Microdosing for Depression: What Science Really Shows About This Biohacking Trend

About ten years ago, something strange started happening in Silicon Valley and beyond. CEOs, novelists, and wellness enthusiasts began taking tiny, almost homeopathic doses of LSD or psilocybin mushrooms. Not to trip out. Not to hallucinate. But to feel... slightly better. A little sharper. Maybe less depressed.

The pitch sounded almost too good to be true. A fraction of a psychedelic dose—we're talking 5 to 20 micrograms of acid, when a typical recreational dose runs 100 micrograms or more—could supposedly unlock focus, creativity, emotional stability, and mood improvement. No melting walls. No kaleidoscopic visions. Just a gentle cognitive and emotional lift. It became the biohacking equivalent of nootropics: a secret weapon for optimizing human performance.

Media outlets jumped on it. Podcasters raved about it. Anonymous Reddit threads documented rituals and protocols. The narrative was compelling: psychedelics weren't just for weekend adventures anymore. They were tools for self-improvement. Medicine, practically.

But what if that entire narrative was built on a foundation of wishful thinking?

A new clinical trial from an Australian biopharma company has landed a potential bombshell in the microdosing conversation. The study suggests that when you control for expectation and belief, microdosing LSD for depression performs worse than a placebo. Not just marginally worse. Demonstrably, statistically worse.

Here's what that actually means. Why it matters. And what it tells us about the power of belief in medicine.

The Rise of Microdosing: From Fringe Experiment to Mainstream Biohacking

Microdosing didn't emerge from a research lab. It emerged from online forums, underground networks, and the kind of trial-and-error experimentation that happens when people feel like conventional medicine has failed them.

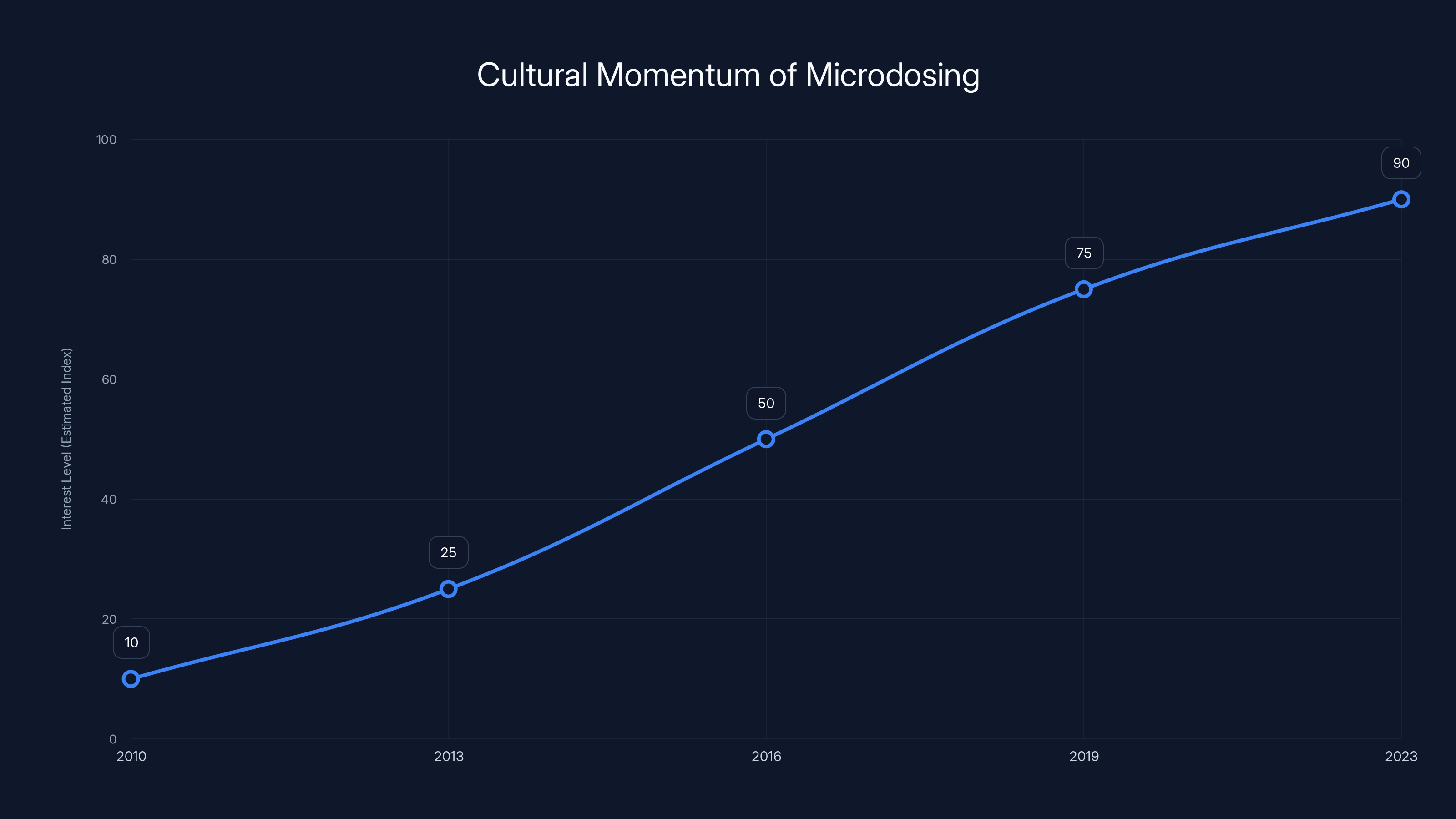

The practice gained cultural momentum in the early 2010s. People experimenting with very small doses of psilocybin or LSD reported improved mood, reduced anxiety, sharper thinking, and better problem-solving abilities. These weren't scientific claims. They were personal testimonies. But in the absence of rigorous research, these stories took on outsized influence.

Why? Because the people sharing these stories often had authority and platforms. Entrepreneurs reported that microdosing improved their strategic thinking. Artists said it enhanced creativity. Professionals claimed it helped with depression when SSRIs and talk therapy hadn't. The narrative was seductive: illegal drugs, used properly and carefully, could be better than legal medicine.

Media coverage amplified this. Major publications ran stories about the phenomenon. Some framed it optimistically. Some cautiously. But all of them helped establish microdosing as a real "thing" that people were actually doing, with apparent benefits.

Here's the critical problem: anecdotal reports are terrible evidence. A person feels better after microdosing. But did they feel better because of the drug? Or because they expected to feel better, and that expectation itself created the improvement? Or because they were doing something intentional about their mental health, which itself has psychological benefits? Or because placebo effects in the context of psychedelics can be remarkably powerful?

Without a control group, you can't tell. And that's where the science gets interesting.

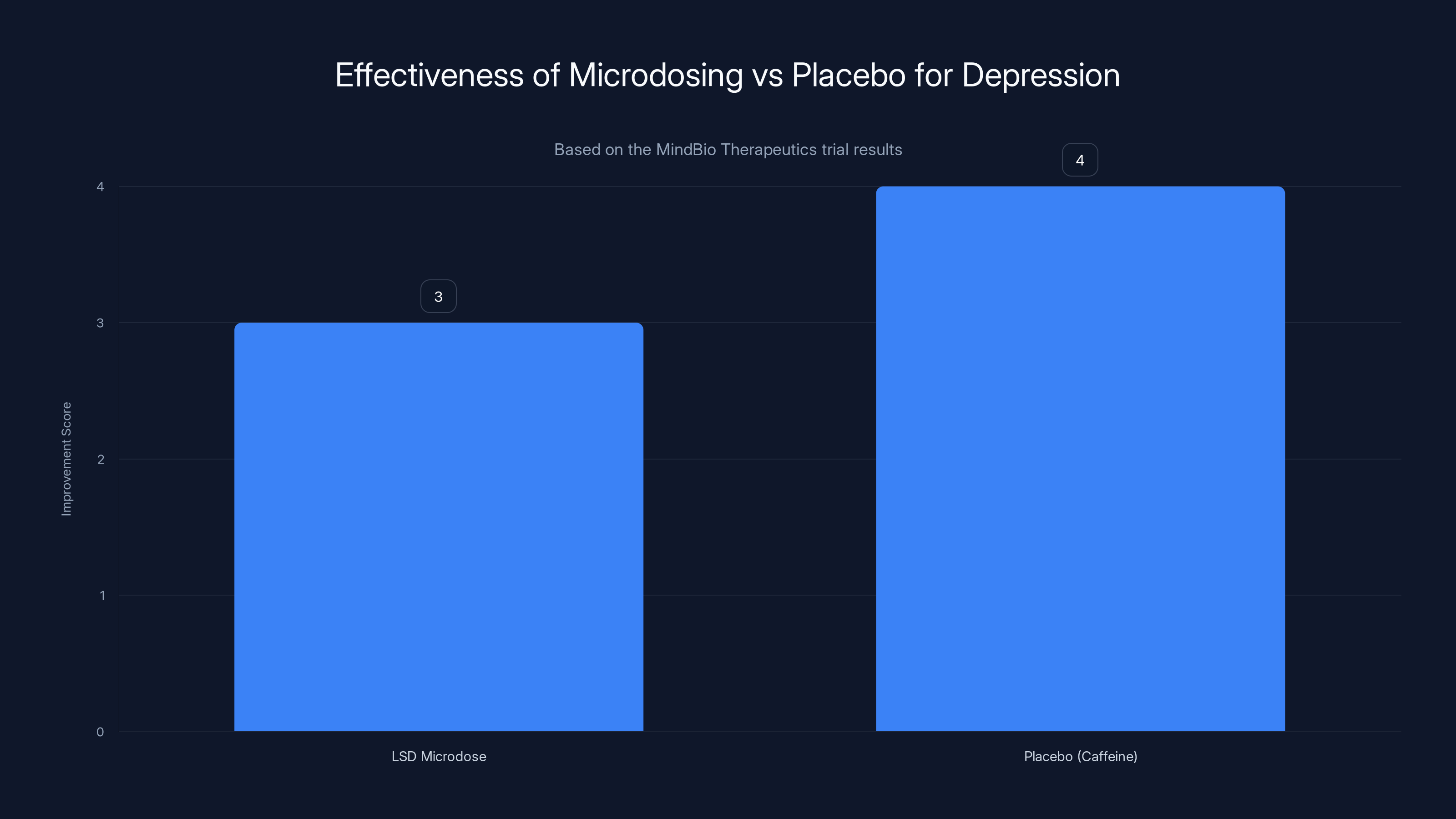

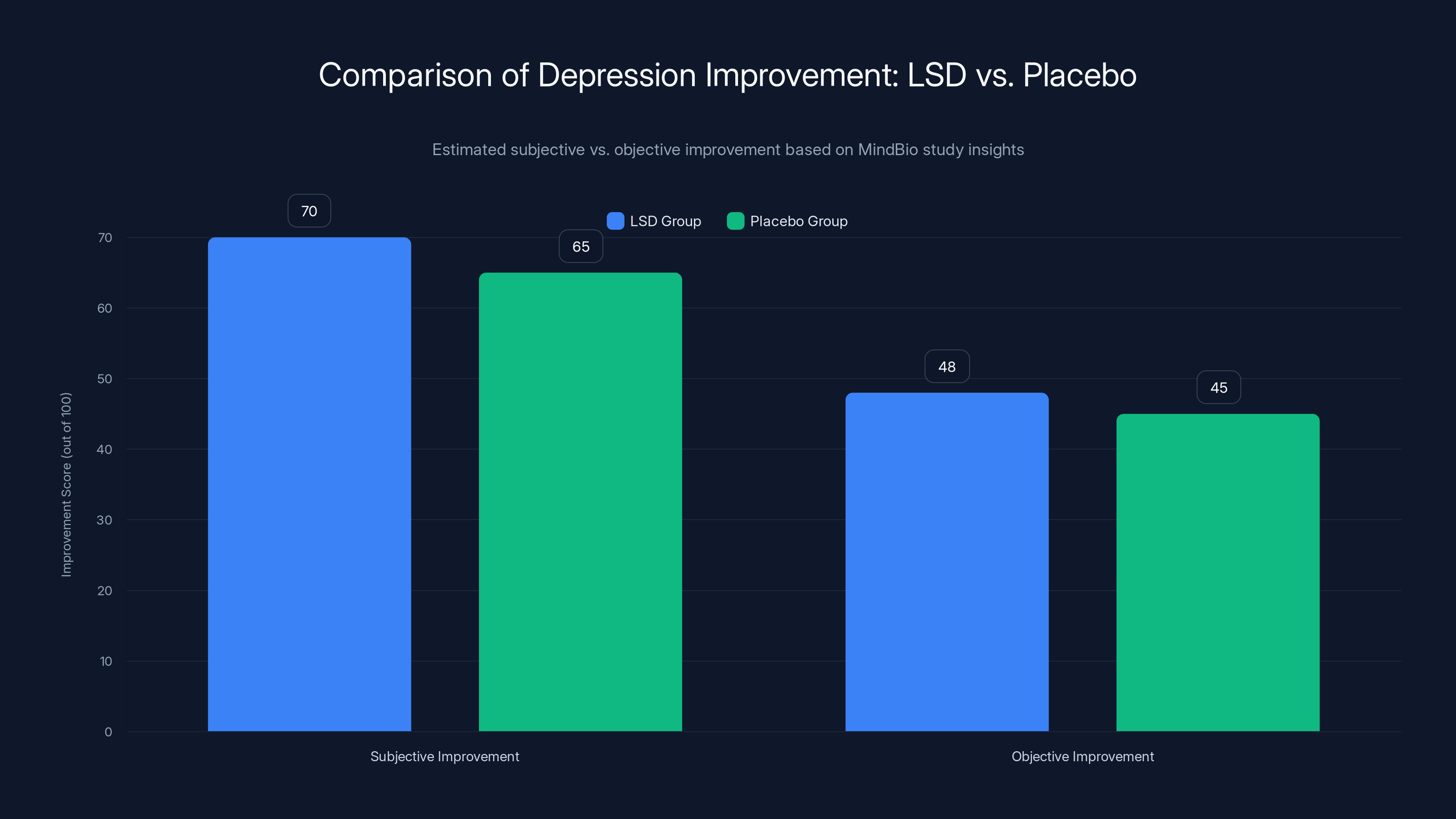

The MindBio study found that placebo (caffeine) performed as well or better than LSD microdosing in improving depression scores, indicating no significant advantage of microdosing.

The Mind Bio Trial: When Placebo Beats the Real Thing

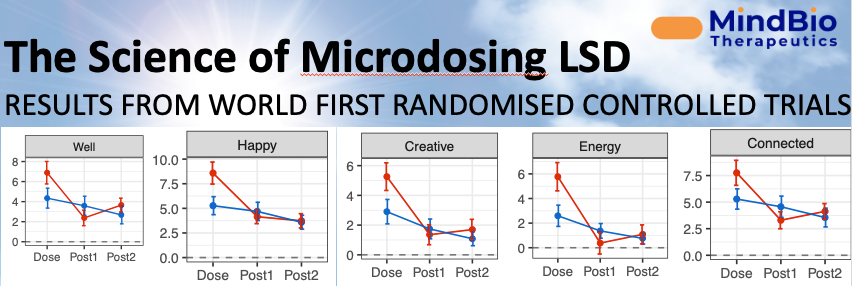

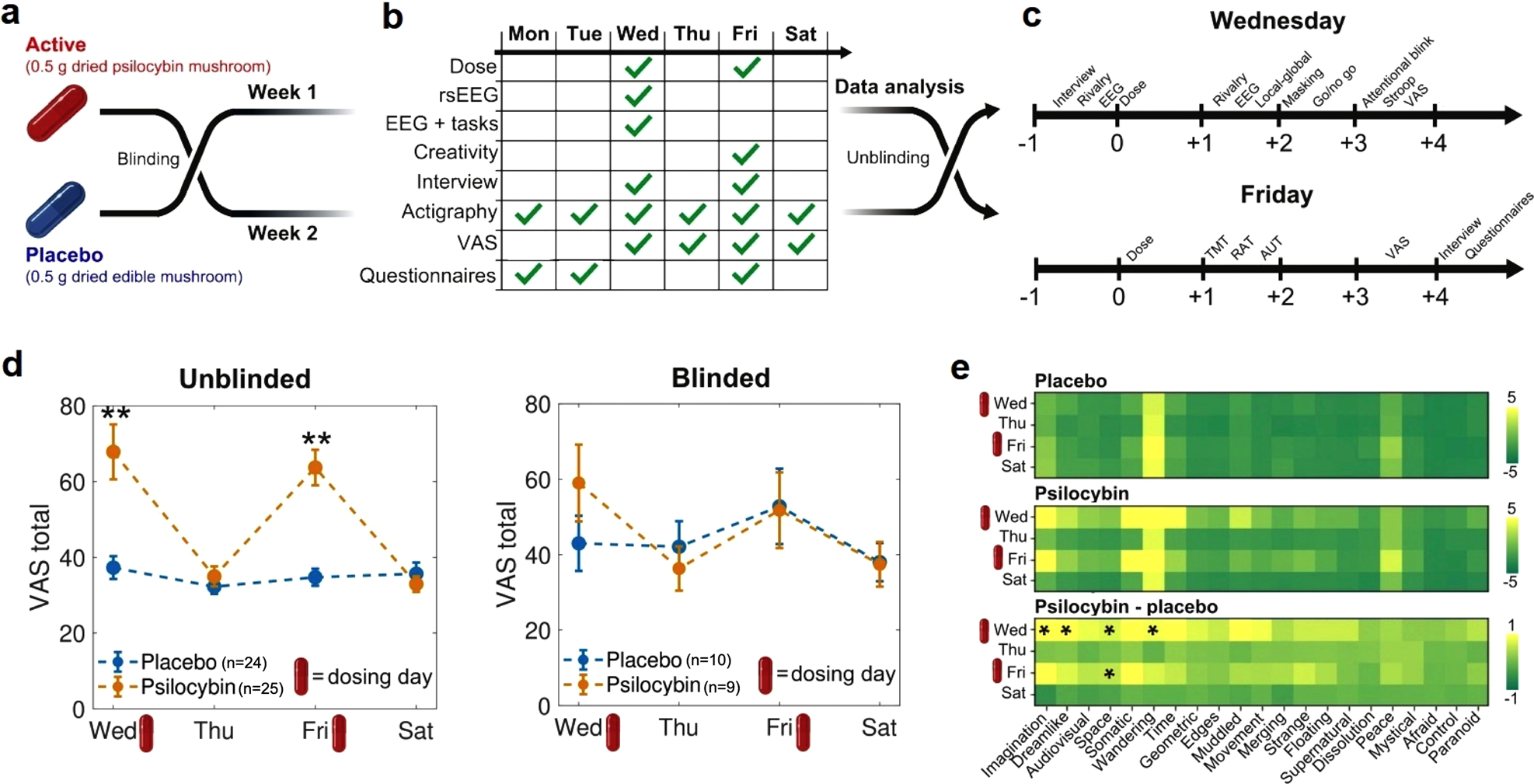

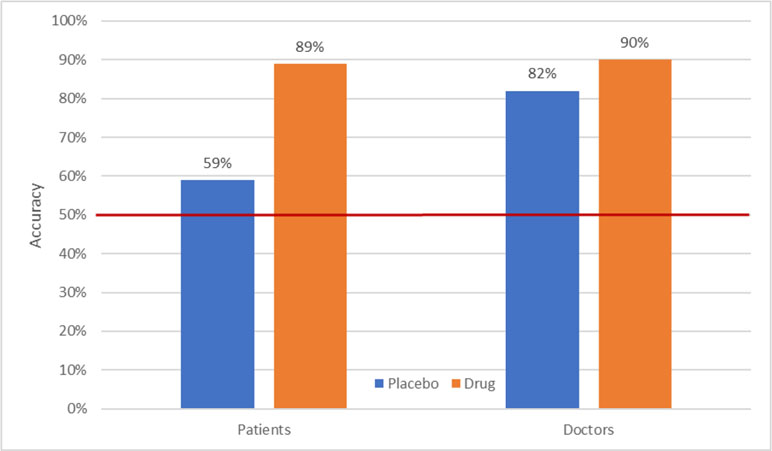

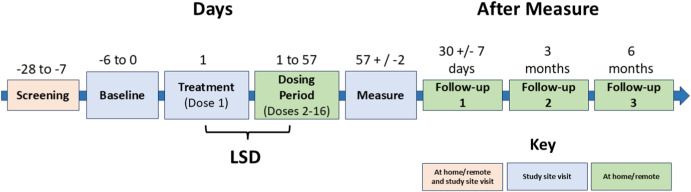

Melbourne-based Mind Bio Therapeutics set out to do what hadn't been done before at scale: a rigorous, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of LSD microdosing for major depressive disorder.

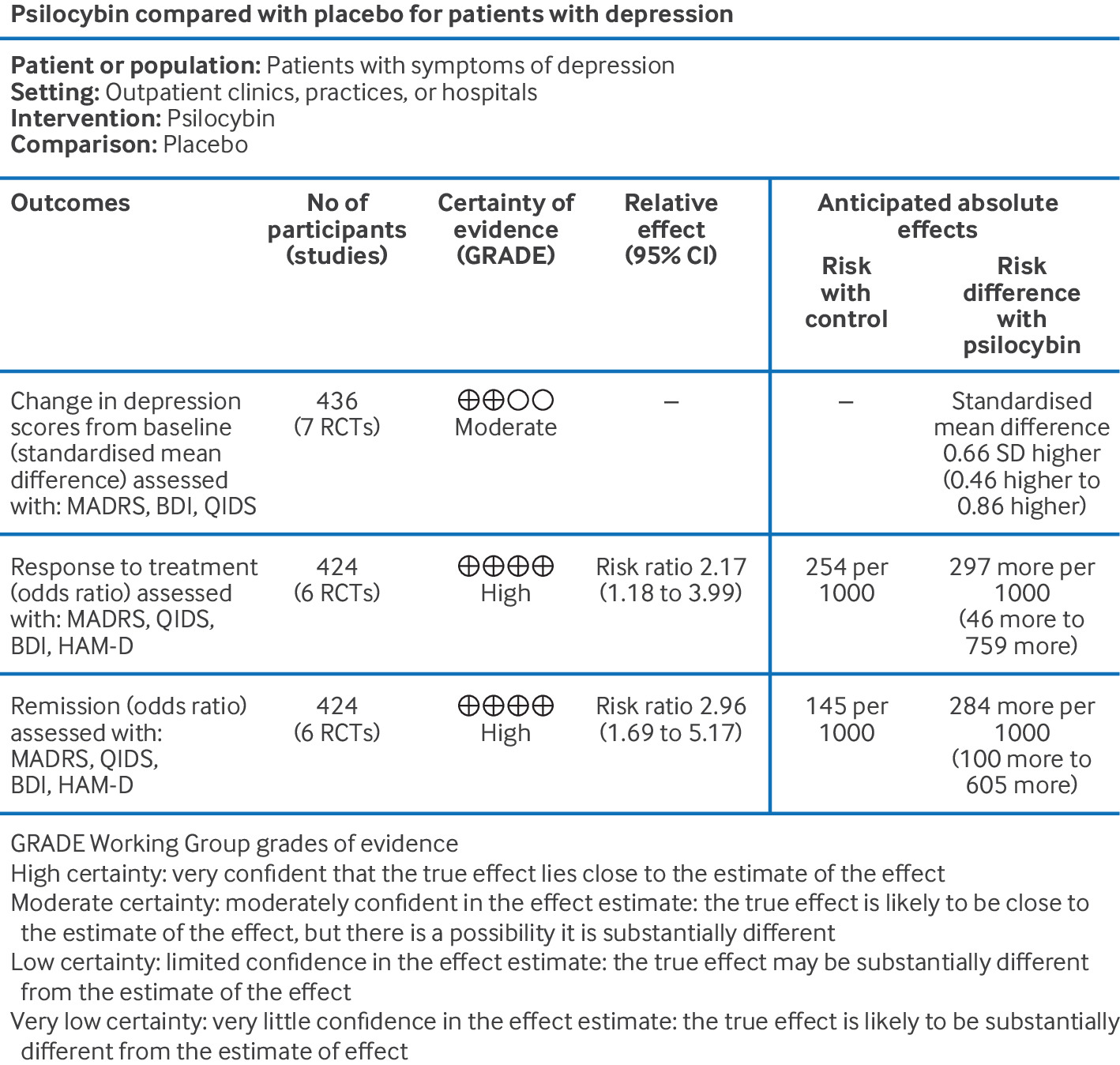

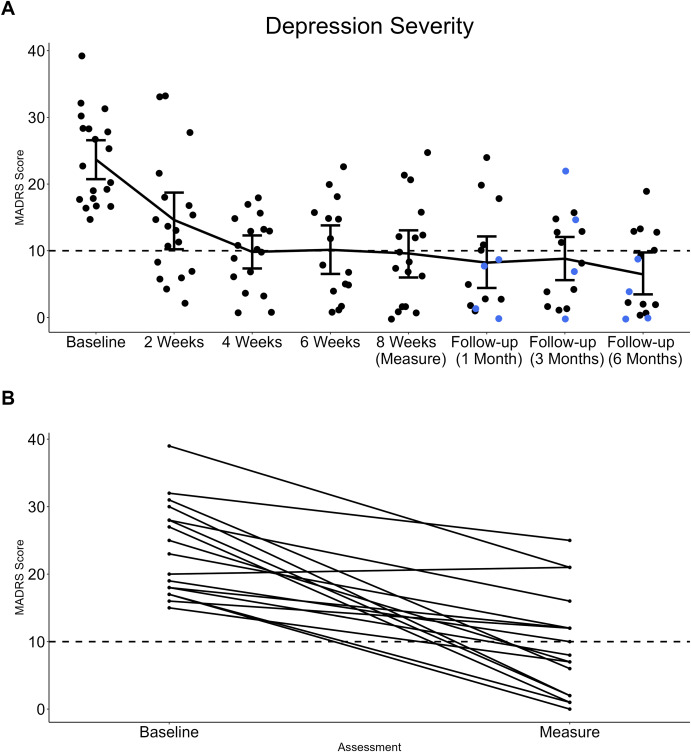

The study enrolled 89 adults. It ran for eight weeks. And it measured depression using a gold-standard clinical tool called the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), which is specifically designed to evaluate the severity of depressive symptoms in clinical settings.

Here's how they did it: some patients received actual LSD microdoses (ranging from 4 to 20 micrograms). Some received caffeine pills—an "active placebo" that produces noticeable effects so patients can't easily guess whether they're getting the real drug or not. The logic is clever: if you give someone a placebo pill with no effects, they'll know they didn't get the real drug. But if you give them caffeine, they feel something, and they might attribute that to the LSD.

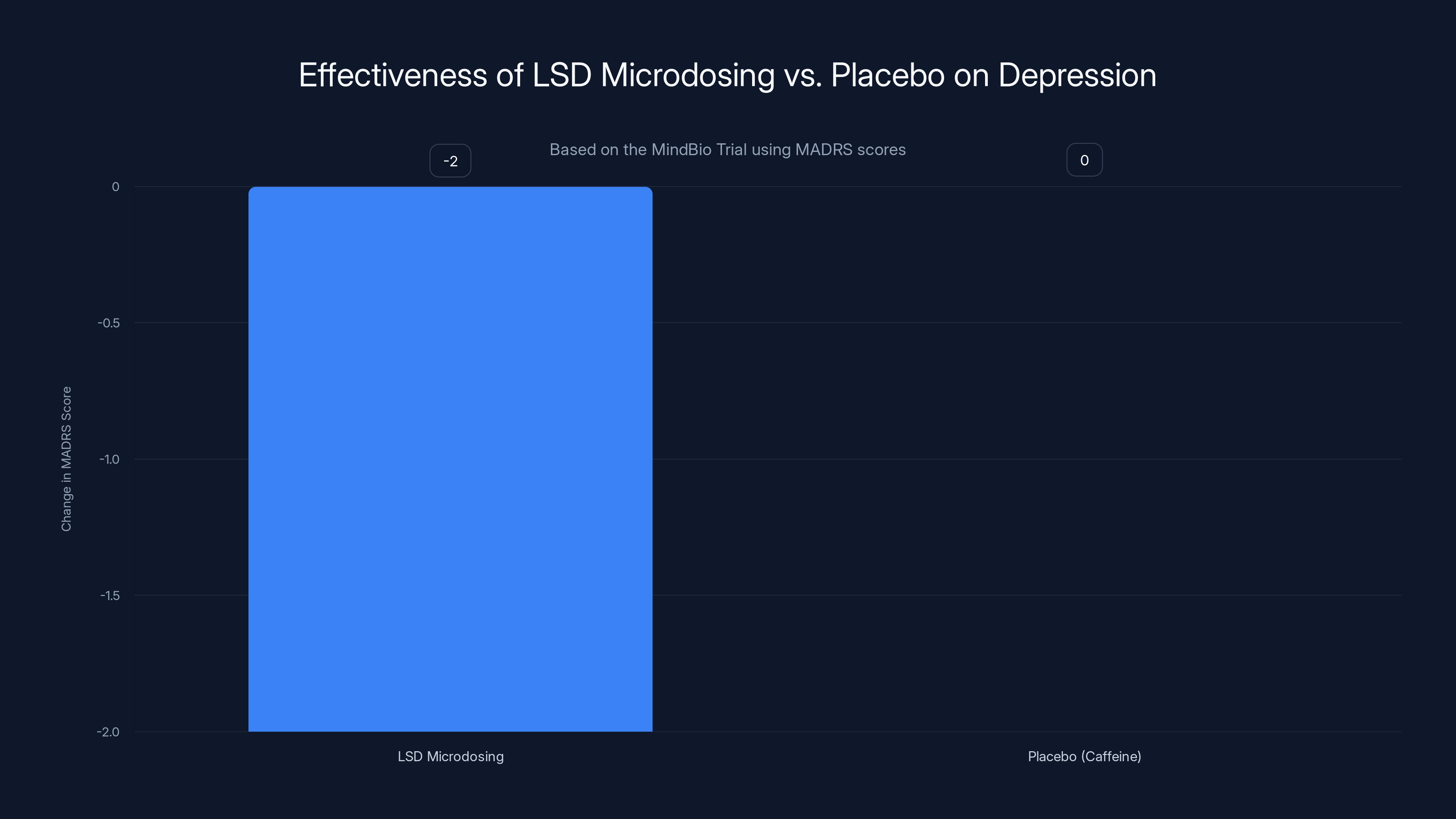

The results were unexpected, at least to microdosing enthusiasts. Patients on LSD reported feeling better—they had subjective improvements in well-being. But their MADRS scores, which measure actual depression symptoms, got worse compared to the placebo group. Or more precisely, the LSD group showed no statistically significant improvement in measurable depression symptoms compared to caffeine.

Let that sink in. A medium-strength cup of coffee performed as well as a dose of acid.

Mind Bio's CEO Justin Hanka didn't sugarcoat the implications. In a Linked In post revealing the results, he called it potentially "a nail in the coffin of using microdosing to treat clinical depression." He noted that while microdosing "probably improves the way depressed people feel," it doesn't do so in a way that's "clinically significant or statistically meaningful."

Translated: it feels good, but it doesn't actually work.

The MindBio trial found no significant improvement in depression symptoms for LSD microdosing compared to a caffeine placebo, as measured by MADRS scores. Estimated data.

The Placebo Effect in Psychedelic Research: Stronger Than We Thought

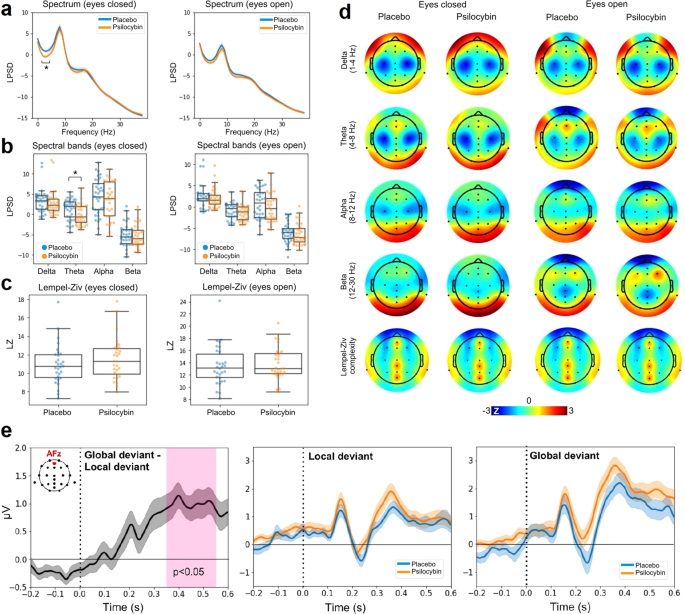

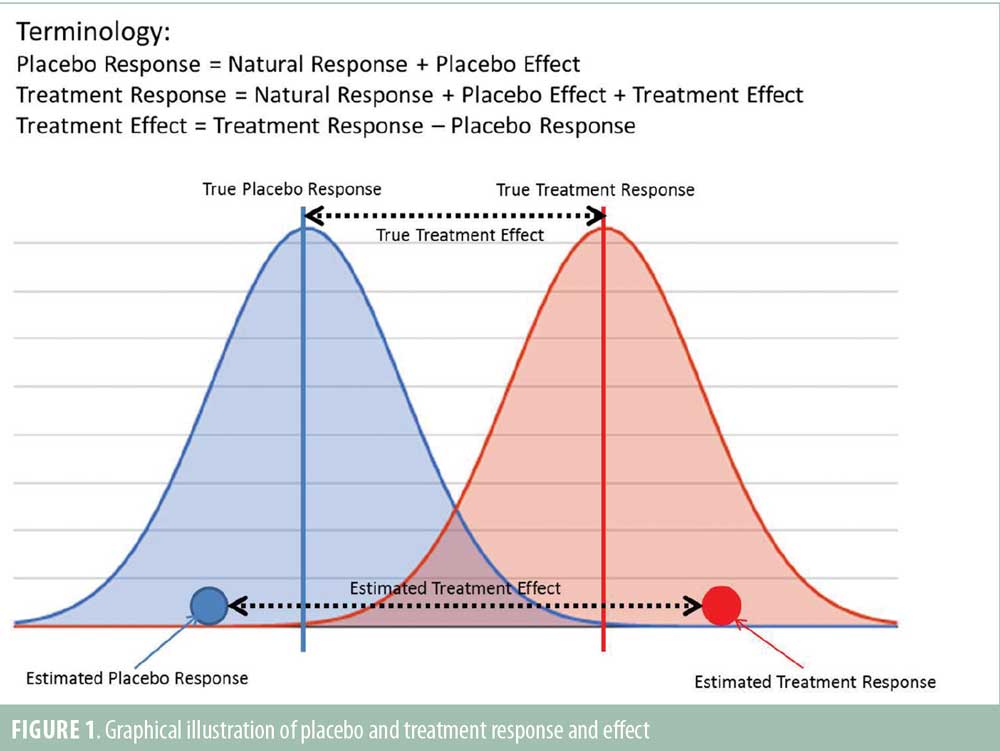

The Mind Bio study didn't happen in a vacuum. It confirmed something that some researchers had been suspecting for years: the placebo effect in psychedelic studies is enormous.

In 2020, Jay Olson, a researcher at Mc Gill University, conducted a study that's become something of a classic in the placebo literature. He called it "Tripping on Nothing."

Here's what Olson did: he told 33 participants they were receiving psilocybin (a psychedelic compound). He created an elaborate setup: trippy lighting, visual stimuli, environmental cues designed to make people expect a hallucinogenic experience. He had confederates—people in on the study—pretend to be experiencing drug effects nearby.

But nobody actually took any real drug. Everyone got a placebo. Period.

The results were stunning. A majority of participants reported feeling drug effects. They described altered perception, emotional changes, even subtle hallucinations. All from absolutely nothing.

Olson's conclusion: the placebo effect in psychedelic studies can be stronger than the actual effect of microdosing. Expectation, environment, and the power of the mind to create experience can outcompete the pharmacological effects of the drug itself.

This raises a profound question about how psychedelic research has been conducted. Most studies don't use active placebos. They don't carefully control expectation. They're run in research settings that, while sterile compared to the elaborate setups in Olson's study, still communicate "this is important, this is a special experience." Participants know they're in a psychedelic study. They expect effects. Their expectations shape what they experience.

Olson is careful to note that this doesn't mean microdosing has no effects. It means the effects might be psychological rather than pharmacological. Or, put another way, the effects might be real—real improvements in mood, real changes in perception—but caused by mechanisms that have nothing to do with the drug's chemistry.

As Olson told researchers, "It can be true at the same time that microdosing can have positive effects on people, and that those effects are perhaps almost entirely placebo."

Understanding the Placebo Effect: It's More Powerful Than Most People Think

Here's something that surprises most people: the placebo effect isn't just psychological comfort. It's not just people convincing themselves they feel better. It's a legitimate neurobiological phenomenon.

When you take a placebo and expect improvement, your brain actually changes. Blood flow patterns shift. Neurotransmitter levels fluctuate. Pain signals are genuinely reduced. Immune responses are activated. Brain imaging shows real activation in regions associated with reward and mood regulation.

The placebo effect is most powerful for subjective symptoms—pain, mood, anxiety, fatigue. These are exactly the symptoms that microdosers report improving. So we shouldn't be surprised that a placebo does well in a microdosing trial.

But here's the additional wrinkle: the placebo effect in psychedelic research is amplified by what researchers call "optimized expectation." You're told you're about to take a powerful psychoactive substance. You're placed in a special environment designed to facilitate an altered state. Your entire context screams "something important is happening." Your brain, primed by all these signals, creates an experience that matches your expectations.

Add in the fact that psychedelics are mysterious, culturally loaded drugs with decades of mythology around them. Add in the fact that users often have a significant emotional investment in the idea that microdosing will help. Add in the fact that depression itself is deeply influenced by expectation and meaning.

You get a perfect storm for placebo effects.

Participants reported higher subjective improvement with LSD compared to placebo, but objective scores showed minimal difference. Estimated data.

Why Microdosers Believe It Works: The Psychology of Attribution

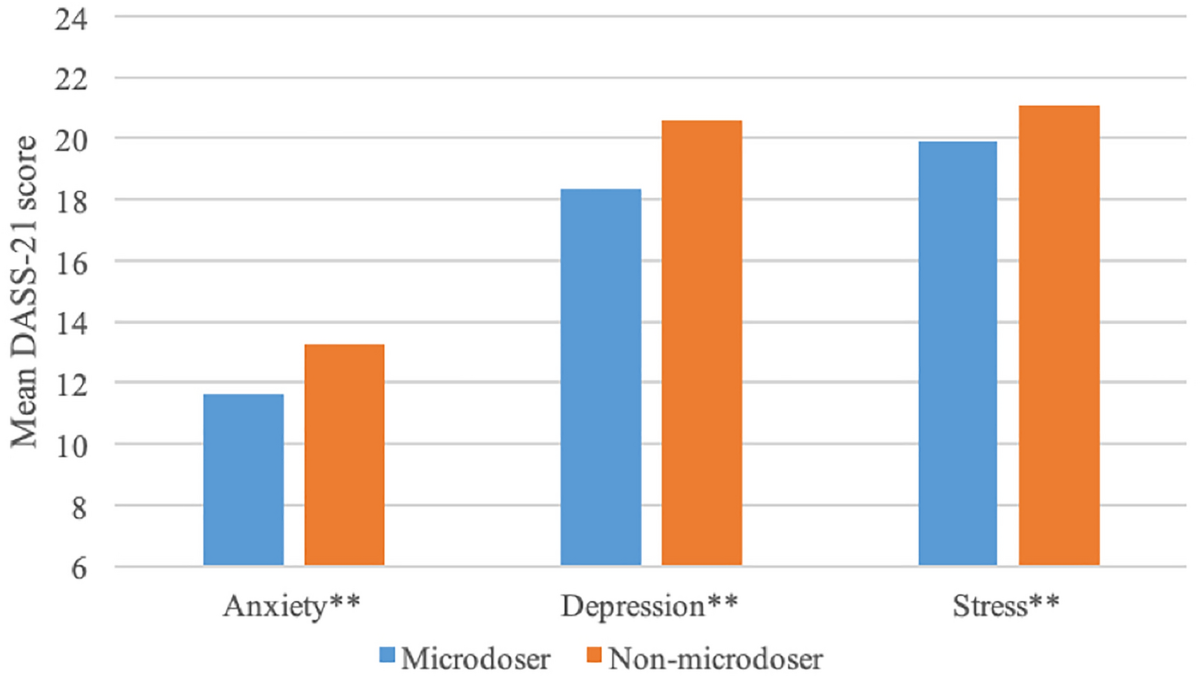

If microdosing is mostly placebo, why do so many people swear by it? Why do thousands of individuals report genuine improvements in mood and function?

The answer lies in how our brains attribute causation.

When you start a microdosing regimen, you're doing something deliberate about your mental health. You're taking action. You're optimizing. You're trying something that required research, planning, and courage (given that it's technically illegal in most places). That act of agency itself can improve mood and create a sense of progress.

Then, you're attuned to signs of improvement. You notice the mornings when you feel slightly better. You might not notice the mornings when you feel the same, because those don't fit the narrative. You're looking for evidence that microdosing works, and confirmation bias is a powerful filter.

Simultaneously, if you're doing microdosing, you're probably also doing other things: sleeping better (because you're intentional about your health), exercising more, maybe meditating or doing mindfulness work, perhaps reducing other substance use. These interventions genuinely help with depression. But you might attribute all of that improvement to the microdosing.

There's also the social dimension. If you're microdosing as part of a community—online forums, friend groups, communities of people experimenting with psychedelics—you're receiving social reinforcement. People share success stories. They validate the practice. They create a narrative of efficacy around it.

All of these factors combine to create a powerful sense that microdosing works. That sense can be real, meaningful, and valuable—without the actual pharmacological effect of the drug being particularly significant.

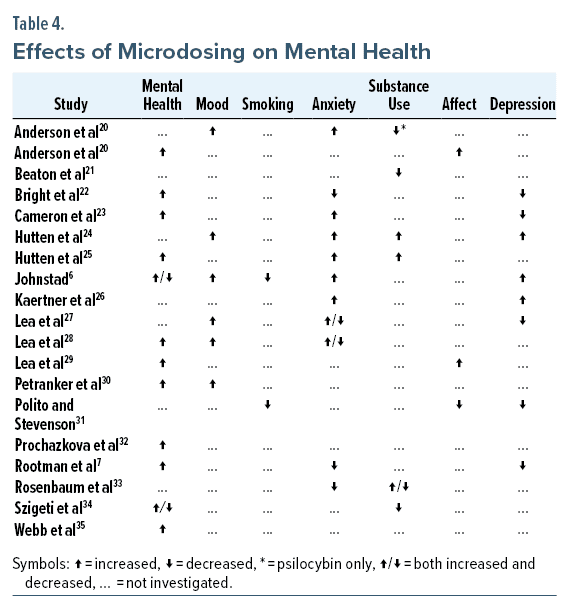

The Research Landscape: How We Got Here

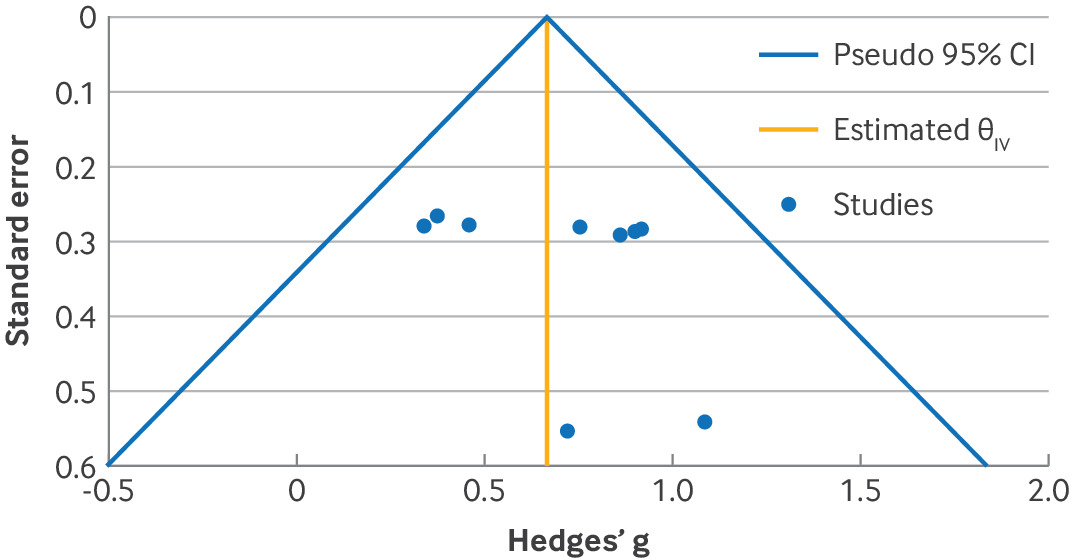

Before the Mind Bio trial and before Olson's placebo study, microdosing had been investigated, but never with the kind of rigor that's standard for pharmaceutical development.

Early research was suggestive. Studies showed correlations between microdosing and improved mood, creativity, or focus. But these were mostly observational—researchers gave people microdoses and asked them how they felt. Without placebo controls, you can't isolate the effect of the drug from the effect of expectation.

A few studies did try to be more rigorous. One 2022 study from the University of Chicago gave people either psilocybin microdoses or placebo and measured subjective effects. Placebo actually performed comparably to psilocybin.

Another study from UC Davis looked at potential cognitive benefits of psilocybin microdosing. The results? No significant differences between microdose and placebo groups on most cognitive measures.

But these studies were small. They didn't get huge media coverage. The narrative around microdosing—that it was a powerful tool for mental health and cognitive enhancement—was already established. New evidence that contradicted that narrative didn't shift the conversation.

Mind Bio's trial is different because it's larger, more rigorous, and the results are more definitive. It doesn't just suggest that placebo is powerful. It shows that placebo outperforms the active drug on clinical measures of depression.

Interest in microdosing has grown significantly since the early 2010s, driven by anecdotal reports and media coverage. Estimated data shows a steady increase in cultural momentum.

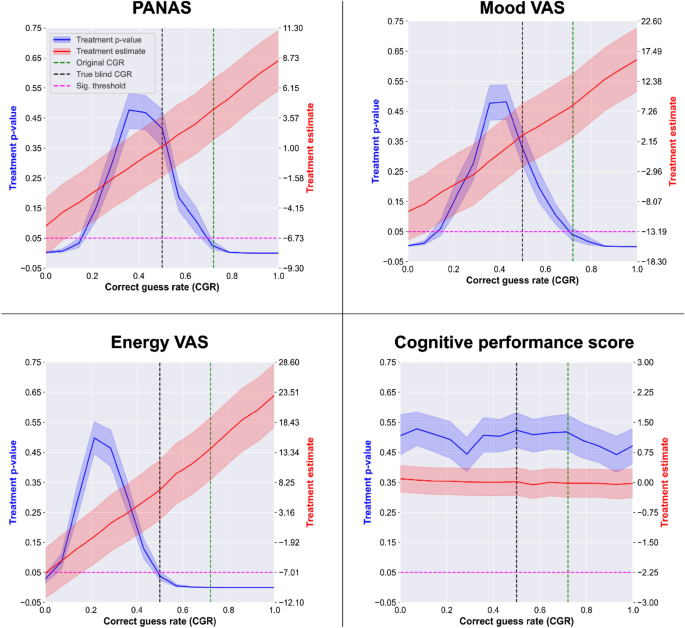

Double-Blinded, Double-Dummy: How Mind Bio Controlled for Expectation

Understanding Mind Bio's study design is crucial because the design itself might explain the surprising results.

They used something called a "double-dummy" design. Here's what that means: participants were told they might receive one of three things—LSD, caffeine, or methylphenidate (Ritalin). In reality, nobody got methylphenidate. But patients didn't know that. They were told they might get it.

Why does this matter? Because it lowered expectation. If you think you might be getting a stimulant, you might attribute any effects to the stimulant rather than to the LSD. If you think you might be getting Ritalin, you're not going into the study with maximum expectation of a psychedelic experience.

Contrast this with a typical microdosing study where participants are explicitly told they're getting psilocybin or LSD. Their expectation is optimized. They're primed to experience psychedelic effects. The environment, the framing, everything points toward "you're about to have a psychedelic experience."

Mind Bio's design actually prevented that optimized expectation. And that might explain why, in their trial, microdosing failed to outperform placebo.

Here's the subtle but important implication: it's possible that microdosing works when expectations are high, but only because of those high expectations. Dial down the expectations, and the benefit disappears.

What About Subjective Effects? Do They Matter If They're Placebo?

One nuance worth exploring: Mind Bio participants on LSD reported feeling better (subjective improvement), even though their objective depression scores didn't improve more than placebo.

Does that distinction matter?

In one sense, yes. If you feel better, that's a real effect. Your experience is real. Improved mood, even if placebo-induced, is better than depression.

But in another sense, it raises questions. If the feeling of improvement isn't matched by improvement in actual depressive symptoms, is that sustainable? Will people continue to feel better? Will that subjective improvement translate into better functioning, better relationships, better life outcomes?

Clinically, what matters is symptom reduction on validated measures. Depression isn't just a feeling state. It's a cluster of symptoms: sleep disturbance, appetite changes, loss of interest, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, feelings of worthlessness, thoughts of death. These are measurable. These are what psychologists and psychiatrists track.

A drug that makes you feel better but doesn't improve these symptoms might provide temporary psychological relief. But it's not treating the underlying disorder.

That's the critical distinction the Mind Bio study reveals.

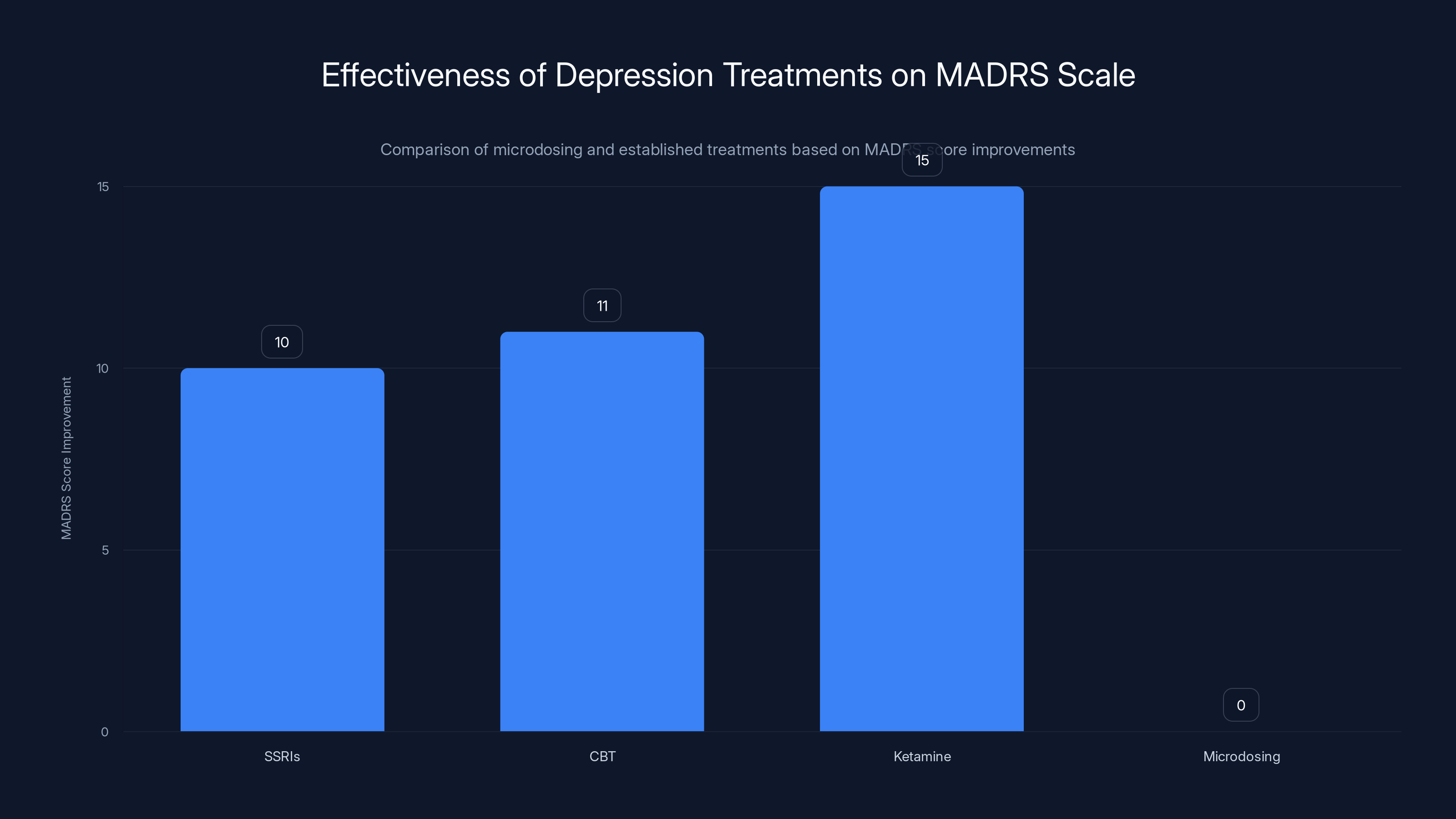

Established treatments like SSRIs, CBT, and Ketamine show significant improvements in MADRS scores, while microdosing shows negligible effect, similar to placebo. Estimated data based on typical clinical findings.

Comparison: Microdosing vs. Established Treatments for Depression

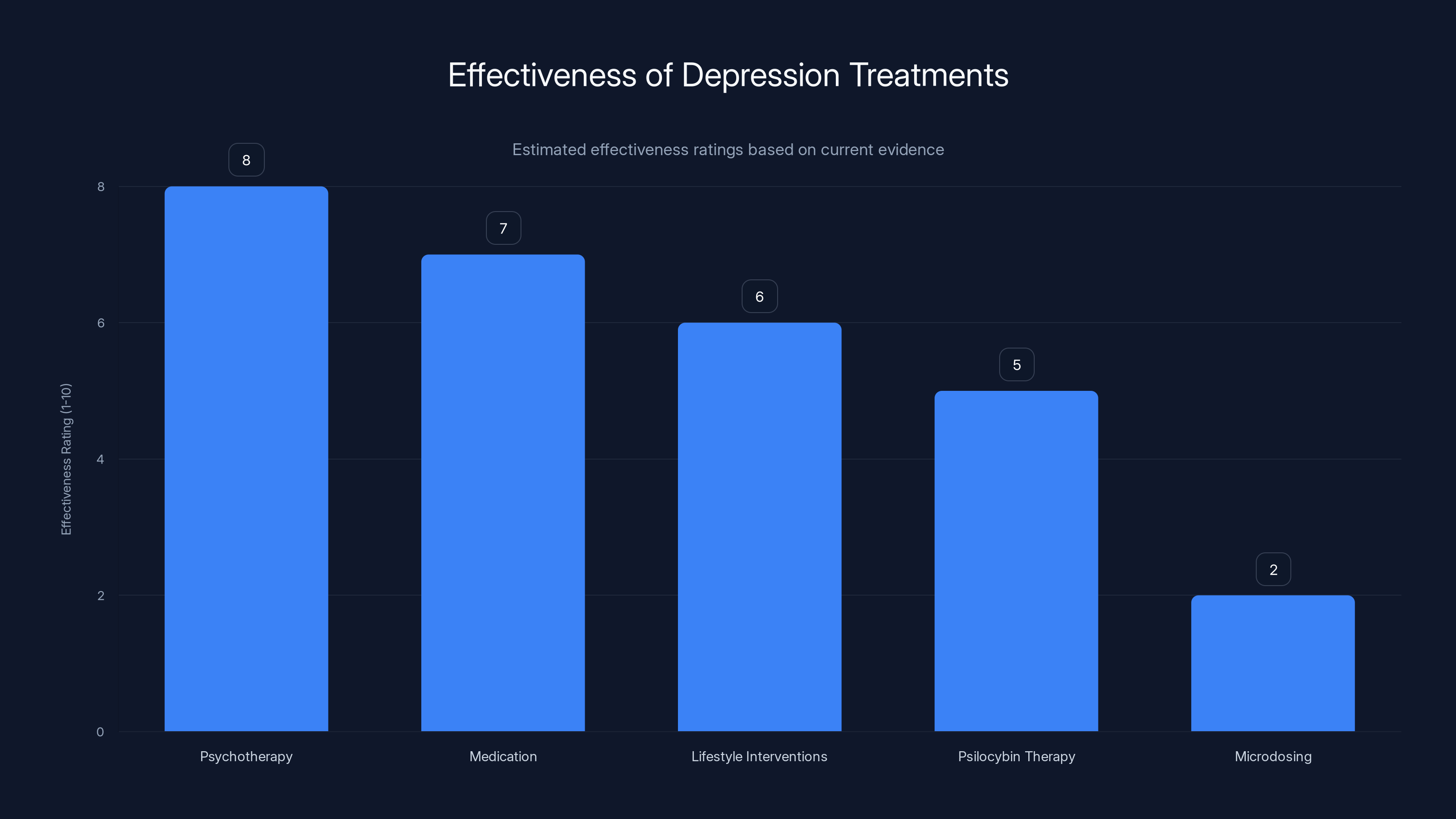

To put Mind Bio's findings in perspective, it's worth comparing microdosing to treatments that actually work for depression.

SSRI antidepressants (like sertraline or fluoxetine) show improvements on the MADRS scale typically ranging from 8-12 points in clinical trials. Psychotherapy, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), shows similar or sometimes better results. Ketamine therapy, a more recent intervention, shows rapid reductions in depressive symptoms that can be quite dramatic.

Microdosing? In the Mind Bio trial, the effect on MADRS scores was indistinguishable from placebo. That means either zero effect or a small effect that's swamped by placebo. Either way, it's not in the ballpark of treatments we know work.

This doesn't mean SSRIs are perfect. They have side effects, they don't work for everyone, and they can take weeks to work. But they've been tested in hundreds of trials involving tens of thousands of participants. We know what to expect.

With microdosing, we're still in the early experimental phase. And the early evidence is not encouraging.

The Future of Psychedelic Research: Learning From Microdosing

The microdosing results, while disappointing for people hoping for a breakthrough treatment, actually provide valuable lessons for psychedelic research more broadly.

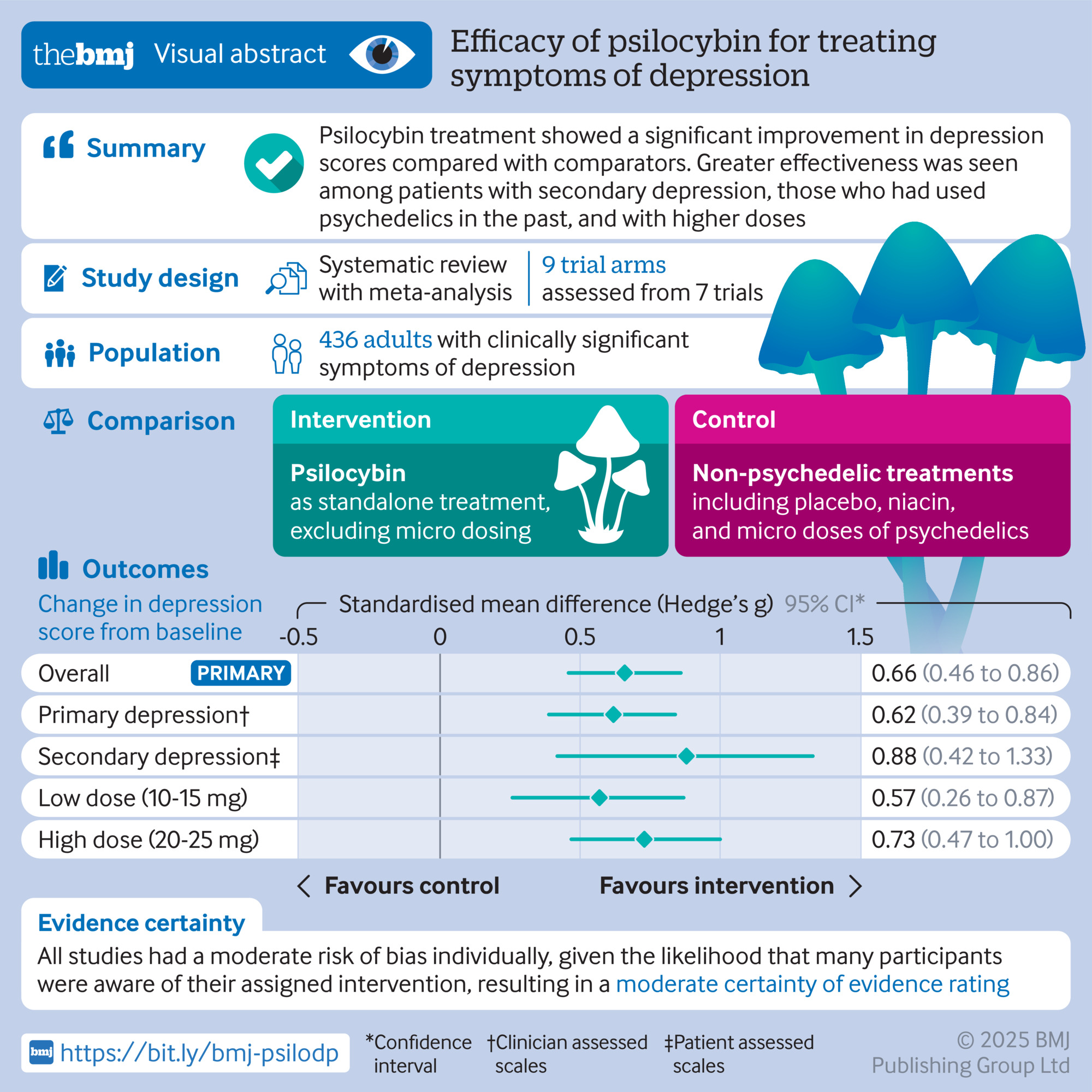

Full-dose psilocybin therapy, for instance, shows promise in clinical trials for depression and PTSD. But these studies are typically conducted in highly controlled environments with therapeutic support. They're not simple pharmacology—they're complex, multimodal interventions. The drug is one component. The therapy, the setting, the preparation, the integration—these matter enormously.

Microdosing was sold as a simpler version of this: take a tiny bit of the drug, and you get the benefits without needing the elaborate therapeutic context. The assumption was that the drug itself was doing the work.

Mind Bio's findings suggest that assumption was wrong. If anything, the drug alone might be relatively inert. The effect comes from context, expectation, and the therapeutic work.

This actually aligns with what we know about classical psychedelic therapy. The drugs are tools. They open people to change. But the real work—the integration, the processing, the behavioral change—happens in the context of therapeutic support and intention.

Microdosing tried to shortcut that. And apparently, you can't.

Psychotherapy and medication are among the most effective treatments for depression, while microdosing has limited evidence of effectiveness. Estimated data based on current research insights.

Implications for Depression Treatment: What Should People Actually Do?

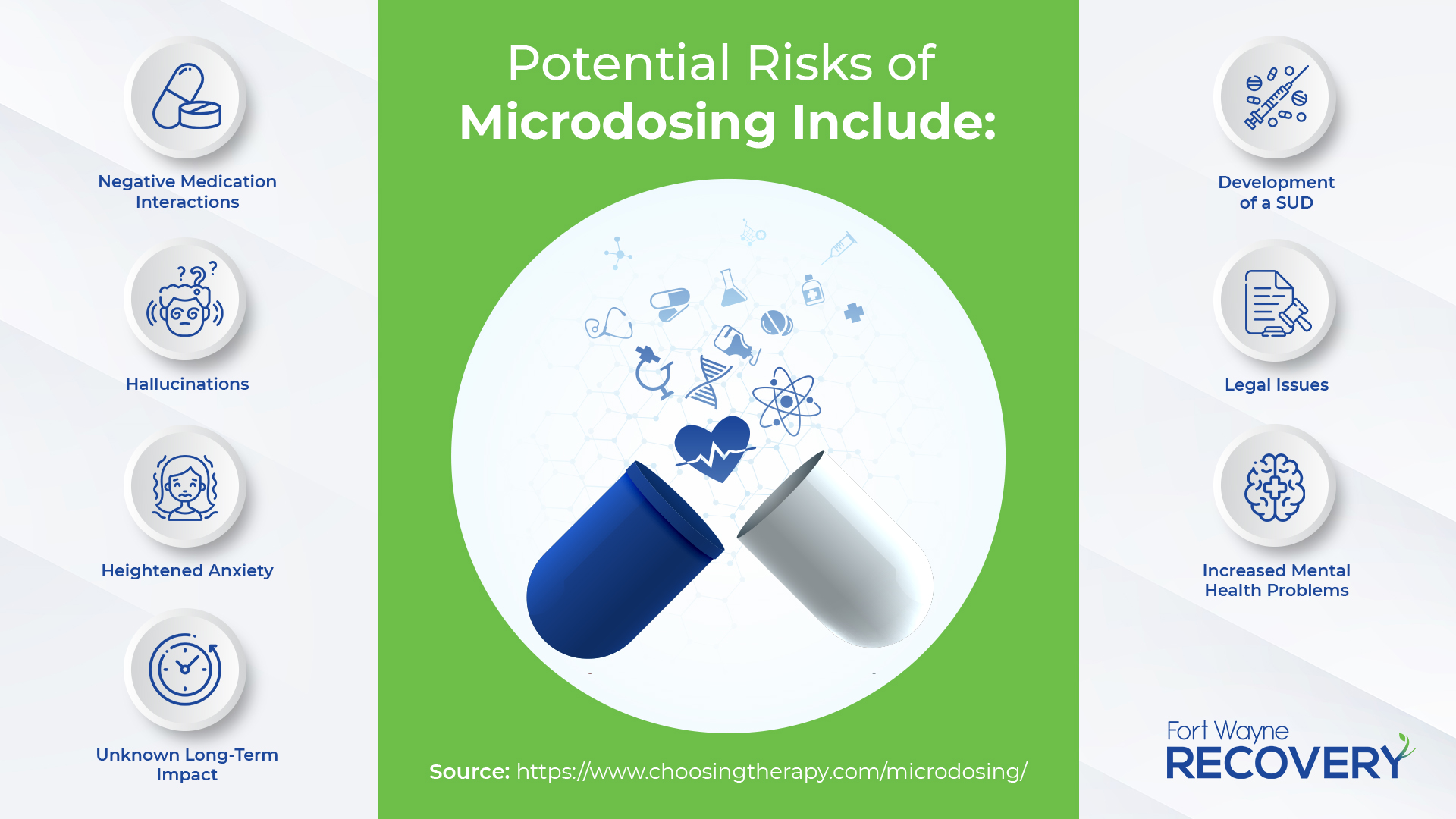

If you're dealing with depression, and you're considering microdosing, what should you actually do?

First, understand that the current evidence doesn't support microdosing for depression. The most rigorous trial to date found no benefit. The placebo effect appears to be doing most of the work.

Second, if you're considering microdosing because you haven't found relief with conventional treatments, consider other evidence-based options. These include:

Psychotherapy: CBT, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and interpersonal therapy all have robust evidence. They take time, but they work.

Medication: If you haven't tried SSRIs or SNRIs, they're worth trying. If you have, there are other classes of antidepressants. If standard options haven't worked, there's ketamine therapy, which can produce rapid improvements.

Lifestyle interventions: Exercise, sleep, social connection, and purpose are not trivial. They're foundational. Often, depression improves dramatically when these are in place.

Psilocybin therapy: If you're interested in psychedelics for mental health, the most evidence-based path is participating in a clinical trial of full-dose psilocybin therapy, typically combined with psychotherapy. These are starting to become available through clinical research programs.

Microdosing on your own, without therapeutic support, without supervision, based on anecdotal reports and community lore, is not evidence-based medicine. It might make you feel better temporarily. But it probably won't treat the underlying depression.

Why This Matters: The Bigger Picture on Evidence and Mental Health

The microdosing story is really a story about evidence, belief, and how we evaluate new treatments.

For decades, mental health treatment has been something of a Wild West. Therapies make intuitive sense, or get packaged with compelling narratives, and people believe in them before rigorous evidence arrives. Sometimes the evidence supports the belief. Sometimes it doesn't.

Microdosing fit into a compelling narrative: illegal drugs, used properly, outperform legal medicine. It appealed to people who felt failed by conventional psychiatry. It offered hope. It was also mysterious, somewhat underground, culturally transgressive—all appealing to certain segments of the population.

But hope and narrative aren't enough. Evidence matters. And when the evidence comes back negative, it's important to pay attention.

This doesn't mean people's experiences are invalid. Many people genuinely felt better after microdosing. But the reasons for that improvement might not be what they thought. And understanding those reasons—that expectation and attention and intention matter more than the drug itself—is actually useful information.

It means that if you feel better from a placebo effect, you could potentially feel better from other placebo effects. You could derive similar benefits from a rigorous expectation-setting exercise, or from deliberate attention to your mental health, or from believing strongly in a therapy and engaging with it fully.

The power is not in the drug. It might be in your mind, and in the context you create.

The Limits of Self-Experimentation: Why Individual Cases Don't Prove Efficacy

One common response to studies like Mind Bio's is: "Well, it works for me." And that's probably true. Some people have taken microdoses and felt better. Their experience is real.

But individual cases have a critical limitation: they're almost impossible to interpret. You can't be your own control group. You can't know what would have happened if you hadn't microdosed. You can't know whether the improvement came from the drug or from dozens of other factors changing simultaneously.

This is why we have clinical trials. They're imperfect, but they're the best tool we have for answering the question: does this intervention work beyond the power of expectation and circumstance?

Microdosing has now been tested with that tool. And the answer, at least for depression, appears to be no.

This is actually a common pattern in medicine. Lots of treatments that work for individuals in uncontrolled settings fail when tested rigorously. This doesn't mean the individual experiences were fake. It means we were attributing them to the wrong cause.

Looking Forward: What Happens to Microdosing Now?

Mind Bio released these results in a Linked In post, not in a peer-reviewed journal. The study has not yet been formally published. This means the results haven't undergone peer review from independent researchers. The methodology hasn't been scrutinized. The conclusions might be refined, challenged, or confirmed once the full paper is out.

But even without formal publication, the results are significant. Mind Bio has invested serious resources into this trial. They're a real biopharma company. They had every incentive to find positive results—that's better for their business. The fact that they're publicly releasing negative results suggests they're being honest about what they found.

What happens next? A few possibilities:

First, more research will probably happen. Other companies and research groups will likely conduct their own trials. Some might use different doses, different microdosing protocols, or different populations. Some might find different results.

Second, the narrative around microdosing will probably shift. It's already shifting in scientific circles. But in popular culture, in online communities, the old narrative—that microdosing is a powerful tool for mental health—will persist. Belief is sticky. Evidence doesn't always change it.

Third, people will probably continue to microdose. Because belief matters. And if someone believes microdosing helps, that belief might actually create improvement through placebo effects. The efficacy might be illusory, but the benefits real.

What matters is that people understand what they're actually doing. They're not using a proven treatment for depression. They're engaging in an experimental practice that might create placebo effects. If they want to do that, that's their choice. But they should do it with open eyes.

Alternative Explanation: Could the Study Be Wrong?

It's fair to ask: what if Mind Bio's trial is flawed? What if the results don't hold up?

Possible criticisms: The sample size is modest (89 participants). The duration is relatively short (8 weeks). The doses are on the lower end of typical microdosing protocols. The population was specifically people with major depressive disorder, and maybe microdosing works better for subclinical depression or for enhancing normal mood.

These are reasonable questions. Any single study has limitations. But Mind Bio's findings align with earlier research that suggested placebo effects are large in psychedelic studies. They also align with basic pharmacology—LSD at 4-20 micrograms produces barely measurable effects on serotonin signaling. It's plausible that such small doses have minimal pharmacological impact.

Would additional trials change the picture? Maybe. But the burden of proof has shifted. Previously, the narrative was "microdosing works" and skeptics asked for evidence. Now, the narrative should be "microdosing probably doesn't work for depression," and enthusiasts would need to provide convincing evidence to the contrary.

Lessons for Other "Biohacking" Interventions

Microdosing is one example of a broader category: interventions that gain popularity through social proof and anecdotal reports before rigorous evidence arrives.

Other examples include certain nootropics, some supplements, unproven cancer treatments, and various wellness practices. The pattern is familiar: compelling narrative, early adopters sharing positive experiences, community building, cultural momentum, and then eventually—if we're lucky—rigorous research.

Sometimes that research confirms the hype. Sometimes it doesn't. But the lesson from microdosing is clear: don't wait for the research to finish before believing something works. But do pay attention when the research arrives and contradicts your expectations.

The challenge is distinguishing between treatments that work (even if we don't yet understand why) and treatments that seem to work because of expectation and circumstance. Rigorous research is the best tool we have for making that distinction.

Conclusion: The Hard Truth About Microdosing and Depression

Microdosing for depression probably doesn't work. At least, not in the way believers think it works. Not through direct pharmacological action on depressive symptoms. Not in a way that's significantly better than taking a caffeine pill and believing in it.

The feeling of benefit that people report might be real. The subjective experience of improved mood might be genuine. But the mechanism is probably not the drug itself. It's probably expectation, attention, intention, and the complex interplay between mind and body that we call the placebo effect.

This is not nothing. Placebo effects are real. They produce measurable changes in brain function and symptom severity. A strong belief that something will help can actually improve your mood, reduce your anxiety, and make you feel better.

But if what you actually want is to treat depression—to address the underlying dysfunction, to improve sleep and appetite, to restore interest and motivation, to reduce suicidal ideation—then you need something that works beyond the power of belief. You need a treatment with actual efficacy.

For depression, those treatments exist. They're not sexy. They're not mysterious. They're not part of a transgressive biohacking community. But they work. Psychotherapy works. Antidepressant medication works. Exercise works. Sleep works. Social connection works. And full-dose psilocybin therapy, administered in a clinical context with psychotherapy, probably works.

Microdosing on your own, based on anecdotal reports and online protocols? That probably doesn't.

The good news is that there are better options. The hard news is that they might require more time, effort, and vulnerability than swallowing a tiny pill and hoping for the best.

But if you actually want to get better, that's the direction to move in.

FAQ

What is microdosing?

Microdosing refers to taking very small amounts of psychedelic drugs—typically 5 to 20 micrograms of LSD or small amounts of psilocybin mushrooms—well below doses that produce hallucinations. Proponents believe these tiny amounts can improve mood, creativity, focus, and other cognitive functions without causing perceptual distortions.

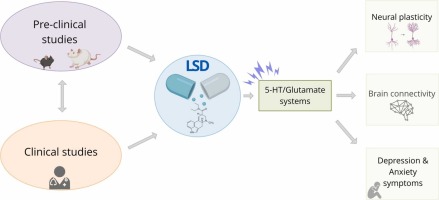

How does microdosing supposedly work for depression?

According to anecdotal reports and promotional materials, microdosing may work by gently modulating serotonin signaling, improving mood regulation, and enhancing emotional processing. However, scientific research suggests the pharmacological effects at microdose levels are minimal, and any benefits are likely attributable to placebo effects and expectation rather than the drug's direct action on brain chemistry.

What did the Mind Bio study actually find?

The Mind Bio Therapeutics trial examined 89 adults with major depressive disorder over eight weeks. Participants received either LSD microdoses (4-20 micrograms), caffeine pills, or were told they might receive methylphenidate. Results showed that the placebo group (caffeine) performed as well or better than the LSD group on standardized depression rating scales, suggesting that microdosing provides no significant clinical advantage for treating depression.

Is the placebo effect real, or does it just mean "it's all in your head"?

The placebo effect is genuinely real and involves measurable changes in brain function, neurotransmitter levels, immune responses, and physical symptoms. When you expect improvement and receive a placebo, your brain actually activates reward pathways and releases endogenous neurochemicals that can reduce pain, anxiety, and mood symptoms. However, placebo effects are typically strongest for subjective symptoms and fade over time if the underlying condition is not addressed.

Can I still microdose if I find it helpful, even if it's placebo?

If microdosing provides you with a beneficial placebo effect, you might experience genuine mood improvement. However, it's worth considering that the same placebo effect could potentially be achieved through other means—such as therapy, meditation, or other evidence-based interventions that also address underlying depressive symptoms. Additionally, microdosing carries legal risks and potential unknown long-term effects. Consulting with a mental health professional about safer, more effective alternatives is recommended.

What treatments for depression actually have strong evidence?

Multiple evidence-based treatments exist for depression: cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), other antidepressant classes, exercise, improved sleep hygiene, social connection, and newer options like ketamine therapy. Full-dose psilocybin therapy, administered in clinical settings with psychotherapy, shows promise in ongoing research. These treatments have been tested in rigorous trials and demonstrate measurable, sustained improvements in depressive symptoms.

Why do so many people report that microdosing helps them if it doesn't actually work?

Attribution bias plays a major role: people attribute improvements to microdosing when they might result from other factors (starting therapy, lifestyle changes, improved sleep). Confirmation bias leads people to notice and remember improvements while discounting neutral or negative days. Social reinforcement within microdosing communities strengthens belief in efficacy. Additionally, the subjective feeling of improvement from placebo effects is real, even if objective depression symptoms don't improve.

Is microdosing safe?

At the doses typically used, LSD and psilocybin are unlikely to cause acute toxicity. However, long-term safety data is minimal, and users face legal risks. More importantly, if depression goes untreated while someone relies on microdosing, the condition can worsen. There's also potential for microdosing to interact with psychiatric medications or to mask symptoms that require professional intervention.

Will more research change these findings about microdosing?

Future research might reveal different results in different populations or using different protocols. However, the current evidence—including the large Mind Bio trial and earlier studies showing strong placebo effects in psychedelic research—suggests that microdosing's benefits are primarily psychological rather than pharmacological. Additional rigorously designed trials will help clarify, but the burden of proof has shifted to demonstrating efficacy, rather than assuming it exists.

Should I try full-dose psilocybin therapy instead of microdosing?

If you're interested in psychedelic-assisted therapy for depression, the most evidence-based option is participating in a clinical trial of full-dose psilocybin therapy, which combines the psychedelic experience with professional psychotherapy and integration support. This is fundamentally different from self-administered microdosing. However, first-line treatments like therapy or antidepressant medication should be tried before pursuing experimental options, and any decision should involve consultation with a mental health professional.

Key Takeaways

- MindBio's Phase 2B trial of 89 patients showed microdosing LSD performed no better than placebo (caffeine) for clinical depression symptoms

- Placebo effects in psychedelic research are extraordinarily powerful, as demonstrated by Olson's 'Tripping on Nothing' study where 50%+ of participants reported drug effects from pure placebo

- While microdosers report feeling better subjectively, objective depression measurements show no clinically significant improvement beyond placebo

- Evidence-based treatments like psychotherapy, SSRIs, exercise, and ketamine therapy show measurable improvements in depression symptoms that microdosing does not achieve

- Attribution bias, confirmation bias, and optimized expectation explain why people believe microdosing works despite lack of pharmacological efficacy

Related Articles

- Character.AI and Google Settle Teen Suicide Lawsuits: What Happened [2025]

- Can a Social App Really Fix Social Media's 'Terrible Devastation'? [2025]

- Digital Diary Guide: Why You Should Journal & Best Apps [2025]

- OpenAI's Head of Preparedness: Why AI Safety Matters Now [2025]

- Can You Buy Relaxation? The Science Behind Electric Fireplaces [2025]

![Microdosing for Depression: Placebo Effect vs. Real Benefits [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microdosing-for-depression-placebo-effect-vs-real-benefits-2/image-1-1769772839973.jpg)