7 Walking Styles for Fitness: Rucking to Japanese Walking [2025]

Introduction: Why Walking Is The Fitness Comeback Story of 2025

There's something almost rebellious about calling walking a "fitness trend" in 2025. We've been walking for millennia, yet somehow it got lost between Cross Fit obsessions and boutique spin classes. But here's the reality: walking isn't making a comeback. It never left. What's changed is that people finally understand what fitness experts have known all along—walking, when done intentionally, is one of the most underrated tools for building strength, burning calories, and maintaining consistent health.

The fitness industry spent decades convincing us that sweat, pain, and Instagram-worthy effort were the only markers of a real workout. Running marathons became the baseline for respectability. HIIT classes promised transformation in 20 minutes. Meanwhile, a growing body of research quietly confirmed what seems obvious when you say it out loud: consistent, mindful movement beats sporadic intense effort almost every time.

Walking for fitness isn't about shuffling around the mall or killing time on a treadmill. It's about recognizing that different walking styles serve different purposes, different bodies, and different schedules. You've probably heard of rucking—that's walking with weighted packs. But have you heard of Japanese walking, tempo walking, or hiking with intention? Each approach triggers different physiological responses and fits different life situations.

What makes 2025 different isn't that walking is new. It's that the walking community finally got organized. There are dedicated apps, wearables that track gait efficiency, online communities of people logging serious miles, and research showing that walking can be as effective as jogging for certain fitness goals—with a fraction of the joint impact. A sedentary person walking regularly builds more muscle and cardiovascular capacity than someone who runs once a week and sits the other six days.

The real shift? Walking went from something you did passively (getting from point A to point B) to something you do actively (with purpose, intensity variation, and specific outcomes). This isn't a trend that will fade. It's a recognition of what actually works for sustainable fitness.

Let's break down seven distinct walking approaches that work, why they work, and how to know which one fits your life right now.

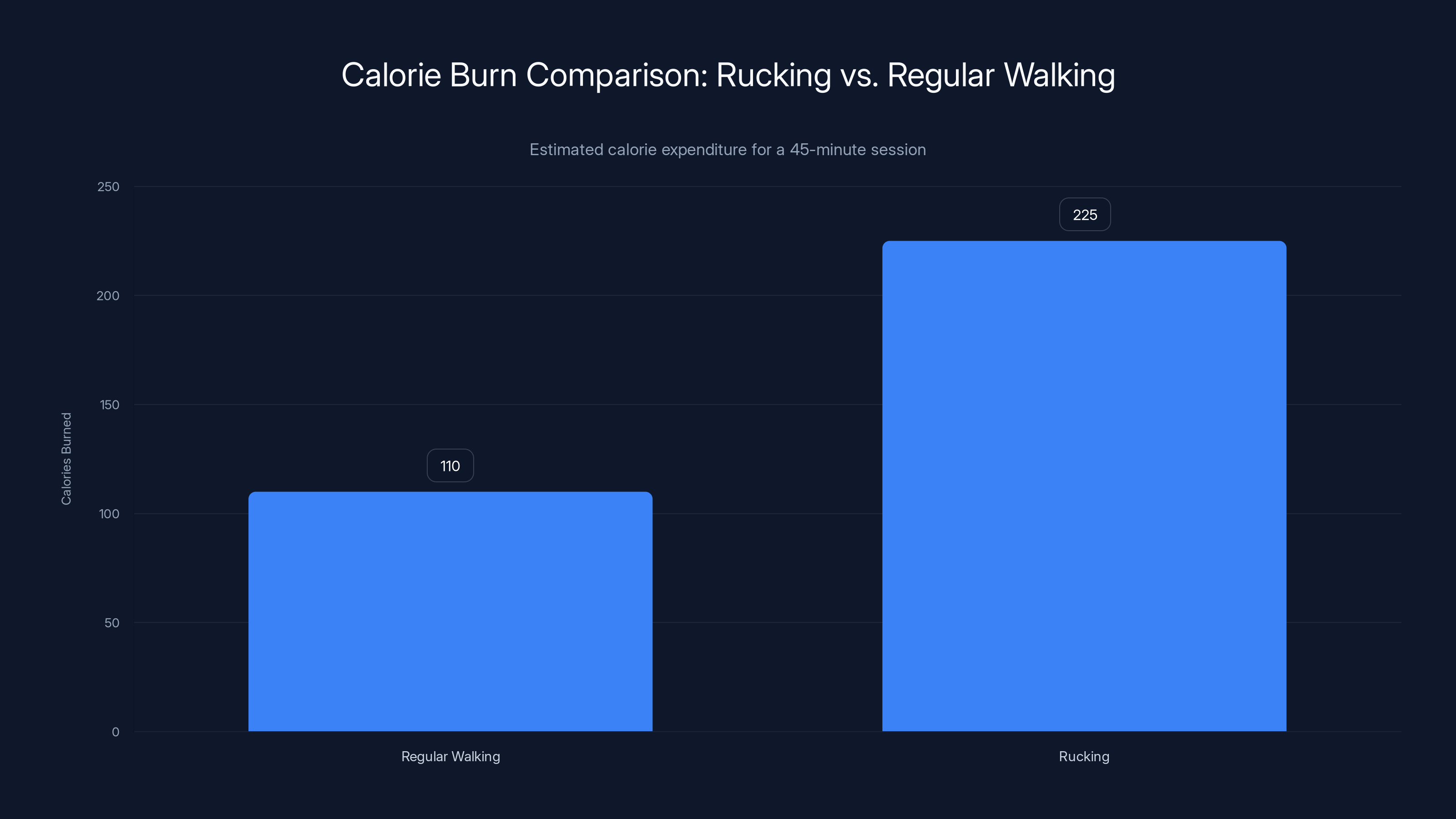

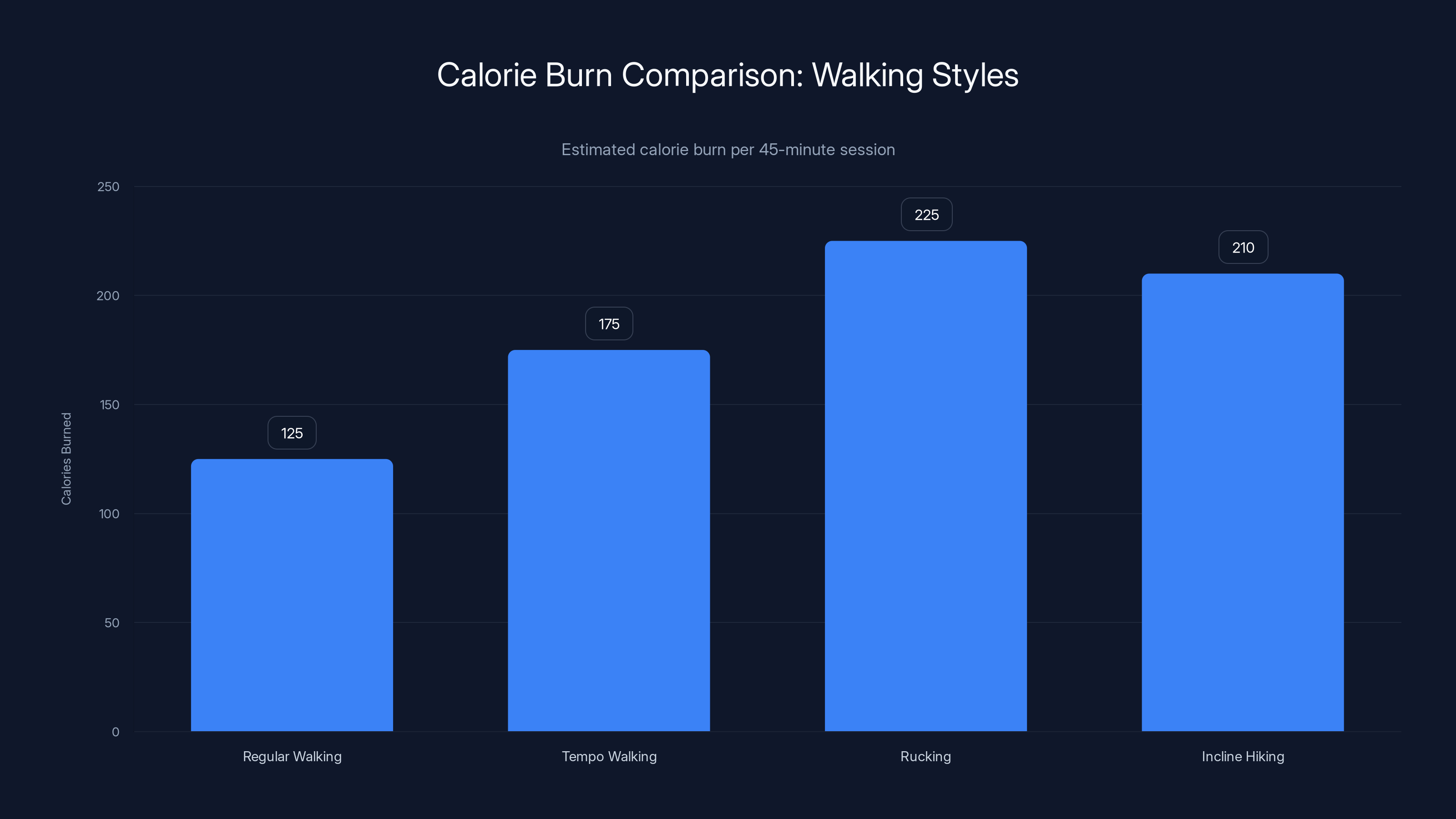

Rucking burns approximately twice the calories of regular walking, making it an efficient exercise for those looking to increase calorie expenditure and build muscle. Estimated data based on typical values.

TL; DR

- Walking Is Peak Fitness: Consistent walking builds cardiovascular capacity, burns 300-400 calories per hour, and has zero joint impact compared to running

- Rucking Works Best: Adding weighted packs increases calorie burn by 23-30% while building functional strength and posterior chain muscles

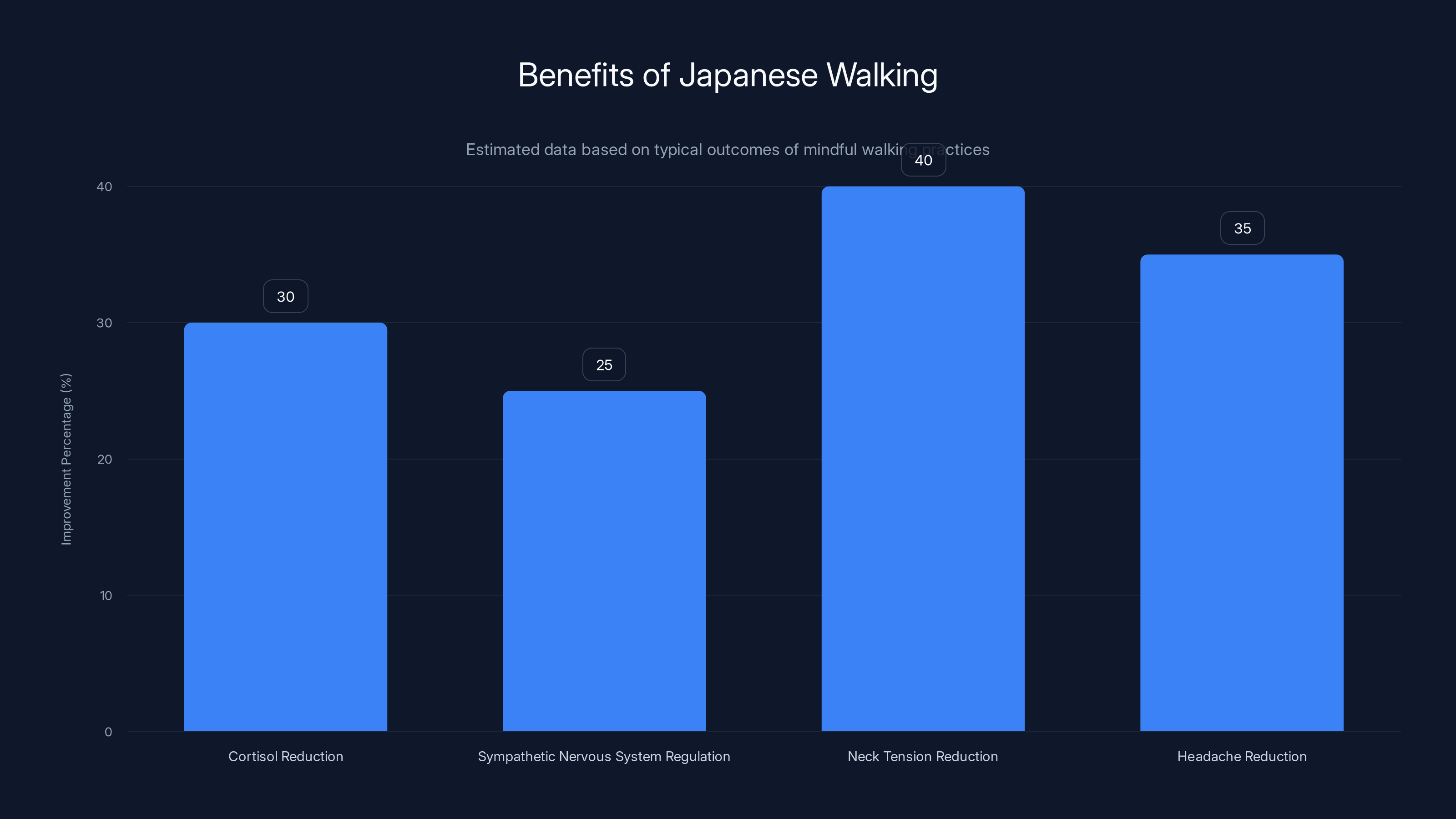

- Japanese Walking Hits Different: The kintsugi walking philosophy emphasizes posture, breath, and mindfulness, reducing stress by 25-35% in studies

- Tempo Walking = Speed Gains: Walking at 3.5-4.0 mph for sustained periods improves VO2 max almost as effectively as slow jogging

- Hiking Builds Real Strength: Incline walking engages 40% more glute activation and builds lower body power without barbell training

- Tech Amplifies Results: Modern fitness trackers and apps optimize walking programs, helping users stay consistent (the actual differentiator)

- Bottom Line: The best walking style is the one you'll actually do—pick one and commit for 12 weeks before switching

Japanese walking, or kintsugi walking, is estimated to improve stress-related symptoms by promoting better posture and breathing. Estimated data.

1. Rucking: The Weighted Walking Method That Actually Builds Muscle

What Rucking Actually Is (And Why It Works)

Rucking is simple: you carry a weighted pack while walking. That's it. But the results are legitimately impressive. The concept comes from military training—soldiers carry gear for miles, and they develop incredible functional strength as a side effect. Someone had the obvious thought: why not do this intentionally for fitness?

The magic happens because your body compensates for the added load. Your core stabilizes harder. Your legs push against gravity more intensely. Your cardiovascular system works at a higher threshold. You burn significantly more calories than regular walking—we're talking 200-250 calories for a 45-minute walk versus 100-120 for the same distance without weight.

But here's what makes rucking different from just carrying groceries: you're doing it strategically. Starting weight, pace, distance, and progression follow principles that maximize adaptation. A beginner might start with 10-15 pounds. After four weeks of 2-3 sessions per week, they could progress to 20-25 pounds. Someone training seriously might ruck with 50+ pounds, building the kind of posterior chain strength usually reserved for deadlift specialists.

The Specific Benefits (With Numbers)

Research shows rucking delivers measurable results. A study comparing rucking to regular walking found that ruck-walkers increased calorie expenditure by 23-30% with the same time investment. More interesting: they built grip strength, shoulder stability, and core endurance without touching weights.

The lower body responds differently too. Your glutes and hamstrings engage harder. Your quads build resilience. Most people doing rucking report measurable improvements in lower body strength within 6-8 weeks, sometimes matching what they'd get from 2-3 gym sessions per week. For someone whose knees can't handle running, rucking provides the intensity and strength stimulus they can't get from casual walking.

Cardiovascular adaptations happen fast. Heart rate elevation during rucking sits in that zone 3 threshold training range that's become fashionable in endurance circles. You're building aerobic capacity without the pounding that makes running problematic for some people.

The Setup: Pack, Weight Distribution, and Starting Right

You don't need anything fancy. A decent backpack costs $40-100. Load it with weight plates, dumbbells, sand, or even water bottles. Start light—genuinely start light. 10-15 pounds feels ridiculous at first, then you hit mile two and understand why we evolved to complain about heavy things.

Weight distribution matters more than total weight. Everything should sit as close to your spine as possible. A pack riding low on your hips puts strain on your lower back. A pack riding too high throws your center of gravity forward. The sweet spot is snug against your back, centered between shoulder blades, with straps tight enough that the pack doesn't shift.

Distance and pace matter less than consistency. Most rucking routines involve 45-90 minute walks at moderate pace (2.5-3.5 mph). That's slower than casual walking for many people, which feels weird at first. Then you realize you're carrying extra weight, and suddenly 3 mph feels like real effort. Breathe through your nose when possible. Keep your posture upright—don't let the weight collapse you forward.

Common Mistakes That Derail Ruck Walkers

Progression too fast is the main culprit. Someone tries 30 pounds on day one, hates it, quits. Or they ruck every day, get burned out, and never touch the pack again. Rucking should be 2-4 times per week maximum. Your joints and connective tissue need recovery days.

Second mistake: bad form due to fatigue. As you get tired, you slouch. The pack pulls you forward. Your lower back compensates. That's not building strength—that's accumulating injury risk. Better to ruck 3 miles at good form than 5 miles falling apart.

Third: treating rucking like a race. This isn't speed work. Slow is the point. You're building durability and work capacity. Keep your pace conversational. If you can't talk, you're probably going too fast for a ruck.

2. Japanese Walking (Kintsugi Walking): The Mindful Movement Revolution

The Philosophy Behind Japanese Walking

Japanese walking, sometimes called "kintsugi walking" or the Japanese walking method, emerged from a completely different framework than Western fitness. It's rooted in concepts like ma (negative space), mushin (no-mind flow), and the idea that how you move matters as much as how far.

The core principle: walking is meditation in motion. You're not trying to optimize heart rate or burn calories—though both happen. You're integrating breath, posture, and presence into a single practice. The Japanese walking community emphasizes what they call "proper walking form" that prioritizes spinal alignment, shoulder relaxation, and rhythmic breathing.

Where Western walking programs ask "how far can you go," Japanese walking asks "how fully can you be present in this moment." It sounds philosophical until you realize that cortisol reduction and sympathetic nervous system regulation—the actual science of stress relief—happen through exactly this kind of intentional movement.

The Mechanics: Posture, Breathing, and Cadence

Japanese walking has specific mechanical principles that feel different the moment you start practicing them. Posture comes first. Your ears align over shoulders, shoulders over hips, hips over ankles. No slouching, no forward lean. This sounds easy until you realize most people walk with their head jutting forward—a position that's become endemic from years of phone use and desk work.

Correcting this posture makes an immediate difference. Your core engages. Your breathing opens up. Your shoulders drop from your ears. Within a week of conscious posture walking, people report less neck tension and fewer headaches. It's not mystical—better posture literally opens your airway and reduces muscle tension.

Breathing follows a specific pattern in Japanese walking. The rhythm coordinates with your steps. A common approach: breathe in for 3 steps, exhale for 3 steps. This creates a meditative cadence and forces slower, more intentional breathing. Your parasympathetic nervous system (the one that handles rest and recovery) activates. Studies show this style of walking reduces anxiety markers by 25-35% in people who practice it consistently.

Cadence sits around 100-110 steps per minute—slightly slower than typical brisk walking but faster than leisurely pace. The sweet spot balances efficiency with sustainability. You could do this for hours without exhaustion.

The Stress Reduction Science

What makes Japanese walking genuinely different from regular walking is the nervous system effect. A person on their phone while power walking is still stressed—they're just accumulating steps. A person doing Japanese walking while completely present in the movement triggers a genuine parasympathetic response.

Research from Japanese universities studying this approach found that practitioners experienced 25-35% reduction in cortisol levels over 8 weeks of consistent practice. More interesting: the effect was as pronounced as meditation in some measures, without requiring people to sit still.

Your heart rate variability—that marker of parasympathetic tone—improves. Your sleep quality improves. Your immune function improves (high cortisol suppresses immunity). None of this is as explosive as a HIIT workout, but sustained over months, the cumulative effect on health is enormous.

Integrating Japanese Walking Into Modern Life

The hardest part isn't the practice—it's finding 30-45 minutes where you're willing to be completely present without a phone. That's the real barrier. If you can solve for that, the practice itself is simple.

Many people start with short walks: 15 minutes from home around the neighborhood, eyes forward, phone in pocket. You notice details you've never seen before. Trees. The angle of light. Sounds. Sensations. It's not about going anywhere—it's about experiencing the journey.

Progression means increasing duration, not intensity. A sustainable practice might look like three 30-minute Japanese walks per week, plus regular movement the other days. Some people integrate it with commuting—walking to work or transit with full presence becomes the practice.

The real integration moment comes when you realize regular walking now feels off. You notice tension you didn't feel before, poor posture you didn't see before. The practice rewires your baseline. You start wanting good posture and intentional breathing because your nervous system has experienced the alternative.

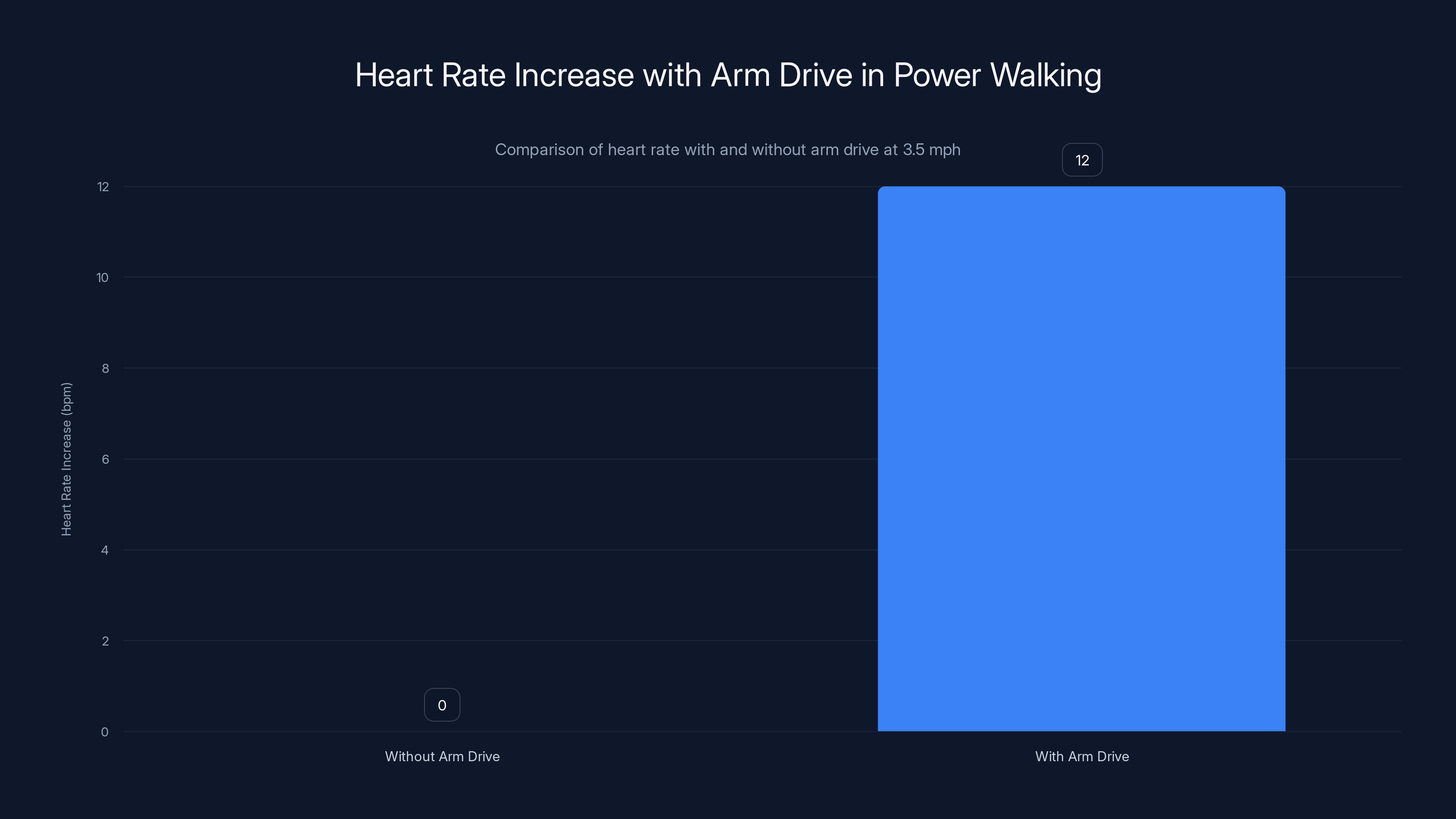

Adding intentional arm drive to power walking at 3.5 mph can increase heart rate by approximately 10-15 bpm, enhancing cardiovascular stimulus without increasing leg speed. Estimated data.

3. Tempo Walking: Building Aerobic Capacity Without Running

Why Tempo Walking Changes Your Cardiovascular Game

Tempo walking sits in this fascinating zone between leisurely walking and jogging. You're walking faster than comfortable pace but not so fast that you're gasping. Most people can sustain tempo walking at 3.5-4.0 mph—faster than typical 2.5 mph strolls but slower than jogging at 5+ mph.

The cardiovascular stimulus is real. Your heart rate climbs into that zone 3 range (70-80% max heart rate) that modern fitness science considers crucial for aerobic development. You're building the aerobic base that everything else stands on. Runners do tempo running for this reason. Cyclists do tempo efforts. Walkers finally have their equivalent.

What makes this brilliant for people who can't or won't run: you get similar cardiovascular adaptations with a fraction of the impact. Your knees, ankles, and hips experience zero pounding. Studies comparing tempo walking to jogging found nearly identical improvements in VO2 max over 8-12 weeks, assuming similar total volume and consistency.

The Progression Scheme That Actually Works

You can't start at 4.0 mph if you've been doing 2.5 mph. Your body needs a progression protocol. Here's what works: build to comfortable brisk walking first (3.0-3.2 mph for 30-40 minutes), then add one 20-minute tempo session per week at 3.5+ mph.

Week one: one session at 3.5 mph feels hard. Your legs feel heavy. Your breathing feels labored. This is fine—adaptation is happening. Week two: it feels noticeably easier. Week three: 3.5 mph feels almost casual, and you can sustain it for 25+ minutes. Week four: progress to 3.7 mph.

Over 12 weeks, most people progress from 3.2 mph comfortable pace to 4.0+ mph tempo pace. Your aerobic engine gets tangibly stronger. Your resting heart rate drops. Activities that used to feel hard (climbing stairs, catching up with friends) feel easy.

The secret is consistency. One session per week isn't enough. Two sessions per week is minimum for meaningful adaptation. Three sessions per week (at different efforts) is optimal for most people. But it has to be sustainable or the whole thing collapses.

Tempo Walking Variations: Add Specificity

Basic tempo walking: steady effort for 20-30 minutes. That's the foundation. From there, variations add specificity.

Fartlek walking (Swedish for "speed play"): walk at comfortable pace for 5 minutes, then surge to 3.8+ mph for 2 minutes, recover back to comfortable pace for 3 minutes, repeat. The unstructured intervals trigger adaptation differently than steady effort.

Threshold walking: find the exact pace where you transition into discomfort (usually 3.8-4.0+ mph). Sustain that edge for 15-20 minutes. Feels harder than steady tempo but builds more resilience.

Hill tempo walking: same effort level as flat tempo but on inclines. Your leg muscles recruit harder, your glutes engage more, and the cardiovascular demand increases without needing to go faster.

Most structured plans use one steady tempo session, one interval-based session, and one conversational pace session per week. The variation prevents adaptation plateau and keeps it interesting.

4. Hiking: Incline Walking That Builds Lower Body Power

Why Hiking Isn't Just Walking With Better Views

Hiking is walking with elevation change, and elevation change changes everything. Your body becomes a completely different machine on inclines. Glute activation increases by 40% compared to flat walking. Quadriceps engagement intensifies. Your core stabilizes harder as the terrain becomes uneven.

This is why people who hike regularly develop serious leg strength without ever stepping foot in a gym. A steep incline walk for 60 minutes hits leg muscles harder than an hour on a stair climber, and it feels less monotonous because you're actually going places.

The cardiovascular demand escalates dramatically. Walking at 2.5 mph on flat ground is casual. Walking at 2.5 mph uphill feels genuinely difficult. Your heart rate climbs 20-30 bpm higher for the same speed. Your body burns more calories per minute on inclines—sometimes 2-3x more depending on gradient.

There's also something about hiking that makes the fitness effect invisible. You're not "working out"—you're hiking, which feels like an adventure. You cover miles before realizing how hard you've been working. The next day, your quads and glutes are pleasantly sore. Over weeks, your legs develop visible strength and definition.

Terrain Types and Their Training Effects

Rocky, uneven terrain: forces constant micro-adjustments from stabilizer muscles in your ankles and feet. This improves proprioception (your sense of where your body is in space) and builds foot strength. You'll notice improved ankle stability after weeks of this.

Steep grades (8%+ incline): pure leg power building. Every step requires significant glute and quad activation. Short steep hikes are efficient but exhausting. A 45-minute hike with significant elevation gain can match the leg stimulus of a 60-minute weight room session.

Technical terrain (roots, rocks, water crossings): engages your whole system. Your core stabilizes constantly. Your legs react dynamically. Your upper body helps with balance. This is functional fitness in its rawest form.

Long, steady inclines: builds muscular endurance. You learn how to pace yourself on sustained effort. Your aerobic system develops significantly. Most people feel the cardiovascular demand here as much as the leg demand.

The Progressive Hiking Path

Start with easy terrain, 30-45 minutes, moderate pace. You're building hiking fitness, which includes balance, foot strength, and coordination—not just leg power.

Week 2-3: increase duration to 45-60 minutes on similar terrain. You're building engine capacity.

Week 4-6: introduce terrain variations—some rocky sections, some steeper pitches. You're building resilience and adaptability.

Week 7-12: longer hikes (90+ minutes) or longer climbs. Vertical elevation gain becomes the marker—track how much elevation you're ascending per week.

Most structured hikers aim for 1,000-1,500 feet of elevation gain per week spread across 2-3 hikes. That's roughly equivalent to a 90-minute hike with moderate climbing, or a 2-hour hike with significant climbing.

Avoiding Common Hiking Injuries

Knee pain on descents is the most common complaint. Your quads and knee joint absorb all the impact on downhill sections. Prevention: slow your descent to half your ascent pace, focus on controlled braking with your quads, and consider poles for knee unloading.

Blister development comes from friction and moisture. Proper hiking boots (broken in before the hike), merino wool socks, and frequent breaks to adjust fit prevent 95% of blister problems. It's not about toughness—it's about smart preparation.

Ankle rolling happens on technical terrain when you're tired. Slow down as you tire, watch your foot placement carefully, and consider ankle-strengthening exercises in your non-hiking days. Weak ankles are a training gap, not a personal flaw.

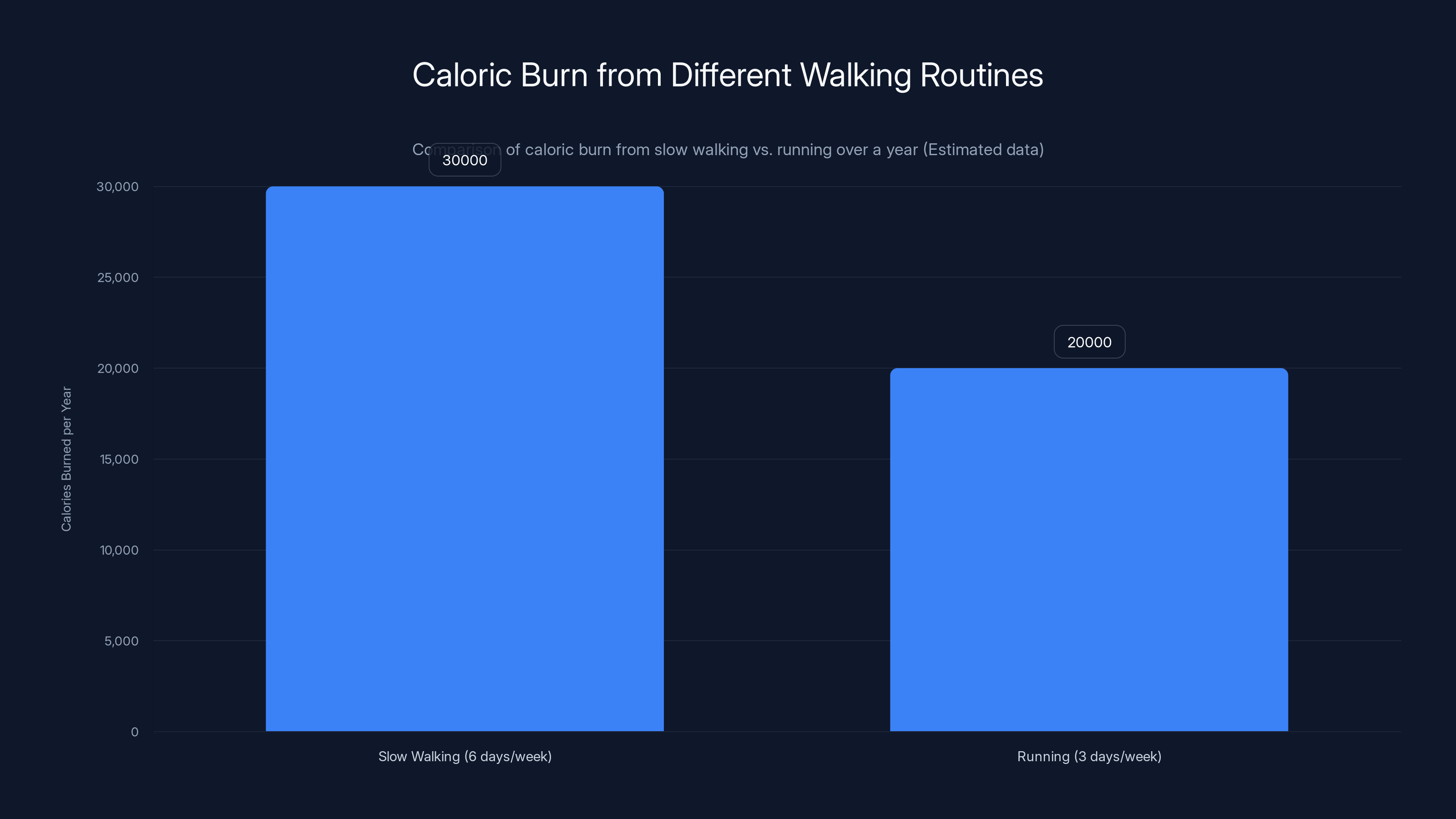

Slow walking at 2.5 mph for 45 minutes, six days a week, can burn approximately 30,000 calories annually, surpassing the caloric burn from running three times a week. Estimated data.

5. Slow Walking: Underrated Consistency Builder

The Case for Deliberately Slow

Slow walking sounds boring. It sounds like something you do while grocery shopping, not something that "counts" as fitness. But here's the counterintuitive reality: slow, consistent walking is one of the most effective fitness interventions ever studied.

Research on longevity shows that people who walk consistently at any pace—even slow pace—live significantly longer than sedentary people. Significantly longer. Like 3-7 years longer depending on studies. More interesting: the pace difference between 2 mph walking and 4 mph walking matters less than most people think. The huge gap is between sedentary and any regular walking.

This changes the game for sustainability. You don't need intensity. You don't need to gasping. You need consistency: same time every day or most days, any speed that works for you.

Slow walking is also the glue that holds everything else together. If you're doing tempo walks, strength training, and rucking, you need recovery days. Slow walking fills those days perfectly. You're moving, your cardiovascular system is working, but you're not creating additional fatigue. Your body recovers from hard efforts while staying in motion.

The Metabolic Magic of Frequent Movement

Here's where slow walking gets interesting from a metabolic standpoint. A person who walks 45 minutes every single day at 2.5 mph burns more fat over a year than someone who runs 3 times per week. Why? Frequency beats intensity for fat metabolism in ways people misunderstand.

Your body has multiple fuel sources. Intensity preferentially burns carbohydrate. Lower intensity, longer duration preferentially burns fat. A slow 45-minute walk can burn 150-180 calories, of which 60-70% comes from fat metabolism. Do that six days per week, and you're burning 600+ calories per week from fat oxidation. That's 30,000 calories per year from a walking routine that barely feels like exercise.

This is especially powerful for people managing metabolic health. Diabetics, pre-diabetics, and people with metabolic syndrome show massive improvements in blood sugar regulation, insulin sensitivity, and lipid profiles from consistent slow walking. It's boring, but it works.

Building the Slowest Pace That Works

Slow walking, as a training approach, is typically 1.5-2.5 mph—slow enough that you can talk comfortably, sometimes too slow for older adults who prefer faster paces. The actual speed matters less than the fact that it's sustainable and doable every day.

Most people do better with 30-45 minutes of slow walking daily than 60 minutes three times per week. The frequency wins. Your muscles stay in motion, your metabolism stays elevated (though low), and your mind gets the meditation benefit of regular gentle movement.

Progression for slow walking looks different. Instead of going faster, you're going longer and more frequently. Week 1: 30 minutes, 5 days per week. Week 3: 45 minutes, 5 days per week. Week 6: 60 minutes, 5-6 days per week. Some people eventually walk 60-90 minutes per day at slow pace—genuinely enjoyable because it's meditative and social.

You can walk with podcasts, audiobooks, friends, or complete silence. The routine becomes habitual. Most people who build slow walking habits report that not walking feels strange—missing the movement creates an almost anxious sensation. That's your nervous system recognizing a positive stimulus you're not providing.

6. Incline Treadmill Walking: Structured Indoor Training

Why Incline Treadmills Aren't Cheating

Incline treadmill walking gets dismissed sometimes—like it's somehow less legitimate than outdoor hiking. Nonsense. From a muscular standpoint, an incline treadmill creates the same stimulus. From a convenience standpoint, it's infinitely better for people with limited time, bad weather, or darkness concerns.

Walking at 3.0 mph with 6-8% incline activates glutes and legs almost as powerfully as a steep outdoor hike, with zero technical footwork required. Your body's adaptation will be similar. You build leg strength, cardiovascular capacity, and muscular endurance without the unpredictability of trail conditions.

The advantage: you control every variable. Incline, speed, duration—all precise. This is perfect for structured progression. Week one: 3.0 mph, 6% incline, 30 minutes. Week three: 3.2 mph, 8% incline, 35 minutes. By week 12, you're walking 3.5+ mph at 8-10% incline for 45 minutes straight. That's serious physical development.

The Protocol That Works

Steady-state incline walking: pick your incline (6-8% is solid for most people) and speed (3.0-3.5 mph), walk for 30-60 minutes. Heart rate climbs into zone 3-4. You're building aerobic and muscular endurance simultaneously.

Incline intervals: alternate between moderate incline for 2 minutes and high incline for 1 minute, repeat for 30-40 minutes. The harder segments push your cardiovascular system. The recovery segments let you sustain total duration. This approach builds power and efficiency.

Pyramid inclines: start at 4% incline for 3 minutes, increase 2% every 3 minutes until you reach 12%, then decrease back down. You're hitting different muscular demand levels within one session. Your legs experience the full range of climbing stimulus.

Decline walking (only if your treadmill allows): lower incline to negative (downward) and walk. This emphasizes quad and shin engagement as you're actively braking the treadmill. Quadriceps activation increases 30-40% on decline compared to flat walking. This is useful for quad-specific strength building but harder on knees—use sparingly.

Avoiding Treadmill Boredom

The main challenge with incline treadmill training: monotony. Your mind isn't engaged with scenery. Your feet aren't navigating terrain. It's pure grinding.

Solutions: podcasts or audiobooks (the good kind where you lose track of time), walking while watching training videos or educational content, varying your program weekly to keep stimulus different, or walking with others (treadmill side-by-side with a friend).

Some people use incline treadmill time as their meditation time—headphones off, completely focused on the movement. Others find this unbearable. Know yourself and set up your environment accordingly. If boredom makes you quit, you've lost.

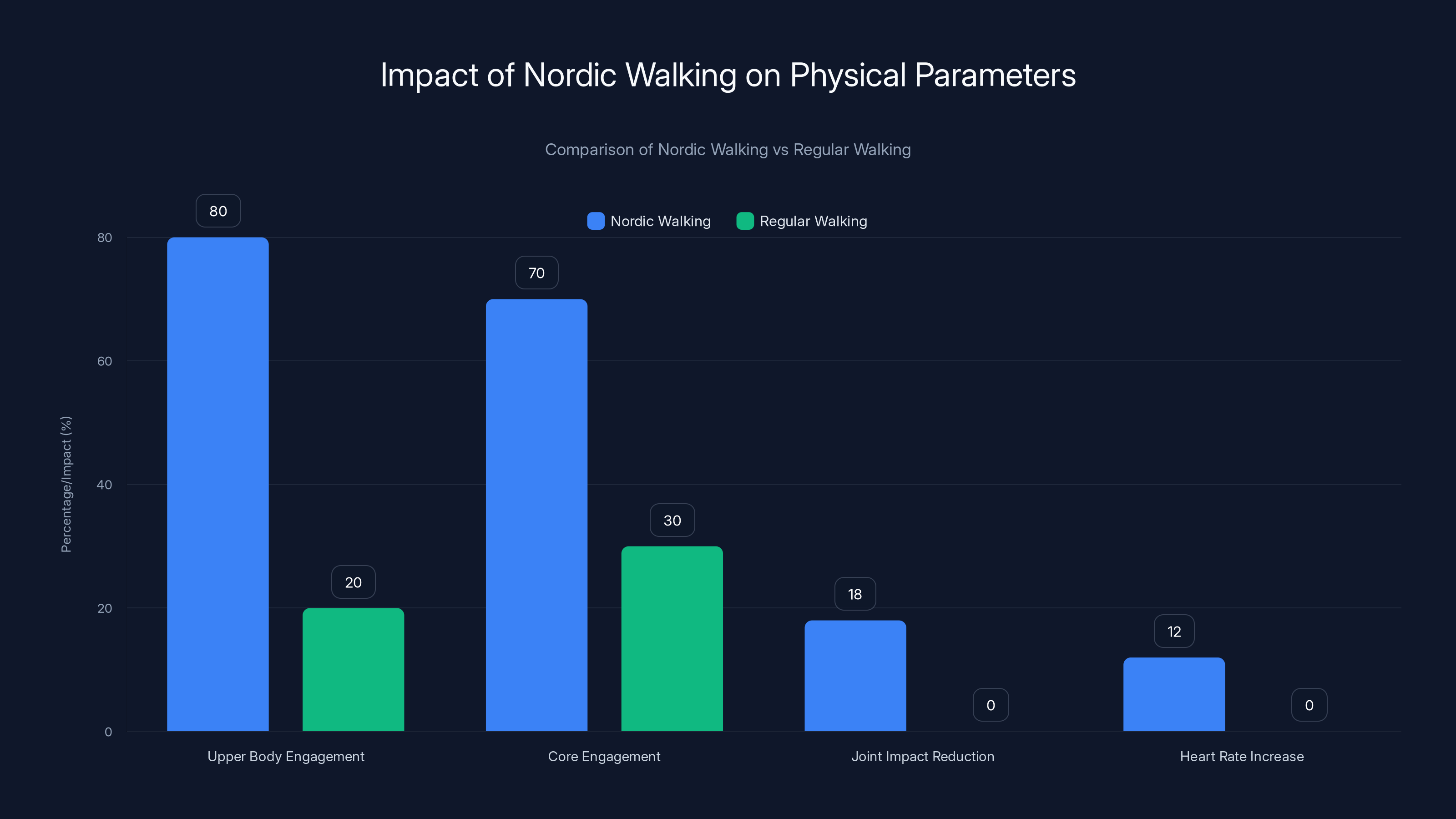

Nordic walking significantly increases upper body and core engagement while reducing joint impact by 15-20% and increasing heart rate by 10-15% compared to regular walking. Estimated data based on typical findings.

7. Power Walking: The Speed-Focused Approach

Defining Power Walking vs. Jogging vs. Everything Between

Power walking sits in a specific intensity zone: 3.5-4.5 mph walking speed with intentional arm movement and postural engagement. It's faster than tempo walking but you're still walking (one foot always in contact with ground, technically). The moment both feet leave the ground simultaneously, you've crossed into jogging.

For some people (especially heavier individuals, older adults, or anyone with knee issues), power walking provides cardiovascular stimulus they can't safely get from running. Heart rate reaches 65-75% max during power walking, which is the sweet spot for aerobic development. You're building fitness, just via a different modality.

What makes power walking different from just "walking fast": intention. You're not casually strolling at 4 mph. You're engaging your core, pumping your arms, maintaining strong posture, and holding steady effort. It's active, not passive.

The Arm Drive Component

This is what separates power walking from just walking at faster speeds. Your arms aren't swinging casually. They're driving: elbow bent at 90 degrees, swinging from shoulder with purpose, hands brushing past hip. This arm drive does several things.

First: it increases heart rate and oxygen demand without increasing leg speed. You can walk 3.5 mph casually, then add intentional arm drive and watch your heart rate climb 10-15 bpm. Same speed, higher stimulus.

Second: it engages your core and shoulders more than leisurely walking. You're using your upper body. This distributes fatigue across more muscles and prevents the localized leg fatigue that can limit duration.

Third: it improves gait efficiency over time. Learning to use your arms and core properly takes load off your knees and lower legs. You can sustain effort longer and feel fresher the next day.

Power Walking Programming

Steady power walks: 30-45 minutes at 3.8-4.2 mph with full arm drive. Effort feels moderate-to-hard. You can speak short sentences but not full conversations. Heart rate is elevated throughout. This is your aerobic threshold work.

Power walk intervals: 5-minute warm-up at easy pace, then alternate 3 minutes at 4.0+ mph with 2 minutes at moderate pace, repeat 4-5 times, cool down 5 minutes. The harder intervals build capacity. The recovery intervals let you sustain total duration.

Pyramid power walking: start at 3.5 mph, increase 0.2 mph every 2 minutes until you hit 4.3 mph, hold for 5 minutes, then decrease back down. You're hitting multiple intensity zones within one session.

Progression looks like: maintain 3.8 mph for 30 minutes comfortably → increase to 4.0 mph for 30 minutes → increase duration to 45 minutes at 4.0 mph → increase to 4.2 mph and sustain. Each progression takes 2-3 weeks of consistent training.

8. Nordic Walking: Poles Change Everything

Why Poles Aren't Just for Ski Slopes

Nordic walking originated as a cross-training method for skiers in the off-season. Skiers wanted to maintain fitness and power during summer. Walking alone didn't provide enough resistance. Adding poles completely changed the stimulus.

With poles: you engage your upper body, core, and back muscles in ways that flat walking never activates. Your arms and shoulders do real work. Your core stabilizes against pole push-off. The poles reduce impact on your lower joints by 15-20% because some of your body weight transfers to the poles.

This creates a fascinating paradox: by adding equipment, you reduce joint impact while increasing total muscle engagement. A person with knee pain who can't handle regular walking often handles Nordic walking beautifully because the upper body engagement transfers load away from problematic knees.

Cardiovascular stimulus increases dramatically. Studies show heart rate is 10-15% higher during Nordic walking versus regular walking at the same speed, making it more aerobically demanding.

The Technical Skill Component

Nordic walking isn't just "walk while holding poles." There's actual technique: your poles should touch ground just before your opposite-side foot lands (right pole touches as left foot strikes). Your arms drive forward and back. You're not pushing sideways or dragging poles—you're using them as propulsion.

When done correctly, Nordic walking has a particular rhythm and flow. Your posture improves naturally (poles encourage upright carriage). Your walking pattern becomes more efficient. The technique takes 15-30 minutes to learn and a few weeks to feel natural, but once ingrained, it becomes automatic.

Who Benefits Most

Older adults: poles provide balance assistance and reduce joint impact simultaneously. Fall risk decreases. Walking confidence increases. People in their 60s, 70s, and 80s often report that Nordic walking let them walk longer and with less joint pain than they could without poles.

Heavier individuals: same joint impact reduction. The poles help redistribute load. Someone carrying extra weight finds Nordic walking more sustainable than regular walking.

Athletes in off-season: perfect for maintenance training that's less jarring than running.

Anyone with lower body limitations: knee pain, hip issues, ankle problems—all respond well to the load redistribution that poles provide.

Rucking burns the most calories per session, followed by incline hiking, making them effective for weight loss if done consistently. Estimated data.

The Technology Layer: Apps and Wearables That Optimize Walking

What Data Actually Matters

Modern fitness trackers measure step count, heart rate, elevation gain, route mapping, and pace. All useful. But what actually drives results?

Consistency tracking matters most. If an app makes walking a habit and builds motivation, it's worth using. Streaks, calendar views, weekly summaries—these aren't just vanity metrics. They're behavioral reinforcement. Missing a day feels like breaking a chain. Hitting your target feels like a win.

Heart rate variability is the most sophisticated metric available on good devices. It tells you about your nervous system health and recovery status. Training hard on days when HRV is low (indicating you haven't recovered) is counterproductive. Training easy on those days protects you.

VO2 max estimates from wearables are surprisingly accurate. Watching this number climb over weeks of consistent training is genuinely motivating. You're building actual fitness, and the number proves it.

Metrics that don't matter much: daily step count (steps to 10,000 is arbitrary), calorie burn estimates (extremely inaccurate), and most "active minutes" calculations.

Apps for Structured Programs

If you want to follow specific protocols (like the progression schemes mentioned above), dedicated walking apps guide you through daily workouts. Audio coaching, curated routes, progress tracking, and community features keep you accountable.

For people who prefer to DIY, a basic notes app and timer work fine. Track your distance, time, pace, and how you felt. The minimum viable tracking system is sometimes the most sustainable.

Combining Walking Approaches: The Weekly Schedule That Works

The Foundation Framework

Most effective walking programs mix multiple styles, not because variety is needed for muscle confusion (that's a myth), but because different walks serve different purposes and you need frequency.

Example weekly structure for someone wanting serious results:

- Monday: tempo walk or power walk (20-30 minutes at moderate-hard effort)

- Tuesday: rucking or incline hiking (30-45 minutes with load or elevation)

- Wednesday: slow walk or Japanese walk (30-45 minutes, low intensity, focus on form)

- Thursday: tempo or power walk (20-30 minutes at moderate-hard effort)

- Friday: off or gentle slow walk

- Saturday: long hike or long slow walk (60-90 minutes, fun-focused)

- Sunday: easy recovery walk or off (10-20 minutes if moving helps soreness)

This structure provides 2-3 harder sessions, 1-2 moderate sessions, and 1-2 easy sessions per week—the classic periodization pattern that works for any fitness modality.

Progression Across 12 Weeks

Weeks 1-3: establish consistency. Make sure you're actually doing the walks scheduled. Form matters more than speed or distance. Walking should feel sustainable.

Weeks 4-6: introduce progression. Increase difficulty on hard days (faster speed, more weight, longer distance). Maintain easy days. You'll notice adaptation—things that felt hard now feel normal.

Weeks 7-9: push progression further. Hard days get harder (higher speed, more weight, longer distance). Easy days stay easy. You're building a real aerobic base and leg strength.

Weeks 10-12: maintain and assess. You're not necessarily pushing harder, just maintaining the stimulus you've built. Assess how far you've come. Most people notice major changes: legs look different, resting heart rate is lower, energy is higher.

After 12 weeks, you can either continue with the current program (consistency matters more than novelty) or introduce new stimulus (start incorporating tempo intervals differently, add different hiking routes, try poles if you haven't).

Common Walking Mistakes That Limit Results

Progression Too Fast

Someone walks casually for years, then decides to get serious. They start rucking with 30 pounds, push 5 miles per week at high intensity, and add tempo efforts. Three weeks later, they're injured or burned out.

Your body adapts to stress gradually. Adding 10% more volume per week is considered safe. That means if you're walking 5 miles per week, next week is 5.5 miles. Week after is 6 miles. This seems slow. It's not. Over 12 weeks, you've more than doubled volume while avoiding injury.

Ignoring Recovery

Harder walks stress your body. Recovery walks repair it. If you're doing hard efforts 5 days per week, you're accumulating fatigue instead of building fitness. Two hard sessions and three easy sessions per week is optimal for most people. The easy sessions matter as much as the hard ones.

No Attention to Form

Fast walking with terrible posture is not walking. It's slouching quickly. Your back hurts. Your joints take more impact. You get injured or burned out.

Spend weeks getting form right before progressing intensity or duration. Good posture means ears over shoulders over hips. Core is engaged but not clenched. Breathing is coordinated with steps. Once this is automatic, you can add effort on top of good foundations.

Skipping Variety

Doing the same walk at the same pace, same distance, same time every single time creates a plateau. Your body adapts. Stimulus plateaus. Results stall.

Variety doesn't mean completely different walks every day. It means tempo walks sometimes, power walks sometimes, long slow walks sometimes, hikes sometimes. Different walking styles stress different energy systems and muscle groups. This prevents plateaus.

Not Tracking Anything

You can't manage what you don't measure. If you're not tracking distance, time, pace, or how you felt, you have no data about progress. You can't verify if you're actually progressing or just going through motions.

Minimal tracking looks like: date, distance, time, perceived effort (easy/moderate/hard). From this, you can see patterns and trends. You know if you're actually progressing or stalling.

FAQ

What is the best walking style for weight loss?

Rucking combined with tempo walking creates the fastest weight loss results, but only if it's sustainable. A person who does 3 rucking sessions per week consistently beats someone who tries intense walking once per week and quits. Rucking burns 200-250 calories per 45-minute session versus 100-150 for regular walking, and the elevated post-exercise metabolic rate lasts longer. However, the best walking style for weight loss is the one you'll actually maintain for months. Consistency beats optimization every time.

How long does it take to see results from walking?

You'll feel better after 2-3 weeks—more energy, better sleep, improved mood. Visible fitness changes (stronger legs, better posture, improved endurance) appear after 4-6 weeks of consistent training. Significant body composition changes (visible fat loss, muscle definition) typically take 8-12 weeks depending on your starting point and how much weight you're carrying. Cardiovascular adaptations (lower resting heart rate, improved VO2 max) are measurable within 4-6 weeks with structured training.

Can walking replace gym training?

Walking can replace some gym training but not all. Walking builds cardiovascular fitness, lower body muscular endurance, and leg strength remarkably well. Rucking especially builds functional strength and posterior chain development. However, walking doesn't build upper body strength, pressing strength, or pulling strength effectively. An ideal program combines walking (3-5 sessions per week) with 1-2 resistance training sessions per week for balanced fitness. For pure cardiovascular health and weight management, walking alone is excellent and often better than sporadic intense exercise.

Which walking method burns the most calories?

Rucking burns the most calories per minute when including the weight load—approximately 200-250 calories per 45-minute session. Incline hiking is close behind depending on grade and speed. Tempo walking and power walking burn 150-200 calories per 45 minutes. Japanese walking and slow walking burn 100-150 calories per 45 minutes. However, burn rate is only one component of total fat loss. Sustainability matters more. Walking 45 minutes daily at low intensity often produces better fat loss results than rucking sporadically because the accumulated volume and metabolic adaptation are superior.

Is Nordic walking harder than regular walking?

Yes, Nordic walking is cardiovascularly harder—heart rate is 10-15% higher at the same speed. However, it feels easier on joints because the poles reduce impact on lower body by 15-20%. For someone with knee pain, Nordic walking often feels easier despite the higher cardiovascular demand because the load distribution improves comfort. For someone without joint issues, Nordic walking is a legitimate intensity increase that improves upper body and core engagement.

How do I prevent injuries while walking for fitness?

Prevention comes from gradual progression (adding no more than 10% volume per week), proper footwear (supportive shoes broken in before high mileage), form attention (posture and gait patterns matter), adequate recovery (not doing hard walks every day), and listening to your body (persistent aches aren't normal). Blister prevention requires proper socks (merino wool) and frequent breaks to adjust fit. Knee pain usually responds to slower descent speeds and deliberate quad engagement. Shin pain suggests you're progressing too fast or wearing unsupportive shoes. Most walking injuries prevent themselves through smart programming.

Should I do walking or running for fitness?

Walking is better for most people. Running builds slightly higher cardiovascular capacity but at significantly higher injury risk, higher joint impact, and lower sustainability for most people. Walking provides similar cardiovascular benefits with much lower injury risk when done consistently. Running is superior if you enjoy it and your body tolerates it well. Most people see better long-term results with consistent walking than sporadic running. If you can't decide, do both—walk 3-4 days per week and run 1-2 days per week for balanced stimulus and injury prevention.

The Walking Future: 2026 and Beyond

Why Walking Is The Fitness Trend That Won't Fade

Fitness trends usually die. They're flashy, unsustainable, and eventually exhausted. Walking won't. Why? Because it works, it's accessible, and it doesn't require buying into an ideology.

You don't need fancy gear (though rucking packs and poles are cheap). You don't need a gym membership. You don't need athletic genetics. You just need to show up and move. And the results—improved health markers, weight loss, better mood, stronger legs, improved cardiovascular fitness—are real and measurable.

The technology enablement (apps, wearables, online communities) removes the isolation. Walking alone used to be boring. Now you can follow structured programs, see global communities doing the same walk, get real-time feedback, and compete on leaderboards. For people who respond to that structure, it's transformative.

Building Your Walking Practice Now

Pick one walking style that resonates with you. Not the optimal one—the one you'll actually do. If that's Japanese walking and it brings you joy and peace, that's infinitely better than optimal rucking that you hate and quit after three weeks.

Commit for 12 weeks. Let your body adapt. Notice changes in energy, mood, leg strength, and fitness capacity. If you're enjoying it, progress the training. If something isn't working, adjust—try a different style or find a different routine that fits your life.

The best training program is the one you sustain. Walking doesn't require perfection. It requires consistency. It requires showing up, week after week, trusting that the adaptations are happening even if you can't see them yet.

Twelve weeks from now, you'll be shocked at how far you've progressed. That's when you understand why walking is the fitness comeback story of 2025. It was always there. You just needed permission to take it seriously.

Conclusion: Your Walking Journey Starts With One Step

Walking for fitness feels counterintuitive in a world obsessed with intensity, optimization, and spectacle. We've been sold the narrative that real fitness requires suffering, expensive equipment, and constant progression. Meanwhile, some of the healthiest, strongest people around walk consistently and don't care about the extremes.

The seven walking approaches in this article—rucking, Japanese walking, tempo walking, hiking, slow walking, incline treadmill walking, power walking, and Nordic walking—represent a spectrum of intensity, purpose, and lifestyle fit. None of them are objectively "best." Your best walking style is the intersection of what works for your body, what you'll actually do consistently, and what fits your current life situation.

Someone with joint issues might start with Japanese walking for nervous system benefits and Nordic walking for load reduction. Someone wanting rapid strength development might lean on rucking and hiking. Someone wanting pure consistency might build a slow walking habit that requires zero motivation. Someone wanting the most efficient stimulus might structure tempo and power walks strategically.

The exciting part isn't finding the perfect approach. It's discovering that walking—simple, accessible, ancient walking—can deliver fitness results that rival much more complex and demanding approaches. Your cardiovascular system doesn't care if you're doing a structured tempo walk or just walking fast with good posture. Your legs don't care if you're on a treadmill incline or a real mountain. Your nervous system doesn't care if you're following Japanese walking principles or just walking in fresh air with full presence.

What your body responds to is consistent stimulus. Show up. Walk. Pay attention. Gradually progress. Do it for 12 weeks. Notice the changes. Make it part of your life.

That's the whole system. It sounds too simple because it is. Simple is why it works where complexity fails. Start walking tomorrow—not someday, not next week. Pick your style. Pick your distance. Just move.

Your future self will thank you.

Key Takeaways

- Walking, when done intentionally with varied approaches, delivers cardiovascular and strength results comparable to more intense modalities

- Rucking (weighted walking) increases calorie burn by 23-30% and builds functional strength without heavy lifting

- Japanese walking reduces cortisol by 25-35% through postural alignment and mindful breathing coordination

- Tempo walking at 3.5-4.0 mph builds VO2 max almost as effectively as jogging with zero joint impact

- Hiking produces 40% greater glute activation than flat walking, building lower body power sustainably

- Consistency beats optimization—the best walking style is the one you'll maintain for 12+ weeks

- A balanced weekly program mixing hard sessions, moderate efforts, and easy recovery walks prevents plateaus

![7 Walking Styles for Fitness: Rucking to Japanese Walking [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/7-walking-styles-for-fitness-rucking-to-japanese-walking-202/image-1-1767704979049.jpg)