The Robot Butler We Thought We'd Have by Now

For decades, we've been sold a dream. The Jetsons promised us Rosey the Robot—a single, capable machine that would handle everything from vacuuming to cooking to childcare. Science fiction kept this fantasy alive. We watched WALL-E, read about household humanoids in books, and assumed that by 2026, some brilliant engineer would crack the code and deliver the all-purpose home robot.

Then CES 2026 happened.

And the message was clear: that dream isn't dead, exactly, but it's been quietly shelved. Instead, what's actually arriving in homes right now—and what will dominate the next five years—is something much more boring and pragmatic. It's not one robot. It's an army of them. Each one obsessively specialized. Each one doing exactly one job, and doing it better than any human could.

This isn't a failure of innovation. It's actually the opposite. The robotics industry has learned a hard lesson from watching industrial automation play out over the last two decades. When you stop trying to build the perfect all-in-one machine and start building robots that excel at single tasks, something magical happens. They work. They're cheaper. They're easier to maintain. And they actually sell.

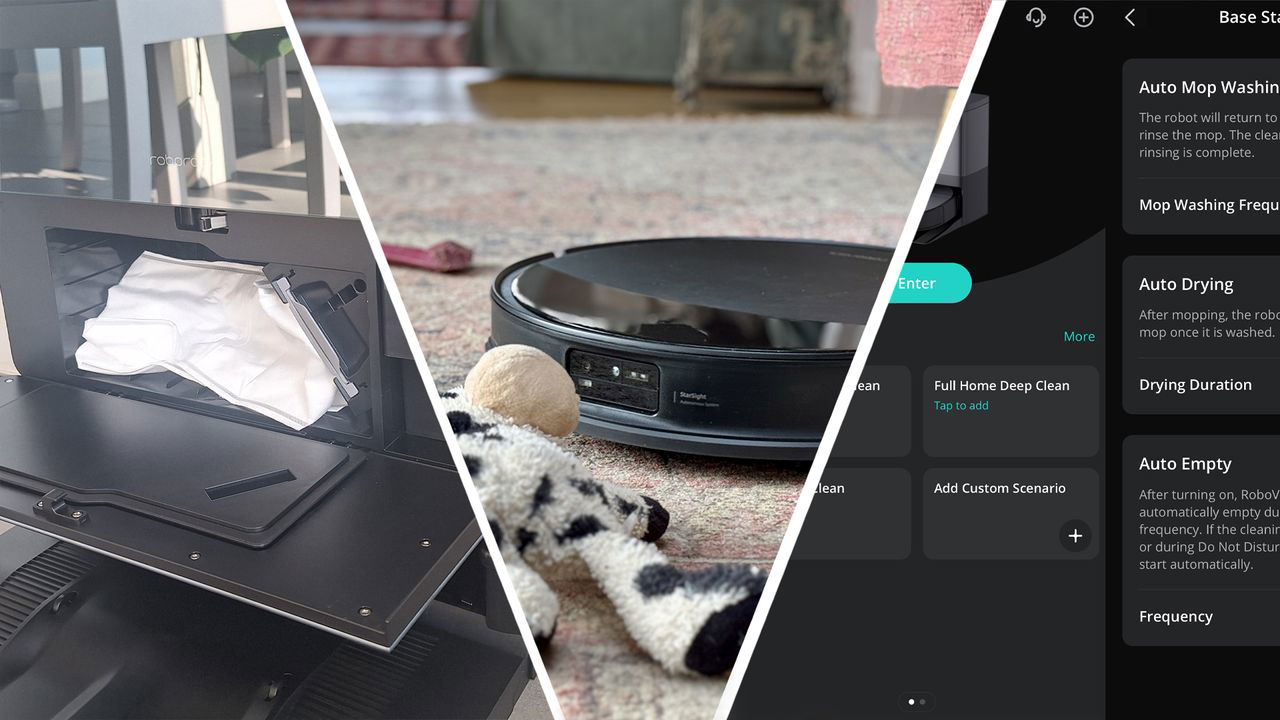

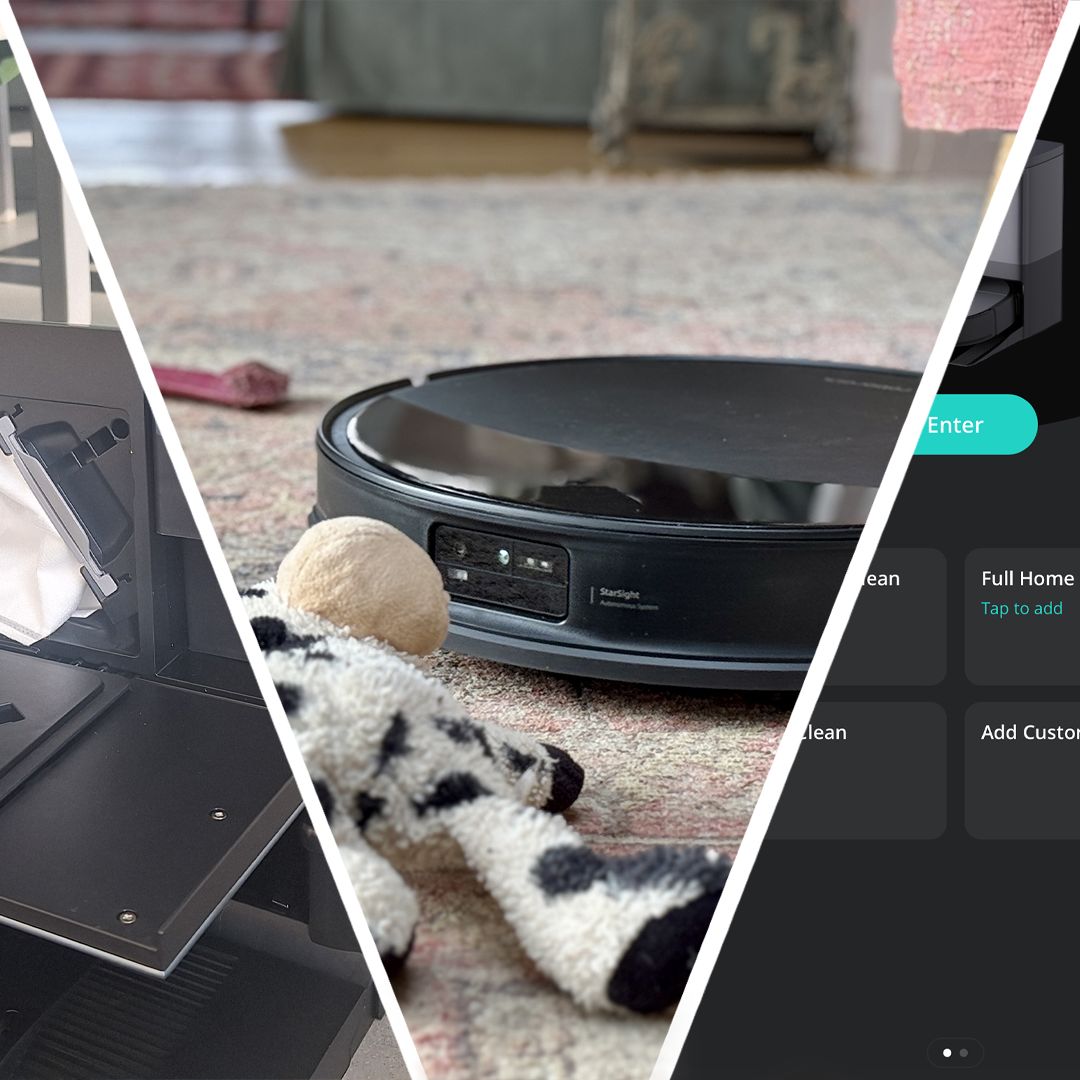

Walk through CES 2026's robot section, and you'll see evidence everywhere. Roborock's Saros Rover doesn't do your laundry or cook dinner. It vacuums. But it does it so well—jumping over obstacles, climbing stairs, navigating terrain that would destroy a traditional wheeled vacuum—that it's moving from concept to real people's homes. Anker's new Eufy robovac doesn't just clean floors. It also diffuses fragrance. Dreame's Cyber X concept vacuum moves on tank treads like some kind of domestic robot assassin, built purely to handle vacuuming in ways previous generations couldn't.

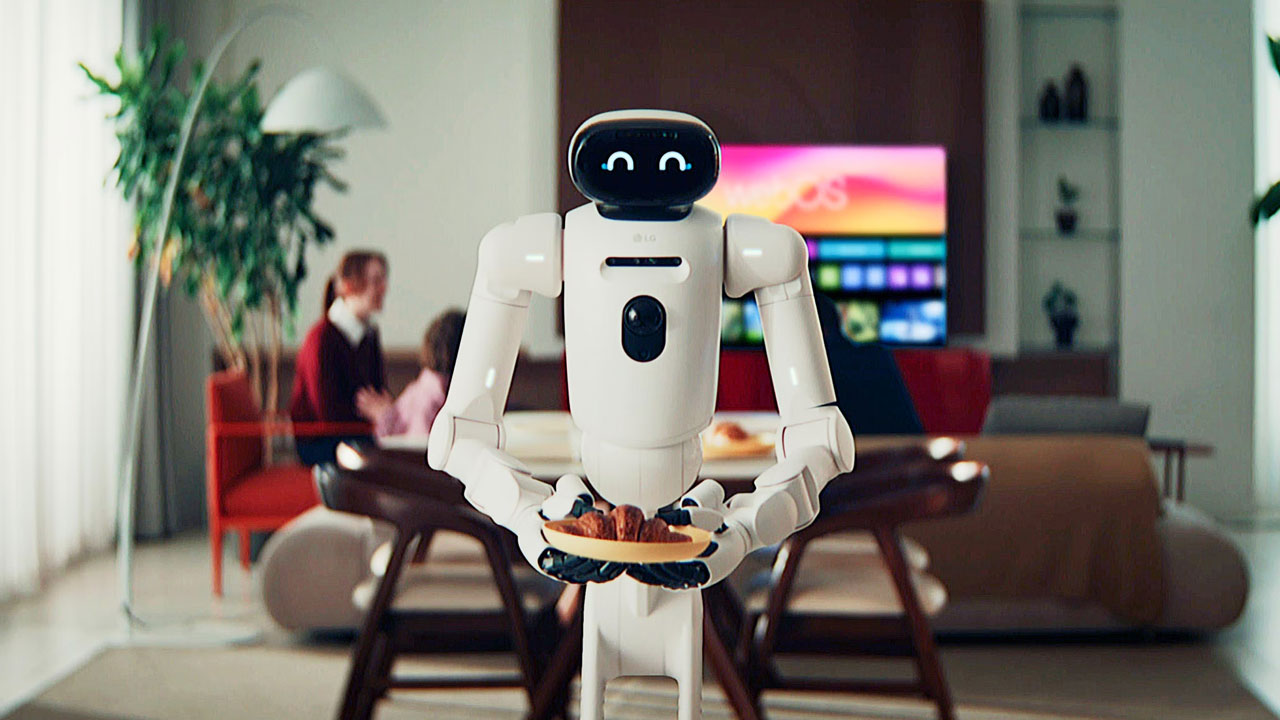

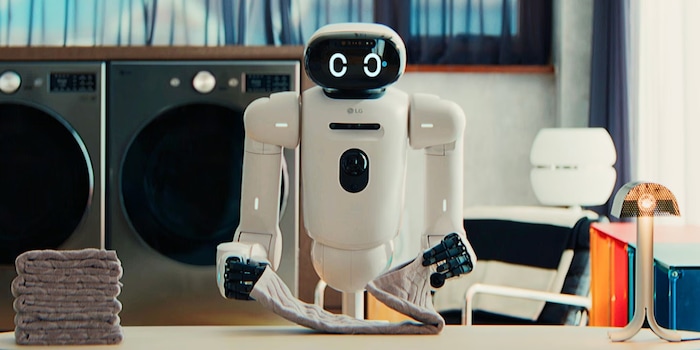

Meanwhile, robotic mowers are proliferating. Pool cleaners are getting smarter. Robot toys are becoming genuine home companions. And LG keeps pushing its humanoid CLOi D forward, slowly loading laundry one movement at a time—because apparently, someone still believes in that dream.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: the future of home robots isn't coming from a single product. It's coming from an ecosystem. And that ecosystem is built on a principle borrowed directly from industrial robotics: when you need multiple tasks completed, you're better off with multiple specialized tools than one mediocre all-arounder.

TL; DR

- The humanoid home robot is still years away: Despite hype, no consumer-ready all-in-one home robot exists with a firm release date

- Specialized bots are winning: Single-purpose robots like advanced vacuums, mowers, and pool cleaners are solving real problems right now

- Industrial robotics led the way: Warehouses proved specialized robots outperform flexible ones in controlled environments

- The ecosystem approach is taking over: Instead of one robot butler, homes will soon contain 3-5 specialized robots

- This is actually progress: Task-specific design means better performance, lower costs, and faster innovation cycles

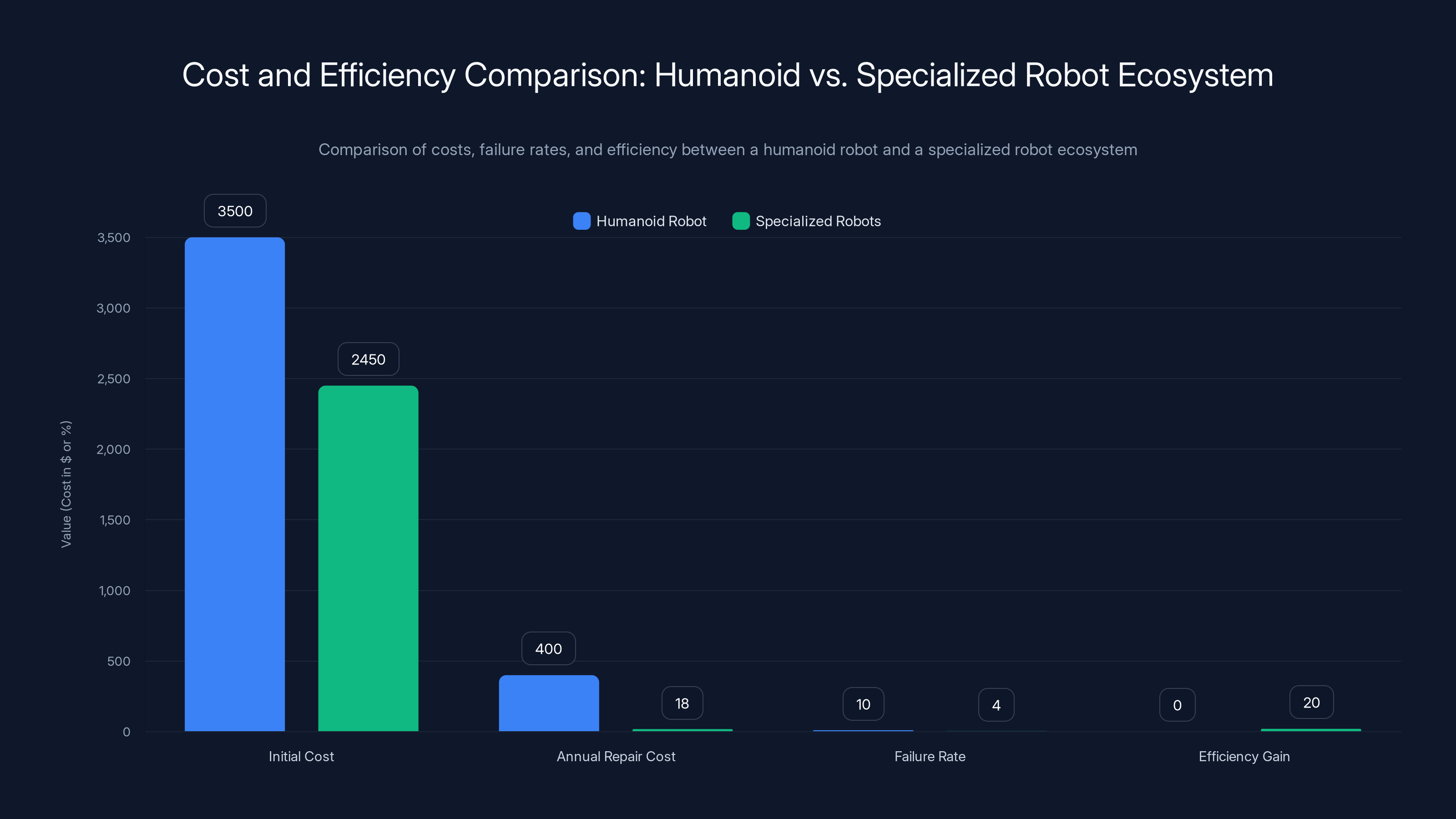

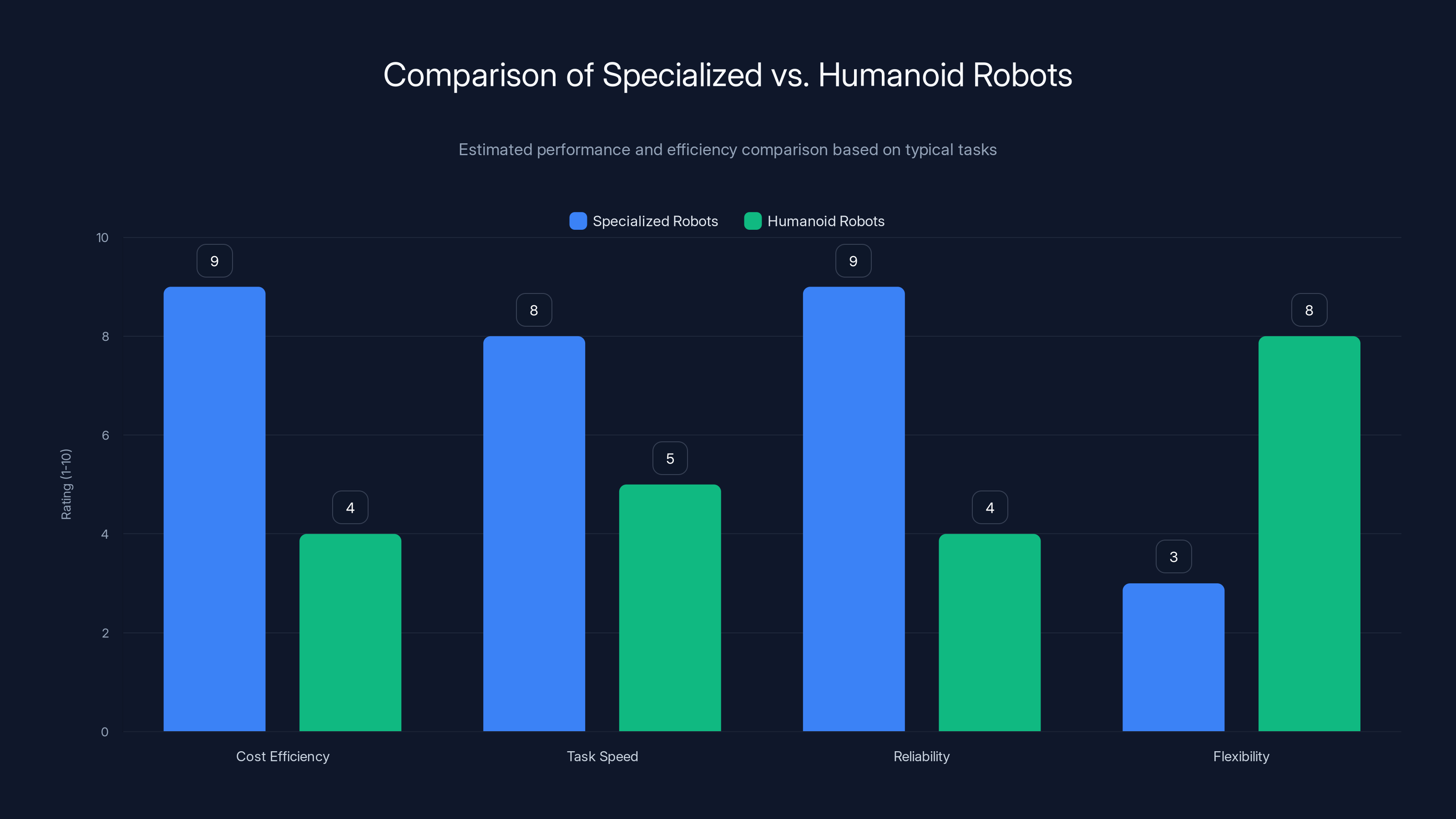

The specialized robot ecosystem is more cost-effective and efficient, with lower failure rates and higher task efficiency compared to a humanoid robot. Estimated data.

Why the All-In-One Home Robot Failed (Before It Started)

Let's be honest about what happened. The humanoid robot dream wasn't abandoned because roboticists gave up. It was abandoned because the laws of physics, economics, and user behavior all conspired against it.

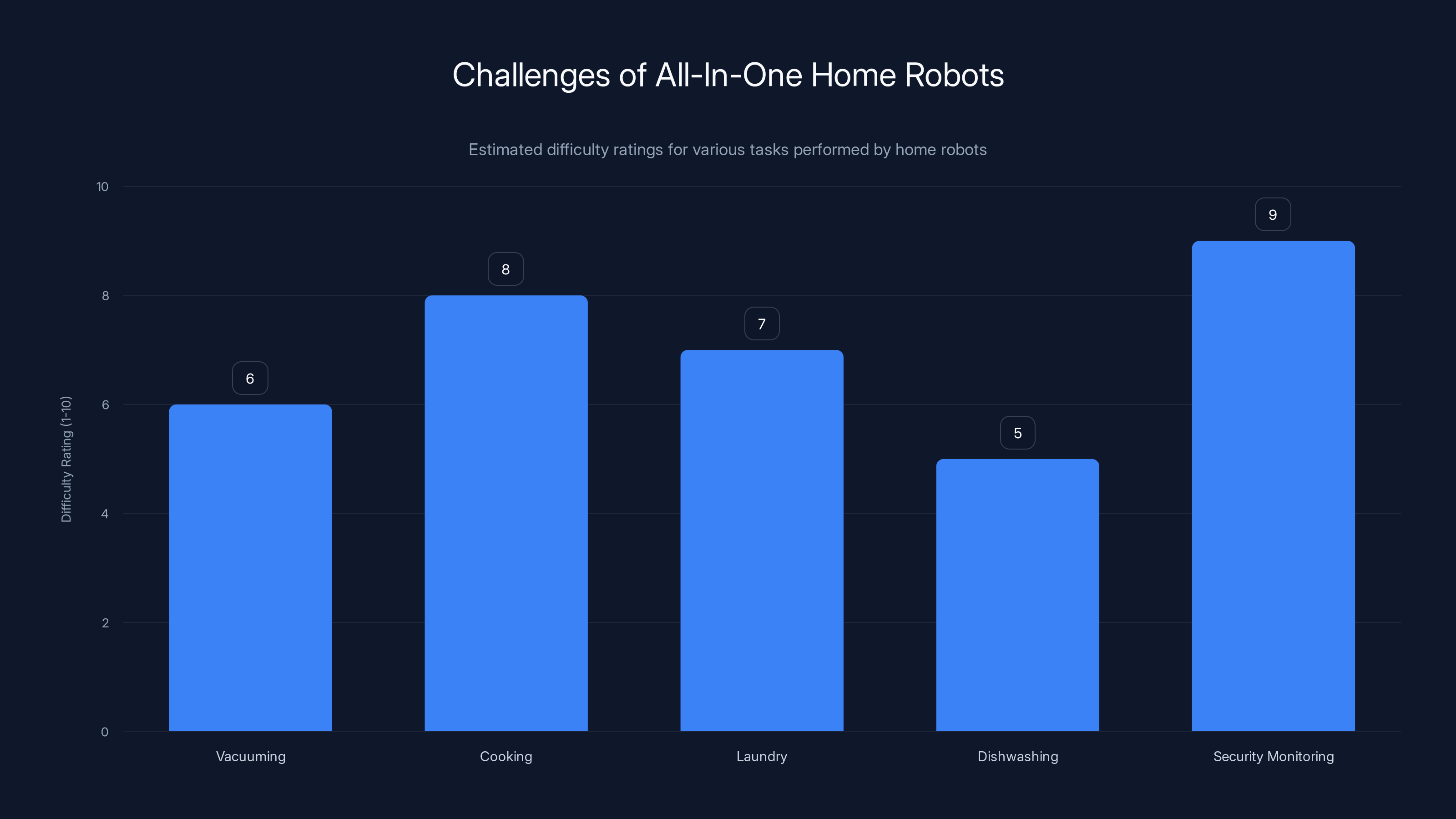

Consider what an all-purpose home robot would actually need to do. It would need to vacuum, mop, do laundry, load a dishwasher, cook meals, take out trash, clean bathrooms, water plants, play with pets, and probably monitor security. Each of those tasks requires different hardware. Vacuum hands need to be different from cooking hands. The motors required for laundry are fundamentally different from the motors needed for vacuuming. The software stack for navigation is completely separate from the software needed for object recognition in a kitchen.

Then there's the fundamental constraint: a humanoid form factor is optimized for nothing specific. Humans evolved as generalists because we needed to survive in unpredictable environments where specialization would kill us. But in your home—a controlled space you design and maintain—generalization is a liability.

This is exactly what James Matthews from Ocado discovered when warehouses started deploying robots. Ocado operates sophisticated fulfillment centers for online groceries across the United States, handling orders for retailers like Kroger. Inside those warehouses, they don't use humanoid robots that move from task to task. Instead, they use specialized robots designed specifically for moving crates, or packing bags, or loading trucks. Each robot is exquisitely optimized for a single function. And because of that optimization, they're faster, cheaper, and more reliable than any humanoid alternative could be.

"When you have a controlled environment that you can change and manipulate, you're generally better off with a specific tool for a specific job," Matthews explained. The adaptability that makes humanoids theoretically appealing becomes a weakness when you're trying to maximize efficiency. A humanoid robot has to compromise on every dimension to maintain that generalist form factor. The legs that allow it to walk up stairs make it slower at rolling. The hands that can grasp objects are weaker than specialized manipulation arms. The sensors that allow it to recognize kitchen objects are the same sensors used for navigation, so it's constantly computing multiple perception tasks on the same hardware.

Contrastingly, a robot designed purely for vacuuming can optimize the entire system for that single task. Wheels can be perfectly tuned for the floor surfaces in your home. Suction power can be maximized without compromising on weight or battery life. Software can focus entirely on floor-mapping and obstacle detection. The robot doesn't need to "think" about what a dish is or how to hold a broom. It just needs to clean.

As you look at the economics: a specialized robot costs less to manufacture, less to support, and less to repair. If your vacuum breaks, you replace the vacuum. With a humanoid robot that does everything, a single motor failure could take offline your entire household automation system. The financial logic is brutal. A specialized robot that costs

Boston Dynamics might be pushing its humanoid Atlas into production, but even Hyundai—the company actually manufacturing it—sees it fitting into industrial roles, not homes. In factories, where environments are controlled and tasks can be carefully orchestrated, a humanoid might eventually make sense. But the margin between "might make sense" and "definitely makes sense" is still very wide.

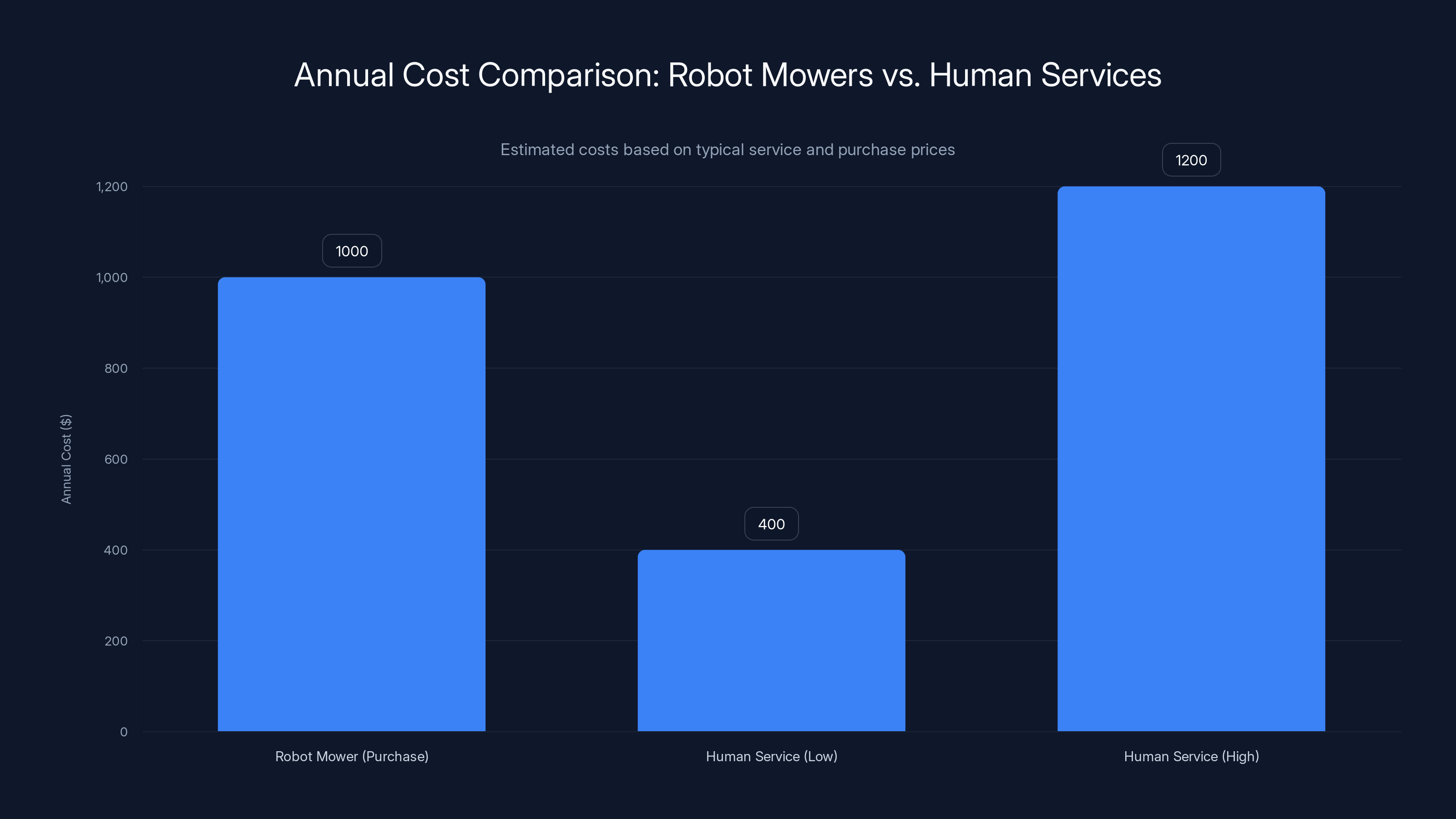

While the initial purchase of a robot mower costs

The Roborock Saros Rover: When Vacuums Get Weird

Roborock's Saros Rover looks like someone asked "what if we gave a Roomba legs?" and then actually went through with it.

On the surface, this seems ridiculous. A vacuum doesn't need legs. It has wheels. Wheels work fine. But then Roborock started thinking about what their current wheeled robots couldn't do. They couldn't climb stairs. They got stuck on thresholds. They struggled on uneven terrain like thick carpets, wooden decks, or outdoor patios. These aren't theoretical limitations. They're problems that actual customers reported when trying to use their vacuums in real homes.

So instead of designing a robot that could do multiple things well, Roborock decided to make a robot that could vacuum literally anywhere. The Saros Rover's articulating legs let it traverse obstacles that would stop a wheeled vacuum cold. It can step over the gap between rooms, climb stairs between floors, and handle the kind of terrain variation that makes most robot vacuums panic. The engineering is genuinely clever: the legs work like synchronized manipulators, measuring distance and adjusting height in real time to maintain contact with the ground even as the robot moves through three-dimensional space.

But here's the important part: this is still just a vacuum. It doesn't fold laundry. It doesn't load your dishwasher. It doesn't water your plants. It vacuums—it just does it in places that previous vacuums couldn't reach.

This is the pattern that defines 2026's robot announcements. Dreame showed the Cyber X at IFA last September and brought it back to CES. It has four tank-tread legs that look "extremely threatening" according to anyone who saw it in person. Those legs don't exist to make the robot more threatening—they exist because Dreame engineers concluded that tank treads would give their vacuum better traction in difficult environments than wheels ever could. It's weird. It's unusual. But it's solving a specific problem within the narrow domain of vacuuming.

Anker's new Eufy robovac that doubles as a diffuser is equally narrowly focused. The entire value proposition is: "We can vacuum your floors AND spray fragrance at the same time." It's not trying to be a general household helper. It's not attempting to optimize for washing dishes or doing laundry. It's saying: "While we're moving around your floor anyway, we might as well spray something pleasant." It's a small optimization to an existing task, not a moonshot for general-purpose robotics.

This pattern reflects something important about how products actually reach the market. The companies that are getting robots into homes aren't the ones trying to solve "everything." They're the ones solving "one specific thing better than it's ever been solved before." Roborock gets robots into homes because their vacuums genuinely work better than alternatives. DJI dominates drones not because a drone can replace a camera crane, but because drones are better at aerial photography than any previous tool. Specialization doesn't feel like progress when you're measuring it against a dream of universal robots, but it's actually the path that leads to universal robotics. You learn to walk before you run.

Beyond Vacuums: The Ecosystem Emerges

If CES 2026 proved anything, it's that the vacuum was just the beginning. Manufacturers are now taking the navigation and autonomy tech developed for robot vacuums and applying it to every other corner of home maintenance.

Robotic mowers are proliferating. Pool cleaners are getting autonomous. Lawn maintenance has historically been a pain point for homeowners—mowing takes time, trimming edges takes precision, and maintaining a large yard can consume an entire weekend for someone working a full-time job. The fact that robot mowers are now arriving suggests manufacturers see this as an opportunity. If a robot can map your home for vacuuming, it can map your lawn. If it can avoid stairs and obstacles indoors, it can navigate trees and garden beds outdoors. The navigation stack transfers directly.

Pool cleaners are perhaps even more interesting because they represent robotics in a different medium entirely. A pool is a controlled environment—unlike a home or a lawn, where obstacles appear unpredictably, a pool's structure is fixed and predictable. This makes it an ideal domain for robotics. A pool-cleaning robot can map the pool floor once and then execute cleaning routines without worrying about new obstacles appearing. The problem is simpler, and simplified problems lead to better robots.

Then there's the explosion of robot toys and companion robots. Ecovacs released its fluffy puppy Lil Milo—a robot that doesn't clean anything but provides companionship and entertainment. Tuya and Robopoet created Fuzozo, a Star Trek Tribble that has its own cellular connection so you can get "AI-enabled emotional support on the go." These aren't serious robots attempting practical tasks. But they prove that consumers are ready to share homes with robots for reasons beyond pure utility. We're comfortable with robots as entertainment and companions, not just tools.

Frontier X's Vex is weirder still: an autonomous robot camera that follows your pet, films them, and then automatically edits the footage into a highlight reel. This requires perception, tracking, navigation, and video editing—a stack of capabilities. But it only uses them for one purpose: making cute videos of your pet. Someone even created a real-life WALL-E at CES, which caused significant discussion online, but nobody's quite sure what it actually does. It looks adorable, though.

Samsung's Ballie—a cute projector bot that was supposed to go on sale in 2025—remains missing in action. Samsung hasn't even mentioned it at the 2026 show. This is instructive. Ballie was supposed to be multi-purpose: project content, provide companionship, help with various household tasks. It was a humanoid dream on a smaller scale. And it couldn't get to market. Ballie might eventually ship, but it's not arriving in 2026, which tells you something about the difficulty of the multi-purpose approach.

The through-line is clear: companies are succeeding with specialized robots and failing with general-purpose ones. The market is rewarding focus.

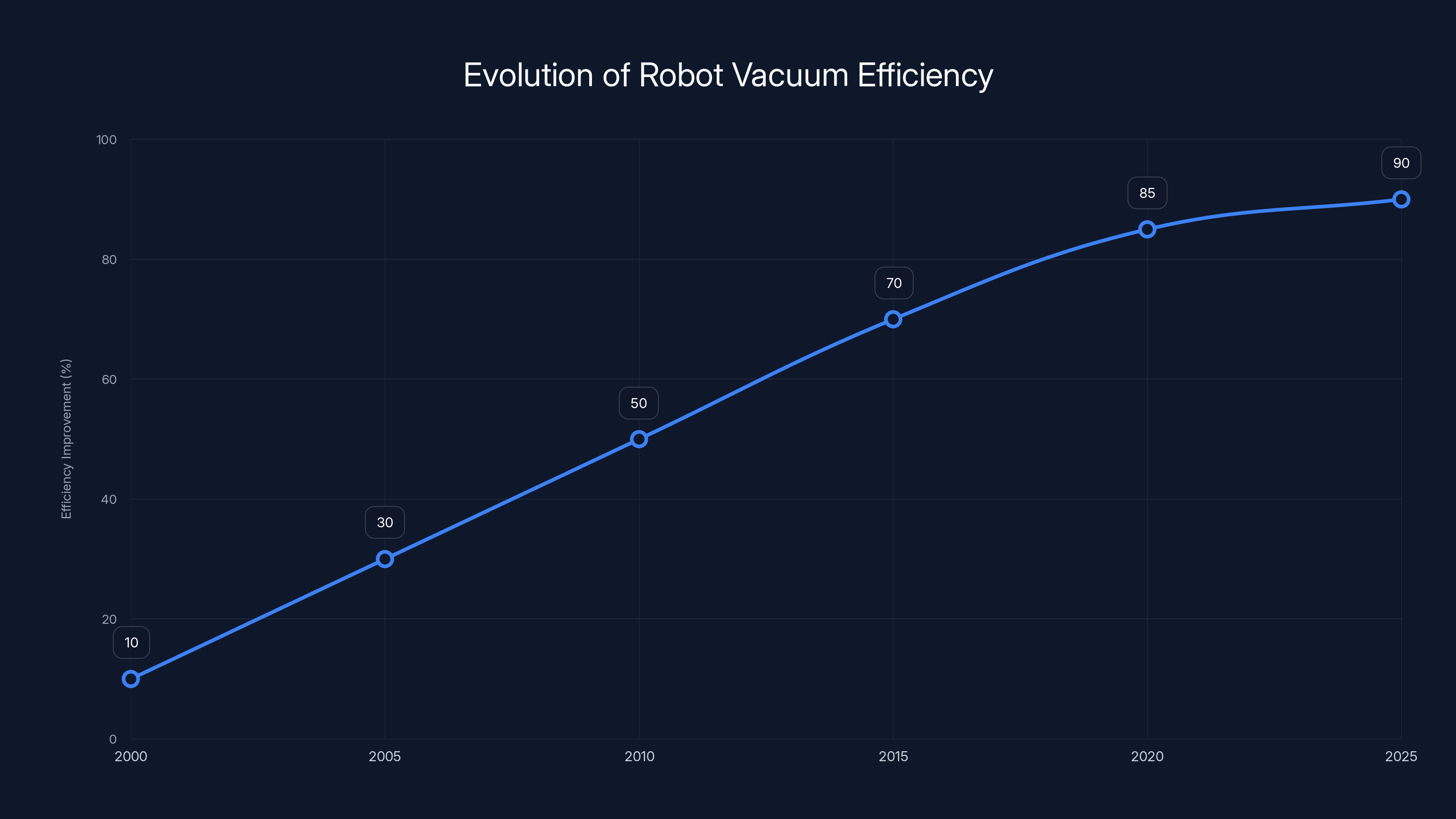

Robot vacuums have seen significant efficiency improvements over the years, reaching a plateau around 2020. Future gains are expected to be incremental. Estimated data.

How Industrial Robotics Mapped the Territory

None of this is surprising if you've been paying attention to industrial robotics over the last two decades.

When factories and warehouses started automating serious work, they faced the same question home robotics is facing now: should we build one incredibly smart robot that does everything, or multiple specialized robots that each do one thing well?

The answer came back immediately and decisively: specialized robots win.

A modern automotive manufacturing facility doesn't have humanoid robots moving between stations. It has robot arms optimized for welding, different robot arms optimized for assembly, specialized pick-and-place robots optimized for component insertion, and mobile robots optimized for transport. Each robot is purpose-built. Each robot is far better at its specific task than any humanoid could be. Each robot is cheaper to maintain and faster to replace.

When Amazon needed to scale warehouse automation, they didn't invest in humanoid robots. They invested in the Kiva system—mobile platforms that move shelves rather than trying to pick items from shelves. This is a pure specialization play. The robot isn't smart about picking objects. It's smart about moving heavy loads from point A to point B. That simplification allowed Amazon to scale to hundreds of thousands of robots across dozens of warehouses.

Ocado, the online grocery company, operates fulfillment centers with similar logic. Their robots are individually specialized: some are designed specifically for moving crates, others for packing bags, others for loading trucks. None of them are humanoid. None of them are general-purpose. But collectively, they can process grocery orders with a speed and precision that no human-staffed warehouse could match.

"The 'adaptability' central to the appeal of humanoid robots isn't a priority," James Matthews from Ocado explained, "especially since any humanoid design bakes in many of the same limitations that hold humans themselves back." A humanoid robot has to move like a human, think in some ways like a human, and adapt to environments designed for humans. But warehouses and factories aren't designed for humans—they're designed for industrial processes. So the robot that works best isn't one that mimics human form. It's one optimized for the specific industrial problem.

LG showed off its humanoid CLOi D slowly loading laundry at CES, and it's still just a prototype. The company is genuinely invested in the humanoid dream. But the humanoid is having trouble achieving the speeds, reliability, and cost-effectiveness that specialized laundry-handling robots might achieve. Even LG—a company that could probably build a practical humanoid if anyone could—is finding that specialization beats generalization.

The industrial lesson is: when you control the environment (and in a warehouse or factory, you do), specialization isn't a limitation. It's the optimal strategy. A home isn't as controlled as a warehouse, but it's far more controlled than the open world. You know the dimensions of your rooms. You choose your floor types. You control which obstacles exist and where. This is why specialized home robots work. They're optimized for an environment you've defined.

The Boston Dynamics Moment: Humanoids in Factories, Not Homes

Boston Dynamics chose CES 2026 to unveil the production version of its humanoid Atlas robot.

This is significant not because it proves humanoids are finally ready to take over your home—it doesn't—but because it proves humanoids are finding their place in exactly one domain: industrial manufacturing, and specifically within companies that are willing to invest heavily in implementation.

Boston Dynamics is owned by Hyundai. Hyundai announced plans to deploy Atlas into its own factories. This isn't Boston Dynamics saying "you can now buy Atlas for home use." It's saying "we're putting our own robot to work in our own controlled environment where we can carefully orchestrate its tasks." This is the industrial robotics lesson playing out in real time. Humanoids might make sense in a factory where every process has been optimized for the robot's capabilities. They don't make sense in a home where the environment is less controlled.

What's telling is what Boston Dynamics didn't announce: a consumer version. No "Atlas will be available for home purchase in 2027." No "we're partnering with appliance makers to integrate Atlas into household automation." Just: "we're deploying it in factories." The world's most advanced humanoid robotics company is quietly acknowledging the uncomfortable truth. Humanoids belong in industrial settings where the environment can be controlled. They don't belong in homes where environments are messier.

This matters because Boston Dynamics represents the cutting edge of robotics research and engineering. If anyone could create a practical household humanoid, it would be Boston Dynamics. But they're not. Instead, they're deploying their humanoid in the exact environment where humanoids make sense: factories.

The lesson here shouldn't be lost: the most advanced roboticists in the world looked at humanoid robots and decided their best use case was industrial automation in controlled environments. The future of humanoids isn't your home. It's manufacturing. And manufacturing is probably where humanoids will stay for the next 10 to 15 years, if not longer.

This is humbling, but it's also clarifying. It means we should stop waiting for the robot butler. We should start thinking about the ecosystem of specialized robots that are actually arriving. We should focus on what's solvable right now rather than what's theoretically possible in some distant future.

Specialized robots excel in cost efficiency, task speed, and reliability, while humanoid robots offer greater flexibility. Estimated data based on typical robotic task performance.

The Ecosystem Approach: Why Three Good Robots Beat One Mediocre One

Let's do some actual math on this because it changes everything.

Suppose you want home automation. You could wait for a humanoid home robot that does everything. That robot would cost somewhere between

Alternatively, you could buy an ecosystem approach: a robot vacuum (

But here's the real calculation:

Specialization Efficiency Rate: When a specialized robot does one task repeatedly, it optimizes for that task. A specialized vacuum might clean your floors 20% faster than a humanoid would, use 15% less battery, and miss obstacles 30% less often. That small compounding efficiency means the specialized robot actually saves you more time overall, despite not being "general-purpose."

Maintenance Cost Ratio: The specialized robot ecosystem might have three times as many individual robots, but each is simpler. If the failure rate for the humanoid is 10% per year and repair costs

Time to Market and Innovation Velocity: Roborock released the Saros Rover concept in 2025 and is bringing it closer to production at CES 2026. That's a 12-month cycle. Boston Dynamics has been working on its humanoid for years, with no clear home deployment date. When you specialize, you iterate faster. You learn faster. You improve faster. The specialized robot ecosystem will improve dramatically over the next five years. The humanoid robot will improve incrementally, if at all.

This is why the ecosystem approach isn't a compromise. It's the actual superior strategy given current technology and economics.

Why Robot Mowers Matter More Than You Think

Robot lawn mowers seem like a luxury. They're not. They're a bellwether for how robotics is actually evolving.

Lawn maintenance is one of the most time-consuming household tasks in the United States. The average person with a lawn spends somewhere between 5 and 10 hours per month maintaining it—mowing, trimming, edging, and dealing with grass clippings. For a household with limited time, this is genuinely painful. You can hire someone to mow your lawn, but that costs

A robot mower handles this autonomously. You set up the perimeter, program your preferences, and the robot mows on a schedule. Modern robot mowers can handle slopes, navigate around obstacles, and return to a charging station when their battery runs low. Some models can even mulch the clippings back into the lawn, eliminating the need to collect and dispose of grass waste.

The reason robot mowers matter is because they prove autonomous navigation in the real world is solvable. A lawn is messier than a living room. It has variable terrain. Obstacles appear unpredictably. Weather changes throughout the season. If a robot can handle lawn mowing reliably, that same company can apply that knowledge to other problems. That's why almost every manufacturer of robot vacuums is also building robot mowers. They're leveraging the same navigation stack, the same sensor suite, the same algorithms. The specialization compounds.

Moreover, robot mowers are becoming genuinely accessible. You can buy a solid robot mower for

The expansion from vacuums to mowers to pool cleaners isn't random. It's a calculated strategy. Manufacturers are taking the autonomous navigation tech that works and applying it to every household task that involves movement and pattern following. This is specialization at scale. This is the future arriving—not as a single robot butler, but as an interconnected ecosystem of purpose-built machines.

Estimated data shows that tasks like security monitoring and cooking present higher challenges for all-in-one home robots due to their complexity and need for specialized hardware.

The Pool Cleaner Revolution: Where Robots Win Completely

Pool cleaning is where robots have the highest chance of success because pools are the most controlled household environment.

Unlike a living room or a yard, a pool is static. Its dimensions are fixed. The terrain—the pool floor—doesn't change month to month. There are no obstacles appearing unpredictably. There are no weather-induced challenges (the pool is outside, sure, but the water conditions are relatively consistent). This predictability is gold for roboticists.

A robot pool cleaner can be designed to do one thing exceptionally well: traverse the pool floor, recognize debris, and clean it up. The robot doesn't need to worry about navigating stairs (unless the pool has them, in which case the robot simply avoids them). It doesn't need to recognize and avoid random objects. It doesn't need to handle weather variations or unexpected obstacles. The problem simplifies dramatically.

Because the problem is simpler, the robot is cheaper. Current pool cleaners range from

Moreover, pool cleaners work. They actually solve a real problem people face. Unlike some robot initiatives that feel like solutions seeking problems, a robot that cleans your pool is delivering tangible value. You spend five minutes setting it up each week, and the pool stays clean. That's a win.

The interesting thing is that pool cleaners have been automated for years—the technology is relatively mature. But they're resurging at CES 2026 because they fit the broader ecosystem narrative. As companies build more robots, they need more target markets. Pool cleaning is an obvious one. And because it's solvable, it works. Pool cleaners prove that specialization isn't limiting. It's enabling.

Robot Companions and the "Why" Question

Then there are the companion robots, and they raise an entirely different question: Do robots need to be useful to be valuable?

Ecovacs' Lil Milo is a fuzzy robot that looks vaguely like a puppy. It doesn't clean anything. It doesn't perform household tasks. It exists to provide companionship, entertainment, and emotional engagement. Similarly, the Fuzozo robot is a Star Trek Tribble with cellular connectivity for AI-powered "emotional support on the go."

These seem absurd until you realize they're solving a real problem: loneliness and the human need for companionship. Not everyone can have a pet. Not everyone can easily travel with a pet. But many people want something interactive and engaging to interact with.

This is significant because it shows that home robots are expanding beyond pure utility. We're not just automating chores. We're creating digital companions. We're building robots that provide emotional value rather than functional value.

The question here is whether this market is real. Are people genuinely willing to spend money on robot companions? Judging by the proliferation of announcements at CES, some companies think they are. This could be the next wave of robotics: not robots that do things for us, but robots that exist to interact with us.

Of course, this requires a completely different engineering focus. A companion robot doesn't need to navigate complex environments or perform precise manipulations. It needs to be cute, responsive, and engaging. The engineering challenges are different. The success metrics are different. The market is different.

But if these robots find an audience—and there's reason to believe they will—then the robotics industry becomes even more diverse. You'll have task robots (vacuums, mowers, pool cleaners), companion robots (Tribbles and robot puppies), and utility robots (humanoids in factories). Each optimized for a specific purpose. Each succeeding because of that specialization.

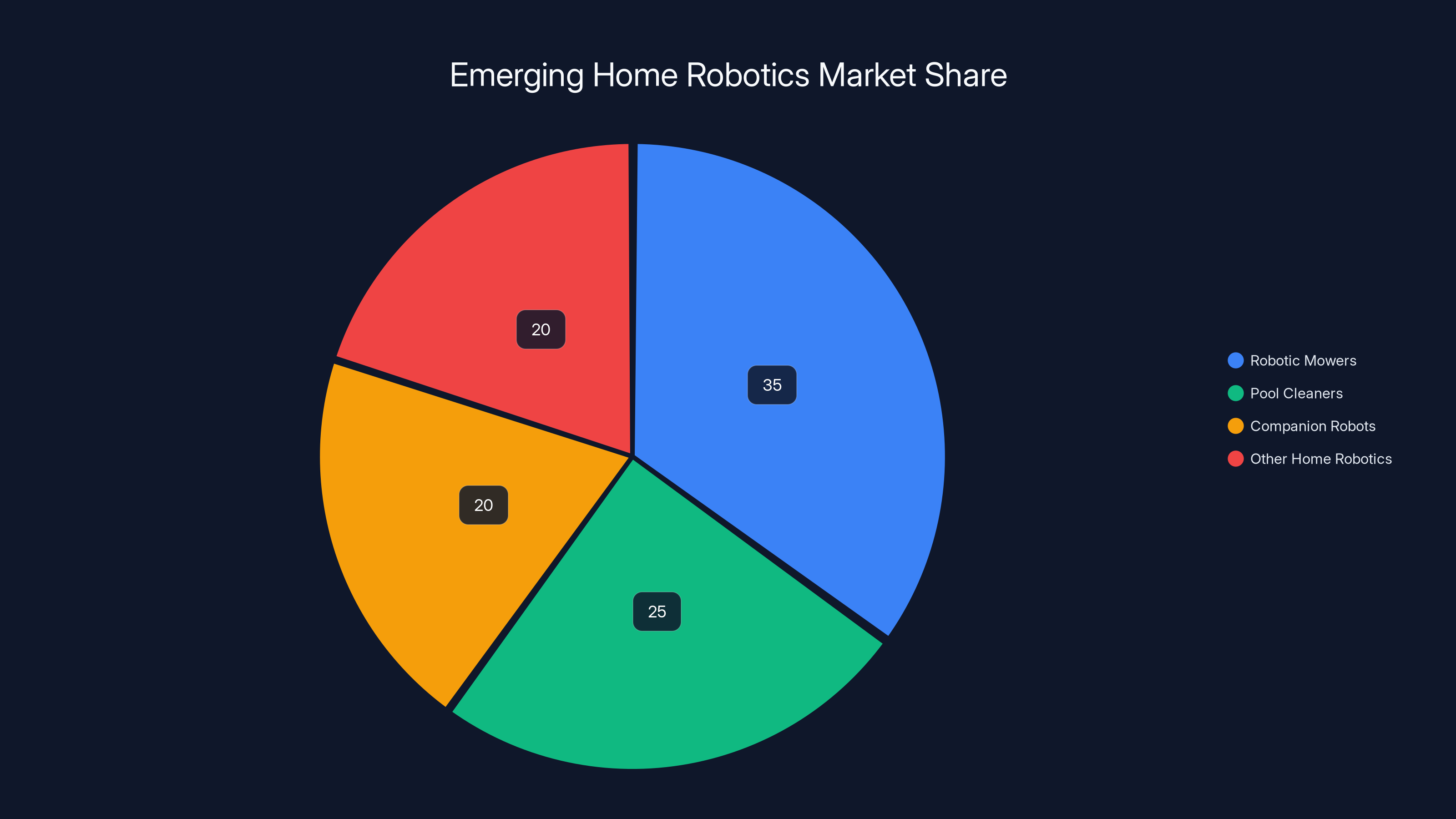

Estimated data shows robotic mowers leading the home robotics market with a 35% share, followed by pool cleaners at 25%. Companion robots and other home robotics each hold a 20% share, indicating a diverse and growing ecosystem.

The Laundry Problem: Why Human-Shaped Doesn't Mean Human-Good

LG's humanoid CLOi D is designed specifically to do laundry. It moves like a human, thinks in some ways like a human, and attempts to handle clothing the way a human would.

And it's incredibly slow.

At CES, CLOi D demonstrated loading a washing machine. The movement is deliberate and careful. It's trying to handle delicate fabrics gently. It's trying to position items in a way that won't wrinkle them. It's doing all the things a careful human would do. And as a result, the entire process takes much longer than a human would actually spend on laundry.

Here's the thing: laundry is a problem that could be solved with specialization. Imagine a robot designed specifically for loading washing machines. Not a humanoid. Just a manipulator arm positioned above the washer with gripper technology optimized for grabbing and placing clothing. This robot wouldn't need to understand how to fold clothes or arrange them gently. It would just need to dump clothes into the washer quickly and reliably. You could train it on hundreds of thousands of clothing items in simulation before it ever touched a real garment.

Such a robot would be faster than CLOi D, cheaper to manufacture, and easier to maintain. It would solve the specific problem of getting clothes into a washer, which is actually what people care about. But it wouldn't look like a human. It wouldn't feel intuitive to anyone who hasn't worked with industrial robots.

LG chose the humanoid path because it appeals to consumer expectations. People understand what a humanoid robot is doing. They can watch CLOi D load laundry and say "oh, a robot that does chores." But this aesthetic choice comes at a cost: slower performance, higher price, and unnecessary complexity.

Clothesfolding, by the way, remains almost completely unsolved in robotics. There was a research paper a few years ago about a robot that could fold clothes, and it was celebrated because the problem is so hard. Cloth is deformable. It has many configurations. Recognizing when you've successfully folded it is a perception challenge. This is exactly the kind of problem where specialization might help—a robot specifically designed for cloth handling rather than a general-purpose humanoid trying to figure it out.

But such a robot would look weird. It would have specialized grippers and sensors. It wouldn't look "like a robot butler." And consumers might not buy it. So we're stuck watching humanoid robots struggle with laundry rather than embracing specialized robots that could solve the problem efficiently.

The Missing AI: Why Large Language Models Aren't the Solution

Here's a controversial take: the explosion of large language models and generative AI hasn't solved any fundamental problems in home robotics. If anything, it's distracted from what actually needs to happen.

When people talk about AI and robots, they're usually imagining something like: you tell a humanoid robot "do the laundry," and it reasons through the steps, figures out what needs to happen, and does it. This narrative is appealing. It feels like progress. But it's not what's actually limiting robot development.

The limiting factor in home robotics isn't understanding instructions. It's manipulating physical objects reliably. It's navigating complex environments with certainty. It's gripping delicate things without crushing them. These are mechanical and perception problems, not reasoning problems. A large language model doesn't help a robot understand how to hold an egg without breaking it. It doesn't teach a robot gripper how to pick up a coffee cup without spilling. It doesn't help a vacuum navigate stairs.

This is why the successful home robots at CES 2026 don't rely heavily on advanced AI for reasoning. The Saros Rover doesn't use Chat GPT to figure out how to vacuum stairs. It uses mechanical legs and navigation software designed specifically for that task. Anker's diffuser vacuum doesn't use machine learning to decide when to spray fragrance. It uses a schedule and a timer.

Don't get me wrong: specialized AI absolutely helps in robotics. Better object recognition helps a vacuum avoid tangling on cords. Better localization helps a mower stay within boundaries. But these aren't advances enabled by large language models. They're advances in computer vision, sensor fusion, and specialized deep learning models trained on specific robotics problems.

The hype cycle around AI has made people expect that better reasoning would solve robot problems. But robotics is fundamentally about physics and perception, not reasoning. You can have the smartest robot in the world, but if its gripper is weak, it can't pick anything up. You can have the best language model, but if the robot's wheels slip on certain floor types, it can't navigate.

This is why I think the real progress in home robotics will come from engineers who focus on mechanical and perception problems, not from AI researchers. The specialists will win—even in the domain of AI.

The Five-Year Forecast: What Your Home Actually Looks Like

Let's project forward five years. Let's imagine it's 2031. What does your home look like if the current trajectory holds?

You probably have a robot vacuum. Maybe it's one with legs for stairs, maybe it's still wheels, but it's way better at its job than vacuums are in 2026. It maps your home more accurately. It recognizes objects better. It handles edge cases you currently deal with manually.

If you have a lawn, you have a robot mower. It's cheaper than in 2026 because the technology has commoditized. Multiple manufacturers offer models at different price points. Your mower might be smart enough to navigate complex landscaping or adjust cutting patterns based on grass growth rates.

If you have a pool, you have a robot pool cleaner. It might be smart enough to predict when cleaning is needed based on weather patterns or leaf falling seasons.

You might have a robot arm in your kitchen designed specifically for loading dishwashers, or a specialized robot designed for laundry, but probably not a humanoid trying to do both.

You might have a companion robot, depending on your interests and needs. Maybe it's something that evolved from current designs, maybe it's something we can't predict yet.

What you probably don't have is a single all-purpose humanoid robot doing everything. Not in 2031. Probably not in 2040. The industrial logic is too strong. Specialization works. Generalization doesn't, at least not yet.

Why does this matter? Because it changes how you should think about home automation. You shouldn't wait for the perfect all-in-one robot. You should buy specialized robots as they become available, as prices drop, and as they solve actual problems in your life. Start with a vacuum if you don't have one. Add a mower if you have a lawn. Build the ecosystem gradually.

The future isn't a robot butler. It's an army of robots, each doing one thing brilliantly.

What This Means for Manufacturers and Investors

The business implications are profound.

For a long time, the dream was to be the company that builds the all-purpose home robot. Be Apple for robots. Be the one company that solves the problem. Investors loved this narrative. It was cleaner. It was more compelling. It was venture-scale thinking.

But the evidence from CES 2026 and industrial robotics suggests the winners will be companies that build specialized robots, execute well, and then expand into adjacent domains. Roborock isn't trying to build a humanoid. It's trying to build the best possible vacuum, then the best possible mower, then the best possible pool cleaner. Each robot is a way to deepen its relationship with customers and gather more data about how people interact with robots in their homes.

This is actually better for consumers. You get better products faster. You get more choice. You get innovation velocity instead of vaporware.

For investors, it's less romantic but more profitable. The narrative shifts from "will this be the robot company?" to "does this company execute well in its chosen domain?" It's less venture-fairy-tale and more operations and execution.

For manufacturers, it's a call to focus. The companies succeeding at CES 2026 aren't the ones trying to do everything. They're the ones who've made hard choices about what to build and then built it better than anyone else.

The Boston Dynamics Path: Industrial First, Consumer Later

There's one possible future where humanoid robots eventually do make it into homes. But it doesn't happen the way most people imagine.

It happens in reverse. Instead of companies building consumer humanoids and then adapting them for industry, companies build industrial humanoids and then, if the economics make sense, adapt them for consumer use. This is the Boston Dynamics path: deploy in factories first where you can control the environment, learn from that deployment, iterate the design, reduce costs through manufacturing scale, and eventually, maybe, bring a commercial product to consumers.

But this path takes decades. It takes successful industrial deployments. It takes cost reductions of 80% or more to reach consumer price points. It requires solving problems in controlled environments first before attempting to solve them in uncontrolled ones.

Boston Dynamics is on this path. Hyundai is investing in Atlas for factories. That's the beginning. The humanoid might reach homes in 10 years, or 20, or never. But if it does, it will be because it proved its value in industry first.

This is worth understanding because it resets expectations. The humanoid robot future exists. It's just further away than most people realize, and it's arriving through industrial deployment, not consumer enthusiasm.

The Last Robot Vacuum: A Contrarian Take

Here's something worth considering: maybe the robot vacuum represents peak robotics specialization. Maybe we're near the limit of how much better we can make a dedicated vacuuming robot.

Think about where we started: basic wheeled platforms with brushes and motors. Think about where we are now: complex systems with multiple sensors, AI-assisted navigation, object recognition, and environmental mapping. We've added arms for debris handling. We've added legs for stairs. We've added AI for pattern prediction.

What's left? Maybe we get 10-20% more efficient. Maybe we solve the problem of different floor types perfectly. But the fundamental breakthrough—turning a basic robot into something that can handle 90% of vacuuming scenarios autonomously—has already happened. The next improvements are incremental.

This doesn't mean vacuums are done improving. It means we're past the exponential improvement phase and into the optimization phase. Robots will get better, but the gains will be smaller, and they'll come slower.

Unless someone figures out how to significantly reduce cost—say, a robot vacuum that's 50% cheaper than current models but still 95% as capable—the robot vacuum market might plateau. Which is fine. It means we move to the next problem. We've solved vacuuming. What's next? Laundry, harder. Cooking, much harder. But each problem solved is progress.

The Uncanny Valley Problem: Why Some Robots Creep Us Out

There's a psychological dimension to home robotics that doesn't get discussed enough: the uncanny valley.

The uncanny valley is that weird feeling you get when something looks almost human but not quite. It's the reason some robot designs feel creepy while others feel friendly. Spot, the Boston Dynamics robot that looks vaguely dog-like, doesn't trigger the uncanny valley. It's different enough from a dog that we don't expect it to act like one. But a robot that looks 90% human but isn't—that triggers deep discomfort.

This has real implications for home robotics. A vacuum that looks like a disc is fine. A mower that looks like a small car is fine. A companion robot that looks like a Tribble is actively cute. But a humanoid that looks sort of human but moves a little bit wrong? That's unsettling.

LG's CLOi D walks a fine line here. It looks enough like a humanoid that you understand what it's trying to be, but different enough that it doesn't trigger the uncanny valley. That's intentional design. And it suggests that even if humanoid robots do make it into homes, they'll probably be designed to avoid looking too human.

This preference for specialization over humanoid form isn't just an engineering choice. It's a psychological one. We're more comfortable with a robot that looks like a vacuum than one that looks like an android butler. The form factor matters.

So even if the engineering challenges of humanoid robots were completely solved tomorrow, we'd still probably prefer specialized robots. They feel right. They look right. They don't trigger deep psychological discomfort.

FAQ

What is the difference between specialized robots and general-purpose humanoid robots?

Specialized robots are designed for one specific task, like vacuuming or mowing lawns. They optimize every component for that single task, which makes them cheaper, faster, and more reliable than a general-purpose humanoid robot that tries to do multiple things. Humanoid robots are designed to mimic human form and adapt to different tasks, but this flexibility comes at the cost of efficiency in any particular task. Industrial robotics proved that when you have a controlled environment, specialized robots outperform humanoid ones.

Why hasn't the robot butler promised by science fiction arrived yet?

The robot butler requires solving multiple extremely hard problems simultaneously: mechanical manipulation, object recognition, physical reasoning, planning, and adaptability to unpredictable environments. Each of these problems is solvable individually, but building a single machine that solves all of them at consumer cost is extraordinarily difficult. Economics and physics both favor building multiple specialized robots instead. Companies trying to build the humanoid dream have repeatedly failed to reach markets, while companies building specialized robots have achieved real commercial success.

How does specialization help robot manufacturers scale?

When a company builds a specialized robot for one task, it can optimize the entire system for that task. This leads to simpler manufacturing, easier maintenance, cheaper repairs, and faster innovation. Companies like Roborock can take their vacuum navigation technology and apply it to mowers and pool cleaners, reusing the core software and mechanical platforms while specializing for new domains. This compounds efficiency gains and speeds time-to-market for new products.

What role does AI play in home robotics?

AI helps with specific problems like object recognition, localization, and pattern prediction, but it doesn't solve the fundamental challenges of home robotics. The real limiting factors are mechanical—how to grip delicate objects, navigate stairs, handle different floor types—and perceptual, not reasoning problems. Large language models and generative AI haven't significantly advanced home robotics because the bottlenecks aren't in instruction understanding or planning. They're in physics and perception.

Will humanoid robots ever reach homes?

Likely yes, but probably not for 10 to 20 years, and only after they prove their value in industrial settings first. Companies like Boston Dynamics are deploying humanoids in factories now, where controlled environments allow them to operate reliably. If industrial deployment succeeds and costs drop through manufacturing scale, consumer versions might eventually become viable. But the timeline is much longer than most people expect, and the path is industrial-first, not consumer-first.

Why are companies making robot mowers and pool cleaners now?

Manufacturers are applying navigation and autonomy technology that they've already developed for robot vacuums to other household tasks. This reuses existing technology, reduces engineering cost, and expands their addressable market. Moreover, these are genuinely useful products that solve real problems people face. A robot mower saves 5-10 hours per month on lawn maintenance, which has legitimate value, making these products viable businesses, not just tech experiments.

What does a realistic home robot ecosystem look like in five years?

Most homes with robots will have three to five specialized machines: a robot vacuum, possibly a robot mower if they have a lawn, maybe a robot pool cleaner if they have a pool, and potentially a specialized robot for another task like laundry. Some homes might have companion robots. Very few homes will have humanoid robots. Each robot will be better and cheaper than current models, but they'll all be specialists, not generalists, because that's where the engineering and economics work.

How does industrial robotics experience inform home robotics?

Warehouses and factories have spent two decades learning that specialized robots outperform general-purpose ones, even in controlled environments. Companies like Amazon, Ocado, and major manufacturers have proven that multiple specialized robots accomplish more, cost less, fail less often, and scale faster than attempting to build one machine that does everything. Home robotics is learning the same lesson and applying it to consumer environments, skipping the phase where companies waste resources on humanoid dreams.

Why might robot vacuums represent peak specialization?

Robot vacuums have evolved from basic platforms to sophisticated systems with AI navigation, object recognition, and multi-floor mapping. We're probably approaching the point where further improvements become incremental rather than transformative. This doesn't mean vacuums stop improving—they'll become cheaper and more capable—but the exponential improvement phase may be ending. This suggests the industry will move focus to unsolved problems like laundry, cooking, and general household management, each requiring its own specialized approach.

What is the uncanny valley and how does it affect robot design?

The uncanny valley is the psychological discomfort people feel when something looks almost human but not quite. This affects robot design because overly humanoid-looking robots trigger this discomfort, while robots that clearly don't mimic humans feel friendly and acceptable. This psychological preference reinforces the engineering preference for specialized robots, because specialized robots don't need to look humanoid. A robot that looks like a disc or a small vehicle doesn't trigger discomfort and can be optimized purely for function.

The Ecosystem Wins

CES 2026 wasn't disappointing because robots arrived and they weren't humanoids. It was exciting because we're finally moving past the humanoid fantasy and into a future that actually works.

The message from the floor was clear: specialized robots are shipping. They're solving real problems. They're getting better. They're becoming cheaper. Companies are making real money from them. This isn't the future we imagined in 1962 when The Jetsons premiered. It's better in almost every way except the aesthetic.

The robot butler was always a fantasy. A single machine trying to do everything would be mediocre at everything. But a vacuum that's exquisite at vacuuming, a mower that's exquisite at mowing, and a companion robot that's genuinely entertaining? That's real progress. That's a future worth building.

We spent 50 years dreaming of Rosey. We're getting something better: a world where you don't need one robot. You get an army of them. Each one brilliant. Each one specialized. Each one actually improving your life.

That might not sound as romantic as the robot butler promise. But it works. And in the end, that's what matters.

Key Takeaways

- Specialized robots are shipping now and working better than generalist alternatives across vacuum, mower, and pool-cleaning categories

- Industrial robotics proved that controlled environments favor multiple specialized machines over single all-purpose humanoids

- Boston Dynamics' industrial-first approach suggests humanoid robots won't reach homes for 10-20 years, if ever

- The future home will contain 3-5 specialized robots, each optimized for specific tasks, rather than one expensive humanoid

- Manufacturers are successfully reusing navigation technology across domains (vacuums to mowers to pool cleaners), proving specialization enables rapid innovation

Related Articles

- AI Companion Robots and Pets: The Real-World Shift [2025]

- Roborock Saros 20 Robot Vacuum: Complete Guide to New Climbing Tech [2025]

- The Wildest Tech at CES 2026: From AI Pandas to Holographic Anime [2026]

- Roborock's Legged Robot Vacuum: The Future of Home Cleaning [2025]

- Wi-Fi 8 is Coming in 2026 (And You Probably Aren't Ready) [2025]

- ASUS Zenbook Duo 2026: The Dual-Screen Laptop Redesign [2025]

![Home Robots in 2026: Why Specialized Bots Beat the Robot Butler Dream [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/home-robots-in-2026-why-specialized-bots-beat-the-robot-butl/image-1-1767732055791.png)