A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms: How HBO Finally Got Game of Thrones Right

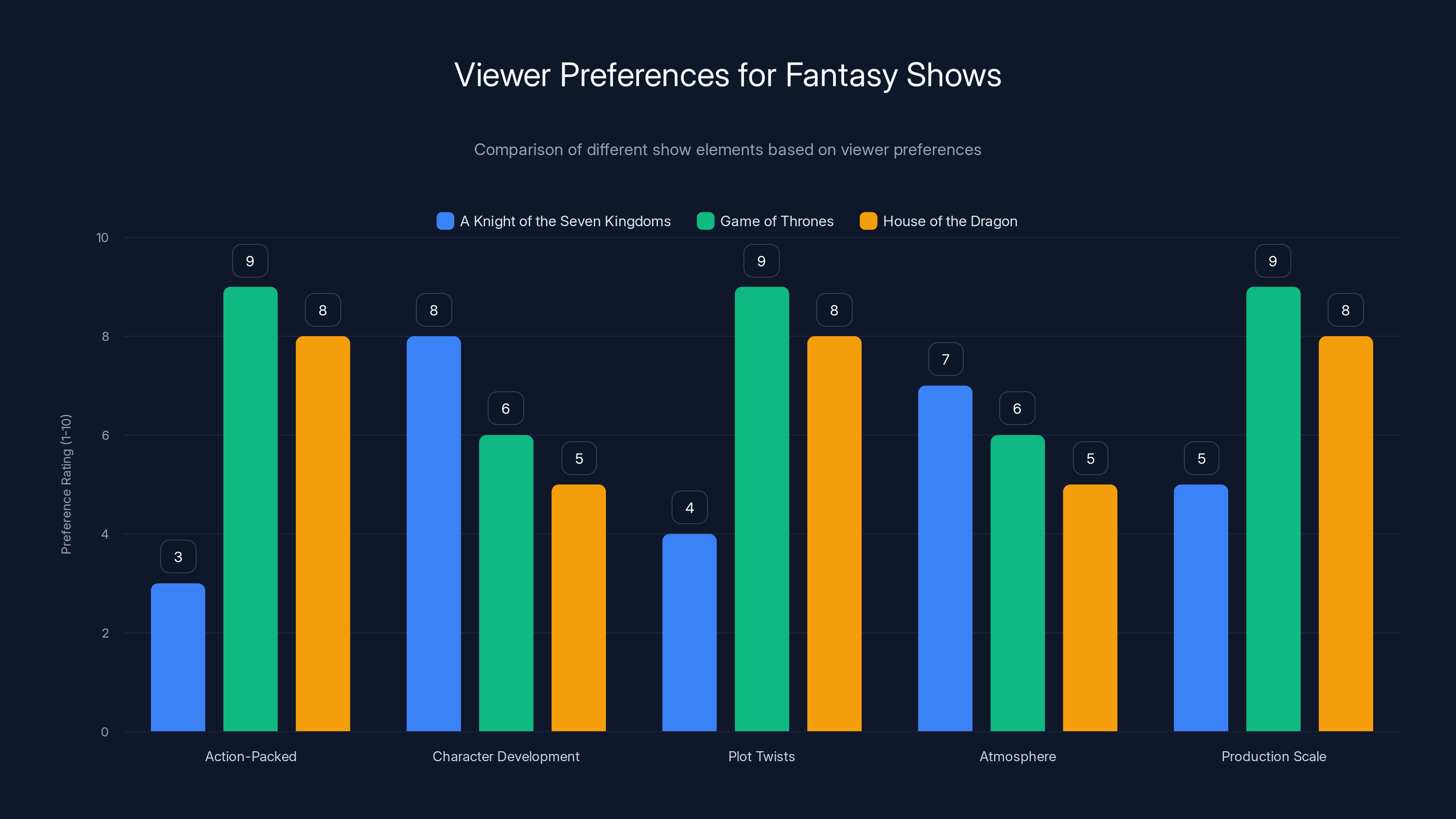

Here's the thing about Game of Thrones prequels. After House of the Dragon landed with all the subtlety of a dragon dropping fire on King's Landing, you'd think HBO would've learned something about what actually makes this world interesting. The network already proved it could spend massive budgets on Westeros. But spending money and telling a good story? Those are different problems entirely.

Then HBO releases A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms, and suddenly the franchise remembers how to breathe.

This isn't your typical Game of Thrones experience. It's shorter, smaller, and—most surprisingly—it actually has a sense of humor. Six episodes instead of ten. A focus on the smallfolk instead of the nobility. Two characters who give a damn about honor instead of power. It's so refreshingly different that you almost forget it exists in the same universe as all that political backstabbing and dragon violence.

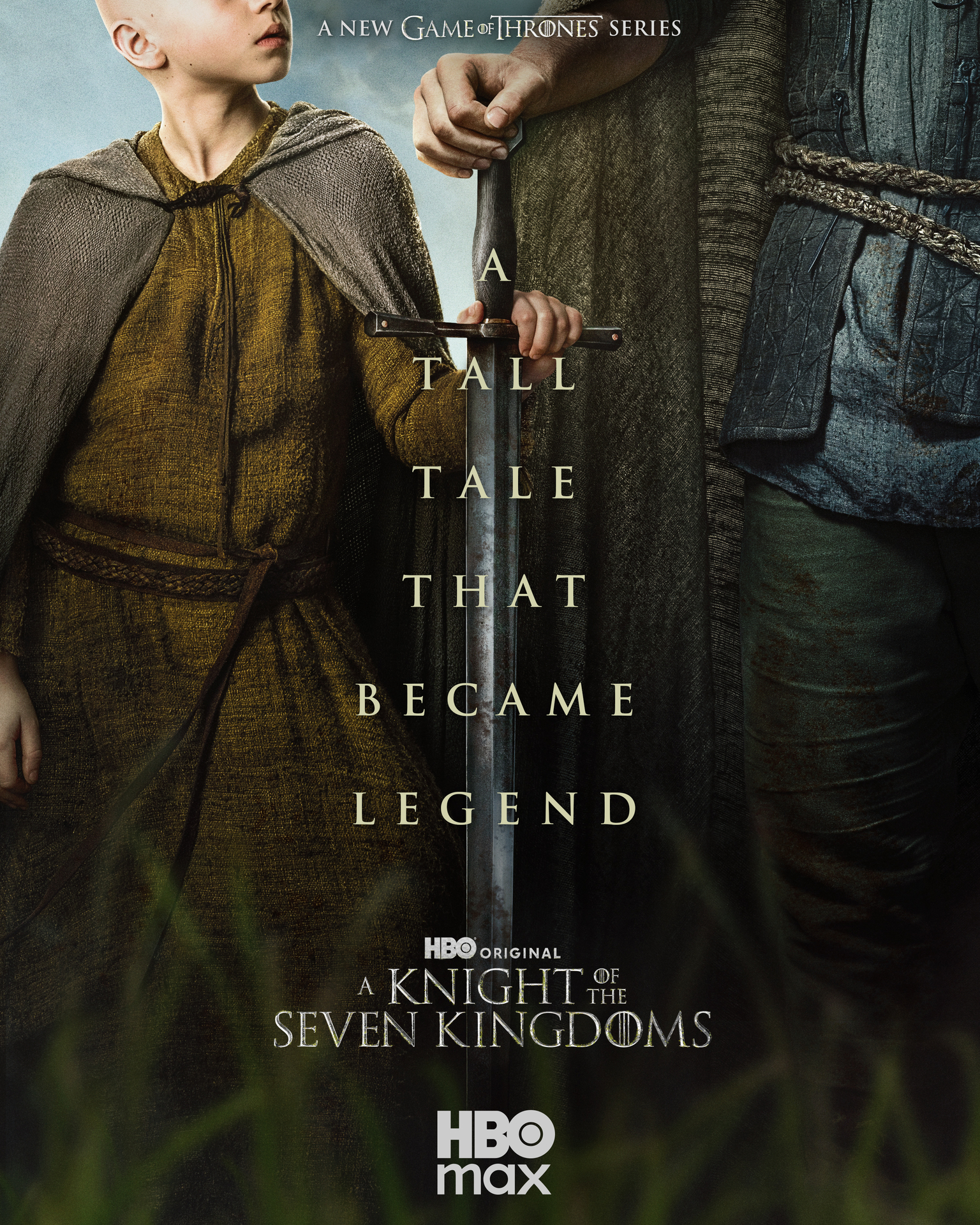

Based on George R. R. Martin's Tales of Dunk and Egg novellas—material that's been floating around since 1998—this series takes a century-old story and makes it feel urgent, funny, and weirdly hopeful. That last part alone makes it stand out. Game of Thrones wasn't hopeful. House of the Dragon certainly isn't hopeful. But A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms? It dares to suggest that ordinary people with decent intentions might actually matter.

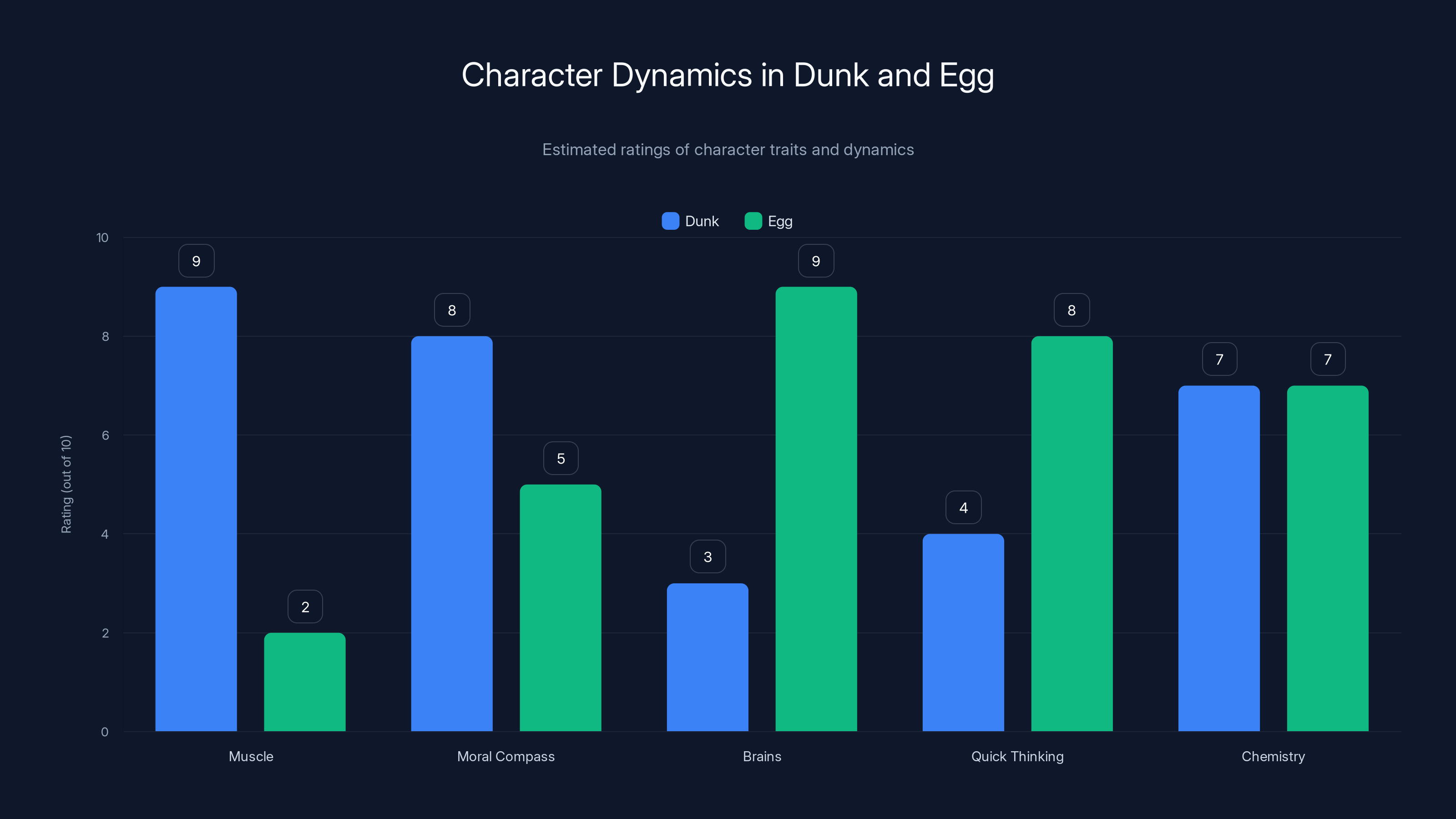

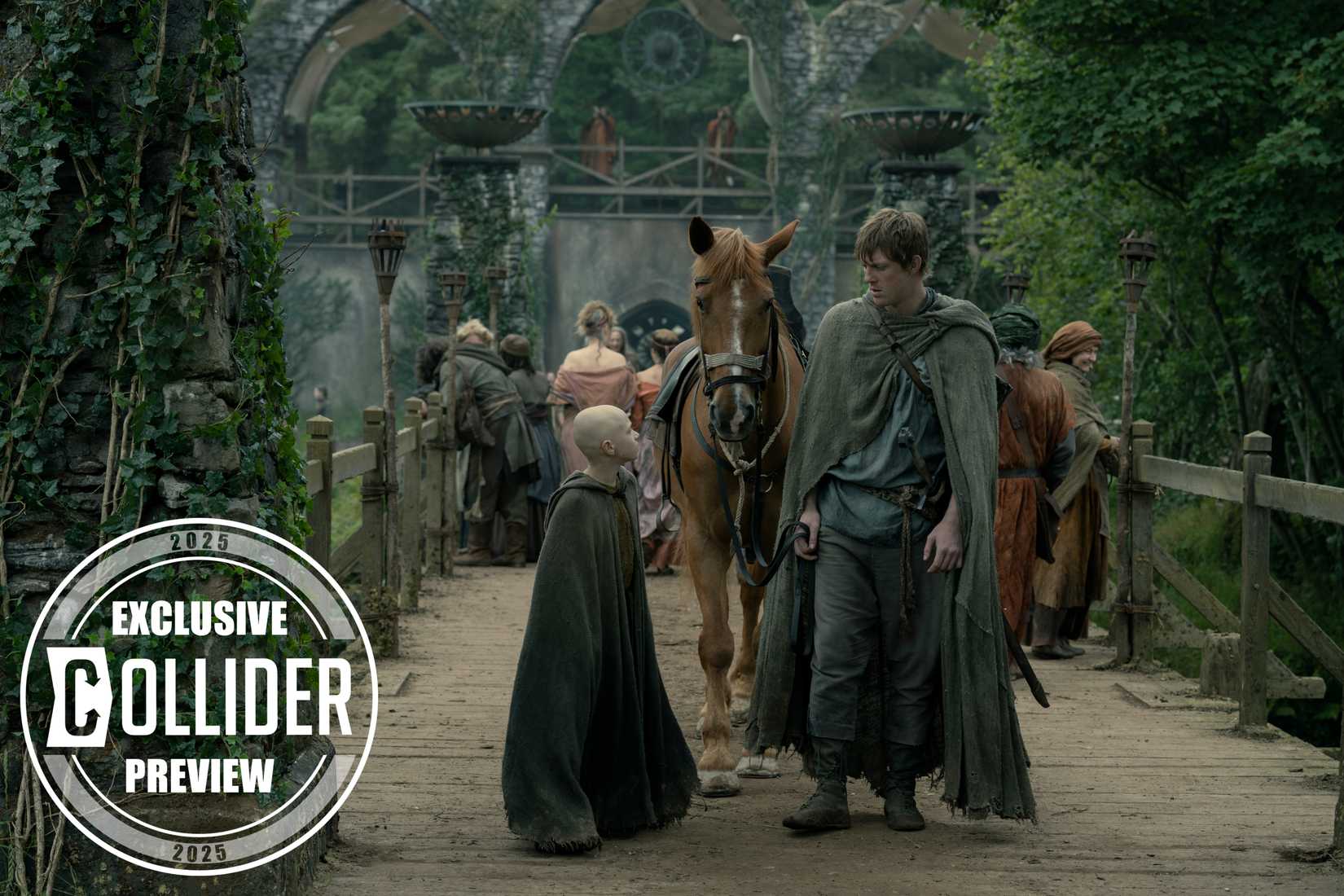

The genius is in the simplicity. The story follows Ser Duncan "Dunk" the Tall, a hedge knight with more muscle than sense, and his young companion Egg, a precocious kid with mischief in his DNA and secrets in his background. They're traveling through Westeros with no lands, no titles, and no realistic chance of making it. But Dunk believes in something most people in this world abandoned long ago: that honor means something.

That belief becomes the emotional core of the entire series. And it works because the show doesn't treat it like a joke. It takes Dunk seriously while also letting him be funny—accidentally, unintentionally, charmingly funny. He's a huge guy who trips over his own feet. He mispronounces things. He gets confused easily. But he's never stupid, and he's never treated as a punchline by the narrative.

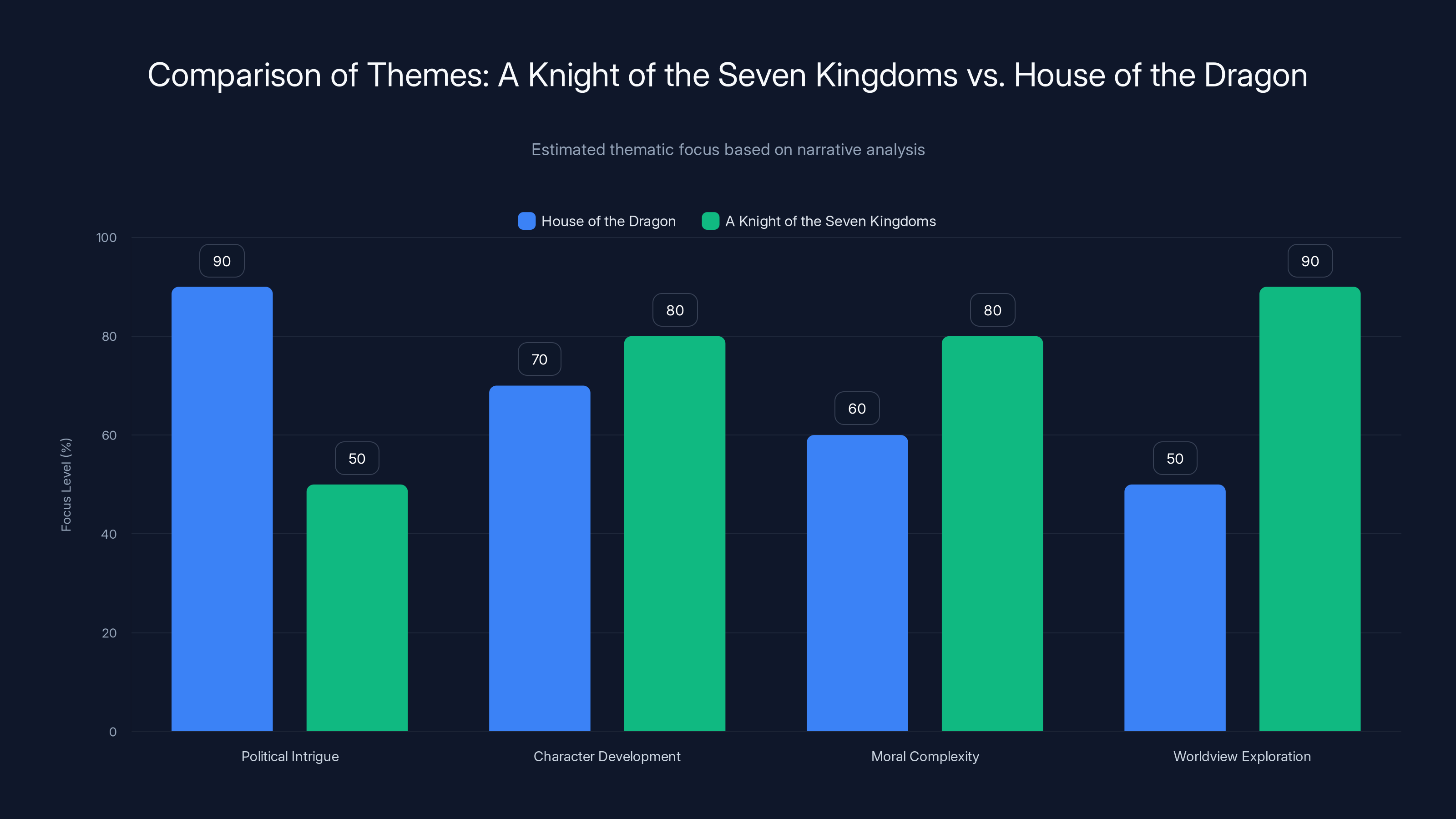

What's wild is how this approach feels like a completely different show from House of the Dragon, despite sharing the same world, the same mythology, and sometimes even overlapping timelines. Where House of the Dragon leans into political intrigue with the same dark, cynical tone Game of Thrones perfected, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms steps sideways and asks: what if we just followed some ordinary people trying to make their way in an extraordinary world?

The answer turns out to be: pretty damn entertaining.

The Perfect Buddy Cop Formula in Medieval Westeros

Let's talk about why the Dunk and Egg dynamic works so well. On paper, it sounds simple. Big clumsy knight. Smart kid. They travel around. They get into adventures. Seen that before, right?

Except this isn't a typical buddy comedy setup. Dunk and Egg actually need each other, and the show understands that interdependence completely. Dunk provides the muscle and the moral compass—he genuinely wants to do the right thing, even when the right thing gets him nothing. Egg provides the brains, the quick thinking, and the ability to talk them out of situations that Dunk's sword can't solve.

Peter Claffey's performance as Dunk is the secret weapon here. He plays Dunk with a kind of gentle confusion that makes the character incredibly watchable. When Dunk realizes he's messed something up—and he constantly messes things up—there's genuine mortification in his face. He's not embarrassed because he's stupid. He's embarrassed because he tried his best and still failed the people counting on him.

That's a specific kind of character work, and Claffey nails it. He's the kind of actor who can make you believe that a six-foot-tall man with a sword could be fundamentally insecure about his place in the world. His Dunk isn't performing strength. He just happens to be strong. Inside, he's genuinely worried that everyone will figure out he doesn't deserve the sword he carries.

Dexter Sol Ansell's Egg provides the perfect counterbalance. He's sharp, observant, and always one step ahead. But he's also a kid, which means he makes kid mistakes. He wants to prove himself. He acts before he thinks. His and Dunk's chemistry feels natural—there's genuine affection between them, mixed with exasperation and the kind of playful conflict that actual travel companions develop.

What makes this pairing work in the context of Game of Thrones is how fundamentally it rejects the show's original cynicism. Think back to Game of Thrones. The moral of that show, if it had one, was basically: nice people die, ambitious people win, and the only way to survive is to be willing to do terrible things. By the final season, nobody believed in honor or justice anymore. The system was rigged, so why bother?

Dunk still bothers. He knows the system is rigged. He's experienced it firsthand. But he doesn't accept it as inevitable. He treats it as a problem to solve, not a law of nature. And the show validates that approach, at least somewhat. His honor doesn't solve everything, but it consistently opens doors that cynicism would have slammed shut.

Each episode of A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is approximately 50 minutes long, totaling around five hours for the entire first season.

When Humor Actually Serves the Story

The biggest risk A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms takes is treating its protagonist as funny without making him a fool. This is harder than it sounds, especially in a franchise where irony and cynicism have been the default tone for over a decade.

Consider the jousting sequences. Dunk enters a tournament because he's trying to make a name for himself. In Game of Thrones, a hedge knight entering a fancy tournament would be setup for humiliation or death. The show would treat it as futility, proof that the system is designed to crush people like him.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms treats it differently. Yes, Dunk is outmatched. Yes, his armor is shabby and his equipment is worse. Yes, everyone judges him before the tournament even starts. But the show finds comedy in the reality of the situation rather than the hopelessness of it. There's a sequence where Dunk's horse won't cooperate, and it's genuinely funny—not because the show is mocking him, but because the situation is absurd and Dunk's response to the absurdity is immediate and honest.

That distinction matters more than you'd think. The humor comes from character and situation, not from the show winking at the audience. The series trusts viewers to laugh without making the joke a sign of contempt. It's a more sophisticated approach to comedy than you'd expect from a Game of Thrones property, which is probably why it works so well.

The show also uses humor to build character relationships. There's a running joke about Egg's relationship to Dunk's intelligence that's mean, absolutely, but it's the kind of mean that comes from real affection. Egg will say something that makes it clear he thinks Dunk isn't the sharpest sword in the armory, and Dunk's reaction—which is usually just confusion followed by acceptance—creates comedy through authenticity rather than mean-spirited jabs.

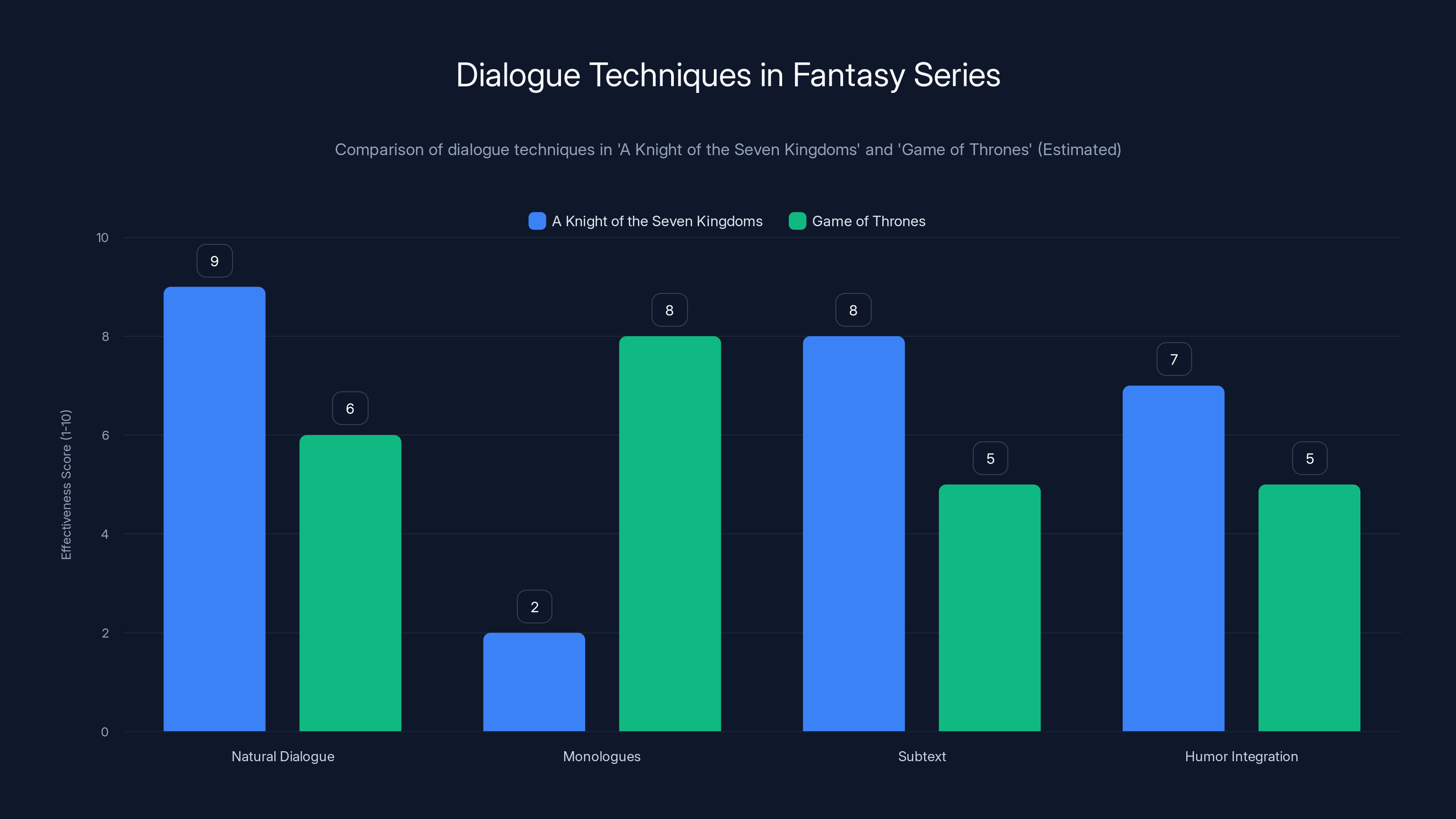

This is how you do character work through dialogue. The banter builds who these people are, how they relate to each other, and why they work as a team. It's not witty for witty's sake. It's funny because these characters are genuinely reacting to each other with honesty rather than performing for the audience.

The show even extends this approach to its supporting cast. There are scenes with minor characters where the humor comes from their personality and priorities clashing with the main story, rather than from the writers deciding to be funny. An innkeeper worried about his bar getting destroyed during a commotion. A merchant more concerned with getting paid than with the moral implications of a deal. These feel like real people with real concerns, which makes their scenes simultaneously funny and grounded.

House of the Dragon focuses heavily on political intrigue, while A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms emphasizes moral complexity and worldview exploration. (Estimated data)

The Tournament as Central Narrative Device

At the heart of the first season is a jousting tournament. This might sound anticlimactic compared to battles and political schemes, but it's actually a brilliant structural choice that reveals something fundamental about how A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms works.

Tournaments in Game of Thrones were usually just set dressing for plot. Remember the tournament in the pilot episode? It existed mainly to give Robert Baratheon an excuse to talk about his past and to set up Bran's injury. It wasn't the story. The story was always somewhere else—in King's Landing, in the dungeons, in the political calculations of people with actual power.

In A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms, the tournament is the entire story for the first season. Everything else flows from it. Dunk needs to win because winning would give him status and resources. Egg is interested in the tournament because it's where royalty will be gathered. Every subplot connects back to this central event, and the show doesn't treat it as small or unimportant just because there aren't dragons involved.

This is actually a more sophisticated narrative approach than it seems. By making a local tournament the centerpiece, the show forces viewers to care about stakes that are personal rather than existential. The fate of the Seven Kingdoms isn't hanging in the balance. Nobody's going to conquer everything or burn it down. But Dunk's reputation is on the line, and his ability to support himself is dependent on his performance. Those are the real stakes for his character, and they matter more than continental politics.

The tournament also functions as a stage for introducing the show's version of Westeros. We meet various lords and knights, each with their own motivations and personalities. We see how the nobility lives compared to the smallfolk. We understand the rigid hierarchy of this world and how difficult it is for someone like Dunk to move up through it. The tournament becomes a microcosm of the entire system, which makes it an effective way to worldbuild without exposition dumps.

What's particularly smart is how the show uses the tournament to explore the concept of honor in a world where honor is often performative. The elite participants care about glory and reputation, but they define those things through a lens of power and status. Winning the tournament for them means proving their martial superiority, which translates to political advantage. For Dunk, winning would mean something completely different—it would mean he's finally made it, finally proven his worth.

The collision of these different understandings of what the tournament means becomes the thematic engine of the series. It's not really about who wins the joust. It's about what winning means to different people, and whether honor is a luxury the poor can actually afford.

A Fresh Take on Westeros Without Losing Its Identity

One of the biggest challenges for any Game of Thrones spinoff is walking the line between familiarity and novelty. Go too far in either direction and you've either made a show that doesn't feel like it belongs in the same universe, or you've just made a Game of Thrones episode with a different cast.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms finds a middle path. It uses the same world, the same magic system (barely), and the same basic rules of how society works. But it tells a fundamentally different kind of story within that framework.

The visual style helps with this. Cinematographer Fabiana Wagner treats the Westeros of this era differently than House of the Dragon does. Where House of the Dragon goes for grand, operatic visuals, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is more grounded and naturalistic. The colors are earthier. The lighting is more realistic. You're seeing the world through Dunk's eyes as he travels through villages and countryside rather than through the perspective of people in castles who have the resources to make everything look impressive.

This visual choice alone signals that this is a different show. You're not watching the noble drama of the Targaryen civil war. You're watching a story about people on the road. The intimacy of the camera work and the scale of the locations reinforce that this is fundamentally a smaller, more personal story.

The production design also reflects this shift. The armor is more beat up and functional. The buildings look lived-in rather than iconic. There's dirt and grime and real texture to the world, which makes it feel like a place where ordinary people actually exist rather than a theater set designed for dramatic moments. This is what Westeros actually looks like when you're traveling through it with nothing, rather than what it looks like when you're in King's Landing attending grand tournaments.

But despite these tonal and visual shifts, the show never loses the identity of Game of Thrones. The magic is still rare and poorly understood. The politics are still brutal and unforgiving. The fundamental rules of this world—that power is concentrated in the hands of the few, that the system is rigged against the poor, that good intentions often aren't enough—all remain intact. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms isn't rejecting Game of Thrones. It's just telling a different kind of story within the same universe.

This chart compares viewer preferences for different elements in fantasy shows. 'A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms' focuses more on character development and atmosphere, while 'Game of Thrones' and 'House of the Dragon' emphasize action and plot twists. Estimated data based on typical viewer feedback.

The Smallfolk Finally Get a Spotlight

Game of Thrones had a complex relationship with class. On one hand, the series included a shocking number of scenes with peasants and working people, which gave the world texture and scale. On the other hand, these characters were almost always background, set dressing for the grand drama happening above them. When the show did focus on common people, it usually did so to show how brutal and meaningless their lives were—how the wars of nobles ground them to dust without caring whether they lived or died.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms inverts this dynamic. The smallfolk aren't background. They're not just victims of circumstance. They're the central characters, and their concerns are the story. Yes, nobles still exist and still wield power, but the show isn't interested in the grand strategy of the nobility. It's interested in how that power affects the people actually living in the world.

This creates a different kind of narrative entirely. In Game of Thrones, you always had the sense that individual action didn't really matter. The system was too powerful, the forces too vast, the game too rigged. Your personal choices were insignificant compared to the sweep of history.

In A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms, individual action matters because the story is about individuals. Dunk's choices have consequences for him and for Egg. They're not saving or destroying kingdoms, but they are determining whether they survive to the next day and whether they maintain their integrity while doing it. That creates a different kind of dramatic tension—more immediate, more personal, more satisfying in a way that the continental-scale politics of the earlier shows can't quite achieve.

The show also explores the economics of the smallfolk in a way that neither Game of Thrones nor House of the Dragon really does. Dunk and Egg don't have money. They have to earn it. This creates practical constraints on what they can do. They can't just hire an army or book a seat on a ship. They have to work, negotiate, figure out how to survive on limited resources. The show treats this not as a temporary hardship but as the fundamental condition of existence for ordinary people.

It's a reminder of something that Game of Thrones often forgot: that poverty isn't just dramatic flavor. It's actually a real constraint that affects what choices are available to you. When you don't have money, you can't take the easy path. You have to be clever, careful, and willing to accept less-than-ideal outcomes. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms understands this intuitively and builds its narrative around this reality.

Supporting Characters Who Feel Real

One of the show's greatest strengths is that it understands how to use supporting characters effectively. This might sound obvious, but it's actually a skill that Game of Thrones mastered early and then largely abandoned. Too many shows treat secondary characters as furniture designed to make the main characters look good. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms treats them as fully realized people with their own priorities and personalities.

Consider Prince Baelor Targaryen, played by Bertie Carvel. He's nobility, which might suggest he'd be the antagonist or at least an obstacle. But the show gives him actual depth. He's young, conflicted, trying to do the right thing within the constraints of his station. He's not evil. He's just privileged in ways that make certain things impossible for him to understand. The show finds comedy in that gap between his good intentions and his fundamental inability to see the world from Dunk's perspective.

Similarly, Daniel Ings's Ser Lyonel Baratheon isn't a simple villain. He's a knight with his own code of honor, which happens to conflict with Dunk's code. But the conflict isn't presented as one being right and the other wrong. It's presented as two different value systems in collision, each internally consistent, each with its own logic.

This kind of character work extends to minor characters as well. People Dunk and Egg meet in taverns or on roads have actual personalities and motivations. They're not just quest-givers or obstacles. They're people with their own concerns, their own economic pressures, their own reasons for doing what they do.

This approach to characterization does something subtle but important: it makes the world of Westeros feel inhabited. Not just by main characters whose lives are dramatic and interesting, but by actual people living actual lives. When you see a tavern keeper worried about his business, or a merchant calculating profit margins, or a farmer dealing with the consequences of local politics, the world becomes real in a way that even Game of Thrones, with all its budget and scope, sometimes couldn't quite achieve.

Dunk excels in physical strength and moral guidance, while Egg shines in intelligence and quick thinking. Their chemistry is a balanced mix of their strengths. Estimated data.

The Writing: Dialogue That Sounds Like People Actually Talking

Let's spend some time on the writing, because this is where A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms really separates itself from its predecessors. The dialogue sounds like people talking. This might seem like a low bar, but it's actually harder to achieve than you'd think, especially in a fantasy series where you're trying to maintain a consistent tone and world while also making sure viewers understand what's happening.

Game of Thrones had some genuinely excellent dialogue, but it also had a tendency toward speechifying. Important moments would turn into monologues. Characters would explain their philosophies and worldviews through extended speeches. This worked sometimes, but it also frequently made conversations feel staged and artificial.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms avoids this trap by keeping most conversations small and human-scale. When characters do have important things to say, they say them through implication and subtext rather than through explicit statement. There's a scene where Dunk and Egg discuss what it means to be a knight that's done almost entirely through action and brief exchanges rather than a lengthy conversation about philosophy.

The writing also uses silence effectively. There are moments where what matters isn't what's being said but what's being left unsaid. A character's face as they realize something. A pause in dialogue that's weighted with meaning. The absence of a reassurance that a character might normally offer. These moments build character and convey information without anyone having to explicitly state it.

The humor in the dialogue works the same way. There are jokes, yes, but they're built into the conversation rather than set up and punched out. A character says something for one reason, but it lands as funny because of the context and the way other characters react to it. The humor emerges from the situation and the character's personality rather than from the writer trying to get a laugh.

This kind of writing also makes exposition easier to handle. Fantasy shows have a constant struggle with exposition. You need to establish how magic works, what the political situation is, what the geography looks like—all without the audience realizing they're being lectured. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms handles this so smoothly that you often don't realize information is being provided. It emerges from conversations where characters are asking questions they would naturally ask, trying to understand things they would naturally be confused about.

Why This Approach Works Better Than House of the Dragon

It's impossible to talk about A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms without comparing it to House of the Dragon, especially since both are Game of Thrones properties that HBO is using to build out the Westeros universe.

House of the Dragon is a competent show. It has impressive production values, solid acting, and it tells a coherent story. But it's also fundamentally limited by its commitment to political intrigue as its central mode of storytelling. Every scene needs to be about positioning and advantage. Every character interaction is measured through the lens of power dynamics. The show understands that the world it's building is corrupt, but it accepts that corruption as inevitable rather than questioning whether it needs to be that way.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms questions that assumption. It asks: what if we followed characters who actively reject the cynicism that House of the Dragon treats as realism? What if we made a show where honor actually matters, not because the characters are naive, but because maintaining it is the only thing that keeps them sane in an insane world?

This doesn't make A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms better or worse than House of the Dragon. They're fundamentally different kinds of shows with different goals. But it does make A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms more interesting as a story about Game of Thrones' universe, because it suggests that the universe is bigger than the political drama that dominated the original series.

House of the Dragon tells you that the Seven Kingdoms are fundamentally corrupt, that power corrupts, and that everyone with ambition will eventually do terrible things. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms doesn't deny any of that, but it also shows that there are people living in that world who refuse to accept those conclusions. That's a more interesting and more complicated worldview, even if the show itself is smaller in scale.

The practical difference is visible in how each show treats its scenes. House of the Dragon builds toward moments of conflict and revelation. Every scene has an agenda—to establish power dynamics, to plant seeds for future conflict, to advance a political plot. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is willing to spend time on scenes that are just about character and relationship. A moment where Dunk and Egg are traveling and talking about nothing in particular. A scene in a tavern that's just about the texture of ordinary life.

This willingness to slow down and linger on human moments creates a different kind of engagement. You're not always wondering what's going to happen next. You're just enjoying the company of these characters and learning more about them and their world. It's a more intimate kind of storytelling, and it's surprisingly effective.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms excels in natural dialogue and subtext, contrasting with Game of Thrones' reliance on monologues. Estimated data based on narrative analysis.

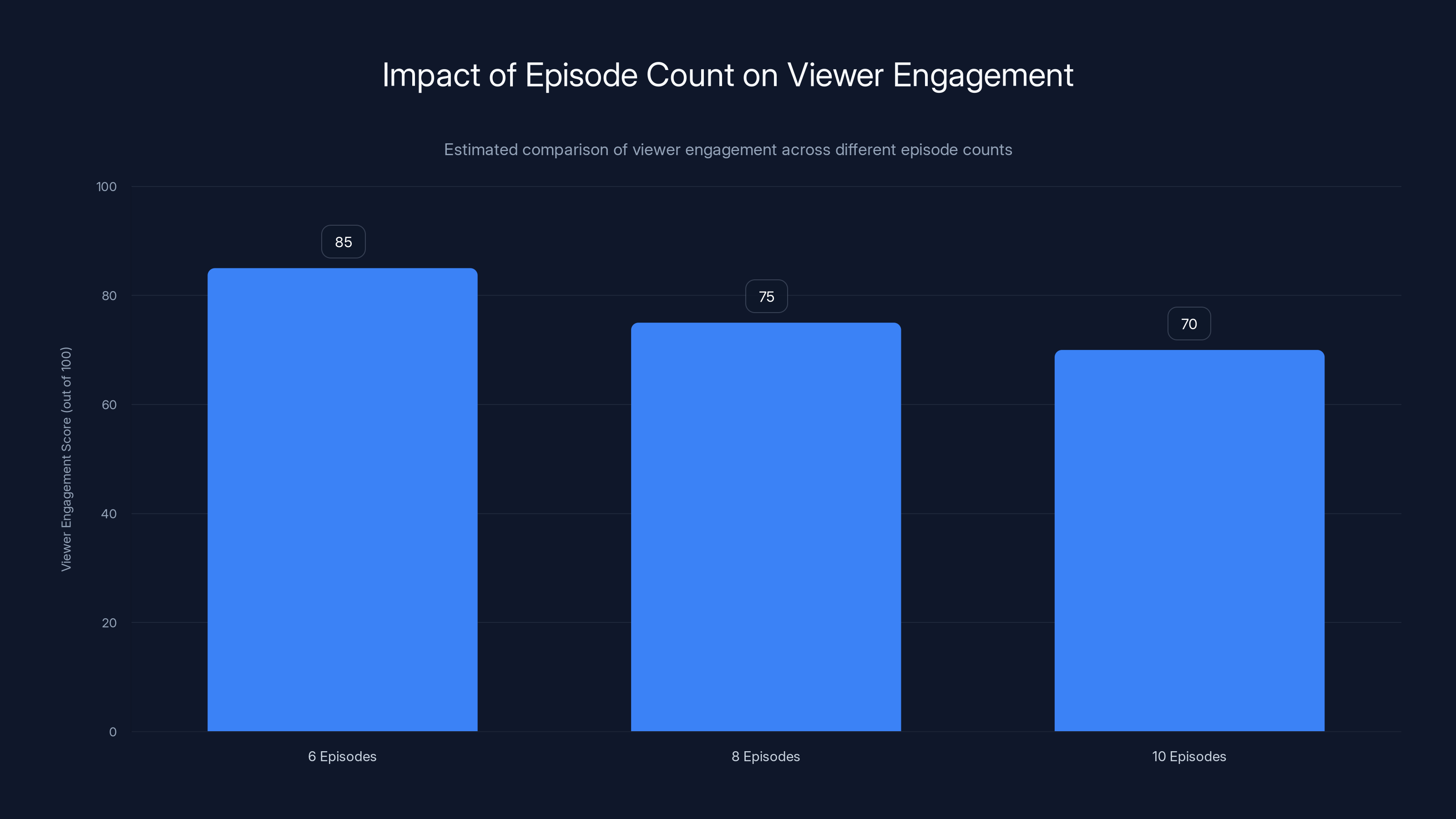

The Challenge of Ending Strong With Only Six Episodes

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms takes a deliberate risk by keeping its first season short. Six episodes instead of the typical eight or ten that Game of Thrones accustomed viewers to. This creates both advantages and challenges.

The advantage is pacing. Six episodes forces the show to be disciplined about what matters and what doesn't. There's no room for filler, no time for subplots that don't serve the central narrative. Everything has to count. Every scene has to move the story forward or develop character in a meaningful way.

The challenge is that six episodes might feel too short to newer viewers who are used to more traditional season lengths. Some might finish the season and feel like they didn't get enough story, that the ending came too quickly. This is partly an adaptation to the streaming era, where shorter seasons are increasingly common, but it's also a narrative choice that reflects the show's tighter focus.

Without spoiling where the season actually goes, the ending is both satisfying and open-ended. It resolves the central plot thread of the tournament while leaving larger questions unanswered. This is the right choice for a show that's planning to continue. It gives you closure on the immediate story while promising that there's more to explore with these characters.

The six-episode format also means the show can maintain quality throughout without the typical mid-season dips that longer shows sometimes experience. Every episode feels essential, which keeps the pacing tight and the viewer engagement consistent. You're never checking how much time is left in an episode, hoping something will pick up. The pace is already picked up from the beginning.

This format also has implications for how the show plans to continue. If the plan is multiple seasons of six episodes each, then A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is committing to remaining small and intimate in a way that Game of Thrones explicitly rejected. Game of Thrones seasons got longer and more packed as the show went on. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is moving in the opposite direction, and that's actually a more sustainable approach for telling stories about characters rather than about epic conflicts.

How This Could Shape the Future of Game of Thrones

The real significance of A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms isn't just that it's a good show. It's that it suggests a different approach to the Game of Thrones universe than HBO has been pursuing with House of the Dragon.

After the mixed reception to the final seasons of Game of Thrones, HBO has been cautious about how it develops new content in the universe. House of the Dragon was a bet that what audiences wanted was more political intrigue, more dragons, more of the things that made Game of Thrones successful at its peak. That bet has mostly paid off—House of the Dragon has been popular and critically acclaimed, even if it hasn't achieved the cultural dominance of Game of Thrones' early seasons.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is a different bet. It's betting that audiences also want character-driven stories that are intimate and human-scaled, stories where the focus is on ordinary people navigating an extraordinary world rather than on nobles fighting over power. It's betting that the Game of Thrones universe is large enough to contain both kinds of stories.

If A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is successful—and early signs suggest it will be—then HBO might start building a portfolio of different kinds of shows set in Westeros. Some focused on epic conflicts and political drama. Others focused on smaller, more personal stories. Some set during major historical events. Others just following people living their lives against the backdrop of that history.

This would actually be a smart approach to the franchise. The Game of Thrones universe is explicitly a world where multiple stories are happening simultaneously. Not everything is about the Iron Throne or the wars of the nobility. There are countless stories of ordinary people dealing with ordinary problems, and those stories are just as valid and just as interesting as the grand political narratives.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms proves that there's an audience for those stories. It proves that you can set a show in the Game of Thrones universe without constantly referencing dragons and kings and the major events that casual viewers associate with the franchise. You can just tell a story about people and let the world provide the context.

Estimated data suggests that shorter seasons, like six episodes, maintain higher viewer engagement due to tighter pacing and essential content.

The Performances That Make It All Work

A show is only as good as the people performing it, and A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms has assembled a cast that understands how to make this material work. The lead performances from Peter Claffey and Dexter Sol Ansell are excellent, but it's worth looking at the supporting cast as well, because they're doing subtle work that often goes unnoticed.

Bertie Carvel's Prince Baelor manages to be sympathetic despite being nobility in a show about the struggles of the poor. He's playing a character who genuinely wants to do the right thing but is fundamentally constrained by his position. Carvel plays this tension effectively—you can see Baelor recognizing Dunk's honor and wanting to respect it, even when he knows the system won't allow him to.

Daniel Ings as Ser Lyonel Baratheon is similarly nuanced. He could have been a simple antagonist, but Ings plays him as someone who has his own code of honor, even if it conflicts with Dunk's. There's respect between them even when they're opposed, which creates a more interesting dynamic than simple villain-versus-hero conflicts.

The supporting players—tavern keepers, merchants, other knights, family members—are all doing the work of making the world feel lived-in. They're not phone-ins or hired bodies. They're all bringing personality and specificity to their roles, even the ones that only appear in one or two scenes.

This is the kind of ensemble work that often gets overlooked. The lead actors get the attention, but it's the entire cast working at a high level that creates the texture and authenticity of the show. Everyone is taking their role seriously, even when it's a minor role. Everyone is doing the work to make their character feel real.

Peter Claffey in particular deserves recognition for his performance. Playing a character who is physically imposing but emotionally vulnerable is a difficult balance. Claffey makes you believe that Dunk is genuinely tough—he can handle himself in a fight, he's strong, he's intimidating just by existing in a room. But he's also kind, uncertain, and vulnerable to the opinions of others. It's a complete performance that gives the show its emotional center.

Practical Storytelling That Serves the Characters

One of the most underrated aspects of A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is how practical and grounded the storytelling is. The show isn't interested in magical solutions or epic coincidences. Problems are solved through character work and practical choices.

Consider how the show handles travel. Dunk and Egg are traveling with limited resources. This isn't just backdrop. It shapes what they can do, where they can go, and what choices are available to them. They can't just hire a horse. Dunk has to earn one. They can't just get food. They have to figure out how to obtain it or earn money to buy it. The practical constraints of their situation are woven into the narrative.

This approach extends to the larger plot. Nothing happens that contradicts the established rules of the world or the limitations of the characters. When problems arise, they're solved through the characters using their skills and intelligence, not through convenient plot devices or unexpected magical interventions. This creates a sense that the world operates according to consistent rules, which makes it feel real.

The show also uses money and economics in a grounded way. Characters care about whether they can afford things. Prices matter. The cost of equipment, the value of a prize, the amount needed to survive—these are all practical considerations that affect the plot. This is less flashy than sword fights or political intrigue, but it's actually more sophisticated storytelling because it reflects the reality of how most people have to live.

This approach also makes the small victories feel earned. When Dunk wins something or achieves something, you believe it because you've seen the effort required and the obstacles overcome. The satisfaction comes from character work and practical achievement, not from the plot giving the protagonist what they want because they're the main character.

The Visual Language of Traveling and Movement

Director Debs Lynn-Roy handles the visual storytelling with a specificity and attention to detail that elevates the material. The show is particularly good at using travel and movement to convey character and story.

When Dunk and Egg are on the road, the cinematography captures the reality of what travel would actually be like in medieval times. There's dust, there's exhaustion, there's the repetitive nature of movement from place to place. The show doesn't glamorize travel or turn it into a montage. It shows it as the grinding, mundane reality it would be, which makes the moments of beauty—sunset views, river crossings, moments of companionship—feel more earned and meaningful.

The show also uses the physical environment to tell story. Locations matter. The contrast between Dunk's shabby traveling clothes and the fine garments of the nobility is visually apparent. The difference between the common inn where Dunk stays and the castle where the tournament is happening is clear just from looking at them. The visual language reinforces the hierarchies and inequalities that the story is exploring.

Much of the effective visual storytelling comes from composition and framing rather than from elaborate camera moves or effects. The show trusts the viewer to read meaning from what's in the frame and how it's arranged. A scene might tell you something about a character's emotional state not through dialogue but through how the camera frames them relative to their surroundings.

This is the kind of visual work that often goes unnoticed because it's so effective that it feels invisible. You're watching the story, not noticing the filmmaking. But that invisibility is the point. The technique serves the story rather than calling attention to itself.

What A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms Gets Right About the Source Material

The Tales of Dunk and Egg novellas are beloved by George R. R. Martin fans, and for good reason. They're some of his finest writing—shorter works that focus on character and situation rather than the sprawling political narratives of the main series. They're also vastly less known than the main Game of Thrones books, which gives the show significant creative freedom.

The show honors the source material while also expanding it and making changes where necessary. The core characters and their relationship remain faithful to Martin's version. The basic plot of the first tale, "The Hedge Knight," is recognizable if you know the source material. But the show adds texture, develops supporting characters more fully, and creates new scenes that expand the world.

This is the right approach to adaptation. Reverence for the source material doesn't mean slavish adherence to every detail. It means understanding what makes the source material work and preserving that essence while making changes that serve the visual medium and the extended format of a television series.

The show also captures what Martin was doing in these novellas—creating stories that are fundamentally optimistic compared to the main series. The Dunk and Egg tales suggest that honor and goodness still matter, that it's possible to live with integrity in a corrupt world, that there are people trying to do the right thing even when the system is against them. This tone is preserved in the show, which is why it feels so different from both Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon.

Potential Criticisms and Fair Counterarguments

To be fair, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms isn't perfect, and there are legitimate criticisms that could be made of it.

Some viewers might find the pace too slow. This show prioritizes character and atmosphere over plot momentum. If you're looking for constant action and shocking plot twists, you might be disappointed. The tournament structure means that for much of the season, the trajectory is fairly predictable. You know where the story is heading, and the show takes its time getting there.

The answer to this is that different shows are for different audiences. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms isn't trying to be Game of Thrones. It's trying to be something different. If you want rapid-fire plot developments and constant surprises, House of the Dragon might be more your speed. But if you're okay with a show that trusts its characters and takes time to develop them, then the slower pace is a feature, not a bug.

Another potential criticism is that the show might feel slight compared to the massive scope of Game of Thrones. Six episodes with modest production values and a small cast might feel like a step down after the dragons and battles of the earlier shows. But again, this is partly the point. The show is deliberately choosing to be smaller because that allows for a different kind of storytelling.

There's also the question of whether the show will be able to sustain itself over multiple seasons. Six episodes for a first season is good. But can that format continue without the show feeling repetitive? This remains to be seen, but the creators seem confident that they have more stories to tell with these characters.

These criticisms are fair, and different viewers will have different answers to them. The important thing is that A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is doing something deliberately different, and it's doing that thing well.

The Future of Dunk and Egg Beyond This Season

If A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms gets renewed for additional seasons—which seems likely given the positive response—the question becomes: where does the story go from here?

George R. R. Martin has written three Dunk and Egg novellas. The show adapted the first one over six episodes, which means there's material for future seasons. However, the show has also added new material and expanded beyond the exact novellas, which suggests that it's not planning to do a direct page-to-screen adaptation of the remaining stories.

This is actually a smart move. The novellas are short, and stretching them into full seasons would require significant padding. By creating new material and expanding the world, the show can build something that's longer and richer than the source material while still maintaining fidelity to Martin's core ideas and characters.

The challenge will be maintaining the balance that makes the first season work. If the show gets bigger—more episodes, more budget, more scale—it might lose the intimate character focus that makes it different from House of the Dragon and Game of Thrones. The test of whether A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is a success isn't just whether it gets renewed, but whether it can remain true to what makes it special while still giving audiences more of what they want.

Why This Matters for the Game of Thrones Franchise

Ultimately, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms matters because it proves that the Game of Thrones universe is large enough to contain multiple kinds of stories. It's not just about political intrigue or dragons or wars for the throne. It's about people living in a complex world and trying to figure out how to maintain their integrity while doing so.

The original Game of Thrones suggested that this integrity was impossible, that the system was so corrupt that anyone who tried to maintain it was a fool doomed to fail. By the end of the series, the show had broken most of its characters, either through death or through the realization that morality was a luxury they couldn't afford.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms suggests a different possibility. Yes, the system is corrupt. Yes, honor is difficult. Yes, good people often don't win. But there are still people who try. There are still people who believe that maintaining your integrity matters more than achieving power. And that struggle to hold onto your values in a world that doesn't reward them is a story worth telling.

This is actually the most important contribution that A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms makes to the Game of Thrones universe. It suggests that there's hope for optimism within this world, that cynicism isn't the only honest response to how things are, and that ordinary people trying to do the right thing are interesting enough to carry an entire series.

For a franchise that ended on a fairly cynical note with Game of Thrones' final seasons, this is a welcome rebalancing. It opens up possibilities for future shows that focus on different aspects of the world, different kinds of characters, and different kinds of stories. It suggests that Game of Thrones isn't just about the epic conflicts and the major historical events. It's about all the people living in this world, all their stories, all their struggles.

Final Verdict: Game of Thrones Finally Found Its Sense of Humor

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is simply a great piece of television. It's funny without being silly. It's character-driven without being slow. It's respectful to its source material while also doing its own thing. It's scaled smaller than its sister show, but that smaller scale allows for more intimacy and more focus.

Most importantly, it proves that the Game of Thrones universe doesn't need to be dark, cynical, and nihilistic to be interesting. You can tell stories set in Westeros that find meaning in honor, that suggest that goodness matters, that explore what it means to try to live ethically in an unethical world. These stories are just as valid as the political dramas and just as compelling.

If you're a fan of Game of Thrones, you should watch this. If you bounced off House of the Dragon because you wanted something different, you should definitely watch this. If you've never seen anything Game of Thrones related and are interested in a well-made fantasy series about interesting characters, you should watch this. It's only six hours of your time, and it's six hours very well spent.

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms proves that HBO still understands how to make great television set in this world. It's just that this time, they remembered that characters matter more than spectacle, and that laughter might be just as powerful as dragons.

FAQ

What is A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms?

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is a HBO television series set in the Game of Thrones universe approximately 100 years before the events of the original series. Based on George R. R. Martin's Tales of Dunk and Egg novellas, the show follows the adventures of Ser Duncan "Dunk" the Tall, a humble hedge knight, and his young companion Egg as they travel through Westeros seeking fortune and honor. Unlike the grand political dramas of Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon, this series takes an intimate, character-driven approach to storytelling within the same fantasy world.

Who are the main characters in A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms?

The series centers on two primary characters. Ser Duncan "Dunk" the Tall, portrayed by Peter Claffey, is a physically imposing but emotionally vulnerable hedge knight who believes genuinely in honor and justice despite living in poverty. Egg, played by Dexter Sol Ansell, is a precocious young boy with sharp intelligence and mischievous tendencies who becomes Dunk's squire and traveling companion. Their relationship forms the emotional core of the series, with their contrasting personalities and complementary skills creating compelling character dynamics and humor.

How many episodes are in the first season?

The first season of A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms consists of six episodes, each approximately 50 minutes in length. This shorter season structure represents a deliberate creative choice that allows the show to maintain tight pacing and avoid filler content. The six-episode format totals roughly five hours of television, making it more concise than typical Game of Thrones or House of the Dragon seasons while delivering a complete narrative arc centered around the central tournament that drives the season's plot.

What makes A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms different from other Game of Thrones shows?

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms distinguishes itself through several key differences from its predecessors. First, it centers on ordinary people and smallfolk rather than nobility and high politics. Second, the show embraces humor and lighter tones while maintaining the world's gritty authenticity. Third, it focuses on intimate character relationships and personal stakes rather than continental-scale political conflicts. Fourth, it presents a more optimistic perspective on honor and integrity, suggesting that maintaining values matters even in a corrupt system. Finally, its smaller scale and shorter episode format allow for more focused storytelling and character development compared to the epic ambitions of Game of Thrones or House of the Dragon.

Is prior Game of Thrones knowledge necessary to enjoy the series?

While familiarity with the Game of Thrones universe certainly adds context and enriches the viewing experience, it's not strictly necessary to enjoy A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms. The show is set 100 years before Game of Thrones and tells a complete story that stands on its own merit. The world's basic rules—feudal hierarchy, honor codes, limited magic—are explained naturally through the narrative. Viewers new to the franchise can understand the series without having seen earlier shows, though longtime fans will appreciate additional details and Easter eggs that reference the broader history of Westeros.

What is the tournament central to the first season?

The tournament is a jousting competition that serves as the narrative anchor for the first season. Dunk enters the competition hoping to win the prize money and gain reputation that will establish him as a legitimate knight rather than just another poor hedge knight. For Dunk, winning would represent a genuine achievement and path upward. However, the tournament also attracts nobility and young princes who view it as entertainment rather than as a serious competition with real stakes. The tournament functions as both a practical plot driver and a metaphorical stage for exploring themes of class, merit, honor, and the collision between different value systems in Westeros society.

Where does A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms take place chronologically?

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is set approximately 100 years before the events of Game of Thrones, during a period that overlaps with some of the events covered in House of the Dragon but takes a completely different narrative approach. This temporal placement allows the show to explore Westeros history without constantly requiring references to the major historical events that define the main series. The characters and conflicts of A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms are self-contained, though the world and its political structures exist as part of the same continuum that eventually leads to Game of Thrones.

Is there a second season planned?

While HBO has not officially announced renewal details at the time of this article, the show has already suggested potential for continuation. The showrunners have mentioned in interviews that there is more material from Martin's novellas to adapt, and the first season's ending, while providing closure on the immediate tournament plot, leaves larger questions about the characters unanswered. Whether the show continues likely depends on viewer reception and critical response, but the creators appear confident in their ability to sustain the story over multiple seasons while maintaining the quality and character focus that makes the first season successful.

Key Takeaways

- A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms takes a fundamentally different approach from Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon by centering on ordinary people and their personal struggles rather than nobility and continental politics

- The show successfully blends humor with character depth, proving that the Westeros universe can be funny without being silly or undercutting its dramatic stakes

- Peter Claffey and Dexter Sol Ansell's performances create genuine chemistry and emotional authenticity that anchors the entire six-episode season

- By keeping its first season short (six episodes) and focused, the show maintains tight pacing and avoids the filler that sometimes undermines longer seasons

- The series demonstrates that the Game of Thrones universe is large enough to contain multiple kinds of stories, not just political intrigue and dragon warfare

![A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms Review: Game of Thrones Gets Funny [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/a-knight-of-the-seven-kingdoms-review-game-of-thrones-gets-f/image-1-1768484572728.jpg)