Minneapolis General Strike Against ICE: Inside the Movement [2026]

Introduction: When a City Decides Enough Is Enough

It was too cold to check my phone, so I just followed the crowd. That's how thousands of Minneapolis residents found themselves converging on Government Plaza on Friday, January 30, 2026, their breath crystallizing in the Minnesota winter as they walked toward one of the most significant collective actions the Twin Cities had seen in years. The temperature had dropped below freezing, but the momentum kept everyone moving.

I arrived expecting hundreds. What I found was a human tide so dense that counting became impossible. Five to ten thousand people, depending on who you asked, but on the ground it felt immeasurable, like a single organism vibrating with purpose.

This wasn't just another protest. This was a general strike. A coordinated economic shutdown organized largely by Somali and Black student groups at the University of Minnesota to demand accountability after federal immigration officers killed Alex Pretti in circumstances that still remain contested and contested. Unlike the first strike the previous week, endorsed by local unions with institutional backing, this one came together rapidly, powered by grassroots organizing and genuine rage.

What struck me most wasn't the size of the crowd. It was the duality of it. Here were thousands of people, many of them young, many of them speaking out for the first time in their lives at this scale, gathered together in a moment of profound civic rebellion. And yet they were unfailingly polite. Someone offered me a "Fuck ICE" pin. Someone else offered me a chocolate-chip cookie. Another handed me a red vuvuzela. All three declined to be named or interviewed. Only in Minnesota.

But there was nothing polite about what they were demanding. The underlying current of terror coursing through Minneapolis was palpable. You could feel it in the nervous energy of the medics standing by, the helicopters circling overhead, the volunteer marshals in neon vests stationed at every entrance. Here was a city that had learned, in just weeks, that danger lurks everywhere.

This is what happened on the ground when a city decides it's had enough.

The first strike on January 23 saw participation between 10,000 and 15,000, with an estimated average of 12,500. The second strike on January 30 had a slightly higher participation, estimated at 14,000. Estimated data based on narrative.

TL; DR

- The Strike Details: Minneapolis staged its second general strike in two weeks on January 30, 2026, with an estimated 5,000-10,000 participants protesting federal ICE enforcement following the death of activist Alex Pretti

- Organizers & Scope: The strike was organized by Somali and Black student groups at the University of Minnesota, moving faster and with less institutional backing than the previous week's union-endorsed action

- Dual Reality: The crowd maintained characteristic Minnesota politeness while expressing genuine rage, creating a unique tension between civility and justified anger

- The Context: Minneapolis had become the staging ground for unprecedented immigration enforcement actions, with the Whipple Federal Building serving as the hub for unmarked ICE operations targeting immigrants

- What's At Stake: The strike represents a pivotal moment in how American cities are responding to federal immigration enforcement, with implications for labor solidarity, immigrant protection, and civic resistance movements

The Death of Alex Pretti: What Sparked the Movement

You can't understand why thousands of Minneapolis residents took to the streets in the middle of winter without understanding Alex Pretti. The circumstances of his death created a rupture in the city's consciousness.

The details matter because they show a pattern. Federal immigration officers killed him. The exact circumstances remain contested, with conflicting accounts about what led to his death, how it unfolded, and whether it was justified. What isn't contested is this: a person is dead, and federal agents are responsible. That's not abstract. That's the starting point.

In a city that prides itself on civility, on decency, on "Minnesota nice," the killing shattered something fundamental. You could see it in how people talked about it. The politeness was still there, but it had hardened into something else. Resolve. Defiance. A recognition that politeness alone wasn't going to protect anyone.

The death became a focal point for something larger. Minneapolis has become increasingly visible as a site of aggressive federal immigration enforcement. The Whipple Federal Building, located in downtown Minneapolis, has become the staging ground from which ICE agents depart in unmarked cars to hunt down immigrants. The building has become the symbol of this enforcement apparatus.

For weeks before the strike, people had been gathering outside Whipple to conduct what they call "ICE watch." They stand there with phones ready, documenting everything they can see, trying to create a protective presence through visibility. It's a form of resistance born from understanding that documentation and attention are sometimes the only tools available to vulnerable people.

But someone can be doing ICE watch and be killed by a federal agent. That's what happened to Pretti. That knowledge transformed the nature of the resistance. It's no longer just about preventing deportations or documenting enforcement actions. It's about survival.

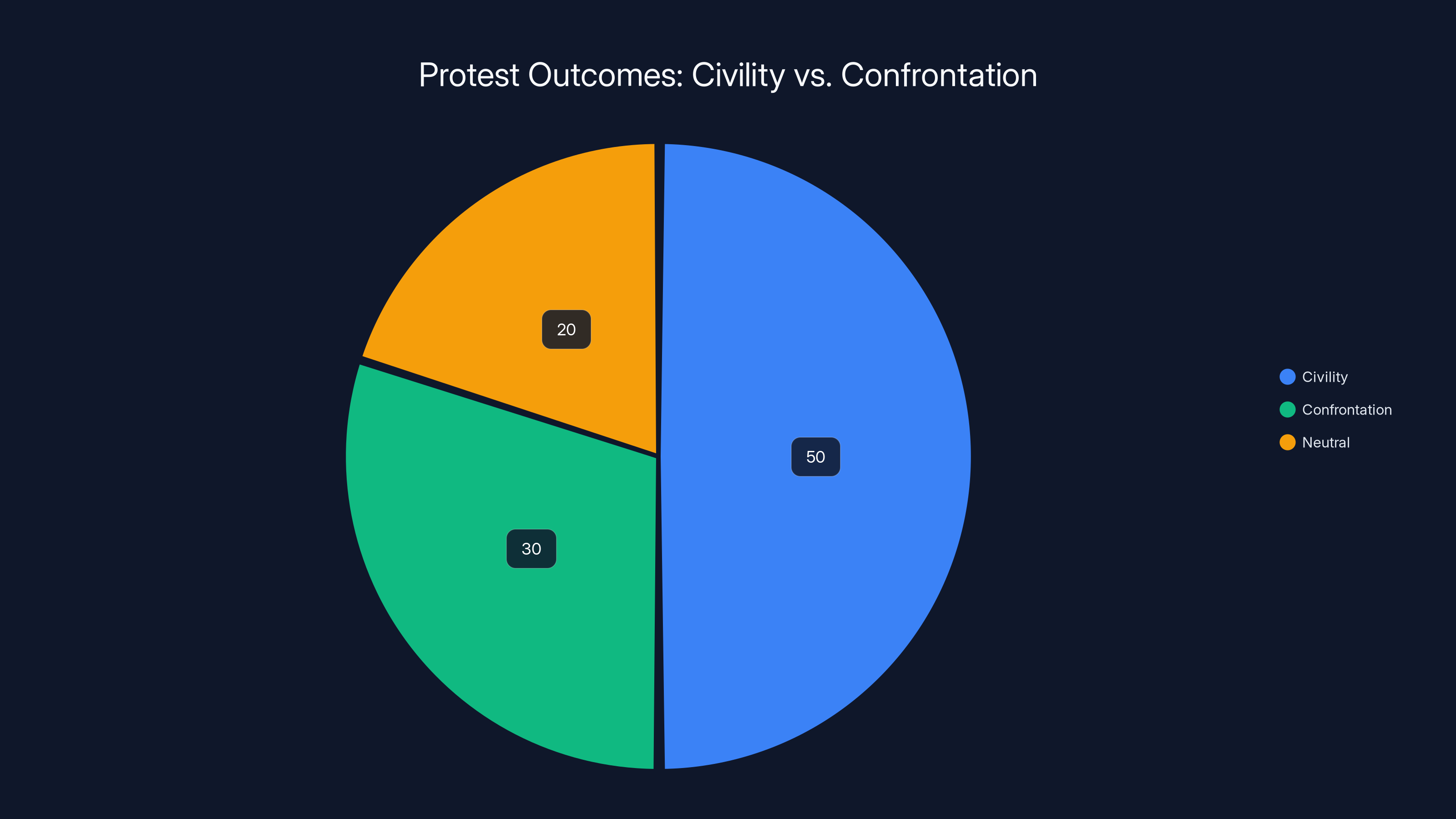

Estimated data suggests that civility in protests can lead to more effective outcomes compared to confrontational approaches, highlighting the strategic power of nonviolence.

The First Strike: Testing Solidarity

Before January 30 came January 23. The first general strike in the Twin Cities in recent memory.

That one was different. It had institutional backing. Major unions endorsed it. It was organized with the kinds of structures and logistics that only established labor organizations can bring to bear. When it happened, somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 people participated, depending on who counted and how they counted it.

But here's what surprised people: it actually worked. Businesses closed. Services stopped. The city felt the economic impact. When you coordinate enough people to withdraw their labor, withdraw their consumption, withdraw their participation in the normal flow of commerce, the system notices.

That's the power of a general strike. It's not a march where you show up for a few hours and then go home. It's an actual disruption. It's saying, we're not going to work today. We're not going to serve coffee today. We're not going to run the city today. Not until something changes.

The first strike validated something that had been theoretical until that moment: Minneapolis's labor force could actually do this. Could actually organize itself into an economic force. Could actually make demands that the city would have to reckon with.

So when the University of Minnesota's Somali and Black student groups decided to organize a second strike just seven days later, they were building on that momentum. But they were also operating with a different model. Faster. More grassroots. Less dependent on institutional structures.

Why Student Groups Led the Second Strike

There's a logic to why Somali and Black student groups took the lead on the second strike instead of waiting for union endorsement.

First, immediacy. When you're a young person in Minneapolis in January 2026, and federal agents are killing people you know about, waiting for union committees to schedule meetings feels like a betrayal of the moment. Students operate on a different timeline than institutional organizations. They can mobilize faster. They can decide in a day to do something and actually do it.

Second, direct stake. Many of these students have family members who are undocumented or have undocumented family members and friends. They're not organizing in solidarity with an abstract concept. They're organizing to protect people they care about. That changes the calculus. That removes some of the institutional caution.

Third, generational ownership. The first strike was powerful precisely because institutions organized it. But it also meant institutions controlled the narrative. A second strike organized by students meant that young people, who would inherit whatever comes next, were taking ownership of the resistance themselves.

I talked to several people at the strike, or tried to. Most declined to give their names or be interviewed. But one person did tell me that the speed of the student-organized strike was itself a statement. It said: we don't need permission structures to act. We don't need to wait for organizations to validate our choices. When something is wrong, we're going to respond. Now.

That's a different kind of power than what institutions provide. It's more chaotic, sure. It's less predictable. But it's also more authentic to the urgency of the moment.

Inside the Plaza: Five to Ten Thousand People and Counting

When I arrived at Government Plaza, across from Minneapolis City Hall, the crowd had already reached a density that made navigation difficult.

I kept saying "excuse me" and "pardon me," which tells you something about Minneapolis culture. Even in the middle of a general strike, surrounded by rage and justified anger, people apologize for taking up space. But I also kept slipping on the ice, and each time, someone caught me. That's the duality again: institutional politeness coupled with genuine solidarity.

The reported numbers ranged from five to ten thousand, but those numbers don't capture what it felt like on the ground. The crowd wasn't static. People kept arriving from the light rail station, seemingly defying the laws of physics, packing into spaces that were already full. And yet somehow they fit. The entire plaza became a single breathing organism.

The signs were everywhere. Hand-made signs. Professional signs. Signs that had clearly been made in someone's living room the night before. Signs that reflected different aspects of why people were there. Immigration justice. Labor solidarity. Defense of sanctuary cities. Condemnation of deportations. Condemnation of killing. The signs weren't uniform because the strike wasn't about one single message. It was about multiple forms of resistance converging in a single moment.

The chanting became the heartbeat of the plaza. "No more Minnesota nice, Minneapolis will strike." That phrase captured something essential. It said: we can be polite without being passive. We can maintain our dignity without accepting injustice. We can be from Minnesota and still be willing to shut it down.

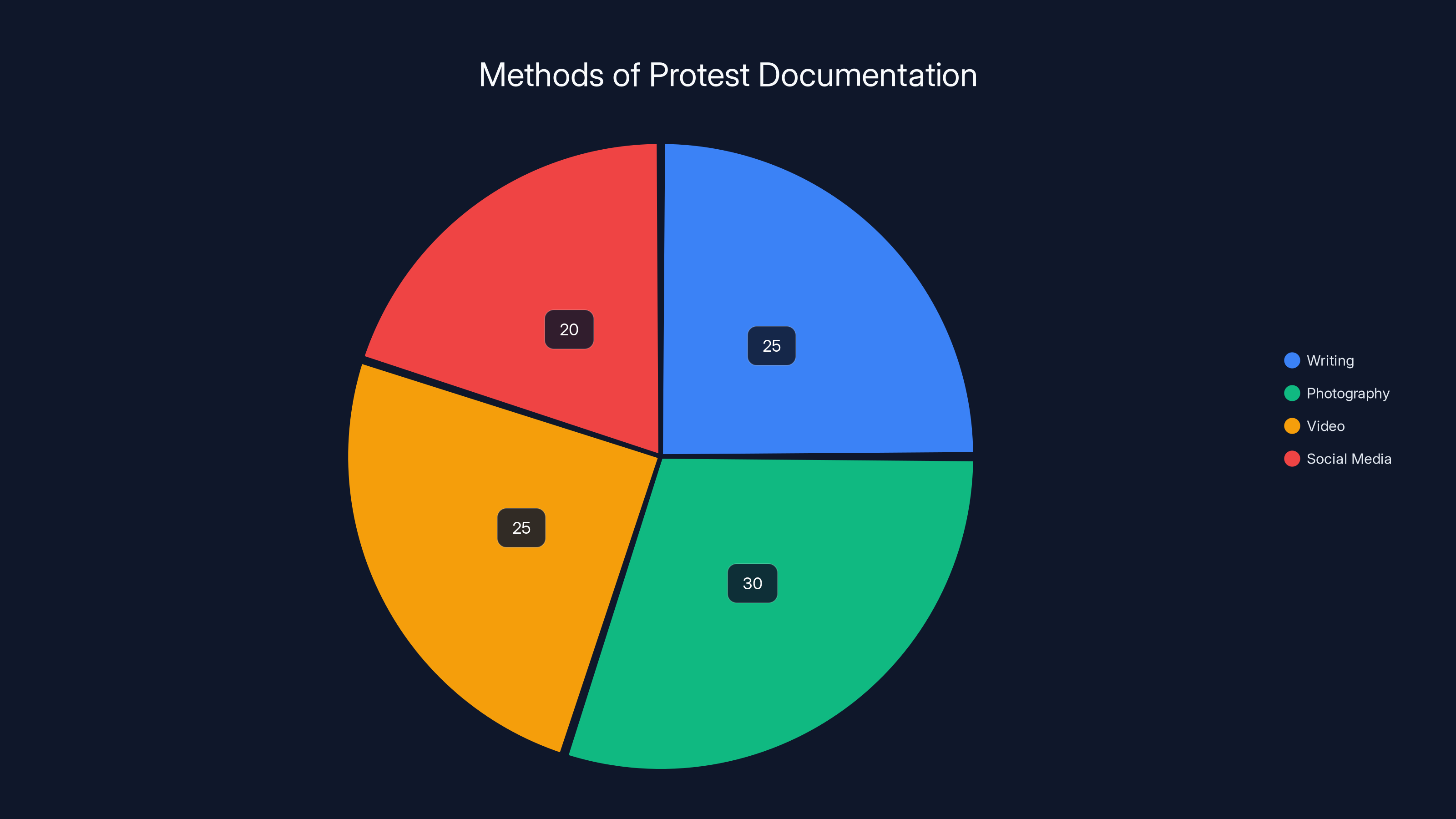

Estimated data shows a diverse use of documentation methods in protests, with photography and video being the most common. Estimated data.

The Helicopters, the Marshals, the Medics: Preparing for Violence

The presence of infrastructure designed to manage conflict told you everything you needed to know about what the city was expecting.

Helicopters circled overhead. Not constantly, but frequently enough that you couldn't forget they were there. Their presence communicated a message: we're watching. We're documenting. We're prepared to intervene. In situations where participants include young people, many of them first-time protesters, that presence affects behavior. It makes people more cautious. More aware that they're being observed and recorded.

Volunteer marshals in neon vests stood at nearly every entrance and street corner. They were directing the crowd, but they were also monitoring. One warned me about the ice. I didn't hear her and slipped, but a woman behind me caught my fall, and then immediately went back to her position in the crowd.

The marshals seemed to understand their role as both crowd organizers and de-escalators. They were trying to keep things peaceful not because peace was inherently the goal, but because they understood that any conflict could be used to delegitimize the entire action.

Medics milled about, prepared for the worst. They had medical supplies. They were scanning the crowd for people who might need assistance. They were positioned to respond quickly if things changed. Their presence suggested that organizers were genuinely expecting police response, tear gas, pepper spray, flash bangs. They were preparing for a scenario where the state responded to civil disobedience with violence.

Which makes sense. Because at Whipple Federal Building, just miles away, protesters had already been dealing with exactly that. People standing outside Whipple conducting ICE watch have been met with flash bangs. With pepper spray. With federal agents escalating rather than de-escalating.

One person told me that the earlier altercation outside Whipple had influenced how organizers approached the City Hall rally. They understood that being peaceful doesn't guarantee you won't face violence. But they also understood that preparation and organization could make a difference.

The Reality of Living in an ICE-Occupied City

You can be sitting in your car and be killed by a federal agent.

You can be doing ICE watch and be killed by a federal agent.

You can be protesting that killing and be arrested by federal agents.

You can be walking or driving to work and be snatched by a federal agent.

You can blow a whistle to alert your neighbors that federal agents are snatching someone off the street, and you'll end up, at the very least, pepper sprayed by a federal agent.

This is what it means to live in Minneapolis in early 2026. It means understanding that ordinary activities carry extraordinary risk if you're undocumented or have undocumented family members or friends. It means that the state's enforcement apparatus has become visible in new ways, more aggressive, more willing to deploy force.

The terror isn't abstract. It's the neighbor who doesn't show up to work because they're afraid to drive anywhere. It's the family that stops going to school pickup because they're worried about checkpoints. It's the parent who keeps their child's location tracker on at all times because they need to know, in case something happens.

Minneapolis has always been a city with a significant immigrant population. But the coordination and intensity of recent ICE enforcement represents something new. The Whipple Federal Building has become the physical manifestation of this enforcement apparatus, and its presence shapes how the entire city moves through the world.

The strike, in this context, isn't just about protest. It's about declaring that this level of fear is unacceptable. It's about saying that the city cannot function normally while parts of its population are living in constant terror. It's about withdrawing support for a system that produces this terror.

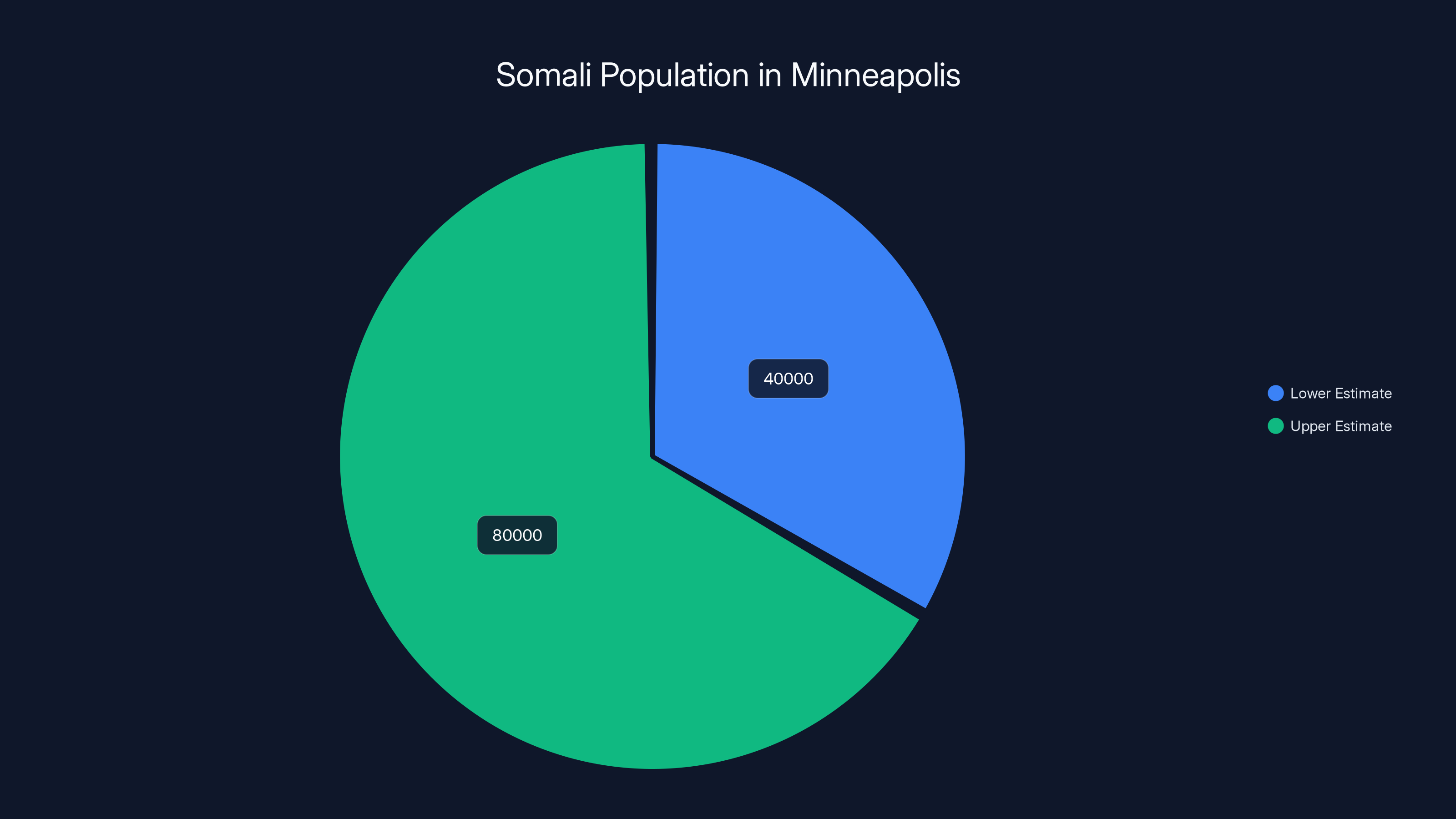

Somali Community Leadership and Community Care

The Somali community in Minneapolis has a specific history with immigration enforcement that shapes their leadership in this moment.

Minneapolis has one of the largest Somali populations in the United States, with somewhere between 40,000 and 80,000 people of Somali descent living in the metro area, depending on how you count. That community has built institutions, businesses, cultural spaces, schools. They've also faced specific targeting from law enforcement agencies over the past decades, both in terms of immigration enforcement and in terms of other policing practices.

When Somali student groups took the lead on organizing the second strike, they were operating from a position of experience. They understood what was at stake. They understood the mechanisms of enforcement. They understood the community structures that could be mobilized quickly.

But they also understood something about community care. At the strike, there was a memorial for Alex Pretti. There were people offering food, warmth, support to others in the crowd. There were people looking out for each other, making sure no one was isolated or vulnerable.

This is part of what makes community-led organizing different from top-down protest management. It's not just about getting people to show up. It's about creating spaces where people feel cared for, where their vulnerability is recognized and met with solidarity.

I watched this play out in small moments. Someone without gloves being offered hand warmers. Someone who looked lost being guided to the center of the crowd where the energy was strongest. Someone who looked overwhelmed being asked if they were okay and offered a place to sit.

This is the work that doesn't make it into official strike counts but that makes the difference in whether people feel like they're part of a movement or just part of a crowd.

Estimated data suggests that implementing sanctuary policies and increasing funding for immigrant services could have the most positive impact post-strike, while no action might lead to minimal change.

The Tension Between Civility and Rage

One of the strangest aspects of the Minneapolis strike was its fundamental contradiction: it was an action rooted in justified rage being carried out by people who maintained extraordinary civility.

In other cities, general strikes have escalated into confrontations with police. People have thrown objects. Fires have been set. Property has been destroyed. In Minneapolis on January 30, nothing like that happened at Government Plaza. The crowd remained peaceful throughout.

But the anger was real. You could feel it. The chants carried it. The signs expressed it. The fact that people had taken time out of their lives to stand in the freezing cold to demand change carried it.

I asked someone what accounted for this difference, and they said something like: "We know they're waiting for an excuse. We're not giving them one."

That's the calculus that Minneapolis protestors are operating under. They understand that the state has overwhelming force. They understand that police have the power to escalate. So they're deploying a different strategy: perfect discipline, perfect nonviolence, so that any escalation comes from the state, not from the crowd.

It's a strategy that requires enormous emotional labor. It requires people to contain rage in service of a larger goal. It requires understanding that your personal desire to express anger is secondary to the collective strategy.

And yet it's also a strategy that's been proven to work. The first strike, maintained with similar discipline, created real economic disruption. It forced the city to reckon with the fact that large numbers of people were refusing to participate in normal economic life.

So the civility isn't weakness. It's a different form of power. It's choosing not to give the state the excuse it's looking for to deploy overwhelming force. It's understanding that in a city like Minneapolis, controlled protest sometimes accomplishes more than confrontational protest.

Whipple Federal Building: The Focal Point of Conflict

If Government Plaza represented the aspirational face of the Minneapolis resistance movement, the Whipple Federal Building represented its confrontational reality.

The building sits in downtown Minneapolis. It's nondescript, the kind of federal building that blends into its surroundings until you know what happens inside it. Once you know, it becomes impossible to ignore. Inside Whipple, federal immigration officers coordinate enforcement operations. They plan raids. They manage detention facilities. They organize the apparatus that has been hunting undocumented immigrants across the region.

Outside the building, nearly constant protest has established itself. People conducting ICE watch stand with phones ready, documenting everything visible, trying to create a protective presence through visibility. It's a form of resistance born from understanding that visibility sometimes changes behavior.

But the Whipple protests have also been the sites of the most intense conflict. Federal agents have used flash bangs. They've deployed pepper spray. The dynamic is fundamentally different from Government Plaza. There's no pretense of peaceful coexistence. There's an explicit understanding that the state is willing to deploy force to protect this building and the operations happening inside it.

The fact that Alex Pretti died during ICE watch outside Whipple gives the building a different symbolic weight. It's no longer just a building where enforcement happens. It's a building where people have been killed. That transforms how people think about it. That transforms the stakes of showing up there.

One of the functions of the Government Plaza strike was to redirect the focus away from Whipple for a moment. To create a moment where the entire city was mobilized, not just the people willing to stand outside a federal building and face pepper spray every single day. To say: this is a citywide issue, not just an issue for the people most directly targeted.

The Role of University of Minnesota Student Groups

The University of Minnesota sits just a few miles from downtown Minneapolis. It's a large institution with significant resources and a large student body.

The decision by Somali and Black student groups at the university to take the lead on organizing the second strike represented a particular kind of institutional leverage. Students can mobilize quickly. They have communication networks. They have access to spaces where organizing can happen. They have some degree of protection that comes from being students at a large research institution.

But they're also young, which means they don't have the institutional caution that comes with age. They're not thinking about how their career might be affected. They're not worrying about reputation in the way that longtime organizers sometimes do. They're thinking about what's right and what's urgent.

The involvement of student groups also shifted the demographics of the strike. Younger people showed up who might not have shown up for a union-organized action. People who were discovering their political voice for the first time. People who were learning what collective action feels like.

That generational dimension matters for thinking about what comes next. If young people learn that organizing works, if they learn that gathering with other people and refusing to participate in normal life produces results, they'll do it again. They'll get better at it. They'll develop more sophisticated strategies.

Institutions were also nervous. The University of Minnesota administration presumably knew that students were organizing a general strike but faced a delicate situation. Suppress student organizing too aggressively and you create backlash. Allow it too readily and you look like you're endorsing economic disruption. Most institutions chose a middle path of not intervening but also not supporting.

The Somali population in Minneapolis is estimated to be between 40,000 and 80,000, highlighting the significant presence and influence of this community. Estimated data.

Organizing at Speed: How the Second Strike Came Together

The second strike came together in roughly a week. That's extraordinarily fast for coordinating thousands of people.

Part of what made it possible was the foundation laid by the first strike. People already understood what was possible. They'd already experienced what a general strike felt like. They already had communication networks from the first action that could be mobilized again.

Part of what made it possible was social media. Information about the planned strike spread through networks very quickly. People who hadn't been involved in the first strike learned about the second one through their phones. They told their friends. Their friends told their friends.

Part of what made it possible was the clarity of the demand. Alex Pretti had been killed. People wanted accountability. That's simple and powerful. It doesn't require elaborate negotiation or complex messaging strategy. It just requires people understanding that something is wrong and that gathering together and refusing to participate in normal life is a way of expressing that wrongness.

But organizing at speed also has costs. There's less time to vet people. Less time to work through differences. Less time to think through all the contingencies. The organizers were clearly doing their best to manage these challenges, deploying marshals, positioning medics, trying to create safety within a rapidly organized action.

I talked to someone who was helping coordinate the marshals, and they said something like: "Everything is improvised. We're learning as we go. But people are showing up because they care, and that means we figure it out."

That approach to organizing is different from more established models. It's more chaotic, definitely. It's also more authentic to the actual experience of people learning to organize in real time.

The Economics of the Strike: Real Disruption or Symbolic Action?

Here's the question everyone was asking: did the second strike actually create economic disruption, or was it primarily symbolic?

The first strike, with union backing, clearly disrupted normal economic activity. Businesses closed. Services stopped. You could measure the impact. The second strike, without union backing, probably created less concrete economic disruption, though there were still businesses that closed in solidarity and workers who participated.

But saying it was "just symbolic" misses what symbols do. Symbols move people. Symbols change how people think about what's possible. Symbols reshape the political landscape. The fact that thousands of people gathered on a freezing day to demand change sends a message that can't be measured in direct economic terms.

What the second strike created was a follow-up action. It demonstrated that the first strike wasn't just a one-time event. It showed that the resistance had staying power. It showed that people were willing to do this again.

That matters politically because it changes how institutions think about the issue. If something happens once, you can dismiss it as anomalous. If it happens twice in a week, you have to reckon with the possibility that it will keep happening until something changes.

Both types of strikes were probably necessary. The first strike established that collective action was possible. The second strike established that it was sustainable. Together, they constitute a different political moment in Minneapolis.

Responding to the Crisis: What Government and Institutions Could Do

The Minneapolis response to federal immigration enforcement has exposed something about how cities relate to federal power.

Cities have limited actual authority over federal immigration enforcement. They can't order ICE agents to leave. They can't shut down the Whipple Federal Building. They can't override federal immigration law.

But they can choose sanctuary city policies. They can limit cooperation between local police and federal agents. They can provide resources to immigrants facing deportation. They can choose not to cooperate with federal enforcement. They can use their convening power to mobilize resistance.

Some of this is already happening in Minneapolis. The city has sanctuary policies. Local police have limited cooperation with federal immigration enforcement. But it's not enough to address the scale and intensity of what's happening.

Institutions like the University of Minnesota could do more. They could divest from institutions that profit from immigration enforcement. They could provide resources and legal support to immigrants facing deportation. They could use their resources to house and protect vulnerable people.

Businesses could do more. They could refuse to cooperate with federal enforcement. They could provide paid time off for employees who want to participate in resistance actions.

None of this is simple. But the strike represents people saying: this moment requires more than what's currently happening. It requires institutions to take risks. It requires people with resources to use those resources in solidarity with the most vulnerable.

Social media had the highest impact on organizing the second strike quickly, followed closely by the foundation laid by the first strike. Estimated data.

What Comes Next: Building Sustained Resistance

Two strikes in a week is remarkable. But it also raises the question of sustainability.

Can rallying the same people to the same level of engagement week after week, indefinitely? That's extraordinarily difficult. People need to return to their lives. Burnout is real. Organizing at this scale requires enormous emotional and logistical labor.

But the alternative is acceptance. It's acknowledging that federal immigration enforcement will continue unimpeded. It's accepting that Alex Pretti's death doesn't require systemic change.

So what does sustained resistance look like? Probably a combination of different tactics. Ongoing presence at Whipple. General strikes occasionally, but not weekly. Support for legal cases related to the killing. Building relationships across communities so that the organizing infrastructure persists even when there aren't active mobilizations.

It also means thinking about what would constitute victory. Would it be federal agents pulling out of Minnesota? Would it be accountability for killings? Would it be sanctuary city policies becoming absolute? Different people probably have different answers to that question.

One of the functions of movements is that they create conversations about what's actually possible. They reshape the boundaries of what can be demanded. What seemed impossible a month ago, shutting down an entire city's economic activity for a day, now seems like something that can happen.

That shift in what's possible is itself a victory, even if it doesn't immediately change federal policy.

The Role of Media and Documentation

I was there as a reporter, documenting the strike through writing and observation. Many other people were documenting it through photography, video, social media. The documentation itself becomes part of the action.

When you're a protester and you know that what you're doing is being documented, recorded, shared, that changes your sense of what you're part of. You're not just gathering. You're creating a record. You're creating something that can persist beyond the moment, that can be shared with people who weren't there, that can be used to tell the story of what happened.

But documentation also has risks. Photos and videos can be used by law enforcement to identify people, to follow up later. Documentation can expose people to retaliation. That's something I thought about as I was writing and observing. I'm contributing to a record that could have consequences for people.

At the same time, documentation can protect people. When actions are recorded, when there are witnesses, it's harder for the state to act with absolute impunity. Visibility sometimes changes behavior. Which is probably why people at Whipple conduct ICE watch with phones, understanding that documenting might be the only protection available to vulnerable people.

Lessons for Other Cities: Can This Be Replicated?

What Minneapolis has accomplished in terms of organizing rapid, large-scale resistance actions matters beyond Minneapolis.

Other cities with immigrant populations facing ICE enforcement might look at what happened and think: could we do this in our city? What would we need to organize something like this?

Partly, it's about scale. Minneapolis has enough population and enough resources that coordinating a strike that includes thousands of people is logistically feasible. Smaller cities might have different challenges.

Partly, it's about existing infrastructure. The University of Minnesota provided organizing capacity. Existing activists from the first strike provided organizing experience. Community institutions provided meeting spaces. Not every city has all of these elements equally developed.

Partly, it's about trigger events. The killing of Alex Pretti provided an emotional moment that mobilized people. Not every city has recent deaths that crystallize the issue in the same way, even though immigration enforcement is ongoing everywhere.

Partly, it's about political opportunity. Minneapolis has some institutional structures that support sanctuary city policies and immigrant protection. Other cities might have more hostile institutional environments.

But the basic model is replicable. A trigger event plus existing infrastructure plus the willingness to try rapid mass mobilization can create change. Other cities will be watching Minneapolis to see what's learned, what strategies work, what mistakes are made.

Living in the Aftermath: The Weeks That Follow

The strike happened on January 30. But the consequences extend beyond that day.

For people who participated, there's likely some sense of having been part of something significant. There's also the question of what happens next. Do you attend the next action? Do you become an organizer? Do you return to your life, changed by the experience but not fundamentally altered?

For the city's institutions, there's probably pressure to respond. To do something that shows they're taking the resistance seriously. Maybe that's increased funding for immigrant services. Maybe it's more explicit sanctuary city policies. Maybe it's nothing, depending on who controls the institutions.

For the immigrant community, the immediate aftermath is probably anxiety. Will ICE enforcement accelerate in response to the protests? Will the attention make it more dangerous or less? Will the resistance actually produce change or just make things worse?

For the organizers, the aftermath includes reflection. What worked? What didn't? What would we do differently next time? How do we build on this momentum without burning people out?

These are the questions that shape whether something like the Minneapolis strikes becomes a turning point in how immigration policy is contested in American cities, or whether it remains a moment that passed without producing lasting change.

FAQ

What is a general strike and how is it different from a normal protest?

A general strike is a coordinated withdrawal of labor where workers across industries refuse to work on a specific day or until demands are met. Unlike a typical protest march where participants gather for a few hours and then disperse, a general strike creates actual economic disruption by stopping commerce, services, and normal economic activity. The Minneapolis general strikes involved not just employees withdrawing labor but also supporters refusing to participate in commerce, making it a citywide action rather than just a protest event.

Why did federal immigration enforcement become such a flashpoint in Minneapolis?

The intensity of ICE enforcement in Minneapolis, centered around the Whipple Federal Building as a regional hub, combined with the controversial death of Alex Pretti during an immigration enforcement action, transformed abstract immigration policy into an immediate, visible threat for the immigrant community and their supporters. Minneapolis has one of the largest Somali populations in the United States, and the community has direct experience with both immigration and policing enforcement, making the issue particularly urgent and mobilizable.

How can a city actually resist federal immigration enforcement if immigration is a federal responsibility?

While immigration enforcement is technically federal authority, cities have significant leverage through sanctuary policies, limiting local police cooperation with ICE, providing legal resources, protecting undocumented immigrants in city services, and using their convening power to mobilize resistance. Additionally, the political and economic disruption created by widespread resistance can pressure federal agencies and the broader political system to reconsider enforcement strategies.

What makes student-led organizing different from union-led organizing?

Student organizations can mobilize faster because they operate without the institutional caution and committee structures that unions navigate. Students also tend to have more direct stakes in immigration issues if they have undocumented friends or family members. However, student organizing often has less economic leverage since students aren't withdrawing labor directly. The most powerful actions combine both student mobilization speed and union economic power.

How do participants maintain nonviolent discipline in situations involving police violence and pepper spray?

Maintaining nonviolent discipline requires participants to understand it as a strategic choice rather than a moral failing. By remaining nonviolent despite state violence, protesters make the state's escalation visible and illegitimate. Marshals, medics, and clear communication help enforce this discipline. However, it requires significant emotional labor and preparation to contain justified rage in service of a larger strategic goal.

What would it take to build sustained resistance to immigration enforcement rather than just one-off strikes?

Sustained resistance requires multiple tactics beyond occasional general strikes, including ongoing ICE watch outside enforcement facilities, legal support networks, community protection systems, institutional changes like explicit sanctuary policies, and regular organizing meetings that keep communities connected even when there aren't active mobilizations. It also requires addressing questions of what victory would look like and what demands the resistance is making.

Conclusion: A City Learning to Demand Change

When thousands of Minneapolis residents gathered at Government Plaza on a frozen January day, they weren't just staging a protest. They were testing their collective power. They were experimenting with what it feels like to say no to the normal functioning of a city. They were learning that massive coordination is possible, that people will show up for each other, that together they constitute a force that institutions have to reckon with.

The strikes succeeded in ways that are easy to count: economic disruption, media attention, visible demonstration of widespread dissatisfaction with federal immigration enforcement. They succeeded in ways that are harder to count: people learning that they can organize, understanding what solidarity feels like, discovering that their participation matters.

But whether the strikes produce lasting change remains to be seen. Will federal immigration enforcement decrease? Will ICE operations cease? Will accountability be established for Alex Pretti's death? These are still open questions.

What's certain is that Minneapolis has shifted. The city has learned what it's capable of. It has learned that general strikes are possible. It has learned that rapid mobilization can bring thousands of people into the streets. It has learned that people are angry enough to endure freezing cold and potential danger for a moment of collective resistance.

In a city built on the mythology of politeness and civility, what happened on January 30, 2026, represented something new. It represented people choosing civility not as acceptance but as strategy. It represented rage contained and channeled toward specific targets. It represented a community saying: this level of fear is unacceptable, and we're willing to take risks to change it.

What comes next depends on whether institutions choose to respond seriously to these demonstrations of collective will, and whether the movement can sustain itself beyond the initial mobilization. But the foundation has been laid. Thousands of people have proven that change through collective action is possible. They've proven that Minneapolis can be mobilized. They've proven that federal immigration enforcement will face significant resistance if it continues.

In a moment when many people feel powerless in the face of federal authority, the Minneapolis strikes represent something different: people learning that power comes not from institutions but from each other. That's a lesson that will echo beyond Minneapolis.

Key Takeaways

- Minneapolis staged a second general strike in a week on January 30, 2026, with 5,000-10,000 participants protesting ICE enforcement following Alex Pretti's controversial death

- The strike was organized by Somali and Black student groups at the University of Minnesota, demonstrating rapid grassroots mobilization different from the previous week's union-backed action

- Participants maintained extraordinary civility and discipline during the action despite underlying justified rage, using nonviolence as a strategic choice rather than moral inevitability

- The Whipple Federal Building serves as the regional hub for ICE operations and has become both a protest focal point and site of escalated federal agent violence against participants

- The dual strikes demonstrate a shift in American protest tactics: cities are learning to mobilize collective economic power to resist federal enforcement of immigration policy

Related Articles

- Inside Minneapolis ICE Shooting and Protest Response [2025]

- How to Film ICE & CBP Agents Legally and Safely [2025]

- Don Lemon and Georgia Fort Arrested for Covering Anti-ICE Protest [2025]

- When Federal Enforcement Changes Everything: How Communities Adapt [2025]

- How Communities Respond to Immigration Enforcement Crises [2025]

- Disney's Thread Deletion Scandal: How Brands Mishandle Political Content [2025]

![Minneapolis General Strike Against ICE: Inside the Movement [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/minneapolis-general-strike-against-ice-inside-the-movement-2/image-1-1769891761063.jpg)