EU Digital Networks Act: Why Big Tech Got a Pass [2025]

Europe just handed Big Tech a golden ticket. And almost nobody noticed.

When the European Commission formally introduced the Digital Networks Act in January 2025, something unexpected happened. Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Netflix—the companies that have dominated European tech policy for years—essentially got off the hook. Instead of facing strict new legal obligations, they'll simply follow a "voluntary best practices framework" monitored by Europe's telecoms regulator.

Meanwhile, telecoms firms will absorb the real regulatory burden.

On the surface, this looks like a shocking reversal. For a decade, Brussels has been the world's most aggressive tech regulator. GDPR, the Digital Markets Act, the Digital Services Act. Europe made its reputation by holding Big Tech accountable.

So what changed? Why did the EU suddenly go soft?

The answer lies in a combination of geopolitical pressure, infrastructure strategy, and a fundamental reframing of who actually bears responsibility for the internet's backbone. Understanding this shift matters because it signals where European tech regulation is headed, what it means for Big Tech's future, and whether other regulators will follow Brussels' lead.

Let's dig into what actually happened, why it happened, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- The DNA targets telecoms, not Big Tech: Despite generating massive internet traffic, tech giants face no new legal obligations under the Digital Networks Act

- Big Tech gets a voluntary framework: Google, Meta, Amazon, and others will cooperate on best practices, monitored informally by BEREC

- Geopolitical pressure matters: Trump administration threats against EU tech enforcement influenced the regulatory shift

- Infrastructure is the real focus: The DNA prioritizes removing copper networks and upgrading to full fiber, plus undersea cable security

- Negotiations still pending: The Act requires approval from EU member states and Parliament before becoming law

The Digital Networks Act is expected to move from negotiation to full compliance by 2027, with significant progress anticipated by mid-2026. Estimated data.

What is the Digital Networks Act (DNA)?

The Digital Networks Act isn't a tech regulation in the traditional sense. It's infrastructure policy disguised as digital governance.

Unlike the Digital Markets Act (which targets Big Tech's market dominance) or the Digital Services Act (which regulates content moderation), the DNA focuses on the physical and logical networks that carry data across Europe. Its core mission: modernize Europe's telecom infrastructure to compete with US and Chinese networks.

Henna Virkkunen, Vice President of the European Commission for Technological Sovereignty, Security, and Democracy, framed the DNA as an opportunity to boost Europe's competitiveness and increase investment in telecommunications infrastructure. This language matters. The DNA isn't about punishing tech giants. It's about economic strategy.

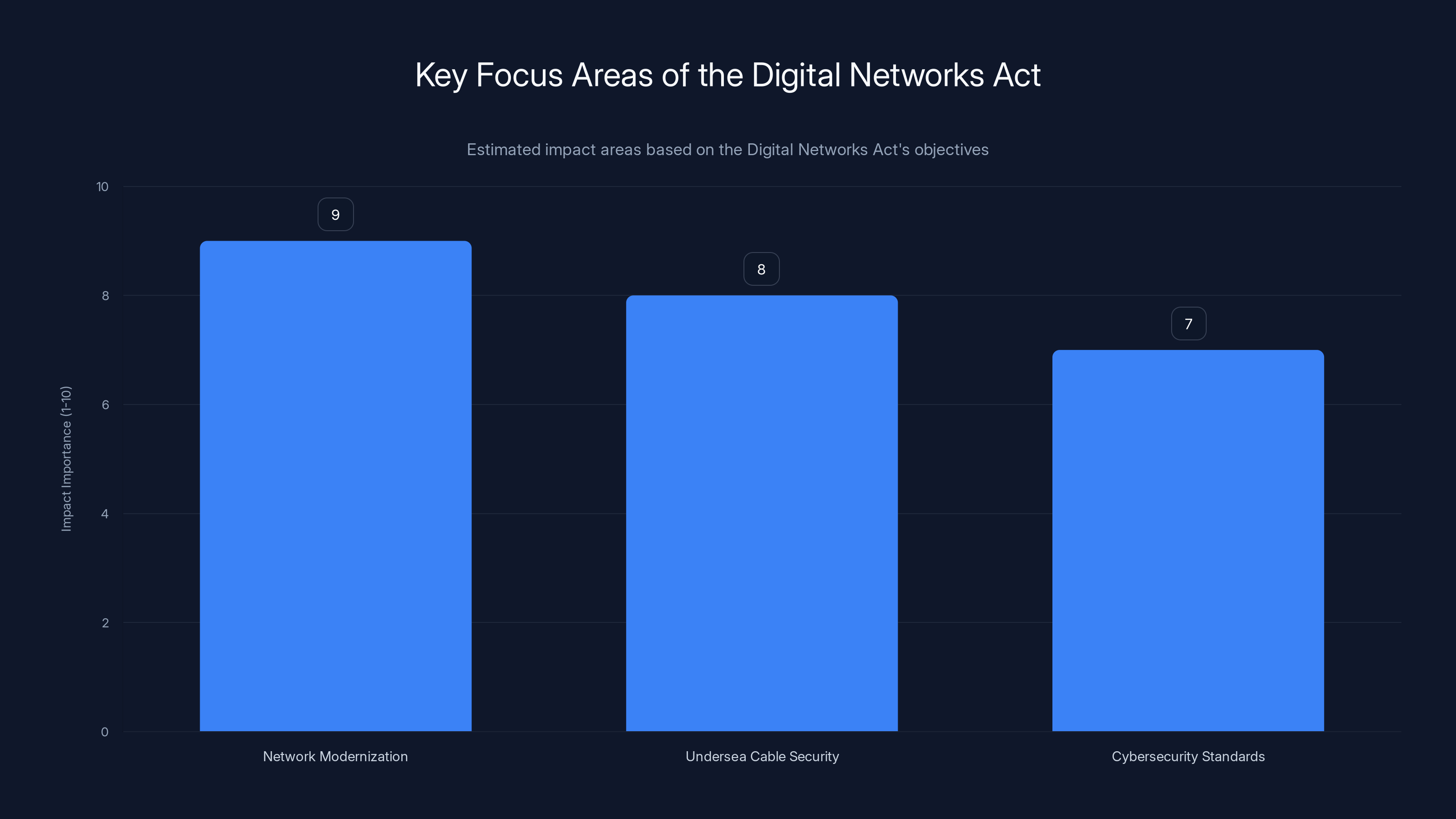

The Act addresses three specific problems:

Network modernization: Europe's telecom infrastructure is outdated. Copper-based networks still dominate, particularly in Eastern Europe. The DNA pushes member states to accelerate the transition to full fiber and other next-generation technologies. This isn't abstract—it means upgrading thousands of kilometers of aging infrastructure that can't support 21st-century speeds.

Undersea cable security: An increasingly overlooked vulnerability in internet infrastructure is physical security. Undersea cables carry roughly 99% of intercontinental data traffic. Damage from ship anchors, fishing trawlers, or deliberate sabotage can knock entire regions offline. The DNA requires member states and telecom providers to strengthen security protocols around these critical assets.

Cybersecurity standards: The Act establishes baseline cybersecurity requirements across critical networks, including 5G infrastructure, backbone networks, and interconnection points. This is genuinely important—but it's also something the telecoms industry has been lobbying for, since it raises barriers to entry for competitors while imposing regulatory costs on everyone.

The Digital Networks Act prioritizes network modernization, undersea cable security, and cybersecurity standards, with modernization being the most critical. Estimated data.

Why Big Tech Isn't Regulated Under the DNA

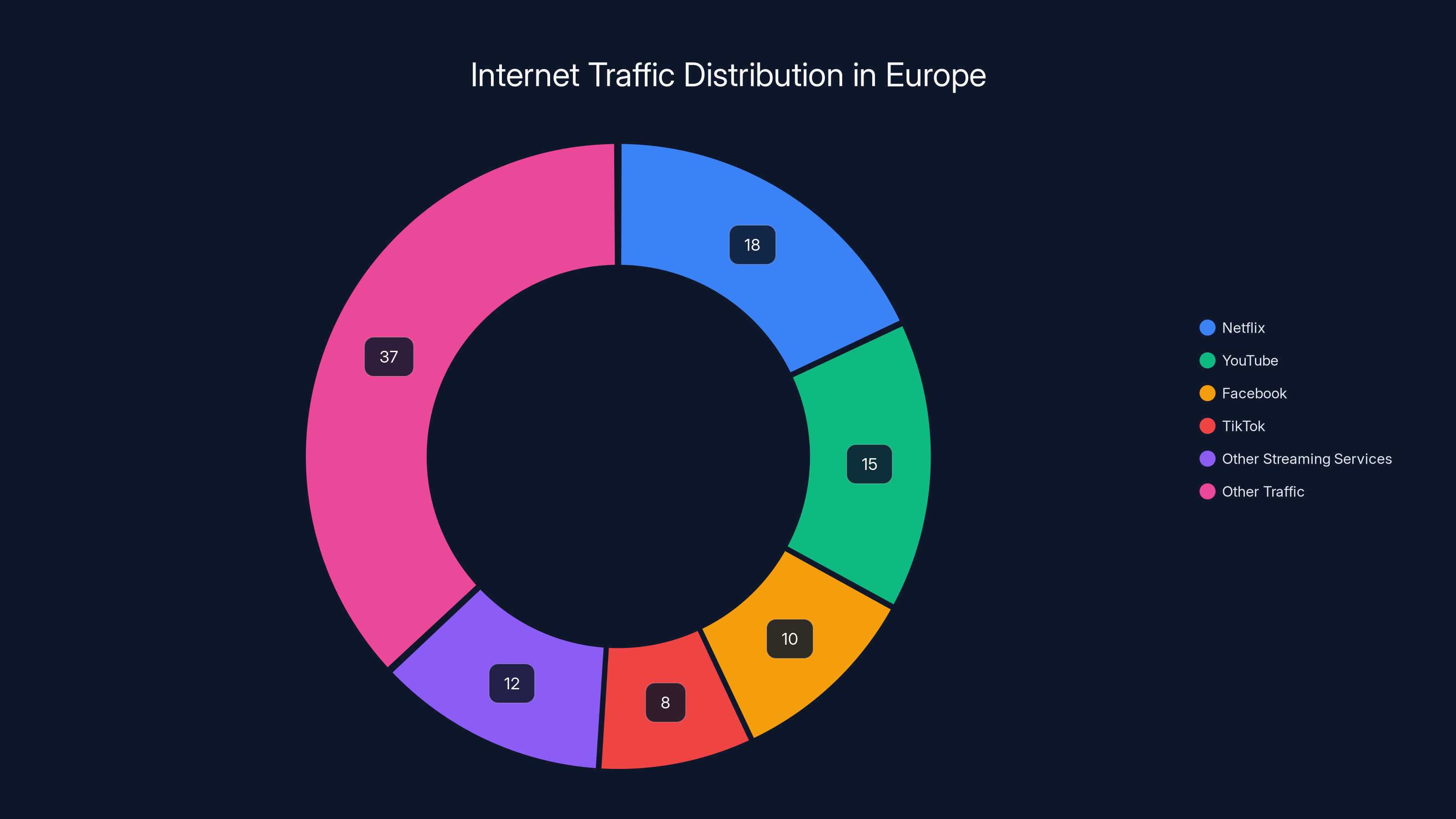

Here's the surprising part: Tech giants generate the majority of internet traffic in Europe. Netflix alone accounts for roughly 15-20% of peak traffic in many European networks. YouTube, Facebook, TikTok, and streaming services collectively drive more than 50% of all data consumption.

Yet none of them are regulated under the DNA. Instead, they'll follow a voluntary best practices framework.

This isn't accidental. It's strategic.

The Commission made a deliberate decision to separate two regulatory spheres:

Sphere 1 - Infrastructure Operators (Regulated): Telecom companies, internet service providers, data center operators. These entities control the physical networks and must comply with the DNA's requirements.

Sphere 2 - Content and Service Providers (Voluntary): Tech platforms like Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft. These companies provide services over the network but don't own the infrastructure.

The logic is straightforward: you can only regulate what you control. Tech giants don't control European networks. Telecom operators do. So the DNA targets telecom operators.

But there's a catch. Tech companies will still be monitored by BEREC (Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications), Europe's telecoms regulator. The Commission hasn't specified exactly what "monitoring" means, which has created significant ambiguity about enforcement mechanisms.

The Geopolitical Context: Why Europe Backed Down

You can't understand the DNA without understanding what happened six weeks before it was announced.

In late 2024, the Trump administration made explicit threats against the European Union's tech enforcement. Officials accused Brussels of launching "discriminatory and harassing lawsuits" against American companies. The language was sharp. The US threatened to use "every tool at its disposal" to counter Europe's enforcement efforts.

Days later, Meta was hit with a $1.4 billion privacy fine. Google faced another investigation into search dominance. Apple was under scrutiny for app store practices.

The timing created obvious pressure.

America's threat wasn't empty rhetoric. The US has multiple mechanisms to retaliate: tariffs on EU goods, trade disputes at the WTO, restrictions on EU companies accessing US markets, even diplomatic pressure on other countries. Europe's economy, while substantial, remains vulnerable to US economic leverage.

Some observers have speculated that the DNA's exemption for Big Tech represents a calculated retreat. Instead of facing escalating trans-Atlantic conflict, the Commission redirected regulatory attention toward telecom operators, who are overwhelmingly European. This accomplishes multiple goals:

- Appeases the US: American tech companies aren't hit with new obligations

- Protects European telecom operators: Forces them to upgrade infrastructure using public investment and private capital

- Maintains regulatory authority: The Commission still controls policy, just pointed at different targets

- Aligns with economic strategy: Infrastructure investment benefits European economies more directly than fines against American companies

Whether this was intentional positioning or coincidental timing remains debated among policy analysts. But the correlation is undeniable.

Estimated data shows that Netflix, Google, Amazon Web Services, and Microsoft are major beneficiaries of the DNA's network upgrades, with Netflix receiving the largest share of benefits.

How the DNA Changes European Tech Regulation

The DNA represents a fundamental shift in Brussels' regulatory approach. For the first time, Europe is explicitly decoupling infrastructure regulation from content regulation.

This matters because it suggests a new strategy. Instead of treating "Big Tech" as a monolithic enemy requiring comprehensive legislation, the Commission is fragmenting the problem:

Digital Markets Act (DMA): Targets platform dominance and anticompetitive behavior. Applies to "gatekeepers" who control access to digital markets.

Digital Services Act (DSA): Regulates content moderation, algorithmic transparency, and illegal content removal. Applies to all digital service providers above a certain size.

Digital Networks Act (DNA): Regulates physical and logical infrastructure. Applies to network operators, not content providers.

Each law targets a different layer of the internet stack. This is actually more sophisticated than earlier attempts at comprehensive tech regulation. It acknowledges that Amazon (as a cloud infrastructure provider), Meta (as a social platform), and Deutsche Telekom (as a network operator) face entirely different regulatory challenges.

But it also reveals a weakness: the DNA's voluntary framework for Big Tech creates an enforcement gap. What happens if Google or Meta ignores the best practices? The Commission's answer remains unclear.

The Infrastructure Investment Problem

Europe's telecom infrastructure is actually in worse shape than most people realize.

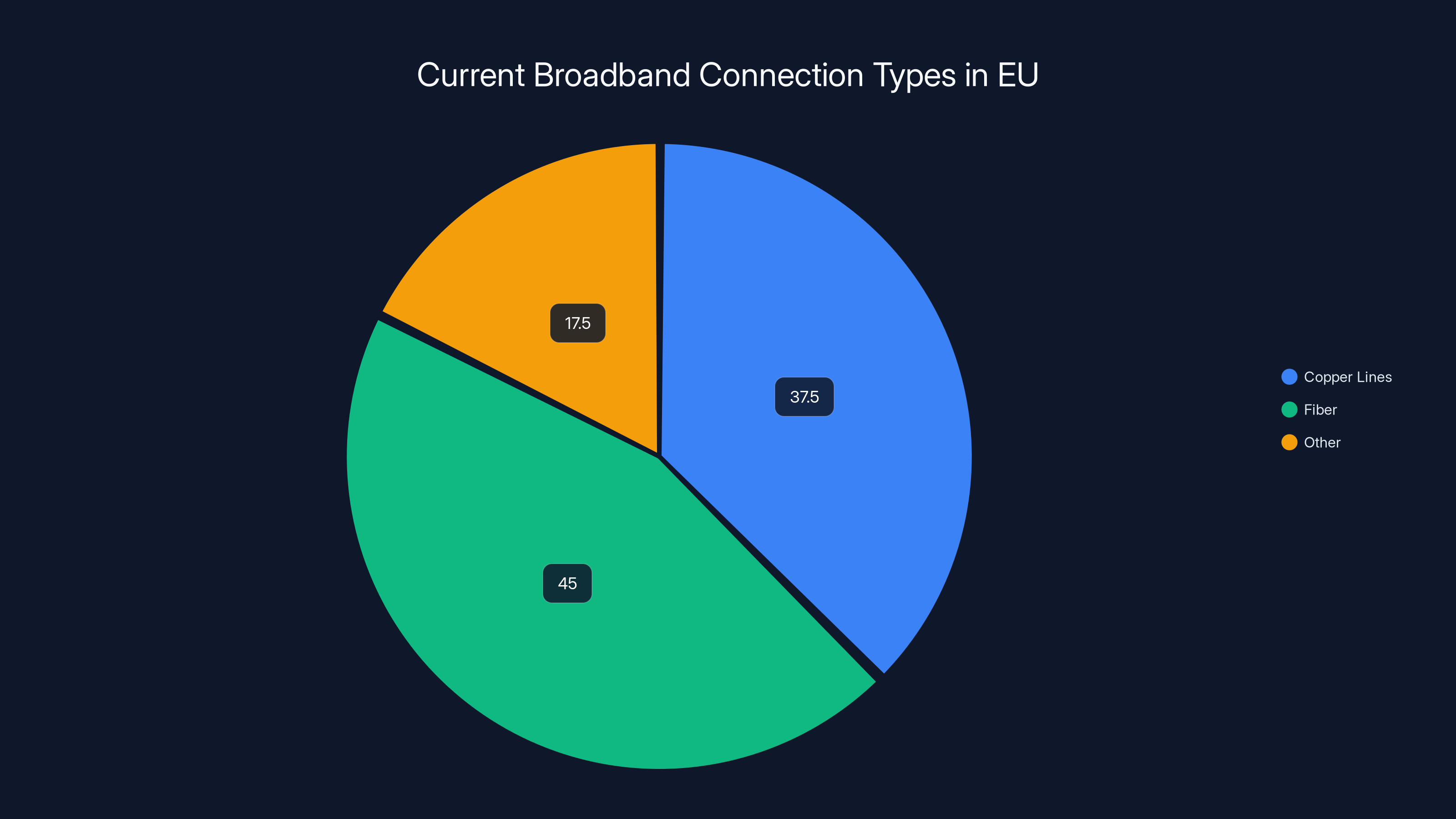

According to industry data, copper lines still account for roughly 35-40% of "fixed" broadband connections in EU member states. This is absurdly outdated. Copper networks, designed for voice calls in the 1970s, cannot reliably support gigabit-speed broadband. They degrade over distance. They're vulnerable to weather, corrosion, and physical damage.

Meanwhile, the US has been aggressively upgrading to fiber. China is also moving faster. Europe is falling behind on a critical infrastructure metric.

The DNA addresses this explicitly. It sets targets for fiber deployment and creates regulatory frameworks to accelerate the transition. But here's the problem: upgrading infrastructure costs money.

Estimates suggest that reaching the DNA's fiber deployment targets could require $100-150 billion in cumulative investment across the EU. This money has to come from somewhere. European telecom operators argue they can't fund this alone. The answer, in European policy, is always the same: government subsidies and structural funding.

Which means the DNA's infrastructure mandates will translate into public spending. EU member states will have to allocate resources to broadband infrastructure programs. This is politically harder than regulating companies—it requires budget commitments, competing against healthcare, education, and defense spending.

For Big Tech, this is actually beneficial. Better infrastructure means faster networks, which improves their service quality and reduces operational costs. They get the benefit without bearing the cost.

Tech giants like Netflix, YouTube, and Facebook drive over 50% of internet traffic in Europe, yet remain unregulated under the DNA. (Estimated data)

How Big Tech Actually Benefits from the DNA

This is the part that rarely gets discussed: the DNA might actually be good for Big Tech.

Consider Netflix's position. It generates massive traffic on European networks, which costs telecom operators money to carry. Telecom operators have periodically demanded that Netflix pay higher interconnection fees or fund infrastructure upgrades. Netflix has resisted.

The DNA changes the equation. By mandating that telecom operators upgrade to fiber regardless, the Commission essentially socializes the cost. Netflix gets better, faster networks without negotiating directly with operators. Taxpayers cover the infrastructure bill.

Similarly, Google benefits from faster, more reliable networks. Amazon Web Services benefits. Microsoft benefits. All the major cloud providers benefit from improved infrastructure they didn't have to pay for.

Meanwhile, smaller telecom operators face significant compliance costs. Upgrading network infrastructure requires capital expenditure, specialized expertise, and regulatory approval. This consolidates the market further—larger operators can afford the compliance burden. Smaller regional operators struggle.

So the DNA accomplishes something remarkable: it looks like regulation, but it actually functions as industrial policy that protects American tech giants while consolidating European telecom operators.

The Voluntary Framework: What Does It Actually Mean?

Here's where the DNA gets murky: what is this "voluntary best practices framework" for Big Tech?

According to the Commission's statements, tech companies will cooperate with BEREC to establish best practices around network management, traffic prioritization, and interconnection. These aren't legally binding. They're recommendations. Tech companies can ignore them without legal consequence.

BEREC will "monitor" compliance, but the Commission hasn't defined what monitoring means. Does it involve quarterly reports? Audits? Public scorecards? Nobody knows yet. The details will be worked out during the negotiations between member states and Parliament.

This ambiguity might be intentional. It allows the Commission to claim it's regulating Big Tech while actually imposing minimal obligations. It's political cover—the Commission can tell critics that it addressed the problem, even though the framework lacks enforcement teeth.

Alternatively, BEREC monitoring could be serious. The body could request detailed data on how tech companies manage network traffic, prioritize content delivery, and interconnect with other operators. It could issue recommendations that, while non-binding, carry significant weight. Tech companies might comply out of fear that non-compliance triggers stricter legislation.

Based on BEREC's track record, the second scenario seems more likely. BEREC has traditionally taken its advisory role seriously, conducting detailed investigations and publishing findings that influence both industry practice and regulatory policy.

But here's the key: without explicit legal obligations, BEREC's leverage is limited to reputation and the implicit threat of future legislation. Tech companies can afford to ignore soft recommendations if the regulatory environment remains favorable.

Copper lines still account for an estimated 37.5% of broadband connections in the EU, highlighting the need for significant investment in fiber infrastructure. Estimated data.

Member State and Parliamentary Negotiations: What Could Change

The DNA isn't law yet. The Commission presented a proposal. Now it faces negotiations between EU member states and the European Parliament.

This is where the final shape of the regulation emerges.

Member states have conflicting interests. Germany and France, home to large telecom operators and tech companies, will push for lenient requirements. Poland and Romania, with underdeveloped fiber infrastructure, will want generous EU funding. Nordic countries, which already have excellent broadband, will focus on cybersecurity and standardization.

The Parliament, meanwhile, has shown willingness to strengthen tech regulations in the past. The DSA and DMA both emerged with Parliament pushing the Commission to include stronger enforcement mechanisms and broader applicability.

Several scenarios are plausible:

Scenario 1 - Status Quo: The DNA passes roughly as proposed. Big Tech remains unregulated. Telecom operators face infrastructure mandates. This is the Commission's apparent preference.

Scenario 2 - Parliament Strengthening: Parliament adds enforcement mechanisms for the voluntary framework, making it quasi-binding. Tech companies face clearer obligations and potential penalties for non-compliance. This seems unlikely but possible.

Scenario 3 - Partial Compromise: Member states split the difference. Big Tech faces some new obligations (perhaps around network transparency or traffic management), but nothing as strict as DMA or DSA-level requirements. This seems moderately likely.

Scenario 4 - Geopolitical Escalation: US pressure intensifies, forcing the Commission to further weaken Big Tech provisions or withdraw them entirely. This would represent a significant shift in EU regulatory independence.

Historically, EU negotiations over tech legislation have taken 2-4 years from proposal to final adoption. The DNA could face similar timelines, meaning the final version might not be law until 2026 or 2027.

Undersea Cable Security: The Hidden Critical Infrastructure Problem

One aspect of the DNA that deserves more attention is its focus on undersea cable security.

Most people don't realize how dependent global internet is on cables. There are roughly 500 active submarine cables carrying intercontinental data. They range from transatlantic cables owned by consortiums of tech companies to regional cables serving specific countries.

These cables are vulnerable. In the past five years, there have been several high-profile incidents:

- 2024: A Chinese fishing vessel damaged undersea cables in the Baltic Sea, disrupting traffic to several Scandinavian countries

- 2023: Multiple cables in Southeast Asia were cut simultaneously, attributed to ship anchor damage

- 2022: Cables near Taiwan were damaged, creating regional connectivity issues

The pattern suggests that cable disruptions might not all be accidental. Some analysts believe state actors are testing vulnerabilities. Cutting cables could be a wartime or hybrid warfare tactic.

The DNA addresses this by requiring member states and operators to:

- Monitor cable routes and alert operators to unusual activity

- Increase physical security around cable landing stations

- Redundancy requirements (critical cables must have backup routes)

- Rapid incident response protocols

This is genuinely important infrastructure hardening. It's not glamorous, but it's critical. If European cables were cut, European internet connectivity would degrade significantly, particularly for services that don't have adequate geographic redundancy.

Big Tech actually benefits from these requirements. Stronger cable security makes European infrastructure more reliable, which benefits all services running over those cables. And again, the cost is borne primarily by operators and governments, not by content companies.

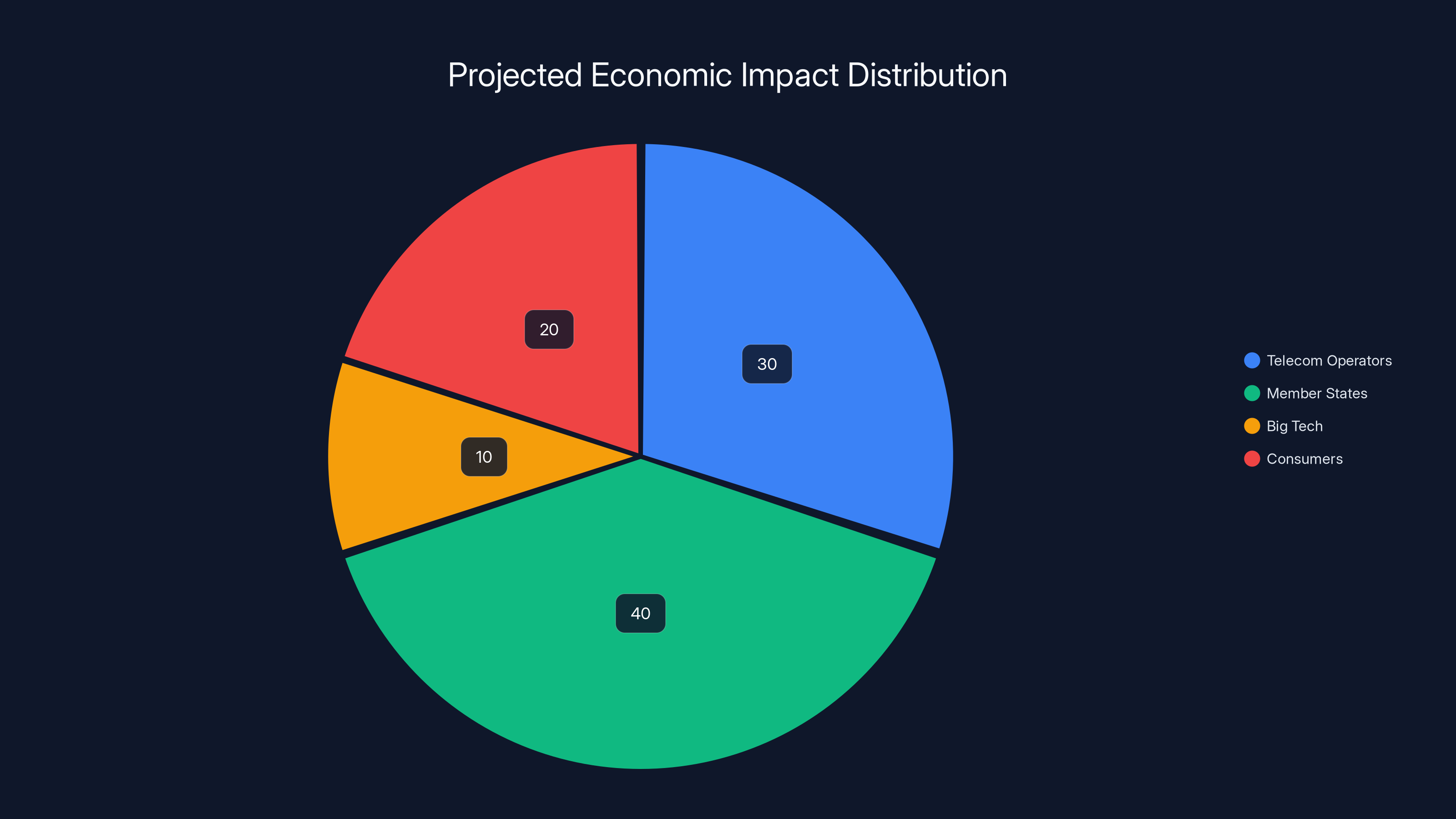

Estimated data shows that member states and telecom operators bear the majority of the economic impact, while consumers and Big Tech benefit indirectly.

5G and Network Modernization Standards

The DNA includes requirements around 5G deployment and cybersecurity standards that might seem technical but have real consequences.

Europe has been slower than the US and China in 5G rollout. Several factors contributed: fragmented regulations across member states, security concerns about equipment vendors (particularly concerns about Chinese manufacturers), and the cost of upgrading infrastructure.

The DNA attempts to accelerate 5G by:

Harmonizing standards: Member states must adopt common technical standards for 5G infrastructure. This reduces fragmentation and allows operators to deploy more efficiently.

Addressing vendor security: The Act includes implicit requirements around equipment vendor diversity. It doesn't explicitly ban any countries' manufacturers, but it requires security assessments that make it harder to rely entirely on single-source vendors.

Cybersecurity baselines: The DNA establishes minimum cybersecurity standards for 5G networks, including encryption, authentication, and intrusion detection requirements.

For Big Tech, this matters because 5G quality affects service delivery. Better 5G networks enable better mobile experiences, which benefits Meta, Google, TikTok, and others. And these improvements are funded by telecom operators and government programs, not by the tech companies themselves.

The Role of BEREC in DNA Enforcement

BEREC will play a central role in DNA implementation and compliance monitoring.

BEREC isn't a traditional regulator with legal authority to fine companies or mandate compliance. Instead, it functions as an advisory body that coordinates among national telecom regulators and provides recommendations to the European Commission.

Under the DNA, BEREC's role expands. It will:

Monitor operator compliance: Request annual reports from telecom operators on infrastructure investment, fiber deployment progress, and cybersecurity measures.

Facilitate best practices for Big Tech: Work with tech companies to develop and update the voluntary best practices framework.

Publish findings: Issue periodic reports on DNA implementation, infrastructure progress, and security incidents.

Coordinate member states: Help harmonize implementation across different EU countries, which have different regulatory structures and telecom markets.

BEREC's independence is important here. It's not directly controlled by individual member states or the Commission. It's a technical body that operates with some degree of autonomy. This gives it credibility when it makes recommendations or findings.

However, BEREC's actual enforcement leverage remains limited. It can't fine companies. It can't impose penalties. It can only report to the Commission, which might then take action. This creates a gap between monitoring and actual enforcement.

How This Compares to US and Chinese Tech Regulation

To understand the DNA's significance, it helps to see how it compares to regulation in other major markets.

United States: The US has historically been hands-off on Big Tech regulation. Infrastructure is regulated separately from content services. The FCC oversees telecom companies. The FTC addresses Big Tech competition and privacy issues. There's no comprehensive tech regulation like GDPR or DSA.

The DNA is more interventionist than the US approach, but less so than Europe's DMA and DSA. It picks a middle path.

China: Chinese regulation is comprehensive but state-directed. The government controls key telecom operators and internet companies. Regulation serves explicit state objectives (surveillance, controlling information flows, promoting domestic champions). There's no pretense of market-driven regulation.

The DNA, by contrast, maintains the fiction of independent regulation by an unbiased technocratic body. Whether that fiction holds is debatable, but it's distinct from the openly political approach in China.

European model (DNA + DMA + DSA): Together, these three laws create a layered regulatory framework. The DNA handles infrastructure. The DMA handles market dominance. The DSA handles content. This is more comprehensive than the US approach but more market-oriented than China's approach.

Other countries are watching. Australia, UK, EU member states, and others are considering similar regulatory structures. The DNA's approach to separating infrastructure from content regulation might become a template.

The Economic Impact: Costs, Investment, and Competition

The DNA's economic impact will be substantial, though distributed unevenly.

Telecom operators: Will face compliance costs estimated at $15-25 billion for infrastructure upgrades across the EU. Larger operators like Deutsche Telekom, Vodafone, and Orange can absorb these costs. Smaller regional operators face significant burden, likely leading to consolidation.

Member states: Will need to commit EU structural funds to broadband infrastructure programs. This could require $30-50 billion in public investment over the next decade, competing with other priorities.

Big Tech: Will benefit from better infrastructure without bearing direct costs. They might face minimal compliance costs for the voluntary framework. Net impact: positive.

Consumers: Should benefit from faster, more reliable networks. But the cost is primarily borne through taxes and higher broadband prices (operators will pass costs to consumers). The benefit might be unevenly distributed—urban areas get upgrades faster than rural areas.

Competitive dynamics: The compliance burden consolidates the telecom operator market. Smaller operators can't afford the investment. This could reduce competition, leading to higher prices. Paradoxically, a regulation intended to strengthen European infrastructure might actually reduce competition.

What This Means for Big Tech's Future in Europe

The DNA tells us something important about the EU's regulatory direction.

For the past decade, Brussels focused on reigning in Big Tech's power. GDPR, DMA, DSA—all aimed at constraining American tech companies. The EU positioned itself as the world's most aggressive tech regulator.

The DNA suggests this approach is changing. Instead of directly regulating Big Tech, the Commission is:

- Redirecting enforcement toward infrastructure operators (mostly European)

- Creating voluntary frameworks that look like regulation but lack enforcement teeth

- Focusing on economic competitiveness rather than purely on constraint

- Acknowledging geopolitical reality by backing down in response to US pressure

This doesn't mean Big Tech gets off completely. The DMA and DSA remain in force. But it does suggest the peak of aggressive EU tech regulation might have passed.

Companies like Google, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft can probably expect:

- Continued enforcement of existing laws (DMA, DSA) but limited expansion of new obligations

- More focus on transparency and cooperation than on penalties

- Increasing pressure from individual member states, which might impose their own requirements

- A shift toward negotiated settlements rather than purely adversarial regulation

The Political Timeline: When Does DNA Actually Take Effect?

If you're planning compliance, timelines matter.

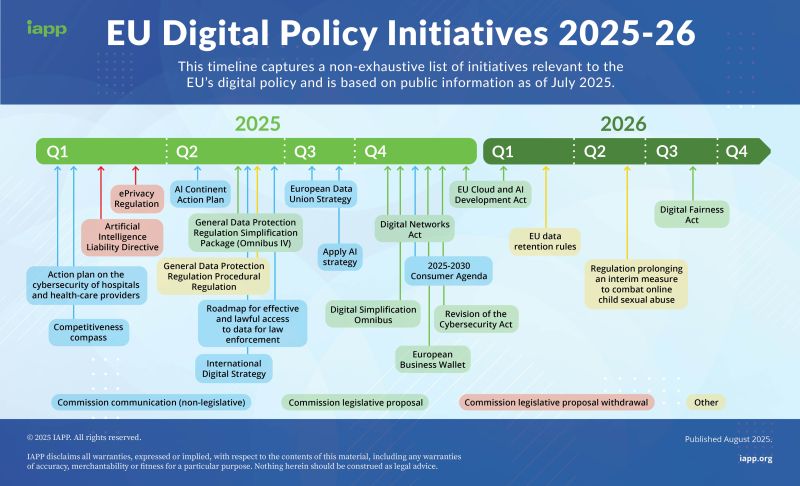

The DNA was formally presented in January 2025. From here:

Q1-Q3 2025: Negotiations between the Commission, member states, and Parliament. Different committees debate provisions. Industry provides input. This phase typically surfaces major disagreements.

Q4 2025 - Q2 2026: Negotiations intensify. Trialogue discussions (three-way negotiations between Commission, Parliament, and member states) work out compromises. Key decisions about enforcement mechanisms and timelines are made.

Q3 2026 - Q4 2026: Likely adoption timeline. The DNA could become law in 2026, though this is optimistic. EU legislative timelines often slip.

2027 onwards: Member states implement the DNA into national law. Compliance deadlines begin. Telecom operators start reporting on infrastructure investment and security measures.

2028-2030: Full compliance by most operators. Infrastructure upgrades are visible. BEREC issues its first comprehensive enforcement reports.

So realistically, if you're a telecom operator affected by the DNA, you have 18-24 months to prepare before compliance obligations kick in. If you're Big Tech, the timeline is more uncertain because the voluntary framework isn't yet defined.

Risk Factors: What Could Go Wrong?

The DNA faces several implementation risks:

Member state resistance: Some countries might resist infrastructure mandates, particularly if they require significant public funding. Eastern European countries, which lag on fiber deployment, might seek exemptions or longer timelines.

Geopolitical escalation: If US-EU trade tensions increase, further pressure could undermine the DNA's Big Tech provisions. Alternatively, if the EU experiences security incidents (cable cuts, cyberattacks), pressure for stricter security measures could intensify.

Technology change: By the time the DNA is implemented (2027-2028), technology might have changed significantly. 6G research is underway. Satellite internet is becoming viable. Quantum computing could change security calculus. The DNA's provisions might become outdated faster than expected.

Compliance cost shock: If infrastructure upgrade costs exceed $200 billion, operators might seek exemptions or timeline extensions. This could delay implementation and create political pressure to weaken requirements.

Cyber incidents: A major breach or infrastructure attack during the DNA negotiation phase could trigger demands for stricter security provisions, shifting the regulatory balance toward more oversight.

Looking Ahead: The Future of European Tech Regulation

The DNA represents a strategic shift, but it's not the final word on European tech regulation.

Several trends suggest further regulatory evolution:

Fragmentation risk: As individual member states implement the DNA, they might add national variations. This could fragment the European digital market, creating compliance challenges for pan-European operators. The Commission will likely need to harmonize implementation rules.

Security focus: Geopolitical tensions (Russia, China, cyber threats) will probably keep security high on the regulatory agenda. Future rules might include more explicit requirements around encryption, vendor diversity, and incident reporting.

AI regulation: The DNA doesn't address AI, but the EU's AI Act does. As AI becomes more central to network management and content delivery, regulatory overlap will emerge. This could trigger new legislation coordinating AI and network regulation.

International alignment: The EU is likely to push for DNA-like frameworks in other countries. This could become a template for "European-style" digital regulation, creating trading partners' pressure to adopt similar rules.

FAQ

What is the Digital Networks Act and what does it regulate?

The Digital Networks Act is European Union legislation that focuses on modernizing telecom infrastructure and strengthening network security rather than regulating tech platforms. It targets network operators to upgrade copper networks to fiber, secure undersea cables, and establish cybersecurity standards. Unlike the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act, the DNA doesn't directly regulate Big Tech companies—instead, they'll follow a voluntary best practices framework monitored by BEREC.

Why does the DNA exempt Big Tech from new legal obligations?

The Commission separated regulation by layer: infrastructure operators (regulated) and content providers (voluntary). The logic is that you regulate entities that control infrastructure, not services that use it. Tech giants provide services over networks but don't own the infrastructure, so they fall under voluntary frameworks instead. This decision was also influenced by geopolitical pressure from the US, which threatened retaliation against EU tech enforcement.

How does the Digital Networks Act compare to the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act?

The three laws regulate different layers: the DMA targets platform dominance and anticompetitive behavior; the DSA regulates content moderation and algorithmic transparency; the DNA regulates physical and logical infrastructure. Together, they create a comprehensive regulatory framework. The DNA is less stringent than the DMA and DSA because it relies on voluntary cooperation from Big Tech rather than legal obligations.

What are the implementation timelines for the Digital Networks Act?

The DNA is currently in the negotiation phase (early 2025). Member states and the European Parliament must approve it before it becomes law, likely by mid-2026. Member states then have time to implement it into national law. Full compliance deadlines for infrastructure upgrades and cybersecurity measures will probably fall between 2027-2030, though specific timelines depend on final negotiations.

How much will the Digital Networks Act cost to implement?

Estimates suggest

What role will BEREC play in Digital Networks Act enforcement?

BEREC will monitor operator compliance with infrastructure and security requirements, request annual reports, coordinate implementation across member states, and publish findings. However, BEREC has limited enforcement leverage—it can't fine companies or impose penalties directly. It can only make recommendations and report to the Commission, which might then take enforcement action. This creates a gap between monitoring and actual enforcement.

How does the Digital Networks Act affect Big Tech companies like Google and Meta?

Big Tech companies benefit from better infrastructure funded by operators and governments without bearing direct costs. They face minimal compliance obligations under the voluntary framework and no new legal obligations. They'll cooperate on best practices monitored by BEREC, but without enforcement mechanisms. This is a significant shift from Europe's previous approach of strict regulation through the DMA and DSA.

Will the DNA increase broadband costs for consumers?

Probably yes. Telecom operators will pass infrastructure upgrade costs to consumers through higher broadband prices. The extent depends on how much public funding covers investment costs. In countries with significant EU subsidies, price increases might be moderate. In countries relying primarily on private investment, increases could be steeper. Rural areas might see faster deployment but potentially higher prices to offset lower population density.

What about undersea cable security—why is that important?

Submarine cables carry roughly 99% of intercontinental data traffic. Recent incidents suggest cables are vulnerable to both accidental damage and potentially deliberate interference. The DNA requires member states and operators to increase security monitoring, improve physical protection, and establish redundancy for critical cables. This is genuinely important for European resilience and could affect service reliability.

Could the Digital Networks Act change if negotiations continue?

Absolutely. The DNA as proposed is a starting point. Member states and Parliament will negotiate changes. Parliament has historically pushed for stronger enforcement mechanisms in EU tech legislation, so enforcement mechanisms for the Big Tech voluntary framework might be strengthened. Alternatively, geopolitical pressure could weaken Big Tech provisions further. Major changes are likely before final adoption in 2026.

Conclusion: Europe's Regulatory Pragmatism

The Digital Networks Act tells a story about how regulation works in practice.

Theory says regulators are independent technocrats who apply rules objectively. Reality is messier. Regulation reflects economics, geopolitics, political leverage, and competing interests. The DNA shows all of these forces in action.

Brussels spent a decade building a reputation as the world's most aggressive tech regulator. Then geopolitical pressure mounted. The US threatened retaliation. The Commission faced a choice: escalate the conflict or find a way to claim regulatory authority while minimizing confrontation.

The DNA accomplishes this. It looks like regulation. It establishes new rules. It creates monitoring mechanisms. But Big Tech isn't really regulated under it. The real targets are European telecom operators, which can't retaliate diplomatically. Meanwhile, the Commission maintains its authority and proposes something resembling a solution to Europe's infrastructure problems.

This is pragmatism disguised as principle. It might also be smart strategy. Bruising trade wars with the US serve nobody well. Focusing on infrastructure investment makes genuine economic sense. Separating infrastructure regulation from content regulation is conceptually cleaner than previous attempts at comprehensive tech legislation.

But it also represents a retreat from the aggressive regulatory stance that defined European tech policy. Other regulators—in the UK, Australia, Canada—are watching. If the EU has pulled back from aggressive tech regulation under geopolitical pressure, that signals something important about the limits of unilateral regulatory power.

For Big Tech, the DNA is good news. For European operators and consumers, it's mixed. Infrastructure improves, but costs rise and market consolidation accelerates. For policymakers, it represents a pragmatic acceptance of geopolitical constraints.

The DNA will likely pass in some form. Details will change during negotiation. Implementation will be messier and slower than planned. But the basic framework—infrastructure regulation for operators, voluntary frameworks for Big Tech—will probably hold.

That represents a significant shift in European tech regulation. Whether it's a positive or negative shift depends on your perspective. But it's undeniably a shift. And shifts in regulatory direction tend to cascade. If Europe is pulling back, other countries might follow. If the US is successfully defending its tech companies through geopolitical pressure, that's a lesson other governments will learn.

The story of tech regulation isn't just written in courtrooms and regulatory offices. It's written in geopolitical negotiations, trade tensions, and the balance of power between governments and corporations. The DNA shows all of these forces shaping how the digital economy actually gets governed.

Key Takeaways

- Big Tech faces no new legal obligations under the DNA—only voluntary best practices monitored informally by BEREC

- The DNA prioritizes infrastructure modernization (fiber deployment, undersea cable security) over tech platform regulation

- Geopolitical pressure from the US administration influenced the EU's decision to exempt Big Tech from strict new requirements

- Telecom operators will bear the compliance burden, potentially consolidating the European market and increasing consumer costs

- The DNA represents a strategic shift away from aggressive tech regulation toward pragmatic economic policy

![EU Digital Networks Act: Why Big Tech Got a Pass [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/eu-digital-networks-act-why-big-tech-got-a-pass-2025/image-1-1767969380483.jpg)