Microsoft's Rust Push Explained: Is C/C++ Really Going Away? [2025]

If you were scrolling LinkedIn a few months back and saw a Microsoft engineer casually mention eliminating every line of C and C++ by 2030, you probably did a double take. The internet certainly did. Think pieces multiplied. Reddit threads ignited. Developers everywhere started wondering if their expertise in C++ was about to become obsolete.

But here's the thing: the story everyone was reacting to wasn't actually the whole story.

A Microsoft engineer named Galen Hunt posted about his team's ambitious goal to translate Microsoft's massive C and C++ codebase into Rust, positioning it as a way to eliminate technical debt at scale. The post went viral, and suddenly it looked like Microsoft was ready to sunset two of the most foundational languages in computing. Except that's not what's happening. Not even close.

Hunt clarified shortly after that this is a research project, not a corporate mandate. Microsoft isn't declaring war on C and C++. The company is exploring whether AI-powered tools could help systematically refactor legacy code into memory-safe alternatives. It's a moonshot experiment, not a strategic death sentence for languages that power everything from operating systems to game engines.

But that clarification raises way more interesting questions than the original headline ever did. What's really going on here? Why is Microsoft investing in this? What would it actually take to migrate billions of lines of legacy code? And what does this mean for the future of systems programming?

Let's dig into what's actually happening, why it matters, and what you need to know if you're writing code in 2025.

TL; DR

- Microsoft's announcement: A researcher's LinkedIn post about eliminating C/C++ by 2030 went viral, but was clarified as a research project, not official corporate strategy

- What it actually is: An AI-powered infrastructure project to explore translating legacy C/C++ systems into Rust at scale using AI agents and code processing algorithms

- The real context: Microsoft is officially pushing Rust as a "1st class language" and has invested $10 million in Rust ecosystem development

- Why this matters: Memory safety bugs in C/C++ cost organizations billions annually; Rust eliminates entire classes of vulnerabilities by design

- The reality check: Complete migration is decades away for any large organization; the project focuses on technical debt elimination, not forced rewrites

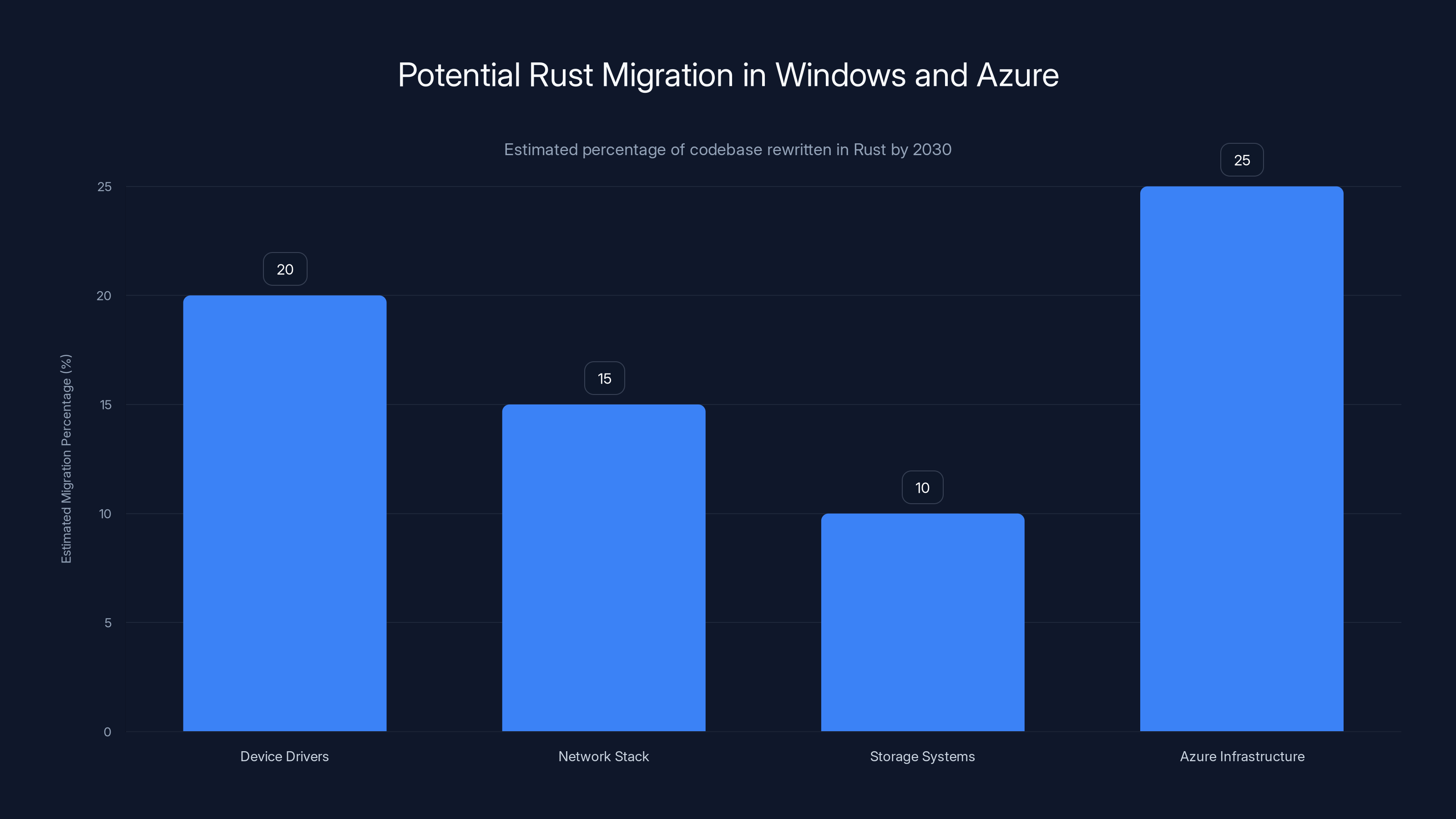

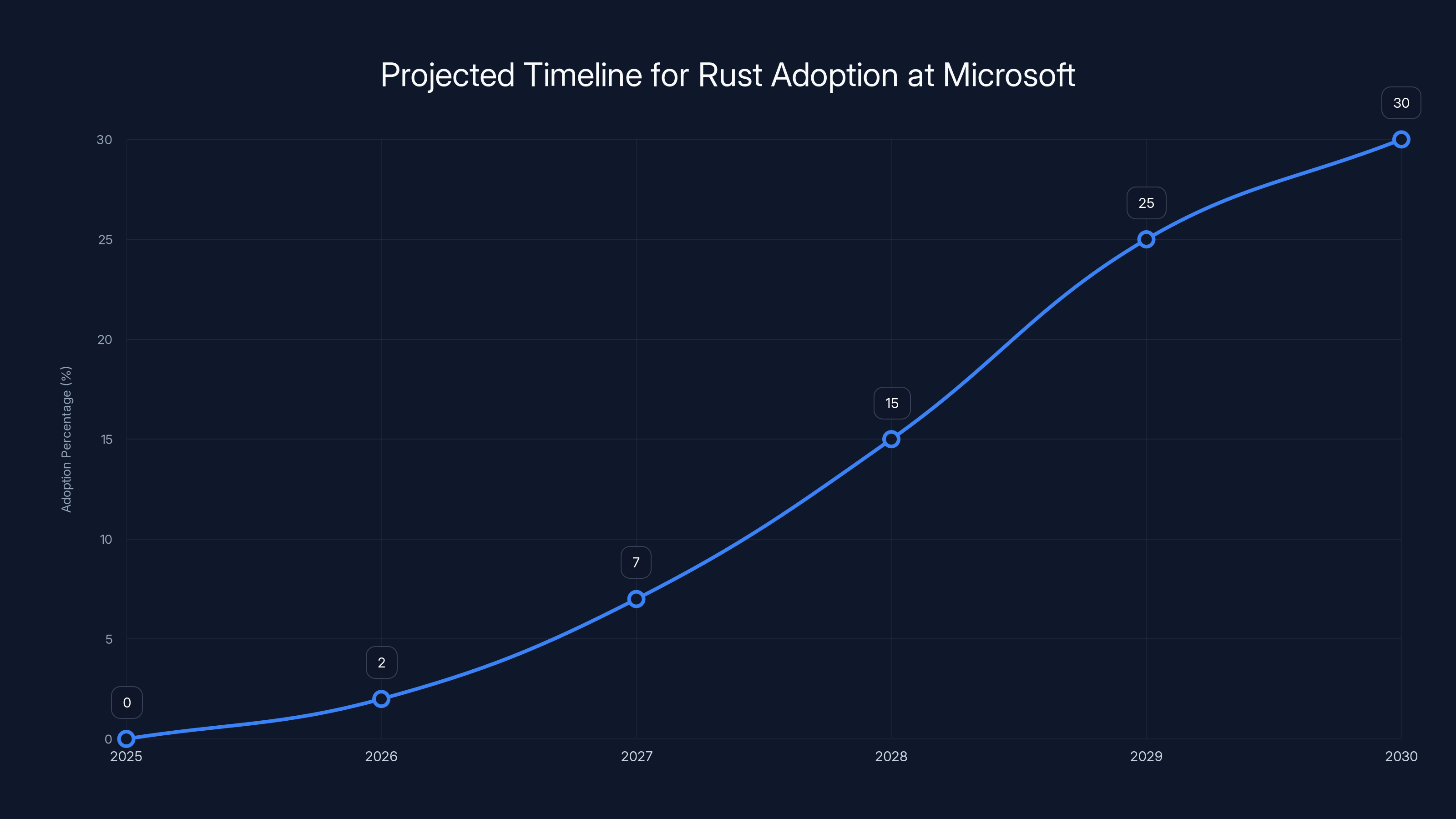

By 2030, it's estimated that 15-25% of certain Windows and Azure subsystems could be rewritten in Rust, improving security and efficiency. Estimated data.

What Actually Happened: Separating Viral Post From Reality

In his LinkedIn post, Galen Hunt, a principal engineer at Microsoft, announced that his team was hiring for a role to "help us evolve and augment our infrastructure to enable translating Microsoft's largest C and C++ systems to Rust." He explicitly stated the goal: "eliminate every line of C and C++ from Microsoft by 2030."

The internet read that headline and exploded.

Developers who've spent two decades mastering C++ syntax worried their skills were about to become museum pieces. C++ purists argued this was technically infeasible. AI skeptics claimed this was typical tech hype. DevOps teams started sweating about what this meant for their systems.

But Hunt's follow-up post contained a critical clarification that most people missed: "Just to clarify... Windows is NOT being rewritten in Rust with AI." He emphasized that this is a research project from one team, exploring capabilities that don't yet exist at the scale required to actually do what he's describing.

This distinction matters enormously. There's a difference between "we're researching whether this is theoretically possible" and "we're committing to this as a company directive." Microsoft has made the first commitment, not the second.

What Hunt's team is actually working on is infrastructure for AI-powered code transformation. They've built what they call "powerful code processing infrastructure" that allows AI agents to make code modifications at scale, guided by algorithms. The team's north star metric is audacious: "1 engineer, 1 month, 1 million lines of code." Meaning, eventually, they want tooling where a single engineer could modify a million lines of legacy code in 30 days.

That's not about eliminating C++ from Windows. That's about having tools sophisticated enough to systematically refactor code at a scale that makes large migrations mathematically feasible.

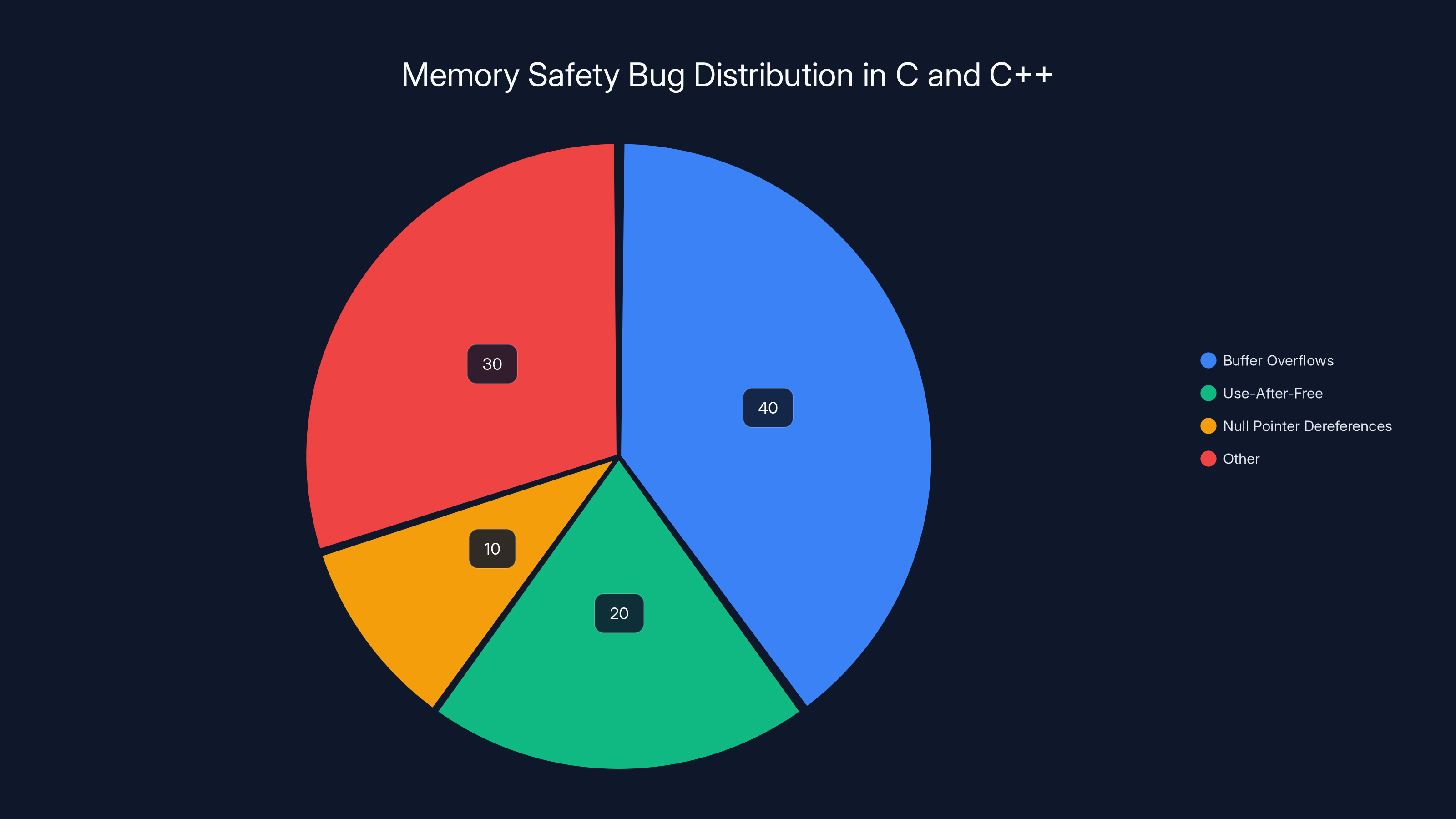

Estimated data shows buffer overflows account for the largest share of memory safety bugs in C/C++ code, highlighting the importance of Rust's compile-time safety features.

The Actual Project: AI-Powered Code Transformation at Scale

To understand what Hunt's team is really building, you need to understand the problem they're trying to solve: technical debt.

Technical debt is the accumulated cost of maintaining legacy code. Every system that's been around for 10+ years accumulates it. Code that was optimized for 2005's hardware makes weird decisions on 2025's processors. Functions that made sense when your team was five people become maintenance nightmares when you're managing them across a thousand engineers. Dependencies that were state-of-the-art become security liabilities.

The traditional way to handle technical debt is expensive and slow. You identify problematic code, form a team, spend months or years rewriting it, carefully test the changes, and pray nothing breaks in production. At Microsoft's scale, this approach is paralyzing. You could assign 100 engineers to modernization projects and barely make a dent.

Hunt's team is building infrastructure that flips this problem. Instead of humans refactoring code, AI agents refactor code under human guidance. The AI doesn't just translate syntax; it's guided by algorithms that understand the code's structure, purpose, and dependencies.

Here's how their architecture works:

First, they create a "scalable graph over source code." This means converting the codebase into a structured representation where relationships between functions, modules, and systems are explicitly mapped. A typical C++ codebase has tens of thousands of these relationships. The algorithm creates a graph where nodes represent code components and edges represent dependencies.

Second, AI agents operate on this graph. An AI agent might be tasked with "identify all uses of deprecated threading model X and refactor them to modern threading model Y." The agent doesn't just do a text search and replace (which would break things). It understands the code semantically, identifies what each deprecated call does, understands why it was written that way, and makes changes that preserve functionality while using modern APIs.

Third, the system validates changes algorithmically. It runs tests, checks type safety, verifies that performance characteristics haven't degraded, and flags anything suspicious for human review. Humans remain in the loop, but they're reviewing algorithmic decisions instead of making every decision manually.

Hunt notes that "the core of this infrastructure is already operating at scale on problems such as code understanding." This isn't theoretical. They've already built the foundational layers and proven they work.

The big insight here is that the Rust migration is almost a side effect. The real project is building transformation infrastructure that can handle C++ to Rust translation because that's a particularly hard problem. If you can translate C++ to Rust at scale, you can solve almost any code modernization problem.

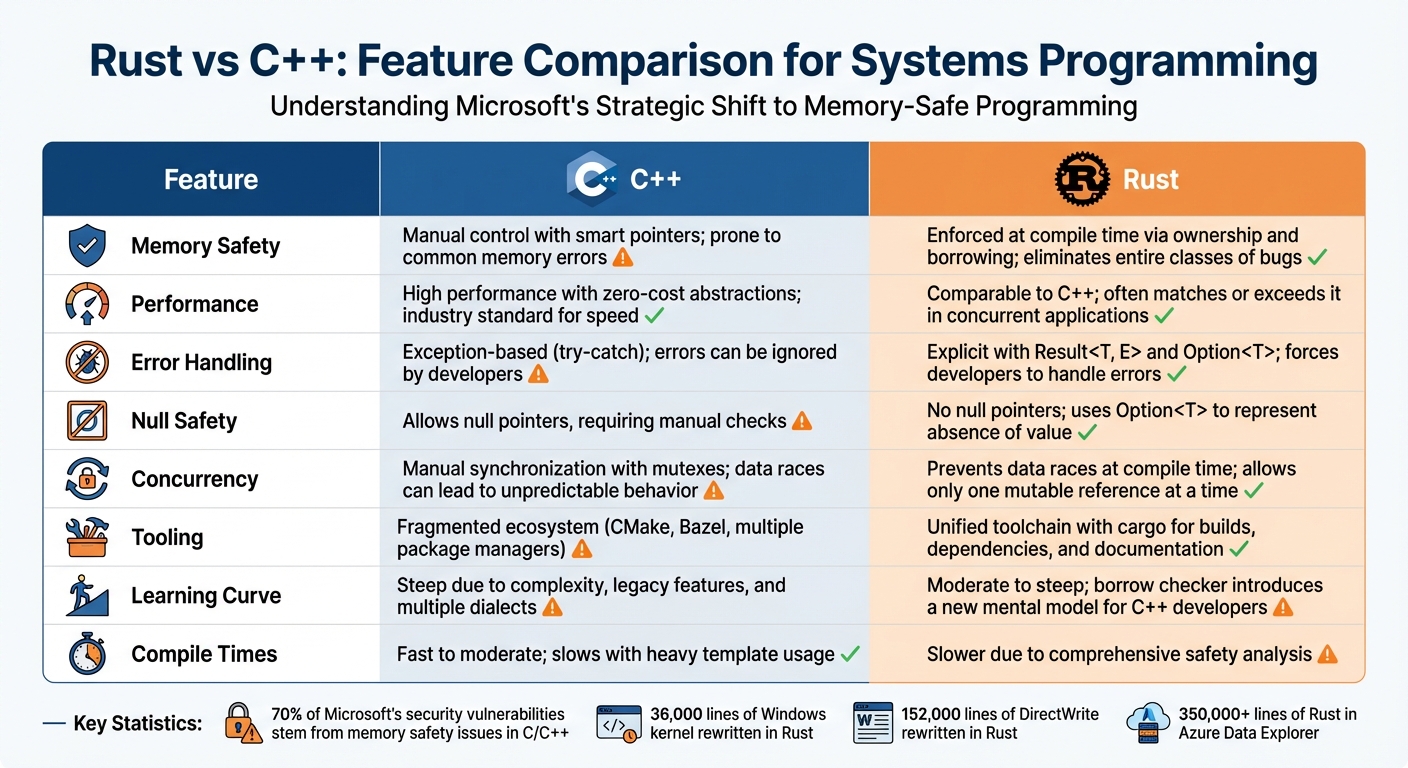

Why Microsoft Is Serious About Rust: The Memory Safety Argument

Now, the obvious question: why pick Rust as the target? Why not just modernize C++ itself?

The answer comes down to memory safety.

Memory safety bugs are a specific class of vulnerability where a program accesses memory incorrectly. This includes buffer overflows, use-after-free errors, integer overflows, and null pointer dereferences. In C and C++, these bugs are possible because the language allows direct memory manipulation without compiler-enforced safety checks.

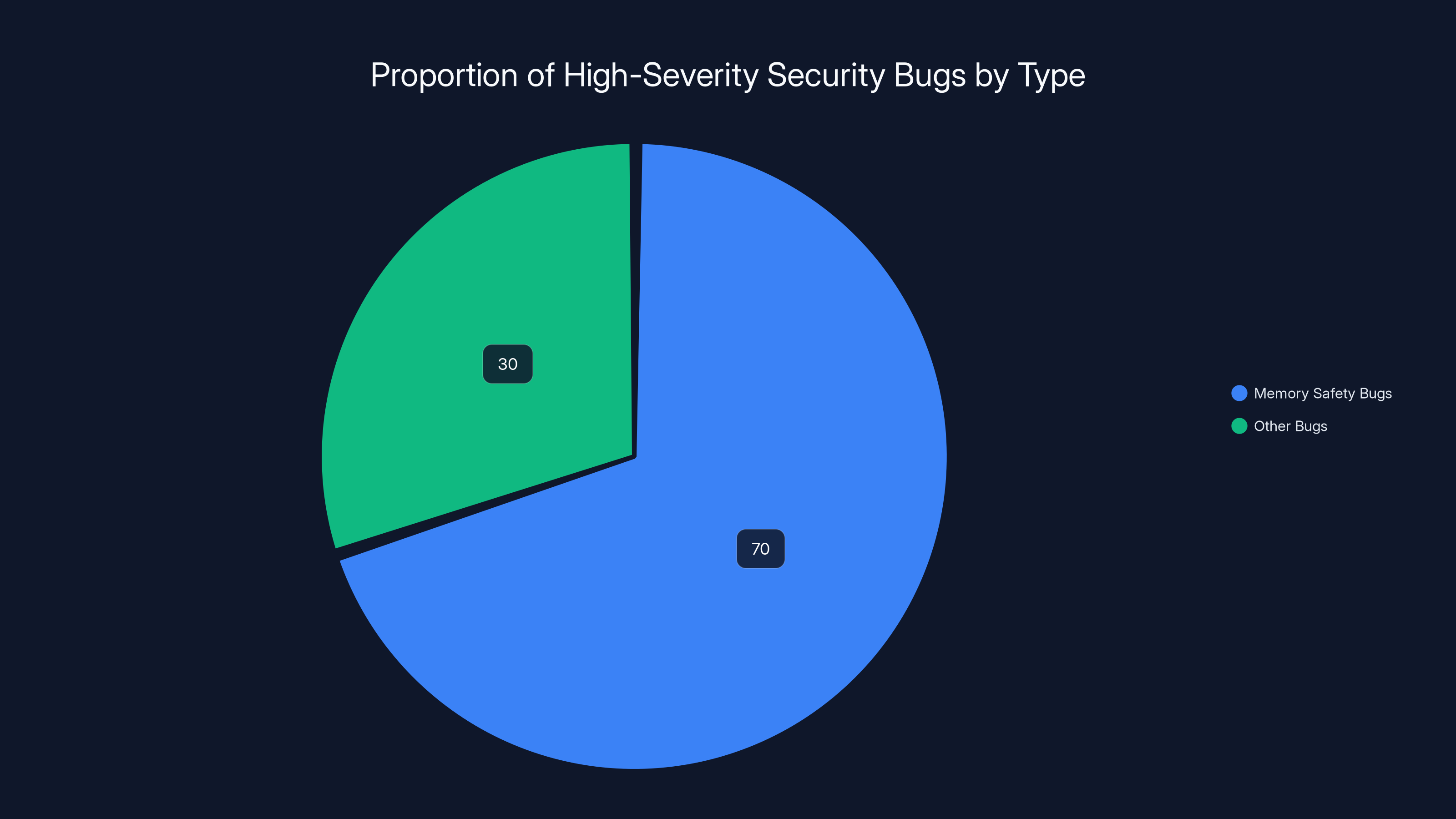

Google's Android security team published research showing that about 70% of Android's high-severity security bugs are memory safety issues. Similar statistics hold across most large C and C++ codebases. These bugs are simultaneously expensive to find, trivial for attackers to exploit, and nearly impossible to eliminate completely.

Rust eliminates entire categories of these bugs at compile time. You literally cannot write certain types of buggy code in Rust. The compiler rejects programs that could have memory safety issues. This isn't a minor benefit—it's transformative for security.

Microsoft has recognized this. The company spent $10 million pushing Rust as a "1st class language" for engineering systems. This isn't charity. It's an investment in addressing what the company clearly views as a critical infrastructure problem.

Google's commitment reinforces this. Google announced that memory safety bugs in C and C++ are "the most-difficult-to-address source of incorrectness" in their systems. The company made Rust a first-class language alongside Java and Kotlin in the Android Open Source Project. This means developers can write Android system components in Rust, and the tooling treats it as a peer to Java.

When Microsoft and Google both independently decide that memory safety is important enough to invest billions in Rust, you're looking at a real shift in the industry's priorities.

But here's the critical point: this isn't about C++ being bad. C++ is phenomenal for many use cases. It's about recognizing that for certain classes of problems—particularly systems-level code where memory bugs have outsized consequences—memory-safe languages have measurable advantages.

Research indicates that 70% of high-severity security bugs in Android are due to memory safety issues. This highlights the critical need for languages like Rust that inherently prevent such vulnerabilities.

The Reality Check: How Long Would This Actually Take?

Here's where the viral narrative breaks down completely.

Microsoft said the goal is 2030. That's five years away. Windows, Azure, Office, Xbox, and every other major Microsoft system collectively contain hundreds of millions of lines of code. Much of it is in C or C++.

Even with perfect AI-powered refactoring tools, translating all of that code is mathematically improbable by 2030. And that assumes:

- The tools work as well as Hunt hopes (they don't yet)

- No new code is written in C/C++ between now and 2030 (impossible)

- Every team at Microsoft deprioritizes feature work to refactor (won't happen)

- Zero integration issues emerge during the largest codebase transformation in history (unlikely)

What's actually possible by 2030 is something more modest: proof of concept demonstrations on specific subsystems, significant refactoring of certain components where the ROI is clear, and the tools maturing to the point where major projects can consider them.

Think of it like the iPhone launch announcement in 2007. Steve Jobs showed a vision of what was possible. The actual product shipped months later with compromises. The vision drove the direction, but reality required adjustments.

Hunt's "2030" is a north star, not a schedule. It's a way of saying "this is important enough that we're committing significant resources to make progress." In tech, that often means 5-10 year timelines to see major results.

Rust: The Language Behind The Initiative

Understanding Rust is essential to understanding why Microsoft thinks this migration is worth the effort.

Rust is a systems programming language that runs at C/C++ speeds while providing memory safety guarantees. The language achieves this through a concept called "ownership." Every value in Rust has a single owner. When you pass a value to a function, ownership transfers. When the owner goes out of scope, the value is cleaned up. The compiler enforces these rules.

This sounds abstract, but it has concrete implications. You cannot accidentally use memory after freeing it. You cannot accidentally write past the end of an array. You cannot accidentally share data across threads in ways that cause race conditions. The compiler prevents all of these before your code runs.

For developers coming from C++, Rust is famously strict. The compiler rejects programs that might be unsafe. This creates a learning curve—developers often spend their first weeks fighting the compiler. But the payoff is substantial: code that compiles is significantly more likely to be correct and secure.

Rust has been growing rapidly. The language ranked in the top 20 most-used programming languages by 2024, climbing from obscurity five years earlier. It's the only language that's appeared in every version of the Linux kernel since 2021. Major projects like the Kubernetes container runtime, parts of Firefox, and the Tokio async runtime are all implemented in Rust.

From Microsoft's perspective, Rust offers something C++ cannot: a path to memory safety without runtime overhead. C++ has memory safety libraries, but they add runtime checks and complexity. Rust achieves memory safety through compile-time guarantees.

The language also has network effects. As more infrastructure is built in Rust, more developers learn it. As more developers know it, more projects adopt it. Microsoft's investment accelerates this flywheel.

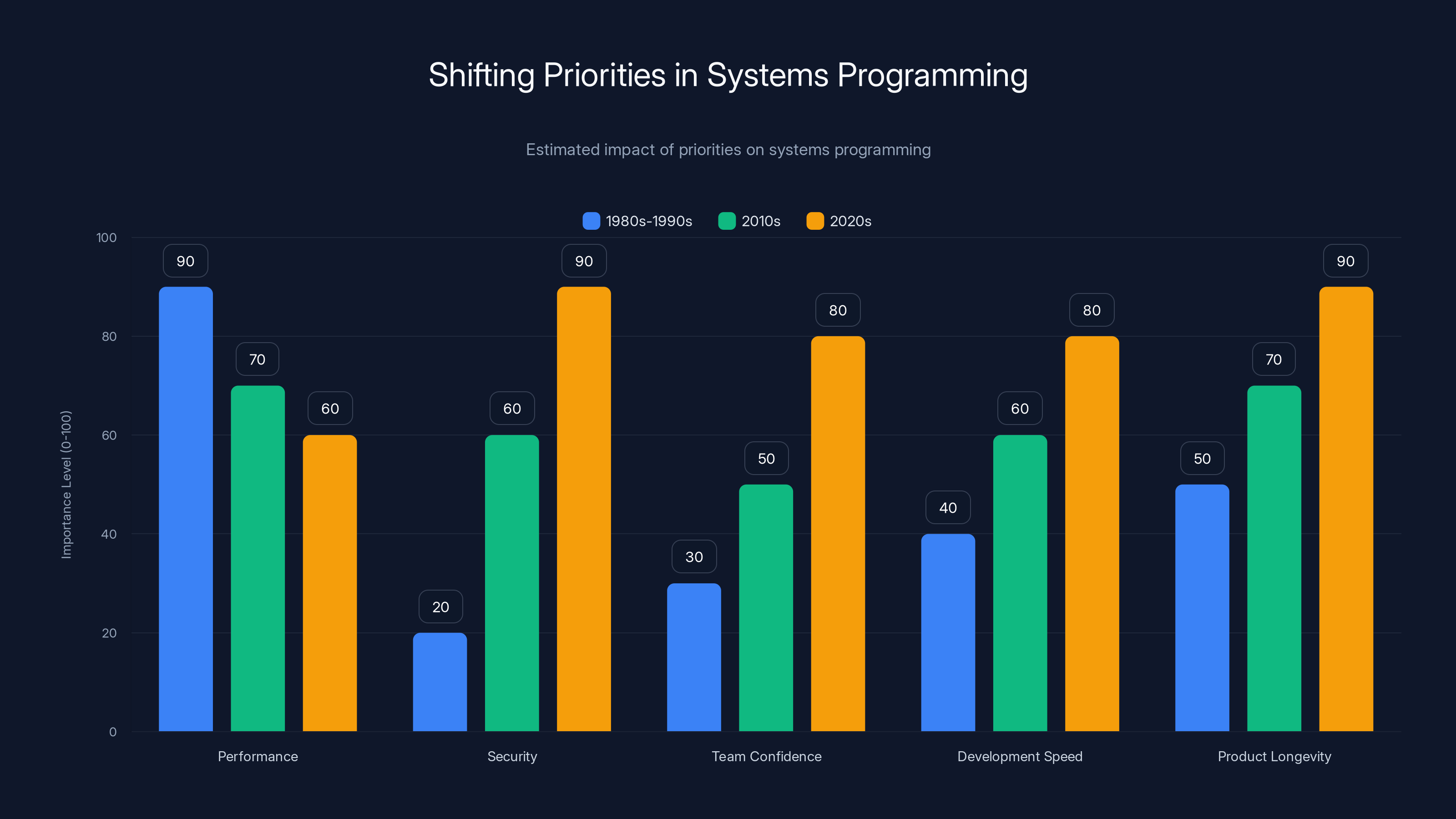

Estimated data shows a shift from performance to security and other factors in systems programming over the decades.

The C and C++ Ecosystem Problem: Why Elimination Is Hard

For all the hype around Rust, completely eliminating C and C++ from any large organization remains nearly impossible. Here's why:

First, there's ecosystem lock-in. Microsoft Windows runs on billions of devices. The entire platform is built on APIs, ABIs (application binary interfaces), and architectural decisions made when C and C++ were the only reasonable choices for systems programming. Changing this would require rewriting not just Microsoft's code, but potentially breaking compatibility with countless applications.

Second, there's hardware integration. Some of Windows' most performance-critical code interacts directly with hardware—bootloaders, device drivers, low-level scheduler implementations. These often require the kind of fine-grained control that only C and C++ provide. Rust can do this too, but the migration is non-trivial.

Third, there's organizational inertia. Microsoft has tens of thousands of engineers. A significant portion of them specialize in C++. Retraining an entire workforce is expensive and takes time. You don't just announce "everyone learns Rust now." You gradually establish Rust as an option, demonstrate its benefits, and let adoption grow organically.

Fourth, there's the question of new code. Even if Microsoft successfully migrated existing systems, new code written between now and 2030 would need to be in Rust. That requires Rust tooling to be mature enough for every use case Windows currently supports in C++. As of 2025, that's not quite there yet. Rust's async story is solid but still evolving. Some embedded scenarios remain easier in C.

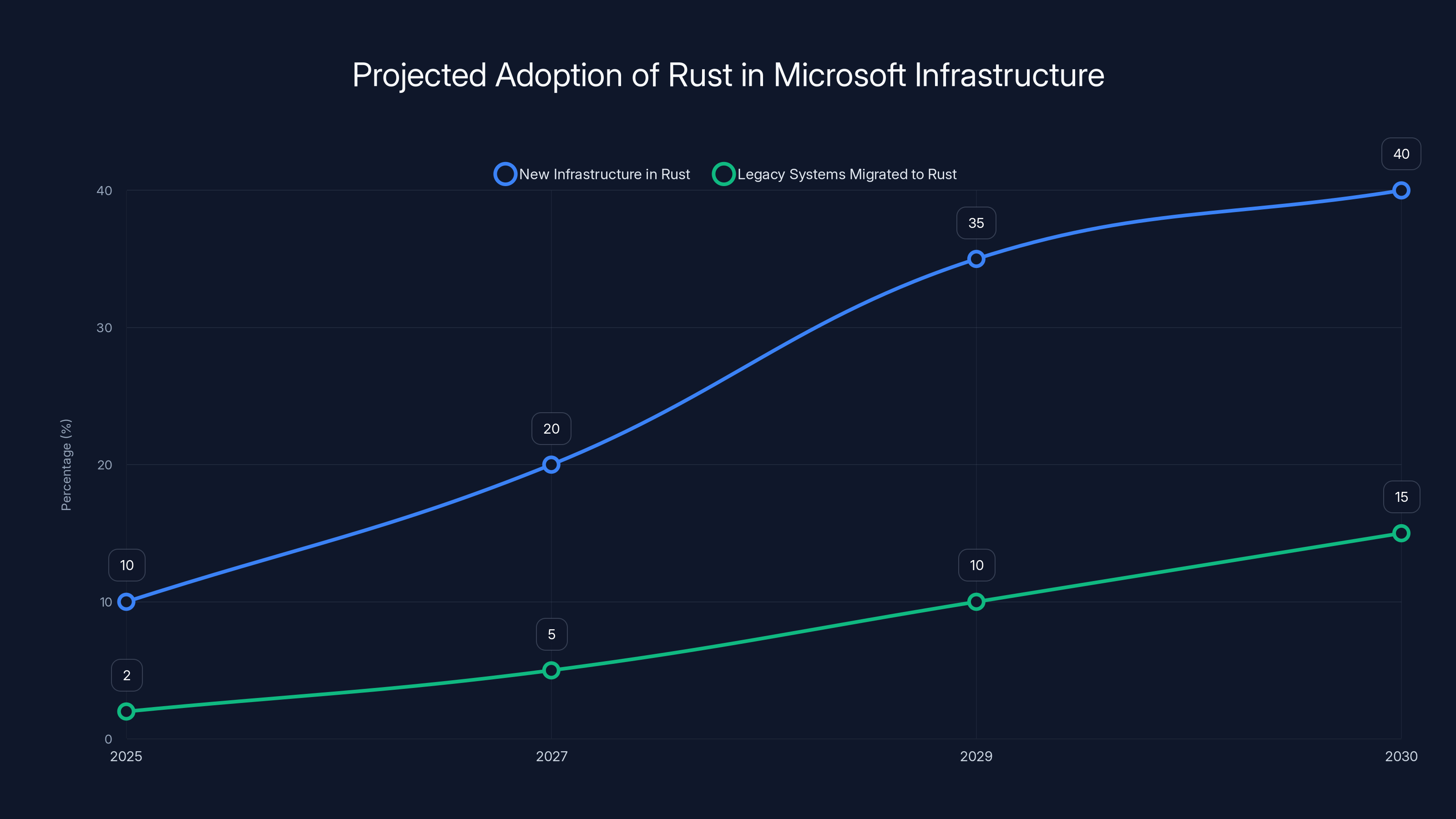

What's actually realistic is a gradual shift. New projects use Rust. Modernization initiatives prioritize high-impact components. Legacy code that works well stays put. Over a decade, the ratio shifts. By 2030, maybe 30-40% of new Microsoft infrastructure is Rust. Maybe 10-15% of legacy systems have been migrated. That's transformational progress without being unrealistic.

How AI-Powered Refactoring Actually Works

Let's get specific about what the transformation infrastructure does.

Hunt mentions that the system creates "a scalable graph over source code at scale" and uses "AI agents, guided by algorithms, to make code modifications at scale." This sounds abstract, but there's concrete technology behind it.

Modern AI language models like GPT-4 are trained on vast amounts of code. They understand programming concepts, design patterns, and how different pieces of code relate to each other. When you give such a model a C++ function and ask it to translate to Rust, it doesn't just do keyword replacement. It understands what the function does, identifies equivalent Rust patterns, and generates idiomatic Rust code.

But raw AI translation isn't reliable. That's where "guided by algorithms" comes in. The system combines AI generation with algorithmic validation. Here's a simplified workflow:

-

Code Analysis Phase: The system parses the C++ code and builds a semantic representation. It identifies types, functions, dependencies, and control flow.

-

AI Translation Phase: An AI model generates Rust equivalents. For common patterns (iterating over vectors, managing memory, thread synchronization), it has learned patterns that work well.

-

Validation Phase: Algorithms check the generated Rust code. Does it compile? Does it pass existing tests? Does the performance profile match the original? Are there any unsafe blocks that could be eliminated?

-

Human Review Phase: Flagged issues go to a human engineer. For straightforward cases ("the generated code is correct but not idiomatic"), the system suggests fixes. For complex cases, the engineer reviews and potentially rewrites.

-

Integration Phase: The refactored code is integrated into the codebase, tested in real environments, and monitored for issues.

The key insight is that this process scales. If you need to refactor one function, you do it manually. If you need to refactor a thousand functions following the same pattern, automation provides massive value.

Microsoft's claim that this infrastructure is already "operating at scale on problems such as code understanding" suggests they've proven out at least the early phases. The company might not have achieved "1 engineer, 1 month, 1 million lines of code" yet, but they're probably at "10 engineers, 1 month, 1 million lines of code" or similar.

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in Rust adoption at Microsoft, reaching up to 30% by 2030. This reflects the typical pace of change in large organizations.

Industry Parallels: Other Companies Moving Toward Memory Safety

Microsoft isn't alone in this push. Industry-wide, there's a shift toward memory-safe languages.

Google's Android team explicitly stated that memory safety is their top security priority. The company invested in Rust support, made it a first-class language in the AOSP, and hired Rust specialists. Google also started a Rust-in-Linux project to get Rust into the Linux kernel's core components. This isn't a Microsoft-specific trend; it's an industry-wide recognition that memory safety matters.

Amazon pushed Rust for AWS Lambda and container infrastructure. The company has thousands of engineers building on AWS, and the company recognizes that Rust's safety properties reduce the surface area for security bugs.

Meta (Facebook) invested in Rust for systems infrastructure and contributed significantly to the Rust async ecosystem. The company is rebuilding parts of its infrastructure in Rust.

Even the United States government has taken notice. The National Security Agency recommended using memory-safe languages, explicitly naming Rust, for mission-critical systems. CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency) published guidance suggesting that organizations should prioritize memory-safe languages.

This convergence is significant. When competitors independently decide something's important, you're looking at a real shift, not hype.

What This Means for C and C++ Developers

If you write C or C++, the natural question is: does this threaten my career?

Short answer: no.

Long answer: the situation is more nuanced.

C and C++ aren't going anywhere soon. The Linux kernel is written in C. Databases use C. Game engines use C++. Embedded systems often require C. Financial trading systems use C++. These aren't going to disappear in five years or ten years or even fifty years.

What is likely to change is the trajectory of new projects. Five years ago, if you wanted to write systems-level code, C++ was probably your choice. Ten years from now, if you want to write systems-level code, Rust might be your first choice for new projects.

This creates an opportunity. Developers who understand both C++ and Rust are incredibly valuable. You have deep knowledge of systems programming concepts. Rust is just a new way to express those concepts with additional safety guarantees.

The smart move for C++ developers in 2025 is:

-

Stay current with C++. C++23 and C++26 are adding features that make the language safer. Learn them.

-

Learn Rust as a supplement. You don't need to abandon C++. Understanding Rust helps you understand memory safety concepts more deeply and makes you more valuable.

-

Understand why memory safety matters. Read the Android research. Understand the NSA's position. This isn't about language preferences; it's about security.

-

Position yourself for transitions. If your company decides to migrate systems to Rust, developers who understand both languages are invaluable for the transition.

Historically, the industry has a poor track record of completely replacing old languages. COBOL was supposed to be retired decades ago. It still runs most banking systems. Assembly was supposed to become obsolete. It's still used in performance-critical code. C was supposed to be replaced by C++. Instead, C and C++ coexist.

The likely future is similar: C and C++ remain for specific use cases where their properties are valuable, while Rust captures new projects where memory safety is a priority.

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in Rust adoption, with 30-40% of new infrastructure and 10-15% of legacy systems using Rust by 2030.

The Technical Challenges: Why This Is Genuinely Hard

Hunt's team faces genuine technical challenges that make this research necessary.

First, there's the semantic gap. C and C++ are imperative languages where you explicitly say how to do things. Rust is also imperative but enforces stricter rules. Some C++ patterns don't map cleanly to Rust. For example, C++ allows complex pointer aliasing (multiple pointers to the same data) in ways that Rust's borrow checker would reject. The transformation needs to recognize when code uses aliasing and refactor it to avoid it.

Second, there's the performance requirement. If you migrate C++ code to Rust and it's 30% slower, you haven't succeeded. The transformed code needs to maintain performance characteristics. This means the transformation can't just be syntactic; it needs to understand performance implications and preserve them.

Third, there's the compatibility requirement. Windows applications depend on APIs that are defined in C/C++. Those APIs define data structures, function signatures, calling conventions. If you change them, you break compatibility. The migration needs to either preserve these interfaces or provide adapters, which adds complexity.

Fourth, there's the testing challenge. How do you prove that refactored code is correct? For straightforward refactors, existing tests pass and you're done. For complex code where the refactoring changed the structure significantly, you need additional verification. The transformation system needs to generate additional test cases or use formal verification techniques.

Fifth, there's the human expertise problem. C++ is a complex language with decades of accumulated patterns and anti-patterns. Rust is younger and still evolving. Developers need expertise in both to make good refactoring decisions. You can't just hire AI researchers; you need engineers who understand both languages deeply.

Hunt's team is essentially building a tool that handles all five of these challenges simultaneously. That's why it's a research project.

The AI Component: Not Magic, But Useful

The AI aspect of Hunt's project deserves special attention because there's often hype around AI solving hard problems.

Here's the reality: AI language models are excellent at certain tasks and mediocre at others. They're excellent at learning patterns from training data. They're mediocre at formal verification or proving correctness.

When it comes to code translation, AI models are useful because:

-

Pattern Recognition: C++ to Rust has patterns. Many functions follow standard templates. AI learns these patterns and applies them.

-

Context Awareness: Modern language models understand context across large code spans. This helps them recognize what a function is doing, not just what its syntax is.

-

Idiomatic Translation: Raw translation could produce working code that's not idiomatic Rust. AI can be trained to produce code that feels natural to the target language.

But AI models also have limitations:

-

Hallucination: Sometimes they confidently generate incorrect code. They might create function calls that don't exist or use APIs incorrectly.

-

Lack of Formal Proof: They can't prove correctness. A generated function might compile and pass tests but have subtle bugs.

-

Limited Reasoning: They struggle with problems that require deep logical reasoning across large systems.

This is why Hunt emphasizes that AI is "guided by algorithms." Algorithms handle the hard stuff (formal verification, semantic checking, proving correctness). AI handles the pattern-matching stuff (translating common structures, suggesting idiomatic code). Together, they create a system more powerful than either alone.

The hype around AI often ignores this partnership. The reality is that many hard problems are solved with hybrid approaches: AI for generation, algorithms for validation, humans for complex reasoning.

What Happens to Windows? What Happens to Azure?

The question everyone wants answered: will Windows be rewritten in Rust?

Hunt explicitly clarified: no. Not by 2030. Maybe not ever, in its entirety.

What's more likely is a pragmatic middle ground. Specific subsystems get rewritten. Critical components get rewritten. New components are written in Rust from the start. Over time, the ratio shifts.

Consider what subsystems might be good candidates for Rust migration:

-

Device Drivers: These are often the source of memory safety bugs because they interact directly with hardware. Rust would eliminate many of these bugs. Migrating existing drivers gradually makes sense.

-

Network Stack: Windows' network implementation is complex and regularly audited for security. Rust could provide better security guarantees and reduce maintenance burden.

-

Storage Systems: Filesystems and storage subsystems are memory-intensive. Rust's memory safety would reduce bugs.

-

Azure Container Infrastructure: Microsoft's cloud platform could move faster toward Rust than the legacy Windows codebase.

What's unlikely to be rewritten:

-

Core Scheduler: The Windows scheduler is highly optimized, extensively tested, and has specific performance requirements. Rewriting it is risky for minimal benefit.

-

Graphics Stack: Windows' graphics implementation (DirectX, GPU integration) is complex and performance-critical. The effort to migrate wouldn't justify the benefit.

-

Backwards Compatibility Layers: Windows maintains compatibility with decades-old code. Rewriting compatibility layers in Rust doesn't reduce bugs if you're still supporting buggy APIs.

Realistic scenario for 2030: maybe 15-20% of Windows codebase is in Rust or has been refactored. The percentage is higher for new Azure infrastructure. The benefits are measurable in reduced security bugs and faster iteration on new features.

The Broader Implications: Shifting Priorities in Systems Programming

What's interesting about this shift isn't just that one company is investing in Rust. It's what the shift reveals about how the industry is prioritizing.

For decades, systems programming was almost exclusively about performance. Can you shave microseconds off the response time? Can you reduce memory usage by 5%? Developers who could squeeze performance out of C++ were highly valued.

Memory safety is shifting this calculus. Yes, performance matters. But security matters more. A 5% performance penalty that eliminates 70% of security bugs is usually a good trade.

This represents a maturation of the industry. In the 1980s and 1990s, performance was the limiting factor. In the 2010s, as hardware got faster, security became the limiting factor. In the 2020s, security and correctness are the primary concerns, with performance as a constraint rather than the goal.

Rust aligns with this new reality. The language doesn't give you magical performance wins, but it gives you safety wins. You can still optimize for performance, but you do so from a foundation of safety.

This has implications beyond just programming languages. It affects:

-

What skills are valued: Security expertise becomes more valuable than performance optimization expertise.

-

How teams are organized: You can have smaller, more confident teams if memory safety is guaranteed by the language.

-

How development timelines work: Memory safety bugs are expensive to debug. Catching them at compile time saves months of debugging.

-

How long products remain supported: Rust code requires less ongoing security patching than C++ code.

Microsoft's investment in this shift isn't just about technical choices. It's about acknowledging that the industry's priorities have changed.

Timeline Realities: When This Actually Happens

Hunt's team is targeting 2030. Let's think about what realistic milestones might look like.

2025-2026: Proof of concept demonstrations on smaller systems. Validate that the AI infrastructure can handle real code. Solve specific hard problems (complex memory patterns, performance preservation). Get internal buy-in.

2026-2027: Pilot migrations on selected subsystems. Maybe a non-critical component gets fully migrated. Measure the benefits and costs. Refine processes. Start deploying Rust in new systems infrastructure.

2027-2028: Expanded migration to multiple subsystems. More teams adopt Rust for new projects. Tooling matures. Training programs scale up. Maybe 5-10% of Microsoft infrastructure is in Rust or has been refactored.

2028-2029: Large-scale adoption of Rust for new systems. Selective migration of high-impact legacy systems. Security benefits become measurable. Performance is proven equivalent or better.

2030+: Ongoing migration becomes routine. New Microsoft infrastructure defaults to Rust. Legacy C/C++ is gradually reduced. Maybe 20-30% of systems have migrated.

This is speculative, but it's grounded in how large organizations actually work. Change happens gradually. Proofs of concept take a year. Pilots take a year. Full rollout takes years. Momentum compounds over time.

If Hunt's team hits all their targets, 2030 might see a genuinely transformed Microsoft infrastructure. If they hit 60% of targets, it's still transformational, just slower. If they hit 30% of targets, they've still created valuable tools and proven the approach works.

Risks and Unknowns: What Could Go Wrong

Hunt's team is embarking on one of the largest code refactoring projects in history. There are meaningful risks:

Technical Risks:

- The AI infrastructure doesn't scale as well as hoped

- Generated code has subtle bugs that testing doesn't catch

- Performance degradation is larger than expected

- Rust tooling matures slower than expected

Organizational Risks:

- Engineers resist learning Rust and slow adoption

- The project loses executive support and funding

- Other priorities (new features, other initiatives) take precedence

- Integration with legacy code is messier than expected

Market Risks:

- A new memory-safe language emerges that's better than Rust

- The industry converges on a different solution

- Customers don't care about the internal language of Windows

Competitive Risks:

- Other companies solve the same problem faster

- Open-source tools provide similar capabilities

- The benefits don't materialize and the effort is wasted

These aren't reasons to dismiss the project. They're normal risks that any ambitious research project faces. Hunt's team is probably already planning for them.

What matters is that Microsoft is willing to take these risks because the potential benefit is significant enough to justify it. From an organizational perspective, that's healthy. It means the company is investing in future infrastructure, not just maintaining the status quo.

The Developer Experience: Why This Matters Beyond Microsoft

Ultimately, why should developers outside Microsoft care about this project?

Because the tools and infrastructure being built will likely become open source or influence the broader ecosystem.

Hunt's team is building tools for code understanding, semantic analysis, and transformation at scale. These tools would be valuable for any large codebase modernization project. If they're released or open-sourced, other companies would benefit.

Microsoft has a history of eventually open-sourcing or releasing significant infrastructure projects. Visual Studio Code is open source. .NET is open source. TypeScript is open source. The company has learned that open-source investments can drive ecosystem adoption of related products.

It's plausible that within 5-10 years, there's an open-source toolkit for large-scale code transformation powered by AI and guided by algorithms. Companies could use this toolkit to migrate their own legacy codebases. This would be transformational for the industry.

Even if Microsoft never releases these tools, the existence of successful examples drives other companies to build similar systems. Seeing Microsoft prove it's possible makes it more likely that Google, Amazon, and others invest in their own tools.

So this isn't just about Windows or Azure. It's about establishing proof that large-scale code modernization is feasible, which gives other organizations permission and motivation to try it themselves.

FAQ

What exactly did the Microsoft engineer announce about C and C++?

Galen Hunt, a principal engineer at Microsoft, posted on LinkedIn about his team's goal to translate Microsoft's large C and C++ systems into Rust by 2030. The post went viral, but Hunt later clarified that this is a research project exploring whether AI-powered infrastructure can handle code transformation at scale, not an official company directive to rewrite all Microsoft code. Windows is specifically not being rewritten entirely in Rust.

Is Microsoft officially eliminating C and C++ from all its products?

No. Microsoft has clarified that C and C++ will remain in use for many systems, particularly where existing code is stable, performance is optimized, or compatibility is critical. The company is investing in Rust as a complementary language for new systems and selected migrations where memory safety is a priority, but there is no mandate to eliminate C and C++ from the entire company.

Why does memory safety matter so much that Microsoft is investing $10 million in Rust?

Memory safety bugs account for approximately 70% of security vulnerabilities in C and C++ code. These bugs include buffer overflows, use-after-free errors, and null pointer dereferences. Rust eliminates entire categories of these bugs at compile time, reducing security risks and maintenance costs. For an organization like Microsoft managing hundreds of millions of lines of code, even a small reduction in memory-related vulnerabilities translates to significant security and financial benefits.

Will C and C++ developers become obsolete?

No. C and C++ will remain important for systems programming for decades. What's changing is that new projects will increasingly choose Rust where memory safety is a priority, while existing C and C++ code often stays stable. Developers who understand both languages are particularly valuable. The smart approach is learning Rust as a supplement to C++ expertise, not as a replacement.

How does AI-powered code transformation actually work?

The system combines AI language models with algorithmic validation. AI handles pattern recognition and translation of common code structures. Algorithms handle formal verification, semantic checking, and performance validation. Humans review complex cases and make final decisions. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of each component: AI's pattern matching ability, algorithms' logical rigor, and human judgment on complex decisions.

What does this mean for Windows users and developers building on Windows?

For Windows users, there should be no immediate impact. Windows will continue to work as it does today. Gradually, components might become more stable and secure as Microsoft migrates selected systems to Rust, but this happens behind the scenes. For developers building applications on Windows, C/C++ remains viable and supported. Over time, Rust may become a preferred option for certain types of projects, but it would be an addition, not a replacement.

When will this infrastructure actually be available for other companies to use?

That's uncertain. If Microsoft releases these tools publicly, it could take 3-5 years. The company is likely still in research and proof-of-concept phases. More realistically, the approaches and techniques developed will influence the broader industry, with tools becoming available through open-source projects or from other vendors building similar solutions. Companies interested in large-scale code modernization might have tools available by 2027-2028.

Is Rust ready to replace C++ in all scenarios?

No. Rust is excellent for systems programming where memory safety is a priority, but it's not ideal for every use case. Embedded systems with extremely tight constraints sometimes prefer C. Real-time systems with strict latency requirements sometimes need C++'s fine-grained control. Scientific computing often relies on C++ libraries. Rust will expand its domain over time, but C++ will remain relevant for specific niches where its properties are valuable.

What if the AI-powered refactoring introduces bugs?

That's a core concern that drives the research project. The infrastructure is designed with multiple layers of validation: algorithmic checks ensure semantic correctness, existing test suites validate behavior, additional test generation covers edge cases, and humans review results before deployment. It's not relying on AI to be perfect; it's using algorithms and human expertise to catch AI mistakes.

How does this compare to other large-scale code migrations?

Code migrations of this scale are rare in history. Most companies avoid them because they're risky and expensive. What makes Microsoft's approach different is the investment in automation and AI-powered infrastructure. Instead of assigning thousands of engineers to manually refactor code, the company is building tools that can handle large portions automatically. This doesn't eliminate human work, but it makes the problem tractable where it previously wouldn't have been.

Conclusion: Understanding the Actual Stakes

When Galen Hunt posted about eliminating C and C++ by 2030, the internet heard a tech company declaring war on programming languages. What was actually happening was more nuanced: a research team was committing to explore whether AI-powered infrastructure could make large-scale code modernization feasible.

That's a different story. It's less dramatic but more important.

The tech industry has a serious problem that's been growing for two decades: technical debt. Legacy systems accumulate complexity. Every major company managing hundreds of millions of lines of code struggles with this. Traditional approaches (assigning teams to manually refactor) don't scale. You could assign 100 engineers and barely make progress.

Microsoft's experiment with AI-powered code transformation addresses this head-on. If successful, it establishes a playbook that other companies can follow. Instead of resigning yourself to maintaining legacy code, you build tools to transform it systematically.

The Rust aspect is important but secondary. Yes, Rust is memory-safe and increasingly important. Yes, Microsoft is investing in it. But the real innovation is the infrastructure for applying AI at scale to code understanding and transformation.

For developers, the implications are clear:

C and C++ aren't going extinct. They're evolving into specialized languages for specific use cases, while Rust captures new projects where memory safety is a priority. The industry is maturing from "performance above all" to "security and correctness above all." This shift doesn't eliminate C/C++ expertise; it just makes it one of several valuable skillsets.

For organizations, the implications are equally clear: large-scale modernization is becoming feasible. What once seemed impossible—refactoring millions of lines of legacy code—becomes tractable with the right tools.

For the industry broadly, Microsoft's commitment signals something important: memory safety matters enough that major tech companies are investing billions to address it. This isn't hype. It's recognition that memory bugs are expensive, and memory-safe languages provide measurable value.

The 2030 deadline might slip. The scope might narrow. The specific tools might change. But the direction is clear: the industry is moving toward memory-safe systems, gradually, with tools that make the transition feasible.

Hunt's research project isn't about eliminating languages. It's about establishing that systematic, large-scale modernization is possible. That's genuinely significant, even if it doesn't make for as catchy a headline as "C and C++ elimination by 2030."

Key Takeaways

- Microsoft's viral '2030 elimination' announcement was a research project, not corporate mandate, as clarified by engineer Galen Hunt

- The real innovation is AI-powered infrastructure for large-scale code transformation, with Rust as the target language

- Memory safety bugs cause 70% of security vulnerabilities in C/C++; Rust eliminates these bugs at compile time

- C and C++ won't disappear; instead, Rust will become the default for new systems-level projects, with gradual migration of legacy code

- Developers should learn Rust as a supplement to C++ expertise; combined knowledge of both languages is increasingly valuable

Related Articles

- Philips Hue Essential Review: Budget Smart Lights That Compete [2025]

- Plaud Note Pro Review: The AI Recorder That Fits in Your Wallet [2025]

- Ultrahuman Air Quality Monitor Review: Sleep & Health Impact [2025]

- Best Streaming Movies 2025: 12 Must-Watch Films [2025]

- Epilogue's SN Operator: Turn Your PC Into a Super Nintendo [2025]

- Stranger Things Season 5 Finale Release Date [2025]

![Microsoft's Rust Push Explained: Is C/C++ Really Going Away? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-rust-push-explained-is-c-c-really-going-away-202/image-1-1767035298313.jpg)