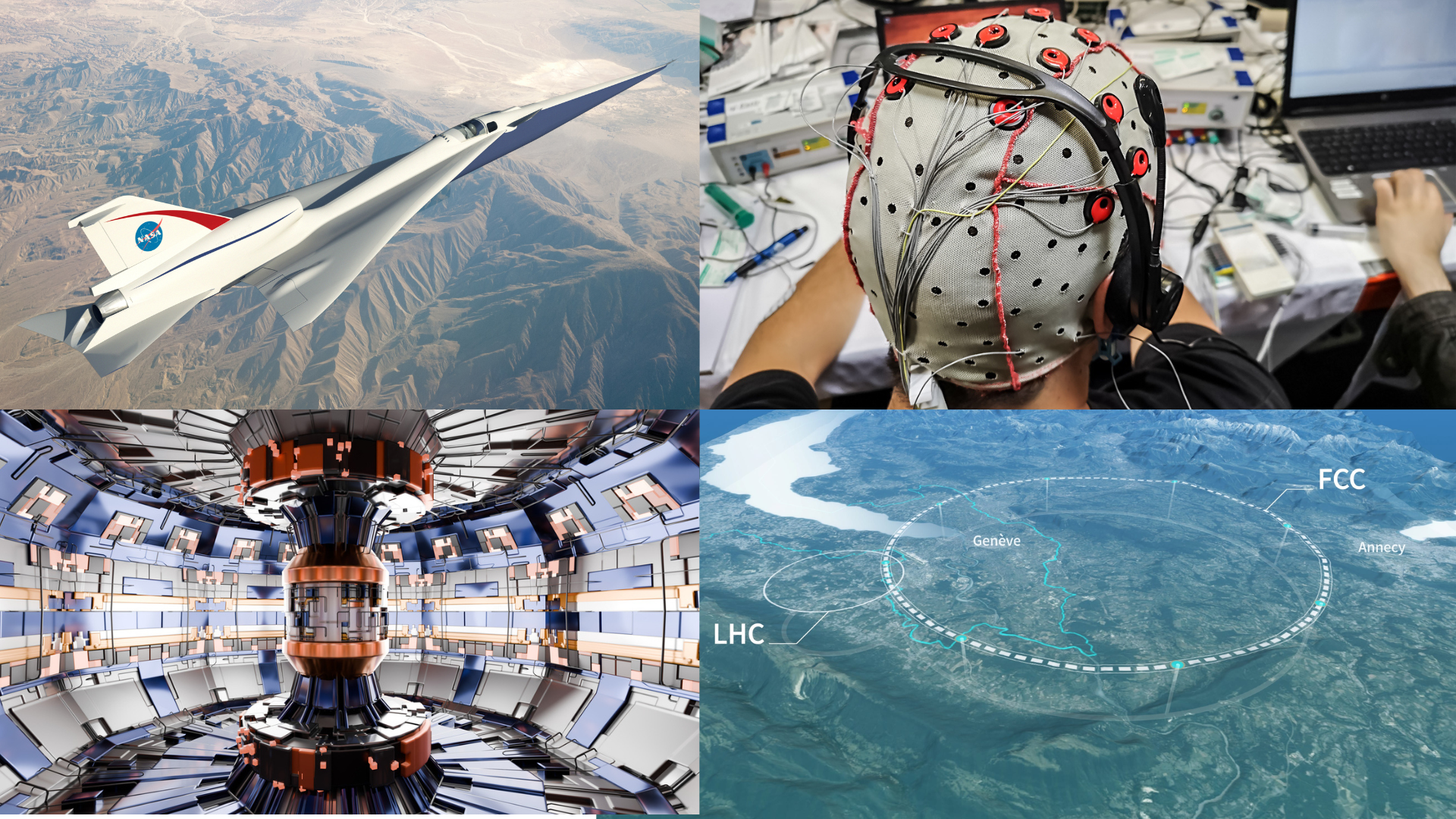

The Big Bang Theory Problem Solved: Dark Matter Puzzle Cracked

Fans of the television show "The Big Bang Theory" remember an episode where the fictional physicists struggled with a dark matter problem. The problem became a running joke throughout the series. It was presented as an unsolved mystery of physics, the kind of thing that would frustrate brilliant scientists.

Here's the weird part. That fictional problem was based on a real problem that actually puzzled real physicists.

Dark matter is one of cosmology's greatest mysteries. When astronomers measure how galaxies rotate, how galaxy clusters move through space, and how the universe expanded after the Big Bang, the math doesn't work. The visible matter—stars, planets, gas, dust—doesn't provide enough gravity to explain the observations. Galaxies should fly apart. Galaxy clusters should dissipate. The universe's expansion should look different.

Unless something else is there. Something invisible. Something that has mass and therefore gravity, but doesn't emit light. Something that doesn't interact with electromagnetic radiation. Scientists call this mysterious substance dark matter. It's estimated to comprise about 85% of all matter in the universe. We're surrounded by it. We're made partly of it. But we don't understand what it is.

The Big Bang Theory writers incorporated this real puzzle into their fictional plot. One of the characters struggled with a specific theoretical problem related to dark matter behavior. The show presented it as unsolved.

Then in 2025, a team of physicists announced progress. They didn't solve dark matter completely. That remains one of physics' greatest unsolved mysteries. But they solved the specific problem. The fictional problem became fictional no longer.

Researchers working with data from multiple astronomical surveys and new theoretical models made progress on understanding how dark matter distributes itself in the universe. They developed calculations that better matched observations. The equations started working. Predictions aligned with measurements.

It's not a complete victory. Dark matter's fundamental nature remains mysterious. We still don't know what dark matter particles are, if they're even particles at all, or how they behave at quantum scales. But the specific problem that puzzled the fictional physicists on television, the problem that made viewers laugh because it was so complicated, that problem moved closer to resolution.

The timing is almost poetic. The television show aired years ago, referencing a real problem that was genuinely unsolved. Now the problem has moved toward solution. The writers didn't know they were capturing a moment in physics history where one specific puzzle would eventually yield to concentrated research and new data.

As kangaroos increase their hopping speed, the energy cost decreases, demonstrating an unusual efficiency in their movement. Estimated data based on biomechanical studies.

Bird Choking Mechanisms: Why Stones Stick in Throats

The fossilized bird with stones in its esophagus raises broader questions about bird anatomy and swallowing mechanics. How exactly do birds swallow? What happens when swallowing goes wrong?

Birds have a unique throat structure. Their esophagus is a simple tube, stretching from the mouth to the stomach. Unlike mammals, birds don't have a complex throat with multiple passages and valves. This simplicity makes birds efficient at swallowing seeds and even whole insects.

But this same simplicity creates vulnerability. If something gets lodged in the esophagus, there's no alternative route. No mechanism to expel the blockage laterally. The bird can't cough effectively like mammals do. Many bird species lack a functional epiglottis, the flap that covers the windpipe during swallowing. They simply don't need it. Their swallowing mechanism evolved to be direct and efficient.

When a bird chokes, the situation becomes critical quickly. An esophageal blockage prevents food and water from reaching the stomach. The bird can't eat. It can't drink. It can't get nutrients. It can't cool itself through water consumption. In warm environments, dehydration becomes a medical emergency within hours.

The fossilized bird likely died within a day or two of the blockage occurring. In that timeframe, the impact of over 800 stones in the esophagus would have become absolutely fatal.

Modern birds sometimes face similar problems. Pet birds can choke on toys, bedding, or accidentally swallowed objects. Wild birds can aspirate food or become impacted by unusual items. Veterinary literature documents cases of birds choking on surprising things: plastic fibers, rubber bands, pieces of wood, insect carapaces.

The ancient bird's death represents a tragedy, but it also provides valuable information about bird behavior and vulnerability that illuminates both the ancient past and the modern day.

Gypsum as a Preservation Medium: Ancient Chemistry Rediscovered

Roman use of gypsum for burial preservation is fascinating from a materials science perspective. Gypsum is chemically stable. It doesn't degrade significantly over time. It remains chemically inert in soil, resisting breakdown from moisture or bacterial action.

When liquid gypsum is poured around a body, it hardens as it dries. The gypsum crystals form a solid matrix that excludes oxygen and moisture fluctuations. This creates a microenvironment where normal decomposition processes can't proceed efficiently.

Moist soil normally promotes bacterial and fungal growth. These microorganisms break down organic matter through enzymatic processes. Gypsum's relative dryness and chemical inertness prevents this biological breakdown. The body doesn't rot in the traditional sense. Instead, it slowly desiccates, leathering and shrinking as water content decreases over years and decades.

What's remarkable is how completely gypsum burial preserves soft tissues. Hair remains. Skin maintains pigmentation. Organs can preserve enough detail for medical examination thousands of years later. It's roughly equivalent to modern mummification techniques, except achieved entirely through accidental environmental chemistry.

The Romans didn't have scientific understanding of bacterial decomposition or anoxic preservation. They couldn't have explained the biochemistry of why gypsum burial worked. But they observed that it did work. Bodies in gypsum burials looked better preserved after exhumation than bodies in regular graves. The Romans were pragmatists. If something worked, they used it.

This demonstrates how practical observation precedes theoretical understanding. The Romans mastered the technique without understanding the mechanism. Only modern science can explain why gypsum preserves bodies so effectively.

The implication is humbling. How many practical techniques do we use today without understanding their deep mechanisms? How many things in modern life work for reasons we don't actually comprehend?

The choked bird fossil had an unusually high number of stones (800) compared to typical healthy bird fossils (45-60), suggesting a possible illness or anomaly. Estimated data.

Kangaroo Ankle Biomechanics: Engineering Lessons from Evolution

The kangaroo research revealed that as hoppers increase speed, the ankle joint bears increasingly more stress and workload. The ankle isn't just supporting the body weight and pushing off the ground. It's also the primary structure responsible for storing and releasing elastic energy.

This arrangement seems counterintuitive. The ankle is a relatively small joint. It seems fragile. Loading more stress onto it as speed increases seems like it would lead to injury. Yet kangaroos hop at speeds exceeding 50 kilometers per hour, sometimes maintaining those speeds for extended distances.

The answer lies in specialized tendon and ligament structures. Kangaroo ankles have evolved thicker, stronger tendons than most mammals of equivalent size. These tendons are optimized for elastic energy storage and recovery. They're not just supporting structures. They're active participants in locomotion.

The Achilles tendon, which connects the calf muscle to the heel bone, is particularly important. In kangaroos, this tendon is exceptionally strong and elastic. As the kangaroo prepares to hop, the Achilles tendon stretches. During the jump, it releases that stored energy explosively. This works repeatedly, hop after hop, with minimal fatigue.

This design principle has engineering applications. Prosthetics manufacturers have started incorporating spring-like materials in artificial ankles, mimicking the kangaroo's elastic system. Athletes wearing specialized running blades with spring-like properties can jump higher and run faster than they could with rigid prosthetics.

Robots designed for hopping locomotion perform better when they include elastic elements in their leg design. Rigid legs require constant muscular (or motorized) effort. Elastic legs store and release energy, reducing power consumption.

Evolution solved this problem millions of years ago. Kangaroos are living demonstrations of optimal leg design for hopping locomotion. By studying them, humans gain insights into efficiency, energy management, and stress distribution that apply far beyond biology.

Ancient Seafaring and Chemical Preservation: The Bronze Age Connection

The fingerprint preserved from the Bronze Age sailor or invader represents a direct link to ancient seafaring populations. Maritime history usually leaves limited evidence. Wooden boats decay. Textiles rot. Most organic evidence disappears over centuries.

Yet this fingerprint survived. The same anaerobic bog environment that preserved the boat also preserved this intimate human detail.

Bogs are extraordinary preservative environments. The waterlogged, oxygen-depleted conditions inhibit bacterial growth. Peat, the accumulation of dead plant material, is acidic and creates conditions hostile to decomposition. Bodies and artifacts buried in bogs can survive for millennia with remarkable preservation.

This particular bog burial demonstrates the technology and logistics of Bronze Age seafaring. Someone had to build these boats. Someone had to sail them. Someone had to conduct military operations with them. The fingerprint is evidence that these were skilled individuals, perhaps craftspeople or warriors, who engaged in sophisticated maritime activities.

The preserved fingerprint also raises questions about preservation chemistry. How did the impression survive? What chemical or physical process locked the pattern into place? Modern science can examine the fingerprint in detail, but the exact mechanisms of preservation remain partially mysterious.

Archaeologists treat anaerobic bog burials as time capsules. Bodies found in bogs have revealed information about Iron Age peoples, Celtic populations, and other ancient groups. Stomach contents show what people ate. Isotope analysis reveals migration patterns. Body position indicates rituals surrounding death.

The fingerprint adds another layer. It's not just evidence of a person. It's evidence of a specific moment. Someone touched something while aboard or near a boat during a Bronze Age conflict. That touch was recorded in microscopic detail.

The 2017 kilonova was a unique event until 2025, when another candidate, AT2025ulz, was observed. Supernovae are more frequently observed, with several detected each year. Estimated data.

Multi-Messenger Astronomy: Reading the Universe Through Multiple Eyes

The superkilonova discovery exemplifies modern astronomy's revolutionary shift toward multi-messenger observation. For most of human history, astronomy meant light. Telescopes collected photons. Astronomers interpreted what the light revealed.

Light is wonderful but limited. It travels in straight lines. It gets absorbed by dust and gas. It reveals only what happens to emit or reflect photons. Vast cosmic dramas proceed invisibly if they don't produce light.

Then in 2015, the first direct detection of gravitational waves opened new observational channels. Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime itself, created by accelerating massive objects. They travel at light speed, pass through intervening matter unimpeded, and carry information about the source event.

A neutron star collision produces both light and gravitational waves. By observing both simultaneously, astronomers gain complete information. The gravitational wave arrival time indicates when the collision occurred. The intensity indicates the masses involved. The wave pattern indicates the orbital mechanics. Meanwhile, the light observations reveal the composition of ejected material, the temperature of the explosion, and the chemical processes occurring in the debris.

AT2025ulz presented a puzzle precisely because it had characteristics unusual enough that light observations alone couldn't definitively classify it. It looked like a supernova in some wavelengths, a kilonova in others. The gravitational wave data, combined with observations across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, eventually revealed the true nature: a multi-stage event involving both stellar explosion and neutron star merger.

This multi-messenger approach is becoming standard. Future astronomical discoveries will come from synthesizing information from light, gravity, particles, and potentially other messengers scientists are currently developing detection methods for.

The implication is profound. The universe is far more complex than what light alone reveals. By adding new observational channels, astronomy enters a new era where we can see phenomena previously invisible.

Paleontology's Window into Prehistoric Suffering: What Fossils Reveal About Death

The fossilized choking bird represents something that paleontologists value: preserved evidence of how organisms actually died and lived. Most fossils form through rapid burial and mineralization. The organism dies, gets buried quickly, and gradually becomes stone. The specific circumstances of death are usually lost.

But occasionally, the circumstances are preserved. A bird with 800 stones in its throat isn't just any fossil. It's a record of suffering. A moment of medical distress captured in mineralized form.

This tells paleontologists that organisms of the past experienced illness, pain, and misfortune just as modern animals do. The choking bird wasn't a healthy specimen that happened to die of old age. It was a sick animal that made a desperate or irrational decision. That decision proved fatal.

Other fossils tell similar stories. Dinosaur fossils with healed fractures show that some animals survived injuries. Some fractured bones healed but improperly, suggesting the animal lived with disability afterward. Some fossils show evidence of infection or disease.

These discoveries humanize the fossil record. We don't just see dead organisms. We see lives interrupted by circumstance. We see suffering and survival. We see that the struggles of living creatures weren't unique to the modern era. Death by choking isn't a modern phenomenon. Broken bones don't heal perfectly. Infection causes swelling and fever. Disease ravages populations.

The bird fossil is particularly valuable because the cause of death is so clear. No ambiguity about whether the stones caused death. The blockage is visible. The bird couldn't have survived with such an obstruction.

Why These Stories Matter: The Bigger Picture

These seven discoveries might seem disconnected. A hopping marsupial. An ancient fingerprint. A cosmic explosion. A choking bird. Buried Roman bodies. A dark matter calculation. A preserved seafarer.

But they share something important. Each represents human curiosity applied to genuine mysteries. Each story required observation, data collection, analysis, and careful reasoning. Each revealed something previously unknown.

Science works because scientists are puzzled by things. They see an anomaly. A kangaroo that defies energy logic. A bird with stones in its throat. A supernova that behaves like a kilonova. A dark matter problem that won't go away. An ancient fingerprint preserved in mud.

These puzzles shouldn't exist. Reality should be straightforward. But it isn't. Reality is complicated and strange and full of surprises. That strangeness is where science happens.

The discoveries also demonstrate the power of careful observation and documentation. The kangaroo research required precise motion capture technology and biomechanical modeling. The bird fossil required detailed CT scans and comparative analysis. The dark matter problem required cosmological data from multiple sources. The fingerprint required 3D imaging technology developed for modern purposes but applied to ancient artifacts.

Science accumulates tools, techniques, and knowledge. Each generation inherits the discoveries and equipment of previous generations and builds further. An ancient fingerprint remains invisible until someone invents technology to image it. A bird's stomach contents remain meaningless until someone develops CT scanning. Kangaroo movement remains mysterious until someone builds force plate sensors and motion capture systems.

Progress depends on both tools and questions. You need the technology to observe. But you also need someone asking the right questions. Someone wondering why kangaroos violate the normal energy rules. Someone noticing stones in a bird's throat. Someone looking at ancient artifacts and wondering what secrets they might still hold.

These seven stories are bookmarks. They mark moments where curiosity met opportunity. They mark discoveries that remind us the world is stranger, more complicated, and more wonderful than we typically acknowledge.

The Future of Discovery: What These Findings Point Toward

If the past year's discoveries hold any lesson, it's that the world remains full of unsolved mysteries and unexpected phenomena. We've barely scratched the surface of understanding how animals move, how the cosmos works, how ancient peoples lived, or what physical processes drive planetary systems.

The kangaroo research opens new questions about locomotion in other hopping animals. Can insects optimize their hopping similarly? How do frogs compare? Could the insights apply to extraterrestrial biomechanics if we ever encounter life on other worlds?

The bird fossil raises questions about behavioral ecology in extinct species. Can we recognize stress responses in fossil records? Can we document disease and illness? Can bones and preserved materials tell us not just how animals died, but what their lives were actually like?

The superkilonova discovery suggests that our cosmic models remain incomplete. What else is happening in the universe that doesn't fit our current categories? How many hybrid phenomena exist between traditional classifications? As more sensitive detection equipment comes online, will we find superkilonovae are common or remain extraordinarily rare?

The dark matter progress suggests that years of accumulated data and theoretical work can eventually crack seemingly intractable problems. What other long-standing physics puzzles might yield to sufficient data and computational power?

The ancient fingerprint points to preservation techniques and chemical processes we don't fully understand. Can similar methods be applied to deliberately preserve other materials? Could future preservation techniques save information we currently consider lost forever?

These questions point toward future research. Future discoveries will build on these 2025 findings. Someone, somewhere, is probably right now beginning a research project that will eventually crack another mystery, solve another puzzle, reveal something the world didn't know.

That's how science works. One discovery raises new questions. Those questions motivate research. That research yields data. The data suggests new hypotheses. The cycle continues. Progress compounds.

We live in an era of extraordinary scientific capability. We have telescopes that can image faint objects from the dawn of the universe. We have sensors that can detect the passage of gravity waves through spacetime. We have computing power to process massive datasets. We have imaging technology that reveals hidden details. We have tools our ancestors couldn't have imagined.

Yet with all these tools, we're still discovering things that surprise us. We're still finding phenomena that don't fit our models. We're still uncovering mysteries that require decades of concentrated research to understand.

That's beautiful. That's what makes science worth doing.

Conclusion: The Stories Behind the Stories

Science isn't just facts and figures. It's human stories of curiosity, persistence, and discovery. These seven stories are human stories as much as they are scientific stories.

They're stories of researchers who asked good questions and kept asking them even when answers didn't come immediately. They're stories of international collaboration, with teams from different countries working on shared mysteries. They're stories of careful observation and documentation, preserving data for future analysis. They're stories of intuition and analysis combined, where a hunch about kangaroo posture led to biomechanical models that reveal universal principles about efficiency.

Most of these discoveries didn't make international news headlines. They appeared in specialized journals read by experts in narrow fields. They got cited in academic papers. They moved from specialization toward broader awareness gradually. But they deserved more attention. They deserve to be known and remembered as significant advances in human understanding.

The world is full of people asking questions and conducting research. The vast majority of that work never reaches general awareness. Papers get published. Discoveries get made. Life continues. The discoveries accumulate, layer upon layer, building toward larger syntheses and breakthroughs.

These seven stories represent a tiny fraction of the research happening right now across the planet. In laboratories and field sites, in astronomical observatories and paleontological digs, in theoretical offices and computational centers, thousands of researchers are pursuing mysteries. Some will find answers. Most will raise new questions. All of it contributes to the slow, steady advance of human knowledge.

That's why these stories matter. Not just because they're interesting, though they are. But because they represent the process of science itself. They show how curiosity drives investigation. How observation reveals nature's secrets. How careful analysis can crack puzzles that seemed intractable.

The kangaroo teaches us about efficient movement. The fossilized bird teaches us about ancient life and death. The superkilonova teaches us about cosmic processes we're still learning to interpret. The ancient fingerprint teaches us that humanity stretches back through millennia, leaving marks that survive. The Roman gypsum burials teach us that ancient peoples understood chemistry better than we sometimes give them credit for. The dark matter progress reminds us that seemingly unsolvable problems sometimes yield to new data and fresh theoretical approaches.

But perhaps most importantly, these stories remind us that the world remains mysterious. For all our knowledge and technology, we're still discovering things that surprise us. We're still finding phenomena that don't fit our models. We're still uncovering evidence that previous generations couldn't imagine.

That mystery is precious. It's the reason science continues. It's the reason researchers pursue questions despite obstacles and setbacks. It's the reason we look at the world and ask, "But why? How does that work? What does this mean?"

These seven stories happened in 2025. By the time you read them, they may have already been superseded by more recent discoveries. New mysteries will have emerged. New questions will have been asked. That's fine. That's how progress works.

But for a moment, consider these stories. A choking bird. A dancing kangaroo. An ancient touch. A cosmic explosion. A preserved Roman burial. A dark matter puzzle solved. An impossible fingerprint from the deep past.

Each one is a window into a world more complex and wonderful than we typically recognize. Each one deserves your attention and amazement.

FAQ

What is the significance of the fossilized bird with stones in its esophagus?

This fossil, approximately 120 million years old, is the first known specimen of a bird that choked to death on stones lodged in its throat. The discovery is significant because it provides direct evidence of illness-related behavior in extinct species, showing that ancient birds exhibited responses to stress similar to modern birds, and demonstrates how behavioral patterns can be preserved in the fossil record for millions of years.

How do kangaroos achieve greater efficiency at higher hopping speeds?

Kangaroos adjust their posture by becoming more crouched as they increase speed, which loads elastic energy into their ankle tendons. This elastic energy is released during jumping, reducing the muscular effort required and making hopping more energy-efficient at higher speeds. This principle of elastic energy storage and recovery is now being applied to prosthetics and robotic locomotion design.

What is a superkilonova and why is AT2025ulz significant?

A superkilonova is a rare multi-stage cosmic event where a supernova explosion creates conditions that form two new neutron stars, which then immediately collide in a kilonova. AT2025ulz appears to be the first confirmed example, providing evidence that such hybrid events exist and offering insight into stellar death processes and element creation in the universe.

How was an ancient fingerprint preserved for 2,400 years?

The fingerprint was preserved in anaerobic bog conditions that exclude oxygen and inhibit bacterial decomposition. The waterlogged, acidic environment of the bog created near-perfect preservation conditions, allowing microscopic details of the fingerprint to survive from the Bronze Age until discovery by modern archaeologists using advanced imaging technology.

Why did Romans use liquid gypsum for burials?

When poured around bodies, liquid gypsum creates an airtight seal that excludes oxygen and moisture. This prevents the bacterial and fungal decomposition that normally occurs, allowing bodies to desiccate naturally instead of rotting. The Romans recognized this practical benefit empirically, even though they didn't understand the underlying chemistry of anaerobic preservation.

What was the dark matter problem that appeared on The Big Bang Theory?

The fictional problem on the television show was based on a real theoretical puzzle in cosmology related to how dark matter distributes itself in the universe and affects large-scale cosmic structure. In 2025, researchers made significant progress on this specific problem using new data and theoretical models, moving it closer to resolution after years of being one of physics' unsolved mysteries.

How do paleontologists determine causes of death from fossils?

Paleontologists examine fossils for physical evidence of trauma, obstruction, disease, or injury. In the case of the choking bird, CT scans revealed over 800 stones lodged in the esophagus, making the cause of death evident. By comparing fossil specimens with modern examples and using imaging technology, paleontologists can reconstruct not just how organisms died, but what their final moments likely involved.

What does multi-messenger astronomy mean and why is it important?

Multi-messenger astronomy uses multiple detection channels (gravitational waves, light across all wavelengths, particles) to observe a single cosmic event. This provides complete information that light observations alone cannot give. For the superkilonova discovery, gravitational wave data combined with electromagnetic observations definitively revealed the hybrid nature of the event.

What can kangaroo biomechanics teach us about engineering and design?

Kangaroo ankle structure and tendon systems exemplify optimal design for efficient hopping. Engineers have applied these principles to prosthetics with elastic components, running blades, and robotic legs designed for hopping locomotion. Understanding how evolution optimized movement patterns provides design inspiration for human technology.

Why are bog burials so valuable for archaeology?

Anaerobic bog conditions create exceptional preservation environments that exclude oxygen and inhibit decomposition. Organic materials—textiles, wood, skin, soft tissues, food remains—survive in bogs for thousands of years with remarkable detail. This allows archaeologists to recover information about daily life, diet, health, and cultural practices that would otherwise be completely lost to decay.

Key Takeaways

- Kangaroos violate normal energy rules by becoming more efficient at higher speeds through crouched posture and elastic tendon storage

- A fossilized bird with 800 stones in its esophagus provides rare direct evidence of illness-related behavior in extinct species

- AT2025ulz represents the first confirmed superkilonova, a hybrid cosmic event where a supernova creates and immediately merges neutron stars

- Ancient fingerprints can survive 2,400 years in anaerobic bog conditions, providing direct physical connection to Bronze Age individuals

- Roman liquid gypsum burials created exceptional preservation through anaerobic chemistry principles the Romans understood empirically

- A real physics dark matter problem that stumped fictional characters on The Big Bang Theory moved closer to resolution in 2025

- Multi-messenger astronomy combining gravitational waves, light, and particle data reveals cosmic phenomena invisible to traditional observation methods

Related Articles

- How to Watch Hyundai's CES 2026 Presentation Live [2025]

- Tech Trends 2025: AI, Phones, Computing & Gaming Year Review

- ASUS RP-AX58 Wi-Fi 6 Range Extender Review [2025]

- 14 Most Anticipated Games of 2026: Beyond GTA 6 [2025]

- Audio AI: Why Tech Giants Are Betting on Voice Over Screens [2025]

- LG's AI-Powered Karaoke Speaker: The Stage 501 Explained [2025]

![7 Mind-Bending Science Stories You Nearly Missed [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/7-mind-bending-science-stories-you-nearly-missed-2025/image-1-1767297974405.jpg)