The Fitbit Founders Are Back—And They're Thinking Bigger Than Wearables

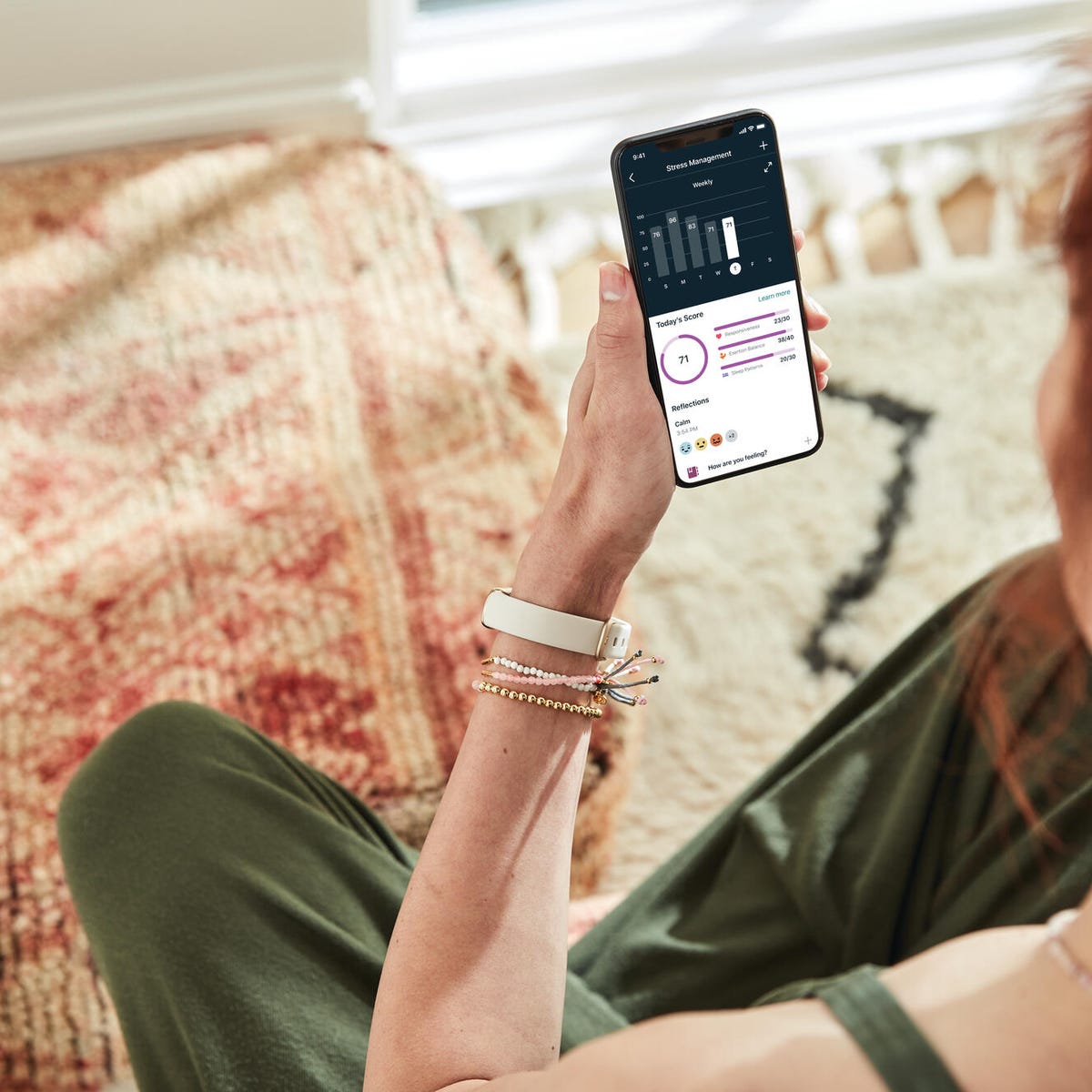

James Park and Eric Friedman didn't just leave money on the table when Google acquired Fitbit. They left an entire ecosystem of untapped opportunity. Now they're back with something different. Not another smartwatch. Not another fitness band. They're building a family-wide health tracking system that captures wellness data across every member of your household—including your pets.

I'll be honest: when I first heard about this, my reaction was skeptical. Family health apps have been tried before. Most failed because they were either too complicated, too invasive, or solved problems nobody actually had. But here's what caught my attention: the founders aren't positioning this as a fitness app. They're positioning it as a family health platform. That's a meaningful distinction.

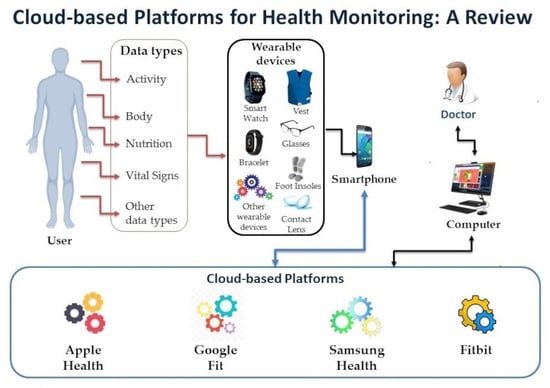

The wearables market has matured considerably since Fitbit's early days. Smartwatches are everywhere now. Your Apple Watch tracks everything. Your Android phone has built-in health monitoring. Even your smart ring counts steps. So what's the gap these founders are trying to fill?

Simple: nobody's built a cohesive platform that lets families track their collective health. Your spouse's sleep. Your kids' activity levels. Your elderly parent's heart rhythms. Your dog's weight and movement patterns. All in one place. All designed for oversight without being creepy. That's harder than it sounds. And it's probably why most companies haven't tried.

Understanding the Family Health Market Gap

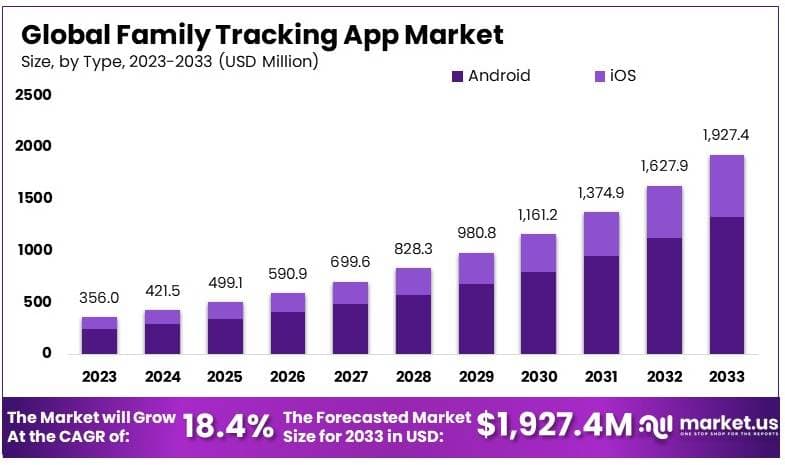

The health and fitness tracking industry generated over $4 billion in revenue globally during 2023. Yet the family health segment remains massively underserved. Why? Because building for families requires solving fundamentally different problems than building for individuals.

When you design a fitness tracker, you're optimizing for one person's motivation. One person's goals. One person's privacy expectations. Scale that to a family of five, and suddenly you're managing competing privacy requirements, different health conditions, varying levels of tech comfort, and the constant tension between transparency and autonomy.

Consider this scenario: you want to monitor your elderly parent's heart rate patterns because they live alone. But your parent doesn't want to feel surveilled. Your teenager wants activity tracking for sports performance. But they don't want you knowing where they are all the time. Your spouse wants sleep quality data for medical reasons. But they don't want weight trends shared automatically with you.

Each person in that family has different comfort levels. Different needs. Different expectations about what health data means. The existing solutions are fragmented. Some families use Apple Health to sync data across iPhones and Apple Watches. Others use Google Fit on Android devices. Fitness enthusiasts might use Strava for activity tracking. Parents concerned about kids' health might use specific parental control apps. But nothing integrates all of these perspectives into a single, thoughtfully designed experience.

This is the problem the new platform from Park and Friedman aims to solve. Not by forcing everyone onto one wearable ecosystem, but by creating a family-focused software layer that aggregates health data from multiple devices and presents it in ways that respect individual privacy while enabling collective insights.

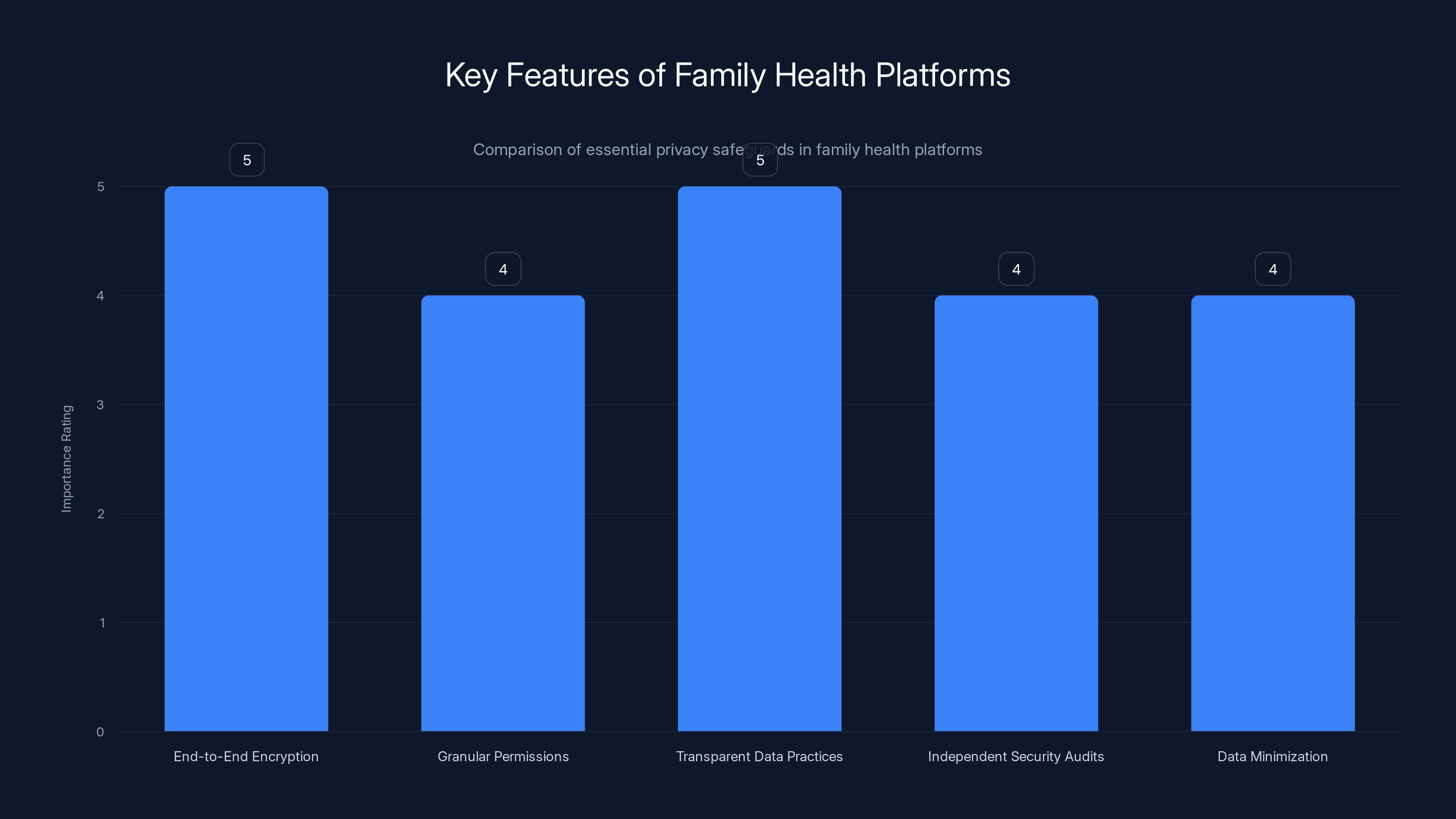

End-to-end encryption and transparent data practices are crucial for family health platforms, rated highest in importance. Estimated data based on privacy trends.

What Makes Family Health Tracking Different From Personal Fitness

Personal fitness tracking is about individual optimization. You run more, you track it, you feel good about improvement. It's gamified. It's motivational. It's about you versus yesterday's you.

Family health tracking requires a completely different approach. Here's why:

Different health priorities across age groups. Your toddler's health metrics (developmental milestones, sleep patterns) matter for different reasons than your teenager's (sleep, activity, nutrition) or your elderly parent's (heart rate variability, fall risk, medication adherence). A single interface designed for personal fitness makes no sense for these diverse needs.

Privacy becomes exponentially more complex. In a personal fitness app, you control your own data. In a family system, you're navigating consent, autonomy, and trust between people with different relationship dynamics. Parents monitoring teens. Adult children monitoring aging parents. Partners checking on each other. All of this requires sophisticated permission systems.

Motivation mechanisms change. Individual fitness apps use competition, streak systems, and personal achievement. Family health systems need different levers. A parent might be motivated by ensuring their child gets enough sleep. A teenager might be motivated by transparency with peers (shared activity challenges). An elderly person might be motivated by maintaining independence.

Medical context matters more. When you're tracking a single healthy adult, you're mostly watching trends. When you're tracking a family, someone might have diabetes, someone else might have hypertension, someone might be recovering from surgery. The context around each metric becomes critical.

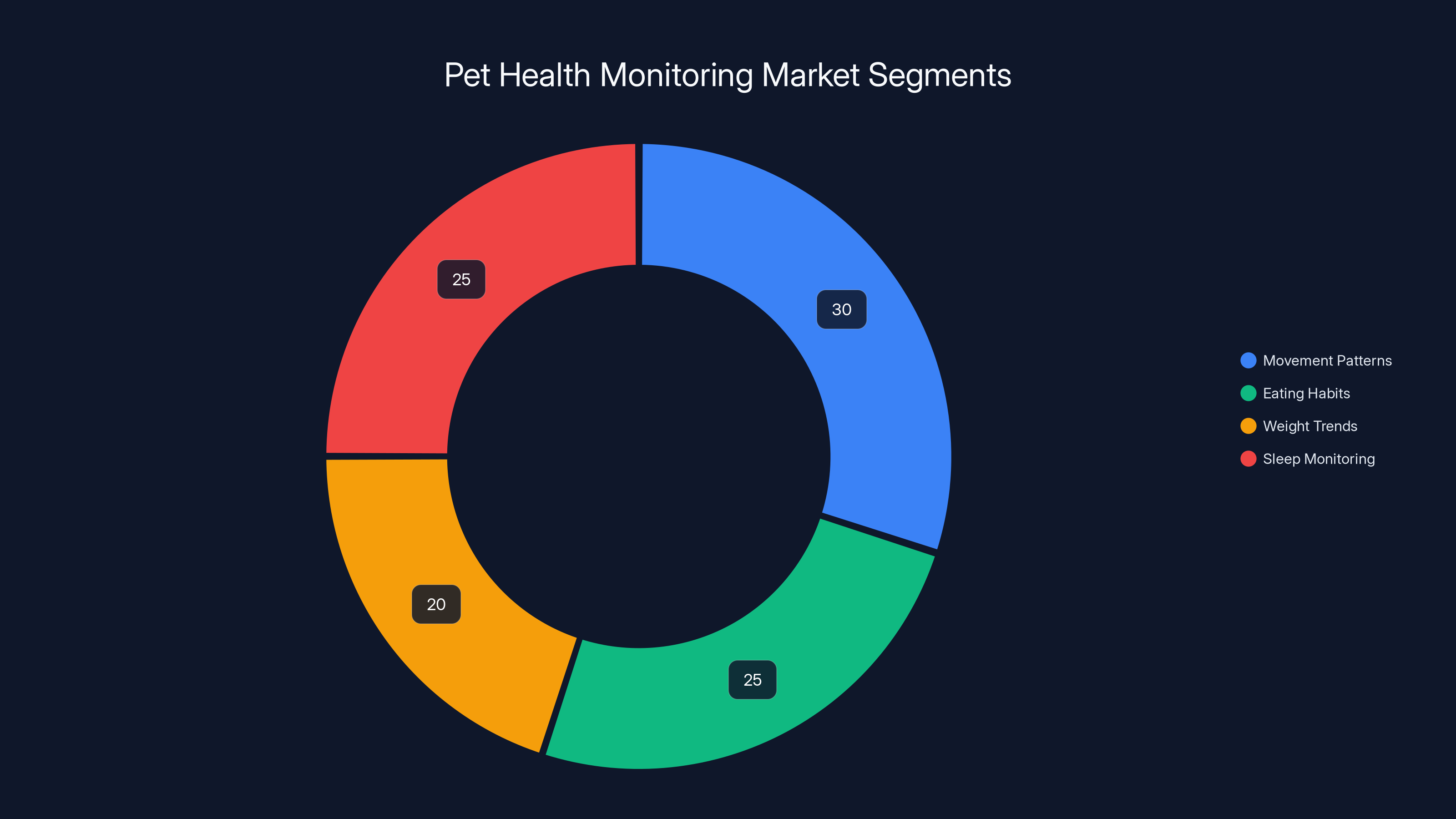

Pet health tracking focuses on movement, eating, weight, and sleep, each contributing significantly to early health issue detection. Estimated data.

The Hardware Question: Do You Need New Wearables?

Here's where I'm honestly uncertain about the founders' strategy. They haven't publicly committed to building new hardware. They could approach this as a software platform that works with existing devices.

That's the smart play, actually. If they tried to launch their own wearable line, they'd compete against Apple (with the Apple Watch and AirPods), Google (Pixel Watch, Pixel Band), Garmin, Whoop, Oura, and a dozen others. That's not 2013 anymore when Fitbit was the undisputed market leader. That's a brutal, low-margin game.

But—and this is a significant but—the best family health tracking might require some proprietary hardware. Why? Privacy. If your health data stays on cloud servers, it's vulnerable. If it passes through Google's or Apple's ecosystems, it's subject to their privacy policies and business models. Some families might want a more private option.

Likely scenario: they'll launch with a software platform that aggregates data from existing devices. Then, in the follow-up product cycle, they might offer optional hardware: a family hub device (think HomePod-sized health data center), simpler wearables designed specifically for family use, or pediatric trackers built for kids' physical development.

They could also go the open-source route and let other manufacturers build compliant hardware. That would be strategic. Position themselves as the neutral platform layer above the hardware wars.

Pet Health Tracking: The Unexpected Differentiator

Wait. Pet health tracking?

Yes. And honestly, this might be the most interesting part of their strategy.

Pet health is a $50+ billion global industry. Pet owners spend more on vet care than ever before. And here's the thing nobody talks about: pet health monitoring is way less developed than human health monitoring. Your dog can't tell you when something's wrong. Your cat shows symptoms late in most illnesses.

If you can track a pet's movement patterns, eating habits, weight trends, and sleep, you can catch health problems earlier. A significant decrease in activity might indicate pain or illness. Unusual eating patterns might suggest metabolic issues. Changes in sleep could indicate stress or age-related decline.

The pet health angle serves multiple purposes for this new company:

-

Market expansion. Most pet owners aren't fitness enthusiasts. They're regular people who love their animals. By including pets in a family health platform, they expand beyond the fitness tracker demographic.

-

Emotional connection. Health tracking for humans can feel like self-judgment. But tracking your dog's health? That's pure love. That's caring for a family member. The emotional framework is completely different, which changes how people engage with the platform.

-

Data richness. Pets provide clean signals. They don't have conflicting motivations or social factors. If your dog's activity dropped 40%, something's wrong. That clarity is valuable for algorithm training and health insights.

-

Regulatory advantage. Pet health data isn't regulated the same way as human health data. That gives them flexibility to experiment with features that might face regulatory friction in human health.

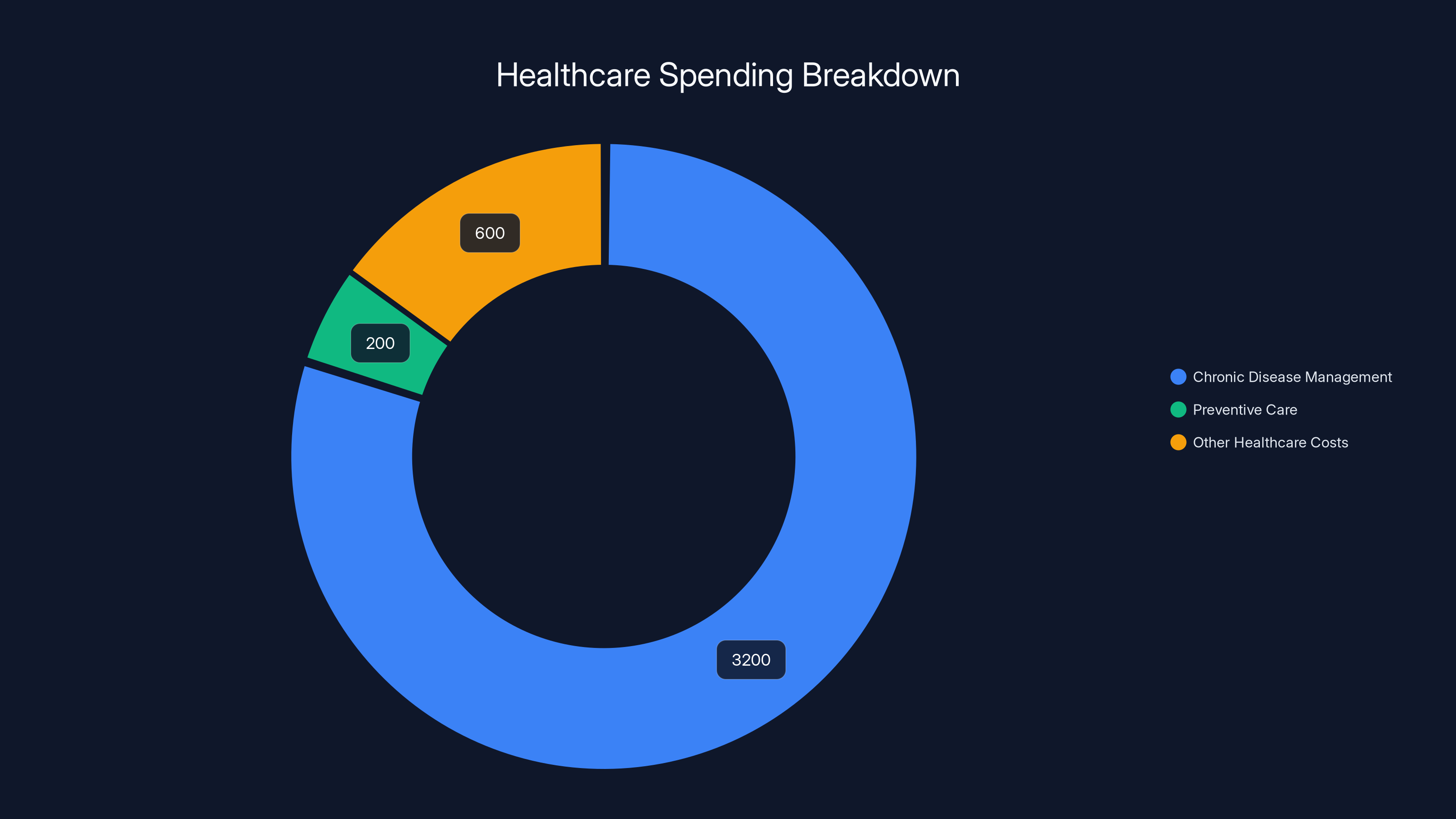

Chronic disease management dominates US healthcare spending, highlighting the potential for preventive care to reduce costs. Estimated data.

The Team Behind the Vision: Park and Friedman's Track Record

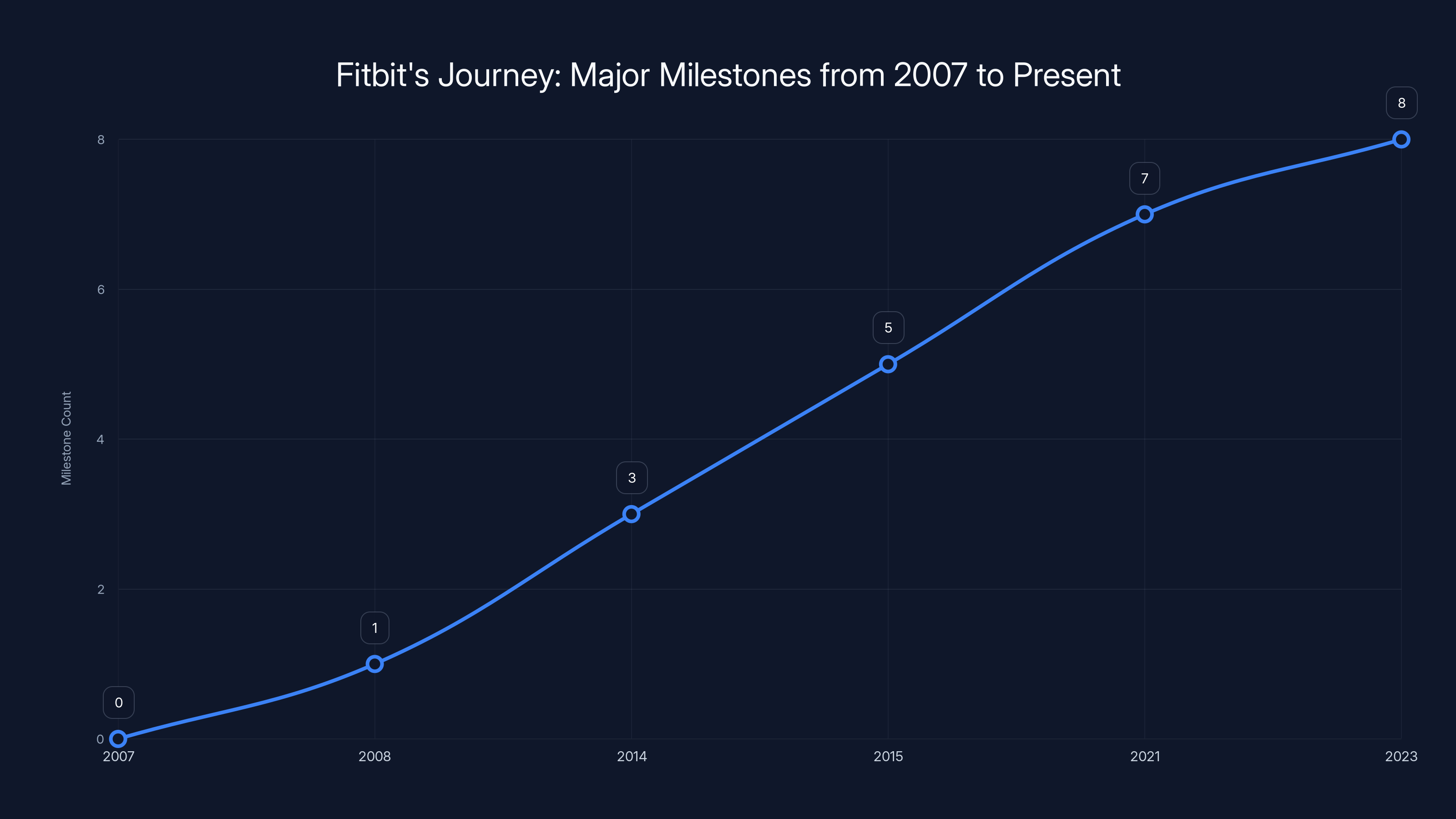

James Park and Eric Friedman aren't random entrepreneurs trying to catch a wave. They're the people who convinced the world that ordinary people wanted to track their fitness data. Remember 2008? Fitness tracking wasn't a thing. The Apple Watch didn't exist. Smartwatches were toys. Fitbit changed that perception.

They did it by understanding a fundamental truth: people want to understand their bodies. Not because they're vain. Not because they're obsessed with optimization. But because health data creates a bridge between intentions and reality.

You intend to exercise more. But intentions are vague. You don't notice incremental progress. A fitness tracker makes that progress visible. Same with sleep. You think you sleep enough. But when you see the data, you realize you don't. That gap between perception and reality is where behavior change happens.

Park and Friedman understood that better than anyone in the space. Google paid them $2.1 billion for that understanding. Then Google promptly failed to execute on the Fitbit vision, letting the brand stagnate while Apple dominated the market.

That failure might be the founders' greatest advantage now. They have capital, credibility, and most importantly: freedom. They're not building inside a megacorp's constraints. They're not optimizing for advertising revenue like Google would. They're not building for shareholders who demand immediate hockey-stick growth like a venture-backed startup might.

If they've structured this right, they're building the product they want to build. For the market they understand.

Privacy and Data Security: The Make-or-Break Factor

Let's address the obvious concern: who controls family health data, and what happens to it?

This is where the founders either build something transformative or replicate the mistakes of every other health tech company. Health data is extraordinarily sensitive. Genetic information, mental health indicators, medication history, weight trends—this data, if misused, can be weaponized against you. Insurance companies could use it to deny coverage. Employers could use it to discriminate. Governments in some countries could use it for surveillance.

The platform's entire value proposition depends on getting privacy right. Not just technically right, but philosophically right.

What I'd watch for:

End-to-end encryption by default. Data should be encrypted on the device before leaving it. Not encrypted in transit and decrypted on servers. That's theater. Real encryption means even the company can't read your data without your key.

Granular permission controls. Not just "share with family members." But "show Mom my heart rate but not my weight." "Share kids' school day activity but not evening location." Permission controls should be Byzantine in their detail.

Data minimization. Collect only what's necessary. Not "we can collect this, so we will." That's the Google approach. The better approach is "we need this specific data to deliver this specific insight, and here's why."

Transparent data handling. Where does data live? Can you request deletion? Can you download everything? Can you port to a competing service? These should be features, not legal negotiations.

Independent audits. The company should invite third-party security researchers to test the system continuously. Bug bounty programs. Public security assessments. Transparency reports about data requests from authorities.

If they nail this, they've built something genuinely valuable. If they compromise, they've built another Facebook-for-health that will eventually face regulatory backlash.

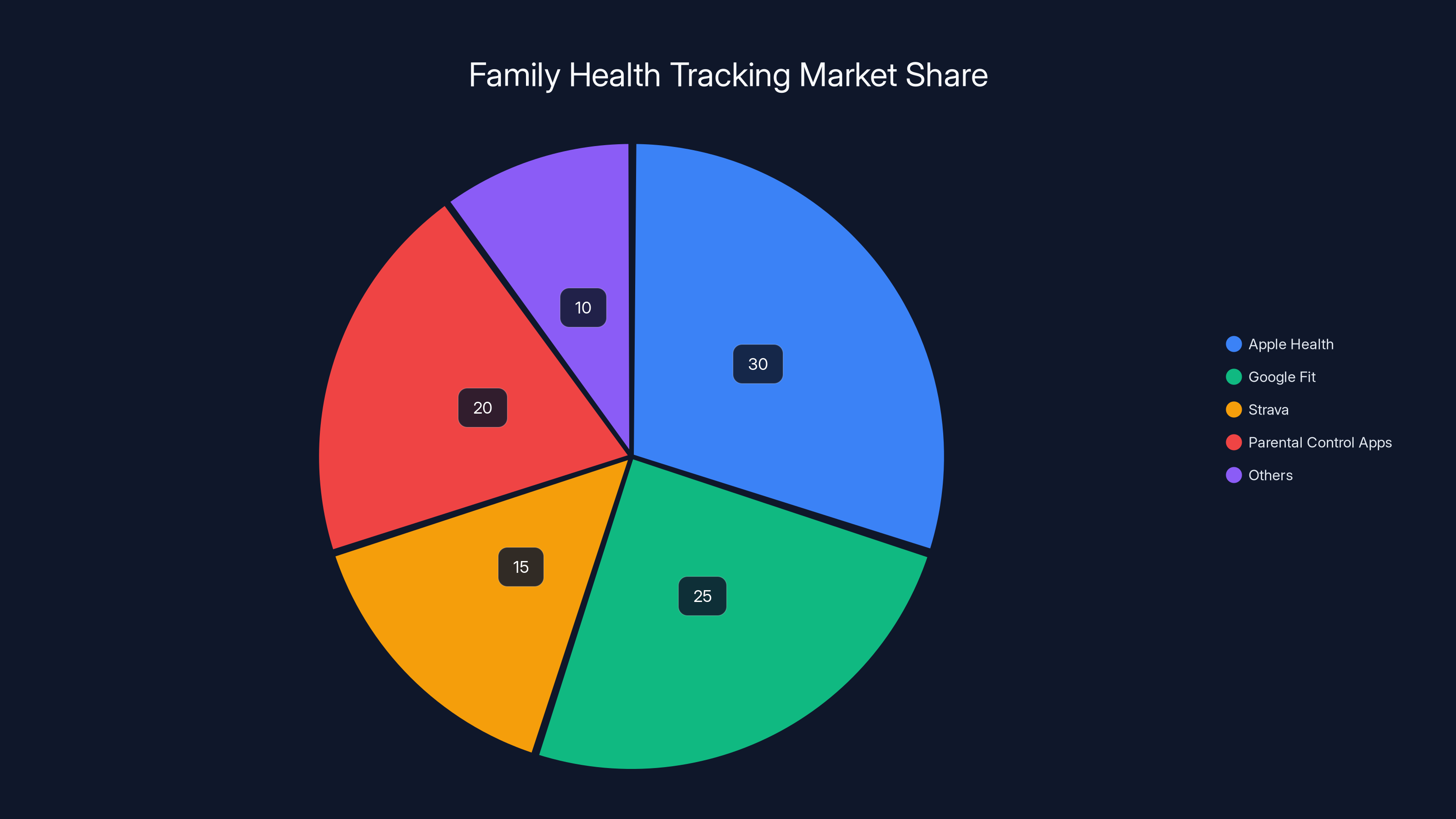

Estimated data shows Apple Health and Google Fit leading the family health tracking market, but the segment remains fragmented with no dominant integrated solution.

The Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Trying This

They're not entering an empty market. Several players are already positioning themselves as family health platforms.

Apple's approach: Apple Health aggregates data from your devices and family members' devices through the Health app and iCloud. The advantage is seamless integration if you're already in the Apple ecosystem. The disadvantage is it's designed for Apple's profit, not pure health optimization. Apple doesn't have strong incentives to make their health features better if they're already selling you the hardware.

Google Fit's strategy: Similar to Apple, but fragmented across Android devices. Google's traditional advantage is data science and machine learning. Their disadvantage is privacy concerns—Google's business model is fundamentally tied to data collection for advertising.

Specialized platforms: Companies like MyFitnessPal, Cronometer, and Strava focus on specific aspects (calorie tracking, nutrition, activity sharing) but don't really address family health holistically.

Healthcare organizations: Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, and others offer digital health platforms. But these are primarily for patients with existing conditions, not for families managing preventive health.

The gap Park and Friedman are targeting is real. Nobody's built a consumer-focused, privacy-first, genuinely family-oriented health platform. Apple and Google have too many conflicting business interests. Specialized apps are too narrow. Healthcare platforms are too clinical.

The Monetization Question: How Does This Actually Make Money

This is crucial because it reveals whether they'll stay true to privacy principles or eventually compromise them for revenue.

Possible models:

Subscription revenue: Premium tier with advanced insights, historical data, priority support. Free tier with basic tracking. This aligns incentives well—the company makes more money when users find more value, not when advertisers pay for attention.

Integration marketplace: Third-party apps can integrate with the platform. Think of it like Zapier but for health data. Developers build nutrition apps, mental health tools, medical devices that plug into the platform. The company takes a small cut. This is actually brilliant because it monetizes without touching user data.

White-label solutions: Employers, insurance companies, healthcare providers pay to offer the platform to their communities. The platform handles the infrastructure while partners customize the experience for their needs.

Anonymized research access: Researchers pay for anonymized, aggregated health insights. "What's the relationship between work hours and sleep quality?" "Do families who exercise together have better health outcomes?" This could be a significant revenue stream without compromising individual privacy if done right.

Device partnerships: Don't build hardware. Partner with device manufacturers. Every Oura Ring, every Garmin, every Apple Watch that syncs with the platform represents partnership revenue.

The monetization model matters because it determines whether the company stays aligned with user interests. If they make money from subscriptions and partnerships, they want a loyal, trusting user base. If they make money from selling user data or advertising, they're incentivized to eventually compromise privacy.

The founders' track record suggests they understand this. But follow the money. Always follow the money.

Fitbit's journey from inception to present includes key milestones such as their market entry, IPO, acquisition by Google, and subsequent market challenges. Estimated data.

Real-World Use Cases: Where This Platform Creates Value

Let me paint some scenarios where this actually matters:

Scenario one: Managing a parent's aging. Your father lives independently 50 miles away. You're not close enough to notice changes, but you're responsible enough to care. A family health platform lets you see his activity patterns, sleep quality, and heart rate variability without asking him daily "how are you feeling?" A significant drop in walking speed (measured by his watch) might indicate pain or illness. Early detection changes outcomes. This isn't surveillance. This is love at a distance.

Scenario two: Supporting a teenager's athletic performance. Your kid plays competitive soccer. The platform could show how sleep quality affects game performance. How hydration impacts recovery. How training load compares to actual recovery capacity. Not to push harder, but to optimize intelligently. Help them understand their body. That's genuinely useful.

Scenario three: Coordinating family fitness. Your family decides to get healthier together. The platform makes challenges fun and actually competitive. Not in a toxic way, but in a "we're doing this together" way. Mom doesn't run. Dad hates weight training. Kids get bored easily. But together, as a unit tracking collective movement? That changes motivation.

Scenario four: Catching health problems early. Your daughter suddenly stops sleeping well and her activity drops 30%. Before, you wouldn't notice for weeks. With data, you notice in days. You ask her about it. Turns out she's struggling with anxiety. Early intervention changes the trajectory. Data enables conversations.

Scenario five: Managing multiple chronic conditions. Your family has someone with diabetes, someone with hypertension, someone with arthritis. The platform isn't replacing medical care, but it's giving each person personalized context about what their data means. How their medication affects sleep. How their diet affects blood sugar. How their activity affects joint pain. Data transforms passive monitoring into active understanding.

These aren't hypothetical. These are real problems families face every day. And the existing tools don't solve them well.

The Technical Challenge: Building for Interoperability

Here's what makes this genuinely hard technically: they need to work with devices they don't control.

Your Apple Watch uses one protocol. Your Fitbit uses another. Your Garmin uses a third. Your pet's tracking collar uses a fourth. Your scale is Wi-Fi enabled. Your blood pressure monitor is Bluetooth. Your thermometer is cloud-connected.

Aggregating data from all these sources without controlling the ecosystem is brutally difficult. Every manufacturer guards their data standards jealously. Every integration is a negotiation. Every connection point is a potential failure mode.

There are standards (Health Level Seven International, Continua Health Alliance protocols), but they're not universally adopted. And even when devices follow standards, the standards don't cover everything that matters.

One approach: rely on smartphone companions and cloud APIs. The Apple Watch data goes through Apple Health. You integrate with Apple Health's APIs. Same with Google Fit, Fitbit's API, Garmin's API, Oura's API, etc. This is the path Apple and Google have chosen.

The advantage: works with everything that has modern APIs.

The disadvantage: you're dependent on those companies' willingness to keep APIs stable and useful. Apple and Google could deprecate APIs to push their own integrations.

Alternative approach: build your own devices that talk to everything. Like how Fitbit did with smartphone apps early on—they built the Fitbit device, then created Android and iOS apps to sync the data. The company could build their own wearables and use standard protocols to connect with everything else.

But that requires manufacturing capability, supply chain management, and significant capital. And it's not clear that's their strategy.

Most likely: they'll start with API integrations to major platforms (Apple Health, Google Fit, Fitbit's platform, Garmin, Oura, etc.) and expand from there. It's messy, but it's achievable.

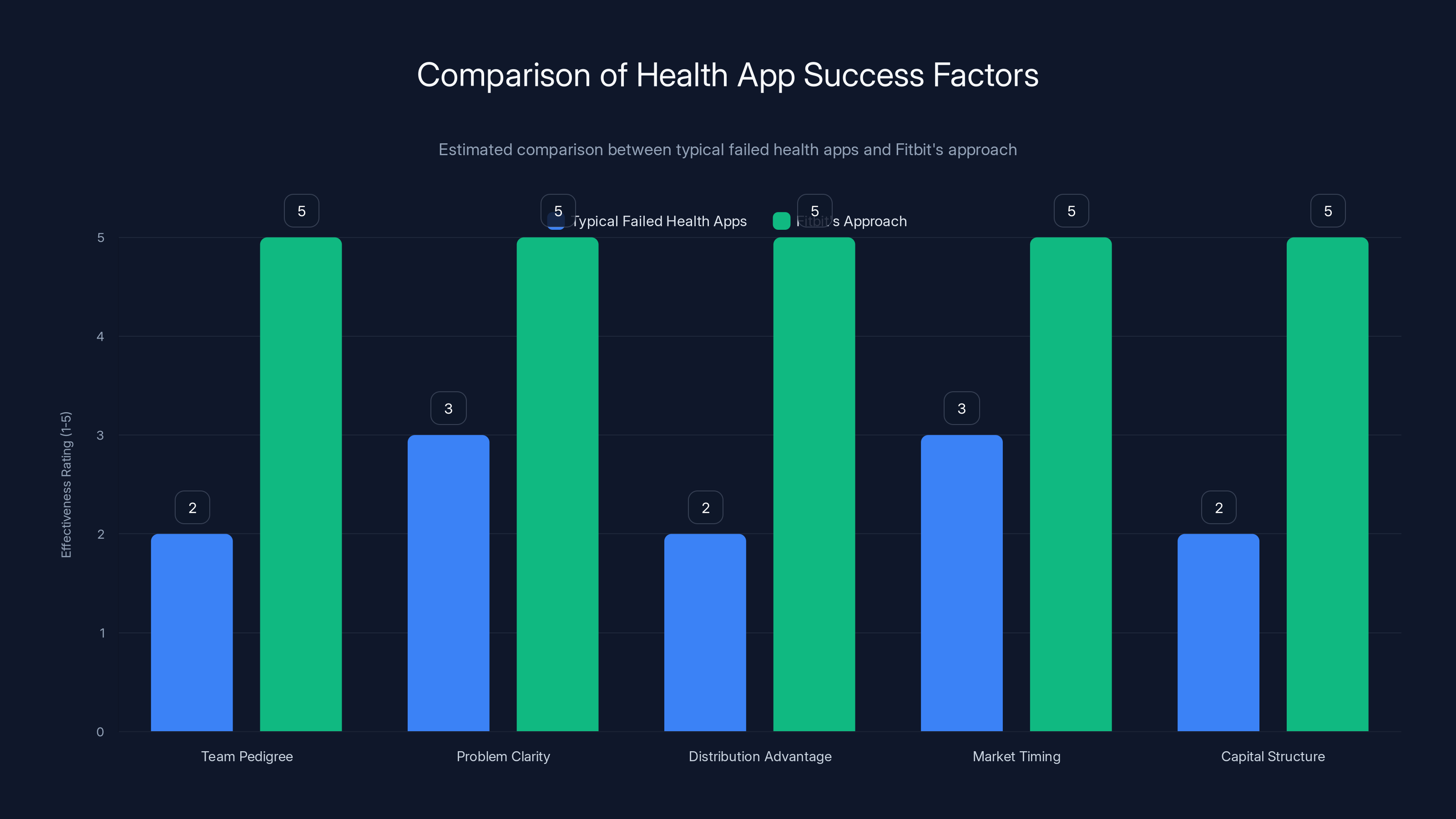

Fitbit's approach scores higher across key success factors compared to typical failed health apps, indicating a stronger foundation for success. (Estimated data)

The Regulatory Minefield: Healthcare or Just Software

This matters more than most people realize. If the platform makes health claims or provides health recommendations, regulatory agencies get involved.

In the US, that means the FDA has opinions. In Europe, it's GDPR and the Medical Devices Regulation. In other countries, it's their own versions of medical device oversight.

The question: is this a medical device or a health and wellness app?

If it's a medical device, it requires FDA clearance or approval, which takes years and costs millions. It means documentation, testing, clinical studies, manufacturing controls.

If it's just a wellness app that shows you your data without making medical claims, it's much lighter regulation—more like a social media platform.

Park and Friedman will likely position this as the latter. "We show you your data. We help you understand patterns. We don't diagnose. We don't treat. We don't claim medical benefit." That keeps regulatory burden low.

But there's tension here. The more useful the platform becomes at actually improving health outcomes, the more regulators will argue it's making medical claims. So there's an incentive to stay just vague enough to avoid regulation, which paradoxically limits how good the product can be.

This is why most health tech companies struggle—they're caught between two poles. Either they stay simple enough to avoid regulation (limiting usefulness), or they make health claims and take on significant regulatory burden.

The exception: companies deeply embedded in the healthcare system (like CVS with their minute clinics buying health tech). They have existing regulatory relationships.

For a consumer-focused platform, the safest approach is clear: collect data, show it to people, let them and their doctors interpret it. Don't make medical recommendations. That avoids the worst regulatory issues while still delivering value.

The Network Effect: When More Users Actually Make It Better

Here's why the founders' team matters. In a social network, value increases with users. More friends = more value. Same with health platforms, but in subtler ways.

Comparison data: The platform becomes more useful when you can compare your health metrics against relevant peers. "How does my sleep compare to others my age? Other parents? Other athletes?" Anonymous aggregates of comparable people create context.

Research insights: The more families using the platform, the more data exists to answer questions. "What's the relationship between children's sleep and parents' stress levels?" "Do families with shared fitness goals have better health outcomes?" These insights only emerge at scale.

Algorithm improvement: Machine learning models improve with more data. The platform's recommendations get smarter as more families use it and provide feedback about what actually works.

Integration momentum: When enough people use a platform, more device manufacturers and app developers build integrations. It becomes the de facto standard, which attracts more users.

But—and this is critical—the network effect only works if the platform is genuinely useful and trustworthy. If people feel surveilled or manipulated, the network effect becomes a liability. Everyone knows that their data is in a system they don't trust. That's actually worse than no network.

So the founders have a choice: build a smaller, tightly controlled community around strong privacy principles, or build a massive platform that inevitably makes compromises. History suggests smaller, principle-driven communities are more sustainable. But they don't scale as fast.

Timeline and Realistic Expectations

If they're launching now (late 2024/early 2025), here's what to expect realistically:

Next 6 months: Beta with invited users. Focus on core functionality: data aggregation from major platforms, family dashboard, basic insights. The product will feel rough. That's normal. They're learning what people actually want.

Months 6-12: Public launch with limited device support (probably Apple Watch, Fitbit, Google Fit primary). Android and iOS apps. Pairing mechanism to add family members. The experience will still be basic, but functional.

Year 2: Integration expansion. More device support. More detailed insights. Probably the first paid tier launches. Pet health tracking probably enters public beta if it's not already available.

Year 3: Either they've found product-market fit and are scaling toward profitability, or they've pivoted. No in-between. Either people genuinely want this, or they don't.

This timeline assumes they're well-funded (which they probably are—founders backing founders usually means serious capital). It assumes a small, focused team (probably 20-40 engineers initially, not 200). And it assumes they're willing to stay private for a few years rather than rushing to venture funding and IPO timelines.

The bet: that by year 3, family health tracking is obvious enough that competitors copy it, and they've built enough brand and data momentum that they become the default for that use case.

That's a reasonable bet. Different from Fitbit's original bet (making fitness tracking mainstream), but reasonable.

What Could Go Wrong: The Honest Assessment

I've been fairly positive about this venture, so let me be explicitly pessimistic for a moment.

Execution risk is real. Just because they founded Fitbit doesn't mean they'll get this right. Fitbit succeeded 15 years ago in a totally different market. Markets change. Competition is fiercer. Technology is more mature and less forgiving of half-baked products.

Privacy is a slow burn, not a feature. Building strong privacy into a product makes it slightly harder to use initially. Users don't notice privacy working—they only notice when it fails. So there's pressure to compromise privacy for usability. History shows most companies eventually succumb to that pressure.

Family dynamics are harder to solve than individual fitness. Fitness tracking was always straightforward: more activity = good. Family health is political. Do parents have the right to monitor teenagers? When does monitoring become invasive? How do you balance everyone's autonomy with family oversight? These are hard problems with no universal answers.

Distribution advantage has shifted to platforms. When Fitbit launched, smartphones were new. Getting users was grassroots: early adopters bought the device, told their friends, it spread. Now, Apple and Google own the ecosystem. They can feature health tracking in iOS and Android updates overnight. Competing against platform advantage from tech giants is brutally difficult.

Monetization without privacy compromise is hard. VCs will eventually ask: when does this profitably scale? Subscription revenue has limits. Partnership revenue requires giving partners access to data. At some point, the pressure to monetize data intensifies. Whether the founders can resist that pressure is an open question.

Regulatory uncertainty. Healthcare regulation is unpredictable and expensive. One FDA interpretation or GDPR enforcement action could completely change the unit economics.

These aren't reasons to dismiss the venture. They're reasons to be realistic about the odds. Probably 20-30% chance this becomes a significant player in family health. 70-80% chance it becomes a useful tool for a niche audience, then either stays small, pivots, or gets acquired.

The Bigger Picture: Family Health as a Category

Zoom out for a moment. Is family health tracking actually going to be a big market? Or is this solving for a problem that only exists in tech founder minds?

Here's the data: healthcare spending in developed countries is approaching 20% of GDP. Most of that spending is reactive (treating illness) rather than preventive (avoiding illness). Preventive care is genuinely underfunded. And family health—managing health across generations—is probably the least addressed gap.

Consider: the US spends $4 trillion annually on healthcare. About 80% of that goes to managing chronic diseases that could be prevented or delayed with better lifestyle choices. The lever points are clear: sleep, activity, nutrition, stress, social connection. These are family-level problems. Your sleep affects your partner's sleep, which affects your kid's morning mood, which affects their school performance.

But there's no system to manage health at the family level. You manage your individual health (maybe), and if you're lucky, your doctor manages one specific condition. Nobody's optimizing for family health systems.

If someone built a system that shifted just 5% of healthcare spending toward prevention through better family health management, that's

So yes, the market is real. The question is whether this specific team can capture it.

For the Skeptics: Why This Is Different

You might be thinking: "Health apps fail all the time. Why is this different?"

Good question. Here's why:

Team pedigree. Park and Friedman didn't just run Fitbit. They built the category. They understand consumer health behavior deeply. That's rare.

Problem clarity. They're not trying to solve everything. They're specifically solving "how do we give families visibility into collective health?" That's focused and achievable.

Distribution advantage. They don't need to convince manufacturers to build hardware—they integrate with existing devices. They don't need to convince healthcare systems to adopt their platform—they work directly with consumers. They're not fighting distribution battles; they're working with existing distribution.

Timing. The market is finally ready. Five years ago, nobody had enough wearables for family tracking to work. Now, most affluent families have multiple devices. The data infrastructure exists. The timing is right.

Private capital structure. They're not venture-backed (presumably). That means they're not under pressure to hockey-stick growth or face a Series C crunch. They can build sustainably for five years if needed.

These aren't guarantees. But they're reasons to take the bet seriously.

What Users Should Watch For

If you're considering this platform once it launches, here's what matters:

Privacy policy clarity. Read it. Specifically: who owns your data? Can you delete it? Can you port it? Is it encrypted by default? Is end-to-end encryption available? If the answers are unclear or evasive, don't use it.

Data minimization. Does the app ask for permissions it doesn't need? Does it collect data points you didn't authorize? Does it use location when it shouldn't? These are red flags.

Transparency reports. Does the company publish transparency reports about government data requests? Do they report security incidents publicly? Transparency is a signal of trustworthiness.

Integration security. How securely does it handle connections to other platforms? Does it store your device API keys securely? This matters because it's a potential attack vector.

Insights accuracy. When the platform makes recommendations, are they evidence-based? Or are they marketing-focused guesses? Early users should monitor whether insights match reality.

User control. Can you control exactly what data each family member sees? Or is it all-or-nothing? Granular control is essential for families.

Support quality. When something breaks, how responsive is the company? Health data systems need good support.

These aren't exotic requirements. They're baseline expectations for any health data system. If the company can't meet them, don't use it.

The Verdict: Worth Paying Attention To

Will this platform revolutionize healthcare? Probably not. Will it become a category leader in family health? Maybe. Will it be useful for some families? Almost certainly.

The more interesting question: what does this venture signal about where the market's going?

It signals that single-person health optimization is mattering less than collective family health. It signals that the next wave of consumer health innovation is about systems, not devices. It signals that founders still see massive untapped opportunities in wellness, even after Google's $2.1 billion acquisition.

That's the real story. Not whether this specific product succeeds, but what it says about the future of health technology.

If the team executes well and maintains their privacy-first principles, they could genuinely build something important. If they compromise—like most health tech companies eventually do—they'll become another data-harvesting platform with good intentions.

I'm betting they'll execute well. But I'm watching the money. Always watch the money.

FAQ

What is family health tracking and how does it differ from personal fitness tracking?

Family health tracking monitors the wellness metrics of multiple household members—adults, children, elderly relatives, and even pets—through a unified platform. Unlike personal fitness tracking, which focuses on individual optimization metrics like daily steps or workout performance, family health tracking emphasizes collective wellness patterns and cross-member health correlations. It's designed to provide oversight without surveillance, helping families understand how one member's health impacts others (like how parents' stress affects children's sleep) while respecting individual privacy boundaries.

How do the Fitbit founders' previous experience inform their new venture?

James Park and Eric Friedman founded Fitbit in 2007 and grew it from a startup into a billion-dollar company before Google's acquisition for $2.1 billion in 2021. Their track record demonstrates deep understanding of consumer health behavior, the ability to make fitness tracking mainstream when it seemed like a niche product, and successful navigation of the hardware-software ecosystem. They've learned from watching Google's struggles with the Fitbit brand post-acquisition, giving them insights into what not to do and where genuine market opportunities exist in family health systems.

What privacy safeguards should a family health platform have?

A trustworthy family health platform should implement end-to-end encryption by default, granular permission controls allowing individual members to control what specific data they share, transparent data handling practices (including download and deletion capabilities), and independent security audits. The company should publish transparency reports about government data requests, use data minimization practices (collecting only essential information), and make it clear they're not selling or sharing data for advertising purposes. Strong privacy practices are essential because health data can be misused by insurance companies, employers, or governments if compromised.

How would this platform aggregate data from different manufacturers' devices?

The platform would likely work through existing APIs and cloud services from major manufacturers. Instead of directly connecting to individual devices, it integrates with Apple Health, Google Fit, Fitbit's ecosystem, Garmin's platforms, and other standard health data services where your devices already sync their information. This approach requires negotiating with device manufacturers and maintaining multiple integrations as standards evolve, but it avoids the need to build competing hardware and works with devices users already own.

What are the realistic revenue models for family health platforms without compromising user privacy?

Sustainable revenue models include subscription services offering premium features and deeper insights, integration marketplaces where third-party developers build apps that connect to the platform, white-label solutions for employers and healthcare providers, anonymized aggregated research access for medical researchers, and device partnership programs. The key is that these models generate revenue without requiring user data to be sold to advertisers or data brokers, maintaining alignment between the company's financial interests and user privacy interests.

Why would anyone want to track their pet's health data?

Pet health monitoring enables early detection of illness (animals show symptoms late), helps optimize veterinary care, identifies patterns in activity and behavior that might indicate pain or stress, and tracks age-related changes. Since pets can't verbally communicate their conditions, data about movement, eating, and sleep patterns provides crucial insights. Pet health is also emotionally different from human health tracking—it's pure care without self-judgment concerns, which changes how people engage with the feature.

What regulatory challenges does a family health platform face?

The primary regulatory question is whether the platform qualifies as a medical device (requiring FDA approval in the US, CE marking in Europe) or remains a consumer wellness app with lighter regulation. By positioning itself as a data display and pattern recognition tool rather than a diagnostic or treatment system, the platform can avoid the most burdensome regulations. However, if it makes health claims or provides specific health recommendations, regulatory agencies may argue it crosses into medical device territory, requiring clinical studies and formal approval processes.

How could this platform create meaningful family health improvements?

Practical benefits include early detection of health problems through behavioral pattern changes, coordination of family fitness goals for collective motivation, support for aging parents through distance monitoring, optimization of training and recovery for athletic family members, and better management of chronic conditions across multiple family members. The platform enables conversations—when data shows unusual changes, families can discuss what's happening earlier than they would through casual observation alone.

What is the realistic timeline for market adoption?

If launching in early 2025, expect beta testing during the first six months, public launch with limited device support by mid-2025, expanded integrations and first paid tier by year-end, and critical evaluation of product-market fit by year two. The question of success won't be answered quickly—building a new category takes time. The platform likely won't be a household name within two years, but it should have demonstrated clear value to early adopters and attracted competitive responses from larger technology companies if the concept proves viable.

Why haven't tech giants like Apple or Google built comprehensive family health platforms already?

Both Apple and Google have conflicting business interests. Apple prioritizes hardware sales and premium service subscriptions, limiting how family-friendly they can make the experience without cannibalizing device sales. Google's core business model depends on data collection and advertising, creating fundamental privacy concerns that conflict with health data sensitivity. Neither company benefits from solving family health holistically if it doesn't increase hardware sales or advertising value. A purpose-built platform without these conflicting incentives can potentially execute family health better, even if it operates at a smaller scale.

Conclusion: The Future of Family Wellness

The fact that Fitbit's founders are launching a new venture in family health tracking signals something important about where the wellness market is heading. We've reached a point where individual health optimization is table stakes. Everyone's already tracking their steps. The next frontier is collective, integrated, family-level wellness.

This isn't just about adding more data points. It's about fundamentally changing how families understand and manage their health as a system. Your sleep affects your partner's alertness, which affects their parenting, which affects your kid's mood and behavior, which affects their performance at school, which cycles back to your stress level. These connections are real. Nobody's systematically optimizing for them because the infrastructure hasn't existed.

Park and Friedman are trying to build that infrastructure. The odds of success are genuinely uncertain. Many smart people have tried to build health platforms and failed. The regulatory environment is unpredictable. Distribution disadvantages relative to platform giants are real. Privacy maintenance under scaling pressure is notoriously difficult.

But if anyone in the consumer health space has the credibility, experience, and focus to pull this off, it's probably the Fitbit founders. They've done harder things before in less favorable market conditions.

The platform likely won't transform healthcare completely. That requires changes far beyond consumer apps—changes in medical education, insurance incentives, workplace culture, and public health policy. But it could move the needle on family health outcomes by giving families better visibility and coordination around collective wellness.

For now, the play is simple: watch how they handle privacy in the first year. Watch whether they maintain independence from venture capital pressures. Watch whether the product actually solves real family problems or remains a novelty for early adopters. Watch whether they can maintain the integrity of their vision as they scale.

That's where the real test lies. Not in the technology, but in whether they can build something trustworthy at scale. In tech, that's the hardest problem of all.

Key Takeaways

- Fitbit founders Park and Friedman are launching a family-wide health tracking platform that aggregates data across multiple users and devices, addressing a significant market gap in family health optimization

- The platform will integrate with existing wearables (Apple Watch, Fitbit, Garmin) rather than require proprietary hardware, making it technically complex but strategically sound in avoiding hardware competition

- Privacy and data security are existential to the platform's success—any compromise will erode the trust required for families to share sensitive health information across generations

- Pet health tracking is an unexpected but clever differentiator that expands the addressable market beyond fitness enthusiasts to general pet owners and provides cleaner data for algorithm training

- Success requires navigating competing interests from tech giants (Apple, Google), regulatory uncertainty, and the fundamental challenge of maintaining privacy-first principles while scaling to profitability

Related Articles

- Luffu: The AI Family Health Platform Fitbit Founders Built [2025]

- Luffu: The AI Family Health Platform from Fitbit's Founders [2025]

- Fitbit Google Account Migration: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Fitbit Google Account Migration: What You Need to Know [2026]

- Best Tech Valentine's Day Gifts for Your Partner [2025]

- Apple Watch Series 11: Complete Guide to the $299 Deal [2025]