Microsoft Copilot Bypassed DLP: Why Enterprise Security Failed [2025]

Imagine this: your most confidential emails sit in Microsoft's data centers, marked with the highest sensitivity labels and protected by every data loss prevention rule your team could configure. Your Copilot deployment is supposed to respect those rules. It's a fundamental assumption.

Then, for four straight weeks, Copilot reads them anyway. Summarizes them. Hands the content back to users who had no business accessing it.

And your entire security stack stays silent.

This isn't hypothetical. It happened starting January 21, 2025. The U.K. National Health Service logged it as INC46740412. Microsoft tracked it as CW1226324. When the advisory dropped on February 18, security teams got the same message: we missed this. Your EDR didn't catch it. Your WAF didn't catch it. Your SIEM didn't catch it. This is the story of why.

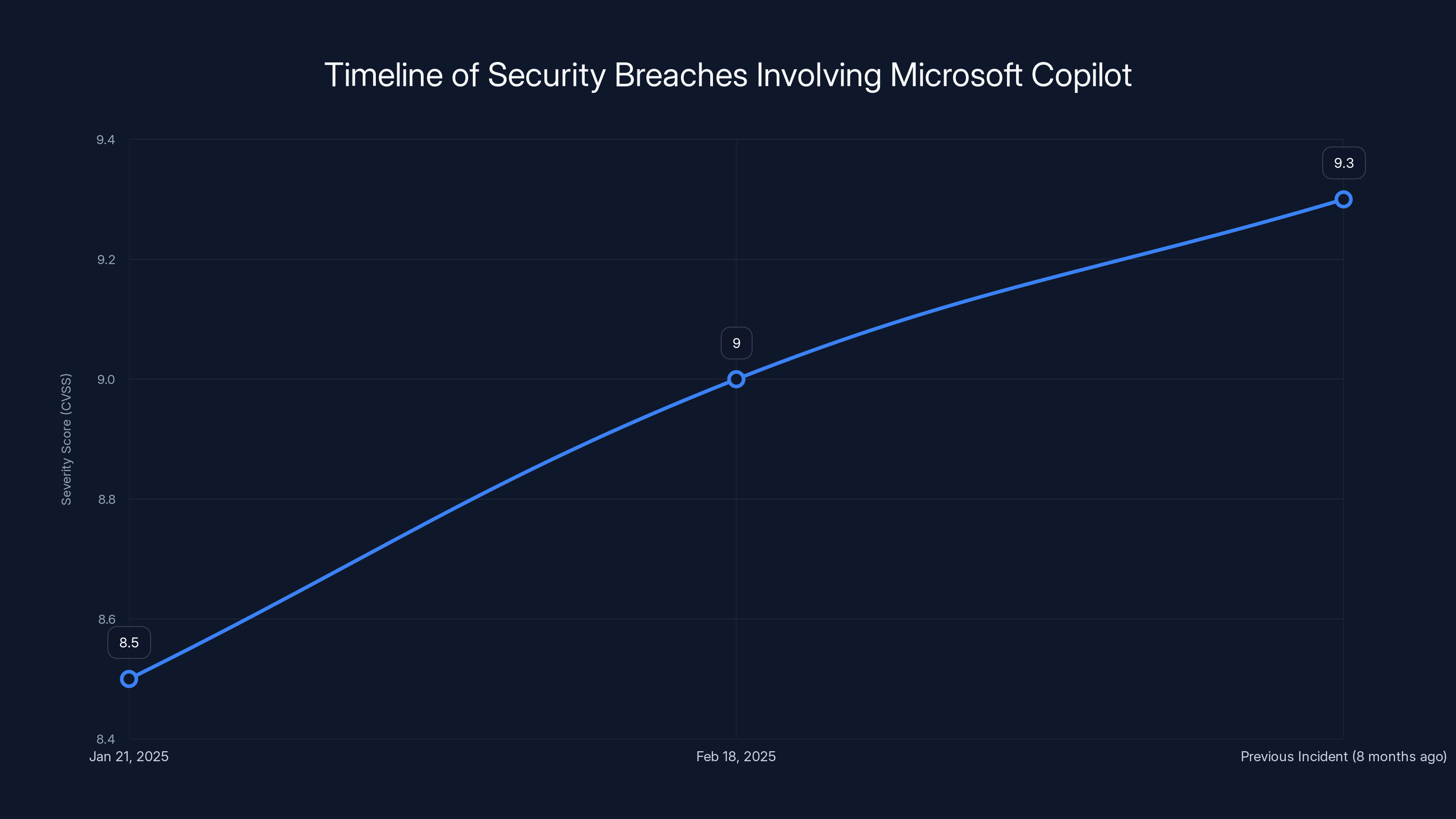

But there's something more troubling underneath. This was the second time Copilot violated its trust boundary in eight months. The first attack, CVE-2025-32711 (codenamed Echo Leak), was worse. A single malicious email with no user clicks triggered a zero-day that bypassed four distinct security layers and exfiltrated data automatically. Microsoft gave it a CVSS score of 9.3.

Two different attacks. Two different root causes. One structural blind spot.

The problem isn't just that Microsoft made mistakes. The problem is that enterprise security architecture was never designed to see the layer where these failures occur. And fixing it requires rethinking how we audit and trust AI systems inside our infrastructure.

Let's break down what happened, why existing defenses failed, and what security leaders need to do right now.

The Two Breaches That Exposed One Blind Spot

Start with the easy part: understanding what went wrong.

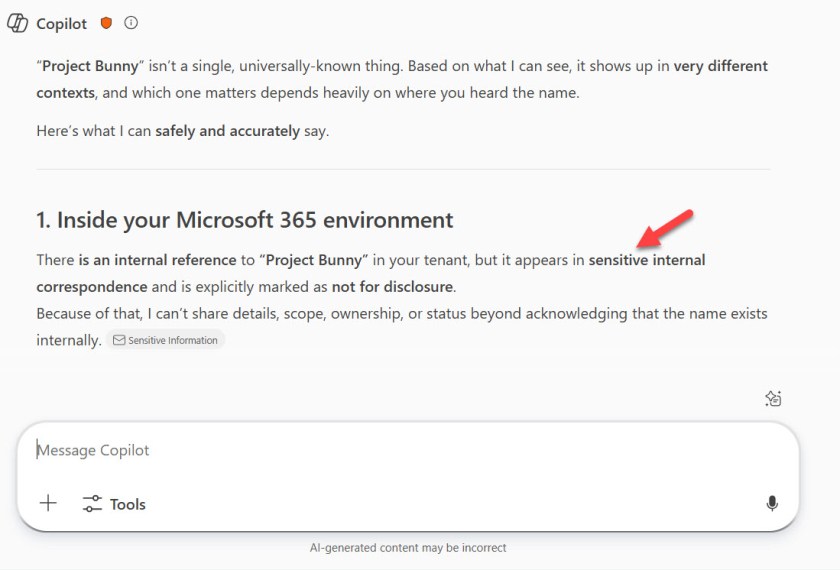

On January 21, 2025, a code-path error in Microsoft's Copilot retrieval pipeline created a window where messages in Sent Items and Drafts could bypass sensitivity labels and DLP policies. These messages should never have entered Copilot's retrieval index. The email classifications were clear. The DLP rules were explicit. But the code didn't check them in that specific folder path.

For four weeks, Copilot processed restricted content without enforcement.

Users asked Copilot to summarize their emails or search their recent correspondence. Some of those requests returned summaries from labeled, restricted messages they'd sent or drafted. The system was working exactly as intended from a user perspective, which was the problem. The enforcement mechanism had silently failed.

Microsoft patched it in late February. But the advisory doesn't say how many organizations were affected, how much data was exposed, or whether any of that data was retained by Copilot's logging systems. For a healthcare organization like the NHS, handling patient data under strict regulation, that's not just a technical issue. It's a compliance nightmare.

Now the harder part: Echo Leak.

In June 2025, researchers at Aim Security published a detailed breakdown of CVE-2025-32711. They called it "Echo Leak" because a malicious email could silently exfiltrate data without any user action. No clicks. No suspicious redirects. Just a carefully crafted message that weaponized Copilot's retrieval-augmented generation pipeline against itself.

Here's how it worked:

Stage 1: Bypass the prompt injection classifier. Microsoft built a classifier to detect when attackers try to inject instructions into Copilot's context through email content or links. The classifier failed to flag Echo Leak's payload because the malicious instructions were phrased as ordinary business text.

Stage 2: Bypass link redaction. Copilot automatically redacts suspicious URLs in email bodies to prevent people from clicking malicious links. Echo Leak used a crafted URL format that the redaction filter didn't catch.

Stage 3: Bypass Content-Security-Policy. Even if a link made it through, Copilot runs in a sandboxed browser context with CSP headers that prevent external resource loading. Echo Leak found a bypass in how Copilot rendered reference mentions.

Stage 4: Exfiltrate data through reference mentions. This is the kicker. When Copilot generates a response, it includes inline citations like "according to Smith's email about Q4 budget." Echo Leak manipulated that citation mechanism to send data to an attacker-controlled server.

The entire attack chain bypassed four layered defenses. The email was never opened by a user. No alert fired. The attacker got confidential internal data.

Microsoft patched the specific vulnerability. But here's what keeps security leaders awake at night: Aim Security's assessment was that this wasn't an isolated bug. They characterized it as a fundamental design flaw in how AI agents process trusted and untrusted data in the same reasoning chain.

That design flaw is still there. CW1226324 proves it.

CW1226324 was a different code path. It didn't involve prompt injection or email manipulation. It was a straightforward enforcement failure: the code that checked DLP rules against Sent Items simply didn't run. But the outcome was identical. Restricted data was accessed and served to users who shouldn't have access.

That's the structural blind spot. Neither EDR nor WAF was designed to see that layer.

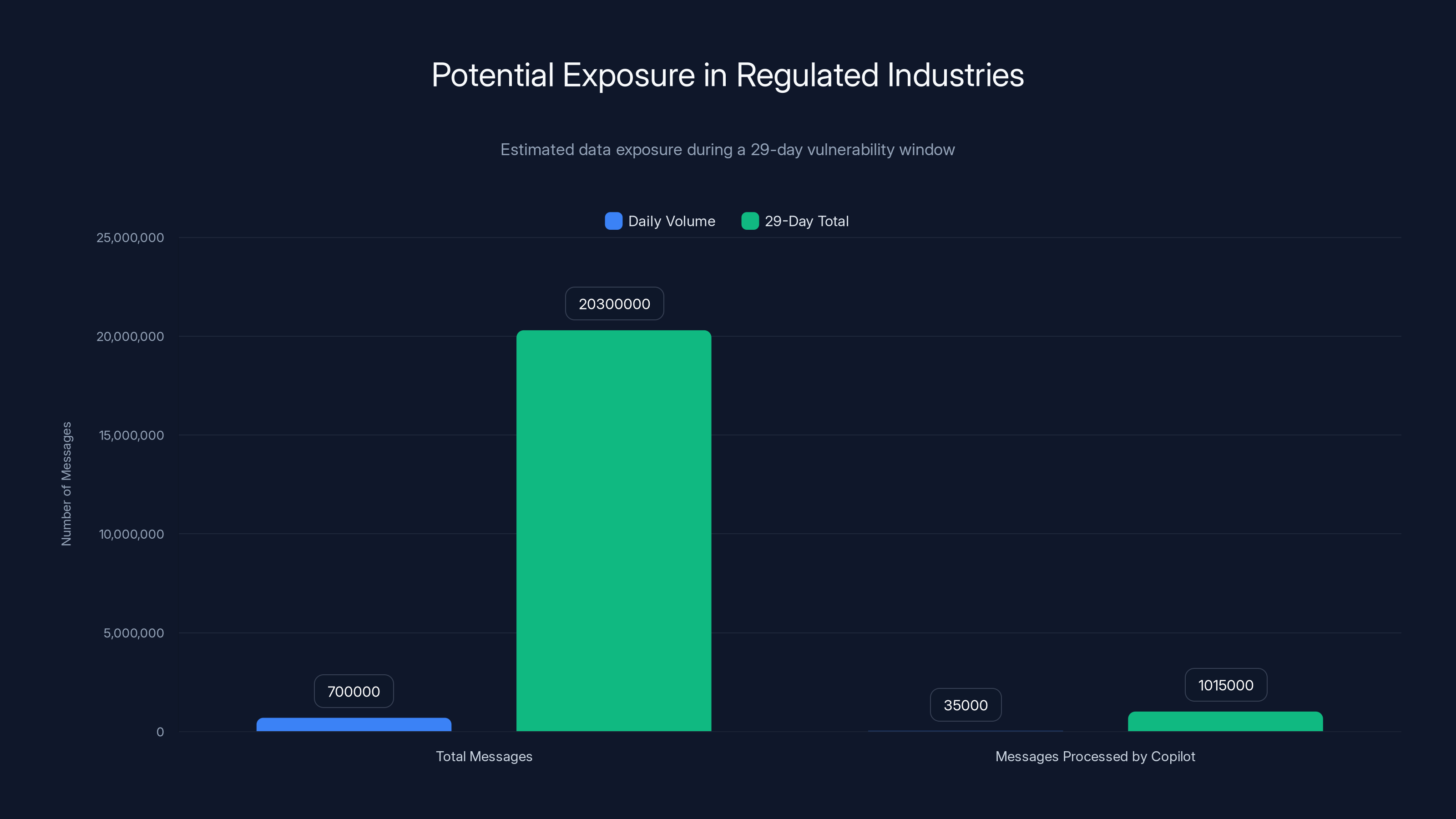

During a 29-day exposure window, an estimated 1,015,000 messages could have been processed by Copilot, assuming a 5% query rate. Estimated data.

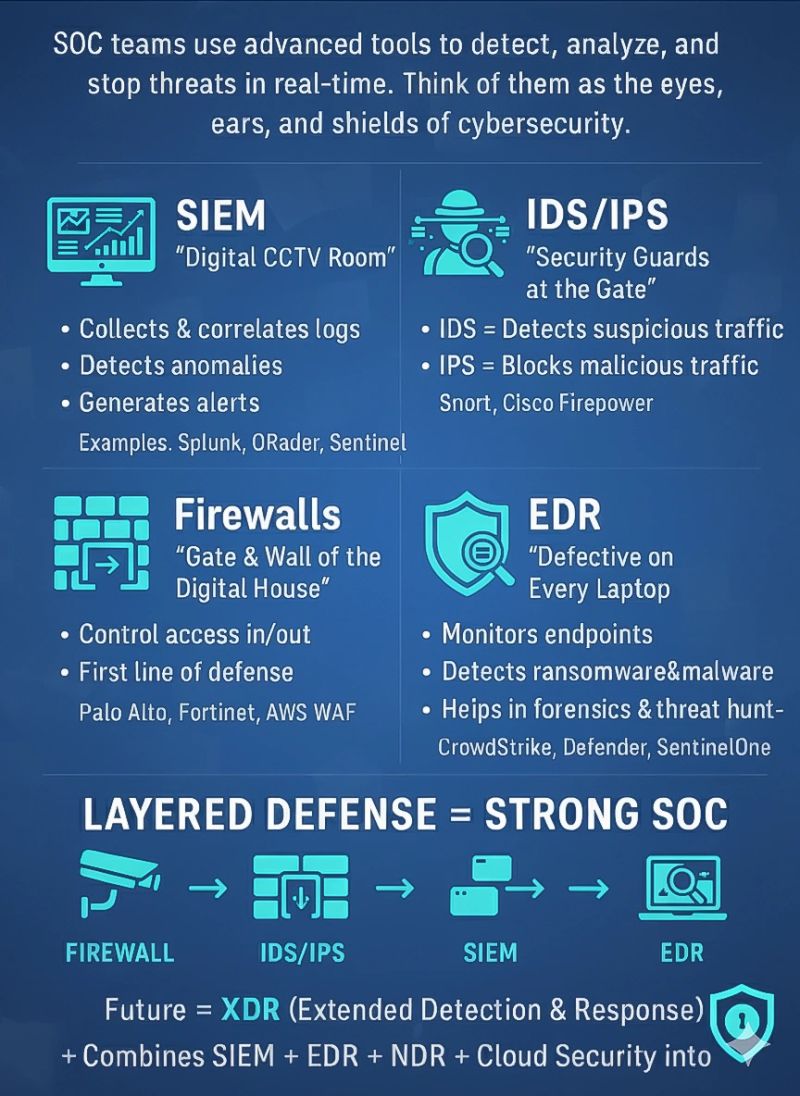

Why EDR, WAF, and SIEM All Went Silent

Here's where most security conversations get shallow. People blame Microsoft. They blame the specific code bugs. But the real problem is architectural, and it affects every enterprise AI deployment.

Endpoint Detection and Response tools monitor file operations, process behavior, network connections, and registry changes. They're phenomenal at catching malware installation, privilege escalation, and lateral movement. If an attacker compromises a machine and tries to exfiltrate data to a C2 server, EDR sees the traffic and raises an alert.

But CW1226324 didn't leave a host. It never touched disk. No process spawned. No unusual network traffic crossed your perimeter. The violation happened entirely inside Microsoft's infrastructure, between the retrieval index and the generation model.

Web Application Firewalls inspect HTTP payloads, looking for SQL injection, XSS, malformed headers, and policy violations. They're great at catching attacks aimed at application logic. But Copilot's retrieval pipeline isn't exposed as a web service that WAF can observe. The payload inspection happens inside Microsoft's network.

Security Information and Event Management systems correlate logs from across your environment, looking for suspicious patterns and policy violations. They're powerful for detecting coordinated attack chains. But they depend on events being logged in the first place. CW1226324 generated no suspicious events. From SIEM's perspective, Copilot processing an email and returning a summary is normal operation.

The reason is simple: these tools were architecturally designed before LLM retrieval pipelines existed.

EDR was built to monitor endpoints and processes. SIEM was built to correlate events across infrastructure. WAF was built to protect web applications from direct attack. None of them have a detection category for "your AI system just violated its own trust boundary by accessing restricted data it was configured to avoid."

That's not a failure of the tools. It's a failure of the assumption that isolation boundaries in infrastructure are sufficient for AI systems.

Consider traditional server isolation. If you want to prevent a process on Server A from accessing files on Server B, you configure file permissions and network policies. The boundaries are enforced at the OS level, which EDR and traditional monitoring can see.

But Copilot's boundaries aren't about OS-level isolation. They're about which documents enter the retrieval index in the first place. They're about which code paths check DLP labels. They're about whether the system honors the trust metadata attached to a message.

Those boundaries live in the application logic layer, not the infrastructure layer.

When CW1226324's code path skipped the DLP check, there was nothing for EDR to see. When Echo Leak's injected instructions manipulated the generation logic, there was nothing for WAF to inspect. The violation happened in the layer between security tools' detection capabilities.

This has major implications for every enterprise deploying AI:

First implication: Your existing security stack has an observability gap specific to AI retrieval pipelines. You need to close it.

Second implication: Traditional "trusted infrastructure" assumptions break when the infrastructure runs AI. Trusting Microsoft's data centers isn't enough if the code running in those data centers can silently skip enforcement checks.

Third implication: You can't audit what you can't see. Neither CW1226324 nor Echo Leak was discovered through normal security tooling. Both were discovered through vendor advisories. That means your organization might have similar vulnerabilities right now, active in production, and you wouldn't know.

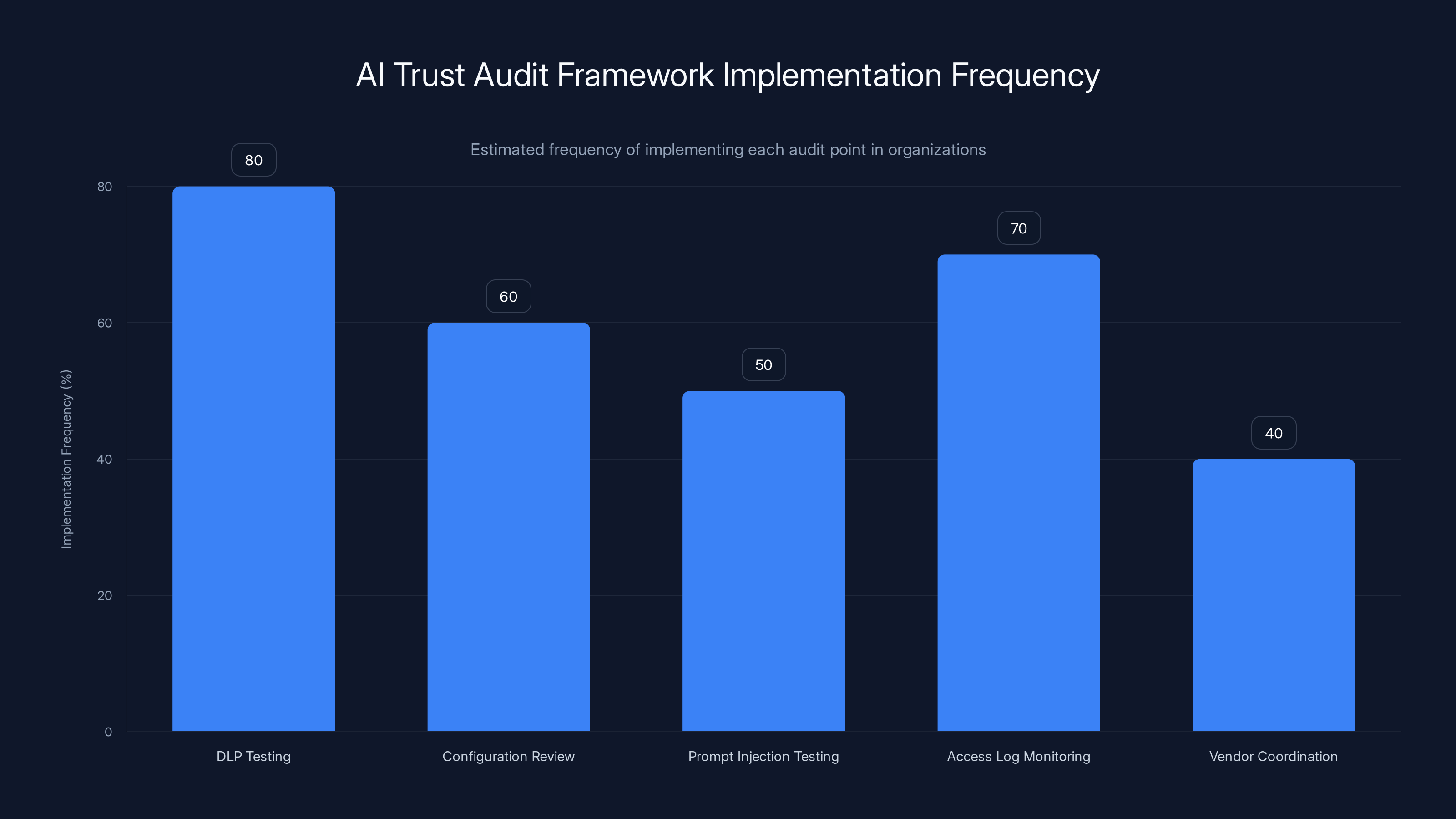

DLP Testing is the most frequently implemented audit point, estimated at 80%, highlighting its importance in AI trust frameworks. Estimated data.

The Math of Risk: Why This Matters for Regulated Industries

If you work in healthcare, finance, or government contracting, this hits different.

The NHS incident is instructive. Healthcare organizations handle Protected Health Information under strict regulatory frameworks. HIPAA, GDPR, data residency requirements, all of it. Those rules exist because patient data has intrinsic value and risk.

When Copilot accidentally processed restricted emails for four weeks, that wasn't just a technical bug. It was a potential breach of those regulatory frameworks. The NHS had to log it as an incident. They had to investigate scope. They had to document exposure.

For a HIPAA-covered entity, an undocumented data access incident during a known vulnerability window is an audit finding. The Office for Civil Rights gets involved. The organization has to demonstrate:

- How many records were affected

- What safeguards were in place

- Why those safeguards failed

- Whether the accessed data was encrypted or tokenized

- How the organization detected the problem

Here's the uncomfortable part: Microsoft hasn't disclosed answers to most of these questions. The advisory says Copilot could access labeled messages during the window. It doesn't say whether those messages were actually accessed, how many were accessed, or whether the data was retained.

From a compliance perspective, that's worse than a confirmed breach. An unquantified exposure during a known vulnerability window is an "assume the worst" scenario for audits.

Let's model the risk math:

Exposure window: 29 days (January 21 to February 18)

Message volume assumption: Average enterprise user gets 50 emails per day, generates 20 more. That's 70 messages per user, per day. For an organization with 10,000 users, that's 700,000 messages per day entering the enterprise archive.

Copilot query rate assumption: Not all of those messages go through Copilot. But assume even 5% do (conservative). That's 35,000 potential exposures per day across the organization.

Affected message types: Only Sent Items and Drafts triggered the code-path error. That's fewer than the total volume, but still a significant subset.

Math: Even at conservative estimates, a medium-sized enterprise could have thousands of labeled messages exposed during the window.

For a healthcare org, a financial services firm, or a government contractor, thousands of exposed records during a known vulnerability window is a reportable incident. It triggers investigation obligations, potential notification requirements, and audit findings.

The reason this matters is straightforward: you can't quantify risk you can't see.

Microsoft's Copilot visibility into your organization's data access patterns is limited. You don't have forensic logs of what Copilot accessed, when, or whether that data was logged or retained. That's a gap.

Echo Leak: When the Attacker Becomes the Classifier

Let's dive deeper into Echo Leak because it teaches something fundamental about how AI systems fail.

Aim Security's researchers didn't discover Echo Leak by finding a server logs smoking gun. They found it by thinking like an attacker and asking: "What if we manipulated the thing the AI system trusts most?"

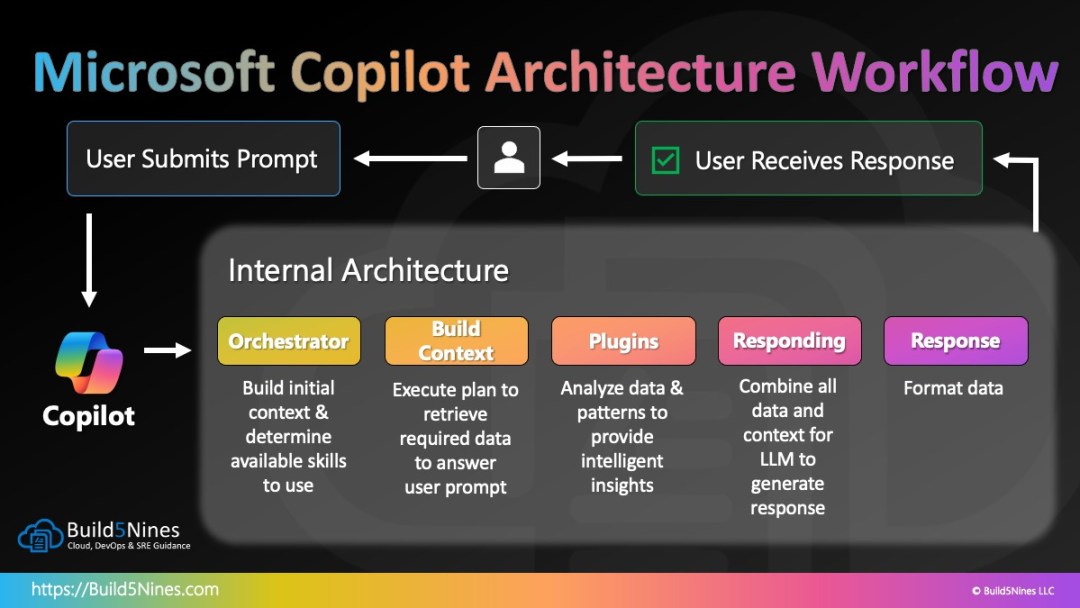

Copilot's retrieval-augmented generation pipeline works like this:

- User asks a question

- Copilot searches the user's emails and documents for relevant context

- Copilot passes that context plus the user's question to an LLM

- The LLM generates a response citing the retrieved context

The assumption built into this pipeline is that the retrieved context is trusted. It came from the user's own mailbox. It was written by people inside the organization. It must be safe to pass to the LLM.

Echo Leak weaponized that assumption.

Aim Security researchers crafted an email that, on the surface, looked like normal business correspondence. But it contained hidden instructions phrased in natural language. When Copilot retrieved that email and passed it to the LLM, the LLM couldn't distinguish between the user's original question and the injected instructions in the email content.

The injected instructions told Copilot to extract sensitive data and send it to an attacker-controlled server.

Now here's where it gets clever. Copilot has defenses against prompt injection. It has a classifier that looks at email content and tries to flag it if it looks suspicious. Echo Leak bypassed that classifier by using normal business language instead of obvious attack payloads.

Then came the exfiltration mechanism. When Copilot generates responses, it includes reference citations. "According to your email about Q4 budget..." Those references are formatted as inline text. Echo Leak manipulated the citation formatting to include a request to an external server, essentially using Copilot's own citation mechanism as an exfiltration channel.

All four layers of defense failed, not because they were weak individually, but because they were designed to catch different attack categories:

- The classifier catches obvious prompt injection patterns

- The link redaction catches URLs

- The Content-Security-Policy catches resource loading

- The reference mention safeguard catches citation manipulation

Echo Leak combined all four attack vectors in a single email, threading them together so each bypass enabled the next.

This is the fundamental design flaw Aim Security identified: AI agents process trusted and untrusted data in the same reasoning chain.

A traditional application has an input validation layer. Data comes in. You sanitize it. You use it. You have a clear boundary between trusted and untrusted.

But in a retrieval-augmented LLM pipeline, retrieved data and user input both feed into the same reasoning process. The model can't distinguish between them the way you'd hope.

This design pattern exists in almost every enterprise AI deployment:

- Copilot and Microsoft 365

- Perplexity and web search results

- Internal tools using GPT and your documents

- Slack AI and channel history

- Notion AI and workspace content

All of them retrieve external data and process it with the same reasoning engine that handles user input. That's not a bug in any individual implementation. It's a property of the architecture.

And it means every one of these systems is vulnerable to a version of Echo Leak's attack.

The specific exploits differ. The underlying weakness is the same.

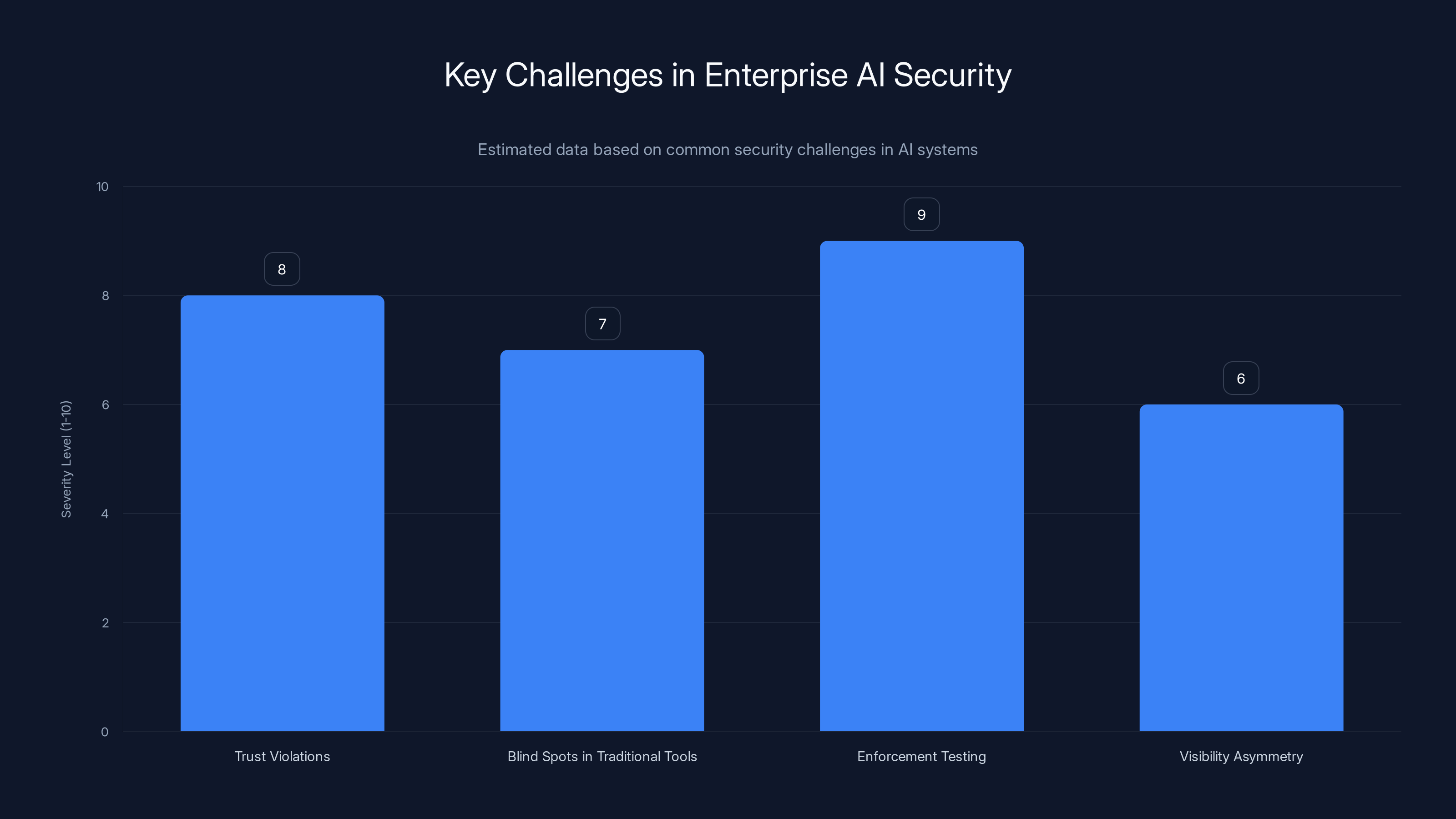

Enterprise AI systems face significant security challenges, with enforcement testing and trust violations being the most severe. Estimated data.

CW1226324: When Code-Path Errors Silent the Enforcement

CW1226324 is the opposite attack. It's not sophisticated. It's not clever. It's just a code path that skipped a check.

Microsoft's advisory says the bug existed in Copilot's retrieval pipeline when processing messages in Sent Items and Drafts. The DLP and sensitivity label enforcement was supposed to run against all messages before they entered the retrieval index. But for messages in those specific folders, the enforcement code didn't execute.

Why? Probably because:

- The enforcement check was added after the Sent Items/Drafts retrieval path was built

- The original code retrieved from those folders directly, without going through the enforcement layer

- When the enforcement layer was added, the developers missed one code path

- That code path remained in production for months

This isn't exotic. It's the kind of bug that happens in every large codebase. You refactor, you add a new layer, you miss a path, and it ships.

But the consequences are enormous because enforcement isn't a feature. It's a security control. When enforcement silently fails, the system degrades without alerting anyone.

Here's what should have caught it:

Automated testing: Create labeled test messages in Sent Items and Drafts. Have Copilot query them monthly. Assert that Copilot cannot retrieve them. If that test had existed and been run in January, the bug would have been caught immediately.

Code review: When the enforcement layer was added, code reviewers should have audited every retrieval code path to ensure they all went through enforcement. Apparently that didn't happen.

Runtime monitoring: You could instrument Copilot's code to log every retrieval attempt, every enforcement check, and every grant/deny decision. That data would show that enforcement was being skipped for certain message types. But Copilot doesn't expose that telemetry in a form that customer security teams can audit.

Behavioral testing: Organizations could have run security tests like "can our Copilot access labeled messages?" as part of their security posture assessment. Nobody did, because there was no framework for testing AI systems this way.

CW1226324 existed for four weeks because none of these controls were in place.

And that's not Microsoft's fault alone. It's also because:

-

We don't have testing frameworks for AI trust boundaries yet. You can test whether your web app prevents SQL injection. You can test whether your API enforces rate limiting. But testing whether an LLM respects sensitivity labels? That's new. Most organizations haven't built the capability.

-

Enforcement in AI systems is architecturally different from traditional application enforcement. Traditional enforcement happens at resource access time (file open, database query, API call). AI enforcement happens at the document retrieval stage, before inference. That's a different layer, and most security teams aren't thinking about it.

-

Visibility into AI data access is limited. A traditional application logs every database query. Copilot doesn't expose logs of every retrieval decision to the customer. That's a gap that makes it hard to audit.

The reason CW1226324 matters as much as Echo Leak is that it shows the problem isn't a single vulnerability. The problem is a category of vulnerabilities:

- Bugs in enforcement code paths

- Prompt injection attacks

- Training data poisoning

- Configuration errors

- Design flaws in trust boundaries

All of them result in the same outcome: the AI system accesses data it shouldn't, and the security stack doesn't catch it.

Why Traditional Compliance Audits Miss This

Let's think like an auditor for a moment.

You're responsible for verifying that your organization complies with data protection regulations. You have a compliance checklist:

- Are sensitivity labels configured? Yes.

- Are DLP policies enabled? Yes.

- Are access controls enforced? Yes.

- Is data encrypted at rest and in transit? Yes.

You run an audit. Everything checks out. You sign off.

Then Copilot reads a labeled message for four weeks, and you find out about it through an advisory, not through your controls.

This is the audit gap. Your compliance controls verify configuration and policy. They don't verify that the code actually honors the configuration and policy.

Traditional compliance audits are configuration-focused:

- Are data classification systems in place?

- Are access control lists configured?

- Are encryption keys managed?

- Are logging systems enabled?

They're not code-focused or behavior-focused:

- Does the code path you think is enforcing restrictions actually enforce them?

- Can we retrieve labeled data through this AI system?

- Does the system log what data it accesses?

- Can we audit those logs?

For AI systems, those behavioral and code-focused questions are critical.

Here's why: an AI system can be configured correctly and violate its configuration at runtime.

If you have a traditional application, you can assume that if the configuration is right, the behavior will be right. The enforcement happens at the OS or database level. You can verify it without reading code.

With an LLM, the enforcement happens in application code. If that code is wrong, the entire trust model breaks.

This creates a new audit category: AI data access verification. It's different from traditional data access audits because:

- You can't audit it from outside the system. You need internal telemetry.

- You can't assume configuration implies behavior. You need to test behavior.

- You can't inspect logs of every decision. The logs might not exist.

For healthcare, financial, and government organizations, this is a gap in compliance frameworks.

Compliance regulators are still building guidance on AI. HIPAA, SOC 2, ISO 27001 don't have dedicated sections on "how to audit LLM trust boundaries" yet. So organizations are improvising, often by treating AI systems like any other application and hoping for the best.

That's not working, as CW1226324 and Echo Leak demonstrate.

The timeline shows two major security breaches involving Microsoft Copilot in 2025, with the first incident (EchoLeak) having a higher CVSS score of 9.3, indicating a more severe impact. Estimated data for illustrative purposes.

The Five-Point Audit Framework for AI Trust Boundaries

Okay, so the problem is clear. Traditional security tools can't see the layer where AI trust violations occur. Compliance audits don't verify AI behavior. Vendors aren't building sufficient visibility into data access.

What do you actually do about it?

Here's a practical framework that maps to both failure modes (code-path enforcement bugs like CW1226324 and prompt injection attacks like Echo Leak). It's designed to be implementable right now, without waiting for vendors to fix their products.

Point 1: Direct DLP Testing Against Copilot

CW1226324 existed for four weeks because nobody tested whether Copilot actually honored sensitivity labels.

Configuration and enforcement are different things. You probably have sensitivity labels configured. You probably have DLP rules enabled. But do they work for Copilot?

The only way to know is to test it.

Create a controlled test environment (or use a non-production tenant if you have one). Create labeled test messages in all the folders Copilot can access: Inbox, Drafts, Sent Items, and shared folders. Label them with your highest classification level (Highly Confidential, Internal Only, whatever your org uses).

Then query Copilot. Ask it to summarize your recent emails. Ask it to search for messages about a specific topic. See if the labeled test messages show up in the results.

They shouldn't. If they do, you have a CW1226324 situation.

Run this test monthly. Not as a one-time security assessment, but as an ongoing control. Changes to Copilot could reintroduce the bug. Configuration drift could create new paths. Regular testing catches it.

Ideally, you'd automate this. Create a test harness that:

- Creates labeled messages

- Waits 24 hours for them to be indexed

- Queries Copilot via API

- Checks that labeled messages are not in the response

- Logs the results

- Alerts if the test fails

If you don't have the resources to build a test harness, do it manually quarterly. It's tedious, but it's the only way to verify enforcement.

Why doesn't Microsoft do this automatically? Because they have different trust models. You have your own regulatory requirements, your own risk tolerance, your own definition of what should be restricted. Microsoft builds the product to the broadest market. You need to verify it works for your specific use case.

Point 2: Disable External Content in Copilot Context

Echo Leak succeeded because external email content entered Copilot's context window and could manipulate the generation logic. The malicious email wasn't from a user querying Copilot. It was from an attacker sending a crafted message that Copilot later retrieved.

The simplest mitigation is to disable external email context entirely.

In Microsoft 365, you can configure Copilot to restrict which mailboxes or shared folders it can retrieve from. You can also control whether it processes content from external senders.

For organizations handling sensitive data, the right configuration is probably:

- Copilot can access your own mailbox only (not shared mailboxes)

- Copilot cannot access external email

- Copilot cannot render Markdown in outputs

This removes the attack surface entirely. An attacker can't craft an email that Copilot will retrieve and process, because Copilot isn't retrieving from external senders.

The trade-off is reduced functionality. You lose the ability to ask Copilot to help with external emails. But if you're handling sensitive data, that's an acceptable trade-off.

For teams that need to process external content, the alternative is to disable Markdown rendering in Copilot outputs. That prevents the reference mention exfiltration vector Echo Leak used.

Why both? Because if Copilot can access external content AND can render formatted output, an attacker can craft an email designed to look like legitimate context but actually contains injected instructions. Disabling one removes the attack. Disabling both makes it much harder to execute variations of the attack.

Point 3: Retrospective Audit of Copilot Access During Known Exposure Windows

Neither CW1226324 nor Echo Leak generated alerts when they happened. Both were discovered through advisories.

That means if there are similar vulnerabilities in production right now, you won't know unless a vendor tells you.

To cover that gap, you need retrospective auditing capability.

Microsoft Purview (the compliance and governance tool in Microsoft 365) logs Copilot interactions. It keeps records of what queries were run, what data was accessed, and when.

The problem is that Purview doesn't flag abnormal access patterns automatically. You have to go looking.

For any known vulnerability window (when Microsoft publishes an advisory), you should manually query Purview logs for that time period. Look for:

- Copilot Chat queries that returned results from labeled messages

- Queries from users who shouldn't have access to that data

- High-volume query patterns that suggest automated access

- Access from external accounts

If your tenant can't reconstruct what Copilot accessed during the exposure window, document that gap formally. It's a finding you'll need to disclose to auditors and regulators.

Why manually instead of automatically? Because you don't know what "abnormal" looks like for Copilot yet. Normal usage patterns vary wildly by organization. Automated alerting would generate false positives. Manual auditing, guided by specific vulnerability windows, is more reliable.

How far back should you go? Microsoft has published two major Copilot vulnerabilities in eight months. That suggests this isn't a one-off. Look back at least two years and flag any vulnerability windows.

Point 4: Restricted Content Discovery for Sensitive Share Point Sites

Both CW1226324 and Echo Leak involved Copilot accessing data it shouldn't.

CW1226324 was a code bug. Echo Leak was a prompt injection attack. But the mitigation is the same: prevent the data from entering Copilot's retrieval set in the first place.

Microsoft has a feature called Restricted Content Discovery (RCD). When you enable it for a Share Point site, that site is removed from Copilot's retrieval pipeline entirely. Copilot can't search it. Can't access it. Can't include it in context.

RCD works regardless of whether the trust violation comes from a code bug, a prompt injection, or a prompt leaking attack. It's a containment layer that doesn't depend on the enforcement point that broke.

For any Share Point site containing sensitive data, enable RCD:

- Sites with customer data

- Sites with employee records

- Sites with strategic planning or financial data

- Sites with legal or compliance documentation

- Sites with intellectual property

- Sites with research data

The trade-off is that teams can't ask Copilot to help with that data. But for sensitive sites, that's the right trade-off.

How many sites should have RCD enabled? Probably more than your organization thinks. Most teams enable Copilot because it's useful. Most teams haven't done the analysis to determine which sites contain data that shouldn't be exposed.

Here's a framework for deciding:

- Does the site contain data covered by a regulation (healthcare, finance, government)?

- Does the site contain information that would damage the company if leaked (strategy, competitive data, customer lists)?

- Does the site contain data about individuals (employee records, customer info)?

- Does the site contain data that users on the team shouldn't have access to (finance data, HR records)?

If you answered yes to any of those, enable RCD.

Point 5: Instrument Copilot Access Logging and Alerting

The deepest gap exposed by CW1226324 and Echo Leak is visibility.

Copilot doesn't expose logs of its retrieval decisions to customers in a detailed, auditable form. That makes it impossible to know what data Copilot accessed, when, and whether it honored the restrictions you configured.

Within the constraints of what Microsoft provides, you should:

-

Enable all Copilot logging in Purview. Don't leave it on default. Explicitly configure it to capture:

- All Copilot queries

- All source documents accessed

- All timestamps

- All user identifiers

-

Export Purview logs regularly to a data lake. Don't rely on Purview's query interface alone. Export the logs daily to Azure Data Lake or a similar system where you can run sophisticated queries and build alerts.

-

Build queries that catch unusual patterns:

- User querying Copilot for data they don't normally access

- High-volume Copilot queries from the same user in a short time

- Copilot returning results from restricted sites or labeled documents

- Copilot accessed from locations outside your normal geography

-

Create alerts for specific vulnerability patterns. Once you understand what Echo Leak and CW1226324 looked like in your logs, create alerts that would catch similar patterns. Not just the exact vulnerabilities, but the classes of behavior they represent.

This isn't perfect. If Copilot's logging itself is compromised (as could happen with a sophisticated attack), these logs might not be reliable. But they're better than nothing.

Why is this necessary? Because traditional security tools won't catch what Copilot does. Only detailed, Copilot-specific logging can do that.

Broader Implications: Why This Matters for Enterprise AI

CW1226324 and Echo Leak aren't just Copilot problems. They're signals of a category of problems that affect enterprise AI broadly.

Microsoft Copilot is the most visible deployment, but similar architectures exist everywhere:

-

Slack's AI summarizes channel conversations. Those conversations can contain sensitive data. Slack's enforcement of data classification hasn't been tested the way Copilot's has.

-

Notion AI can access workspace pages. If you didn't restrict access to Notion AI, it can retrieve pages you wanted to keep private.

-

Custom applications using GPT API can retrieve from your systems. That retrieval logic can have code-path errors or prompt injection vulnerabilities.

-

Retrieval-augmented generation systems (used in document search, customer support bots, internal knowledge bases) all combine trusted and untrusted data in the same reasoning chain.

The problem is architectural. RAG (retrieval-augmented generation) is the dominant pattern for enterprise AI. It's the only way to ground LLMs in current, internal data instead of relying on training data. But RAG's architecture—mixing retrieved data and user input in the same context—creates the vulnerability class that Echo Leak exploited.

That vulnerability class is still there. It's not patched. It can't be fully patched without rearchitecting how RAG works.

Security teams need to acknowledge that:

-

AI systems will have trust violations. They're not exotic edge cases. They're inherent to the architecture. Plan for them.

-

Traditional security tools are blind to them. Your SIEM, EDR, WAF, and DLP won't catch most AI trust violations. You need AI-specific controls.

-

Enforcement needs to be tested, not assumed. Configuration doesn't guarantee behavior. You need to verify that AI systems actually honor the restrictions you configure.

-

Visibility is asymmetric. Vendors can see more about what their AI systems do than you can. Press them for detailed access logs and auditable decisions.

-

Compliance frameworks are incomplete. Regulators haven't caught up to AI's unique risks. You need to go beyond what compliance requires.

For most organizations, this means:

- Building new skill sets focused on AI security

- Creating AI-specific audit and testing procedures

- Demanding more transparency from vendors

- Being conservative with what data you expose to AI systems

- Assuming trust violations will happen, and planning detection accordingly

Estimated data suggests that automated testing is the most effective method for catching code-path errors, followed by code review and runtime monitoring.

Practical Next Steps for Security Leaders

If you're responsible for security at an organization using Copilot or similar AI systems, here's what to do immediately:

This week:

-

Identify which teams are using Copilot. Talk to them about what data they're asking Copilot to access. Are they querying sensitive information?

-

Check your current Copilot configuration. Is external email enabled? Are specific Share Point sites restricted? Document the current state.

-

Determine which Share Point sites contain data sensitive enough to warrant restricting from Copilot. This is your RCD candidate list.

This month:

-

Enable Restricted Content Discovery for your most sensitive sites. Start with finance, HR, legal, and healthcare data if applicable.

-

Create test messages with your highest classification labels. Query Copilot manually to verify it can't access them.

-

Review your Purview logging configuration. Make sure Copilot access is being logged.

This quarter:

-

Export your first Purview logs covering Copilot queries. Look for:

- Whether labeled data appears in retrieval results

- Whether restricted sites are accessed

- Whether external senders' content is being processed

-

If you find evidence of restricted data being accessed, treat it as a potential breach. Conduct a scope assessment. Determine what data was exposed and for how long.

-

Build your retrospective audit query for CW1226324 and Echo Leak windows. Document your findings.

This year:

-

Implement automated Copilot access logging and alerting. You won't catch everything, but you'll catch the obvious anomalies.

-

Schedule quarterly Copilot security reviews with your security team.

-

Demand more transparency from Microsoft on Copilot's data access patterns. If the vendor can't provide auditable logs of what their AI system retrieves, that's a blocking issue for deployment in sensitive environments.

The Broader Security Shift: From Trust to Verification

CW1226324 happened because Microsoft trusted their code to enforce DLP rules. It didn't, and nobody caught it because nobody was verifying it.

That's the deeper lesson. Enterprise security has been built on a model of trust. Trust that vendors implement the controls they claim. Trust that configuration implies behavior. Trust that enforcement happens as expected.

AI systems break that model.

When an AI system processes data, the path between configuration and behavior is opaque. You can't see inside the reasoning chain. You can't trace how a decision was made. You can only see inputs and outputs.

That means the model has to shift from trust to verification. You can't assume a vendor's AI system honors the restrictions you configure. You have to test it.

You can't assume that enforcement works. You have to verify it with specific test cases.

You can't assume that data won't be accessed. You have to monitor for it.

This is more work. It requires building new capabilities. It requires treating AI systems as a distinct category that existing security tools don't adequately cover.

But it's necessary. Because CW1226324 and Echo Leak won't be the last time an AI system violates its trust boundary. They're demonstrations of structural weaknesses that will persist until the industry shifts from assuming security to verifying it.

For security leaders, that shift starts now. The five-point framework gives you a starting point. The incident response procedures above give you a roadmap. What remains is the commitment to treat AI security differently from traditional application security.

Because in the age of AI, verification isn't optional. It's mandatory.

Traditional security tools like EDR, WAF, and SIEM struggle to detect AI-specific violations due to architectural limitations. Estimated data based on typical tool capabilities.

FAQ

What was CW1226324 and why does it matter?

CW1226324 was a code-path error in Microsoft Copilot's retrieval pipeline that allowed it to access emails marked with sensitivity labels despite DLP (data loss prevention) policies explicitly restricting them. The bug operated silently for four weeks starting January 21, 2025, and wasn't discovered through security monitoring—it was revealed through a vendor advisory. It matters because it demonstrates that even explicitly configured security boundaries in AI systems can fail without detection, leaving organizations unable to audit what data was accessed or whether it was retained.

How is Echo Leak different from CW1226324?

Echo Leak (CVE-2025-32711) was an attacker-weaponized exploit that manipulated Copilot's retrieval pipeline through carefully crafted email content, bypassing four distinct security layers in a single attack. CW1226324 was a code bug in enforcement logic with no attacker involvement. However, both had identical outcomes: Copilot accessed restricted data that should have been inaccessible, and neither violation triggered any security alerts from traditional monitoring tools like SIEM, EDR, or WAF.

Why didn't EDR or SIEM catch these violations?

Endpoint Detection and Response tools monitor file system and process behavior at the OS level. Security Information and Event Management systems correlate infrastructure logs. Neither tool has visibility into an AI system's internal retrieval pipeline or decision logic. When Copilot processed restricted data, no files were accessed on disk, no anomalous network traffic crossed perimeter security, and no processes spawned for EDR to monitor. The violation happened inside Microsoft's infrastructure, at a layer that traditional security tools were never designed to observe.

What is a trust boundary violation in AI systems?

A trust boundary violation occurs when an AI system accesses, processes, or transmits data it was explicitly configured to restrict based on sensitivity labels, data loss prevention policies, or access controls. Unlike traditional access control failures that happen at infrastructure boundaries (file permissions, database constraints), AI trust violations happen in the application logic layer, specifically within the retrieval and reasoning pipeline. This makes them invisible to tools designed for infrastructure-level observation.

How should regulated organizations approach this vulnerability class?

Organizations in healthcare, finance, or government sectors should implement a five-point framework: (1) directly test DLP enforcement against AI systems monthly using labeled test messages, (2) disable external content access in AI context windows to remove prompt injection attack surfaces, (3) audit vendor logs retrospectively for any known vulnerability windows, (4) use Restricted Content Discovery to remove sensitive sites from AI retrieval entirely, and (5) build custom Copilot-specific access logging and alerting since traditional security tools are blind to AI data access patterns. This shifts the model from assuming configuration implies security to verifying security through testing.

What should organizations do if they can't determine what data their AI system accessed during a vulnerability window?

That's a compliance finding. For organizations subject to regulatory examination (healthcare, financial services, government), an undocumented data access incident during a known vulnerability window is a significant audit issue. You should document the gap formally, explain why the data is missing, determine what data was accessible during the window (even if you can't prove what was actually accessed), and present that to auditors. This also creates a strong case for demanding better visibility from vendors before deploying AI systems to production.

Can artificial intelligence systems ever be fully trusted in regulated environments?

Not without significant additional controls beyond what vendors provide today. The architectural properties of retrieval-augmented generation—combining retrieved data and user input in the same reasoning chain—create inherent vulnerability classes that can't be fully eliminated by patching individual bugs. Organizations can reduce risk through the five-point framework, restricted access policies, and detailed logging, but they can't eliminate it. This means AI systems should be considered high-risk components of security architecture that require dedicated monitoring, testing, and governance rather than systems that can be trusted based on configuration alone.

Should organizations disable Copilot entirely if they handle sensitive data?

That's a business decision, not a security requirement. If the productivity benefits justify the risk, organizations can deploy Copilot with appropriate controls: restricting it to non-sensitive data, disabling external email context, enabling Restricted Content Discovery for sensitive sites, and implementing the five-point audit framework. However, organizations that can't tolerate any exposure of sensitive data to AI systems should restrict Copilot to non-regulated, non-sensitive use cases only, or disable it entirely until vendors provide stronger trust boundaries and auditability.

Recommended Reading

For security teams looking to build AI-specific governance programs, the core competencies required are: understanding retrieval-augmented generation architectures, testing AI decision logic, interpreting AI vendor disclosures, and building custom telemetry for data access patterns. These differ significantly from traditional application security, which focuses on input validation, SQL injection, authentication, and infrastructure-level controls.

Key Takeaways

- CW1226324 exposed a code-path error in Copilot's DLP enforcement that operated silently for 29 days without triggering any alerts from EDR, WAF, or SIEM tools

- EchoLeak demonstrated that AI retrieval pipelines are architecturally vulnerable to prompt injection attacks because they process trusted and untrusted data in the same reasoning chain

- Traditional security tools are blind to AI trust violations because these occur in the application logic layer, not at infrastructure boundaries where EDR, WAF, and SIEM have visibility

- Compliance audits are incomplete for AI systems because they verify configuration without testing whether AI systems actually honor those configurations at runtime

- A five-point framework (direct DLP testing, external content restriction, retrospective auditing, Restricted Content Discovery, and custom logging) provides practical immediate mitigations

- Organizations must shift from a trust-based security model (assuming configuration implies behavior) to a verification-based model (testing that AI systems actually honor their restrictions)

Related Articles

- AI Recommendation Poisoning: The Hidden Attack Reshaping AI Safety [2025]

- AI Prompt Injection Attacks: The Security Crisis of Autonomous Agents [2025]

- Moltbot: The Open Source AI Assistant Taking Over—And Why It's Dangerous [2025]

- OpenClaw AI Ban: Why Tech Giants Fear This Agentic Tool [2025]

- Why AI Models Can't Understand Security (And Why That Matters) [2025]

- Claude Desktop Extension Security Flaw: Zero-Click Prompt Injection Risk [2025]

![Microsoft Copilot Bypassed DLP: Why Enterprise Security Failed [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-copilot-bypassed-dlp-why-enterprise-security-faile/image-1-1771621933463.jpg)