The PC Builder's Reckoning: Why DIY Lost to the Prebuilt Explosion

There was a time when building your own PC felt like a no-brainer. You'd save money, learn something, and end up with exactly what you wanted. That formula worked for years. But something shifted in 2024, and it caught a lot of us off guard.

I'm someone who's spent more hours on PCPart Picker than I'd like to admit. I've helped friends spec out gaming rigs, workstations, and streaming boxes. I actually enjoy the research phase, comparing benchmarks and finding hidden deals. So when I spotted the Machenike Mini PC at

I opened a new PCPart Picker tab with genuine confidence. This should be simple, I thought. Build a better machine for less money. It's what builders have done for two decades.

I was spectacularly wrong.

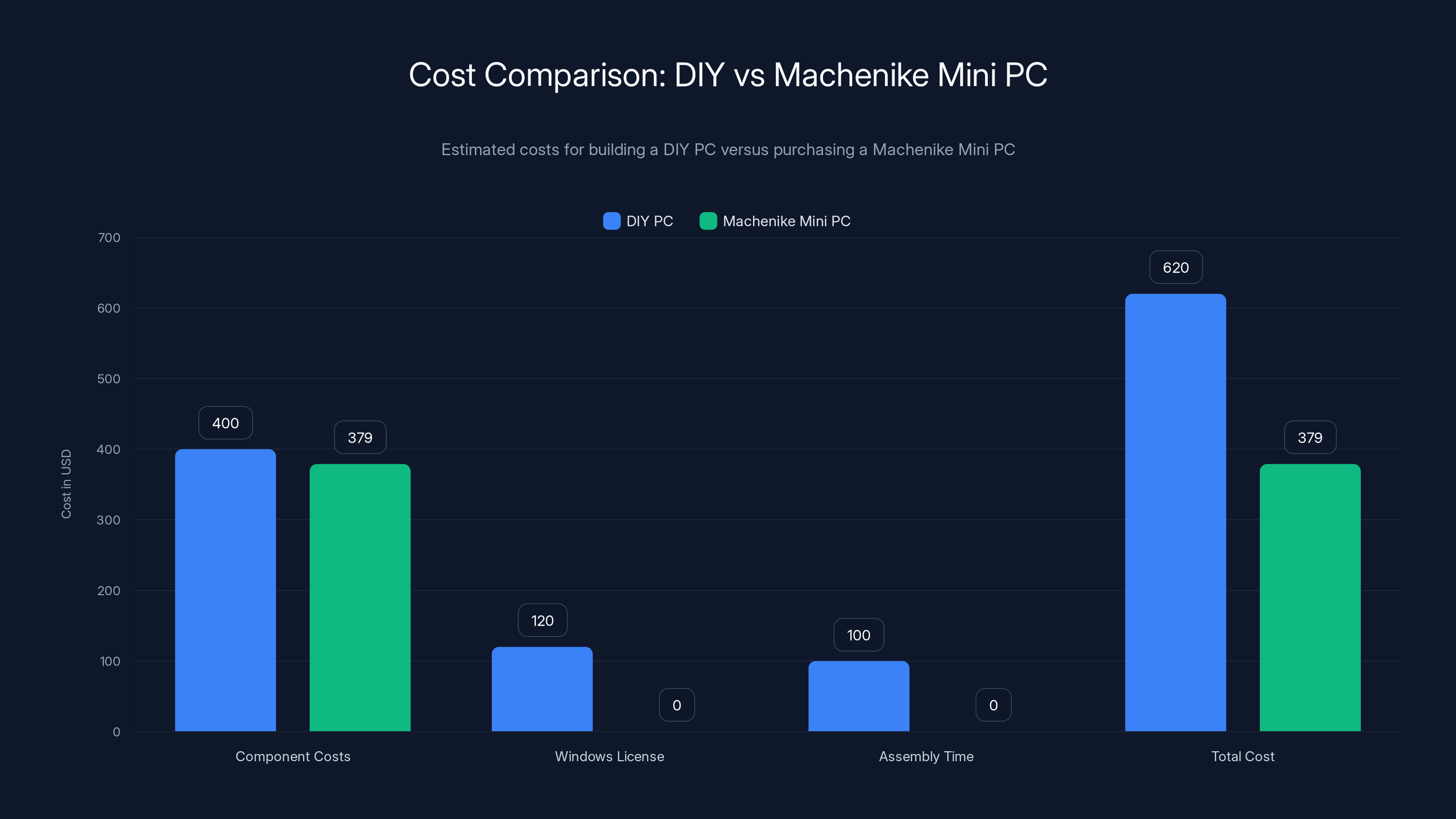

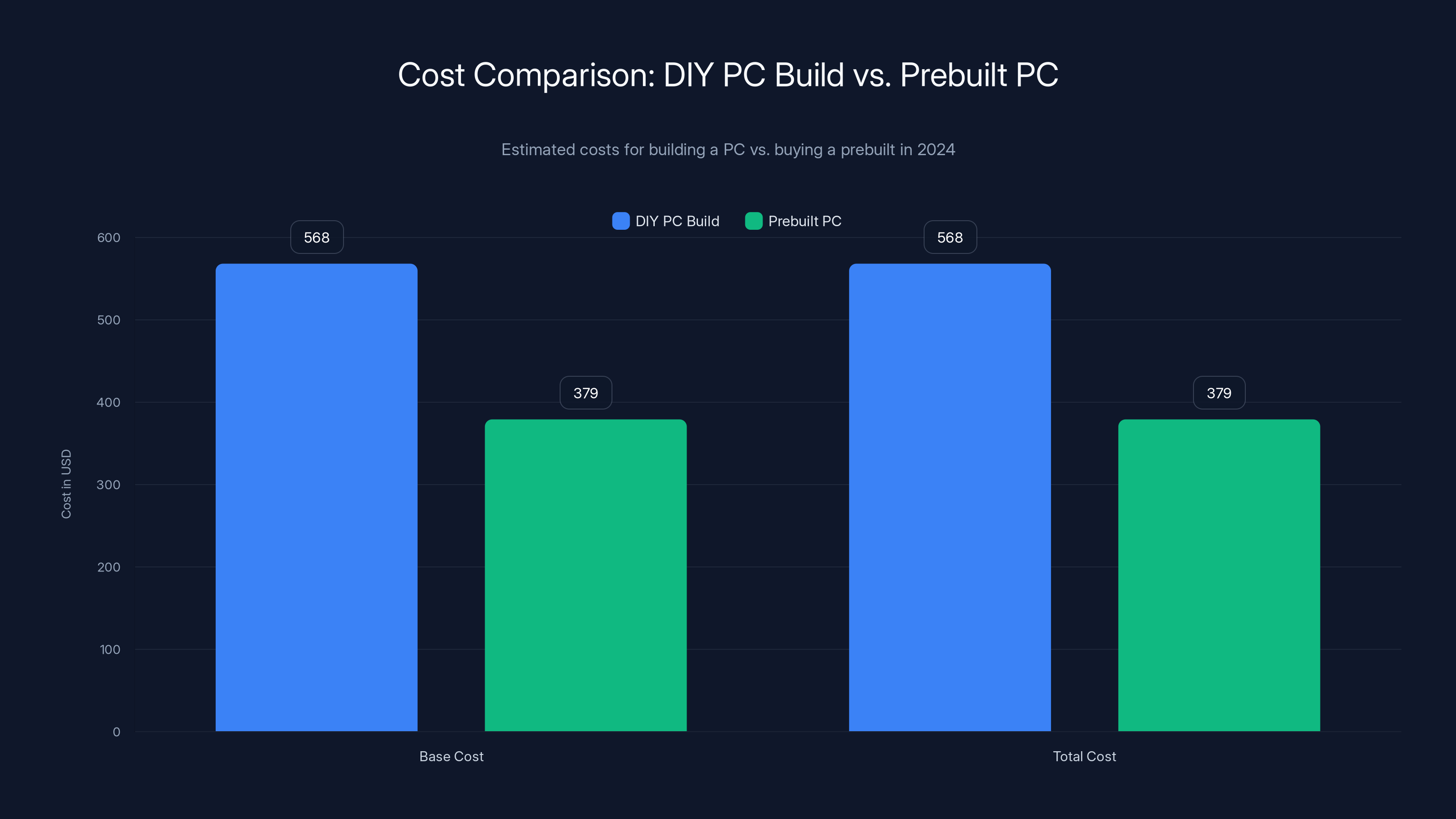

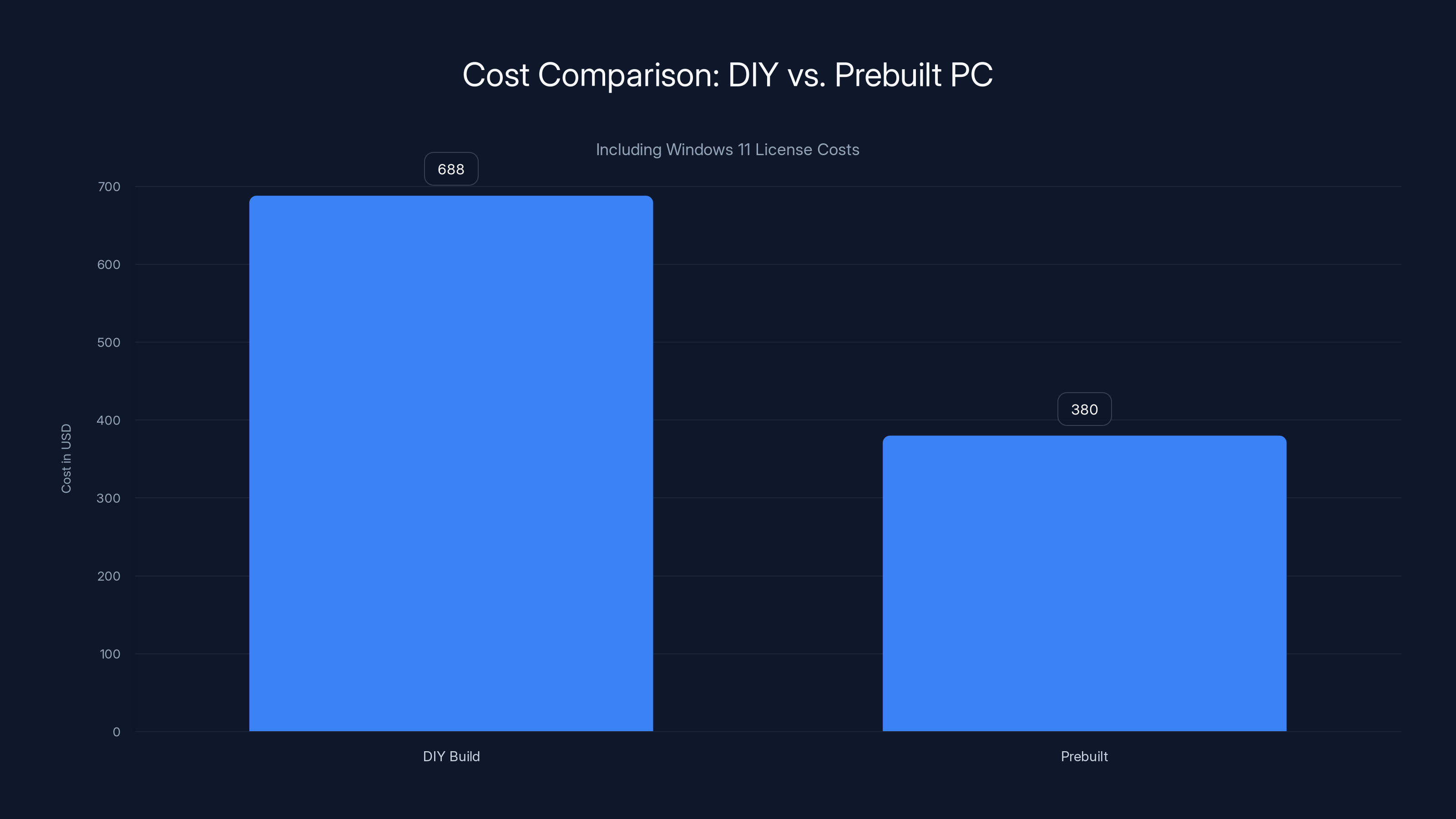

Not only did I fail to match the price. I didn't even come close. By the time I'd assembled what I thought was a competitive build, my cart sat at $568—before Windows, before shipping, before my own labor. That's nearly 50% more than the prebuilt. And the kicker? The Machenike still held its own on performance.

What I discovered over that afternoon wasn't just a pricing problem. It was a symptom of something bigger: the entire economics of PC building have shifted. The hobbyist builder isn't competing on equal ground anymore. Not because they're bad at picking parts, but because the market itself has transformed.

Let's talk about what happened, why it matters, and what it means for anyone thinking about their next computer.

The Machenike Challenge: What We're Actually Comparing

Before we dive into the economics, let's get specific about what we're looking at. The Machenike Ryzen 7 8745HS Mini PC isn't some knockoff budget box. This is a legitimate machine with real credentials.

The CPU is an AMD Ryzen 7 8745HS. This is a mobile processor, not a desktop chip, but that distinction matters less than people think. The 8745HS runs eight cores at respectable clocks, and on Passmark's multi-core benchmark, it scores around 29,000 points. That's competitive with mid-range desktop CPUs from just a couple years ago. You're getting actual performance here, not entry-level smartphone processor stuff.

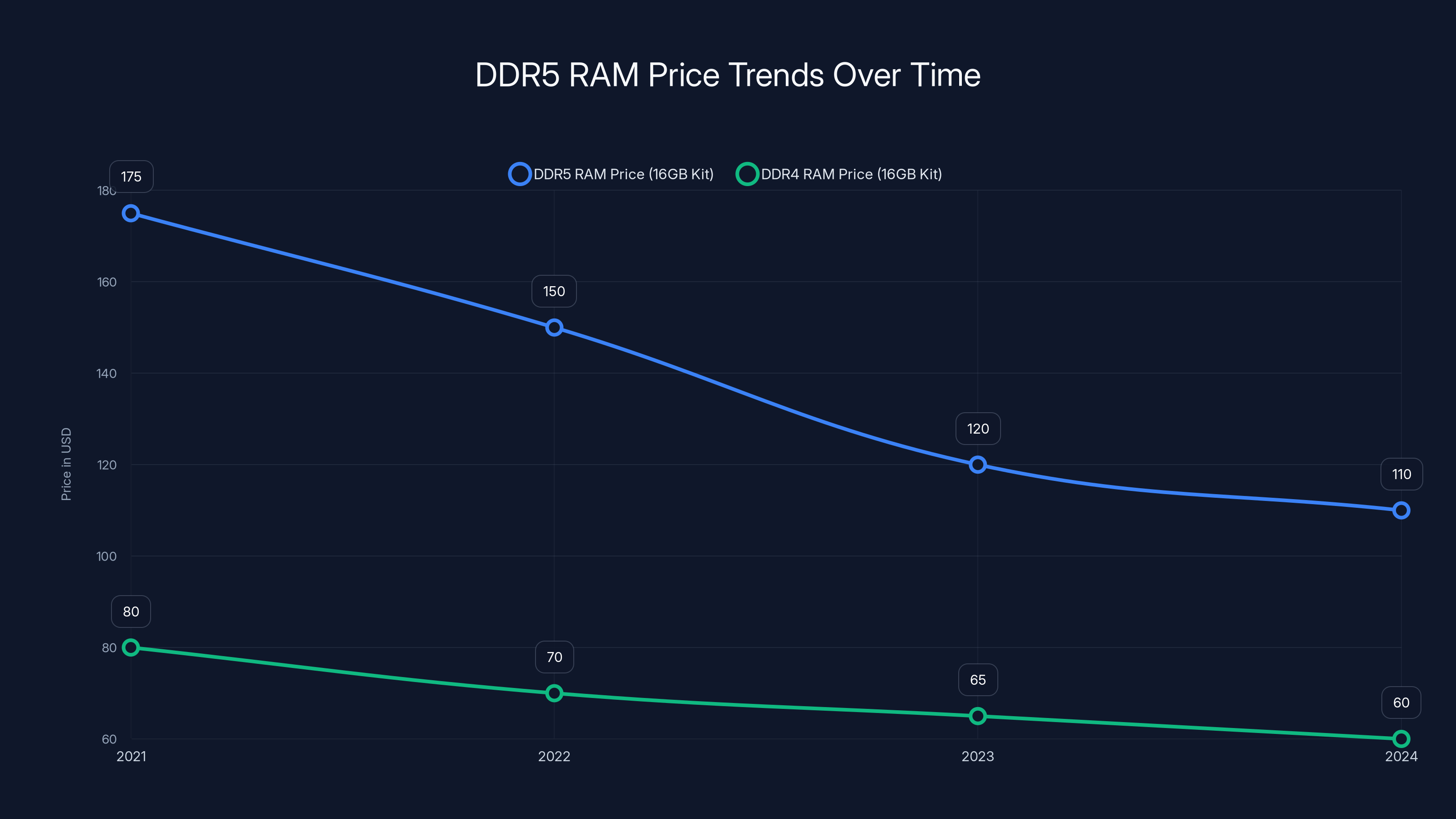

The memory configuration is 16GB of DDR5. Not DDR4, not some weird proprietary variant. Modern, fast RAM that you'd actually want in your machine. That's crucial because DDR5 pricing has been a nightmare in 2024, and I'll explain why in a moment.

Storage comes as a 512GB SSD. Again, that's real capacity. Not a 128GB drive where you can fit Windows and maybe three applications. Half a terabyte is enough for a working machine for most people, especially since everything lives in the cloud now anyway.

But here's what matters: the prebuilt includes all of this in a case, with a motherboard, with a power supply, with a heatsink and cooling solution that's actually designed for this CPU. It ships with Windows. It's tested, it's warranted, and it arrives at your door ready to work.

And it costs $379.

The Machenike Mini PC offers a significant cost advantage over a DIY build, primarily due to bulk purchasing and manufacturer optimizations. Estimated data.

My DIY Attempt: The Parts List That Broke My Budget

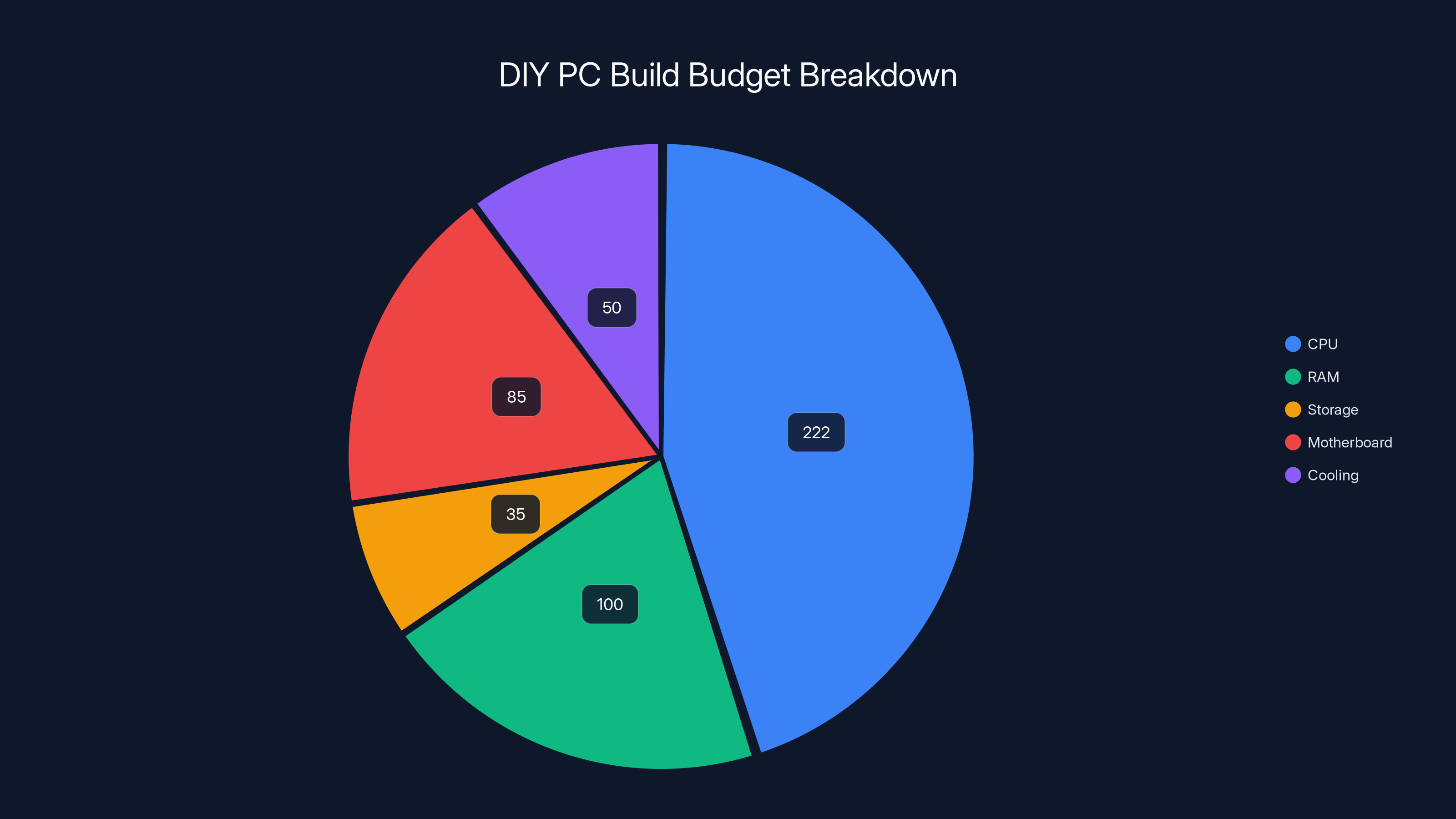

Let me walk you through what I built on PCPart Picker, because the breakdown itself tells the story.

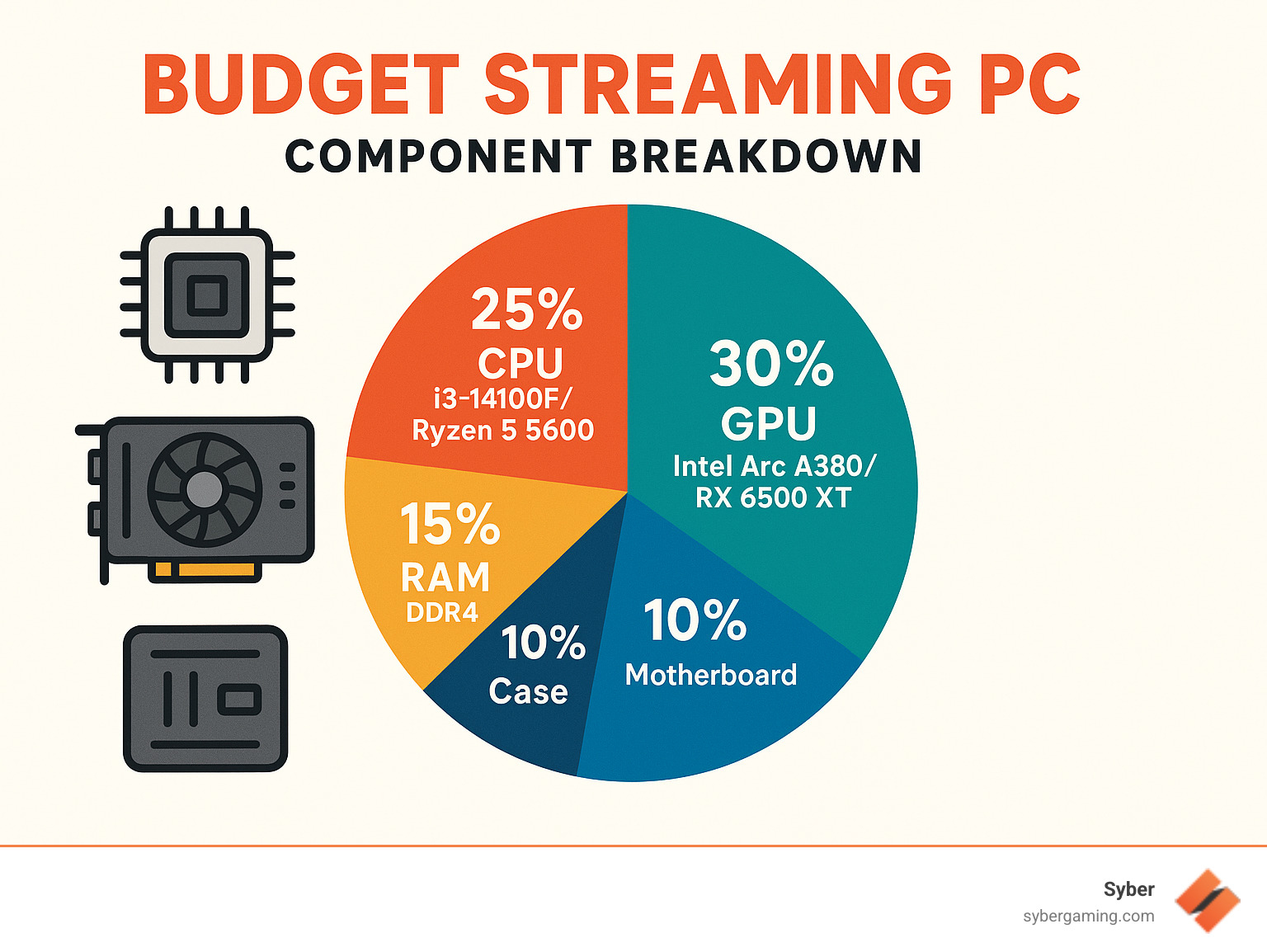

For the CPU, I chose the AMD Ryzen 5 9600X. It's a newer desktop processor, and at the time I was pricing this out, it was only about $22 more expensive than the older Ryzen 5 7600X. The 9600X comes with six cores (compared to the 8745HS's eight cores), but it has higher single-thread performance. On paper, the Passmark multi-core score sits around 29,900 points—barely 3% faster than the mobile chip, despite being a full generation newer. Let me repeat that: a brand-new desktop CPU, with a 50% higher thermal design power requirement, barely outperforms a mobile CPU from the previous generation.

That's your first wake-up call about the modern processor landscape.

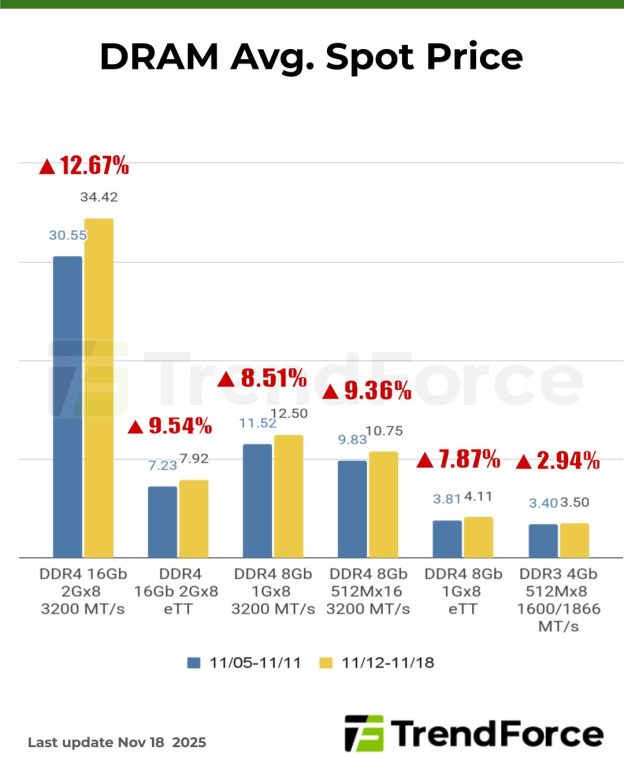

For RAM, I grabbed two DDR5 sticks totaling 16GB. I didn't buy the cheapest option on the market; I picked Kingston Fury Beast, which is a solid midrange option. Cost: about $100. That's roughly 25% of my entire DIY build budget, just for memory. And here's the thing: I had to research prices across multiple retailers because DDR5 pricing remains genuinely volatile.

Storage was a Kingston 500GB PCIe Gen 4 NVMe drive, basically the budget option that still performs well. Nothing fancy, nothing exotic. $35.

The motherboard is an ASRock A620M. It's not premium, it's not overengineered. It's the board that lets a Ryzen 5000 series CPU actually function. It has power delivery, it has BIOS support, it has PCIe slots. It's the baseline motherboard for this class of system. Cost: $85.

CPU cooling required an aftermarket solution. The 9600X isn't a high-powered chip, but you can't run desktop Ryzen without dedicated cooling. I picked a Noctua NH-U9S, which is entry-level for Noctua but still a quality cooler. $50.

The case and power supply are where most people try to save money, but I didn't cheap out. A basic tower case with a 500W power supply (sufficient for a Ryzen 5 + integrated graphics system) came to about $70.

Total: $568 before operating system, before sales tax, before shipping, before the three hours of my time spent researching, assembling, troubleshooting, and installing Windows.

The CPU and RAM together account for nearly half of the total budget, highlighting their significant impact on overall costs. Estimated data.

The DDR5 Crisis Nobody's Talking About Enough

Let's zoom in on the RAM situation, because it's the elephant in the component room.

Two years ago, DDR5 was brand new. It was exclusive. It was expensive because yield rates were low and demand was high. You'd see 16GB kits for

DDR5 supply was supposed to normalize. It has, sort of. Prices have come down. But they haven't come down nearly as much as historical precedent would suggest.

Here's why that matters for our comparison: that $379 Machenike includes DDR5. A prebuilt manufacturer can negotiate bulk pricing on RAM that individual buyers simply cannot access. They're buying not 16GB, but 16GB across thousands of units. They're buying directly from NANYA or Samsung or SK Hynix, not through retail distribution networks.

When you go to Newegg or Amazon as an individual, you're buying through retail markup. You're paying for distribution, for logistics, for the retailer's margin. The prebuilt manufacturer absorbed those costs into their already-established supply chain.

I could have bought DDR4 for my DIY build. I could have saved maybe $30. But then I'm comparing a DDR5 prebuilt against a DDR4 custom build, and that's not apples-to-apples. That's the trap.

The math is brutal: individual consumers can't compete on component pricing anymore because the economy of scale has separated from the hobbyist market.

Why the Passmark Comparison Is More Complex Than It Seems

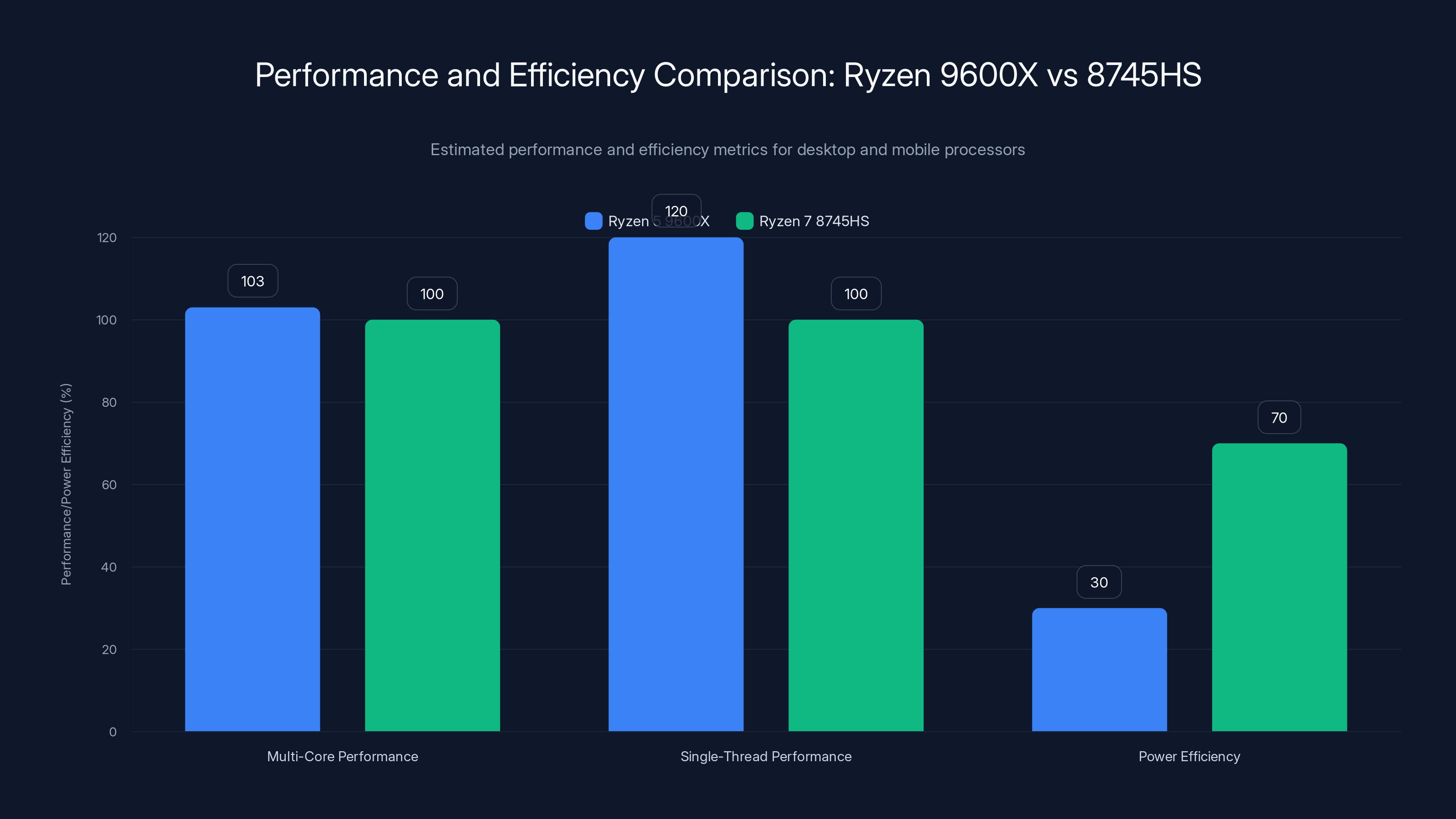

I mentioned earlier that the 9600X (desktop) and 8745HS (mobile) have nearly identical multi-core performance. That deserves deeper examination.

The Ryzen 5 9600X runs at base clocks around 3.9 GHz with boost up to 5.6 GHz. It has 6 cores, 12 threads, and a TDP of 65 watts. Wait—65 watts? That's surprisingly efficient for a desktop chip.

The Ryzen 7 8745HS runs at base clocks around 3.5 GHz with boost up to 5.0 GHz. It has 8 cores, 16 threads, and a TDP of 30 watts. Yes, 30 watts. This is a mobile chip designed to run on battery power in a laptop.

So we have a desktop processor with 2.17x the TDP pulling only 3% better performance in multi-core workloads. The mobile chip's eight cores let it nearly match the desktop chip's throughput despite running at lower clocks and lower power consumption.

Why am I drilling down on this? Because single-thread performance tells a different story. The 9600X dominates in single-thread benchmarks, often running 15-20% faster. If your workflow is Python development, video editing, or anything that benefits from per-core speed, the desktop chip wins decisively.

But if you're doing something like data processing, video transcoding, content creation pipelines, or anything that can parallelize across cores, the mobile chip's eight cores become an advantage that offsets its lower clock speeds.

For typical users doing typical tasks—web browsing, document editing, light photo work, watching videos—the 8745HS is honestly fine. Better than fine. It's legitimately capable.

This matters because the Machenike isn't a stripped-down budget box. It's a genuinely competent machine. You're not sacrificing capability; you're sacrificing flexibility. And for a $379 price point, that's a trade most people don't even realize they're making.

The Ryzen 5 9600X offers slightly better multi-core and significantly better single-thread performance, but the Ryzen 7 8745HS excels in power efficiency. Estimated data based on typical benchmarks.

The Cooling Problem That DIY Builders Ignore

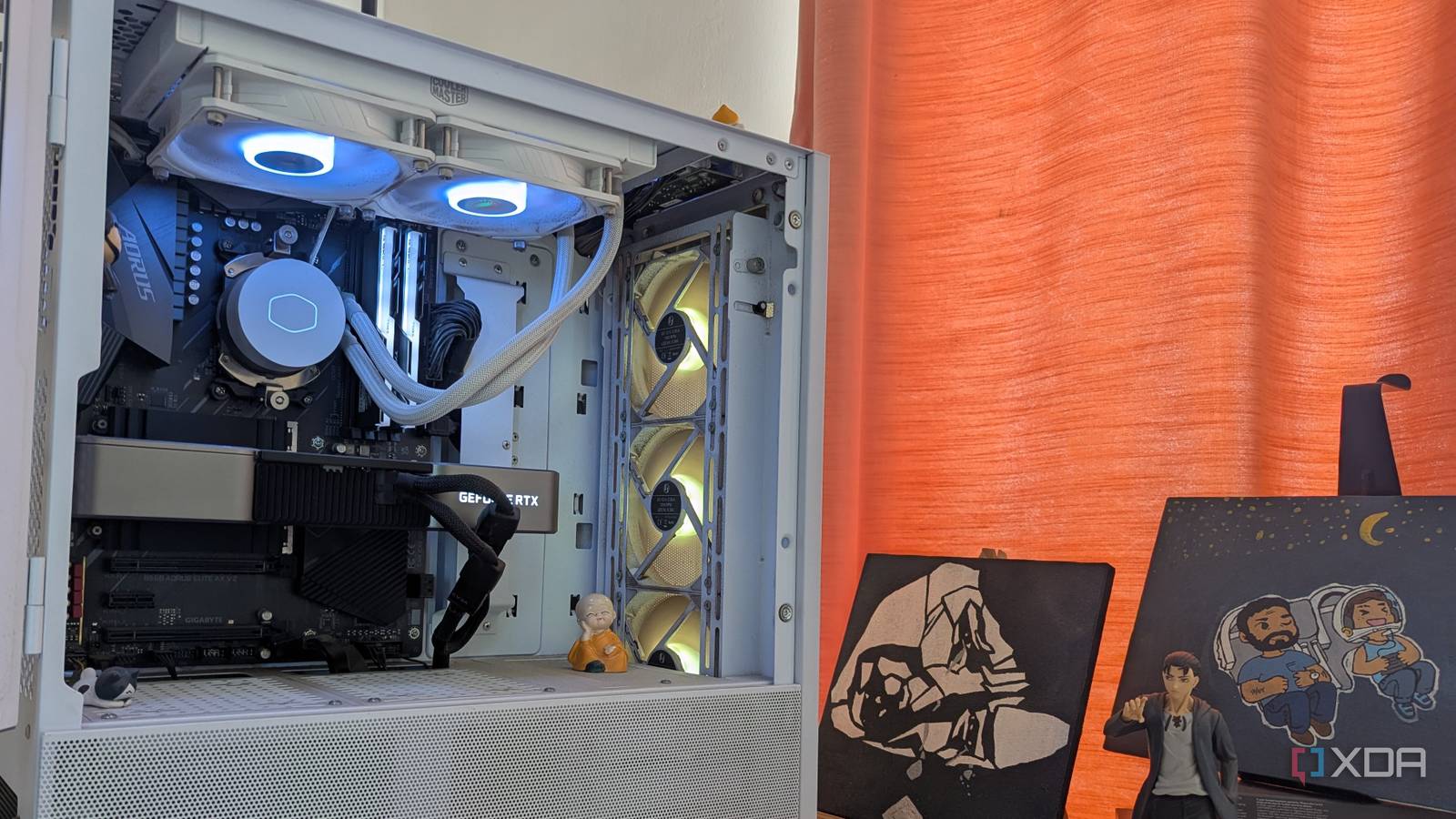

Let me talk about something that rarely gets enough attention: thermal design and cooling solutions.

A Ryzen 5 9600X, despite its 65-watt TDP, still needs active cooling. You can't just run a fanless or passively cooled system. You need a heatsink, ideally a decent one, and an appropriately sized case to move air through it.

The Noctua NH-U9S I spec'd out is a good cooler. It's compact, it's quiet, it performs well. It costs

The Machenike Mini PC specifically uses a compact form factor. That's harder to cool. The small footprint demands more engineering. And somehow, they've done it at $379 including the OS.

When a DIY builder spec's out a system, we default to off-the-shelf solutions. Noctua, Be Quiet, Arctic. These are quality products, but they're premium products. A prebuilt manufacturer integrates custom thermal solutions that cost a fraction of what consumer-grade coolers run, because they're making thousands of them.

It's another economy-of-scale advantage that evaporates the moment you go DIY.

The Motherboard Equation: Complexity vs. Cost

Let's talk about motherboards, because they're deceptively complex in this analysis.

A Ryzen 5000-series processor requires a compatible motherboard. The options are X570, B650, B850, A620. I went with A620 because it's the budget option. The ASRock A620M I selected is about $85.

Now, manufacturers like Machenike don't necessarily use brand-name boards you'd recognize. They have relationships with Chinese OEMs who produce custom boards optimized for specific form factors and use cases. These boards are engineered specifically for machines like the Machenike Mini PC. They don't need to be flashy or feature-complete. They need to be stable and cheap.

But here's the thing: when you're building a DIY system, you're shopping for general-purpose boards. You want upgradeability, you want future compatibility, you want features you might use eventually. A Machenike Mini PC isn't designed for upgradeability. You're not going to pull out a 6-core Ryzen and pop in a 16-core chip later. The thermals won't support it, the power delivery won't support it, the form factor won't support it.

So the manufacturer ships a board that's optimized purely for the system it's in. Your board needs to be future-proof.

That future-proofing is baked into the cost. And it's a cost that doesn't benefit you if you never actually upgrade.

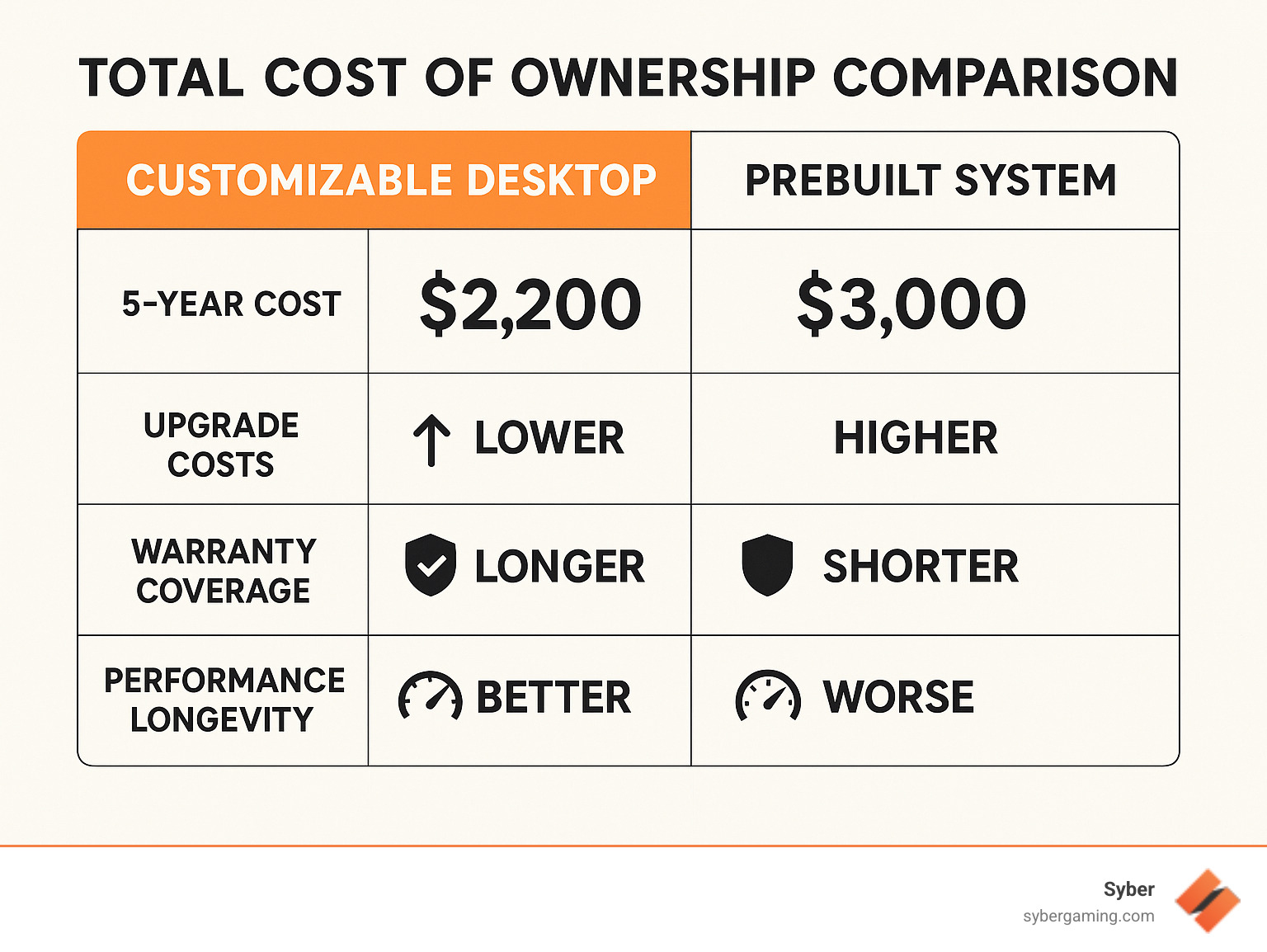

In 2024, the cost of building a DIY PC was nearly 50% higher than purchasing a prebuilt machine, highlighting a significant shift in the PC market economics. Estimated data.

Operating System Costs: The Hidden Expense

I excluded the Windows license from my initial $568 calculation. I should have included it, because it's a real cost.

A legitimate Windows 11 Home license runs about

Add

That's an 81% premium over the prebuilt. And I still haven't accounted for assembly time.

Now, there are people who'll argue: "Just install Linux, install Windows unactivated, buy a cheap OEM key, use a workaround." Sure, you can do those things. Some of them are legitimate, some are ethically gray, some are straight-up piracy. But for average users, Windows is necessary, and Windows costs money.

The prebuilt manufacturer bundles it in. Your DIY build requires you to source it separately.

The Assembly Labor: Your Time Has Value

This is where discussions about DIY usually get hand-wavy. People say, "Well, I enjoy building, so my time doesn't count," or "My time is worthless."

Your time isn't worthless. Even if you genuinely enjoy building PCs, even if you find the process fun and relaxing, there's still an opportunity cost.

Assembling a PC from components takes time. If you're experienced, you're probably looking at 30-45 minutes for a simple build like the 9600X system I spec'd out. If you're less experienced, you're at 1.5-2 hours.

Then there's first-boot troubleshooting. Sometimes everything works perfectly. Sometimes you discover a RAM stick isn't quite seated properly, or the CPU mounting bracket needs adjustment. This can add 15-30 minutes.

Then there's Windows installation and driver loading. You're pulling drivers for the motherboard, GPU, chipset, and any other hardware-specific software. You're installing Windows from scratch, activating it, configuring it. This is easily 30-45 minutes for someone who's done it before.

So you're looking at 2-3 hours minimum for the whole process, more realistically.

What's your time worth? If you make

The Machenike arrives assembled, tested, and ready to use. You unbox it, you plug it in, it works. That's a concrete, real advantage that's invisible in most pricing discussions.

DDR5 prices have decreased since their introduction but remain higher than DDR4, highlighting the economy of scale benefits for prebuilt manufacturers. Estimated data based on market trends.

The Warranty and Support Gap

When you buy a prebuilt, you buy a warranty. The Machenike comes with support and a return policy through Amazon, plus manufacturer support.

When you build your own, each component has its own warranty. Your CPU has a warranty with AMD. Your RAM has a warranty with Kingston. Your SSD has a warranty with Samsung or whoever. Your motherboard has a warranty with ASRock. Your case has a warranty with the case manufacturer. Your power supply has a warranty with whoever made it.

Sounds good, right? Lots of warranty coverage.

But here's the problem: if your system doesn't work, whose fault is it? Is it the motherboard? Is it the power delivery? Is it a BIOS issue? Is it the RAM? Did you install something wrong?

Diagnosing a broken DIY build requires technical knowledge. You need to troubleshoot systematically. You need to isolate which component is actually failing. You need to contact the right manufacturer with the right information. If a component is under warranty, the manufacturer will probably replace it, but the process involves shipping it back, waiting for a replacement, and meanwhile, you're without your computer.

With a prebuilt, you contact the seller or manufacturer, describe the problem, and they either replace the whole unit or send a technician. There's a single point of contact. There's a single warranty to manage.

That's a real advantage for non-technical users, and honestly, it matters more than a lot of DIY discussions acknowledge.

The Supply Chain Reality: Why Manufacturers Win

Manufacturers like Machenike work with suppliers in ways individual builders can't replicate.

They have contracts. They have volume commitments. They're placing orders for thousands of units, and that gives them negotiating power. When the DDR5 market is tight, the large manufacturers get allocation first. When new CPUs launch, the manufacturers have priority for stock.

For individual buyers, the supply chain is whatever's available on Newegg, Amazon, or other retail sites. You're buying into the remaining inventory after OEMs, system integrators, and large businesses have already taken their allocation.

This became especially visible during the GPU shortage and the RAM crisis. Individuals couldn't get components at any price. Manufacturers kept shipping systems because their supply contracts guaranteed them allocation.

That supply chain advantage has normalized somewhat now, but it hasn't disappeared. Large manufacturers still get better pricing, better availability, and better allocation than individuals.

It's not just about bulk discounts on price. It's about access to inventory itself.

The DIY build costs

The Mini PC Form Factor: Engineering Advantage

The Machenike is specifically a mini PC. That's not incidental; it's a deliberate form-factor choice that has real implications.

Mini PCs are harder to engineer than full-size towers. You need to be more careful with thermal design, with component placement, with cable routing. But here's the advantage: if you're making thousands of mini PCs, you've amortized the engineering cost across all of them.

The engineers who designed the Machenike's case, its motherboard layout, its cooling system, its power delivery, they did that work once, and then that design gets replicated in thousands of units.

When you build a DIY system, you're starting from zero. You're selecting a generic case that was designed to work with any motherboard, any power supply, any collection of components. You're using a generic motherboard that was designed to work in any case, with any CPU, in any scenario.

The generic design is more flexible, but it's not optimized. It's a trade-off.

For a $379 price point, the manufacturer couldn't afford to use a generic case and generic motherboard. The whole system had to be purpose-built and optimized. And that optimization is baked into the final product.

Benchmark Reality: Performance Doesn't Scale With Price

Let me circle back to the actual performance metrics.

On Passmark, the 8745HS scores around 29,000 points. The 9600X scores around 29,900 points. In real-world usage, you'd be hard-pressed to notice the difference in everyday tasks.

What this tells us is that performance has plateaued for typical user workloads. An eight-core mobile processor from 2024 is sufficient for video streaming, document editing, web browsing, photo organization, and light video editing. Adding more cores, higher clock speeds, and extra power consumption doesn't translate into meaningfully faster user experience.

The Machenike at $379 gives you a performance ceiling that's actually quite high. You're not bottlenecking at the CPU for most tasks. The limitation is usually I/O, or network, or just how fast the software itself can go.

For a typical user—and this is most people—the Machenike isn't a compromise. It's a better deal.

For a professional who regularly does CPU-intensive work, the calculus changes. But for most people, the $379 Machenike is legitimately the right answer, not the budget answer.

When DIY Actually Makes Sense

I've spent a lot of time explaining why DIY loses to prebuilts on price. Now let me be fair and explain when DIY actually wins.

DIY makes sense when you have specific, unusual requirements that no prebuilt manufacturer is targeting. For example:

You need workstation-class hardware for professional software. You need specific CPU configurations, specific GPU options, specific RAM capacities. You're willing to pay more to get exactly what you need, and you need it now, not when it's convenient for the manufacturer to stock it.

You're upgrading an existing system. You already have a case, a power supply, maybe a CPU or RAM. Upgrading specific components can be cheaper than buying a whole new prebuilt.

You have aesthetic or customization requirements. You want a specific look, specific cable management, specific RGB lighting, or specific form factor. If that matters to you, DIY lets you express it.

You're building a highly specialized system. A gaming PC with a specific balance of CPU and GPU, a mining rig with specific thermal requirements, a home theater PC with specific audio and video output options. These are niche enough that you're not going to find a prebuilt that matches exactly, and building custom costs less than shopping for a prebuilt that's close and then modifying it.

You enjoy the process. This is legitimate. If you get genuine satisfaction from selecting components, learning about compatibility, building the system, and optimizing it, then DIY has intrinsic value even if it costs more. Your cost premium is paying for a hobby you enjoy.

But for raw price-to-performance on a $379 budget? DIY doesn't win. The economics have shifted.

The Broader Market Implications

What I discovered with the Machenike isn't an anomaly. It's becoming the norm.

Manufacturers can buy components cheaper than retail. They can engineer custom solutions. They can optimize for scale. They can bundle Windows and support. They can accept smaller margins because volume makes up for it.

This has always been true at some level, but the gap has widened. In 2015, you could build a competitive system for less than a prebuilt. In 2020, the pricing was close enough that other factors mattered. In 2025, prebuilts have a structural advantage that's hard to beat on price alone.

That's bad news for DIY enthusiasts. It's good news for consumers who want access to good computers at affordable prices.

The market is consolidating. Fewer people are building systems. More people are buying prebuilts. That changes supply chains, that changes what manufacturers bother to stock, that changes the retail ecosystem.

It's a feedback loop. Fewer DIY builders means less demand for high-margin component sales, which means retailers stock fewer components, which makes DIY less convenient, which pushes more people toward prebuilts.

We might be witnessing the slow-motion end of the DIY PC era, at least for budget-conscious consumers.

The Component Quality Question: Are We Actually Getting Shortchanged?

One objection DIY builders often raise: sure, prebuilts are cheaper, but what about component quality? Aren't they using cheap parts to hit the price point?

Not necessarily.

The Machenike uses a Ryzen 7 8745HS, which is a top-tier mobile processor. It uses DDR5, which is current-generation RAM. The SSD is NVMe PCIe Gen 4, which is fast. The power supply in a mini PC needs to be efficient and reliable, because it's in a tight space with limited cooling.

Are all the components premium-tier options? No. But they don't need to be. You don't need a Noctua cooler, a Corsair case, a Seasonic power supply, and a high-end motherboard for a system that's primarily going to run office work and web browsing.

A $379 prebuilt uses competent, reliable components optimized for cost. The generic heatsink is adequate for the CPU it's cooling. The generic power supply is efficient enough. The standard motherboard works fine. The SSD is fast enough.

Saving $50 on the cooler by using something generic is fine if that money goes toward including Windows and support.

The component choices in a prebuilt are optimized for the overall system. DIY builders optimize for individual components. Those are different optimization goals.

For the end user, what matters is: does the system work reliably? Does it perform well enough for the intended use case? The Machenike answers yes to both.

Making the Pragmatic Choice: DIY vs. Prebuilt Decision Framework

If you're trying to decide between building and buying, here's a decision framework that's more useful than vague guidance.

First, define your exact use case. Not "I might do photo editing someday." What specific work will you actually do? How often? Is it CPU-intensive, GPU-intensive, or I/O-intensive?

Second, price a prebuilt that meets those needs. Get the actual price, look at specs, check reviews.

Third, price a DIY system on PCPart Picker. Include everything: CPU, motherboard, RAM, storage, cooling, case, power supply, Windows license. Don't estimate; use actual prices.

Fourth, add 20% to the DIY cost to account for your time. If you value your time at

Fifth, compare the two numbers.

If the DIY system is more expensive, the question becomes: what are you getting for the premium? Better upgradeability? Better aesthetics? A specific component you really wanted? If those things matter to you, it's worth it. If not, buy the prebuilt.

If the DIY system is cheaper, it probably means you found a inefficiency in the market, or you're building a specialized system that prebuilts don't target. In that case, DIY makes sense.

But don't fall into the trap of comparing DIY to prebuilts without accounting for Windows, your time, and true-cost components. That's how you end up with a

The Future: Where DIY Heads From Here

If the structural advantages of manufacturers continue to widen, what happens to DIY?

I don't think DIY disappears entirely. But I think it becomes a niche hobby rather than a mainstream consumer choice. It'll remain attractive to people who want customization, people who enjoy tinkering, people who have specific professional needs that prebuilts can't meet.

But the average person buying a computer? They're going to buy a prebuilt. The economics make it the obvious choice.

That might mean component manufacturers start focusing less on retail consumers and more on OEM and business sales. It might mean retailers stock fewer components. It might mean the knowledge base around DIY building becomes less accessible, because fewer people are doing it.

There's also a possibility that prebuilt manufacturers become even more dominant and start using that power in ways that aren't consumer-friendly. When there's no competitive threat from DIY builders, there's no incentive for manufacturers to keep prices low or features accessible.

But for now, in 2025, the pragmatic answer is clear: the $379 Machenike Mini PC is better value than a DIY equivalent. That might not be fun to admit if you love building, but it's true. And understanding why it's true—understanding the economics, the supply chains, the engineering realities—helps you make better decisions about future purchases.

Your time is valuable. Your labor is valuable. Windows licenses cost money. Component manufacturers have advantages individuals can't replicate. Those are facts, and they all point in the same direction: for most people, at most price points, buying a prebuilt is smarter than building.

Actionable Takeaways: What You Should Actually Do

If you're in the market for a new computer, here's what to actually do instead of getting lost in pricing comparisons.

If you need a basic workstation and budget is tight: just buy the Machenike or something similar. Don't fool yourself into thinking you can build better for less. The math doesn't work anymore.

If you need something more powerful than a budget prebuilt: look at prebuilts in the $800-1500 range. At that price point, you're getting more CPU, maybe a dedicated GPU, more RAM. Compare actual prebuilts before you start spec'ing DIY. You might be surprised how much value is available.

If you want to build but are budget-conscious: clearly identify what you want to customize or why you need specific components. Make sure that reason justifies the premium. Don't build just because you like building and then pretend it's the budget option.

If you genuinely enjoy building: build. Accept that it costs more, see it as a hobby expense, and enjoy the process. But don't rationalize it as the economical choice. Be honest about what you're paying for.

If you're a professional who needs specific workstation capabilities: spec carefully on both sides and make the call based on actual requirements. This is where DIY still has a chance to win.

But for everyone else—for the person who just needs a computer that works, that doesn't need tweaking, that comes with support and warranty and Windows already installed? Buy the prebuilt. Let the professionals optimize the system. Pocket the savings. Use your time on something that matters to you.

That's not giving up on DIY. That's being pragmatic in 2025.

FAQ

What makes the Machenike Mini PC such a good value?

The Machenike offers genuine performance from a Ryzen 7 8745HS processor, modern DDR5 RAM, and fast NVMe storage all for $379 with Windows included. The value comes from manufacturer optimization: they've engineered the entire system as a cohesive unit rather than combining generic parts, their bulk purchasing power reduces component costs far below retail, and they can absorb a smaller margin across thousands of units. For typical users doing web browsing, streaming, document work, and light content creation, the performance ceiling is high enough that you're not sacrificing capability—you're just not paying for unnecessary customization.

Why can't DIY builders compete on price anymore?

The economics have shifted fundamentally. Manufacturers buy components in bulk at prices individual consumers can't access, they negotiate directly with suppliers rather than buying through retail channels, and they can engineer systems optimized purely for their use case rather than general-purpose solutions. Additionally, individual builders must source Windows separately (

Is the DDR5 RAM in the Machenike expensive?

Retail DDR5 is expensive for individuals—a 16GB kit costs around $100. But manufacturers buy DDR5 at a fraction of that price through bulk contracts directly with NANYA, Samsung, or SK Hynix. That's a real, structural advantage that can't be replicated by individual buyers shopping on Newegg or Amazon. The retail channel adds distribution, logistics, and retailer margins that disappear when you're ordering thousands of units at once.

How much faster is the Ryzen 5 9600X compared to the Ryzen 7 8745HS?

On Passmark multi-core benchmarks, the 9600X (desktop) scores around 29,900 points while the 8745HS (mobile) scores around 29,000 points—just 3% difference despite the 9600X having 50% higher power consumption and lower core count. The 9600X dominates in single-thread performance (15-20% faster), which matters for some applications, but for productivity tasks, data processing, and content pipelines, the 8745HS's eight cores partially offset its lower clocks. For typical users, the performance difference is academic.

Should I always buy prebuilt instead of building?

Not always, but in most cases at the budget end of the market, yes. DIY still makes sense if you have specific customization needs, unusual workstation requirements, want upgradeability for future-proofing, enjoy the building process as a hobby, or are upgrading existing components rather than starting from zero. But if you're looking for raw price-to-performance on a limited budget and your use case is typical, a prebuilt is economically smarter. Be honest about your actual needs rather than rationalizing an expensive DIY project as the budget option.

What about warranty and support with prebuilts?

Prebuilts offer simplified support through a single manufacturer or retailer, standardized warranty coverage for the whole system, and clear troubleshooting paths. DIY systems require you to diagnose which component failed, manage multiple separate warranties, contact multiple manufacturers, and handle logistics yourself. For non-technical users, this is a concrete advantage worth factoring into pricing. For tech-savvy users who enjoy troubleshooting, it's less of an issue, but it's still a real consideration.

Can I upgrade the Machenike Mini PC later?

Mini PC form factors are generally not upgrade-friendly. The power supply, cooling solution, and motherboard are optimized specifically for that case and system configuration. You likely can't add more RAM, can't upgrade to a larger storage drive beyond what's already there, and can't swap the CPU. That's by design—it lowers costs and engineering complexity. If future upgradeability matters to you, that's a legitimate reason to consider DIY, but accept the cost premium that comes with it.

How do I actually compare DIY and prebuilt fairly?

Price the prebuilt you want. Then on PCPart Picker, price every component for an equivalent DIY system: CPU, motherboard, RAM, storage, cooling, case, power supply, and Windows license. Add 20% to the DIY total to account for your assembly time (adjust based on your hourly rate). Compare the final numbers. That's a fair comparison. Most people are shocked to discover the DIY system costs significantly more when you include components they forgot about and time they didn't value.

What's the actual failure rate of prebuilt mini PCs?

Prebuilt mini PCs from established brands like Machenike have reasonable reliability for their price point, typically in the 2-5% defect-on-arrival range depending on the manufacturer. They're not premium-tier reliability—those failure rates are closer to 0.5-1%—but they're not disposable either. The real advantage is that any defects are the manufacturer's problem to fix, not yours to diagnose and repair. Your risk is time without a computer during RMA, not technical headache.

Is there ever a scenario where DIY is obviously the right choice?

Yes. If you need workstation-class hardware with specific GPU requirements, specific RAM capacities, or unusual configurations, DIY can still win. If you're upgrading an existing build rather than starting from scratch. If you have components already on hand. If you want a specific aesthetic or have customization needs. If you're building something highly specialized that no prebuilt manufacturer targets. But "I want to save money on a general-purpose computer"? That's not a scenario where DIY wins anymore.

Key Takeaways

- Manufacturers negotiate bulk component pricing individual DIYers can't access, creating structural economic advantage

- Including Windows license and assembly labor makes typical DIY builds cost 80% more than comparable prebuilts

- DDR5 RAM shortage created supply chain bottlenecks where manufacturers get better allocation and pricing than retail customers

- The Ryzen 7 8745HS mobile processor matches nearly all desktop CPU performance while using half the power consumption

- Mini PC form factors allow manufacturers to optimize for specific systems rather than using generic components

- DIY remains viable only for specialized workstations, upgrading existing systems, or as a hobby where cost premium is acceptable

- Modern prebuilts include warranty support and quality components at price points where custom builds simply can't compete

![Building vs Buying a Mini PC: Why DIY Lost to Prebuilts [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/building-vs-buying-a-mini-pc-why-diy-lost-to-prebuilts-2025/image-1-1766849757452.jpg)