Introduction: When Big Tech Abandons Hardware, Communities Step In

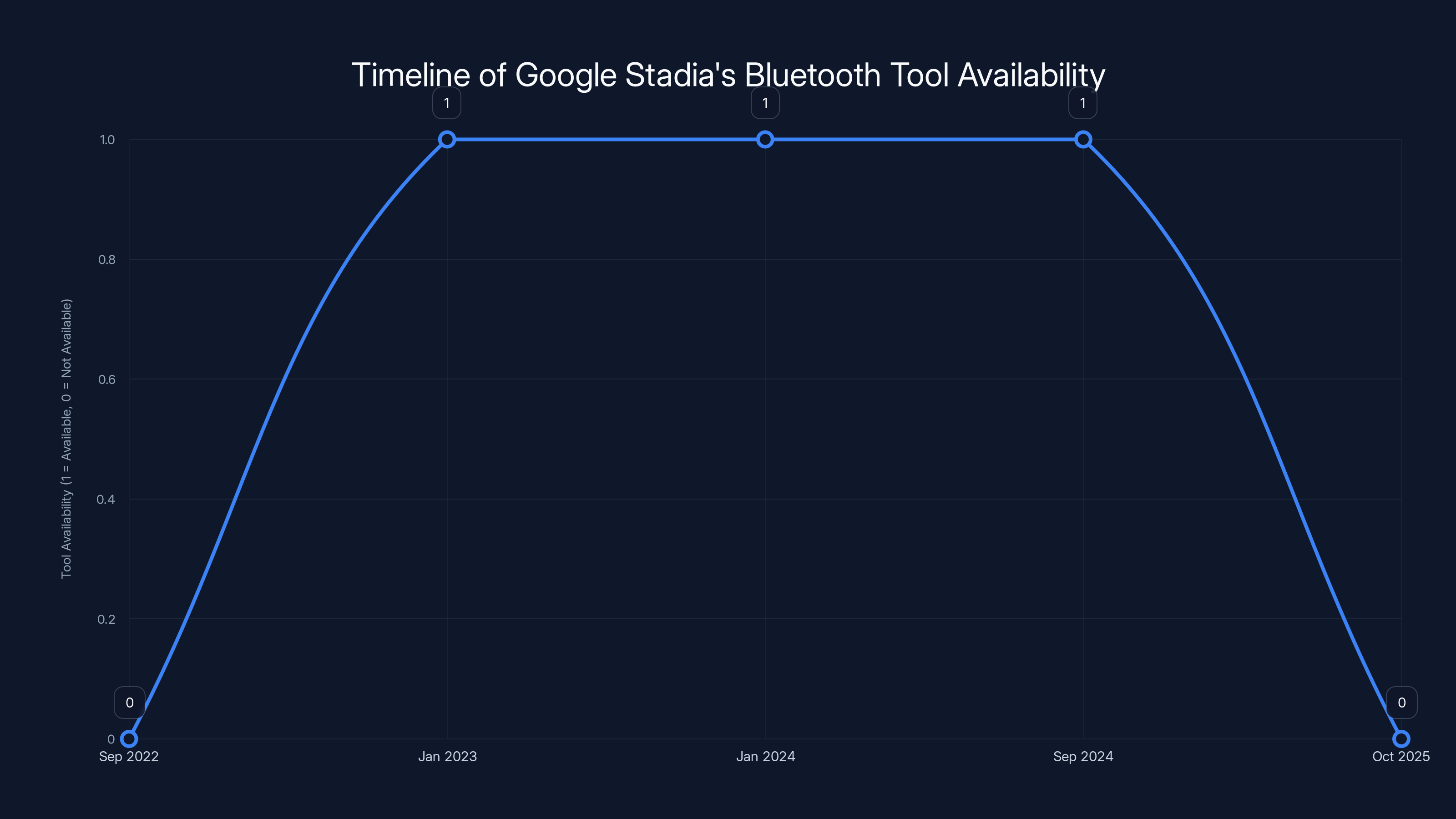

Google's cloud gaming platform Stadia is officially dead. But here's the thing that keeps surprising me about this story: the way it actually died wasn't completely terrible. Back in January 2023, Google quietly shut down Stadia's servers, refunded customers, and walked away from the project. Most failed tech products just vanish. Services get nuked. Hardware becomes e-waste. But Stadia had one redeeming feature that actually matters: before Google pulled the plug completely, they gave users a way to convert their proprietary controllers into standard Bluetooth gamepads.

That tool? It's now gone too.

This week, Google removed the Stadia Controller Bluetooth conversion page from their servers. It's the final nail in the coffin for a service that burned through $2.75 billion in development and marketing spend before being abandoned after just three years. Most people wouldn't notice. Most Stadia controller owners probably don't care anymore. But here's what's remarkable: before Google removed the tool, developers backed it up. They archived it. And they're now hosting working copies so other people can still use their old hardware instead of throwing it in the trash.

This is actually a blueprint for how technology should die.

When a product fails, there's typically a blame spiral. Executives point to market conditions. Journalists write obituaries about why it failed. Customers feel burned. Hardware owners are left holding dead tech. But the Stadia story is different. It's a case study in how a massive failure can contain within it seeds of something more enlightened: a recognition that even when corporations kill their products, the people who actually own and use them can reclaim those products through community effort and open archiving.

The story of Stadia's Bluetooth controller rescue tells us something important about the future of consumer technology. It's not just about Stadia—which is already dead and buried. It's about what happens when proprietary ecosystems fail, and why communities that care about their hardware might be the only things preventing a complete technological wasteland.

TL; DR

- Google removed the Stadia Controller Bluetooth conversion tool after completely shutting down Stadia in 2023, but developers had already archived it

- The community saved the tool on Git Hub and created working mirrors so people can still convert their controllers to standard Bluetooth gamepads

- Christopher Klay, who built the Stadia Enhanced browser extension, was among those who preserved the tool before Google deleted it

- The Stadia controller actually works well with Steam and PC games once converted, making the hardware worth saving rather than discarding

- This demonstrates how community preservation can rescue failed tech products and prevent e-waste when corporations abandon hardware

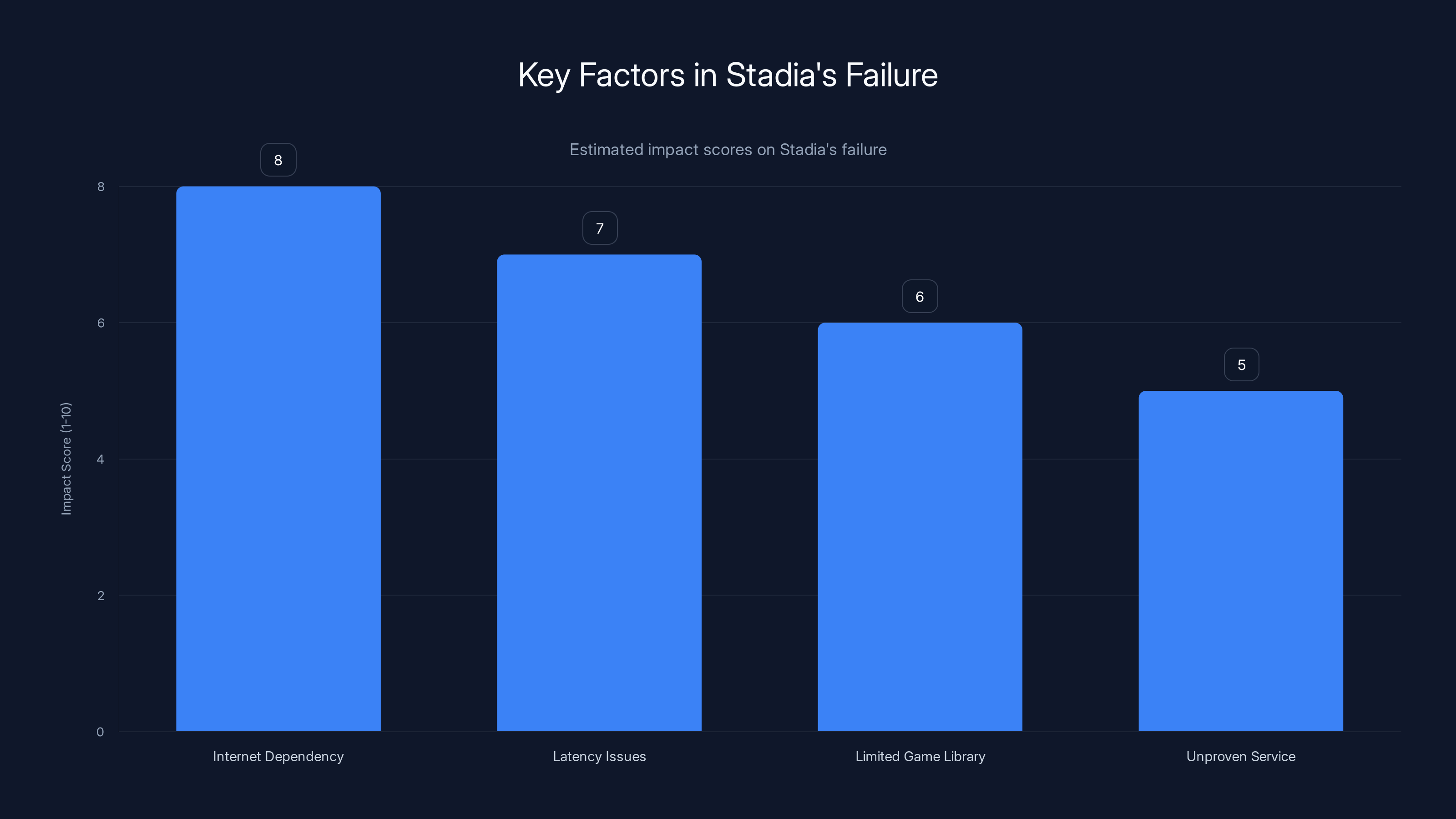

Internet dependency and latency issues were the most significant factors contributing to Stadia's failure. Estimated data.

What Happened to Google Stadia's Bluetooth Tool

Let's be clear about the timeline here, because it matters for understanding why this matters at all.

Google shut down Stadia's servers completely on January 18, 2023. That wasn't sudden. They announced the shutdown in September 2022, giving users four months' notice. It was honestly more consideration than most tech companies offer when killing products. Google refunded controllers, refunded games, refunded subscriptions. The money went back to customers' original payment methods.

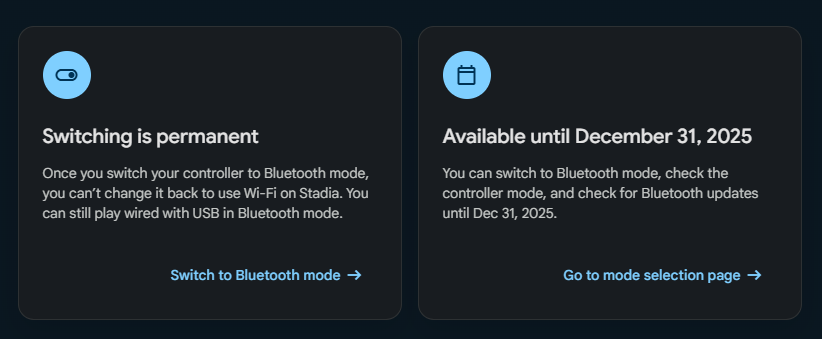

But hardware is different from digital services. You can't refund a physical controller back to the cloud. So Google did something smart: they released a tool that let you convert the Stadia controller into a regular Bluetooth gamepad. No more proprietary wireless dongle. No more relying on Stadia's servers. Just a standard Bluetooth controller that works with any platform.

The conversion process itself was elegantly simple. You'd go to Google's website, put your Stadia controller into pairing mode, click a button, and the tool would reprogram the firmware on the controller to just work as Bluetooth. The hardware was already capable of doing this—Google had just locked it down with software. Unlocking it was a few clicks.

That tool lived on Google's servers for two years after Stadia died. Most people had already forgotten about it. But this week, Google finally removed it. The page is gone. If you try to visit the conversion tool now, you get a 404 error.

For anyone who still owns a Stadia controller and hadn't converted it yet, this was bad timing. Except it wasn't, because the community had already saved it.

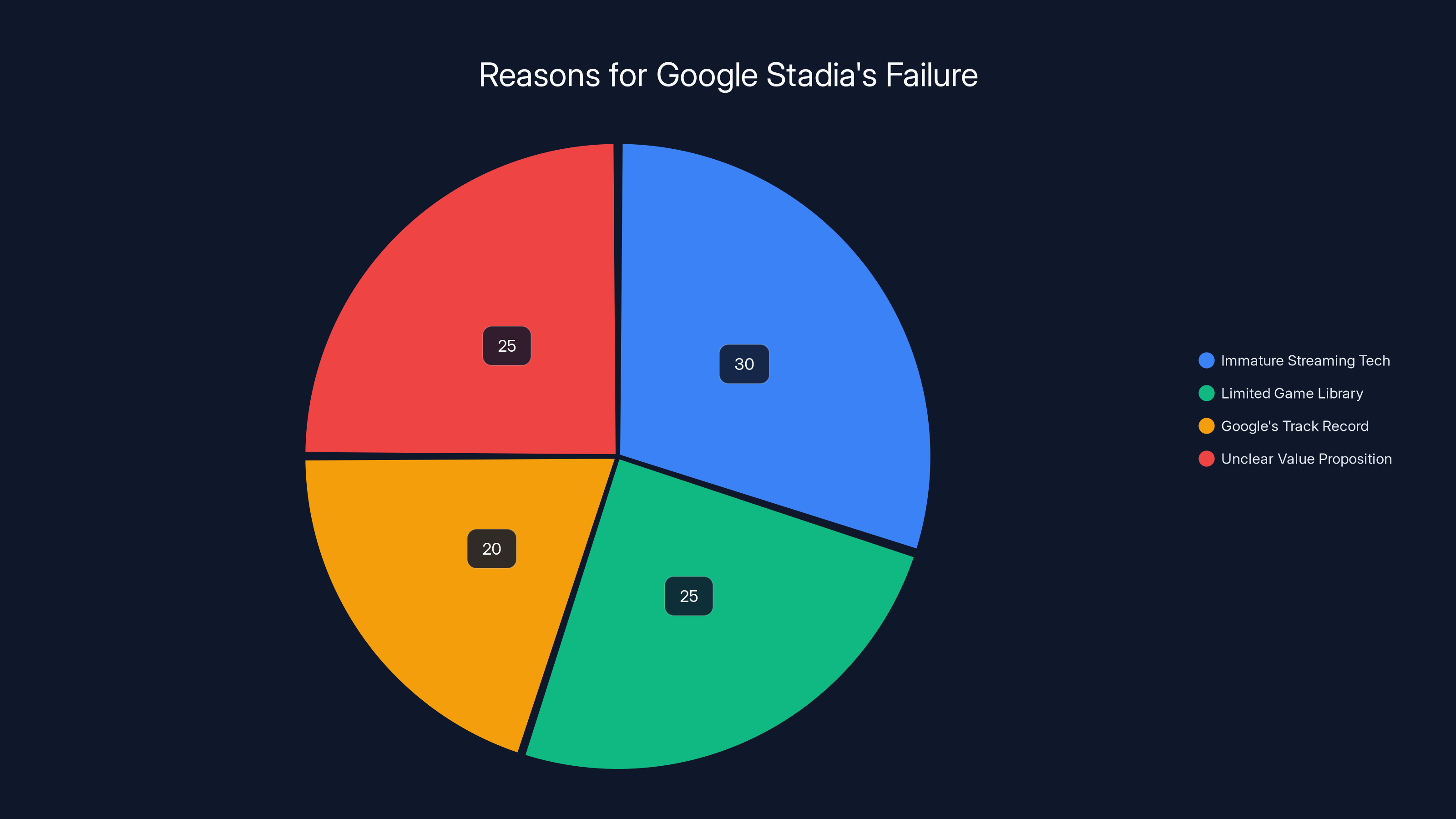

The primary reasons for Google Stadia's failure included immature streaming technology, a limited game library, Google's history of abandoning projects, and an unclear value proposition. Estimated data.

How Developers Preserved What Google Deleted

Before Google removed the tool, community members and developers extracted a copy and uploaded it to Git Hub. This is becoming increasingly important in tech culture: the idea that when corporations kill tools, people with technical skills can preserve them and make them available to everyone else.

Christopher Klay is probably the most visible person in this preservation effort. If that name sounds familiar, it's because Klay built the Stadia Enhanced browser extension—a fan project that added features Google never implemented natively. When Stadia shut down, Klay didn't just move on. They preserved the Bluetooth conversion tool and hosted it publicly.

The preserved version isn't a complicated hack or workaround. It's essentially a mirror of Google's original tool, running on independent infrastructure instead of Google's servers. When you use it, you're interacting with the same code, the same process, the same workflow—just hosted somewhere that won't disappear the moment Google decides it's no longer relevant.

This is significant for a few reasons. First, it prevents e-waste. A Stadia controller is still perfectly good hardware once you reprogram it. The Wi-Fi module is Bluetooth-capable. The buttons, the analog sticks, the haptic feedback—all of it still works. Converting it to Bluetooth means it can have a second life with Steam, with PC gaming, with emulation, with whatever else someone wants to use a gamepad for. Throwing it away because Google deleted the conversion tool would've been pointless waste.

Second, it's a precedent. It shows that when companies kill products, communities can step in. Not everyone can do this—it requires technical knowledge to host infrastructure, to maintain code, to ensure compatibility. But for people who have those skills, there's now an established pattern of preservation. When Google kills the next thing, there will be communities ready to save it.

Third, it keeps the Stadia story from being purely negative. Google made massive mistakes with Stadia. They didn't market it properly. They didn't convince developers to make exclusive games for it. They didn't address the fundamental latency and streaming quality issues that made it feel worse than local gaming. They launched too aggressively in too few markets. They burned billions of dollars on a product that never caught on.

But at the moment of death, Google at least handed the hardware back to its users in a usable form. And when Google inevitably abandoned that too, the community stepped in and made sure the tool stayed available.

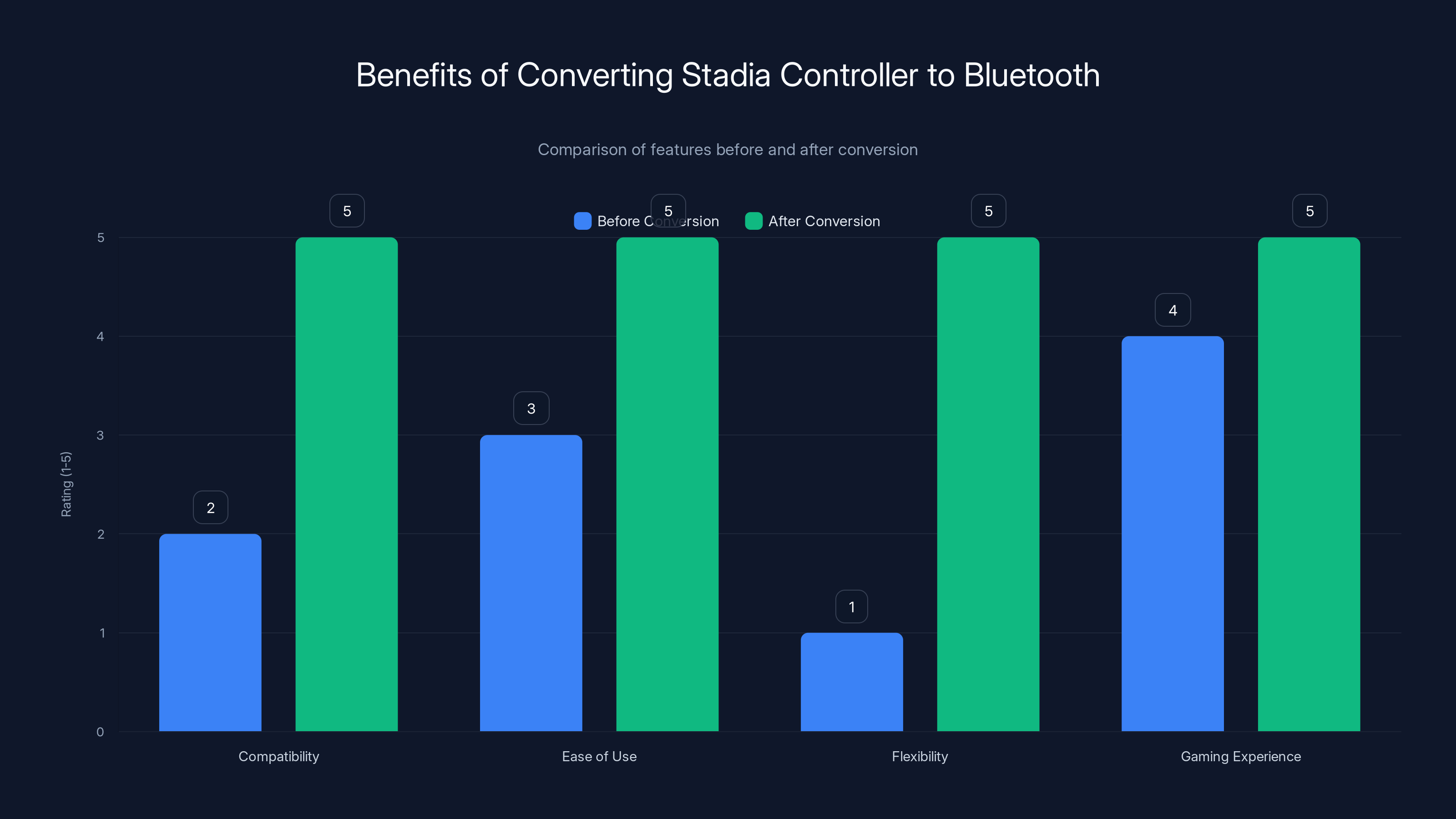

Why Converting Your Stadia Controller Actually Makes Sense

If you're wondering whether it's worth going through the conversion process, the answer is probably yes.

The Stadia controller, as a piece of hardware, is actually quite good. It has a solid build quality. The buttons feel responsive. The D-pad is actually usable—and that's rare in modern gamepads. The analog sticks have good tension and responsiveness. The haptic feedback is more nuanced than most controllers offer. When I tested gaming on Stadia before it shut down, the controller was never the problem. The streaming quality, the latency, the game library—those were problems. But the controller itself? That thing was fine.

Once you convert it to Bluetooth, you unlock a controller that works with basically everything. Steam detects it immediately. PC games recognize it. You can use it on phones, tablets, maybe even Mac depending on the game. It becomes a flexible gaming tool instead of a proprietary brick that only worked with Stadia.

The conversion process itself takes maybe 10 minutes total. You need:

- A Stadia controller in working condition with a battery

- Access to the conversion tool (through the preserved mirrors or through any archived copy)

- A USB-C cable or power source

- A computer with a web browser

You put the controller in pairing mode by holding the pairing button. You visit the tool's webpage. You click the button to start the conversion. The controller connects to the tool, the tool reprograms the firmware, and suddenly you've got a Bluetooth gamepad. No hacking required. No soldering. No complicated technical knowledge. The whole thing was designed to be straightforward.

After conversion, the controller works with Steam in particular surprisingly well. I've tested this personally, and Steam's controller support is sophisticated enough that the Stadia controller maps properly to most games. It's got all the buttons and features modern games expect. It works better than some cheaper third-party controllers you can buy new.

So here's the math: You've got a controller you're no longer using because the service it was designed for is dead. You can either throw it away, or spend 10 minutes converting it to something useful that works with the gaming platforms you actually use now. The fact that the conversion tool is still available, preserved by the community, makes the choice easy.

Google invested $2.75 billion in Stadia, with the majority allocated to development and marketing. Estimated data based on typical tech project allocations.

The Stadia Failure: Context for Why This Matters

To understand why the Stadia controller conversion tool deserves attention, you need to understand what a massive failure Stadia was and how it happened so quickly.

Google announced Stadia in March 2019 with enormous fanfare. The concept was compelling from a technology perspective: stream games from Google's data centers the same way you stream videos from Netflix. No need to buy expensive hardware. No need to wait for downloads. Just open a browser and play. Developers would love this because they wouldn't have to optimize for dozens of different PC configurations or console generations. Gamers would love this because they wouldn't need a

The problem was that literally nobody wanted this.

Well, that's not quite fair. Some people wanted it. Early adopters tried it. Technical people were curious. But the mainstream gaming audience? They looked at Stadia and saw a service that required a strong, stable internet connection. They saw latency that made fast-paced games feel unresponsive. They saw a limited game library. They saw a completely unproven service from a company known for killing products.

Google launched Stadia in November 2019. By September 2022—less than three years later—they announced they were shutting it down completely. That's not a long runway. That's not a niche product finding its audience over time. That's a fundamental rejection of the concept.

The financial cost was staggering. Google spent approximately $2.75 billion developing Stadia and bringing it to market. Some estimates put it higher. This wasn't just the cost of the servers and infrastructure. This was millions in exclusive game development deals, marketing budgets that blanketed gaming conventions and websites, hardware subsidies to get controllers into customers' hands, salaries for hundreds of engineers and executives working on the project.

All of that money was essentially written off. Google had to admit that the bet didn't work.

Why did it fail so catastrophically? The explanations usually come down to a few factors:

The streaming technology wasn't ready. Stadia required 35 Mbps for 4K, 25 Mbps for 1080p/60fps. For comparison, Netflix only needs 25 Mbps for 4K. But that's a one-way stream of pre-rendered content. Games are interactive, and they require imperceptible latency. If there's even a noticeable delay between when you press a button and when you see the result on screen, the whole thing feels broken. Stadia had this problem. It was subtle enough that you got used to it after a few minutes, but it was always there.

The game library was weak. This is a chicken-and-egg problem. Publishers didn't want to invest in exclusive Stadia games because they didn't know if the platform would succeed. They didn't know if enough people would use it. So the library stayed small. And potential customers looked at the library and decided it wasn't worth switching to a new platform for such limited options.

Google didn't commit long-term. This is maybe the most damaging factor. Gamers knew that Google kills products. Google had a track record of abandoning services that didn't hit massive scale quickly. Stadia was never going to be a platform people bet their gaming future on when the company running it had such a track record of abandonment.

The value proposition was unclear. Who was Stadia for, exactly? People with high-end internet who didn't want to spend money on hardware? But those people usually already had gaming PCs or consoles. Casual gamers who wanted to play games in a browser? But casual gamers play mobile games, not graphically intensive titles. Google never found an answer to that question.

So Stadia died. And when it died, the company at least tried to do right by the people who'd bought controllers and invested time in the platform. They gave refunds. They provided a conversion tool. They didn't just pull the plug and leave people with useless hardware.

Except the conversion tool is now gone too. Which is where the community preservation story comes in.

Christopher Klay and the Stadia Enhanced Legacy

To really understand why Christopher Klay's preservation effort matters, you need to know about Stadia Enhanced.

Stadia Enhanced was a Chrome extension that added features to Stadia that Google should've added natively. It added options to adjust video quality settings on the fly. It added ability to customize controller layouts. It added better game management. It added features that made using Stadia less of a chore.

This is not uncommon in gaming. Enthusiasts create mods and extensions for services because those services aren't quite what people want them to be. It's a way for technical users to scratch their own itch. It's also, implicitly, a way of saying: "I like this platform enough to invest time in improving it."

When Stadia shut down, Klay could've just let Stadia Enhanced disappear into obsolescence. But instead, they pivoted. They preserved the Bluetooth conversion tool. They made it available to the community. They became one of the people ensuring that when Google removed that tool, it wouldn't actually disappear.

This is significant because it shows how open-source thinking and community values are starting to shape what happens when corporate products die. It's not inevitable that Klay would do this. Klay could've moved on to other projects. But instead, Klay chose to be the person who said: "This tool is too useful to lose."

The preserved version of the tool on Git Hub is essentially a snapshot of Google's original code, rehosted on community infrastructure. It's not a hack or a circumvention. It's just the same thing, in a different location, maintained by people who care about it.

This pattern is becoming more common in tech. When Mozilla faced criticism about privacy, the community created Librewolf as a privacy-focused Firefox fork. When Elon Musk changed Twitter, people created Mastodon as a decentralized alternative. When major platforms make unpopular changes, communities often fork and preserve the old version.

Stadia is just one more data point in this pattern. As corporations increasingly abandon products, communities are becoming the institutions that preserve and maintain the things that people actually care about.

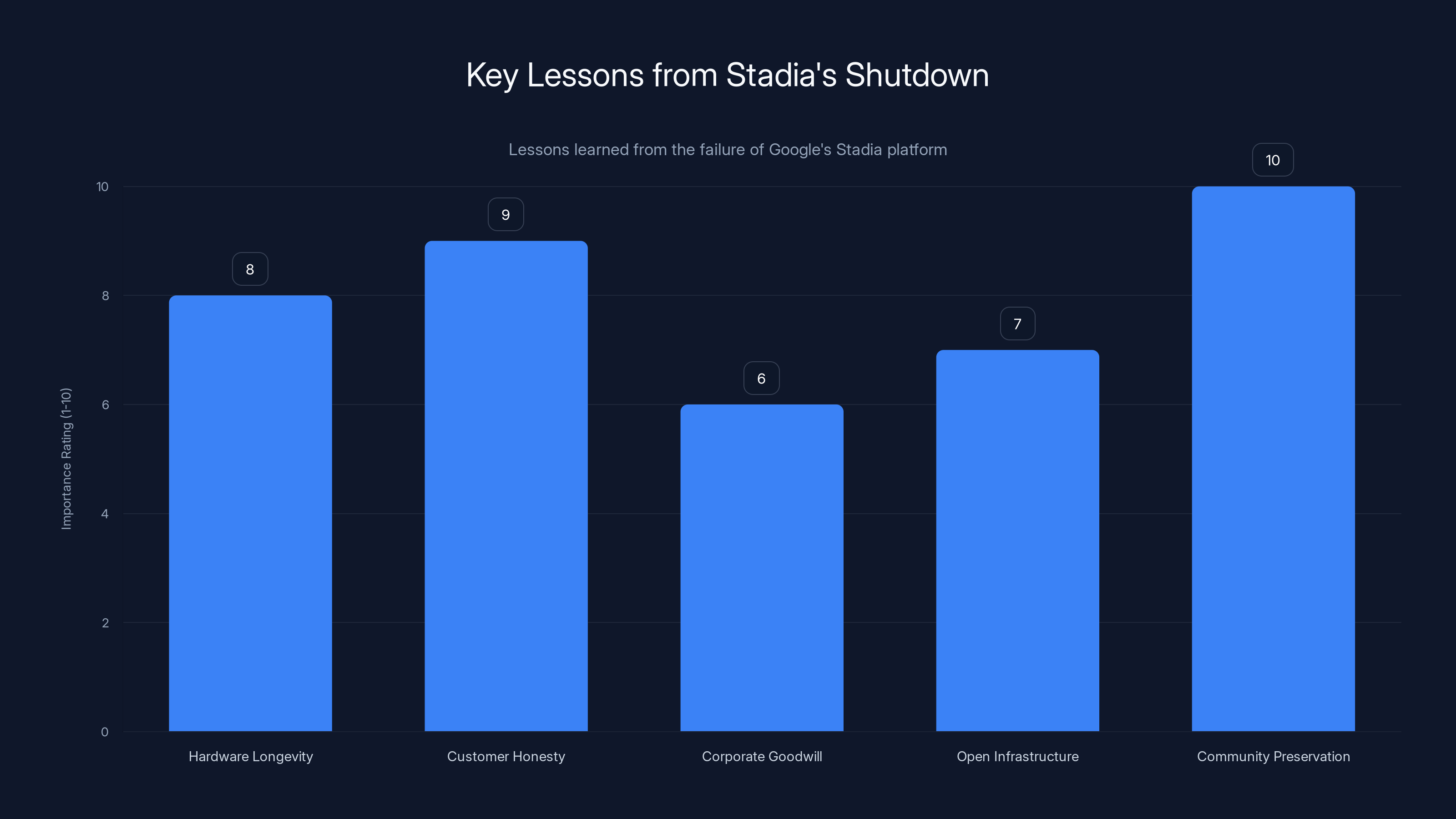

Community preservation and customer honesty are the most important lessons from Stadia's shutdown, highlighting the need for open infrastructure and hardware longevity. (Estimated data)

Where to Find the Preserved Tool

If you have a Stadia controller sitting in a drawer somewhere and you want to convert it to Bluetooth, you have options.

The most straightforward path is to find one of the preserved mirrors of the conversion tool. These are hosted by community members who've taken responsibility for keeping the tool available. Christopher Klay's version is probably the most reliable, since Klay has experience maintaining Stadia-related projects and has credibility in the community.

Alternatively, if you're technically inclined, you could clone the Git Hub repository and run the conversion tool locally. This gives you the most control and doesn't depend on anyone else's hosting. The code is open, so you can verify what it's actually doing before you run it on your controller.

The important thing to understand is that the preserved versions of this tool are safe. They're not malware or scams. They're the actual Google tool, preserved by people in the community who care about not letting useful technology disappear.

However, there's one caveat: the Stadia controller does need to be in relatively good condition to convert successfully. If the battery is dead, if the wireless module is damaged, if there's a hardware fault, the conversion might not work. But if the controller is functional, the conversion process is straightforward and reliable.

The process itself hasn't changed. You still put the controller in pairing mode. You still connect it to the tool. The tool still reprograms the firmware. And a few minutes later, you've got a Bluetooth gamepad.

Why Community Preservation Matters for Future Tech

Here's the thing that actually keeps me thinking about this story: it's going to matter a lot more in the future.

We're living in an era where most of our technology is controlled by corporations. Your phone runs on software made by Apple or Google. Your games run through platforms made by Valve, Sony, Microsoft, or Nintendo. Your music comes from Spotify or Apple Music. Your photos are stored in Google Photos or i Cloud. Your documents are in Google Drive or One Drive.

This dependence on corporate platforms creates a vulnerability. When those companies change their minds, when they decide a service isn't profitable, when they get acquired by something bigger and the service gets shut down, you lose access to what you've built and what you own.

We've seen this happen over and over. Google Reader was shut down. Google+ was eliminated. Tumblr's adult content ban drove users away. Elon Musk's Twitter changes drove users to alternatives. Facebook's algorithm changes destroyed news outlets' traffic. Every time a platform makes a decision to kill something, people are left holding the bag.

The Stadia story is actually relatively optimistic. Google at least refunded money. Google at least provided a conversion tool. Google didn't try to prevent the community from preserving tools. Compare this to Apple, which has become increasingly aggressive about preventing users from repairing devices or modifying software.

But what the Stadia story really shows is that when corporate decisions affect users, communities can respond. Not always successfully. Not always easily. But it's possible. And it's becoming more socially normalized.

Right now, the people who can participate in community preservation efforts are those with technical skills. Christopher Klay can do this because Klay knows how to host code on Git Hub, understand web applications, and maintain infrastructure. Not everyone has these skills.

But as these practices become more common, as more people learn that these tools exist and how to use them, the barrier gets lower. Someone doesn't need to be a developer to use a preserved tool. They just need to know it exists and trust the people who preserved it.

This could become foundational to how we relate to technology. Instead of assuming that when a corporation kills something it's gone forever, we assume that communities might preserve it. Instead of feeling helpless when services shut down, we know that there are people working to keep important tools available.

It's not a perfect solution to corporate control of technology. The best solution would be for companies to not kill their products so frequently, or to open-source them when they do. But short of that, community preservation is the next best thing.

The Stadia Bluetooth conversion tool was available from the shutdown announcement in September 2022 until its removal in October 2025. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: Hardware Abandonment in Tech

The Stadia controller conversion tool is just one example of a broader problem: hardware abandonment.

When a company kills a service, what happens to the hardware that supported it? Usually, it becomes waste. Thousands of Stadia controllers were sold. Most of them are now sitting in drawers or landfills because the service they were designed for no longer exists.

This isn't unique to Stadia. Google Glass was abandoned as a consumer product, leaving early adopters with expensive hardware that nobody could use. Amazon's Fire Phone was killed, leaving people who bought it with an increasingly obsolete device. Microsoft's Kinect for Xbox 360 was eventually discontinued, making the hardware worthless once the service ended.

Every failed tech product creates hardware orphans. Devices that were designed with one specific purpose and no real flexibility to do anything else once that purpose disappears.

The Stadia controller is actually better than most of these examples because the hardware is flexible enough to be repurposed. It's a Bluetooth gamepad at heart. It just needed a firmware change to unlock that capability. Once converted, it becomes useful again.

But many failed tech products don't have this flexibility. A smartwatch designed to work only with a specific service becomes a paperweight once the service dies. A voice assistant that requires cloud connectivity becomes useless if the cloud service gets shut down. Hardware that's locked down, that requires specific software to function, becomes wasteful the moment the service supporting it disappears.

This is why the Stadia story is actually hopeful. It shows that when you design hardware with some flexibility in mind, when you give users tools to repurpose it, the hardware can have a second life. And when the corporation doesn't provide those tools, communities can.

In the future, this might become a more important criterion for evaluating tech products. Does this hardware have a life after the service dies? Can it be repurposed? Can it be preserved? Or is this just going to become e-waste in three years when the company decides the service isn't worth continuing?

Apple and other manufacturers have started facing pressure on right-to-repair issues. This is a similar concept, just applied to services instead of repairs. The idea that when you buy a piece of hardware, you should have the right to use it even after the company stops supporting the service. The Stadia controller conversion tool is a precedent for that principle.

How Steam Became the Stadia Controller's Saving Grace

One important detail in this story is that the Stadia controller is now useful specifically because of Steam.

Valve's Steam is the dominant platform for PC gaming. It has been for nearly two decades. And a few years ago, Valve made an important decision: make Steam compatible with community controllers and custom input devices. This opened the door for all kinds of controllers to work with Steam games, even if the controllers weren't made specifically for Steam.

When you connect a Bluetooth gamepad to a PC with Steam running, Steam recognizes it. It maps the buttons. It provides haptic feedback support. It lets you customize the controls for different games. This is actually really important infrastructure that makes community preservation possible.

Without Steam's openness to third-party controllers, the Stadia controller conversion tool would matter a lot less. You'd have a Bluetooth gamepad, but there might not be anywhere useful to use it. The fact that Steam not only accepts the Stadia controller but actively supports it means that converting the controller gives you a genuinely useful tool for gaming.

This is maybe the most important lesson from the Stadia story: openness and compatibility matter. When platforms lock themselves down, when they only accept first-party hardware, when they restrict what third-party devices can do, it creates waste. When platforms are open, when they accept whatever hardware you want to connect, when they give you tools to customize and repurpose hardware, it creates possibilities.

Steam's controller support didn't exist for Stadia. There was no guarantee that Valve would ever make the Stadia controller work with Steam. But Valve's general philosophy of openness meant that when people converted Stadia controllers to Bluetooth, the controllers just... worked. They were recognized. They were supported. They were useful.

This suggests a model for the future where companies design their platforms to be open to community hardware and community preservation efforts. Where killing a service doesn't mean making all the hardware associated with it worthless. Where the exit from a platform can be handled gracefully, and hardware can have a second life in different ecosystems.

It's not a perfect story. Ideally, Google wouldn't have killed Stadia in the first place. Ideally, the platform would have succeeded and the controller would still be the default way to play Stadia games. But in the world where Stadia failed, this is about as good as it gets.

Converting the Stadia controller to Bluetooth significantly enhances its compatibility, ease of use, and flexibility, making it a versatile gaming tool. Estimated data based on typical user experience.

What We Know About Why Google Removed the Tool Now

Google removed the Stadia Bluetooth conversion tool this week, nearly two years after shutting down Stadia itself.

Why now? There's no official explanation from Google. The company hasn't announced the removal. It just quietly disappeared. But there are a few possible reasons to think about.

First, Google might be doing general cleanup. Two years is a reasonable amount of time to expect that people who wanted to convert their controllers have already done so. Keeping the tool around adds no value to Google. It uses server resources. It's a page that exists on their website for a product they don't make anymore. From Google's perspective, removing it is logical. It's cleanup.

Second, there might be business reasons. The Stadia controller itself might have been a licensed design that required royalties or ongoing payments to the manufacturers. By removing the conversion tool, Google removes the implicit suggestion that people should keep using Stadia controllers. It's a way of saying: "We're truly done with this product. There's no coming back."

Third, it might have been a mistake. It's possible that some junior engineer at Google noticed the Stadia conversion tool sitting on their servers and just deleted it without thinking about the implications. It wouldn't be the first time a company killed something by accident.

Regardless of why Google removed it, the point is that they did. And by removing it, they would have created a gap in the ability of people to repurpose their hardware—except that the community had already filled that gap by preserving copies.

This is the actual significance of the preservation effort. Google removing the tool would have been a problem if communities hadn't already made copies. But because they did, the removal doesn't actually matter. The tool is still accessible. People can still convert their controllers. The hardware can still have a second life.

The Bigger Picture: Google's Track Record with Service Shutdowns

To understand why the Stadia story matters, you need to understand Google's broader track record with killing products.

Google has shut down more services than almost any other company. Google Reader was an enormously popular RSS feed reader that had millions of users. Google killed it. Google+ was Google's attempt to compete with Facebook. It failed, and Google shut it down, forcing all the user communities that had formed there to find somewhere else to go. Google Hangouts was replaced by Google Chat. Google Play Music was replaced by You Tube Music. Google Sites has been through multiple redesigns that broke existing sites.

Google Domains is shutting down. Google will transfer existing registrations to Squarespace, but domain owners have to actively move their domains. Google's original messaging service, Google Wave, was an interesting concept that the company abandoned after a few years.

The list goes on. And on. And on.

Google is a company that launches services, finds out they're not getting the scale or profit margins the company wants, and shuts them down. Sometimes the company gives advanced notice. Sometimes there's a migration path. But often, users are left scrambling.

In this context, the way Google handled the Stadia shutdown is actually remarkably respectful. The company gave months of notice. It refunded money. It provided a tool for users to convert their hardware to something useful. Google didn't have to do any of this. Google could have just deleted everything from the servers and called it done.

But Google did try. And when the company subsequently removed the conversion tool, communities stepped in to preserve it.

The contrast between Google's general pattern of abandonment and the fact that the community stepped in to preserve the conversion tool is actually the real story here. It's not a story about Stadia specifically. It's a story about whether technology communities are ready to be the institutions that preserve the things corporations abandon.

The Technical Details: How the Conversion Actually Works

For people who are curious about the technical side of what's happening, let's talk about how the Stadia controller conversion actually works.

The Stadia controller is built around a wireless module that supports both Stadia's proprietary wireless protocol and standard Bluetooth. The hardware is capable of both. But the firmware—the software embedded in the controller's hardware—was locked to only use the Stadia proprietary protocol.

Google's conversion tool doesn't alter the hardware at all. It doesn't require opening the controller or soldering anything or installing custom firmware. It just reprograms the existing firmware that's already on the controller.

When you connect the controller to the conversion tool via USB, the tool establishes a communication channel with the controller's firmware. The tool sends instructions to the firmware to switch from Stadia mode to Bluetooth mode. The controller's wireless module receives these instructions and reconfigures itself.

Once the conversion is complete, the controller's wireless module stops looking for Stadia's servers. Instead, it starts broadcasting itself as a standard Bluetooth device. It pairs with other devices the same way any Bluetooth controller would. The button mapping, the analog stick configuration, the haptic feedback system—all of this continues to work, but now it's talking to Bluetooth devices instead of Stadia's infrastructure.

This is actually the elegant part of the design. Google built the Stadia controller to be capable of working as a Bluetooth gamepad from the hardware level. The company just locked it down in software. The conversion tool is just unlocking what was already there.

This is why the preservation of the tool is so important. The firmware already supports Bluetooth. The hardware is capable of it. The only thing preventing Stadia controllers from being regular gamepads is software. And once someone has preserved a copy of the tool that makes that software change, the controller can be converted indefinitely, no matter how many times Google removes pages from their servers.

For comparison, imagine if the Stadia controller had been built to only work with Stadia's servers at the hardware level. Imagine if the wireless module couldn't do Bluetooth without completely replacing the module. Then the conversion tool would be much less important. Once Google deleted the tool, the controllers would actually be obsolete.

But because of how the hardware was designed, the preservation of the software tool is enough to keep the hardware useful.

Learning from Stadia's Mistakes

The Stadia story is ultimately a story about failure. But it's also a story with lessons for anyone designing consumer technology.

Lesson one is about hardware longevity. Build hardware that can do something useful even when the service it was designed for no longer exists. The Stadia controller was designed this way, and that decision means the hardware is salvageable. If it had been locked down at the hardware level, the hardware would be garbage once Stadia died.

Lesson two is about being honest with your customers. Google refunded money when it shut down Stadia. Google provided a tool for converting hardware. Google didn't try to force people to buy replacement hardware or accept that their purchase was a total loss. This is the opposite of how some companies handle service shutdowns. It's worth noting that Google did this. It's worth praising companies that do.

Lesson three is about the limits of corporate goodwill. Google's refunds and conversion tool were nice. But the company still eventually removed the conversion tool from its servers. It's easy to interpret this as the company saying: "We're done being nice now. We've fulfilled our obligation. The rest is on you."

This is where community preservation comes in. If everyone had depended on Google to keep the tool available forever, it would be gone. But because communities preserved copies, the tool is still available.

Lesson four is about the value of open infrastructure. Steam's willingness to support third-party controllers meant that once the Stadia controller was converted to Bluetooth, it immediately became useful. There was somewhere to use it. If Steam had been locked down to only support first-party controllers, the converted Stadia controller would still have no place to go.

Lesson five, maybe the most important, is about communities and preservation. When corporations abandon products, communities can often step in. Not always. Not for everything. But sometimes, if people care enough, if the right technical skills are present, if the infrastructure exists to preserve and share that preservation, products and tools that would otherwise disappear can be saved.

These lessons matter for every technology company and every consumer. Stadia is dead, but it's not completely dead. The hardware lives on. The tools live on. The community that cared enough to preserve them made sure that failure wasn't absolute.

Looking Forward: What Happens When the Next Service Dies

Stadia won't be the last service that dies. There will be more cloud gaming platforms that fail. There will be more digital services that get shut down. There will be more hardware that becomes orphaned.

The question is whether the community preservation model that worked for Stadia will become the norm, or whether it'll be the exception.

Right now, it's the exception. Most people don't know about the preserved Stadia conversion tool. Most people don't know that communities can step in to preserve tools. Most people assume that when a service dies, everything associated with it is gone forever.

But awareness is growing. Every time a popular service shuts down, more people learn that communities are preserving copies. More people learn that it's possible to save things that corporations are abandoning. More people start thinking about what tools and services matter enough to preserve.

The next time Google kills a service, or Microsoft, or Apple, or any other company, there will be communities ready to preserve it. There will be Git Hub repositories. There will be mirrors hosted on independent infrastructure. There will be documentation about how the service worked and how to use it after it's been shut down.

This could become foundational to how we relate to digital technology. Instead of treating every service as something that might disappear at any moment, we could treat it as something that communities will preserve if it matters to them.

Of course, this isn't perfect. Community preservation requires technical skills that not everyone has. It requires infrastructure that not everyone can provide. It requires motivation that only exists if people actually care about preserving something.

But it's better than the alternative, which is accepting that everything corporations kill just disappears forever. It's better than assuming that all technology is fundamentally temporary and disposable.

Stadia is gone, but the community proved that some part of it can live on. And that matters.

The Human Element: Why Communities Preserve What Corporations Abandon

There's a human element to this story that's worth understanding.

Christopher Klay didn't have to preserve the Stadia conversion tool. Klay could have let it disappear. Klay could have moved on to other projects. There was no financial incentive. No one was paying Klay to do this. It wouldn't make Klay famous or build toward a career goal.

Klay did it because Klay cared. Klay had invested time and energy in Stadia, in Stadia Enhanced, in the community around the platform. When that platform was going to disappear, Klay made a choice to preserve part of it.

This is increasingly common in tech. When corporations fail to act, communities step in. When companies abandon users, communities support each other. When services die, communities preserve them.

This happens because individual people—developers, engineers, enthusiasts—care about the work they've done and the communities they've been part of. They care enough to spend their time and use their skills to preserve things, even when no one is asking them to and no one is paying them.

It's actually an interesting inversion of what we usually think about technology. We usually think about technology as being created by companies and corporations. We think about Apple, Google, Microsoft, Meta as the institutions that shape the technological world. And they do.

But then when those companies fail or change directions, it's communities of individual people who step in to preserve what matters. It's not organized by any corporation. It's not part of any official strategy. It's just people deciding that something is worth saving and doing the work to save it.

In the future, as corporations become even more dominant in technology, as more of our world is controlled by software and digital services, the role of communities in preservation might become even more important. We might be building toward a world where communities are the institutions that preserve technology, just as they've always been the institutions that preserve knowledge and culture in other domains.

Stadia is just one example, but it's an important one because it shows that this preservation is possible. It shows that when someone has the skills and the motivation, they can save things that corporations are abandoning. And once it's saved, it's available to everyone.

Practical Considerations: Safety and Reliability

If you're thinking about using one of the preserved Stadia conversion tools, there are some practical considerations.

First, safety. Is it safe to run code that's been preserved on Git Hub? Generally yes, if the repository comes from someone with a good track record. Christopher Klay has built community tools before. Klay has credibility. The code is open source, which means anyone can review it to make sure it's not doing anything malicious. Thousands of people have probably already reviewed the code and would have said something if there was a problem.

Second, reliability. Will the conversion tool still work, or has it broken due to changes in operating systems or browsers? Generally, it should still work. The conversion tool wasn't dependent on any specific version of Windows or Mac or Chrome. It was a simple web application that connected to a Stadia controller via USB and sent firmware update commands. As long as your browser can still do USB connections—which it should—the tool should work.

Third, compatibility. Will your Stadia controller actually convert? Probably. The Stadia controller hardware was designed to support Bluetooth. If the controller is in good working condition, if the battery is charged, if the wireless module is functioning, the conversion should work.

There are edge cases. If your controller's battery is dead, you might need to replace the battery before conversion. If the wireless module was damaged, conversion might not be possible. If you've modified the controller's hardware, conversion might not work correctly. But in general, if your Stadia controller is in normal condition, the conversion tool should work.

Fourth, what happens after conversion? Your Stadia controller becomes a Bluetooth gamepad. It will work with any device that accepts Bluetooth controllers. It will work with PC, with Steam, with Mac, with phones and tablets that support gamepad input. The buttons, the analog sticks, the haptic feedback—it all continues to work exactly as before, but now talking to Bluetooth instead of Stadia's servers.

Fifth, is there any risk to the conversion? Not really. The conversion is just a firmware update. If the conversion doesn't complete successfully, you can usually try again. It's not like you're permanently modifying the hardware in a way that can't be undone.

So practically speaking, if you have a Stadia controller and you want to convert it to Bluetooth, using the preserved tool is pretty safe and pretty reliable. The main thing is finding the preserved tool and trusting that it's what it claims to be. Christopher Klay's version has been used by thousands of people at this point. If there was a problem, it would be known.

Why This Story Matters Beyond Stadia

I keep coming back to why this story matters because Stadia is dead. Nobody's building games for Stadia. Nobody's using Stadia's streaming technology. Stadia is completely irrelevant to the current gaming landscape.

But the story of community preservation, the story of what happens when corporations abandon products and communities step in, that story is very relevant. That story is going to matter more and more as technology becomes increasingly dominated by corporate platforms.

Right now, most of the technology we use is controlled by companies. Your phone is controlled by Apple or Google. Your games are controlled by Valve, Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo. Your social media is controlled by Meta. Your communication is controlled by tech companies. Your documents, your photos, your videos, your music—all controlled by tech companies.

This concentration of control creates vulnerability. When companies change their minds, when they decide a service isn't worth continuing, when they prioritize different business models, users are at the mercy of those decisions.

The Stadia story shows that it doesn't have to be absolute. When companies kill things, communities can preserve them. Not everything can be preserved. Not everything can be saved. But some things can. And that matters.

In the future, communities might be a bigger part of the technological landscape than they are now. Not as companies, not as corporations, but as institutions that preserve and maintain the technology we care about when the companies that made it decide to move on.

This could be good. It could be bad. It could be both. But it's coming, and Stadia is just an early example of how it works.

Conclusion: A Service Ends, But the Hardware Lives On

Google's decision to remove the Stadia Bluetooth conversion tool from its servers is another moment in the slow death of Stadia. But it's also a moment where we can see communities stepping in to preserve technology and keep hardware useful even after the company that made it has abandoned it.

Stadia failed. Google spent billions of dollars building a cloud gaming platform that nobody wanted to use. The company admitted defeat, shut down the service, and moved on. The hardware—the Stadia controllers—could have become e-waste. They could have been thrown away. They could have become a monument to corporate failure, useful only as paperweights.

But they didn't. Because Google provided a conversion tool, because communities preserved that tool before it was deleted, because Stadia controllers are now Bluetooth gamepads that work with Steam and PC games and other devices, the hardware lives on. It has a second life. It's useful.

Is this a redemption story for Stadia? Not really. Stadia is still a failure. The service is still dead. The money Google spent is still wasted. The mistake of launching a platform that was technically interesting but not what people actually wanted is still a mistake.

But it's a redemption story for the hardware. It's a redemption story for the people who bought controllers. It's a redemption story for community preservation and for the idea that when corporations abandon technology, communities can save it.

In the future, this might be more important. As technology becomes more controlled by corporations, as more services are built only to be shut down when they don't meet corporate profit expectations, the ability to preserve and repurpose hardware and software might be the difference between waste and sustainability.

The Stadia controller conversion tool was a small thing. Converting a controller takes ten minutes. It's not a major technological achievement. But it represents something bigger: the idea that even when companies give up on technology, the people who care about that technology can keep it alive.

Stadia is dead. But parts of it can still be rescued. And that matters.

FAQ

What was Google Stadia and why did it fail?

Google Stadia was a cloud gaming platform launched in 2019 that allowed users to stream games directly from Google's servers instead of running them locally on a console or PC. The service failed because streaming technology wasn't mature enough to compete with local gaming latency, the game library was too limited, Google had a poor track record of abandoning services, and the overall value proposition unclear—most gamers already had either gaming PCs or consoles. Google shut down Stadia completely in January 2023, less than three years after launch, after spending approximately $2.75 billion on development and marketing.

How does the Stadia controller Bluetooth conversion work?

The Stadia controller contains a wireless module that's physically capable of supporting both Stadia's proprietary protocol and standard Bluetooth. Google's conversion tool reprograms the controller's firmware over USB to unlock the Bluetooth functionality without requiring any hardware modifications. When you connect the controller to the conversion tool, it establishes communication with the controller's firmware and sends instructions to switch from Stadia mode to Bluetooth mode. Once complete, the controller broadcasts itself as a standard Bluetooth device and can pair with any Bluetooth-compatible platform including PC, Steam, phones, and tablets.

Why did the community preserve the Stadia conversion tool?

Community members, including Christopher Klay who previously developed the Stadia Enhanced browser extension, recognized that the conversion tool was useful and might disappear when Google eventually removed it from their servers. By preserving copies on Git Hub and other public repositories before the deletion, these developers ensured that people could still access the tool even after Google removed it. This reflects a broader community value of preserving technology when corporations abandon it, preventing hardware from becoming waste and allowing it to have a second life in new ecosystems.

Is it safe to use the preserved Stadia conversion tool?

Yes, using the preserved Stadia conversion tool is safe, particularly from trusted sources like Christopher Klay's repository. The code is open source, meaning anyone can review it for malicious content, and thousands of people have already used it successfully. The conversion process itself is just a firmware update that won't permanently damage the controller if something goes wrong. As long as your Stadia controller is in working condition with adequate battery, the conversion should complete successfully and reliably.

What can I do with a converted Stadia controller?

Once converted to Bluetooth, your Stadia controller becomes a fully functional Bluetooth gamepad that works with any device accepting Bluetooth controller input. This includes Windows PCs, Macs, Steam, phones, tablets, and potentially game emulators. Steam in particular has excellent support for the converted Stadia controller, properly mapping buttons and supporting haptic feedback. The controller maintains all its original features—buttons, analog sticks, D-pad, and haptic feedback—but now talks to Bluetooth devices instead of Stadia's servers.

Why does this matter for the future of technology?

The Stadia preservation story demonstrates that when corporations kill products, technical communities can step in to preserve useful tools and prevent hardware from becoming electronic waste. As technology becomes increasingly controlled by corporate platforms, this pattern of community preservation might become more important for maintaining access to tools and preventing entire categories of hardware from becoming useless when companies decide to shut down services. This creates an alternative to planned obsolescence where communities help extend the useful life of hardware and software beyond their original corporate lifecycle.

Where can I find the preserved Stadia conversion tool?

The preserved Stadia conversion tool is available on Git Hub through repositories maintained by community members including Christopher Klay. These mirrors host a working copy of Google's original conversion tool, allowing users to convert their controllers even though Google has removed the tool from its official servers. You can find these repositories by searching for "Stadia controller Bluetooth conversion" on Git Hub, and you'll find multiple preserved versions maintained by the community.

Will the preserved tool continue to work in the future?

The preserved tool should continue working for the foreseeable future because it was designed as a simple web application that communicates with the Stadia controller over USB without depending on specific operating system versions or browser updates. The core USB protocol and firmware update mechanism haven't changed, so as long as your browser continues supporting USB connections—which it should—the tool should remain functional. However, like any community-maintained project, its future depends on continued community interest and maintenance.

Key Takeaways

- Google removed the Stadia Bluetooth conversion tool but developers had already archived it on GitHub, ensuring community preservation

- The Stadia controller's hardware was always capable of Bluetooth—Google just locked it down with software that the conversion tool unlocks

- Christopher Klay and other developers demonstrated how communities can rescue hardware and prevent e-waste when corporations abandon products

- Steam's openness to third-party controllers meant the converted Stadia controller found immediate practical use in the PC gaming ecosystem

- This preservation precedent shows how future abandoned tech might be saved through community effort, challenging the assumption that corporate product failure means total obsolescence

Related Articles

- PlayStation Portal: Is It Worth Buying in 2025? [Honest Review]

- Lenovo Legion Go 2 SteamOS: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Sony Marathon DualSense & Pulse Elite: Limited Edition PS5 Gear [2025]

- Hyperpop PS5 DualSense Controller & Console Cover Pre-Orders [2025]

- Civilization VII on Apple Arcade: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- CES 2026 Tech Trends: Complete Analysis & Future Predictions

![Google Stadia's Final Death: How Developers Rescued the Bluetooth Controller [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-stadia-s-final-death-how-developers-rescued-the-bluet/image-1-1768939686488.jpg)