Meta's VR Studio Shutdowns: What Happened to Reality Labs [2025]

It's wild how fast things change in tech. Just a few years ago, Meta was pouring billions into the metaverse. The company acquired VR studios left and right, hired thousands of developers, and positioned itself as the future of computing. Then came 2024, and the whole narrative flipped.

In January 2025, Meta announced layoffs hitting about 10 percent of its Reality Labs division. But it wasn't just headcount reduction. The company straight-up shuttered entire game studios. Twisted Pixel Games, the team behind Marvel's Deadpool VR. Sanzaru Games, creators of the Asgard's Wrath franchise. Armature Studio, which ported Resident Evil 4 to VR. Gone.

This wasn't a quiet cleanup. Developers posted about it on LinkedIn, talking about unexpected closures and strategy shifts. The layoffs revealed something bigger: Meta's confidence in the metaverse bet was cracking. And if you're in tech, you saw this coming from a mile away.

But here's what most people missed. This shutdown tells us a lot about how Meta thinks about AR, VR, and the future of wearable tech. It's not just about killing a few studios. It's about a fundamental reset in how the company's approaching the next decade. Let's break down what actually happened, why it matters, and what it means for the entire VR industry.

TL; DR

- Meta shuttered three major VR studios: Twisted Pixel Games, Sanzaru Games, and Armature Studio were closed as part of Reality Labs layoffs

- 10% workforce reduction: The cuts hit the entire metaverse division, shifting focus from VR games to wearable technology

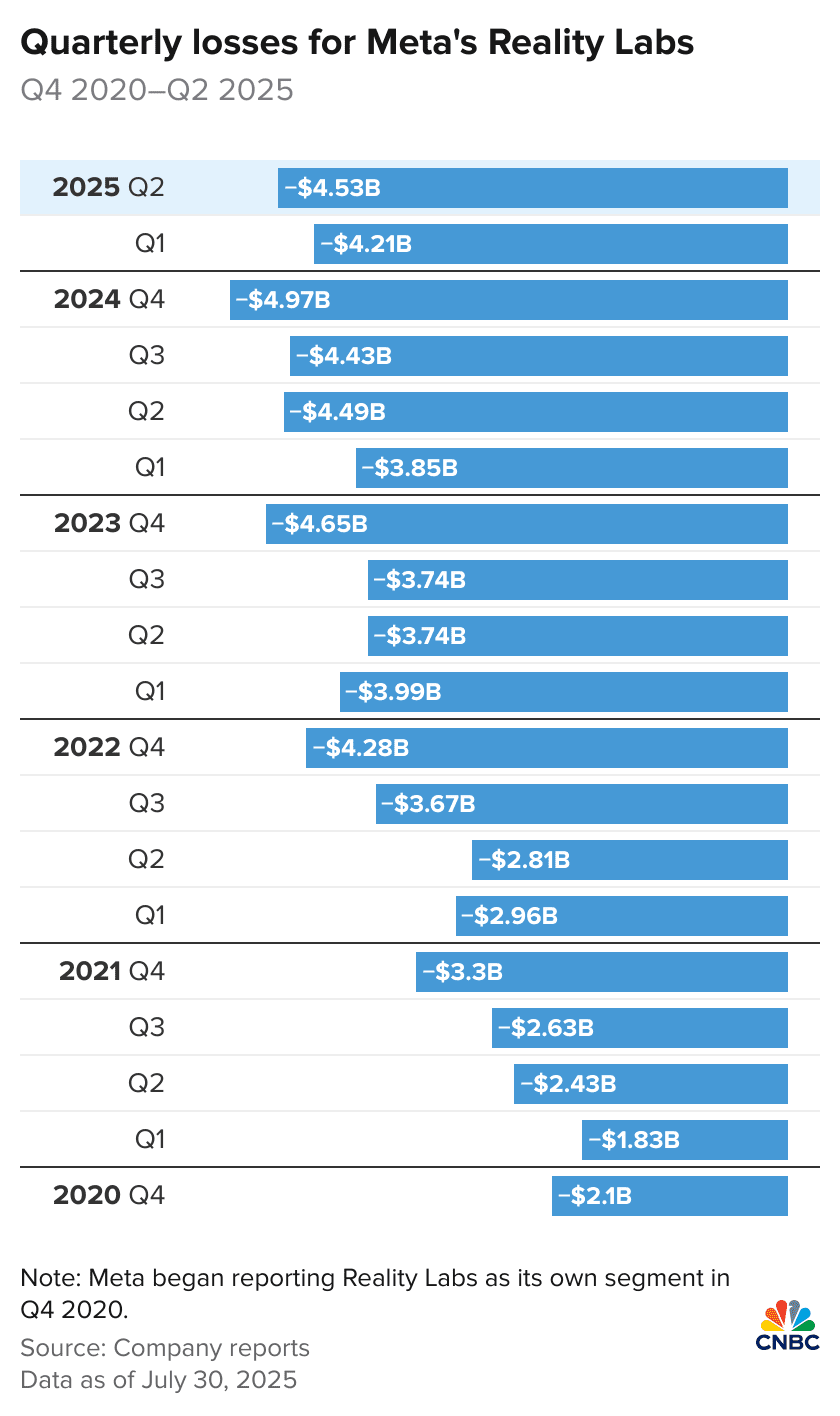

- Billions wasted: Meta's Reality Labs lost over $4 billion annually before the pivot, representing the largest corporate bet on metaverse tech

- Strategic shift confirmed: Meta explicitly stated it's moving investment from metaverse software toward wearables like AR glasses

- Industry implication: The shutdown signals that traditional VR gaming as Meta envisioned it isn't the path forward

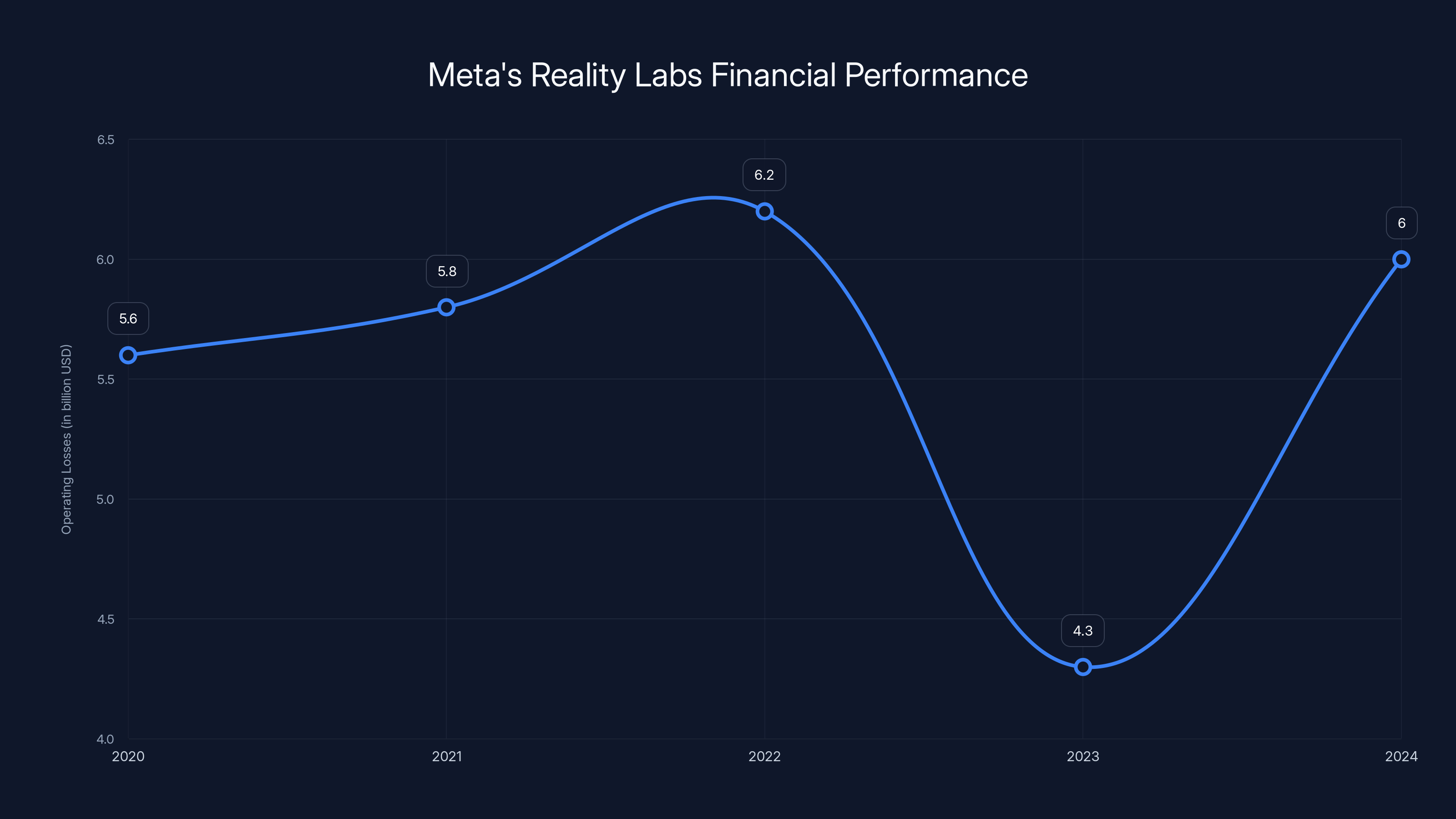

Reality Labs experienced significant financial losses from 2020 to 2024, with a notable dip in 2023, reflecting the challenges in consumer VR adoption and strategic pivots. Estimated data.

Meta's Metaverse Bet: The Biggest Gamble in Tech

Let's rewind a bit. In 2021, Mark Zuckerberg announced a company-wide pivot toward the metaverse. Not a side project. Not an experimental division. A full corporate transformation. Facebook was rebranding to Meta. The entire company's future would be built on virtual worlds.

Zuckerberg spoke about this with genuine conviction. He showed off VR prototypes, talked about digital avatars, and painted a vision of work, play, and social connection happening entirely in virtual spaces. The company committed to investing $10 billion annually into Reality Labs, the division responsible for building metaverse technology and VR products.

It sounded insane to most people. It probably was. But Meta had the cash flow to take the bet. And for a moment, it looked like it might work. The company started acquiring studios. Acquired Twisted Pixel in 2022 for an undisclosed amount. Bought Armature in 2022. Already owned Sanzaru from a 2020 acquisition. Meta was building a first-party VR game portfolio.

The problem wasn't imagination. It was consumer reality. VR adoption stayed flat. The Meta Quest platform, while dominant in the VR space, never became mainstream. Gaming remained niche. Enterprise applications moved slower than expected. And meanwhile, the company was burning money at an alarming rate.

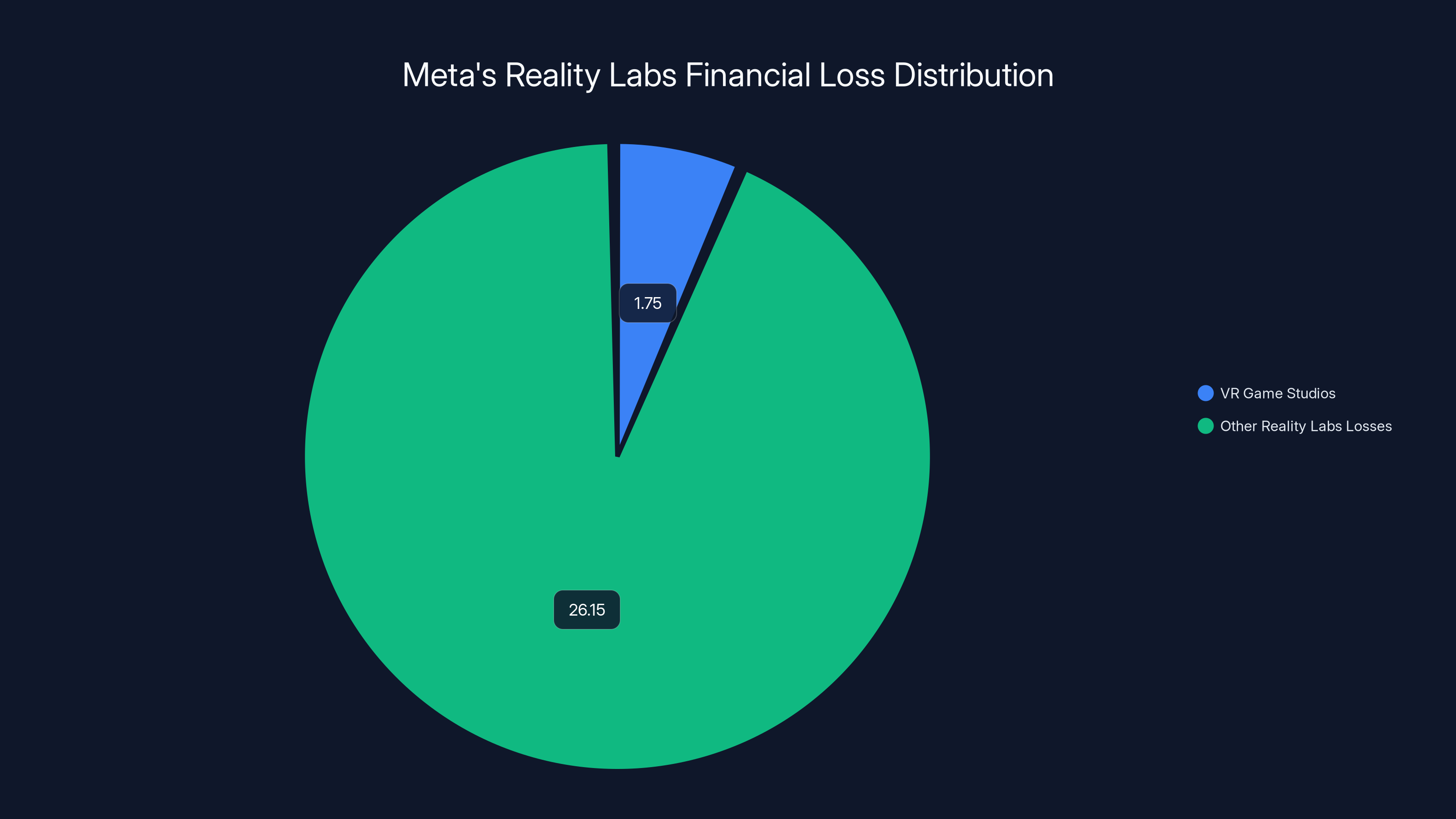

By 2023, things got uncomfortable. Reality Labs reported operating losses of $4.3 billion that year. The division consumed resources without generating meaningful revenue. Investors started asking hard questions. Board members questioned the strategy. Even inside Meta, some leaders started wondering if this was sustainable.

Then Elon Musk took over Twitter, laid off 50% of staff, and suddenly cost-cutting became the cool move in tech. Meta's leadership realized they had cover. They could dial back the metaverse bet without looking foolish. By mid-2024, Zuckerberg started talking about this mysterious shift to "wearables." Nobody quite knew what that meant. Now we do.

Meta's VR strategy involved acquiring studios like Ready at Dawn and others, but they were closed within 2-4 years, indicating challenges in sustaining VR gaming ecosystems. Estimated data.

The Studios That Died: Why These Three?

Twisted Pixel Games occupied a special place in Meta's VR portfolio. Founded in 2005, originally as a creative studio making games for Xbox, the team had serious pedigree. They built games like Splosion Man, which won indie game awards. By the time Meta acquired Twisted Pixel in 2022, the studio had pivoted to VR and was working on Marvel's Deadpool VR.

Deadpool VR wasn't just any superhero game. It was tied to the Deadpool movie franchises. Marvel partnered with Meta. The marketing budget was substantial. The game released in December 2024, just a month before the studio closure announcement. So Meta shut down the team right after shipping their marquee title. That's not how healthy studios operate.

Sanzaru Games had a longer history with Meta. The company acquired Sanzaru in 2020, before the full metaverse pivot. Sanzaru's biggest franchise was Asgard's Wrath, a first-person action game that actually impressed VR critics. The studio had released Asgard's Wrath 2 in late 2024. Two major releases in consecutive months, both within weeks of shutdowns.

Armature Studio was the quiet achiever. They weren't building original IP. Instead, they specialized in ports. Resident Evil 4 VR, for example. This work is technically demanding but less glamorous than original game development. Porting games to VR requires deep optimization knowledge. It's not trivial work.

Here's the thing. These weren't failed studios. They were shipping games. They had launched titles recently. They were executing on Meta's VR vision. The problem wasn't execution. The problem was that Meta didn't believe in VR gaming anymore.

When developers at these studios posted about the closures on LinkedIn, they didn't sound angry about poor performance. They sounded shocked. Andy Gentile, who worked at Twisted Pixel, said it was a "strategy change." That's the corporate version of "we're just done with this."

Dan Greenfield, a senior artist at Twisted Pixel, put it plainly: "Twisted Pixel Games has been closed as a result of strategy changes at Meta." Ray West from Sanzaru said "several Meta game studios were closed today." These weren't failing teams. They were casualties of a strategic reset.

The Pattern: Meta's History of VR Studio Closures

Twisted Pixel, Sanzaru, and Armature weren't the first VR studios Meta shuttered. In 2024, the company had already shut down Ready at Dawn, the developer of Echo VR. Ready at Dawn got acquired by Meta in 2020 for an undisclosed amount (likely over $100 million based on team size and track record). They spent four years building VR social experiences. Then Meta killed it.

Echo VR was actually pretty good. It was a zero-gravity multiplayer game that captured the unique potential of VR better than most titles. It had a dedicated community. But the community wasn't large enough. The player base wasn't converting to paid users at the rate Meta wanted. So Ready at Dawn, along with Echo VR, got discontinued.

This pattern reveals something important about Meta's VR strategy. The company wasn't building sustainable gaming ecosystems. It was chasing hits. It expected VR gaming to follow the mobile gaming model where one breakout title funds dozens of smaller projects. But VR gaming never developed that way.

Mobile gaming in 2012-2015 had Candy Crush, Clash of Clans, and similar titles generating billions. Those hits funded entire studios. VR gaming never had a comparable breakout. The biggest VR game, Beat Saber, was developed by Beat Games, a tiny Swedish team. Meta bought Beat Games too, so they owned the most successful VR game ever made. And they still couldn't build sustainable momentum.

The fundamental problem is that VR adoption plateaued. The installed base of VR headsets is maybe 50-100 million devices worldwide. Compare that to 3+ billion smartphones. The addressable market for VR games is maybe 5-10 million hardcore players. That's insufficient to support the kind of spending Meta committed to.

Consider the math. Meta acquired three major studios and funded them for 2-4 years. Salaries for game developers at established studios run

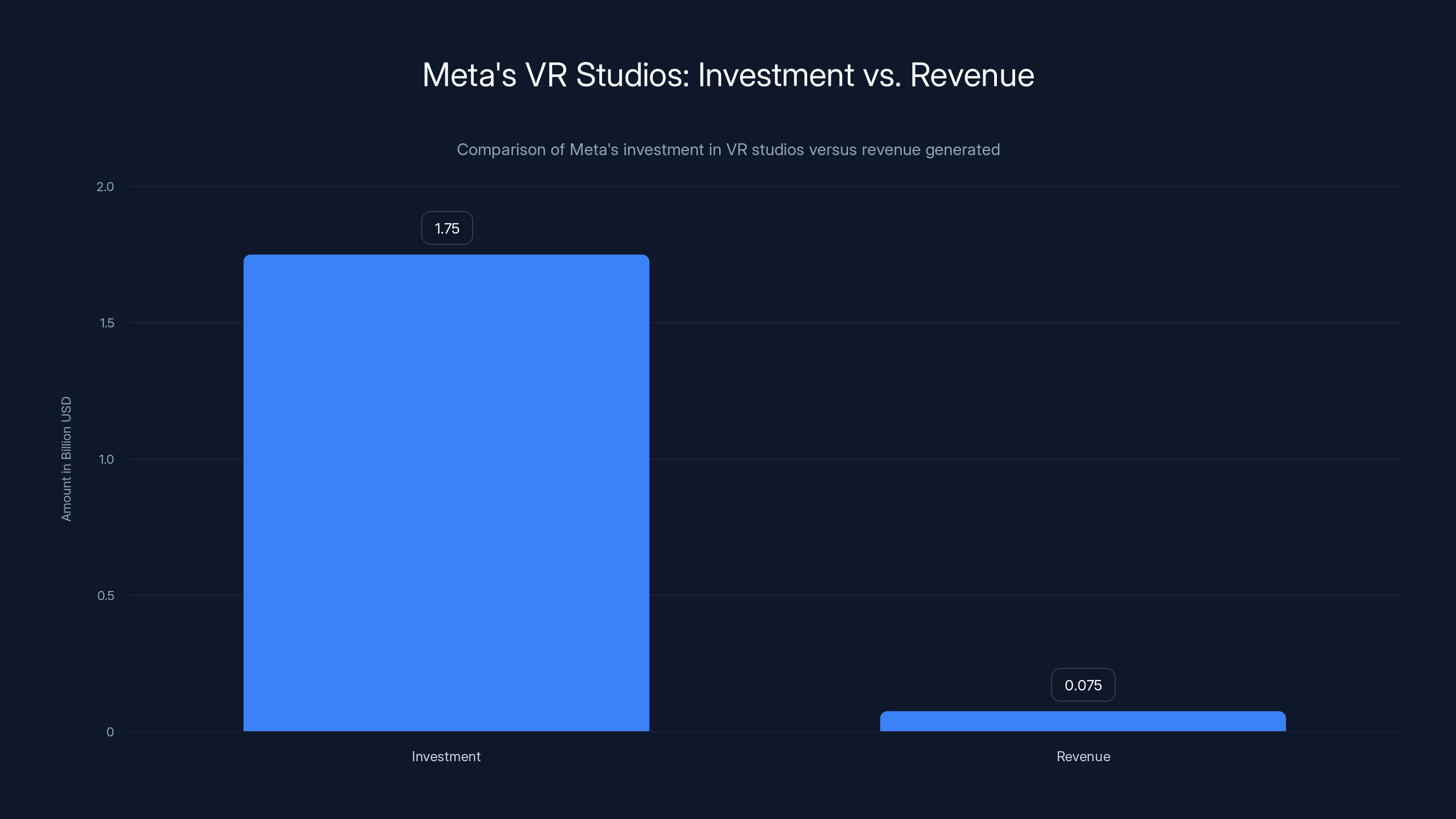

Meta spent roughly $1.5+ billion directly on these three studios and their games. Return on investment? Essentially zero. The games didn't define VR gaming. They didn't drive headset adoption. They didn't create franchise momentum.

Estimated data suggests hardware quality and software applications are critical for AR glasses success, with price and market demand also important.

Why the Metaverse Failed: The Hard Truth

It's worth asking directly: why did the metaverse bet fail? Zuckerberg's vision wasn't wrong about the direction of computing. Immersive environments will probably matter long-term. But the execution was fundamentally flawed. Let's break down the actual failures.

The Technology Adoption S-Curve Problem

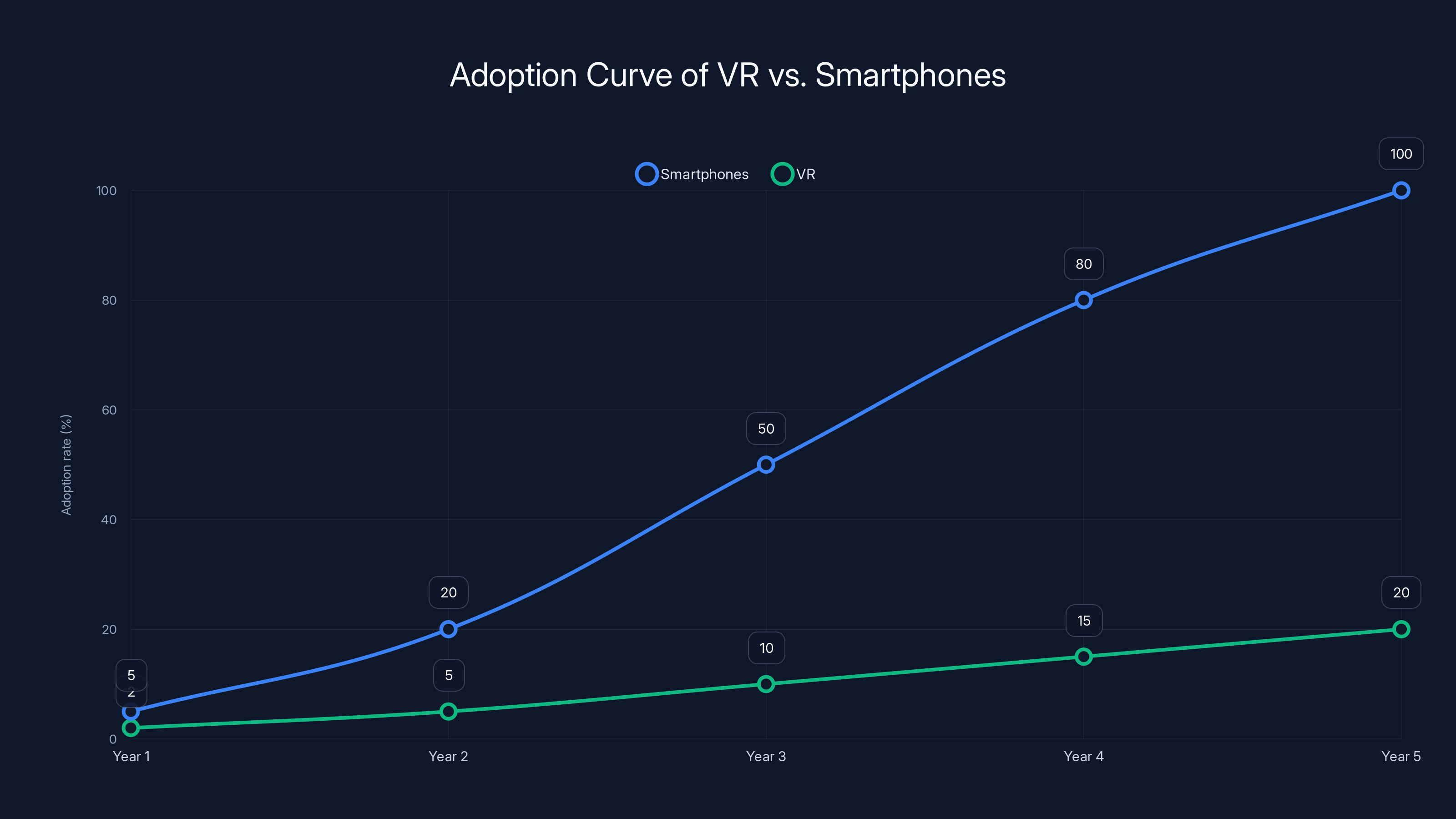

Meta miscalculated how VR technology would follow the adoption curve. The company assumed VR would follow smartphones: exponential growth, quickly reaching a billion users. But adoption curves aren't predetermined. They depend on whether the technology solves real problems better than alternatives.

Smartphones solved the problem of portable computing and communication. The value proposition was so strong that adoption accelerated rapidly. VR, by contrast, solves some entertainment and gaming problems, but not better than existing solutions. You can play games on a console or PC with better graphics, lower latency, and no headset discomfort. You can work on a computer. You can socialize on video calls.

The promised killer app for VR—social networking in virtual worlds—never materialized. Zuckerberg spent years talking about Avatar social experiences. He showed off Horizon Worlds, Meta's answer to Roblox or Decentraland. It was clunky, underwhelming, and failed to attract sustained user engagement.

The Hardware-Software Chicken-and-Egg Problem

VR faces a classic hardware-software dilemma. Developers need a large installed base to justify investment. Consumers need killer apps to justify buying hardware. Meta tried to solve this by funding software (games) while manufacturing hardware (Quest headsets). But funding software isn't the same as creating genuine hit software.

Meta threw money at the problem. More money than any company in history. Billions. And the software still didn't move the needle. Because money alone doesn't create hit games. Talent, luck, timing, and clear vision all matter. Meta had money but struggled with the other factors.

The best VR experiences actually came from smaller teams with specific visions. Beat Saber was created by a team of five. Half-Life: Alyx came from Valve, which has historically taken years to develop games but ensures quality. Smaller, more focused teams created better VR experiences than Meta's well-funded studios.

The Comfort and Friction Problem

There's a reason people don't wear VR headsets for hours. They're uncomfortable. Resolution is still below what our eyes need for perfect clarity. Latency causes motion sickness in some users. The visual field isn't 100% coverage. The weight distribution is awkward. Setting up VR requires open space.

Consumers tolerate these issues for novelty experiences. But for sustained use? They opt for alternatives. A tablet screen or laptop is less immersive but more practical. A smartphone is always accessible. AR glasses (if they ever become practical) would offer immersion without removing you from the real world.

Meta's bet was that these issues would be engineered away. And maybe they will be. But not on the timeline Zuckerberg expected. We're probably 5-10 years away from VR being genuinely comfortable for all-day use. Meta couldn't wait that long with billions being spent annually.

The Enterprise Bet That Didn't Materialize

Meta also bet that VR would transform enterprise software. Training, design, collaboration, and other business use cases. The company marketed VR hard to corporations. Some experiments happened. But enterprise adoption never reached meaningful scale.

Why? Because enterprises care about ROI on training spend. Most VR training isn't demonstrably better than alternatives in a business context. Safety training might benefit from simulation, but the cost premium for VR didn't justify the benefits in most cases. Design collaboration in VR sounds great until you realize that designers value precision tools more than immersion.

Meta realized that enterprise adoption would take even longer than consumer adoption. Meanwhile, the losses piled up.

The Wearables Pivot: What's Next for Meta

Now Meta is pivoting to wearables. Specifically, AR glasses. The company still has the Orion project in development—a full augmented reality glasses platform that overlays digital content on the real world. This is a smarter bet than the metaverse, though still speculative.

AR glasses, if they ever become practical, have clearer value propositions. Navigation, real-time information, hands-free computing, workplace assistance. These are genuinely useful. Unlike metaverse worlds, AR glasses solve real-world problems.

Meta spokesperson Tracy Clayton, in response to the layoffs, said: "We said last month that we were shifting some of our investment from Metaverse toward Wearables. This is part of that effort, and we plan to reinvest the savings to support the growth of wearables this year."

Translation: Meta is stopping its bet that VR would be the primary computing platform. It's betting on AR glasses instead. That's a smarter hedging strategy. The company keeps some VR focus (the Quest line) while investing more in AR glasses for the long term.

The question is whether Orion, Meta's AR glasses project, will be any more successful than the metaverse. Orion has been in development for years. The company showed prototypes with full displays, hand tracking, eye tracking, and AI assistance. Early reports suggest the hardware is impressive for its technical achievement. But technical achievement doesn't guarantee market success.

Apple's Vision Pro, released in early 2024, costs $3,500 and represents the state-of-the-art in immersive displays. It's impressive but hasn't sparked a revolution. Early reviews noted the high price, limited use cases, and the feeling that the technology is ahead of the software. Sound familiar?

Meta's AR glasses bet has similar challenges. The hardware might be good. But when? And will there be compelling applications? And at what price point? These questions remain unanswered.

Smartphones experienced rapid adoption reaching near saturation in 5 years, while VR adoption has been much slower, highlighting the challenges in achieving widespread acceptance. Estimated data.

What This Means for VR Gaming Industry

The shutdown of Twisted Pixel, Sanzaru, and Armature sends a clear signal to the VR gaming industry. Major publisher support is evaporating. If Meta, the company with the deepest pockets and strongest commitment to VR, is pulling back from game development, what does that mean for independent developers and smaller studios?

First, it means the days of billion-dollar bets on VR gaming are over. No other company has the resources Meta had. Sony, which makes PlayStation VR, has never committed comparable spending. Nintendo has shown zero interest in VR. Microsoft has mostly avoided it. Valve has made excellent VR games but as experiments, not core strategy. HTC Vive has focused on hardware, not software.

Second, it means the VR games market will contract. Less funding means fewer new releases. Some of the studios that survive will be those focused on niche markets (enterprise training), franchise extensions (Half-Life: Alyx model), or indie projects with passionate communities.

Third, it means the remaining VR game studios will likely be smaller and more focused. Instead of Meta's model—acquire established studios and have them work on VR versions of known franchises—the future of VR gaming probably involves smaller teams building original experiences for dedicated audiences.

Beats Saber, Pistol Whip, and Eleven Table Tennis (a VR ping-pong game) are good models. They're simple, elegant experiences that genuinely benefit from VR. They have sustained player bases. They didn't require billion-dollar budgets. They proved that good VR games don't need AAA budgets.

The developers from Twisted Pixel, Sanzaru, and Armature will find new homes. Some will join other VR studios. Some will move to mobile games or console development. Some will pursue indie projects. The talent doesn't disappear. But the institutional knowledge and the momentum these studios built does.

Longer term, VR gaming will exist. But it'll be smaller, leaner, and less capital-intensive than the metaverse era imagined. That might actually be healthier for the industry. Companies like Valve, which approaches VR games carefully and deliberately, might have had the right philosophy all along.

The Broader Tech Industry Implications

The Meta shutdown matters beyond VR gaming. It's a signal about how big tech companies think about long-term bets. And the signal is mixed.

On one hand, it shows disciplined capital allocation. Meta spent too much on too uncertain a bet. When the evidence suggested the bet wasn't working, the company corrected course. That's better than continuing to throw money at a failing strategy indefinitely. Companies like Alphabet and Microsoft have shown similar willingness to kill projects that aren't working.

On the other hand, it shows that billion-dollar pivots in tech are incredibly risky. Zuckerberg made a company-wide bet that turned out wrong. Shareholders accepted $27.9 billion in cumulative losses before the course correction. That's a massive cost for being wrong about a technology trend.

For founders and investors, the lesson is clear: be careful about company-wide pivots toward speculative technologies. Hedge your bets. Keep the core business healthy while exploring new directions. Don't go all-in on a single vision of the future, no matter how compelling the pitch.

For employees, the lesson is similarly clear. When a mega-corporation makes a dramatic strategic shift, watch for upcoming layoffs. The company will likely spin it as "optimization" or "efficiency improvements." But it's really a reset. And resets are often painful for rank-and-file workers.

Meta invested approximately

What Happened to Each Studio: Individual Stories

Behind the corporate announcement were hundreds of people. Let's look at what we know about what happened to each team.

Twisted Pixel Games

Twisted Pixel was the oldest studio Meta acquired (acquisition announced in October 2022). The team had shipped Marvel's Deadpool VR just weeks before the shutdown. By all accounts, the game met technical quality standards. The Marvel partnership was solid. The game had positive reviews.

Then Meta decided to close the entire studio.

People who worked there described it as a shock. The studio had just shipped a major release. They were supposedly working on additional Marvel content. And suddenly they got the news the studio was done.

Based on reports from former employees, about 150 people worked at Twisted Pixel. Most of those people were laid off with severance. Some might be retained in other Meta divisions, but that's unclear.

The team's next moves varied. Some went indie. Some joined other game studios. Some left the industry entirely. This kind of disruption is exactly why talent dispersal, not retention, is a common outcome of major studio closures.

Sanzaru Games

Sanzaru had a longer history with Meta. Acquired in July 2020, the studio had built Asgard's Wrath as its flagship franchise. The original shipped in 2019 (before Meta ownership) and was one of the best-reviewed VR games ever made. Asgard's Wrath 2 launched in December 2024, weeks before the shutdown.

Sanzaru, which is based in San Francisco, had probably 100-150 people. All of them faced layoff. The timing was brutal: the studio had just shipped its biggest project.

Sanzaru occupied an interesting position. Unlike some studios focused on licensed IP, Sanzaru owned the Asgard's Wrath franchise. The original game was developed before Meta ownership. Meta acquired the studio partly to own that IP. And then killed the studio that created it.

What happens to Asgard's Wrath now? It's unclear. The franchise probably has royalty holders and various stakeholders. A third game in the series seems unlikely. More likely, the franchise goes dormant or is shelved entirely.

Armature Studio

Armature was the least well-known of the three studios among consumers. Founded in 2008, Armature specialized in game porting and technical work. They're probably best known for porting Resident Evil 4 to VR, which was a technical marvel but probably sold in limited numbers.

Armature, based in Austin, Texas, was smaller than the other two studios (probably 50-80 people). They were part of Meta's strategy to bring premium console games to VR. The hypothesis was that iconic franchises like Resident Evil would drive VR adoption.

They didn't. Resident Evil 4 VR sold decently as a novelty but never reached mass market appeal. And Capcom (the franchise owner) probably made most of the money on the arrangement.

Armature's team dispersed into the industry. Porting skills are valuable. Many of the engineers probably found new homes at other game companies.

The Economic Impact: $1.5+ Billion Gone

Let's be direct about the economics of this decision. Meta spent billions acquiring and operating these studios. What was the return?

Twisted Pixel's Marvel's Deadpool VR probably sold fewer than 500,000 copies. At

Total revenue from these studios' software: probably

That's not acceptable for a company, even a mega-corp like Meta. Investors were already critical of the metaverse spending. This performance would have eventually triggered questions.

Alternatively, Meta could have kept these studios running with the hope that some future title would become a hit. But that's a speculative bet on a speculative market. Meta chose to cut its losses and redeploy the capital.

Capital redeployment is important. The $300+ million annually that Meta was spending on these studios will supposedly go toward AR glasses development. That's at least a more focused bet than the broad metaverse pivot.

An estimated

Lessons for Tech Companies: How to Approach Speculative Bets

The Meta metaverse story offers important lessons for how tech companies should approach speculative technology bets. These lessons apply to any emerging technology: AI, quantum computing, extended reality, etc.

Lesson 1: Don't Go All-In on a Single Vision

Zuckerberg's biggest mistake wasn't choosing the metaverse. It was betting the entire company's future on it. The company should have maintained a diversified portfolio. Core social media business. Some advertising innovation. Some AI research. Some VR exploration. Some AR exploration. Some other emerging tech experiments.

Instead, Meta signaled that the metaverse was THE future. That commitment attracted capital, talent, and expectations. When the bet didn't pan out, the company looked foolish. A smaller, quieter AR/VR research division wouldn't have generated the same backlash.

Lesson 2: Bet on Capabilities and Platforms, Not Games

Meta's strategy of acquiring game studios assumes that hit games drive platform adoption. That's true in mobile (Candy Crush drove iPhone adoption). But it's not necessarily true for immersive tech. People don't buy VR headsets because of Deadpool VR.

A smarter approach: bet on the underlying platform and tools. Fund VR development tools and engines. Create frameworks that make VR game development easier and cheaper. Build middleware that solves common VR problems. That creates conditions for third-party developers to build hit games. You don't have to do it yourself.

Valve sort of took this approach. They released SteamVR as an open platform and Half-Life: Alyx as an example of what VR could be. They didn't try to create an entire portfolio of games. They created the conditions for others to do so.

Lesson 3: Set Clear Metrics for Success (and Failure)

Meta never publicly stated what success for the metaverse would look like. How many monthly active users? What revenue target? What timeline? Without those metrics, it's impossible to know when to double down versus when to pivot.

A better approach: "We'll spend $X billion on metaverse for Y years. If we don't reach Z million users by 2027, we'll reassess." Clear metrics force hard decisions. They prevent indefinite spending on failed bets.

Lesson 4: Keep Speculative Bets Separate from Core Business

Meta's problem was partly organizational. The metaverse was central to the company's identity. That created pressure to make it work, even as evidence suggested failure. A better structure: Alphabet's model, where experiments and new bets are in separate companies (X Development Lab) with different capital structures and evaluation criteria.

Google Cloud is starting to generate real revenue and value. But it's never distracted from Google's core search business. That separation allows each business to operate with appropriate risk tolerance.

The Future of VR After Meta's Retreat

So what's next for VR gaming? Several scenarios are plausible.

Scenario 1: Smaller, More Sustainable Market

VR gaming shrinks to a sustainable size. Core audience of maybe 5-10 million players worldwide. Handful of major studios (Valve, Ubisoft's VR division if it exists). Many indie developers. Limited AAA support. This is probably the most likely scenario.

In this world, VR games are niche but thriving. They're not mainstream gaming, but they're a recognized category. Kind of like fighting games or roguelikes. Smaller audience but dedicated and valuable.

Scenario 2: Apple or Microsoft Enters with Force

One of the other mega-cap tech companies decides VR is important and invests heavily. Apple is the most likely candidate. Apple has shown interest in immersive computing (Vision Pro). If Apple decides to build an ecosystem of VR games, it has the resources and reputation to shift the market.

But Apple would need to solve the same problems Meta couldn't solve. And Apple's premium pricing strategy might limit addressable market. This scenario is possible but uncertain.

Scenario 3: VR Becomes Genuinely Mainstream

Hardware improvements (resolution, latency, comfort) reach a threshold where VR becomes genuinely comfortable for all-day use. Price point drops below $300. Software quality reaches parity with traditional gaming. Killer app emerges that drives adoption.

This would vindicate Zuckerberg's vision. But it probably takes 5-10+ years. Meta couldn't wait. This scenario is possible but happened later than expected.

Scenario 4: AR Glasses Replace VR

AR glasses become practical before VR becomes mainstream. People adopt AR glasses for navigation, information, and communication. Immersive gaming becomes a secondary feature of AR glasses rather than the primary use case of VR headsets.

Meta is betting on this scenario. It's actually pretty plausible. AR has clearer near-term value propositions than VR. And if AR glasses work well, they might obsolete VR for most use cases.

Expert Perspectives on What Went Wrong

VR researchers, industry analysts, and former executives have weighed in on what went wrong with the metaverse bet.

The Technology Perspective

VR technologists generally agree that the hardware is on a good trajectory. Resolution, refresh rates, processing power, and other metrics are improving. But the improvements are evolutionary, not revolutionary. Real comfort and practicality for all-day wear is still probably 5-10 years away.

The software problem is harder. Creating compelling immersive experiences is genuinely difficult. Motion sickness is real. Motion capture quality is still limited. AI-driven NPCs in VR are less convincing than in traditional games.

The Business Perspective

Venture capitalists and business analysts point out that Meta confused having money with understanding markets. Spending billions doesn't change fundamental market dynamics. If consumers don't want something, they won't want it even if a billionaire offers it for free.

Meta's error was assuming that supply creates demand. Build enough great VR games, and people will buy headsets. Reality: people buy technology that solves real problems or provides entertainment that's better than alternatives. VR games are interesting but not obviously better than alternatives at current price points.

The Investor Perspective

Investors are relieved. The metaverse bet was costing Meta too much. The company's earnings were suppressed by Reality Labs' losses. The pivot allows Meta to show better profitability. Shareholders won. Metaverse believers lost.

But investors also noted that this shows the risk of founder-driven strategy. When a founder has a clear vision but limited accountability to market feedback, massive bets on uncertain futures can happen. It's not necessarily a bad thing (ambitious bets drive progress). But it's risky.

What Did Work: VR's Actual Successes

Not all of Meta's VR efforts were failures. Some things genuinely worked.

Beat Saber

Beat Saber remains the best-selling VR game of all time. Over 5 million copies sold across platforms. The game showed that VR could drive hardware adoption. People bought headsets specifically to play Beat Saber.

Meta acquired Beat Saber (via acquisition of Beat Games in 2021). The game continues to sell and generate revenue. It has a dedicated community. New songs are released regularly. This is the one bright spot in Meta's VR gaming portfolio.

Half-Life: Alyx

Valve's Half-Life: Alyx (2020) showed that AAA development could work in VR. It had cutting-edge graphics, a compelling story, and genuinely innovative VR interactions. It didn't sell massive numbers (probably 2-3 million copies), but it proved that big-budget VR games could work.

Meta didn't develop this game, but it validated the market for high-end VR experiences. Alyx showed that gamers would play VR if the quality and experience justified it.

Enterprise Applications

While Meta's enterprise bet didn't pan out as hoped, some VR applications genuinely provide value. Medical training, architectural visualization, and safety simulation are areas where VR offers genuine advantages. These applications didn't drive Meta's numbers, but they represent where VR actually provides value.

Hardware Sales

Meta Quest headsets are reasonably successful. Probably 5+ million units sold cumulatively. The Quest 3 and Quest 3S represent solid products at reasonable prices. For those who want to enter VR, Meta's hardware is a good option. The problem is that "those who want to enter VR" remains a small number.

The Human Cost: What Happens to Displaced Workers

Behind the corporate announcements are hundreds of people who lost jobs. That's worth taking seriously.

Layoffs at game studios are particularly painful. Game developers often accept lower salaries because they work on projects they love. They relocated to work at specific studios. They built professional relationships. The sudden closure breaks that.

For developers with 5-10 years of experience (common in Meta's studios), finding new jobs is usually possible but uncertain. Some will find roles at other game studios. Some will move to different technology sectors. Some might take time off or pursue other careers.

For junior developers, the situation is harder. They might lose their first significant job experience. For mid-career developers, relocation might be necessary. For senior developers, finding comparable roles in other studios might require accepting less prestigious or well-funded positions.

Severance softens the blow. Meta almost certainly provided severance packages, probably 3-6 months of salary plus benefits continuation. That's more than many companies offer. But severance isn't a substitute for good faith employment.

There's also an opportunity angle. Displaced game developers are talented. They can build indie games, join smaller studios, or shift to other tech sectors. Some of the best indie games come from people who were part of failed corporate initiatives. The creativity and frustration sometimes produces better work.

Industry-Wide Reactions and Ripple Effects

The shutdown of Meta's studios sent ripples through the gaming and VR industries.

Other VR Studios Watching Closely

Smaller VR studios took note. The message was clear: if Meta is pulling back, where's the stability? Several VR studios had been waiting for Meta to prove the market before investing heavily. The shutdown confirmed their worst fears. VR market growth is slower than hoped.

This probably led some VR studios to pivot or shut down. Others to focus on niche markets. Some to bet on AR instead. The psychological impact matters. Meta's confidence in VR was higher than market reality, but it was still significant. Without Meta's backing, VR looks riskier.

Implications for Other Platforms

Sony (PlayStation VR), Valve (SteamVR), and HTC (Vive) all benefited indirectly from Meta's retreat. Less competition for consumer VR attention. Smaller chance that a major competitor dominates the market. These platforms can focus on their existing communities without racing Meta's billion-dollar spend.

Implications for AI and Emerging Tech

Big tech companies watched the Meta situation carefully. The lesson: billion-dollar bets on speculative technology are risky. If Meta, with better execution and more money than anyone else, couldn't make the metaverse work in the timeframe they expected, what does that say about other long-term bets?

You see this playing out in AI. Companies are being more cautious about AI investments. More focus on near-term ROI. Less appetite for speculative multi-billion-dollar bets. That's not necessarily bad. It forces more careful thought about how to deploy capital.

What We Can Learn About Technology Adoption

The Meta metaverse story is really a story about technology adoption. Why do some technologies explode into mainstream use while others remain niche? What determines success?

Historically, successful technologies solved clear problems for a large number of people. Smartphones solved the problem of portable computing and communication. Email solved the problem of asynchronous written communication. The internet solved the problem of global information access.

VR solves... gaming entertainment? Some training applications? Entertainment experiences that are better accessed through flat screens or mobile? The value proposition is weak. That's not Zuckerberg's fault. It's just the fundamental reality of where the technology is.

There's a concept in technology adoption called the "chasm." Technology might appeal to early adopters but fail to cross into mainstream adoption. The chasm exists because early adopters care about novel features, while mainstream users care about solving real problems at reasonable cost.

VR is stuck in the chasm. Early adopters love it. But mainstream users see it as expensive, uncomfortable, and solving problems they don't have. No amount of money changes that. You have to solve the fundamental problems: comfort, cost, compelling use cases.

Meta tried to throw money at the chasm. Better hardware (Quest 3S at reasonable price). Better software (funding major studios). Better content (exclusive titles). But the chasm doesn't close until underlying problems are solved. And VR's underlying problems (comfort, limited use cases, motion sickness, high barrier to entry) require technological progress, not just funding.

The Future: Where Is Immersive Tech Heading?

So what actually happens with immersive tech going forward? Based on the Meta situation and broader tech trends, here's what seems plausible.

VR as a Niche but Viable Category

VR probably becomes like flight simulation or racing games. Niche categories with passionate communities. Not mainstream gaming, but recognized and valued. Consoles and PCs include VR support. Indie developers create interesting VR experiences. But VR isn't the center of gaming.

This scenario is already playing out. The VR game market is maturing. Growth rates are slowing. Player bases are stabilizing around core audiences. New games are released regularly but aren't culture-shifting hits. It's a viable market, just not a revolutionary one.

AR Glasses as the Dominant Immersive Form Factor

AR glasses, if they achieve product-market fit, will probably be more significant than VR. Why? Because they don't require removing yourself from reality. Navigation, real-time information, hands-free communication, workplace assistance—these are genuinely valuable. And they don't require the immersion that VR demands.

Apple's Vision Pro showed that the technical challenges of AR glasses are solvable. The remaining question is cost, comfort, battery life, and killer applications. If AR glasses become practical and affordable, they could become as ubiquitous as smartphones.

Meta is betting on this with Orion. The company has shifted strategy from "VR is the future" to "AR glasses are the future." If this bet works, it vindicates the company's long-term thinking while admitting that the timeline was wrong.

Mixed Reality for Enterprise and Specialized Verticals

Mixed reality (blending digital and physical) will probably find homes in specific verticals. Medical (surgical assistance), engineering (design visualization), military (tactical information), industrial (manufacturing support). These are areas where the value prop is clear.

Meta's enterprise push missed because the value props weren't clear for most businesses. But in specialist domains, immersive technology offers real advantages. This is probably where the profitable part of VR/AR ends up.

Gaming as a Secondary Use Case

Gamers will use VR, AR, and mixed reality, but not as primary reasons to adopt. Gaming will be a feature of larger devices, not the whole point. Just like gaming was a feature of smartphones, not why people bought smartphones.

This is a radical shift from Meta's metaverse vision, where gaming was supposed to drive adoption. In the future, gaming is more likely a nice-to-have feature of AR glasses rather than the killer app.

FAQ

What happened to Meta's VR studios?

Meta closed three major VR game studios in January 2025: Twisted Pixel Games (developer of Marvel's Deadpool VR), Sanzaru Games (creator of Asgard's Wrath), and Armature Studio (which ported Resident Evil 4 to VR). The closures were part of a broader 10 percent workforce reduction in the Reality Labs division as Meta shifted strategic focus from metaverse software toward wearable technology and AR glasses.

Why did Meta close these studios if they just shipped games?

Meta's shutdown of these studios wasn't based on individual game performance. Rather, it reflected a company-wide strategic reset. Meta explicitly stated it was "shifting investment from Metaverse toward Wearables." The studios' games (Deadpool VR, Asgard's Wrath 2) had shipped weeks prior, but the company had concluded that VR gaming wasn't delivering sufficient return on investment to justify ongoing funding. The reality was that Meta's VR gaming bet—costing billions over multiple years—hadn't generated mainstream adoption or revenue proportional to the investment.

How much money did Meta lose on VR?

Meta's Reality Labs division lost approximately

Is VR gaming dead?

VR gaming isn't dead, but it's resetting to a more sustainable market. VR gaming will likely remain a niche but viable category with 5-10 million core players worldwide, indie developers, smaller studios, and specific vertical applications. The difference is that the era of multi-billion-dollar publisher bets on VR gaming as a mainstream category is over. VR will be more like flight simulators or roguelike games—valued by enthusiasts but not culture-shifting.

What is Meta doing instead of the metaverse?

Meta is pivoting toward AR (augmented reality) glasses, primarily through its Orion project. The company believes AR glasses have clearer value propositions (navigation, real-time information, hands-free communication) than VR. The shift reflects acknowledgment that achieving mainstream VR adoption will take longer than the company's capital and patience allow. AR glasses, if they achieve product-market fit, could be more broadly useful because they don't require removing users from the physical world.

What happens to the developers who lost their jobs?

The approximately 300-400 developers across the three closed studios faced layoffs with severance packages (typically 3-6 months of salary plus benefits continuation). Many found roles at other game studios, indie ventures, or different tech sectors. Some left the industry entirely. While severance softens the blow, sudden studio closures are disruptive to careers and require significant job searching and potential relocation.

Could VR gaming make a comeback?

Yes, VR gaming could gain momentum if three conditions align: hardware becomes significantly more comfortable for all-day use (probably 5-10 years away), killer applications emerge that justify adoption (unclear what these would be), and prices drop below $250-300 for mainstream accessibility. However, VR is unlikely to return to the scale of Meta's ambitions. The technology is improving, but the fundamental barrier—unclear value proposition for mainstream consumers—remains unsolved.

What does this mean for Apple and Microsoft in immersive tech?

Meta's retreat creates opportunity for other companies. Apple's Vision Pro and Microsoft's HoloLens efforts are less directly competitive if Meta is deprioritizing VR games. However, Apple and Microsoft face similar challenges: high prices, limited compelling applications, and unclear mainstream value propositions. The Meta situation suggests that size and capital alone don't guarantee success in immersive technology markets.

Is the metaverse concept completely abandoned?

Meta hasn't abandoned immersive technology entirely, just the specific "metaverse worlds" concept that dominated messaging from 2021-2023. The company still develops VR hardware (Quest line), still invests in AR/mixed reality, and still explores virtual experiences. But the grand vision of living and working primarily in virtual worlds has been shelved. Instead, the company is hedging on AR glasses as the next computing platform.

What should game developers do in light of these closures?

Game developers should recognize that mega-corporation backing for VR gaming is less certain than previously assumed. Viable strategies include: focusing on indie projects with dedicated audiences, developing VR training/enterprise applications rather than games, building for multiple platforms (VR as a feature, not the primary product), and preparing to pivot if platform politics change. The era of assuming VR would achieve mainstream adoption by 2025 has clearly ended.

Conclusion: The End of the Metaverse Era

Meta's shutdown of Twisted Pixel, Sanzaru, and Armature Studios marks a symbolic end to the metaverse era. It's not the end of VR, AR, or immersive computing. But it is the end of the idea that virtual worlds would become humanity's primary computing platform by 2025.

Zuckerberg's metaverse bet was ambitious, well-funded, and ultimately mistaken. Not about the long-term importance of immersive technology. But about the timeline and approach. The company went all-in on a speculative future while the present was still being built. That's a risky strategy for a mega-corporation with existing profitable businesses.

The fundamental lessons are simple but important. First, technology adoption timelines are harder to predict than business plans suggest. Second, capital alone doesn't create market demand. Third, founder-driven strategies are powerful but risky. Fourth, long-term bets on speculative tech require institutional patience and clear success metrics.

Meta had the capital, talent, and will to make the metaverse work if it were workable. That it didn't work suggests the bet was fundamentally flawed, not just misexecuted. That's worth learning from.

For VR and immersive technology, the shutdown is actually probably healthy. It forces clarity about what actually works. Beat Saber works. Half-Life: Alyx works. Enterprise VR applications work. Generic metaverse gaming doesn't. The industry can now focus on what works rather than chasing a vision that consumers never embraced.

For Meta, the pivot to AR glasses is smarter. AR has clearer value propositions. It doesn't require immersion. It could integrate with daily life rather than replacing it. If Orion succeeds where Quest failed, the company will have learned an expensive lesson but positioned itself for the next computing era.

But that's still years away. In the near term, Meta's VR gaming bet is finished. The studios are closed. The games will become abandonware as support and updates cease. The developers will find new homes. And the VR industry will continue on without the massive financial backing that Meta provided.

That's not a tragedy. It's just business correcting course when a bet doesn't work out. The companies and people involved will move forward. The technology will continue improving. And maybe, eventually, AR glasses or some other form of immersive computing will achieve the mainstream adoption that VR never did.

But that story is still being written. For now, we're just seeing the end of the metaverse dream as originally imagined.

Key Takeaways

- Meta shut down three major VR studios (Twisted Pixel, Sanzaru, Armature) as part of a strategic pivot away from metaverse software toward wearable technology

- The company lost 4-5 billion annually in losses before the course correction

- VR gaming adoption plateaued despite billions in funding, mega-studio acquisitions, and exclusive franchises, indicating fundamental market timing issues not just execution problems

- Meta's shift to AR glasses represents acknowledgment that the metaverse vision was incorrect on timeline and approach, though immersive technology remains strategically important

- The closure signals the VR gaming industry will contract to a sustainable niche market rather than mainstream adoption, affecting studios, developers, and future funding patterns

![Meta's VR Studio Shutdowns: What Happened to Reality Labs [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-vr-studio-shutdowns-what-happened-to-reality-labs-202/image-1-1768331411522.jpg)