How Iranians Are Bypassing Internet Censorship: A Complete Guide to Digital Resistance [2025]

When Iran's internet went dark on January 8th, the country didn't just lose connectivity. It lost a lifeline.

Thousands of Iranians found themselves cut off from the outside world. No news. No social media. No way to tell loved ones they were safe. For over a week, the nation experienced what experts call one of the most severe internet blackouts in modern history. According to Chatham House, this blackout marked a new stage in digital isolation.

But here's the thing: Iranians didn't stay silent. They fought back.

What started as a desperate scramble to reconnect turned into a sophisticated digital resistance movement. Using VPNs, proxy servers, mesh networks, and encrypted communication apps, ordinary people began circumventing the world's most advanced censorship infrastructure. Activists, students, journalists, and parents all found ways to stay connected when the regime wanted them isolated, as highlighted by News.az.

The Iranian government isn't just blocking websites anymore. They're deploying advanced filtering technology, throttling bandwidth, and targeting VPN users with legal threats and surveillance. It's a cat-and-mouse game where the stakes are real: arrest, torture, even death. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reports on the cooperation between Iran and China in deploying such technologies.

Yet the resistance persists. Because as one Iranian activist told researchers: "Iranians are resilient. They always find ways to speak."

This isn't just about internet access. It's about survival, freedom of expression, and human rights in an age where governments have weaponized connectivity itself. Understanding how Iranians bypass censorship reveals critical insights about digital freedom, privacy technology, and the future of internet governance worldwide.

Let's break down exactly what's happening, why it matters, and what tools are actually working on the ground.

TL; DR

- Iran deployed one of the world's most sophisticated censorship systems, blocking VPNs, throttling internet speeds, and arresting users caught bypassing restrictions, as detailed by Chatham House.

- VPNs remain the most popular choice, with Express VPN, Mullvad, and Psiphon gaining adoption despite government blocking attempts, according to CyberNews.

- Mesh networks and peer-to-peer tools like Briar and Bridgefy enable offline-first communication when centralized infrastructure fails.

- Encrypted messaging apps including Signal, Wire, and Telegram (with security settings) provide covert channels for activists and journalists.

- Technical circumvention is escalating, with users employing DNS tunneling, IP obfuscation, and protocol morphing to stay ahead of censors.

- The human cost is real: Iranians using these tools risk legal prosecution, surveillance, and physical harm, as reported by Iran International.

- International support matters: Organizations like the Tor Project and Freedom of the Press Foundation are providing resources, but grassroots innovation is the real game-changer.

Estimated data shows that forensic analysis and device seizure are among the top risks faced by activists, each accounting for about 20-25% of the overall risk. The psychological toll is equally significant.

The Severity of Iran's Internet Crisis: What Actually Happened

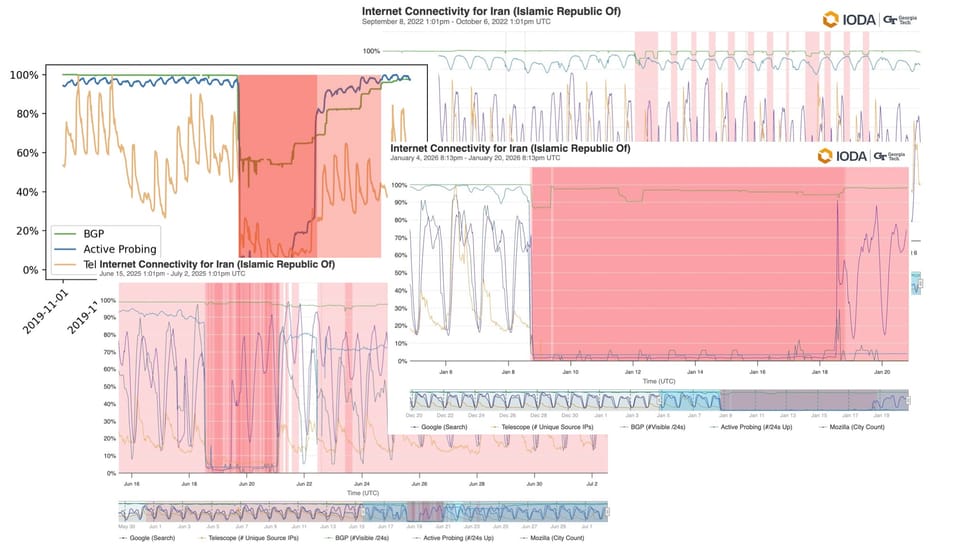

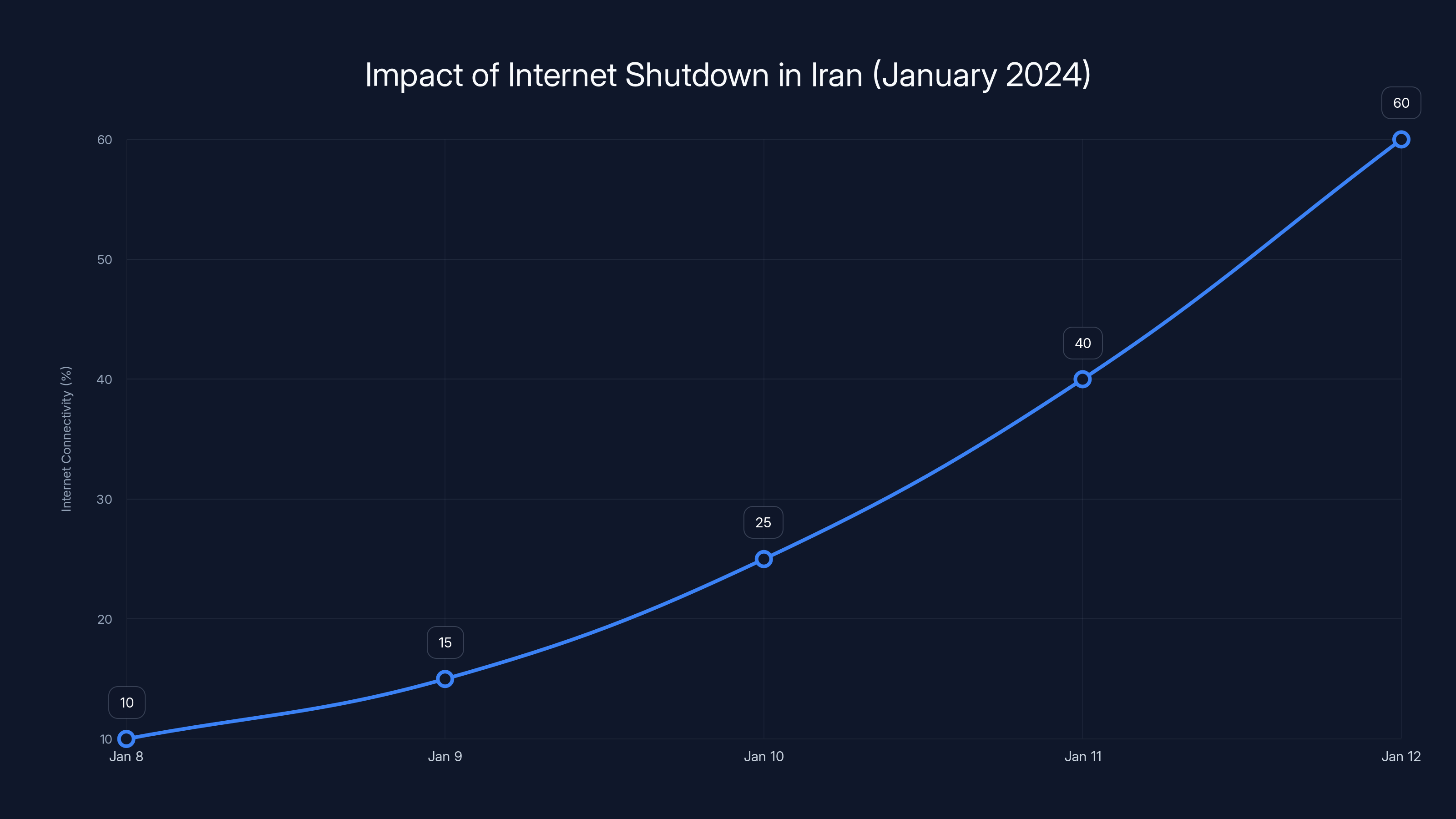

Let's be clear about what happened in January 2024. This wasn't a technical glitch or a routine maintenance window. This was a deliberate, nationwide internet shutdown orchestrated by the Iranian government in response to civil unrest, as noted by The Bulletin.

On the morning of January 8th, internet access collapsed across the country. Within hours, connectivity dropped by over 90% in major cities. Mobile networks went offline. VPN connections that worked the night before suddenly failed. Social media platforms became unreachable. News sites vanished. Iranians couldn't access WhatsApp, Instagram, or Telegram.

For the first time in years, large portions of Iran were completely disconnected from the global internet.

The government claimed it was a temporary measure for "security reasons." But families couldn't reach each other. Businesses couldn't operate. Students couldn't attend online classes. Hospitals struggled to access medical records stored in the cloud.

When connections slowly returned days later, something fundamental had changed. The internet never fully recovered. Speeds remained throttled. Certain websites stayed blocked. VPN usage became aggressively detected and targeted. The government announced new laws making VPN use a criminal offense punishable by fines and imprisonment.

What made this different from previous Iranian internet controls wasn't just the scale. It was the sophistication. The regime was using technology that rivals some of the most advanced surveillance states in the world.

The blocking infrastructure uses sophisticated techniques including:

- Deep Packet Inspection (DPI): Technology that examines the contents of data packets traveling through the internet, allowing authorities to identify and block VPN traffic and encrypted communications

- IP-based filtering: Blocking access to known VPN server IP addresses in real time as new servers come online

- DNS manipulation: Intercepting domain name requests and returning false addresses to prevent access to blocked websites

- Bandwidth throttling: Intentionally slowing down connections to certain services, making them unusable

- Protocol blocking: Identifying and blocking specific communication protocols used by VPNs and encrypted messaging apps

China and Russia have similar systems. But Iran's censorship apparatus is uniquely aggressive because it combines advanced filtering technology with legal penalties, surveillance, and real-world enforcement.

The chart illustrates the drastic drop and gradual recovery of internet connectivity in Iran during the January 2024 shutdown, highlighting a significant initial collapse to 10% connectivity.

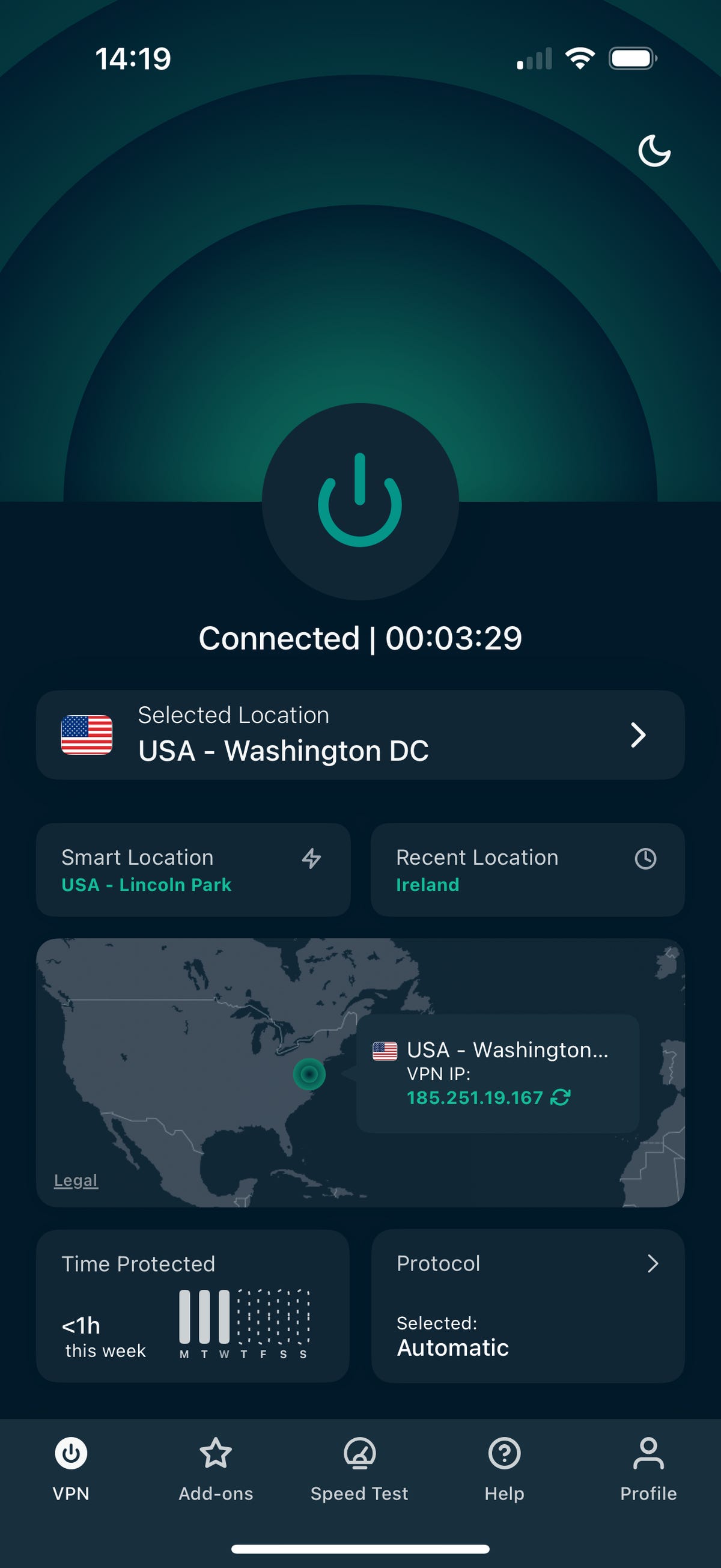

Why VPNs Became the First Line of Defense

When the internet came back online, the first thing Iranians did was search for VPNs. It made sense. VPNs are the most mainstream privacy tool available. They're easy to download. They're legal in most countries. And they work by routing traffic through servers outside Iran, theoretically hiding what you're accessing from the government.

For about two weeks, VPNs worked. Then the government adapted.

Iranian authorities began using advanced traffic analysis to detect VPN usage. They didn't need to know exactly what you were doing online. They just needed to know you were using a VPN, which itself became illegal. News outlets reported thousands of warning messages sent to suspected VPN users, followed by fines and legal threats.

But Iranians didn't give up on VPNs. They evolved how they used them.

Instead of running VPNs continuously, power users switched to using them only for specific tasks: accessing news sites, uploading photos to social media, or checking email. Between uses, they'd disconnect to avoid detection during normal browsing patterns.

Others started using VPN obfuscation tools that disguise VPN traffic as regular HTTPS web traffic. From the government's perspective, it looks like someone is browsing a normal website. But underneath, the connection is being routed through a VPN server abroad.

Popular VPNs being used include:

- Express VPN: Known for strong encryption and obfuscation features, though the company announced it had no choice but to remove servers from Iran

- Mullvad: A privacy-focused VPN with a no-logging policy and support for obfuscation protocols

- Psiphon: Specifically designed for censorship circumvention, offering a lighter-weight application that works on older devices

- IVPN: Another privacy-first VPN with built-in obfuscation and support for multiple protocols

- TOR: While technically not a VPN, the Tor network uses the same principle of routing traffic through multiple servers

The problem is that VPN companies are profit-driven businesses. When governments demand compliance or threaten legal action, many corporate VPN providers comply. Some have backdoors built into their systems. Others log user activity and turn it over to authorities when requested.

This is where the limitations become obvious. VPNs alone aren't sufficient for the most vulnerable activists. They're a first line of defense, but not a complete solution.

The Rise of Mesh Networks: Communication Without Infrastructure

The real innovation came from a different direction entirely. When traditional internet infrastructure becomes unreliable or monitored, mesh networks offer a fundamentally different approach.

A mesh network doesn't depend on cell towers or internet service providers. Instead, devices connect directly to each other, creating a web of interconnected nodes. Messages hop from device to device, finding their own route through the network. If one device goes offline, the message finds another path.

Think of it like a human relay system, but digital. You hand a message to a friend, who passes it to another friend, who passes it to another friend, until it reaches its destination. The government can't monitor it because there's no central infrastructure to tap into.

During Iran's internet blackout, this approach became crucial. Iranians installed mesh networking apps like Briar and Bridgefy to maintain communication when the internet was completely unavailable.

Briar specifically was designed for exactly this scenario: political activism in contexts where internet connectivity is unreliable or controlled by hostile governments. The app runs on Android and uses Bluetooth to connect nearby devices. Messages are encrypted end-to-end, so even if they're relayed through strangers' phones, the content remains private.

A teenager could send a message through the Briar network, and it could reach an activist across the city by hopping through dozens of intermediary devices. Each hop is encrypted, so nobody (not even the devices relaying the message) can read the content.

Bridgefy works similarly but focuses on smartphone-to-smartphone messaging using Bluetooth and Wi-Fi Direct. It doesn't require internet connectivity at all.

The advantages are obvious:

- No central infrastructure to attack: The government can't shut it down because there's no "off" switch

- Decentralized: No single company controlling it or able to comply with government requests

- Works offline: You don't need internet access. Just other people with the app installed nearby

- Resilient: If routes are blocked, messages find alternative paths automatically

But mesh networks have real limitations too. They're slow. You can't send high-bandwidth content like video. The range depends on how many people are running the app and how close together they are. In rural areas, they're nearly useless. And they require critical mass: the network only becomes useful when thousands of people are using it.

During the January blackout, mesh networks proved their value for short-term survival communication. But they're not a replacement for internet-based tools for long-term digital life.

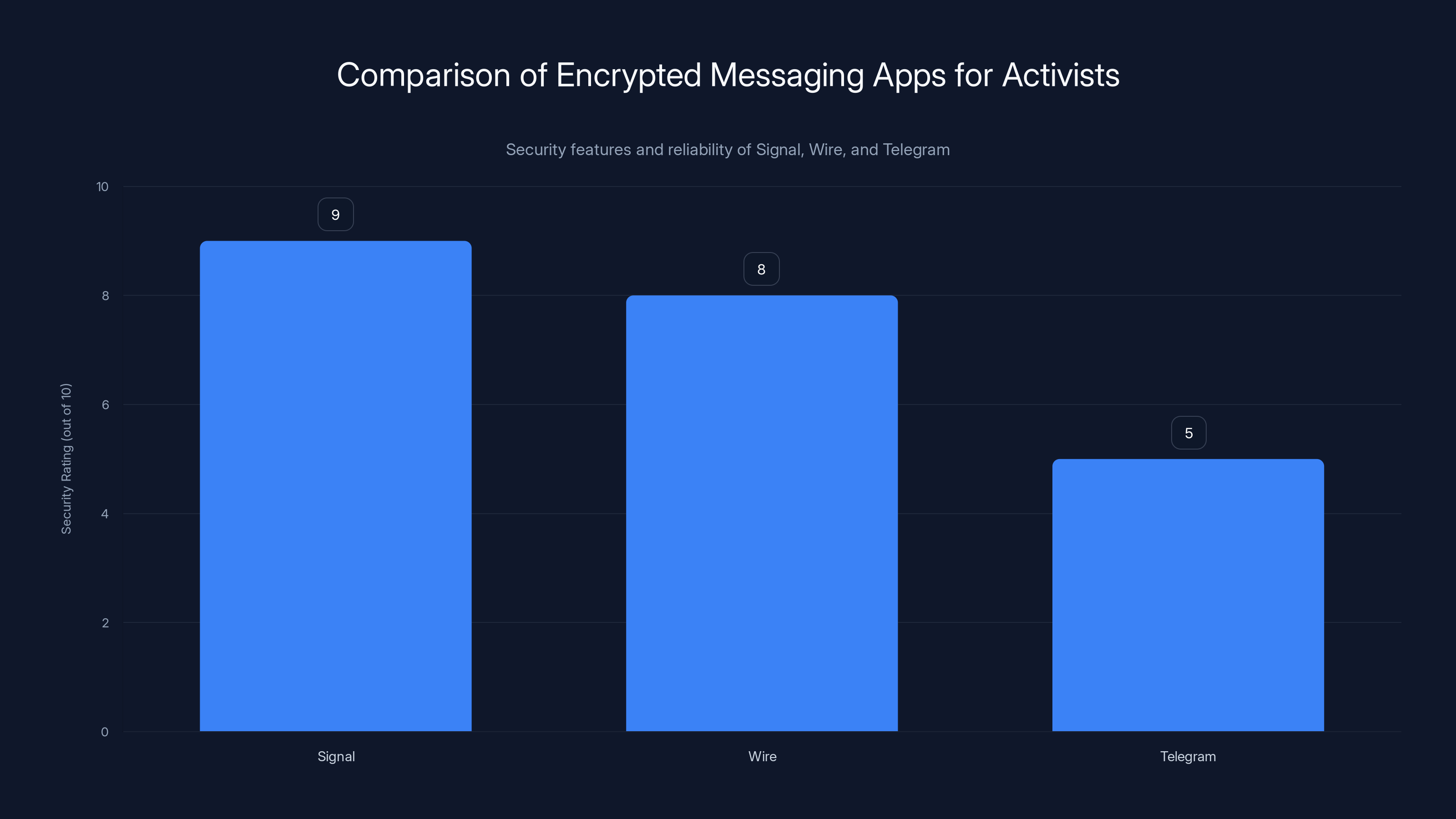

Signal is rated highest for security with a score of 9, followed by Wire at 8. Telegram scores lower at 5 due to weaker encryption and compliance issues. Estimated data based on security features.

Encrypted Messaging: The Activist's Hidden Channel

Journalists and human rights activists operating in Iran can't rely on traditional communication methods. A phone call might be intercepted. An email could be monitored. Even encrypted email can be problematic because metadata (who you're talking to, when, and how frequently) reveals patterns that are dangerous.

This is where encrypted messaging apps become essential infrastructure.

Signal is the gold standard. It's an end-to-end encrypted messaging app that's been independently audited and recommended by security experts worldwide. Every message is encrypted on your device before it leaves, and only the recipient can decrypt it. Signal doesn't store messages on servers, so even if the government seizes Signal's servers, they can't read old conversations.

The critical feature is perfect forward secrecy: even if an attacker somehow compromises your encryption key, they can only read future messages, not past ones. Each conversation uses a unique key that automatically rotates.

Wire is another strong option. It's also end-to-end encrypted and offers additional features like group messaging with strong security guarantees and self-destructing messages.

Telegram is complicated. Many Iranians use it because it's convenient and widely available, but Telegram's security is weaker than Signal. Regular Telegram chats use server-side encryption, meaning Telegram itself can technically decrypt them. Secret chats use end-to-end encryption, but they're less convenient (you have to manually enable them), and some features don't work.

Worse, Telegram's founder has a history of complying with government requests. In Russia, he's faced intense pressure. In countries like Uzbekistan, Telegram simply works as normal because the government doesn't pressure Telegram as aggressively.

But in Iran, the government is actively targeting Telegram users. They've created fake Telegram bots designed to trick users into clicking malicious links. They've threatened to block Telegram entirely. They've arrested activists based on evidence extracted from Telegram conversations.

For Iranian activists, the best practice is:

- Use Signal for sensitive conversations where you need maximum security

- Use Wire as a backup when Signal is blocked

- Use encrypted email like Proton Mail for longer-form communication

- Avoid Telegram for anything sensitive, even though many people use it for casual communication

- Never assume any platform is truly safe from government surveillance

The problem with all messaging apps is that encryption is only one part of security. If your device is already compromised by malware, your conversations can still be read. If you use weak passwords, your account can be hacked. If you enable backups to iCloud or Google Drive, encrypted messages get backed up in plaintext (readable) format.

Activists in Iran are learning this the hard way. Some have been arrested despite using Signal, because their entire device was compromised by spyware. Others were caught because they used the same password across multiple services, and one service was breached.

DNS Tunneling and Protocol Obfuscation: Technical Circumvention

As the Iranian government's blocking techniques became more sophisticated, technically advanced users started deploying increasingly clever workarounds. These aren't tools for casual internet users. They're for people who understand how networks work and are willing to invest time in configuration.

DNS tunneling is one of the most creative approaches. DNS (Domain Name System) is the service that translates domain names like "google.com" into IP addresses like "142.251.41.14". It's fundamental to how the internet works.

DNS requests are usually unencrypted, which means the Iranian government can easily see which websites people are trying to access. But DNS tunneling encodes data inside DNS requests. A user can connect to a free DNS service outside Iran, and that service acts as a proxy.

To the government's surveillance system, it looks like normal DNS activity. But the user is actually accessing blocked websites through an encrypted tunnel.

The challenge is that DNS tunneling is slow and only suitable for text-based content. You can't stream video through DNS tunneling. But for accessing news sites or sending messages, it works.

Protocol morphing is even more sophisticated. It takes encrypted traffic and modifies it to look like normal, unblocked traffic. For example, it might make a VPN connection look like regular HTTPS web traffic by disguising the packet structure.

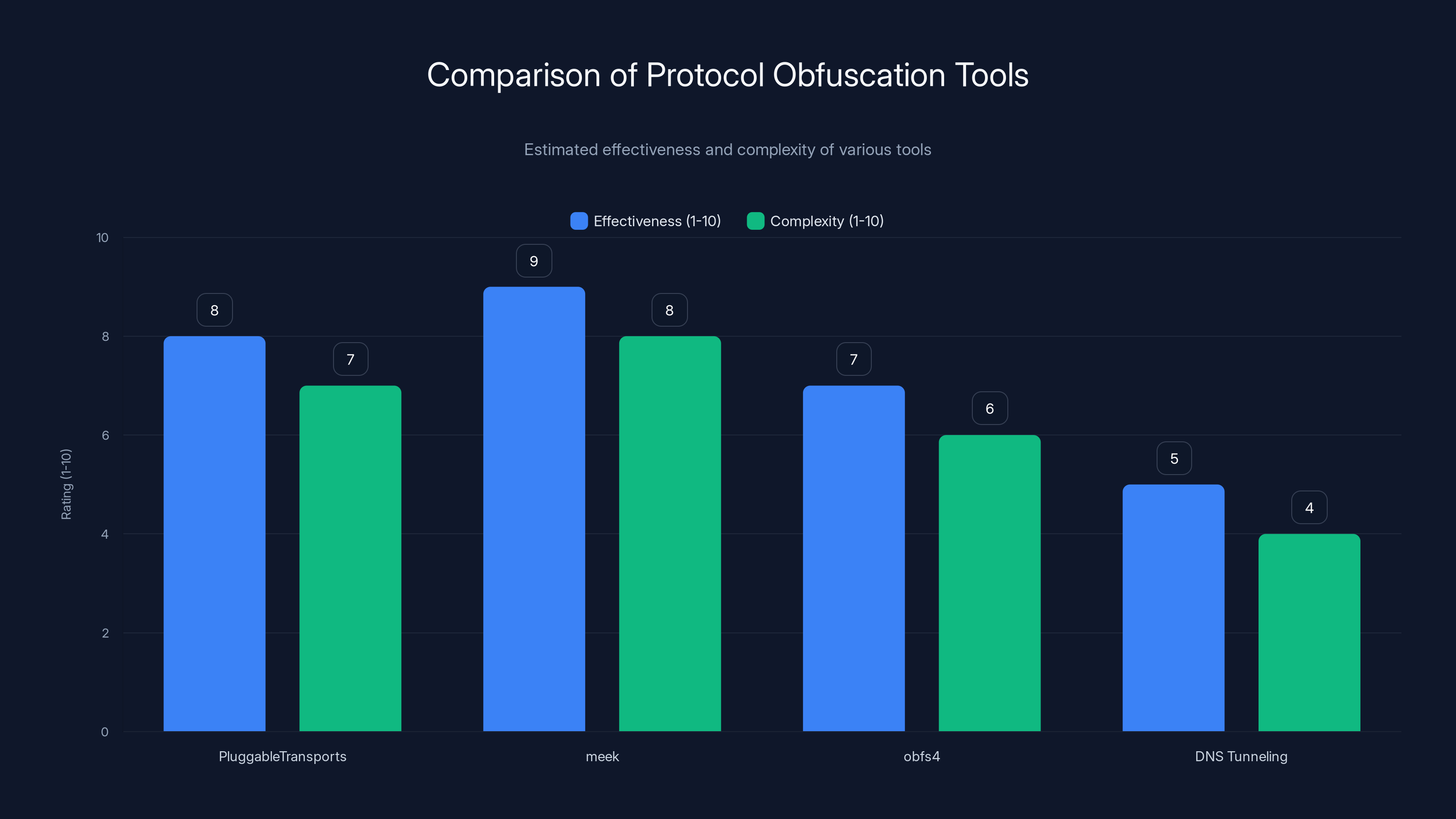

Several tools use this approach:

- Pluggable Transports: A framework that lets you disguise Tor traffic as normal web traffic

- meek: A tool that makes Tor look like traffic to a major content delivery network (CDN), so the government can't block it without blocking all web traffic

- obfs 4: A transport that obfuscates traffic to make it harder to identify and block

These tools work because the Iranian government doesn't want to block all encrypted traffic indiscriminately. That would break legitimate businesses, banking systems, and government services that depend on encryption.

So instead, they target specific signatures of VPN and Tor traffic. Protocol obfuscation changes those signatures, making the traffic blend into normal internet activity.

The limitation is that these approaches are cat-and-mouse games. For every new obfuscation technique, the government develops new ways to detect and block it. Users who understand this technology can stay ahead, but it requires constant adaptation and technical knowledge.

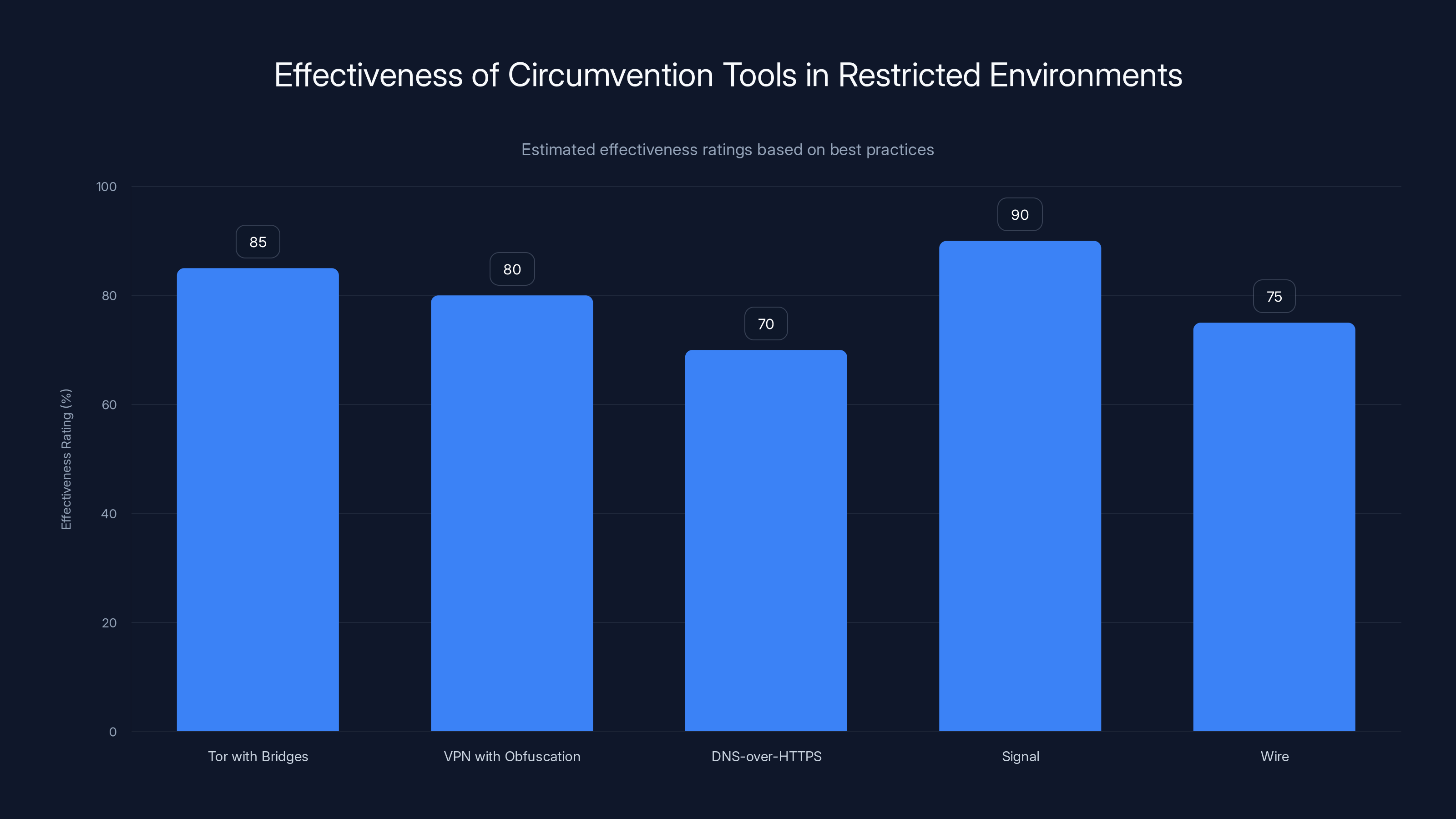

Estimated data shows Tor with bridges and Signal as the most effective tools for circumventing restrictions and ensuring secure communication.

Tor: The Network Built for Resistance

If VPNs are security blankets, Tor is a full-body armor suit. Tor is a volunteer-run network of computers that relay internet traffic multiple times, making it nearly impossible to trace the source.

When you use Tor, your request bounces through at least three randomly selected computers (called "relays") before reaching its destination. Each relay decrypts one layer of encryption, revealing only the next relay's address, not the original source or final destination.

It's like sending a letter through multiple postal workers, each one knowing only the next address but not where it came from or where it's ultimately going.

Tor was originally developed by the U. S. Naval Research Laboratory and released to the public for exactly this reason: to help people in countries with severe censorship maintain privacy and access information.

In Iran, Tor is illegal. Using Tor can result in arrest and prosecution. But Tor is also the hardest technology to block. The Iranian government can't simply block Tor IP addresses because Tor relays keep changing. They can't force Tor to backdoor itself because Tor's code is open-source and maintained by volunteers worldwide.

What Iran has done is use advanced traffic analysis to detect Tor users. They watch for the distinctive pattern of Tor connections and slow them down or disconnect them. But detection isn't absolute, especially if users employ additional obfuscation.

Tor Bridges are a key innovation here. Most people connect to Tor by requesting a list of relay addresses from Tor's directory servers. The Iranian government watches these directory servers and knows which addresses are Tor relays.

Bridges are unlisted Tor relays that aren't in the public directory. Instead of asking Tor's directory servers for a bridge address, you have to know one already. You might get it from a friend, or from the Tor Project's bridge distribution service.

To the government's surveillance system, a Tor Bridge connection just looks like a normal HTTPS connection to a random server. It's only once you're connected that you're routed through the Tor network.

Many Iranian activists are using Tor with bridges because it's one of the few tools that the government hasn't been able to completely shut down.

The tradeoff is speed. Tor is slow. Websites load slowly. Videos are nearly unwatchable. But for activities where privacy is more important than speed (accessing news sites, communicating with journalists, organizing activism), Tor is worth the inconvenience.

Decentralized Social Media and Alternative Platforms

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube are all blocked in Iran. The government can't control them, so it shuts them down entirely.

For a long time, this created a media vacuum. Iranians couldn't share news, photos, or connect with a broad audience without using government-controlled media.

That's changing with decentralized social media platforms. These aren't operated by companies. They're run on distributed networks where no single entity can shut them down.

Mastodon is a decentralized alternative to Twitter. Instead of posting on a central server, you join a specific Mastodon "instance" (server). Each instance is independent but can communicate with other instances. If the Iranian government blocks one instance, you can switch to another.

The key difference from Twitter is that no company is in control. Mastodon is open-source software that anyone can run on their own server. This makes it nearly impossible to fully block.

Pixelfed is similar but for image sharing (think Instagram alternative). PeerTube is a YouTube alternative. These all follow the same model: decentralized networks that can't be shut down by controlling a single company.

The challenge is that these platforms are less convenient than their centralized alternatives. They have smaller user bases. Discovery is harder. The user experience is rougher.

But for journalists, activists, and people who want to share information without government control, decentralized platforms are becoming more viable every month.

Another approach gaining traction is InterPlanetary File System (IPFS). Instead of websites being hosted on a central server, files are distributed across a peer-to-peer network. Anyone can access the file from whoever in the network has a copy.

Iranian news organizations have started publishing content on IPFS specifically because it can't be blocked. The government would have to block the entire IPFS network globally, which is essentially impossible.

These approaches represent a fundamental shift: moving from client-server architecture (where a company controls the server) to peer-to-peer architecture (where the network itself is the platform).

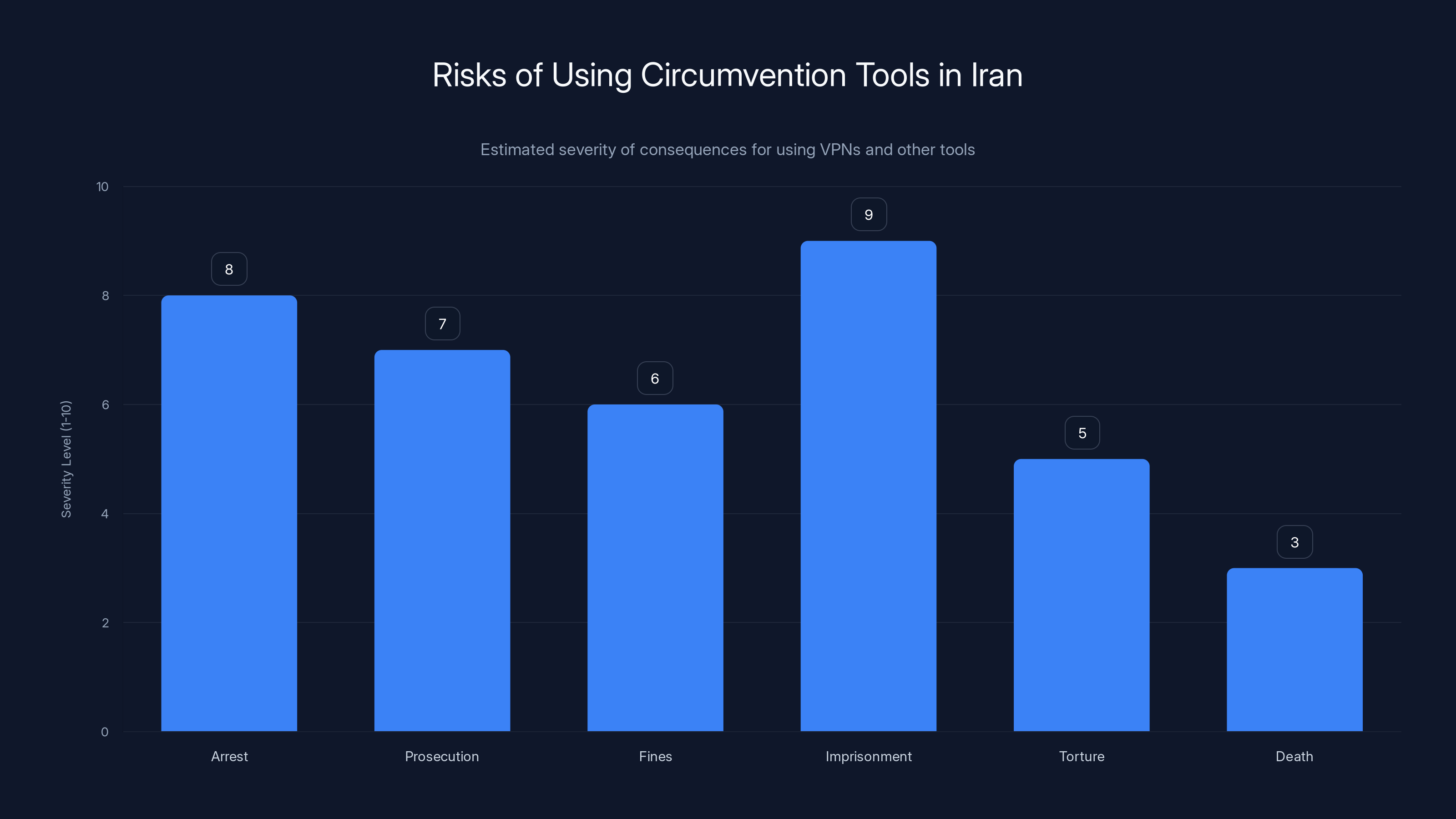

Using circumvention tools in Iran carries severe risks, with imprisonment and arrest being the most severe consequences. (Estimated data)

The Role of International Support and Organizations

Iranians aren't fighting censorship alone. International organizations are providing crucial support.

The Tor Project maintains and develops Tor, specifically with countries like Iran in mind. The project's director has been explicit that circumventing censorship is a core mission. When Tor detects that it's being blocked in a country, developers work on new obfuscation methods and improved bridges.

The Freedom of the Press Foundation provides training and resources for journalists in countries with severe censorship. They distribute encrypted communication tools, maintain documentation on how to stay safe, and provide financial support to activists who face legal threats.

Access Now monitors digital rights violations and provides emergency assistance to people facing online or offline threats. They've documented Iranian government surveillance and helped activists access protective resources.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have published reports specifically about internet censorship in Iran, raising international awareness and pressure. Small Media Foundation conducts research on how technologies are being used for censorship and creates educational materials for circumvention.

These organizations can't stop the Iranian government. But they can:

- Maintain and improve circumvention tools so they stay ahead of blocking techniques

- Provide training to activists and journalists on how to use tools safely

- Document violations so there's an international record

- Raise awareness so the world knows what's happening

- Provide financial support to activists facing legal consequences

- Develop better tools specifically designed for the most restrictive environments

But here's the honest assessment: international organizations are playing defense. They're trying to help people circumvent censorship that's already in place. They're not powerful enough to change the fundamental dynamics.

The real change will come from Iranians themselves. From activists who are willing to take risks. From developers who are building better tools. From ordinary people who refuse to accept censorship.

Arrest, Surveillance, and the Human Cost

This is where the conversation needs to get serious. Using circumvention tools in Iran isn't just technically risky. It's physically dangerous.

The Iranian government has arrested hundreds of people for "cybercrimes" including VPN usage, running Telegram bots, and accessing blocked websites. These arrests have led to torture in detention, forced confessions, lengthy prison sentences, and in some cases, execution.

One documented case involved a cybersecurity researcher who was arrested for "espionage" partly based on evidence that he had used encryption tools. He was held in solitary confinement for months before being released.

Activists using these tools have to assume:

- Their device will be seized at some point, possibly by force

- Forensic analysis will reveal their circumvention activity

- The prosecution will use this against them as evidence of illegal activity

- Other conversations or activities will be discovered during forensic examination

- Their arrest might endanger people they communicate with if their device contains their contacts

This creates impossible tradeoffs. If you use circumvention tools, you risk arrest. If you don't, you can't access information or communicate freely.

Many Iranian activists solve this by using separate devices. They might have:

- A personal phone for everyday use

- A laptop used only for activism, which they might destroy or hide if they sense danger

- Communication with other activists only through specific encrypted channels

- No personal information on devices used for circumvention

But even this isn't failsafe. Police can arrest you, seize all your devices, and interrogate you for days. Forensic experts can sometimes recover deleted data.

The psychological toll is immense. Activists report constant fear. They sleep with encrypted phones hidden. They check for surveillance before going out. They can't trust anyone completely.

Yet they continue. Because the alternative—living under total censorship and surveillance—is worse.

Estimated data shows 'meek' as the most effective tool for protocol obfuscation, while DNS tunneling is less effective but simpler to implement.

What's Actually Working Right Now

After months of experimentation and adaptation, Iranian users have discovered which approaches are most reliable.

VPNs are still being used, but less as a primary tool and more as one component of a broader strategy. Users who are still successfully accessing blocked content are typically:

- Using Tor with bridges for maximum privacy and difficulty to block

- Using DNS over HTTPS (DoH) to encrypt DNS requests and prevent the government from seeing which sites they're trying to access

- Using Signal for sensitive communications instead of Telegram

- Using decentralized alternatives when possible to avoid platform-specific blocking

- Manually configuring tools rather than using automatic/default settings that authorities might have reverse-engineered

Mesh networking apps like Briar are still installed on many devices but are used less now that the internet has partially recovered. However, they're seen as a backup if conditions deteriorate again.

Which tools have been most successfully blocked?

- Most major commercial VPN apps have been made difficult to use (though technical users can still get them working)

- Telegram has been intermittently throttled and blocked, forcing users to more secure alternatives

- Shadowsocks (a proxy protocol) was heavily targeted and is now mainly used by experienced technologists

- Some protocol obfuscation tools have become blocked as the government learns their signatures

The landscape is fluid. New blocks appear constantly. New circumvention techniques are deployed. The technical arms race never stops.

The Broader Implications for Digital Freedom Worldwide

What's happening in Iran isn't unique. It's a preview of what other authoritarian regimes are working toward.

China has the Great Firewall, which is arguably more sophisticated than Iran's system. Russia has been steadily increasing internet control. Vietnam is developing censorship infrastructure. Even democracies like Australia and the UK have been debating internet regulation laws that could enable censorship.

The Iranian case is important because it shows both what's possible with current technology and the limits of that technology.

The government can block most casual circumvention attempts. They can make internet access frustrating and slow. They can arrest and prosecute people suspected of using circumvention tools.

But they can't block everything. Decentralized networks, open-source tools, and volunteer-maintained projects like Tor are fundamentally harder to control than centralized platforms.

This suggests some important principles:

- Decentralization is more resilient than centralization: Systems with no central point of control are much harder to shut down

- Open-source is more robust than proprietary: When code is public, security issues are spotted faster, and tools can be forked and modified

- Volunteer-run projects are more committed than commercial ones: Companies can be forced to comply; volunteers are driven by ideology

- Encryption is borderline impossible to break: If cryptography is done right, surveillance is nearly impossible, even with government-level resources

- But technology alone isn't enough: Technical tools only work if people use them correctly, and the human element is always the weakest link

For governments wanting to maintain freedom of expression and privacy for their citizens, these principles suggest a different model than what we see in most democracies today. Instead of trying to regulate or control digital services, governments should:

- Support open-source tools that nobody controls

- Protect decentralized protocols from regulation

- Allow and encourage encryption rather than demanding backdoors

- Make it easy for people to understand and use security tools

For people in countries with censorship, the message is that technical resistance is possible, but it requires understanding how these tools work and constantly adapting.

Best Practices for Circumvention in Restricted Environments

If you're living in a country with severe internet restrictions and need to access information or communicate securely, here are evidence-based practices that are actually working:

For accessing blocked websites:

- Start with Tor using bridges (not the standard Tor network)

- If Tor is blocked, try a VPN with obfuscation enabled

- If VPNs fail, try DNS-over-HTTPS services like Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1

- Keep multiple tools installed so you have backups when one is blocked

- Never rely on a single tool

For secure communication:

- Use Signal for all sensitive conversations (not Telegram)

- Use Wire as a backup if Signal becomes unavailable

- Enable disappearing messages on all tools if available

- Never assume any platform is safe from government surveillance

- Verify contacts through out-of-band methods (meeting in person, calling from a known phone number) before trusting them

For protecting your device:

- Use strong, unique passwords for every account

- Enable two-factor authentication everywhere

- Keep your operating system and apps updated to patch security vulnerabilities

- Consider using a separate device for sensitive activities

- Assume your device might be compromised and act accordingly

For operational security:

- Use Tor Browser for anonymous web browsing rather than installing VPN software (less detectable)

- Connect through Tor before using email or messaging to prevent metadata from being logged

- Rotate your tools regularly to avoid patterns that authorities might recognize

- Never tell people you're using circumvention tools unless absolutely necessary

- Monitor news about new blocking techniques and adapt your approach

These practices come from actual activists in Iran and other restricted environments who are successfully maintaining communication and accessing information. They're not theoretical. They work, but they require discipline and constant adaptation.

The Future of Censorship and Resistance

Where is this heading? What should we expect in the next few years?

On the government side, expect:

- More sophisticated AI-powered detection that can identify circumvention tools even when they're obfuscated

- Deeper integration of surveillance into network infrastructure making it harder to avoid without detection

- Stronger legal penalties to deter people from even attempting to use circumvention tools

- Pressure on international companies to comply with censorship demands or face market access restrictions

- Export of censorship technology to other authoritarian regimes

On the resistance side, expect:

- More decentralized tools that distribute data across peer-to-peer networks

- Better integration of multiple circumvention methods so users don't have to manually switch between tools

- Improved offline-first technologies that work without internet connectivity

- Wider adoption of end-to-end encryption as the default, not the exception

- More grassroots innovation from communities directly experiencing censorship

The long-term trajectory is uncertain. But what's clear is that this is a fundamental tension in the digital age.

Governments want control. They want to monitor communications, prevent dissent, and enforce ideological conformity. Technology makes this more possible than ever. But technology also makes resistance possible. Encryption, decentralization, and cryptography are mathematically grounded. They're hard to break without getting the underlying math wrong.

The battle between censorship and freedom isn't going to be won by better algorithms. It's going to be won by people who refuse to accept censorship, who build tools, who take risks, and who persist despite consequences.

Iranians have shown that they're willing to do this. Despite the danger, despite the difficulty, they're finding ways to speak.

That resilience is ultimately more powerful than any technology the government can deploy.

FAQ

What is internet censorship in Iran?

Internet censorship in Iran refers to the government's systematic blocking and monitoring of online content. The regime controls major portions of the country's internet infrastructure and actively blocks access to websites, social media platforms, messaging apps, and VPN services. This isn't just filtering: it's backed by law, surveillance technology, and enforcement through arrests and prosecution of users.

How do VPNs help in restricted internet environments?

VPNs route your internet traffic through a server outside the country, hiding your real IP address and encrypting your connection. This makes it difficult (but not impossible) for the government to see which websites you're accessing or what you're communicating. However, VPNs alone are no longer sufficient in Iran because the government can now detect and block VPN traffic using advanced packet inspection technology.

What are the risks of using circumvention tools in Iran?

The risks are severe and real. Using VPNs, Tor, or other circumvention tools is illegal in Iran and can result in arrest, prosecution, fines, imprisonment, torture, and potentially death. The Iranian government actively monitors for circumvention use and has arrested hundreds of people. Additionally, if your device is seized, forensic analysis can reveal your circumvention activity and communications history.

How do mesh networks work for communication?

Mesh networks create a decentralized communication system where devices connect directly to each other without depending on central infrastructure like cell towers or the internet. Messages hop from device to device, finding alternative routes if needed. Apps like Briar use Bluetooth to connect nearby devices, allowing communication even when the internet is completely unavailable. This makes them resistant to government shutdown but limited in range and speed.

Why is Signal better than Telegram for secure communication?

Signal uses end-to-end encryption for all communications by default, and the protocol has been independently audited and endorsed by security experts. Telegram's regular chats use server-side encryption (Telegram can technically decrypt them), and the company has a history of complying with government requests in other countries. For sensitive conversations in high-risk environments, Signal's stronger encryption and more transparent security model make it substantially safer than Telegram.

Can the Iranian government completely block all circumvention tools?

Not completely. Decentralized networks like Tor are mathematically designed to be censorship-resistant, and blocking them entirely would require blocking massive portions of legitimate internet traffic. However, the government can make circumvention significantly more difficult through detection and legal enforcement. The arms race between censorship and circumvention techniques is continuous, with each side adapting to the other's strategies.

What is Tor and how does it provide anonymity?

Tor is a volunteer-run network that routes internet traffic through at least three randomly selected relays before reaching its destination. Each relay removes one layer of encryption, so no single point knows both where the traffic came from and where it's going. This makes it extremely difficult to trace communications back to the source. Tor is slower than direct connections but provides much stronger privacy protection than VPNs.

How do international organizations help people in censored countries?

Organizations like the Tor Project, Freedom of the Press Foundation, and Access Now maintain and improve circumvention tools, provide training on secure communication, document human rights violations, distribute resources to activists, and raise international awareness about censorship. They can't directly stop government censorship, but they maintain tools and provide support that help people maintain privacy and access information despite restrictions.

What is DNS tunneling and how does it work?

DNS tunneling encodes data within DNS requests, which are normally used to translate website names into IP addresses. Since DNS requests are usually unencrypted and considered low-risk traffic, governments often don't block them. Tools using DNS tunneling can access blocked content by routing traffic through encrypted DNS tunnels, making it appear as normal DNS activity. However, it's slow and only suitable for text-based content.

Is it safe to use decentralized social media platforms in Iran?

Decentralized platforms like Mastodon and PeerTube are harder to block than centralized alternatives because they don't depend on a single company's servers. However, they're still new technologies with smaller user bases, and the Iranian government may develop new blocking techniques. The safest approach is to treat them as alternatives but not assume complete protection from any single platform.

Conclusion: Resilience in the Face of Digital Control

The story of Iranians overcoming internet censorship isn't ultimately about technology. It's about human resilience, determination, and refusal to accept isolation.

Yes, VPNs matter. Tor matters. Encrypted messaging matters. These tools are essential infrastructure for maintaining communication and accessing information in restricted environments. But they're just tools.

What makes the real difference is people who are willing to take risks. Developers who build circumvention tools despite legal threats. Activists who use these tools despite knowing it could mean imprisonment. Ordinary Iranians who refuse to accept that the government has the right to determine what they see and read.

The Iranian government has deployed some of the world's most sophisticated internet censorship technology. They've made VPN use illegal. They've arrested and imprisoned people for circumvention. They've blocked social media platforms and threatened to shut down encrypted messaging services entirely.

Yet the resistance continues. New tools emerge. Users adapt. Alternative platforms gain adoption. The digital ecosystem finds ways around the walls.

This doesn't mean the situation is optimistic. The government's control is real and oppressive. The consequences for getting caught are severe. The technical barriers are increasing. But the fundamental principle remains: decentralization, encryption, and open-source technology make complete censorship nearly impossible.

For people in Iran, this matters profoundly. It means:

- Journalists can still document abuses and communicate with the outside world

- Activists can still organize and share information

- Ordinary people can still access uncensored news and communicate freely, despite danger

- The government can't achieve total information control, no matter how advanced their technology

For the wider world, the Iranian case is a crucial case study. It shows what's possible with advanced censorship technology. It shows what human rights violations can look like in the digital age. And it shows that censorship, while powerful, isn't invincible if people are determined enough to resist.

The quote that opens this exploration is worth repeating: "Iranians are resilient. They always find ways to speak."

That resilience is the most important technology. Everything else flows from it.

Key Takeaways

- Iran deployed one of the world's most sophisticated censorship systems combining DPI technology, VPN detection, bandwidth throttling, and legal enforcement

- VPNs alone are no longer sufficient—advanced users are combining Tor, DNS tunneling, obfuscation tools, and mesh networks for layered protection

- Decentralized platforms and peer-to-peer networks are inherently more resistant to censorship because they lack a central point of control

- The human cost of circumvention is severe: arrests, torture, and legal prosecution make these tools dangerous, not just inconvenient

- International organizations like Tor Project and Freedom of the Press Foundation provide crucial support, but grassroots innovation from affected communities is the real game-changer

Related Articles

- Iran VPN Crisis: Millions Losing Access Due to Funding Collapse [2025]

- ExpressVPN Deal: 81% Off Two-Year Plans [2025]

- Telegram Blocked in Russia: How Citizens Are Fighting Back With VPNs [2025]

- Mastodon's New Onboarding Features: Making the Fediverse Accessible [2025]

- Freedom.gov: Trump's Plan to Help Europeans Bypass Content Bans [2025]

- Bluesky's Germ Integration: The First Native E2E Encrypted Messenger [2025]

![How Iranians Bypass Internet Censorship: VPNs, Proxies & Digital Resistance [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-iranians-bypass-internet-censorship-vpns-proxies-digital/image-1-1771583807573.jpg)