How to Survive Cold and Flu Season: Complete Prevention & Treatment Guide

It's late October. Someone in your office coughs. Then another. You immediately think: here we go again.

Cold and flu season doesn't have to feel inevitable. Yeah, you might still catch something—the odds aren't zero. But here's what actually matters: you can dramatically reduce your risk, and if you do get sick, you can minimize how bad it gets.

The gap between "resigned to getting sick" and "actually protected" is surprisingly small. It's not about obsessive hand sanitizing or becoming a hermit. It's about understanding what actually works, what's been overhyped, and what's pure theater.

I've spent weeks digging into what respiratory specialists, infectious disease doctors, epidemiologists, and public health officials recommend. Not the viral Tik Tok tips. Not the wellness influencer nonsense. The actual science-backed approaches that move the needle.

Here's what you need to know to make it through the season without losing your mind—or your health.

TL; DR

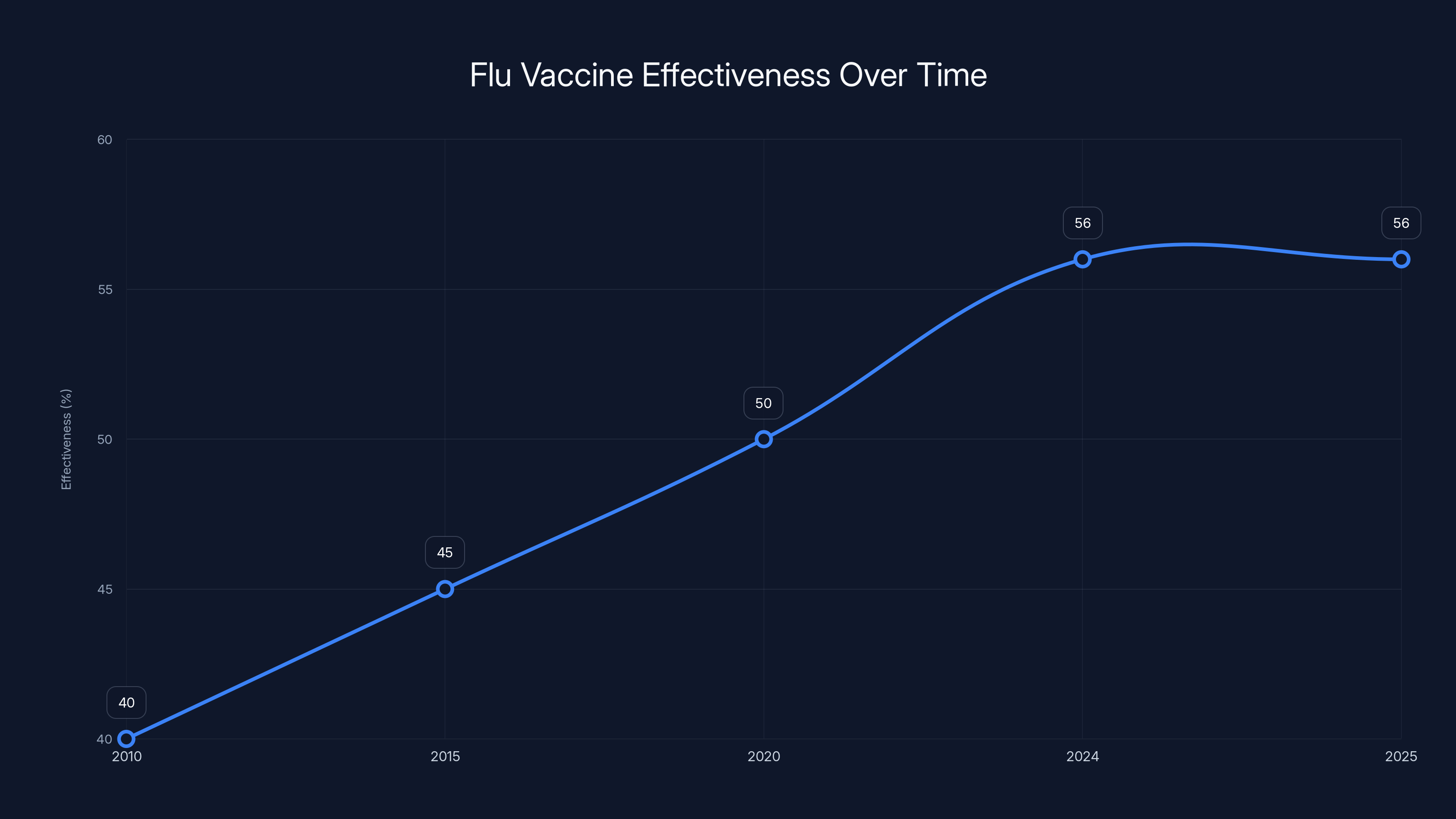

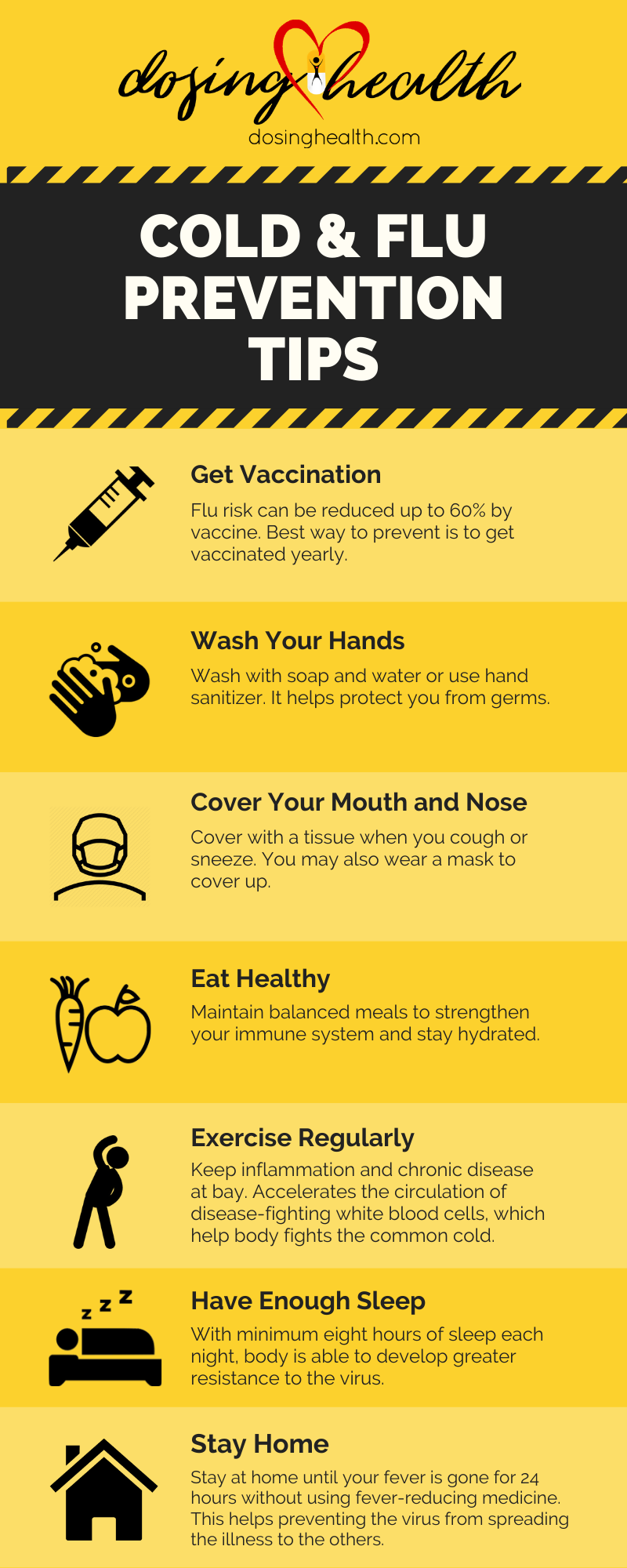

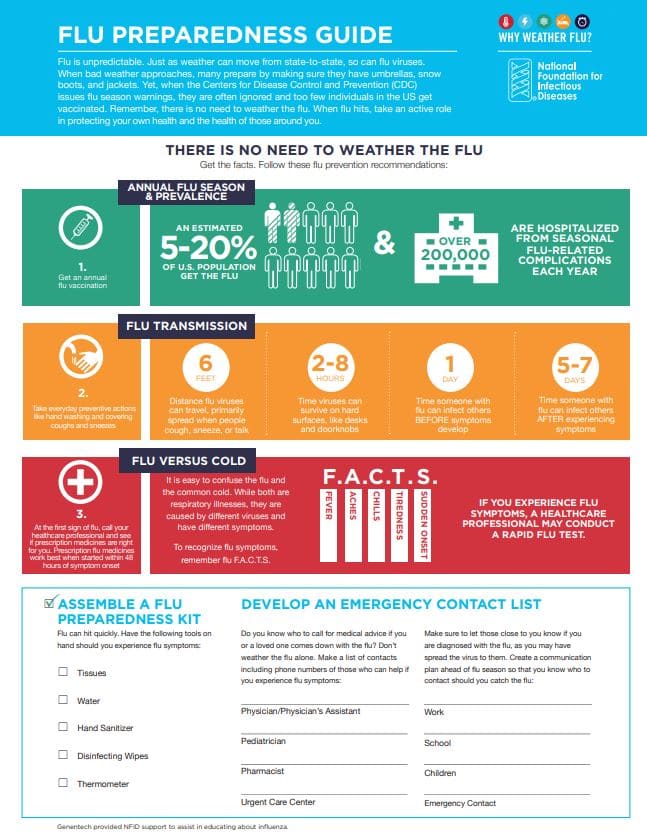

- Get vaccinated by September or October: The flu vaccine is 56% effective at preventing severe illness, and it's your single best defense against hospitalization.

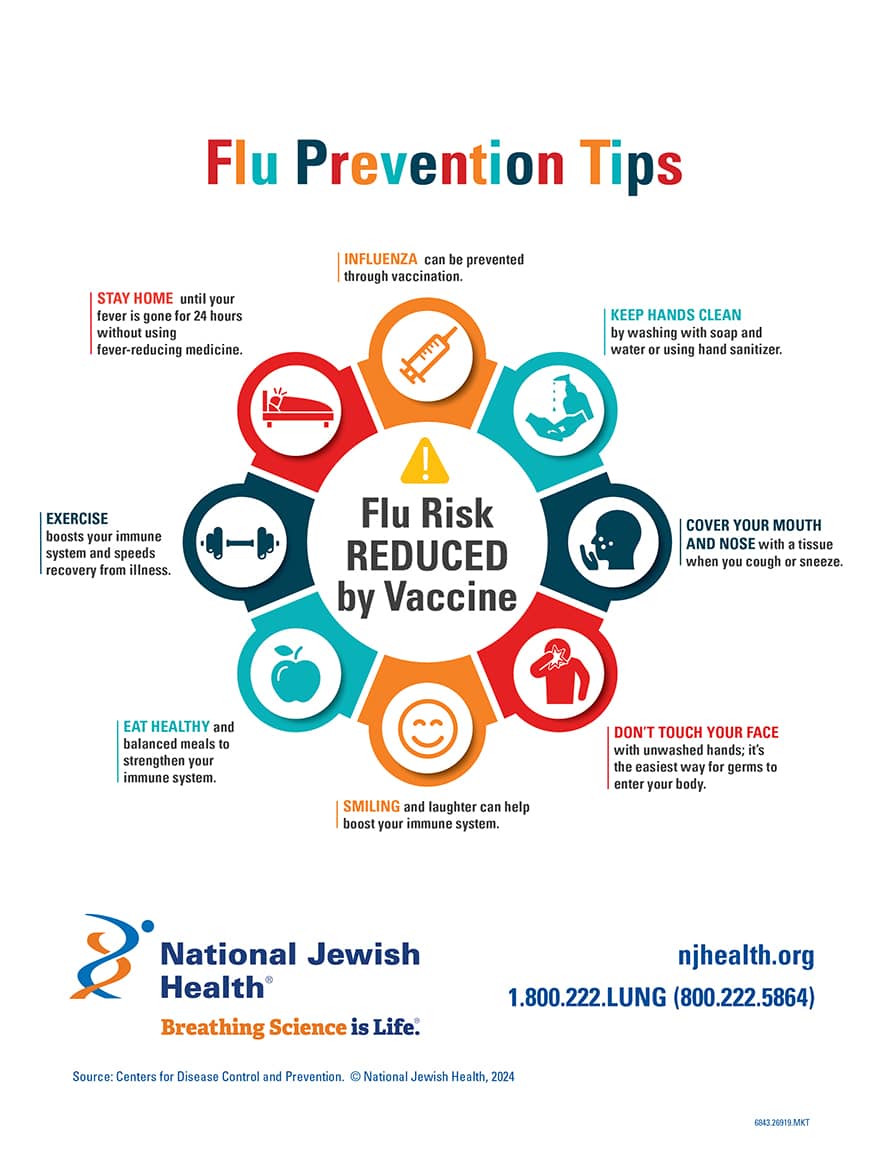

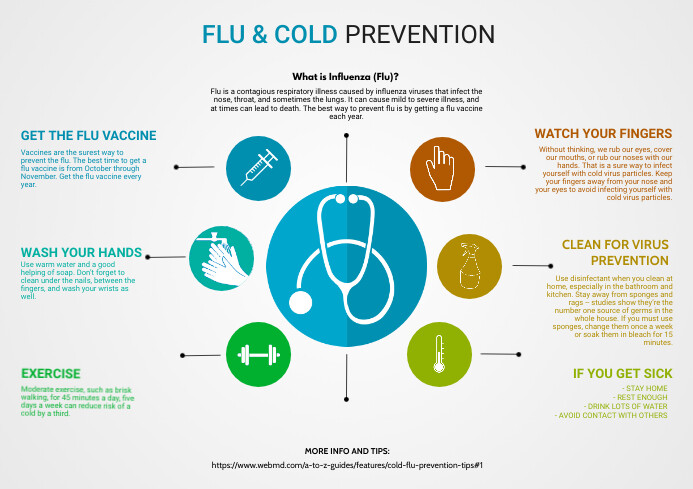

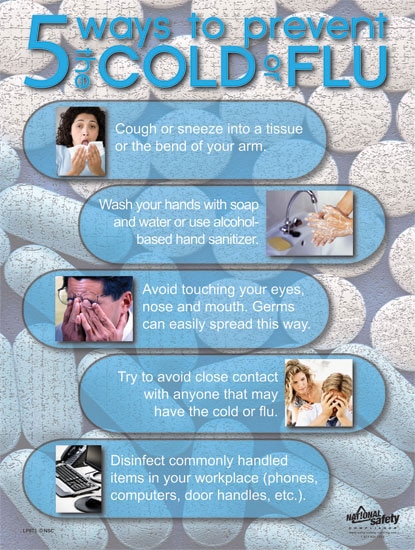

- Wash your hands, avoid crowds, and stay home when sick: These boring tactics actually work and directly reduce community spread.

- Don't touch your face: Your eyes, nose, and mouth are the main entry points for viruses that cause colds and flu.

- Ventilation matters more than air purifiers: Open a window when someone's sick, improve air circulation; most air purifiers lack real-world evidence.

- Timing is critical: Peak flu activity happens January through February, so vaccination effectiveness peaks right when you need it most.

Opening windows is the most effective method for reducing airborne virus concentration, followed by HVAC systems. Air purifiers and HEPA filters are less effective for immediate virus reduction. Estimated data based on expert opinions.

The Flu Vaccine Is Your Most Powerful Weapon

Let's start with the single most effective tool you have: the flu vaccine.

I know. You've heard it before. But here's why it keeps coming up: it actually works, and not in a marginal, barely-worth-it way. We're talking about reducing your risk of hospitalization by roughly half, which is enormous when you understand what respiratory illness actually looks like for vulnerable populations.

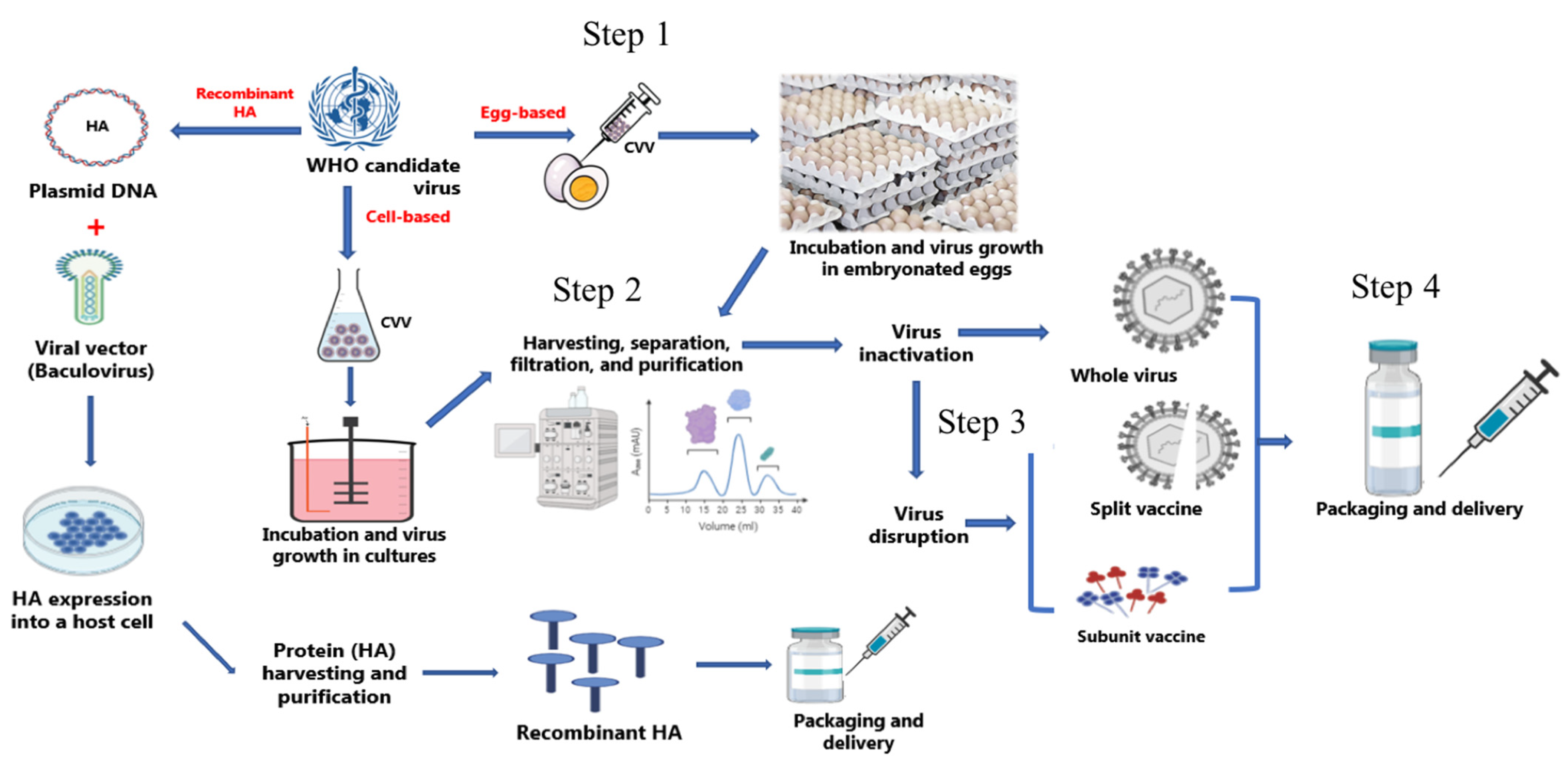

The flu vaccine changes every single year. Scientists monitor which virus strains they expect to circulate, then formulate vaccines accordingly. It's like trying to hit a moving target, except the target is constantly mutating, and you only get one shot per year.

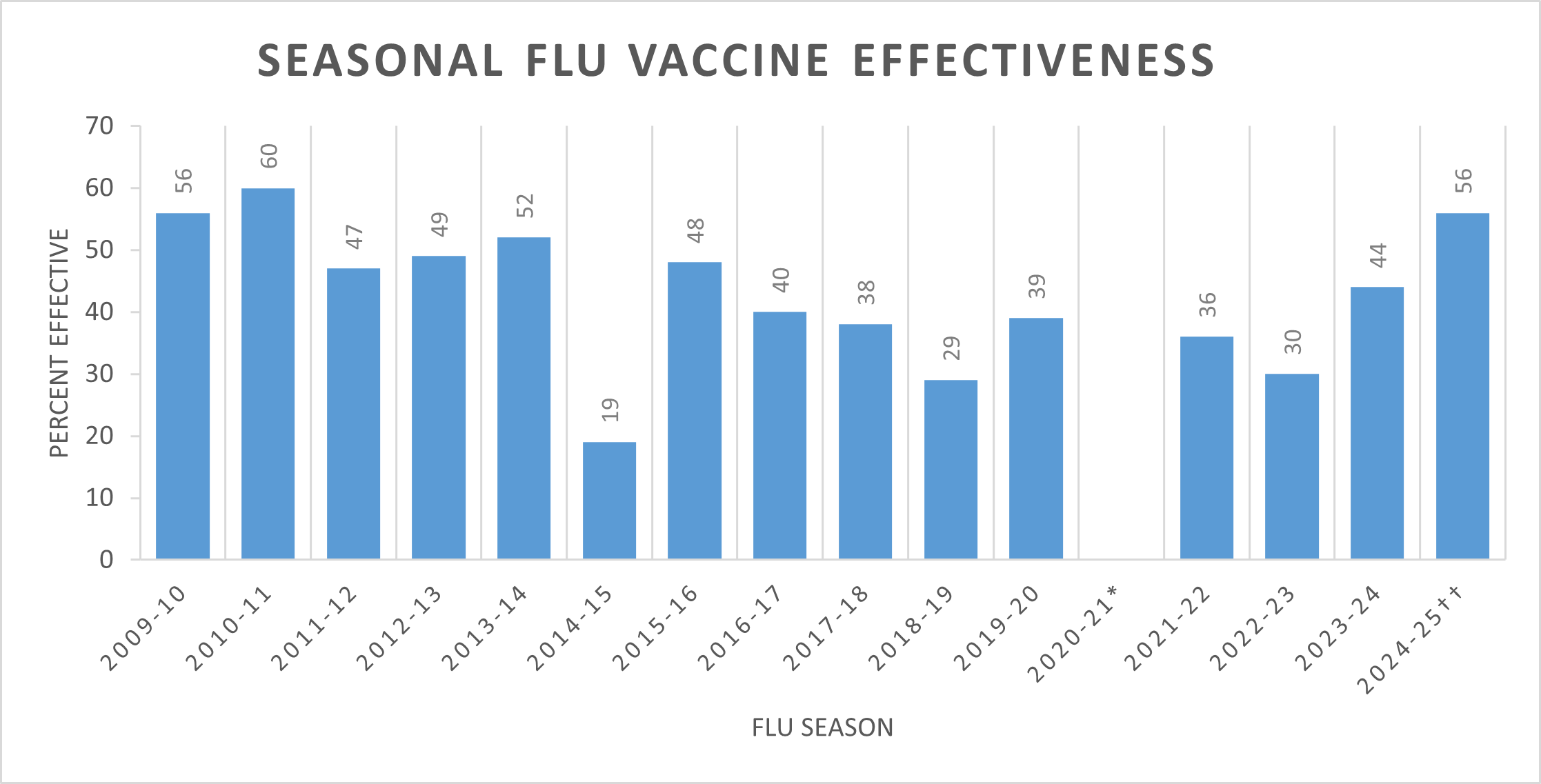

Does that mean the vaccine is perfect? No. But in the 2024-2025 season, flu vaccines hit 56% effectiveness. That's higher than it's been in nearly 15 years. Fifty-six percent means vaccinated people had roughly half the risk of needing medical care for flu compared to unvaccinated people. That's not a rounding error.

Here's the thing that catches people off guard: vaccine effectiveness and vaccine efficacy are different measurements. Efficacy is measured in controlled trials with ideal conditions. Effectiveness is measured in the real, messy world where you're sitting next to someone coughing on the bus and your immune system is weakened from sleep deprivation.

Effectiveness is what actually matters to you.

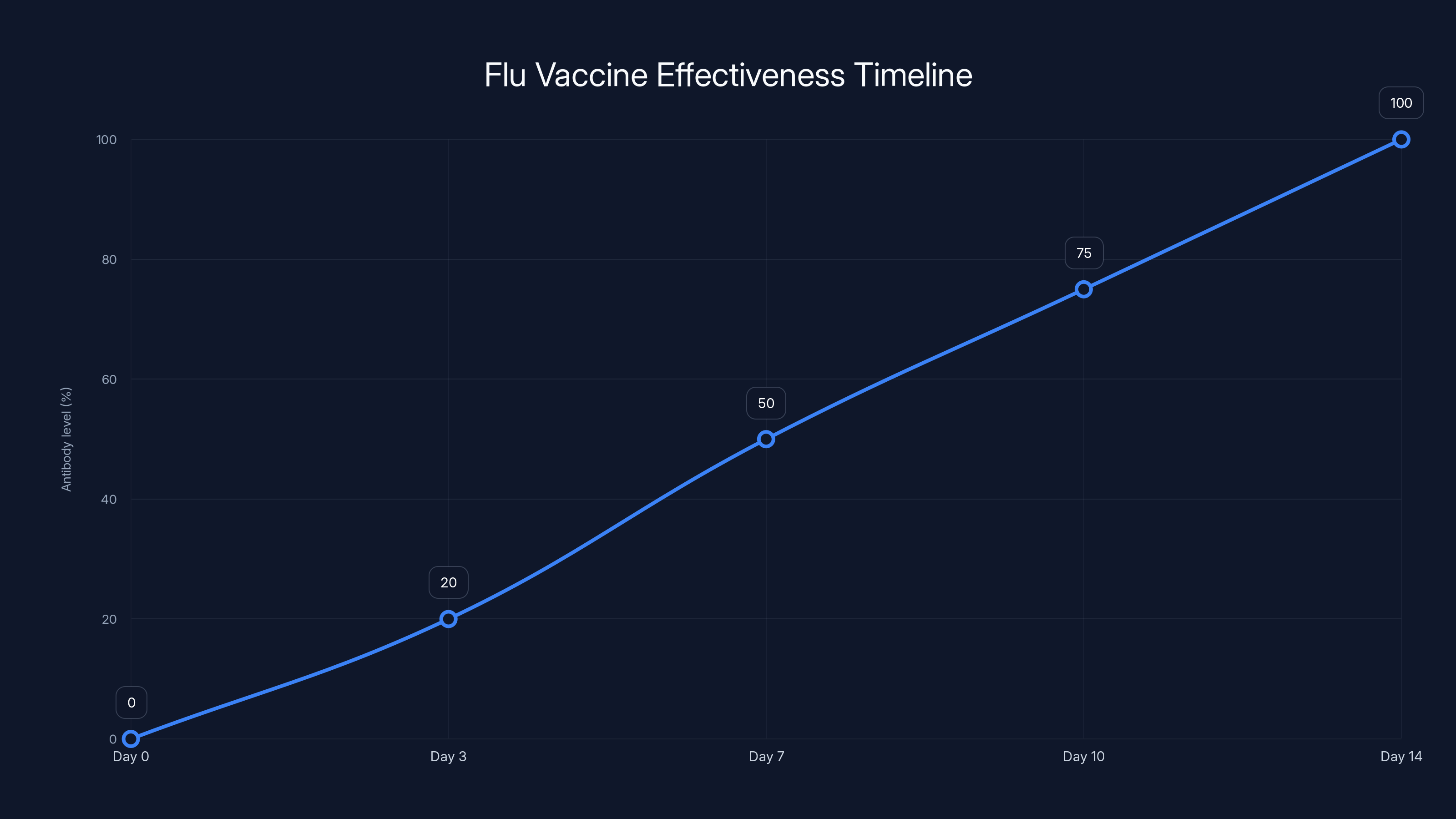

One more thing that matters: it takes up to two weeks for the vaccine to reach full effectiveness. That's not a flaw in the vaccine. That's your immune system building a defense. If you get exposed to the flu in those two weeks, you could still get sick—but it's not because the vaccine failed or gave you the flu. It's because you got infected before your immune system finished its work.

This is crucial because it changes your vaccination strategy. If you wait until December to get vaccinated, you're cutting your protection window short. Peak flu activity typically happens in January and February. Vaccinate early so you're fully protected when the virus is actively circulating.

Antibody levels gradually increase after vaccination, reaching full effectiveness around day 14. Estimated data.

Why You Can't Catch the Flu From a Flu Shot

This one deserves its own section because it's still the #1 reason people give for not getting vaccinated, and it's completely backwards.

"I can't get the flu shot. It'll give me the flu."

No. It won't. And here's why.

Flu shots contain either inactivated (killed) viruses or just a single protein from the flu virus. Dead viruses can't infect you. Proteins can't replicate. You cannot get the flu from a flu shot, period. It's physically impossible.

Now, the nasal spray flu vaccine? That's a different story technically, but practically it doesn't matter. The nasal spray contains live viruses, but they're attenuated, meaning they're weakened to the point where they won't cause illness in healthy people ages 2 to 49.

So why do some people feel sick after getting vaccinated?

Two reasons. First, your immune system is literally being trained to recognize and fight a threat. That training process sometimes feels like the flu (mild fever, body aches, fatigue) but it's not actually the flu. It's your immune system saying, "Got it. I'll remember this."

Second, timing is brutal. If you got exposed to the actual flu virus the day before your vaccine, you'd start feeling sick a few days later. Your brain might connect the two events, but the vaccine didn't cause it. You were already infected.

This distinction matters because it should reduce one major barrier to getting vaccinated. You're not trading short-term illness for long-term protection. You're getting trained by your immune system with minimal side effects, and then you're protected.

The worst feeling after a vaccination is usually mild soreness at the injection site or maybe a low-grade fever that passes in 24 hours. Compare that to actual flu, which means you're out of commission for a week or more, running a high fever, dealing with severe muscle aches, and possibly ending up hospitalized if you're over 65 or immunocompromised.

I'll take arm soreness over that trade every time.

Hand Washing Actually Works (When You Do It Right)

This feels obvious. Too obvious. Which is probably why so many people do it wrong.

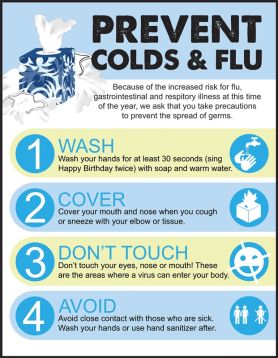

Washing your hands regularly with soap and water reduces respiratory illness transmission. That's not a maybe. That's established across multiple studies and public health data. But there's a technique component that actually matters.

First, the duration: 20 seconds minimum. That's the time it takes soap to break down the lipid (fat) layer of virus particles and cellular debris. Less time and you're just moving germs around. More than 20 seconds is fine—you're not going to hurt yourself.

Second, the soap type matters less than you'd think. Regular soap is fine. Antibacterial soap doesn't provide additional benefit for viruses. Fancy soap with essential oils? Same effectiveness as drugstore generic. What matters is the mechanical action of scrubbing combined with soap's ability to break down viral membranes.

Third, the timing. You wash your hands after using the bathroom (obvious), before eating (so you don't ingest viruses), after touching public surfaces, and especially after being around sick people. This is where most people fail. They touch their face at a coffee shop, then wonder why they got sick two days later.

Here's the real problem, though: you can't wash your hands constantly. You have a life. You have work, family obligations, and responsibilities that don't pause for hand hygiene. So the absolute best move? Stop touching your face.

Your eyes, nose, and mouth are the primary entry points for respiratory viruses. They have receptors that viruses recognize and attack. Your hands, constantly touching contaminated surfaces, become delivery mechanisms. You touch a doorknob at work, then absent-mindedly rub your eye, and congratulations: you've just inoculated yourself.

One more detail: alcohol-based hand sanitizer works in a pinch, but it's not a replacement for soap and water. Sanitizer kills germs faster (important when you're stuck in a meeting), but it doesn't remove physical debris and organic material. Soap + water is always the gold standard when available.

The flu vaccine's effectiveness reached 56% in the 2024-2025 season, the highest in nearly 15 years. Estimated data.

Avoid Sick People (Yes, Really)

This is where the tension between being a normal human and protecting yourself gets real.

You can't avoid sick people 100% of the time without becoming a hermit. That's not practical, and honestly, it's not necessary. But you can be strategic about it.

The core principle: if someone is actively shedding virus—coughing, sneezing, running a fever—they're most contagious during that period. Your risk of infection scales with proximity and duration of exposure.

So what's actionable?

In your personal life: Encourage people to stay home when sick. Be the person who says, "Don't come to my dinner party if you're sick." Make it social cover—don't come because you're contagious, not because you're being rude. Then actually do the same. If you're sick, stay home. This directly reduces virus circulation in your community, which lowers everyone's risk, including yours.

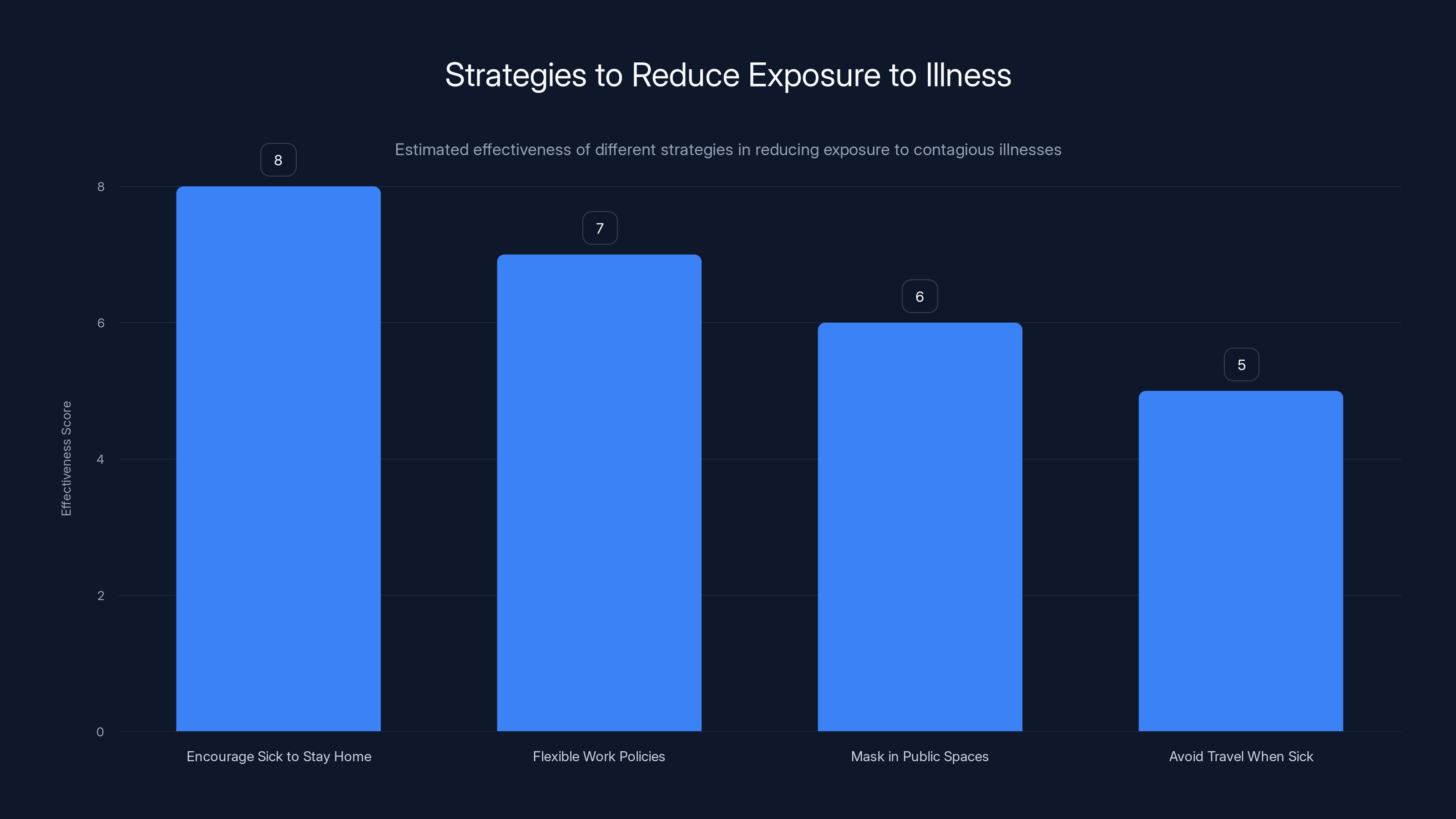

At work: This is harder because of productivity culture and the bizarre norm that appearing sick proves you're dedicated. Push back on this. Talk to your manager about flexible work policies. If you or a colleague are sick, working from home is a viable option for many jobs. Normalize it.

In public spaces: You can't realistically avoid all public spaces. But you can wear a mask in high-transmission environments (crowded transit, hospital waiting rooms, during peak flu season indoors). This is where having a mask in your pocket or bag matters. You don't need to wear it everywhere. You need it available for specific, high-risk situations.

Travel considerations: Airplanes are vectors for respiratory illness. You're breathing recycled air with hundreds of people in close quarters for hours. If you're traveling during peak flu season and you're high-risk, consider masks. If you're sick, postpone travel if possible. I know that's not always possible, but it's worth considering.

Here's the core insight: you're not trying to achieve perfect isolation. You're trying to reduce your baseline risk. Small reductions in exposure add up.

Stay Home When You're Sick (For Real This Time)

Okay, so the flip side of "avoid sick people" is "be a good human and don't expose others."

I know. You have deadlines. Your team needs you. Your kids' soccer game is important. I get it. But here's the thing: going out while contagious doesn't make you dedicated. It makes you a vector for disease transmission.

When you stay home sick, you're not just avoiding infecting others. You're directly reducing virus circulation in your community. Less virus circulating means fewer people get sick overall, which includes people you care about.

This is epidemiology 101: reducing transmission at the individual level creates population-level benefits.

The practical question: how long should you stay home?

For flu, most people are contagious for about 5-7 days from symptom onset. For the common cold, it's usually 2-3 days of peak contagiousness but can extend longer. A general rule: stay home until you've been fever-free for at least 24 hours without medication. That means no fever reducers masking a fever. An actual, genuine fever-free period.

This is harder with colds because they're usually mild and people feel okay after a few days. You can technically go to work. But you're still shedding virus. You're still contagious.

What about work from home when sick? That depends on your job and how sick you are. If you have a desk job and you're functional, working from home is reasonable. You're not spreading virus to your colleagues, and you're still productive. If your job requires in-person work and you're contagious, staying completely home is the move.

One detail that matters for workplaces: the policy around this should come from leadership. If your boss creates an environment where sick people feel pressured to come in, that's a leadership failure. Organizations that actually care about employee health and community health normalize remote work for sick employees and don't penalize it.

Encouraging sick individuals to stay home is the most effective strategy to reduce exposure, followed by flexible work policies and wearing masks in high-risk public spaces. Estimated data.

The Cough-Into-Your-Elbow Rule (and Why It Matters)

This one seems almost quaint in 2025, but it's legit science.

When you cough or sneeze, you're expelling respiratory droplets that travel several feet. These droplets contain virus particles. If they land on your hands, you then touch surfaces and transmit virus to anyone who touches that surface later. It's a multi-step process, but it works.

Coughing into your elbow breaks that chain.

Your inner elbow doesn't touch surfaces the way your hands do. You're not shaking hands, touching your face, or grabbing shared items. The virus stays on your arm where it's less likely to spread to others.

Is it perfect? No. In ideal conditions, some droplets still escape. But it's significantly better than coughing into your hands or, worse, not covering anything.

The mechanics: when you cough into your hand, virus lands on your palm and fingers. You then touch a door handle, your keyboard, your face, someone's shoulder. Each touch spreads virus. When you cough into your elbow, those particles land on an area of your body that rarely touches anything. End of transmission chain.

This is behavioral change that's low-cost and high-impact. It requires no special equipment. It's just a different habit.

One more detail: if you have tissues available, using them and immediately throwing them away is even better. Tissue into trash. Hand sanitizer. Done. You've contained the virus. But realistically, tissues aren't always available. Your elbow is always available.

Clean Surfaces (Especially High-Touch Items)

Viruses don't live forever on surfaces. But they live long enough to infect you if you touch the surface and then touch your face.

When someone in your household is sick, cleaning high-touch surfaces is worth doing. We're not talking about obsessively sterilizing everything. We're talking about the items that get touched repeatedly.

The top offenders:

- Doorknobs and light switches: Touched constantly, by everyone

- Phone screens: You touch them, then touch your face

- Keyboards and mice: If you're sharing computers, these are transmission highways

- Remote controls: Used by multiple people, rarely cleaned

- Car touchpoints: Steering wheel, gear shift, door handles

- Bathroom fixtures: Faucet handles, toilet handles

- Common tables and desks: If it gets touched, it matters

The cleaning part is straightforward: disinfecting wipes for most surfaces, appropriate cleaner for screens (don't destroy your electronics), appropriate cleaner for different materials.

The frequency depends on active illness in the household. During the sick period, wiping down high-touch surfaces daily makes sense. Once someone recovers, you can dial it back.

Here's what actually matters: if you're doing this, do it right. Don't just wipe and move on. Let the cleaner sit for the contact time specified on the bottle. That's the time needed for the disinfectant to actually kill viruses. A two-second wipe feels productive but might not be effective.

One more thing: cleaning has psychological benefits too. It's concrete action. You're doing something visible. That sense of agency matters when you're dealing with illness. Just don't trick yourself into thinking cleaning is more important than vaccination, hand washing, or staying home when sick. It's one layer in a multi-layered approach.

Estimated data shows that insufficient duration and incorrect timing are the most common hand washing mistakes, followed by face touching and inappropriate soap type.

Air Quality and Ventilation: When It Actually Matters

The conversation around air purifiers has gotten confusing because marketers have monetized anxiety.

Here's the honest answer: there's limited real-world evidence that residential air purifiers significantly reduce respiratory illness transmission. They can improve indoor air quality by removing allergens and pollutants, which has other benefits. But preventing flu and cold spread? The data isn't there.

Why? Because viruses are transmitted primarily through respiratory droplets in close proximity, and sometimes through touching contaminated surfaces. An air purifier works on airborne particles over time, but it doesn't reach you immediately after someone coughs in your face.

What does work better: ventilation.

Open a window. Really. This is free, requires no equipment, and has actual evidence behind it. When you open a window, you're exchanging indoor air (potentially contaminated) with outdoor air (where virus concentration is minimal). You're diluting viral load in the space.

In winter, opening a window feels counterintuitive. It's cold. Your heating bill goes up. But if someone in your house is sick and you want to reduce transmission risk to others, opening a window is effective and costs nothing.

For workplaces and public buildings, HVAC systems matter. Spaces with good air circulation and frequent air exchange have lower infection rates. This is where proper ventilation becomes infrastructure-level and isn't something individuals control.

The practical advice for your home:

-

When someone's sick: Open a window or two for at least 15 minutes several times a day. This dramatically reduces airborne virus concentration in the space.

-

If you live somewhere cold: Close the window in between, let it warm up again. You're not trying to freeze your house. You're creating ventilation cycles.

-

If someone is high-risk: Consider investing in a HEPA air purifier for their bedroom. They spend 8 hours there. Removing airborne particles over that period might help. But don't think it's a replacement for the other strategies.

-

In your workspace: If your office has windows that open, crack one during flu season. Push for workplace policies around ventilation if you can.

What to Do If You Actually Get Sick

Okay, so you did everything right. And you still got sick. It happens. The vaccine is 56% effective, not 100%. You got unlucky.

Here's what actually works when you're symptomatic:

Rest: Your immune system is fighting an infection. Your body needs energy for that. Rest isn't just comfort—it's essential for recovery. This isn't debatable.

Hydration: Viruses don't live in well-hydrated systems the way they do in dehydrated ones. Drink water, tea, broth, whatever. Just maintain hydration.

Symptom management: Fever is your immune system working. Running 100-101 degrees is actually your body doing its job. You don't need to suppress that aggressively. But if you're uncomfortable or running 103+, fever reducers (acetaminophen or ibuprofen) are reasonable. Follow dosing instructions.

Cough suppression: If a cough is preventing sleep, a cough suppressant might help. But coughing itself is productive—it's clearing secretions from your respiratory tract. You don't want to suppress it completely during the day.

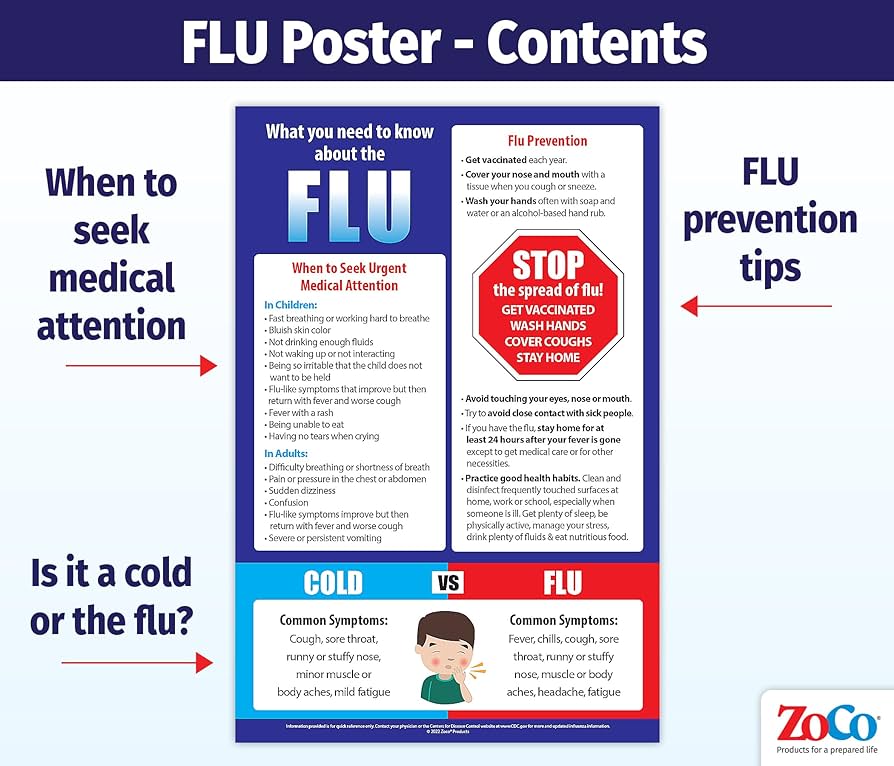

When to see a doctor: If you're experiencing severe shortness of breath, chest pain, confusion, or if you're in a high-risk category (elderly, immunocompromised, pregnant) and you have flu symptoms, get medical attention. Most colds and mild flu resolve on their own, but serious cases need professional evaluation.

Antiviral medication: For flu, antivirals like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) can reduce illness duration by about one day if started within 48 hours of symptom onset. They're more useful for high-risk patients. Talk to your doctor.

Common cold treatments: There's no specific antiviral for the common cold. Treatment is supportive (rest, fluids, symptom management). Most colds resolve in 7-10 days regardless of treatment.

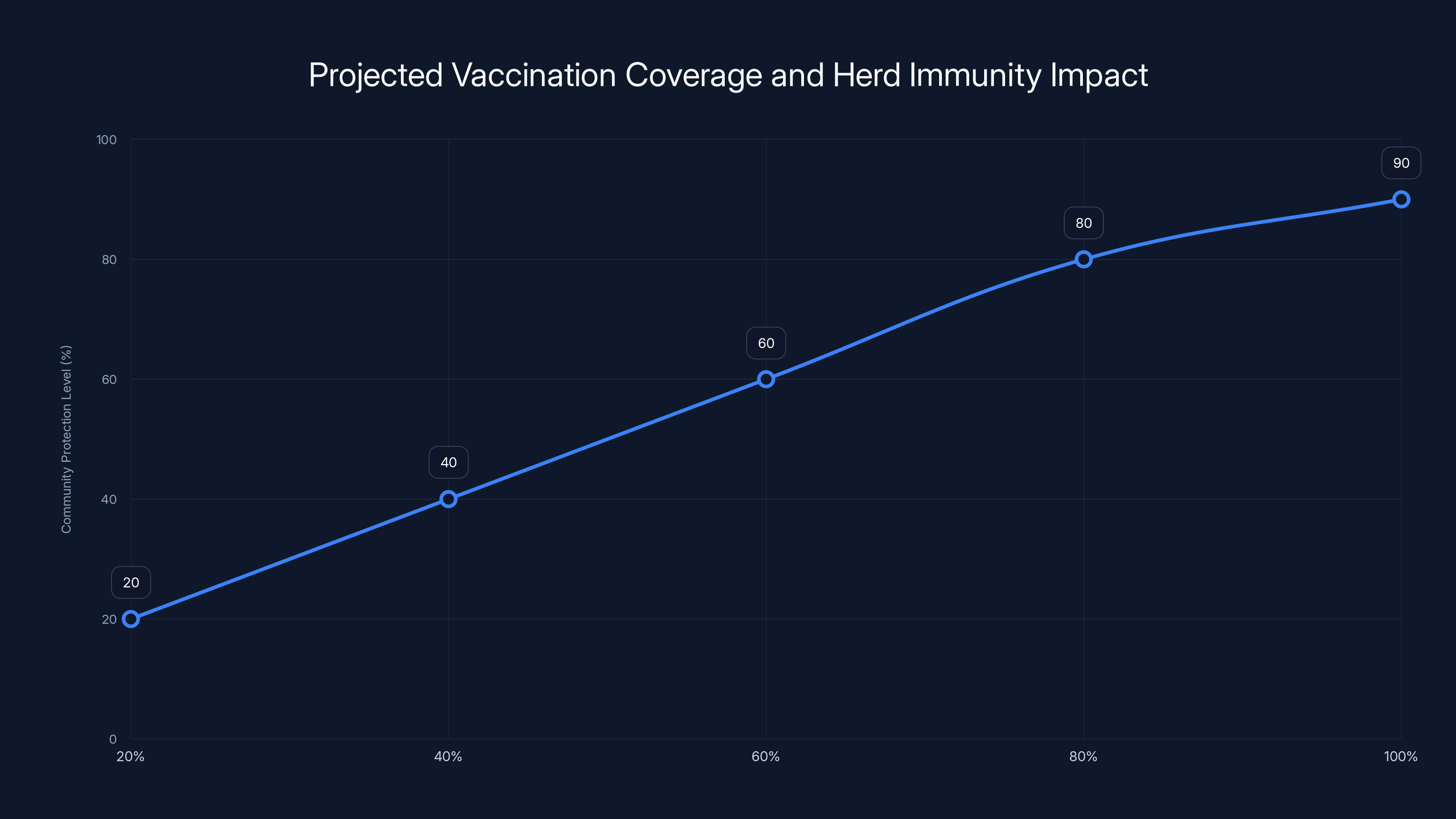

As vaccination coverage increases, community protection levels rise, approaching herd immunity thresholds around 70-80%. Estimated data.

When to Wear a Mask (and When It's Actually Effective)

Mask guidance has become politically charged, which is unfortunate because the science is actually straightforward.

Masks work. They reduce transmission. That's not controversial in epidemiology. What matters is the type, the fit, and the context.

N95 respirators: These filter incoming air, so they protect the wearer. Fit is critical—they need to seal properly around your face. If you're in a high-risk environment (hospital, public transit during peak flu season, around immunocompromised people) and you're concerned about transmission, an N95 with proper fit works.

Surgical masks: These primarily protect others from your respiratory droplets. If you're sick and need to be around people, a surgical mask reduces transmission to them. It's about communal responsibility.

Cloth masks: These are the least effective. They reduce droplet transmission, but the protection is limited compared to N95s or surgical masks.

When it matters most: High-crowding environments (public transit, hospitals, airports) during peak transmission (January-February) with vulnerable people present. That's your high-risk scenario.

When it's less critical: Outdoors (airborne virus dilutes rapidly), small group settings with healthy people, remote work environments.

Here's the nuance: masking consistently in low-risk situations probably doesn't provide commensurate benefit to the inconvenience. But strategic masking in specific scenarios? That's evidence-based disease prevention.

The practical approach: Keep masks available. Use them in high-risk situations. Don't obsess about them in low-risk settings. Normal life should still be possible.

Sleep, Stress, and Immune Function

This might seem tangential, but it's actually central to respiratory illness prevention.

Your immune system fights viruses. Your sleep regulates immune function. The connection isn't mysterious—it's biochemical.

When you're sleep-deprived, your immune response weakens. This isn't your imagination. This is measurable in white blood cell counts and antibody production. You're literally less capable of fighting off infection when you're tired.

The recommendation is 7-9 hours per night for most adults. I know that's not always realistic. But the closer you can get, the better your immune response.

Stress works similarly. Chronic stress suppresses immune function. This is why you get sick right after a stressful project or during high-anxiety periods. Your body can only manage so many threats simultaneously.

So what's actionable?

-

Prioritize sleep during flu season: Yes, even if it means saying no to some social events or work. Your recovery capacity is higher when you're well-rested.

-

Manage stress where possible: Exercise helps. Sleep helps. Meditation helps. Whatever works for you. Stress management is immune system management.

-

Recognize the compounding effect: Vacation + stress management + sleep + vaccination + hygiene practices = robust immune response. Any one thing alone is incomplete.

Vaccination Coverage and Community Protection

Here's where it gets bigger than you.

When vaccination rates increase in a community, even unvaccinated people benefit. This is called herd immunity. When enough people are immune (whether from vaccination or previous infection), the virus can't find hosts and transmission breaks down.

For flu, herd immunity threshold is around 70-80% of the population. We're nowhere near that in most communities.

But the principle still applies locally. When your workplace, your household, or your social circle has high vaccination rates, virus transmission slows. Your unvaccinated neighbors (if you have them) are less likely to catch flu because the virus isn't circulating as much.

This matters because it means your vaccination decision affects others. When you get vaccinated, you're not just protecting yourself. You're reducing transmission to:

- Infants too young for vaccination

- Elderly people with weaker immune systems

- Immunocompromised people who can't mount adequate immune response even with vaccines

- People with medical conditions that contraindicate vaccination

These populations depend on community vaccination rates. They can't rely on vaccines to protect them, so they rely on everyone else being vaccinated.

If you're generally healthy and young, you might think the vaccine is less important for you personally. But you might share living space with someone older or more vulnerable. You might see your grandparents. You might work with immunocompromised colleagues.

The vaccine you get protects them.

Specific Strategies for High-Risk Groups

If you fall into a high-risk category, your approach should be more aggressive.

High-risk groups include:

- People 65 and older

- Pregnant people

- People with chronic medical conditions (heart disease, diabetes, asthma, chronic lung disease)

- People who are immunocompromised (HIV, cancer treatment, immunosuppressant medications)

- Healthcare workers

- Parents of young children

For these groups, additional precautions make sense:

Vaccination is non-negotiable: Get vaccinated every year, without exception. The benefit is higher for you because the risk of severe illness is higher.

Consider pneumococcal vaccination: This is a separate vaccine that protects against bacterial pneumonia, which can follow respiratory illness. Discuss with your doctor.

Be more selective about exposure: You might avoid large gatherings during peak flu season. You might choose remote work if available. You might ask guests to mask if they're sick.

Antivirals on hand: If you're very high-risk, ask your doctor about having antivirals available before flu season. Starting them early in illness can make a meaningful difference.

Get tested early if symptomatic: If you have symptoms and you're high-risk, getting a rapid flu test and starting antivirals within 48 hours can prevent hospitalization.

Communicate your needs: Tell family and friends that you're being cautious because you're higher-risk. Good people will understand and help you stay healthy.

The core principle: your baseline risk is higher, so your protective actions should be more aggressive.

When It's Not Actually a Cold or Flu

Not every respiratory illness is cold or flu. This matters because your response depends on the actual illness.

RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus): Similar symptoms to cold, but can be more severe in older adults and young children. Treatment is supportive like the common cold. Prevention is similar (hand washing, mask wearing).

COVID-19: Symptoms overlap with cold and flu. Rapid testing is available. Treatment depends on risk factors and severity. If you've been vaccinated for COVID, you have baseline protection.

Pertussis (Whooping Cough): Starts like a cold but develops a distinctive, severe cough. Vaccination is highly effective at prevention. If you're around infants, pertussis vaccination (as a booster) protects them.

Strep throat: Bacterial infection, not viral. Sore throat, fever, no cough. Rapid test required. Antibiotics are treatment. This doesn't spread the same way viruses do.

The practical advice: if symptoms are severe, lasting more than 10 days, or you're high-risk, get medical evaluation. Don't assume it's a cold and wait it out.

Planning Ahead: Building Your Flu Season Defense

Don't wait until October to think about this. Build your defenses now.

In August:

- Check your vaccination status and schedule a flu vaccine appointment for September

- If you're high-risk, schedule your pneumococcal vaccine if needed

- Talk to your doctor about your specific risk factors and supplemental precautions

In September:

- Get your flu vaccine

- Stock basic supplies: tissues, hand sanitizer, thermometer, over-the-counter pain relievers

- Decide on your personal approach to masks and masking scenarios

- Brief your workplace or social circle on illness policies

In October through April:

- Monitor your local flu activity (CDC publishes this weekly)

- Maintain sleep, exercise, and stress management

- Practice hand hygiene without obsessing

- Stay home if you get sick

- Support others in doing the same

If you do get sick:

- Rest and hydrate

- Stay home for 5-7 days or until fever-free for 24 hours

- Use supportive care (symptom management, not suppression)

- Seek medical attention if symptoms worsen

This isn't complicated. It's just deliberate.

The Honest Assessment: You Might Still Get Sick

Let's be real: even doing everything right, you might catch something this season.

The vaccine is 56% effective, not 100%. Hand washing is protective, not foolproof. Staying home when sick is responsible, but you might not realize you're sick until you're already contagious.

That's okay. That's just statistics. The goal isn't zero illness. The goal is reducing severity and transmission.

If you get sick:

- It should be milder because of vaccination

- It should last fewer days

- You're less likely to need hospitalization

- You're spreading a lower viral load to others

That's not failure. That's success in epidemiological terms.

The bigger picture: cold and flu season is inevitable. Illness is part of life. But severe illness, hospitalization, and complications aren't inevitable. Those are preventable through the strategies outlined here.

You have agency. Use it.

Beyond This Season: Building Year-Round Habits

The practices discussed here aren't just for flu season. Building these habits now makes them automatic when you need them most.

Hand washing becomes routine. Not touching your face becomes reflex. Staying home when sick becomes normal. Keeping masks available becomes automatic. Getting vaccinated becomes expected.

These aren't temporary measures. They're part of living in a world where respiratory illnesses exist and can affect you and others.

The good news: they're not burdensome. They're not expensive. They're just... normal. Do them now, make them habitual, and when flu season arrives, you're already positioned to handle it.

That's the win. Not perfection. Not zero illness. Just being intentional instead of resigned.

FAQ

What is the flu vaccine and how does it work?

The flu vaccine is an annual immunization that trains your immune system to recognize and fight influenza viruses. It contains either inactivated (killed) viruses or just viral proteins. When your immune system encounters these components, it produces antibodies without causing illness. When you're later exposed to actual flu viruses, your antibodies recognize them immediately and mount a faster, stronger defense, reducing your risk of getting sick or having severe illness.

How long does it take for the flu vaccine to become effective?

The flu vaccine typically takes up to two weeks to reach full effectiveness. During those two weeks, your immune system is building its defense through antibody production. If you're exposed to flu within this window, you could still get sick because your immune system hasn't finished its preparation. This is why timing matters—getting vaccinated in September or October ensures you're fully protected during peak flu season in January and February.

Can the flu vaccine give me the flu?

No. The flu shot is made with inactivated (killed) viruses or viral proteins, so you cannot get the flu from it. The nasal spray vaccine contains weakened live viruses, but they're attenuated to the point where they won't cause illness in healthy people ages 2 to 49. Some people experience mild side effects like arm soreness or low-grade fever after vaccination, but this is your immune system being trained, not actual illness.

Why should I stay home when I'm sick if I feel fine?

Staying home when you're sick reduces virus transmission to others, even if you feel okay. You're most contagious during the first 5-7 days of illness. By staying home, you prevent spreading virus to vulnerable people (elderly, immunocompromised, infants) who depend on community responsibility. You're also reducing the total amount of virus circulating in your community, which benefits everyone's health in the long term.

What's the most effective way to wash my hands to prevent illness?

Wash your hands for at least 20 seconds with soap and water, scrubbing all surfaces including between fingers, under nails, and up your wrists. The 20-second duration is the key—that's how long it takes soap to break down the lipid membranes of viruses. Focus on washing after using the bathroom, before eating, after touching public surfaces, and before and after caring for sick people. Regular soap works as well as antibacterial soap.

Should I use an air purifier to prevent flu and colds?

Research doesn't show that residential air purifiers significantly reduce respiratory illness transmission in real-world conditions. However, they can improve indoor air quality by removing allergens. For actual virus reduction, opening a window for ventilation is more effective and costs nothing. Window opening can reduce airborne virus concentration by up to 70% within 5 minutes. If someone in your household is high-risk, a HEPA air purifier in their bedroom might provide supplemental benefit, but it shouldn't replace other prevention strategies.

What's the difference between vaccine effectiveness and vaccine efficacy?

Vaccine efficacy measures disease prevention in controlled trials with ideal conditions and carefully selected participants. Vaccine effectiveness measures disease prevention in the real world where conditions are messy and exposure is random. Effectiveness is what actually matters to you because it reflects how the vaccine performs in your real life, not laboratory conditions. For flu, a 56% effectiveness rating means vaccinated people had about half the risk of needing medical care for flu compared to unvaccinated people.

When should I wear a mask to prevent respiratory illness?

Mask effectiveness depends on type, fit, and context. N95 respirators protect the wearer but require proper fit. Surgical masks protect others from your respiratory droplets. Cloth masks offer limited protection. Masks are most valuable in high-crowding environments (public transit, hospitals) during peak transmission (January-February) around vulnerable people. For low-risk situations outdoors or in small groups with healthy people, masking provides minimal additional benefit relative to inconvenience.

Final Thoughts: Your Power in Cold and Flu Season

Cold and flu season feels like something that happens to you. A wave of illness that sweeps through your community, and you're either lucky or unlucky.

But that's not accurate. You have genuine power here. The strategies outlined in this guide—vaccination, hand hygiene, staying home when sick, ventilation, sleep prioritization—these are proven approaches that demonstrably reduce your illness risk and transmission to others.

The shift is simple: from resignation to intentionality.

From "I guess I'm getting sick this winter" to "Here's what I'm doing to reduce that risk."

From "It is what it is" to "I have actual agency here."

You do. Use it. Get vaccinated in September. Wash your hands consistently. Stay home when sick. Sleep well. Manage stress. These aren't burdensome. They're normal, evidence-based practices that make a measurable difference.

Cold and flu season is coming. But you're not resigned to it anymore. You're prepared.

Key Takeaways

- Get vaccinated in September or October for 56% protection against severe illness and peak effectiveness during January-February peak season.

- Wash hands for 20 seconds with soap and water, avoid touching your face, and stay home when sick to break transmission chains.

- Window ventilation reduces airborne virus concentration by up to 70% and is more effective than air purifiers for real-world protection.

- Sleep, stress management, and community vaccination rates are foundational to personal and population-level health protection.

- Your vaccination and hygiene choices directly protect vulnerable populations too young, too old, or too immunocompromised to protect themselves.

Related Articles

- 12 Most Exciting Cameras in 2026: DJI 360 Drone to iPhone 18

- Best Smart Scales 2026: Complete Guide & Alternatives

- The Complete Tech Cleanup Checklist for 2025: 15 Essential Tasks

- Complete Acuity Scheduling Review & Setup Guide [2025]

- Shark Vacuum Design Problems: Why They All Fail [2025]

- UK Drone Laws: Complete 2025 Guide to Camera Regulations [Updated]

![Complete Guide to Cold & Flu Prevention [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/complete-guide-to-cold-flu-prevention-2025/image-1-1767265541413.jpg)