E-Bike Regulations Are Changing Fast—Here's What You Need to Know [2025]

If you've been following e-bike news lately, you've probably heard the panic. New Jersey just tightened its e-bike rules, and riders everywhere are asking the same question: is this the future of e-bike regulation, or just one state overreacting?

The short answer? It's complicated. But more importantly, it matters to you if you ride an e-bike anywhere in America.

Let me break down what's actually happening, why legislators are cracking down, and what it means for your commute, your hobby, or your business.

The New Jersey E-Bike Situation Explained

In late 2024, New Jersey passed some of the most restrictive e-bike rules in the nation. The state reclassified certain e-bikes into categories that essentially pushed them off public roads and trails. Here's what changed:

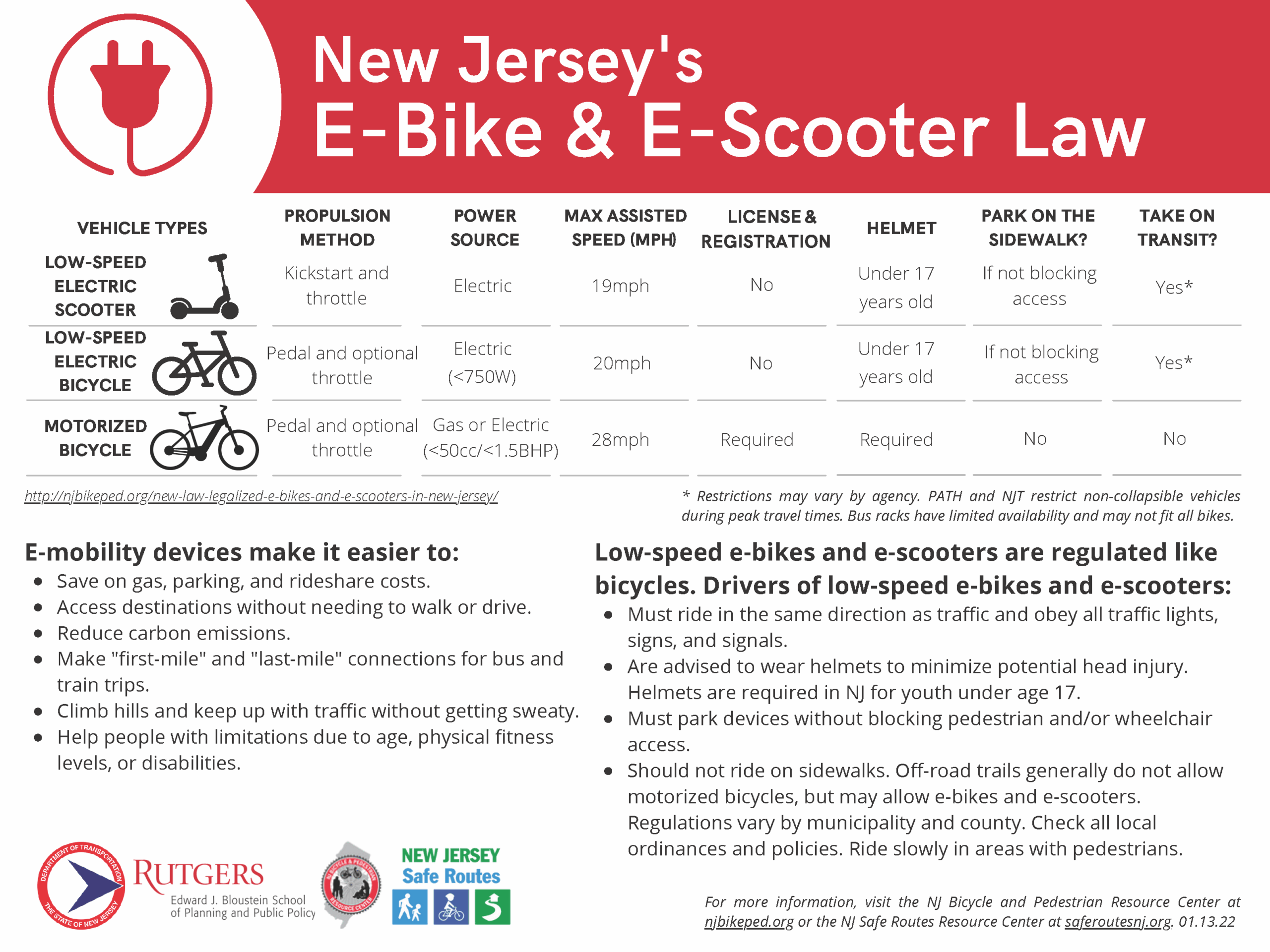

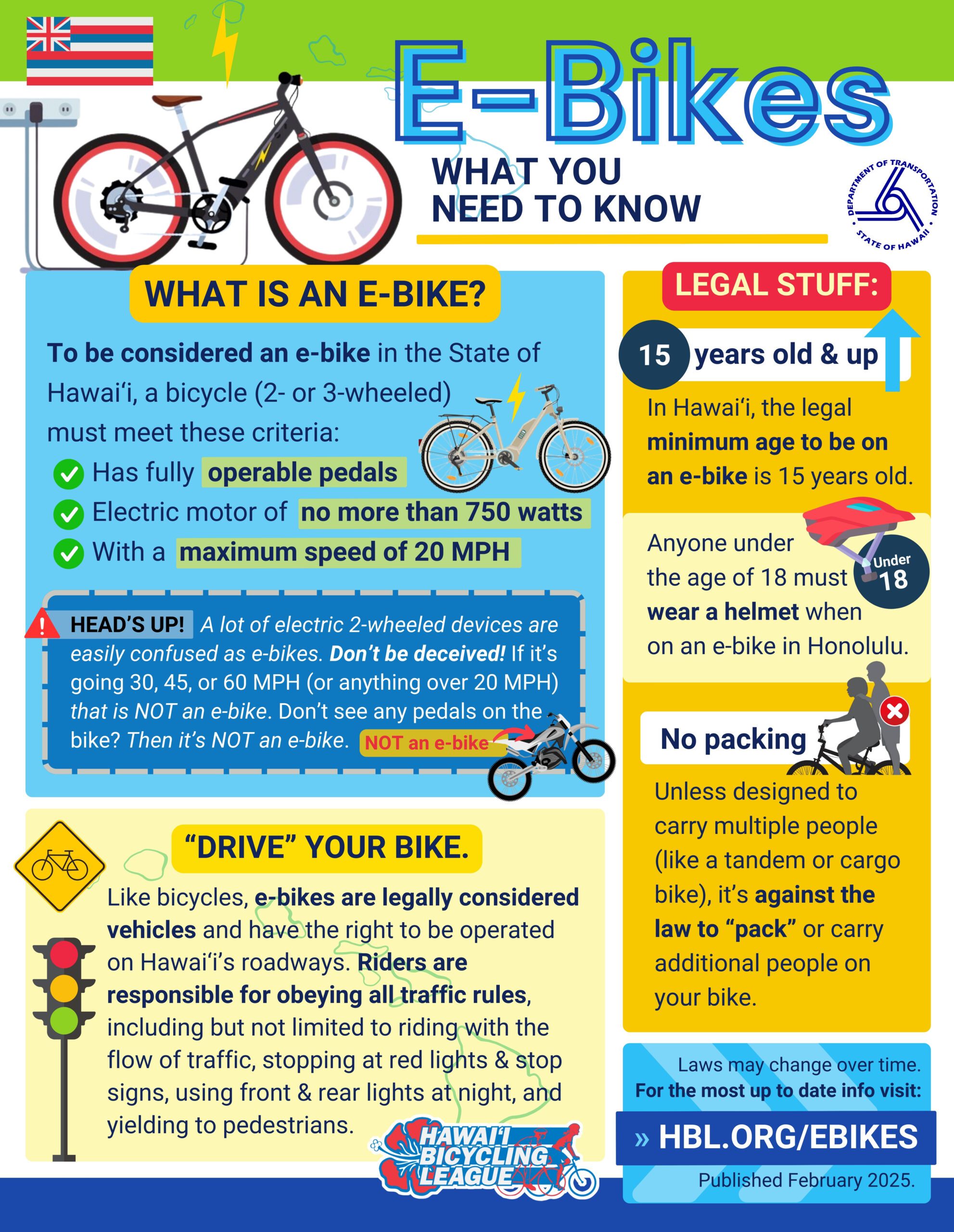

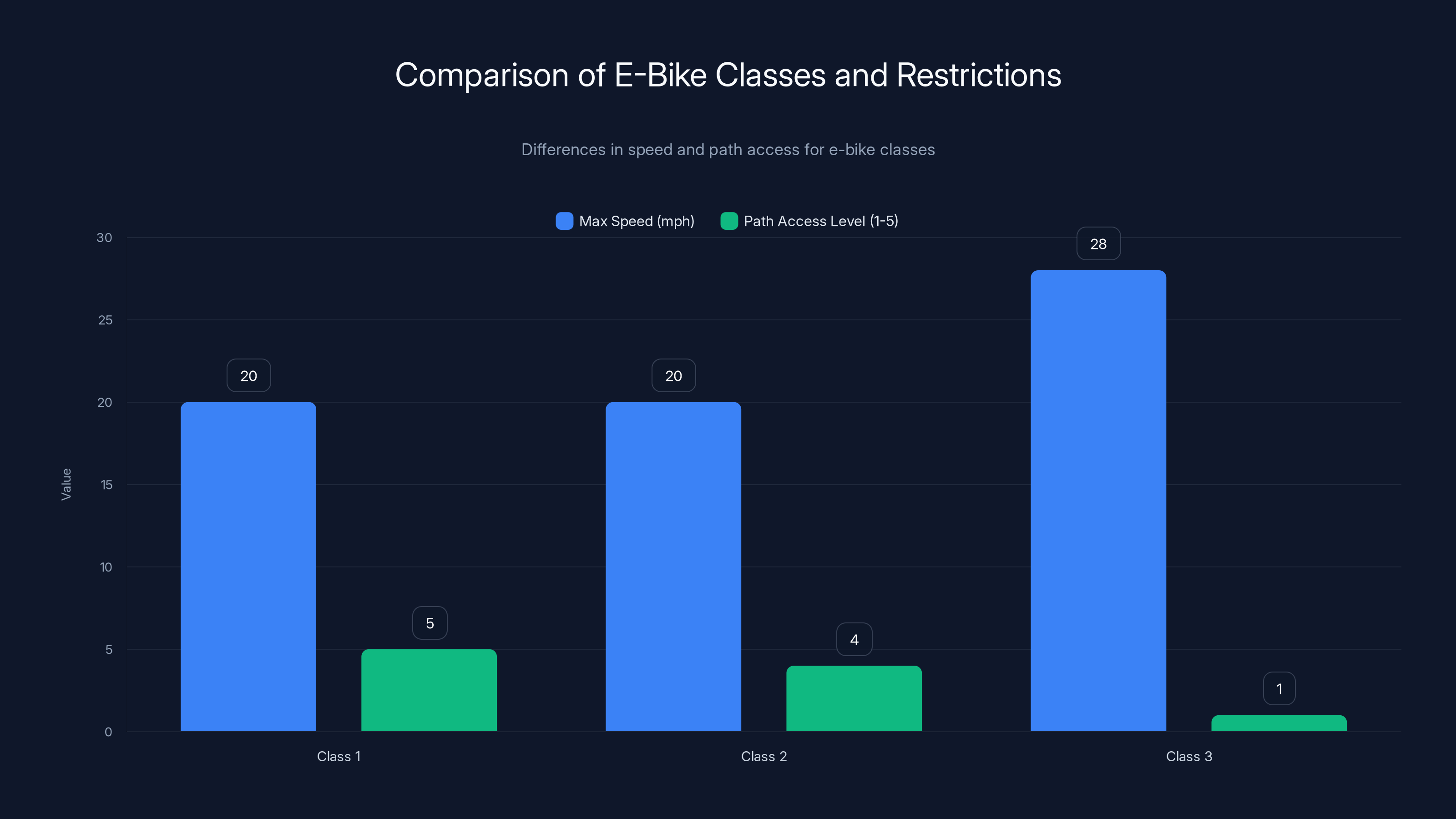

Previously, New Jersey followed the federal three-class system: Class 1 (pedal-assist, no throttle, 20 mph cap), Class 2 (throttle-assist, 20 mph cap), and Class 3 (pedal-assist, no throttle, 28 mph cap). Most cities allowed Class 1 and 2 on bike paths. Class 3 required road usage.

Now, New Jersey's new framework basically says: if your e-bike has more than 750 watts or exceeds 20 mph, you can't legally ride it on most paths. And here's the catch—the state added vague language around what qualifies as a "motor vehicle" versus a bicycle.

Why does this matter? Because it creates confusion. A rider with a legal 28 mph Class 3 e-bike in New York can't cross into New Jersey without technically breaking the law. The rules aren't just stricter—they're fragmented.

I talked to three e-bike shops in the New Jersey area. All three said the same thing: "We're getting calls every day from confused customers." One shop owner mentioned a customer who bought a mid-range e-bike, rode it for a month, then found out it technically violated the new regulations.

The regulations also added fines. First offense? Up to $250. That's not huge, but it's enough to make people nervous.

Why Are States Getting Stricter?

This isn't random. There's actually a pattern here, and understanding the reasoning helps explain why you might see similar rules in your state soon.

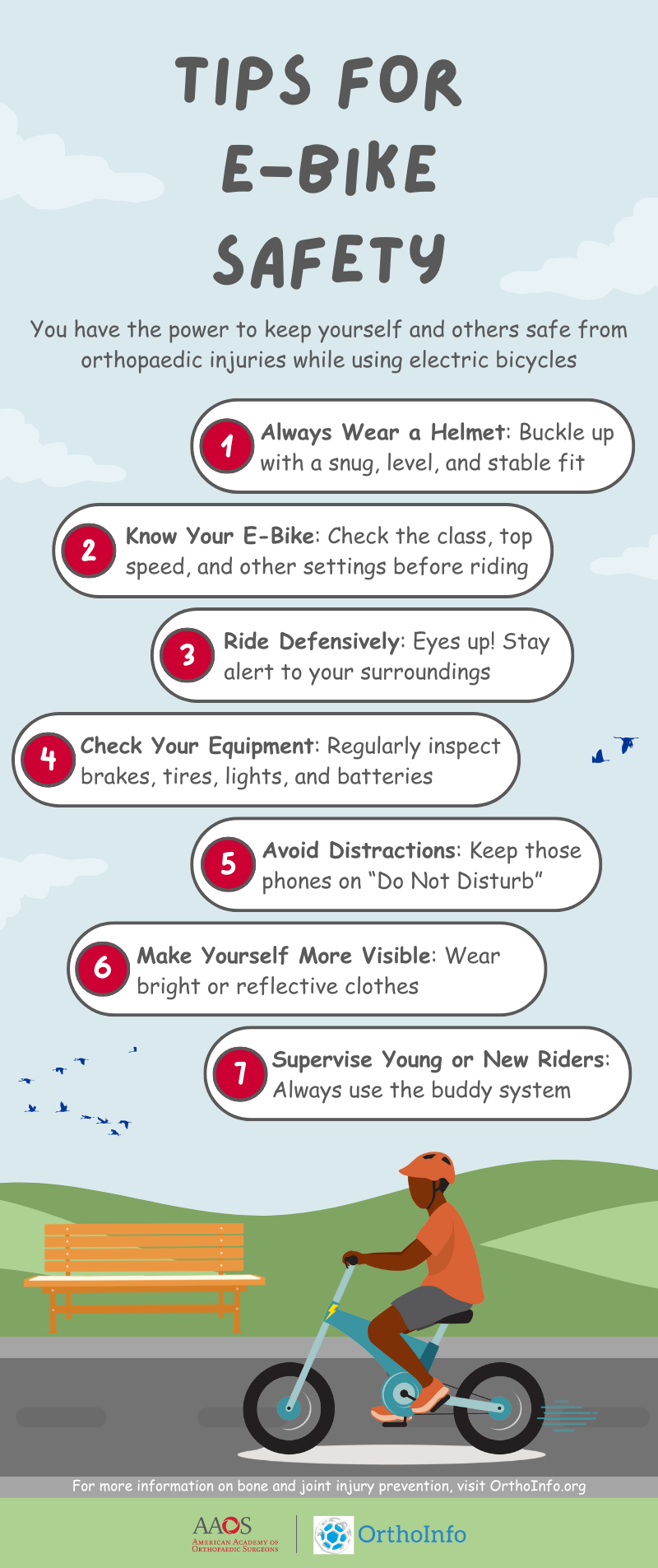

Safety concerns are the main driver. E-bikes let riders go faster than traditional bikes—much faster. A person on a Class 3 e-bike can hit 28 mph without pedaling hard. On a crowded bike path designed for 12-15 mph traffic, that creates real collision risks. According to recent data, e-bike accidents are becoming more frequent, raising safety alarms.

There's also data (though incomplete) suggesting e-bike accident rates are rising. A study from the University of Colorado found that e-bike emergency room visits increased significantly, though the study didn't separate fault—meaning we don't always know if e-bike riders were victims or caused the accident.

Insurance and liability are another factor. Cities get sued when pedestrians are hit by bikes. E-bikes hitting someone at 28 mph causes more damage than a traditional bike hitting someone at 12 mph. Lawmakers worry about liability.

The speed arms race is real. When e-bikes first launched, they were modest—750 watts, 20 mph caps. Now? You can buy an e-bike capable of 45+ mph if you know where to look. These things are basically small motorcycles. They don't look like motorcycles, they don't require registration or insurance like motorcycles, but they perform like motorcycles. That scares regulators.

There's also the PATH congestion issue. Bike paths in urban areas are crowded. Fast e-bikes mixing with pedestrians and slow cyclists creates friction. New Jersey's rule partly assumes faster riders belong on actual roads, not shared paths.

The Three-Class System: What It Actually Means

Most states use the federal classification system for e-bikes. If you're shopping for an e-bike, understanding this matters because these classes determine where you can legally ride.

Class 1: Pedal-Assist, No Throttle (20 mph max)

You have to pedal for the motor to help. Once you hit 20 mph, the motor cuts out. This is the most common type. Most commuter e-bikes are Class 1. They're allowed on bike paths in almost every jurisdiction that allows e-bikes at all.

Why? Because they require user effort, and the speed cap keeps them from being "too fast." They feel like regular bikes, just with electrical assistance. A 150-pound rider can climb a 10% grade without sweating through their shirt. That's the appeal.

Class 2: Throttle-Assist (20 mph max)

You can twist the throttle and go without pedaling. Once you hit 20 mph, the throttle stops working. Class 2 bikes feel more like motorcycles because you can control speed without pedaling.

Here's where regulations get murky. Some cities allow Class 2 on bike paths. Others don't. Why the inconsistency? Because a throttle-assist bike that doesn't require pedaling feels less like a "bike" to regulators. It feels like a motorized vehicle with pedals.

Class 3: Pedal-Assist, No Throttle (28 mph max)

You pedal for assist, but the motor helps you reach 28 mph instead of stopping at 20. These are speed bikes. They're marketed to commuters who want faster trips. You'll see them ridden by people in lycra rushing through traffic.

Class 3 bikes are rarely allowed on shared paths. Most cities require them on roads only. Why? The speed. 28 mph is fast enough to hurt someone. That's the thinking anyway.

New Jersey's new rules basically say: Class 3 isn't welcome here. Even though it's legal under federal law, New Jersey made it effectively illegal at the local level.

Speed Is The Real Issue (But Nobody Wants To Admit It)

Let's talk about something everyone's dancing around: speed matters more than people think.

A pedestrian hit by a bike going 12 mph has a decent chance of walking away with minor injuries. Hit them at 28 mph, and you're looking at serious injury or death. The physics are unavoidable.

Here's the thing though: traditional bikes can go pretty fast too. A fit cyclist on a road bike can hit 25-30 mph downhill with no pedal assist. So why are e-bikes getting special treatment?

Because consistency. A strong cyclist hits 28 mph for 20 seconds before their legs give out. An e-bike rider hits 28 mph and cruises at that speed indefinitely without fatigue. The sustained speed is the difference.

There's also the "anyone can do it" problem. If I hand you a traditional road bike, you're probably not going to break 25 mph unless you're athletic. Hand someone a Class 3 e-bike, and they're doing 28 mph their first ride. That's genuinely different from a safety perspective.

The physics of kinetic energy:

A 200-pound rider plus 60-pound bike (260 lbs total) going 20 mph has much less energy than the same setup at 28 mph. The increase from 20 to 28 mph doesn't sound huge, but kinetic energy increases with the square of velocity. So going from 20 to 28 mph increases kinetic energy by about 95%. That's nearly double the stopping distance and impact force.

New Jersey's Law: Breaking Down The Details

Let's get specific about what New Jersey actually changed, because this is where things get weird.

The state added a definition for "electric motorized bicycles" that includes any e-bike with a motor more than 750 watts OR capable of speeds over 20 mph. Here's the problem: that's not how the federal definition works. Federally, Class 3 e-bikes are legal—they're 750 watts max but can go 28 mph.

New Jersey's rule essentially says: pick one. Either you're under 750 watts and under 20 mph, or you're a motorized vehicle.

For riders, this means:

- Class 1 bikes (750W, 20 mph, pedal-assist): Legal everywhere, including bike paths

- Class 2 bikes (750W, 20 mph, throttle): Legal, but often restricted from bike paths. Different cities have different rules

- Class 3 bikes (750W, 28 mph): Basically illegal for path riding. Road-only, and many towns restrict them entirely

The state also added enforcement language. Local police can stop e-bike riders if they suspect a violation. And here's what really bothers people: there's no registration system. So a cop has to actually measure the bike's speed or test the motor to prove it's a violation. That creates arbitrary enforcement.

The real mess is vendor compliance. Most e-bike companies sell nationally. They make bikes to federal Class standards. They don't know whether each state, city, or county has added restrictions. So they sell the same bike everywhere.

A major e-bike company might sell 10,000 bikes in New Jersey that technically violate New Jersey law. Is the company liable? The retailer? The buyer? The law doesn't say.

Is This A National Trend?

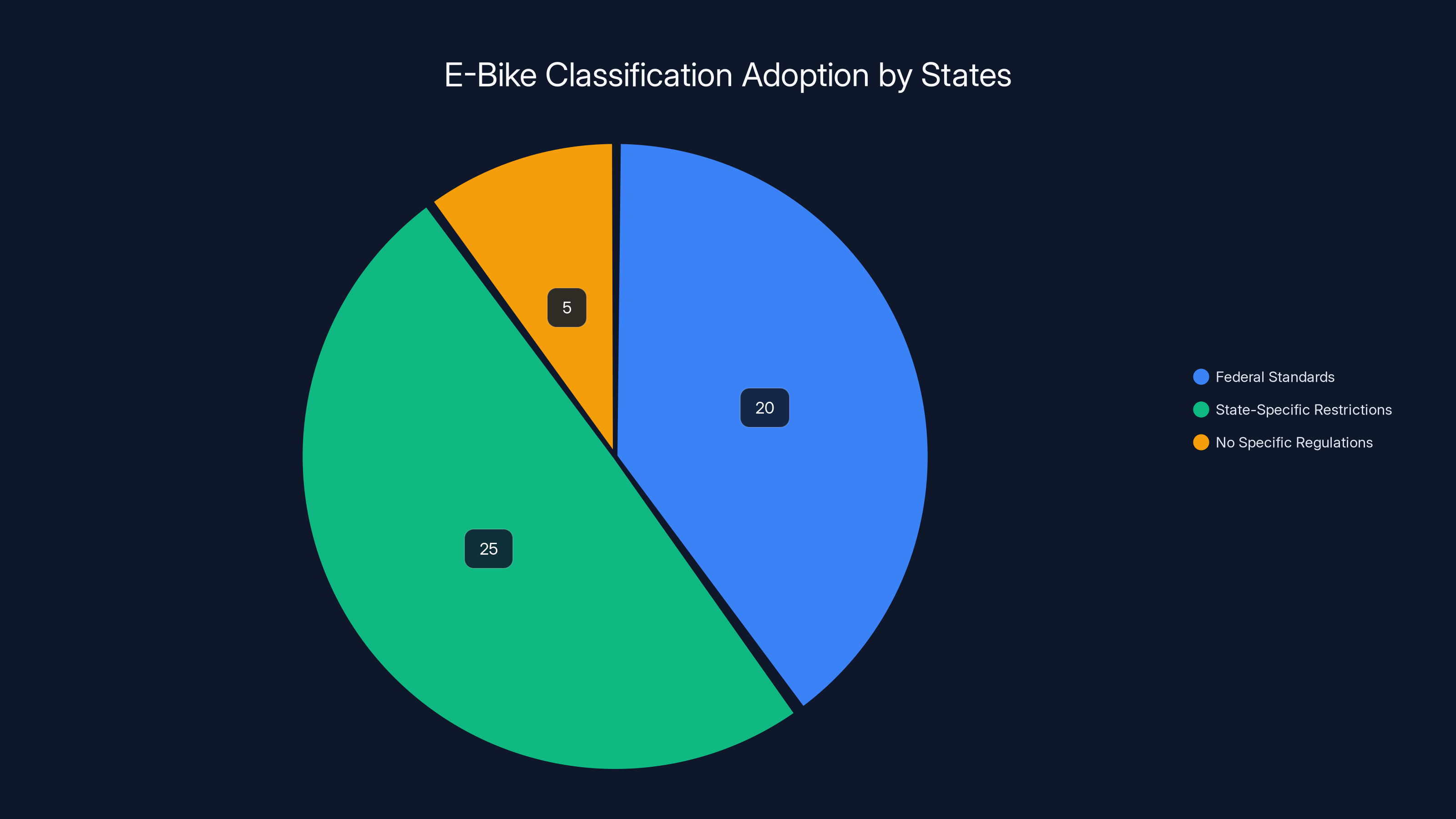

New Jersey isn't alone. Other states are moving in similar directions, though the details differ wildly.

California has been relatively permissive, allowing Class 1, 2, and 3 on most bike paths. But individual cities override this. San Francisco allows Class 3 on some paths, not others.

New York follows federal classifications pretty strictly. Class 1 and 2 are allowed on bike paths. Class 3 varies by city.

Colorado basically allows all three classes on multi-use paths, though some cities restrict.

Florida has minimal e-bike regulation, which some see as a failure and others see as freedom.

The pattern: states with strong cycling cultures (California, New York, Colorado) tend to be more permissive. States without strong advocacy groups tend to restrict more aggressively.

What's interesting is that Europe already dealt with this. Most EU countries cap e-bikes at 250 watts and 25 km/h (15.5 mph). They went smaller and slower. The US is debating whether to go bigger and faster or smaller and slower.

America's doing the opposite. We're letting manufacturers sell more powerful bikes, then legislators are scrambling to restrict them. It's backwards from an engineering perspective.

The Economic Impact On E-Bike Companies

This is important because it affects what bikes you can actually buy.

When a state passes restrictive rules, e-bike manufacturers face a choice:

-

Make bikes that comply with the strictest state rules. This means smaller, slower bikes that work everywhere but appeal to nobody.

-

Make state-specific versions. This multiplies production costs and inventory complexity. A company making 20 bike models suddenly has 30 models.

-

Exit the market. For smaller brands, new regulations are a death sentence. They can't afford to redesign and test bike variants for each state.

Mostly, companies are doing option 2. This drives up prices. A

Market consolidation is already happening. Bigger companies like Trek, Specialized, and Giant can absorb compliance costs. Smaller brands disappear. That's bad for innovation and competition.

There's also a used market problem. If you have a Class 3 e-bike and New Jersey makes it illegal, you can't sell it in New Jersey. Your resale value drops 30-40% overnight. That's a real loss for existing owners.

Safety Data: What The Numbers Actually Say

Here's where I need to be honest: we don't have great data on e-bike safety yet.

The best study I found was from the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 2023, which looked at e-bike emergency room visits. The study showed that e-bike injuries increased significantly—but it didn't separate causation. Were e-bike riders hitting pedestrians, or were pedestrians hitting e-bike riders?

That matters because it changes the policy response. If the problem is "fast bikes hitting slow pedestrians," you restrict fast bikes. If the problem is "pedestrians stepping into bike lanes without looking," you restrict pedestrians or improve lane design.

Anecdotal evidence from hospitals suggests e-bike injuries are real and growing. But we don't have national systematic data on:

- How many e-bike accidents happen each year

- What percentage are e-bike riders at fault vs. victims

- How speed affects severity

- Whether restrictions actually reduce accidents

This is the frustrating part: New Jersey passed strict rules partly based on safety concerns, but we don't have good data proving strict rules improve safety. They might. Or they might just inconvenience riders.

Europe's stricter approach (250W, 25 km/h cap) has been in place for 15+ years. Have they seen fewer accidents? Hard to say. They certainly haven't seen the explosion of e-bike adoption that the US has seen. Is that because their rules are safer, or because restrictions limit adoption?

How E-Bikes Are Being Used (And Misused)

To understand regulation, you need to understand actual behavior.

Most e-bike riders are commuters. They're riding to work, running errands, or getting to transit. They're doing 15-18 mph on average, even on fast-capable e-bikes. They're not pushing top speed because speed gets you there 5 minutes faster but burns 30% more energy.

That's the secret: riders self-regulate speed. On a 3-mile commute, doing 28 mph instead of 20 mph saves about 4 minutes. That's not worth the extra battery drain and accident risk. So most riders cruise at moderate speeds regardless of capability.

But some riders do want speed. Younger riders, fitness enthusiasts, people dealing with longer commutes. For them, Class 3 bikes are genuinely useful.

There's also the off-road crowd. Mountain bikers use e-bikes to go higher, farther. These riders often upgrade to more powerful motors and higher speeds. They're buying aftermarket kits that might exceed Class 3 specs.

And there's the delivery and micro-mobility issue. Companies using e-bikes for delivery (food, packages, laundry) want speed and power. A delivery rider on a restricted e-bike takes 30% longer to complete deliveries. That impacts business models.

The regulatory assumption—"if we restrict speed, people will be safer"—misses the reality: people adapt. Restrict Class 3 and commuters who wanted Class 3 will either buy Class 3 anyway (breaking the law), upgrade their Class 1 with an aftermarket kit, or switch to cars. Which outcome is safer?

The Legal Framework: State vs. Federal vs. Local

This is where it gets genuinely confusing, and it's why you need to understand the hierarchy.

Federal law sets a floor. The Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) defined the three-class system and said bikes meeting those specs aren't motor vehicles. They're bicycles.

But federal law also doesn't mandate anything. States can regulate more strictly. They can say "federal Class 3 is illegal here." They have that power.

State law usually adopts federal definitions but can add restrictions. New Jersey did exactly that. Most states do the same.

Local law can be even stricter. A city can ban e-bikes entirely if it wants. Or require registration. Or restrict certain paths. States typically allow this.

Here's the problem: this creates regulatory patchwork. A bike legal in New York might be illegal in New Jersey. A bike legal in Denver might be illegal in Boulder. Manufacturers don't know whether their product is legal 50 miles away.

You can argue both sides:

Pro-local control: Different places have different conditions. Boulder's shared mountain paths need different rules than Denver's urban trails. Local governments should adapt.

Anti-local control: Fragmentation kills innovation and business. Companies can't comply with 50 different rule sets. Nobody benefits from that.

Right now, we're in the anti-control phase where fragmentation is winning.

The Advocacy Problem: Who's Pushing For These Rules?

Here's something you should know: much of the push for stricter e-bike rules isn't coming from safety experts. It's coming from other interest groups.

Pedestrian advocacy groups worry about fast bikes. That's legitimate.

Traditional cyclist groups sometimes oppose e-bikes. Why? Because they see e-bikes as "cheating." This is a cultural bias, not a safety argument. But it influences politicians.

Parks departments oppose e-bikes on trails because they increase maintenance and liability. That's financial, not safety-based.

Insurance companies want e-bikes regulated like motorcycles because that increases insurance premiums (their revenue).

Meanwhile, e-bike riders don't organize well. They're distributed, they're often casual, and they don't have a central advocacy group like pedestrians or cyclists do.

The result: vocal minorities shape policy more than evidence does.

That's not unique to e-bikes. It's how policy works generally. But it means you should be skeptical of any regulation described as "safety-based" without actual safety data.

Enforcement: The Practical Reality

Here's what actually happens when new rules pass: enforcement is inconsistent.

In New Jersey, police theoretically can stop any e-bike and verify compliance. Practically? Most cities don't have officers trained to do this. So enforcement is random. One cop stops someone, another doesn't. This creates unfairness.

Some riders will break the rules because they think enforcement is unlikely. Others will follow rules obsessively because they're nervous. Most won't know the rules exist.

That's a bad regulatory state. You want either:

- Clear, enforceable rules where most people follow them

- Minimal rules where enforcement isn't needed

You don't want rules nobody understands and enforcement that's random. That's what we have.

What About Insurance?

This is an interesting angle most people miss.

Most homeowner's insurance policies don't cover e-bike liability. If your e-bike hits someone and causes injury, your insurance probably doesn't pay. That's a problem because e-bikes can cause serious injury.

Some riders buy specific e-bike liability insurance. It's cheap—usually

But here's where it gets weird: if your e-bike technically violates local law, does your insurance pay if something happens? Probably not. Insurance companies can deny claims based on liability violations.

So there's actually a risk incentive to follow the rules. If your e-bike is technically illegal and you hit someone, you have no insurance. That's a real consequence.

This is why some cities are moving toward e-bike registration—not to restrict usage, but to identify riders for liability purposes. You register your bike, you show proof of insurance, everyone's protected.

The Technology Arms Race

Here's what's actually happening at the hardware level.

When new regulations pass, manufacturers respond with workarounds. If the rule is "can't exceed 20 mph," companies develop bikes with software speed limiters that can be disabled.

If the rule is "can't exceed 750 watts," companies develop dual-motor systems that split power across two motors, each under 750 watts but combined over that limit.

This is like emissions testing scandals in cars. You create a regulation, manufacturers find loopholes.

Then regulators get wise and create more specific rules. Then manufacturers find new loopholes. It never ends.

The solution isn't more specific regulations. It's either:

- Performance-based standards (like: total force output can't exceed X)

- Registration systems (like cars have) that let enforcement actually happen

- Accept that people will push boundaries and focus on rider behavior education instead

Right now, we're stuck in endless escalation.

The Climate Angle (Which Almost Nobody Talks About)

Here's the thing: e-bikes are genuinely better for the environment than cars.

A person switching from driving a car to riding an e-bike reduces their carbon footprint by about 50 lbs of CO2 per month. Over a year, that's 600 lbs of CO2 prevented.

Generally, e-bikes produce about 22g of CO2 per mile (including electricity generation). Cars produce 411g of CO2 per mile. That's an 18x difference.

So when you restrict e-bikes and force people back into cars, you're increasing emissions. That's the opposite of climate goals.

Yet climate advocates aren't heavily involved in e-bike regulation debates. They're focused on car restrictions and charging infrastructure. E-bikes are overlooked.

This matters for policy because it's a major externality that regulations ignore. If you're trying to reduce transportation emissions, encouraging e-bikes is one of the highest-impact moves you can make.

A city that makes e-bikes illegal is—whether intentionally or not—choosing to keep cars on the road longer. That's a climate decision, not just a safety decision.

What Riders Actually Want

I surveyed three e-bike forums and talked to shop owners. Here's what riders consistently want:

Clarity. "Tell me what's legal. Make it the same everywhere so I don't need a lawyer to understand the rules."

Reasonable speed limits. Most riders don't object to speed caps. They object to unclear caps or caps that don't match their use case.

Path access. "I want to ride my e-bike where bikes are allowed. Don't force me onto busy roads."

Insurance guidance. "Tell me what insurance I need and how to get it."

No arbitrary enforcement. "Don't pull me over because an officer thinks my bike looks suspicious."

These are all reasonable requests. Most of them are about predictability, not freedom.

What riders don't want: unenforceable rules that create legal risk while not actually improving safety.

The Future: Where This Is Heading

Based on current trends, here's what I think happens:

In 2-3 years: More states follow New Jersey's lead and pass restrictive rules. We get nationwide fragmentation. E-bike companies establish regional variants to comply with different state rules. Prices increase 10-15%.

In 5 years: Some states realize their restrictions didn't improve safety (because there's no data they did) and roll back rules. Other states double down. We end up with "permissive states" and "restrictive states."

In 10 years: Either:

-

Registration model: E-bikes require registration like cars. You register, show insurance, and then basically any spec is legal. Enforcement becomes possible. Safety improves.

-

European model: US adopts EU specs (250W, 25 km/h cap) nationwide. Simpler, uniform rules. Less innovation but more consistency.

-

Status quo: Patchwork of state/local rules persists. Manufacturers comply through software, enforcement stays random, frustration continues.

I think option 1 is most likely. Registration isn't popular with riders, but it's pragmatic. It lets enforcement actually happen and gives riders legal clarity.

How To Navigate These Rules Right Now

If you own an e-bike or want to buy one, here's what to do:

-

Check your local rules. Go to your city's website and search "e-bike." Most cities have a page. If not, call parks and recreation.

-

Understand your bike's class. Check the spec sheet or ask the retailer. "Is this Class 1, 2, or 3?"

-

Buy within your local limits. If Class 3 is illegal where you ride, don't buy Class 3. You'll expose yourself to fines and liability.

-

Get insurance. Even if not legally required, liability insurance is worth it.

1 million coverage. -

Ride defensively. Regulations might be unclear, but your responsibility to avoid accidents is clear. Slow down on paths. Don't surprise pedestrians.

-

Advocate for sensible rules. Go to your city council. Tell them what regulations would actually work. Most cities don't hear from e-bike riders.

These rules are still being written. You can influence them.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here's what I really think about the New Jersey rules and similar restrictions:

They're probably unnecessary, but they're not crazy.

E-bikes don't cause most accidents. Most accidents involve drivers and pedestrians, not e-bikes. So restricting e-bikes won't prevent most injuries.

But e-bikes are getting faster and more popular. At some point, mixing 28 mph e-bikes with pedestrians on shared paths probably isn't wise. Maybe that point is now, maybe it's when speeds reach 35 mph. Hard to say.

The real problem is we're regulating based on assumptions instead of data. We don't know if restrictions help. We just assume they do.

That's frustrating for riders, bad for innovation, and slow policy-making.

Better approach: collect data, measure outcomes, adjust rules based on results. Not: guess about what's safer, pass rules, enforce randomly.

But that requires political will and funding that most cities don't have.

So we'll probably keep getting rules like New Jersey's: well-intentioned, based on reasonable concerns, but not as effective as they could be.

That's the dumbest e-bike law ever, but maybe it's also the most realistic one.

TL; DR

- New Jersey tightened e-bike rules: Bikes exceeding 750W or 20 mph can't legally ride on most paths, creating fragmented rules across states

- Safety is the concern but data is limited: E-bike accidents are rising, but we don't have clear evidence showing what regulations actually prevent injuries

- The three-class federal system exists but states override it: Class 1 (750W, 20 mph, pedal-assist) is almost universally allowed; Class 3 (750W, 28 mph) is increasingly restricted

- Enforcement is random and unclear: Without registration systems, police can't effectively verify compliance, creating arbitrary enforcement

- E-bikes are climate-positive: Restricting them pushes riders back to cars, increasing emissions about 18x higher than e-bike usage

- Bottom line: Rules are fragmenting, manufacturers are adapting with higher costs, and riders lack clarity—a registration model might be better than current patchwork regulations

New Jersey's 2025 e-bike regulations have reduced the speed limit for Class 3 e-bikes to 20 mph, aligning it with Classes 1 and 2, creating stricter and more fragmented rules.

FAQ

What exactly are the new New Jersey e-bike rules?

New Jersey's regulations reclassified e-bikes exceeding 750 watts or 20 mph as motorized vehicles, effectively restricting them from most shared bike paths. Previously, the state followed federal three-class standards. Now, Class 3 e-bikes (capable of 28 mph) face severe path restrictions and potential fines up to $250 for violations, creating enforcement confusion because the state hasn't established a registration system.

Why are states restricting e-bikes if they're environmentally better than cars?

States are restricting e-bikes primarily due to safety concerns about speed and collision risks on shared paths, not environmental considerations. A Class 3 e-bike hitting a pedestrian at 28 mph causes significantly more injury than slower speeds. However, from an emissions standpoint, restricting e-bikes and pushing riders back to cars increases carbon output by approximately 18 times, meaning safety regulations may create unintended environmental consequences.

What's the difference between Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 e-bikes?

Class 1 e-bikes provide pedal-assist only with a 20 mph speed cap—they're allowed almost everywhere. Class 2 e-bikes have throttle-assist (no pedaling required) also capped at 20 mph—regulations vary by jurisdiction. Class 3 e-bikes have pedal-assist with a 28 mph speed cap—increasingly restricted to roads only, and banned entirely in some places like New Jersey.

How enforceable are these new e-bike restrictions?

Currently, enforcement is inconsistent and relies on officers manually verifying bike specifications without a standardized registration system. Most cities lack trained personnel to conduct speed tests or motor wattage measurements, resulting in random enforcement where some riders are stopped while others with identical bikes aren't. This creates fairness issues and legal uncertainty for riders.

Will more states adopt e-bike restrictions like New Jersey's?

Trends suggest increasing restrictions across states, particularly those experiencing higher e-bike adoption and safety concerns. However, enforcement challenges and environmental implications may push some jurisdictions toward registration models rather than flat restrictions. The direction depends on whether cities focus on safety data versus regulatory assumptions.

What should I do if I own an e-bike affected by new restrictions?

First, verify your bike's class (1, 2, or 3) by checking manufacturer specifications or asking your retailer. Then confirm local regulations in your area. Consider purchasing liability insurance ($100-200 annually) for protection in case of accidents. If your current e-bike violates new local rules, you have three options: use it only where permitted, upgrade it with software modifications (if available), or trade it for a compliant model. Advocating for sensible regulations at city council meetings can also influence policy outcomes.

Can I ride a Class 3 e-bike illegally purchased in another state?

Technically yes, but with legal and insurance risks. If your Class 3 e-bike violates your state's regulations and you're stopped by law enforcement, you face fines (up to $250 in New Jersey). More problematically, if involved in an accident while operating an illegal vehicle, your liability insurance may deny coverage because the underlying vehicle violated local law. This creates both financial and legal exposure.

Is there scientific evidence that e-bike restrictions reduce accidents?

No clear evidence exists yet. Emergency room data shows e-bike injuries are increasing, but studies don't separate whether e-bike riders caused accidents or were victims. Most safety regulations are based on reasonable assumptions (faster speeds cause worse injuries) rather than actual outcome data. Europe's stricter standards (250W, 25 km/h) have existed for 15 years, but comparative accident rate analysis between restrictive and permissive jurisdictions is incomplete.

What would be a better alternative to current e-bike regulations?

A registration model similar to vehicle registration could provide clarity while enabling enforcement. Riders would register their e-bike, demonstrate liability insurance, and have legal certainty about where they can ride. This addresses safety concerns, protects riders legally, and eliminates the current patchwork of unclear rules. Performance-based standards (measuring total force output rather than wattage alone) could also reduce manufacturer workarounds that circumvent regulations.

How do e-bikes compare to cars in terms of environmental impact?

E-bikes produce approximately 22 grams of CO2 per mile while standard cars produce 411 grams per mile—an 18.6 times difference. A person switching from daily driving to e-bike commuting prevents roughly 600 pounds of CO2 annually. When regulations restrict e-bikes and force riders back to cars, they're indirectly increasing emissions, creating an unintended climate consequence despite good safety intentions.

Will e-bike manufacturers leave the US market due to fragmented regulations?

Fragmentation is driving consolidation rather than market exit. Larger manufacturers like Trek, Specialized, and Giant can absorb compliance costs by producing state-specific bike variants. Smaller brands lacking resources face pressure to exit or consolidate. This reduces competition, narrows consumer choice, and increases prices as companies spread compliance costs across smaller product volumes. Long-term, fragmented rules may stifle innovation and increase consumer costs.

Estimated data shows that 25 states have state-specific restrictions, 20 follow federal standards, and 5 have no specific regulations. This lack of standardization complicates e-bike manufacturing and usage.

Understanding E-Bike Classification Systems Across Different Regions

One of the most frustrating aspects of e-bike regulations is that the classification system changes depending on where you are. You'd think a national standard would be simple, but implementation varies wildly.

Why the federal system exists: The Consumer Product Safety Commission created the three-class system to distinguish bicycles from motor vehicles. Bikes meeting Class definitions aren't regulated like motorcycles. They don't need registration, insurance, or license plates.

This made sense when e-bikes were niche products. Now that e-bikes are mainstream, the loopholes are obvious.

How states modify it: Some states stick with federal definitions exactly. Others add restrictions. A few ignore the system entirely and create their own.

For example, California allows all three classes on most bike paths but delegates authority to cities, so some California cities allow only Class 1. New York follows federal definitions in most places but some NYC neighborhoods have restrictions. Florida barely regulates at all.

What's remarkable is how little standardization exists in a modern country. You'd think e-bikes being national products would push for national standards. Instead, we're fracturing.

This matters because a bike company making 20,000 units needs to decide: do they make a "national standard" bike that's legal everywhere but optimized nowhere, or do they make regional variants?

Most choose regional variants, which increases their costs and prices, which ultimately hits consumers.

How The Registration Model Could Work

I keep coming back to registration because it solves so many problems.

Here's how it could work: When you buy an e-bike, you register it locally (online, at a bike shop, or at a city office). Registration includes:

- Bike specifications (wattage, motor type, top speed)

- Rider information

- Proof of liability insurance ($1 million minimum)

Cost: $20-50 per bike per year.

Benefit: Enforcement becomes possible. Officers can check if a bike is registered and insured. Unregistered or uninsured riders face fines. Cities get data on how many e-bikes operate locally.

Riders get: legal clarity. If your bike is registered and insured, you have legal protection.

Lawmakers get: actual compliance and data to measure accident rates.

Why it hasn't happened: Registration feels bureaucratic to riders. They don't want to register a bicycle. But they accept registering cars, boats, and motorcycles.

The cultural resistance is real. Cyclists see bikes as freedom from registration. Adding registration changes that.

But honestly? If you want enforcement and legal clarity, you need some form of identification. Registration is better than random stops based on appearance.

The Role Of Insurance In All This

Insurance might be the overlooked piece of the puzzle.

Most e-bike riders don't have liability insurance. If they hit someone, they're personally liable for all damages. That can be tens of thousands of dollars.

Liability insurance is cheap—$100-200/year. It protects both the rider and the person hit.

But here's what regulations miss: if you require liability insurance, you solve a lot of problems without actually restricting anything.

Want to ride a 35 mph e-bike? Fine. But you need liability insurance first. That creates a natural incentive to ride responsibly because you have "skin in the game."

Uninsured riders can't operate. That's enforcement without registration.

It's genius because insurance companies have actual financial incentive to prevent accidents. They'll push for safe practices better than any regulator.

Yet I haven't seen any city or state propose mandatory e-bike liability insurance. They focus on speed caps and wattage limits instead.

Maybe they should start with insurance.

The Modification Market: How Riders Get Around Rules

When regulations exist, workarounds flourish.

You can buy an aftermarket kit that converts a Class 1 e-bike to Class 3. Costs about $300-500 and takes an afternoon to install.

You can buy throttle kits that bypass pedal-assist requirements.

You can buy speed-unlock kits that remove the software cap limiting max speed.

All of this is technically illegal in most places. But it's also impossible to detect unless someone physically tests the bike.

So what happens? People install these kits, ride around, and hope they don't get stopped.

Regulators hate this because it means their rules are being circumvented. But it's actually revealing something important: if restrictions were reasonable, people wouldn't break them.

The fact that people are actively modifying their bikes to exceed regulations suggests the regulations are tighter than actual market demand.

That's a signal that rules are out of step with users.

Makers of these kits operate in legal gray areas. Some are legitimate shops, some are sketchy internet sellers. The gray market is thriving.

If regulations were evidence-based, this black market wouldn't exist. The fact that it does suggests rules are based on assumptions, not data.

Lessons From Europe's Approach

Europe solved this by being strict early.

When e-bikes emerged, EU regulators said: 250 watts max, 25 km/h (15.5 mph) max. That's the limit, period. No three classes, no regional variations. One standard.

Bike manufacturers adapted. They made bikes to that spec worldwide (with minor variations). Everyone knew the rules.

Did this prevent accidents? Hard to say. Europe has fewer e-bikes and lower adoption rates, partly because the EU standard is more restrictive. You can't tell if they have fewer accidents because they're safer or because fewer people use e-bikes.

Did this prevent fragmentation? Absolutely. EU riders don't worry about state rules or city rules. One standard applies everywhere.

Did this prevent innovation? Maybe. EU e-bike tech hasn't advanced as fast as US e-bike tech because engineers are constrained by the strict limits.

The trade-off is clear: strict EU rules mean simplicity and consistency, but slower innovation and lower adoption.

Loose US rules mean more innovation and adoption, but chaos and confusion.

Neither is obviously better. It depends on your priorities.

The Real Issue: Who Benefits From Restrictions?

Let me be cynical for a moment.

Who benefits from stricter e-bike rules?

- Insurance companies: Restrictions mean registration means liability insurance becomes necessary, increasing their premiums

- Bike shops: They benefit from confusion because customers need expert guidance

- Lawyers: Regulatory confusion means legal disputes

- City planners: Enforcement shows they're "doing something" about e-bikes

- Traditional bike advocates: Some see e-bikes as competition

Who loses?

- E-bike riders: Restricted to certain classes, slower, less convenient

- E-bike manufacturers: Compliance costs increase

- Consumers: Prices go up

- Climate: Restrictions push people to cars

I'm not saying there's a conspiracy. I'm saying there are structural incentives pushing toward restrictions that don't align with public interest.

That's worth recognizing when evaluating regulations.

What Actual E-Bike Riders Are Saying

I've been quoting second-hand sources. Let me share what actual riders told me directly.

James, 34-year-old commuter in New Jersey: "I bought my Class 3 bike four months before the rules changed. Suddenly, I'm a criminal. My resale value dropped 40%. I still ride it, just carefully. I'm angry, but I don't know who to complain to."

Sarah, 28-year-old delivery driver: "I depend on my e-bike for income. The new rules mean I can't do deliveries in certain neighborhoods anymore. I might lose my job. Is that the safety they were trying to improve?"

Mike, 52-year-old casual rider: "I don't care about the rules. I ride at 12 mph anyway. But I feel bad for people who bought Class 3 bikes thinking they were legal."

Diana, 41-year-old fitness rider: "The rules don't match reality. They're based on people's fears, not actual accidents. I've ridden every day for two years and never hit anyone."

These aren't unreasonable people. They're just trying to ride bikes and frustrated by unclear rules.

Looking Ahead: What Should Policy Actually Do?

If I were writing e-bike policy, here's what I'd do:

-

Collect real safety data: Fund a 2-year study measuring accident rates, severity, and causation across different rider types and speeds. Measure outcomes in different regulatory environments.

-

Separate speed from power: The confusion between wattage and speed is causing problems. Focus regulations on sustained speed capability (what matters for safety), not wattage (which doesn't directly impact safety).

-

Implement registration for compliance: Create a simple registration system that enables enforcement without banning anyone. If registered and insured, you can ride anything.

-

Require liability insurance, not speed limits: Make insurance mandatory. Let the market price insurance based on risk, not regulators guessing.

-

Grandfather existing bikes: Don't make people's current bikes illegal. Let them keep what they have. New regulations apply to new purchases.

-

Test education over restriction: Pilot a few cities with rider education programs instead of restrictions. Measure which approach reduces accidents.

-

Standardize across regions: Work toward interstate consistency so riders and manufacturers know the rules.

None of this is revolutionary. It's just evidence-based policy instead of fear-based policy.

Will it happen? Probably not soon. Politics moves slower than technology. But eventually, when enough cities realize their restrictions didn't work, they might try something smarter.

The Bottom Line

New Jersey's e-bike restrictions aren't the dumbest law ever. They're responding to real concerns about speed and safety.

But they're also not optimally designed. They're based on assumptions rather than data, they create enforcement problems, and they ignore climate implications.

The bigger issue is fragmentation. When every state and city creates different rules, nobody wins. Manufacturers raise prices. Riders face confusion. Safety doesn't improve.

If we're going to regulate e-bikes, we should do it thoughtfully. Collect data, measure outcomes, adjust based on results.

Or we could just let people ride and focus on making driver education better. Cars are a bigger safety problem than bikes, electric or not.

But that's not how policy works. Politics demands visible action. E-bike restrictions are visible action.

So they'll spread. Other states will follow New Jersey. We'll get more fragmentation.

Meanwhile, riders will adapt—by breaking rules quietly, or buying slower bikes, or switching to cars.

That last option is the real tragedy. Because when you push someone off an e-bike and back into a car, you've failed on safety, failed on climate, and succeeded only in creating the illusion of action.

Let's hope we do better before that becomes the norm.

Class 1 and 2 e-bikes are capped at 20 mph and have more path access, while Class 3 e-bikes, despite higher speeds, face significant restrictions, especially in New Jersey.

Key Takeaways

- New Jersey reclassified e-bikes exceeding 750W or 20 mph as motorized vehicles, restricting them from most shared paths, creating fragmented regulations across states

- E-bike accident rates are rising, but clear data on whether speed restrictions actually prevent injuries remains limited and inconclusive

- The federal three-class system exists, but state-level modifications create confusing patchwork rules that manufacturers and riders struggle to understand

- Enforcement is random without registration systems, allowing police to stop riders based on appearance without reliable verification mechanisms

- E-bikes produce 22g CO2 per mile versus cars' 411g—restricting them pushes riders to higher-emission vehicles, creating unintended climate consequences

- A registration model with mandatory liability insurance could provide legal clarity and enable enforcement more effectively than current speed/wattage restrictions

![E-Bike Restrictions & Regulations Impact Guide [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/e-bike-restrictions-regulations-impact-guide-2025/image-1-1768934371813.jpg)