Medical Research Crisis: Trump Administration's Impact on NIH [2025]

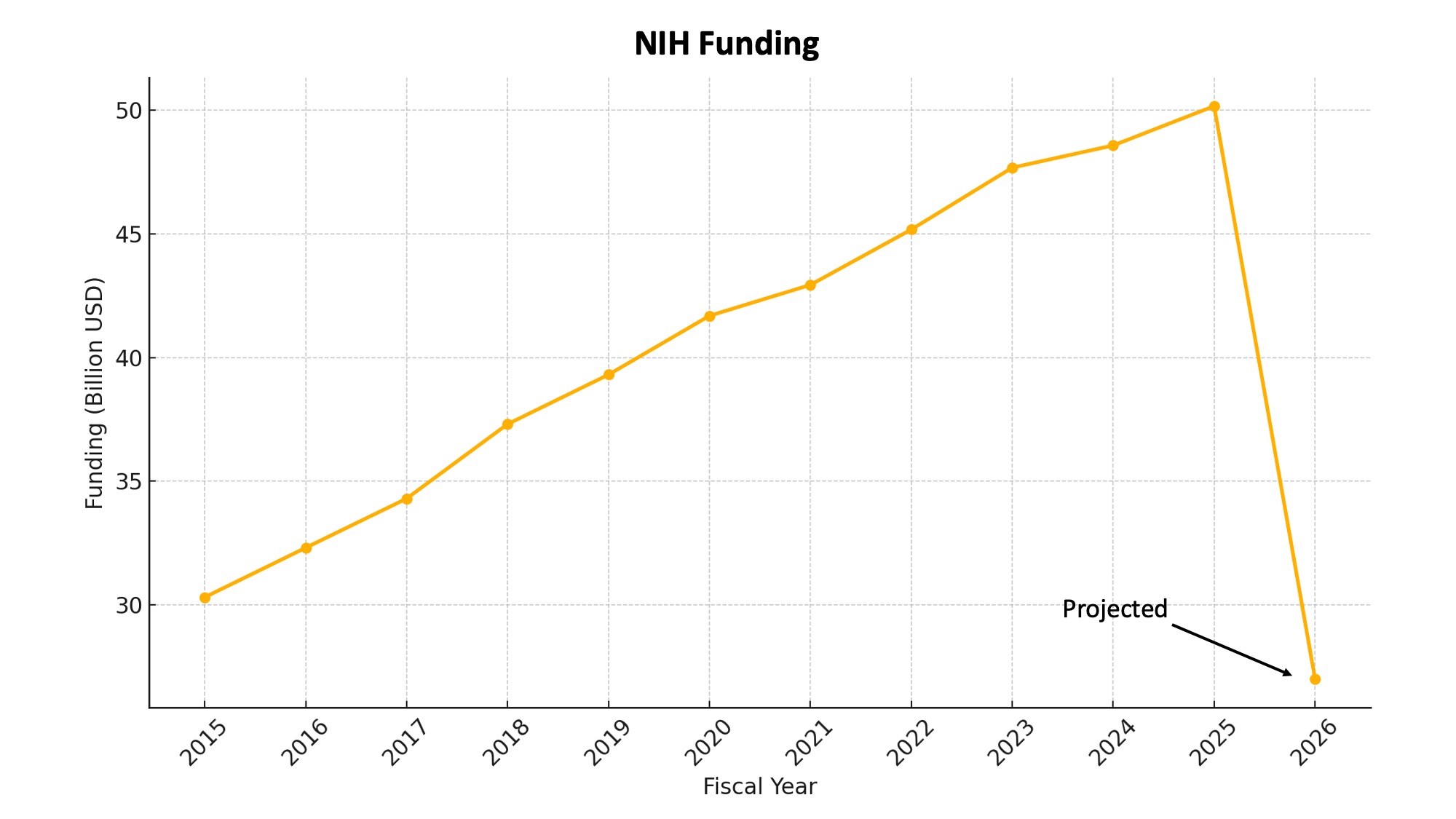

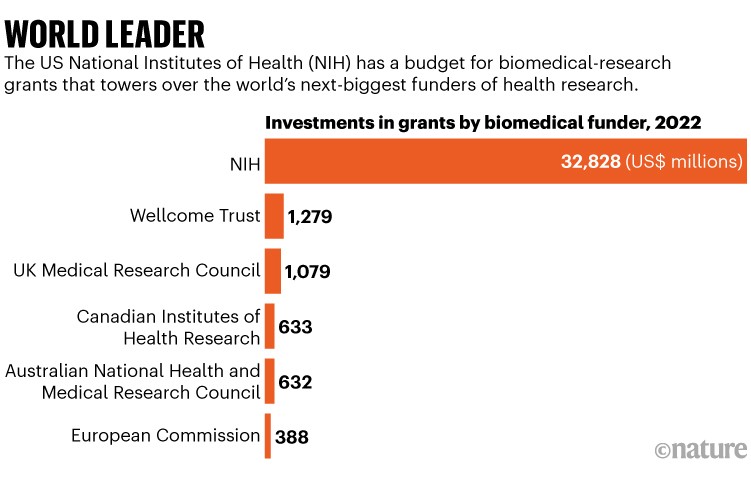

Something extraordinary happened in American medical research this year, and not in a good way. The system that produced Jonas Salk's polio vaccine, that mapped the human genome, that drove decades of cancer breakthroughs—that system hit a sudden, massive wall. Not from budget constraints or natural disasters, but from deliberate policy decisions that rippled through laboratories across the country.

You probably didn't hear much about it in the mainstream press. But if you're a cancer researcher in Chicago, an Alzheimer's scientist in Boston, or a parent with a child enrolled in a clinical trial, you felt it immediately. The disruption wasn't theoretical. It was real, sudden, and it upended careers and clinical care overnight.

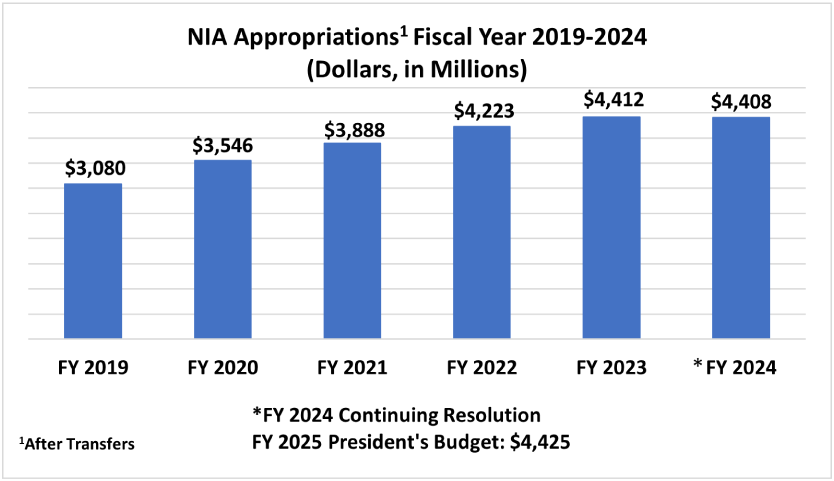

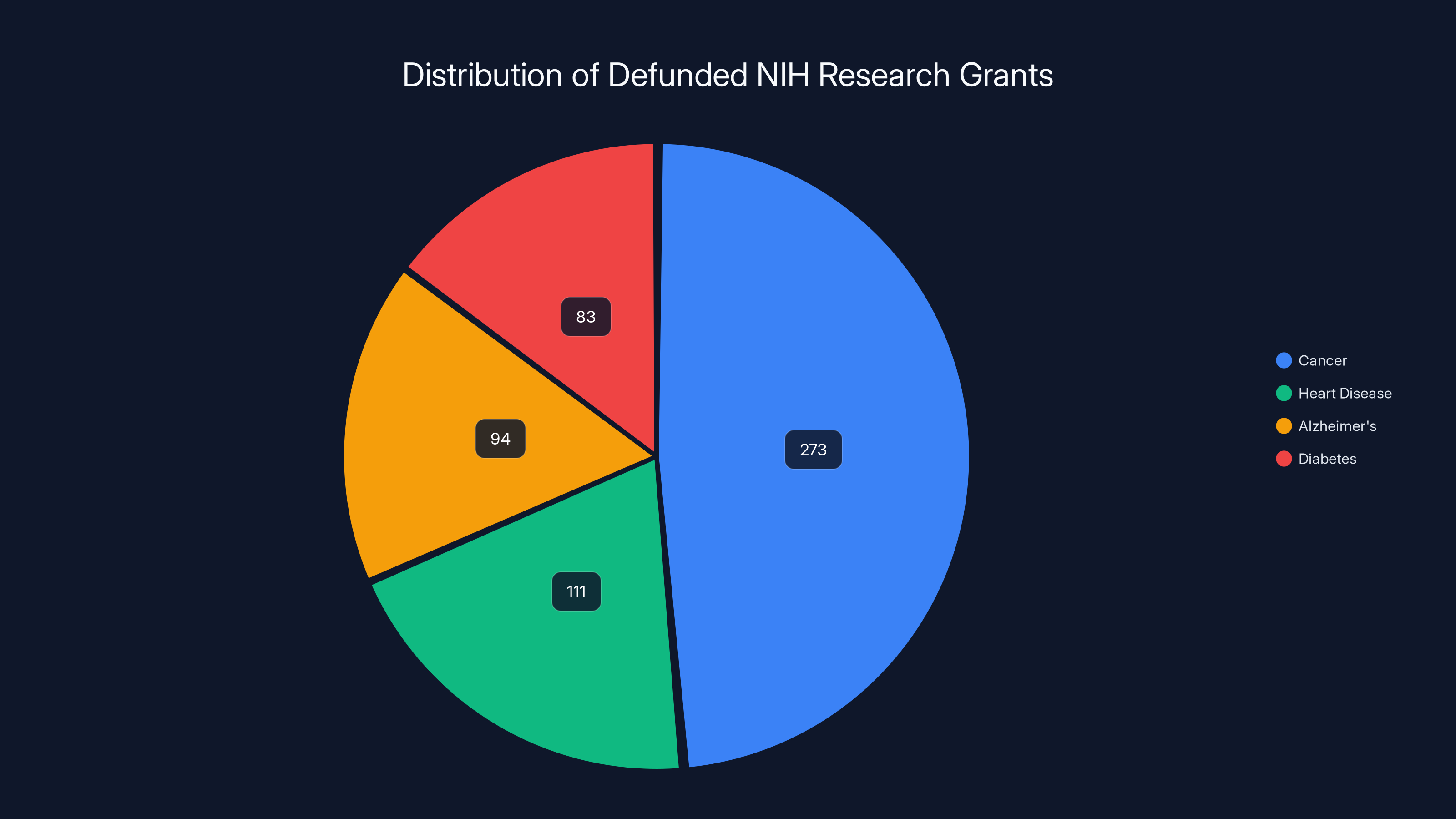

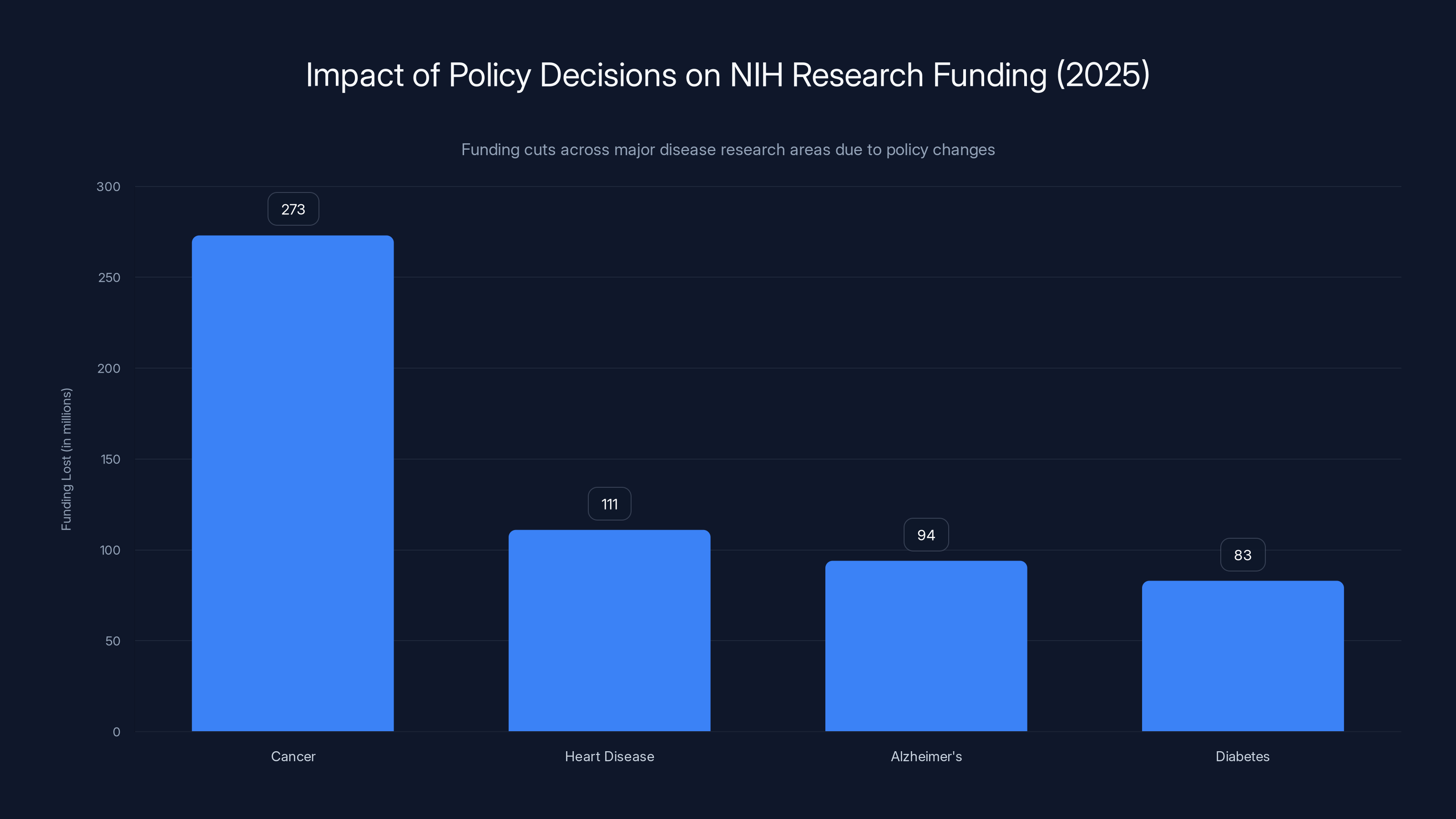

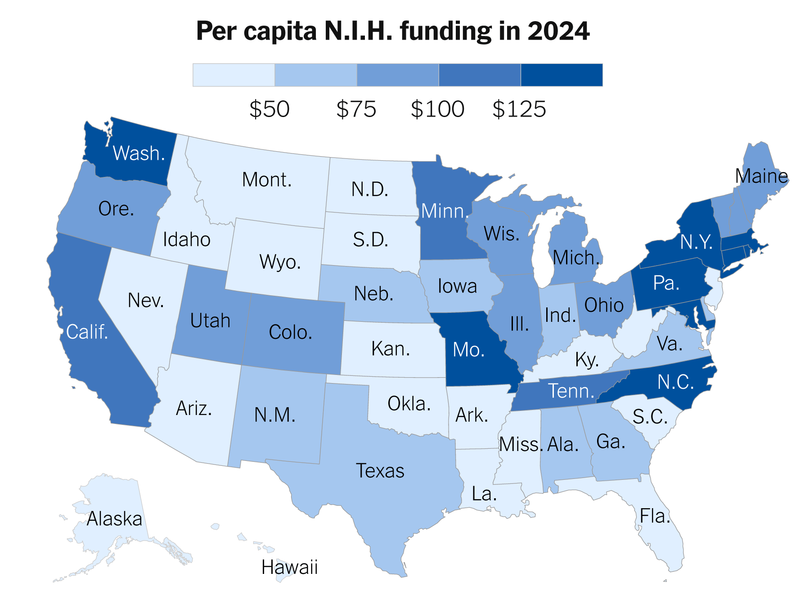

In early 2025, a Senate investigation into the National Institutes of Health painted a portrait of an agency in chaos. The report, released during testimony before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, documented something remarkable: the systematic defunding and disruption of research into four of the leading causes of death in America. The numbers tell the story. One hundred sixteen cancer grants totaling

But the financial numbers only scratch the surface. What happened to the people inside that system—the scientists, the graduate students, the patients—reveals something more troubling about what happens when research institutions lose their footing.

This isn't a partisan political story, though it touches on politics. This is a story about institutional collapse, scientific leadership under pressure, and the real-world consequences when foundational systems lose their stability. Understanding what happened requires looking at the decisions made, the justifications offered, and the actual impact on the ground.

What the Senate Report Actually Found

When Senator Bernie Sanders released his investigative report during Jay Bhattacharya's testimony before the HELP committee, journalists summarized it as "Senate finds Trump admin destroying medical research." The actual report was more granular, which made it more damning.

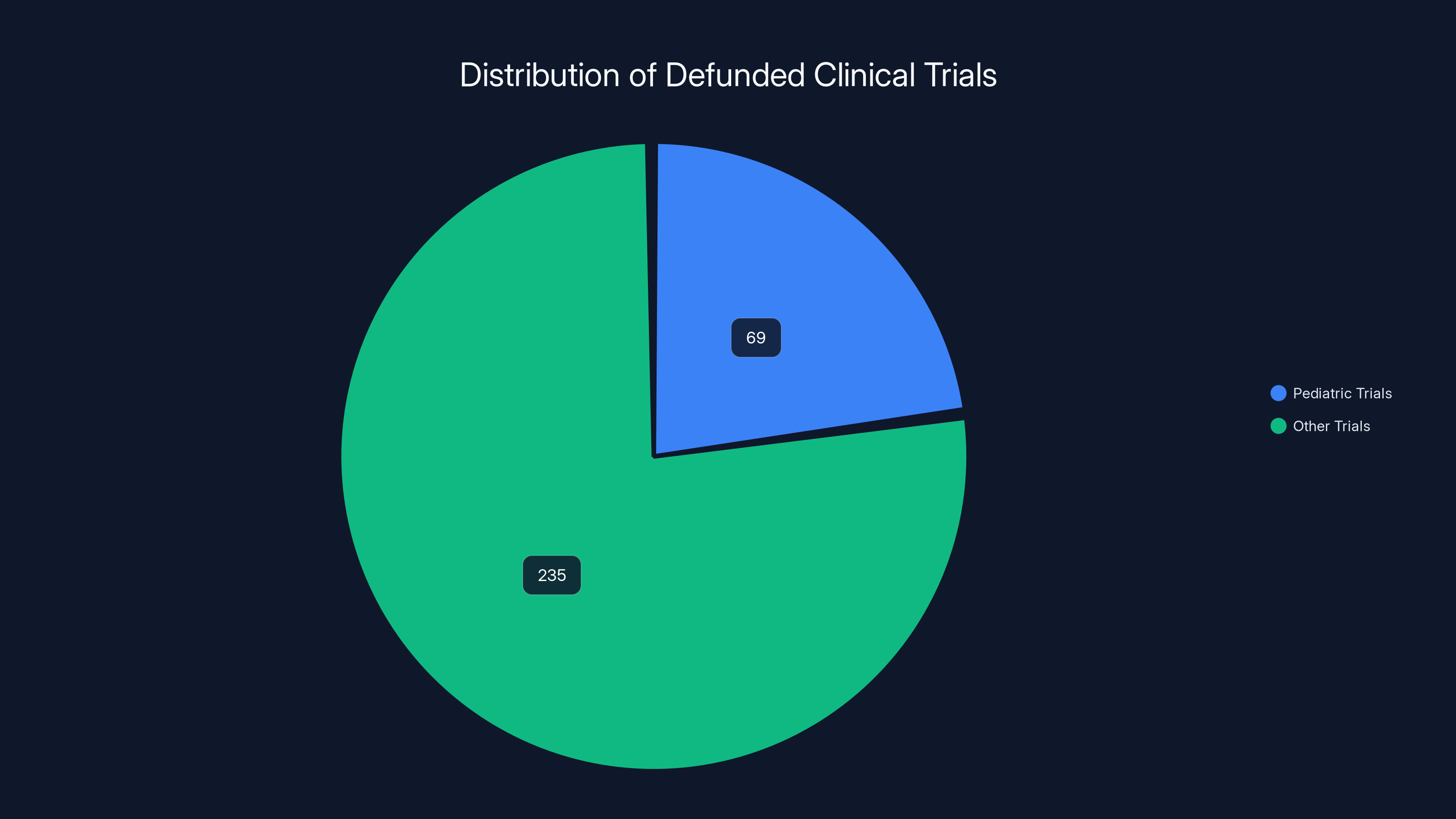

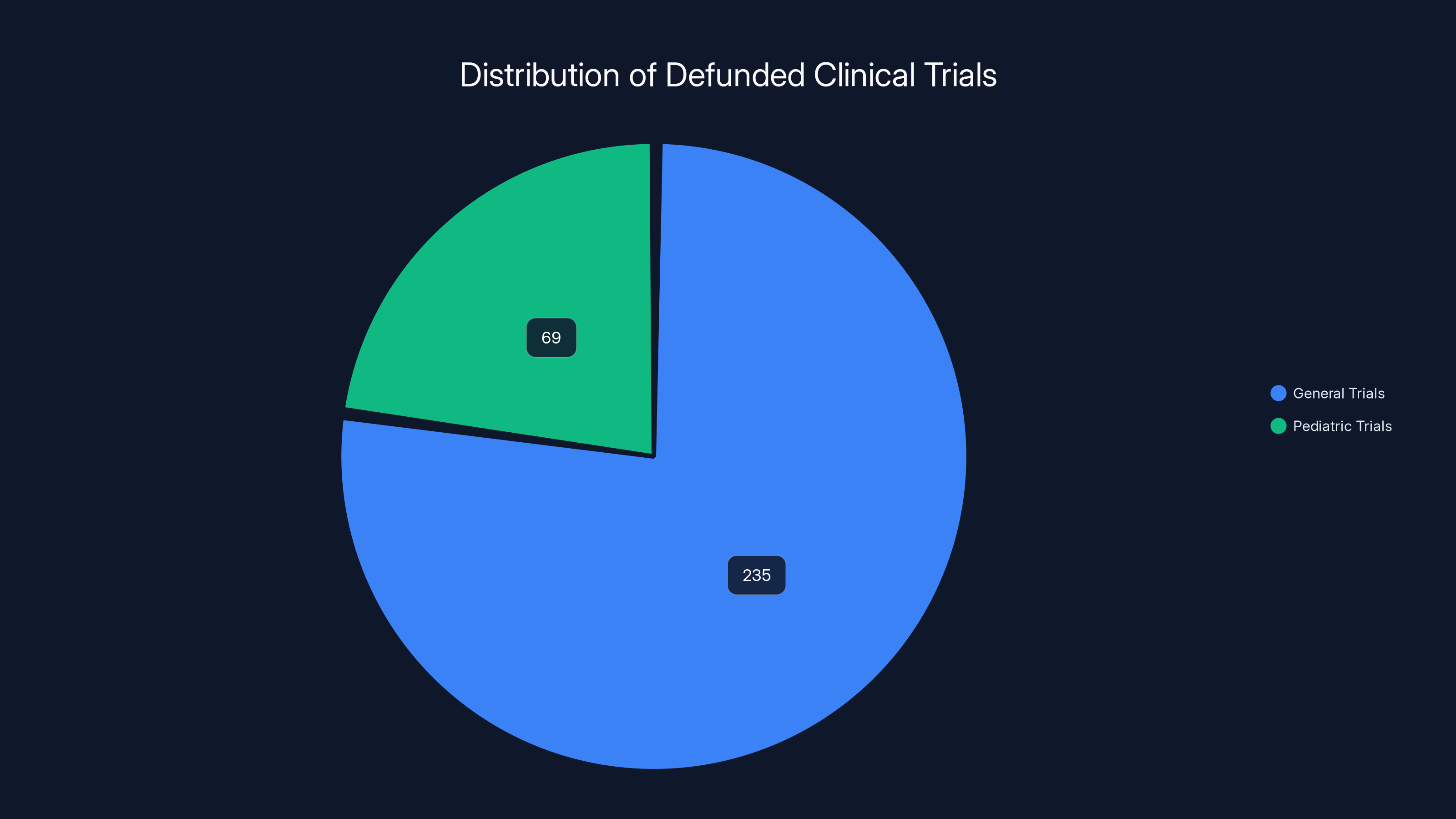

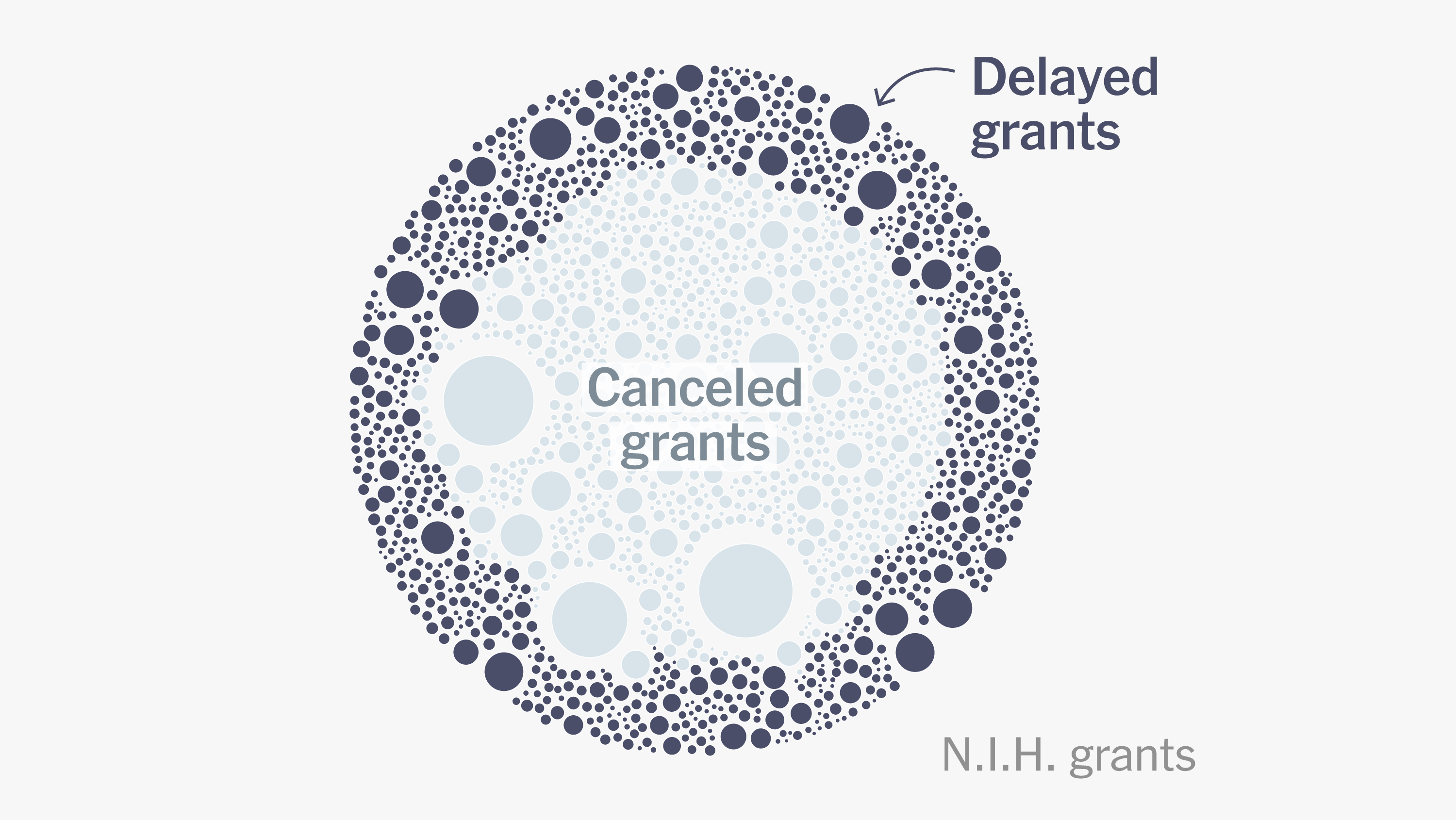

The investigation identified specific, measurable disruptions. Not theoretical concerns. Not projections about future problems. Actual terminations and freezes happening in real time. The report documented at least 304 clinical trials that had been defunded. Of those, 69 were pediatric trials—meaning children were enrolled in studies that suddenly lost funding mid-stream.

Consider what that means in practical terms. A child with leukemia is enrolled in a trial testing a new immunotherapy approach. Their parents have hope because this isn't their only option, but it's their best option. Six months into the trial, the funding stops. The trial ends. The child is removed from the study. There's no continuation protocol because the study wasn't designed to end this way.

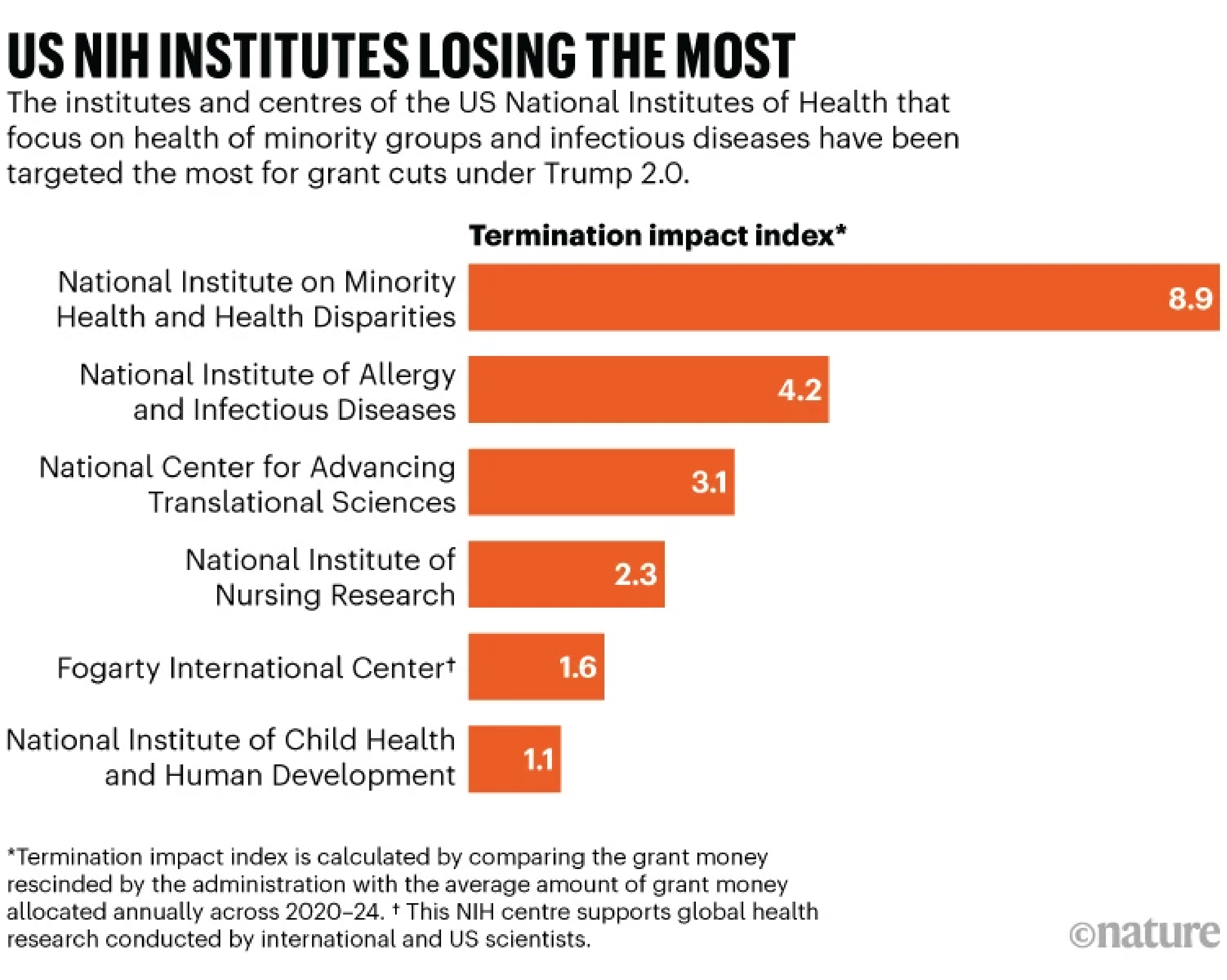

The report also identified something more insidious: a systematic guidance issued by the NIH directing staff to scan all research proposals for ideologically problematic language. The language list reads like a cultural flashpoint inventory. "Diversity." "Climate change." "Gender." "Ethnic." "Social determinants." "Environmental justice." Any study touching these areas faced extra scrutiny and potential defunding based not on scientific merit but on thematic alignment.

This created a chilling effect that extended beyond the explicit cuts. Scientists began self-censoring. Research proposals that might touch on health disparities got reframed. Studies looking at environmental factors in disease got repositioned. The disruption wasn't just financial. It was epistemological. The NIH was no longer just deciding what research got funded. It was deciding what research could even be proposed.

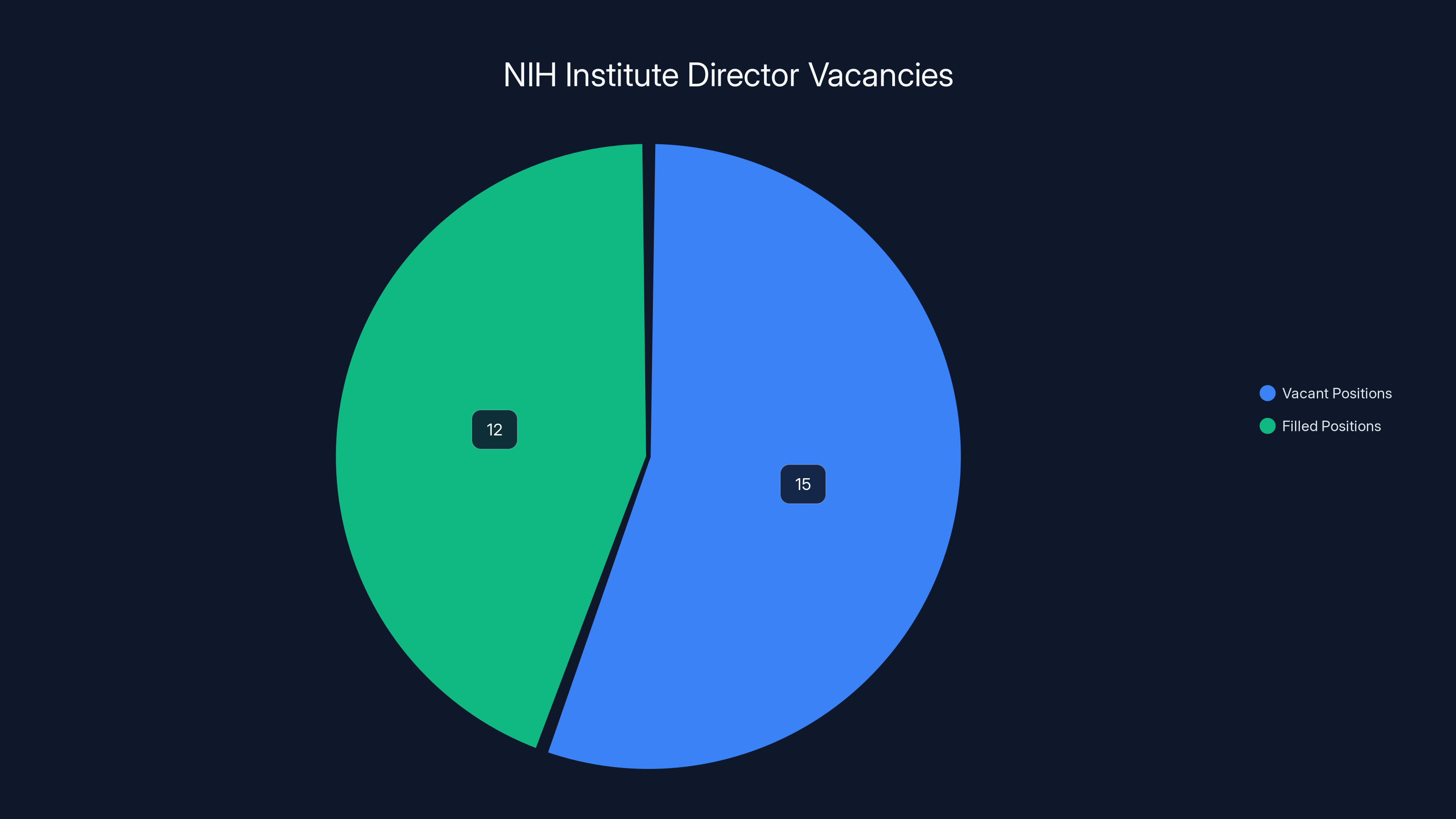

One more detail from the report: of the NIH's 27 institutes and centers, 15 were operating without permanent directors. More than half of the institutes had lost so many advisory committee members that they were on track to lose all voting members by year-end. And research grants can't be approved without sign-off from these committees. In other words, the approval machinery itself was grinding to a halt.

The Senate report found that out of 304 defunded clinical trials, 69 were pediatric, highlighting a significant impact on studies involving children.

The NIH Director's Defense: What Bhattacharya Actually Said

Jay Bhattacharya's testimony on Capitol Hill was a masterclass in parsing language. He arrived at the hearing with a clearly developed strategy: deny, redefine, and redirect.

When confronted with evidence of grant terminations, Bhattacharya flatly denied them. "We didn't cut any funding," he stated. This wasn't technically false—if you define "cuts" in a particular way. The grants weren't cut per se. They were terminated. Frozen. The distinction matters legally and administratively. But it's meaningless to the researcher who can no longer pay their graduate students.

When senators pressed him specifically on grants and trials, he shifted. Yes, grants were terminated, he acknowledged. But some were "refocused" and "restored." When asked for specifics, he offered estimates: "The estimates I'm hearing from my folks is that ultimately it was only a dozen or so trials that were actually terminated. Almost every single other one of them we've refocused, removed to depoliticize them and focus them on the actual science."

That word—depoliticize—became the linchpin of his argument. The disruptions weren't ideological purges, he suggested. They were scientific refocusing exercises. They were about removing political bias and returning to "actual science."

But here's what makes that claim particularly difficult to sustain: the guidance itself was ideological. You don't remove politics by scanning for the word "diversity." You're doing the opposite. You're injecting a specific political perspective into the review process.

When Senator Angela Alsobrooks pointed out that some funding was only restored after lawsuits forced the NIH's hand, Bhattacharya didn't dispute it. "Some of these, the courts had to force," she noted. The implication was stark: the NIH was operating beyond its proper authority, requiring judicial intervention to bring it back within bounds.

On the patient impact question, Bhattacharya offered what might be the hearing's most revealing moment. He said he'd issued orders for continuity of care in disrupted trials. If disruptions occurred, the responsibility fell on the researchers managing the patients, not the NIH. "That is really an unacceptable and outrageous response," Senator Maggie Hassan shot back. "You all disrupted funding. You can make an edict from Washington, DC: 'Oh, don't disrupt continuity of care.' But that can be a very complicated thing."

This exchange captured the fundamental disconnect. Bhattacharya was operating from a bureaucratic logic: the NIH issued directives, therefore the problem is solved. Hassan was operating from a clinical reality: when you defund a trial, actual people experience disruption regardless of what directives you issue.

The Vaccine Question and What Wasn't Said

The vaccine question in Bhattacharya's testimony deserves close examination because it reveals something about how discourse shifts when institutional power changes hands.

Sanders asked directly: "Do vaccines cause autism? Yes or no?" It's a binary question designed to elicit a yes or no answer. The scientific consensus is unambiguous. No. Vaccines do not cause autism. This has been verified across dozens of large-scale studies involving millions of children. The original research claiming to find a link has been thoroughly debunked, and its author lost his medical license.

Bhattacharya answered: "I do not believe that the measles vaccine causes autism." Sanders immediately pressed: "No. I didn't ask about measles. Do vaccines cause autism?" And Bhattacharya responded: "I have not seen a study that suggests any single vaccine causes autism."

Notice the movement. First he qualified it to one vaccine. Then he shifted to "I have not seen a study," which is different from "no study exists." It's a rhetorical move that opens space for claims he doesn't explicitly endorse. Maybe if he'd read more widely, he might have seen a study suggesting vaccines cause autism? The answer leaves that possibility open.

Later in the hearing, Bhattacharya suggested that when he said "I have not seen a study," he meant to imply that if such a study existed, it would be poorly designed or unreliable. But by that point, he'd already created the opening.

This matters because Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the Health Secretary Bhattacharya serves under, has built a substantial part of his public identity on vaccine skepticism. He's distributed materials claiming vaccines cause autism. He's advocated for loosening vaccine requirements. He's brought this ideology into the federal government.

Bhattacharya's carefully hedged language allows him to serve in that administration without explicitly endorsing its most controversial claims. He can say he believes in vaccines while maintaining enough rhetorical distance to not directly contradict his boss. It's a balancing act, and it's revealing about how institutions adapt when their leadership changes.

Out of 304 defunded clinical trials, 69 were pediatric trials, highlighting the significant impact on research involving children and rare diseases.

Where Scientists Are Going: The Brain Drain

The funding disruptions created an immediate practical crisis for the research community, but they're creating a longer-term strategic crisis through emigration.

When NIH funding becomes uncertain, researchers don't just sit around hoping things improve. They start looking elsewhere. And right now, "elsewhere" has compelling offers.

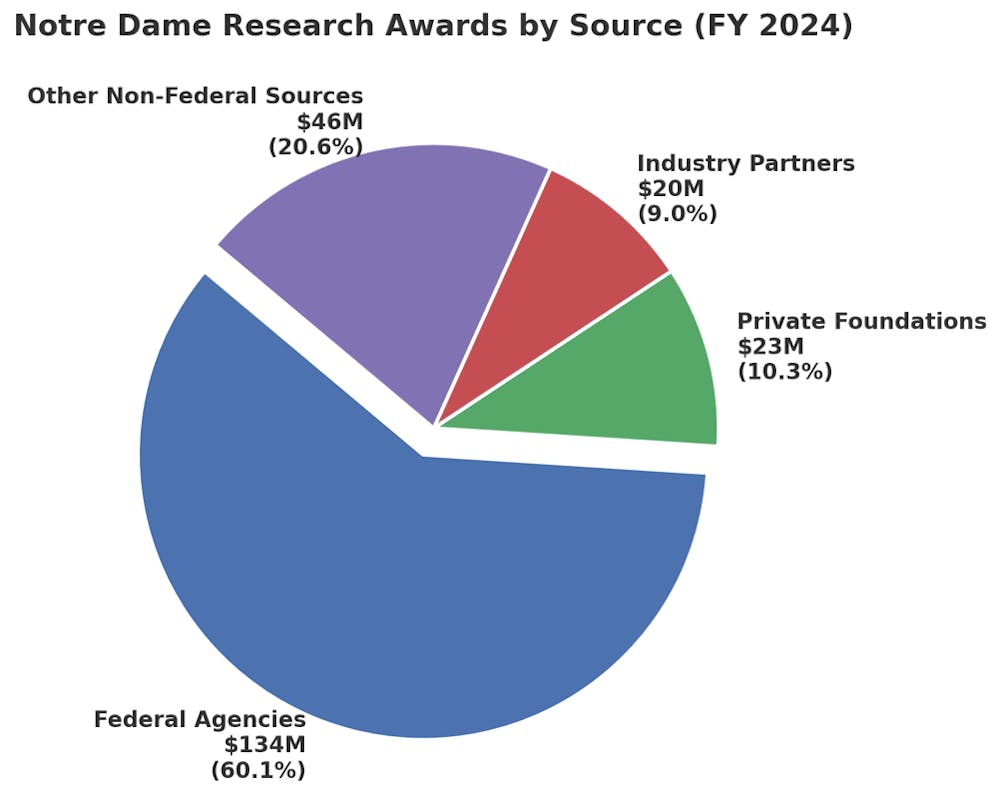

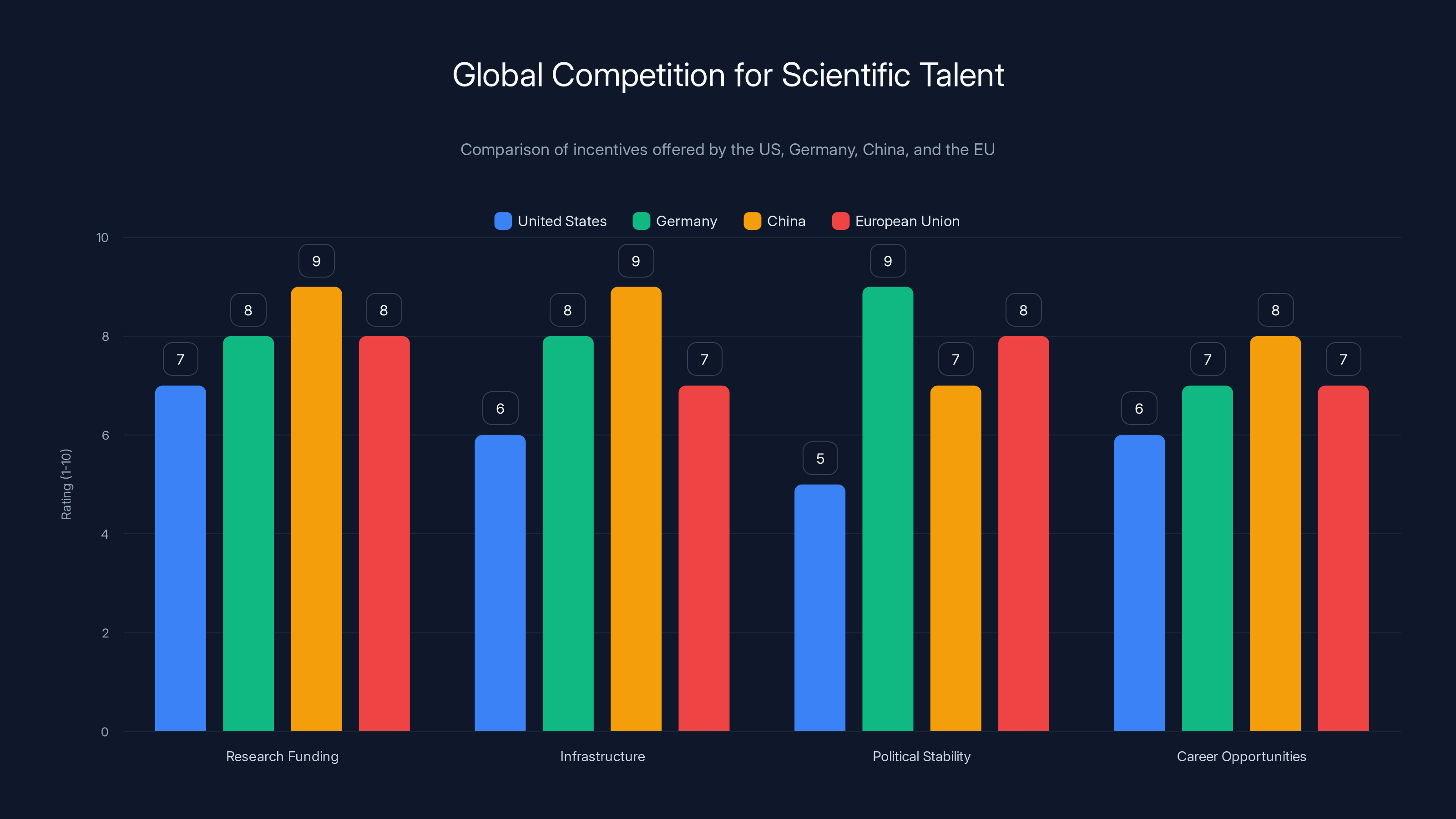

China has made a massive, deliberate effort to recruit American scientists. They're offering substantial research funding, startup money, housing subsidies, and freedom from ideological constraints. Germany and other European countries have launched similar programs. The EU's Horizon Europe program explicitly markets itself as an alternative to the current U.S. research environment.

For early-career scientists—the researchers who should be building the foundation of American biomedical research for the next two decades—this creates a stark calculation. Do I stay in a system that's becoming increasingly unstable and ideologically fraught? Or do I relocate to a place where funding is more predictable and my research questions don't get screened through a political ideology checker?

For many, the choice is becoming obvious. A senior researcher at a major university told colleagues that three promising postdocs on her team were actively exploring positions in Europe. They weren't disgruntled ideologically. They were making a rational decision about where they could continue their careers.

This is how institutional decline accelerates. Once the best people start leaving, the talent pipeline breaks. The people who remain are selected for fit with the new system rather than for brilliance. Recruitment becomes harder. Eventually, you end up with a brain drain that takes years to recover from, if recovery is even possible.

The historical parallel is instructive. In the 1990s, the British government made substantial cuts to university research funding. The immediate impact was reduced research output. The longer-term impact was that an entire generation of British scientists migrated to the U.S. Many never came back. It took the UK more than a decade to rebuild its research capacity.

We're watching that process start in the U.S. in real time, except this time the drain is going outward rather than being a reversal of an earlier migration.

The Impact on Clinical Care: Real Patients in Real Trials

The Senate report's documentation of 304 defunded clinical trials is significant not just as a number but as a representation of disrupted lives.

Clinical trials exist in a specific ethical and regulatory framework. A patient agrees to participate in a study based on informed consent. That consent is based on specific terms: this is the protocol, this is the duration, this is what we're studying. There's an implicit assumption that the study will continue as designed unless something goes catastrophically wrong.

When funding disappears, that assumption breaks. The study doesn't end gracefully. It stops. Researchers scramble to figure out what happens next. Patients get notifications that their trial is ending. For some, that's manageable. For others, it's devastating.

One critical scenario: a patient is enrolled in a trial for a treatment that shows promise. They've exhausted standard treatments. This trial is their best option. They've been getting the experimental treatment for six months and seeing improvement. Then the funding stops, the trial ends, and the treatment becomes unavailable. They're not worse off than before the trial in an absolute sense, but they've lost access to something that was working.

Consider the pediatric trials specifically. Sixty-nine children's trials were defunded. That means nearly 70 separate research projects involving children came to sudden stops. Some of these trials were investigating rare pediatric diseases. The research pool for rare diseases is already small. Defunding trials in rare disease research doesn't just disrupt current patients. It potentially extends the timeline for developing treatments by years.

The regulatory framework for clinical trials also means that restarting a defunded trial isn't simple. The regulatory approval required to initiate the study again is substantial. In some cases, investigators will just abandon the research project entirely rather than navigate the reinitiation process.

This creates a hidden cost to the disruptions. Some research projects that were terminated won't just be delayed—they'll be abandoned. The scientific knowledge that would have been generated gets lost.

The Leadership Vacuum: 15 Directors Missing

One detail from the hearing received less attention than it deserved: 15 of the NIH's 27 institute directors' positions were vacant.

This isn't a minor administrative issue. Institute directors are the actual operational leaders of the NIH. They set research priorities, guide funding decisions, manage personnel, and represent their institutes to the external research community. When 55% of your institute directorships is vacant, you don't have a full organization. You have a skeleton crew.

For directors to depart—and many departed or refused to stay when the new administration took over—suggests something about institutional culture. They were comfortable serving under the previous leadership. They were not comfortable under the new leadership.

The reasons varied. Some had fundamental disagreements about the new policy directions. Some were uncomfortable with the political pressure being applied to scientific decisions. Some had personal relationships with the previous administration and saw the new one as hostile to their values. Some were simply older and decided this was a good time to retire rather than navigate a turbulent period.

Whatever the individual reasons, the collective result was a leadership crisis. When you're replacing 55% of your senior leadership, you're not doing incremental adjustments. You're reconstituting your organization.

Advisory committees compounded the leadership problem. The report noted that more than half the institutes would lose all voting advisory committee members by year-end if current trends continued. Advisory committees are separate from the director structure, but they perform a critical function: they evaluate grant proposals and make recommendations for funding. Without advisory committee members, you can't approve grants. It's not a procedural slowdown. It's a complete blockage of the approval process.

The question hanging over this is whether it was accidental or intentional. Did the new administration deliberately create these vacancies and committee resignations, or did they result from the chaos of institutional transition? The distinction matters. If intentional, it suggests a coordinated effort to remake the NIH in a new image. If accidental, it suggests incompetence in managing a complex transition.

Based on Bhattacharya's testimony and the documented guidance on problematic language, it seems at least partly intentional. You don't accidentally purge an organization of experienced leadership. You also don't accidentally issue guidance scanning for ideologically problematic terms in research proposals. Those are deliberate choices.

The largest share of defunded NIH research grants was in cancer research, accounting for

The Ideology Screening Problem: Language and Power

The guidance issued by the NIH directing staff to flag research containing certain language is perhaps the most revealing detail in the entire situation.

The list is extensive: diversity, climate change, gender, ethnic, social determinants, environmental justice, health disparities, and multiple other terms. Some of these are clearly ideologically charged in current American political discourse. Others seem almost innocuous—why would "ethnic" be flagged? Until you consider that ethnic differences in disease susceptibility is an important area of biomedical research. If you're screening for the word "ethnic," you're automatically flagging research investigating ethnic health disparities.

But here's what's instructive about this: screening for language is a way to impose ideology without explicitly stating that you're doing so. You don't say, "We don't fund research we disagree with politically." You say, "We're removing political language and focusing on science." Then you scan for a list of words that, when removed, fundamentally reshape what questions researchers can ask.

It's an elegant mechanism of control because it appears procedural and neutral. You're just checking for certain language. You're not saying the science is bad or the questions are wrong. You're just noting that the framing is problematic.

Consider a researcher studying the relationship between environmental pollution and childhood asthma rates. If they frame it as "investigating how environmental injustice contributes to health disparities in lower-income communities," their proposal gets flagged. If they reframe it as "investigating environmental factors in asthma incidence," it doesn't.

Same science. Different framing. But the reframing strips away attention to disparity and injustice. It makes the research more "neutral" in the sense that it doesn't explicitly name inequality. But it's not actually more neutral. It's just ideologically neutral in a different direction.

This is how institutional control works at a level below explicit censorship. It's a mechanism that allows leaders to reshape the institution without having to directly suppress or reject research they dislike. Instead, they just change the linguistic environment in which research is conceived and proposed.

Historically, this technique has been used in various contexts, from academic freedom to journalism. It's effective because it appears voluntary. Researchers adopt the new language not because they're forced to, but because they adapt to the institutional environment. Over time, the new language norms become internalized.

The Restored Grants That Weren't Really Restored

Bhattacharya claimed that many frozen grants had been restored, suggesting the crisis was less severe than the Senate report indicated. Senator Alsobrooks pushed back on this claim, pointing out that some restoration only happened because of lawsuits.

This is a critical distinction. When you have to sue the federal government to restore legally approved funding, that's not a sign of a well-functioning system. It's a sign that the system is operating outside its proper constraints.

How did lawsuits become necessary? Because the NIH made decisions to freeze funding that legally approved grants, which had already been peer-reviewed and approved through proper channels. Freezing previously approved funding is not a standard power the NIH director has. It's an extraordinary action that violates the normal administrative process.

When extraordinarily illegitimate, then restoration "after being sued" isn't the same as restoration through normal processes. It's an indication that the NIH was attempting to do something it didn't have authority to do, and only backed down when legally compelled.

This matters because it suggests the disruptions weren't primarily about scientific judgment or budget priorities. They were about power. The new administration wanted to exercise control over which research got funded, and it was willing to take legally questionable actions to exert that control.

Some of the restoration happened without lawsuits, but that doesn't necessarily mean it was voluntary. It might mean that the threat of litigation was sufficient to cause reversal. Or it might mean that Bhattacharya and his team realized they'd overextended their authority and backed down preemptively.

Either way, the pattern is revealing. You don't need restoration if you never disrupted funding in the first place.

What Continuity of Care Actually Means When You Defund Trials

Bhattacharya's defense on patient impact hinged on an assertion that he'd ordered continuity of care for disrupted trials. The implication was that therefore no patients should have experienced disruption.

This reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how clinical trials work, or a deliberate misrepresentation of how easily disruption can be managed.

A clinical trial is a complex administrative and logistical operation. Patients are screened, enrolled, assigned to treatment arms, monitored, and followed up. The research institution providing the trial has infrastructure dedicated to managing these operations: regulatory affairs staff, data managers, trial coordinators. All of that infrastructure is funded through the trial budget.

When you defund the trial, the trial coordinators still exist, but they have no budget to operate on. The regulatory staff still exist, but they're not being paid to manage the trial. The data management infrastructure still exists, but it's not being maintained.

You can issue an edict from Washington saying continuity of care must be maintained. But the practical mechanisms for maintaining continuity don't work without the funding. It's not that researchers are unwilling to maintain continuity. It's that they literally don't have the resources to do so.

Some trials did manage to continue treating patients while sorting out the funding situation, usually because the research institutions absorbed the costs using other funding sources. But that's not a sign of successful management. That's a sign of institutions scrambling to fill in a hole created by the defunding.

The pediatric trials are particularly instructive here. When you defund a pediatric trial, you're not just affecting the ongoing treatment. You're affecting the regulatory and ethical oversight that ensures the trial is being conducted safely. Pediatric trials have extra regulatory requirements. If those regulatory functions aren't funded, they can't be maintained.

Hassan's response—"That is really an unacceptable and outrageous response"—accurately captured why this logic doesn't work. You can't defund something and then claim the resulting disruption is someone else's responsibility.

In early 2025, NIH experienced significant funding cuts across major disease research areas, with cancer research losing the most at $273 million. These cuts highlight the severe impact of policy decisions on scientific progress.

The Advisory Committee Crisis and Grant Approvals

The detail that more than half the institutes would lose all advisory committee members by year-end reveals a system approaching complete institutional dysfunction.

Advisory committees in the NIH serve a gatekeeping function. When a researcher submits a grant proposal, it goes through multiple reviews. One of those reviews involves an advisory council of experts in the relevant field. These are usually prominent researchers, some from academia, some from industry, some from government. They evaluate proposals and make recommendations about which ones should be funded.

The committees aren't just rubber stamps. Good advisory committees engage seriously with proposals, ask tough questions, and catch scientific problems that might have been missed in earlier reviews. They also represent the broader research community to the NIH, ensuring that the agency stays connected to what's happening in the field.

But advisory committees are voluntary service positions. Experts serve without compensation. They do it because they care about advancing the field and they see it as a responsibility of senior scientists to contribute to the scientific enterprise.

When institutional chaos erupts, some advisory committee members resign. Their loyalty to service can only stretch so far. If serving on an NIH committee becomes a way of endorsing policies they disagree with, or if the experience becomes too frustrating or chaotic, they step down.

The report's finding that institutes were on track to lose all advisory committee members by year-end wasn't a projection about the future. It was documenting a trend already underway. Senior scientists were leaving the committees.

Without advisory committees, the approval machinery grinds to a halt. You can't approve grants without committee sign-off. So the research pipeline stops. Researchers can't get funded. They can't conduct research. They can't make progress on their scientific questions.

This is how you destroy a research enterprise without explicitly cutting budgets. You don't need to eliminate funding if you eliminate the approval mechanism. The money can sit there—theoretically available but functionally inaccessible.

Bhattacharya's response was noncommittal: they're working on it. But "working on it" suggests this wasn't anticipated or planned for. It suggests the disruption in advisory committees was a collateral consequence of the broader institutional chaos, not a managed transition.

If you were purposefully restructuring an agency, you'd ensure continuity of critical functions. You'd have new advisory committee members ready to step in before existing members left. You'd plan for the transition. The fact that this wasn't happening suggests either profound mismanagement or a acceptance of chaos as a necessary part of implementing the desired changes.

Comparing Past Institutional Crises: What History Tells Us

Understanding what's happening at the NIH benefits from historical comparison. Institutional disruptions in research agencies aren't unprecedented, and history shows patterns about what happens next.

The most directly relevant historical example is what happened in British academic research in the 1990s. The British government, under Margaret Thatcher and her successors, made substantial cuts to university research funding. The immediate effect was reduced research output and smaller grants. But the longer-term effect was emigration.

Britain lost an entire generation of scientists to the United States. Many of the most talented researchers took positions at American universities and research institutions. Some of these researchers eventually returned to Britain, but many built their careers in the U.S. and never came back. The result was that Britain's position in global research rankings declined for a decade or more. Recovery required a substantial, deliberate re-investment and a systematic effort to rebuild research capacity.

Another historical parallel: when the Soviet Union dissolved, many top Soviet scientists emigrated to the United States. Some went to Germany and Western Europe. The brain drain from Russia was massive and persistent. The U.S. research enterprise benefited substantially from this migration. Russia's research capacity took decades to rebuild, and even now, Russia is a less significant player in global research than it was during the Soviet era.

What these examples show is that research brain drain isn't reversible on a short timeline. Once talented scientists leave, recruiting them back is difficult. They've built careers elsewhere, established networks, and adapted to different systems. Some will return, but many won't.

The U.S. has been the beneficiary in previous contexts—American institutions attracted British and Soviet scientists, enhancing American research capacity. Now the risk is that the U.S. is moving into the position Britain occupied in the 1990s: a formerly dominant research environment becoming less attractive.

China and Germany understand the opportunity here. They're not being subtle about it. They're actively recruiting American scientists with explicit offers: better funding, less ideological constraint, prestige institutions. It's a coordinated effort to shift research talent away from the U.S.

If the U.S. research environment becomes unstable—if scientists can't predict whether their funding will continue, if their research questions are subject to ideology checks, if institutional leadership is chaotic—then the recruiting pitches from other countries become more persuasive.

This isn't paranoia or projection. It's pattern recognition based on what happened when other major research powers became less attractive.

The International Competition for Scientific Talent

America's dominance in biomedical research wasn't inevitable. It was the result of deliberate choices: consistent funding, protection of scientific independence, investment in institutional infrastructure, and commitment to supporting basic research.

Those conditions are now in question. And other countries are explicitly positioning themselves as alternatives.

Germany's Max Planck Society has increased recruiting efforts in the United States. The group highlights the strength of German research infrastructure, funding stability, and freedom from political interference. Germany specifically appeals to researchers concerned about the current American research environment.

China has invested massively in research capacity. The government has created programs explicitly designed to attract foreign scientists. These programs offer substantial research funding, housing subsidies, and streamlined immigration. China's pitch is straightforward: come here, you'll have resources to do good science, and we're investing heavily in research infrastructure.

The European Union's Horizon Europe program has expanded to include more funding and more opportunity for non-EU researchers. The program explicitly markets itself as an alternative to what it characterizes as an increasingly unstable U.S. research environment.

For early-career scientists, the calculations are becoming concrete. A postdoc in the U.S. might have a position for 2-3 years, with uncertain prospects for transition to an independent research group. A postdoc in Germany or China might have access to clearer pathways to permanent positions and more stable funding prospects.

This represents a shift in the balance of incentives that determines where scientific talent flows. For decades, the U.S. could count on being the most attractive destination for top talent. That advantage is now in question.

If American biomedical research wants to maintain its position globally, it needs to be more attractive than the alternatives. Right now, that's not obviously the case for researchers concerned about research independence and institutional stability.

55% of NIH institute director positions are currently vacant, highlighting a significant leadership gap within the organization.

What the Research Community Is Saying Privately

Public statements from the research community have been relatively measured. Scientists have criticized the disruptions, called for stable funding, and expressed concern about the new policy environment. But private conversations paint a darker picture.

Senior researchers are telling colleagues that they're considering retirement earlier than planned. Some are researching positions abroad. Others are looking at industry positions where research independence might be more protected. Still others are looking at periods of sabbatical, hoping the situation will stabilize.

Graduate students and postdocs are the most vocal about considering emigration. These are researchers early in their careers, weighing where they want to build their scientific lives. The U.S. was the default choice for many. Now it's one option among several.

Research institutions are reporting that recruitment is becoming harder. Promising candidates who would have automatically chosen positions at top American universities are now considering alternatives. Retention is also becoming harder—established researchers are receiving offers from institutions abroad and considering them seriously.

This is still early in the process. But the direction is clear. Institutional disruption creates uncertainty, and uncertainty causes talented people to leave.

What's particularly concerning is that some of the smartest and most independent-minded researchers are the most likely to leave. The people most bothered by ideology constraints and institutional chaos are often the people most capable of succeeding elsewhere. So the emigration isn't random. It's selection for the kind of people you most need in a research enterprise.

The Gap Between Official Statements and Ground Reality

One of the most striking patterns in this situation is the gap between what leadership says is happening and what researchers report experiencing.

Bhattacharya says the NIH is the best place in the world to do biomedical research. Meanwhile, researchers are reporting uncertainty about whether they can continue their work, whether their graduate students can be paid, whether their trials can continue.

Bhattacharya says he's maintained continuity of care for disrupted trials. Meanwhile, patients are being removed from trials and research institutions are scrambling to absorb costs using alternative funding.

Bhattacharya says only a dozen or so trials were actually terminated. Meanwhile, the Senate found 304 defunded trials.

This gap isn't unusual in institutional crises. Leadership often operates from different information, has different incentives, and interprets events through different frameworks than people on the ground. Leadership is invested in communicating stability and control. People on the ground are experiencing disruption and uncertainty.

But the gap also indicates something about communication breakdown. If there's this much distance between what the director says and what researchers experience, that suggests the institutions and mechanisms for conveying ground truth to leadership are broken.

A well-functioning institution has feedback mechanisms. Scientists report problems. Information flows back to leadership. Leadership responds. If leadership is radically out of touch with what's actually happening in the organization, that's a sign those feedback mechanisms have failed.

It could be that Bhattacharya genuinely doesn't understand the magnitude of disruption his decisions have caused. It could be that information is being filtered before it reaches him. It could be that he does understand but chooses to mischaracterize it publicly. Any of those possibilities is concerning for different reasons.

Explaining the Energy Behind the Disruptions

One question worth asking: why do this? Why deliberately disrupt medical research? What's the motivation?

Part of the answer is ideological. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has expressed skepticism of vaccines, concerns about pharmaceutical influence, and a broader ideology skeptical of medical establishment authority. Restructuring medical research to be more skeptical of mainstream medical approaches aligns with this ideology.

Part of the answer is about power. Reorganizing institutions and exerting control through funding decisions is a way of establishing authority. Bhattacharya may genuinely believe that removing "political" language from research proposals is scientific improvement. And he clearly wants to establish that it's his authority—not previous structures and institutions—that determines what research gets funded.

Part of the answer may be about signaling to constituencies. The new administration has positioned itself as challenging institutional orthodoxy and disrupting established power structures. Disrupting the medical research establishment can be presented as part of that broader project.

But there's no coherent long-term strategy evident here. No vision for what better medical research would look like. No plan for how to maintain research capacity while changing research directions. Just disruption without replacement.

The best functioning organizations make changes from a position of strength, with clear new direction and careful management of transitions. This looks like disruption for its own sake, which is how you damage institutions.

Germany and China are increasingly competitive with the US in attracting scientific talent, offering robust funding and infrastructure. (Estimated data)

What Recovery Would Look Like

If you wanted to undo the damage described in the Senate report, what would that take?

First, restore funding to all terminated grants and trials. That needs to happen quickly, before more researchers emigrate and institutional knowledge is lost.

Second, address the leadership vacuum. Recruit experienced researchers to serve as institute directors. Remove the ideology-based language screening and return to purely scientific merit-based evaluation. Rebuild the advisory committees by recruiting prominent scientists.

Third, explicitly commit to research independence. Scientists need assurance that their research questions won't be subjected to political screening. That needs to come from leadership in unambiguous terms.

Fourth, invest in rebuilding recruitment and retention. Once the institutional environment has stabilized, you need active efforts to recruit back some of the scientists who left and to attract top talent from abroad.

Fifth, address the international competition directly. American research institutions need to be more competitive than alternatives, which might require improved funding, reduced bureaucracy, or other incentives.

Sixth, rebuild trust. Researchers need to believe that what happened won't happen again. That requires not just changed policies but changed institutions and accountability structures.

None of this is impossible, but all of it requires political will to invest in and commit to scientific research as a national priority. And it requires leadership that sees the research enterprise as a resource to strengthen rather than a target to control.

It took Britain over a decade to recover from the research disruptions of the 1990s, and Britain is a smaller country with lower research costs. American recovery would take longer and cost more.

Institutional Lessons for the Future

Beyond the specific situation at the NIH, this situation offers broader lessons about institutional resilience and fragility.

Institutions appear stable until they suddenly don't. The NIH had operated on certain principles—scientific merit-based evaluation, independence from political interference, stable funding for approved research—for decades. Those principles seemed embedded in the structure.

But structures are only as stable as the people running them believe in those structures. When leadership changes and the new leadership doesn't share the previous commitment to those principles, the structure can shift quickly.

Second, institutional control can be exercised through language and process rather than explicit edicts. You don't have to forbid certain research. You just screen for problematic language. You don't have to deny grants. You just slow down the approval process or require extra justification. Those mechanisms are harder to fight because they operate in the register of procedure rather than explicit policy.

Third, institutions depend on continuity of talented people. When talented people leave, institutions degrade. And talented people leave when institutional stability and independence are in question. So institutional disruption creates conditions for further degradation through emigration.

Fourth, leadership communication matters enormously. When leaders deny or minimize problems that are obvious on the ground, it breaks trust and accelerates institutional decline. People stop believing what leadership says, which means leadership loses ability to shape institutional behavior through communication.

Finally, institutional change motivated by ideology rather than problem-solving tends to be destructive. You can change institutions in productive ways if you're solving problems. But if you're restructuring primarily to exert control or implement ideology, you usually make things worse.

Runable for Research Documentation and Collaboration

In the context of research disruption and institutional chaos, tools for managing research documentation and collaboration become more important. Runable offers AI-powered automation for creating and managing research documentation, presentations, and reports—functionality that could help research teams maintain continuity when institutional support is disrupted.

Research teams dealing with funding uncertainty might benefit from systems that automate documentation and reporting, reducing administrative burden when staff resources are constrained. Runable's AI agents can generate research reports and documentation from existing data, helping teams maintain institutional knowledge and progress documentation even when organizational systems are in flux.

For research institutions managing multiple disrupted projects, centralized documentation systems become critical for tracking what was accomplished, what remains, and what needs to be resumed if funding is restored.

Use Case: Research teams managing documentation of disrupted clinical trials and ensuring continuity of research records.

Try Runable For FreeThe Broader Implications for Scientific Progress

Medical research operates on timescales that don't align with political terms. A researcher might spend a decade developing a therapy, another five years testing it in trials, and another five years getting it through FDA approval. Political disruptions in the middle of that timeline don't just delay that one project. They potentially accelerate the timeline for competitors in other countries to catch up.

When American researchers emigrate and research funding is disrupted, you're not just affecting current research. You're affecting treatments that won't be developed for another 10-15 years. The decisions made now ripple forward for decades.

From a competition perspective, this is strategically disadvantageous. China and other countries understand that research capacity built now will be producing advances 10-15 years from now. Disrupting American research capacity while investing in alternatives accelerates the shift in research dominance globally.

This isn't a speculative concern. It's what happened when the U.S. invested heavily in research after World War II, producing American dominance in the second half of the twentieth century. It's what happened when countries that failed to invest in research fell behind. Research capacity is a long-term strategic asset. Disrupting it produces long-term strategic disadvantages.

The Question of Intentionality

Throughout this analysis, one question keeps emerging: is this intentional or accidental?

The ideology-based language screening suggests intention. That's not something you stumble into. It's a deliberate policy decision.

The grant terminations and funding freezes also suggest intention. You don't accidentally defund hundreds of millions of dollars in research.

But the leadership vacuum and advisor committee collapse might be accidental consequences rather than deliberate choices. When new leadership arrives with a different ideology, some experienced people leave or resign. That's predictable, but it's not necessarily planned for.

The most likely answer is that this is partially intentional and partially accidental. Bhattacharya and his team clearly intended to exercise control over research direction through ideology-based screening and selective funding. They probably didn't intend for that to produce a leadership vacuum and advisory committee collapse, but they didn't prepare for it either.

The result is disruption that's partly deliberate and partly collateral damage from the deliberate disruption. That's actually worse than pure accident because it suggests the leadership underestimated the consequences of their actions or didn't care about those consequences.

What Comes Next

The trajectory from here isn't predetermined, but some likely paths are visible.

One possibility: the disruptions stabilize at a new equilibrium. Some research directions get permanently defunded or deprioritized. Some researchers emigrate but enough remain to maintain a functioning system. The NIH adapts to new leadership and new priorities. It's weakened compared to before, but it continues functioning.

Another possibility: the disruptions continue and intensify. More researchers leave. Advisory committees continue to lose members. Grant approval mechanisms further degrade. The institution spirals into dysfunction. Recovery becomes harder with each cycle.

A third possibility: political pressure reverses some of the disruptions. Congress, the courts, or political changes lead to restoration of funding and reinstatement of independence protections. The institution recovers some of what was lost.

None of these is assured. The outcome will depend on how people inside and outside the institution respond. If researchers keep leaving and leadership remains committed to current policies, scenario two becomes more likely. If political pressure builds for restoration, scenario three becomes possible.

What's clear is that the status quo before this disruption is not returning. Whether the outcome is a weakened but functioning institution, a severely damaged one, or a recovered one depends on choices that haven't been made yet.

FAQ

What caused the disruptions to NIH funding?

The disruptions resulted from new administrative policies implemented by NIH leadership in the current administration. These included systematic defunding of approved grants, termination of clinical trials, and implementation of ideology-based language screening that flagged research containing terms like "diversity," "climate change," and "health disparities."

How many research grants and clinical trials were affected?

According to the Senate investigation, the NIH terminated or froze approximately

What impact did the disruptions have on patients in clinical trials?

Patients enrolled in disrupted clinical trials were abruptly removed from ongoing treatment. Some were losing access to potentially life-saving treatments for which no alternative was available. Pediatric trials were particularly affected, with 69 children's trials being defunded, disrupting research into rare pediatric diseases and other childhood conditions.

Why are scientists considering emigrating?

Researchers are exploring positions abroad because of uncertainty about funding stability, concerns about ideological constraints on research questions, and because other countries (China, Germany, European countries) are actively recruiting American scientists with offers of better funding, more stable institutional environments, and fewer ideological restrictions on research directions.

What is the "ideology-based language screening" mentioned in the Senate report?

The NIH issued guidance directing staff to scan research proposals for certain words and phrases including "diversity," "climate change," "gender," "ethnic," "health disparities," and "environmental justice." Proposals containing these terms faced additional scrutiny or potential defunding based on framing rather than scientific merit.

Can disrupted research funding be restored?

Some funding has been restored, particularly after lawsuits forced the NIH to reverse decisions. However, the process is complicated by the fact that research institutions must navigate regulatory re-approval for studies that were halted, which can be lengthy and expensive. Full restoration would require political will and legislative action to prevent future disruptions.

What are the long-term consequences of this disruption?

Long-term consequences include delayed progress on treatments for major diseases, potential permanent loss of some research projects that were abandoned entirely, emigration of top scientific talent to other countries, weakening of the NIH's research portfolio, and potential loss of American scientific competitiveness as other countries invest in research capacity and recruit American researchers.

How does this compare to research disruptions in other countries?

Historical precedents include Britain's research disruptions in the 1990s, which led to a brain drain of scientists to the United States and required more than a decade of re-investment to recover. When research institutions become unstable or unattractive, talented researchers emigrate, and recovery takes years.

What would it take to reverse the damage?

Full recovery would require restoring all terminated funding, recruiting experienced researchers to vacant leadership positions, removing ideology-based language screening, explicitly committing to research independence, and actively recruiting back scientists who emigrated. This process would likely take years and require sustained commitment to research as a national priority.

Are there ongoing legal challenges to the NIH disruptions?

Yes, several lawsuits have been filed challenging the legality of defunding previously approved grants. Some have been successful in forcing the NIH to restore funding, indicating that some of the agency's actions exceeded its legal authority. Ongoing litigation is likely as more researchers and institutions challenge the disruptions.

Key Takeaways

- The Senate investigation documented $561 million in research grants terminated across cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer's, and diabetes research

- At least 304 clinical trials were defunded, including 69 pediatric trials, disrupting patient care and research progress

- The NIH implemented ideology-based language screening that flagged research terms like 'diversity' and 'climate change,' constraining research independence

- With 15 of 27 institute directors vacant and advisory committees losing members, the approval machinery for new grants faces significant gridlock

- Early-career researchers and top scientists are increasingly exploring positions abroad as China and Germany actively recruit American scientific talent

- Historical precedent from British research disruptions in the 1990s shows that brain drain from research crises takes a decade or more to recover from

- The gap between leadership claims and ground-level researcher experiences suggests broken institutional feedback mechanisms and communication systems

![Medical Research Crisis: Trump Administration's Impact on NIH [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/medical-research-crisis-trump-administration-s-impact-on-nih/image-1-1770237598231.jpg)