BBC's Lord of the Flies Miniseries: Complete Guide to the 2026 Adaptation [2026]

Introduction: When Civilization Crumbles

There's something profoundly unsettling about watching order collapse. Not the dramatic, explosive kind with explosions and dramatic music. The quiet kind. The kind where reasonable people, trapped together without rules, slowly realize that the rules were the only thing keeping them reasonable.

This is the core of William Golding's "Lord of the Flies." Published in 1954, the novel became a cultural phenomenon not because it was the first to explore human nature, but because it did so with a clarity that made readers deeply uncomfortable. It wasn't just about survival. It was about what happens when survival instincts override civilization itself.

Now, in February 2026, the BBC is bringing this dark exploration back to television. And unlike previous film adaptations, this new miniseries is getting the space and time that Golding's novel deserves. This isn't a condensed film trying to cram 200+ pages into two hours. This is a series that can breathe, develop characters, and slowly build the psychological pressure that makes the descent into savagery feel inevitable rather than sudden.

The BBC has already released the first trailer, and it's worth paying attention to. The network has the Golding family's blessing, access to substantial production resources, and a cast of young actors (many without previous acting experience) who bring authenticity to their roles. The early footage suggests this adaptation understands what made the novel matter: it's not really about the island. It's about what the island reveals about us.

In this guide, we'll explore everything you need to know about the BBC's adaptation. We'll break down the source material, examine what makes this version different from previous adaptations, analyze the cast, and consider why Golding's 70-year-old novel still feels relevant in 2026. We'll also look at the broader context of island survival stories in modern media and how this miniseries fits into that landscape.

If you've never read "Lord of the Flies," this guide will give you the foundation you need to understand what's happening on screen. If you have read it, we'll explore how the BBC's approach differs from the book and what those changes might mean for the story's impact.

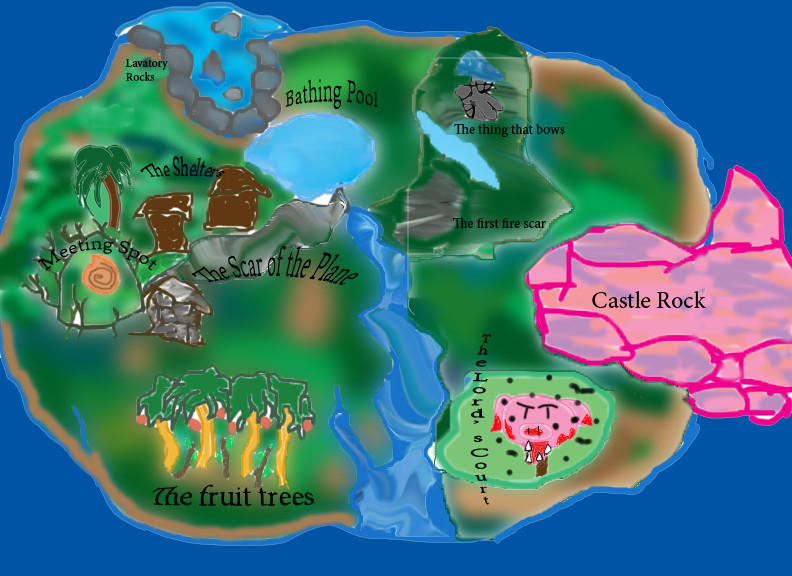

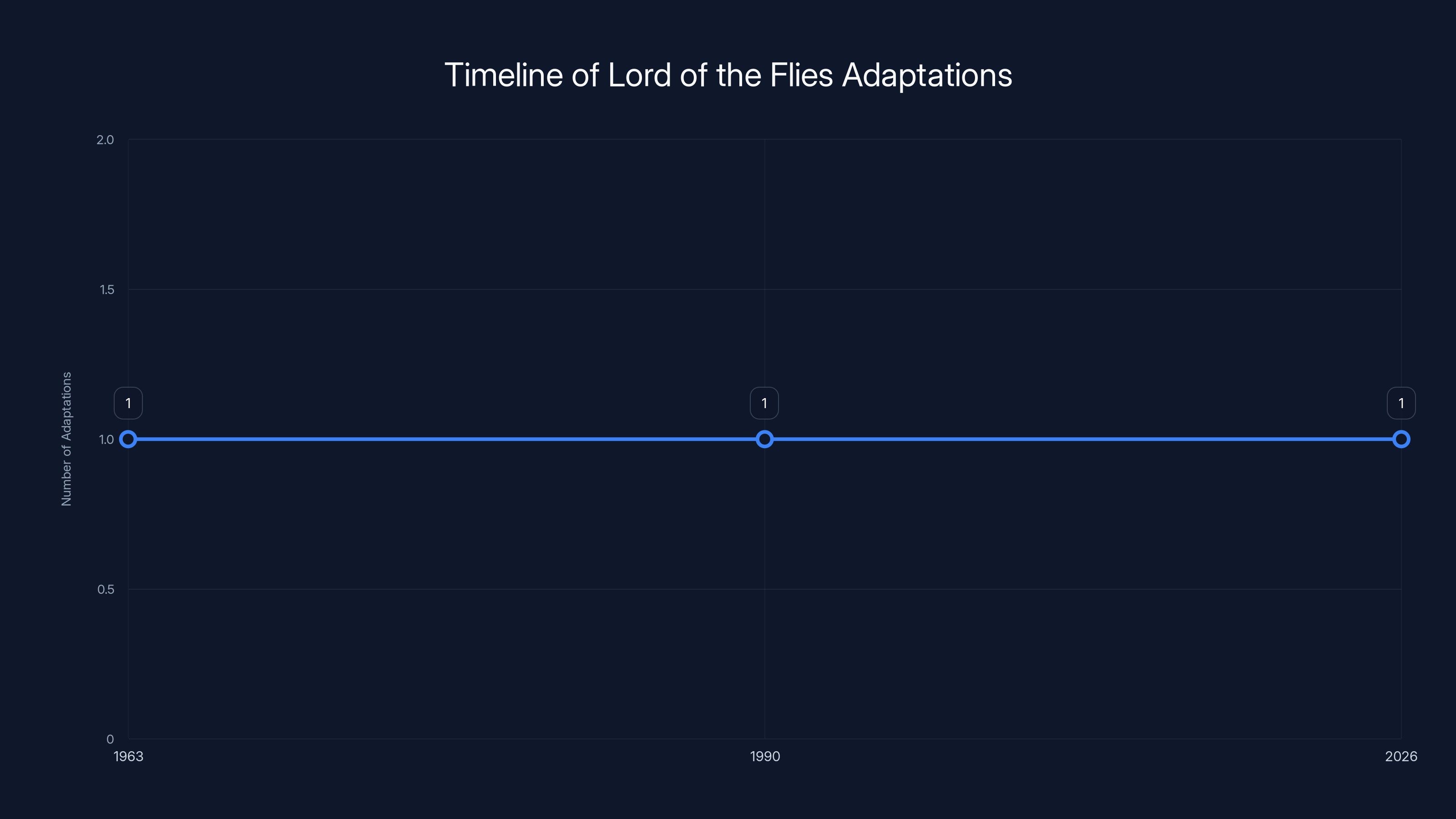

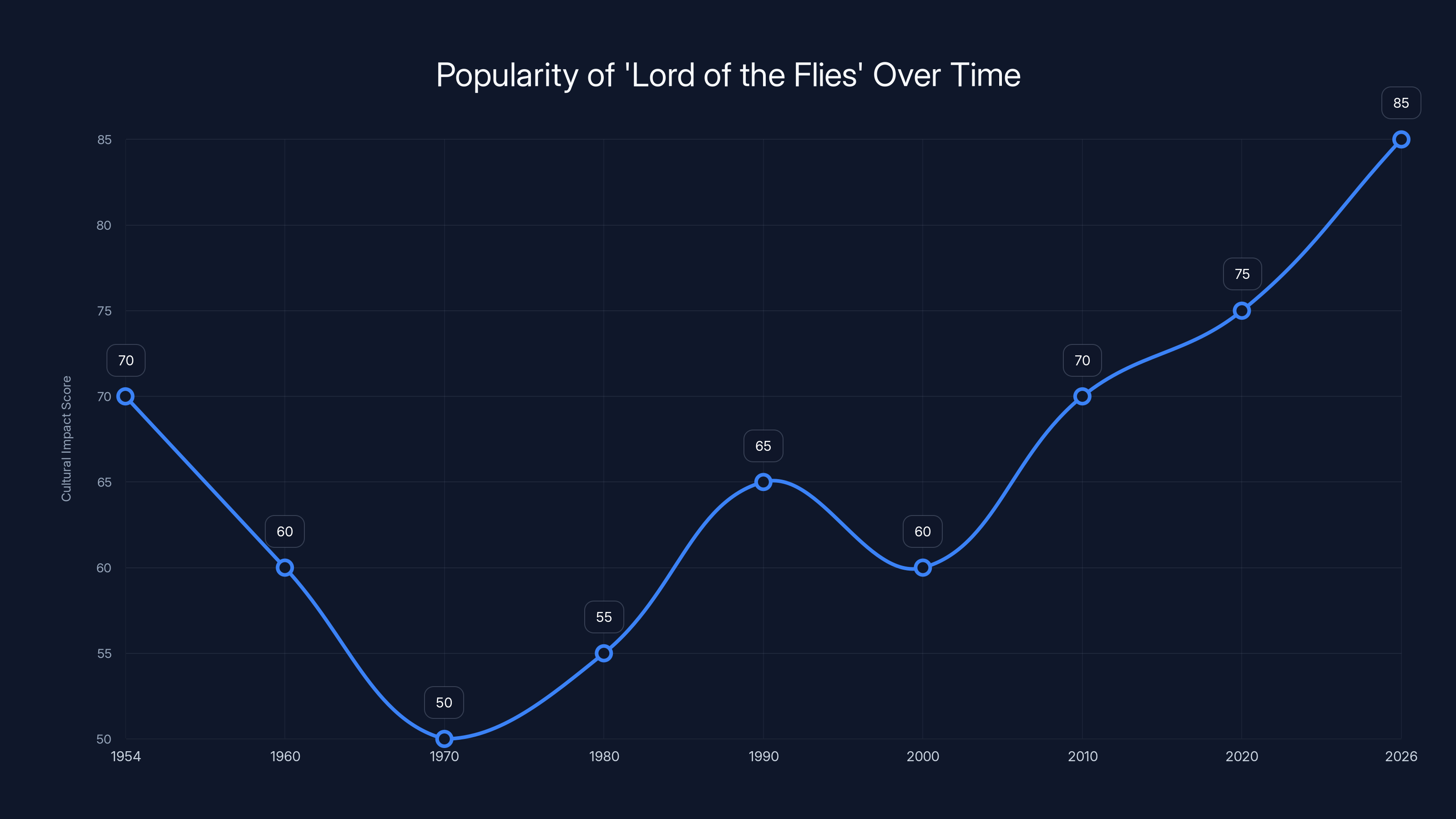

The timeline shows key adaptations of 'Lord of the Flies', highlighting the upcoming 2026 BBC miniseries. Estimated data.

TL; DR

- BBC One Release: The miniseries premieres February 8, 2026, with a fresh adaptation of Golding's classic novel

- Strong Source Material: The BBC has Golding family support and plans to stay faithful to the 1954 novel's core themes

- Stellar Cast: Winston Sawyers leads as Ralph, with strong supporting performances from Lox Pratt as Jack and David Mc Kenna as Piggy

- Island Survival Theme: The story explores how civilization collapses when young boys are stranded without authority or structure

- Cultural Relevance: The novel's exploration of tribalism, hierarchy, and violence remains strikingly relevant to modern audiences

The Source Material: Understanding Golding's Novel

The 1954 Context: A Response to Optimism

William Golding didn't write "Lord of the Flies" in a vacuum. He wrote it in the early 1950s, just as Europe was beginning to recover from World War II. The war had ended only nine years before publication. The scars were still fresh. The revelations about concentration camps, about systematic genocide, about the capacity for evil that civilized nations possessed—these were not distant historical facts. They were recent memory.

Golding himself had fought in World War II. He understood firsthand what humans were capable of under pressure. He'd seen educated, cultured people participate in violence that should have been unthinkable. This experience shaped everything he wrote.

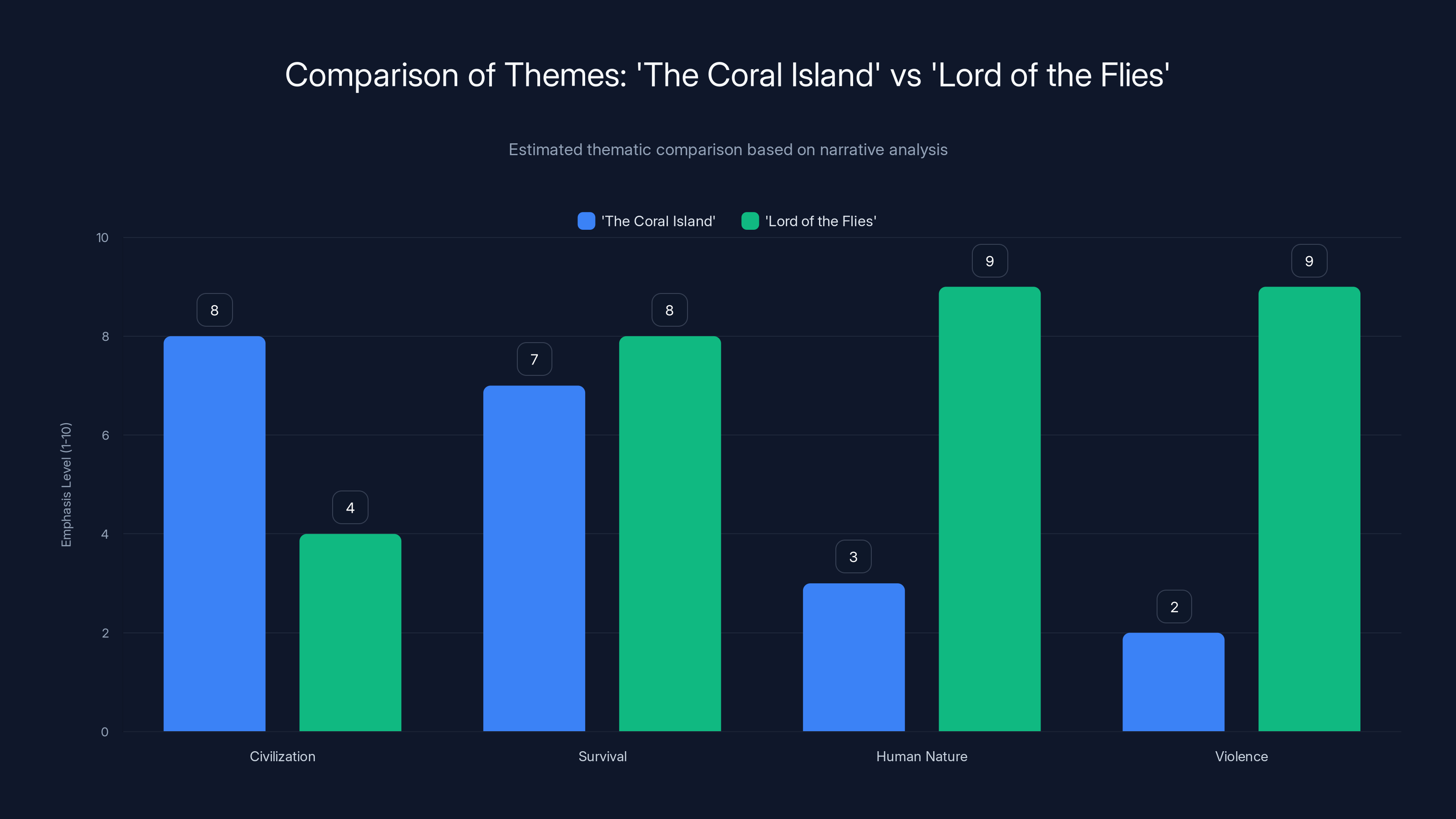

But there was another context that's crucial to understanding the novel. There was a popular children's book called "The Coral Island," published in 1857 by R. M. Ballantyne. It told the story of three British boys stranded on an island. In that novel, the boys' British civilization, their Christian values, and their natural superiority as Europeans allowed them to not just survive but to civilize the island itself. They brought order, Christianity, and proper British values to a place that supposedly lacked them.

Golding read this and found it deeply troubling. Not because it was false per se, but because it was incomplete. It ignored something fundamental about human nature: the capacity to revert to tribalism, to violence, to savagery when social structures vanish. Golding wanted to write the opposite story. He wanted to show what would actually happen if you put a group of young British boys on an island with no authority, no adults, and no external structures to maintain civilization.

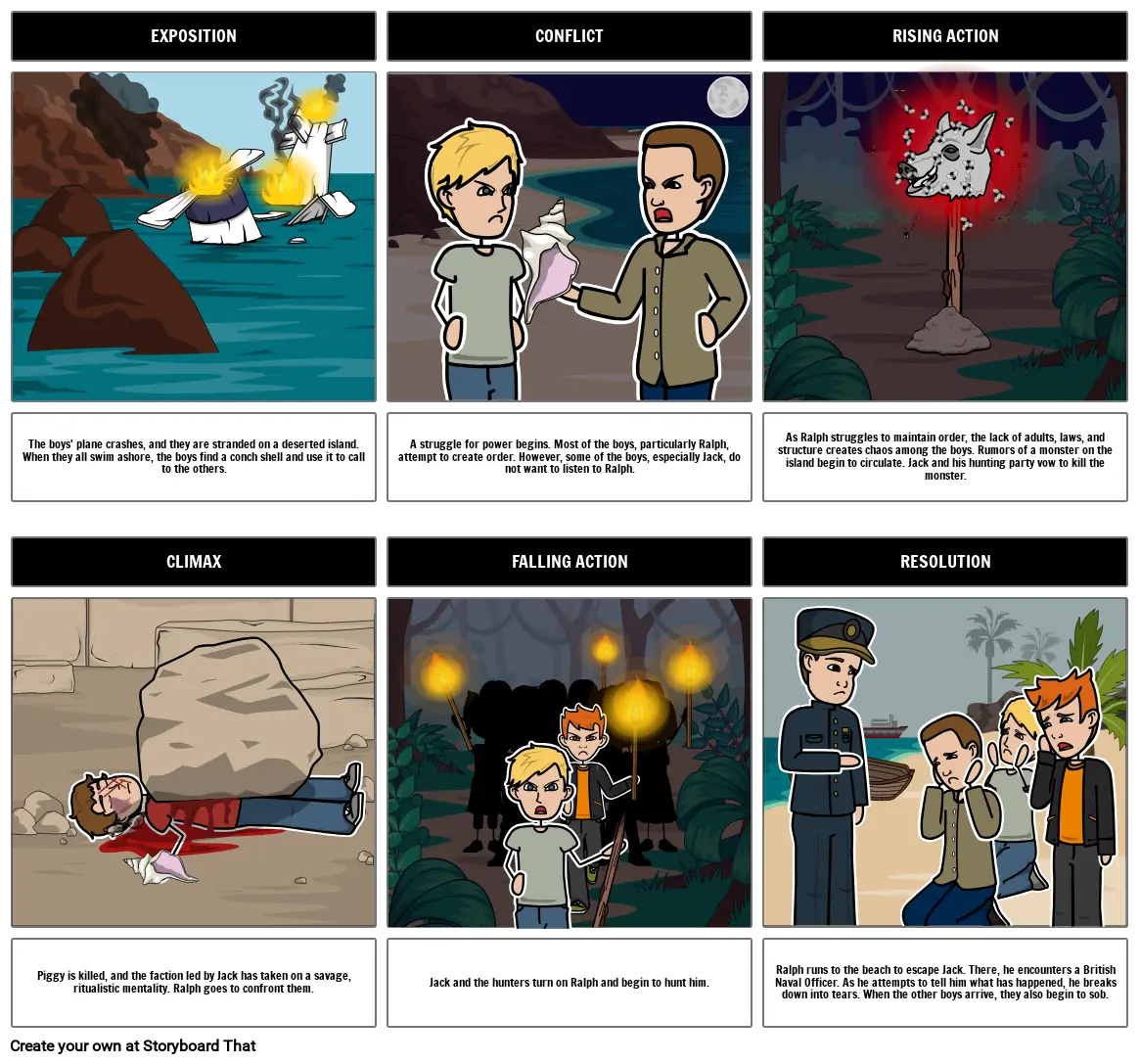

The Plot: A Slow Descent

The story begins in media res. An airplane carrying British boys evacuated from war-torn England crashes on an uninhabited island. The immediate crisis—survival—brings them together. They need water, food, and shelter. They need rescue.

Ralph, a fair-haired boy around twelve years old, discovers a conch shell. He uses it as a horn, and its sound gathers the scattered boys. The conch becomes a symbol of authority and order. Whoever holds the conch has the right to speak without interruption. It's a democratic tool, a way of ensuring everyone has a voice.

Initially, this works. Ralph proposes reasonable survival strategies. They'll build shelters. They'll maintain a signal fire on the island's peak to attract passing ships. They'll establish rules. Piggy, an overweight, intellectual boy with asthma and glasses, becomes Ralph's advisor. The glasses themselves become crucial—their lenses can focus sunlight to start fires.

But there's Jack. Jack is charismatic, competitive, and drawn to power. He leads the choir boys, now transformed into hunters. Hunting seems exciting, more appealing than building shelters or maintaining a boring fire. Jack's status grows as he brings back meat. The boys begin to see hunting as glamorous, honorable even.

The split is inevitable. Jack breaks away, forming his own tribe. They abandon the signal fire to hunt. They paint their faces and perform rituals around the kills. They're no longer constrained by Ralph's rules or the agreement to maintain rescue efforts.

Then one of the younger boys, a "littlun," mentions a beast. The beast becomes real in the boys' minds through fear and imagination. It becomes a tool for control, a way for Jack's tribe to bind its members through shared terror and shared hunts.

The novel escalates into violence. A boy named Simon, a quiet intellectual who might have been able to bridge the divide, is killed in a frenzy. Not by Jack necessarily, but by the mob. Piggy, calling for reason and rules, is killed, and the conch is shattered simultaneously. The island becomes a war zone, with Ralph hunted like prey.

The rescue comes almost by accident. A British naval officer, conducting a routine patrol, lands on the island and finds the boys. The officer's arrival breaks the spell. Civilization returns instantly. Ralph, seeing rescue, breaks down crying. The narrator observes that the officer can't understand why these British boys are in such a state. He doesn't realize he's looking at a microcosm of what humans are capable of when socialization is removed.

What Made It Matter: Themes That Persist

The novel worked because it tapped into something primal about how humans organize themselves. It showed how quickly hierarchy emerges, how appeal to tribal identity can override individual morality, and how fear can be weaponized to maintain power.

But here's what's important: Golding wasn't claiming to have discovered some deep truth about human nature. He was writing fiction, not sociology. The book wasn't meant to be a scientific study. It was an exploration of what could happen, a dark "what if" that used plausible characters and situations to explore philosophical territory.

Yet the novel's influence became enormous. It was adopted into school curricula. It became shorthand for "what happens without rules." For decades, it was read as a parable about human nature itself, as if Golding had proven something about how people naturally behave.

Interestingly, in 1965, real evidence emerged that contradicted the novel's pessimism. Six Tongan boys actually were stranded on an island. Unlike Golding's fictional boys, they organized cooperatively, established rules, maintained discipline, and supported each other psychologically. They were rescued after over a year on the island, and they'd thrived, not descended into savagery. This real event suggested that humans might be more cooperative than Golding's fiction implied.

But that doesn't make the novel less valuable. Fiction doesn't have to be scientifically accurate to explore genuine psychological truths. "Lord of the Flies" still asks important questions about how quickly we abandon cooperativeness under pressure, how easily we resort to tribalism, and how thin the veneer of civilization actually is.

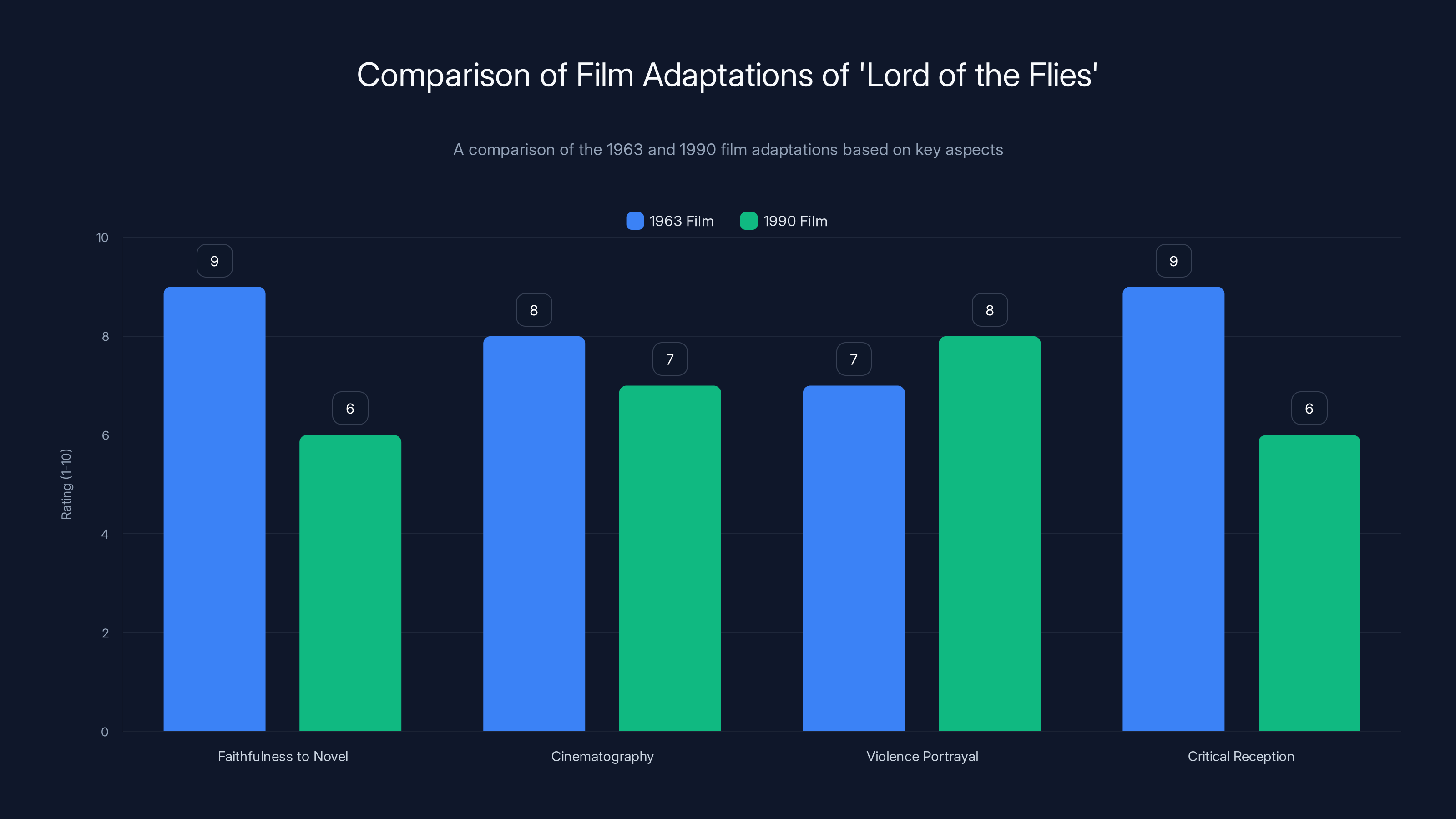

The 1963 film adaptation is noted for its faithfulness to the novel and critical reception, while the 1990 version is more action-oriented with graphic violence. (Estimated data)

Previous Adaptations: What's Come Before

The 1963 Film: Black and White Authenticity

The first adaptation came just nine years after the novel's publication. Peter Brook's 1963 film was shot in black and white on an actual island in the Caribbean (Vieques, Puerto Rico). Brook made a deliberate choice to cast actual schoolboys rather than professional young actors. The result was a film that captured the physical reality of the novel in remarkable detail.

What made the 1963 version notable was its commitment to the source material's darkness. There was no softening, no Hollywood redemption arc. The descent was methodical and bleak. The violence, when it came, had weight because it felt unexpected rather than inevitable. The film trusted the material and didn't try to punch up the pacing or add dramatic flourishes.

The black and white cinematography became iconic. There's something about black and white that makes violence feel more serious, less sensational. It strips away the aestheticizing that color cinematography sometimes brings. When Piggy falls from the cliff, when the boys hunt Simon through the darkness, the lack of color makes it all feel more primitive and more real.

Critics at the time praised the film's faithfulness to the novel. Golding himself approved of it. It remains the most respected film adaptation, though it's not as well-known today as the 1990 version.

The 1990 Film: Action Adventure Tone

Thirty years later, Harry Hook directed a color remake for theatrical release. This version updated the setting—the boys are evacuees from a military conflict in a fictional Latin American country rather than World War II England. It cast more conventional young actors and shot in color on an island in Jamaica.

The 1990 version is more visually dramatic, more action-oriented. The hunting scenes are more visceral. The violence is more graphic. It's also more dramatically structured in conventional film terms—there are clear protagonists and antagonists, character arcs that resolve, and a sense of escalating stakes that builds toward climax.

However, this approach has a cost. By emphasizing action and drama, the film sometimes loses the psychological dimension that makes the novel matter. The novel's power comes partly from its interiority—the way it gets into the boys' heads, showing how they rationalize their choices, how fear shapes thinking, how tribalism feels from the inside. A film can suggest these things but can't access them as directly.

The 1990 film is entertaining. It's a competent adaptation. But it's also more conventional, less willing to sit with the uncomfortable philosophical implications of the material.

Why the BBC Miniseries Is Different

A miniseries has advantages that neither film version had. It has time. Film adaptations of novels have to cut material ruthlessly. A miniseries can expand, can take detours, can spend time with characters in ways films cannot. This is crucial for "Lord of the Flies" because much of what makes the novel work happens in the space between action—the conversations, the rationalizations, the gradual shifts in perception.

The BBC's access to the Golding family also matters. It suggests the adaptation has been vetted by people who understand the author's intentions. The family's blessing doesn't guarantee quality, but it does suggest the production understands what the material is supposed to do.

The choice to cast many non-professional young actors, as suggested by the trailer and production notes, echoes the 1963 film's approach. This can create a kind of authenticity that professional child actors sometimes can't achieve. There's a realness to their reactions, their physicality, their relationships that scripted performance sometimes smooths over.

The Cast: Who's Leading This Descent

Winston Sawyers as Ralph: The Boy Who Wants to Lead

Winston Sawyers carries the weight of the miniseries as Ralph. Ralph is the hardest character to play because he's the character through whose perspective we often experience the story, yet he's not the most dramatically interesting. He's reasonable, conscientious, and trying to do the right thing. In less skilled hands, this could make him boring.

But Ralph's arc is genuinely tragic. He starts with the best intentions. He wants to organize, to establish order, to ensure rescue. He listens to Piggy's intellectual arguments about why maintaining the signal fire matters. He genuinely believes in the system he's created—the conch, the assemblies, the rules.

Yet Ralph fails. Not because he's incompetent, but because he underestimates how powerfully tribal instincts and the appeal of immediate gratification work on people. Hunting brings excitement and status in ways that building shelters doesn't. The tribe forming around Jack offers belonging and identity in ways that Ralph's democratic assemblies can't match.

Sawyers' interpretation will likely emphasize Ralph's growing awareness of his own powerlessness. The early scenes probably show confidence and enthusiasm. As the miniseries progresses, that confidence should erode. By the end, Ralph should seem like a different person—hunted, desperate, understanding that the system he believed in isn't sufficient to protect him.

Lox Pratt as Jack: The Seductive Appeal of Power

Jack is often read as simply the villain of the story. But this misses something crucial about Jack's appeal. Jack isn't evil in the sense of being motivationally malicious. Jack is charismatic. He offers excitement, status, and identity to the boys who follow him. He makes hunting seem honorable and important. He creates rituals that bind his tribe together through shared experience and shared taboos.

This is what makes Jack dangerous. He's not the creepy antagonist lurking in shadows. He's the popular kid who offers something the other leader doesn't. Jack offers immediate reward (meat, excitement, status) while Ralph offers delayed reward (rescue, which might come tomorrow or might come never).

Lox Pratt will need to play Jack as genuinely compelling, not as obviously evil. The miniseries will work best if the audience can understand why boys follow Jack, why his way of doing things seems better and more real than Ralph's. The tragedy is that reasonable people—and these are reasonable boys—can be drawn into tribalism and violence through mechanisms that actually make psychological sense.

David Mc Kenna as Piggy: The Intellectual Who Knows Better

Piggy is the character who understands what's happening most clearly. He sees the problems with Jack's tribe. He argues for maintaining rules and order. He represents the intellectual argument for civilization.

But Piggy is also physically weak, socially awkward, and unable to hunt. He's dependent on his glasses to start fires. He has asthma. Within the hierarchy that quickly forms on the island, Piggy ranks low. His intellectual arguments don't matter to boys who can kill and provide meat.

This is the miniseries' core tragedy. The character who sees most clearly is the one least able to influence events. His death—along with the simultaneous shattering of the conch—represents the final collapse of the argument for reasoned civilization. After Piggy dies, there's no intellectual counterweight to Jack's tribal power.

Mc Kenna's interpretation should emphasize Piggy's growing awareness that nobody is listening. He knows what's wrong. He can articulate why the signal fire matters and why maintaining rules matters. But his knowledge is impotent in the face of tribal power and physical dominance.

Supporting Cast: Creating a World of Stranded Boys

The production cast over 20 young boys to play the "big 'uns" and "little 'uns." These are crucial roles that don't have names in some cases but have enormous impact on the story's atmosphere. The littluns (the younger boys) represent vulnerability, dependence, and the need for protection. Their fear drives much of the narrative, especially regarding the "beast."

The cast includes Ike Talbot as Simon, a quieter, more introspective boy who might have provided a moral check on the tribe's worst impulses. Simon's death is perhaps the pivotal violence in the novel—it's not calculated or driven by Jack's explicit orders, but rather a mob frenzy. This requires careful portrayal to show how normal boys, caught up in group dynamics and fear, become capable of violence they wouldn't commit individually.

Thomas Connor as Roger represents the boy who has no moral qualms about violence. Roger doesn't need the excuse of the beast or tribal war. He seems to genuinely enjoy hurting others. His character arc, subtle in the novel but important, shows how easily individual personality differences become magnified in contexts that reward violence.

The Flemyng brothers (Noah Flemyng and Cassius Flemyng) play Sam and Eric, the twins who are loyal to Ralph but also get drawn into Jack's tribe. Their dual loyalty and eventual switch show how individual identity can be absorbed into tribal identity.

Production Details: How the BBC Is Approaching This

Working with the Golding Family

The fact that the BBC has the Golding family's blessing is significant. It suggests the production understands what the novel is trying to do and isn't planning to fundamentally alter the source material for contemporary sensibilities. Some adaptations of older works try to update the themes or soften the darker elements. The family's involvement suggests this version will maintain Golding's moral ambiguity and philosophical darkness.

William Golding died in 1993, so the family involved are likely his children or estate representatives. They're stewards of his legacy, people who presumably understand the novel's intent and want it represented faithfully.

This doesn't mean the miniseries is a direct transcription of the novel into scripts. Adaptation requires changes. The internal monologues and philosophical reflections of the novel need to be expressed through dialogue and visual storytelling. But the family's blessing suggests these changes will be in service of the novel's themes rather than contrary to them.

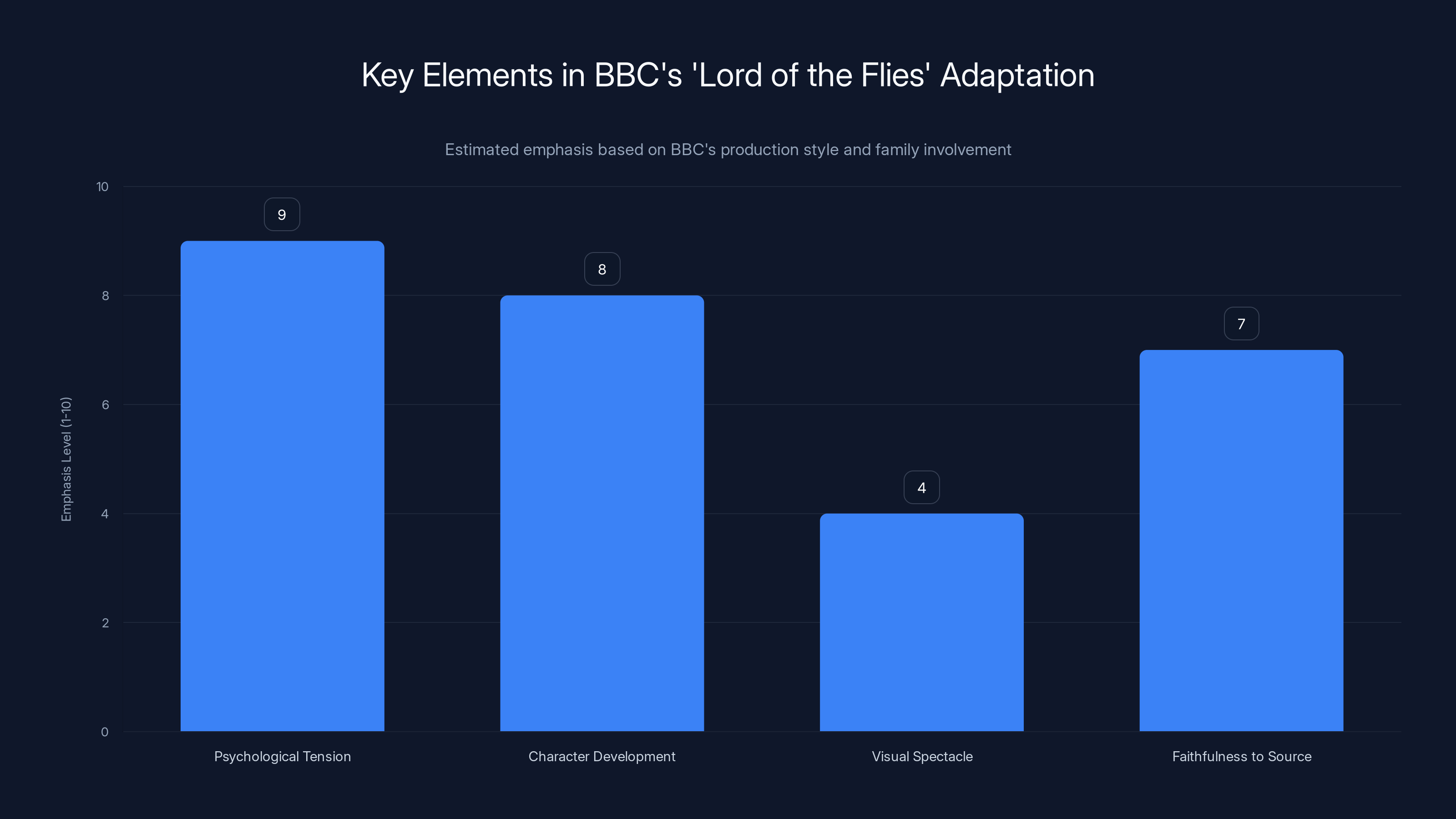

BBC One Platform: What This Means for the Production

BBC One is the UK's primary public broadcasting channel. A miniseries on BBC One has certain constraints and certain advantages. The constraints include content guidelines about how violence can be depicted. The advantages include institutional support, production resources, and access to BBC's substantial technical infrastructure.

BBC dramas have a particular aesthetic—often they favor psychological tension over special effects, character development over plot mechanics. The BBC's "I, Claudius," its "Sherlock" series, and other major productions show an institutional preference for strong writing, strong acting, and clear storytelling over visual spectacle.

This suggests the BBC's "Lord of the Flies" will likely emphasize the psychological descent more than previous film versions, and will probably have strong dialogue and character work rather than extensive action sequences.

Release Schedule: February 8, 2026

The February release date positions the miniseries in an interesting time of year. February typically sees less commercial competition than fall or spring, but it's also not a summer blockbuster season. This suggests the BBC believes the material is strong enough to stand on its own without the marketing weight that comes with major seasonal releases.

The choice to release on BBC One means UK audiences will see it first. International distribution through services like Brit Box or other platforms will likely follow, but the primary audience during initial release will be the UK viewing public.

BBC's adaptation of 'Lord of the Flies' is likely to emphasize psychological tension and character development, aligning with its production style and the Golding family's involvement. Estimated data.

Thematic Analysis: Why This Story Persists

Tribalism as a Natural Human Tendency

"Lord of the Flies" explores how quickly people, especially young people without established social identities, adopt tribal affiliations. The split between Ralph's group and Jack's group isn't the result of fundamental moral differences. Both groups want the same things: survival, status, and belonging.

But the path to those goals diverges. Jack's path is more immediately rewarding. Hunting provides meat, which you can eat today. Maintaining a signal fire provides hope for rescue, which might come never. From a pure psychological perspective, Jack's way makes more sense.

The novel suggests that civilization—the systems, rules, and agreements that allow cooperation—requires individuals to choose delayed gratification, to trust that the system will work, and to suppress immediate tribal impulses. This is difficult even for adults in established societies. For boys with no prior investment in any particular system, it's nearly impossible.

Fear as a Tool of Control

The "beast" in the novel is perhaps the most important element, even though the beast probably doesn't exist. The boys create the beast through their own fear and imagination. Then Jack weaponizes the beast, using it as a tool to maintain control over his tribe.

People are easier to control when they're afraid. A distributed fear—this vague "beast" that could be anywhere—is more effective than explicit threats. Jack never needs to explicitly threaten to punish disobedience if the boys are afraid of the beast waiting outside his tribe's protection.

The miniseries will likely show how the beast grows in the boys' minds, how each strange sound or unexplained event becomes evidence of the beast's existence. This psychological mechanism—how fear shapes perception—is one of the novel's most relevant explorations for modern audiences.

Violence as a Performance

The hunting rituals in the novel are crucial. When Jack's tribe hunts, it's not just about getting food. It's about performing dominance, demonstrating competence, and binding the tribe through shared transgression. The violence becomes ritualized, almost ceremonial.

This suggests something important: violence isn't just a means to an end for Jack's tribe. It becomes an end in itself, a way of establishing and maintaining identity and belonging. The tribe isn't hunting because they're starving. They're hunting because hunting proves they're part of the tribe.

The miniseries will need to show this psychological dimension clearly. The hunting scenes aren't just about the hunt. They're about the boys' faces as they participate, their awareness of the tribe around them, and the way the ritual binds them together.

Comparative Context: Island Stories in Modern Media

Yellowjackets: Survival with Trauma

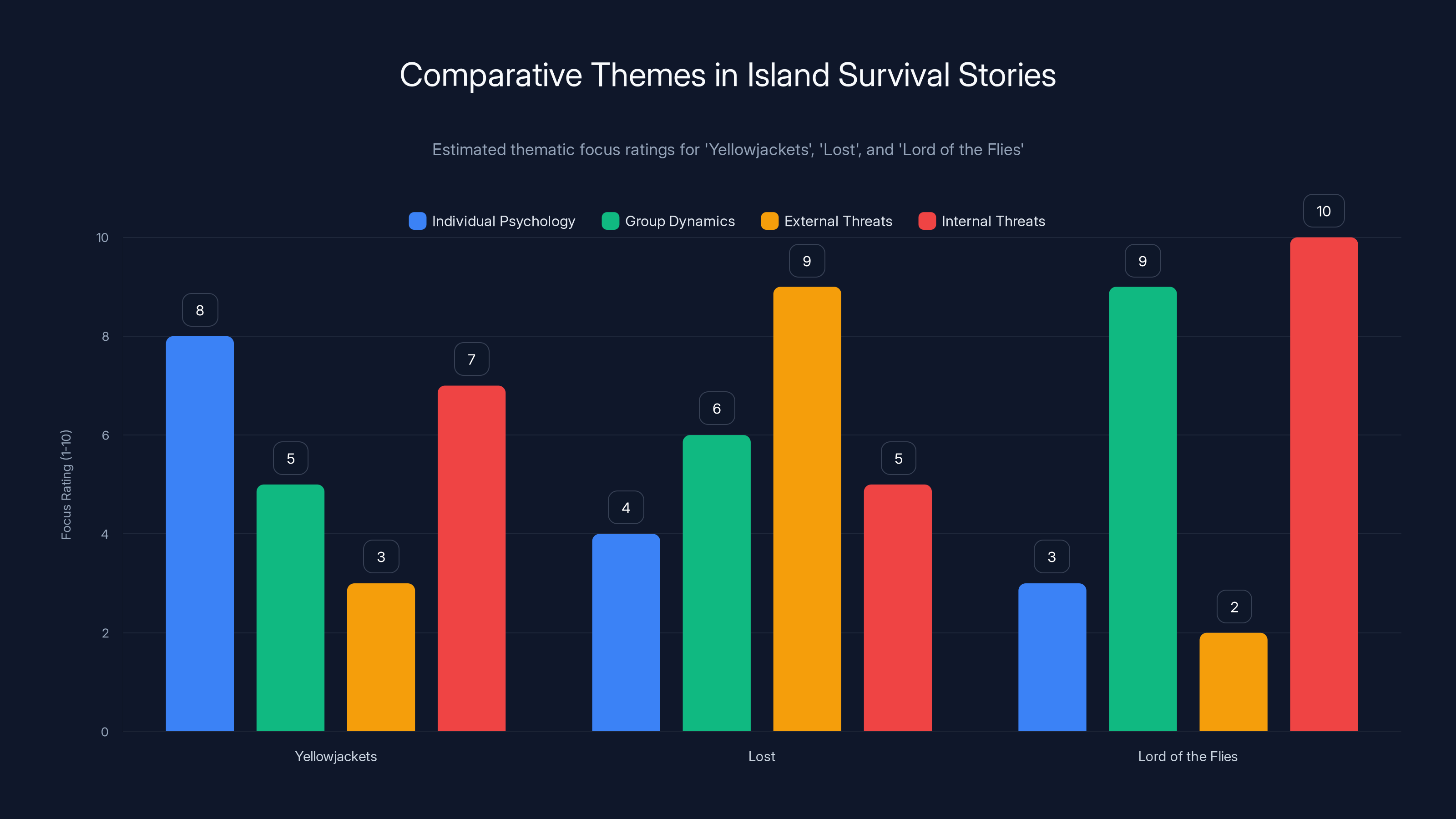

The Emmy-nominated series "Yellowjackets" (which airs on Showtime and stars Melanie Lynskey, Juliette Lewis, and others) follows a high school soccer team stranded in the wilderness. The show explicitly engages with "Lord of the Flies" as a reference point, showing how the boys' and girls' survival story plays out differently when the group includes females and is dealing with contemporary trauma.

"Yellowjackets" is a more modern, more explicitly dark interpretation. It includes substance abuse, sexual violence, and explicitly traumatic events. It's also more interested in the long-term psychological consequences of survival trauma—the series jumps between the stranded period and the survivors years later, dealing with PTSD and the ways trauma reshapes personality.

Where "Yellowjackets" and the BBC's "Lord of the Flies" differ is fundamental. "Yellowjackets" is interested in individual psychology and trauma. "Lord of the Flies" is interested in group psychology and social systems. Both are valuable lenses, but they focus on different aspects of human experience.

Lost and Serialized Television's Island Mythology

"Lost" (2004-2010) also engaged with island survival, but as a platform for mystery and supernatural elements rather than as a straightforward exploration of social organization. The island in "Lost" is actively hostile in ways the island in "Lord of the Flies" is not. The survival challenges in "Lost" come from the island itself—the Others, the hatch, the mysterious forces—rather than from the survivors' own tendencies toward tribalism.

This is a different narrative tradition. "Lost" is about external threats. "Lord of the Flies" is about internal threats—the threat that the boys pose to each other.

Surviving Trump, Brexit, and Political Tribalism

What's interesting about the BBC releasing a "Lord of the Flies" miniseries in 2026 is the timing. Golding's novel was a response to World War II and 1950s politics. The 1963 film arrived in the midst of civil rights conflicts. The 1990 film came at the end of the Cold War.

The 2026 version arrives in a political context characterized by increasing tribalism, the polarization of political movements, and a widespread sense that the systems meant to protect order are weakening. The novel's exploration of how quickly people sort into tribal groups, how easily they dehumanize those on the other side, and how violence seems to resolve conflicts in the short term—these feel remarkably contemporary.

The miniseries probably won't explicitly reference contemporary politics. But audiences will read it through the lens of contemporary political tribalism. This will probably enhance the novel's impact for 2026 audiences, making the fictional island feel like a metaphor for actual social divisions.

The Miniseries Format: Advantages and Challenges

Why Miniseries Works Better Than Films

A film adaptation must compress a novel into roughly two hours. This requires cutting scenes, combining characters, and accelerating pacing. A miniseries can allocate several hours to the same material, allowing for fuller development of character arcs, deeper exploration of psychological states, and more patience with scenes that build atmosphere rather than plot.

"Lord of the Flies" is a novel where the slow accumulation of small moments matters more than plot momentum. The way Jack's popularity grows isn't because of major events but through dozens of small interactions. The way the boys' perception of the island changes isn't sudden but gradual. The way fear becomes the dominant emotion isn't telegraphed but built through accumulation.

A miniseries can take the time for this accumulation. It can devote entire episodes to exploring a single day on the island, to deepening relationships, to showing how the boys' internal states shift.

The Risk of Pacing

The challenge with a miniseries is pacing. A film's dramatic structure is shaped by the need to resolve within a specific timeframe. A miniseries can lose momentum if not carefully managed. If the descent into savagery feels too gradual, audiences might lose engagement. If it feels too abrupt, it contradicts the novel's insistence that these boys are making reasonable choices given their circumstances.

The BBC will need to find a balance. The miniseries needs to maintain viewer investment episode to episode. This might mean making the survival challenges more urgent, the interpersonal conflicts more explicit, or the stakes clearer than Golding's novel does. But these changes risk flattening the novel's exploration of how normal people participate in tribalism almost without noticing.

Using Multiple Perspectives

Because of its length, the miniseries can develop multiple perspective characters. The novel is primarily from Ralph's perspective, with occasional shifts to other viewpoints. A miniseries could dedicate episodes or significant portions of episodes to Ralph, Jack, Piggy, and Simon's internal experiences.

This would be a substantial change from the novel, but it could deepen viewer engagement. Seeing events from Jack's perspective wouldn't excuse his actions but would help audiences understand the internal logic that makes his choices seem sensible to him.

The cultural impact of 'Lord of the Flies' has seen fluctuations, with a resurgence in interest around major adaptations. Estimated data.

What the Trailer Reveals

The BBC released a first trailer that gives hints about the production's approach. The trailer includes the line "We need to think about food and shelter. We need to help each other and be good camp mates." This is Ralph speaking early in the story, during the period when he still believes cooperation and reasoned planning will ensure survival.

The trailer also shows images of boys in various states of distress—some coordinated as a group, some isolated, some engaged in activities that suggest hunting or tribal rituals. The visual progression probably moves from organized group to fractured factions to outright conflict.

The production design, based on trailer imagery, appears to create a detailed island environment. The shelters the boys build look substantial and realistic rather than overly dramatic. The signal fire appears to be a recurring visual element. The landscape looks both beautiful and isolating—a place that could sustain life but only if the boys cooperate.

The casting of numerous non-professional actors suggests the production wanted authenticity over polish. These are boys who might actually live on an island, rather than actors playing boys. Their dialogue delivery probably sounds natural rather than scripted, their movements ungraceful rather than choreographed.

Production Timeline and Marketing Strategy

Why a February Release?

The February release date is strategic. British television audiences are typically more engaged during winter months when outdoor activities are less appealing. A complex psychological drama fits well with the viewing patterns of February. The network can build audience through word of mouth and critical reception before spring arrives.

The BBC has likely been building anticipation since the trailer dropped. Production companies typically release trailers 2-3 months before premiere to build awareness while maintaining freshness. The miniseries probably has substantial social media presence, interviews with cast members, and articles exploring the production's themes.

Global Distribution Strategy

While BBC One airs the series first in the UK, international distribution will follow through platforms like Brit Box, which brings BBC content to North America, Latin America, and other regions. This global reach means the miniseries will likely become a cultural touchstone beyond just UK audiences, similar to how BBC's "Sherlock" or "Bodyguard" reached international audiences.

The miniseries' success internationally will depend partly on how accessible it is to non-UK audiences. The setting is deliberately British (the boys are evacuees from war-torn England), and the production design probably reflects that context. But the themes of tribal conflict and social breakdown transcend national contexts, so the miniseries should resonate broadly.

Broader Implications: Why Golding Matters Now

The Decline of Institutional Trust

One reason "Lord of the Flies" remains relevant is because it explores what happens when institutional authority collapses. The boys don't rebel against authority—authority simply isn't present. In Golding's time, this was a thought experiment. In 2026, institutional authority in many Western democracies feels genuinely threatened by erosion from multiple directions.

The novel suggests that removing formal authority doesn't lead to freedom. It leads to informal authority, often more oppressive than formal authority could be. Jack has more complete power over his tribe than any formal government would typically exercise, precisely because he controls both the explicit rules and the implicit status systems.

Audiences in 2026 might view the miniseries through the lens of what happens when institutions fail or lose legitimacy. The novel's exploration becomes not just an exploration of human nature but an exploration of what governance structures prevent.

The Question of Human Nature

Golding's novel raises a question that's never been definitively answered: are humans naturally cooperative or naturally tribal and aggressive? Is civilization something we've achieved through effort and institution-building, or is it something that comes naturally that we sometimes abandon?

The real-life example of the stranded Tongan boys suggests humans are more cooperative than Golding's fiction implies. Yet there's plenty of historical evidence supporting Golding's darker view. The miniseries won't resolve this question, but it will let audiences inhabit the question through the characters' experiences.

Literature into Adaptation

The production of the miniseries raises questions about why classic literature continues to be adapted. The novel is readily available. Readers can engage with Golding's actual prose and interior monologues. Why does BBC invest in creating a visual adaptation?

Partly, adaptation is about reaching audiences who won't read the novel. Partly, it's about the specific qualities that different media can explore. Film and television can show physical spaces, relationships, and action in ways prose can't. They can also flatten or distort complexity in ways prose doesn't. The miniseries will be different from the novel not better or worse but different.

While 'The Coral Island' emphasizes civilization and survival, 'Lord of the Flies' focuses on the darker aspects of human nature and violence. Estimated data based on thematic analysis.

The Isle of Setting: Geography as Character

The Island as Isolated System

The island in "Lord of the Flies" isn't incidental to the story. It's crucial. The island is isolated enough that rescue is uncertain and the boys know they're truly on their own. But it's large enough and complex enough that it feels like a world rather than a single location.

The island has geography—a jungle, a mountain, a beach, a lagoon. Different factions establish territory in different parts of the island. The mountain is valuable because it's where the signal fire can be spotted from ships. The jungle is where hunting happens. The beach is where the boys assemble.

The miniseries will need to establish this geography clearly so audiences understand the physical world the boys are navigating. The cinematography probably uses the island's natural features to symbolize the psychological states of the different groups. Ralph's group might be associated with the beach, the visible, the hopeful. Jack's group might be associated with the jungle, the hidden, the primal.

Climate and Environment as Pressure

The island is tropical, which means the boys face different survival challenges than British children might expect. It's hot. The sun is intense. Tropical illnesses are possible. The weather can be unpredictable. These environmental pressures contribute to the stress and tension that make poor decision-making more likely.

The miniseries probably depicts the boys as becoming increasingly uncomfortable with their environment as the story progresses. Early on, the island might seem beautiful and exciting. By the midpoint, it probably feels oppressive and hostile. By the end, it's a nightmare landscape where beauty has been replaced by horror.

Character Arcs and Development

Ralph's Trajectory: From Confidence to Desperation

Ralph's arc is one of progressive failure. He begins confident that organization and reason will ensure survival and rescue. He makes decisions with genuine belief that they're right. As the miniseries progresses, he watches his support erode as boys migrate to Jack's tribe. By the end, he's hunted and desperate, aware that the system he built has failed.

The tragedy isn't that Ralph was wrong about what would work—rescue does come. The tragedy is that Ralph is right about what's necessary but unable to convince others when Jack offers something more immediately appealing. Ralph's character exploration is essentially about the failure of reasoned argument when it competes with tribal appeal.

Jack's Transformation: From Competitive Boy to Tribal Leader

Jack's arc is about the corruption that comes from unchecked power. Early in the story, Jack respects the same rules as everyone else. He participates in assemblies. He listens to Ralph. But as hunting becomes more successful and his status grows, Jack increasingly disregards the collective agreement.

Jack's character is interesting because he doesn't view himself as corrupt. He views himself as a superior leader, more realistic about what matters. He doesn't think maintaining a signal fire is smart. He thinks hunting is smart. He doesn't think democratic assemblies work. He thinks strong leadership works.

Jack's tribalism isn't presented in the novel as a moral failing but as a different philosophical position. He's wrong, the novel suggests, but not in a way that's obvious to him or to the boys who follow him.

Piggy's Intellectual Helplessness

Piggy's character arc is about the powerlessness of intellectual argument in face of physical and social power. Piggy sees what's happening. He understands the consequences. He argues effectively for why maintaining the signal fire matters, why rules matter, why cooperation matters.

But Piggy is physically weak. He's socially awkward. He can't hunt. Within the hierarchy that forms, Piggy has low status. His arguments are ignored not because they're unconvincing but because the person making them doesn't have social power. This is a crucial distinction. Piggy isn't wrong. He's just powerless.

Piggy's death represents the death of the argument for reasoned civilization. After Piggy and the conch are gone, there's no intellectual counterweight to Jack's tribal power. Ralph's only option becomes survival, not leadership.

Simon's Role: The Moral Witness

Simon is perhaps the most morally sound character in the novel. He doesn't seek power. He genuinely tries to help others. He appears to have some kind of spiritual or philosophical insight that the other boys lack.

Simon's death—killed by the other boys in a frenzy while they believe they're hunting the beast—represents a crucial moment. The boys kill the character who is morally closest to what they should be. This isn't because Simon is a threat. It's because the mob frenzy has taken over rational thought.

The miniseries will need to show Simon's quiet dignity and moral clarity, and then show how little that matters when the group decides something else entirely. Simon's death should feel like a tragedy not because he's more sympathetic than other characters but because it represents the point at which moral clarity becomes irrelevant to group decision-making.

Violence in the Narrative: From Metaphorical to Literal

The Gradual Escalation

"Lord of the Flies" doesn't begin with violence. It begins with order, organization, and reasonable planning. Violence emerges gradually. First, there's the competitive hunt. Then there's the ritualized pig hunt. Then there's the hunt for the beast. By the time actual violence against boys occurs, the narrative has already prepared the ground.

The miniseries will likely show this escalation carefully. The first hunting scene is probably exciting and adventurous. By the time the boys are hunting each other, audiences should understand how they arrived at that point. The violence shouldn't feel random or inexplicable but rather like the logical conclusion of the choices the characters have been making.

Depicting Violence Responsibly

The BBC has content standards that constrain how violence can be depicted. The miniseries won't show graphic violence in the way more adult-oriented streaming services might. Yet the novel's violence—the deaths of Piggy and Simon, the hunt for Ralph—is central to the story.

The BBC will need to suggest violence in ways that are impactful without being gratuitous. This might mean focusing on the emotional and psychological impact of violence rather than explicit visual depiction. The reactions of the boys who participate in violence, and the horror of those who witness it, might matter more than visual detail.

This chart compares thematic focuses in 'Yellowjackets', 'Lost', and 'Lord of the Flies'. 'Yellowjackets' emphasizes individual psychology, while 'Lost' focuses on external threats. 'Lord of the Flies' primarily explores internal threats and group dynamics. Estimated data.

Dialogue and Language: Translating the Novel's Voice

Golding's Prose Style

The novel's prose is deceptively simple. Golding writes with clarity and directness, using relatively short sentences and accessible vocabulary. This simplicity makes the novel's exploration of dark themes more powerful—the simplicity of the prose doesn't match the complexity of the ideas.

The miniseries' dialogue will need to capture something of this simplicity without being overly stylized. The boys speak clearly and directly to each other. Their conversations are about practical matters: food, shelter, fire, rescue. The philosophical implications emerge from practical concerns rather than being explicitly stated.

Regional Accent and Class Markers

The boys are British, evacuated from war-torn England. They're from various social classes—some from privileged backgrounds, some from working-class families. Golding doesn't emphasize class differences, but they're present in the novel.

The miniseries' dialogue probably uses accents and speech patterns that suggest class backgrounds. Ralph, as a leader, might speak in ways that suggest education and privilege. Jack, charismatic but more physical, might speak differently. The littluns probably speak differently than the older boys.

These linguistic differences can subtly shape how audiences perceive the characters and their conflicts. They can also reflect the way class and social positioning influence who emerges as a leader.

Cinematography and Visual Language

Color as Psychological State

The 1963 film used black and white cinematography, which gave it a stark, primitive quality appropriate to the novel's themes. The 1990 film used color, which made the island beautiful and vibrant.

The BBC miniseries, being contemporary production, will almost certainly use color. The question is how color is used symbolically. Early episodes might feature warm, golden light suggesting hope and possibility. As the story progresses, the lighting might become harsher, more blue-toned, more threatening. The island might transform visually from paradise to nightmare.

The color grading probably shifts between factions. Ralph's group might be shot in warmer tones. Jack's tribe might be shot in cooler, harsher tones. These visual differences reinforce the psychological and thematic differences between the groups.

Camera Movement and Framing

Early in the miniseries, camera movement is probably stable and measured. Characters are framed clearly in medium shots that allow audiences to see relationships and group dynamics. As the story progresses, the camera work probably becomes more chaotic. Handheld camera work, shakier framing, and tighter close-ups might suggest the psychological chaos and loss of control.

The hunt scenes probably feature different cinematography than the assembly scenes. Hunts might use dynamic camera movement, varied angles, and montage editing that creates energy and excitement. Assemblies might use static camera positions, wider shots showing group formation, and cutting that emphasizes dialogue and discussion.

The Role of Music and Sound Design

Silence as a Tool

Sound design in a psychological drama is as important as visual design. Silence—the absence of music or dialogue—can be more powerful than sound. The miniseries probably uses silence strategically, especially in moments of tension or moral gravity.

When violence is imminent, the sound design probably strips away music and emphasizes natural sounds. The breathing of the boys, the rustling of vegetation, the crashing of waves. This focus on natural sound makes the moment feel more real and more urgent.

Music to Suggest Psychological States

When music is present, it probably serves to emphasize emotional states or thematic content rather than to drive plot momentum. Early in the miniseries, music might suggest the beauty and possibility of the island. As tribalism grows, the music might shift to suggest danger and inevitability. By the end, the music probably feels ominous and tragic.

The miniseries probably avoids obvious musical cues that suggest good guys and bad guys. Instead, the music probably creates mood and atmosphere, allowing audiences to feel the psychological reality of the situation rather than having emotions prescribed for them.

Critical Reception and Expectations

The Challenge of Meeting Expectations

The novel has been adapted before. It's studied in schools. It's part of literary canon. Any new adaptation faces the challenge of meeting an audience that already knows the story and has established ideas about how it should be told.

The BBC's miniseries has advantages: more time than films, institutional support, access to the Golding family. But it also faces the inherent challenge that many literary adaptations face: the novel is a specific artistic achievement. The miniseries can explore similar themes but can't fully replicate the experience of reading Golding's prose.

Critical reception will likely focus on whether the miniseries captures the novel's philosophical depth or whether it oversimplifies for dramatic purposes. Critics will probably praise or criticize the pacing, depending on whether they believe the slow build creates psychological tension or becomes tedious.

Audience Reception Across Demographics

The miniseries will probably reach audiences of various ages and backgrounds. Some will be coming to the story for the first time. Some will be familiar with the novel. Some will be familiar with previous adaptations. These different audiences will probably have different responses.

Younger viewers encountering the story for the first time will probably respond to the survival and adventure elements as well as the darker elements. Older viewers familiar with the novel might be more critical of specific choices and interpretations. The miniseries probably works best if it satisfies multiple audiences simultaneously—providing adventure and emotional engagement for some viewers while providing philosophical depth and nuance for others.

FAQ

What is the basic premise of Lord of the Flies?

A group of young British boys evacuated from war-torn England during an airplane crash find themselves stranded on an uninhabited island. Without adult authority or external structure, they attempt to organize themselves and maintain a signal fire for rescue. As time passes, their carefully established social order begins to break down, splitting into two rival factions led by Ralph and Jack, eventually descending into tribalism and violence. The novel explores how quickly civilization can collapse and how naturally humans resort to tribal hierarchies and violence when external authority is removed.

When does the BBC's Lord of the Flies miniseries premiere?

The BBC's new miniseries adaptation premieres on BBC One on February 8, 2026. The series will subsequently become available through Brit Box and other platforms for international distribution. The exact episode schedule and number of episodes haven't been widely publicized, but miniseries typically air on a weekly schedule over 4-8 weeks.

How does the BBC's adaptation differ from previous film adaptations?

The BBC miniseries has several key differences from previous adaptations. First, it's a miniseries rather than a film, giving it several hours instead of two hours to develop characters and explore themes. Second, it uses many non-professional young actors alongside professionals, prioritizing authenticity over polish. Third, the BBC has the Golding family's blessing and has committed to staying faithful to the novel's core themes and philosophical darkness. Fourth, the miniseries can explore the slow psychological descent more carefully than films, showing how tribalism emerges from reasonable choices rather than depicting it as sudden moral corruption.

What is the novel really about beyond the surface survival story?

While "Lord of the Flies" appears to be about boys surviving on an island, it's actually an exploration of human nature, social organization, and how quickly tribal instincts override civilized cooperation. Golding wrote it as a response to the optimistic belief that civilization is natural and inevitable, suggesting instead that civilization is fragile and requires constant effort to maintain. The novel explores how leadership, status, fear, and group psychology work to create hierarchy and tribal violence. It's essentially a philosophical novel using survival adventure as the mechanism to explore these ideas.

Who are the main characters in the miniseries, and what are their roles?

Winston Sawyers plays Ralph, the boy who initially emerges as a leader and tries to establish rational systems for survival. Lox Pratt plays Jack, the charismatic leader of the hunters who eventually forms a rival faction. David Mc Kenna plays Piggy, Ralph's advisor and the intellectual voice for maintaining civilization. Ike Talbot plays Simon, a quiet, morally grounded boy. The miniseries also features numerous other young actors in supporting roles as the "big 'uns" and "littluns" (older and younger boys) who experience the descent into tribalism from various perspectives.

Is the miniseries faithful to the novel, or does it make significant changes?

The miniseries has the Golding family's blessing, suggesting it will be generally faithful to the novel's core themes and structure. However, adaptation necessarily requires changes. Internal monologues must become dialogue or visual storytelling. Some scenes must be condensed or expanded. But these changes are meant to serve the novel's core ideas rather than contradict them. The miniseries will likely maintain the novel's philosophical darkness and refusal to offer easy moral judgments.

What makes this adaptation timely for 2026?

Golding's exploration of tribalism, the erosion of institutional authority, and how fear can be weaponized feels strikingly relevant to 2026 politics and social divisions. The novel was written as a response to World War II and 1950s concerns. Each adaptation arrives in different political contexts and invites audiences to read the story through contemporary lenses. The 2026 miniseries will likely resonate with audiences concerned about political polarization, institutional trust, and the fragility of social order.

How does the novel handle violence, and how will the miniseries depict it?

The novel includes significant violence, including the deaths of two young boys. However, Golding doesn't present violence as sensational or glorified. The violence emerges from the logic of tribal competition and fear, making it feel inevitable rather than shocking. The BBC miniseries, operating within content guidelines, will probably suggest violence through psychological and emotional impact rather than graphic depiction. The miniseries will likely focus on why the violence occurs and how it changes the boys, rather than on visual detail.

What are the historical contexts that influenced Golding's writing?

William Golding wrote "Lord of the Flies" in 1954, nine years after World War II ended and in the early years of the Cold War. Golding had served in World War II and had witnessed the capacity for violence that civilized societies possessed. The novel was written partly as a response to "The Coral Island," an earlier children's novel that suggested civilization and Christianity naturally bring order to "savage" places. Golding wanted to invert this assumption, suggesting instead that human nature naturally tends toward tribalism and that civilization requires constant effort and institutional support to maintain.

Why has Lord of the Flies been both celebrated and challenged as an educational text?

The novel is celebrated for its philosophical depth, its exploration of human nature, and its refusal to offer easy moral comfort. Teachers value it for prompting discussions about social organization, leadership, and ethics. However, the novel has been challenged and banned in some schools because of its graphic violence, its dark view of human nature, and its treatment of tribal brutality. Some argue the novel is misread as a scientific statement about how humans naturally behave rather than as a philosophical fiction. These debates about the novel's value and message will likely influence how the miniseries is received and discussed.

Conclusion: Why This Matters Now

William Golding wrote "Lord of the Flies" nearly 70 years ago. Since then, the world has changed in countless ways. Telecommunications have made isolation nearly impossible. Society's understanding of psychology and sociology has advanced. Digital media has created new forms of tribal belonging and new mechanisms for fear weaponization.

Yet the novel's core insights feel more relevant, not less. We've watched institutional authority erode in countless contexts. We've seen how quickly groups of reasonable people can divide into hostile tribes. We've seen how easily fear can be manufactured and used for control. We've observed that education and civilizational advancement don't inoculate humans against reverting to tribalism under pressure.

The BBC's miniseries arrives at a moment when these questions feel urgent. Not because the novel is a blueprint for understanding current events, but because it explores mechanisms and psychology that underlie tribal conflict regardless of context.

The miniseries won't provide answers. Golding's novel doesn't provide answers. What it does is create space to explore questions: What holds civilization together? How easily does it fall apart? What is the appeal of tribalism? How do fear and power interact to create systems of control? What does it take to maintain reasoned cooperation when immediate tribal belonging is available?

These questions matter because they're not academic. They play out in political movements, in social media tribalism, in institutional failures, and in personal relationships. The miniseries won't solve anything, but it will let audiences inhabit these questions through characters they care about in situations that feel emotionally real.

When the BBC's "Lord of the Flies" premieres on February 8, 2026, it will reach audiences who've never read the novel, audiences who read it in school and remember it dimly, and audiences who know it well. All of these audiences will encounter a story about how quickly things fall apart, about the power of charisma and tribal belonging, and about the fragility of the social agreements that allow humans to cooperate.

In a moment when these themes feel urgent rather than abstract, this miniseries has the potential to be genuinely important television—not important because it's timely, but important because it explores truths about human nature that remain true regardless of era, and does so with the psychological depth that a miniseries format finally allows.

Key Takeaways

- BBC's Lord of the Flies miniseries premieres February 8, 2026, with Golding family blessing and commitment to staying faithful to the novel's philosophical darkness

- The miniseries format provides crucial advantages over previous film adaptations by allowing several hours to develop characters and explore the slow psychological descent into tribalism

- William Golding wrote the 1954 novel as a response to post-WWII optimism and the overly positive 'Coral Island,' exploring how quickly civilization collapses when authority is removed

- The cast features Winston Sawyers as Ralph (the rational leader), Lox Pratt as Jack (the charismatic tribal leader), and David McKenna as Piggy (the intellectual advisor), with many non-professional young actors providing authenticity

- The novel remains strikingly relevant to 2026 audiences grappling with tribalism, institutional erosion, and questions about how quickly reasonable people can descend into group violence

Related Articles

- Under Salt Marsh: The Crime Thriller Yellowstone Fans Need to Watch [2025]

- Watch The Traitors UK Season 4 Finale Free [2025]

- Chris Chibnall's Seven Dials: Crafting Modern Mystery Television [2025]

- A Thousand Blows Season 2 Review: Disney+ Bareknuckle Boxing Drama [2025]

- A Thousand Blows Season 2: How Much Is Actually Real? [2025]

- Public Domain 2026: Betty Boop, Pluto, Nancy Drew [2025]

![BBC's Lord of the Flies Miniseries: Complete Guide to the 2026 Adaptation [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/bbc-s-lord-of-the-flies-miniseries-complete-guide-to-the-202/image-1-1769638380282.jpg)