The Door Dash Food Tampering Incident That Exposed Gig Economy Safety Gaps

On December 7, an ordinary evening in Evansville, Indiana turned into a nightmare when a family's Door Dash delivery became a criminal weapon. A man and his wife ordered fast food through the popular delivery platform, expecting a routine meal. Instead, they experienced severe physical reactions—vomiting, burning sensations throughout their mouths, noses, throats, and stomachs—after consuming food that had been deliberately contaminated. The culprit wasn't a disgruntled restaurant employee. It was the delivery driver herself.

This incident isn't just about one bad actor or a single platform failure. It's a window into systemic vulnerabilities that plague the gig economy, where hundreds of thousands of drivers operate with minimal oversight, background checks that vary wildly in rigor, and platforms that prioritize speed over genuine safety. When you order food from Door Dash, Uber Eats, Grubhub, or similar services, you're trusting a stranger—someone you've never met, whose background you'll never truly verify—to handle your food safely. That trust, as this case demonstrates, can be shattered in seconds.

The Evansville case involved Kourtney Stevenson, a Kentucky resident who was working for Door Dash while visiting her father in Indiana. According to the Vanderburgh County Sheriff's Office, after dropping off the food and snapping the required delivery photo, Stevenson allegedly pulled a small aerosol can from her keychain and sprayed a substance directly onto the customers' food. That substance, she later claimed, was pepper spray—deployed, she said, to kill a spider.

But here's where the story takes a darker turn. The temperature that evening had dropped to 35 degrees Fahrenheit, and the Indiana sheriff's department noted something critical: outdoor spiders in Indiana simply don't remain active at such cold temperatures. They can't crawl on exposed surfaces. The explanation didn't hold up. Instead, prosecutors alleged she was using pepper spray as a weapon, deliberately contaminating food meant for human consumption.

When detectives asked her to come in for an interview, Stevenson allegedly refused. This refusal gave investigators probable cause to obtain an arrest warrant. She now faces two serious charges: battery resulting in a moderate injury and consumer product tampering—both felonies in Indiana. As of late 2025, she awaits extradition from Kentucky to face these charges in Indiana. Meanwhile, Door Dash moved swiftly to ban her from the platform, but the damage was already done.

This article examines what this case reveals about gig economy safety, platform accountability, the psychology of driver misconduct, the regulatory landscape, and what consumers can actually do to protect themselves in an industry that often prioritizes convenience over security.

TL; DR

- Criminal incident: A Door Dash driver allegedly sprayed customers' food with pepper spray in December 2024, resulting in felony charges for battery and product tampering

- Platform response: Door Dash banned the driver but faces questions about how such incidents occur despite background checks and delivery verification systems

- Systemic issue: The gig economy lacks standardized safety protocols, consistent background vetting, and meaningful consequences for platform negligence

- Consumer vulnerability: Millions use delivery apps daily with minimal understanding of actual safety safeguards or recourse options

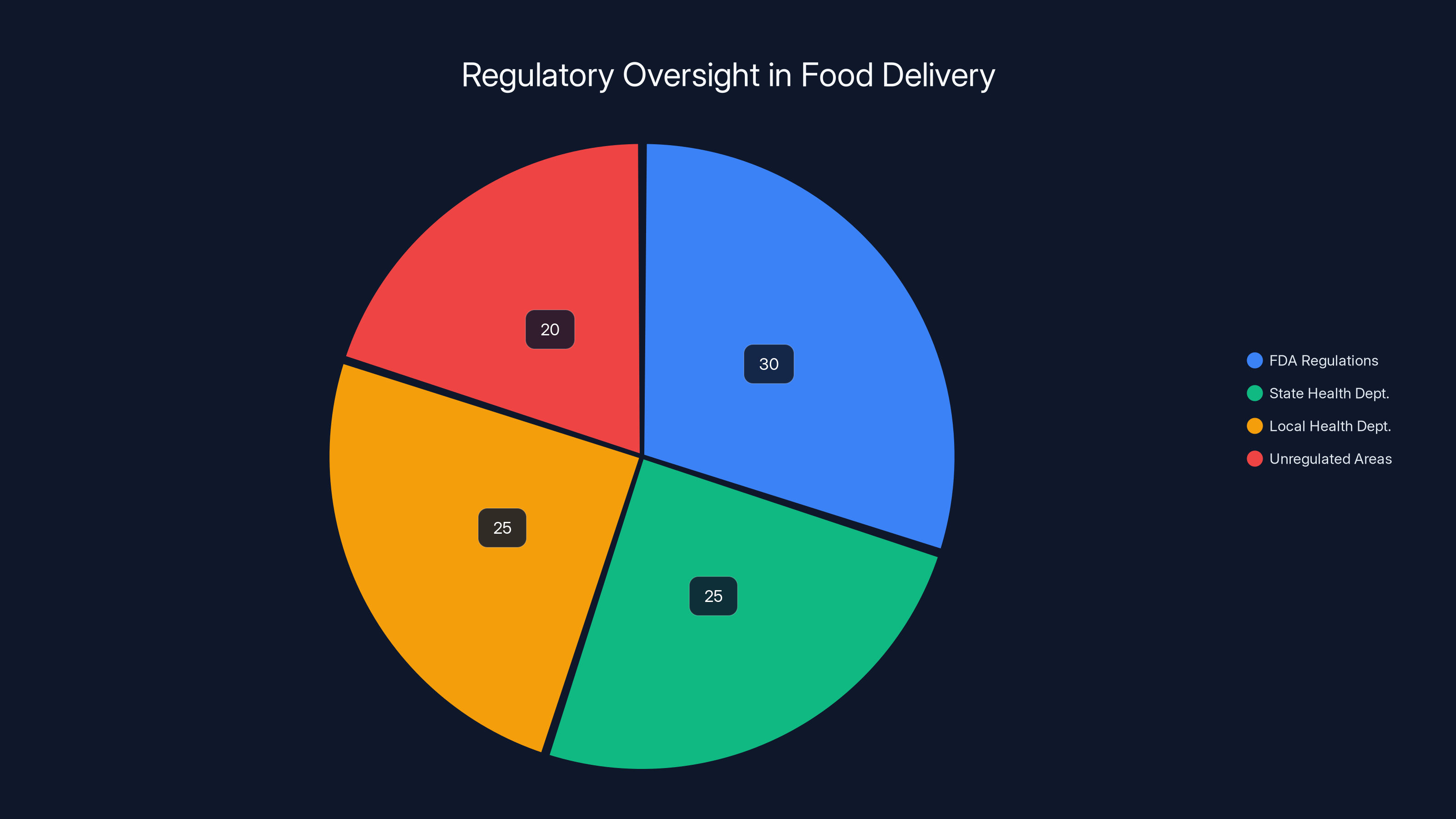

- Regulatory gap: No federal standards govern food safety in gig delivery, leaving oversight fragmented across state and local jurisdictions

- Bottom line: One incident doesn't define an industry, but it exposes how quickly trust can be weaponized when accountability systems are weak

Estimated data suggests that while worker reclassification may offer the highest effectiveness in improving safety, it also poses the greatest cost impact. Technological solutions provide a balanced approach but still involve significant costs.

The Complete Timeline: From Order to Arrest

Understanding how quickly a routine transaction became a criminal case helps illustrate the specific vulnerabilities in the system.

December 7: The Order and Delivery

The victims ordered fast food through Door Dash—the app matched them with Stevenson as their delivery driver. She accepted the order, picked it up from the restaurant, and navigated to the residential address. Nothing appeared unusual during the order placement or pickup. The customers had no warning that their food had been compromised.

Upon arrival, Stevenson performed the standard Door Dash protocol: she dropped the food at the door and took a photo to confirm delivery. This photo is crucial. Drivers must photograph the delivery to prove completion, and this creates a timestamped record. But it also means Stevenson knew the exact moment she needed to act. Immediately after snapping that photo, she allegedly accessed the small pepper spray canister attached to her keychain and sprayed the food in the delivery bag.

The entire interaction lasted perhaps two minutes. The family had no way of knowing their meal had been weaponized.

The Physical Symptoms Emerge

Within minutes of eating, the customers noticed something was wrong. The burning sensation was unmistakable—not the heat of spice or hot sauce, but the chemical burn of pepper spray. Both the man and woman vomited. They experienced severe burning in their mouths, noses, throats, and stomachs. The symptoms were acute and alarming enough that they immediately suspected foul play.

Here's what many people don't realize: pepper spray symptoms can be severe. Capsaicin, the active ingredient in pepper spray, binds to pain receptors and can cause temporary blindness, respiratory difficulty, and gastrointestinal distress. While the symptoms typically subside within an hour or so, they're intensely uncomfortable and can be genuinely dangerous for people with respiratory conditions, heart problems, or severe allergies.

The Doorbell Camera Evidence

The family had security camera footage from their doorbell—a technology that's becoming increasingly common in U.S. households. They reviewed the video and noticed something the naked eye might have missed: a red substance appeared to have been sprayed onto the delivery bag. The video clearly showed Stevenson pulling out the aerosol can and spraying the food after dropping it off.

This footage became the critical piece of evidence. It wasn't circumstantial. It wasn't a he-said-she-said situation. It was visual proof of the act itself.

The Investigation Accelerates

The victims reported the incident to the Vanderburgh County Sheriff's Office. Detectives pulled Door Dash's records and identified Stevenson as the driver. When they contacted her, she provided an explanation: she claimed she'd used pepper spray to spray a spider that was on the food.

That's when the investigation took a turn that would ultimately undermine her defense. The sheriff's department noted the specific weather conditions that evening. With overnight lows of 35 degrees Fahrenheit, outdoor spiders in Indiana aren't active. They don't crawl on exposed surfaces in December. The timing didn't make biological sense.

The Warrant and Charges

When Stevenson allegedly refused to come in for a formal interview, detectives obtained an arrest warrant. She was charged with two felonies: battery resulting in a moderate injury (the capsaicin contact with the victims' bodies) and consumer product tampering (deliberately contaminating food intended for sale and consumption). These aren't minor charges. Battery with moderate injury can carry substantial prison time, and tampering with consumer products is taken seriously by prosecutors across the country.

Stevenson now faces extradition from Kentucky to Indiana to answer these charges.

Estimated data shows that incomplete records and misidentification are common issues in background checks, each affecting around 25-30% of cases. These gaps highlight the limitations of current systems in ensuring safety.

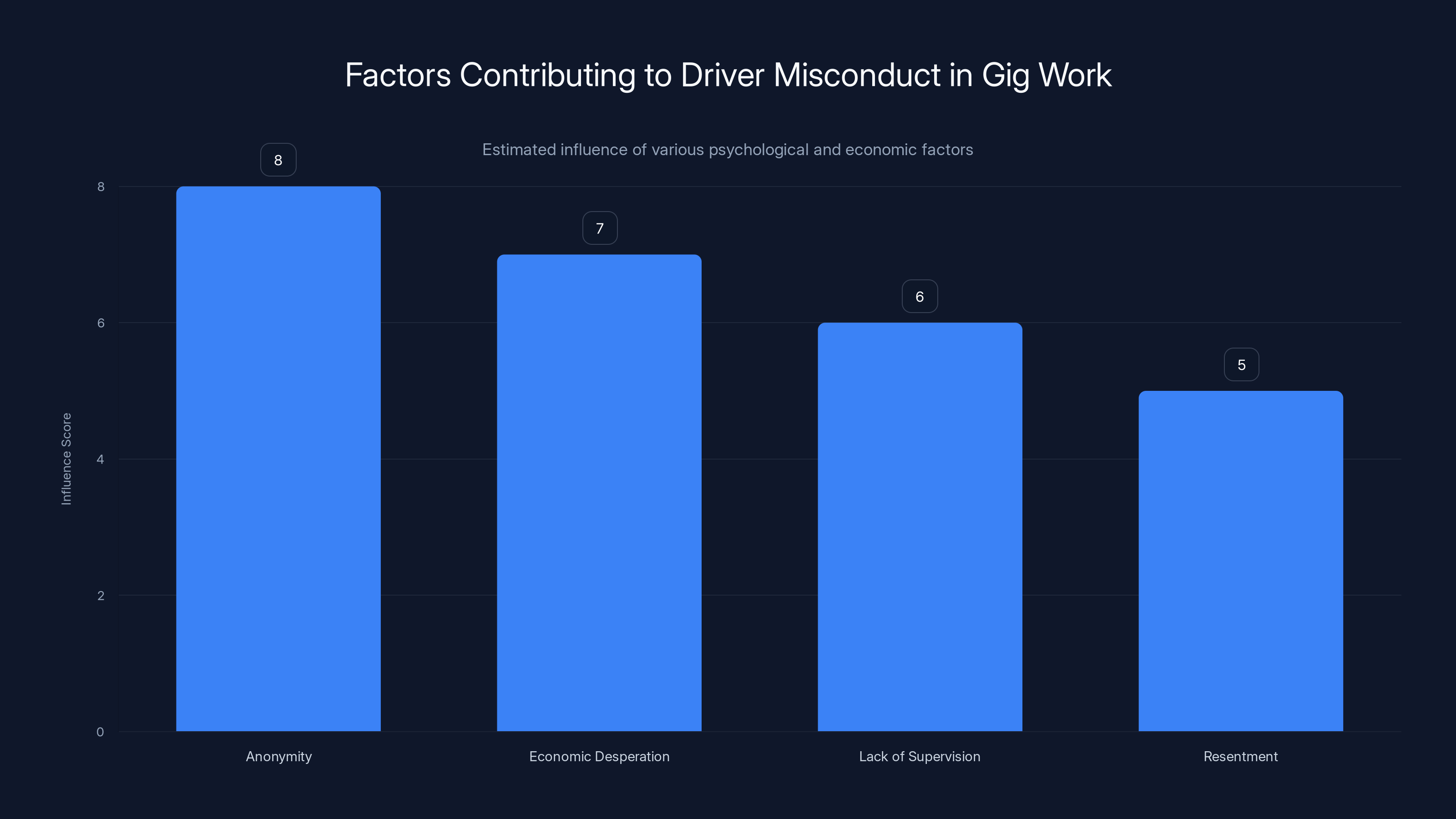

Why This Happened: The Psychology of Driver Misconduct in Gig Work

One of the most unsettling aspects of this case is the randomness of it. The family did nothing to provoke this driver. They placed an order, it was assigned to her, and for reasons that remain unclear, she allegedly chose to contaminate their food. Understanding why gig economy drivers commit these acts is crucial for preventing them.

The Anonymity Factor

Gig economy work fundamentally changes the relationship between worker and customer. In traditional employment, workers develop reputation within their organization, face direct supervision, and have social connections to colleagues that create accountability. In gig work, interaction is transactional and often one-time only. A driver may never serve the same customer twice. They may never see the person again. The anonymity creates a psychological distance that can lower inhibitions against harmful behavior.

Research in behavioral psychology shows that anonymity increases the likelihood of antisocial behavior. When people believe their actions won't be traced back to them personally, or that they won't face direct consequences, they're more likely to act against social norms. The gig economy amplifies this effect. A driver can reason, "I'll never see these people again. I'll never work in this neighborhood again. What are the odds this gets traced to me?"

The problem is that reasoning is wrong. Technology creates detailed records. Apps log driver locations, times, and routes. Cameras document deliveries. GPS data creates an unambiguous trail. Yet many gig workers may not fully appreciate how thoroughly their actions are tracked.

Economic Desperation and Resentment

Gig economy work is notoriously low-paying. Average Door Dash driver earnings range from

While most drivers respond to low pay by working longer hours or switching platforms, some respond with anger directed at customers. In their mind, customers are privileged people who can afford to have food delivered—a luxury. Drivers resent the gap between what customers pay for convenience and what drivers actually earn. This resentment can fester, especially after difficult shifts or personal problems.

The Evansville case occurred in December, during the holiday season when delivery volume increases but pay rates don't improve proportionally. Whether Stevenson's alleged actions stemmed from financial stress remains unclear, but the timing coincides with a period when gig workers are typically most exhausted and least well-compensated.

Lack of Accountability and Consequences

For gig workers, the consequences for most infractions are merely deactivation from the app. You can't be fired in the traditional sense because you're not an employee. You can be deactivated, which means you lose access to work on that platform. But you can move to another platform, work elsewhere, or operate in a different market.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. If you're already deactivated from one platform, the fear of further deactivation diminishes. And if you've never faced serious legal consequences, the risk might not feel real. For Stevenson, apparently, the decision to spray pepper spray on food didn't register as something that would result in felony charges. Perhaps she assumed it would be treated as a complaint, a deactivation, and nothing more.

The legal system's intervention—arrest warrants, felony charges, extradition—represents a stark awakening to the reality that actions have consequences beyond platform deactivation. But this awakening comes only after the harm is done.

Platform Responsibility: What Door Dash Failed to Prevent

When a Door Dash driver commits a crime, how much responsibility does Door Dash itself bear? This is the central legal and ethical question the incident raises.

Background Checks: The Baseline That Isn't Enough

Door Dash, like most gig delivery platforms, conducts background checks on drivers before they can work. These checks typically screen for felony convictions, serious misdemeanors, and disqualifying offenses. The specifics vary by jurisdiction, but generally they're checking whether a driver has a criminal history that would make them unsuitable for customer-facing work.

The problem is that background checks only reveal past behavior. They don't predict future behavior. A person with a clean record can still commit crimes. A person who's never shown signs of violence or instability can snap. Stevenson apparently had no prior criminal history that would have flagged her during intake.

Moreover, background check companies have their own accuracy issues. Misidentification, incomplete records, and delayed processing mean some people with disqualifying histories slip through. And some jurisdictions don't maintain comprehensive criminal databases, making background checks incomplete.

Door Dash's background check system did what it was designed to do—verify that Stevenson had no obvious disqualifying history. But it couldn't predict that she would allegedly spray pepper spray on food. No background check can.

Delivery Verification and Visual Confirmation

Door Dash requires drivers to photograph each delivery to confirm completion. This serves multiple purposes: proof of delivery for customers and the company, deterrence of theft or abandonment, and ostensibly, a way to catch drivers who photograph fake deliveries.

But the photo requirement actually creates a perverse incentive for tampering. If a driver is going to contaminate food, they might do so after taking the photo, because they know they need that photo for the system. Stevenson allegedly sprayed the food immediately after photographing the delivery—the system actually provided her with a clear timeline for when to act.

Door Dash could theoretically enhance this system by requiring photos before and after leaving the door, or by requiring drivers to include themselves in the photo (to verify they're not using old images). But these enhancements would also slow down deliveries and frustrate drivers. There's a trade-off between security and speed, and Door Dash has consistently chosen speed.

Driver Monitoring and Behavioral Analysis

Door Dash has the technological capability to flag unusual behavior patterns. If a driver suddenly receives multiple complaints, experiences rating drops, or shows geographical anomalies in their delivery patterns, the system could flag them for review. Some platforms do implement these kinds of behavioral monitoring systems.

However, implementing robust behavioral monitoring requires significant investment in data science and investigation resources. It also requires a willingness to take action—to deactivate drivers based on pattern analysis rather than only on explicit complaints or criminal convictions. There's liability risk in taking action against a driver based on algorithmic flags without concrete evidence of wrongdoing.

In Stevenson's case, there's no indication that prior complaints or concerning patterns triggered a review. This was apparently an isolated incident, impossible to predict based on prior behavior.

The Regulatory and Liability Question

Can Door Dash be held legally liable for a driver's alleged criminal conduct? Generally, no. The company isn't responsible for the criminal actions of independent contractors. However, Door Dash can be held liable if it was negligent in hiring or retaining a driver—for instance, if it failed to conduct a background check, ignored multiple safety complaints, or continued working with someone known to be dangerous.

In this case, Door Dash would likely argue that it did everything reasonable: conducted a background check, implemented delivery verification, and quickly deactivated the driver when the incident came to light. That's probably legally sufficient to protect the company from negligent hiring claims.

But there's a broader question about whether the structural setup of the gig economy allows platforms to escape accountability too easily. Drivers are classified as independent contractors, which limits the company's legal responsibility for their actions. But the company controls the pricing, which affects driver behavior and potentially stress levels. The company controls deactivation, which is the primary threat keeping drivers compliant. The company controls the platform mechanics that govern how drivers interact with customers.

If Door Dash or other platforms wanted to invest in safety more seriously, they could. They choose not to, because the economics don't favor it. A food tampering incident is rare. The liability exposure is manageable. Investing heavily in driver behavior monitoring, training, and vetting would reduce margins and slow growth. From a pure business perspective, the current system is rational, even if it's not ethically ideal.

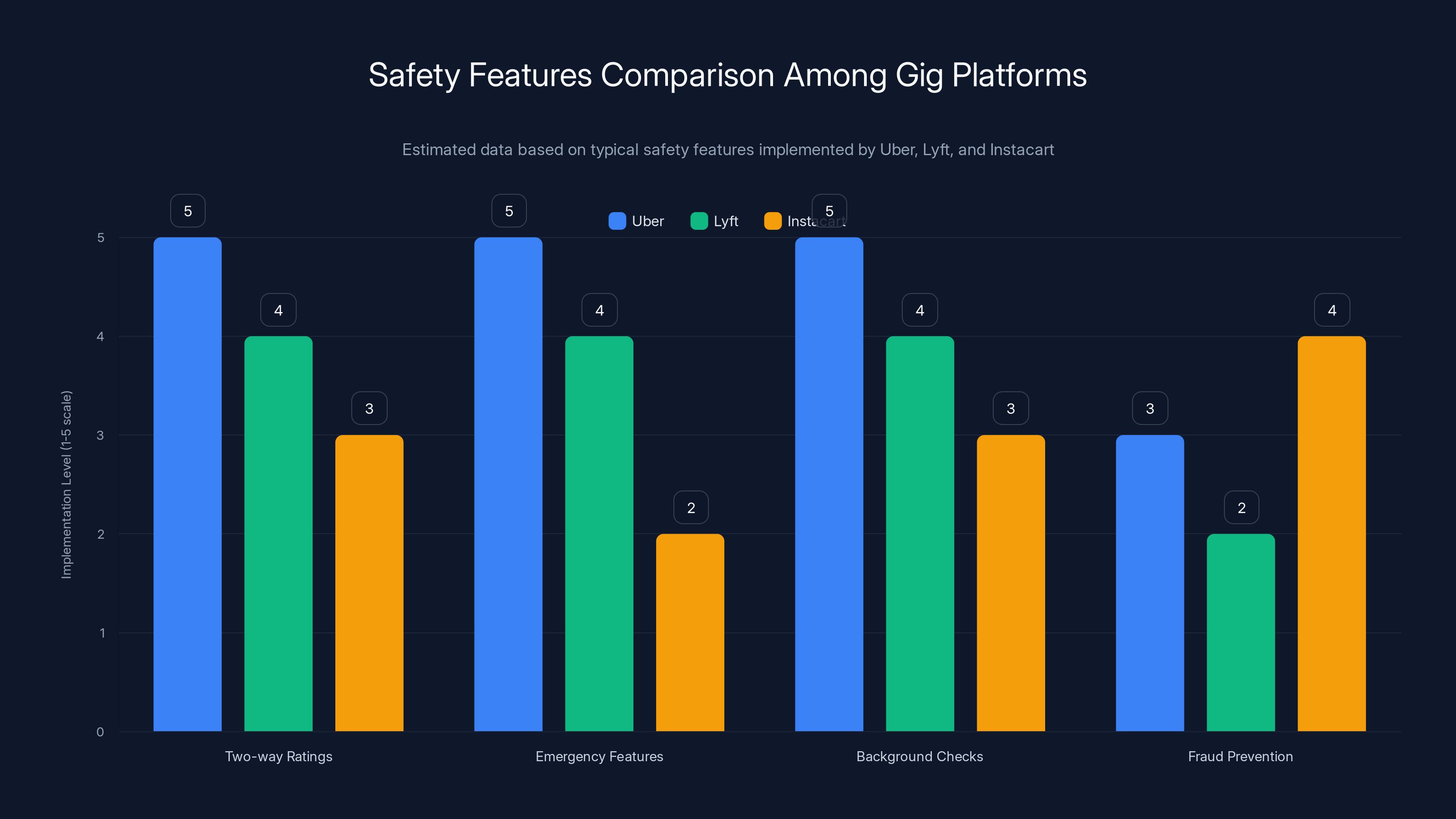

Uber leads in implementing comprehensive safety features, while Instacart focuses more on fraud prevention. Estimated data based on typical safety measures.

Food Safety in Gig Delivery: Regulatory Gaps and Standards

Food safety is heavily regulated at the federal, state, and local levels. Restaurants must meet strict health codes, undergo inspections, and maintain temperature-controlled environments. But once food leaves the restaurant in a Door Dash delivery, it enters a regulatory gray area.

The FDA's Jurisdiction Gap

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulates food safety for commercial food production and some aspects of food delivery. However, the FDA's primary focus is on food handling by businesses—restaurants, manufacturers, and wholesalers. Individual delivery drivers operating as independent contractors fall into a gray area.

The FDA has issued guidance on third-party food delivery services, recommending that platforms implement safety protocols. But recommendations aren't requirements. There's no federal mandate that Door Dash, Uber Eats, or Grubhub maintain specific safety standards for delivery drivers.

Furthermore, the FDA's jurisdiction is primarily over food quality—preventing contamination from bacteria, allergens, and chemical hazards that occur during storage or handling. Intentional tampering by a malicious actor is a different category of risk. It's a criminal act, not a food safety violation in the regulatory sense.

State and Local Health Departments

Indiana, like all states, has its own health department regulations governing food handling. However, these regulations primarily apply to food establishments—restaurants, catering companies, food trucks. They don't explicitly govern third-party delivery drivers, because delivery wasn't a significant industry when most food safety codes were written.

The incident in Evansville was prosecuted as a criminal matter (battery and product tampering) rather than a food safety regulatory violation. This makes sense legally, but it also illustrates the regulatory mismatch. There's a criminal law preventing tampering with consumer products, but there's no specific food safety regulation for third-party delivery drivers.

The Temperature Control Problem

Food safety depends partly on temperature control. Hot food should stay hot, cold food should stay cold. Bacteria grow rapidly in the "danger zone" between 40°F and 140°F. In a traditional restaurant, food goes from the kitchen directly to the customer (or to a delivery person in an insulated container). The time in the temperature danger zone is minimized.

In gig delivery, the timeline is longer. A Door Dash driver picks up food, travels to the customer's address (which might be 15-30 minutes away), and drops it off. During this time, insulation quality is paramount. But there are no standards mandating that Door Dash drivers use insulated bags or any particular level of food protection.

Door Dash and other platforms recommend using insulated bags, but many drivers use cheap or inadequate containers. The company doesn't provide standardized bags to drivers. This creates a food quality issue separate from intentional tampering, but it illustrates the broader lack of standards.

What Regulation Could Look Like

A more rigorous food safety framework for gig delivery could include:

- Mandatory food handler certification for all delivery drivers, similar to what many restaurants require for employees

- Standardized insulated bag requirements and periodic inspection

- Temperature monitoring using devices that record temperatures during delivery

- Photo evidence standards requiring visual verification that food is properly contained

- Incident reporting requirements mandating that platforms report potential tampering to health departments

- Driver training requirements on food safety and handling

- Liability insurance that covers food safety issues

None of these are currently mandated at the federal level. Some states or municipalities have begun implementing portions of these, but the landscape is fragmented and inconsistent.

The Legal Framework: Criminal Charges and Prosecution Strategy

Stevenson's prosecution illustrates how criminal law addresses food tampering and how the Indiana legal system approached this case.

Battery Resulting in Moderate Injury

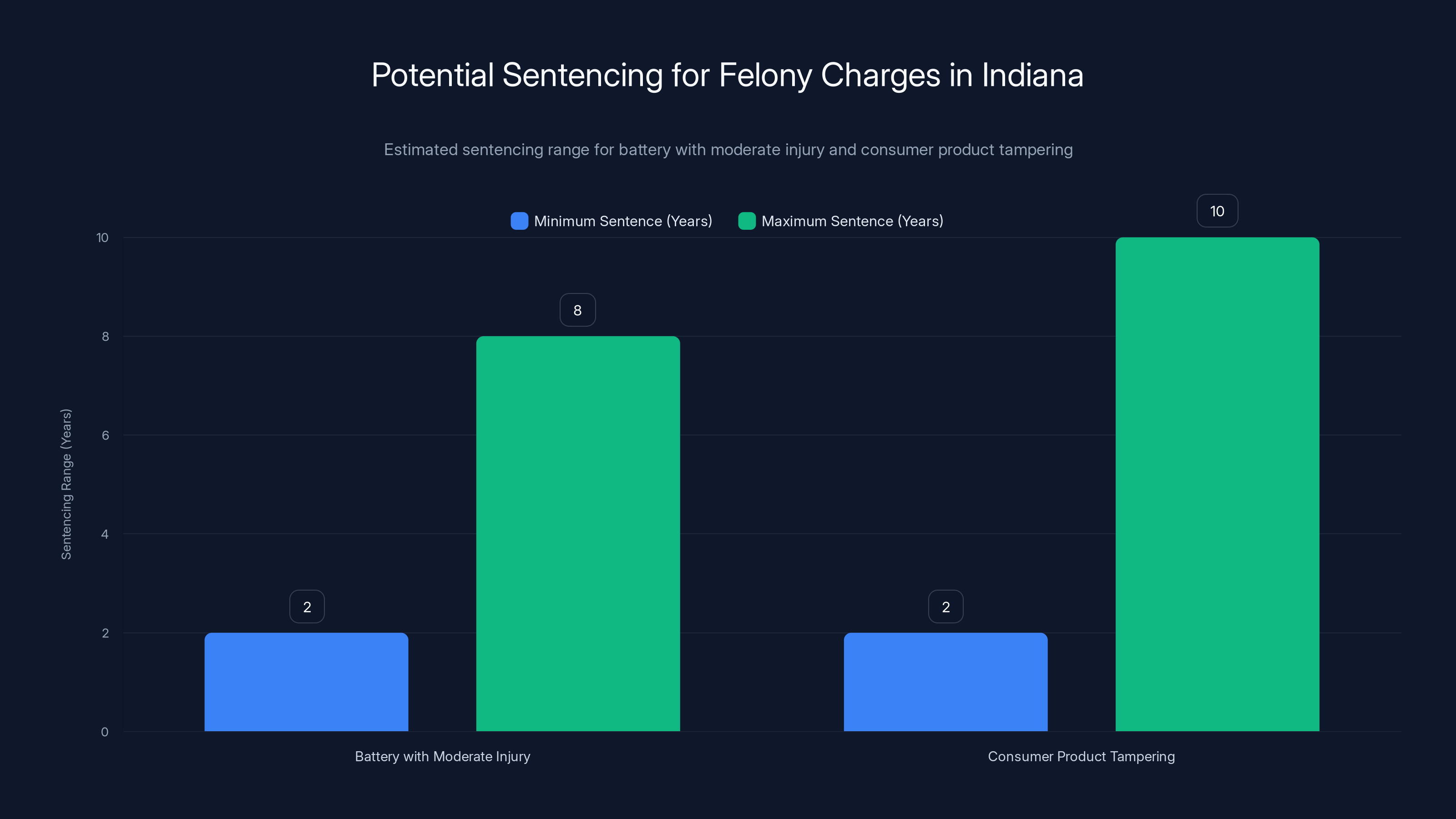

The first charge, battery resulting in moderate injury, is grounded in the fact that the pepper spray caused physical harm. Indiana law defines battery as intentionally or recklessly causing physical injury to another person by means of a deadly weapon or other means likely to cause serious bodily injury. The statute provides various gradations based on injury severity.

A "moderate injury" is typically defined as one that doesn't require extended hospitalization but causes more than minor discomfort—such as vomiting, severe burning sensations, and temporary incapacity. The victims' symptoms clearly exceeded minor discomfort and rose to the level of moderate injury.

Prosecutors can charge battery with moderate injury even though the victims didn't suffer long-term harm, because the statute focuses on the injury caused at the time of the incident, not lasting consequences.

Consumer Product Tampering

The second charge, consumer product tampering, addresses the deliberate contamination of food intended for sale. Most states, including Indiana, have specific statutes criminalizing product tampering. These statutes were enacted partly in response to high-profile cases like the Tylenol tampering murders of 1982, when someone contaminated Tylenol capsules with cyanide, killing seven people.

Product tampering statutes are intentionally broad and severe. They criminalize any deliberate contamination of a consumer product, even if the contamination doesn't cause serious harm. The theory is that product tampering undermines public confidence in consumer products and creates immense danger if it becomes a trend.

In Stevenson's case, she allegedly tampered with food—a consumer product—by spraying it with pepper spray. The charge doesn't require that the tampering cause any specific level of harm. The act of tampering itself is the crime.

Product tampering charges typically carry significant penalties. In Indiana, they can result in felony convictions with prison sentences ranging from two to eight years, depending on whether anyone was harmed.

Prosecution Burden and Evidence

To prosecute these charges, the state must prove:

- Identity: That Stevenson was the driver who made the delivery (Door Dash records establish this)

- Intent: That she deliberately sprayed the food with knowledge that it would cause harm (the doorbell camera shows the spray action; the temperature explanation undermines her spider-spray claim)

- Causation: That her actions caused the victims' injuries (the victims' symptoms match pepper spray exposure; the timing matches the delivery)

The doorbell camera footage is powerful evidence. It shows Stevenson committing the act. Without this evidence, prosecution would be more difficult. With it, the state has documentary proof.

However, Stevenson will likely mount a defense. Her attorney might argue:

- Misidentification: The camera doesn't clearly show her face

- Alternative explanations: Maybe the substance wasn't pepper spray, or it came from elsewhere

- Intent: Perhaps she was testing a product or joking, without intent to cause harm (unlikely to succeed but legally possible)

The prosecution has strong evidence, but the case will likely proceed to trial where these defenses can be challenged.

Sentencing and Precedent

If convicted, Stevenson would face sentencing guidelines in Indiana. The sentence would depend on her prior criminal history, the court's assessment of her remorse or lack thereof, and various aggravating or mitigating factors.

For someone with no prior record, a conviction on these charges might result in 2-5 years of prison, depending on the specific sentence imposed. Indiana also allows for suspended sentences or probation, so the actual prison time might be lower.

This case will likely set precedent in Indiana for how food tampering through gig delivery is prosecuted. If Stevenson is convicted, prosecutors in other states will cite this case when pursuing similar charges.

Estimated data shows that battery with moderate injury in Indiana can result in 2-8 years of imprisonment, while consumer product tampering can lead to 2-10 years, highlighting the serious legal consequences of these charges.

Consumer Trust and the Platform's Response

When Door Dash learned of the incident, the company moved quickly to distance itself from Stevenson. She was banned from the platform. Door Dash issued a statement acknowledging the incident and affirming its safety commitment.

But one company statement doesn't restore consumer confidence. The incident raises uncomfortable questions about whether people can safely use food delivery services.

Consumer Behavior Shifts

In the immediate aftermath of high-profile incidents involving gig platforms, consumer behavior often shifts. People become more cautious about ordering from delivery apps. Usage might temporarily decrease. Reviews of the platform on app stores might become more negative.

However, these shifts are typically short-lived. People return to using convenient services relatively quickly, especially if the incident is perceived as an anomaly rather than a systemic problem. The Evansville case, while serious, will likely be perceived as a rare incident involving one bad actor, not as evidence that Door Dash itself is unsafe.

If similar incidents occurred regularly, consumer trust would erode significantly. But isolated incidents, even serious ones, typically don't deter long-term usage patterns.

Liability and Civil Suits

Beyond the criminal case, the victims have grounds to pursue civil litigation against Stevenson personally and potentially against Door Dash. A civil suit would seek damages for:

- Medical expenses: Testing, treatment, or evaluation of pepper spray exposure

- Pain and suffering: Compensation for physical suffering and emotional distress

- Lost wages: Time off work due to the incident

- Punitive damages: Intended to punish egregious behavior and deter future incidents

Suing Door Dash directly would require showing that the company was negligent in hiring or retaining Stevenson. As discussed earlier, this is a high bar to clear. The victims would need to show that Door Dash knew or should have known that Stevenson was dangerous.

However, the legal landscape around platform liability is evolving. California's Proposition 22 and similar legislation in other states have clarified that platforms aren't strictly liable for contractor actions, but they can still be liable for negligence. Future cases might expand platform liability for safety incidents.

The Broader Gig Economy Safety Problem

The Door Dash incident is one example of a broader problem: the gig economy fundamentally changes the relationship between work, worker, customer, and platform in ways that create safety risks.

The Contractor Classification Problem

Gig workers are classified as independent contractors, not employees. This classification has enormous implications for safety. Employees are subject to company training, supervision, and discipline. Contractors are largely autonomous.

The contractor classification allows platforms to maintain the fiction that they're not responsible for worker behavior. In reality, platforms control key aspects of contractor work through algorithms, rating systems, and deactivation. The relationship is one of control without responsibility—which is essentially the definition of an employment relationship, legally speaking.

Several jurisdictions, including California and the EU, have begun reclassifying gig workers as employees or requiring employee-like protections. This would impose greater obligations on platforms to train, monitor, and manage driver behavior.

If Stevenson were classified as a Door Dash employee rather than a contractor, Door Dash would have greater responsibility for her actions and greater incentive to invest in training and monitoring that might have prevented the incident (though, to be fair, no amount of training would have prevented a driver who deliberately chose to commit a crime).

The Volume and Velocity Problem

Door Dash and similar platforms operate at massive scale. There are hundreds of thousands of active drivers, millions of daily deliveries, and countless interactions between drivers and customers. At this volume, even if the percentage of incidents is very small, the absolute number of incidents is significant.

The volume also creates a velocity problem. Incidents move from occurrence to public awareness very quickly. Social media spreads news of food tampering or driver misconduct within hours. One incident can trigger widespread concern.

Platforms struggle to respond at scale. They can ban individual drivers quickly, but implementing system-wide changes to address root causes takes time. By then, public attention has already shifted.

The Profit Motive and Safety Trade-Offs

Ultimately, gig platforms make trade-offs in favor of growth and profit over safety investment. They could implement more rigorous driver vetting, more extensive training, more robust monitoring systems, and more generous driver compensation (which might reduce the economic desperation that motivates misconduct).

But each of these would reduce margins and slow growth. Investors in gig platforms expect rapid expansion and profitability. Safety investments that don't directly prevent catastrophic liability exposure often get deprioritized.

This isn't unique to gig platforms. Most companies make similar trade-offs. But in the gig economy, where workers and customers don't have the protections that traditional employment and commerce provide, the stakes feel higher.

Anonymity and economic desperation are estimated to be the most significant factors influencing driver misconduct in gig work. Estimated data.

What Consumers Can Do: Practical Safety Measures

While the Evansville case is alarming, food delivery remains statistically safe. But there are steps consumers can take to further reduce risks.

Verify Driver Information

When ordering through Door Dash, you can view driver ratings, number of deliveries, and basic profile information. Before accepting a driver assignment, check their rating. Drivers with very low ratings (below 4.5 stars) have received multiple complaints. While one low rating might be unfair, a pattern of low ratings suggests problems.

You can also view a driver's photo. This serves two purposes: it confirms the person at your door is the driver assigned to your order (important for security), and it provides your own verification mechanism.

Monitor the Delivery Process

Door Dash and other platforms show real-time driver location as they approach your address. Watch the progression. If a driver is lingering unusually long or taking odd routes, you can contact customer service.

When the delivery occurs, be present to receive it. Don't rely on the driver leaving it on the porch while you're inside. Open the door, greet the driver, and visually inspect the food before closing the door. If anything looks unusual—the food appears tampered with, containers are damaged, or you see something strange—don't accept the delivery.

Use Security Cameras

If you have a doorbell camera or security system, use it. Record deliveries. This serves as your own documentation and evidence if something goes wrong. In the Evansville case, the family's doorbell camera was crucial to identifying and prosecuting the driver.

Report Suspicious Behavior Immediately

If you notice anything unusual during a delivery—a driver lingering, acting strangely, or doing something suspicious—report it to the platform immediately. Take photos or video if possible. Don't confront the driver directly. Let the platform and, if necessary, law enforcement handle it.

Know Your Recourse Options

If you receive tampered or contaminated food:

- Document everything: Take photos, keep the food and packaging, note your symptoms and times

- Report to the platform: File a detailed report with Door Dash, including all evidence

- Contact local health authorities: Report suspected food tampering to your county health department

- Seek medical evaluation: If you experience symptoms, get medical attention and keep records

- Consult an attorney: If damages are significant, speak with a lawyer about civil remedies

Lessons for Platform Regulation and Industry Standards

The Door Dash incident provides several lessons for how the gig economy might be better regulated.

Standardized Background Check Requirements

Currently, background check standards vary widely across platforms and jurisdictions. A standardized baseline—requirements for what disqualifying offenses are, how recently, and what level of vetting is required—would ensure consistency. This might include requirements for:

- Fingerprint-based background checks (more thorough than name-based checks)

- Quarterly or annual rechecks, not just initial vetting

- Specific disqualifying offenses related to violence, theft, or sexual misconduct

- Reference checks from prior employers or customers

Incident Reporting and Analysis

Platforms could be required to report serious incidents (tampering, violence, theft) to regulatory agencies. This would create a database of incidents, allowing analysts to identify patterns and problem areas. Currently, many serious incidents are handled internally by platforms without external reporting.

Driver Training and Certification

Mandatory food handler certification, already required in many restaurants, could be extended to delivery drivers. This would ensure all drivers have basic food safety knowledge and understand the seriousness of tampering.

Beyond food handling, drivers could receive training on customer safety, de-escalation, and appropriate behavior. This training could be provided through online courses or in-person workshops.

Accountability and Insurance

Platforms could be required to maintain adequate liability insurance covering driver actions. This would incentivize platforms to screen and monitor drivers more carefully, because insurance premiums would increase with incident rates.

Additionally, platforms could be required to maintain an incident fund to compensate victims of driver misconduct, similar to how some industries maintain victim compensation programs.

Labor Classification and Worker Protections

Reclassifying gig workers as employees or quasi-employees, as some jurisdictions are doing, would impose greater obligations on platforms. Employers must train, monitor, and manage their workforce in ways that independent contractors don't. This could include:

- Mandatory background checks and ongoing vetting

- Workplace conduct training

- Supervision and quality monitoring

- Disciplinary procedures

- Workers compensation and benefits

While this would increase platform costs, it might actually reduce the frequency and severity of safety incidents by improving accountability.

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of food delivery safety is unregulated, highlighting gaps in oversight for delivery drivers.

Industry Responses and Self-Regulation Efforts

Platforms haven't waited for regulation. They've begun implementing their own safety measures, though these remain inconsistent and voluntary.

Door Dash's Safety Initiatives

Door Dash has rolled out several safety features in recent years:

- Enhanced background checks through third-party background check companies

- Delivery verification with photos to reduce fraudulent deliveries

- Driver ratings and reviews allowing customers to flag problematic drivers

- Support for reporting incidents through in-app mechanisms

- Partnerships with local law enforcement in some markets

These measures are positive steps, but they're reactive rather than proactive. They address problems after they occur rather than preventing them.

Industry Consortium Efforts

Some delivery platforms have joined industry consortiums to establish voluntary standards. These might include commitments to background checking, customer service responsiveness, and incident reporting.

However, voluntary standards lack enforcement mechanisms. A platform can commit to a standard and then ignore it, with minimal consequences beyond reputation damage. Without regulatory teeth, self-regulation often underperforms.

Third-Party Certification

Some independent organizations have begun certifying delivery services that meet certain safety standards. These certifications are voluntary and don't cover all platforms, but they provide consumers with additional information beyond platform marketing claims.

The Psychology of Trust in Digital Transactions

Food delivery apps succeed because they've managed to build trust in a situation where trust is genuinely difficult. You're giving your address to a stranger, trusting them with your food, and relying on algorithms to vet them.

How Platforms Build Trust

Platforms use several mechanisms to build consumer trust:

- Transparency: Showing driver ratings, profiles, and real-time location

- Accountability: Allowing customers to rate drivers and report incidents

- Recourse: Offering refunds or replacements for poor deliveries

- Scale: Leveraging the fact that millions of safe deliveries create statistical confidence

- Brand: Door Dash, Uber Eats, and Grubhub are established brands with reputations to protect

How Incidents Damage Trust

A single serious incident—like deliberate food tampering—damages trust disproportionately because it suggests the transparency and accountability mechanisms didn't work. If a driver can spray pepper spray on food and it takes weeks for the incident to become criminal charges, it suggests the system has gaps.

The incident makes the implicit trust explicit and questionable. Most people use delivery apps without consciously thinking about the trust relationship. An incident like this forces them to think about it, and they often conclude the risk is greater than they previously realized.

Recovery and Confidence Restoration

For platforms to restore confidence after an incident, they typically:

- Acknowledge the incident: Door Dash quickly confirmed the case and stated it was unacceptable

- Take decisive action: Banning the driver shows responsiveness

- Emphasize systems: Describing background checks, verification systems, and reporting mechanisms reassures customers that processes exist

- Frame as anomaly: Contextualizing the incident as rare helps prevent people from generalizing risk

If platforms respond poorly—denying incidents, defending problematic drivers, or failing to take action—trust erodes rapidly and recovery becomes difficult.

Door Dash's response to the Evansville incident appears to follow the standard playbook: quick action, clear messaging, and emphasis on system safeguards. This should help maintain consumer confidence in the platform.

Comparative Analysis: How Other Gig Platforms Handle Safety

Door Dash isn't unique in facing safety incidents. Uber, Lyft, Grubhub, Instacart, and other gig platforms have all dealt with driver misconduct and safety issues.

Uber's Safety Evolution

Uber has been at the center of numerous safety controversies—driver sexual assault, driver violence against passengers, and customer harassment by drivers. These incidents forced Uber to invest heavily in safety features:

- Two-way ratings: Both drivers and passengers rate each other

- Safety features: In-app emergency buttons, ride history sharing with trusted contacts, and audio recording options

- Driver vetting: Enhanced background checks and ongoing monitoring

- Deactivation protocols: Clear processes for removing drivers who violate safety standards

Uber's safety investments were largely forced by regulatory pressure and litigation rather than chosen voluntarily. The company now emphasizes safety in marketing, but critics argue the investments came too late and remain insufficient.

Instacart's Shopper Management

Instacart faces different safety issues because shoppers, rather than drivers, select and purchase items for customers. Safety concerns include:

- Refund fraud: Shoppers claiming to purchase items but keeping the money

- Substitution fraud: Shoppers substituting cheaper items for purchased ones

- Delivery theft: Shoppers stealing items or leaving items behind

Instacart's response includes background checks, customer ratings of shoppers, and item verification systems. However, the company has faced criticism for not being aggressive enough in removing problematic shoppers.

Lyft's Approach

Lyft, operating as a ride-sharing service, faces similar safety issues to Uber but has taken a somewhat different approach:

- Emphasizing driver quality: Lyft has made higher-quality driver standards a marketing differentiator, at least rhetorically

- Community feedback: Emphasizing Lyft's community-focused culture and values

- Reporting mechanisms: Making it easy for passengers to report inappropriate behavior

Whether Lyft's safety standards are actually meaningfully different from Uber's is debatable. Both face similar incidents and criticisms.

Grubhub and Food Delivery Competitors

Grubhub, operating in the same market as Door Dash, faces similar food safety and driver conduct issues. The company's public disclosures about safety measures are limited, which itself may reflect a lack of robust safety investment.

Competition in food delivery is intense, with thin margins. All major platforms face pressure to minimize costs and focus on growth over safety investments. This creates a race-to-the-bottom dynamic where platforms avoid unilateral safety investments that would increase costs without creating competitive advantage.

Future of Gig Economy Safety: Emerging Technologies and Approaches

As the gig economy matures, new technologies and approaches to safety are emerging.

AI-Powered Monitoring and Prediction

Machine learning algorithms can analyze driver behavior patterns to predict which drivers are likely to engage in misconduct. These systems can flag:

- Unusual patterns: Drivers who frequently work unusual hours, take odd routes, or spend excessive time at deliveries

- Customer complaints: Drivers with increasing complaint patterns or specific complaint types

- Behavioral changes: Drivers whose behavior suddenly shifts in concerning ways

These systems aren't perfect—they can flag drivers unfairly and might perpetuate biases in the training data—but they can identify concerning patterns that warrant human review.

Door Dash, Uber, and other platforms almost certainly employ some form of behavioral monitoring using machine learning, though details aren't publicly disclosed.

Biometric Verification

Facial recognition and other biometric technologies could verify that the person accepting a delivery is the assigned driver. This would prevent someone else from using a driver's account or misrepresenting themselves.

However, biometric verification raises privacy concerns. Collecting and storing facial recognition data creates security risks if that data is breached. Additionally, some jurisdictions have restricted facial recognition by private companies.

Tamper-Evident Packaging

High-tech packaging that shows visible evidence if opened or tampered with could prevent contamination. Some restaurants already use tamper-evident bags, but standardization across all platforms would improve safety.

Temperature sensors in packaging could also alert customers if food has been exposed to unsafe temperatures during delivery, providing another verification mechanism.

Blockchain and Transparency

Blockchain technology could create immutable records of each delivery—from restaurant to driver to customer. Each handoff would be recorded and timestamped. This wouldn't prevent misconduct, but it would make tracing contamination easier and would create clear accountability.

Implementing blockchain across platforms would require significant technical coordination and investment, so adoption is unlikely in the near term.

Drone Delivery

Amazon and others are experimenting with drone delivery, which would eliminate the human factor in delivery (at least for packages, though food delivery would require specialized drones). Autonomous delivery would prevent driver misconduct but would create other safety and regulatory challenges.

Wide-scale drone delivery remains years away and faces significant regulatory hurdles.

The Role of Regulation: What Government Should Do

Currently, gig economy regulation is fragmented and often absent. State and local governments have taken varying approaches, but federal regulation is minimal.

Federal Legislation Possibilities

Congress could pass legislation establishing baseline standards for gig platforms:

- Food Safety and Delivery Standards: Requirements for insulated containers, temperature monitoring, and driver training

- Background Check Standards: Minimum standards for what checks platforms must conduct

- Incident Reporting: Requirements to report serious incidents to federal agencies

- Driver Classification: Clarification or reclassification of contractor vs. employee status

- Consumer Protections: Rights to refunds, recourse, and dispute resolution

Such legislation would level the playing field among platforms and ensure consistent consumer protections regardless of location.

However, federal legislation is difficult to pass. Platforms lobby against regulation, and there's disagreement about what's appropriate. Additionally, the gig economy is evolving rapidly, making legislation a moving target.

State-Level Approaches

Many states are taking action independently:

- California reclassified many gig workers as employees under Proposition 22 (though the law has been subject to ballot challenges and legal disputes)

- New York has implemented specific regulations for delivery platform wages and working conditions

- Illinois has required background check standards and incident reporting

These state-level approaches create patchwork regulation that's difficult for national platforms to navigate. However, they also allow experimentation and customization to local conditions.

Local Ordinances

Cities and counties have begun implementing local ordinances governing food delivery:

- Delivery fees: Caps on what platforms can charge or what restaurants must pay

- Worker protections: Minimum standards for driver compensation and safety

- Health codes: Extensions of restaurant health codes to delivery services

Local regulation is often more responsive to community concerns but can be difficult for platforms operating across multiple jurisdictions.

The Bigger Picture: Gig Economy Structure and Accountability

The Door Dash food tampering case is a symptom of deeper structural issues in the gig economy.

The Contractor Model's Limits

The contractor classification was designed for occasional freelance work—a photographer hired for a wedding, a plumber hired for a repair. It doesn't translate well to systematic, ongoing work with significant economic dependence.

When someone works 30+ hours per week for a single platform, with that platform controlling pricing and work availability, the relationship looks more like employment than freelancing. The contractor classification allows platforms to avoid the obligations that come with employment while maintaining significant control over workers.

This creates a structural accountability problem. Platforms control enough to influence worker behavior but deny responsibility for it. Workers are subject to deactivation and algorithmic management without the protections employees receive.

The Information Asymmetry

Platforms have far more information about drivers, customers, and incidents than either drivers or customers have. Platforms know the frequency of complaints, the nature of incidents, the drivers with high risk, and the patterns of misconduct.

But this information is rarely shared. Drivers don't know how they compare to peers or whether customers have complained about them. Customers don't know the actual safety record of drivers or whether their particular driver has had past issues.

Regulation could require greater transparency, but platforms argue that transparency creates liability risks. A driver who knows they have multiple complaints might contest them more aggressively. A customer who sees that a driver has received complaints might refuse the assignment, reducing platform efficiency.

The information asymmetry favors platforms, but it arguably disadvantages public safety.

The Fragmentation Problem

With dozens of gig platforms, hundreds of thousands of drivers, and millions of daily transactions, creating coherent, enforced safety standards is challenging. A platform can implement safety features and claim commitment to safety while knowing that enforcement is light and accountability is low.

Platforms compete on convenience and price, not safety. If one platform implemented significantly more rigorous safety measures, costs would increase, prices would have to rise, and the platform would lose market share to competitors with lower standards.

This race-to-the-bottom dynamic is common in unregulated industries. It can only be broken by regulation that imposes standards on all competitors simultaneously.

Lessons from Other Industries: Taxi Regulation and Air Travel Safety

The gig economy isn't the first industry to grapple with safety and accountability questions. Examining how other industries addressed similar issues provides lessons.

Taxi and Limousine Regulation

For decades, taxi services were heavily regulated. Drivers required medallions, background checks, and insurance. Pricing was regulated. Service standards were enforced. This regulation was criticized for limiting competition and innovation.

When ridesharing platforms like Uber and Lyft emerged, they operated initially in regulatory gray areas, arguing that smartphone-based dispatch was fundamentally different from traditional taxi services. Over time, regulators caught up. Most jurisdictions now require ridesharing drivers to have background checks, insurance, and periodic vehicle inspections.

The lesson: new business models often operate in regulatory gaps before rules catch up. Once rules do catch up, they tend to be somewhere between the old industry standard and the new industry's preferred light-touch approach.

Aviation Safety Standards

Commercial aviation has strict safety standards—pilot training, aircraft maintenance, air traffic control protocols. These standards developed over decades, largely in response to accidents that revealed gaps.

The airline industry is heavily regulated, and safety is prioritized over cost efficiency. Airlines could reduce costs by cutting maintenance or training, but they don't, because the regulatory framework and consumer expectations don't permit it.

The lesson: stringent safety standards often require regulatory mandate and can coexist with profitable business models. Industries resist safety regulation until forced by accidents, litigation, or public pressure.

Food Safety Evolution

Food safety regulation evolved significantly after the 1906 publication of Upton Sinclair's "The Jungle," which exposed horrific conditions in meat processing plants. The resulting Pure Food and Drug Act created the FDA and established baseline food safety standards.

Since then, food safety has continued evolving, with regulations becoming more stringent after each major incident (contaminated spinach, salmonella in peanut butter, etc.).

The lesson: food safety is often taken seriously by regulators because the consequences of failure are visible and tragic. Dead or seriously ill consumers create political pressure for stronger standards.

In the gig delivery context, a single incident of deliberate food tampering might eventually trigger stronger regulatory responses, especially if similar incidents recur.

Conclusion: Risk, Trust, and the Path Forward

The Door Dash food tampering incident in Evansville, Indiana illustrates the complex challenges of safety in the gig economy. A driver allegedly deliberately contaminated customers' food with pepper spray, causing physical harm. This wasn't a mistake or negligence—it was a deliberate, criminal act.

Door Dash responded quickly by banning the driver, and law enforcement prosecuted the case. From a platform perspective, the company did what reasonable actors would do. But the incident raises uncomfortable questions about whether the systems platforms have implemented are sufficient to prevent such acts, and whether they should be doing more.

The gig economy's fundamental structure—independent contractors, minimal oversight, algorithmic management at scale—creates safety challenges that traditional employment relationships don't. When someone is your employee, you train them, supervise them, and hold them accountable. When someone is an independent contractor, you maintain the fiction of minimal responsibility while controlling many aspects of their work.

Moving forward, several paths are possible:

Path 1: Regulatory Tightening: Government could impose stricter standards on platforms, requiring more rigorous background checks, driver training, monitoring, and incident reporting. This would increase platform costs but would likely prevent some incidents and improve accountability.

Path 2: Worker Reclassification: If gig workers are reclassified as employees or quasi-employees, platforms would have greater responsibility and incentive to invest in training and monitoring. This would significantly increase platform costs and likely raise consumer prices.

Path 3: Technological Solutions: Platforms could invest in AI-powered monitoring, biometric verification, tamper-evident packaging, and other technologies to reduce safety risks. These solutions are costly but might be more acceptable to platforms than regulatory mandates.

Path 4: Market Evolution: As the market matures, consumers might increasingly demand safety and be willing to pay for it. Platforms that invest in safety could differentiate on that basis, creating competitive advantage for safety-conscious platforms.

Most likely, we'll see a combination of these paths. Regulation will impose some baseline standards. Platforms will implement some technological solutions. Market evolution will drive some improvements. But the gig economy will likely remain a lower-friction, lower-oversight system than traditional employment or heavily regulated industries.

For consumers, the Evansville case is a reminder that while food delivery is statistically safe, risk exists. Taking precautions—monitoring deliveries, using security cameras, verifying driver identity, and reporting suspicious behavior—can further reduce already-low risks.

For platforms, the case illustrates that safety investments aren't just about liability management. They're about maintaining customer trust, which is essential for business success. A platform that allows serious incidents to occur without robust response faces reputation damage that can last years.

For regulators, the case demonstrates the gaps in current oversight of the gig economy. Whether those gaps warrant regulatory intervention remains a question, but the case provides evidence that self-regulation alone may be insufficient.

Ultimately, the Door Dash incident is one criminal act by one bad actor. It doesn't define the gig economy, which serves millions of consumers safely every day. But it does illuminate the vulnerabilities in a system that prioritizes speed and convenience over comprehensive safety systems. Whether those vulnerabilities represent acceptable trade-offs or problematic risks depends on one's perspective on innovation, regulation, and the role of business in managing risk.

The incident will likely influence policy discussions, inspire some platform safety improvements, and potentially serve as precedent in future prosecutions. But it's unlikely to fundamentally transform the gig economy structure anytime soon. The economic incentives favoring the current model are too strong, and the political will for heavy regulation remains uncertain.

What we'll probably see is incremental change: better background checks here, more robust incident reporting there, improved customer communication elsewhere. Progress, but not transformation. That's the typical pace of change in large, profitable industries facing safety concerns—gradual, insufficient for critics, faster than companies prefer.

The next serious incident will renew pressure for stronger action. But in the intervals between incidents, the pressure wanes and business continues largely as before. That's not unique to the gig economy, but it does suggest that substantial safety improvements will require either catastrophic incidents that shock the public, or regulatory intervention that forces platforms to invest whether they prefer to or not.

Until one of those occurs, we're likely in a steady state: mostly safe deliveries, occasional incidents, platform bans for bad actors, criminal prosecutions for serious crimes, and a system that works well enough for most people most of the time, while remaining imperfect for all.

FAQ

What exactly happened in the Door Dash incident?

A Door Dash driver in Evansville, Indiana allegedly sprayed customers' food with pepper spray after dropping it off at their home. The family who ordered the food experienced vomiting, burning sensations in their mouths, noses, throats, and stomachs. Doorbell camera footage showed the driver pulling an aerosol can from her keychain and spraying the delivery bag. She was later identified as Kourtney Stevenson and charged with battery resulting in a moderate injury and consumer product tampering, both felonies in Indiana.

Why did the driver allegedly spray the food?

Stevenson claimed she used pepper spray to kill a spider on the food. However, the Vanderburgh County Sheriff's Office noted that outdoor spiders in Indiana don't remain active when temperatures drop to 35 degrees Fahrenheit, which was the temperature that evening. This explanation undermined her defense and supported the prosecution's theory that she deliberately contaminated the food.

What charges is Stevenson facing?

She faces two felony charges: battery resulting in a moderate injury and consumer product tampering. Battery with moderate injury in Indiana carries potential prison sentences ranging from 2-8 years, depending on the specific circumstances and the judge's sentencing discretion. Consumer product tampering charges also carry significant penalties. She was arrested and is awaiting extradition from Kentucky to Indiana for trial.

How did doorbell camera footage help solve the case?

The victims' security doorbell camera recorded the delivery and clearly showed Stevenson pulling an aerosol can from her keychain and spraying the delivery bag immediately after dropping it off. This documentary evidence was crucial, providing visual proof of the act itself. Without this footage, prosecution would be considerably more difficult, as the case would rely more heavily on circumstantial evidence and the victims' testimony about their symptoms.

What did Door Dash do in response?

Door Dash quickly banned Stevenson from the platform after learning about the incident. The company issued a statement acknowledging that the behavior was unacceptable and affirming its commitment to customer safety. However, the company emphasized that it conducts background checks and uses verification systems, framing this as an isolated incident rather than a systemic problem with the platform itself.

How did detectives identify the driver if the order was supposedly anonymous?

Door Dash maintains detailed records of all deliveries, including driver identity, address, time, and order details. When the victims reported the incident to law enforcement and provided the Door Dash order information, detectives were able to query the company's database to identify the assigned driver. This illustrates why platform accountability can actually be quite straightforward—the companies maintain excellent records of who made what delivery when.

Could the customers sue Door Dash for the incident?

The victims could potentially pursue a civil suit against Door Dash to recover damages for medical costs, pain and suffering, and lost wages. However, establishing that Door Dash itself was negligent would be difficult. The company would likely argue that it conducted a background check, implemented verification systems, and immediately deactivated the driver upon learning of the incident. To succeed, the victims would need to prove that Door Dash knew or should have known that Stevenson was dangerous. Given that she apparently had no prior criminal history, this burden would be hard to meet.

What food safety regulations govern third-party delivery?

Regulation is fragmented. The FDA has issued guidance on food delivery services but no binding requirements exist at the federal level. State and local health departments regulate food establishments but don't have clear jurisdiction over independent delivery drivers. Criminal law prevents tampering with consumer products, but civil food safety regulations don't clearly apply to gig delivery. This regulatory gap means food delivery operates in a space where criminal law addresses deliberate tampering but food safety codes don't comprehensively regulate driver behavior.

How common is food tampering in delivery services?

Severe intentional tampering appears rare. Most delivery incidents involve theft, forgotten items, or poor food quality due to temperature exposure—not deliberate contamination. The rarity of serious tampering incidents like this one is one reason platforms don't invest as heavily in prevention as they might. From a purely statistical perspective, the risk to any individual customer is extremely low. However, when incidents do occur, they're serious and can cause significant harm, which is why they merit attention.

What can consumers do to protect themselves from food tampering?

Consumers can verify driver information before accepting delivery, monitor the real-time delivery process through the app, install security cameras to record deliveries, visually inspect food before accepting it, and report any suspicious behavior immediately to the platform and law enforcement if necessary. While food tampering is rare, these precautions further minimize an already-low risk. Most importantly, being present to receive the delivery (rather than having it left unattended) allows you to observe the driver and inspect the food immediately.

What regulatory changes might prevent future incidents?

Potential regulatory changes include mandatory food handler certification for delivery drivers, standardized background check requirements, mandatory incident reporting to health departments, temperature monitoring for deliveries, and potentially reclassification of gig workers as employees rather than independent contractors. However, each of these would increase platform costs. Without regulatory mandate, platforms have limited incentive to implement such measures unilaterally, as it would increase their costs while competitors could maintain lower costs with less stringent safeguards.

Key Takeaways

- A Door Dash driver allegedly sprayed customers' food with pepper spray, causing serious physical harm and resulting in felony charges for battery and product tampering

- The incident reveals vulnerabilities in gig platform safety systems, including contractor classification that limits platform responsibility

- Food delivery regulation is fragmented, with no comprehensive federal standards governing driver safety or food handling practices

- While food tampering incidents are statistically rare, the gig economy's scale means absolute incident numbers are significant

- Platforms make conscious trade-offs favoring convenience and profit growth over comprehensive safety investment

- Consumer vigilance, including doorbell cameras and delivery monitoring, can further reduce already-low risks

- Regulatory reform at state and federal levels could impose stronger standards, but faces resistance from platforms and political obstacles

- The case provides precedent for criminal prosecution of driver misconduct but doesn't address underlying structural safety challenges in the gig economy

- Moving forward, a combination of regulation, technological solutions, and market evolution will likely drive incremental safety improvements

- For most consumers, food delivery remains safe, but the Evansville case demonstrates that risk exists and vigilance is warranted

Related Articles

- Best IT Management Software 2025: Complete Guide & Alternatives

- Best Dictation & Speech-to-Text Software [2026]

- Obsidian vs. Notion: Complete Comparison [2025]

- Best Free Project Management Software [2026]

- Best Time Blocking Apps & Tools for Productivity [2026]

- How to Type an Em Dash on Mac or Windows [2025]

![DoorDash Food Tampering Case: Gig Economy Safety Crisis [2025]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/doordash.jpg?resize=1200,798)