Introduction: A Century of Evidence in Our Hair

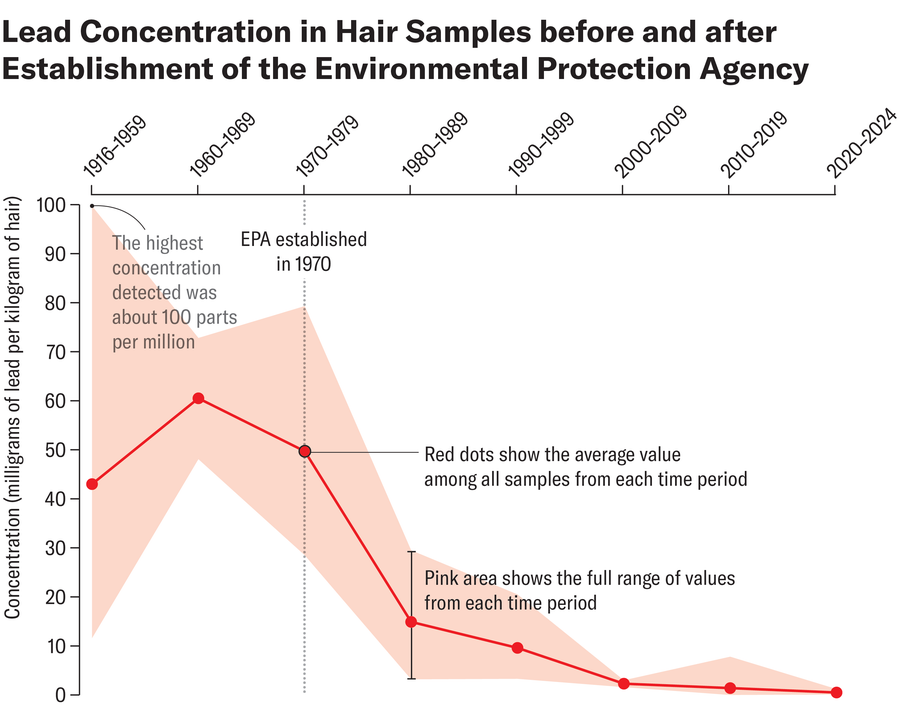

Something remarkable is hiding in your hair right now. Not just the usual dust and oils, but a chemical record of where you've lived and what you've breathed. Scientists at the University of Utah discovered this when they analyzed nearly 100 years of hair samples from Utah residents and found something striking: lead concentrations dropped by 100-fold over the past century, and the timing tells a story about one of the most successful environmental regulations in American history.

This isn't just another environmental victory story. It's evidence at the molecular level that government regulation actually works, presented at a moment when that evidence matters more than ever. With growing pressure to dismantle EPA enforcement and concerns about deregulation, researchers felt compelled to publish their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences as a reminder of what we achieved when we took lead seriously.

The research is straightforward but powerful. Human hair acts as a biological time capsule. As you breathe contaminated air or ingest lead-laden particles, some of that lead gets incorporated into your hair as it grows. Older hair holds older evidence. By collecting hair samples from the same Utah residents across decades—some even preserved in family scrapbooks from the early 1900s—the researchers could map lead exposure across an entire century. What they found was a dramatic decline that perfectly mirrors the EPA's phase-out of leaded gasoline starting in the 1970s.

But this story isn't really about hair. It's about how policy changes the body, how regulation saves lives, and why understanding history matters when we make decisions about our environmental future. The evidence is literally written into our biology.

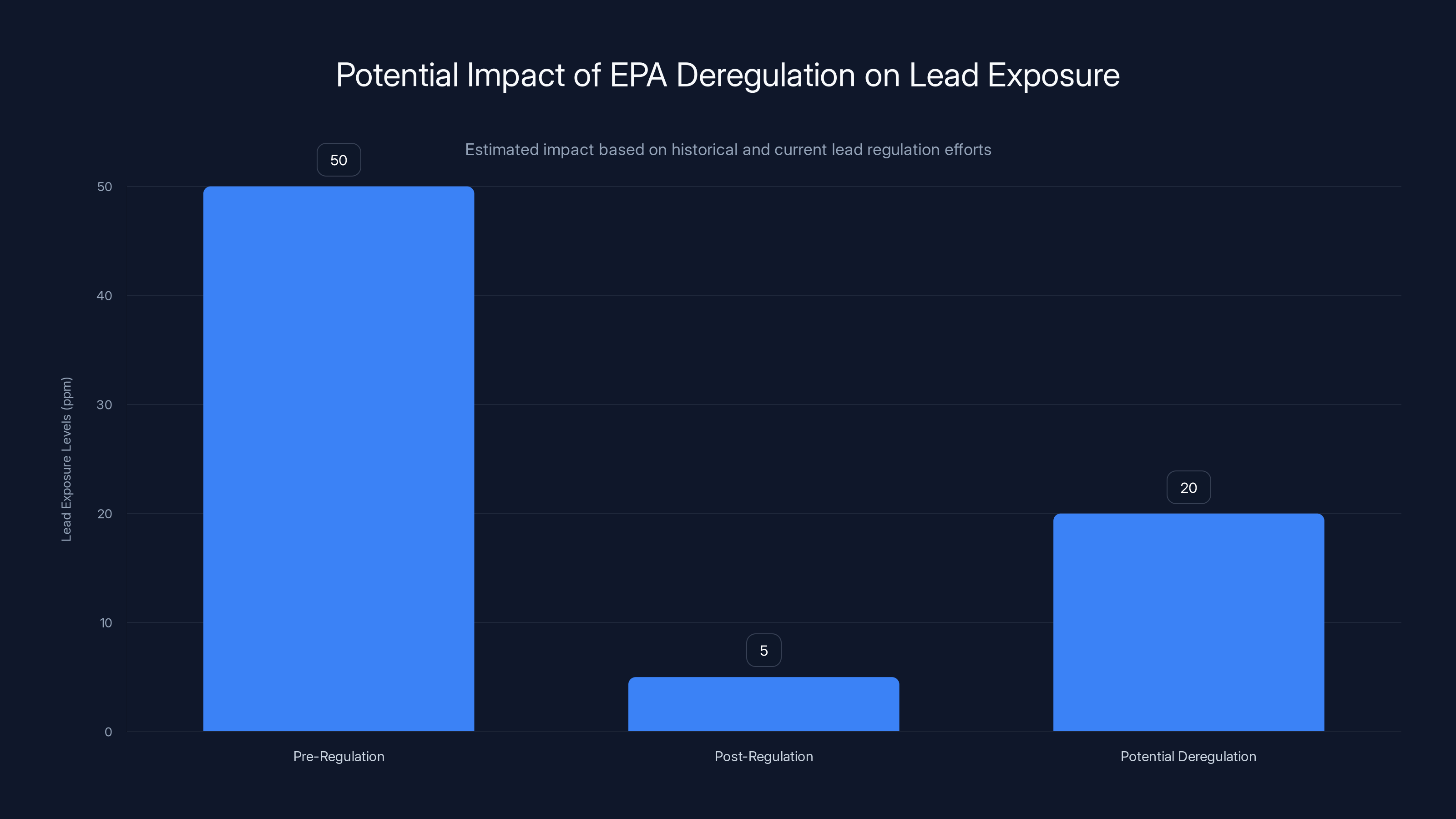

Lead concentrations in hair samples have declined significantly, showing a 100-fold decrease from peak levels in the 1960s to current levels, reflecting the impact of regulatory measures.

TL; DR

- 100-fold decline: Lead concentrations in human hair dropped from 100+ parts per million in the 1960s to less than 1 ppm by 2024

- Timing matters: The dramatic drop coincides precisely with the EPA's leaded gasoline phase-out beginning in 1970, proving regulatory action worked

- Biological evidence: Hair acts as a natural lead detector, accumulating environmental lead on its surface as it grows

- Policy impact: Prior to EPA regulation, Americans absorbed nearly 2 pounds of lead annually from automotive exhaust alone

- Current concerns: The research was published partly in response to growing threats to EPA enforcement and potential deregulation of lead protections

Estimated data shows a decline in lead concentration in hair samples over the decades, reflecting reduced environmental lead exposure.

The Forgotten Danger: Why Lead Was Everywhere

Lead wasn't always seen as dangerous. For most of the 20th century, it was treated as a miracle chemical—a solution to a specific industrial problem that nobody was paying close attention to the toxic consequences. Understanding how lead became so ubiquitous requires going back to the 1920s, when a fundamental chemical problem needed solving.

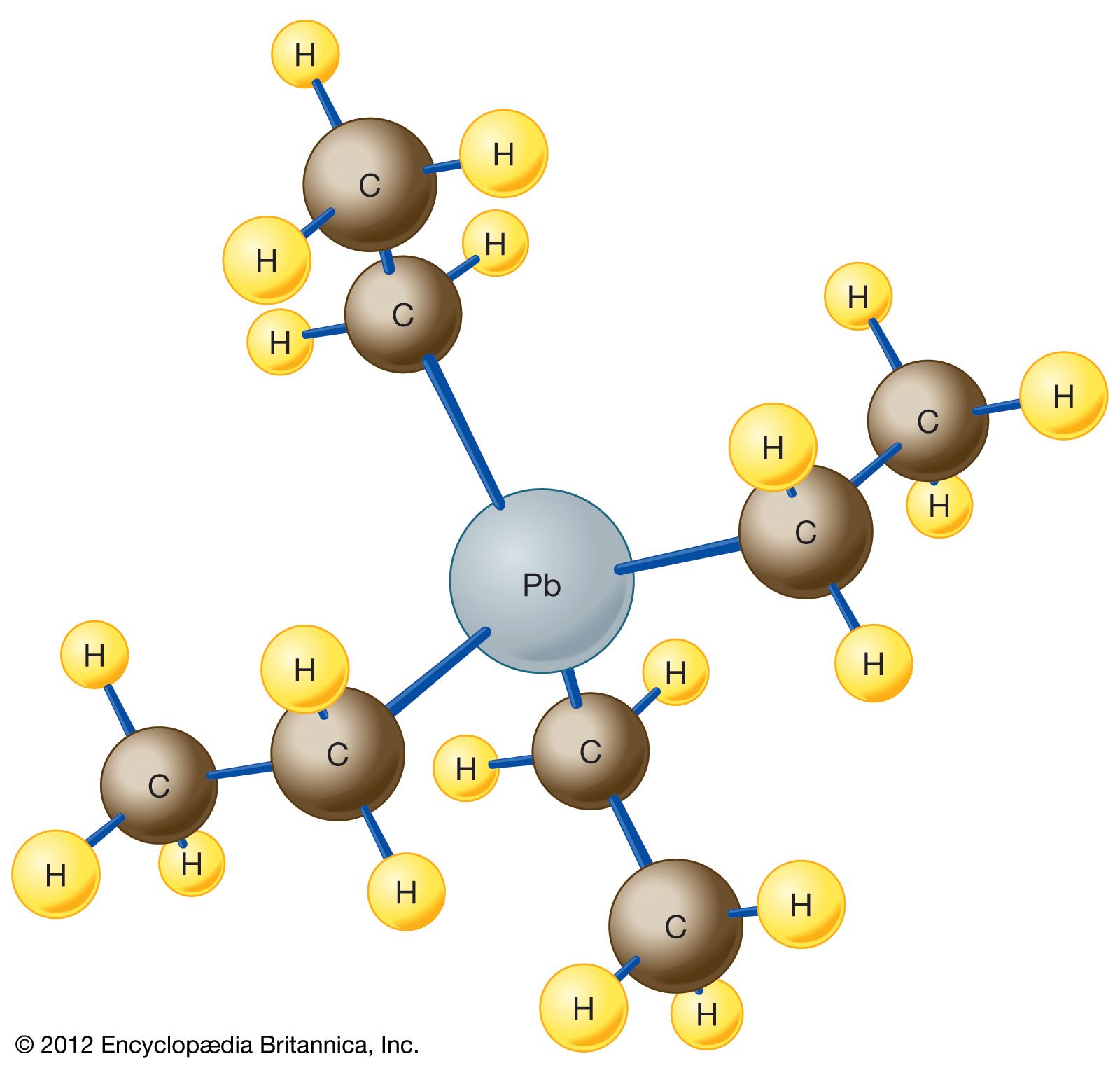

Automobile engines knock, ping, and run rough under load because gasoline ignites unevenly in the combustion chamber. This pre-detonation damages engines, reduces efficiency, and limits how much power you can extract from a gallon of fuel. In the early 1920s, engineers were stuck. They needed a fuel additive that would smooth combustion and let them build higher-compression engines, but nothing worked reliably. Then Thomas Midgley Jr., a mechanical and chemical engineer at General Motors, discovered something remarkable: adding tetraethyl lead (TEL) to gasoline eliminated the knock problem almost completely.

TEL was perfect for the purpose. It worked at tiny concentrations, required no expensive modifications to existing engines, and solved the problem immediately. From an industrial perspective, it was a miracle. General Motors, Du Pont, and Standard Oil formed a partnership to produce it, and leaded gasoline rolled out starting in 1923. The problem was solved. The industry could move forward. Nobody really asked what happened to all that lead.

What happened was that it went straight into the air and into people's bodies. Before the EPA cracked down in the 1970s, most gasoline contained about 2 grams of lead per gallon. For an average driver consuming 500 gallons annually, that worked out to a kilogram of lead per year per vehicle. Multiply that across millions of vehicles burning millions of gallons daily, and you're looking at an enormous environmental lead contamination problem that didn't spark serious concern until decades later.

Midgley himself was aware of lead's dangers on some level—he had actually experienced lead poisoning from his work developing TEL. But rather than acknowledge the risk publicly, he downplayed it. In a famous 1924 press conference, he poured TEL on his hands and inhaled its vapors for 60 seconds, claiming to suffer no ill effects. This was largely theater designed to calm public fears. He subsequently took a leave of absence from work due to lead poisoning, but this contradiction between his public statements and his private suffering was never widely publicized.

The auto industry, petrochemical companies, and the medical establishment were largely silent on lead's dangers despite growing evidence. Lead's neurotoxicity was actually well-understood by scientists as far back as the 1920s, but this knowledge didn't filter into mainstream awareness or regulatory action. The problem sat festering for decades while millions of Americans breathed contaminated air and absorbed lead through their lungs and food chain. Lead was everywhere—in gasoline, in paint, in solder used to seal canned foods, in dust settling on playgrounds where children played. It became so ubiquitous that people stopped thinking of it as a contaminant and started thinking of it as just part of the modern world.

Clair Patterson: The Scientist Who Took On an Industry

Every villain needs a hero, and leaded gasoline had one: a Caltech geochemist named Clair Patterson. Patterson's career took an unexpected turn when he decided to calculate the age of the Earth. Working with colleague George Tilton, he developed lead-dating methods and used them to analyze the Canton Diablo meteorite, a chunk of space rock that had fallen to Earth. His calculations showed the Earth was approximately 4.55 billion years old—remarkably close to the modern estimate and far more accurate than previous attempts.

But in conducting this research, Patterson noticed something disturbing. His laboratory measurements kept coming back contaminated with background lead. He couldn't get a clean sample. He spent years investigating where this lead was coming from, testing everything—his instruments, his lab water, his chemicals. The answer shocked him: the lead was coming from the air itself. Atmospheric lead contamination was so pervasive that even in a controlled laboratory environment, it was nearly impossible to avoid. His sensitive instruments were picking up lead pollution from the ambient environment.

This realization transformed Patterson from a geochemist into an environmental crusader. He began systematic studies of lead contamination across different environments and time periods. He measured lead in ocean water, in ancient ice cores, in human tissues. His work demonstrated that modern lead levels were roughly 1,000 times higher than pre-industrial levels. He found lead in canned foods from the lead-solder used to seal the cans. He found it in urban air, urban dust, urban soil. He made it clear, through rigorous scientific evidence, that leaded gasoline was a major culprit.

But Patterson was going up against powerful interests. The petroleum industry, the auto manufacturers, and the chemical companies had economic incentives to maintain the status quo. They funded studies questioning Patterson's research, funded scientists who downplayed lead's health effects, and lobbied regulators. Patterson's professional reputation suffered. He was attacked in scientific journals, excluded from advisory committees, and marginalized in certain circles. Research funding became harder to secure. But he persisted, publishing paper after paper, building an undeniable case that atmospheric lead was a public health disaster.

What gave Patterson's work real power was that it was rigorous, reproducible, and difficult to argue with. He wasn't making vague accusations. He was presenting quantitative data showing how much lead was in the environment, where it came from, and what it was doing to human health. He showed that lead accumulated in bones, that it interfered with neurological development in children, that it had no safe threshold of exposure. By the 1960s, his accumulated research had created a scientific consensus that leaded gasoline was a serious problem.

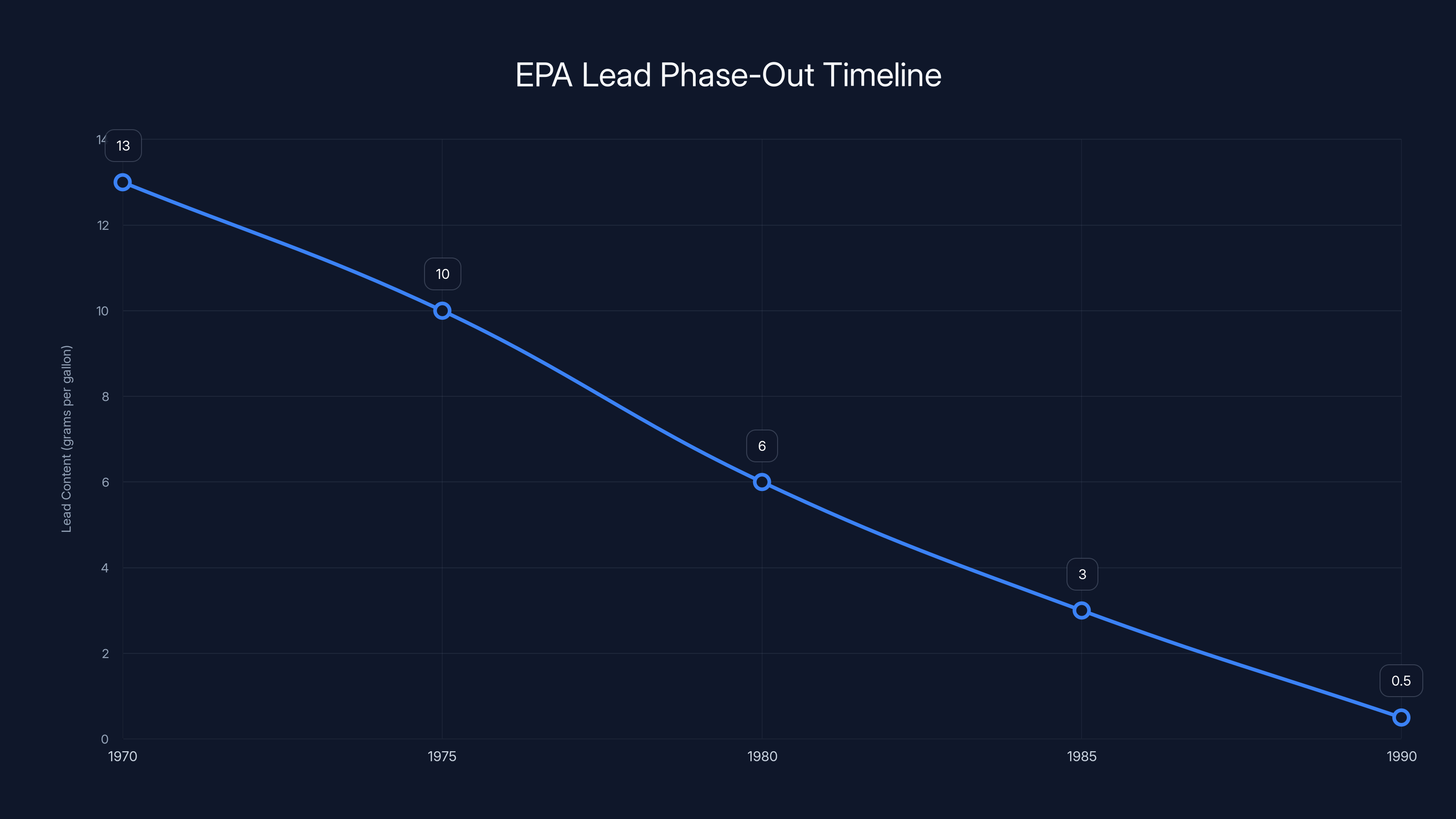

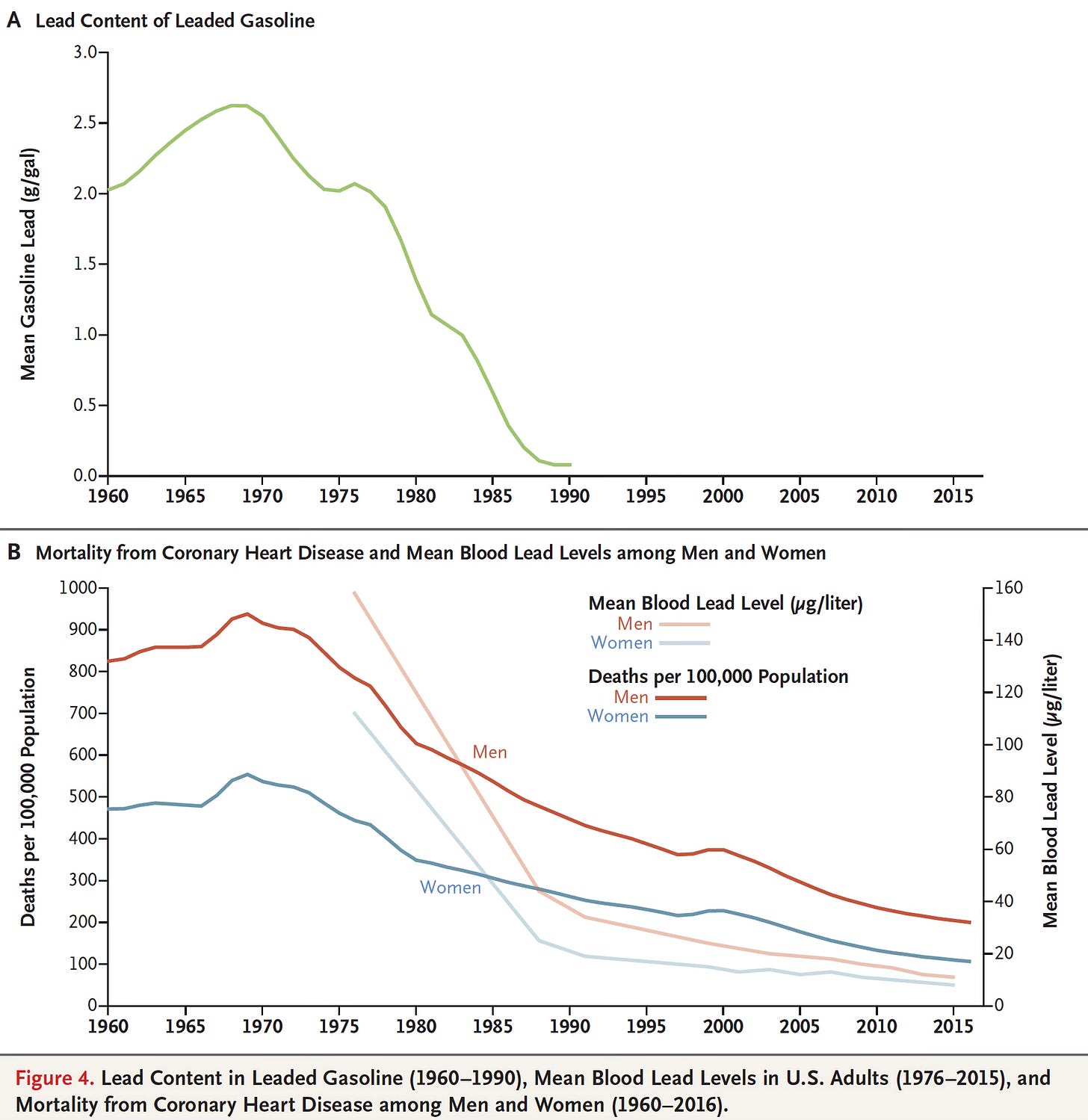

The EPA, established by President Nixon in 1970, began phase-out procedures. It wasn't a sudden ban—the regulation was carefully implemented to give refineries time to adapt. But it was definitive. Year by year through the 1970s and 1980s, the amount of lead allowed in gasoline was reduced. By 1986, leaded gasoline was phased out of standard automotive fuel in the United States. Patterson lived to see his vindication, though he died before the full health benefits of his crusade became statistically apparent.

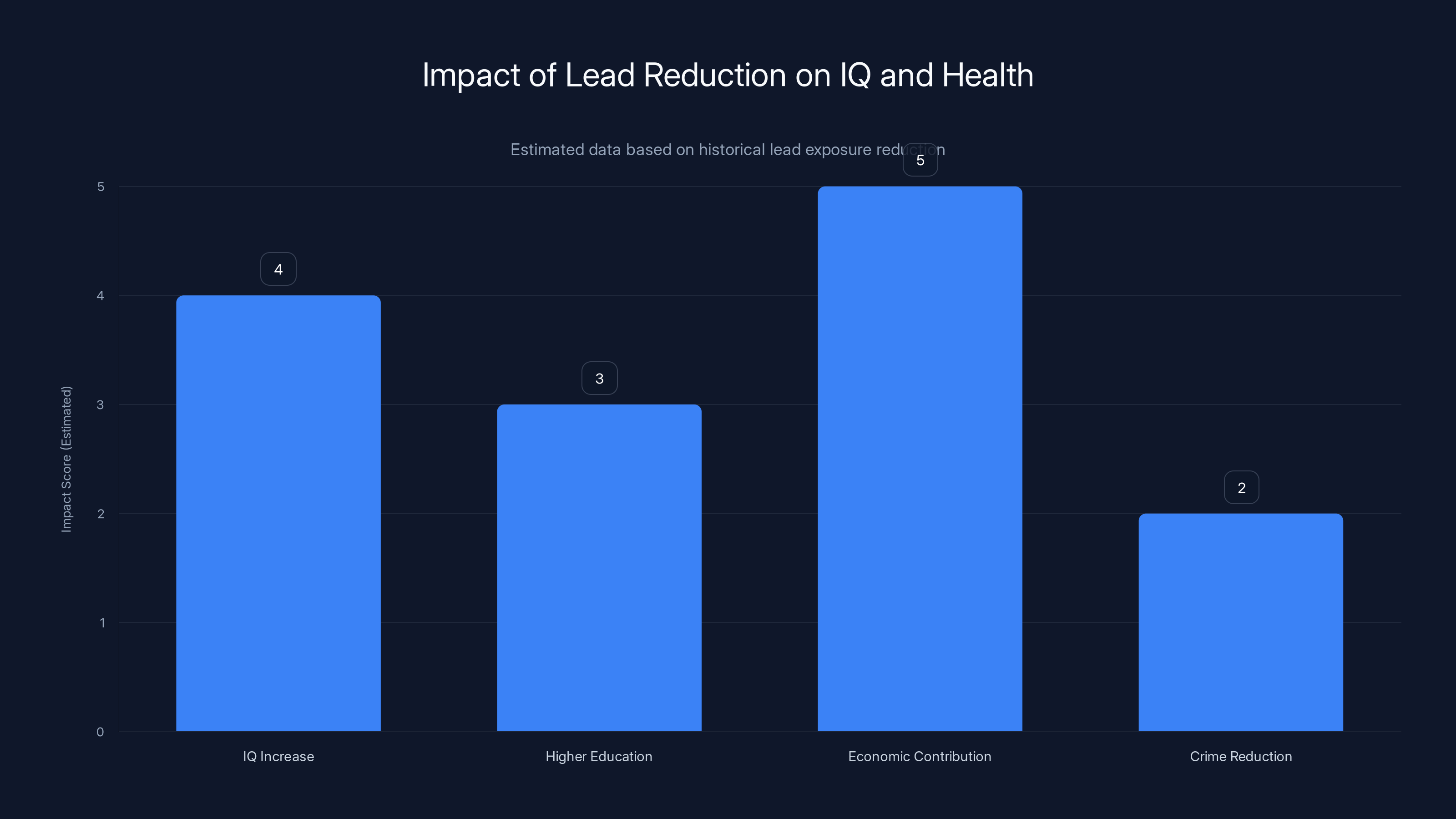

Estimated data shows that reducing lead exposure has led to an average IQ increase of 4 points, improved educational attainment, significant economic contributions, and reduced crime rates.

How Lead Actually Gets Into Your Body

Understanding the lead ban's success requires understanding how lead circulates through the environment and accumulates in human biology. Lead doesn't stay neatly in gasoline. When tetraethyl lead burns in an engine, it breaks down into metallic lead and lead compounds that exit through the exhaust as particles and vapor. These particles are small enough to be inhaled directly into the lungs, where they cross into the bloodstream. Some of the lead vapor enters the air as a gas that people breathe.

Once in the bloodstream, lead doesn't simply pass through and exit. It accumulates. Lead is chemically similar to calcium, so your body can't easily distinguish between them. Lead gets incorporated into bones, where it's stored for decades. Lead also crosses into soft tissues, including the brain, where it causes damage. In children especially, lead exposure during critical developmental periods interferes with neurological development, reducing IQ, impairing attention, and affecting behavioral control. These effects are dose-dependent but have no identified safe threshold—even low-level exposure causes measurable harm.

Beyond inhaling leaded exhaust directly, people accumulated lead through food and water. Lead dust settled on crops. Lead-soldered cans leached lead into food products. Lead pipes and lead solder in plumbing systems contaminated drinking water. Dust from old lead paint accumulated in homes. Lead from industrial smelters drifted downwind of the facilities. For someone living in an industrial area like Midvale, Utah, where smelting operations were a major industry, the cumulative exposure was enormous.

This is where hair comes in as a measurement tool. Thure Cerling and his research team recognized that hair could serve as a biological tape recorder of lead exposure. As hair grows, it incorporates elements from your bloodstream and from the environment. Lead concentrates on the surface of hair, where it can be detected using mass spectrometry—a highly sensitive analytical technique that can measure individual elements. More importantly, lead doesn't wash away or degrade in hair over time. A strand of hair preserved for 50 years still contains the lead that was there when that hair was growing.

This means you can collect hair from different periods of someone's life and build a timeline of their lead exposure. If you have hair that was growing in 1950, you can measure the lead concentration in that hair and know approximately how much lead that person was breathing in 1950. Collect hair from 1970, 1990, and 2024 from the same person, and you have a personal lead exposure timeline. Aggregate hundreds of people's hair samples across a century, and you have a map of how public health changed.

Cerling's team chose Utah specifically because it provided an ideal natural experiment. The Midvale and Murray region had smelting operations that processed ore containing lead for most of the 20th century. These smelters emitted enormous amounts of airborne lead. The region also had normal automotive traffic and atmospheric lead from the general leaded gasoline problem. Then, in the 1970s, both the smelters closed and the EPA began phasing out leaded gasoline. The lead exposure dropped sharply and stayed dropped. By looking at hair samples from Utah residents across this transition, the researchers could see the impact of both the smelter closure and the gasoline phase-out.

The Hair Study: Methodology and Evidence

The University of Utah research team conducted what amounted to an archaeological survey of a century of human biology. They recruited Utah residents who had participated in earlier blood lead studies, asking them to provide hair samples. But they didn't just collect current hair. They asked participants to provide hair they had saved over decades—hair that had been growing at different points in their lives. Some participants were able to contribute hair from 50 years earlier. Others were able to provide hair from family scrapbooks that their ancestors had kept, stretching the timeline back even further.

Cerling acknowledged that blood testing would have been ideal. Blood lead levels more directly reflect current internal exposure and the amount of lead circulating where it can cause damage. But blood must be tested immediately or preserved carefully, and you can't test century-old blood samples. Hair, by contrast, is chemically stable. A strand of hair preserved dry can last indefinitely. Lead doesn't degrade out of hair over time. This made hair the practical choice for a century-long study.

The researchers used cutting-edge mass spectrometry to measure lead concentrations in hair samples. They could do this with single hair strands—you didn't need large samples. The sensitivity was remarkable. They could measure lead concentrations down to parts per billion in many cases. The technique was destructive (the hair was consumed in testing), but the small sample size meant participants could provide hair without noticeable loss.

One interesting finding was that lead concentrations were higher on the surface of hair than throughout the interior. This suggested that lead was accumulating from environmental exposure—lead particles settling on the hair or being transferred through contact—as well as potentially being incorporated into the hair as it grew. The exact mechanism didn't matter for the study's purposes. What mattered was that the hair faithfully recorded environmental lead exposure over the decades.

The results were striking. Hair samples from the 1916–1969 period showed lead concentrations of 50–100 parts per million (ppm) or higher. These were people who had grown up and lived through the height of leaded gasoline use, industrial smelting operations, and before any lead-specific regulations. Then came the 1970s. As the EPA began restricting lead in gasoline and smelting facilities closed, the lead concentrations in hair began declining. By 1980, the concentrations had dropped to around 20 ppm. By 1990, they were below 10 ppm. By 2000, they were around 5 ppm. By 2024, hair samples showed lead concentrations below 1 ppm.

This 100-fold reduction is enormous. It translates to preventing millions of kilograms of lead from entering people's bodies. When you multiply that across the entire U. S. population over several decades, you're looking at massive improvements in human health. The research team estimated that this reduction represented approximately 35 million pounds of lead per year that is no longer being emitted into the atmosphere from automotive sources alone.

The timing of the decline is important because it allows us to attribute the change to specific policy actions. The steepest drops occurred during the 1970s and 1980s, exactly when the EPA was phasing out leaded gasoline. The decline slowed by the 1990s, as you'd expect once most lead had already been removed from gasoline. The continued low levels in recent years suggest that the benefit is sustained—lead in hair stays low as long as the regulations remain in place.

Cerling was particularly emphatic about what the data meant: "This study demonstrates the effectiveness of environmental regulations controlling the emissions of pollutants." He noted that regulations sometimes seem onerous to industry and slow down desired business activities. But the health outcomes speak for themselves. You can't see lead, can't taste it, can't smell it. Without regulation and the enforcement mechanisms to back it up, there would have been no reason for the petrochemical industry or auto manufacturers to change their behavior. The market alone didn't solve this problem. Policy did.

The phased reduction in lead content in gasoline from 1970 to 1990 shows how the EPA's regulatory approach gradually decreased lead levels, allowing industries time to adapt. Estimated data.

The Scale of Lead Exposure Before the Ban

To understand why this 100-fold reduction matters, you need to grasp just how pervasive lead exposure was during the pre-EPA era. The numbers are almost impossible to process because they're so large. Before 1970, every liter of leaded gasoline contained lead at concentrations around 0.5–1 grams per liter, depending on the specific formulation and region. The United States was burning roughly 300 million gallons of gasoline daily in the 1960s. That's approximately 600,000 pounds of lead being released into the atmosphere every single day.

Multiply that over a year: roughly 220 million pounds of lead per year in the 1960s-early 1970s. Spread across the entire U. S. population of roughly 200 million people at the time, that's more than 1 pound of lead per person per year entering the environment. For someone living in a city with heavy traffic, the personal exposure could be several times higher. For a child playing outside near a major highway, the exposure was even more concentrated.

This lead didn't disappear into thin air. It settled on every surface. It accumulated in soil. It entered the food chain through crops grown on contaminated soil. It contaminated water sources. It settled on playgrounds where children played in the dirt. It accumulated in homes as dust. The pervasiveness was absolute.

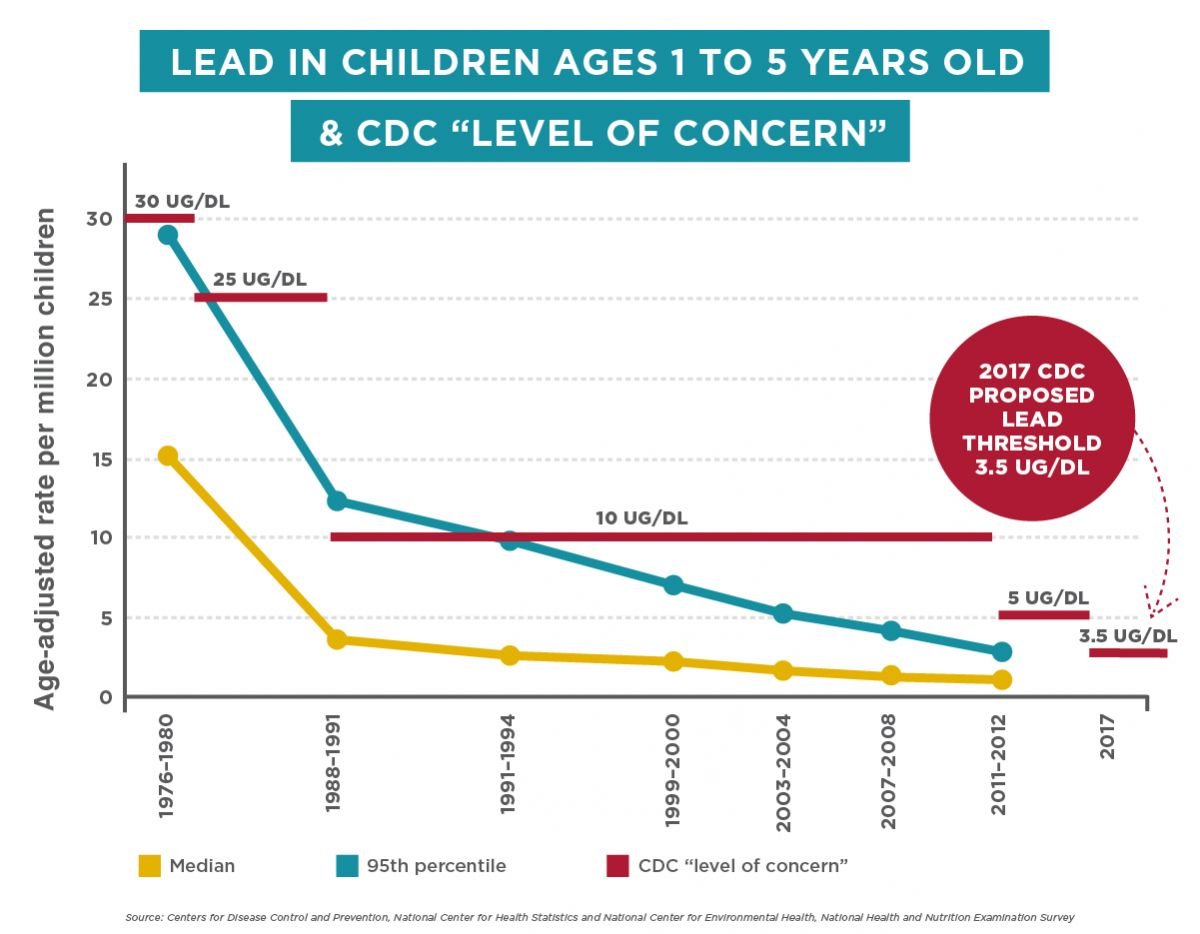

Add to the automotive lead the lead from industrial smelting, lead from paint (especially in older buildings), and lead from canned food containers, and you had a public health catastrophe that nobody was treating as urgent. The body burden of lead in the average American was correspondingly high. Blood lead levels that would alarm modern physicians—levels of 40–60 micrograms per deciliter—were normal. Some people had much higher levels.

The health consequences were severe but often attributed to other causes. Lead exposure causes neurological damage, particularly in children. IQ reductions, behavioral problems, learning disabilities, reduced adult earnings—these effects are now well-documented but weren't systematically tracked or attributed to lead in the pre-EPA era. Hypertension, kidney disease, reproductive problems—all of these were linked to lead exposure but weren't part of mainstream public health discourse. The lead was so ubiquitous that its health effects were treated as normal variation in human health rather than a solvable problem.

This is what makes the hair study so powerful as evidence. It's not arguing about policy or claiming environmental benefits. It's simply showing, through biological measurement, that before and after the EPA's actions, lead in human bodies dropped by 100-fold. The evidence is written into biology itself.

The Dramatic Timing: How Quickly Policy Changed Biology

One of the most striking aspects of the hair study is how quickly the biological evidence changed once policy changed. This isn't a slow, gradual improvement over centuries. It's a sharp decline happening in a matter of years. The researchers called this the "point source" problem—the lead wasn't coming from multiple sources that would take decades to address. It was coming primarily from cars burning leaded gasoline, and once you stopped allowing lead in gasoline, the atmospheric lead began declining almost immediately.

The EPA's regulatory approach was actually quite sophisticated, given the era. Rather than an immediate ban, they implemented a phase-out schedule that gave refineries time to adapt their operations, gave additive manufacturers time to develop alternatives, and gave the auto industry time to adjust engine designs. The lead content permitted in gasoline was gradually reduced year by year through the 1970s and 1980s.

1973: EPA began restricting lead content in new gasoline. 1974: Requirement for catalytic converters on new cars (which required unleaded fuel). 1975: Further restrictions on lead levels. 1982: Further reductions mandated. 1986: Leaded gasoline phased out for most vehicles. 1996: Final leaded gasoline phase-out.

This gradual approach had real advantages. It avoided disrupting the fuel supply entirely. It gave refinery operators and chemical engineers time to develop unleaded gasoline formulations. It gave car manufacturers time to retool engines to run on unleaded fuel. It was politically feasible in a way an immediate ban might not have been. And it worked. The phase-out was completed, lead in the environment declined sharply, and human health improved.

But the hair data shows something crucial: you didn't need a 20-year phase-out to see the benefit. By 1975, just 2–3 years into the regulatory process, hair samples show measurable declines in lead concentration. By 1980, the average lead levels had dropped by half. By 1990, they had dropped by 90% compared to the 1960s baseline. The biological response was almost immediate once the source of contamination was addressed.

This timing is important for evaluating the counterfactual. What would have happened if the EPA hadn't implemented the lead restrictions? Hair samples would presumably have stayed flat or continued rising as lead exposure continued. Children born in 1970 vs. 1990 would have had dramatically different lead exposures. The IQ benefits that researchers now estimate from the phase-out—improvements of several percentage points at the population level—would not have occurred. The hypertension rates, kidney disease rates, and other lead-related health problems would have continued climbing.

The hair study essentially says: here's what was happening before. Here's how fast it changed once policy changed. This is the difference between doing something and doing nothing. The biological evidence speaks for itself.

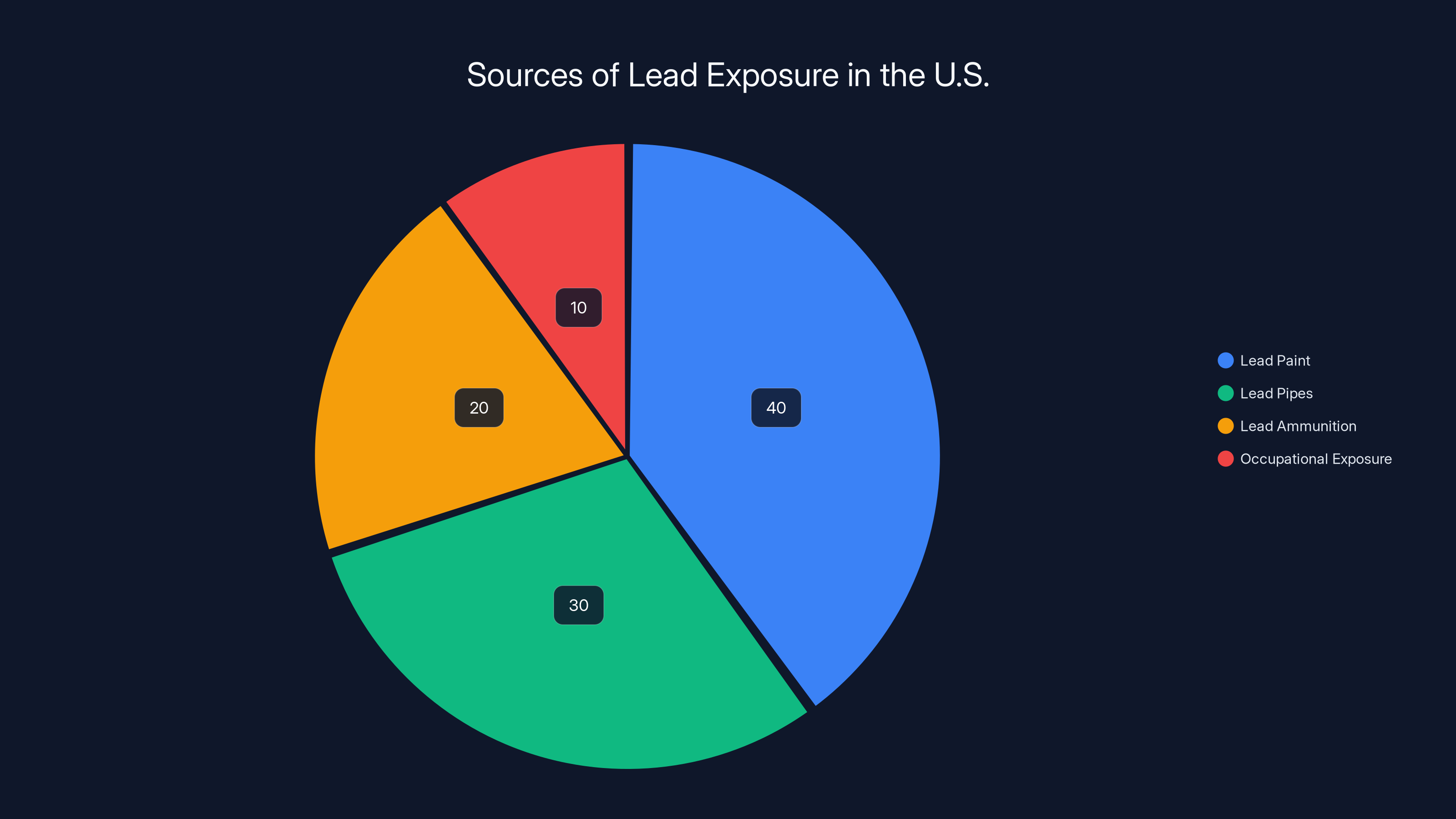

Lead paint and lead pipes are the largest sources of lead exposure in the U.S., accounting for 70% of the total. Estimated data.

Health Impact: What 100-Fold Reduction Actually Means

The abstract concept of a "100-fold reduction" needs to be translated into human health outcomes to be meaningful. What does it actually mean for people's lives that they're breathing 100 times less lead than their grandparents did? The effects are measurable and significant.

First, there's the direct neurotoxicological effect. Lead causes permanent damage to the developing brain. Exposure during childhood reduces IQ, impairs attention control, increases behavioral problems, and reduces educational attainment. These effects are permanent—you can't recover the lost cognitive development once the critical period has passed. Researchers studying the health effects of the lead phase-out have found that children born after leaded gasoline was phased out had measurably higher average IQ scores compared to children born during the peak-exposure era. The effect size was roughly 3–5 IQ points per standard deviation reduction in childhood blood lead levels. Given the population-wide drop in lead, the average IQ benefit at the population level is estimated at several points.

That might not sound like much until you think about it at scale. Several IQ points across millions of children translates to hundreds of thousands of additional people reaching higher educational attainment, earning higher incomes, and making greater economic contributions. It translates to lower crime rates (lead exposure is linked to violent crime), reduced unemployment, and broader improvements in social outcomes. One economic analysis estimated that the cognitive benefits of the lead phase-out alone generated economic value in the trillions of dollars across the lifespan of affected cohorts.

Beyond cognitive effects, there are cardiovascular benefits. Lead exposure causes hypertension and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. The mechanism appears to involve damage to the endothelial lining of blood vessels, increased inflammation, and various hormonal effects. People with chronic lead exposure have elevated blood pressure and higher rates of heart disease and stroke. Reducing population-wide lead exposure by 100-fold means corresponding reductions in hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and mortality from heart disease. The population-level impact is substantial—thousands of premature deaths prevented annually.

There are also benefits for reproductive health. Lead crosses the placenta and reaches the developing fetus. Prenatal lead exposure is associated with lower birth weights, premature delivery, and developmental problems. Women of childbearing age had their whole-body lead burden decline from the pre-EPA levels to post-phase-out levels, meaning that babies born after the phase-out had lower prenatal lead exposure. This has contributed to improvements in birth outcomes, reductions in childhood developmental problems, and better long-term health trajectories.

Kidney disease is another lead-related outcome that's been documented. Lead is nephrotoxic—it damages kidney function. Chronic lead exposure contributes to chronic kidney disease, which is epidemic in modern society but was even more common when lead exposure was higher. The phase-out of leaded gasoline has contributed to reductions in age-adjusted chronic kidney disease rates, though this benefit is often overlooked.

The sum of these effects—cognitive, cardiovascular, reproductive, and renal—represents a massive improvement in public health that's largely invisible because it's been so successful. You don't notice that rates of childhood neurodevelopmental disorders dropped after the lead phase-out because you don't have a point of comparison. You don't notice that there are fewer hypertension cases than there would have been because the counterfactual is hard to visualize. But the effects are real and measurable.

This is ultimately what the hair study is proving at a biological level. These health benefits aren't theoretical. They're written into the lives of millions of people who were exposed to lower lead than they would have been without EPA regulation. The measure is in hair. The meaning is in human health.

A Natural Experiment: Utah's Smelting Industry and the Researchers' Advantage

The University of Utah researchers chose their study population strategically. Utah's Midvale and Murray communities hosted major smelting operations—facilities that processed ore containing lead and emitted enormous quantities of lead into the surrounding air. These smelting operations ran for most of the 20th century, then closed down in the 1970s and 1980s when the EPA's regulations made them economically unviable or forced expensive emissions control retrofits.

This created a natural experiment with two independent sources of lead decline. First, there was the general decline from the EPA's leaded gasoline phase-out affecting the entire nation. Second, there was the localized dramatic decline from smelter closure affecting the Utah communities specifically. By studying hair samples from Utah residents, the researchers could see the cumulative effect of both factors. The lead levels dropped faster in Utah than they would have in many other parts of the country, because the residents of Midvale and Murray experienced both the national gasoline lead decline and the regional smelter closure.

This provided a more dramatic signal in the data. The hair samples from the most exposed residents—those living closest to the smelters—showed the most dramatic declines after the smelters closed. Researchers could identify and measure this effect. The people living furthest from the smelters showed a more gradual decline that matched the national trend from gasoline lead reduction. By analyzing the spatial gradient of lead exposure, the researchers could distinguish between the effects of different sources.

The study design had another advantage. The Utah residents who participated had been part of an earlier blood lead study, so the researchers had historical blood data from some participants. They could compare the hair-based measures of lead exposure to the blood-based measures and verify that the two methods were tracking the same phenomenon. This cross-validation strengthened the conclusions.

The use of hair samples that had been preserved for decades, some in family scrapbooks, was also valuable. These weren't just recently collected hair samples. These were actual physical evidence from the time period when the lead exposure occurred. A hair sample preserved from 1945 wasn't a reconstruction or estimate. It was a physical record of what was happening biologically at that moment. This directness of evidence—actual molecules from the past—makes the data particularly compelling.

Cerling noted that some of the most interesting samples came from older residents who had lived through the entire transition. Their personal hair samples spanned from the 1920s through the 2020s—a century of personal lead exposure history. Seeing how their own hair lead concentrations changed as policy changed was powerful confirmation of the regulatory impact.

The research team also was careful about potential confounding factors. They accounted for migration patterns—the fact that some people might have moved from high-exposure areas to low-exposure areas or vice versa. They considered changes in automotive technology beyond just the lead content. They looked at changes in occupational exposures (for example, workers in lead-related industries). By controlling for these factors, they isolated the impact of the regulatory changes themselves.

Estimated data shows potential increase in lead exposure levels if EPA deregulation occurs, based on historical trends.

The Regulatory Framework: How the EPA Actually Accomplished This

The EPA's lead phase-out is often presented as a simple ban, but the actual regulatory approach was more complex and reveals how environmental policy actually works in practice. The initial regulations weren't absolute bans. They were restrictions on the amount of lead allowed in gasoline, with the restrictions tightening year by year. This approach had several advantages.

First, it was based on a clear scientific standard. The EPA didn't just declare lead bad and order its removal. Researchers had established safe (or safer) thresholds of lead exposure for workers in lead-related industries, and the regulations were based on trying to bring ambient lead levels below those thresholds. The phase-out schedule was calculated to achieve specific ambient air quality standards for lead within a defined timeframe.

Second, the phased approach gave industry time to adapt. Removing all lead from gasoline overnight would have required refineries to completely reformulate their operations, auto manufacturers to redesign engines, and gas stations to install separate pumps and tank systems for unleaded fuel. A 15-20 year phase-out gave everyone time to make the necessary changes in an orderly fashion. This actually made the regulation more politically feasible and more likely to succeed.

Third, the phased approach included requirements for specific actions. Cars built after 1975 were required to have catalytic converters, which required unleaded fuel to function properly. This created market demand for unleaded gasoline, which provided incentive for refineries to produce it. The regulations didn't just restrict what was forbidden; they also created positive incentives for the solution.

Fourth, the EPA used monitoring and compliance mechanisms to enforce the regulations. Gas stations had to report their lead content. EPA inspectors tested gasoline samples. Companies found to be violating the regulations faced fines. This enforcement was crucial—without consequences for non-compliance, some companies would have continued using lead as long as they could get away with it.

The regulations also addressed the lead-based paint problem and lead-soldered cans separately, through different regulatory mechanisms. Lead paint was phased out. Lead solder in food cans was restricted. Lead pipes were discouraged through drinking water regulations. These weren't all accomplished at the same time or through the same regulation, but the cumulative effect was reducing lead from multiple sources.

Now, decades later, there's a political debate about whether these regulations were worth their cost. The petrochemical industry complained about the expense of reformulating gasoline. Car manufacturers complained about the cost of adding catalytic converters and retooling engines. Food manufacturers complained about the cost of finding alternative sealants for cans. But the complaint was overwhelmingly that the regulations were costly to implement. They didn't typically dispute that lead was harmful or that the health benefits were real.

What changed was a shift in political philosophy about how much regulation is acceptable and what costs are reasonable to impose on industry to achieve public health benefits. Some of the current skepticism about the lead regulations stems not from doubts about their effectiveness but from broader questions about the proper role of government and the appropriate balance between business interests and public health.

Cerling was explicit about why the research matters in this political context: "We should not forget the lessons of history. And the lesson is those regulations have been very important." He's not claiming that all regulations are good or that there are no costs to regulation. But he's saying that in this particular case, the regulations achieved their stated objective. Lead came down. Health improved. The evidence is in the hair samples.

Modern Concerns: Why This Research Matters Now

The decision to publish this research in 2026 wasn't accidental or driven purely by scientific curiosity. The research team explicitly noted that growing concerns about EPA deregulation motivated them to document the historical evidence of what successful environmental regulation looks like. This isn't ancient history. This is about policies that are currently under threat.

The Trump administration has signaled interest in deregulating many EPA functions. While lead specifically hasn't been targeted for outright deregulation, there have been hints at loosening enforcement of existing lead regulations, particularly around lead in drinking water. The 2024 Lead and Copper Rule, which requires water systems to replace old lead pipes, has been flagged as potentially subject to reconsideration. Lead paint regulations have been criticized as onerous.

Cerling and his colleagues appear to be making a historical argument: look what happened when we didn't regulate lead. Look what happened when we finally did regulate it. The evidence is unambiguous. The question facing policymakers is whether that evidence should influence current decisions.

There's also a current relevance to the lead story because lead exposure hasn't been completely solved. Many older homes still have lead paint. Many water systems still have lead pipes, particularly in older urban areas. Lead ammunition is still used widely in hunting and shooting sports, creating localized contamination around shooting ranges. Lead is still present in some occupational settings. The hair study shows that ambient lead from these sources is now measured in tenths of parts per million rather than tens or hundreds, but lead exposure isn't zero.

Environmentalists have used this research to argue that regulatory protections shouldn't be weakened. Public health advocates have used it to argue for accelerating remaining lead removal efforts. The hair study provides empirical grounding for these arguments.

But the political battle isn't really about the hair study's data, which are scientifically sound and hard to dispute. The disagreement is about different visions of regulation. Some people believe that the health benefits of eliminating lead exposure are worth the costs imposed on industry. Other people believe that those costs are unacceptable and that market forces or voluntary industry action could have achieved similar results. The hair study doesn't resolve that philosophical disagreement. But it does provide clear evidence of what the health benefits actually were.

The Broader Lesson: What This Case Study Reveals About Environmental Regulation

The leaded gasoline story, anchored by the hair study evidence, teaches several broad lessons about how environmental regulation works in practice. These lessons extend beyond lead and apply to thinking about other environmental and health regulations.

First, the story demonstrates that scientific evidence doesn't automatically translate into policy action. Lead's neurotoxicity was well-established in scientific literature by the 1920s. Clair Patterson published his evidence of widespread lead contamination in the 1960s. The harmful effects were documented. Yet it took until 1970 for serious EPA action, and the phase-out took until the 1980s-1990s to complete. The gap between scientific certainty and policy action was enormous. This wasn't because the science was unclear. It was because economic interests opposed the regulation.

Second, the story shows that incremental regulation can work. The EPA didn't try to eliminate all lead immediately. They set standards, created timelines, and adjusted as needed. This phased approach was pragmatically successful in ways that a more aggressive approach might not have been. It's a lesson in regulatory design—sometimes the most effective policy is one that industries can grudgingly adapt to rather than fight outright.

Third, the story illustrates the value of monitoring and measurement. The EPA's regulatory approach was based on specific ambient air quality standards for lead. EPA scientists measured lead in air, soil, and human blood to track progress. The researchers set declining targets for lead content in gasoline with the goal of achieving specific health outcomes. This measurement-based approach allowed the regulators to verify that the policy was working and adjust if needed.

Fourth, the story demonstrates that some environmental and health problems have technological solutions. Lead could be removed from gasoline. Catalytic converters could be added to cars. Unleaded fuel formulations could be developed. The problem wasn't that these things were impossible—it was that they weren't profitable without regulatory pressure. Once the regulations mandated the changes, the technology adapted and it became economically viable. This is relevant for other environmental problems where the technology exists but market forces alone don't drive adoption.

Fifth, the story shows the difference between individual health advice and population health policy. A person could always choose to avoid lead exposure if they had the knowledge and resources. They could avoid living near highways, avoid old housing stock, be careful about water sources. But individual action can't solve a widespread environmental problem. When lead is ubiquitous in gasoline, air, dust, and food, individual avoidance becomes impractical. Policy-level solutions are necessary for population-level improvement.

Finally, the story illustrates the time lag between policy change and measurable health improvement. The lead regulations began in 1970, but it took decades to see the full health benefits. This is important for evaluating environmental regulations. You can't judge a regulation's success based on immediate results. You need to look decades out to see the full impact. This makes environmental policy evaluation inherently difficult because the benefits come so much later than the regulatory action.

Measurement Methods: How Hair Analysis Really Works

For readers curious about the technical details of how the researchers actually measured lead in hair, understanding the methodology helps appreciate the robustness of the findings. The technique used was inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), a state-of-the-art analytical method that can measure trace elements at extreme sensitivity.

Here's roughly how the process works. A hair sample is carefully prepared. It's cleaned to remove surface contaminants that might skew the measurement. Then it's either dissolved in acid or ablated with a laser to break it down into its constituent atoms. Those atoms are ionized (given an electric charge) and sent into a mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometer separates the atoms based on their mass-to-charge ratio. Lead atoms are identified by their characteristic mass, and their concentration is measured.

The sensitivity of modern ICP-MS instruments is remarkable. They can detect lead at concentrations of parts per billion (ppb) or better in many cases. So a measurement of lead in hair at 50 ppm (50 million ppb) is using only a tiny fraction of the instrument's detection capability. There's plenty of safety margin and sensitivity to catch small differences between samples.

One challenge with hair analysis is that lead can settle on the surface of hair from environmental contact, separate from the lead that was actually incorporated as the hair grew. Diego Fernandez, one of the research team, noted that the surface of hair is special—it concentrates certain elements. Lead is one of them. This means that hair that has been exposed to a dusty environment (or even to dust in a museum while being preserved in a collection) can pick up lead on its surface.

But this is actually a feature, not a bug, for the researchers' purpose. If you want to know someone's overall environmental lead exposure—not just the lead in their bloodstream when their hair was growing, but all the lead they were encountering in their environment—then the surface lead concentration gives you that information. Fernandez explained: "It's probably in the surface mostly, but it could be also coming from the blood if that hair was synthesized when there was high lead in the blood."

In other words, the lead in hair comes from two sources. Some comes from the bloodstream as the hair grows (reflecting the person's internal lead burden). Some comes from environmental contact (reflecting the lead in the air, dust, and surfaces they're exposed to). The total lead measured in the hair integrates both sources, giving a complete picture of lead exposure.

This is actually ideal for the researchers' purpose because they want to document environmental lead exposure, not just blood lead levels. The hair measurement captures both. An older hair sample shows high total lead because the person grew that hair while living in a high-lead environment and then preserved the hair exposed to decades of environmental contact. A recent hair sample shows low total lead because the person grew it in a low-lead environment and it's been exposed to a low-lead environment since.

The research team also noted that while they couldn't pinpoint exactly where in the hair the lead was (surface versus interior), they could use the distribution of measurements across many samples to infer patterns. Hair samples from pre-EPA times consistently showed higher lead concentrations than post-EPA samples. This consistency across many independent samples rules out the possibility that the differences were due to random variation or contamination artifacts. The pattern is robust.

Lessons for Contemporary Environmental Policy Debates

The leaded gasoline story provides historical perspective on several contemporary environmental and regulatory debates. It's not a perfect analogy—every environmental problem is different—but the pattern of scientific concern, industry resistance, policy action, and eventual vindication appears in other contexts too.

Consider mercury. Like lead, mercury is a neurotoxin. It enters the environment from multiple sources including power plant emissions, mining, and industrial processes. It accumulates in fish, which is then consumed by humans. Mercury exposure is linked to neurological damage, particularly in developing fetuses. For decades, the regulatory status of mercury was contentious, with industry claiming that natural mercury sources dominated the problem. Eventually, the EPA implemented regulations limiting mercury emissions. Current measurements show declining mercury in hair and blood samples, particularly in children, reflecting the declining environmental exposure.

Or consider persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like DDT. For decades, DDT was used as a pesticide. Scientists documented that it persisted in the environment and accumulated in animal tissues. Evidence of health harm accumulated. The EPA banned DDT in the United States in 1972. Subsequent measurements show declining DDT in human tissues, particularly in younger generations that never had direct exposure. The story parallels the lead case: evidence of harm, regulatory action, verification of benefit through biological measurement.

But there are also instructive differences. The lead story involved a chemical that was ubiquitous and contributed to environmental contamination through a clear mechanism—automotive exhaust. Lead removal was straightforward once alternatives were developed. Some environmental problems are more complex. Climate change involves greenhouse gases from diverse sources, and the solutions involve systemic changes to energy, transportation, and agriculture. No single substitution works.

Another difference is the immediacy of health effects. Lead's harm to children's neurological development is real but occurs over time. The effects accumulate and manifest as group-level health changes rather than acute poisonings. This makes it easier for people to dismiss or delay action on lead (as happened for decades). Some health hazards produce acute effects that demand immediate attention.

The leaded gasoline case also involved a situation where the technology for solving the problem already existed. Unleaded gasoline was chemically feasible; it just required different additives than tetraethyl lead. Some environmental problems have no obvious technological solution yet, requiring fundamental innovation.

But the most broadly applicable lesson from the leaded gasoline story is that the relationship between evidence and policy action is neither automatic nor simple. Clear scientific evidence of harm didn't immediately produce regulation. Powerful economic interests resisted regulation. The political process took decades to move from scientific consensus to policy action to regulatory implementation. And even today, decades after the regulations succeeded, there are political movements to weaken or eliminate them.

This suggests that for other environmental problems where evidence is accumulating (ocean plastics, PFOA contamination, microplastics in drinking water, and others), the path from evidence to action may be similarly slow and contentious. The leaded gasoline story provides perspective: yes, the regulatory process is slow and influenced by economic interests, but eventually evidence wins, policy changes, and health improves. The question isn't whether the evidence will eventually force action, but how much harm occurs while waiting for that action.

Why This Research Matters Beyond Lead

The leaded gasoline research matters beyond its historical importance because it provides a framework for understanding how to evaluate environmental regulations in general. The methodology—using biological measurement to document population-level health changes tied to specific policy interventions—can be applied to other environmental regulations to measure their actual impact.

Many environmental regulations are implemented with good intentions and plausible mechanisms, but the actual health outcomes are rarely measured directly. Regulations are evaluated based on compliance data (did companies meet the standards?), environmental data (did the contaminant levels in air or water decline?), or economic impact (what did the regulation cost?). But often, nobody bothers to measure the actual health outcomes in human populations—whether people are actually healthier because of the regulation.

The hair study does this for lead. It uses a biological marker that persists over decades to document that human exposure to lead has declined. It ties that decline to specific policy actions. It provides evidence that the regulation achieved its intended health outcome. This is a model that could be applied to other regulations.

For example, has anyone analyzed hair or blood samples to document whether declining mercury regulations (which limit power plant emissions) have actually reduced human mercury exposure? Has anyone systematically measured whether regulations limiting agricultural pesticides have reduced persistent pesticide residues in human tissues? Has anyone documented human exposure to persistent organic pollutants over time and correlated it with regulatory restrictions on those chemicals?

There are some examples in the literature—studies have documented declining blood lead levels in children after lead paint regulations, declining blood PCB levels after PCB bans. But this type of biological documentation of regulatory success is surprisingly rare. Most environmental regulations are implemented, compliance is monitored, and that's considered success. Whether humans are actually healthier is often assumed rather than measured.

The leaded gasoline research provides a template: identify the source of contamination, measure human exposure through biological means (hair, blood, tissue), track changes over time, correlate with policy changes, and document health outcomes. If more environmental regulations were subjected to this type of evaluation, we'd have much better data about which regulations work and which ones are less effective than intended.

Looking Forward: The Ongoing Challenge of Lead

While the leaded gasoline ban was spectacularly successful, lead hasn't been completely eliminated from the American environment. Current challenges involve residual lead from earlier periods and new sources that are harder to address than atmospheric lead from gasoline.

Lead paint remains a problem in older housing stock. Homes built before 1978 often have lead paint, which is now banned but creates ongoing risk for people living in or renovating these homes. Lead dust can be created when paint deteriorates, or during renovation work. Children living in homes with lead paint have higher blood lead levels than other children. Lead paint abatement programs have been implemented, but they move slowly because of cost and the sheer number of affected homes.

Lead pipes and lead solder in plumbing represent another ongoing source of lead in drinking water. Many water systems, particularly older ones, have lead pipes delivering water from the main to individual homes. Lead can leach from these pipes into water, particularly when water is acidic or has low mineral content. The 2024 Lead and Copper Rule requires water systems to eventually replace lead service lines, but the timelines are measured in decades, and the cost is enormous. A typical lead service line replacement costs

Lead ammunition is another source. When firearms are discharged, the lead bullet fragments on impact or leaves residual lead at the firing site. Shooting ranges where lead ammunition is used can accumulate lead in soil that then becomes accessible to wildlife and potentially to humans. Some states and municipalities have begun restricting or banning lead ammunition, but this is politically contentious and progress is slow.

Occupational lead exposure remains a concern for workers in industries like battery manufacturing, metal recycling, smelting, and construction (where lead paint removal occurs). These workers can have elevated blood lead levels despite regulations limiting exposure, largely because the regulations aren't always enforced rigorously.

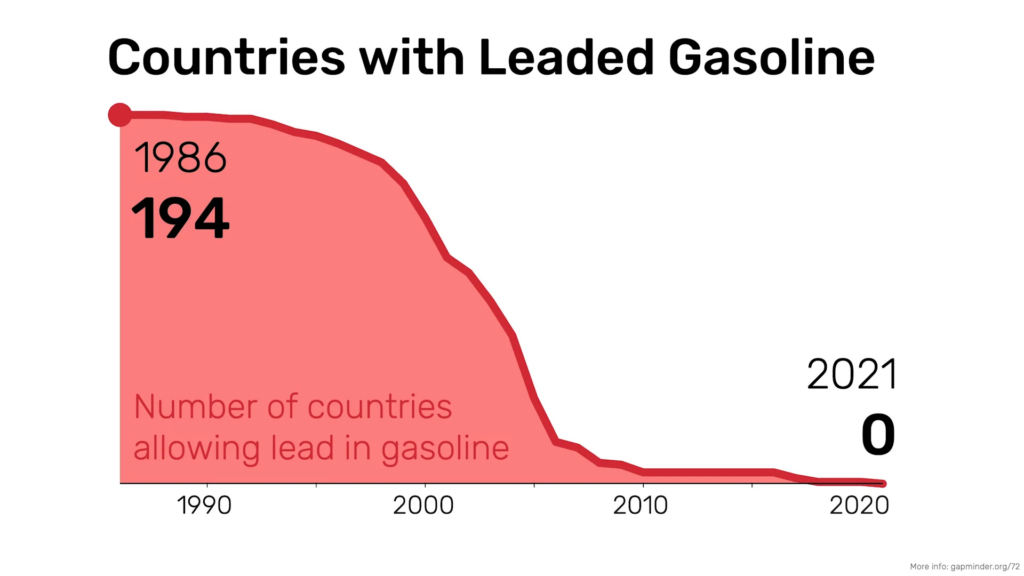

Developing countries have been slower to phase out leaded gasoline. While most of the world has moved away from leaded fuel, some countries still use it, and even countries that have phased it out may have imported leaded fuel during the transition period. Global lead exposure remains much higher than in the United States.

The hair study isn't claiming that the lead problem is completely solved. Rather, it's documenting that the single largest source of lead exposure to the general population—leaded gasoline—was successfully eliminated through regulation. Residual lead problems remain, but they're far smaller than the gasoline-driven problem of the pre-1970s era. The research provides a baseline for understanding how far we've come and how much further we might need to go.

The Big Picture: Policy Works, But It Takes Time

The leaded gasoline story, documented through hair samples spanning a century, tells a fundamentally optimistic narrative about policy-driven environmental health improvement. It shows that a serious health threat—widespread lead contamination affecting millions of people—was identified through scientific research, addressed through regulatory action, and successfully reduced to the point where it's no longer a major public health threat.

But the story also contains hard truths. It took decades from the initial scientific concern to regulatory action. Economic interests resisted throughout. The phase-out took 20 years to complete. Policy action was far slower than the science warranted. And even now, decades after the regulations succeeded, there are movements to weaken them.

Those are the lessons the research team was trying to document. Regulations sometimes seem onerous to industries and slow down economic activity. But when those regulations address serious health threats, the long-term benefits vastly outweigh the costs. The hair samples provide the evidence. Lead in human bodies has declined 100-fold. The health benefits—improved cognitive development, reduced cardiovascular disease, improved reproductive outcomes, reduced kidney disease—are real and measurable.

The relevance to contemporary policy debates is clear. Environmental and health regulations face ongoing political challenges. The response to those challenges should be informed by historical evidence about whether regulations work. The leaded gasoline case provides that evidence clearly. Regulation worked. Health improved. Millions of people are healthier because of it.

For a future where climate change, plastic pollution, toxic chemical exposure, and other environmental health threats need to be addressed, the leaded gasoline story offers both inspiration and caution. Inspiration that comprehensive regulatory action can work and produce measurable health benefits. Caution that the regulatory process is slow, contested, and constantly under threat. The difference between success and failure often comes down to whether evidence, stubbornly accumulated over time, eventually influences policy in the direction of protecting public health.

The hair samples are still there, carefully preserved and measured. They tell a story about what happened in the 20th century and what became possible when policy caught up to science. They're a reminder that biology doesn't lie, even when politics tries to tell a different story.

FAQ

What is lead and why is it dangerous?

Lead is a heavy metal that's highly toxic to human health, particularly affecting the brain and nervous system. It has no known biological purpose in the human body and has no safe threshold of exposure. Even at low levels, lead exposure can reduce IQ, impair learning and behavioral control, increase blood pressure, damage kidneys, and affect reproductive health. Lead was widely used in gasoline, paint, solder, and many industrial applications before the dangers became widely recognized.

How do hair samples reveal lead exposure history?

Hair acts as a biological record of environmental exposure. As hair grows, it incorporates elements from your bloodstream and from contact with the surrounding environment. Lead accumulates in hair and doesn't degrade over time, making it possible to measure lead concentrations in hair that was grown decades ago. By analyzing hair from different time periods, researchers can document how environmental lead exposure has changed. The University of Utah researchers used this method to track lead levels across a century of samples.

What did the EPA do about leaded gasoline?

The EPA implemented a phased phase-out of lead in gasoline beginning in 1970, with increasingly strict regulations through the 1980s. Lead content was gradually reduced year by year, giving refineries and automakers time to adapt. Catalytic converters (which required unleaded fuel) were mandated on new cars, providing market incentive for unleaded fuel production. The regulations were fully implemented by the mid-1990s, eliminating lead from standard automotive fuel entirely. Similar regulations eliminated lead from paint, canned food solder, and drinking water systems.

How much did lead concentrations decline after the ban?

According to the University of Utah research, hair samples show a 100-fold decline in lead concentrations from the 1960s peak levels (50-100 ppm) to current levels (less than 1 ppm) by 2024. The steepest declines occurred during the 1970s and 1980s, when the EPA was phasing out leaded gasoline. By 1980, concentrations had dropped roughly 50% from peak levels. By 1990, they had dropped 90% compared to the 1960s baseline.

What are the health benefits of reducing lead exposure?

Reducing lead exposure benefits nearly every system in the human body. The most significant benefits for children are cognitive—studies show that children born after lead was phased out had measurably higher average IQ scores than children born during the peak-exposure era, with benefits estimated at several IQ points at the population level. For adults, lead reduction improves cardiovascular health by reducing hypertension and heart disease risk. Reproductive health improves with lower prenatal lead exposure. Kidney function improves, reducing chronic kidney disease risk. The economic value of these health benefits over the lifetime of affected cohorts is estimated in the trillions of dollars.

Why is this research being published now in 2026?

The University of Utah research team published their findings at a moment when EPA regulations are under political pressure and there are discussions about deregulating various environmental protections. The researchers explicitly stated they wanted to document historical evidence that environmental regulations work and produce measurable health benefits. Their goal was to provide evidence to inform contemporary policy debates about whether environmental regulations should be maintained, weakened, or eliminated.

How does lead enter the human body and where does it accumulate?

Lead enters the body primarily through inhalation of lead particles and vapors in air, particularly from automotive exhaust in the leaded gasoline era. Lead can also enter through contaminated food and water. Once in the bloodstream, lead is distributed throughout the body. It accumulates in bones where it can be stored for decades, gradually releasing into the bloodstream. Lead also crosses into soft tissues including the brain, where it causes neurological damage. Pregnant women can transfer lead across the placenta to the developing fetus, affecting prenatal development.

What was Thomas Midgley Jr.'s role in leaded gasoline?

Thomas Midgley Jr. was a General Motors engineer who discovered that tetraethyl lead (TEL) was an excellent anti-knock additive for gasoline. Lead improved engine performance and combustion efficiency dramatically. Midgley led the development of leaded gasoline, which was commercialized beginning in 1923. He publicly defended its safety despite having personally experienced lead poisoning from his work. His legacy is controversial—beyond leaded gasoline, he also invented chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which created the ozone hole. He suffered a tragic end, dying in 1944 from strangulation by the elaborate pulley system he had devised to help him cope with severe polio.

What role did Clair Patterson play in eliminating leaded gasoline?

Clair Patterson was a Caltech geochemist who became an environmental crusader after discovering that lead contamination was nearly ubiquitous in modern environments. While calculating Earth's age through lead-dating of meteorites, he discovered that his laboratory was contaminated with atmospheric lead, leading him to investigate the extent of modern lead pollution. His research documented that lead levels were roughly 1,000 times higher than pre-industrial levels and identified leaded gasoline as a major source. Patterson published extensively on lead's health effects and advocated for its elimination, despite professional opposition from industry-funded scientists and industry lobbies. His accumulated evidence ultimately provided the scientific foundation for EPA regulations.

Are there still sources of lead exposure today?

While atmospheric lead from gasoline has been essentially eliminated, residual lead sources remain. Lead paint in older homes (pre-1978) is still present and can be disturbed during renovation. Lead pipes and solder in plumbing systems still deliver water in many older communities, allowing lead to leach into drinking water. Lead ammunition from shooting ranges accumulates in soil. Some imported products and certain occupational settings still involve lead exposure. However, current environmental lead levels are many times lower than pre-regulation levels, and the public health threat has been dramatically reduced compared to the gasoline-era problem.

How does the leaded gasoline story inform thinking about other environmental regulations?

The leaded gasoline case provides historical perspective on environmental policy. It shows that serious health threats can be identified through scientific research, addressed through regulatory action, and successfully reduced. However, it also illustrates that policy action is slower than the science warrants, that economic interests resist regulation, and that even successful regulations face ongoing political challenges. The story suggests that for other environmental threats (mercury, persistent organic pollutants, climate change, plastic pollution), similar patterns may emerge: evidence accumulates, regulatory action is delayed and contested, but eventually policy responds if the evidence is strong enough. The leaded gasoline story proves that comprehensive environmental regulation can work and produce measurable health benefits.

Conclusion: Biology Doesn't Lie

A strand of hair preserved in a scrapbook from 1920 still contains the chemical record of what that person breathed. It's a time capsule of environmental exposure, a biological document of a moment in the past. When scientists analyze thousands of these hair samples across a century, they're reading the history of environmental contamination and human health in the most literal way possible.

The University of Utah researchers found something remarkable: a 100-fold decline in lead over a century, with the dramatic drop occurring precisely when the EPA phased out leaded gasoline. This isn't a correlation based on statistical analysis or assumption. It's written into biology itself. The people of Utah have less lead in their hair now than their grandparents did because the environment has less lead in it. The change is measurable, documented, and undeniable.

This research matters because it provides evidence at a moment when evidence is being questioned. The regulatory framework that eliminated lead from gasoline, paint, and soldered cans is under political pressure. Some people argue these regulations were unnecessary, or that the health benefits don't justify the costs, or that market forces would have solved the problem anyway. The hair study answers these arguments with biology. The regulations worked. Health improved. Millions of people are healthier because of it.

But the research also carries a cautionary message. The path from scientific evidence of harm to regulatory action to health improvement took decades. Economic interests resisted throughout. Policy action was slower than the severity of the problem warranted. And even now, with the benefits proven and documented, the regulations are under threat. The lesson for other environmental and health challenges is clear: the regulatory process is slow, contested, and constantly under pressure. Success requires sustained scientific effort, political action, and willingness to impose costs on industries that profit from contamination.

The future will be determined by whether we learn these lessons. Will we wait decades to act on climate change as we did on lead? Will we phase out toxic chemicals gradually and reluctantly, or do so expeditiously? Will we evaluate environmental regulations based on actual health outcomes, as the hair study does for lead, or will we continue to implement them blindly without measuring whether they work?

The hair samples tell a story about the 20th century and what became possible when science was taken seriously. They're an archive of human biology across a transformative moment in environmental policy. They prove, in the most direct way possible, that regulation works. The question now is whether we'll apply that lesson to the environmental challenges ahead.

Editor's Note: This article was written to provide comprehensive context on the University of Utah hair analysis research documenting the success of EPA leaded gasoline regulations. The research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and represents one of the most direct biological documentations of environmental regulatory success. The findings have significant implications for ongoing policy debates about environmental protection and regulation.

Key Takeaways

- Hair samples spanning 100 years document a 100-fold decline in lead after EPA banned leaded gasoline in the 1970s

- Environmental regulations successfully reduced population-wide lead exposure from roughly 2 pounds annually per person to negligible modern levels

- Clair Patterson's scientific research on atmospheric lead contamination provided the evidence that eventually forced regulatory action

- Lead reduction improved cognitive development, reduced cardiovascular disease, and improved reproductive health across millions of people

- The regulatory process was slow (20+ years from clear evidence to full implementation) but ultimately proved that policy works when backed by science

- Hair acts as a biological time capsule, accumulating and preserving evidence of environmental exposure for decades

![Hair Sample Study Proves Leaded Gas Ban Worked [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/hair-sample-study-proves-leaded-gas-ban-worked-2025/image-1-1770065036761.jpg)