Introduction: Why Crime Movies Matter in Cinema

Crime films occupy a unique space in cinema. They're not just about catching bad guys or heists gone wrong—they're intricate studies of human nature, morality, and the systems we've built to police ourselves. The best crime movies work like philosophical puzzles wrapped in compelling storytelling.

Directors and screenwriters routinely cite specific crime films as foundational to their craft. When Bart Layton, the writer-director of Crime 101 (which stars Chris Hemsworth), discusses his favorite crime movies, he's not talking about popcorn entertainment. He's talking about films that fundamentally changed how he thinks about narrative structure, character development, and moral ambiguity.

The crime genre has evolved dramatically since its inception. What started as simple procedural storytelling in the early days of cinema has become a sophisticated exploration of institutional failure, personal corruption, and systemic injustice. The best examples transcend their genre classifications—they become philosophical examinations of law, order, and chaos.

What makes certain crime movies "endlessly brilliant and rewatchable," as Layton describes his favorites? It's not just compelling plots or shocking twists. It's how they use the crime narrative framework to ask deeper questions about human nature. Every rewatch reveals new layers: dialogue takes on different meanings, character motivations become clearer, and the thematic resonance deepens.

The influence of great crime cinema extends far beyond the genre itself. Cinematography techniques developed for noir films shaped how we light everything from documentaries to commercials. Editing rhythms pioneered in crime thrillers became the baseline for modern action filmmaking. The way crime stories handle exposition and revelation influenced how television dramas structure their narratives.

Understanding which crime movies resonated most with working filmmakers provides insight into what separates competent crime films from transformative ones. This article explores the essential crime movies that directors consistently cite as foundational, examining what makes them work and why they've endured for decades.

TL; DR

- Crime genre evolution: From noir classics to psychological thrillers, crime cinema continually reinvents itself while exploring timeless themes of morality and institutional failure

- Director influences: Working filmmakers cite specific crime masterpieces as structural and thematic blueprints for their own projects

- Rewatchability factor: The best crime films reveal new layers with each viewing, offering fresh insights into character psychology and narrative structure

- Technical innovation: Crime movies pioneered cinematography and editing techniques that influenced filmmaking across all genres

- Thematic depth: Essential crime films transcend plot mechanics to examine fundamental questions about justice, corruption, and human nature

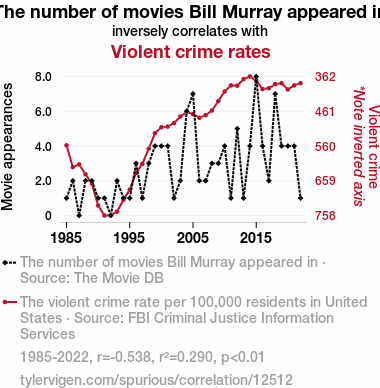

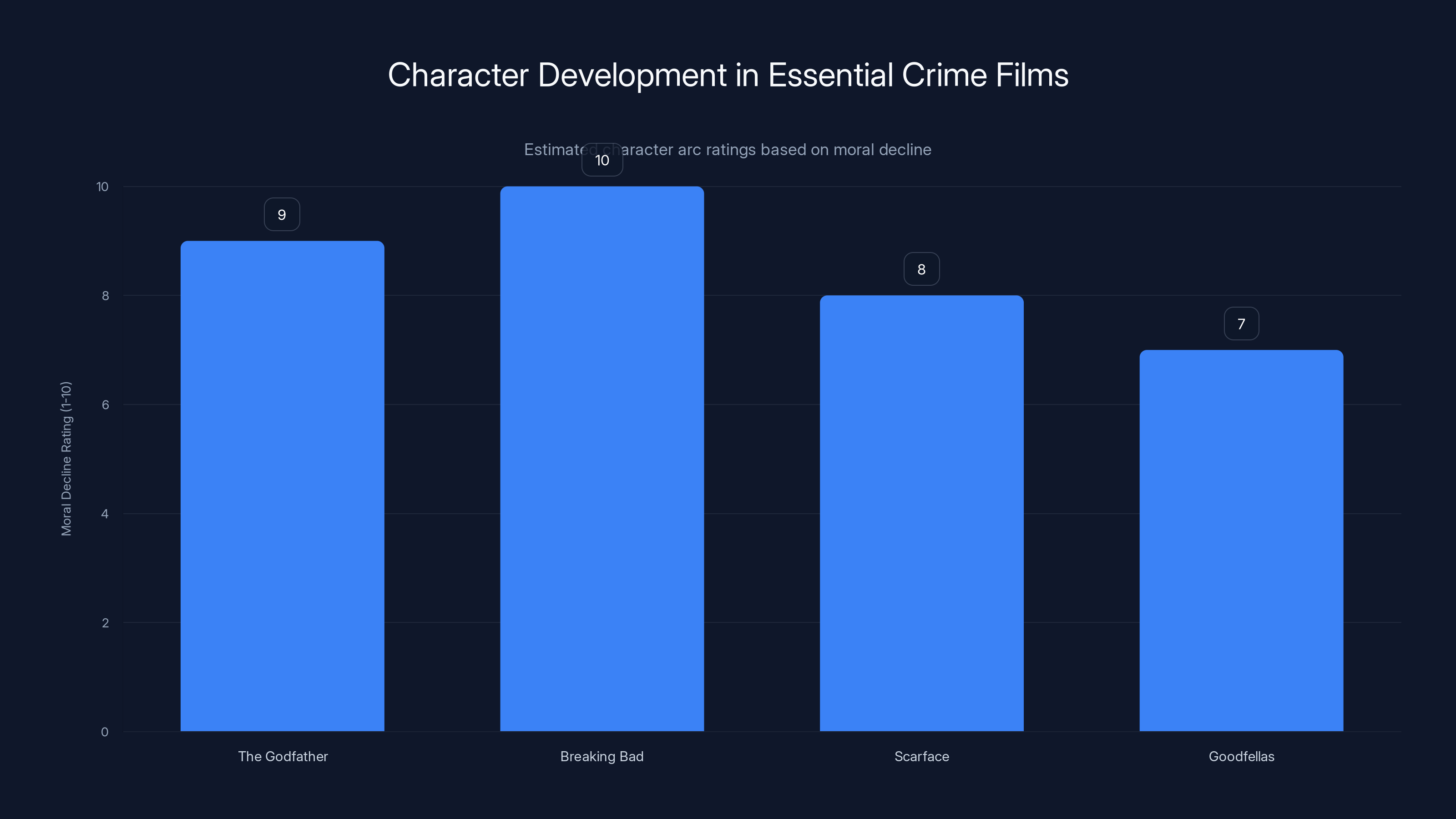

Essential crime films often depict protagonists' moral decline, with 'Breaking Bad' and 'The Godfather' showcasing significant transformations. (Estimated data)

The Definition of Essential Crime Cinema

What separates a good crime movie from one that becomes "essential" in the eyes of serious filmmakers? It's a distinction worth clarifying because not every well-executed heist film or detective story qualifies.

Essential crime cinema operates on multiple levels simultaneously. On the surface, it delivers on the genre's fundamental promise: compelling storytelling about crime, investigation, or moral transgression. But beneath that surface layer, it explores something deeper about human psychology, social structures, or the nature of justice itself.

Take the difference between a crime movie that's enjoyable to watch once and one that demands repeated viewings. The first type might have clever plot twists and good performances. The second type has something else—a structural sophistication or thematic resonance that makes viewers want to experience it again, knowing the ending.

Filmmakers recognize essential crime cinema by its influence on their own work. When a director cites a film as inspiration, they're often referring to how it solved specific narrative problems they later faced. How did it handle exposition? How did it develop moral ambiguity? How did it make audiences care about characters who do terrible things?

Another marker of essential crime cinema is its ability to transcend its time period. A crime film from the 1950s shouldn't feel dated if it's truly essential—the craftsmanship, storytelling, and thematic content should speak across decades. This doesn't mean ignoring historical context; rather, it means the core insights about human nature remain constant.

The technical execution also matters. Essential crime films often pioneer techniques that become standard practice. The way they frame shots, cut sequences, use sound design, and structure scenes influences how other filmmakers approach their work. This isn't accidental—it's the result of problem-solving under creative constraints.

The Birth of Crime Cinema: Noir's Lasting Influence

Crime cinema didn't invent darkness or moral ambiguity, but film noir codified how to present these elements visually and narratively. The genre emerged in the 1940s, though its roots trace back to earlier detective fiction and the cynical atmosphere of post-Depression America.

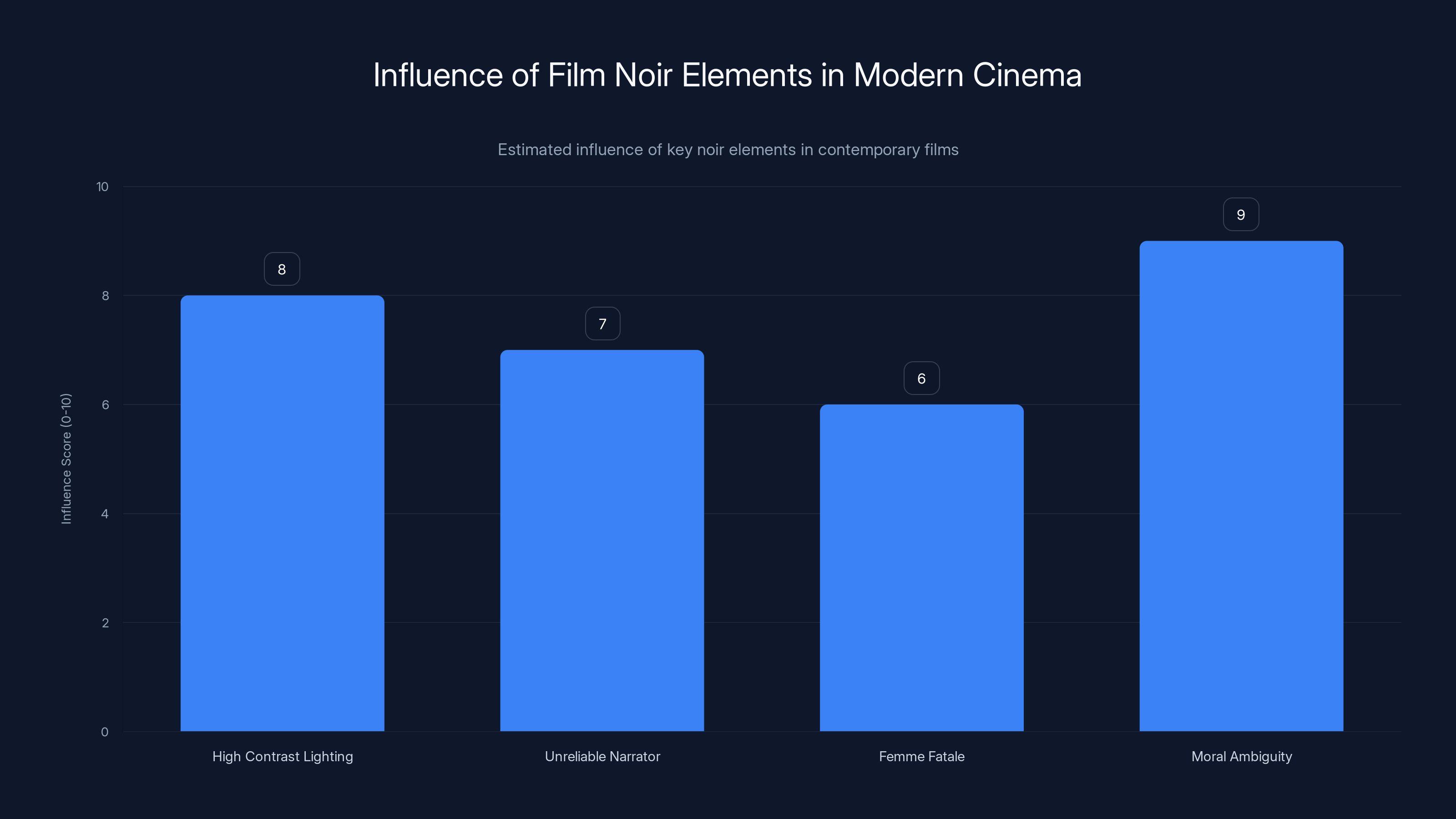

Film noir established visual language that persists today. High contrast lighting, shadows obscuring character faces, dutch angles suggesting instability—these weren't decorative choices. They communicated psychological states and moral uncertainty through pure cinema. A character lit entirely from below, with shadows distorting their features, immediately signals that something is wrong about them, without needing exposition.

The narrative structure of noir also proved enormously influential. The unreliable narrator, the femme fatale whose motivations remain opaque, the protagonist trapped by circumstance—these became templates that filmmakers still use. But the truly essential noir films aren't just stylistic exercises. They explore what happens when individual morality collides with corrupt systems.

The Maltese Falcon from 1941 remains mandatory viewing for anyone serious about understanding crime cinema. The film works perfectly as a detective mystery, with engaging plot mechanics and charismatic characters. But it also functions as a meditation on loyalty, deception, and the way that pursuing material wealth corrupts everyone it touches. The falcon itself isn't valuable because of its intrinsic worth—it's valuable because everyone believes it is, which makes it a perfect metaphor for capitalism itself.

The Asphalt Jungle from 1950 invented the heist film template. Every heist movie made afterward owes something to its structure: the assembly of a specialist team, the detailed planning sequence, the complications that emerge during execution. But what makes it essential is how it treats the criminal crew as tragic figures. These aren't evil people—they're desperate people driven by circumstance and greed, and their tragedy is inevitable.

Noir filmmakers understood that the most interesting crime stories aren't about catching criminals; they're about the psychological cost of crossing moral boundaries. They're about how corruption works—not as a sudden fall but as a series of small compromises that accumulate.

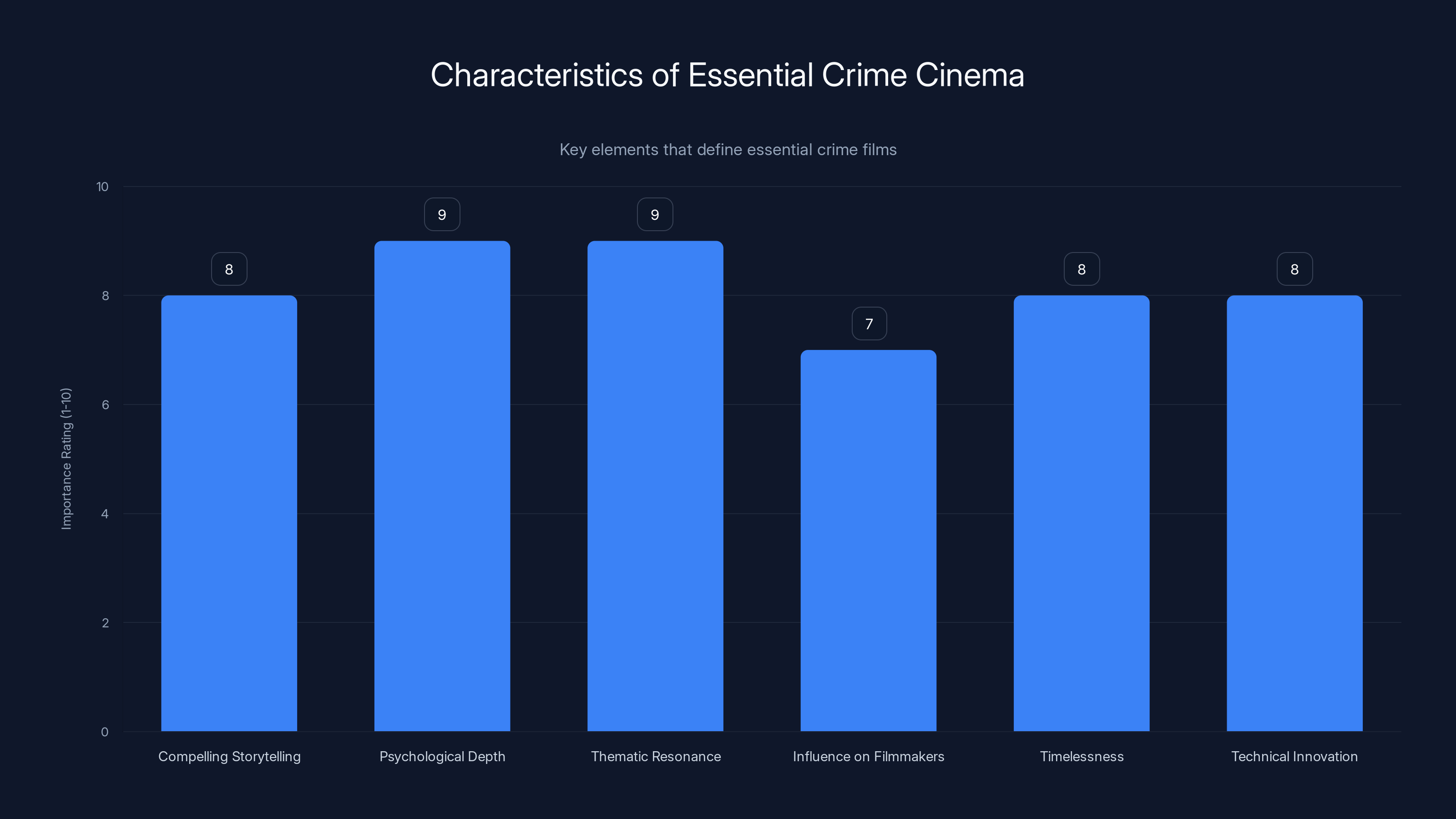

Essential crime cinema is defined by its psychological depth, thematic resonance, and technical innovation, making it influential and timeless. (Estimated data)

Psychological Crime Dramas: The Moral Complexity Shift

As the 20th century progressed, crime cinema shifted focus. Rather than external mysteries (who did it?) the emphasis moved toward internal mysteries (why do we do terrible things?). This shift represented a fundamental change in how filmmakers understood the crime genre's potential.

Psychological crime dramas treat criminal acts not as mere plot mechanics but as windows into damaged human psychology. The investigation becomes secondary to understanding motivation. These films ask uncomfortable questions about whether we'd make similar choices under similar circumstances.

The Godfather stands as the watershed moment where crime cinema achieved complete artistic legitimacy. The film works on every level: as a family saga, as a business thriller, as a tragic decline narrative. But its genius lies in how it makes audiences complicit in understanding, even sympathizing with, monstrous choices.

Francis Ford Coppola structured the film so that we see Michael Corleone's transformation gradually. We watch as each moral compromise seems reasonable under pressure, understandable given circumstances. By the time he commits what would be unforgivable acts in isolation, we've been positioned to understand them as inevitable responses to an impossible situation. The film doesn't excuse his actions; it makes us understand them, which is more powerful.

The cinematography and editing support this psychological exploration. Gordon Willis's cinematography uses light and darkness not just for aesthetic effect but to track Michael's moral journey. As he becomes darker, the lighting becomes more severe. The editing rhythm shifts, making viewers feel the psychological pressure building.

Serpico from 1973 approaches police corruption from the opposite angle. Rather than following the criminal's perspective, it follows the cop fighting against systemic corruption. The film's power comes from showing how institutional pressures push toward compromise. Doing the right thing means sacrificing everything: career advancement, friendships, safety. The film suggests that moral integrity in corrupt institutions is nearly impossible to maintain.

Chinatown from 1974 masterfully combines noir visual language with psychological depth. The film's investigation gradually reveals not a solvable mystery but a glimpse of how power operates beyond the reach of conventional morality. The protagonist discovers that trying to do the right thing doesn't stop corruption—it just gets more people hurt. The film's final line, "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown," encapsulates the despair of facing systems too large and corrupt to change.

The Procedural Crime Film: Structure and Realism

While psychological crime dramas delve into character motivation, procedural crime films embrace detail and process. These movies find drama not in shocking revelations but in the meticulous work of investigation.

Procedural crime films succeed when they treat police work as inherently dramatic. The tension doesn't come from plot twists; it comes from watching competent professionals solve complex problems under constraints. The audience learns how investigations actually work and finds that learning process engaging.

Homicide from 1959 established many procedural conventions. The film methodically follows detectives through investigative steps: interviewing witnesses, examining evidence, following leads. The excitement emerges from watching intelligence and persistence work, not from manufactured plot devices.

L.A. Confidential from 1997 modernized the police procedural while maintaining noir aesthetics. The film balances multiple narrative threads: police corruption, a brutal murder investigation, moral compromises within law enforcement. What makes it essential is how it treats procedural detail seriously while maintaining narrative momentum and psychological depth.

The procedural approach gained enormous popularity through television, with shows like The Wire taking the approach to its logical extreme. These shows understand that the most interesting crime stories emerge from understanding systems: how do institutions really work? How do individuals navigate institutional pressures?

Procedural crime films that become essential do something beyond accurately depicting investigative steps. They ask what investigations reveal about the investigators themselves. How do detectives rationalize compromises? How does exposure to crime and violence change them? The best procedurals treat these questions as seriously as they treat plot mechanics.

The Heist Film: High-Stakes Theater

Heist films occupy a curious position in crime cinema. They're fundamentally about breaking laws, yet audiences root for the criminals. The best heist films understand that the appeal isn't just watching crimes succeed—it's watching impossible problems get solved through creativity and teamwork.

Heist films require a different kind of storytelling than other crime narratives. They must balance detailed planning sequences (which could be tedious) with enough unpredictability to maintain tension. The solution involves treating the planning as character development. How team members approach problems reveals who they are.

Heat from 1995 represents the apotheosis of the modern heist film. The film intercuts two parallel narratives: a professional thief's meticulous planning and execution, and a detective's equally professional investigation. The genius lies in how the film treats both sides symmetrically. The criminal and the cop aren't adversaries in a moral battle; they're competing professionals operating within their respective ethical systems.

Michael Mann's direction emphasizes procedural detail without sacrificing character development. The heist sequences work as pure technical cinema—watching professionals execute complex plans—while simultaneously revealing character psychology. The film's most famous scene, a shootout in the streets of Los Angeles, functions as both an action set piece and a statement about the film's themes. The shooting is meticulously choreographed, with professionals taking every precaution, yet remains terrifying because of realistic consequences.

Ocean's 11 takes a different approach. Rather than treating heist details with grim realism, it embraces the theatrical artificiality of the genre. The con isn't about fooling the audience; it's about including us in the joke. We know what's happening because the characters trust us to understand. This creates a collaborative viewing experience where audiences feel clever for following the complex mechanics.

The best heist films understand that the real "heist" might not be the central crime. In Heat, the real tension emerges from the relationship between the cop and the criminal, two men who might have been friends under different circumstances. In Ocean's 11, the heist against the casino becomes secondary to the heist against the audience, where we're delighted to discover we've been manipulated in clever ways.

Film noir's influence is evident in modern cinema, with elements like moral ambiguity and high contrast lighting scoring high on influence. Estimated data.

Institutional Corruption: The System as Criminal

Some essential crime films shift the focus from individual criminals to corrupt institutions. These films treat systems and organizations as the real perpetrators, with individual people simply operating within corrupt frameworks.

Institutional corruption stories acknowledge that most crime isn't committed by supervillains with elaborate plans. It emerges from normal processes becoming corrupted through small compromises and systemic pressures. This insight produces more disturbing crime stories than traditional good-vs-evil narratives.

There Will Be Blood doesn't qualify as crime fiction in traditional terms, but it functions as a corruption narrative examining how capitalism operates as an organized crime system. The protagonist's success depends on lying, manipulation, and destroying competitors. The film treats these not as aberrations but as logical extensions of capitalist logic.

The Departed from 2006 explores institutional corruption by embedding a criminal inside police institutions. The film's insight is that organized crime and police bureaucracy operate using similar logic. Both enforce codes of silence, both expect loyalty above legality, both advance through ruthlessness and political skill. The cop and the criminal informant become mirrors of each other.

TV series like The Wire expanded this approach across multiple seasons, showing how corruption pervades every institution: police, politics, education, media. The series suggests that individual corruption is almost irrelevant when systems operate corruptly at every level.

What makes institutional corruption narratives work cinematically is showing specific human costs. The abstract idea that "the system is corrupt" becomes powerful when we see particular people destroyed by that corruption. The most effective institutional corruption stories combine individual tragedy with systemic analysis.

International Crime Cinema: Expanding the Genre

The crime genre isn't limited to American cinema. International filmmakers have brought different sensibilities and structures to crime narratives, expanding what crime films can explore.

French cinema's contribution to crime cinema centers on philosophical noir. French directors treated crime stories as opportunities to examine existential questions about meaning, mortality, and moral authenticity. The human drama took precedence over plot mechanics.

Bob le Flambeur from 1956 treats a small-time criminal with tenderness and understanding. The film follows an aging gambler through his daily life, showing how he relates to his community. When he finally commits a crime, it emerges as natural extension of his character and circumstances, not a shocking transgression.

Scandinavia developed a distinctive approach to crime fiction, particularly through Henning Mankell's novels and their film adaptations. Scandinavian crime stories tend toward melancholy realism, suggesting that crime emerges from social alienation and systemic inequality rather than individual evil. The investigation often reveals not heroic police work but incremental progress through difficult terrain.

Japanese cinema brought entirely different sensibilities to crime narratives. Drunken Angel from 1948 explores crime through the lens of honor and shame rather than law and order. The yakuza operates within social structures where reputation and loyalty supersede legality.

South Korean cinema produced the extraordinarily influential Memories of Murder from 2003. The film functions simultaneously as serial killer procedural, critique of authoritarian policing methods, and examination of institutional failure. The ending refuses conventional resolution, suggesting that some systems are too broken to fix through individual effort.

International crime cinema reminds viewers that the genre's possibilities extend far beyond American crime story templates. Different cultures approach questions of law, order, and transgression from different angles, producing crime narratives that challenge American genre conventions.

Contemporary Crime Cinema: Moral Ambiguity in the Modern Age

Contemporary crime filmmakers inherited everything their predecessors developed and face the challenge of creating work that feels fresh while respecting established conventions. Some achieve this by modernizing themes; others by deepening psychological exploration.

The Dark Knight from 2008 elevated the crime film by using superhero genre conventions. The Batman/Joker dynamic explores fundamental questions about order and chaos, control and freedom. The film treats the crime narrative seriously enough that it resonates thematically regardless of the superhero framing.

Nightcrawler from 2014 examines contemporary media culture through a crime narrative framework. The protagonist isn't technically a criminal, but his ethical compromises for financial gain reveal how capitalist media logic corrupts values. The film suggests that sensationalizing crime creates the conditions for more crime.

Uncut Gems from 2019 uses crime narrative mechanics to create psychological pressure. The investigation of a diamond heist becomes secondary to the protagonist's psychological deterioration. The film creates tension not through plot revelation but through the relentless pressure of financial desperation.

Contemporary crime films increasingly explore how digital technology changes criminal investigation and law enforcement. The procedural gains new complexity when evidence is digital, when surveillance is ubiquitous, and when criminals can operate globally.

What remains constant across crime cinema from noir through contemporary examples is the basic insight: crime narratives provide frameworks for exploring human nature, moral choices, and social structures. The specific details change, but the fundamental appeal remains.

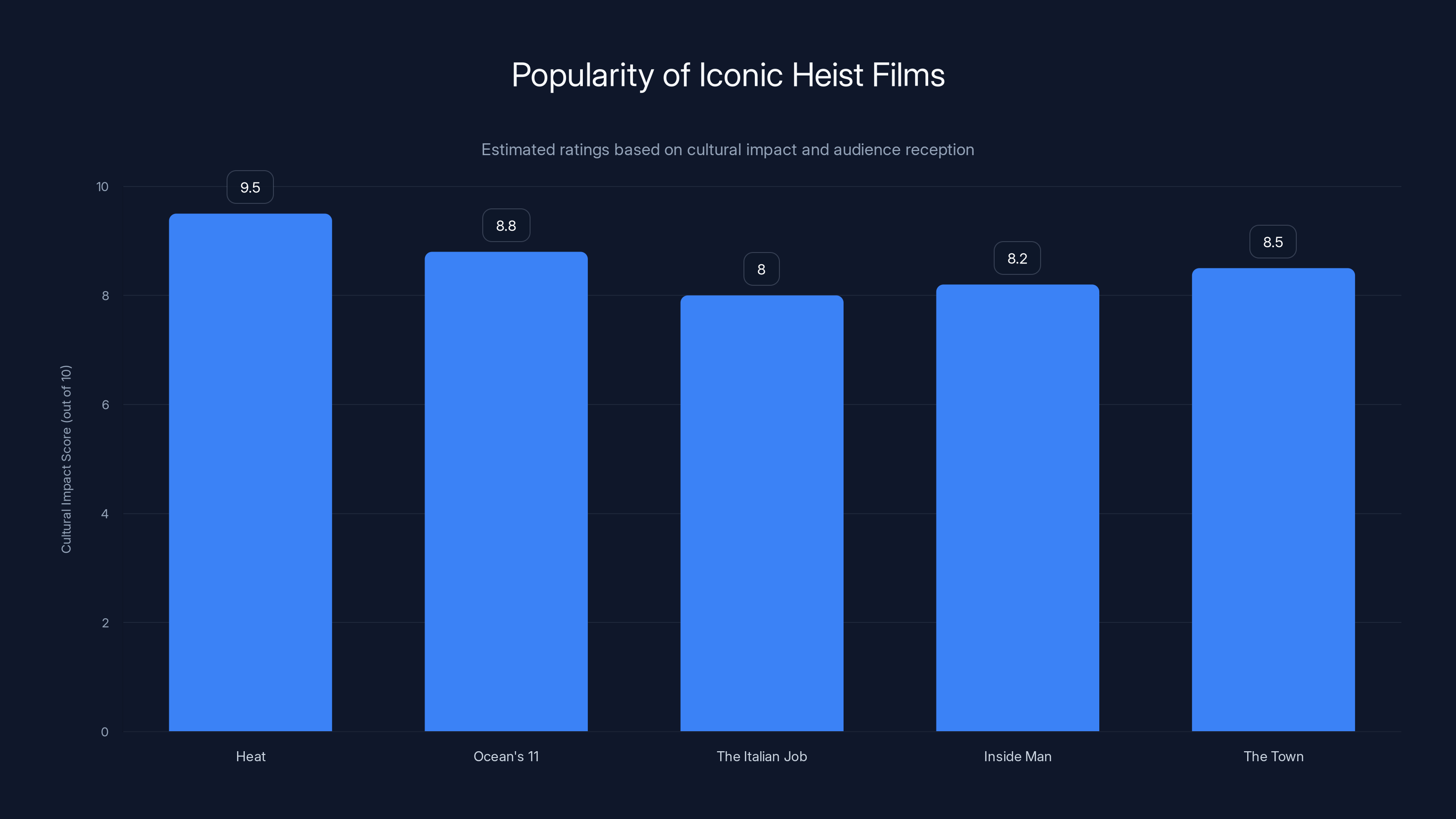

Estimated data shows 'Heat' and 'Ocean's 11' as leading heist films in terms of cultural impact, highlighting their unique approaches to storytelling.

Technical Innovation in Crime Cinema

Essential crime films often pioneer technical approaches that other filmmakers adopt. Innovation isn't decoration—it serves thematic purposes and solves narrative problems.

Cinematography in crime films evolved from noir's high-contrast lighting through various technical innovations. Color cinematography initially seemed to undermine noir's visual language, but cinematographers adapted by using color symbolically. The absence of conventional lighting became a statement rather than limitation.

Editing rhythm in crime films communicates psychological state. A detective's mental clarity might be conveyed through precise, clean cuts. As their mental state deteriorates, editing can become more chaotic, with cuts coming at unexpected moments. The editing becomes a window into consciousness.

Sound design gains particular importance in crime procedurals. The ambient sound of police stations, interrogation rooms, and crime scenes creates psychological atmosphere. Silence becomes pregnant with meaning. A conversation in complete silence produces different psychological effect than identical dialogue with background noise.

Contemporary crime films increasingly use unreliable editing and cinematography to express subjective truth. Rather than showing objective events, they show how characters perceive events. What the audience sees might be accurate or distorted depending on the narrator's mental state or reliability.

Technical innovation serves thematic purposes most effectively when audiences don't consciously notice it. The best technical choices feel inevitable, as though the story could only be told that way. When viewers notice technical innovation as separate from storytelling, it becomes distraction rather than enhancement.

Storytelling Structures That Define Crime Classics

Essential crime films often employ specific narrative structures that have proven endlessly productive for exploring crime and morality.

The dual narrative structure that Heat popularized—parallel investigation and commission of crime—allows audiences to understand both sides symmetrically. Rather than following the investigation's discovery of crime, we see crime and investigation simultaneously. This structure produces specific thematic opportunities: we can compare how professionals operate on both sides of law.

The unreliable narrator structure, inherited from noir tradition, creates psychological depth. When audiences can't trust the narrator's perspective, they must actively evaluate information. This engagement produces more compelling viewing than passive reception of reliable information. Films like Memento use narrative unreliability structurally, fragmenting chronology to express consciousness fragmentation.

The escalation structure treats crime as a progression of moral compromises. Characters make small wrong choices, then slightly larger ones, then truly terrible choices. By the time we reach the climax, characters have already crossed boundaries they couldn't have crossed at the film's beginning. This structure explores how ordinary people become criminals through incremental steps.

The investigation structure reverses conventional narrative expectations by making the investigation the climax rather than the means to climax. The Godfather Part II uses this structure, with the investigation of institutional crime becoming more interesting than the crime itself.

The best crime films often combine multiple structures, creating narrative complexity that mirrors thematic complexity. A single-perspective narrative might be undermined by unreliable narration. A dual-perspective structure might include temporal fragmentation. These layered structures create films that reveal new complexity with repeated viewing.

Character Development in Essential Crime Films

Essential crime films create characters whose development emerges from confrontation with moral choice and systemic pressure. Character arcs in great crime films aren't about growth toward better versions of selves; they're about decline into darker versions.

The protagonist in essential crime films often faces impossible choices where every option involves betrayal or compromise. The character's response to impossibility becomes the story's real content. Do they compromise morality for practical success? Do they maintain principles and suffer consequences? Do they find some creative third way?

The Godfather's Michael Corleone represents the archetype of the decent person corrupted by circumstances and family obligation. Michael's transformation occurs gradually, through scenes that individually might seem like reasonable responses to pressure. Accumulated, these compromises transform him fundamentally.

Anti-hero protagonists became more common as crime cinema matured, reflecting audience sophistication. Rather than identifying with sympathetic protagonists, viewers could identify with or understand morally compromised characters. Breaking Bad pushed anti-hero characterization to extremes, creating a protagonist whose moral decline audiences watched with horror and recognition of its inevitability.

Supporting characters in essential crime films often serve thematic functions beyond plot mechanics. They represent moral positions or values that the protagonist abandons. They show what the protagonist could have been under different circumstances. They embody the systems that corrupt protagonists.

Character relationships drive crime narratives more effectively than plot mechanics alone. The bond between cop and criminal in Heat emerges through parallel scenes showing both characters operating with similar professional values. They're enemies because circumstances place them in opposition, not because they're fundamentally opposed.

Estimated ratings suggest 'The Wire' has the highest impact in portraying institutional corruption, followed closely by 'The Departed' and 'There Will Be Blood'. Estimated data.

Why Crime Stories Endure

Crime narratives have maintained cultural prominence for centuries, through literature, theater, and film. This persistence suggests something fundamental about crime stories' appeal.

Crime provides clear stakes. In crime narratives, consequences are concrete and serious. Characters face actual dangers, real punishments, genuine moral dilemmas. This clarity makes crime stories uniquely suited to exploring philosophical questions that might seem abstract in other contexts.

Crime reveals character under pressure. When people face impossible situations, their values become visible. A character might proclaim principles, but how they behave when those principles threaten their safety or success reveals their actual values. Crime narratives create pressure that exposes character authenticity.

Crime stories explore social power structures. Policing, law enforcement, and criminal organizations all operate through systems of power. Crime narratives examine how these systems work and how individuals navigate them. By exploring criminality, these stories examine society itself.

Crime satisfies curiosity about transgression. Most audiences never experience serious crime, yet curiosity about how people plan and execute crimes seems universal. Crime narratives satisfy this curiosity safely, allowing audiences to experience transgression vicariously.

Crime stories create moral engagement. By depicting characters facing genuine moral choices, crime narratives force audiences to consider what they would do in similar circumstances. This engagement produces emotional investment that simple entertainment can't match.

The most essential crime films recognize that their stories aren't really about crime—crime is the framework for exploring something deeper about human nature, social organization, or moral philosophy. The crime itself becomes metaphorical, a concrete manifestation of abstract themes.

The Influence of Great Crime Films on Contemporary Filmmaking

Working filmmakers study essential crime films the way musicians study jazz standards. They recognize specific techniques, structural approaches, and thematic frameworks that these films established.

When Bart Layton discusses his favorite crime films while developing Crime 101, he's referencing a shared vocabulary with other filmmakers. They understand immediately which films use specific narrative strategies, which films employ particular thematic approaches, which directors solved particular storytelling problems.

Essential crime films become templates. Not in the sense that contemporary filmmakers remake them—obviously they don't—but in the sense that filmmakers reference their solutions to narrative problems. How does a film manage audience sympathy for a criminal protagonist? How does it create tension when the audience knows the outcome? How does it make audiences care about characters whose values they don't share?

The influence often appears as homage or reference rather than direct imitation. A contemporary film might employ lighting techniques reminiscent of noir, or use parallel structure like Heat, or embrace moral ambiguity like The Godfather. These aren't ripoffs; they're demonstrations that the filmmaker understands and respects the tradition they're working within.

Understanding crime film history allows audiences to recognize this dialogue between contemporary and classic films. A film that seems original might be revealing its debts to earlier works. Recognizing these connections deepens appreciation for contemporary filmmaking's sophistication.

Filmmakers also learn from crime films' failures. Understanding why certain approaches haven't worked historically helps contemporary filmmakers avoid similar pitfalls. Why do some morally ambiguous protagonists engage audiences while others alienate them? Why do some narrative structures create momentum while others feel ponderous? Essential crime films teach both through success and failure.

The Role of Crime Films in Streaming and Contemporary Distribution

Streaming platforms have transformed how crime films and series reach audiences. Where theatrical distribution limited audience access, streaming makes extensive crime film catalogs available continuously.

This accessibility has produced unexpected effects on crime cinema itself. Long-form series like The Wire and True Detective borrow from crime film tradition while operating in television's longer-form format. These series can develop complex institutional analysis impossible in two-hour films.

Streaming's algorithmic promotion tends to favor crime content. Platform recommendations push viewers toward crime films and series because these genres maintain high engagement rates. Audiences subscribe to platforms partly for access to extensive crime catalogs.

This ecosystem shift affects what gets financed. Studios are willing to fund crime projects because data suggests audiences will watch them. This creates opportunities for crime films and series that might not have been financed under traditional theatrical distribution.

Conversely, streaming platforms sometimes reduce risk-taking. Theatrical releases can be weird, experimental, or challenging because a limited audience might accept artistic risk. Streaming wants broad appeal, which can push crime content toward safer formulas.

The effect on crime cinema remains unclear. Contemporary crime films and series suggest that streaming's influence has been mixed: more crime content gets made and reaches audiences, but some experimental or challenging projects face pressure toward mainstream appeal.

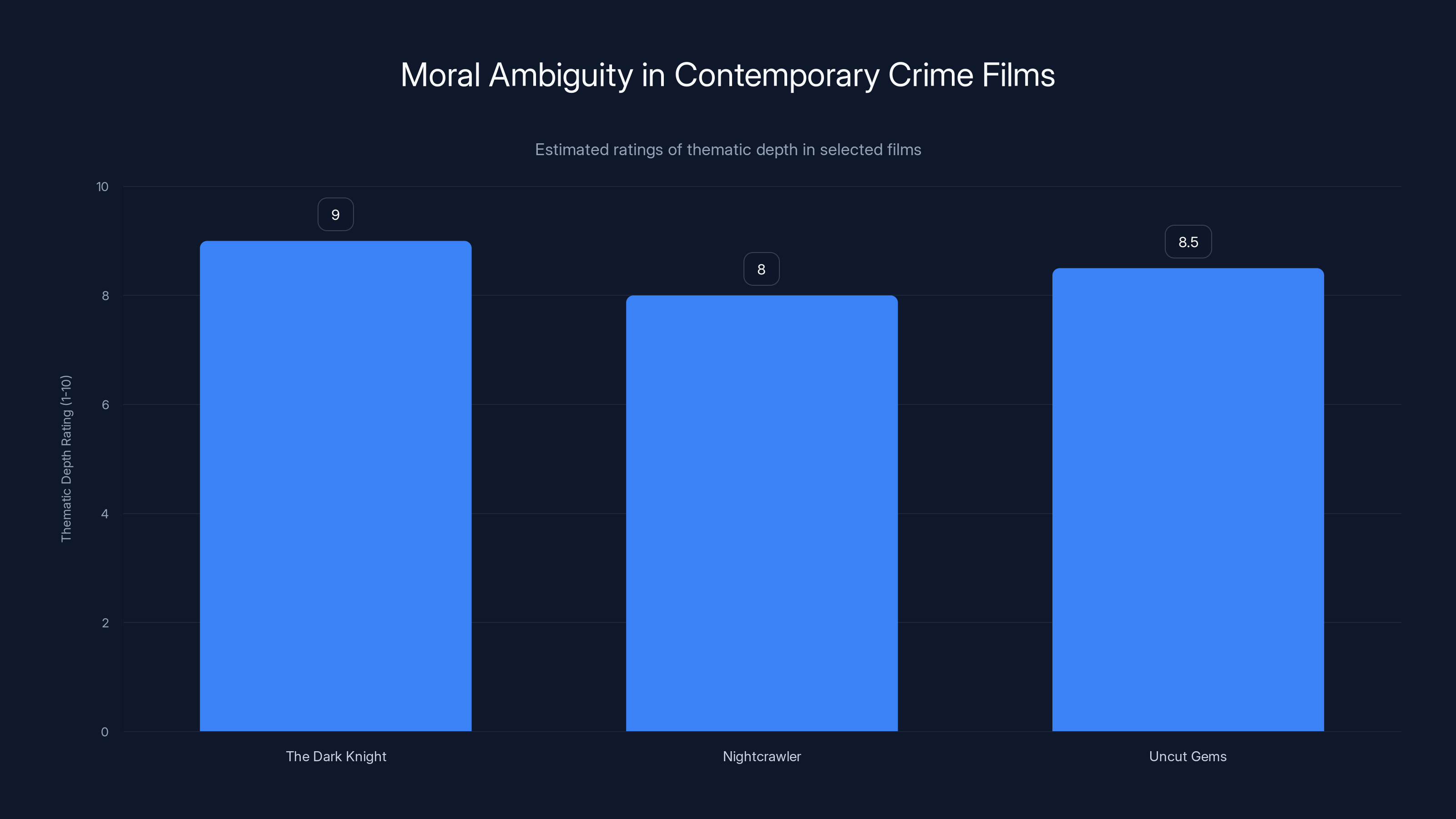

Estimated data shows that contemporary crime films like 'The Dark Knight', 'Nightcrawler', and 'Uncut Gems' are highly rated for their exploration of moral ambiguity and thematic depth.

Analyzing Crime Film Mastery: What Makes Them Work

When serious filmmakers discuss why particular crime films remain endlessly rewatchable, they point to specific elements that work in concert.

First, essential crime films demonstrate complete command of craft. The cinematography, editing, performance, and sound design all operate at high levels. This technical mastery creates foundation that allows thematic exploration. Viewers can focus on ideas because execution is flawless.

Second, essential crime films employ specificity rather than generality. They depict particular institutions, particular characters, particular moral dilemmas rather than generic versions. The specificity creates believability and emotional weight. We believe in these characters because their details feel accurate.

Third, essential crime films resist easy answers. They don't conclude that crime is simple or that moral choices are straightforward. They embrace moral complexity and institutional ambiguity. This intellectual honesty creates lasting resonance.

Fourth, essential crime films trust audiences. They don't over-explain motives or oversimplify themes. They provide sufficient information for engaged viewers to understand the story while leaving room for interpretation and debate.

Fifth, essential crime films understand that crime narratives can explore anything. They use crime framework to examine love, friendship, loyalty, ambition, artistic integrity, parental obligation—every human value and relationship. Crime becomes the lens through which to examine human experience generally.

The most rewatchable crime films reward repeated viewing because each viewing reveals new layers. On first viewing, audiences focus on plot mechanics. On subsequent viewings, they notice thematic patterns, visual symbolism, subtle character moments, structural parallels. The film seems to expand with familiarity rather than contract.

Building Your Crime Film Education

If you want to understand crime cinema deeply enough to recognize why filmmakers like Layton cite particular films as essential, systematic viewing helps.

Start with foundational noir films: The Maltese Falcon, The Asphalt Jungle, Bob le Flambeur. Understanding noir provides context for everything that follows.

Then explore psychological crime dramas: The Godfather, Scarface, The Sting. These films treat crime as window into character and morality.

Study procedural and institutional films: Heat, L.A. Confidential, The Departed. These show how investigation and systems create narrative momentum.

Explore international approaches: Memories of Murder, Killing Zoe, City of God. Different cultural perspectives expand crime film vocabulary.

Add contemporary films: Nightcrawler, Uncut Gems, The Harder They Fall. Contemporary films show how crime cinema evolves.

Watch television series that function as extended crime narratives: The Wire, Breaking Bad, True Detective. These show what's possible with longer narrative formats.

When rewatching films you know, pay attention to specific technical choices. How is a scene lit? Why does a particular cut occur at that moment? How does dialogue reveal character? This active engagement with craft develops understanding that passive viewing doesn't produce.

The Future of Crime Cinema

What directions might crime cinema take as technology evolves and social concerns shift?

Cybercrimes and digital-era criminal activity offer new narrative territory. How do you create visual excitement from hackers stealing data? How do you make digital crime feel concrete and consequential? Contemporary films increasingly tackle these questions, though the solutions remain experimental.

Artificial intelligence introduces new moral and narrative possibilities. What happens when criminal investigation relies on AI prediction? When surveillance operates at unprecedented scale? When algorithms determine policing priorities? These questions point toward crime narratives that engage with genuine contemporary concerns.

Global crime networks produce different narrative challenges than local criminal organizations. International organized crime, human trafficking, and transnational operations suggest crime narratives that cross national boundaries. Films must balance depicting global systems while maintaining character focus.

Social justice movements influence how crime narratives engage with law enforcement. Contemporary audiences increasingly expect crime films to examine how policing operates in practice, how systemic racism corrupts institutions, how individual officers navigate corrupt systems. Crime films increasingly reflect these concerns.

Streaming's longer-form format might continue to attract the most ambitious crime storytelling. Film length constraints limit institutional analysis and character development that longer series provide. The most challenging and complex crime narratives might increasingly appear as series rather than films.

Regardless of specific directions, the fundamental appeal of crime narratives will likely persist. Crime provides frameworks for exploring moral complexity, examining systems, understanding character under pressure. As long as audiences care about those questions, crime stories will matter.

What Makes Crime 101 Part of the Conversation

Bart Layton's Crime 101 series fits within the tradition of crime storytelling that these classic films established. The series examines real historical crimes through dramatized narrative, combining documentary's factual foundation with dramatic cinema's narrative power.

Layton's approach reflects lessons from the crime films he admires. The series treats crime investigation as dramatic material, similar to procedural films. It examines institutional context and systemic factors alongside individual criminal psychology. It trusts audiences to engage with moral complexity rather than oversimplifying.

The casting of Chris Hemsworth in a crime series represents interesting genre positioning. Hemsworth comes from action and superhero cinema, but Crime 101 positions him in a crime narrative context where physical prowess matters less than psychological insight.

By discussing his favorite crime films, Layton signals where his influences come from and what elements he values in crime storytelling. He's not trying to reinvent crime cinema; he's working within traditions established by the films he cites, advancing those traditions with contemporary sensibilities.

The conversation between contemporary crime creators and classic crime films suggests that the genre continues evolving while respecting foundational accomplishments. New crime films don't replace earlier masterpieces; they dialogue with them, learning from their successes and building on established foundations.

FAQ

What defines a classic crime film?

Classic crime films combine compelling storytelling with thematic depth that explores human nature, morality, or social systems. They work on multiple levels simultaneously: as engaging narratives and as philosophical investigations of crime, justice, and transgression. Technical excellence, character development, and structural sophistication distinguish classics from competent but forgettable crime entertainments.

Why are film noir crime films still considered essential?

Film noir established visual and narrative language that subsequent filmmakers built upon. Noir films pioneered techniques for conveying psychological darkness through cinematography, developed the unreliable narrator structure, and treated moral ambiguity as thematic center rather than narrative weakness. Even contemporary crime films echo noir's visual and thematic approaches, making noir understanding essential for appreciating crime cinema generally.

How do psychological crime dramas differ from procedural crime films?

Psychological crime dramas focus on character motivation, moral psychology, and how pressures corrupt people. Procedural crime films emphasize investigation methods, institutional operations, and how systems work. Neither approach is superior—they're complementary perspectives on crime and criminal investigation. The best crime films often incorporate both, using procedural detail to reveal character psychology.

What role does moral ambiguity play in great crime films?

Moral ambiguity makes crime narratives intellectually engaging. When films present simple good-versus-evil scenarios, audiences passively receive predetermined conclusions. When films embrace moral complexity, audiences must actively evaluate situations and characters. This engagement produces deeper emotional investment and more lasting impact. The most rewatchable crime films reward repeated viewing partly because moral ambiguities reveal new dimensions on subsequent viewings.

How has crime cinema influenced television storytelling?

Long-form television series borrowed from crime film traditions while exploiting television's ability to develop institutional analysis across many episodes. Shows like The Wire take the procedural approach established by crime films and extend it across seasons, examining how institutions operate systemically. Television's format allows exploration of criminal ecosystems and institutional corruption that feature-length films cannot fully develop.

Why do filmmakers continue studying classic crime films?

Classic crime films represent solutions to narrative problems that contemporary filmmakers face. How do you maintain audience sympathy for criminal protagonists? How do you create tension when audiences know the ending? How do you structure complex institutional narratives? Classic films provide examples of these techniques executed at high levels. Additionally, understanding crime film history allows contemporary filmmakers to work within traditions they respect while advancing those traditions.

What makes crime stories effective for exploring themes beyond crime itself?

Crime provides high stakes that make abstract themes concrete. Questions about loyalty, ambition, morality, and power become visceral when lives and freedom hang in balance. Crime narratives can examine institutional corruption, personal integrity, family obligation, or artistic compromise using crime framework. The clarity of stakes makes crime particularly effective for exploring philosophical questions that might seem abstract in other genres.

How do different cultures approach crime storytelling differently?

Different cultures emphasize different aspects of crime narratives based on their values and institutional contexts. American noir emerged from Depression-era cynicism and postwar disillusionment. Scandinavian crime fiction emphasizes social alienation and systemic inequality. Japanese crime narratives focus on honor and shame rather than law and order. South Korean crime films examine institutional failure and authoritarian systems. These different cultural perspectives expand what crime narratives can explore and challenge American crime film conventions.

What technical innovations did crime films pioneer?

Crime films pioneered high-contrast cinematography techniques, developed editing rhythms that communicate psychological state, and experimented with sound design for psychological effect. Noir films established lighting conventions that persist in contemporary cinematography. Crime procedurals developed visual language for making investigation visually engaging. Contemporary crime films continue experimenting with subjective cinematography and unreliable editing to express character perspective rather than objective truth.

How should someone approach building knowledge of crime cinema?

Systematic viewing helps. Start with foundational films that established crime genre conventions: noir classics, then psychological crime dramas, then procedurals and institutional crime narratives. Watch films from different cultures to understand varied approaches. Watch both acknowledged masterpieces and interesting failures, as both teach. Keep notes about techniques that stand out and themes that recur. Watch films multiple times, focusing on different elements each viewing. This active, systematic engagement develops understanding far more effectively than passive viewing of random crime films.

Conclusion: The Enduring Brilliance of Crime Cinema

When filmmakers like Bart Layton discuss their favorite crime movies as "endlessly brilliant and rewatchable," they're recognizing something fundamental about crime cinema's artistic potential. Crime films don't just entertain; they explore the depths of human nature and social organization in ways few other genres attempt.

The tradition Layton works within stretches from film noir's visual innovations through psychological crime dramas' character exploration through contemporary examinations of institutional corruption and digital-age criminality. Each era's crime films reflect their moment's concerns while drawing from established traditions. The best contemporary crime films don't reject their predecessors; they build on foundations those films established.

Understanding crime cinema requires recognizing that great crime films work on multiple levels. They succeed as plot-driven entertainments while simultaneously functioning as philosophical investigations. They engage audiences emotionally while challenging them intellectually. They're rewatchable because each viewing reveals new layers: thematic patterns invisible on first watching, technical choices supporting thematic content, character moments gaining significance through repetition.

The essential crime films discussed here remain vital not through nostalgia or historical importance alone, but because they represent crime storytelling at its most sophisticated. They demonstrate how narrative form, visual technique, character development, and thematic depth can work in concert to create experiences that linger in memory and reward repeated engagement.

For anyone seeking to understand contemporary crime cinema, whether as filmmaker or viewer, studying these foundations proves invaluable. They provide vocabulary for discussing crime narrative techniques, examples of problems solved through creative storytelling, and models of how crime can serve as framework for exploring broader human concerns.

Layton's Crime 101 and other contemporary crime projects emerge from this tradition of excellence. Understanding that tradition deepens appreciation for how contemporary work both respects and advances established conventions. The conversation between contemporary and classic crime cinema continues because the fundamental questions crime stories explore remain perpetually vital: What drives people to transgression? How do systems corrupt individuals? What does justice actually mean? How do we maintain integrity in corrupt environments?

These questions ensure that crime cinema will continue evolving and engaging audiences for decades to come. As long as audiences care about moral complexity, institutional analysis, and character psychology, crime films will matter. The masterpieces discussed here provide compass points for navigating where crime cinema has been and suggesting where it might go. They remain not just historical artifacts but living inspiration for contemporary storytellers seeking to engage audiences with narratives that entertain, challenge, and endure.

Key Takeaways

- Essential crime films explore human nature and morality through crime narrative frameworks rather than focusing purely on plot mechanics

- Film noir established visual and narrative language that contemporary crime cinema still references and builds upon

- Psychological crime dramas treat crime as window into character motivation while procedurals emphasize investigation methods and institutional operations

- The best crime films work on multiple levels: as entertainment, character study, institutional analysis, and philosophical investigation

- International crime films bring different cultural perspectives that expand what crime narratives can explore beyond American genre conventions

- Contemporary crime films increasingly examine digital-age concerns, media systems, and global criminal networks within established genre traditions

Related Articles

- Chris Hemsworth Crime 101 Stunts: Director Reveals Truth [2025]

- School Spirits Season 3 Episode 4: Why It's 'So Unfamiliar' [2025]

- Bridgerton Season 4 Part 1 Review: Why Benedict Steals the Show [2025]

- Life is Strange Reunion: Max and Chloe's Emotional Conclusion [2025]

- Prime Video's Steal: A Thrilling Heist That Delivers [2025]

- Movies to Watch Before The Bride Release: Ultimate Guide [2025]

![Best Crime Movies of All Time: Directors' Essential Picks [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/best-crime-movies-of-all-time-directors-essential-picks-2025/image-1-1770478575087.jpg)