Introduction: The Growing Crisis of Voice Assistant Privacy

You wake up in the morning, grab your phone, and don't recall saying "Hey Google." Yet your device might have been listening anyway.

This isn't paranoia. It's what happened to thousands of people who filed a class-action lawsuit against Google, claiming its voice assistant secretly recorded their conversations without permission and then shared that data with third parties for targeted advertising. The result? A $68 million settlement announced in January 2026 that Google agreed to pay, without admitting any wrongdoing.

But here's the thing that makes this case particularly fascinating: it exposes a fundamental problem with how voice assistants work. The issue isn't just about Google being careless. It's about the inherent difficulty of building a system that listens all the time while also respecting privacy. When you want a device to respond instantly to your wake word, you need it to continuously process audio. And that opens the door to mistakes.

The lawsuit centered on what engineers call "false accepts"—moments when Google Assistant activates and starts recording even though the user never said the wake word. Imagine you're having a private conversation with your partner, your kid says something that sounds vaguely like "Hey Google," and suddenly your device is capturing everything. That recording then gets transmitted to Google's servers, potentially shared with advertisers, and used to build a profile of your interests.

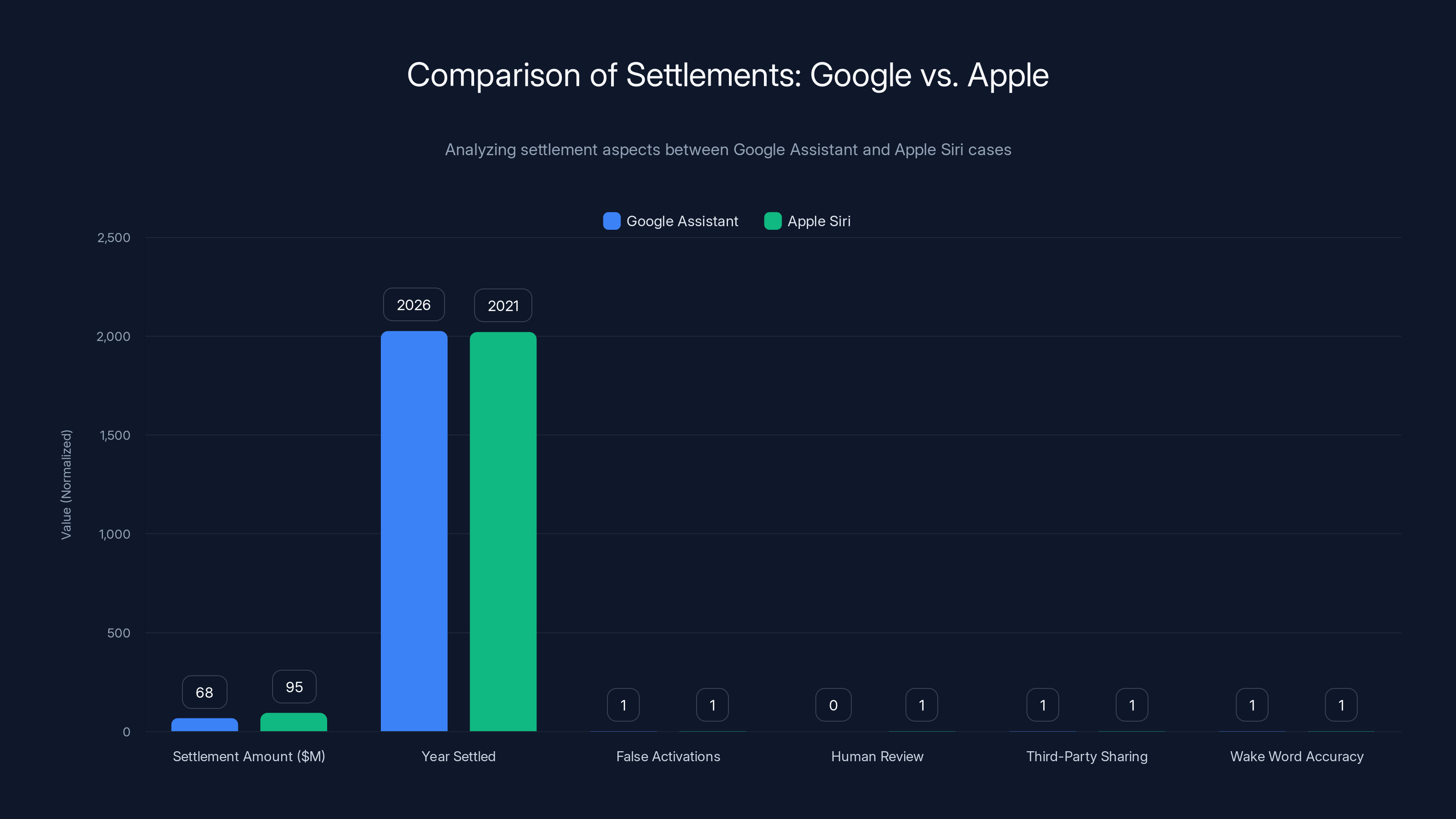

This settlement matters because it's part of a larger wave of privacy litigation hitting tech giants. Apple paid $95 million in 2021 for similar Siri violations. Amazon has faced comparable scrutiny over Alexa. These companies are learning an expensive lesson: consumers care about privacy, regulators care about enforcement, and juries are willing to hold companies accountable even when the violation feels technical rather than malicious.

In this article, we'll unpack what happened with Google Assistant, why false accepts occur, what the settlement actually covers, and what this means for the future of voice AI and privacy. We'll also explore the broader context of voice assistant surveillance and the steps you can take to protect your own data.

TL; DR

- Google paid $68 million to settle class-action claims that Google Assistant recorded users without consent through "false accepts"

- The core issue: Google Assistant sometimes activated and recorded conversations when users never said the wake word, then shared recordings with third parties for advertising

- No admission of wrongdoing: Google settled without acknowledging liability, a typical settlement structure in large tech litigation

- This follows Apple's $95 million Siri settlement in 2021 for similar unauthorized recordings

- Wake word activation remains an unsolved challenge in voice AI—perfectly distinguishing intentional commands from background noise at scale is technically harder than it seems

The

What Exactly Are "False Accepts" and Why Do They Happen?

Before diving into the lawsuit itself, you need to understand the technical problem that created it.

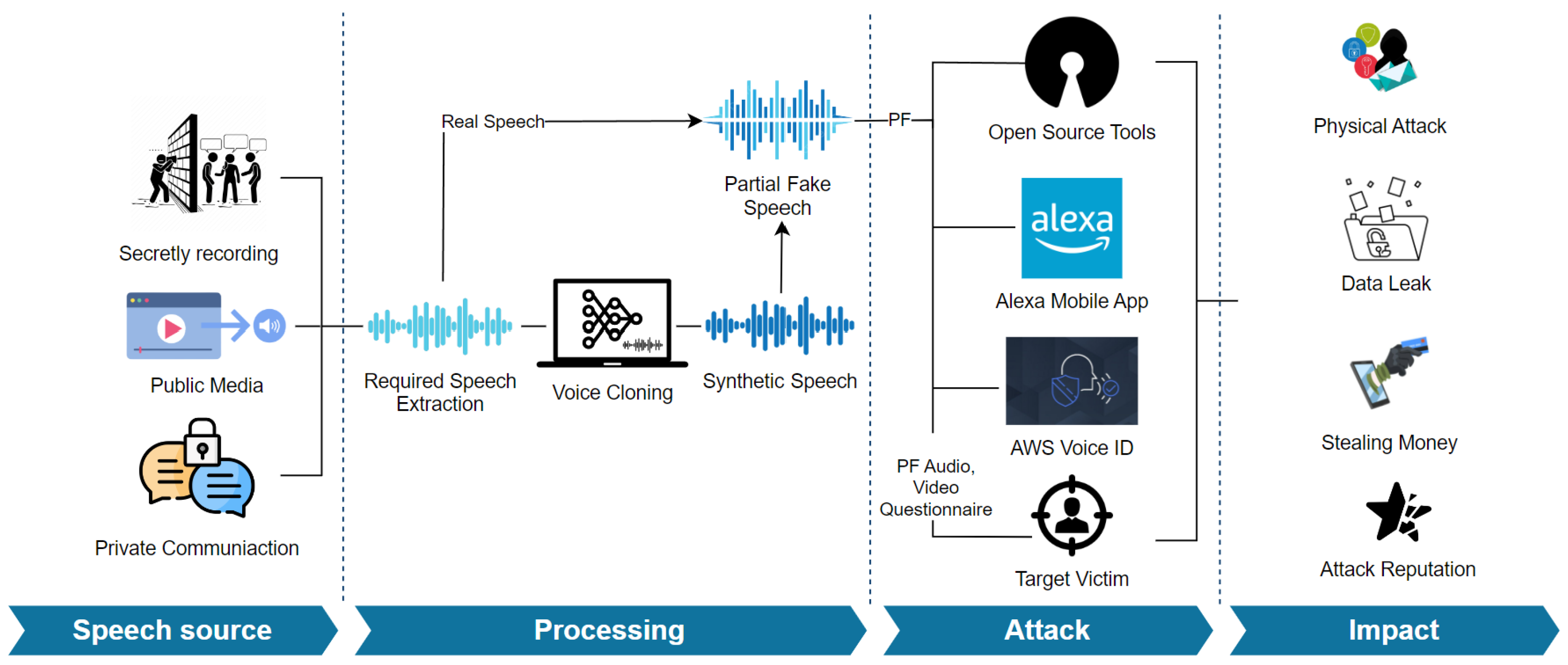

A wake word—the phrase like "Hey Google" or "Alexa"—is supposed to activate your device. The moment you say it, the device wakes up, starts recording, and sends that audio to the cloud for processing. The system then decides whether to execute your command or ignore it.

But here's where it gets complicated. Your device doesn't wait for perfect conditions. It has to listen constantly, using a specialized chip that stays powered while the rest of the device sleeps. This always-listening design is crucial because you want instant response times. You don't want to tap a button first and then say your command. You want to just speak naturally.

The problem is that this always-listening system has to make split-second decisions about whether someone said the wake word. It's using acoustic models trained on thousands of examples of people saying "Hey Google." But real-world audio is messy. Your partner might be talking on the phone. Your kid might be watching TV. Someone across the room might say something that phonetically resembles the wake word.

When the model gets confused and thinks it heard the wake word when it didn't, that's a false accept. The device wakes up, starts recording, and sends that audio to Google's servers. Multiply this across millions of devices, and you get a significant volume of unwanted recordings.

Google's own research teams have published papers on this exact challenge. The fundamental tension is between accuracy and responsiveness. Make the system more strict to reduce false accepts, and users have to speak more clearly and at higher volumes. Make it more permissive, and you capture more false positives.

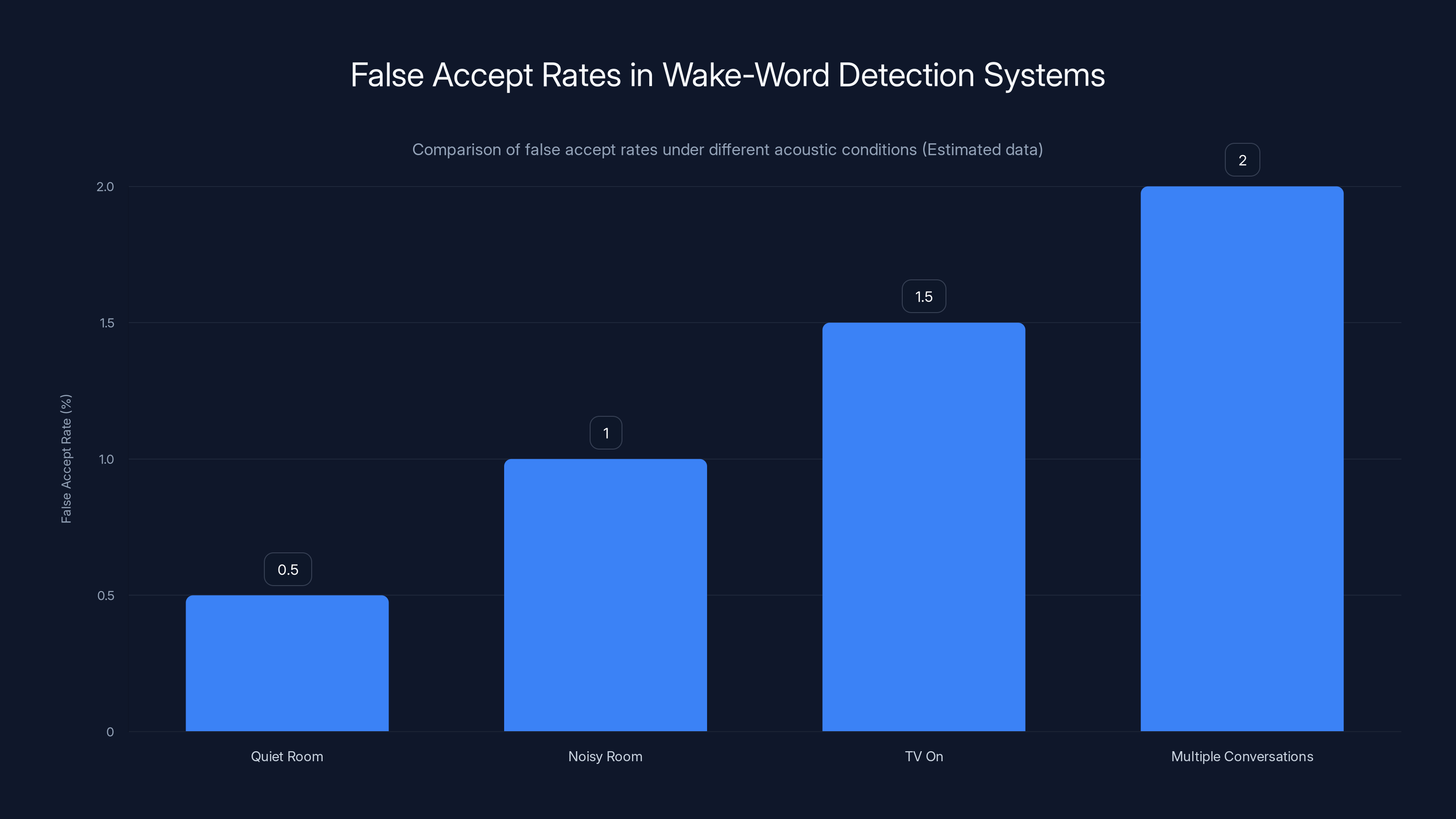

According to industry standards, even the best commercial wake-word detection systems have error rates between 0.5% and 2% depending on acoustic conditions. That might sound small, but when you're dealing with hundreds of millions of devices, even 1% error rate means millions of unauthorized recordings per month.

What made the Google case particularly serious wasn't just that false accepts happened. It was that Google allegedly knew about the problem, didn't adequately inform users, and then used the data from these false activations for commercial purposes like targeted advertising.

One plaintiff in the suit claimed they discovered Google had thousands of recordings of them that they never authorized. These recordings included private medical information, financial discussions, and intimate conversations. And Google had apparently used insights from this data to serve targeted ads.

Apple settled for

The Anatomy of the Class-Action Lawsuit

The lawsuit itself was framed as a privacy violation under California law and potentially federal wiretapping statutes. The plaintiffs made a straightforward argument: Google intentionally designed and deployed a system that intercepted and recorded private communications without consent.

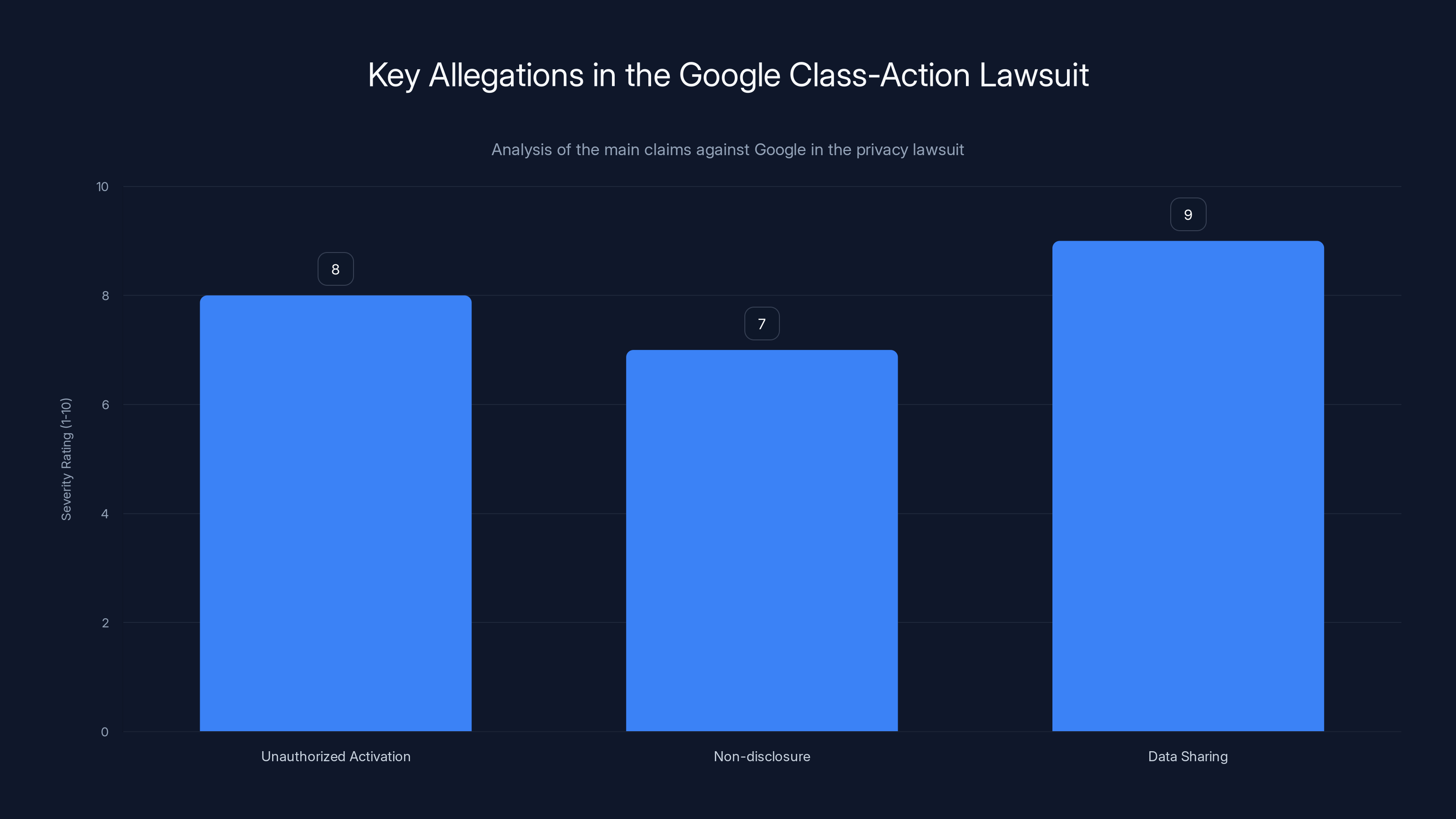

The legal claim centered on three main allegations. First, that Google Assistant was activating without wake words—the false accepts we discussed. Second, that Google was aware this was happening but didn't disclose it to users. Third, that Google was sharing the audio recordings and insights derived from them with third parties for advertising purposes without explicit consent.

What's interesting about this lawsuit is that it wasn't alleging that Google engineers were intentionally listening to you for blackmail material or espionage. The harm was more subtle and arguably more insidious: the casual use of private data for profit without permission.

California's privacy laws are among the strictest in the United States. Under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and related statutes, companies must disclose what data they collect, how they use it, and give consumers the right to delete it. The plaintiffs argued that Google's conduct violated these principles.

The federal angle involved wiretapping statutes that make it illegal to intercept communications without consent. These are serious criminal violations that can carry prison time. The civil case borrowed from this framework, treating the unauthorized recordings as unlawful interception.

Google's initial defense likely argued that:

- Users consented to Google Assistant's operation when they activated the device

- False accepts are inevitable in any acoustic system

- The data wasn't actually shared for advertising in violation of privacy laws

- Any misuse was incidental, not intentional

But rather than go to trial, Google settled. This is standard for tech companies facing privacy litigation. The settlement amount—

Comparing Google's Settlement to Apple's Siri Case

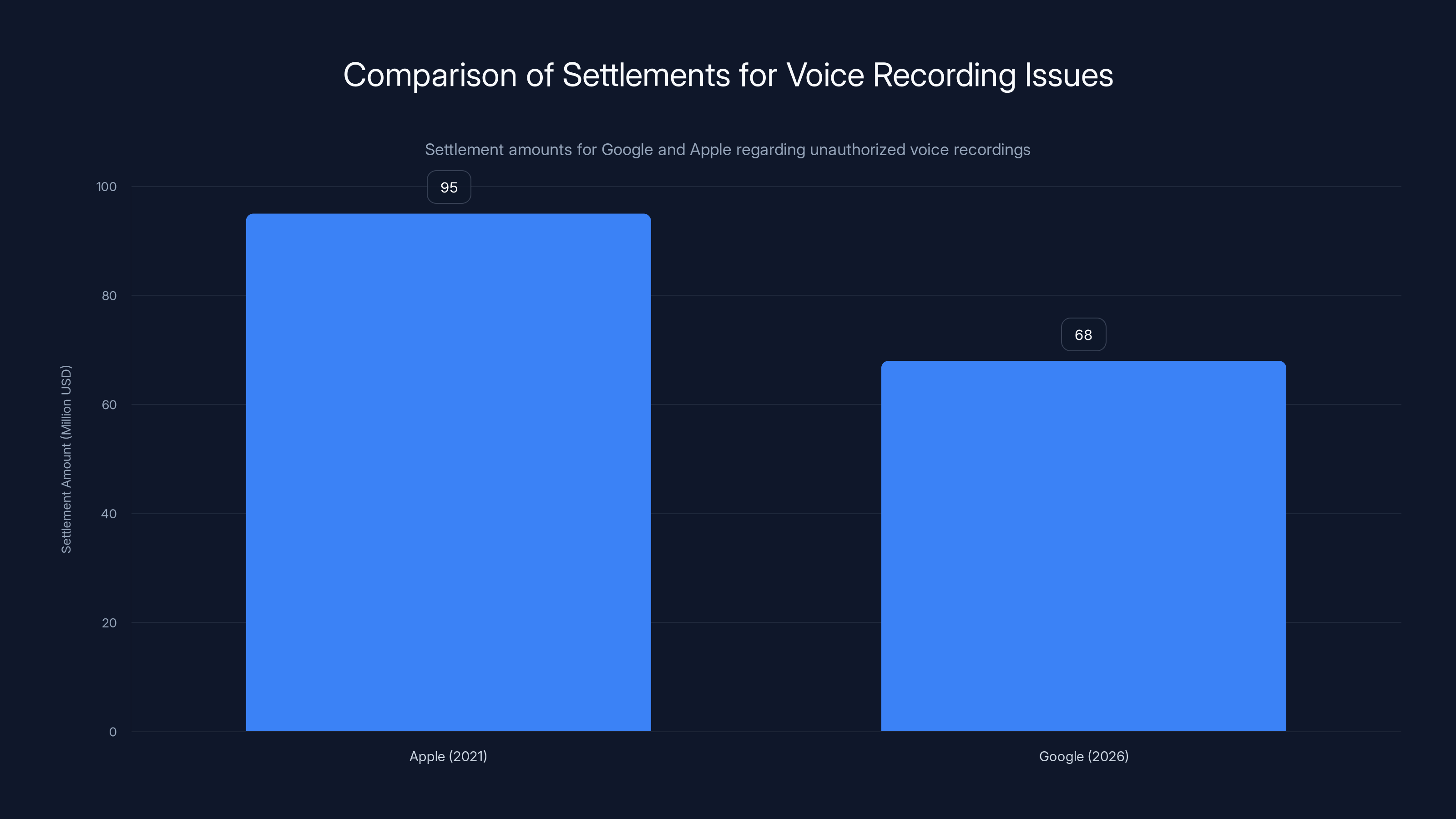

Google's $68 million settlement didn't happen in a vacuum. It followed a similar case against Apple, which had a troubling parallel problem with Siri.

In 2021, Apple agreed to pay $95 million to settle claims that Siri was recording users without their knowledge. Like Google Assistant, Siri was sometimes activating and recording conversations when the wake word ("Hey Siri") was never actually spoken.

The mechanics were similar too. Apple employees and contractors were tasked with listening to random Siri recordings to improve the system. They heard intimate conversations, medical information, and other private moments. When users found out that their recordings were being reviewed by humans, there was significant backlash.

Here's the comparative breakdown:

| Aspect | Google Assistant | Apple Siri |

|---|---|---|

| Settlement Amount | $68 million | $95 million |

| Year Settled | 2026 | 2021 |

| False Activations | Alleged systematic issue | Documented systematic issue |

| Human Review | Disputed | Confirmed by employees |

| Third-Party Sharing | For advertising | For contractors/QA teams |

| Wake Word Accuracy | ~1% false positive rate | Similar accuracy issues |

| Legal Jurisdiction | California class-action | Federal settlement |

The Apple settlement was actually larger, which is interesting because it might suggest that Apple's violation was considered more serious. Apple had explicitly stated that human contractors reviewed Siri recordings for quality assurance, but many users were unaware of this practice. When it became public, it generated significant controversy.

Google's case involves a different dynamic. Rather than intentional human review, the concern is that machine learning systems are using false accept recordings to train advertising models. This is arguably more automated and systematic, which might explain why the settlement amount is lower despite the similarities.

Both settlements establish an important precedent: voice assistant companies will be held financially liable for privacy violations, even if they can avoid admitting wrongdoing.

The lawsuit against Google highlighted three main allegations, with data sharing without consent rated as the most severe. Estimated data.

The Economics of Data Collection and Targeted Advertising

Underlying this entire lawsuit is an economic tension at the heart of modern tech companies: free services funded by advertising.

Google Assistant is free. Most users never pay a penny to use it. Instead, they pay with data. Every search you perform, every voice command you issue, every song you ask Alexa to play generates data that companies use to build profiles about you.

These profiles are incredibly valuable. Knowing that you're interested in fitness equipment, weight loss supplements, and running shoes allows advertisers to show you highly targeted ads. That targeting capability justifies the price of placing ads. An advertiser might pay

The more data companies have, the better they can target, the more they can charge advertisers, and the more profitable they become.

False accept recordings fit into this economy by accident. Google wasn't intentionally recording people to build better advertising profiles. But when false accepts did happen, Google apparently didn't delete the recordings. Instead, the machine learning systems that power advertising targeting learned from them.

Imagine you have a conversation with your partner about your knee pain. Your device falsely activates and captures this. Google's systems then use this recording to identify you as someone interested in orthopedic care. Suddenly, you start seeing ads for knee braces, physical therapy, and pain relief products. You never opted in, but you're now being tracked and profiled.

The economics work like this:

Where targeting precision is directly correlated with data accuracy and volume. More data, more accurate profile, more valuable user to advertisers.

Google's business model basically inverts the traditional relationship between customer and company. Advertisers are the customers paying for the service. Users are the product being analyzed and targeted. This model works well when users understand and accept the trade-off. It becomes problematic when users don't know what data is being collected.

The settlement implicitly recognizes this imbalance. The plaintiffs were arguing that Google was collecting data without informed consent and using it for financial gain. Even though Google didn't admit wrongdoing, paying $68 million signals that the company acknowledges the conduct was at minimum questionable.

Timeline of Voice Assistant Privacy Issues

Google Assistant's false accept problem didn't appear overnight. It's been an issue for years, gradually uncovered through reporting and independent research.

Around 2017-2018, journalists and academics started publishing research showing that voice assistants were experiencing false activations. Amazon's Alexa was captured in recordings of TV shows and news broadcasts about crime, activating and recording in response to words that sounded similar to "Alexa."

Google started facing specific criticism around 2019-2020 when multiple news outlets reported that Google Assistant was recording fragments of conversations that didn't include the wake word. Some of these recordings were extremely sensitive—medical information, intimate moments, financial discussions.

By 2021, the Siri settlement put pressure on Google to address similar issues with its own assistant. But instead of proactively disclosing and fixing the problem, Google apparently continued deploying the same systems, hoping the issue wouldn't face legal scrutiny.

The class-action lawsuit was filed sometime after 2021 (the exact date isn't specified in available reports, but the settlement was announced in January 2026). This suggests a multi-year legal process, which is normal for complex litigation involving millions of potential class members.

What's notable is that even after the Apple settlement, Google apparently didn't substantially change its practices regarding false accept recordings. This suggests either:

- The technical problem was harder to solve than expected

- The economic incentives to continue using all available data were stronger than the reputational risk

- Leadership didn't believe they'd face similar legal jeopardy

All three are probably partially true.

From a technical perspective, improving wake-word accuracy while maintaining responsiveness is genuinely difficult. Google has invested heavily in acoustic research but still hasn't solved the false accept problem completely. Every improvement in false accept rates seems to come with trade-offs in response time or robustness to accents and speech patterns.

From an economic perspective, every piece of data contributes to advertising targeting. Deleting false accept recordings would mean discarding potentially valuable signal. That creates pressure against aggressive privacy practices.

From a legal perspective, many tech companies have historically underestimated regulatory and legal risk, treating privacy fines as a cost of doing business.

Apple's settlement was larger at $95M, possibly indicating a more serious violation. Both cases involved privacy concerns, but Google's was more automated, potentially explaining the lower settlement. 'Estimated data' for non-monetary aspects.

What the Settlement Actually Covers and Doesn't Cover

Understanding what a settlement actually includes is crucial. Many people assume settlements mean the company will change its behavior and compensate victims. But the reality is more nuanced.

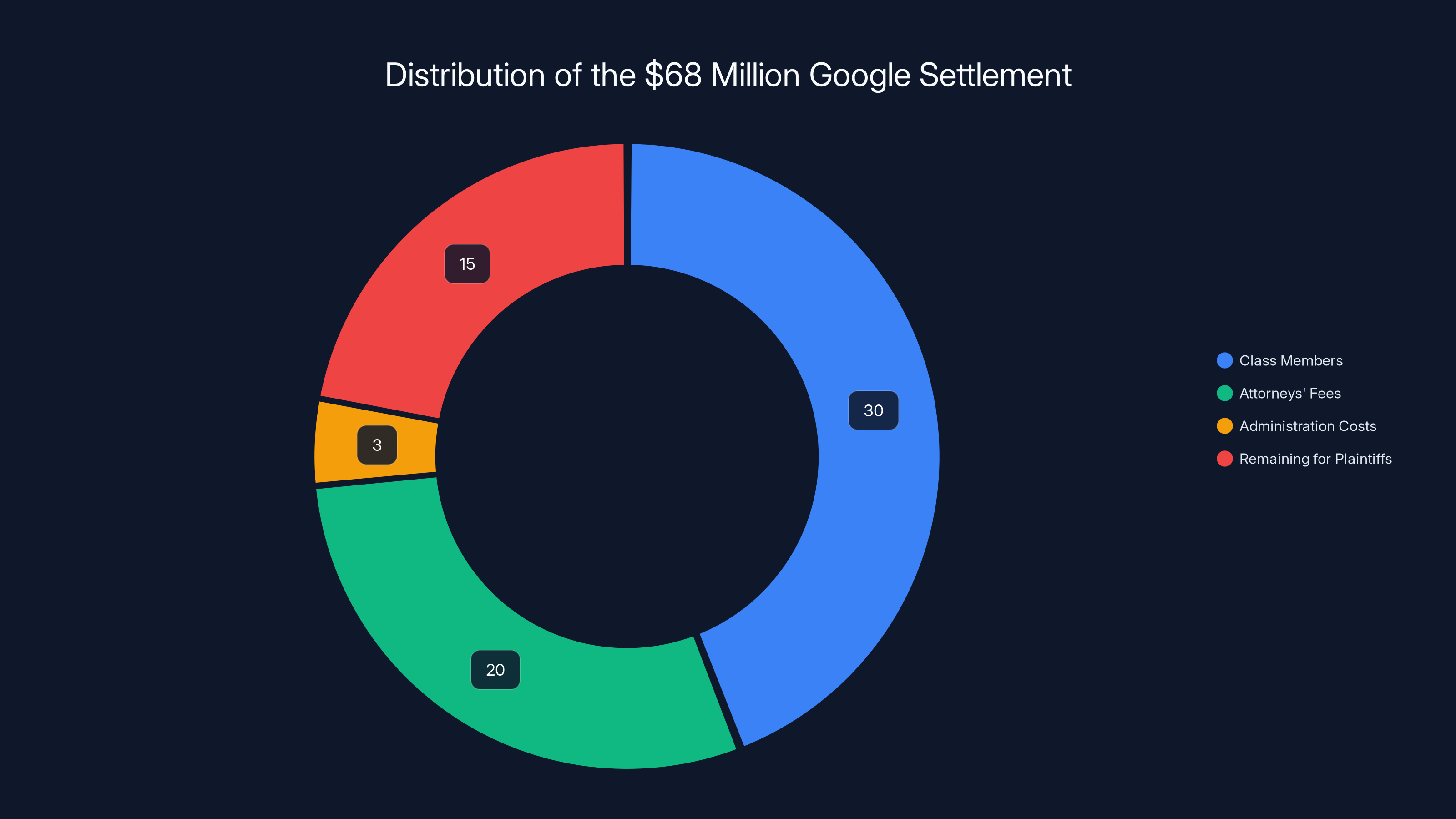

The $68 million Google settlement is likely structured as follows:

Actual Payouts: A portion goes to the class members—people who were part of the lawsuit. Given that there could be millions of potential class members, the individual payouts might be modest. If 5 million people are in the class, that works out to roughly

Attorneys' Fees: A substantial portion goes to the law firms that brought the case. Class-action attorneys typically take 25-33% of the settlement. So roughly $17-22 million would go to lawyers.

Administration Costs: Running the settlement, processing claims, and administering payouts costs money, typically 3-5% of the settlement.

What's Left for Plaintiffs: After attorney fees and administration, plaintiffs might see

Beyond the money, settlements sometimes include behavioral changes:

Potential Requirements (though the details of Google's settlement haven't been fully disclosed):

- Improved disclosure to users about how Assistant recordings are used

- Enhanced accuracy requirements for wake-word detection

- Restrictions on using false-accept recordings for advertising targeting

- Regular audits by an independent monitor

- Removal of existing problematic recordings from systems

What's critical is what the settlement probably doesn't do:

- It doesn't shut down Google Assistant or require significant architectural changes

- It doesn't prevent future false accepts because the technical problem isn't easily solvable

- It doesn't criminally prosecute anyone at Google (this is a civil settlement, not criminal)

- It doesn't admit Google did anything wrong (no admission of liability)

- It probably doesn't substantially change Google's architecture or business model

Non-admission of wrongdoing is standard in tech settlements because admission would expose companies to additional liability in other cases and regulatory proceedings. It's a legal strategy that allows companies to settle while preserving their position that they acted properly.

Regulatory Response and Future Implications

Google's settlement isn't happening in isolation. It's part of a broader wave of regulatory scrutiny targeting voice assistants and voice-enabled devices.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has been investigating voice assistant privacy practices more aggressively. The FTC's mandate is to protect consumers from unfair and deceptive practices. Using false-accept recordings for targeted advertising without disclosure arguably qualifies as both unfair and deceptive.

State attorneys general, particularly in California, have been more aggressive on privacy issues than federal regulators. California's Attorney General's office has been increasingly willing to sue tech companies for privacy violations, understanding that California's large population and economic significance make it a bellwether for national trends.

The settlement sends a message to regulators: there's legal precedent for holding companies liable for voice assistant privacy violations. Future lawsuits will likely reference Google's and Apple's settlements as evidence that courts take these issues seriously.

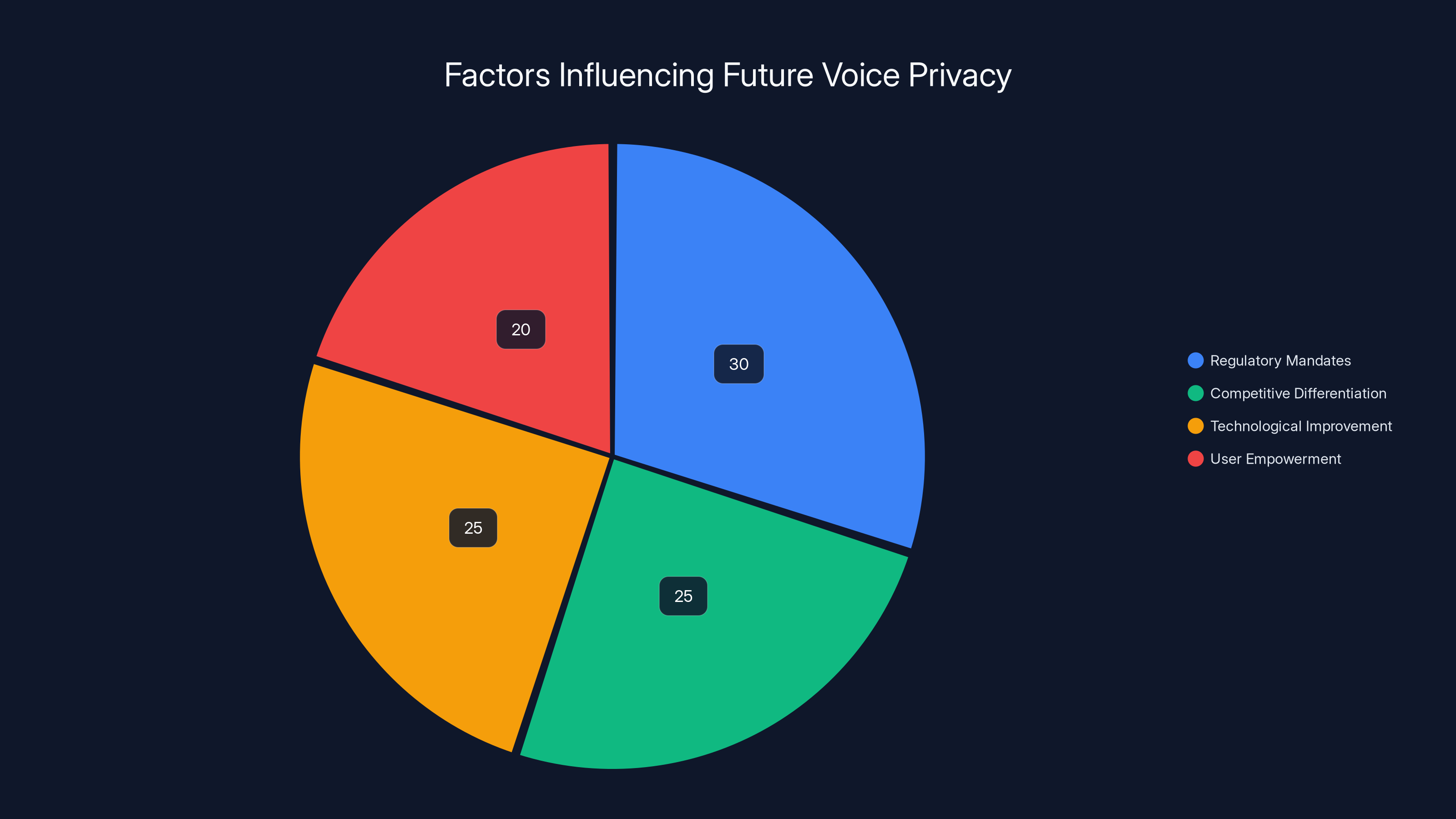

Looking forward, we'll probably see:

Enhanced Disclosure Requirements: Companies will need to be more transparent about how they use voice recordings, including false accepts. Some jurisdictions might require explicit opt-in consent rather than relying on device activation as implied consent.

Technical Accountability Standards: Regulators might establish industry standards for false-accept rates and require companies to meet minimum accuracy thresholds before monetizing recordings.

Privacy-Preserving Architecture: Companies might face pressure to process more voice processing locally on devices rather than sending audio to cloud servers. Edge computing for voice would reduce the volume of data leaving users' homes.

Right to Deletion: Users might gain stronger rights to delete their voice recordings, including recordings they didn't know existed.

International regulators, particularly in Europe under GDPR, are already imposing stricter requirements. The European Union's approach to privacy is more protective than U. S. law, so we might see European privacy standards gradually influence U. S. regulation as international pressure mounts.

Regulatory mandates are estimated to have the largest influence on improving voice privacy, followed by competitive differentiation and technological improvement. Estimated data.

The Technical Challenge: Can We Build Accurate Wake-Word Detection?

Here's the uncomfortable truth: false accepts in voice assistants are inevitable with current technology.

Wake-word detection is a speech recognition problem, but it's different from general speech recognition. Your device needs to recognize a specific phrase ("Hey Google") with high accuracy while also being responsive. It can't afford to miss a single legitimate wake word because users get frustrated if they have to repeat themselves.

The acoustic models that power wake-word detection are neural networks trained on thousands of examples of people saying the phrase in different accents, different room environments, different microphone types, and different speaking speeds. The system learns patterns that correlate with someone saying "Hey Google."

But real-world audio is chaotic. Your partner might say something that accidentally matches the acoustic pattern. The TV might play a snippet of dialogue. Someone might be practicing their Spanish and say a phrase that sounds similar. Each of these has some probability of triggering a false accept.

The mathematical relationship looks roughly like this:

Where

"Hey Google" is a relatively common phrase in English. "Alexa" is even worse because it's a real name that people use in conversation. "OK Google" is slightly better. "Hey Siri" is also relatively common.

Compare this to something like "Jarvis" or "GERTY" (used in sci-fi)—names that don't appear naturally in English speech. Those would have much lower false-accept rates. But they're awkward for users.

Improving wake-word accuracy is possible, but it requires trade-offs:

Option 1: Stricter Acoustic Matching → Lower false accept rates, but longer response times because the system is more cautious

Option 2: Better Noise Filtering → Fewer false accepts from background noise, but requires more powerful hardware in the device, increasing cost and battery drain

Option 3: Longer Wake Phrase → "Hey Google, listen to me" instead of just "Hey Google" → More distinctive, lower false accepts, but annoying for users who have to say more

Option 4: Multi-Modal Activation → Require the device to detect both sound and some other signal (like picking up the phone) → Eliminates false accepts, but breaks the hands-free convenience promise

Each option involves pain. This is why companies haven't solved the problem despite having the technical and financial resources to do so. The fundamental constraint is user experience. People want instant response, natural interaction, and low false-positive rates. You can have two of those three, but not all three with current technology.

Google and other companies have been gambling that users will tolerate occasional false accepts in exchange for the convenience and instant response times. The settlements suggest that gamble is increasingly untenable.

User Consent and the Paradox of Activation

One fascinating legal question embedded in this case is the meaning of consent.

When you buy a Google Home or enable Google Assistant on your phone, you agree to Google's terms of service. Buried in those terms is language about how Google will use voice data. The company would argue that activating the device and using the service constitutes consent to the entire process.

But the plaintiffs in this case argued that consent is only valid if it's informed. Users didn't actually know that:

- False accepts were happening

- Their false-accept recordings were being retained

- These recordings were being used to improve advertising targeting

- They had no easy way to identify and delete these recordings

This gets at a fundamental question about technology consent: if the terms of service technically disclose a practice, but most users never read the terms, doesn't understand the disclosure, and has no practical way to control the practice, is that truly informed consent?

Legal scholars call this the "manifest obscurity" problem. Companies can legally disclaim responsibility for practices they've disclosed, but if those disclosures are so buried and technical that ordinary people can't understand them, the law is increasingly questioning whether that disclosure is meaningful.

European law has taken a stronger stance on this. Under GDPR, consent must be:

- Freely given: Not buried in terms of service you're forced to accept

- Specific: Not vague or bundled with other practices

- Informed: Explained in clear language

- Unambiguous: Clear affirmative action required, not just lack of objection

U. S. law is moving slowly in this direction, particularly in California. The CCPA requires that companies explain what data they collect and how they use it in understandable language. The lawsuit against Google essentially argued that Google failed to do this regarding false-accept recordings.

This has implications for how companies design their privacy disclosures going forward. Simply citing a 50-page terms of service isn't sufficient. Companies need to actively inform users in clear, accessible language about data practices, particularly around voice recording.

False accept rates in wake-word detection systems vary from 0.5% to 2% depending on acoustic conditions. Estimated data shows higher error rates in noisier environments.

What Users Should Know About Their Voice Assistant Privacy

Given these issues, what can you actually do to protect your privacy when using voice assistants?

First, understand what's being recorded. Most voice assistant companies allow you to review and delete your recordings. Google has myactivity.google.com where you can see every recording, search, and command. Amazon has similar tools in the Alexa app. Apple has privacy settings in Siri preferences. Take time to actually review what's there. You might be shocked.

Second, disable what you don't need. If you rarely use voice shopping on Alexa, disable voice purchasing. If you don't care about voice search history, turn off the activity logging. Every feature that's disabled reduces the amount of data being collected.

Third, consider local processing. Some voice assistants now support on-device processing for certain functions. Google has on-device speech recognition for some features. Processing voice locally on your device instead of sending it to servers means Google never sees the audio. If your device supports this, enable it.

Fourth, manage your activity settings. You can turn off automatic activity logging in Google, Amazon, and Apple products. When you do, your commands and searches aren't saved to your account history. This doesn't prevent recording in the moment (the device still needs to hear your command), but it prevents permanent storage.

Fifth, use voice assistant judiciously. The more you use it, the more data you generate. Consider using voice primarily for convenience-driven tasks (setting timers, playing music) rather than asking about sensitive topics. Use text-based search for private questions.

Sixth, read privacy policies carefully. When companies update their voice assistant policies, actually read the changes. Privacy policies are dense, but they often include important information about what's changing and how your data will be used.

Seventh, participate in privacy advocacy. Support organizations pushing for stronger privacy rights. Vote for representatives who take privacy seriously. The settlements only happen because of class-action litigation, which is driven by people willing to participate in lawsuits.

The Bigger Picture: Privacy as a Competitive Disadvantage

One overlooked aspect of this settlement is what it reveals about competitive dynamics in tech.

Google, Apple, and Amazon all face the same technical challenge of false accepts. They all collect voice data and use it for advertising and service improvement. Yet Apple settled for

Why? Partly it's about litigation luck and which plaintiff attorneys chose to pursue which cases. But it also reflects differences in business model.

Google's core business is advertising. Every piece of data, including false-accept recordings, fits naturally into the advertising optimization engine. That creates maximum incentive to retain and use the data.

Apple's core business is selling devices at premium prices. Apple has positioned itself as privacy-protective, using "privacy" as a differentiator against competitors. When Siri recording issues became public, it contradicted Apple's privacy positioning, making the story more damaging.

Amazon's core business is e-commerce and cloud services. Alexa is important but not core. Amazon might have less aggressive data-retention policies, or less aggressive targeting, making the privacy violation less obvious.

This suggests an interesting dynamic: privacy might become a competitive advantage. Companies that can credibly claim better privacy practices might attract privacy-conscious consumers. Apple has been trying to position itself this way, though the Siri settlement damaged that narrative.

For Google, privacy represents a conflict of interest. The advertising business model fundamentally depends on collecting as much data as possible. A truly privacy-protective Google would be less profitable. This creates structural resistance to meaningful privacy improvements.

Future litigation and regulation might force change, but it will likely be through external pressure rather than voluntary corporate goodwill.

Emerging Technologies and Future Voice Privacy

Tech companies are working on several approaches that could improve voice privacy while maintaining functionality.

Federated Learning: Instead of sending all voice data to central servers, train machine learning models on-device and only send model updates to the cloud. Google is investing in this for several applications. It reduces the volume of raw data being transmitted.

Differential Privacy: Add mathematical noise to data sets so that insights can be extracted without identifying individuals. You could analyze aggregate patterns of voice-assistant usage without knowing which specific user said what. This is technically sophisticated but possible.

Homomorphic Encryption: Process encrypted data without decrypting it first. This is computationally expensive but theoretically allows cloud processing of voice data without the cloud service ever seeing the actual audio.

Hardware-Based Privacy: Trust-execution environments (TEEs) and secure enclaves on phones and devices can process sensitive data in a protected zone that even the operating system can't access. This prevents unauthorized access.

Voice Authentication Instead of Recording: Rather than recording voice for later analysis, use voice for authentication only—verify it's actually you speaking—and discard the recording immediately. The data collection stays minimal.

These aren't hypothetical. Companies are deploying variations of these approaches. But they typically involve trade-offs in functionality, performance, or user experience. It's not that companies can't build privacy-preserving voice assistants. It's that doing so requires accepting lower performance or less convenient user interfaces.

Whether companies prioritize these improvements likely depends on regulatory pressure and competitive dynamics. If regulators require privacy-preserving architectures, companies will build them. If privacy becomes a competitive differentiator, companies will build them. Absent those pressures, the incentives point toward maximum data collection.

Industry Standards and Future Compliance Requirements

Following the Google settlement, we'll likely see the emergence of industry standards for voice assistant privacy.

Trade associations like the Consumer Technology Association and industry standards bodies might establish best practices for:

- Acceptable false-accept rates (e.g., maximum of 1 per 1,000 hours of operation)

- Data retention policies (e.g., delete unauthorized recordings within 30 days)

- Transparent disclosure requirements (e.g., must explain in plain language how voice data is used)

- User rights (e.g., one-click access to all recordings, easy deletion options)

- Third-party sharing restrictions (e.g., prohibit sharing voice data with advertisers without explicit consent)

Regulators like the FTC might codify some of these as official requirements. The California Attorney General might issue guidance on compliance. International regulators, particularly in the EU, might impose stricter requirements that then influence U. S. companies globally.

What's particularly interesting is that these standards could create competitive advantages. A company that promises false-accept rates below the industry average, immediate deletion of unauthorized recordings, and transparent data practices could market privacy as a key differentiator.

Smaller companies and startups might actually have an advantage here. They could build privacy-first voice assistants without the legacy systems and advertising business models that constrain larger players. We might see a wave of privacy-focused voice assistant startups that cater to privacy-conscious consumers.

The Human Cost: Stories from the Affected

Behind every lawsuit are real people who experienced real harm.

Court filings in privacy cases often include detailed accounts from plaintiffs describing what happened to them. While the Google settlement details aren't fully public, based on similar cases, we can infer the types of experiences that motivated the lawsuit.

One plaintiff might have discovered that Google had thousands of recordings they never authorized. They might have been having sensitive conversations about health issues, relationship problems, or financial struggles. The fact that strangers at Google could potentially listen to these recordings (even if they didn't) was deeply invasive.

Another plaintiff might have noticed unusual targeted ads appearing shortly after mentioning something in conversation. They said "my knee hurts" near their phone, and suddenly ads for knee braces appeared. This person didn't have a documented knee problem online, so the only way Google could have known was through the voice assistant listening.

A third plaintiff might have been upset simply about the principle: they never consented to have their device recording when they weren't addressing it. They thought they had control over activation but discovered that control was illusory.

From a psychological perspective, voice privacy violations feel different from other privacy violations. Written data feels abstract. But knowing that your intimate voice conversations might be recorded feels viscerally invasive. You can't control what you sound like or how your tone might be misinterpreted. Voice recordings capture you at your most vulnerable.

For families with young children, the concern is different. Parents don't want their children's voices recorded without consent. Children are particularly vulnerable, and their voices recorded in family settings could be misused in ways parents can't predict.

These human experiences are what ultimately drive litigation and settlement. Without actual people being harmed and outraged, there would be no lawsuit and no settlement. The $68 million isn't really punishment—it's too small to really hurt Google. But it's acknowledgment that real people were wronged, and some compensation is owed.

Lessons for Other Tech Companies

Google's settlement doesn't just affect Google. Every company building voice-enabled products is watching and learning.

The immediate lesson is obvious: voice privacy matters legally. If you're going to deploy voice assistants, implement systems that minimize unauthorized recording, disclose clearly what you're doing, and respect user deletion requests. This is table stakes.

But there are deeper lessons:

First, design for privacy from the start. Don't treat privacy as an afterthought or regulatory compliance box. Embed privacy into the product architecture. If you're building a voice assistant, the default should be minimal data collection, not maximum.

Second, be transparent about limitations. Tell users upfront that false accepts will happen. Explain what the system does with recordings. Make it easy for users to understand exactly what's happening. This prevents the "shocked discovery" that motivates lawsuits.

Third, separate data collection from monetization. You can still collect voice data to improve your product. But separate that from the commercial use of that data for advertising targeting. Users might tolerate one but not both.

Fourth, implement strong data governance. Establish clear policies about how long data is retained, who has access to it, and what it's used for. Make sure employees actually follow these policies. It's the difference between "a mistake happened" and "systematic abuse."

Fifth, assume litigation is likely. Privacy litigation is increasingly common. Budget for it. Assume that any data you collect might eventually be scrutinized in court. Design systems you'd be comfortable defending in front of a jury.

Sixth, differentiate on privacy if you can. If your business model allows, position privacy as a core value. Be the company that respects user privacy more than competitors. This is harder for advertising-based businesses but entirely possible for others.

For Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and other companies building voice assistants, Google's settlement is both a warning and a roadmap for what to expect if they get sued.

The Regulatory Future: What's Coming Next

Based on the trajectory of privacy regulation, we can make some educated predictions about what's coming in the next few years.

Expect stricter FTC enforcement. The FTC has been increasingly aggressive on privacy and deception. Following the Google settlement, the FTC might establish formal enforcement actions against other voice assistant companies, even without class-action litigation.

Expect state-level regulation. California's success with CCPA will embolden other states to pass their own privacy laws. We're likely to see a patchwork of state regulations, with California and possibly New York setting the most aggressive standards.

Expect European influence. GDPR already imposes strict requirements on companies processing voice data. If the EU passes even stricter voice-privacy regulations, multinational companies will likely adopt the European standard globally to avoid maintaining separate systems.

Expect industry self-regulation to emerge. Trade associations will probably develop standards to try to preempt government regulation. The idea is: establish reasonable standards ourselves before regulators impose stricter ones.

Expect technical requirements. Regulators will increasingly require companies to implement privacy-enhancing technologies. Federated learning, differential privacy, and on-device processing might become mandatory rather than optional.

Expect a shift in the business model for voice. The economics of free voice assistants funded by advertising might not survive strict privacy regulation. We might see paid voice assistants, privacy-focused alternatives, and a move away from monetizing voice data.

Conclusion: The Reckoning for Voice Privacy

Google's $68 million settlement is a financial slap on the wrist for a company worth trillions. But it represents something more significant: regulatory acknowledgment that voice privacy is a legitimate concern and companies will be held accountable.

The case reveals uncomfortable truths about modern voice assistants. The underlying technical challenge of false accepts is real and not easily solved. The economic incentives to collect and monetize all available data are strong. And users often don't understand what they're consenting to when they enable voice assistants.

But the settlement also shows that litigation, regulatory pressure, and reputational risk can compel change. Google might not have voluntarily improved its privacy practices, but the prospect of lawsuits and fines creates incentives.

Moving forward, we'll likely see a gradual shift toward better voice privacy through some combination of:

- Regulatory mandates requiring companies to minimize false accepts and restrict data usage

- Competitive differentiation as companies compete on privacy as a selling point

- Technological improvement as privacy-preserving techniques become more practical

- User empowerment as people become more aware of their rights and exercise them

None of this requires companies to be benevolent. It just requires that the economic and legal costs of privacy violations exceed the benefits of maximum data collection.

For users right now, the lesson is clear: voice assistants are incredibly convenient, but that convenience comes at a privacy cost. Understanding that trade-off and actively managing your voice assistant settings is the responsible approach.

The future of voice privacy isn't determined yet. It depends on whether regulators enforce standards, whether companies innovate on privacy, and whether users demand better. But the trajectory is clear: voice privacy is becoming a serious legal and regulatory concern, and companies that ignore it will face consequences.

FAQ

What is a false accept in voice assistant technology?

A false accept occurs when a voice assistant activates and begins recording without the user saying the wake word. This can happen when background noise, another person's speech, or television audio resembles the acoustic pattern of the wake word closely enough to trigger the always-listening detection system. False accepts are an inevitable byproduct of designing systems that respond instantly without requiring manual activation, though the frequency can be reduced through more restrictive acoustic models.

How did Google use false accept recordings for advertising?

When false accepts occurred, Google's systems apparently retained these unauthorized recordings and fed them into machine learning models that power targeted advertising. If a false accept captured a private conversation about a medical condition, fitness interest, or purchase intent, the advertising algorithms would learn from that information and adjust the user's ad targeting profile accordingly. This meant users received more relevant ads without ever knowingly consenting to have their private conversations analyzed for advertising purposes.

What is the difference between Google's settlement and Apple's Siri settlement?

Apple settled for

Can I delete my Google Assistant recordings?

Yes, you can review and delete your Google Assistant recordings by visiting myactivity.google.com and filtering for Google Assistant activity. You can delete individual recordings or bulk delete all recordings from a specific time period. It's recommended to review your activity history regularly to understand what's being recorded and to delete false accept recordings that you didn't authorize. You can also disable activity logging entirely by visiting myactivity.google.com/activitycontrols and unchecking "Web & App Activity."

Why haven't tech companies fixed the false accept problem?

False accepts are inherently difficult to eliminate with current technology due to a fundamental trade-off between responsiveness and accuracy. Making wake-word detection more strict (to reduce false accepts) requires users to speak more clearly and loudly, degrading the user experience. Making it more permissive (to maintain responsiveness) increases false accepts. Additionally, there are economic incentives for companies to retain false-accept data because it provides valuable information for advertising targeting. Better technology alone isn't sufficient without regulatory pressure or competitive disadvantage to change the economic calculus.

What does it mean that Google didn't admit wrongdoing in the settlement?

Non-admission settlements are standard in tech litigation. When a company settles without admitting wrongdoing, it means they're paying to avoid further litigation and reputational damage without formally conceding that their conduct violated laws or regulations. This protects the company from exposure to additional liability in other cases and from regulatory findings of violation. However, the settlement payment itself implies acknowledgment that some aspect of the conduct was questionable, even if not technically illegal.

What is the legal basis for the voice recording lawsuit against Google?

The lawsuit was based on California privacy laws, particularly claims of unlawful interception of confidential communications without consent, which can fall under both state privacy statutes and federal wiretapping laws. The plaintiffs argued that Google intentionally deployed a system that recorded private communications (through false accepts), failed to disclose this practice to users, and used the recorded information for commercial purposes (targeted advertising) without explicit consent. These actions allegedly violated California's consumer privacy laws and principles of informed consent.

How much money will individual users receive from the settlement?

The amount individual users receive depends on the size of the plaintiff class and the structure of claims. With a

What changes will Google make because of the settlement?

The specific requirements of Google's settlement haven't been fully disclosed, but typical voice assistant privacy settlements include improved wake-word detection accuracy, enhanced user disclosures about data usage, restrictions on using false-accept recordings for advertising targeting, easier access to and deletion of recordings, and potentially third-party audits to verify compliance. However, the settlement likely doesn't require fundamental architectural changes to Google Assistant, and false accepts will likely continue to occur at similar rates because the technical problem isn't easily solved without degrading user experience.

What regulatory changes might follow Google's settlement?

Likely regulatory responses include FTC enforcement actions against other voice assistant companies, state-level privacy legislation following California's lead, potentially federal voice-privacy standards, mandatory implementation of privacy-preserving technologies like federated learning or differential privacy, and stricter data-retention and third-party-sharing restrictions. International regulators, particularly in the European Union, may impose stricter requirements that influence global standards. Trade associations will likely develop industry standards to try to preempt government regulation.

Key Takeaways

Google's $68 million settlement over unauthorized voice assistant recording is a watershed moment in tech privacy litigation that will reshape how companies handle voice data and wake-word detection. Here's what matters:

The settlement isn't really about punishing Google for record-breaking misconduct—it's acknowledgment that even large, sophisticated companies will face legal consequences for privacy violations that users never explicitly consented to. The root cause, false accepts in voice detection systems, is a technical problem that won't be easily solved without degrading user experience, meaning similar issues will persist across the industry.

What changes this dynamic is regulatory enforcement and competitive pressure. Companies that can credibly commit to better privacy practices, especially privacy-first competitors unburdened by advertising business models, will increasingly differentiate on this dimension. The settlement provides a roadmap for what will happen to other companies if they face similar litigation.

For regular users, the practical implication is clear: understand that voice assistants are always listening (that's how they work), actively manage your activity history, disable features you don't use, and participate in privacy advocacy. The settlements only happen because of litigation, which depends on people willing to fight back.

Looking forward, expect more regulation, technical innovation in privacy-preserving voice processing, and gradually shifting business models for voice assistants. The era of consequence-free mass voice data collection is ending.

![Google's $68M Voice Assistant Settlement: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-s-68m-voice-assistant-settlement-what-happened-why-it/image-1-1769476076847.jpg)