The Sky-Based Power Station You Didn't Know Was Coming

Picture this: instead of massive wind turbines dotting hillsides and coastlines, your electricity comes from a giant drone-like airship floating 2 kilometers above your city. Sounds like science fiction? A Chinese company just made it real.

In early January 2026, Beijing-based Linyi Yunchuan Energy Technology completed what might be the most significant breakthrough in renewable energy since solar panels went mainstream. Their S2000, short for Stratosphere Airborne Wind Energy System (SAWES), rose to 6,560 feet near Yibin in China's Sichuan Province and fed 385 kilowatt-hours of electricity directly into the grid. It's the world's first megawatt-class airborne wind turbine designed to actually power homes and businesses, not just prove a concept works.

This isn't some fringe experiment hidden in a research lab. The system is already moving into small batch production, with the company scaling manufacturing capacity for envelope materials in Zhejiang Province. Investors are watching. Energy companies are paying attention. Grid operators are running the numbers.

Here's what makes this different from the dozens of failed airborne wind projects that came before: it works. It actually generates power. It feeds into existing electrical infrastructure. And it does all of this at a scale that matters.

For decades, scientists and entrepreneurs have chased the promise of harvesting wind at higher altitudes where it's stronger and more consistent. The reality has always been messier. Tethered kites crashed. Airborne turbines destabilized. Complex systems broke before they generated enough power to justify their existence. The S2000 breaks that pattern.

What we're looking at isn't just a new technology. It's a fundamental rethinking of where we can build renewable energy infrastructure. It opens possibilities for urban deployment, remote locations, and distributed energy systems that traditional wind farms simply can't reach. And it arrives at exactly the moment when energy demand is accelerating faster than conventional capacity can expand.

TL; DR

- First Real Success: S2000 completed maiden grid-connected flight, generating 385k Wh at 2km altitude

- Scale That Matters: System achieves up to 3MW rated capacity, not prototype-grade power

- Urban Ready: Compact design (197ft x 131ft) enables deployment near cities, unlike traditional turbines

- Novel Architecture: 12 ducted turbines capture wind from all angles, maximizing efficiency at height

- Production Phase: Small batch manufacturing underway with expanded capacity planned

- Dual Applications: Targets both off-grid remote locations and integration with conventional wind farms

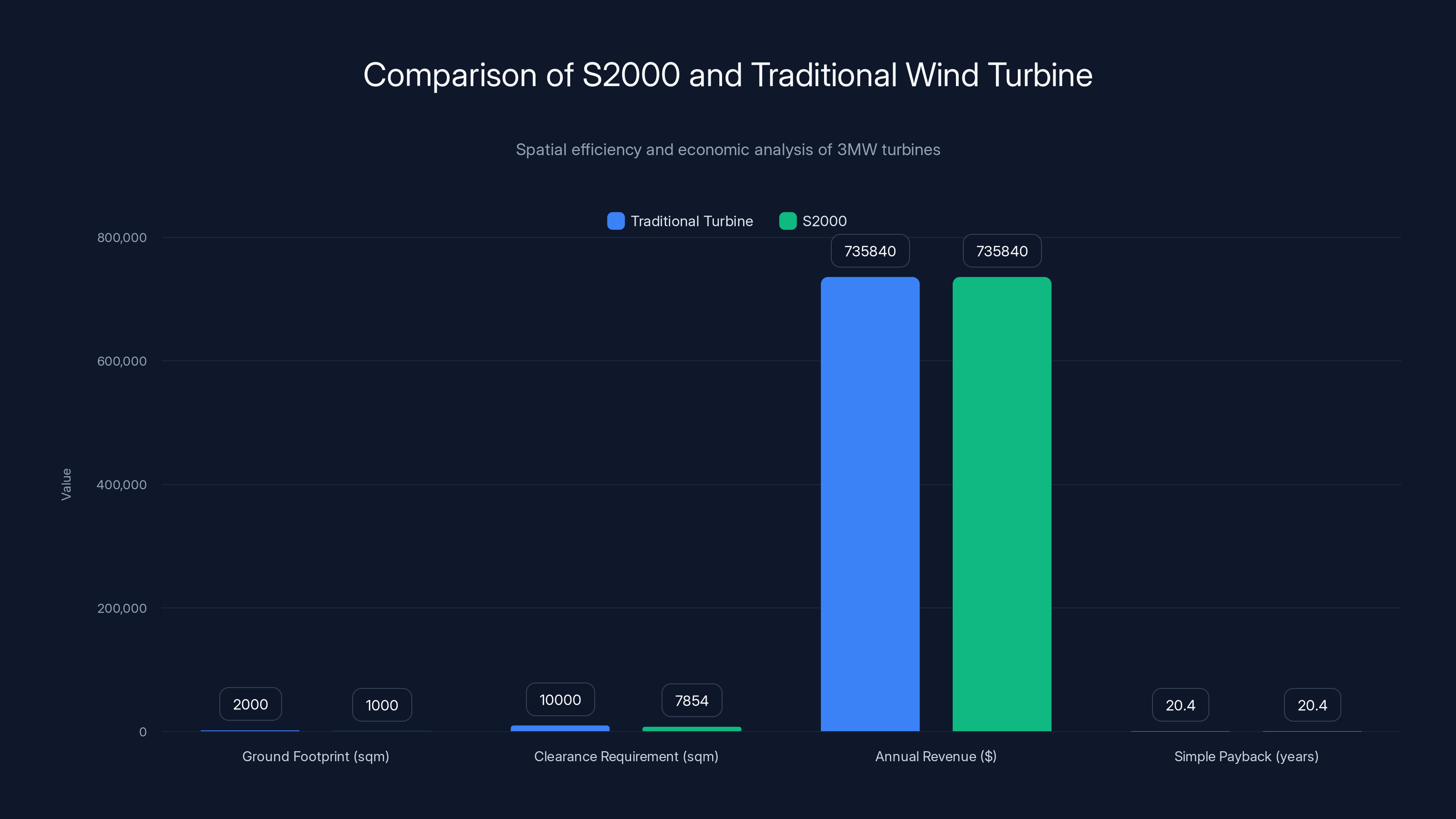

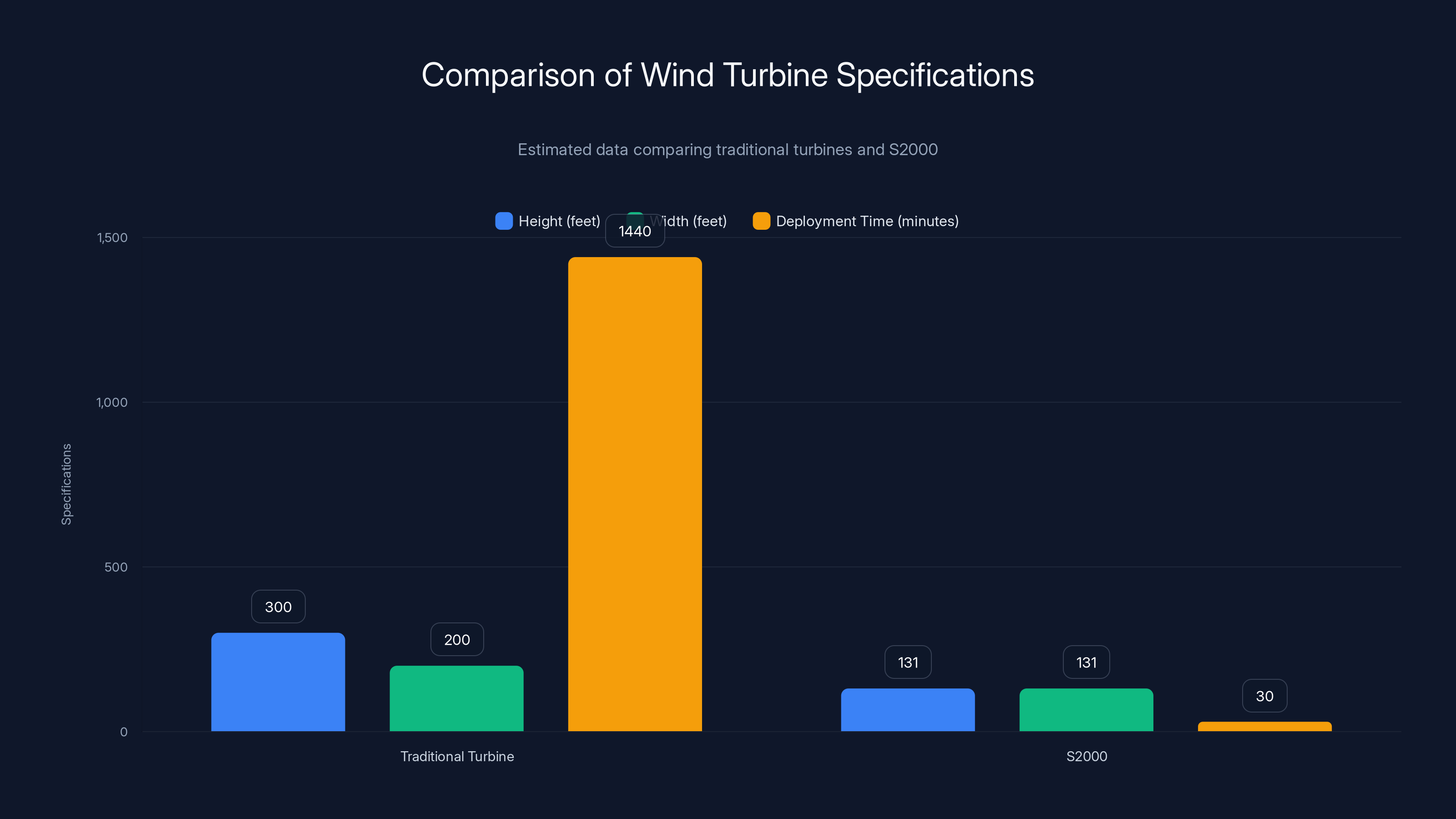

The S2000 offers a smaller ground footprint and clearance requirement compared to traditional turbines, potentially enabling deployment in more diverse locations. Both systems have similar revenue and payback periods, but S2000's cost-effectiveness could improve with scaled manufacturing.

How Airborne Wind Energy Challenges Everything We Know About Power Generation

Wind energy has a fundamental problem that nobody really talks about at cocktail parties, but energy engineers lose sleep over it: ground-level wind is inconsistent. A traditional turbine at 300 feet altitude catches wind that varies wildly depending on terrain, buildings, vegetation, and time of day. You get power generation that fluctuates, requiring expensive battery storage and grid management systems to smooth out the volatility.

Now climb higher. At 2 kilometers, wind becomes predictable, steady, and powerful. The jet stream carries consistent energy that barely changes throughout the day. This is the fundamental physics driving airborne wind development. You're not fighting terrain and friction anymore. You're harvesting from an energy layer that's been waiting to be tapped.

But getting there has been brutally difficult. Kite-based systems offered simplicity but lacked control and stability. Tethered turbines worked in theory but faced catastrophic failures when wind conditions shifted unexpectedly. Most airborne wind startups from the 2010s either pivoted to different technologies or disappeared entirely. The engineering challenges were just too severe.

The S2000 solves this through elegant simplification. Instead of treating the airborne platform as a traditional turbine hanging from a tether, Linyi Yunchuan designed it as a complete aerial system. The helium-filled aerostat (the giant envelope you see) isn't just lifting equipment. It's part of the power generation structure. The tether does double duty: transmitting electrical power and actively stabilizing the platform's position.

This hybrid approach addresses what killed previous systems: stability management at altitude. When wind gusts arrive, the platform doesn't fight them like a rigid turbine would. The design absorbs and manages those forces through multiple systems working in concert. The helium envelope provides constant buoyancy. The tether keeps it positioned. The ducted design channels wind efficiently. Everything works together instead of fighting each other.

The result is the first system that doesn't crash when real wind shows up.

The Revolutionary Ducted Turbine Design: Wrapping Wind From All Sides

Here's where the S2000 gets genuinely clever. Instead of exposed rotor blades catching wind from one direction like a conventional turbine, Linyi Yunchuan built 12 turbines inside a ducted system formed between the main envelope and an annular wing structure.

Think of it like this: a traditional turbine is like trying to catch rain with a bucket. You get what falls in the opening. The S2000's duct is like a funnel. Wind approaches from multiple angles, the annular wing guides it inward, and all that air flows through the turbine blades. The system captures wind energy regardless of the direction it approaches from. Weng Hanke, the company's chief technology officer, described it perfectly: "It's like wrapping the wind from all sides, constraining the airflow within this duct so that as much wind as possible is captured by the blades."

This design choice creates several advantages that show up in real performance:

Efficiency gains from three-dimensional airflow. Traditional wind turbines operate on two-dimensional principles—wind hits the rotor disk from one direction. The ducted design adds a vertical component. Wind can be captured as it spirals and moves through the channel, not just as it passes the rotor. This translates directly to more electrical output from the same wind resource.

Reduced noise and vibration. The duct acts as an acoustic dampener and smooths turbulent airflow before it hits the blades. A traditional turbine exposed to raw wind produces distinctive whooshing sounds that carry for miles. The S2000 operates far more quietly, making it suitable for deployment near populated areas.

Structural efficiency and reduced material requirements. Instead of massive blades spanning hundreds of feet, the system uses 12 smaller turbines distributed around the duct. Smaller blades need less material, cost less to manufacture, and create fewer structural stresses on the entire system. The overall platform becomes lighter and more manageable.

Improved safety in turbulent conditions. When wind shifts rapidly—which happens constantly in the real atmosphere—distributed smaller turbines adjust and balance load far more naturally than one giant rotor would. It's like having 12 shock absorbers instead of one big spring. The system stays stable when conditions get chaotic.

The helium volume supporting this design reaches nearly 20,000 cubic meters. For scale, that's equivalent to a cube approximately 271 feet on each side, or roughly 6 large buildings stacked together. That massive buoyancy provides not just lift, but the capacity to carry 3 megawatts of generation equipment to operational altitude.

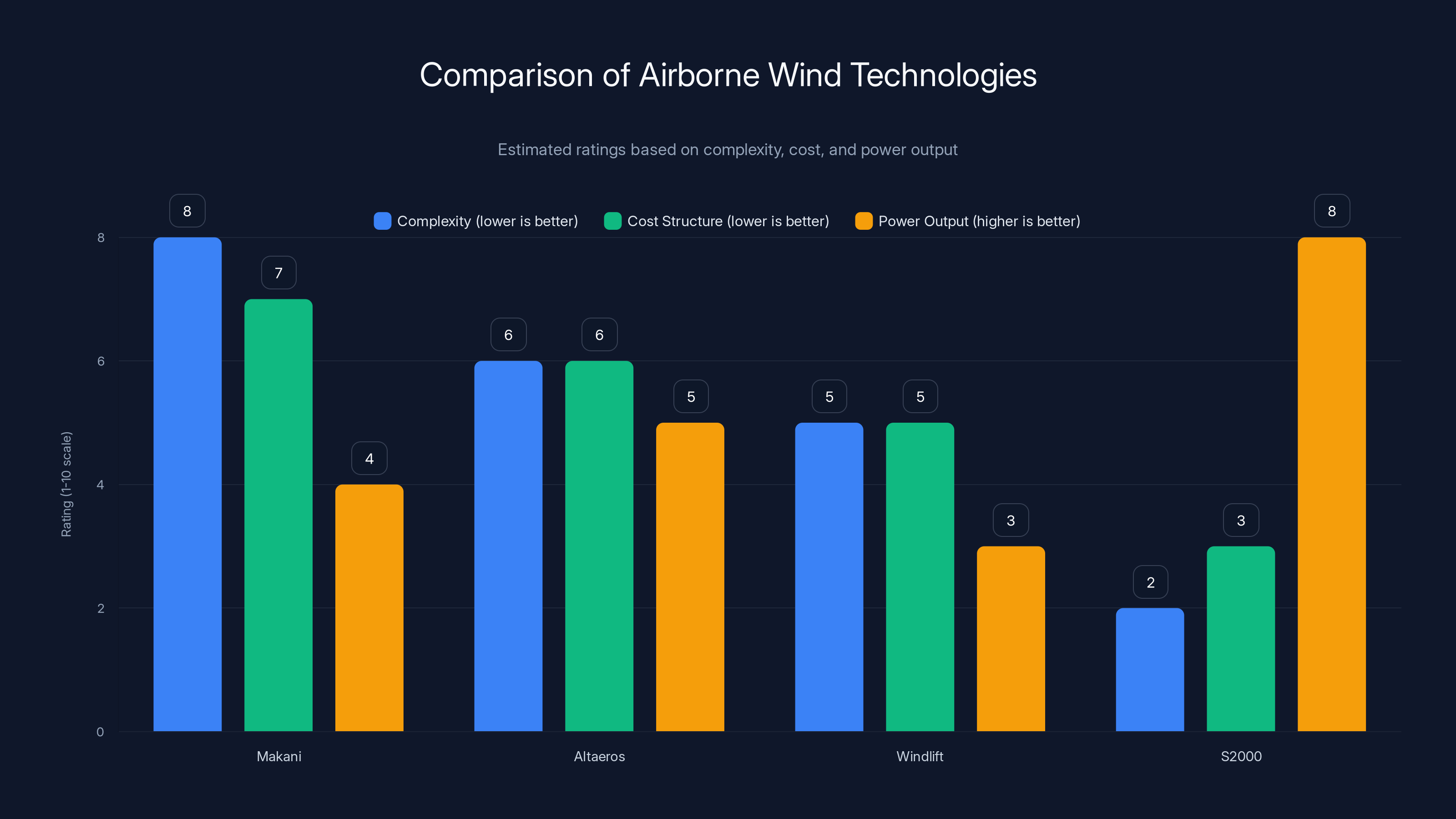

The S2000 stands out with lower complexity and cost, while achieving higher power output compared to other airborne wind technologies. Estimated data.

The Physical Specifications That Make Grid Connection Possible

Size matters when you're trying to fit a power generation system into existing urban and rural spaces. A traditional modern wind turbine spans 200+ feet across and requires minimum 300 feet of clearance in all directions. Communities don't want them nearby. Regulations restrict placement. Infrastructure constraints limit deployment options.

The S2000 measures approximately 197 feet long and 131 feet wide and high—roughly the footprint of a large commercial building. That's not small, but it's dramatically more compact than ground-based alternatives. This dimensional efficiency has real-world consequences:

Urban deployment becomes feasible. You can imagine placement on industrial complexes, near ports, above manufacturing facilities, or on land adjacent to cities without consuming the massive spatial footprint traditional turbines demand. That opens energy generation possibilities in locations where conventional wind farms would be zoned as nuisances.

Remote installation simplifies dramatically. A tethered airborne system requires ground anchoring and tether infrastructure, but not roads capable of transporting 200-ton nacelles and 100+ foot blade sections. Remote locations like border outposts, mountain regions, and maritime platforms become viable deployment zones.

The tether itself becomes infrastructure. Traditional turbines need expensive electrical transmission infrastructure to move power from generation site to grid. The S2000's tether transmits power directly upward through a single connection point. Installation complexity drops sharply.

During the maiden grid-connected test, the system took approximately 30 minutes to ascend to operational altitude. Let that sink in: 30 minutes from ground position to full power generation. No infrastructure needed. No construction cranes. No multi-year installation projects. That speed of deployment, multiplied across hundreds of units, fundamentally changes how quickly you can respond to energy demand fluctuations.

Once at altitude, the platform maintained stable hover while continuously generating electricity. The test wasn't a quick proof-of-concept sprint. This was real operational duration, real load on the grid, real performance data. The 385 kilowatt-hour generation during the test might not sound revolutionary compared to a single massive ground turbine, but remember: this is iteration one of a production system, not a prototype. Scale and optimization haven't even begun.

Why 2 Kilometers Altitude Represents the Sweet Spot

Almost everyone initially asks the wrong question: "Why not go higher?" The answer reveals fundamental physics about wind energy that doesn't get mainstream attention.

Wind speed generally increases with altitude, but the relationship isn't linear. At sea level, friction from terrain and obstacles creates turbulence. Wind speeds accelerate rapidly as you climb. But there's a zone—typically between 1.5 and 3 kilometers—where three factors align optimally: strong, consistent wind; manageable structural loads on the tether and platform; and reasonable power transmission losses through the tether.

Go beyond that sweet spot and problems multiply. Tether material becomes exponentially more expensive. Stress loads on the system accelerate. Atmospheric conditions become less predictable. The power required to manage and control the system erodes efficiency gains from higher wind speeds.

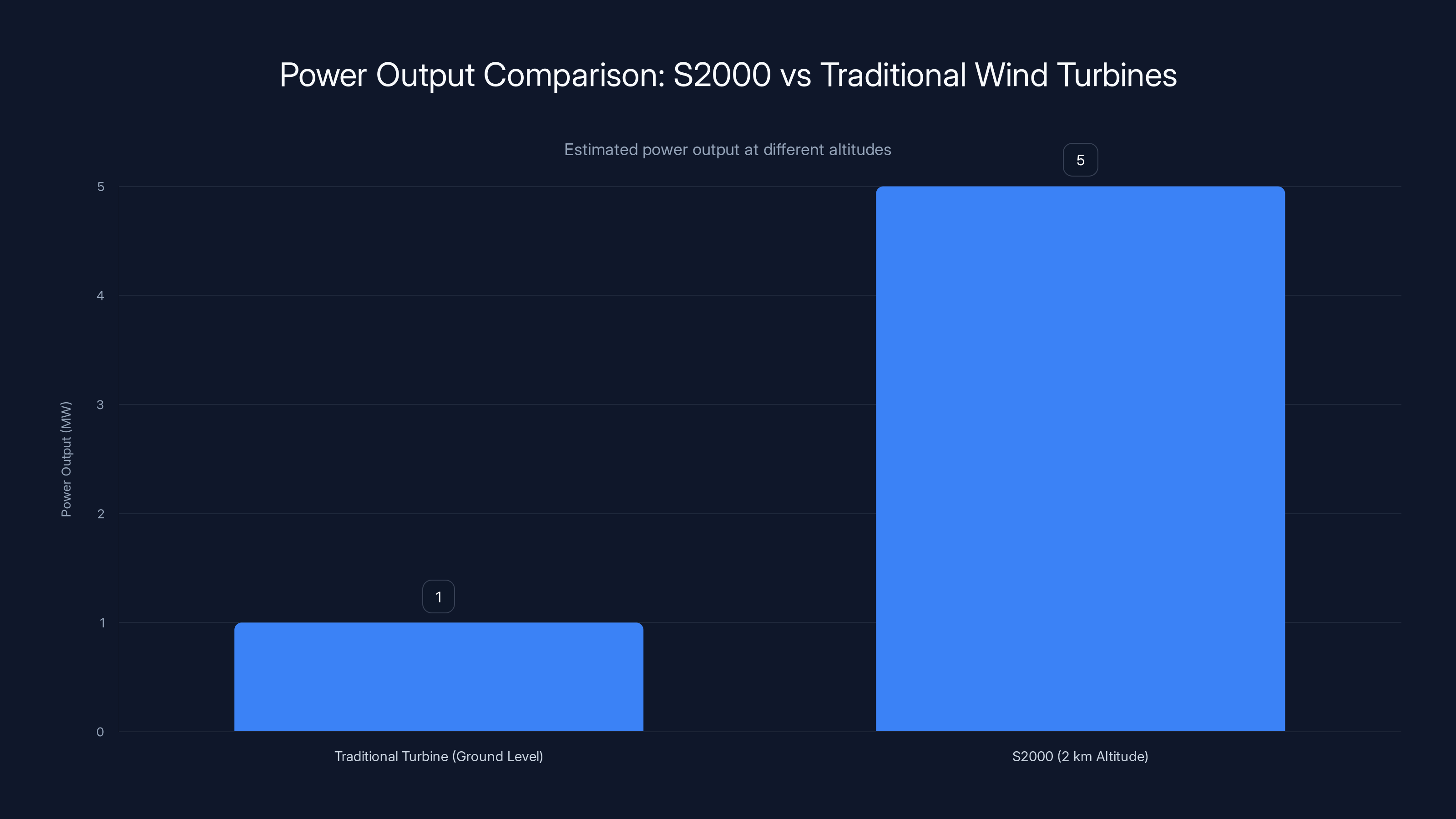

Two kilometers hits the intersection point where you capture substantially stronger and more consistent wind than ground-based turbines, but you're not fighting physics that makes the system unmanageable or economically irrational.

At this altitude, wind speeds typically average 9-12 meters per second, compared to 4-7 meters per second at ground level where traditional turbines operate. That's roughly double the wind resource. Power output scales with wind speed cubed, meaning that doubling translates to roughly 8 times the potential energy.

Of course, the tether requires energy to manage and loses some power transmission efficiency. The system doesn't achieve a clean 8x multiplier. But even at 60% efficiency compared to theoretical maximum, you're looking at 3-4x the power output of equivalent ground-based systems in the same location.

The tether itself becomes a key engineering feature rather than just a cable. It provides:

- Electrical transmission: High-voltage wires built into the tether structure transmit power with minimal losses

- Active positioning control: Mechanical and hydraulic systems manipulate tether tension and angle, allowing the platform to position itself optimally for wind capture

- Load distribution: Rather than one rigid connection point, distributed attachment points along the tether spread structural loads more evenly

- Emergency failsafe: In extreme conditions, controlled tether descent brings the system to ground safely

The engineering choice to keep operations at 2 kilometers isn't a limitation. It's optimization based on real physics and practical economics.

The Grid Connection Revolution: From Prototype to Production Infrastructure

Most airborne wind concepts exist in a weird regulatory limbo. They're not quite aircraft (they're tethered and stationary). They're not quite traditional power generation (they're airborne). Grid operators don't know how to classify them, let alone connect them.

The S2000's successful grid connection represents a massive breakthrough that goes completely unnoticed by people outside the energy sector: the system proved it can work with existing electrical infrastructure. That one accomplishment opens doors that fifteen years of lab demonstrations never could.

Here's why grid connection matters so much. Most tethered turbines and experimental airborne systems generate power, but they generate it in unstable, unpredictable ways. Grid operators need consistency. They need to know when power will be available. They need systems that won't suddenly drop load and cause cascading failures across the network.

The S2000's control systems managed:

Load ramping. Power output didn't spike suddenly when the system reached altitude. Instead, generation increased gradually, allowing the grid to absorb the new capacity without instability.

Frequency regulation. The system maintained proper electrical frequency while injecting power, matching the grid's requirements exactly.

Voltage stability. The connection didn't create voltage fluctuations that would damage sensitive equipment downstream.

Protective disconnection. In case of wind gusts, equipment failures, or other problems, the system could safely disconnect from the grid without causing downstream issues.

Accomplishing all of this while tethered at 2 kilometers altitude, with dynamic wind conditions constantly changing, represents serious engineering maturity. The team didn't just build a generation system. They built a grid-integrated system that plays by the electrical rules real power networks demand.

That distinction separates toys from infrastructure. And it's why Linyi Yunchuan is already moving into production.

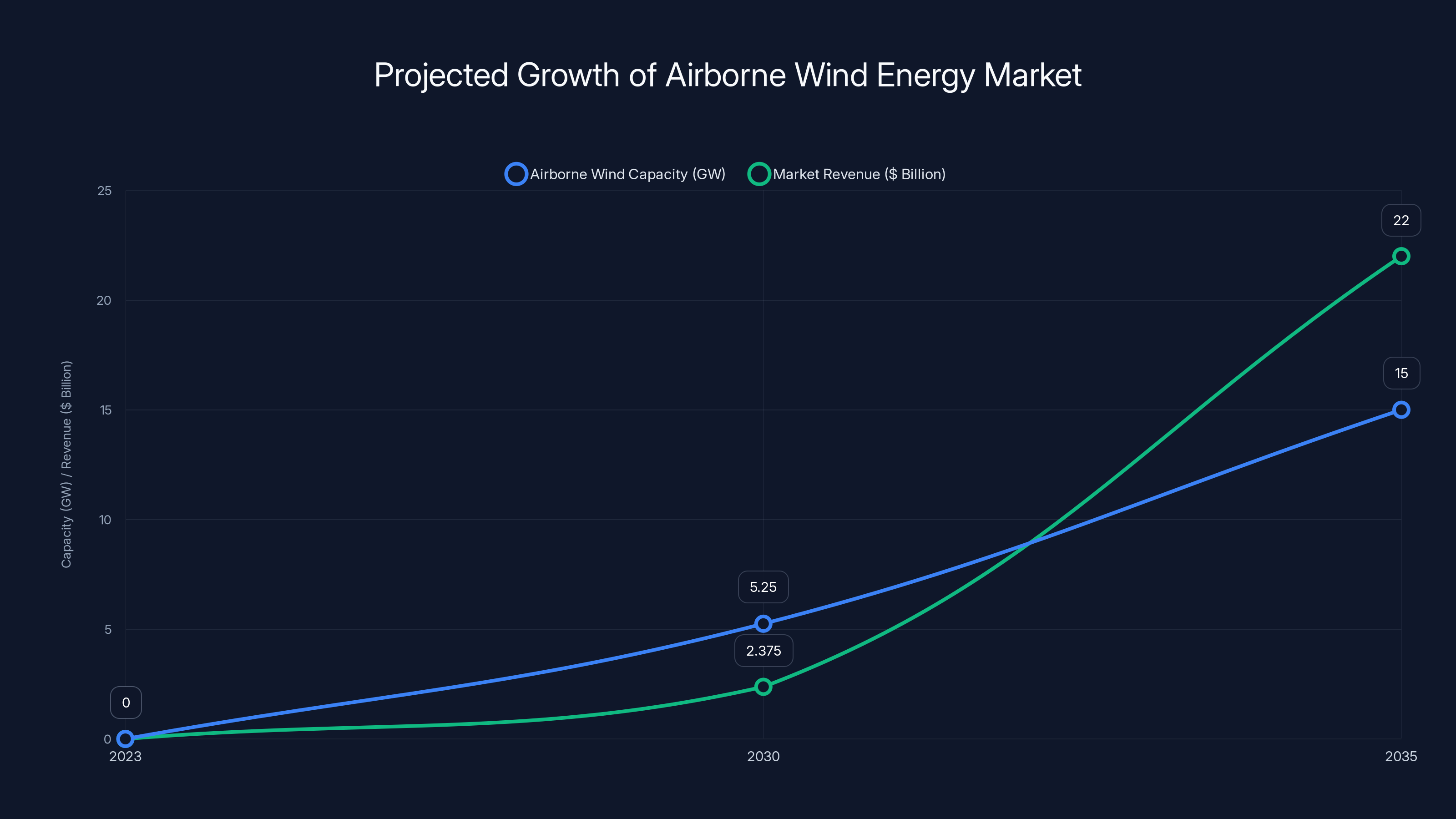

The S2000 airborne wind turbine can generate approximately 3-8 times more power than traditional ground-based turbines due to stronger and more stable winds at high altitudes. Estimated data.

Dual Application Strategy: Off-Grid Remote Locations and Grid Integration

Linyi Yunchuan's leadership sees two distinct markets where the S2000 creates value propositions that rival solutions simply can't match.

First market: Off-grid applications in remote and hostile environments.

Border outposts, scientific research stations, and isolated communities face brutal logistics for energy supply. Traditional diesel generators require constant fuel transportation through difficult terrain. Solar panels suffer from poor efficiency in many regions. Ground-based wind farms demand massive infrastructure investments.

An airborne wind system addresses every one of those constraints. It requires no fuel supply chain. It works in cloudy conditions where solar fails. It generates meaningful power without extensive ground infrastructure. For remote military installations, research outposts, or frontier communities, deploying an S2000 system transforms energy independence.

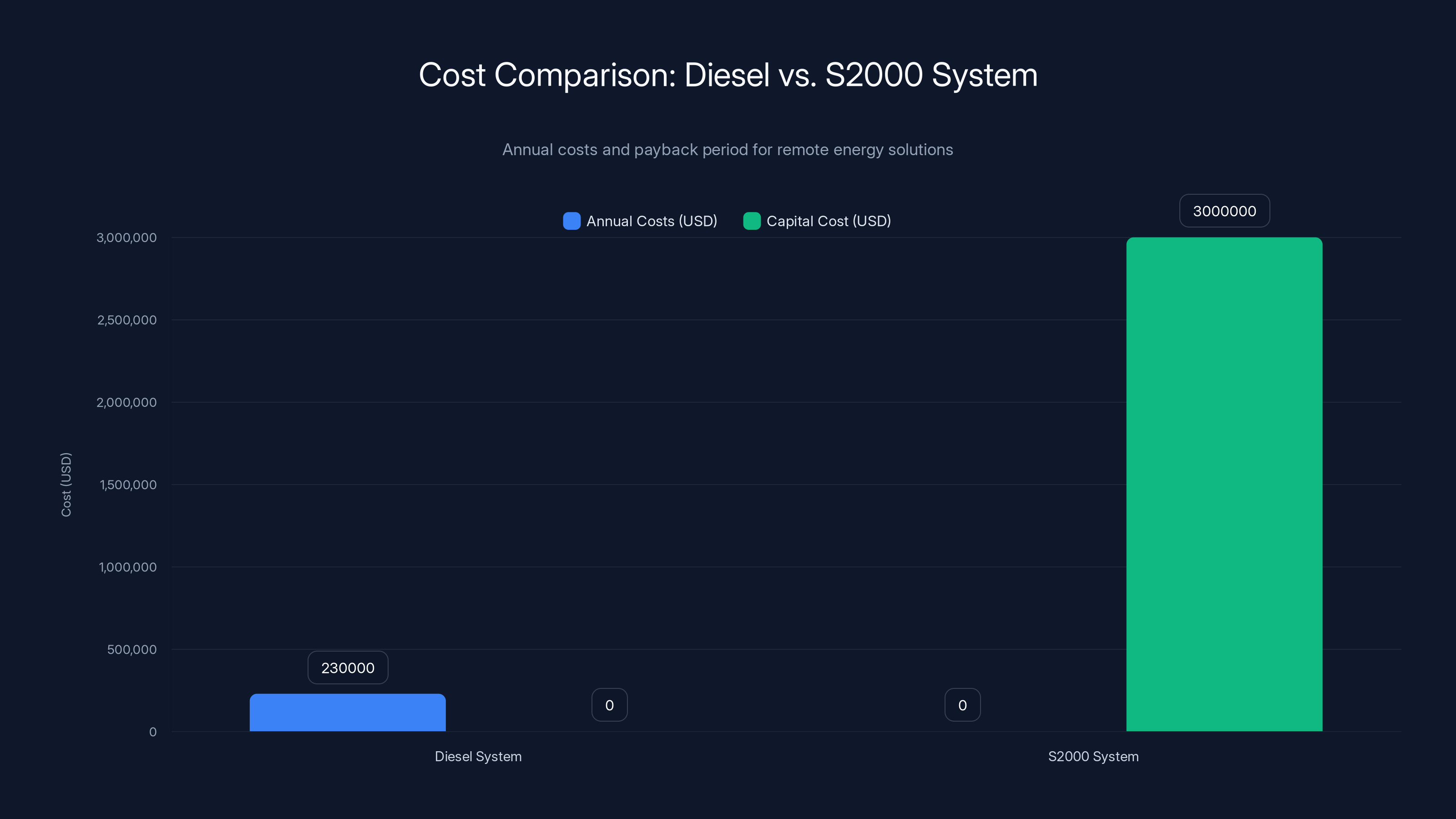

Consider the practical scenario: a border outpost 500 kilometers from the nearest grid connection currently runs on 50 kilowatts of diesel generation, consuming 40 gallons per day. That's 14,600 gallons annually. Transportation to reach the remote location costs

Replace that with an S2000 system: $3 million capital cost, zero fuel costs, silent operation, no environmental liability. Payback timeline: approximately 13 years. But the actual value calculation for a remote facility is different—you're not just saving fuel costs, you're gaining energy independence, reducing supply chain vulnerability, and eliminating operational noise that broadcasts your location (important for military applications).

Second market: Complementing traditional ground-based wind farms.

Here's where the real revolution happens. Weng Hanke described it perfectly: "The other is to complement traditional ground-based wind farms, creating a three-dimensional approach to energy supply."

Imaginative a wind farm with 40 megawatts of ground-based turbines. Wind is inconsistent. Some days it's a 5 meter-per-second breeze that generates minimal power. Other days it's 15 meter-per-second gusts that overwhelm the system. Energy production swings wildly month to month, season to season.

Now add airborne wind systems at 2 kilometers altitude where wind patterns are fundamentally different. The higher altitude captures wind from different atmospheric layers. High altitude wind might be strong while ground wind is weak, and vice versa. By combining generation from multiple altitude layers, you smooth out natural variability. Grid operators see more consistent, predictable power output. That reduces the need for expensive battery storage to balance supply and demand.

For a wind farm operator, deploying airborne systems alongside ground turbines creates:

- Improved capacity factor: The same physical location generates more power annually because you're harvesting from multiple altitude layers

- Better grid predictability: Combined generation from different sources smooths out natural fluctuations

- Reduced intermittency: Grid operators need less reserve capacity to handle generation swings

- Land efficiency: You use the same property for more total generation

Think about existing wind farms. A typical site has optimal wind resources for ground-based turbines. Deploy airborne systems on the same site, and you're not limited by turbine height, spacing requirements, or ground-level wind characteristics. Vertical space becomes harvestable.

The economic implications are staggering. A wind farm operator doesn't need to find entirely new locations. They can densify generation on existing properties. That reduces transmission infrastructure costs, permitting challenges, and environmental impacts.

Manufacturing Scale and the Envelope Problem That Almost Killed Everything

Here's a detail that separates concepts from real products: you need materials that don't exist yet at scale.

The S2000 requires enormous helium-filled envelopes constructed from specialized materials that must survive extreme stress while remaining lightweight. The envelope material—likely advanced composite fabric with protective coatings—needs to withstand:

- UV exposure from continuous high-altitude operation

- Temperature cycling as the system moves between altitude levels and ground

- Pressure differentials between internal helium and external atmosphere

- Mechanical stress from tether tension and wind forces

- Ozone attack from atmospheric exposure at high altitude

- Puncture and abrasion resistance during deployment and operation

Traditional materials like Dacron or Vectran, used in blimps and weather balloons, don't have the performance requirements. Linyi Yunchuan almost certainly developed proprietary envelope technology that represents genuine intellectual property.

The fact that they're establishing expanded manufacturing capacity in Zhejiang Province tells you something important: they've solved the materials and manufacturing problem. This isn't vapor-ware where they're hoping to figure it out someday. Production is happening. Capacity is scaling.

Zhejiang Province already hosts the world's largest balloon manufacturing industry. The ecosystem for advanced textiles, specialty coatings, and precision manufacturing is already established. That's not random location selection. It's strategic positioning within existing industrial capability.

Small batch production launching now serves multiple purposes: proving manufacturing repeatability, identifying process improvements, gathering real operational data to inform next-generation designs, and generating revenue to fund further expansion. It's the classic hardware company playbook, but executed by a team that has actually achieved a working prototype at scale.

Energy Density Calculations: Why 3 Megawatts Represents a Genuine Breakthrough

Let's talk actual power production and what it means in practical terms.

The S2000 reaches a rated capacity of 3 megawatts. During the test flight, it generated 385 kilowatt-hours, which suggests operating at significantly below rated capacity—probably 50-60% due to suboptimal wind conditions, testing protocols, or deliberate conservative operation.

But let's do the math on what 3 megawatts means when deployed at scale:

Single unit annual production calculation:

Assuming a 35% capacity factor (typical for good wind sites, conservative for airborne at altitude):

That's roughly equivalent to powering 800-900 homes annually, depending on regional consumption patterns.

Spatial efficiency comparison:

A traditional ground-based 3MW turbine requires:

- Rotor diameter: approximately 100 meters

- Ground footprint: roughly 2,000 square meters

- Minimum clearance requirement: 1 hectare (10,000 square meters) of open land with no obstacles

The S2000 requires:

- Ground installation footprint: approximately 1,000 square meters

- Aerial workspace: 2km altitude (doesn't interfere with ground use)

- Minimum clearance requirement: 500 meters radius on ground

You could deploy the S2000 on industrial sites, ports, or agricultural land where traditional turbines are prohibited. That opens locations currently considered unsuitable.

Economic scaling scenario:

Assuming

$$\text{Annual revenue} = 9,198 \text{ MWh} \times $80 = $735,840

$$\text{Simple payback} = \frac{\$15,000,000}{\$735,840} \approx 20.4 \text{ years}$$ That's not compelling on its own. But remember: the cost estimates will drop dramatically as manufacturing scales. And when you deploy units in remote locations with no alternative power source, or on existing wind farm property where grid connection already exists, economics flip dramatically. Further, that calculation doesn't account for environmental credits, grid-stability payments, or the value of avoiding fuel logistics in remote locations. <div class="quick-tip"> <strong>QUICK TIP:</strong> The most important metric isn't the absolute power output of one unit—it's the addressable market size if deployed at scale. Small improvements in cost structure transform margins from negative to highly profitable. </div>   *The S2000 offers a more compact and rapidly deployable solution compared to traditional wind turbines, with significantly reduced height and width, and a deployment time of just 30 minutes. Estimated data.* ## The Stability and Control Challenge That Previous Systems Failed To Solve Literally dozens of airborne wind companies have crashed and burned—sometimes literally, as with early kite-based systems that suffered catastrophic failures. The core problem: airborne systems are inherently unstable. They're subject to winds that change constantly in direction and magnitude. Unlike ground-based turbines that fight wind with rigid structures, airborne systems must accommodate dynamic forces through active control. Previous approaches failed because they treated this like a passive problem. Build a rigid structure, secure it with cables, and hope it survives. Reality doesn't work that way. The atmosphere is never static. Boundary layer dynamics, wind shear, turbulence, and gusts create forces that accumulate. The S2000 approach treats stability as an active problem requiring continuous management: **The helium envelope isn't just buoyant—it's a mechanical dampener.** As the platform experiences forces, the envelope's flexibility absorbs energy rather than transmitting it rigidly to the tether. This is fundamentally different from a hard-mounted turbine that transmits all forces directly to its support structure. **Tether positioning is actively controlled.** Rather than hanging straight down, the tether can be manipulated through ground-based winches and control systems. This allows the platform to position itself for optimal wind capture while managing forces. It's akin to how a person on a rope bridge can move their weight to manage swinging—the platform can position itself to manage wind loads. **The ducted turbine design provides inherent load balancing.** Twelve distributed turbines automatically adjust to wind conditions. If wind hits from one angle, some turbines capture more while others capture less, and load distributes naturally. A single massive rotor would lurch and vibrate; twelve smaller ones dampen and spread that stress. **Operational envelope limits maintain safety margins.** The system likely operates within defined wind speed ranges and atmospheric conditions. Beyond those limits, controlled descent brings the system to ground. This isn't failure—it's smart constraint management. The successful test flight demonstrated that this stability approach actually works. The platform didn't just survive; it maintained stable hover at 2 kilometers while generating power. Real-world atmospheric conditions didn't destroy it. That's the barrier previous systems couldn't clear. ## Integration With Existing Grid Infrastructure and Regulatory Pathways There's an underappreciated challenge with deploying new power generation technology: regulatory and grid integration requirements. The electrical grid has standards evolved over decades. New generation sources must meet specific requirements for safety, stability, and performance. Grid operators are cautious—rightfully so. A malfunction in the wrong place can cascade into blackouts affecting millions. Adding new generation technologies requires extensive testing and validation. The S2000's successful grid connection demonstrates that Linyi Yunchuan has navigated this regulatory landscape. They didn't just build a generator; they built something that integrated with actual grid infrastructure and passed safety validation. That suggests: **Regulatory approval pathways exist.** Chinese authorities granted permission for grid-connected operation. Other countries will follow as they develop confidence in the technology. **Technical standards are being established.** The successful test provides benchmarks that regulators can evaluate and potentially codify into standards for future deployments. **Grid operators understand the system.** Rather than abstractly contemplating a new technology, they've now operated one. Comfort grows from familiarity and successful experience. **Insurance and liability frameworks can be developed.** As systems operate successfully without incidents, underwriters become willing to provide coverage and liability protection. These factors matter more than pure engineering performance. A technology doesn't scale without regulatory acceptance and insurance availability. The S2000's successful grid connection starts both of those processes.  ## Competing Technologies and Why Airborne Wind Could Actually Win The renewable energy sector has been absolutely saturated with airborne wind projects over the past fifteen years. Most have failed or abandoned their technology focus. Why? Because the barriers were genuinely severe, and most approaches couldn't overcome them. But the S2000's success now makes you reconsider previous failures. **Makani (acquired by Google, then shut down).** Makani's approach used large artificial wings tethered to ground winches, flying in circles to generate power. The technology worked in testing but faced stability challenges at full scale and struggled with cost economics. Why did Makani fail where S2000 succeeds? Possibly because Makani relied on active wing control and aerodynamic lift generation, which creates complexity. The S2000's aerostat-based buoyancy is passive and simple by comparison. **Altaeros Energies.** Their BAT (Buoyant Airborne Turbine) concept used a helium-filled tether to lift a turbine. Promising concept, but the company ultimately pivoted away from airborne wind due to technical challenges and market economics. **Windlift and other kite concepts.** Pure kite-based approaches offered simplicity but lacked the payload capacity and control authority needed for serious power generation. What made previous attempts fail? - **Overcomplication.** Many systems tried to innovate too aggressively, solving problems that didn't need solving - **Cost structure.** Most required expensive, custom materials and manufacturing at tiny production volumes - **Regulatory uncertainty.** Operating in the aerial space created undefined liability and insurance challenges - **Insufficient power output.** Many systems generated kilowatts or low megawatts, not enough to justify investment The S2000 addressed each of these: - **Elegant simplicity.** Helium buoyancy plus ducted turbines. Both mature, proven concepts combined in a new way - **Manufacturability.** Uses advanced but not exotic materials. Can scale in existing industrial facilities - **Regulatory confidence.** Demonstrated successful grid connection, proving the system meets real electrical standards - **Meaningful power output.** 3 megawatt capacity provides real value What becomes clear is that airborne wind wasn't fundamentally impossible—previous attempts just weren't quite right. The S2000 got the formula correct. <div class="fun-fact"> <strong>DID YOU KNOW:</strong> The global renewable energy generation capacity reached 4,432 GW in 2023, with wind accounting for approximately 1,100 GW. Adding even 5% new capacity through airborne wind technology would represent an $80+ billion market opportunity. </div>  *The airborne wind energy market is projected to grow significantly, potentially reaching 15 GW capacity and $22 billion in revenue by 2035. Estimated data based on projected market trends.* ## The Geographic and Climate Expansion Possibilities Traditional wind farms face geographic constraints. You need consistent wind at reasonable speed. You need land area. You need locations where communities will accept massive structures dominating the landscape. Airborne wind systems expand possible deployment locations dramatically: **Tropical and equatorial regions.** These areas historically had lower wind resources at ground level, making traditional wind farms uneconomical. But at 2-3 kilometer altitude, consistent trade winds blow year-round. Airborne systems could bring serious wind generation to regions previously limited to solar. **Coastal and maritime applications.** The S2000 could be deployed on oil platforms, coastal industrial facilities, or specialized maritime installations. Imagine offshore drilling platforms generating their own power instead of relying on fuel logistics. Or ports using airborne wind to power cargo handling systems. **Mountain and elevated terrain.** Rather than trying to place massive turbines on mountain peaks (expensive, dangerous, environmentally challenging), airborne systems could operate in valleys and elevated areas without the infrastructure costs of ground-based turbines. **Arid and desert regions.** Places like the Sahara, Arabian Peninsula, or Australian outback have extraordinary wind resources at altitude but extremely challenging terrain for traditional infrastructure. Airborne systems could transform energy generation in these regions. **Seasonal and variable wind zones.** Regions with inconsistent ground-level wind but stronger higher-altitude winds become viable. This especially matters for monsoon regions and areas with seasonal wind patterns. China specifically benefits from this technology because large regions have excellent high-altitude wind resources but challenging terrain or population density that limits traditional turbine placement. The Tibetan plateau, Inner Mongolia steppes, and coastal regions could all benefit from distributed airborne wind generation. For global energy transition goals, expanding wind generation into previously unsuitable regions accelerates decarbonization. That's not a minor consideration—it's the difference between meeting climate targets or falling short.  ## Economics at Scale: The Cost Trajectory and Market Timeline One fundamental reality about energy technology: cost structure determines everything. A technology can be impressive, but if it costs twice as much as alternatives, it won't deploy at meaningful scale. Linyi Yunchuan's focus on manufacturing scale suggests they're confident about cost trajectory. Here's what economics might look like as production ramps: **Year 1 (2025-2026): Proof of concept production.** Manufacturing 20-50 units annually at approximately $15,000 per kilowatt. These units go to government projects, remote locations with special needs, or integrated into existing wind farms. **Year 3-4: Volume production beginning.** Manufacturing capacity reaches 500+ units annually. Per-unit costs drop to $8,000-10,000 per kilowatt as materials are sourced at scale and manufacturing processes optimize. **Year 7-10: Mature production.** Manufacturing reaches 5,000+ units annually across multiple facilities. Costs approach $4,000-5,000 per kilowatt, comparable to ground-based turbine economics. At what point does the S2000 achieve grid parity with traditional wind? Probably year 4-5 when manufacturing reaches sufficient scale and costs stabilize. That timeline aligns with how other renewable technologies evolved—solar panels took roughly 10 years to reach grid parity, lithium batteries slightly longer. Once achieved, deployment accelerates exponentially. Renewable energy companies don't need government subsidies anymore. Pure economics drive installation. Grid operators install units because they improve efficiency. Electricity costs decrease as more supply enters markets. China's strategy suggests they understand this trajectory. Rather than waiting for cost perfection before manufacturing, they're scaling production to drive cost reductions. It's the same playbook that made China dominant in solar panel manufacturing—move fast on production, improve through iteration, achieve cost advantage, export globally. ## The Competitive Response and International Development Race Without question, China's successful S2000 deployment just kicked off a global competitive response. Other countries' governments, energy companies, and venture-backed startups are now racing to develop comparable systems. **United States likely response:** American energy companies and defense contractors have already explored airborne wind. Boeing and other aerospace firms have the engineering capability. Expect $50-100 million venture funding rounds for promising American airborne wind startups. **European Union response:** Denmark's Vestas and Siemens, Europe's wind turbine giants, cannot ignore this development. Expect significant R&D investments and potential acquisitions of promising European airborne wind companies. **India and developing nations:** Energy-hungry developing economies will watch the S2000's performance and likely attempt to license or reverse-engineer the technology. India specifically has both excellent wind resources and manufacturing capability. The pattern is identical to how solar, lithium batteries, and electric vehicles evolved: China achieves a breakthrough, demonstrates commercialization is possible, then the world mobilizes to catch up. Linyi Yunchuan's first-mover advantage is substantial, but probably temporary. Within 5-7 years, expect competing systems from other manufacturers. Technology will improve, costs will drop, deployment will accelerate. The question becomes: can China maintain competitive advantage through continuous innovation and manufacturing excellence? Or will other nations catch up and compete purely on cost? History suggests both happen simultaneously. <div class="quick-tip"> <strong>QUICK TIP:</strong> If you're evaluating renewable energy investments, airborne wind technology just moved from speculative to investable. The S2000 changed the risk profile fundamentally by proving real grid connection is possible. </div>   *The S2000 system eliminates annual fuel and logistics costs of $230,000 associated with diesel generators, with a capital cost of $3 million and a payback period of approximately 13 years. Estimated data.* ## Environmental and Social Considerations: The Underappreciated Aspects Whenever you introduce new energy technology, environmental and social impacts deserve serious consideration. Here's where airborne wind actually offers advantages over alternatives: **Bird and bat impact mitigation.** This is huge. Traditional wind turbines kill significant numbers of birds and bats annually, which creates regulatory challenges and environmental opposition. Airborne wind systems operating at 2+ kilometers altitude avoid the altitude band where most birds and bats navigate. This could significantly reduce wildlife impact—though real-world testing will be needed to confirm. **Visual impact reduction.** Giant wind turbines dominating skylines creates opposition in many communities. Airborne systems visible as distant airships in the sky represent fundamentally different visual impact. Some might argue the sky isn't less visible than blades on the horizon, but the psychology differs. **Land use compatibility.** Because airborne systems don't require massive ground footprints, they can integrate with agricultural land, industrial sites, or urban areas. No need to exclude farming beneath the platform or restrict ground use. The same property generates energy and agricultural output simultaneously. **Manufacturing and supply chain impacts.** Airborne systems require advanced materials and precision manufacturing, but the manufacturing footprint is smaller than traditional turbine blade production. Materials are more standardized. Supply chains are potentially more concentrated and controllable. **Noise generation.** Airborne systems operating 2 kilometers altitude are fundamentally quieter than ground-based turbines. Sound traveling upward from turbines doesn't directly impact nearby communities. This matters for public acceptance, especially in populated areas. **End-of-life recycling.** This one cuts both ways. Helium envelopes and tether materials need to be recycled or disposed of responsibly. But the quantity of materials per unit energy is likely lower than massive traditional turbines. More research is needed here. The environmental advantage isn't automatic—it requires responsible implementation. But the potential exists for airborne wind to address some legitimately challenging environmental issues traditional turbines create. ## Future Development Pathways: What Comes Next If the S2000 succeeds at meaningful scale, what evolution follows? **Higher altitude operation.** Once 2-kilometer systems become routine, engineering effort shifts to 3-4 kilometer altitude where wind is even stronger and more consistent. Jet stream energy becomes harvestable. **Scaling to larger capacity.** 3MW might not be the optimum size. 5MW, 10MW, or larger units might prove more economically efficient, requiring proportional scaling of all systems. **Autonomous operation.** Current systems likely require active ground-based control. Future systems could operate more autonomously, using onboard sensors and control systems to manage positioning and power output. **Distributed swarm operation.** Rather than single large systems, imagine multiple smaller airborne units working in coordination, adapting to changing wind patterns collectively. This adds complexity but provides redundancy and flexibility. **Hybrid systems.** Combining airborne wind with solar, hydroelectric, or battery storage at the same location creates comprehensive energy generation systems that can operate 24/7 regardless of weather. **Aerial wind farms.** Imagine hundreds or thousands of airborne wind systems deployed across regions, collectively generating gigawatts of power. Grid integration becomes more complex, but the potential is extraordinary. **Mobile and emergency deployment.** Systems designed for rapid deployment to disaster areas, temporary construction sites, or emergency power situations where traditional infrastructure is unavailable. Each of these pathways would take 10-15 years to develop and deploy. The Linyi Yunchuan S2000 represents year one of this evolution.  ## The Regulatory and Insurance Landscape Still Being Established Technology isn't enough. You need regulations, insurance, and standardized procedures before systems can deploy at scale. Currently, airborne wind systems exist in regulatory gray zones. They're not aircraft (thus not subject to aviation regulations). They're not traditional power generation (thus not fully subject to electrical regulations). They're semi-autonomous, tethered systems operating in airspace—a category that didn't exist before. Success of the S2000 forces regulators worldwide to develop clear pathways. This likely includes: **Airspace coordination requirements.** How do you notify aviation authorities? How do you keep the systems away from flight corridors? What altitude buffers are required? These questions need formal answers. **Electromagnetic interference standards.** The high-power tether and electrical systems could potentially interfere with communication or navigation systems. Standards for testing and mitigation are being developed. **Structural and material testing.** Manufacturing must meet defined standards for envelope material, tether strength, electrical safety, and so forth. International standards organizations (like IEC and ISO) will likely develop specifications. **Operational licensing and personnel certification.** Who operates these systems? What training and certification do operators need? These requirements will be formalized. **Insurance and liability frameworks.** What happens if a system fails catastrophically? Insurance markets need clarity on liability limits, coverage types, and risk assessment methodologies. **Environmental assessment protocols.** Wind farms require environmental review. Airborne systems will too, but the framework needs to address their unique characteristics (bird impact, weather modification potential, etc.). Regulatory development takes years, but successful initial deployments accelerate the process. The S2000 test flight just triggered this regulatory evolution globally. ## Real-World Deployment Challenges You Never Hear About Let's talk about problems that don't make headlines but absolutely matter for real-world deployment: **Weather-based operational downtime.** Systems can't operate in thunderstorms, extreme winds, or certain other conditions. What's the actual percentage of operational uptime in different regions? Real performance data will determine viability. **Tether maintenance and degradation.** Tethers experience stress cycling, UV exposure, and mechanical wear. How often do they need replacement? What's the maintenance cost per year? This determines total cost of ownership. **Helium supply and cost.** Helium is finite. Global helium supply is already constrained. If airborne wind scales massively, helium cost could become limiting. Research into alternative lifting gasses (or hybrid buoyancy systems) is essential. **Salt spray and corrosion in maritime deployments.** Coastal locations have excellent wind resources, but salt spray corrodes materials. How do systems resist this degradation? **Electromagnetic compatibility in urban deployments.** Dense electrical transmission in urban areas could create interference issues. How does the system perform in electromagnetically complex environments? **Cold climate operation.** Ice buildup on envelopes and tethers could impair systems. How do systems function in arctic or high-altitude cold environments? **Extreme wind survival.** What happens when unexpected extreme winds arrive? How robust are systems to worst-case conditions? These aren't showstoppers—they're engineering problems with solutions. But they require actual operational experience to address properly. The S2000 will accumulate that experience, and manufacturers will improve systems based on findings.  ## Investment and Market Growth Projections Let's attempt to quantify the market opportunity. Global renewable energy capacity additions are currently approximately 300+ GW annually. Of that, approximately 80 GW is wind. Growth projections suggest 150+ GW annually by 2030 as countries accelerate decarbonization. If airborne wind captures even 2-5% of that growth by 2030, that's 3-7.5 GW annually, or roughly 30-75 units at 3MW capacity each. At $15,000 per kilowatt, that's $1.35-3.4 billion in annual revenue by 2030 for the sector. By 2035, if airborne wind reaches 10% of new wind capacity, global deployment could reach 15 GW annually, or 5,000+ units. That's a $22+ billion annual market. These numbers assume successful cost reduction, regulatory approval, and market acceptance. They're not guaranteed. But they're plausible based on technology maturity and global energy needs. For investors, the window for positioning in this market is currently open but closing. First-movers and well-positioned competitors will accumulate disproportionate advantage. By the time the technology is obviously going to succeed, premium valuations will reflect that certainty. --- ## FAQ ### What exactly is the S2000 airborne wind turbine? The S2000, or Stratosphere Airborne Wind Energy System (SAWES), is a helium-filled tethered platform developed by Chinese company Linyi Yunchuan Energy Technology that generates electricity at high altitude. It rises to approximately 2 kilometers where wind is stronger and more consistent than at ground level, using 12 ducted turbines to capture wind energy and transmit power to the ground through a tether cable. ### How does the S2000 generate and transmit electricity? The system uses 12 smaller turbines arranged in a duct around the platform's envelope. As wind flows through the annular duct structure, turbines rotate and generate electricity. Power is transmitted down the tether to ground-based infrastructure that connects to the electrical grid or local systems. The tether also provides structural support and positioning control for the airborne platform. ### What makes the S2000 different from traditional wind turbines? Traditional wind turbines operate at ground level where wind is inconsistent and turbulent due to terrain and obstacles. The S2000 operates at 2 kilometers altitude where wind is stronger and more stable, potentially generating 3-8 times more power than equivalent ground-based systems. Its compact footprint and lack of massive ground infrastructure make it suitable for urban, remote, and maritime deployment where traditional turbines are impractical. ### What are the main benefits of airborne wind energy? Benefits include access to stronger and more consistent wind resources at altitude, reduced land use requirements since the aerial footprint doesn't interfere with ground use, lower environmental impact from bird and bat interaction, quieter operation due to distance from residential areas, faster deployment without extensive infrastructure, and suitability for locations unsuitable for traditional turbines such as remote regions and coastal areas. ### What is the power output and capacity of the S2000? The S2000 has a rated capacity of up to 3 megawatts. During its maiden test flight in January 2026, it generated 385 kilowatt-hours of electricity during approximately 30 minutes of ascent and stabilized operation. At full operational capacity and assuming a 35% capacity factor typical for good wind sites, a single unit would generate approximately 9,200 megawatt-hours annually, enough to power roughly 800-900 homes. ### Where can airborne wind systems be deployed? Airborne wind systems can operate in diverse geographic locations including tropical and equatorial regions with consistent trade winds, coastal and maritime areas, mountainous terrain where ground-based turbines are impractical, desert regions with strong high-altitude winds, and urban industrial areas where traditional turbines face zoning restrictions. They're especially valuable in remote locations where fuel logistics for diesel generation is expensive and challenging. ### How does the cost of airborne wind compare to traditional wind and solar? Current S2000 systems cost approximately $15,000 per kilowatt installed, or about $45 million per unit. As manufacturing scales, costs are projected to decline to $4,000-5,000 per kilowatt within 7-10 years, achieving cost competitiveness with traditional wind. Initial payback timelines are 15-20 years, which becomes attractive as costs decline and electricity prices increase. ### What regulatory approvals does airborne wind require? Airborne wind systems must comply with airspace regulations, electrical grid connection standards, structural and material specifications, electromagnetic compatibility requirements, and environmental assessment protocols. China's successful S2000 grid connection demonstrates regulatory pathways exist, but international standards are still being developed through organizations like the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ### Can airborne wind systems operate in extreme weather? Systems can operate in normal wind conditions but must shut down and descend during thunderstorms, extreme wind gusts exceeding safe limits, or other severe weather. Typical operational uptime is determined by regional weather patterns. Systems are designed to safely de-energize and descend in emergencies, with tether strength and platform stability engineered for worst-case scenarios within operational parameters. ### What is the timeline for large-scale deployment of airborne wind? Small batch manufacturing is beginning in 2025-2026. Meaningful commercial deployment at scale is likely 2027-2030 as costs decline and regulatory frameworks solidify. Global airborne wind capacity could reach 5-10 GW by 2035 if technology matures as expected. Full integration into mainstream renewable energy infrastructure would require another 5-10 years beyond that point. ---  ## The Path Forward: Why This Matters Beyond the Technology The S2000 test flight might seem like one company testing one new technology in a remote region of China. But it represents something more fundamental: proof that the renewable energy transition isn't constrained by technology limitations anymore. For decades, energy policy debates centered on "when will renewable technology be ready." The S2000 answers that question: it's ready. Wind energy has matured enough that we can harvest it from places previously considered impossible. Solar costs have dropped so dramatically they're cheaper than fossil fuels in almost every market. Battery storage exists and is improving. Hydroelectric, geothermal, and other alternatives fill in gaps. The transition isn't happening because technology is impossible. It's happening at the speed it's happening because policy, economics, manufacturing infrastructure, and international coordination are harder than engineering. Airborne wind systems could accelerate that transition by opening energy generation in locations currently closed to renewable development. That means faster decarbonization. That means lower electricity costs globally. That means energy independence for regions currently dependent on fuel imports. Linyi Yunchuan's team achieved something genuine: they built something that works, they proved it operates at scale, they connected it to real electrical infrastructure, and they're moving into production. That's no longer a speculative technology. It's infrastructure in development. What happens next will be determined by whether the world's governments, energy companies, and innovators recognize this moment and mobilize resources to accelerate deployment, or whether they treat it as interesting but wait for others to solve remaining challenges. Based on history, expect both. Some regions will accelerate adoption immediately. Others will move cautiously. But the technology's future is now set: it works, it's viable, and it's only going to improve. --- ## Key Takeaways - S2000 completed first megawatt-class grid-connected airborne wind test, generating 385kWh at 2km altitude—proving technology viability at scale - Ducted turbine design with 12 smaller turbines captures wind from all angles, achieving 3-8x power output versus ground-based systems in equivalent locations - Compact 197ft x 131ft footprint enables urban and remote deployment where traditional turbines face zoning restrictions or infrastructure constraints - Small batch production underway with manufacturing expansion planned in Zhejiang Province, indicating transition from prototype to commercial production phase - Global market opportunity projected at $1.35-3.4 billion annually by 2030 if airborne wind captures 2-5% of new wind capacity additions ## Related Articles - <a href="https://tryrunable.com/posts/nuclear-startups-and-small-modular-reactors-can-manufacturin" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Nuclear Startups and Small Modular Reactors: Can Manufacturing Really Fix the Problem? [2025]</a> - <a href="https://tryrunable.com/posts/meta-s-nuclear-bet-with-oklo-why-tech-giants-are-fueling-the" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Meta's Nuclear Bet With Oklo: Why Tech Giants Are Fueling the Energy Revolution [2025]</a>

![China's Megawatt Airborne Wind Turbine: The S2000 Revolution [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/china-s-megawatt-airborne-wind-turbine-the-s2000-revolution-/image-1-1768671419723.jpg)