The Year Cybersecurity Reporting Changed Everything

There's something uniquely satisfying about year-end lists. They create space to breathe, step back, and ask: what actually mattered? In cybersecurity, 2025 wasn't defined by flashy zero-day exploits or billion-dollar ransomware attacks splashed across headlines. Instead, the year's most consequential stories came from journalists doing something harder than chasing breaking news: they did the investigative work.

The best cybersecurity journalism in 2025 came from reporters who spent months cultivating sources, following digital breadcrumbs, or simply being in the right place at the right time to document how institutions fail. Some of these stories exposed government agencies buying bulk access to flight data without warrants. Others revealed how senior U.S. officials were casually discussing military operations in a badly configured messaging app. A few tackled the deeply human costs of operating as a cybersecurity source in countries where that work can kill you.

This isn't a definitive list. Cybersecurity now has dozens of English-language journalists publishing great work every single week. Outlets ranging from independent media organizations to major newsrooms are covering surveillance, privacy, hacking, and digital rights with real depth. What follows is a curated collection of the stories that stood out, that made us think, that changed something, or that simply told us something we needed to know. These are the pieces we wish we'd broken ourselves.

The Personal Cost of Being a Cybersecurity Source

When a Hacker Becomes Your Source, and Then He Becomes a Memory

Shane Harris of The Atlantic spent months corresponding with someone claiming to be a senior Iranian hacker. The level of access and operational detail the hacker provided seemed almost too good to be true. Harris was skeptical at first, naturally. When someone online claims to have orchestrated major cyberattacks against critical infrastructure, your journalistic instincts should scream "verify everything."

But Harris did the work. He verified pieces of the story. He built rapport with the source. The hacker eventually revealed his real name. Through careful investigation, Harris pieced together a history that somehow exceeded what his source had initially claimed. The operations were real. The access was genuine. The person existed.

Then the hacker died. Harris transformed what could have been a cautionary tale about misinformation into something more profound. He explored not just the story the hacker had told him, but the real story behind it. The piece became a masterclass in what cybersecurity reporting actually looks like when you're dealing with sources who have real stakes in the game.

This story mattered because it pulled back the curtain on something journalists rarely discuss openly: the danger involved in reporting on hacking. Your sources in this space often come from countries with hostile relationships to the West. They're operating under conditions where getting caught can mean imprisonment or worse. When a reporter cultivates a source, they're not just asking someone to share information. They're asking them to take real risk.

The Ethical Complexity of Reporting from Inside Authoritarian Regimes

Harris's story also illustrated a gap in how we discuss cybersecurity. Most coverage treats hacking as a technical problem, a policy problem, or a business problem. What it rarely addresses is the human reality. The people committing cyberattacks are often individuals operating under state pressure, living under surveillance themselves, making impossible choices about what risks they'll take.

By treating his source with dignity, by taking the time to understand not just what happened but why it happened, Harris elevated the entire conversation. This is investigative work that changes how we understand the ecosystem. A hacker isn't just a user account carrying out commands. The person behind that account has a story, has motivations, has fears.

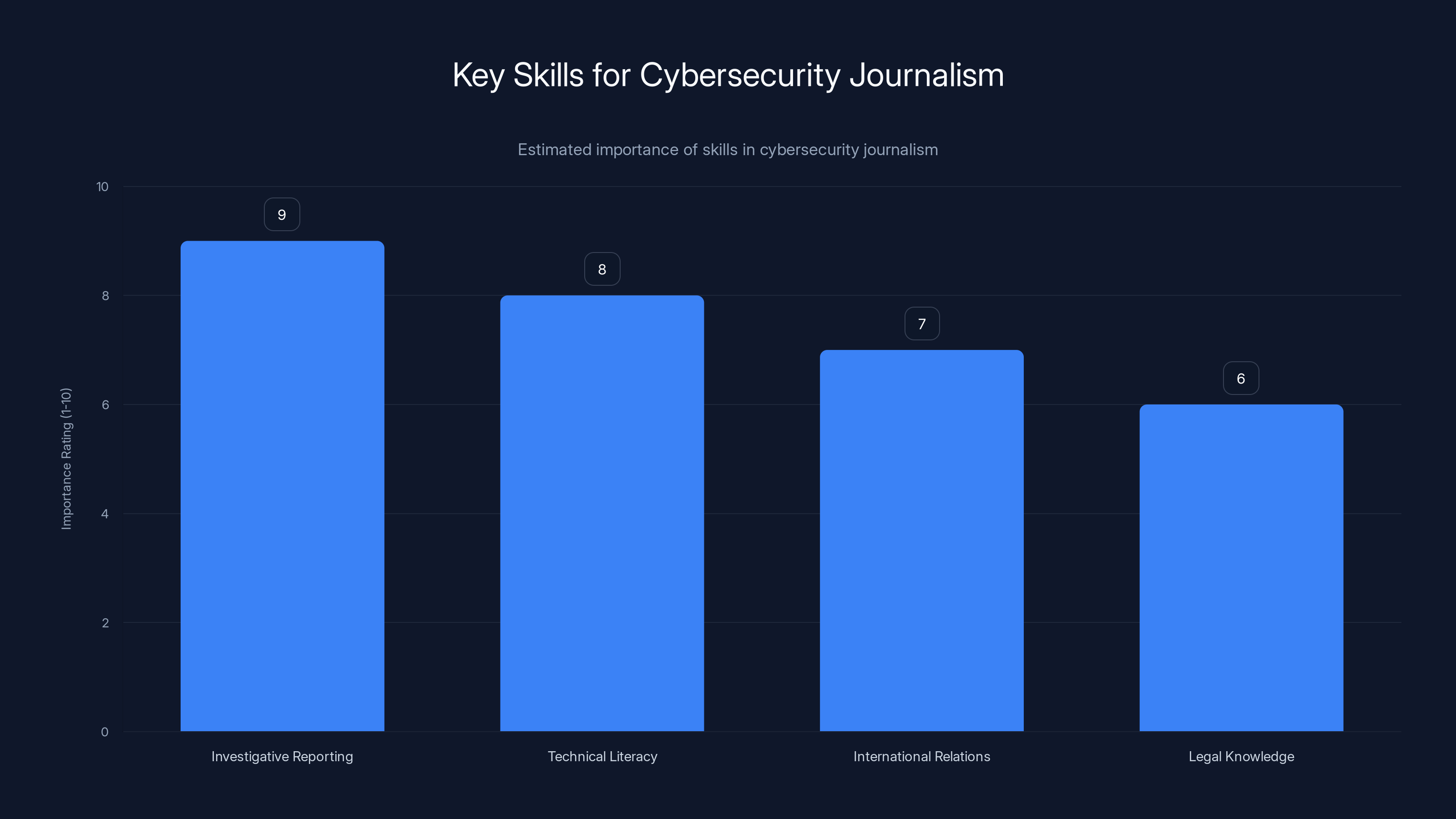

The piece also demonstrated why cybersecurity reporting requires different skills than technology coverage generally. You need technical literacy, obviously. But you also need the patience of a traditional investigative journalist. You need to be comfortable with ambiguity. You need to understand that sometimes the most important story is the one you can't fully publish, the sources you have to protect, the details you have to obscure.

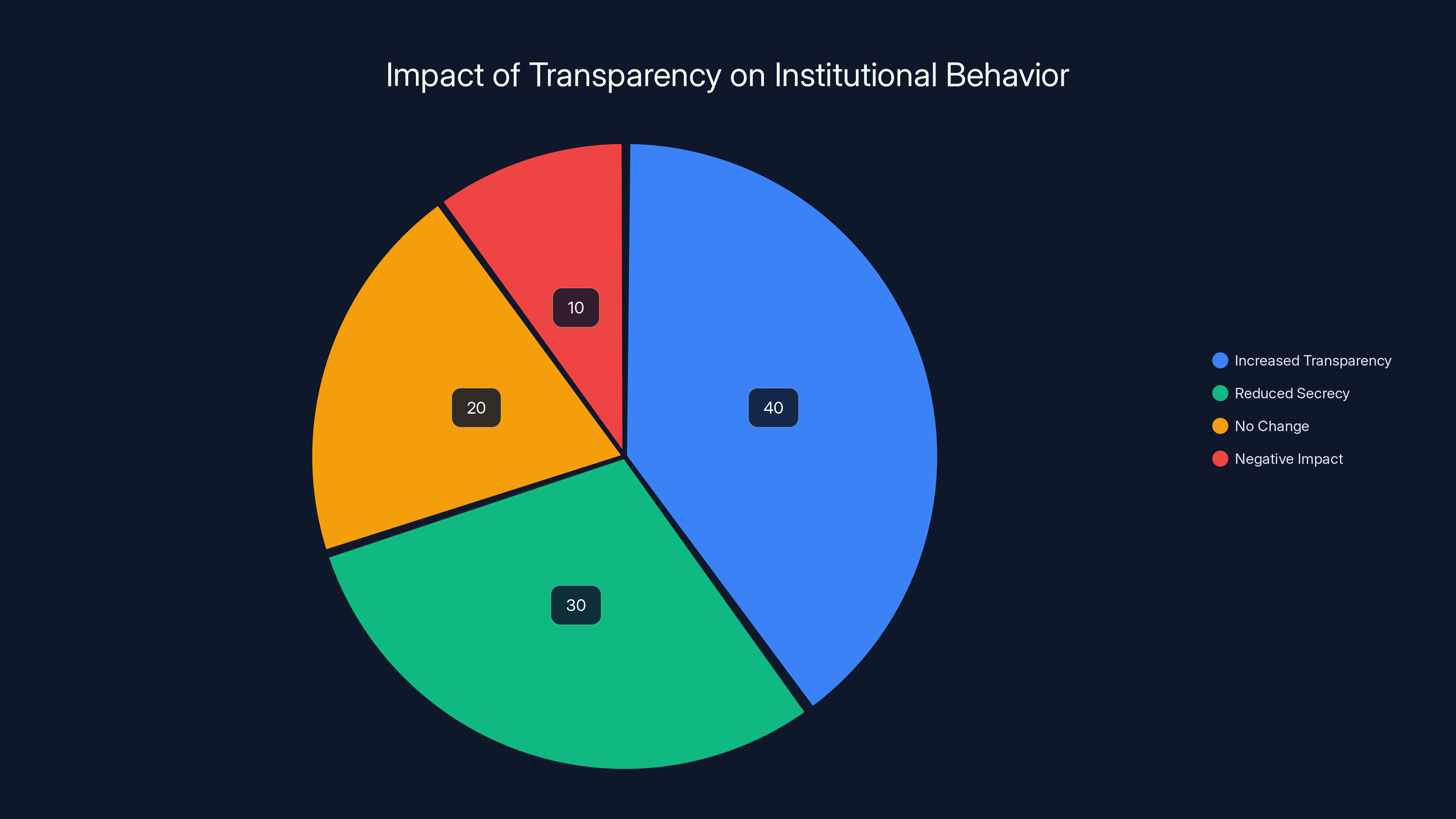

Estimated data suggests that increased transparency and reduced secrecy are major outcomes of investigative journalism, influencing institutional behavior significantly.

When Governments Try to Build Backdoors in Secret

The U.K. Court Order That Almost Nobody Knew About

In January 2025, the British government issued Apple with something unprecedented: a secret court order demanding that the company build a backdoor into its encryption systems. The order came with a gag order so restrictive that Apple itself couldn't legally discuss it publicly. If the demand had succeeded without public scrutiny, users worldwide would have faced degraded privacy protections without ever knowing.

The Washington Post broke this story. The reporters involved traced what happened, understood the legal mechanisms at play, and published before the full implications could be buried in classified documents. Because of their reporting, the secret order became a matter of public record. Because it became public, it became controversial. Because it became controversial, the U.K. government ultimately withdrew the demand.

That's the power of investigative journalism in a surveillance context. A single story changed government policy. A single story protected the privacy of potentially billions of people worldwide.

Why This Story Mattered for Tech Policy Everywhere

For a decade, major technology companies have positioned themselves as defending user privacy from government overreach. They've spent billions on encryption technology that they themselves can't bypass. This creates a structural problem for law enforcement: when you design systems you can't crack, you also create systems that criminals can use safely.

Governments have responded by pushing for backdoors, backdoor access, or technical solutions that would let law enforcement access encrypted data. The U.K.'s secret court order represented one potential approach: compel a company to build the capability, do it in secret, and move forward before anyone can object.

The Washington Post's reporting exposed this strategy to public scrutiny. It forced a conversation about whether this is how we want surveillance and privacy decisions to be made. It raised the question of whether a secret court order is even democratic governance. The backlash that followed showed that the public cares about these issues, even when the government assumes nobody's watching.

How Gag Orders Almost Succeeded

What made this story remarkable wasn't just the content. It was that it almost didn't happen. Gag orders are designed to prevent exactly this: public scrutiny of government demands. A company like Apple might comply with the order, quietly build the backdoor, and users would never know their encryption had been compromised.

The Washington Post's reporters found the story despite those obstacles. They tracked down sources willing to discuss what had happened. They built a case thorough enough that they could publish with confidence. And when they did, it changed the outcome.

This is what investigative journalism looks like in the surveillance age. It's not just reporting on what happened. It's actively working against the structures that prevent information from becoming public.

Cybersecurity journalism demands a unique blend of skills, with investigative reporting being the most critical. Estimated data based on typical skill requirements.

The Government That Can't Keep a Secret

When Senior Officials Accidentally Broadcast War Plans

Jeffrey Goldberg, editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, received a message one day adding him to a Signal chat. He wasn't supposed to be there. The chat included senior U.S. government officials discussing where military forces should deploy, what operations were planned, and how military strategy should unfold. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth had somehow added Goldberg to the group, probably by accident.

Goldberg's first instinct was to verify. Was this real? Were these actually government officials discussing actual military plans? He watched as the officials messaged about bombing coordinates and military operations. Then he watched as news reports came in about missiles hitting targets in the exact locations the officials had discussed. The confirmation was unsettling: these were real officials discussing real operations in real time.

Goldberg made the journalistic call to publish. What followed was a months-long investigation into what was soon called the biggest operational security failure in government history. The incident revealed not just that the government's operational security was terrible, but how terrible. Officials were using a knockoff Signal clone. Messages were unencrypted in some cases. The entire communications infrastructure was more fragile than anyone had realized.

What This Story Said About Modern Government

At one level, this story was simple: the government messed up, Goldberg documented it, and the government's security practices faced scrutiny. At another level, it was profoundly unsettling. It suggested that the highest-level military planning was happening on consumer messaging apps without adequate security. It suggested that the people running the military didn't understand their own communications infrastructure.

The operational security failure wasn't just embarrassing. It was a national security problem. If Goldberg had been working for a foreign intelligence service, he would have had real-time access to U.S. military planning. A commercial data broker could potentially have intercepted the same traffic.

What the incident revealed was a gap between the government's assumed security and its actual security. Officials presumably believed they were communicating securely. They weren't. This kind of gap is dangerous. It's the kind of thing that leads to actual strategic disadvantage.

The Broader Pattern of Security Theater

The Signal clone situation was particularly revealing. Security tools only work if people use them correctly. This incident suggested that senior government officials don't use security tools correctly, and that the infrastructure supporting them doesn't enforce correct usage. Instead of creating conditions where secure communication was the default, the government created conditions where officials could easily make catastrophic mistakes.

This is a pattern worth understanding more broadly. When security is optional, when it requires extra effort or special knowledge, people don't use it correctly. The government's approach to operational security treats it as an afterthought, something people should be doing but something they can ignore if they're busy or distracted.

Goldberg's reporting forced the government to confront this problem in public. It created pressure to improve operational security practices. It changed the conversation about how senior officials should be communicating.

Finding the Person Behind the Handle

How Brian Krebs Identified a Teenage Cybercriminal

Brian Krebs has spent years following online breadcrumbs. He develops sources in the cybercriminal underground. He traces financial transactions, analyzes code, and works backward from public evidence to identify people operating pseudonymously. It's detective work, but conducted in digital spaces where one mistake can compromise the investigation.

In 2025, Krebs identified "Rey," an administrator in the notorious cybercriminal group known as Scattered LAPSUS$ Hunters. The group had claimed responsibility for major breaches. They had access to significant systems. And Rey was apparently operating the group, making strategic decisions, and coordinating activities.

Krebs traced the digital evidence methodically. He built a picture of who this person was. Eventually, he made contact with someone close to the hacker, then with the hacker himself. The conversation was remarkable: the hacker confessed to his crimes and claimed he was trying to escape the cybercriminal life.

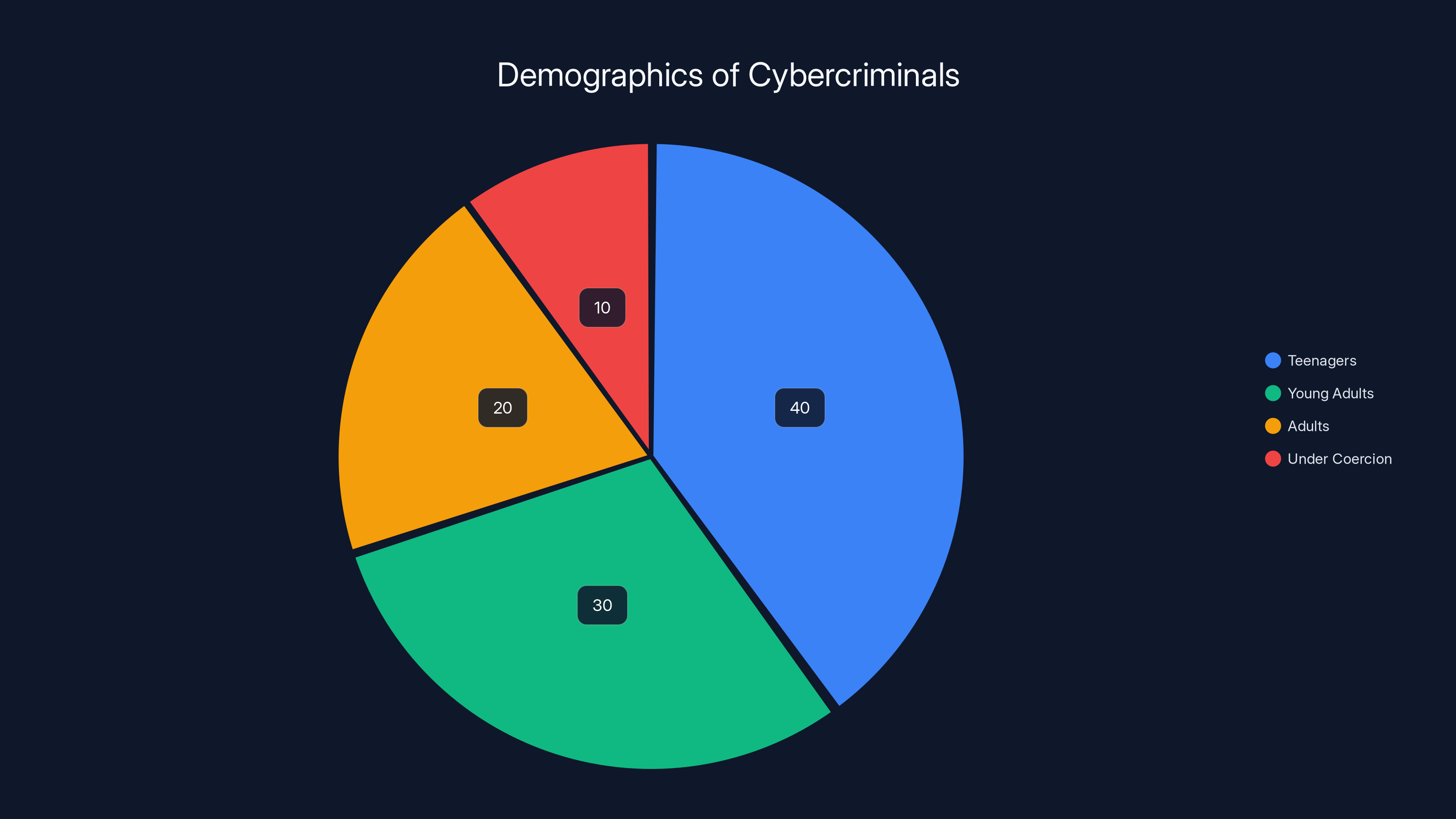

This story revealed something important about cybercrime that often gets missed in coverage: it's often conducted by people who are young, who are sometimes acting under external pressure, and who sometimes want a way out. The stereotypical image of cybercriminals as hardened career criminals doesn't match reality. Some are teenagers making catastrophic choices. Some operate under surveillance or coercion from powerful actors. Some want to quit but don't see a path to do so.

The Investigation Technique That Matters

Krebs's reporting method is instructive. He didn't rely on leaked databases or lucky breaks. He used public information, analytical thinking, and patience. He talked to people who had information. He built a case gradually, verifying each piece before moving forward.

This approach works in cybersecurity reporting, but it requires time. You can't rush this work. You have to double-check everything. You have to be ready to abandon threads that don't pan out. You have to develop relationships with people who understand the online spaces where cybercriminals operate.

What Krebs did was take what could have been a simple "here's who the hacker is" story and transform it into something more complex. He treated his source as a human being making choices, not as a criminal to be exposed. This created space for the hacker to be honest about his situation, to explain his motivations, and potentially to change trajectory.

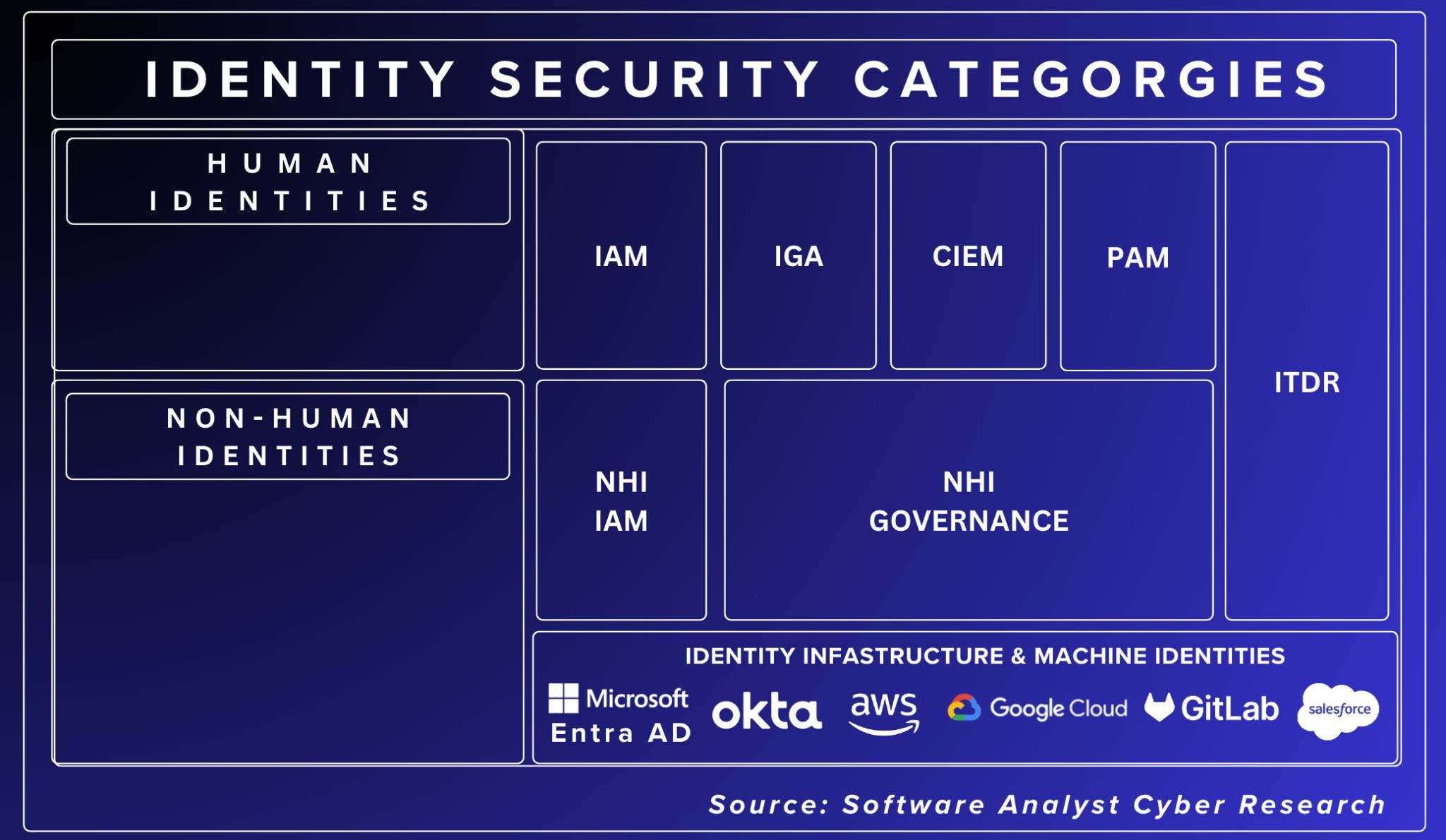

Why Identity Matters in Cybercrime Reporting

There's a question worth asking: why does it matter who these people are? In part, it matters because anonymity enables crime. When hackers believe they can operate without being identified, they feel free to act without consequences. Reporting that identifies actual people creates deterrence. It shows that anonymity is not absolute.

But it also matters for other reasons. Cybercriminals are often portrayed as impossibly sophisticated, as near-superhuman in their technical abilities. When a reporter identifies that the administrator of a major cybercriminal group is a teenager in Jordan, it shifts the narrative. The threat is real, but it's not some faceless digital entity. It's a person making choices.

This distinction matters for policy. If you believe that cybercriminals are always brilliant technical specialists, you approach law enforcement differently than if you understand that they're often young people who got involved in the wrong activities. Prevention becomes possible. Rehabilitation becomes possible.

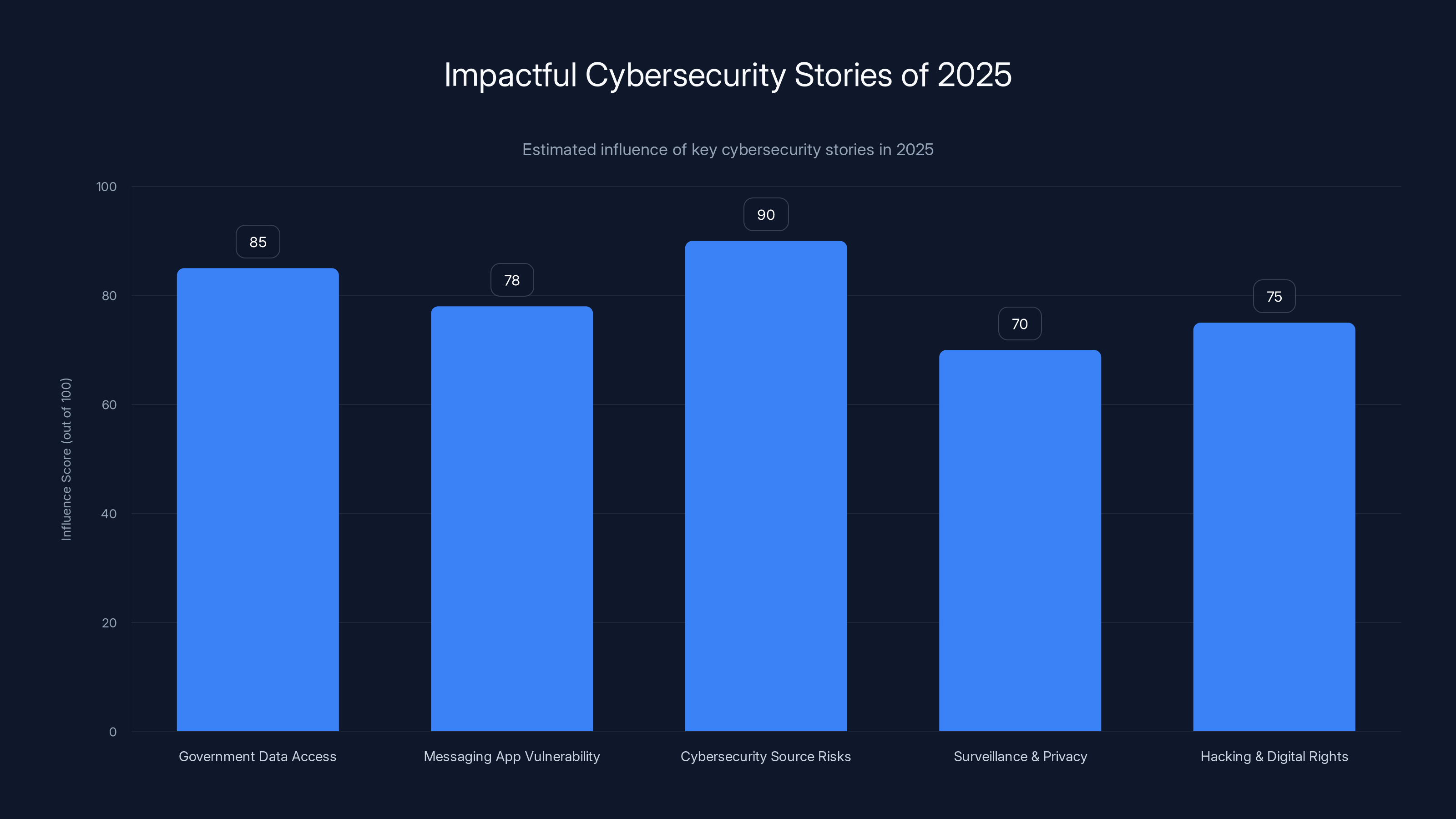

In 2025, investigative journalism in cybersecurity highlighted critical issues, with stories on cybersecurity source risks and government data access having the highest impact. (Estimated data)

When Data Brokers Enable Mass Surveillance

How Airlines Accidentally Built a Surveillance System for the Government

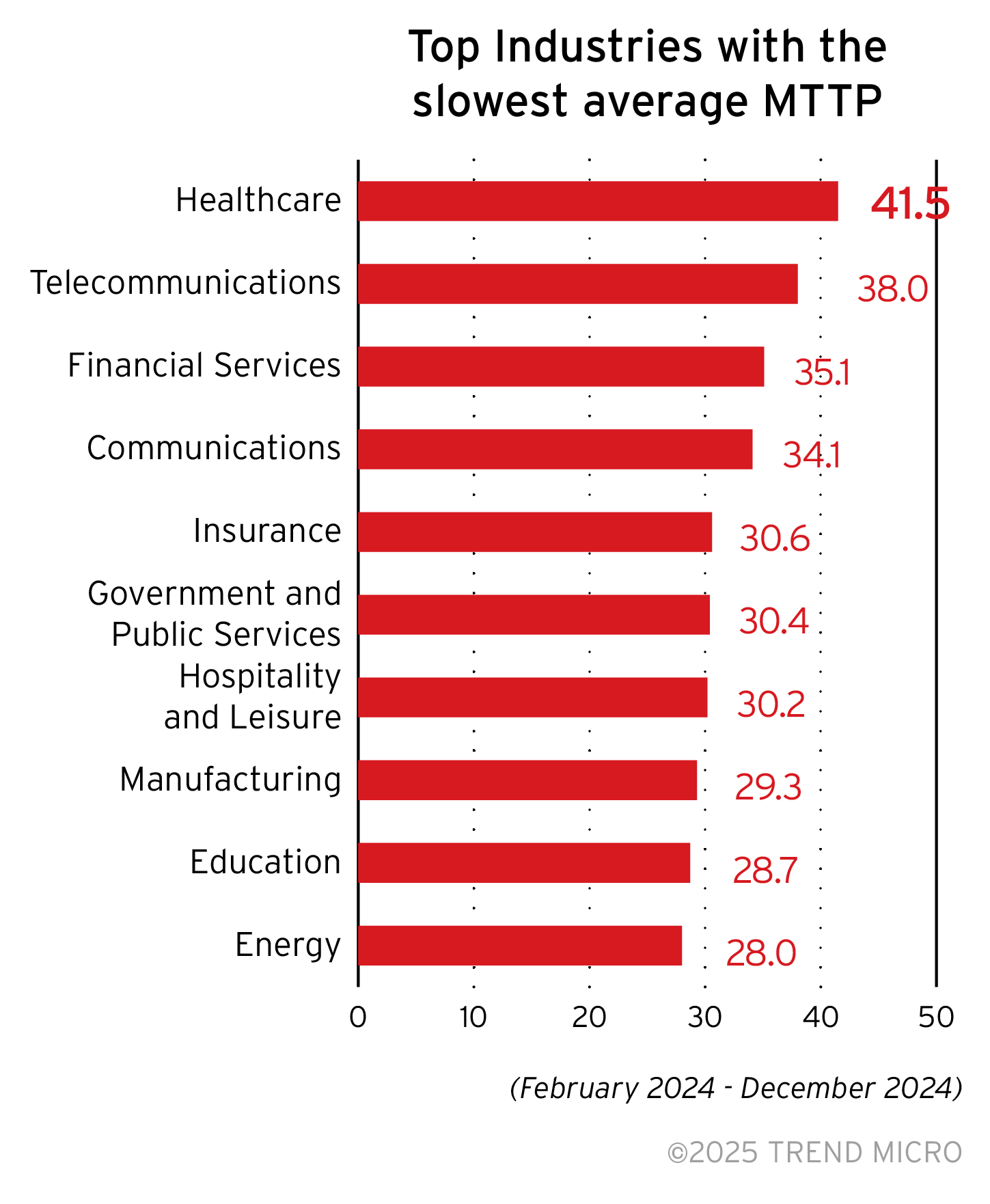

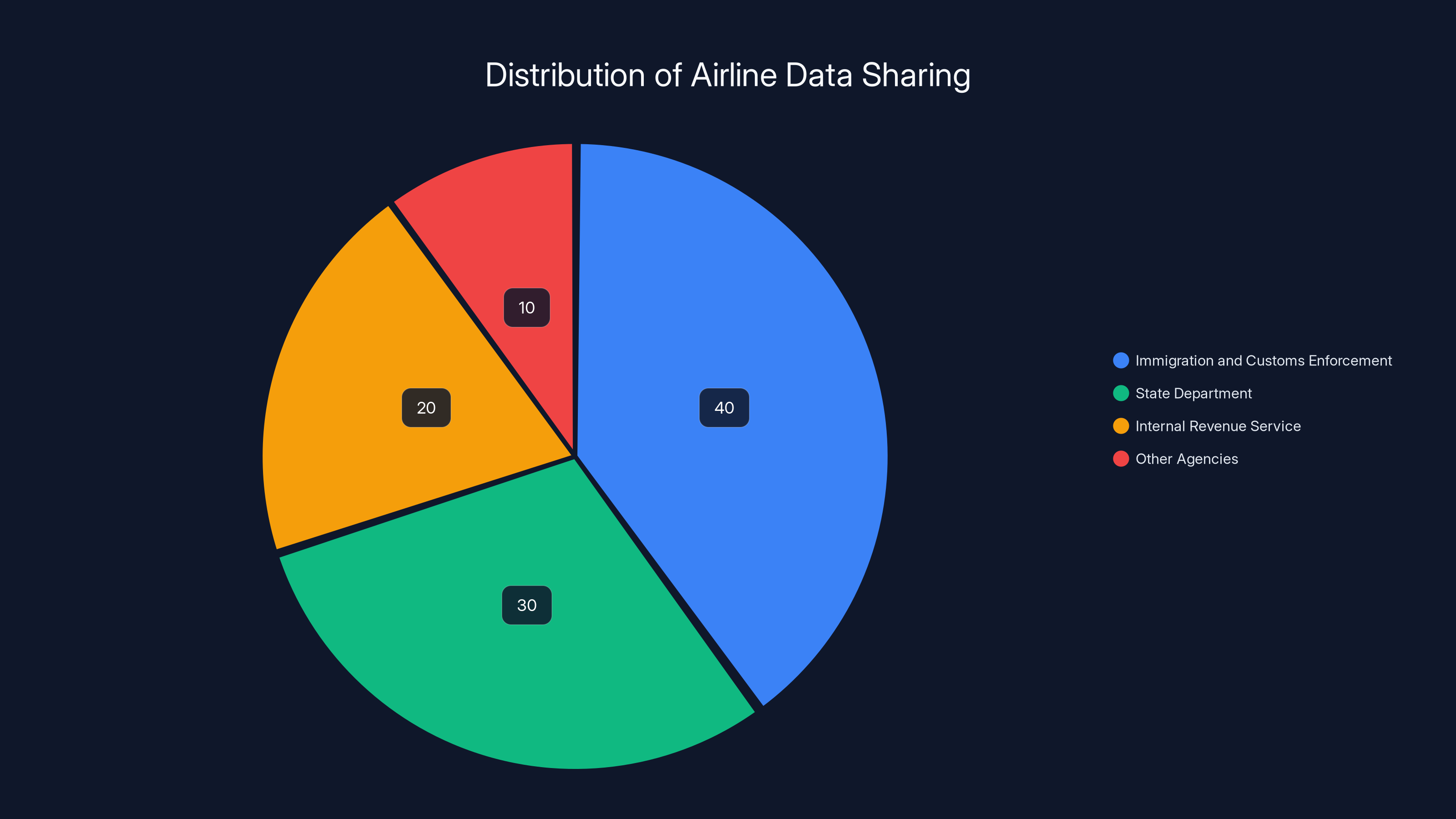

404 Media, an independent publication founded by journalists previously at Vice, broke one of the most consequential stories of 2025: the airline industry's secret data sharing arrangement with federal agencies. A data broker set up by the airline industry, called the Airlines Reporting Corporation and owned by United, American, Delta, Southwest, Jet Blue, and others, had been selling access to five billion flight records.

These records included passenger names, financial information, and travel itineraries. Federal agencies including Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the State Department, and the Internal Revenue Service were buying access. They could track where ordinary Americans were traveling, and they could do it without a warrant.

The surveillance system had been operating in plain sight. Airlines reported passenger information for legitimate regulatory reasons. The data broker consolidated that information. Government agencies purchased access. Nobody involved seemed to question whether this was appropriate.

404 Media's reporting exposed the system. It showed how a convenience for the airline industry had created a surveillance infrastructure that affected every traveler. Because the story became public, pressure mounted on the airlines. The Airlines Reporting Corporation announced it would shut down the warrantless data access program.

The Architecture of Mass Surveillance

What made this story so significant was that it revealed how surveillance often happens: not through dramatic hacks or government overreach, but through incremental business arrangements that individually seem reasonable but collectively create something troubling.

The airlines' need to share passenger information is legitimate. They need to coordinate across systems. Regulators need to enforce rules. Data consolidation serves business purposes. None of this individually is wrong. But when you consolidate all of that data and then sell access to law enforcement without warrant requirements, you've built a mass surveillance system.

This is the surveillance pattern of 2025. It doesn't require new technology necessarily. It doesn't require government agencies to hack anything. It requires data brokers, intermediaries, and institutional arrangements that treat personal information as a commodity.

The Power of Independent Media

404 Media accomplished something remarkable. Founded by journalists who wanted to do independent investigative work, the organization demonstrated that you don't need the resources of a legacy news organization to break stories that change government policy. You need reporters willing to do the work, sources willing to trust them, and an audience that cares about the story.

The airlines shutting down the program demonstrates the power of public reporting. The surveillance system was legal. The airlines weren't breaking any laws. Federal agencies weren't doing anything unauthorized. But when the public knew about it, when journalists exposed how it worked, the political calculation changed. What had seemed like a normal business arrangement became publicly unacceptable.

Understanding the Broader Reporting Landscape

Why Cybersecurity Journalism Requires Different Skills

Cybersecurity journalism isn't just technology reporting. It's not just policy analysis. The best cybersecurity stories require investigative skills, technical literacy, understanding of international relations, and the patience to build complex narratives from incomplete information.

A reporter covering cybersecurity needs to understand how systems work. They need to understand the forensic analysis of attack patterns. They need to understand code. But they also need to be good at traditional reporting: cultivating sources, verifying information, understanding context, and telling stories in ways that matter to readers.

These skills are in short supply. There are probably fewer than 100 reporters in the English-speaking world who do serious, investigative cybersecurity journalism. Everyone else is reporting on the conclusions that these reporters reach. This creates a dynamic where a small number of journalists have outsized influence over the cybersecurity conversation.

The Difference Between Coverage and Investigation

Most cybersecurity reporting is coverage: a breach happens, reporters write about it. A vulnerability is disclosed, reporters explain what it means. A government agency releases guidance, reporters summarize it. This reporting serves a function. People need to know about breaches and vulnerabilities.

Investigative cybersecurity journalism is different. It involves reporters doing original work to uncover facts that would otherwise remain hidden. The best stories from 2025 were all investigative. They required reporters to uncover information that institutions were hiding, to piece together stories from fragmentary evidence, or to follow developments that nobody else was following.

This kind of journalism requires time, resources, and access to sources. It's harder to do. It's more expensive. And it's increasingly rare, which makes the examples we saw in 2025 even more valuable.

Estimated data shows that Immigration and Customs Enforcement accessed the largest share of airline data, followed by the State Department and the IRS. (Estimated data)

The Role of Specialized Knowledge

How Technical Expertise Changes the Reporting

Shane Harris isn't a software engineer. He doesn't write detailed technical analysis of exploit code. But he understood enough about hacking to evaluate whether the claims his Iranian source was making were plausible. He could ask smart questions. He could recognize when details didn't add up. This technical literacy was essential to his investigation.

Similarly, Brian Krebs's reporting on identifying hackers requires understanding how online identities are constructed, how digital trails can be traced, and how to avoid leading sources into danger. You don't need to be a hacker to do this reporting, but you need to understand how hacking works.

The best cybersecurity reporters develop deep expertise over years. They attend conferences. They read technical documentation. They talk constantly with people working in security. They build mental models of how attacks work, how organizations fail, and how these failures could have been prevented.

The Convergence of Skills

What's interesting about the best cybersecurity reporting from 2025 is that it came from reporters with different skill bases. Harris is known for international reporting. Goldberg is a magazine editor and narrative writer. Krebs is a veteran technology reporter. 404 Media's team includes reporters with business and finance backgrounds.

They all brought their particular skills to cybersecurity stories. What unified them was a commitment to doing the work thoroughly, to building stories on evidence, and to telling stories that mattered beyond the immediate news cycle.

How These Stories Changed Something

The Direct Policy Impact

The best test of whether a news story matters is whether it changes anything. The Washington Post's reporting on the U.K. court order led to the government withdrawing the demand. 404 Media's reporting on Airlines Reporting Corporation led to the program being shut down. These aren't theoretical impacts. They're concrete changes in policy and practice.

Goldberg's reporting didn't immediately shut down anything, but it created pressure for the government to improve operational security. It changed the conversation about how senior officials should communicate. It exposed failures that probably still exist but are now being scrutinized.

Krebs's reporting identified a cybercriminal, which likely led to law enforcement investigation. It demonstrated that anonymity isn't absolute, which has deterrence value for others considering similar crimes. And it told a more nuanced story about cybercrime that challenges oversimplifications.

The Indirect Impacts: Changing Narratives

Beyond these direct impacts, these stories changed how people think about cybersecurity issues. Harris's story about his Iranian source changed the conversation about sources in hostile regimes. It highlighted the human cost of being a source. It demonstrated that reporting on state-sponsored hacking is complicated by the fact that state-sponsored hackers are often people with their own agency, their own motivations, and their own fears.

The Goldberg story changed how senior government officials think about secure communication. It revealed incompetence in a context where the stakes are incredibly high. It showed that security theater—appearing to be secure while actually being vulnerable—is a real problem even at the highest levels of government.

404 Media's story changed how people think about data brokers. Before the reporting, most people probably didn't know airlines were consolidating and selling traveler data. Now that's public knowledge. Now when you book a flight, you might think about the fact that the government can track your travel without a warrant.

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of cybercriminals are teenagers, highlighting the need for targeted interventions and support systems to prevent youth involvement in cybercrime.

The Broader Cybersecurity Reporting Ecosystem

Why These Stories Deserve Recognition

It's easy to miss great reporting in the constant flow of news. A story breaks, gets shared widely, and then the next story emerges. Year-end lists serve a function: they create space to acknowledge work that might have been overlooked in the moment. They celebrate reporting that changed something, that taught us something important, or that told a story worth remembering.

The stories from 2025 that stand out aren't necessarily the ones that got the most traffic or the most social media shares. They're the ones that required the most work, that revealed something important, and that mattered beyond the immediate news cycle.

The Importance of Sharing Knowledge

One reason to celebrate these stories publicly is that it creates incentive structures for more of this work. When reporting that requires months of investigation and real risk-taking gets recognized and celebrated, it tells other journalists that this work matters. It tells news organizations that investing in cybersecurity reporting pays off. It tells the public that quality journalism in this space is valuable.

There are dozens of reporters doing serious cybersecurity work. They're at major newsrooms and independent publications. They're in specialized outlets and general interest magazines. They're working in different countries and different languages. The ecosystem of cybersecurity reporting is healthier than it was five years ago, even though it's still underfunded and understaffed relative to the importance of these issues.

Looking Forward: What Cybersecurity Reporting Should Cover

The Stories That Aren't Getting Coverage

If 2025 gave us stories about hacker identities, government surveillance overreach, and data broker arrangements, there are other stories that aren't getting the attention they deserve. Most cyberattacks affecting ordinary people—identity theft, account compromise, scams—get treated as personal problems rather than systemic issues. But they're happening at scale. Most people have been affected by compromise. These stories deserve more coverage.

Similarly, most cybersecurity incidents at organizations don't get reported because most organizations don't disclose them publicly. A company experiences a breach, handles it quietly, and moves on. The incident doesn't become public. This creates a distorted picture of the threat landscape. The attacks that become public are unusual. The ones that stay hidden might be even more common and revealing about systemic problems.

Cybersecurity failures that don't result in breaches also deserve coverage. An organization that fixes a vulnerability before it's exploited is doing something right, but that fix doesn't become news. We hear about failures much more than we hear about successes. We hear about the companies where security failed much more than we hear about the companies where security worked.

The Reporting We Need

The cybersecurity reporting ecosystem would be stronger with more coverage of how organizations build secure systems, how security teams operate, and how security decisions get made at the leadership level. Most reporting on cybersecurity is reactive: something bad happens, we cover it. More reporting that's proactive, that's investigative, that's looking at systemic issues rather than individual incidents, would improve the conversation.

We also need more reporting on cybersecurity from outside the technical perspective. How do ordinary people think about security? What mental models do they have? How do they make decisions about what apps to use, what passwords to create, what data to share? Most cybersecurity reporting assumes technical literacy. More reporting that explains security issues to general audiences would serve the public better.

Cybersecurity sources face significant risks, with imprisonment and physical harm being the most prevalent. (Estimated data)

The Future of Cybersecurity Journalism

How Technology Changes the Reporting Landscape

Artificial intelligence is beginning to affect cybersecurity reporting in multiple ways. AI tools can help reporters process large datasets, identify patterns, and synthesize information from multiple sources. But AI can also be a subject of reporting: new AI tools create new security risks, new attack vectors, and new ethical questions about how AI systems should be deployed.

Law enforcement agencies are increasingly using AI for surveillance. Intelligence agencies are deploying AI systems to analyze threat data. Cybercriminals are using AI to create more convincing phishing emails and more targeted attacks. All of this deserves reporting that explains what's happening, how it works, and what the implications are.

The Consolidation Challenge

There's also a worrying trend toward consolidation of cybersecurity coverage. As news organizations cut staff and budgets, fewer reporters specialize in cybersecurity. This concentrates knowledge and influence. When one reporter breaks a story, everyone else covers it, but nobody else is doing original investigation. This dynamic weakens the reporting ecosystem.

Independent publications and specialized outlets are becoming more important precisely because they can focus on cybersecurity when general interest news organizations are spreading their staff across multiple domains. 404 Media's impact in 2025 was enabled by the fact that the organization could dedicate resources to serious investigation.

Why This Matters Beyond Cybersecurity

The Broader Questions About Information and Transparency

The cybersecurity stories that mattered most in 2025 weren't just about hacking or breaches. They were about transparency, about whether institutions disclose what they're doing, and about what happens when institutions keep information hidden.

The U.K. government issued a secret court order and tried to keep it secret. The airline industry was sharing passenger data without public awareness. The Trump administration was discussing military plans without adequate security. In each case, the story hinged on information becoming public that institutions wanted to keep private.

This speaks to a broader tension in modern institutions. Governments, companies, and organizations want to operate without transparency. But democratic governance, market accountability, and ethical business practices require transparency. The tension between these two impulses is one of the defining issues of our time.

The Role of Journalism in Democracy

These 2025 stories remind us why journalism matters. Not all journalism is equal. Not all reporting is investigative. But the reporting that requires months of work, that takes real risks, that uncovers information that institutions would rather keep hidden—that reporting is foundational to having a functioning democracy.

When institutions know they might be exposed, they behave differently. When the government knows that secret court orders might become public, the government might think twice before issuing them. When airlines know that their data sharing might be reported, they might reconsider arrangements that enable surveillance. This self-consciousness created by the threat of public reporting is a check on institutional power.

This is why supporting quality journalism matters. This is why celebrating good reporting matters. This is why the stories from 2025 that stood out deserve to be recognized: they show what good journalism can accomplish.

The Journalists Behind the Stories

Profiles of Excellence

Shane Harris brought decades of reporting experience to his story about the Iranian hacker. His previous work had established him as someone who could handle sensitive sources and complex international stories. This background enabled the depth and nuance of his reporting.

Jeffrey Goldberg, as editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, brought editorial judgment and resources to his investigation of government operational security. His position enabled him to pursue the story aggressively and to handle the sensitivity appropriately.

Brian Krebs has been covering cybercrime and hacking for longer than most reporters have been in the industry. His source relationships, his technical knowledge, and his investigative techniques are the product of years of focused work.

404 Media's reporting demonstrated that you don't need legacy news resources to do major investigative work. You need skilled reporters, strong editorial judgment, and a commitment to the work.

What These Reporters Have in Common

Despite their different backgrounds and outlets, these reporters share several characteristics. They do the work. They don't rely on press releases or official statements. They build sources and verify information directly. They're patient. They're willing to spend months on a story that might take weeks to publish.

They understand their domain. They're not just generic reporters assigned to cover cybersecurity for a week. They're specialists who have built real expertise. They understand the technical domain, the policy landscape, the international context, and the human factors involved.

They have good judgment about what matters. They don't get distracted by the sensational. They focus on stories that will have real impact or that will teach readers something important about how systems actually work.

Lessons for Anyone Interested in Cybersecurity

What These Stories Teach About Security Failures

The government operational security failure revealed in Goldberg's reporting is instructive. Senior officials were using consumer messaging apps without understanding the security implications. They believed they were secure when they weren't. This kind of security theater—appearing secure while actually vulnerable—is common. It happens when security is treated as an afterthought rather than a core concern.

The Airlines Reporting Corporation's data sharing is instructive about how surveillance often happens: not through dramatic government overreach, but through incremental business arrangements that collectively create something troubling. This teaches us to think carefully about data sharing, about who has access to what information, and about whether appropriate guardrails are in place.

The story of the Iranian hacker highlights that cybersecurity is ultimately about people. Technical measures matter, but the human factors—motivation, fear, the desire to escape a situation—are often the more important drivers of what happens.

What These Stories Should Teach Organizations

For organizations reading about these stories, the lessons are clear. Security requires operational discipline. It requires training. It requires cultural commitment. It requires leadership attention. Organizations that treat security as a compliance checkbox rather than a core value create conditions for failures like what happened in the government.

Data governance matters. Before you consolidate data and make it available for purchase, think carefully about what that data can be used for, who should have access, and whether you're creating surveillance infrastructure as a side effect of a business arrangement.

Transparency matters. Institutions that keep what they're doing hidden create conditions where problems fester. Institutions that operate with reasonable transparency create conditions where problems can be identified and addressed.

The Year in Review

What 2025 Cybersecurity Reporting Tells Us

Looking at the best cybersecurity stories from 2025, a few patterns emerge. First, the most important stories were investigative. They required original reporting. They weren't based on press releases or official announcements. They required reporters to do work that institutions would have preferred they didn't do.

Second, the best stories had impact. They changed policy. They changed behavior. They changed what people understood about how systems work. The stories that matter most are the ones that change something, not just the ones that report on changes that have already happened.

Third, the best stories were about subjects of genuine importance. They weren't about security theater or technical edge cases. They were about how institutions actually fail, about how ordinary people are affected by these failures, and about the structures that enable institutions to act without accountability.

Looking Ahead

As we move forward, we should hope for more reporting like this. We should hope for more journalists willing to do the hard investigative work. We should hope for more news organizations committing resources to cybersecurity reporting. And we should hope for more independent outlets like 404 Media demonstrating that you can do serious journalism without the resources of legacy news organizations.

The best way to encourage this is to read the reporting, to share it, to support the outlets doing this work, and to recognize when journalism changes something. The stories we celebrated in 2025 mattered because they did work that nobody else was going to do. They deserve to be recognized.

FAQ

What makes cybersecurity journalism different from other types of reporting?

Cybersecurity journalism requires a combination of investigative reporting skills, technical literacy, and international relations knowledge that's rarely found in a single reporter. Unlike general technology reporting, cybersecurity stories often involve sources in hostile regimes, classified information, and complex technical details. The best cybersecurity reporters spend years developing expertise and source relationships that enable them to break stories that would otherwise remain hidden. These reporters often operate under pressure from government agencies and need to understand the legal and ethical implications of what they're reporting on.

Why do the best cybersecurity stories require so much investigation?

Many of the most important cybersecurity stories involve information that institutions are trying to keep secret. The Washington Post's reporting on the U.K. court order required finding sources willing to discuss classified or legally restricted information. 404 Media's reporting on airline data sharing required understanding complex business arrangements and tracking down information that wasn't readily available. Brian Krebs's reporting on identifying hackers required following digital breadcrumbs and building relationships with people in the underground. This investigative work can't be done quickly, which is why the best stories often take months to report.

How do reporters find and verify sources for cybersecurity stories?

Cybersecurity reporters typically develop source relationships over years of covering the industry. They attend conferences, follow forums where hackers and security professionals congregate, and build reputation as fair reporters who can be trusted with sensitive information. Verification involves checking technical details, cross-referencing information from multiple sources, and sometimes reaching out to the organizations being written about for comment. For stories involving classified information, reporters often work with lawyers and editors to ensure they can publish without violating laws around disclosure of sensitive information.

What impact do these high-quality cybersecurity stories actually have?

The best cybersecurity stories create several types of impact. Directly, they can lead to policy changes, like when the Airlines Reporting Corporation shut down its warrantless data sharing program. They create pressure on organizations to improve practices, like the government facing scrutiny about operational security. Indirectly, they change how people think about security issues, how journalists approach the topic, and what information the public understands about threats and vulnerabilities. Great reporting also creates deterrence: when hackers know they might be identified, they think twice before acting.

How should someone stay informed about quality cybersecurity journalism?

Following individual reporters who do serious work is the most reliable way to find quality cybersecurity reporting. Reporters like Shane Harris, Brian Krebs, and the team at 404 Media consistently produce investigative work. Major publications including The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and outlets focused on specific beats also do good work. Specialized cybersecurity publications often provide deeper technical coverage than general interest outlets. Supporting independent outlets and subscribing to reporters you respect directly encourages more of this kind of work.

Why is it important to recognize and celebrate good cybersecurity journalism?

Celebrating good reporting creates incentive structures that encourage more of it. When organizations see that serious investigative cybersecurity reporting gets noticed and appreciated, they're more likely to commit resources to it. When journalists see that doing thorough investigation is valued, they're more motivated to do the hard work. When the public recognizes the value of quality reporting, they're more likely to support it financially. Year-end lists and recognition of exceptional journalism help sustain the ecosystem of reporting that we depend on to understand important issues.

What should organizations learn from these major cybersecurity stories?

Organizations should understand that what they're doing matters, even if they think they're operating in private. The government believed its military planning discussions were secure. The airline industry believed its data sharing was just normal business. When institutions operate without transparency, they often end up making decisions that they wouldn't make if they knew the public would find out. Organizations should also understand that security requires real commitment, not just security theater. They should think carefully about data governance, about who has access to what information, and about whether business arrangements have unintended surveillance consequences.

How do independent media outlets like 404 Media compete with legacy news organizations on cybersecurity reporting?

Independent outlets often have an advantage because they can specialize. Rather than spreading resources across multiple topics, an outlet like 404 Media can dedicate reporters to specific areas of focus like surveillance and privacy. This depth of specialization allows them to develop expertise and source relationships that enable major investigations. Independent outlets also sometimes have more editorial freedom to pursue stories that larger organizations might decline for business reasons. What independent outlets lack in resources, they make up for in focus and commitment to the work.

The Stories That Shaped Our Understanding of Cybersecurity

The cybersecurity journalism of 2025 reminds us of something fundamental: what we know about the world depends on what journalists choose to investigate and report. When Shane Harris spent months corresponding with an Iranian hacker, he was doing more than chasing a story. He was creating the possibility that we could understand what motivated state-sponsored hackers in ways that technical analysis alone couldn't reveal.

When The Washington Post exposed the U.K.'s secret court order, they weren't just reporting on government overreach. They were preventing that overreach from becoming normalized. They created the space for public debate about surveillance powers and encryption policy.

When 404 Media shut down the warrantless airline data sharing, they demonstrated the concrete power of investigative reporting. They showed that an independent outlet, working without massive corporate resources, could change policy and protect millions of people's privacy.

As we move forward, the cybersecurity landscape will continue to evolve. New threats will emerge. New technologies will create new questions about privacy and surveillance. New business arrangements will create new surveillance infrastructure if we're not careful. We'll need journalists willing to investigate, to ask hard questions, and to bring important information to light.

The stories from 2025 that stood out deserve to be read and remembered, not just as interesting narratives, but as examples of what journalism can accomplish when it's done with depth, rigor, and commitment to uncovering truths that institutions would prefer to keep hidden.

Key Takeaways

- The best cybersecurity journalism from 2025 was investigative, requiring months of reporting to expose government surveillance, hacker identities, and institutional failures

- Major stories like the Washington Post's investigation of UK surveillance demands and 404 Media's reporting on airline data sharing directly changed policy and protected user privacy

- Cybersecurity reporting requires a unique combination of investigative skills, technical literacy, and international relations knowledge that few journalists possess

- Independent outlets like 404 Media can produce major investigative work by specializing in specific topic areas rather than competing on general news coverage

- The human dimension of cybersecurity—motivations of hackers, risks to sources, security culture in organizations—deserves more reporting attention than technical details alone