Introduction: The Contradiction at Apple's Core

Apple builds its brand on a foundation of carefully curated principles. Privacy. Security. Social responsibility. The company opens product events with stirring tributes to civil rights leaders. It resists government demands for backdoors. Yet in October, when the Trump administration pressured the company to remove tracking apps, Apple capitulated without the public drama of resistance that typically accompanies its privacy stances. According to Gadget Hacks, this decision was influenced by government pressure.

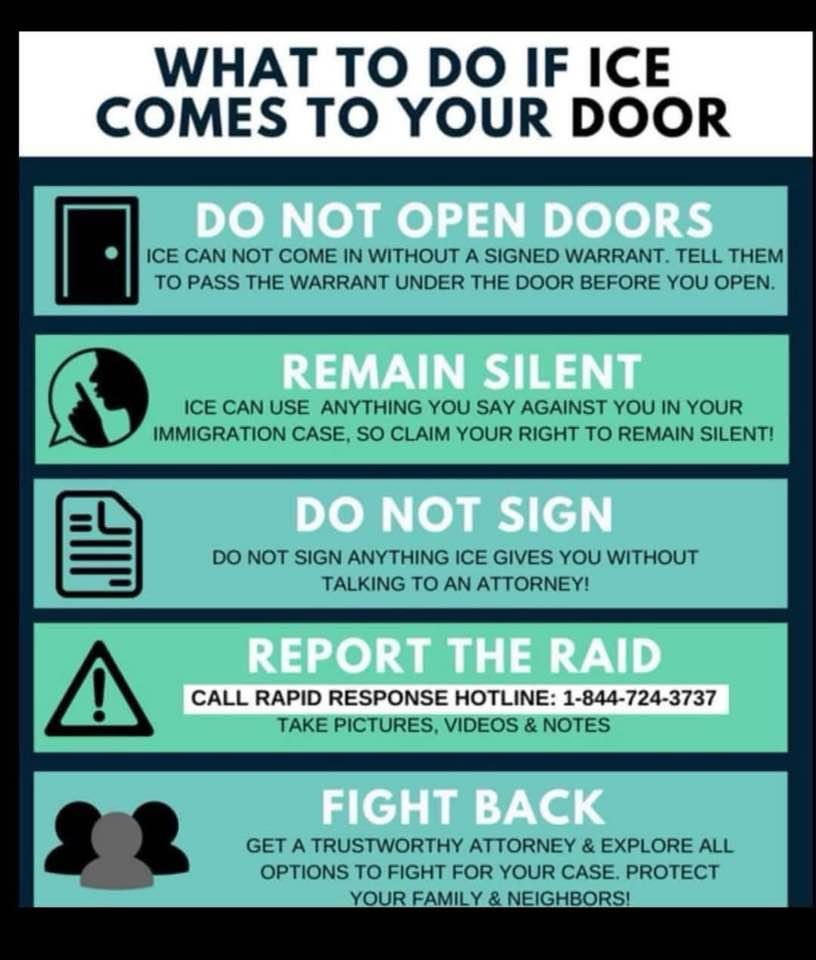

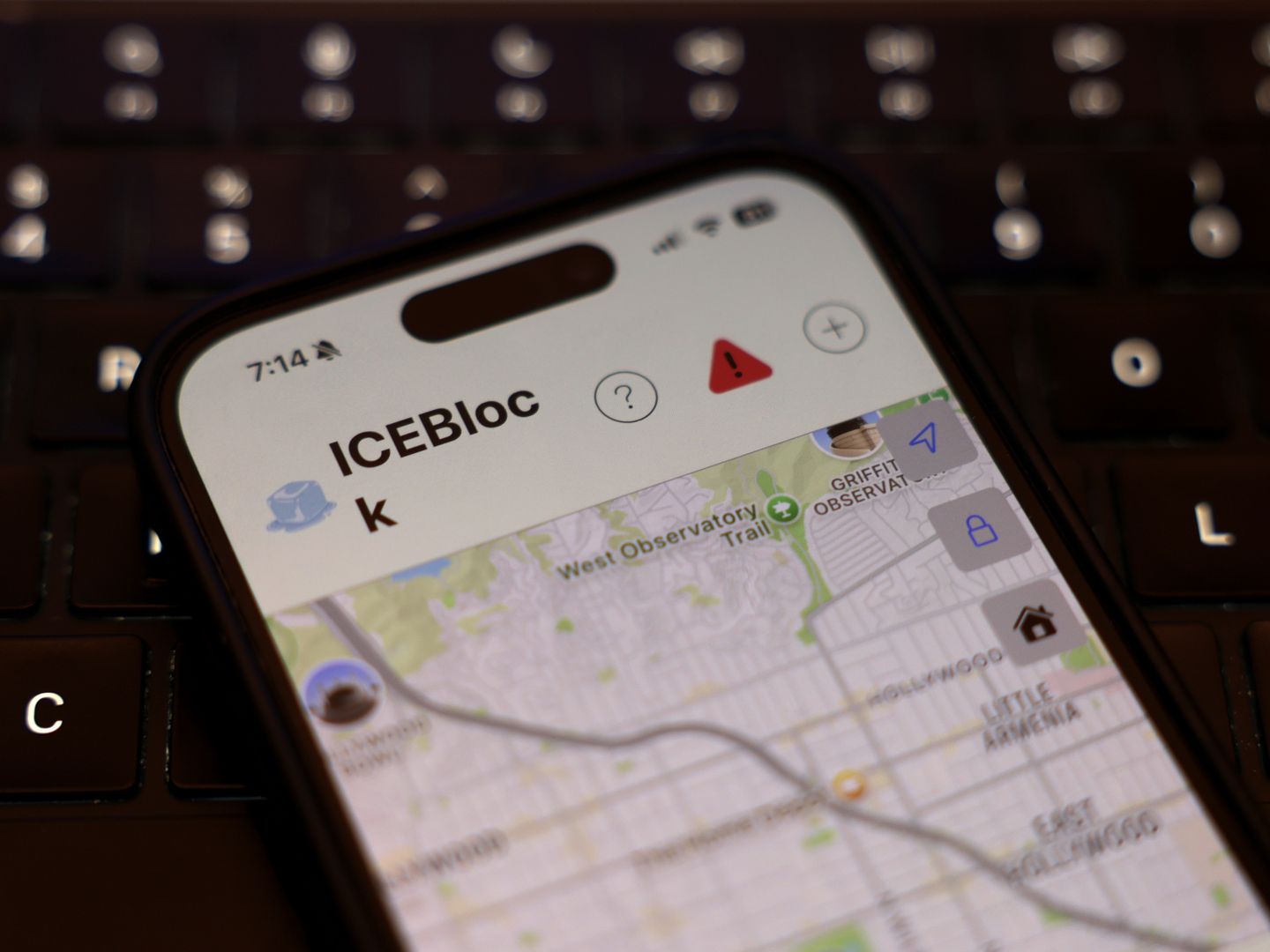

The app in question was ICEBlock—a crowdsourced tracking tool that let citizens report locations of Immigration and Customs Enforcement activity in their neighborhoods. Apple claimed the apps posed a danger to law enforcement officers, as reported by NBC5. But that framing inverts the actual risk. The real danger wasn't to ICE agents. The danger was the loss of a tool that helped vulnerable communities protect themselves from an agency with a documented history of excessive force, as noted by The Daily Record.

This moment matters because it reveals something uncomfortable about corporate "values." Apple doesn't oppose government pressure uniformly. It opposes it selectively, based on political winds and profit calculations. When tech transparency serves marginalized communities, Apple finds reasons to restrict it. When transparency serves corporate interests, Apple becomes its loudest defender.

What happened with ICEBlock wasn't an isolated decision. It's part of a broader pattern where tech platforms claim to champion civil rights while simultaneously removing tools that empower communities to defend those rights. Understanding why Apple made this choice—and what would need to change for the company to reverse it—requires examining the intersection of corporate values, government power, and civic accountability.

The stakes are high. When citizens lose tools to document and share government activity, they lose transparency. When tech companies remove those tools under pressure, they become complicit in restricting public information. And when that information matters most to people facing potential harm from law enforcement, the consequences aren't theoretical—they're measured in lives.

The ICEBlock Story: What Was Lost

ICEBlock wasn't complicated. The app worked by gathering real-time reports from users about ICE activity in their area. Someone would see agents conducting an operation and report it through the app. Other users could see these crowdsourced location markers on a map. If you were undocumented, had family members who were, or simply wanted to avoid the area, you had actionable information.

The app operated on the same principle as Waze traffic reporting—except instead of avoiding congestion, you were avoiding federal agents. This wasn't vigilantism. It wasn't organizing to obstruct law enforcement. It was information sharing among civilians about public agency activity, as explained by The Montclarion.

Apple characterized this as a threat to officer safety. This framing requires interrogation. ICE agents don't work undercover in the way that would make their locations genuinely sensitive information. They conduct raids, typically with multiple agents, often in uniform, using vehicles marked with federal insignia. The idea that a crowdsourced map of raid locations creates danger for these heavily armed, heavily supported agents doesn't hold up to scrutiny.

What's actually dangerous is the power imbalance between ICE and the communities it targets. Undocumented immigrants are among the most vulnerable populations in America. Many fear police contact, not because they're criminals, but because immigration status creates vulnerability. An app that allowed communities to share information about enforcement activity wasn't offensive power—it was defensive information.

The removal happened quietly, without the public pressure campaigns that surrounded Apple's previous government resistance moments. That silence was significant. It suggested the company either agreed with the framing or felt the political cost of resistance outweighed the principle at stake.

Estimated data suggests government pressure was a primary factor in ICEBlock's removal, with policy violation and public safety concerns also cited.

The Broader Context: ICE's Track Record of Violence

To understand why the loss of ICEBlock matters, you need to know what ICE actually does and how it does it. The agency operates with relatively little public oversight and significant discretionary power.

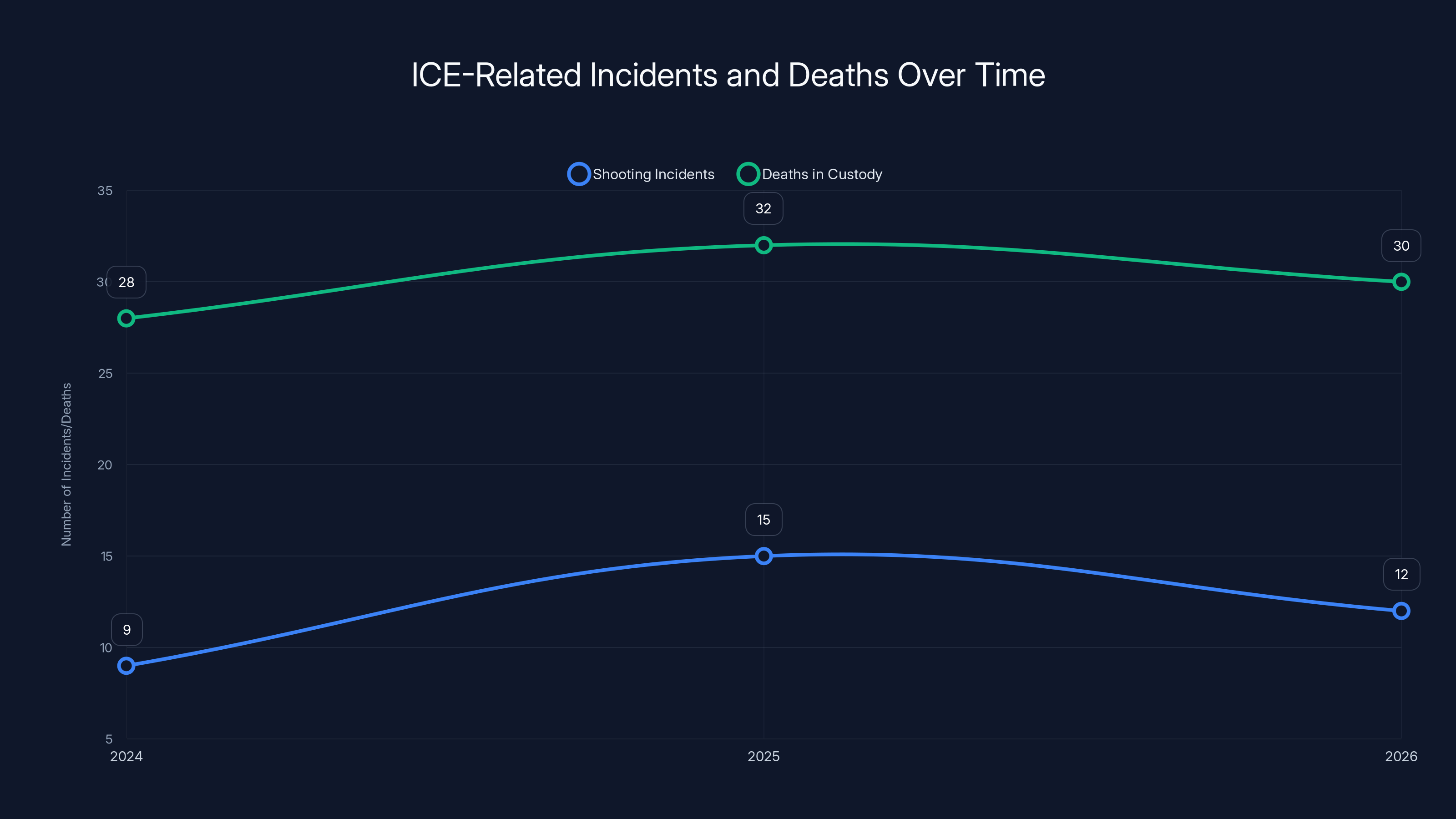

Consider the numbers. Since September 2024, ICE has been involved in nine shooting incidents. That's a rate of violence suggesting either systemic problems with training, culture, or decision-making. One incident in particular—the case of Renee Nicole Good in January 2026—illustrates why a tracking app might matter to potential targets.

Good was a white American citizen, a mother, according to accounts from those who knew her. She was killed by ICE agent Jonathon Ross. The details are brutal, well-documented, and widely reported. What matters here is the broader pattern: ICE had killed 32 people in custody during 2025 alone. The agency's shootings had escalated during the Trump administration, mirroring the broader intensity of immigration enforcement activity, as highlighted by Minnesota Daily.

More than a third of people arrested by ICE don't have criminal records. Let that sink in. The agency is stopping and detaining individuals whose only violation is immigration status. Many agents refuse to identify themselves during operations, creating situations where citizens can't know whether they're dealing with legitimate law enforcement or imposters.

These aren't abstract concerns. They're lived experiences for millions of people in the United States. For documented immigrants, for mixed-status families, for anyone whose status is uncertain, ICE represents real danger. That danger isn't theoretical—it's measured in families separated, in deportations to countries where people face persecution, in deaths in custody.

Against this backdrop, a tool that let communities share information about where enforcement activity was happening wasn't creating danger. It was offering a form of protection that law enforcement refused to provide through official channels.

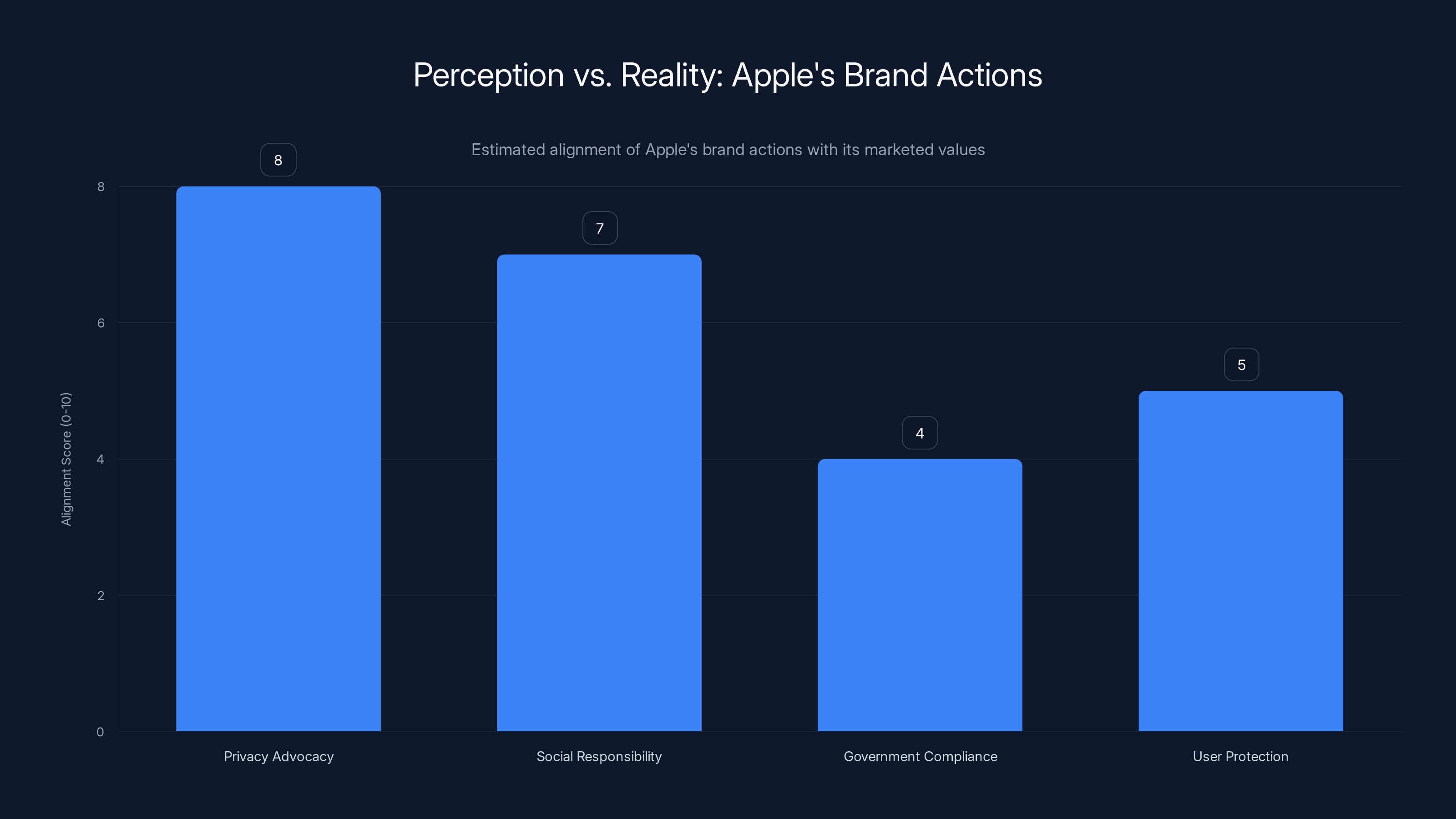

Estimated data shows Apple's strong alignment in privacy advocacy but lower in government compliance and user protection, highlighting discrepancies in brand actions.

Why Apple's "Officer Safety" Argument Fails

Let's examine the specific claim that ICEBlock created danger for law enforcement officers. This argument appears compelling at first—nobody wants to endanger people doing their jobs. But it collapses under scrutiny.

First, consider the operational reality of ICE. Agents work in teams. They have radio communication, backup, and overwhelming force advantage. They operate vehicles and conduct operations in public spaces. The idea that a map showing where citizens saw agents creates tactical danger is inconsistent with how law enforcement actually operates.

Second, consider what information ICEBlock actually made public. It was citizen reports about public activity—agents visible in neighborhoods, conducting visible operations. This wasn't classified intelligence. This wasn't surveillance of officers' homes. This was information about activity happening in plain sight, reorganized by technology to be more accessible.

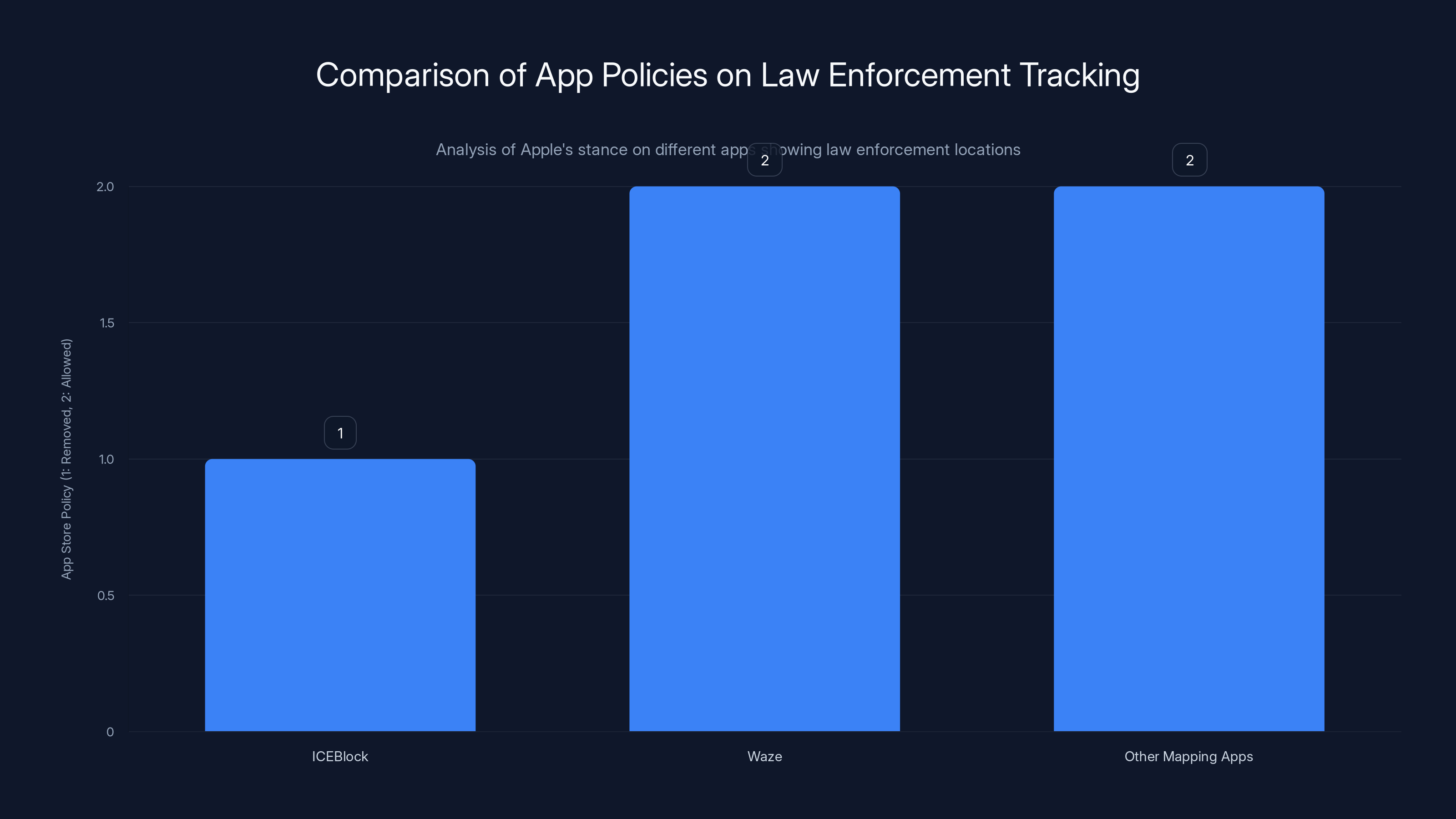

Third, Apple itself contradicts this logic in other contexts. The company allows mapping apps that show police locations. Waze displays police officer positions reported by users. That app operates in exactly the same way—citizens report what they see, the information gets aggregated and displayed. If crowdsourced police location reporting creates danger, Waze should create identical danger. Yet Apple maintains Waze in the App Store without hesitation.

The inconsistency suggests that Apple's concern wasn't genuinely about officer safety. It was about political pressure and the targeting of a specific agency. When police generally are tracked by Waze, that's fine. When immigration enforcement specifically is tracked by ICEBlock, suddenly officer safety becomes paramount.

This inconsistency reveals the real logic at work. Apple didn't ban ICEBlock because of abstract officer safety concerns. It banned it because the Trump administration applied pressure and the company calculated that resistance would cost more than compliance, as noted by Point Blank News.

The Good Case: When Information Failure Becomes Fatal

On January 8, 2026, the abstract debate about ICEBlock's purpose became irrelevant. What remained was the concrete reality that a person—Renee Nicole Good—was killed by a federal agent, and the information ecosystem that might have helped prevent that death had been removed from the platform millions of people use daily.

The details of the incident are important. Good was a white American citizen. She had a family. By accounts from people who knew her, she was kind, involved in her church, a good mother. The killing appeared to be unprovoked or responded to minor non-compliance with grossly excessive force. Video evidence documented the incident.

What's particularly significant is the official response. Vice President JD Vance immediately attacked Good's reputation, claiming without evidence that she was part of a "left-wing network." The framing moved quickly from incident investigation to political narrative management. The White House press secretary characterized her death as resulting from "left-wing movements." The FBI blocked Minnesota's criminal investigation from accessing evidence.

In this context, what would ICEBlock have meant? Not certainly prevention—no tracking app guarantees that. But possibly awareness. If Good or those around her had access to real-time information about ICE activity in Minneapolis, they might have stayed home. They might have avoided the location where the encounter happened. Information doesn't guarantee safety, but its absence guarantees vulnerability.

The timing of the killing—less than three months after Apple removed ICEBlock—isn't coincidental in its relevance. The app's removal and the death both illustrate the same principle: when vulnerable communities lose tools to protect themselves, the results are measured in human cost.

Apple's stated position would be that they bear no responsibility for what happened. Technically, that's defensible. Apple didn't remove ICEBlock because they predicted a specific death. But the moral position is weaker. Apple removed a tool designed specifically to protect vulnerable people from enforcement activity. An enforcement agent then killed a person. That sequence deserves hard thinking.

Estimated data shows a concerning trend in ICE-related shooting incidents and deaths in custody, highlighting systemic issues within the agency. Estimated data.

Apple's Progressive Brand and Its Actual Values

Apple markets itself carefully. The company's keynote presentations include testimonials from people whose lives were saved by iPhone and Apple Watch features. The company releases pride month accessories celebrating LGBTQ+ communities. Apple's leadership speaks about social responsibility. The company resisted government pressure during the San Bernardino iPhone case, positioning itself as a defender of privacy against surveillance.

This brand identity is valuable. It distinguishes Apple in a technology sector where privacy and corporate responsibility are increasingly important. Consumers choose Apple partly because of this positioning. Investors trust the company to navigate regulatory pressure while maintaining principles.

But the brand requires alignment with actual behavior. And that alignment is more complicated than Apple's marketing suggests.

Consider Apple's resistance to government demands in the San Bernardino case. The company fought vigorously against FBI pressure to create a backdoor into encrypted communications. That was authentic resistance, costly in political terms, and defended a genuine principle. The company positioned itself as protecting all users' privacy against government overreach.

Yet with ICEBlock, the company took the opposite position. When the government applied pressure, Apple complied. When citizens requested tools to protect themselves from government overreach, Apple removed them. The difference in behavior is stark.

One explanation is that San Bernardino involved a threat to Apple's business model—if the company created encryption backdoors, that would affect security across all platforms, creating ongoing liability and business risk. ICEBlock involved no such threat. The app didn't undermine iOS security. It didn't create ongoing obligations for Apple. Removing it was simple compliance, with no cost to the company's core business.

That's the pattern that deserves attention. Apple defends privacy and user autonomy when defending them aligns with business interests. When defending privacy or user autonomy creates business friction, Apple finds reasons not to.

This isn't unique to Apple. The technology industry broadly has embraced a progressive brand identity while maintaining business practices that are substantially more conservative. Companies claim to support civil rights while removing tools that facilitate civic accountability. They claim to oppose surveillance while participating in government data requests. They claim to support free expression while moderating content for political rather than clearly defined community reasons.

Apple's specific choices matter because the company has significant power. The App Store controls what 2 billion iPhone users can access. That power carries responsibility. Using that power to remove tools that help vulnerable communities protect themselves—under the guise of officer safety that the company doesn't actually apply consistently—is a misuse of that power.

The Government Pressure: How Threat Operates in Practice

Understanding why Apple made this decision requires understanding how government pressure actually works in practice. It's rarely explicit coercion. It's typically more subtle.

The Trump administration applied pressure on Apple to remove ICEBlock. The details of how that pressure was communicated aren't entirely public, but the outcome was clear. Within a specific timeframe, Apple removed the app and similar tools. The company claimed this was a voluntary decision based on policy review, as noted by CalMatters.

This is how government pressure typically operates in the tech industry. There's rarely a direct command with consequences explicitly stated. Instead, there's communication about what the government would prefer, suggestions about regulatory consequences if preferences aren't met, and implications about political relationships that might be affected.

For a company like Apple, heavily dependent on government approval across multiple jurisdictions, these suggestions are functional threats. The company might face regulatory scrutiny, investigation, or unfavorable treatment in other domains. The cost of compliance is minimal—remove one app from the App Store. The cost of resistance is uncertain but potentially significant.

This dynamic creates a systematic bias toward compliance. Companies will comply with government pressure when the cost of compliance is low and the potential cost of resistance is high. When protection of vulnerable communities is what's at stake, those communities lose.

Apple claims that ICEBlock violated App Store policies around content that "could be used to harm law enforcement officers." But the policy itself is the problem. That policy wasn't created because users requested it. It existed as a tool for the company to enforce values selectively. Once government pressure arrived, that tool became a mechanism for removing content the government disliked.

This matters because it's a precedent. Once Apple established that it would remove applications under government pressure related to law enforcement, other governments know they can replicate the pressure for other applications. The mechanism works. Future requests will follow.

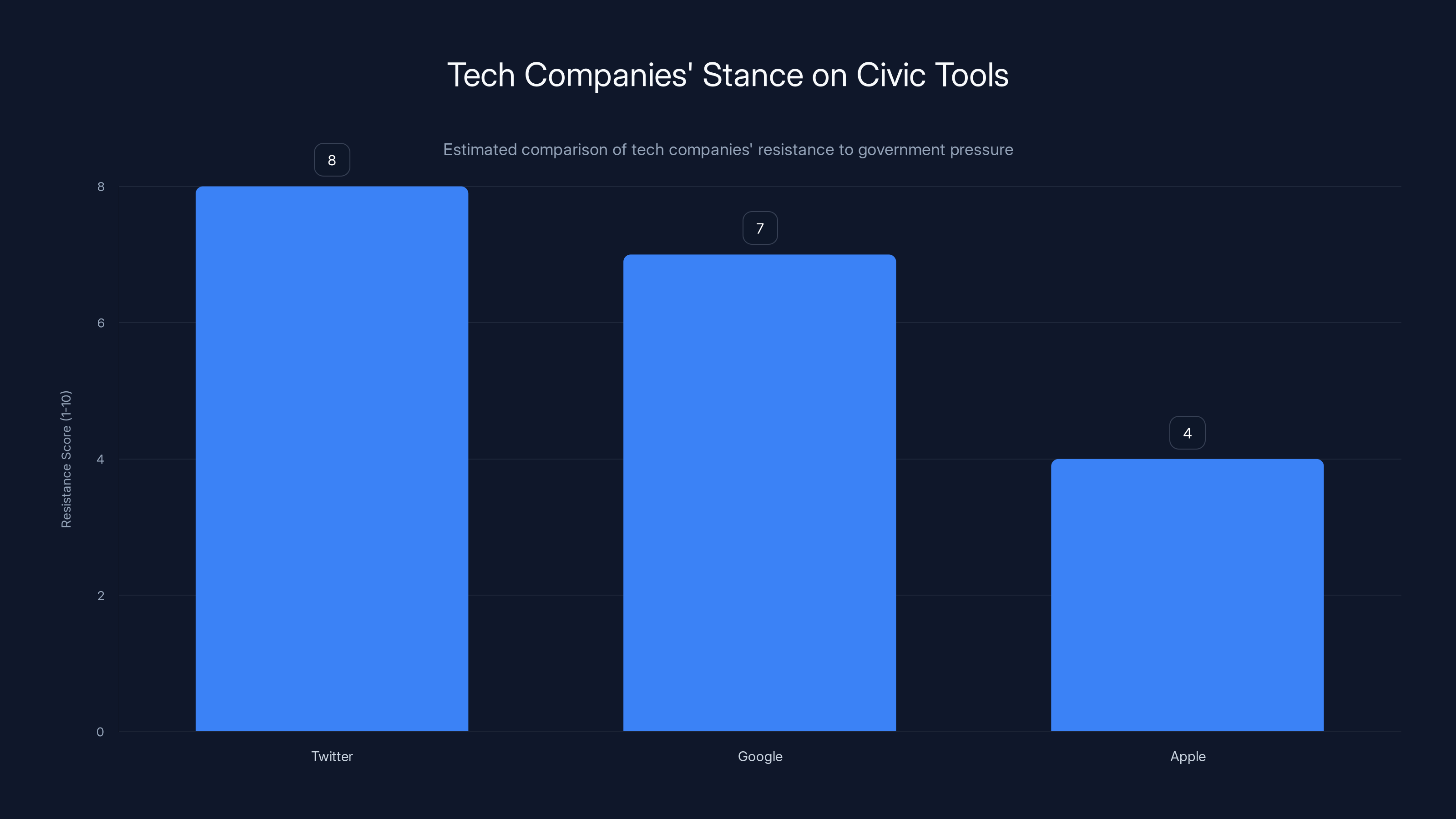

Twitter and Google have shown higher resistance to government pressure compared to Apple in protecting civic tools. Estimated data.

Comparable Cases: When Tech Companies Defend Civic Tools

Apple's decision with ICEBlock isn't inevitable. Other tech companies have made different choices when facing similar pressure, and those choices produced different outcomes.

Take Twitter's approach to protest documentation. After high-profile incidents of police violence, Twitter explicitly stated that it would not remove tools or applications that documented law enforcement activity. The company resisted pressure from law enforcement to remove live-streaming features or location documentation. That resistance involved actual cost—public criticism from police organizations, regulatory pressure from some jurisdictions, potential consequences for the company's relationship with law enforcement.

Twitter chose to protect the tool anyway. The choice reflected a calculation that the civic value of documentation outweighed the political cost of maintaining it. Whether or not you agree with all of Twitter's other decisions, this particular choice prioritized transparency and accountability.

Google's approach to mapping features provides another comparison. Police departments have regularly requested that Google Maps not show police station locations or remove features that display police presence. Google has declined these requests. The company maintains that mapping police locations doesn't violate its policies and serves legitimate civic purposes.

Neither of these approaches is perfect. But both suggest that resisting government pressure is possible for large tech companies. It requires accepting political friction and regulatory uncertainty. But it's not impossible or uniquely harmful to the business.

Apple's choices suggest not that resistance was impossible, but that the company didn't prioritize resistance. The values the company publicly espouses—privacy, autonomy, protection from surveillance—logically extend to protecting tools that help vulnerable communities avoid government enforcement action. The fact that Apple didn't protect those tools reveals that the company's values prioritize other considerations.

The Chilling Effect: Why ICEBlock Matters Beyond the App

When Apple removes a specific application, the immediate impact is straightforward—people can't download that app from the App Store. But the longer-term impact is more insidious. Removing tools creates a chilling effect on the developers who create them and the communities that use them.

Developers considering building civic accountability tools now know that Apple will remove them if government pressure arrives. That knowledge changes calculation about what's worth building. Why invest time and resources in tools that might be removed? The barrier to entry increases. The risk increases. Some developers won't even attempt it.

Users considering relying on these tools now know they might disappear without warning. They can't plan around tools they can't trust will remain available. That uncertainty reduces adoption. Communities planning around tools that might vanish are planning with less confidence.

This chilling effect extends beyond just ICEBlock. It signals to other developers and other communities that tools serving vulnerable populations are precarious. They exist at Apple's sufferance. If government pressure arrives, they disappear.

The effect is differential impact. Tools serving affluent populations, or tools aligned with government interests, face no comparable pressure. Waze thrives because it serves navigation interests that align with government transportation goals. iCloud encryption faces pressure but not removal because it serves consumer interests that tech companies prioritize. But tools specifically designed to help vulnerable communities protect themselves from government action—those are vulnerable to removal.

That differential impact is the real harm. It's not just the loss of one app. It's the message about which tools and which communities Apple actually prioritizes when values compete.

Apple's removal of ICEBlock contrasts with its allowance of Waze and similar apps, suggesting inconsistency in policy application regarding law enforcement tracking.

Reinstatement: What It Would Actually Mean

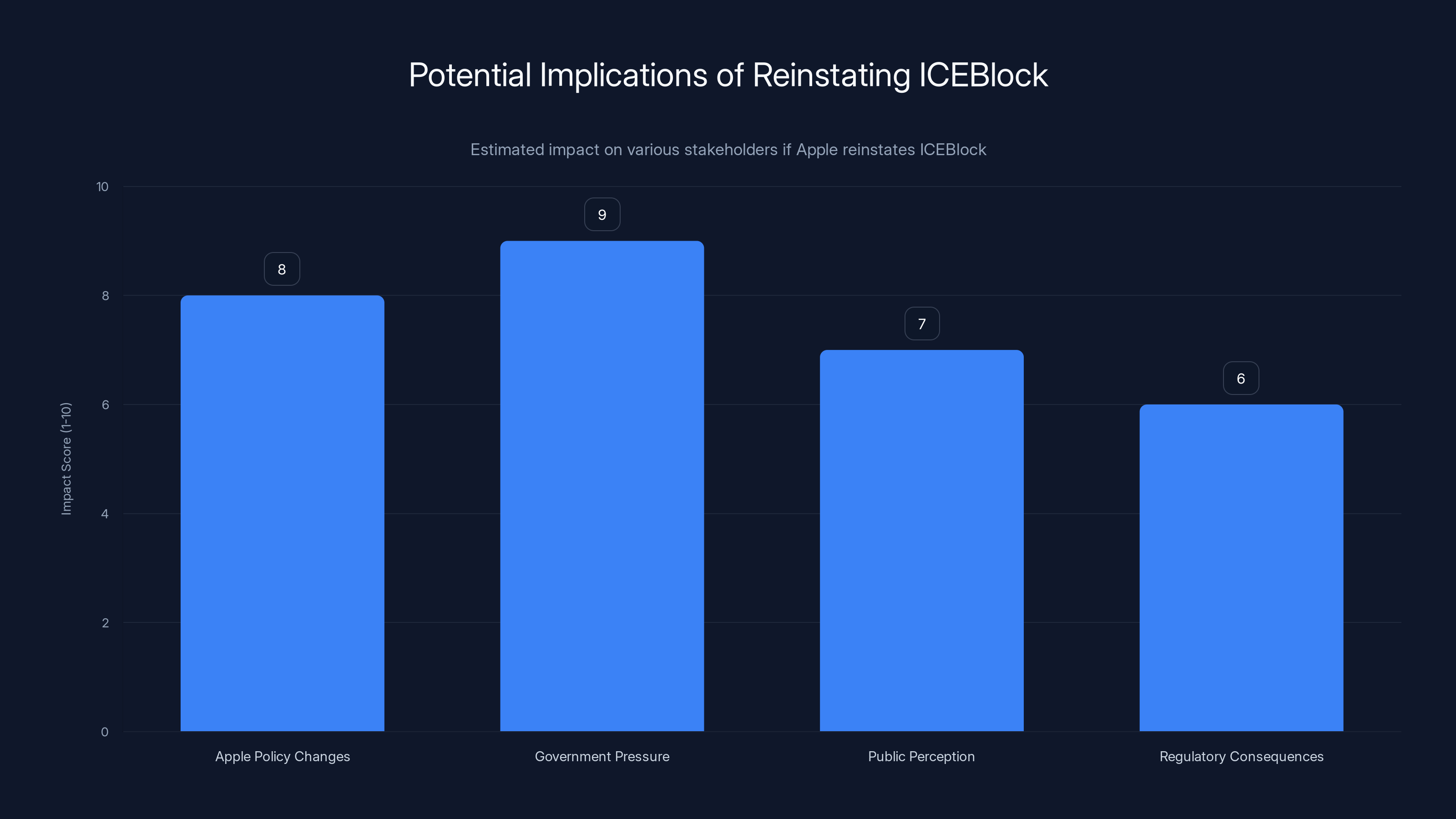

If Apple were to reinstate ICEBlock and similar apps, what would that actually entail? The practical requirements are straightforward, but the implications are significant.

First, Apple would need to formally state that apps documenting law enforcement activity don't violate App Store policies. The current policy language that allows removal based on "potential to harm law enforcement officers" would need revision or clarification. The revised policy would need to distinguish between tools that facilitate civic awareness and tools that facilitate harm.

Second, Apple would need to commit to reviewing government pressure requests through a transparent process. If a government agency requests removal of an app, the company would make the determination through clear criteria and communicate that determination publicly. Transparency itself is protective—it prevents secret pressure from operating effectively.

Third, the company would need to acknowledge the principle that tools serving civic accountability are protected the same way tools serving commercial interests are protected. If mapping apps can show police locations because they serve navigation interests, then dedicated tracking apps can serve civic accountability interests. The protection extends across purposes.

These requirements sound reasonable because they're rooted in consistency. Apply the same standards to apps regardless of whose interests they serve. Be transparent about government pressure. Protect tools based on function rather than ideology or political preference.

But implementing them would require Apple to accept political friction. Law enforcement would object. The Trump administration would object. There would be regulatory consequences in some jurisdictions. The company would face attacks for being anti-police or left-wing.

Those costs are real. Which is why Apple won't reinstate ICEBlock unless the calculation changes. That happens either when external pressure becomes sufficient that maintaining the ban costs more than lifting it, or when the company's leadership reorders values to prioritize civic accountability over political convenience.

The Intersection of Race and Visibility: Why Good's Death Changed the Calculation

One crucial detail deserves explicit examination: Renee Nicole Good was white. That detail shouldn't matter morally—the deaths of undocumented immigrants in ICE custody are equally tragic and demand equally serious response. But politically, it changed visibility.

For years, immigrant rights advocates have documented ICE violence. They've shared stories of people killed in custody, separated from families, deported to danger. Mainstream media rarely prioritized these stories. The deaths were distributed across networks of undocumented immigrants, causing profound trauma within those communities but not breaking through to broader political attention.

When ICE killed a documented white American citizen, the story couldn't be ignored. Mainstream journalists covered it. Political figures had to respond. The facts of ICE's violence suddenly became impossible to dismiss as fringe concerns.

This raises an uncomfortable question: Why did it take a white victim for ICE violence to become visible as a problem? The answer implicates not just law enforcement but media, political systems, and public attention itself. Stories about threats to marginalized communities don't break through the same way. That disparity in visibility has consequences.

Apple's behavior reflects this same disparity. When ICE violence primarily affected undocumented immigrants, the company didn't feel pressure to support tools protecting those communities. When ICE violence suddenly affected documented citizens with political voice, the pressure increased. But removing the tool happened during the first period, not the second.

This illuminates a deeper problem with Apple's approach. The company's values shouldn't depend on political visibility. Either civic accountability tools are valuable or they aren't. Either protection from government overreach matters or it doesn't. The answer shouldn't depend on whether the victims are marginalized or visible.

The fact that Good's death became visible created an opportunity for broader conversation about ICE accountability. But it also revealed the fragility of protections for communities that lack political voice. ICEBlock was removed in silence. Its removal mattered most to undocumented people who couldn't easily protest the decision. By the time mainstream attention arrived at ICE violence, the tool was already gone.

Reinstatement would partly correct this disparity, though not entirely. It would restore a tool that serves vulnerable communities. But it would do so only after the political calculation changed because a white victim was killed. That's better than never reinstating the tool. But it's also revealing about what moves corporate action.

Estimated data showing the potential impact of reinstating ICEBlock on Apple's policies, government relations, public perception, and regulatory consequences. The highest impact is expected from government pressure.

Technology's Role in Civic Accountability: Beyond Apps

ICEBlock's removal is part of a broader conversation about technology's role in holding government accountable. This conversation matters because technology has become a primary mechanism through which civic information flows.

In previous eras, civic accountability relied on investigative journalism, public records requests, and community organizing. Those mechanisms still exist and remain important. But technology has created new capabilities. Citizens with phones can document events and distribute them globally in minutes. Apps can aggregate citizen reports to create pattern visibility. Maps can show where government activity concentrates.

These technologies aren't without risk. Misidentification, false reports, and distorted framing can circulate. Documentation can sometimes endanger people or compromise investigations. But the solution isn't removal of the tools. It's better tools—tools with verification mechanisms, tools that distinguish between confirmed and unconfirmed reports, tools that provide context alongside data.

Instead, policy has tended toward removal. When technology enables civic accountability in ways that inconvenience powerful institutions, the response is often to ban the technology rather than improve it.

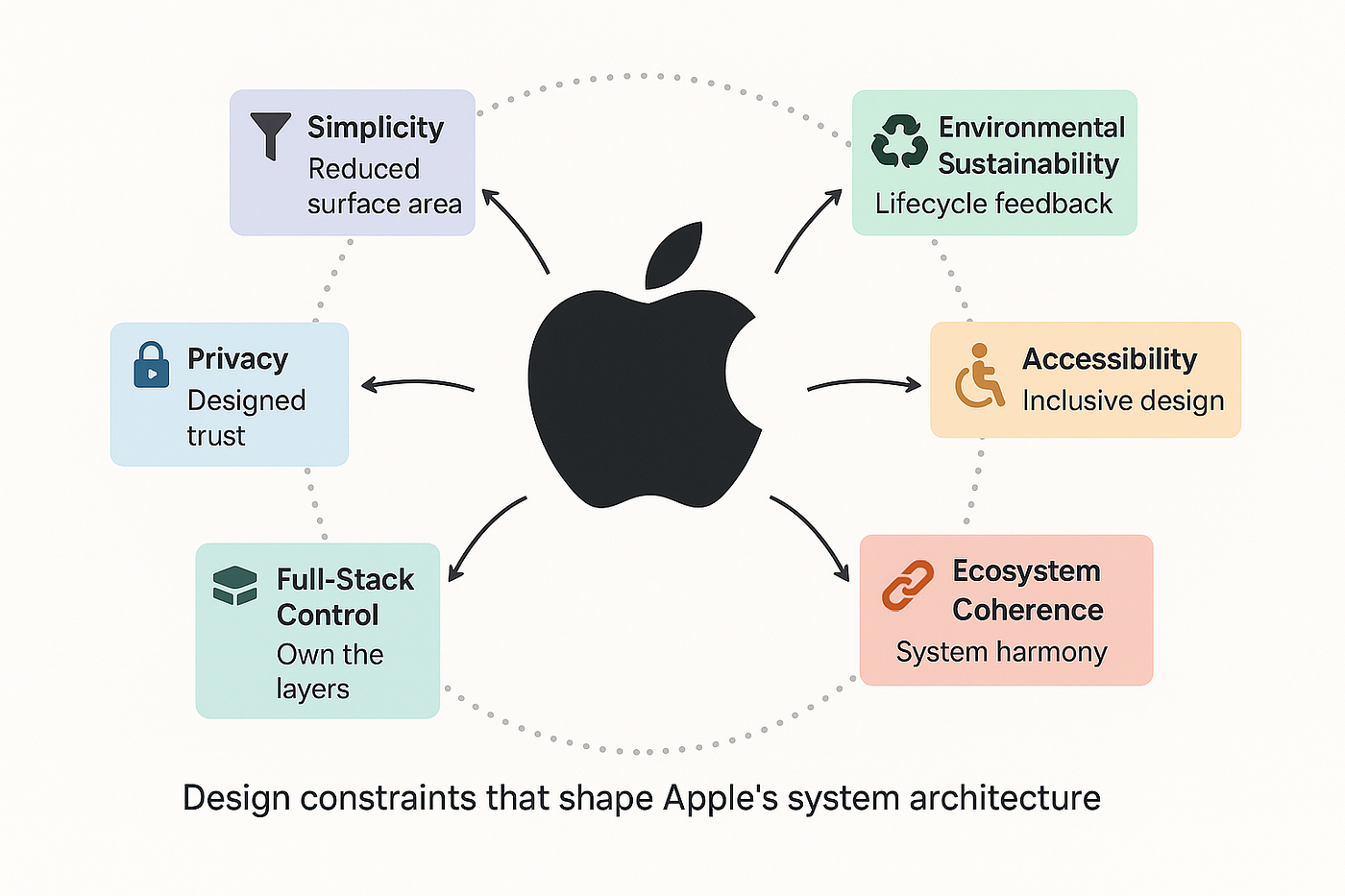

Apple's role here is particularly significant because the company controls the distribution mechanism. Developers can build whatever they want, but if Apple won't distribute it, reach is limited. That creates a powerful gatekeeping position. Apple uses that power to remove tools when political pressure arrives.

The implication is that the future of civic accountability technology depends on platform decisions. If Apple, Google, and Microsoft use their distribution power to remove accountability tools under pressure, then civic accountability becomes dependent on platforms' political calculation. That's an unstable foundation.

Sustaining civic accountability requires either changing platform behavior or developing alternatives to platform distribution. Both matter. Pressure on Apple to change behavior is legitimate and important. But developing platforms and distribution mechanisms less vulnerable to government pressure is equally important.

Regulatory Frameworks and Section 230: What Authority Actually Applies

Understanding Apple's legal obligations requires clarity about what authority actually applies to app store moderation decisions. This is complicated by overlapping regulatory frameworks and ambiguous legal standards.

The core question is whether Apple is a publisher or a platform. If the company is a publisher, it has editorial discretion—it can remove content based on whatever standards it chooses. If it's a platform, it has greater obligation to be neutral in moderation decisions. That distinction matters legally and practically.

In practice, Apple operates as both. For some purposes, the company claims publisher status and editorial control. For other purposes, particularly around legal liability, the company claims platform status. When convenient, the company emphasizes editorial discretion. When convenient, it emphasizes being merely a platform hosting third-party content.

Current law, particularly Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, generally allows platforms broad discretion in moderation decisions. Apple can remove apps for almost any reason, and courts have been reluctant to second-guess those decisions. That legal framework gives the company substantial power.

But legal permission doesn't equate to moral justification. Apple can remove ICEBlock. That's legally permissible. Whether it should remove the app is a separate question about corporate responsibility and civic consequences.

The regulatory environment is shifting. There's growing recognition that platform power over distribution and speech carries responsibility. Europe's Digital Services Act imposes transparency requirements on platform moderation. Potential future regulation in the US might require clearer moderation standards or appeal processes for removal decisions.

Those regulatory developments matter because they might constrain Apple's ability to remove apps under government pressure. If future law requires transparent, consistent application of removal policies, and bans discriminatory application of policies, then Apple loses the flexibility to maintain policies in ways optimized for political convenience.

Until then, the company's obligations are more limited than the civic consequences of its choices.

The Path Forward: How Pressure Creates Change

Apple won't reinstate ICEBlock because of abstract moral arguments. The company has had those arguments available and made different choices. Change happens when the cost of maintaining the ban exceeds the cost of lifting it.

That cost structure can change through several mechanisms. Public pressure campaigns that damage Apple's brand create cost. Boycotts that affect revenue create cost. Regulatory requirements that mandate reinstatement create cost. Employee activism that affects internal perception creates cost.

Historically, tech companies have reversed removal decisions under pressure. Twitter restored accounts after review processes became transparent and users understood the removal reasons. Google restored apps to Play Store after clarifying why they were removed and allowing appeals. Apple itself has reversed app removals after public criticism.

A campaign to reinstate ICEBlock would follow this pattern. It would need sustained visibility about what the app did and why it mattered. It would need articulation of why Apple's current position contradicts its stated values. It would need evidence that the removal harmed vulnerable communities. It would need public figures and organizations willing to call the position out.

That's work. It's not guaranteed to succeed. Apple might decide the reputational cost is acceptable. The company might calculate that maintaining the ban serves business interests better than lifting it.

But the possibility of change exists. Change happens when enough people decide the status quo is unacceptable and make that sentiment clear persistently.

The most effective arguments aren't about abstract principles. They're about concrete harms. They connect removed tools to real consequences. They show how the absence of ICEBlock affected people trying to protect themselves from enforcement action. They make visible the gap between Apple's stated values and actual behavior.

The Broader Principle: Corporate Responsibility Beyond Profit

ICEBlock's removal matter because it illustrates how corporate power intersects with civic goods. Apple isn't unique in this dynamic, but its position is significant because of the company's power and its brand identity.

When companies control distribution platforms, they wield power over information flows. When they use that power to remove tools under government pressure, they become participants in government control over information. That's not neutral. It's not merely commercial. It's actively constraining what information and tools are available to the public.

Corporate responsibility in this context means recognizing that power and using it in ways that support rather than constrain civic accountability. It means protecting tools that serve vulnerable communities, even when doing so creates friction with government. It means being transparent about pressure and resistant to it.

Apple could do this. The company has the resources, the legal protection, and the brand identity to support civic accountability tools. The company's failure to do so suggests that other considerations—profit optimization, government relationships, operational convenience—outweigh civic values when the two conflict.

That's the uncomfortable truth about corporate progressivism. It extends to positions that don't cost much and positions that align with commercial interests. When civic values require sacrifice or political friction, corporate progressivism often doesn't extend that far.

Changing that requires changing incentives. It requires making clear that the cost of ignoring civic accountability exceeds the cost of protecting it. It requires sustained pressure on companies to align behavior with stated values.

Apple's reinstatement of ICEBlock would be a meaningful signal. It would indicate that the company takes civic accountability seriously enough to accept political friction in its defense. It would restore tools that serve vulnerable communities. It would suggest that even powerful corporations can change when pressure is sufficient.

But it would also be incomplete. Real change requires broader shifts in how companies balance profit against civic goods. It requires recognition that corporate power carries responsibility to communities the company serves.

Why This Moment Matters: The Broader Conversation About Accountability

The January 2026 death of Renee Nicole Good created a moment of visibility. ICE violence—always present, always harmful, always documented by those experiencing it—suddenly became impossible for mainstream outlets to ignore.

That visibility creates opportunity. It creates space for conversations about ICE accountability that were previously confined to immigrant rights networks. It creates possibility for broader understanding of why tools like ICEBlock matter.

But visibility is temporary. The attention span of mainstream media is limited. The political window for action closes. Unless the moment is leveraged into sustained change, it will pass and the previous patterns will resume.

Apple's decision about ICEBlock will be made in this context. The company watches how the public responds to the removal. The company monitors whether the death creates sustained pressure for reinstatement or whether attention moves to other issues. Based on that calculation, the company decides whether change is necessary.

That's why sustained pressure matters. Individual outrage doesn't create change. Sustained, organized, visible demand for change creates the cost structure that makes compliance preferable to resistance.

If those demanding reinstatement can make clear that this is a principle the public cares about, and that the company's brand costs are real, then change becomes possible. If attention fades and focus shifts, then Apple's calculation won't favor reinstatement.

This is the practical reality of corporate power. Companies respond to incentives. The question is whether enough people will create the incentives to change Apple's position.

Conclusion: Aligning Values With Action

Apple presents itself as a company guided by values. Privacy. Security. Social responsibility. Civil rights. These are the principles the company invokes in keynotes and marketing. These are the standards against which customers evaluate the company.

But values are measured in action, not words. When government pressure arrived, Apple removed a tool designed to protect vulnerable communities from enforcement action. The company justified this with officer safety arguments that it doesn't consistently apply. The tool's removal proceeded quietly, without the public resistance that characterizes Apple's other government pressure situations.

That sequence reveals something important about corporate values. They're real, but they're flexible. They bend under pressure. They prioritize some interests over others. They're strongest when protecting things the company values commercially. They're weaker when protecting tools that serve vulnerable communities but create political friction.

Changing this requires change at two levels. At the immediate level, it requires sustained pressure on Apple to reinstate ICEBlock. That pressure is legitimate. The company removed a tool that mattered to people trying to protect themselves. Restoring it is the immediate justice.

At the broader level, it requires reckoning with how corporate values actually work. It requires recognizing that voluntarily stated corporate values are insufficient. It requires regulatory and market pressure to ensure that companies use their power in ways that serve civic goods alongside commercial interests.

Apple has the power to reinstate ICEBlock. The company has the legal basis, the business capacity, and the brand strength to support this decision. The question is whether the company chooses to. That choice will reveal more than any corporate statement about whether Apple's values extend to communities facing government overreach.

The moment to act is now. The attention is present. The case for reinstatement is clear. Apple should reverse its decision. The company should reinstate ICEBlock and similar tools. It should commit to resisting future government pressure to remove civic accountability applications. It should align corporate action with corporate values.

If Apple won't do this voluntarily, then sustained public pressure becomes necessary. Because at the end of this, what matters isn't Apple's stated values. What matters is whether tools to protect vulnerable communities from government overreach remain available to the people who need them. Everything else is just marketing.

FAQ

What is ICEBlock and how did it work?

ICEBlock was a mobile application that crowdsourced real-time reports of Immigration and Customs Enforcement activity. Users would report observed ICE operations in their neighborhoods, and the app would display these reports on a map accessible to other users. The mechanism was identical to traffic reporting apps like Waze—citizens contributing observations about public activity that gets aggregated to provide broader pattern awareness. The app enabled communities to share information about where enforcement activity was concentrated.

Why did Apple remove ICEBlock from the App Store?

Apple removed ICEBlock in October after pressure from the Trump administration. The company claimed that the app violated App Store policies against content that "could be used to harm law enforcement officers." However, this reasoning appears inconsistent with Apple's maintenance of other crowdsourced location reporting applications like Waze, which display police officer locations reported by users in identical fashion. The removal occurred without public transparency about the decision process or explicit government demands that became public.

What was the stated danger to law enforcement officers that Apple cited?

Apple's official position was that the crowdsourced location data could endanger ICE agents by making their positions known. However, this argument has significant weaknesses. ICE operates with multiple armed agents, vehicles marked with federal insignia, and radio communication. The operations reported through ICEBlock were already public and visible. No evidence emerged that crowdsourced location reporting created tactical danger beyond what already existed. The inconsistency with Apple's treatment of similar applications like Waze suggests the safety argument was rationalization rather than primary concern.

How does ICEBlock relate to broader ICE accountability issues?

ICEBlock was one tool among several designed to provide community protection from enforcement action. ICE had documented patterns of violence, including nine shooting incidents since September 2024 and 32 deaths in custody during 2025. More than a third of people arrested by ICE lack criminal records. For undocumented immigrants and mixed-status families, information about where enforcement was concentrated had protective value. ICEBlock represented one mechanism through which communities could share information about threats they faced.

What role did the Renee Nicole Good incident play in the ICEBlock debate?

In January 2026, ICE agent Jonathon Ross killed Renee Nicole Good, a white American citizen and mother. The incident received mainstream media attention in ways previous ICE violence hadn't, partly because the victim was documented and white. The death illustrated the very dangers that tools like ICEBlock were designed to help people avoid. The timing—less than three months after the app's removal—raised questions about whether restoration of the tool might have changed circumstances. The incident created visibility for broader conversations about ICE accountability and the importance of community information sharing.

How does Apple's ICEBlock removal compare to other companies' approaches to civic accountability tools?

Other major tech companies have made different choices about similar tools. Twitter explicitly committed to maintaining tools and features used for documenting law enforcement activity, resisting police department pressure to remove them. Google has declined law enforcement requests to remove police station locations from maps. These decisions involved accepting regulatory friction and criticism from law enforcement, but both companies determined that civic value outweighed those costs. Apple's decision to remove ICEBlock under government pressure contrasts with these approaches, suggesting different priorities or different tolerance for political friction.

What would reinstatement of ICEBlock actually require from Apple?

Reinstatement would require Apple to formally revise or clarify App Store policies to permit applications documenting law enforcement activity. The company would need to distinguish between tools that facilitate civic awareness and tools that facilitate harm. Apple would benefit from establishing transparent review processes for government removal requests, making clear what criteria trigger removal and communicating decisions publicly. Ultimately, reinstatement would signal that Apple considers civic accountability tools worthy of protection comparable to commercially oriented tools—a decision that would require accepting political friction with law enforcement.

Why does the visibility of the victim matter in discussions about ICEBlock and ICE accountability?

Community networks have documented ICE violence for years, but mainstream attention was limited. When a white American citizen was killed by ICE, the incident broke through to broader media coverage. This disparity reveals problems with how visibility operates in the broader accountability system. It shouldn't require a documented citizen victim for ICE violence to be taken seriously. Yet politically, victim identity affects resource allocation, attention, and pressure on companies. Recognizing this disparity is important for understanding why tools protecting vulnerable but less visible communities can be removed without immediate backlash.

What is the "chilling effect" that ICEBlock removal creates?

When Apple removes one civic accountability application under government pressure, it signals to developers and communities that such tools are precarious. Developers considering building similar applications face increased uncertainty about whether their work will be distributed or removed. Communities considering relying on such tools face uncertainty about whether tools will remain available. This uncertainty—independent of actual prohibition—discourages development and reliance on tools. Over time, the chilling effect reduces the ecosystem of civic accountability applications available to communities.

How does corporate responsibility factor into platform decisions about civic tools?

Platforms like Apple control distribution channels that billions of people use. That power carries responsibility to consider not just corporate interests but broader civic consequences. When platforms remove tools under government pressure, they become participants in constraining what information and tools are available to the public. Corporate responsibility in this context means recognizing that power and using it in ways that support rather than constrain civic accountability. It means being transparent about pressure and resistant to it when civic goods are at stake. Apple's current position suggests that other considerations outweigh civic responsibility when the two conflict.

What would sustained pressure to reinstate ICEBlock need to accomplish?

Change in corporate policy typically requires that the cost of maintaining the current position exceeds the cost of change. Sustained pressure campaigns need to make visible what the removed tool did and why it mattered. They need to articulate how Apple's position contradicts stated values. They need evidence of harm from the removal. They need public figures and organizations willing to maintain focus. They need to make clear that the company's brand and business interests suffer from the removal. Without these elements, company calculations don't change and policy doesn't shift. With them, reinstatement becomes possible.

Key Takeaways

- Apple removed ICEBlock under government pressure despite claiming officer safety concerns it doesn't apply consistently to apps like Waze

- ICE documented nine shooting incidents and 32 deaths in custody in 2025, making tools that help communities avoid enforcement activity genuinely protective

- The death of Renee Nicole Good by an ICE agent illustrates why community information sharing matters and how removing such tools removes protection

- Apple's removal of ICEBlock reveals that corporate progressive values are selective—strong when protecting commercial interests, weaker when protecting vulnerable communities

- Reinstatement requires sustained public pressure creating sufficient reputational and financial cost to outweigh Apple's preference for political convenience

Related Articles

- Spotify Ends ICE Recruitment Ads: What Changed & Why [2025]

- Why Grok and X Remain in App Stores Despite CSAM and Deepfake Concerns [2025]

- US Withdraws From Internet Freedom Bodies: What It Means [2025]

- Brigitte Macron Cyberbullying Case: What the Paris Court Verdict Means [2025]

- Grok Deepfake Crisis: Global Investigation & AI Safeguard Failure [2025]

- AI Accountability Theater: Why Grok's 'Apology' Doesn't Mean What We Think [2025]

![Apple's ICEBlock Ban: Why Tech Companies Must Defend Civic Accountability [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/apple-s-iceblock-ban-why-tech-companies-must-defend-civic-ac/image-1-1767998235844.jpg)