Brain Wearables & EEG Technology: The Future of Cognitive Computing [2025]

Your brain generates about 20 watts of electrical activity every single second. That's roughly equivalent to a dim light bulb running in your skull right now. For decades, neuroscientists captured this activity through bulky laboratory equipment that required you to sit perfectly still inside an MRI machine or undergo invasive procedures. But something shifted in the last few years.

Consumer companies started strapping sensors to people's heads outside hospitals. The promise? Monitor your brain waves, optimize your mental state, prevent burnout, enhance gaming performance, improve meditation, and even help diagnose neurological conditions. At major tech conferences, you'd walk past booth after booth showcasing headbands, earbuds, and headsets claiming to unlock your brain's hidden potential.

The question everyone's asking: Is this actually science, or are we buying expensive snake oil?

That's exactly what we're diving into here. This isn't a marketing piece for brain tech companies, nor is it dismissive skepticism. Instead, we're examining the genuine neuroscience behind these devices, what they can realistically do today, where the hype overshoots the evidence, and what the future might actually look like when brain monitoring becomes as common as fitness tracking.

The consumer brain-monitoring space sits in an interesting middle ground. The underlying science of electroencephalography (EEG) is solid and well-established. Researchers have used EEG clinically since the 1920s. But consumer applications of this technology are relatively new, the validation evidence is still building, and marketing departments have a way of stretching findings beyond what the data supports.

Let's start with the fundamentals, work through what devices are actually doing at major tech events, explore the legitimate use cases with real research backing them, acknowledge where manufacturers overstate benefits, and then consider whether these gadgets belong in your life.

TL; DR

- EEG technology is scientifically valid: Measuring brain electrical activity works reliably, but consumer devices measure different properties than clinical EEG machines

- Current consumer applications show promise in three areas: meditation/focus training, performance optimization for specific tasks, and early detection of cognitive changes

- The hype significantly outpaces evidence in most categories: Claims about general productivity boost, sleep optimization, or mental health treatment are mostly unsupported by rigorous studies

- Major tech companies are investing heavily: Startups and established brands launched multiple EEG-integrated products at CES, signaling confidence in future market growth

- Your brain isn't like your heart: We understand cardiovascular health far better than brain function, so wearable brain devices are inherently less predictive than heart-rate monitors

Understanding the Neuroscience: What Brain Waves Actually Are

Let's establish some foundation here. Your brain contains roughly 86 billion neurons, each capable of firing electrical signals. When neurons activate, ions move across cell membranes, creating tiny electrical currents. When millions of neurons fire in coordinated patterns, these currents become strong enough to detect from outside the skull.

This is where electroencephalography comes in. Electrodes placed on your scalp pick up voltage changes generated by this underlying neuronal activity. The electrical signals travel through skin, bone, and cerebrospinal fluid before reaching those surface electrodes. By the time they arrive, they're attenuated significantly, but still measurable. That's the fundamental principle behind every consumer EEG device on the market today.

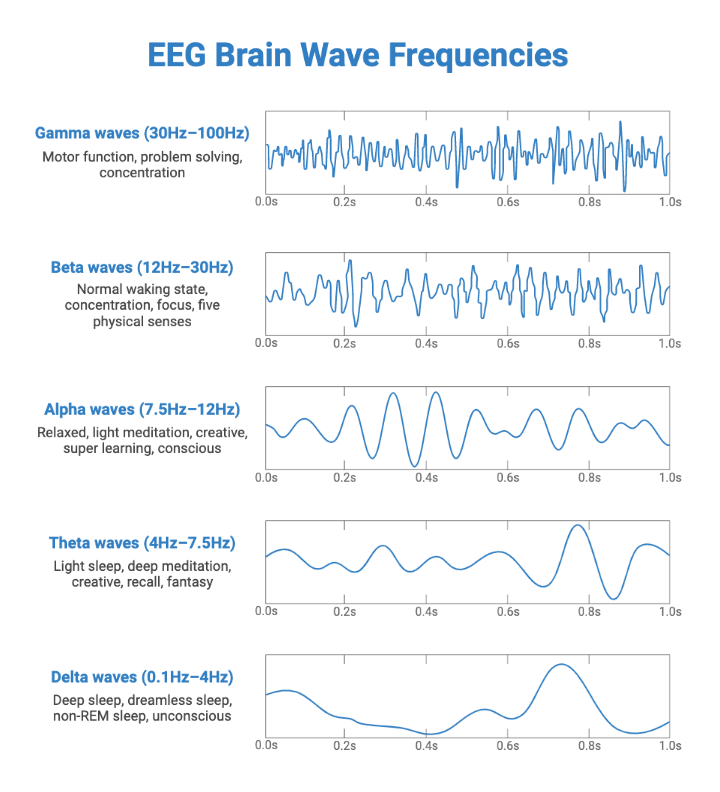

Now, those voltage patterns get categorized into frequency bands. Different frequencies correlate with different mental states, which is where the "brain wave" terminology originates. Understanding these bands helps explain what marketers claim their devices can do.

Delta waves (0.5 to 4 Hz) dominate during deep sleep. Your brain essentially hits pause. Researchers associate delta sleep with memory consolidation and physical recovery. When someone tells you a device will "optimize your sleep," they're likely talking about detecting delta activity and timing alerts around it.

Theta waves (4 to 8 Hz) show up during light sleep, drowsiness, and deep meditation. They're associated with creativity, memory formation, and the hypnagogic state right before you fall asleep. Some research links theta rhythms to problem-solving and insight. This is why meditation-focused EEG devices emphasize theta detection.

Alpha waves (8 to 12 Hz) characterize relaxed wakefulness. You're awake but not concentrating hard on anything specific. Alpha typically increases when you close your eyes and decrease when you open them or focus on a task. Devices claiming to help you "find calm focus" are essentially teaching you to maintain alpha while performing attention-demanding tasks.

Beta waves (12 to 30 Hz) dominate during active thinking, concentration, and problem-solving. When you're working through a math problem or debugging code, your brain generates beta. High beta or excessive beta can indicate anxiety or stress. Gaming performance companies focus on optimizing the balance between beta for focus and lower frequency activity for relaxation.

Gamma waves (30+ Hz) represent the fastest brain activity, associated with peak cognitive processing, learning, and information integration. They're harder to detect from surface electrodes because they attenuate quickly through the skull, so consumer devices rarely measure them accurately.

Here's the critical distinction: This frequency-based categorization is well-established in neuroscience research. But in clinical settings, EEG specialists look at much more than frequency bands. They examine amplitude, timing, distribution across different brain regions, symmetry between hemispheres, and how patterns change in response to stimuli. Consumer EEG devices, constrained by cost, power consumption, and usability, measure coarser features.

It's like the difference between checking your car's fuel gauge and having a professional mechanic perform a full diagnostic. Both give you information, but they answer different questions at different levels of precision.

The Hardware Revolution: What Companies Actually Built

For years, consumer EEG was a niche interest. Companies like Intera Xon released the Muse headband as early as 2014, primarily for meditation tracking. It worked, but the market remained small. Most people didn't see a reason to strap sensors to their heads.

Then something shifted. Gaming companies got involved. Researchers published more studies on neurofeedback. Enterprise started asking whether brain monitoring could reduce burnout. Suddenly, major hardware manufacturers saw an opening.

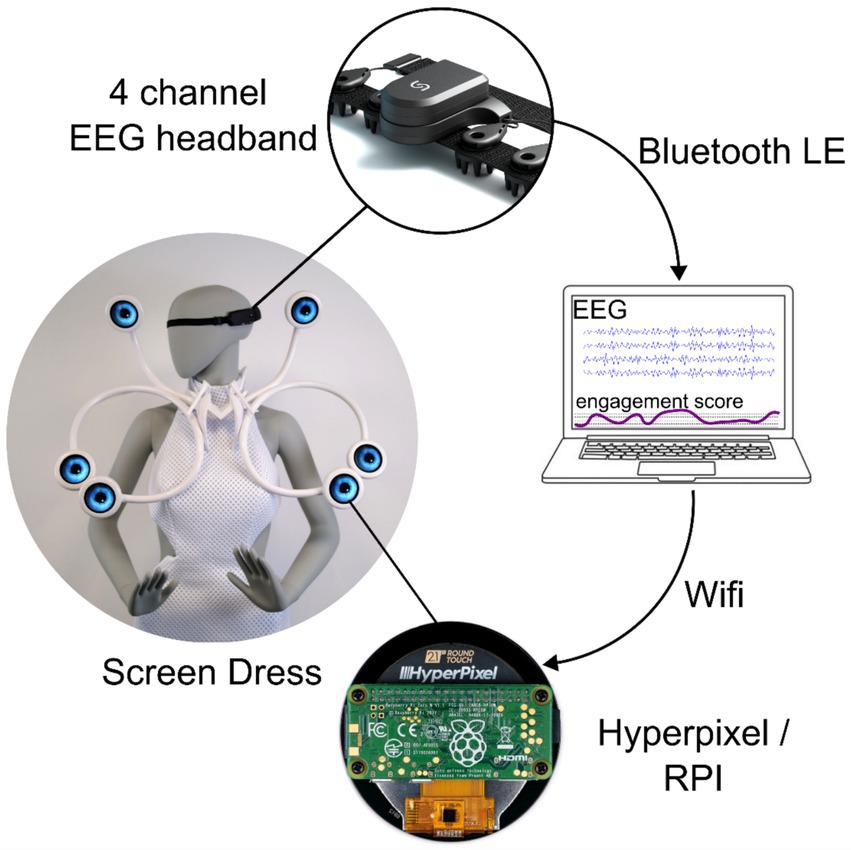

Companies began integrating EEG sensors into form factors people already wear. Headphones became the obvious choice. If you're already wearing headphones for audio, why not add brain sensors? This drives the form-factor innovation. Rather than special-purpose headbands, you get gaming headsets, premium over-ear headphones, or earbuds with embedded sensors.

The engineering challenge is significant. Consumer EEG headsets need multiple electrode contact points spaced around the head to capture activity from different brain regions. They need to be comfortable enough to wear for hours. They need minimal electrical noise from the surrounding environment. They require regular charging. The sensors must maintain consistent contact with the scalp despite hair, sweat, and head movement.

Manufacturers solved these problems through iteration. Flexible electrode materials improve comfort. Signal processing algorithms filter out electromagnetic interference from phones, Wi Fi, and nearby electronics. Machine learning handles the individual variation in brain anatomy that makes generic signal interpretation unreliable.

But here's what's important: These improvements made consumer EEG devices better at capturing some information about brain activity. They didn't fundamentally change what information is available. A consumer EEG device with 8 electrodes cannot deliver the spatial resolution of a clinical 64-electrode setup, and it certainly can't compete with f MRI's ability to image deep brain structures.

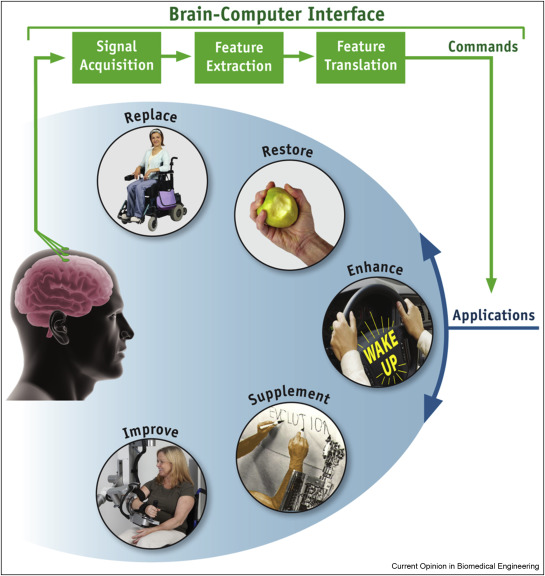

Companies launching at major tech events understand this. The best ones don't claim otherwise. Instead, they focus on specific, measurable applications where the limitations don't matter. Detecting gross changes in attention? Doable. Measuring meditation-related alpha increases? Possible. Diagnosing specific neurological conditions? Not with consumer devices.

Meditation, Focus, and Neurofeedback: Where the Evidence Holds

Let's start with applications where research actually backs up the marketing.

Meditation neurofeedback has some solid evidence behind it. When you meditate, your brain exhibits recognizable patterns. Alpha waves increase. Theta activity changes. Frontal lobe activation shifts. Accomplished meditators show characteristic signatures distinguishable from non-meditators even in their baseline EEG.

Companies like Muse built their entire product around this. The headband detects when your attention drifts (a decrease in alpha, increase in faster frequencies) and provides audio feedback. Sounds like calm weather when you're focused, storms when your mind wanders. The feedback loop helps you learn to recognize the mental state associated with focused attention and return to it.

Does this work? Yes, with caveats. Studies show meditation training with neurofeedback produces similar outcomes to meditation training without it. The device isn't doing something meditation alone can't do. But it does accelerate learning. New meditators using neurofeedback reach proficiency faster than those meditating without it. The immediate feedback creates a tighter learning loop.

The limitation: You're learning to recognize and maintain a specific brain state as detected by an EEG algorithm. That's genuinely useful for meditation. But it doesn't necessarily mean you're unlocking profound neurological changes. Regular meditation without devices produces many of the same long-term brain changes. The device is a training tool, a more efficient path to something achievable through effort alone.

Focus optimization works similarly. When you're concentrating hard on a task, your brain exhibits measurable changes. Your attention network activates. Certain frequency patterns emerge. Some gaming-focused companies developed algorithms that detect when your attention starts to wane and provide notifications.

In controlled settings, this works. Gaming performance company Neurable demonstrated measurable improvements in accuracy and reaction time when users received biofeedback training. But here's the important caveat: The improvements came from training your brain to enter and maintain a specific mental state, not from some magic property of the device.

Think about it like this. A golf coach might have you videotape your swing to analyze technique. The video doesn't improve your golf. But the feedback from analyzing the video helps you adjust. Similarly, brain-monitoring devices provide information about your mental state that you can't directly sense. Training with that information can improve performance. But the device is a tool for self-awareness and feedback, not a shortcut.

Research on neurofeedback generally finds that real-time feedback about brain activity can help people control mental states. This is well-documented. But effect sizes vary wildly depending on the application, the individual, and the specific brain measure being monitored.

The Gaming Performance Angle: Measurable Improvements With Caveats

Gaming companies see brain monitoring as the next frontier in competitive advantage. Esports organizations invest heavily in performance optimization. They analyze reflexes, reaction times, mouse sensitivity, monitor placement, even chair ergonomics. Adding brain state optimization makes sense in that context.

Neurable's partnership with gaming hardware manufacturer Hyper X yielded headsets designed to train gamers into optimal mental states. The core idea: Competitive gaming performance depends heavily on maintaining focused attention without excessive stress. Too much stress and your hands shake, your timing goes off. Too little focus and you miss opportunities. There's a sweet spot.

The company developed algorithms identifying this sweet spot in individual gamers and training algorithms to help them reach and maintain it consistently. Gamers using the system practiced focus-training exercises, received feedback on their mental state, and gradually developed better ability to self-regulate.

The measured improvements are real. Faster reaction times, better accuracy, sustained performance over longer gaming sessions. But here's what's critical to understand: The improvement came from training. Someone using the device for a single session with no practice shows minimal improvement. The device itself doesn't boost performance. It's a training tool that accelerates learning.

This is why the gaming angle works better than general productivity claims. Gaming is a narrow, well-defined domain with clear performance metrics. You can measure improvement objectively. You can train specific mental states. The feedback loop is tight and immediate.

General productivity claims don't have this clarity. What does "optimal focus for work" even mean when work varies from coding to writing to meetings? There's no single brain state that's optimal across all these contexts. Oversimplified claims about brain optimization completely miss this nuance.

Sleep Optimization: The Overstated Application

Everyone wants better sleep. The market for sleep optimization products is massive. So naturally, companies applying EEG to sleep claims.

What EEG can legitimately do for sleep: Detect sleep stages with decent accuracy. Delta waves indicate deep sleep. Sleep spindles (brief bursts of faster activity) appear during Stage 2 sleep. REM sleep shows specific patterns. Consumer devices can identify these stages reasonably well.

What companies claim EEG sleep devices do: Improve sleep quality, prevent sleep issues, optimize sleep cycles, and boost daytime cognitive performance through better sleep.

The gap between those two is where problems emerge.

Earlier consumer EEG devices like the Zeo Mobile attempted to wake people at optimal points in their sleep cycle. The theory makes intuitive sense. You feel groggy when woken during deep sleep but fresh when woken during lighter sleep. Detecting sleep stages and timing alarms accordingly should work.

Does it? Sometimes. In studies, people woken during light sleep stage feel less groggy than those woken during deep sleep. But the effect is modest. And the device needs to work accurately in the noisy home environment, which is challenging. Signal quality degrades with hair contact, electrode drift, and movement.

The deeper issue: Even if you can detect sleep stages perfectly, using that information requires careful timing. Waking someone 20 minutes before they'd naturally wake works better than waking them at an arbitrary point in light sleep. The algorithm needs to predict awakening, not just identify current stage. That's harder than marketing suggests.

Beyond wake timing, companies claim their devices improve sleep through suggestions, coaching, or passive monitoring. "Passive monitoring" is the most honest approach but offers minimal intervention. You get data about your sleep, but data alone doesn't change behavior reliably.

"Coaching" approaches often rely on generic sleep hygiene advice. Go to bed earlier, avoid screens before sleep, keep your room cool. These recommendations help, but they're not based on your brain activity specifically. They're universal advice that any sleep researcher would give.

The honest assessment: Consumer EEG sleep devices can provide useful information about your sleep patterns. But the improvements in sleep quality typically come from behavioral changes, not from the devices themselves. If someone sleeps better with a monitoring device, it's probably because they're paying more attention to sleep habits, not because the device did something magical.

Mental Health, Stress, and the Limits of Measurement

This is where EEG companies often overreach the most dramatically.

Companies present brain monitoring as a tool for mental health optimization. The pitch sounds reasonable. Stress and anxiety have measurable correlates in brain activity. Beta waves increase with anxiety. Certain brain regions show different activation patterns in people with depression or anxiety. So shouldn't monitoring these patterns help?

In theory, yes. In practice, the relationship between brain activity and mental state is far more complex than consumer marketing suggests.

First, individual variation is enormous. Two people experiencing the same level of stress show different EEG patterns. Two people with identical EEG patterns might report completely different stress levels. The brain is individualized. What looks "normal" for one person might indicate anxiety for another.

Second, acute and chronic stress produce different patterns. Someone panicking about an upcoming presentation shows different brain activity than someone chronically stressed about their job situation. A device can't distinguish these without substantial context.

Third, the relationship between detected brain activity and actual mental state is probabilistic, not deterministic. Even in controlled research settings, you can't reliably infer mental state from brain activity alone. You need behavioral, physiological, and self-report information.

Yet companies launch products claiming to "monitor your stress levels," provide "mental health insights," or "predict burnout." These claims typically rest on weak evidence and oversimplified models.

The honest view: Brain monitoring can be part of a mental health strategy. If you're working with a therapist or psychiatrist, EEG biofeedback might provide useful training. Detecting significant changes in your baseline brain activity might indicate something worth investigating with a healthcare professional. But the device alone won't diagnose anything, won't treat anything, and won't replace professional mental health support.

Marketing suggesting otherwise is ethically problematic. Mental health is serious. Overselling brain-monitoring devices to people struggling with anxiety or depression creates false hope and potentially delays actual helpful treatment.

Cognitive Decline Detection: The Most Legitimate Clinical Application

Now we reach an application with genuine clinical potential.

Certain neurological conditions produce characteristic changes in EEG patterns. Alzheimer's disease typically shows slowing of EEG rhythms. People with mild cognitive impairment often display distinctive patterns. Epilepsy produces highly recognizable spikes. Some brain injuries correlate with specific EEG signatures.

Medical researchers have used EEG to aid diagnosis for decades. The question now becoming relevant: Can consumer EEG devices contribute to early detection of cognitive changes in the general population?

The potential benefit is significant. If cognitive decline could be detected years before clinical diagnosis, intervention might be more effective. Early detection could guide lifestyle changes that slow progression. It could trigger earlier specialist consultation.

But the practical challenges are substantial. First, baseline variation is enormous. What constitutes a "normal" EEG for a 65-year-old varies tremendously. You'd need individual baseline measurements to detect changes. Second, many factors affect EEG independent of brain disease. Sleep deprivation, medication, caffeine, even time of day create variations. Third, detecting potential decline requires sophisticated interpretation. Not every EEG change indicates pathology.

Some companies are developing algorithms to identify subtle EEG changes that might indicate early cognitive issues. This is legitimate research. But it requires careful validation, long-term follow-up, and integration with other clinical measures. A consumer device that simply says "your brain activity changed" would be more harmful than useful.

The most responsible approach: Use EEG to complement clinical assessment, not replace it. If someone has concerns about cognitive decline, they should see a neurologist. If that neurologist recommends monitoring with EEG, consumer devices might provide useful supplementary data. But the device shouldn't be a substitute for professional evaluation.

The Neuroscience Consensus: What Experts Actually Say

When you talk to prominent neuroscientists about consumer brain monitoring, you get nuanced perspectives that marketing departments rarely highlight.

Professor Karl Friston at University College London, one of the world's most influential neuroscientists and experts in brain imaging, emphasizes a crucial distinction. The field has made tremendous progress in understanding brain structure and function through advanced imaging. But understanding the brain remains vastly behind understanding the cardiovascular system.

Consider this: Doctors understand heart function in exquisite detail. They can measure blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation, ejection fraction, coronary flow. They can predict cardiovascular disease with reasonable accuracy. Heart-rate monitors are genuinely useful because the relationship between heart rate and health is well-established.

For the brain? We're several decades behind. No single EEG measure reliably predicts cognitive outcomes. The relationship between brain activity patterns and mental states is complex and individualized. Clinical neuroscientists trained for years can sometimes interpret EEG patterns meaningfully. Algorithms trained on population averages often fail for individuals.

Friston emphasizes that technologies like functional MRI have advanced understanding tremendously but also revealed how complex the brain is. Simple models fail. The brain isn't like other organs. It has redundancy, plasticity, and individual variation that makes population-level conclusions unreliable at the individual level.

This is why neuroscientists tend to be cautiously enthusiastic about consumer brain monitoring. The underlying science is sound. EEG is real. The correlations between brain activity and mental states exist. But the gap between understanding these general relationships and making reliable predictions about individual people remains large.

The consensus view: Consumer brain monitoring devices will become increasingly useful as data accumulates, algorithms improve, and validation studies expand. But we're still early. Current devices are primarily training tools, not diagnostic or predictive tools.

The Current Market Landscape: Who's Actually Building Brain Wearables

Companies entering the consumer brain monitoring space range from startups with revolutionary ideas to established hardware manufacturers adding brain sensing to existing products.

Neurable represents the focused startup approach. The company started with brain-computer interface research and narrowed focus to gaming and workplace performance. They developed algorithms specifically for these applications. Rather than claiming their device improves everything, they focus on domains where brain state optimization is clearly relevant.

Intera Xon's Muse meditation headband has been the longest-running successful consumer EEG product. They've iterated for over a decade, accumulated substantial user data, and published some validation research. Their claims are measured. They don't promise enlightenment, just feedback on meditation practice.

Hyper X brought gaming hardware expertise and partnered with Neurable to add brain sensing to their headsets. This approach leverages existing relationships with gamers who already buy premium audio gear.

Smaller companies are experimenting with different form factors. Some focus on earbuds. Others build headbands. A few are developing adhesive electrodes that stick to your forehead. Each approach involves tradeoffs between comfort, signal quality, and practical usability.

Larger electronics manufacturers have been relatively cautious. Some have research initiatives exploring brain-computer interfaces. But mainstream consumer products with brain sensing from major brands remain rare. The market hasn't yet proven substantial enough to justify major investment. That's likely to change.

The pattern suggests the market is transitioning from novelty to more focused applications. Early entrants tried to solve everything. Current products concentrate on narrower use cases with clearer value propositions.

Integration With Other Sensors: The Holistic Biometric Approach

Brain activity doesn't exist in isolation. What your brain is doing relates to your heart rate, breathing patterns, skin conductance, body temperature, and sleep patterns.

Smarter companies are integrating EEG with other sensors to provide more comprehensive insights. A device might measure heart rate alongside EEG, recognizing that stress affects both. It might monitor sleep stages using EEG while also tracking respiratory patterns. It might correlate brain activity changes with movements or posture.

This multimodal approach addresses one of the fundamental limitations of EEG alone. No single brain measure is highly predictive of behavioral outcomes. But combinations of measures often work better.

For example, detecting stress requires more than just brain activity. You need heart rate variability, respiration, and self-report all confirming it. Similarly, detecting cognitive fatigue works better when combining EEG patterns with eye-tracking, reaction time slowdown, and subjective fatigue rating.

The companies doing this well recognize they're building comprehensive wellness platforms, not just brain monitors. The EEG component provides valuable information, but it's one piece of a larger picture.

This also addresses one of the biggest challenges with consumer EEG: individual variation. Your baseline brain activity differs from mine. Without personal baseline data, absolute EEG values tell you little. But if you measure multiple variables and look at how patterns change relative to your individual baseline, you get much more reliable information.

The Validation Challenge: Separating Science From Marketing

This is crucial for consumers trying to evaluate claims.

For a medical device in the US, the FDA requires substantial evidence before approval. Proof of safety, proof of effectiveness, and quality manufacturing standards. But FDA oversight applies primarily to devices marketed for diagnosis, treatment, or monitoring of medical conditions.

Many consumer brain-monitoring devices avoid this by marketing themselves as wellness tools rather than medical devices. "Improve your meditation practice" isn't a medical claim. "Help optimize your focus" isn't treating a medical condition. This classification sidesteps FDA oversight but also means validation standards are lower.

Companies might conduct internal studies, publish research, or reference academic literature. But without FDA oversight or independent verification, you can't be certain claims are accurate.

The strongest indicator of legitimate technology is publication in peer-reviewed scientific journals. When researchers publish validation studies, other scientists review the methodology, check for bias, and ask critical questions. Published research isn't perfect, but it's substantially more reliable than company marketing.

Some questions to ask when evaluating brain device claims:

-

Has the specific device been validated in published research? Not research on EEG generally or on algorithms theoretically similar to this one, but on this actual product.

-

Are claims specific and measurable, or vague and aspirational? "Improved focus measured by reaction time on a specific task" is measurable. "Optimize your mental performance" is marketing nonsense.

-

Does the company acknowledge limitations? Any honest technology has limitations. If marketing claims perfection, that's a red flag.

-

Are claims consistent with published neuroscience? Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Simple claims require simple evidence.

-

Is the business model dependent on making increasingly dramatic claims? Subscription services that require continuous excitement might exaggerate benefits to retain customers.

Companies serious about validation typically publish data, reference peer-reviewed research, and are transparent about study limitations.

Practical Applications You Could Use Today

Despite the caveats, brain-monitoring technology does have practical applications available right now.

Meditation Training: If you practice meditation and want accelerated learning, neurofeedback devices provide genuine value. They're not essential. Many accomplished meditators learned without devices. But they do reduce the learning curve. If you're willing to invest in the device and spend time training, you'll develop focus skills faster than without it.

Performance Training for Specific Skills: Similar logic applies to gaming, esports, or other domains requiring high focus. The device provides feedback that trains mental state. You still do the actual training. But you do it with better feedback.

Sleep Pattern Monitoring: Getting detailed information about your sleep stages can help identify issues. If you're consistently getting insufficient deep sleep, that's useful to know. You can adjust bedtime, sleep environment, or daily habits accordingly. The device doesn't fix anything, but the information enables better decisions.

Baseline Monitoring for Personal Insight: Tracking changes in your own brain activity over time can reveal patterns. You might notice how stress affects your EEG, how sleep deprivation shows up in your patterns, or how activities like exercise or meditation correlate with your brain state. This personal data isn't medically significant, but it can motivate better choices.

Complementary Assessment for Neurological Concerns: If you're seeing a neurologist about cognitive concerns, some devices might provide supplementary information. But the device should complement medical assessment, not replace it.

The practical utility in each case comes from specific application combined with user effort. The device provides a tool, but you're doing the actual work.

Future Directions: Where the Field Is Heading

Current consumer brain devices are first-generation technology. What might change?

Miniaturization and Integration: As sensors shrink and power requirements drop, brain monitoring might integrate into everyday devices. Not as a special headset, but as one function among many in devices you'd wear anyway. Imagine earbuds that monitor meditation quality alongside music. Glasses that track cognitive state while you work. Hats or caps with embedded sensors.

AI-Driven Personalization: Machine learning algorithms trained on massive datasets might improve at identifying individual patterns. Rather than using population-average correlations, future devices could learn your specific brain signatures and what they mean for you.

Integration With Digital Services: Your brain data could feed into adaptive apps, websites, or work software. Productivity apps that adjust recommendations based on your cognitive state. Games that adapt difficulty based on your focus level. Learning platforms that time content based on your readiness to learn.

Clinical Collaboration: As evidence accumulates, clinical neuroscientists might increasingly work with consumer devices. Not relying on them for diagnosis, but using the data they generate to track progression, monitor treatment response, or guide intervention timing.

Neuroplasticity-Based Training: Better understanding of how brain training actually produces changes might enable more targeted training programs. Not vague "boost your brain" claims, but specific interventions for specific outcomes.

The trajectory suggests brain monitoring will become increasingly common. But the path from "neat technology" to "genuinely useful tool" requires continued validation, realistic claims, and integration with other health data.

The Honest Reality: What These Devices Do and Don't Do

Let's be direct about what consumer brain-monitoring devices actually accomplish.

They're legitimate measurement tools: EEG is real neuroscience. Consumer devices measure it with reasonable accuracy in their practical application domain. Claiming they measure nothing is inaccurate.

They don't diagnose medical conditions: Not without clinical validation studies and medical oversight. Devices marketed directly to consumers aren't performing diagnosis.

They can provide training feedback: Real-time information about brain activity helps train mental states and develop focus skills. This is genuine value but depends on your willingness to use the training programs.

They can't override biology: If you have a neurological condition, a consumer EEG won't treat it. If you have depression, a brain-monitoring device won't cure it. If you have sleep apnea, monitoring your sleep stages won't fix the underlying problem.

They're information sources, not solutions: The utility comes from what you do with the information. A device that tells you your focus is waning is only useful if you then take action based on that information.

They work best when expectations are clear: Devices help with meditation practice, focus training, and personal pattern monitoring. They don't generally boost productivity, prevent disease, or unlock hidden mental potential.

The market is still developing: First-generation consumer brain devices are improving rapidly. Future versions might be more integrated, more accurate, and more useful. Current devices are proto-products rather than mature technology.

The companies making the most honest claims about their devices typically generate the most sustainable businesses. Overselling creates initial excitement but disappoints users and damages credibility long-term.

The Research Landscape: What Scientists Are Actually Finding

Beyond marketing claims, what's the peer-reviewed research actually showing about brain-monitoring devices and neurofeedback?

Meditation and focus training research consistently shows modest but real benefits from real-time neurofeedback. Meta-analyses of neurofeedback studies find effect sizes ranging from small to moderate. Improvement is measurable but not enormous. The effect also depends substantially on user engagement. People who practice benefit more than people who casually try the device.

Gaming and esports performance research is emerging. A few published studies show focus training correlated with improved gaming performance, but we need more validation. The sample sizes have been small, and some studies haven't been independent (company-conducted research). This field needs more third-party validation.

Mental health applications show mixed results. Some research suggests EEG biofeedback can help with anxiety or ADHD in clinical settings with professional support. But direct-to-consumer devices marketed as mental health tools haven't undergone the same validation. Claims need skepticism without peer-reviewed evidence.

Cognitive decline detection is actively researched. Some algorithms show promise at identifying patterns associated with cognitive impairment. But this requires long-term follow-up studies, clinical validation, and comparison with existing diagnostic tools. Current research is exploratory, not conclusive.

Sleep optimization research shows modest benefit from sleep stage feedback for waking timing, but smaller benefits for overall sleep quality improvement.

Across domains, the research message is consistent: Brain-monitoring devices can provide useful information and can be training tools. They're not magic. They work best when integrated with behavioral change, not as passive solutions.

Comparing With Other Monitoring Technologies

Let's put brain monitoring in context with other biometric monitoring people use.

Heart-rate monitors and fitness trackers are ubiquitous. They measure something well-understood: heart rate. The relationship between heart rate patterns and health is well-established. A fitness tracker provides useful information because decades of medical research have validated what heart rate tells us about health.

Blood glucose monitors are highly specialized. They measure one specific thing: blood glucose level. This measurement is validated, understood, actionable. Diabetics rely on them because the relationship between glucose and health is clear and the actions based on glucose readings are proven to improve health.

Brain-monitoring devices are somewhere in between. EEG is a validated measurement, but what it actually tells you about mental state and health is less clear. Unlike heart rate, we don't have simple population-level relationships between EEG patterns and specific outcomes.

This doesn't make brain monitoring useless. It just means the information is less actionable. A fitness tracker telling you your heart rate is high is straightforward. A brain device telling you your alpha waves are low is more ambiguous. What does that mean? What should you do?

The best brain-monitoring devices address this by providing specific feedback tied to specific behaviors. "Your brain shows this pattern when you're focused on the task." That's actionable. "Your brain waves are suboptimal." That's marketing nonsense.

The comparison also suggests brain monitoring might eventually become as ubiquitous as heart-rate monitoring, but probably not in the near term. We need more research, better validation, and clearer clinical utility.

Ethical Considerations: Privacy, Consent, and Brain Data

Brain data raises unique ethical questions that most other biometric data doesn't.

Your heart rate is relatively impersonal. It indicates physical exertion, but not much about your thoughts or personality. Your brain activity is different. It might reveal information about your emotional state, focus, or cognitive patterns. It's more personally sensitive.

This raises important privacy questions. Who owns your brain data? What happens if you stop using the device? Can companies sell anonymized brain data to researchers? What if that data is used in ways you didn't anticipate?

Current regulations are unclear. Most device companies collect data and store it on servers. Terms of service usually permit them broad use rights. Users rarely read or understand these policies. You might unwittingly agree to let companies use your brain data for research, marketing analysis, or other purposes.

Brain data also raises consent questions. If an employer provides a device to monitor employee focus, that's ethically complex. Employees might feel coerced into accepting monitoring they wouldn't choose independently. If a school uses brain monitoring in students, there are paternalism concerns. Who decides what brain states are "optimal"?

There's also the risk of misuse. Brain data could theoretically be used for manipulation, discrimination, or invasion of privacy. Someone accessing your brain activity patterns might infer things about your mental health, personal interests, or vulnerabilities.

Responsible companies address these concerns by:

- Being transparent about data collection and storage

- Allowing users to own and export their data

- Not selling or sharing data without explicit consent

- Minimizing data collection to what's necessary

- Encrypting data both in transit and at rest

- Having clear deletion policies

These are reasonable standards, but not universal practice. If you're considering a brain-monitoring device, understanding the privacy policy is essential.

The Role of Regulation: Where Standards Will Probably Develop

As the consumer brain-monitoring market grows, regulation will likely increase.

Currently, consumer EEG devices mostly avoid FDA oversight by not making medical claims. But this is somewhat arbitrary. A device that diagnoses ADHD would need FDA clearance. A device that "helps you focus better" doesn't. The distinction is marketing rather than technical.

Future regulation will probably draw clearer lines. Devices making any claims about medical benefits might face FDA oversight. That would require clinical validation studies, proof of safety, quality manufacturing standards. It would reduce claims and potentially slow innovation, but it would also protect consumers from unsupported promises.

Consumer protection might also develop through FTC enforcement against false advertising. If companies make claims their devices can treat conditions without evidence, the FTC could force them to stop. This has happened with other health-related consumer products.

International approaches vary. Europe's regulatory environment is often stricter. Japan has different standards. As the market becomes global, companies might face a patchwork of regulations.

The most likely outcome is increased oversight without eliminating the market. Devices would need validation to make medical claims but could continue operating as wellness tools with more modest marketing.

Real-World Use Cases: Who Actually Benefits

Beyond the theoretical discussions, who actually uses brain-monitoring devices and finds them valuable?

Serious Meditators: People practicing meditation seriously often adopt neurofeedback tools. They want to accelerate progress and verify they're achieving deeper states. The device validates their practice and provides concrete feedback.

Esports Competitors: High-level gamers competitive enough to invest in premium equipment see brain training tools as similar to any other performance optimization. If it provides edge, they'll try it.

Workplace Performance Enthusiasts: Some professionals are obsessed with optimization. They measure sleep, workouts, nutrition, and cognition. Brain monitoring fits into this category. These early adopters drive adoption and provide useful feedback about what works.

Meditation App Users: Apps like Muse integrate brain data with digital meditation guidance. Users who enjoy app-based meditation and want more engagement might adopt the hardware.

Research Participants: Academic researchers studying neuroscience or brain training recruit participants willing to use consumer devices. This drives data generation and validation.

People With Specific Health Concerns: Some people monitoring cognitive changes or working with neurologists use consumer devices as supplementary tools. This is legitimate use if done in consultation with healthcare providers.

Gamers Who Buy Premium Gear Anyway: Gamers already spending hundreds on peripherals might add brain-monitoring headsets as one more component. They're not buying it just for the brain feature but considering it alongside gaming performance.

Notably absent from heavy adopter categories: general consumers seeking wellness improvement. Most people don't adopt these devices. The market remains niche because the value proposition isn't compelling enough for mainstream adoption.

As technology improves and more applications validate, the adopter base will likely expand. But current growth comes from enthusiasts rather than from mainstream demand.

The Cost-Benefit Analysis: Is a Brain Monitor Worth It

Let's think practically. Should you buy a consumer brain-monitoring device?

If you actively meditate and want to accelerate progress, a device costs

If you're serious about esports or competitive gaming, and you spend hundreds on other performance gear, adding

If you're seeking general wellness improvement, stress reduction, or better sleep, current devices offer minimal proven benefit. You'd get better returns from exercise, sleep hygiene, therapy, or meditation without the devices. Benefit: unclear. Cost:

If you're hoping a brain device will fix a medical condition, that's a misunderstanding of what current technology does. These devices don't treat conditions. Benefit: none. Cost: Money better spent on actual medical care.

The honest assessment: Consumer brain monitors are tools for specific applications where validation exists and you're willing to do the training work. For everything else, you're paying for hype.

Future devices might change this calculus. As technology improves, costs drop, and more applications validate, broader adoption becomes likely. But right now, the practical market is niche.

Key Takeaways for Skeptical Consumers

Let me summarize the crucial points.

EEG is real science: Measuring brain electrical activity works. Decades of neuroscience research validate this. Don't dismiss the technology entirely.

Consumer devices measure less than clinical EEG: They work within practical constraints. They're useful tools within their scope but don't replace medical evaluation.

Brain activity correlates with mental states: Various brain patterns associate with focus, relaxation, stress, and meditation. These correlations are real but complex and individual-specific.

Three applications have genuine evidence: Meditation training, focus training for specific tasks, and sleep stage detection all have reasonable research support. Everything else is speculative.

Marketing overshoots evidence dramatically: The gap between what companies claim and what research supports is substantial. Always ask for validation evidence.

Individual variation is enormous: What works for one person might not work for another. Population-level research doesn't predict individual outcomes.

These are tools, not solutions: Devices provide feedback and information. Actual improvement comes from your actions based on that information.

The field is early: We're in the first-generation consumer market. Technology, validation, and applications will improve significantly.

Regulation is coming: As the market grows, oversight will increase. Claims will need better support.

Your skepticism is appropriate: Being cautious about overstated brain-monitoring claims is reasonable. Healthy skepticism protects you from marketing manipulation.

FAQ

What is an EEG and how does it work in consumer devices?

An electroencephalogram measures electrical activity from your brain through electrodes placed on your scalp. Your neurons generate electrical signals that propagate through tissue and bone to the scalp surface, where sensors detect them. Consumer EEG devices use a small number of electrodes positioned around the head to capture patterns of this brain activity in real time. Unlike clinical EEG machines with 64+ electrodes in controlled laboratory settings, consumer devices make practical tradeoffs between accuracy, comfort, and usability to create wearable products.

How accurately do consumer brain-monitoring devices measure brain activity?

Consumer devices measure gross patterns of brain activity reasonably well within their practical scope. They can detect when brain waves shift between frequency bands, identify sleep stages with decent accuracy, and measure changes in overall activity levels. However, they lack the spatial resolution of clinical EEG and can't precisely locate where in the brain activity originates. They also struggle with noise from movement, hair contact inconsistency, and electromagnetic interference. For specific applications like meditation feedback or gaming focus training, the accuracy is sufficient. For making precise medical diagnoses, it's not.

Can brain-monitoring devices treat mental health conditions like anxiety or depression?

No. Consumer brain devices cannot treat mental health conditions. They can provide information about brain activity patterns, which might be interesting but doesn't constitute treatment. Some research suggests neurofeedback might help with anxiety or ADHD in clinical settings with professional oversight, but direct-to-consumer devices marketed as mental health solutions haven't undergone the clinical validation required for treatment claims. If you're struggling with mental health, professional treatment with a therapist or psychiatrist is what actually helps. Brain monitors might serve as supplementary tools within professional treatment, but they're not treatment themselves.

What are brain waves and what do different frequencies mean?

Brain waves refer to electrical activity organized into different frequency bands. Delta waves (0.5-4 Hz) occur during deep sleep. Theta waves (4-8 Hz) appear during light sleep and meditation. Alpha waves (8-12 Hz) characterize relaxed wakefulness. Beta waves (12-30 Hz) show up during active thinking and concentration. Gamma waves (30+ Hz) represent fast processing. Different mental states consistently correlate with different frequency distributions. However, these are statistical tendencies, not deterministic relationships. The same person might show different patterns on different days, and different people show different patterns for seemingly identical mental states.

Can brain monitors help me sleep better?

Brain monitors can provide information about your sleep stages and patterns, which some people find useful. If consistent sleep data helps you recognize issues and adjust habits, that's valuable. Some devices can time alerts for better wake timing. But the actual improvements in sleep usually come from behavioral changes like adjusting bedtime, improving sleep environment, or reducing caffeine. The device provides information, but you're doing the work that produces improvement. It's not passive optimization.

Are brain-monitoring devices FDA approved?

Most consumer brain-monitoring devices avoid FDA approval by not making medical claims. If a device claims to treat a medical condition, it would need FDA clearance. If it positions itself as a wellness tool rather than a medical device, FDA oversight doesn't apply. This regulatory gap is one reason to be cautious about claims. Lack of FDA approval doesn't necessarily mean the device is bad, but it does mean validation standards are lower than medical devices face.

Can brain monitors predict or prevent cognitive decline?

This is an active area of research, but current consumer devices aren't validated for this purpose. Some research suggests EEG might eventually help identify early signs of cognitive changes, but that requires long-term studies, clinical validation, and integration with other diagnostic information. If you're concerned about cognitive decline, seeing a neurologist is appropriate. Brain devices might eventually complement clinical assessment, but they're not ready to stand alone as prediction tools.

What privacy concerns should I have about brain data?

Brain activity data is more personally sensitive than most biometric information because it might reveal emotional states, thoughts, or cognitive patterns. You should understand what data a device collects, where it stores it, who can access it, and what rights the company has to use it. Read the privacy policy carefully. Look for companies that allow you to own and delete your data, don't sell data without consent, and encrypt information. If a company is vague about data practices, that's concerning.

How much improvement in performance can I expect from brain-monitoring devices?

For applications with validation like meditation training or gaming focus training, expect modest improvements if you do the training. You might learn focus skills faster, or improve specific performance metrics like reaction time. But the improvements come from your training effort, not from passive monitoring. Without commitment to training, you should expect minimal benefit. Devices amplify training but don't replace it.

Will brain-monitoring devices become mainstream like fitness trackers?

It's possible but not imminent. Fitness trackers measure something well-understood with clear health implications. Brain monitoring is more complex. As validation research accumulates, costs decrease, and applications expand, broader adoption becomes possible. But current devices serve niche applications. Mainstream adoption probably requires more compelling value propositions and clearer clinical utility than exist today. The trajectory suggests gradual expansion rather than sudden mainstream adoption.

Conclusion: Navigating the Brain Monitoring Frontier

Consumer brain-monitoring technology sits at an interesting inflection point. The underlying science is sound. EEG is a legitimate measurement tool. The applications showing the most promise, like meditation training and performance optimization, have reasonable research support. But the gap between current reality and marketing hype is enormous.

Here's what's actually happening at major tech conferences: Companies are showcasing tools that measure something real, apply that measurement in specific ways, and honestly claim modest benefits for those specific applications. Other companies are making vague promises about brain optimization, mental health transformation, or cognitive superpowers.

The divide between these two categories matters more than the distinction between consumer and clinical devices. Honest companies with specific claims and supporting evidence deserve skepticism but not dismissal. Vague companies making dramatic claims deserve dismissal regardless of impressive booth displays.

For you as a consumer, this suggests a practical approach: Be curious about the technology but critical of the claims. Understand what research actually supports. Distinguish between measurement and application. Recognize that information alone doesn't produce improvement; action does. Expect modest benefits from validated applications, not transformational results from overstated promises.

The field will evolve. Brain-monitoring technology will improve. Validation evidence will accumulate. Regulation will clarify. In five years, consumer brain devices might be far more useful and trustworthy than today. But right now, the technology is proto-revolutionary rather than revolutionizing.

Use brain monitors as tools for specific applications where validation exists. Don't expect them to diagnose conditions, treat diseases, or unlock hidden mental potential. Do expect them to provide useful information and training feedback if you're willing to engage seriously with the technology.

The brain is the next computing frontier. Consumer brain-monitoring devices might eventually be part of how we interact with ourselves and machines. But that future is still being built. Current devices are foundation elements rather than finished products. Approach them with eyes open, expectations realistic, and skepticism healthy.

Your brain is genuinely remarkable. But improving it requires understanding, effort, and evidence-based approaches. No device changes that fundamental truth.

Related Articles

- Ultrahuman Air Quality Monitor Review: Sleep & Health Impact [2025]

- CES 2026 Best Products: Pebble's Comeback and Game-Changing Tech [2025]

- Samsung Galaxy Watch8 Discounts on Amazon: Full Buyer's Guide [2025]

- Ozlo's Sleep Data Platform: The Future of Sleep Tech [2025]

- CES 2026 Bodily Fluids Health Tech: The Metabolism Tracking Revolution [2025]

- NVIDIA DLSS 4.5 at CES 2026: Complete Technical Breakdown [2026]

![Brain Wearables & EEG Technology: The Future of Cognitive Computing [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/brain-wearables-eeg-technology-the-future-of-cognitive-compu/image-1-1768068858329.jpg)