The Myth Behind the Machine: Disney's Hercules Titans Aren't What You Think

When you watch Disney's latest take on Hercules, something feels different about those towering Titans. They move with an unsettling realism that hand-drawn animation can't quite capture. They don't glide across the screen like traditional animated characters. Instead, they lumber. They grunt. Their shoulders shift with actual weight.

That's because Disney didn't animate them at all.

Instead, the entertainment giant engineered them. Buried beneath layers of digital rendering and carefully placed shadows, the Titans are brought to life by a network of mechanical exoskeletons operating underwater in special effects tanks. It's a production technique so unconventional, so hidden from the viewer's eye, that it feels like a magic trick pulled off right in front of millions of people who had no idea they were watching real machinery.

This isn't just a footnote in modern visual effects. It's a fundamental shift in how major studios approach character animation, one that raises questions about the future of entertainment production, the blurring lines between practical effects and digital artistry, and whether audiences can even distinguish between hand-crafted illusions and algorithmic rendering anymore.

Let me walk you through how this actually works, why Disney made this choice, and what it means for animation's future.

The Traditional Animation Problem: Why Hand-Drawing Wasn't Enough

Disney has been animating characters for nearly a century. Snow White, Cinderella, The Lion King, Aladdin—these films defined what animation could be. The studio perfected the art of bringing impossible creatures to life through pure artistry and frame-by-frame dedication.

But there's a fundamental limitation to traditional animation, especially when it comes to large, physically imposing characters like mythological Titans. Hand-drawn or even computer-generated animation can make these creatures move, but it struggles with one critical element: weight.

When an animator renders a 40-foot-tall fire Titan walking across the landscape, they have to convince viewers that this thing has mass. Gravity affects it. The ground shifts under its feet. Its muscles strain when it raises its arm. The air around it distorts from the heat it radiates.

Most audiences don't consciously register these details, but their brains absolutely do. When an animated Titan moves and doesn't feel heavy, something registers as "off." The motion reads as weightless, floaty, almost cartoon-like—even if the visual design is photorealistic.

This is called the uncanny valley of motion. Your eye and brain expect to see physics at work. When those physics are approximated rather than actual, something feels wrong, even if you can't articulate exactly what.

For Disney, the solution wasn't to hire more animators or develop better rendering software. It was to stop animating altogether and start building.

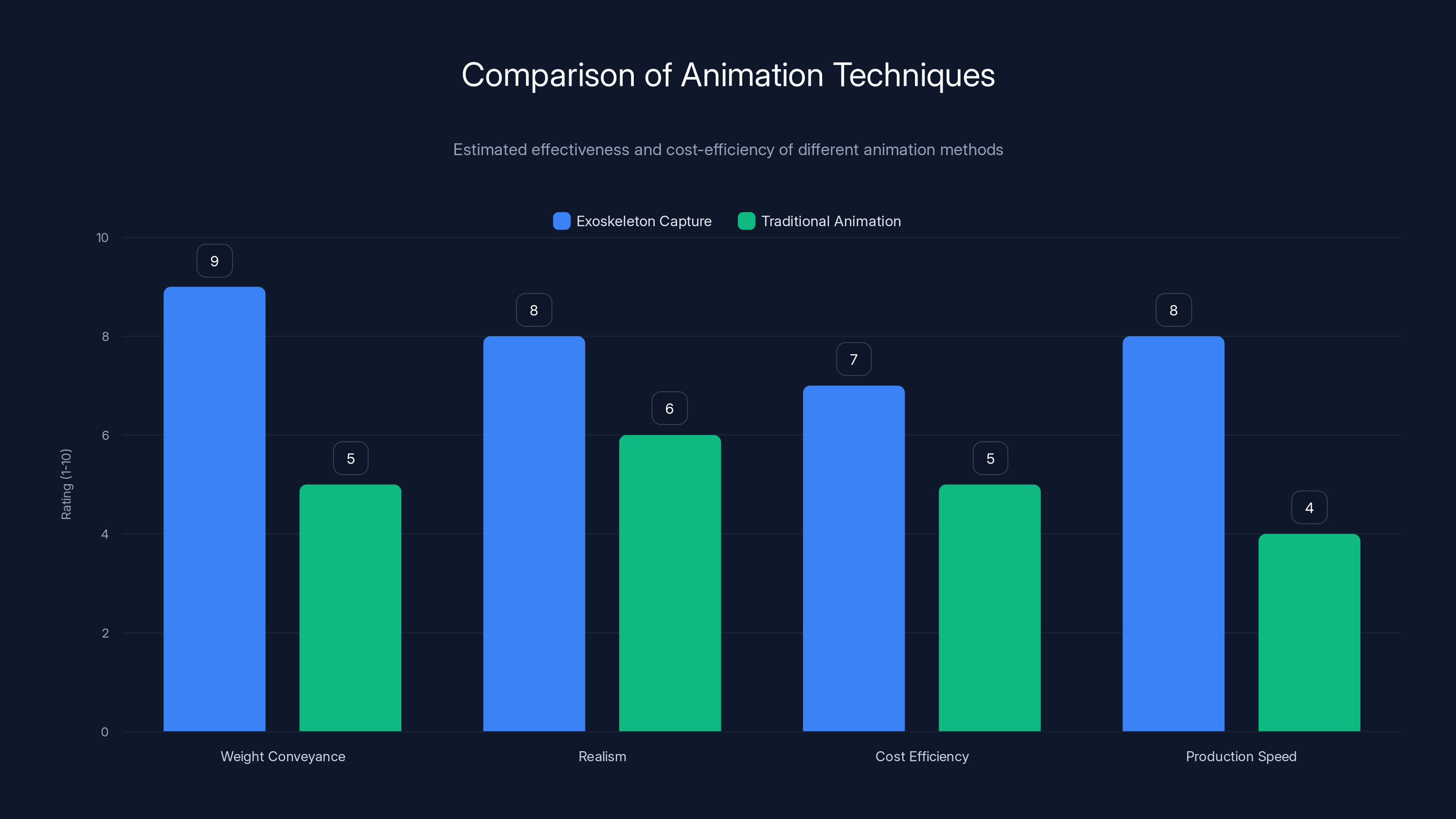

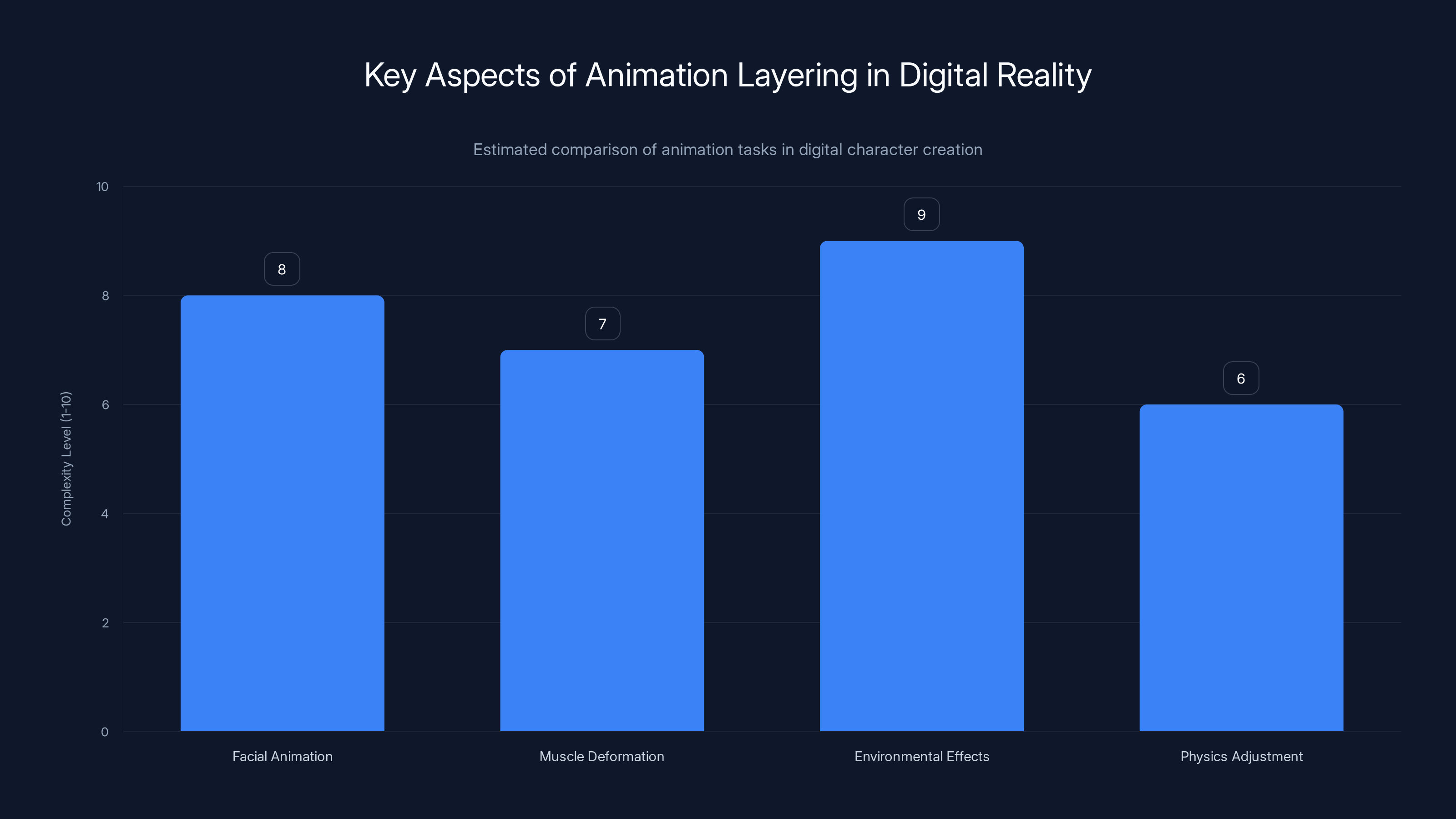

Exoskeleton capture outperforms traditional animation in conveying weight and realism, while also being more cost-effective and faster in production. Estimated data.

Enter the Exoskeleton: How Disney Built Movement Instead of Creating It

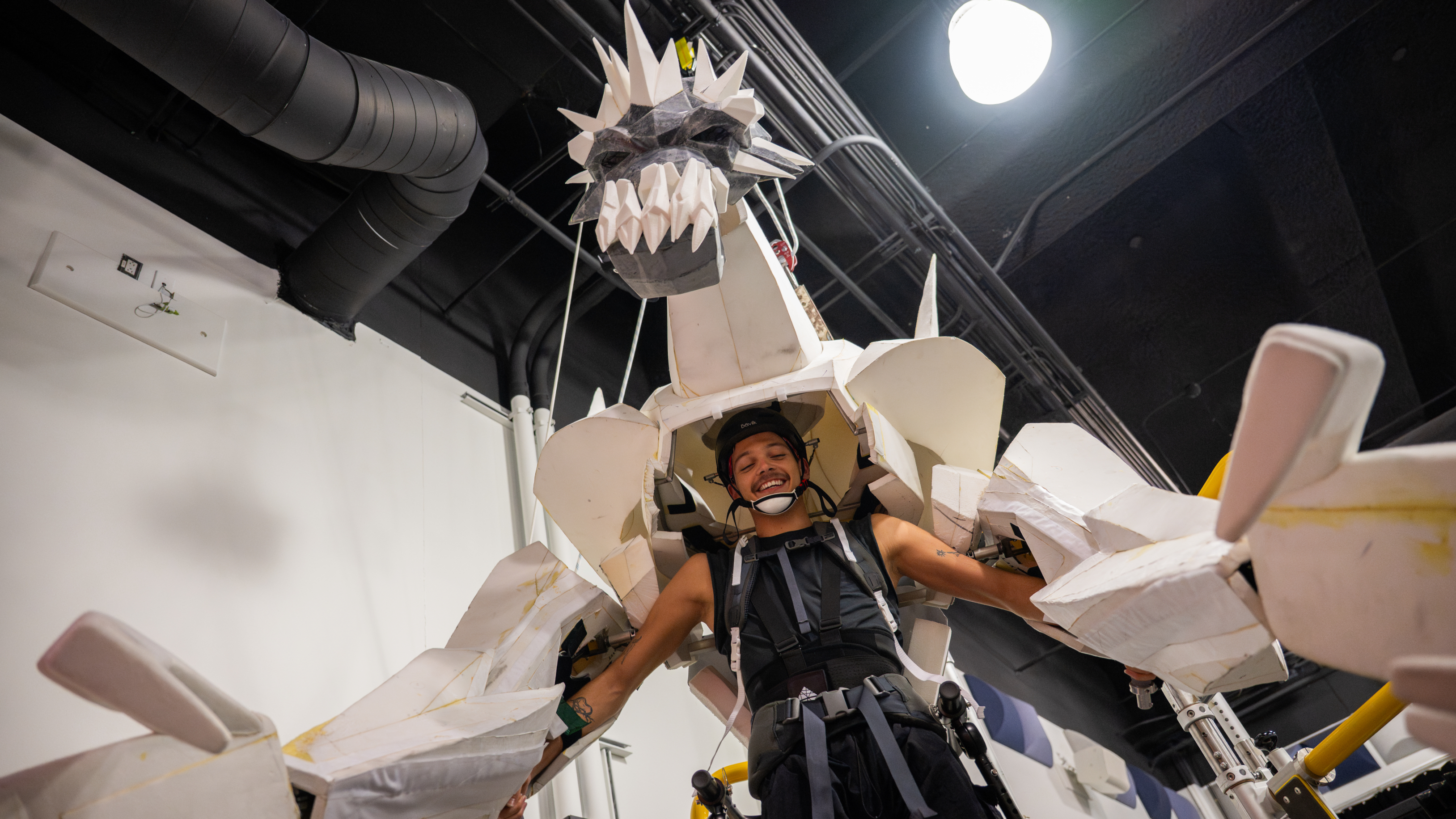

The Hercules Titans visible on screen are the result of a hybrid production pipeline that most viewers will never know existed. Here's what's actually happening: underwater in specially constructed tanks at Disney's effects facility, technicians operate full-scale mechanical exoskeletons that mirror the exact movements the Titans need to make.

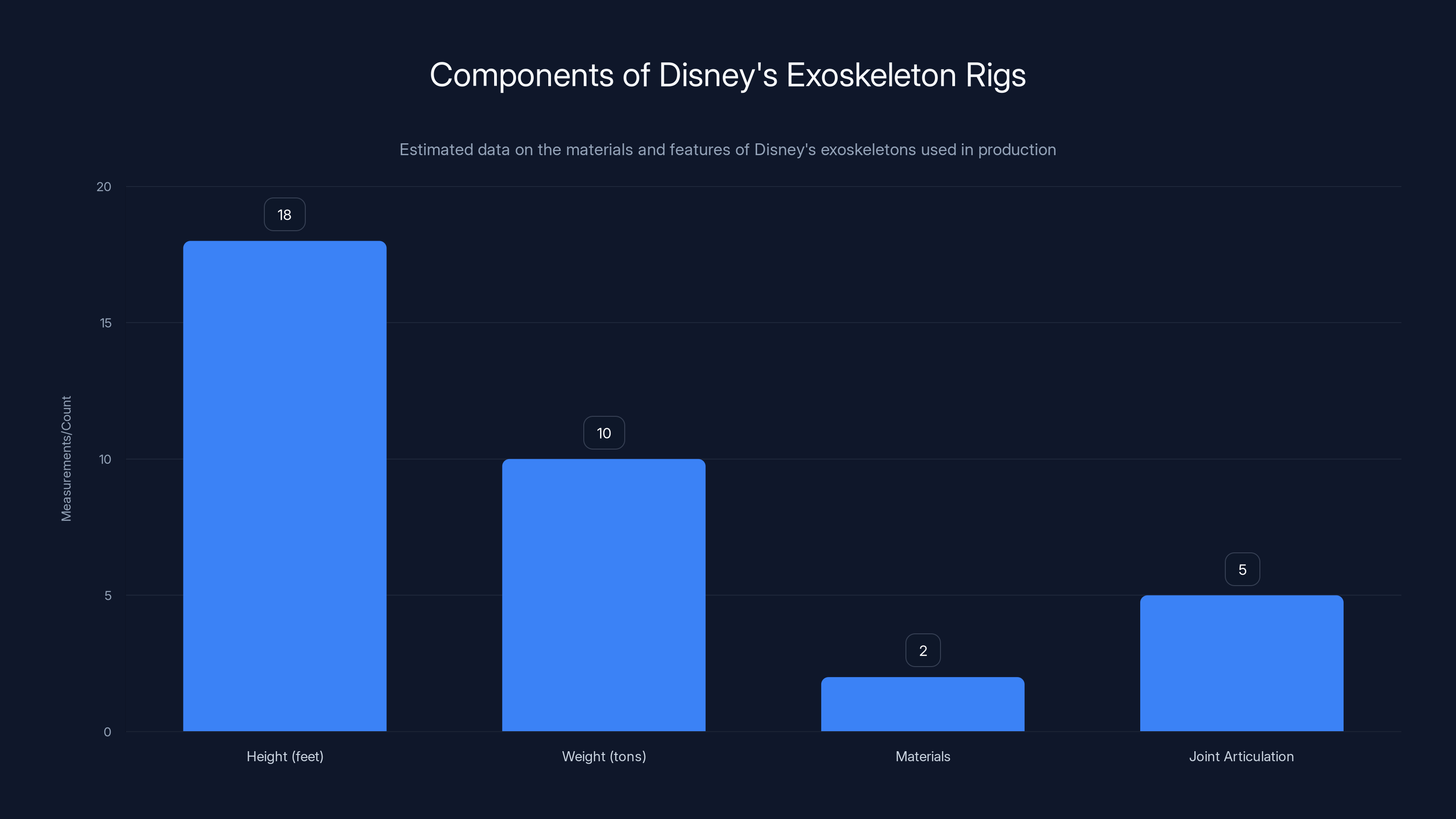

These aren't small-scale puppets. We're talking about rigs that stand 15 to 20 feet tall, constructed from industrial-grade materials like reinforced aluminum and titanium. Each exoskeleton has articulated joints at the shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, and ankles. Operators sit in control pods attached to the rig, their movements translated into corresponding movement in the mechanical frame.

It's similar in principle to how Pacific Rim portrayed Jaeger operation, except this isn't science fiction—it's actual production methodology hidden in plain sight.

The underwater setting is crucial. Water provides natural resistance and buoyancy, which means the operators don't have to fight gravity directly. They can move the 10-ton exoskeleton with relative ease because the water's resistance simulates the weight distribution the Titan should feel. The result? Movement that has real, measurable, physics-based motion.

Once the exoskeleton movement is captured—using arrays of motion capture cameras positioned around the underwater tank—that motion data becomes the foundation for everything else. The animation team takes the genuine motion data and layers digital rendering on top of it. Skin texture, fire effects, lighting, shadows—all of that is added in post-production. But the underlying motion? That's 100% real.

This approach solves the weight problem entirely. Because the movement is actually constrained by real physics (water resistance, gravity, friction), when the digital Titan moves, it moves like something that actually weighs 40 tons. The motion naturally conveys mass because it was created under real physical constraints.

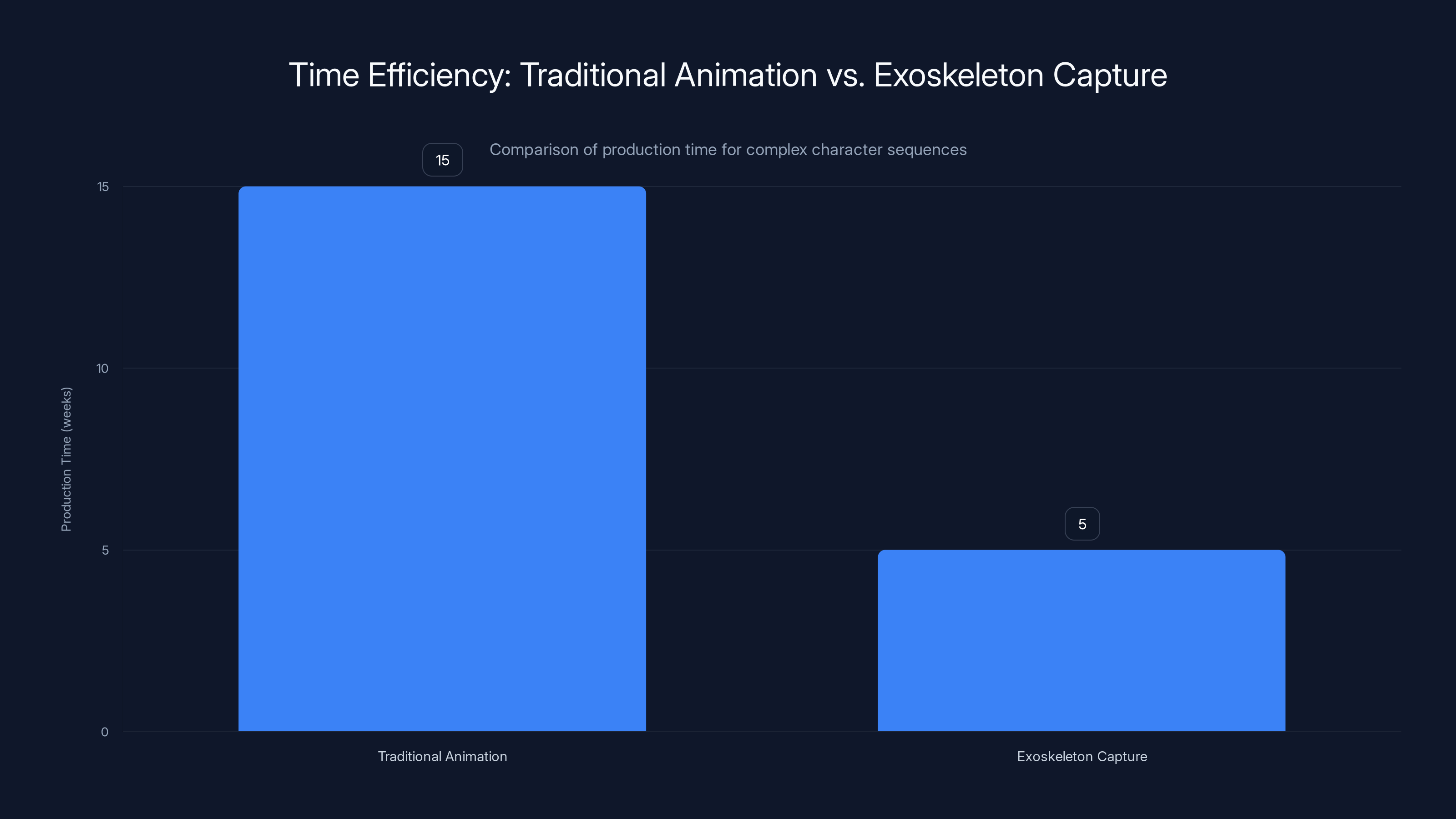

Exoskeleton capture significantly reduces production time by 66-77% compared to traditional animation, making it a more efficient choice for realistic character sequences.

Why Sea-Based Production? The Physics of Water Resistance

You might wonder why Disney chose to build these rigs underwater rather than in a more conventional effects studio. The answer comes down to physics and production efficiency.

Water provides something that air doesn't: predictable, scalable resistance. When a 15-ton exoskeleton moves through water, every motion has to overcome fluid resistance. This resistance is directly proportional to the velocity of movement and the surface area being moved.

For an operator inside the exoskeleton, this means that moving the rig's arm requires genuine effort. It's not effortless like moving your own arm. The exoskeleton provides real tactile feedback through its control mechanisms, which means the operator has to "feel" the weight they're moving and adjust accordingly.

This feedback loop is essential. Without it, operators would unconsciously over-animate—making movements too fast, too fluid, too careless. But when they can feel resistance, when they have to make real effort to move, their natural hesitation and deliberation translates into the final motion.

The underwater environment also solves another critical problem: stability. In air, a 15-ton rig would need massive counterweights and reinforced support structures. The engineering would be incredibly complex. In water, buoyancy handles much of the structural load. The rig stays balanced and stable with far less bracing.

Additionally, water-based capture allows for multiple takes in rapid succession. An underwater rig can be "reset" and moved to a new position for the next take much faster than repositioning a land-based system. This speeds up production schedules and reduces costs.

The Motion Capture Layer: From Mechanical Movement to Digital Data

Once the exoskeleton is moving through the water with an operator inside controlling it, the next layer of the production pipeline kicks in: capture.

Around the underwater tank, Disney has installed multiple infrared motion capture cameras—we're talking dozens of them, positioned at different angles and heights. These cameras track reflective markers placed on the exoskeleton at every joint and key point of articulation.

As the operator moves the rig, the cameras continuously record the position of every marker in three-dimensional space. This data is being recorded at approximately 120 frames per second, which provides incredibly smooth motion data compared to traditional animation's 24 frames per second.

Here's where it gets interesting: this motion capture data is far more detailed than what you'd get from capturing a human actor. Because the markers are tracking mechanical movement, there's no soft tissue deformation, no muscle movement under skin, no hair bounce. It's pure skeletal motion—and that's exactly what Disney's animators need.

The capture data flows into real-time rendering systems. Animators watch a live preview as the exoskeleton moves, seeing the motion instantly translated into a rough digital model. They can make notes: "That arm lift felt right, but the timing on the head turn should be slower." The operator gets feedback, does another take, and the cycle repeats.

This feedback loop is radically different from traditional animation. Instead of an animator handcrafting every frame based on reference footage and director feedback, you have real-time iteration where the movement is being adjusted in real-time based on how it actually looks when rendered.

Disney's exoskeletons are approximately 18 feet tall and weigh 10 tons, constructed from 2 types of industrial-grade materials with 5 articulated joints. Estimated data.

The Animation Layer: Building Digital Reality on Mechanical Foundation

Once the motion capture data is locked in, the animation truly begins—but it's fundamentally different from traditional animation work.

Instead of building movement from scratch, animators are now responsible for building everything around the movement. The skeleton of the Titan—its bone structure, its proportions, its range of motion—is already defined by the motion capture data. Animators layer on top of this foundation.

They sculpt facial expressions. In the underwater tank, the exoskeleton has no face (it's just metal and control systems). The digital Titan's face has to be manually animated to match the emotional content of the scene. A Titan might be raising its arm in anger, and the animator needs to add facial features that convey that same rage.

They add muscle deformation. As the Titan moves, its digital musculature needs to shift and flex realistically. Muscle under tension should bulge. Relaxed muscle should soften. A massive Titan straining to lift a boulder needs visible muscle engagement.

They integrate environmental effects. If the Titan is the fire Titan, its skin needs to render with heat waves, actual flames, and localized lighting effects. If it's the ice Titan, the exoskeleton's movement needs to be overlaid with crystalline effects, frozen surfaces, and cold light simulation.

They adjust physics parameters. The motion capture data is perfect for capturing the operator's intended movement, but sometimes that movement needs subtle adjustments. Maybe a limb needs to move 15% slower for dramatic effect. Maybe the follow-through on a punch needs to be exaggerated for impact.

All of this layering happens in software that integrates the motion capture data with a full 3D character model, special effects systems, and rendering engines. Tools like Motion Builder or custom Disney proprietary software allow animators to see their adjustments in real-time, rendered at near-final quality.

Cost vs. Tradition: Why Disney Chose This Unconventional Path

Building exoskeletons and underwater motion capture facilities is phenomenally expensive. You're talking tens of millions of dollars in infrastructure alone. Most studios would never consider it.

So why did Disney?

The answer is rooted in how animation production costs have evolved. Traditional hand-drawn animation requires teams of animators working frame by frame. A single Titan sequence—maybe 20 seconds of screen time—could require 4,800 individual frames, each one requiring skilled animation work. At professional rates, that's substantial labor cost.

Full 3D computer animation shifted some of that burden to modeling and rendering, but it introduced new problems: long render times, complex simulation systems that frequently break, and the fundamental challenge of creating motion that feels weighty and real.

The exoskeleton approach front-loads the cost in infrastructure and equipment, but then significantly reduces the per-frame labor cost. Once the motion is captured, you're not paying animators to hand-craft every frame. You're paying them to refine and enhance already-present motion.

There's also a scheduling benefit. Traditional animation is unpredictable. A complex scene might take two weeks to animate, and then you show it to the director who decides it's wrong, and the animator has to start over. With exoskeleton capture, you can do 30 takes in a single day. The director reviews the playback and selects the best take. Reshoots are measured in hours, not weeks.

When you factor in the total project timeline and the cost of extended production schedules, the exoskeleton approach becomes financially defensible for large productions like a major Disney film.

Facial animation and environmental effects are the most complex tasks in digital character creation, requiring high levels of detail and integration. Estimated data.

The Technological Requirements: What It Actually Takes to Execute This

Let's get specific about the technology stack required to pull this off. This isn't something you can do in a small studio with off-the-shelf equipment.

Underwater Facility Requirements:

- Tank volume: minimum 800,000 gallons (3,000 cubic meters) to allow for 360-degree movement

- Depth: 35-45 feet to accommodate full-scale exoskeleton operation

- Temperature control: maintained at 78-82°F to prevent operator hypothermia during extended underwater sessions

- Lighting: specialized underwater lighting rigs that won't interfere with motion capture marker visibility

- Support infrastructure: air supply systems, emergency safety equipment, decompression chambers

Exoskeleton Engineering Specifications:

- Weight capacity: 10-15 tons per rig to maintain buoyancy stability

- Degrees of freedom: minimum 26 articulation points (shoulders, elbows, wrists, spine, hips, knees, ankles, neck)

- Response latency: under 50 milliseconds between operator input and mechanical output

- Control sensitivity: operators must be able to make micro-adjustments for subtle emotional expressions

Motion Capture System:

- Camera count: 64-128 infrared cameras minimum for accuracy

- Frame rate: 120+ fps to capture smooth motion with sufficient temporal resolution

- Marker precision: tracking accuracy to within 2-3 millimeters at 30-foot distances

- Real-time processing: servers capable of processing 10+ million data points per second

Data Processing Pipeline:

- Motion capture data export: 2-4 terabytes per hour of shoot time

- Storage requirements: petabyte-scale systems for archival and redundancy

- Rendering systems: render farms with thousands of processing cores

- Software integration: custom bridges between capture systems, animation software, and rendering engines

This infrastructure doesn't exist at most studios. Disney had to build it. That's a multimillion-dollar investment that only makes sense if you're planning to use it repeatedly.

Operator Training: The Human Element in Mechanical Performance

Here's something rarely discussed: the operators inside these exoskeletons are performers, not just technicians.

They undergo extensive training—we're talking 3-6 months per operator to achieve basic competency. The training covers physical endurance (moving a 15-ton rig underwater is exhausting), technical systems (understanding the mechanical feedback), and performance technique.

Performance technique is crucial. An operator needs to understand the character they're embodying. They need to know the emotional context of the scene, the Titan's motivation, the dramatic arc. When you ask them to "lift the arm in anger," they need to translate that emotional direction into actual physical movement that conveys appropriate speed, force, and timing.

This is closer to acting than to traditional animation. The operator is, in a very real sense, performing the role of the Titan. They're just doing it while submerged in a tank and controlling a massive mechanical rig.

Disney's operators are typically drawn from backgrounds in dance, martial arts, or professional stunt work. These are people with highly developed body awareness and the ability to translate emotional direction into physical movement. A dancer understands weight and momentum. A martial artist understands force and impact. A stunt performer understands timing and control.

The training process involves extensive choreography. Directors work with operators to develop specific movement patterns—how the Titan walks, how it raises its arms, how it rotates its torso. These become the "performance vocabulary" that the operator uses when capturing scenes.

Once trained, a single operator can typically work 4-6 hour shifts underwater (with breaks for decompression and physical rest). A complex Titan sequence might require 8-12 hours of shoot time, which means 2-3 operator shifts, possibly with different operators.

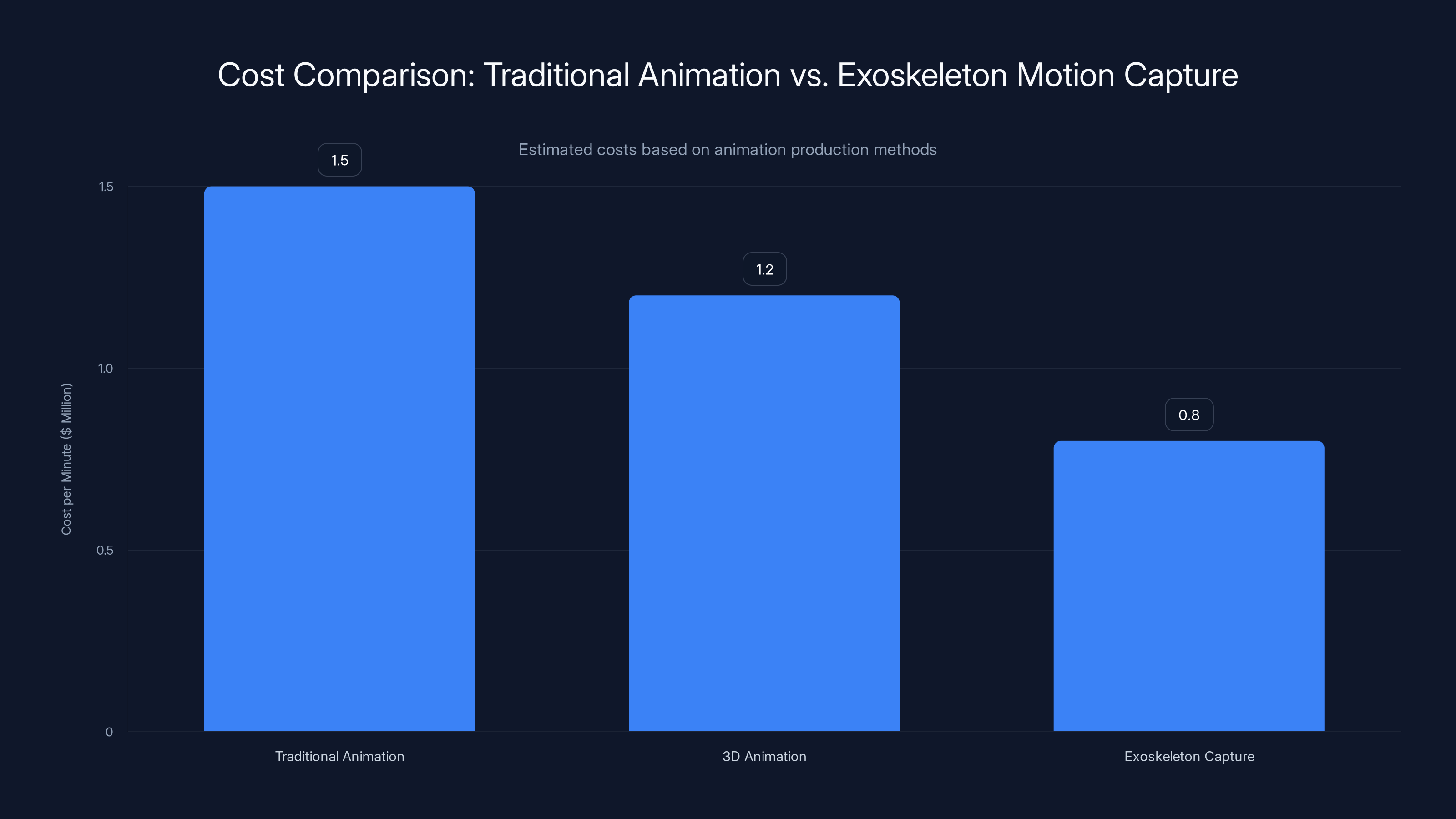

Estimated data shows that exoskeleton motion capture reduces per-minute costs compared to traditional and 3D animation, making it financially viable for large productions.

From Tank to Screen: The Post-Production Pipeline

Once the exoskeleton motion is captured, the footage exists as raw motion capture data (essentially a skeleton moving through space) and underwater video reference (showing the actual rig in the tank).

Neither of these is remotely close to being ready for broadcast.

The motion capture data goes into the animation software. Animators import the skeleton and begin the enhancement phase. This is where the captured motion meets creative interpretation.

Animators refine timing. Sometimes a movement captured from the exoskeleton needs to be stretched or compressed. A head turn that took 0.5 seconds might need to happen in 0.3 seconds for the scene's pacing. This isn't manual frame-by-frame animation—it's procedural adjustment of the motion data.

They adjust volume and magnitude. A large gesture might need to be amplified to read clearly on screen. A subtle movement might need emphasis. These adjustments are made mathematically: scale the translation data on a specific axis by a specific percentage.

They add secondary motion. The primary motion comes from the exoskeleton capture, but secondary motion—hair flowing, clothing moving, skin jiggling—needs to be simulated or animated separately.

They integrate facial animation. The exoskeleton has no face, so the digital Titan's face is animated manually. But it needs to sync with the body movement. If the body is conveying anger through posture, the face needs to reinforce that emotion.

They add effects layers. Fire Titan rendering requires heat wave simulation, flame effects, light refraction. Ice Titan requires crystalline surfaces, frost patterns, cold light. These effects are layered on top of the character model and the rigged skeleton.

The entire process is done within a 3D software environment where the director can review in real-time, request changes, and see iterations quickly. Unlike traditional animation where changes require rework, here changes are often parameter adjustments that can be applied to the entire sequence simultaneously.

The Visual Language: How Audiences Perceive Weight Without Knowing Why

Something remarkable happens when you watch a Titan that was brought to life through exoskeleton capture. You feel its weight.

You don't consciously think, "Oh, this must have been captured mechanically." You just watch the Titan move and your brain registers: this thing is heavy. This thing has mass. This thing is genuinely constrained by gravity.

That perception emerges from subtle details in the motion that would be nearly impossible to engineer from scratch:

Momentum. When the Titan lifts its leg to walk, its upper body naturally compensates. It leans slightly, shifting weight. This isn't something an animator programmed in explicitly; it's an emergent property of the operator's physics-based movement in water. Humans naturally compensate for shifts in balance, and those compensatory micro-movements were captured by the motion capture system.

Friction. When the Titan's foot hits the ground, there's resistance. It can't slide. Its foot plants, the foot stays planted, and then the body rotates around the planted foot. This is exactly how weight works. An animated Titan might glide, with the foot sliding forward slightly. A real-weight Titan plants and stays planted.

Deceleration curves. The operator can't make the Titan's arm stop instantly. The massive weight of the arm means it has momentum. When the operator stops inputting movement, the arm overshoots slightly before settling. This overshoot is physically accurate and reads as weight to the audience.

Breathing. This is subtle but profound. When the captured exoskeleton operator breathes, the entire rig shifts slightly. That captured breathing pattern transfers to the digital Titan. It's a tiny, almost invisible movement, but it exists. It tells the audience: this is a living thing, constrained by biology.

Collectively, these micro-movements create a perceptual experience of weight and presence that's nearly impossible to fake through animation alone. The audience feels it, even if they don't see it.

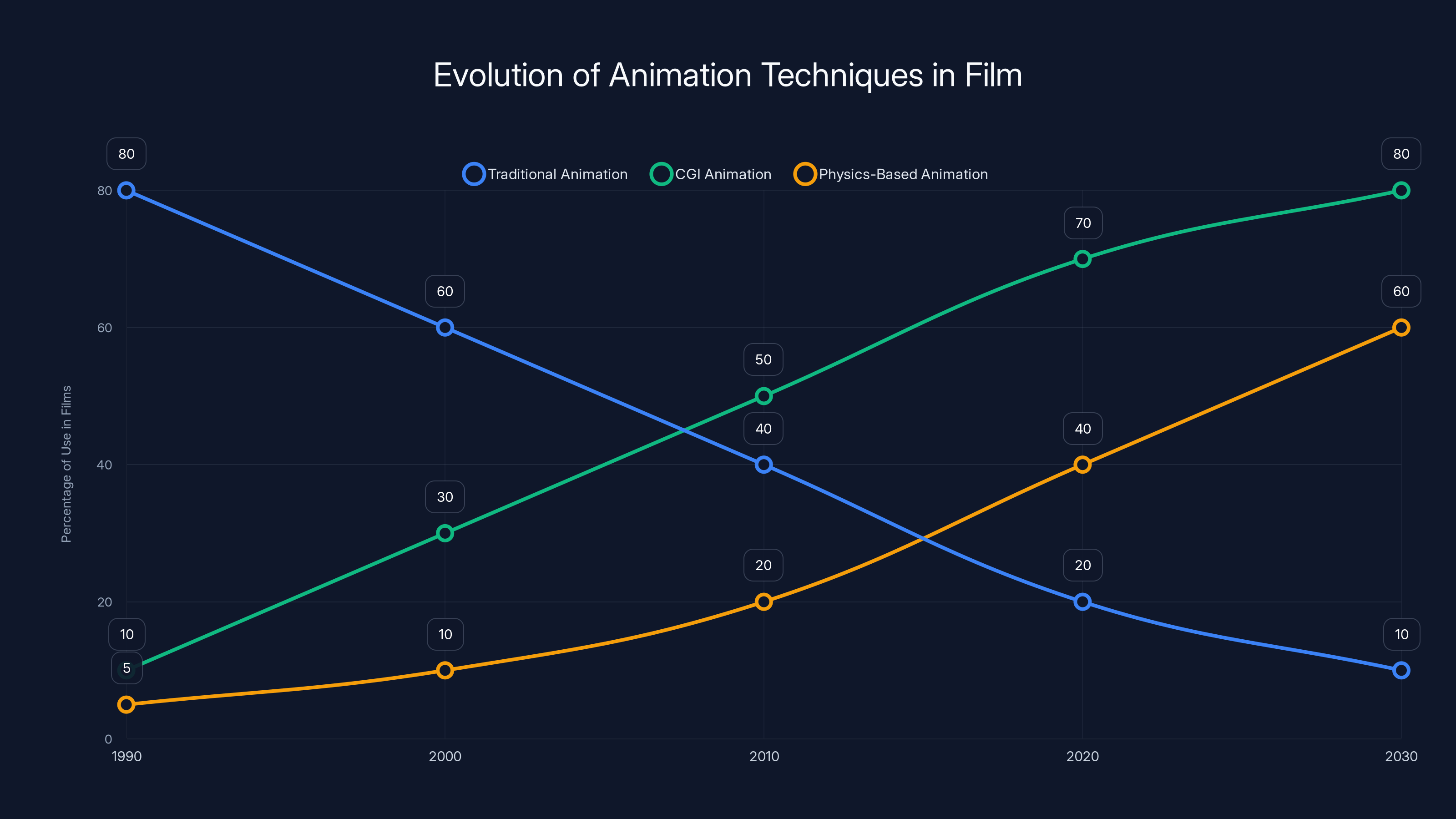

The chart illustrates the projected shift from traditional animation to CGI and physics-based techniques in film. Estimated data suggests a growing trend towards physics-based animation by 2030.

Industry Implications: Is This the Future of Animation?

Disney's approach with the Hercules Titans raises a profound question: is traditional character animation becoming obsolete for large, physically imposing creatures?

It's not likely to replace all animation. Characters that are designed to be stylized, cartoony, or non-human (animals, insects, fantastical creatures with non-human proportions) still benefit from traditional animation. That medium allows for exaggeration, for breaking real-world physics in service of comedy or surrealism.

But for creatures that should feel like they exist in the real world—dragons that feel genuinely heavy, giants that feel genuinely massive, creatures that should feel present and weighty—exoskeleton-based capture offers advantages that are hard to ignore.

Other studios have taken notice. Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) has begun experimenting with similar techniques. Sony's visual effects division has patented several related methodologies. VFX studios in Canada, New Zealand, and India are starting to construct their own underwater capture facilities.

The technology is spreading, but slowly. The infrastructure investment is substantial, and it only makes economic sense for large-budget productions. An indie animated film or even a mid-budget studio project probably won't invest millions in exoskeleton infrastructure.

But for tentpole franchises—Marvel productions, DC films, major fantasy epics—this technology could become standard within the next 5-10 years.

There's also the question of labor. Traditional animation jobs involve skilled artists hand-crafting every frame. Exoskeleton-based capture reduces the demand for frame-by-frame animators but increases demand for motion capture operators, technical specialists, and effects artists. The job market shifts, but it doesn't disappear.

The Creative Debate: Performance vs. Craftsmanship

There's a philosophical tension lurking beneath the technical achievement here. In traditional animation, a character's motion is entirely the product of an animator's craft. Every movement is considered, intentional, shaped by the animator's artistic vision.

With exoskeleton capture, the motion is the product of an operator's physical performance, constrained by water physics and mechanical systems. It's more spontaneous, more emergent from physical constraints, less deliberately controlled.

Some animators argue this is a loss. They see animation as an art form where every pixel is intentional. They worry that relying on capture systems leads to less refined, less deliberately shaped movement.

Others argue it's an evolution. They note that capture-based approaches yield more realistic motion, more convincing physics, and movement that carries a kind of authenticity that pure animation can't replicate. They see it as expanding the toolkit available to filmmakers, not replacing the artistic tradition.

The reality is probably that both approaches have merit. For characters that should feel grounded in physical reality, exoskeleton capture is superior. For characters that exist in a more stylized or fantastical space, traditional animation remains the better choice.

Disney's decision wasn't to abandon animation entirely. It was to choose the right tool for a specific creative challenge. The Titans need to feel real, weighty, and present. Exoskeleton capture delivers that. Other characters in the Hercules universe, where stylization and theatrical movement are appropriate, can stick with traditional animation or standard motion capture.

The Environmental Cost: A Hidden Trade-off

Here's something rarely discussed: the environmental impact of underwater exoskeleton production facilities.

These tanks require enormous amounts of water. An 800,000-gallon tank needs to be filled, and that water needs to be maintained at specific temperatures and chemical balances. Maintaining water clarity for motion capture requires constant filtration and treatment. Over the course of a production, thousands of gallons of treated water might need to be drained and replaced.

The facility itself requires significant energy. Temperature control, lighting systems (which need to be powerful enough to properly illuminate motion capture markers underwater), air supply systems for operators—all of this is energy-intensive.

Disney, to its credit, has built these facilities with environmental considerations. Water is recycled through treatment systems rather than drained. Energy comes from renewable sources where possible. But there's still a notable environmental footprint.

This trade-off is rarely discussed because it's not visible to audiences. The technical achievement is celebrated while the environmental cost remains largely invisible. It's worth acknowledging as we consider whether this becomes industry standard.

The Hidden Performance: Why Nobody Talks About the Operators

There's something oddly invisible about the operators who bring these Titans to life.

They perform underwater for hours. They master complex mechanical systems. They translate emotional direction into physical movement in a way that requires both athletic ability and creative interpretation. They're essentially underwater stunt performers and actors combined.

Yet they receive no credits. Their names don't appear in the film. Audiences will never know they exist. They performed a role that's as creatively demanding as any on-screen performance, but entirely hidden.

This is similar to how stunt performers were long uncredited in films, but it's arguably more extreme. A stunt performer at least gets their body on screen, even if their face isn't shown. An exoskeleton operator is completely invisible—replaced by a digital character that gets all the recognition.

As this technology becomes more prevalent, there's a question about acknowledgment and credit. Should operators be credited? Should audiences know that these creatures are brought to life through human performance, even if that performance is hidden?

Disney's approach has been to keep it completely behind the scenes, not mentioned in marketing, not discussed in director interviews. But as more films use this technique, there's likely to be increasing discussion about transparency and credit.

The Future of Creature Animation: What Comes Next

Exoskeleton-based motion capture for large creatures is innovative, but it's also just one step in an evolution that's likely to accelerate.

AI-Enhanced Movement Refinement: Within 3-5 years, machine learning systems will likely be trained to recognize and enhance captured motion. Algorithms could suggest micro-adjustments to motion capture data that increase perceived weight and realism. An AI system trained on thousands of hours of real creature behavior could enhance captured motion in ways that push it beyond what human operators can achieve.

Hybrid Capture Systems: Future systems might combine exoskeleton capture with advanced soft-tissue simulation, muscle simulation, and cloth simulation. The skeleton motion comes from capture, but the organic movement of flesh, muscle, and fabric gets AI-enhanced simulation layered on top.

Real-Time Rendering on Set: As rendering technology improves, it might become possible to see near-final rendered creatures in real-time while still in the capture tank. Directors could adjust lighting, effects, and camera angles while the operator is still performing, rather than waiting days for the post-production pipeline.

Volumetric Capture: Beyond motion capture, volumetric capture systems could scan the entire 3D shape and volume of the exoskeleton in motion. This would eliminate the need for manual modeling and rigging of digital characters—the shape and volume would be derived directly from capture data.

Autonomous Exoskeleton Systems: Eventually, AI-driven systems might be able to operate exoskeletons based on high-level direction. A director says, "Walk forward with authority," and the AI system controls the exoskeleton to create physically realistic movement that matches that direction.

None of these are science fiction. They're logical extensions of technology that already exists, just not yet integrated into production workflows.

The Viewer Experience: Why You Should Know About This

Ultimately, the reason this matters is that it's changing what you're watching without you necessarily knowing it's happening.

The traditional assumption when watching a film is: if it's a creature on screen, it was either filmed practically (if it's an actor in costume or a physical creature) or it was created through animation or effects. That's the mental model most audiences operate with.

Exoskeleton-based capture exists in a strange middle space. It's not quite practical effects (no one is actually on screen), but it's not traditional animation either (movement isn't hand-crafted). It's captured motion from a physical system, then enhanced and rendered digitally.

Understanding this changes how you perceive the Titans. You're watching real movement, physics-based and constrained by water resistance, that's been enhanced and rendered. There's an authenticity to the motion that you might have sensed but couldn't quite explain.

It also raises questions about the nature of performance and creativity in cinema. Is the exoskeleton operator performing a role? Absolutely. Should they be credited as such? That's a legitimate question the industry is only beginning to grapple with.

Most importantly, it demonstrates that visual effects and animation are still evolving in unexpected directions. We tend to assume that the frontier of visual effects is in rendering technology or AI image generation, but sometimes the most profound innovation happens in how motion is captured and translated.

Disney's Hercules Titans are a testament to that principle: sometimes the best solution to a creative challenge comes from asking a completely different question. Instead of "how do we animate this better," Disney asked, "what if we don't animate it at all—what if we build it?"

The answer turned out to be more powerful than anyone probably expected.

FAQ

What exactly are exoskeleton motion capture rigs?

Exoskeleton motion capture rigs are full-scale mechanical frames that mirror human body proportions but scaled up to 15-20 feet tall. Operators sit inside or are mounted to these rigs and control their movement. The rigs operate underwater, where water resistance simulates the weight that the digital creature should feel. Multiple infrared cameras track the position of every joint on the exoskeleton, converting physical movement into digital motion data that can be applied to animated characters.

Why did Disney choose to use exoskeletons instead of traditional animation?

Disney chose exoskeletons because traditional animation struggles to convincingly convey weight and physical presence in large creatures. When movement is hand-animated, even photorealistic designs can feel weightless or floaty because the physics of motion are approximated rather than actual. Exoskeleton capture creates motion under real physical constraints (water resistance, gravity), which naturally conveys weight and presence that's nearly impossible to fake through animation. Additionally, exoskeleton production can be faster and more cost-effective than hand-animating complex creature sequences.

How does water resistance help with making creatures feel heavy?

Water resistance provides proportional resistance to movement based on velocity and surface area. When an exoskeleton operator moves the rig's arm through water, they feel actual resistance, which means they naturally make deliberate, slightly slower movements that convey weight. This resistance is proportional to the speed of movement, creating natural deceleration curves. The operator's physical movements, constrained by water physics, naturally translate into motion that reads as heavy when rendered digitally because the motion was physically constrained in the first place.

What's the difference between exoskeleton capture and traditional motion capture?

Traditional motion capture (like what's used for human actors) involves placing markers on a performer's body and recording their movement. Exoskeleton capture involves building a mechanical rig and recording the movement of the rig itself. The key difference is that exoskeleton systems are much larger, operate underwater for physics-based resistance, and produce movement that's inherently constrained by mechanical and physical limitations rather than human physiology. This produces different movement characteristics better suited for large, non-human creatures.

How long does it take to capture a Titan sequence?

Capturing a single Titan sequence (roughly 20-30 seconds of screen time) typically takes 8-12 hours of underwater work, which translates to 2-3 full operator shifts. However, this includes multiple takes, director reviews, and reshoots. Once captured, the motion data is locked and moves into post-production for enhancement and rendering. Total time from initial capture to final rendered sequence is typically 4-8 weeks, compared to 12-18 weeks for traditional hand animation of similar complexity.

Do the exoskeleton operators receive credit for their performance?

Currently, no. Exoskeleton operators are not credited in films, despite performing a role that's as creatively demanding as any on-screen actor. Their performance is completely hidden—they're essentially invisible performers whose work is entirely replaced by digital characters. This is an area of ongoing discussion in the VFX industry, with some advocating for operator credits to be included in final films, similar to how stunt performers are now increasingly credited.

What happens to the motion capture data after it's captured?

Motion capture data from the exoskeleton (essentially a skeleton moving through space at 120 frames per second) is imported into animation software. From there, animators refine the timing, adjust movement magnitude, add secondary motion like hair and clothing, animate facial expressions separately, and layer on visual effects like fire, ice, or other creature-specific effects. The captured motion serves as the foundation, but significant artistic refinement happens in post-production before the final rendered creature appears on screen.

Could this technique be used for other types of characters?

Exoskeleton capture is specifically well-suited for large, physical creatures where weight and presence are important to the character's emotional impact. It's less ideal for stylized characters, cartoony designs, or creatures that need to move in ways that defy real-world physics. For those character types, traditional animation remains the better choice. Exoskeleton capture is a tool in the toolkit, not a replacement for all animation.

What's the approximate cost of building an exoskeleton motion capture facility?

Building a facility capable of underwater exoskeleton capture requires an investment in the range of $15-50 million depending on tank size, equipment sophistication, and technical infrastructure. This is why only major studios like Disney have built these facilities. The cost is justified because it's amortized across multiple productions and reduces per-frame production costs through faster timeline and reduced animation labor.

Are there environmental concerns with underwater capture facilities?

Yes. These facilities consume enormous amounts of water, require significant energy for temperature control and lighting, and produce treated wastewater. Disney has addressed these concerns through water recycling systems, renewable energy use, and efficient equipment selection. However, there's still a notable environmental footprint that's rarely discussed in industry discourse. As the technique becomes more prevalent, environmental impact will likely become a more significant consideration in facility design and operation.

Conclusion: The Invisible Performance That Changed Everything

When you watch Disney's Hercules, you're experiencing something remarkable that exists almost entirely hidden from view. The Titans that tower across the screen move with a physicality that feels real because it is real—movement captured from mechanical systems operating under actual physical constraints, then enhanced and rendered into mythological creatures.

It's a technique that required Disney to ask a completely unconventional question: what if instead of animating weight, we actually capture it? What if instead of hand-crafting motion, we let physics do the heavy lifting?

The answer has profound implications. It demonstrates that the frontier of visual effects isn't always in rendering technology or algorithmic sophistication. Sometimes it's in fundamentally reconsidering how a problem should be approached.

The hidden exoskeleton operators who brought these Titans to life performed as genuinely as any actor on screen, yet they'll never be credited, never be recognized, never have their contribution acknowledged to audiences. There's something poignant about that invisibility—a performance that's so successful, so convincingly integrated into the final product, that nobody even realizes it's there.

As this technology spreads throughout the industry—and it absolutely will—it represents a shift in how we create visual narratives. Animation isn't disappearing. But how we animate, what we choose to capture versus craft, and what role physics-based systems play in storytelling is evolving in ways we're only beginning to understand.

The next time you watch a creature on screen that feels undeniably present, undeniably weighty, undeniably real, consider the possibility that beneath layers of digital rendering and visual effects, there's a human performer in a water tank, moving a massive mechanical exoskeleton, and bringing that creature to life through invisible performance.

That's the future of animation. And it's already here.

Key Takeaways

- Disney replaced traditional animation of the Hercules Titans with underwater exoskeleton motion capture technology, capturing real movement data instead of hand-animating

- Water resistance in underwater tanks creates natural physics-based constraints that make captured movement feel genuinely heavy, solving animation's fundamental weight problem

- Exoskeleton operators are skilled performers who physically control 15-ton mechanical rigs while submerged, their movements translated into digital characters through motion capture

- The production pipeline combines capture data with layered post-production enhancement including facial animation, effects, and physics refinement—taking 4-6 weeks versus 12-18 weeks for traditional animation

- This technology represents the future of creature animation for large, physically imposing characters where conveying weight and presence is essential to storytelling

Related Articles

- Acemagic Tank M1A Pro+ Ryzen AI Max+ 395 Mini PC [2025]

- Watch Australia vs England 4th Ashes Test: Free Streams & Viewing Guide 2025

- Why Budget Laptops Fail: Real Costs of Cheap Computers [2025]

- Amazon After-Christmas Sale 2025: Best Deals on Tech, Home & More

- YouTube Premium Needs These 5 Critical Upgrades in 2026

- Best Budget Nintendo Switch Picross Games: Your Family Holiday Escape [2025]

![How Disney Engineered Hercules' Titans with Hidden Exoskeleton Tech [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-disney-engineered-hercules-titans-with-hidden-exoskeleto/image-1-1766705728755.jpg)