Introduction: The Future of Robot Sensation

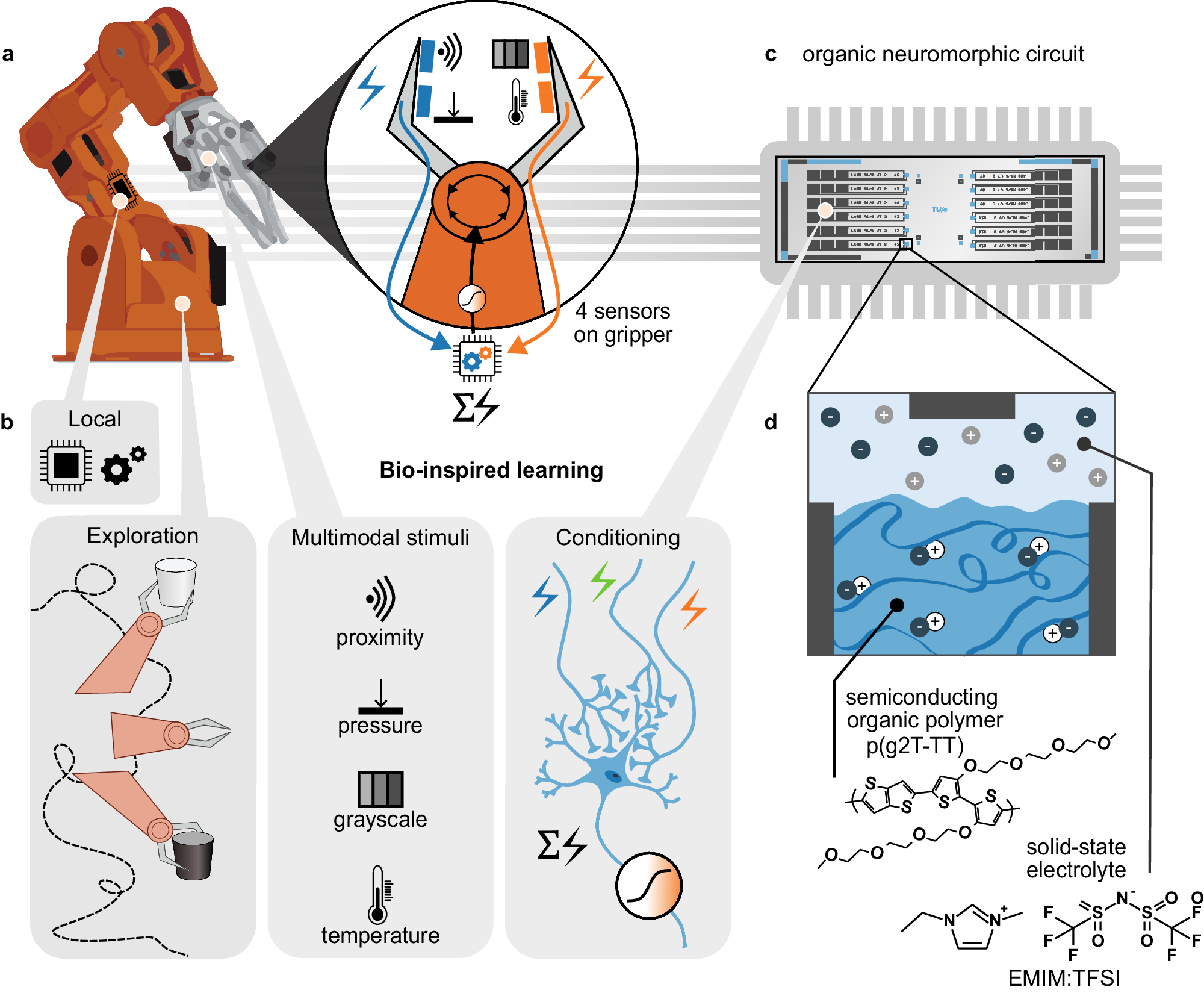

Robots have always been blind in ways that matter. They can process images, detect obstacles, even identify objects with remarkable precision. But when it comes to touch, pressure, pain, and the complex world of physical sensation, they've been operating in the dark. Your skin does something extraordinary every second of every day: it gathers information from millions of sensory receptors, processes that information locally, sends signals to your spine and brain, and triggers responses without waiting for conscious thought. A robot covering a delicate object? No problem. A robot arm touching something hot? It should recoil immediately, not wait for a command from a distant processor.

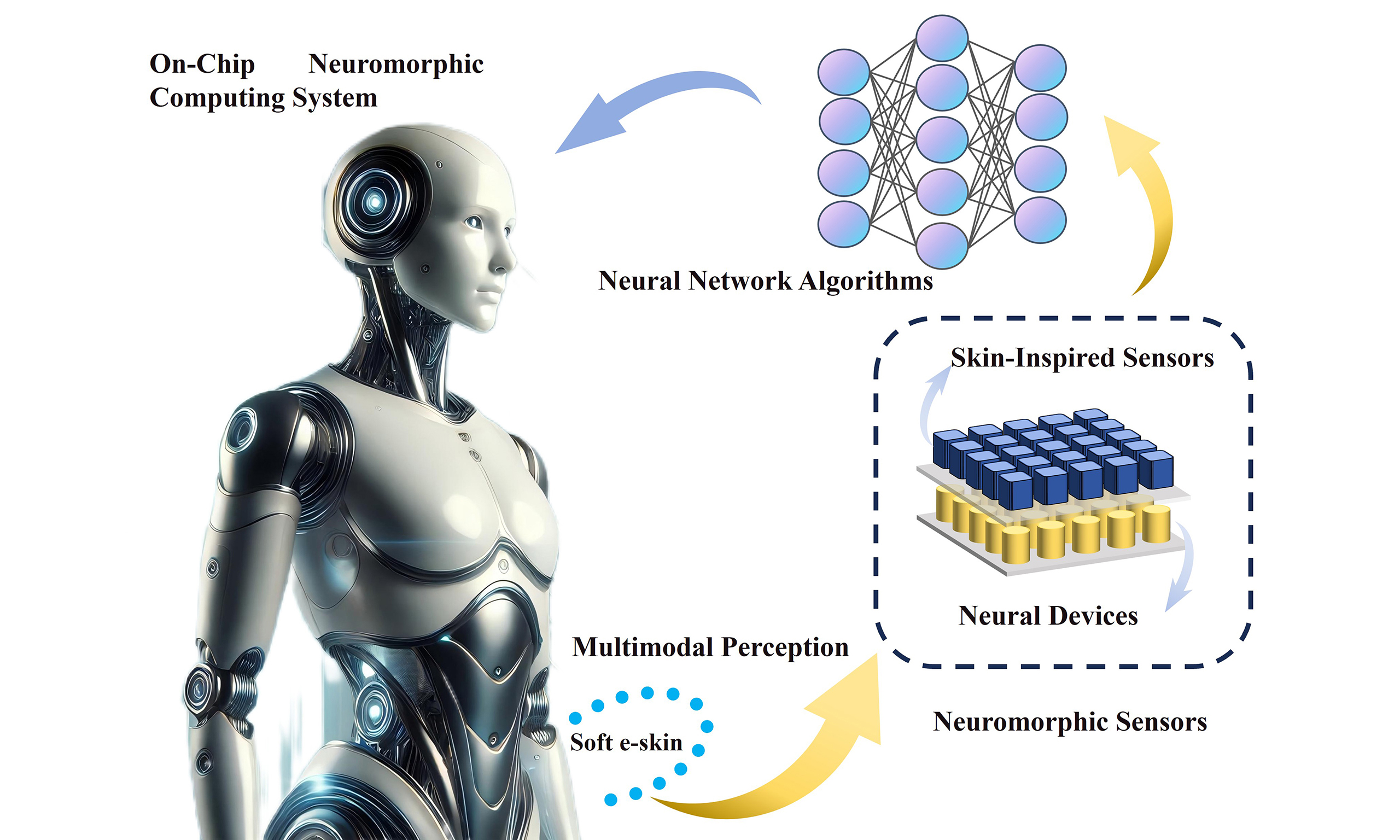

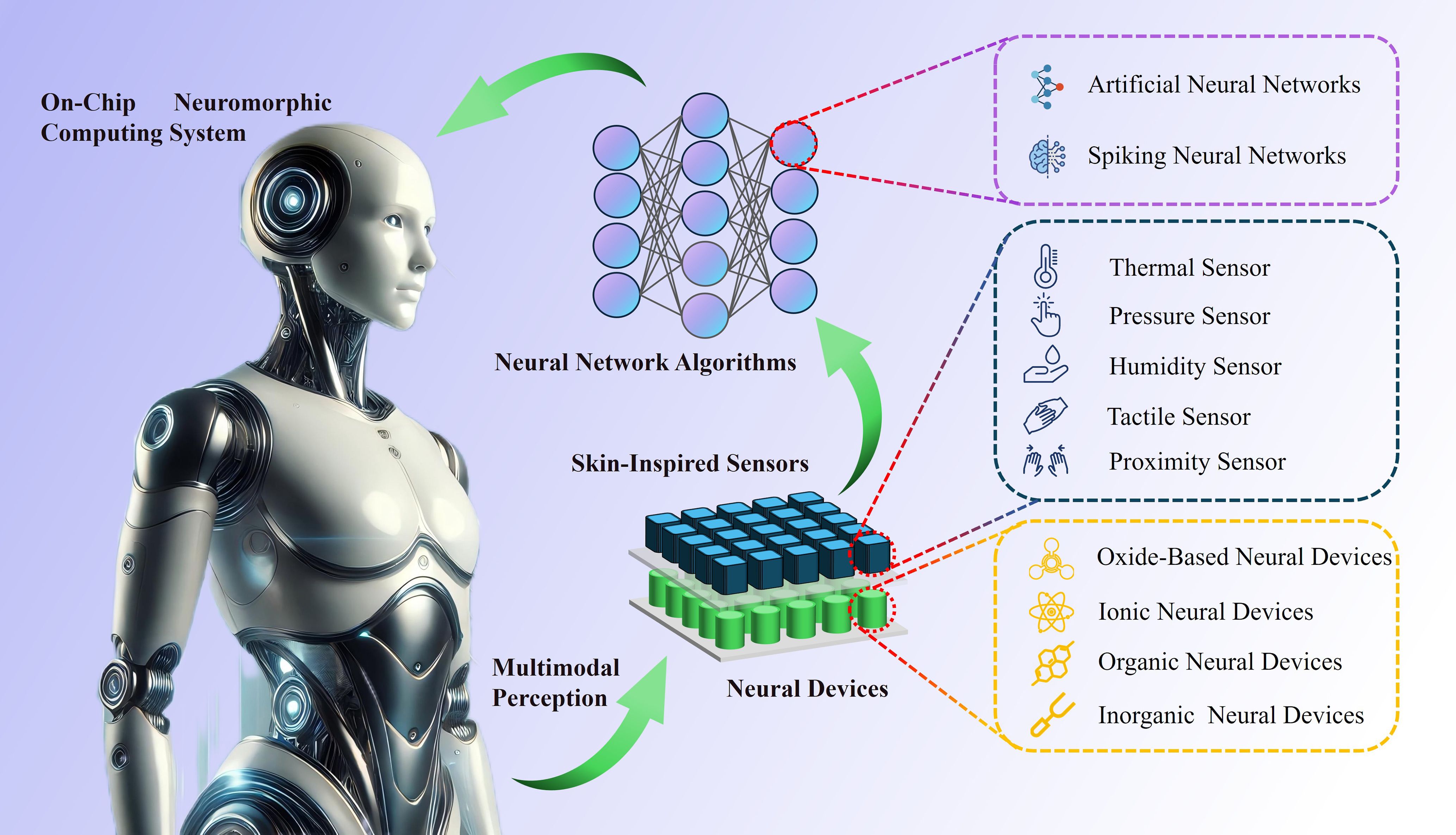

This gap between what humans sense and what robots perceive is about to narrow dramatically. Researchers have developed what they're calling neuromorphic artificial e-skin, or NRE-skin, a fundamentally new way for robots to feel their environment. Instead of treating sensory input as data points to be collected and processed separately, this approach borrows directly from how your nervous system actually works. It uses spiking signals, the same electrical pulses that transmit information through your body, to create a distributed, efficient sensory system that can integrate with energy-efficient AI hardware.

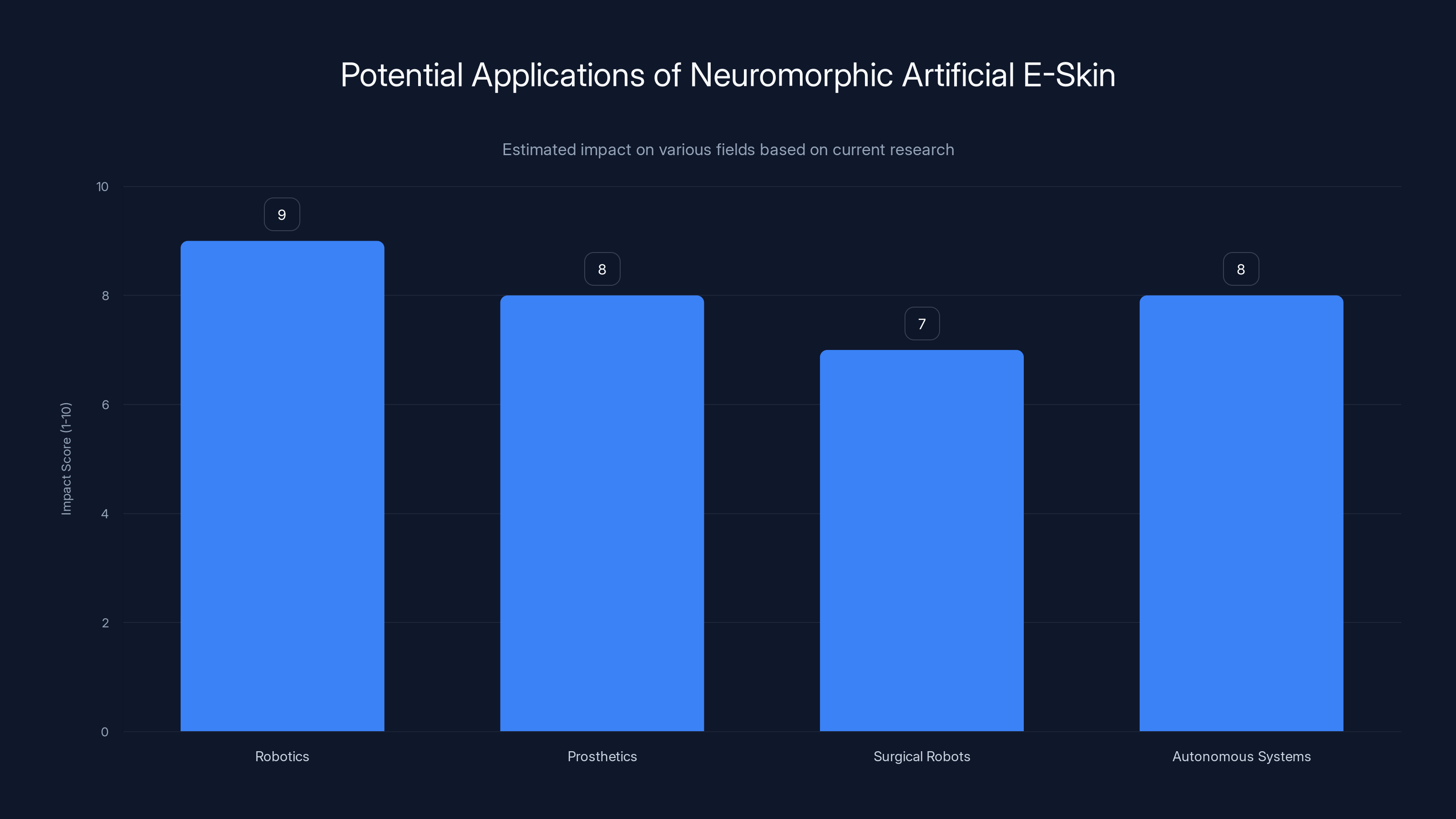

What makes this development significant isn't just that robots will be more responsive. It's that we're finally cracking a problem that's plagued robotics for decades: how to give machines a nervous system that works the way nature intended. The implications reach far beyond robotics. We're talking about prosthetics that feel like real limbs, surgical robots that can sense tissue texture and detect problems humans might miss, and autonomous systems that respond to their environment with the speed and sophistication of living creatures.

The research team, based in China, didn't set out to perfectly replicate human skin. Instead, they took core principles from neuroscience—how neurons communicate, how sensory information gets prioritized, how local processing prevents overloading higher-level systems—and built a practical system that works with existing hardware and chips. This is the art of biological inspiration: take what nature does brilliantly, understand why it works, then adapt those principles to engineering problems in ways that make sense for the constraints you're actually facing.

In this deep dive, we'll explore how this system actually works, what makes it fundamentally different from conventional robotic sensing, and what it means for the future of machines that can truly interact with the physical world.

TL; DR

- Neuromorphic artificial skin uses spiking neural signals to transmit sensory information from pressure sensors, mimicking how biological nervous systems communicate

- The system enables distributed processing with local reflex-like responses and multi-layer signal integration, reducing latency and computational overhead

- Magnetic modular design allows field repair with automatic wiring and unique identity codes for each skin segment

- Energy efficiency and AI integration make the system practical for real-world robotic applications that need responsive, adaptive control

- Current implementation focuses on pressure sensing, but the architecture supports expansion to temperature, texture, and other sensations

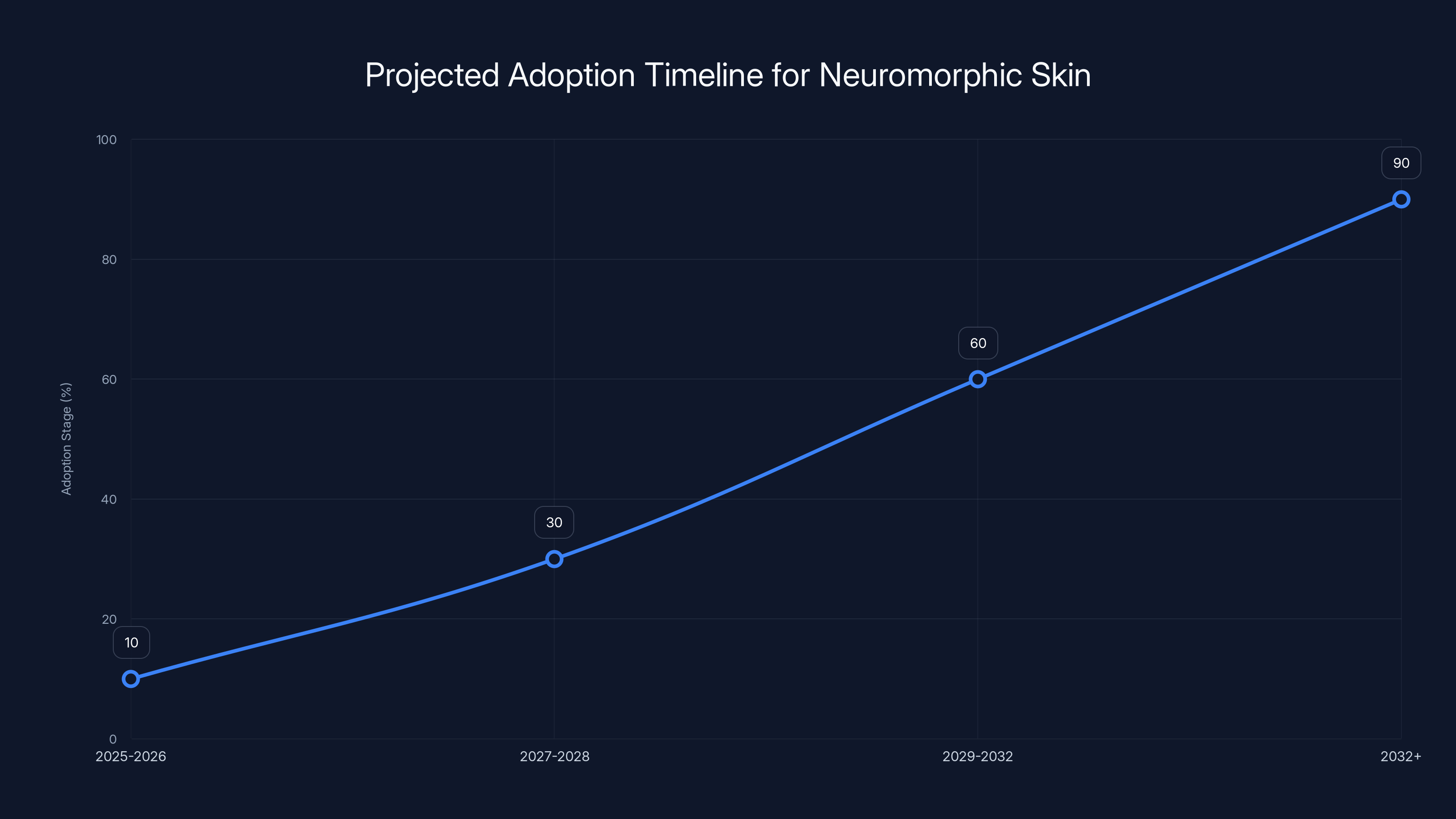

Estimated data shows gradual adoption of neuromorphic skin, with mainstream integration expected post-2032 as costs decrease and technology matures.

Understanding the Problem: Why Robot Skin Matters

Beforeabouts, let's talk about why we even need artificial skin on robots. Most industrial robots operate in carefully controlled environments. They follow predetermined paths, pick up objects at designated spots, and perform repetitive tasks with mechanical precision. But the next generation of robots—the ones that work alongside humans, assist in surgery, handle delicate goods, or explore unpredictable environments—need something more.

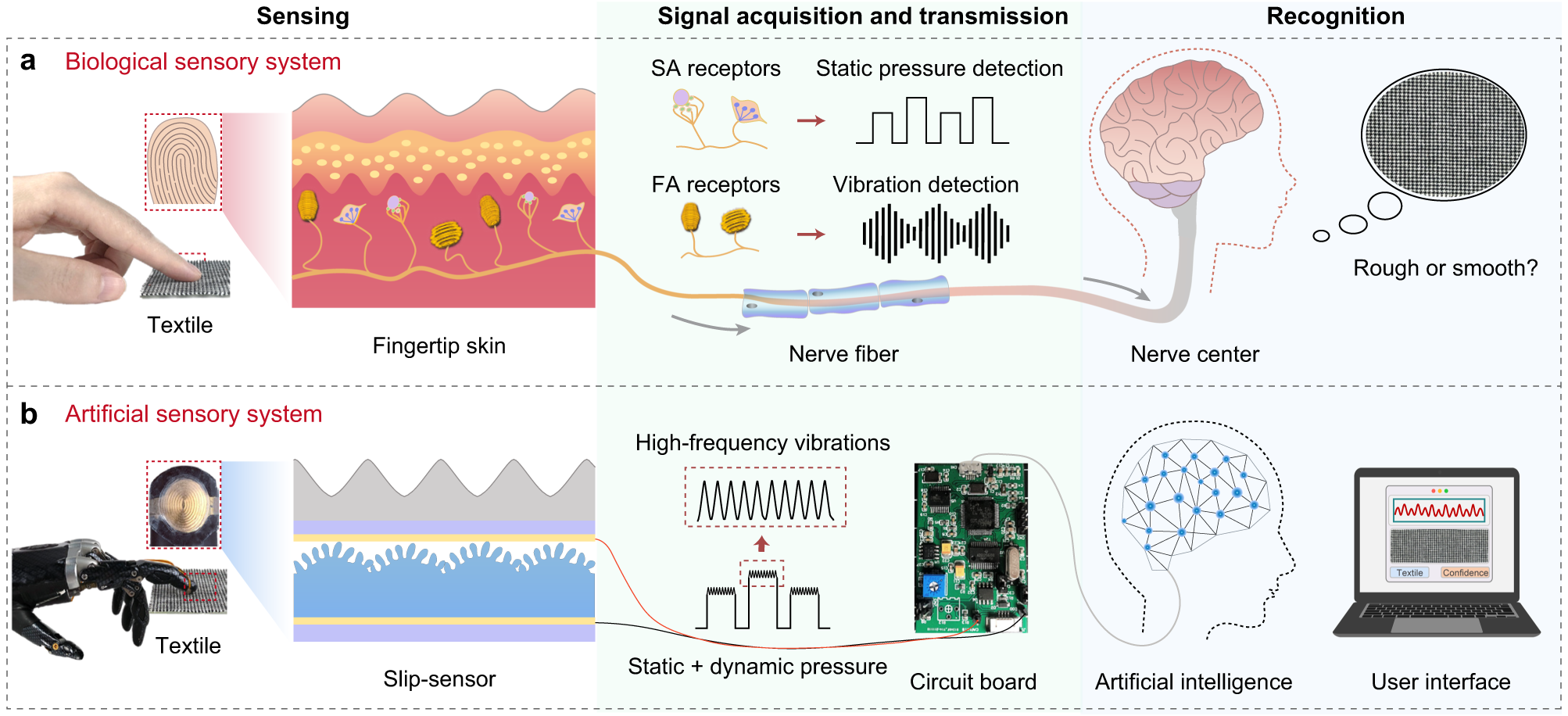

When a human reaches into a drawer of eggs, you're not thinking consciously about force control. Your skin is constantly sending microsecond-by-microsecond updates about pressure distribution across your palm and fingers. Your spinal cord is already monitoring whether you're crushing the eggs too hard. By the time conscious awareness kicks in, your body has already adjusted grip force multiple times. This happens because sensory input doesn't wait for the brain to process everything. Some signals trigger immediate reactions at the spinal level.

Robotic arms, by contrast, typically use force sensors at the wrist or gripper. All the sensory information gets sent to a central control system, which processes it, makes a decision, and sends a command back. Each cycle takes milliseconds at best, but in a world where biological systems operate on the scale of microseconds to milliseconds, that lag matters. It's like trying to catch a falling object while wearing a glove that insulates you from all sensation. You can't react naturally. You have to think about every adjustment.

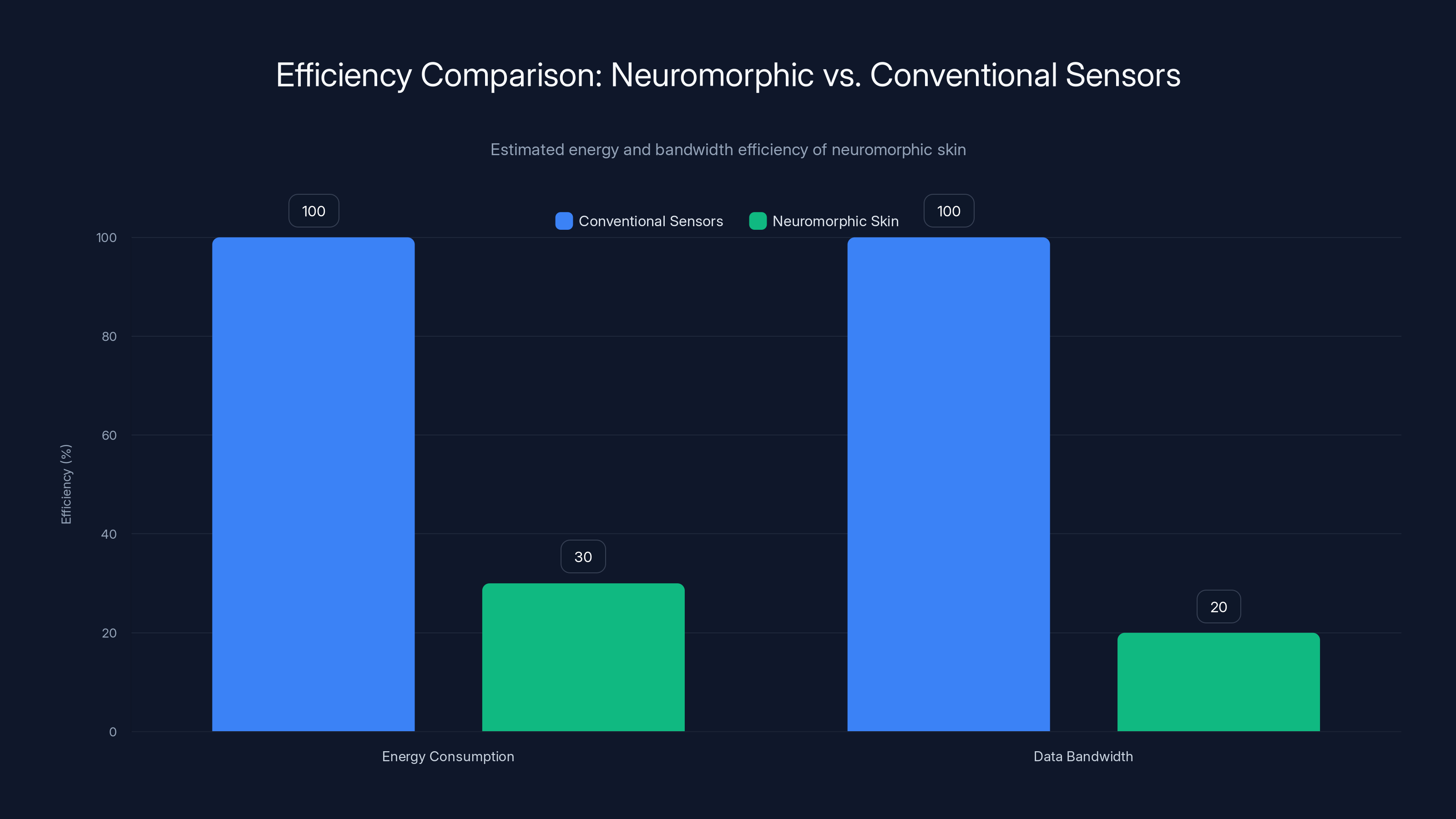

There's also the question of energy efficiency. A conventional sensory system might use high-frequency data streaming, constant A/D conversion, and continuous processing in a central microcontroller or computer. This drains batteries quickly and requires substantial computational power. Biological systems, meanwhile, are extraordinarily efficient. They transmit information using sparse, event-driven signals. Your sensory neurons don't constantly broadcast data at maximum volume. They fire pulses when something changes, when something matters, when action might be needed.

For robots to operate effectively in real-world scenarios—especially those with battery constraints or where computational resources are limited—they need sensory systems that behave more like biological nervous systems. Enter the neuromorphic approach.

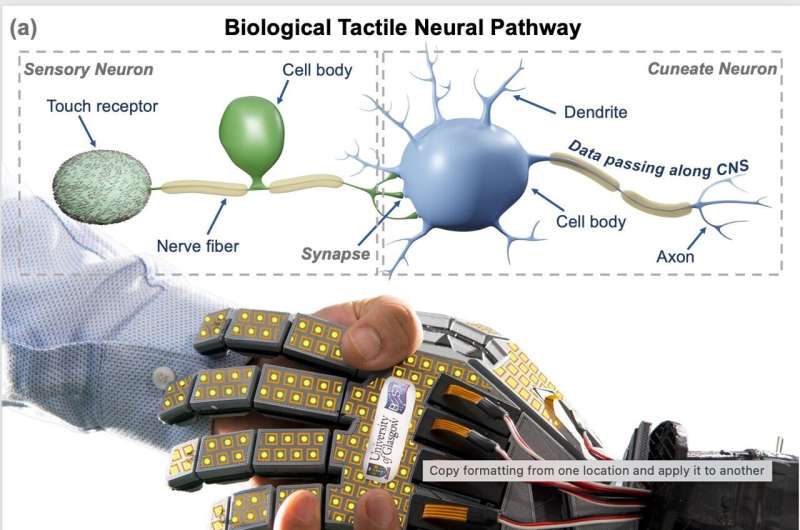

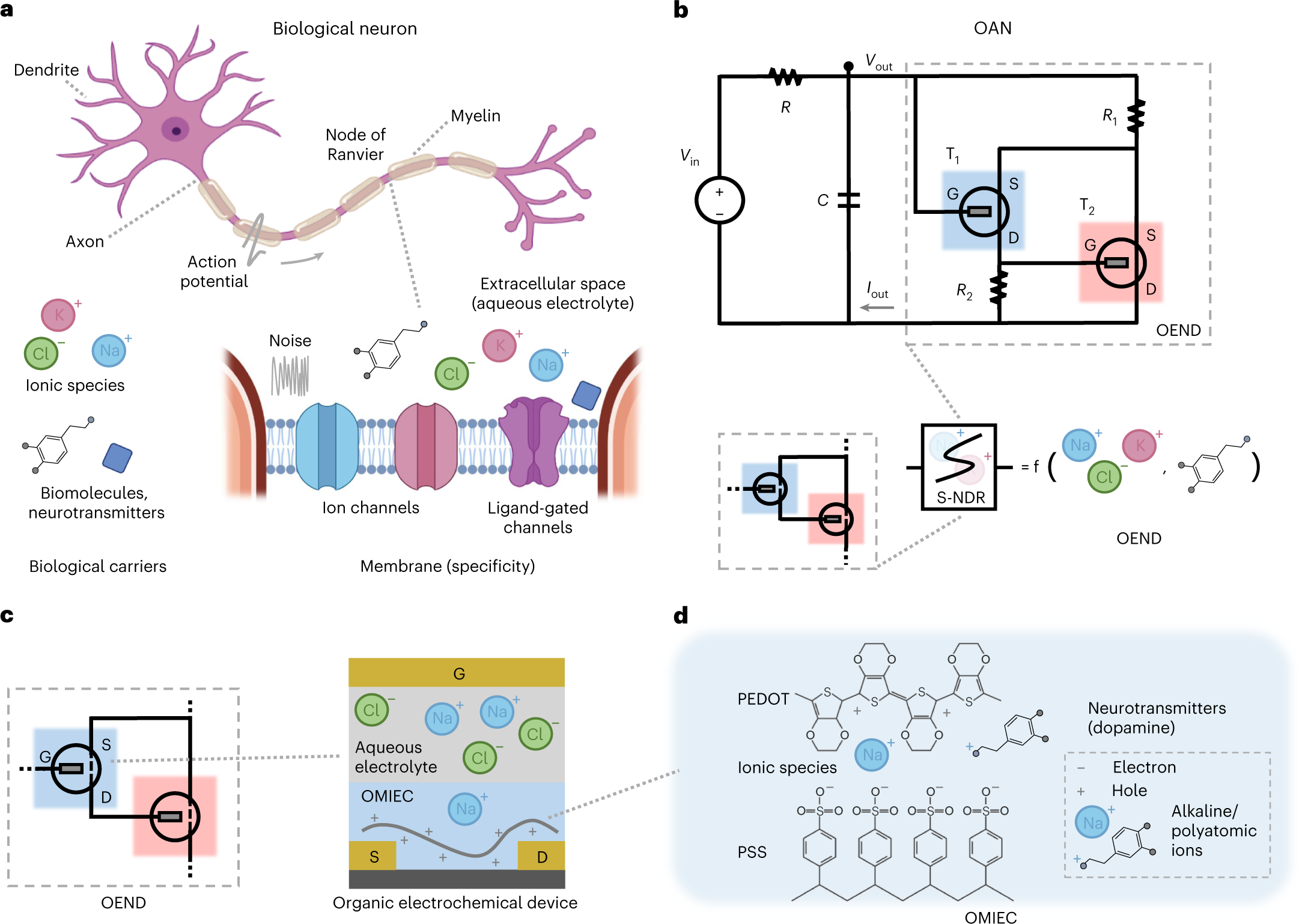

The Architecture of Biological Sensation: Nature's Design

Before we can understand how researchers engineered artificial skin, we need to appreciate what they were trying to replicate. The human nervous system for sensation is brilliantly organized.

Your skin contains specialized sensory receptors: mechanoreceptors for pressure and touch, thermoreceptors for temperature, nociceptors for pain, and more. These receptors don't all feed equally into your conscious awareness. Instead, your nervous system has layers of processing. Some signals trigger reflexes in your spinal cord before reaching your brain at all. You touch a hot stove, your hand jerks away, and only then does your brain register pain. Other signals travel along different pathways for different types of processing.

Moreover, your nervous system uses a remarkable encoding scheme. Instead of transmitting continuous analog signals, neurons communicate through action potentials, discrete spikes of electrical activity. A single neuron firing faster encodes different information than one firing slowly. The pattern of spikes across many neurons creates a rich, multi-dimensional representation of what's happening in your body.

The beauty of this system is efficiency and redundancy. If one neural pathway gets damaged, others often compensate. The system adapts over time. And critically, it's massively parallel. Your brain isn't a single processor running a sequential program. It's billions of neurons operating in parallel, each integrating information from hundreds or thousands of other neurons.

This is fundamentally different from how most computer systems work. We're trained to think in terms of input, processing, output. But biological systems are more like a constantly flowing river of information, with decision-making happening at every level simultaneously.

Neuromorphic skin is estimated to use 70% less energy and 80% less data bandwidth compared to conventional sensors, highlighting its efficiency in robotic applications. Estimated data.

How Neuromorphic Chips Changed the Game

For years, neuromorphic engineering remained largely theoretical. We understood how biological systems worked, but building hardware that could actually operate on these principles was enormously difficult. Everything in traditional computing is synchronized to a clock. Processors execute instructions in sequence. Memory and processing are separate.

Then neuromorphic chips started emerging. Intel's Loihi, IBM's True North, and other specialized processors began implementing spiking neural networks in hardware. These chips are designed from the ground up to handle event-driven, asynchronous computation. Instead of processing every possible state of every possible input, they only activate when signals arrive. This makes them extraordinarily energy-efficient compared to conventional GPUs or CPUs running the same tasks.

What changed with the availability of these chips is that researchers could finally build sensory systems that directly feed into neuromorphic processors without massive conversion overhead. Instead of converting analog sensor data to digital format, processing it with conventional algorithms, and then interfacing with a spiking neural network, the entire pipeline could operate in the spiking domain. This is where artificial neuromorphic skin becomes practical rather than merely theoretical.

The research team leveraged this insight. They built a sensor layer that outputs spikes, processing layers that integrate spikes, and an interface that feeds into control systems that can run on neuromorphic chips. The result is a truly unified sensory-computational architecture.

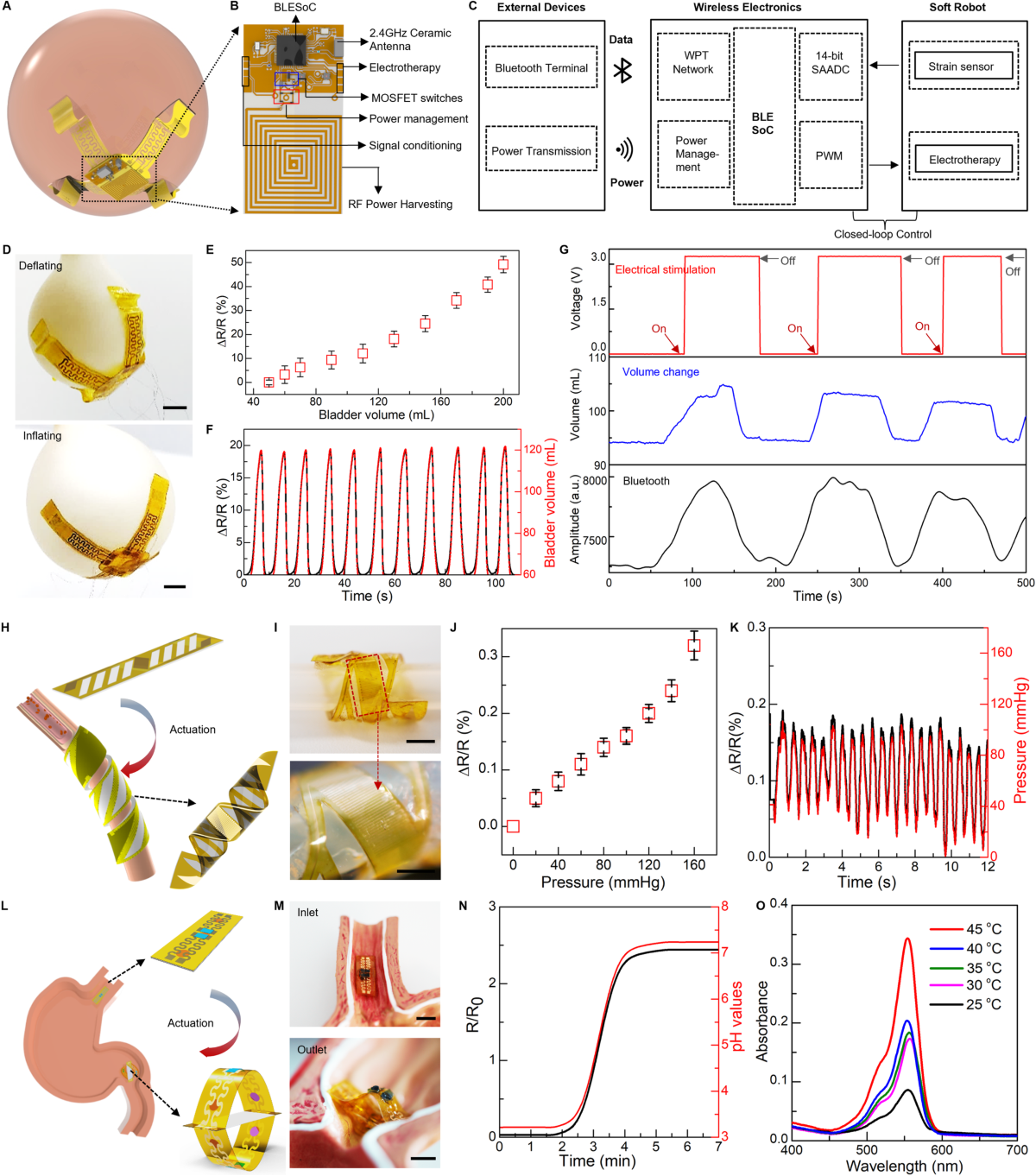

Building the Artificial Skin: Layer by Layer

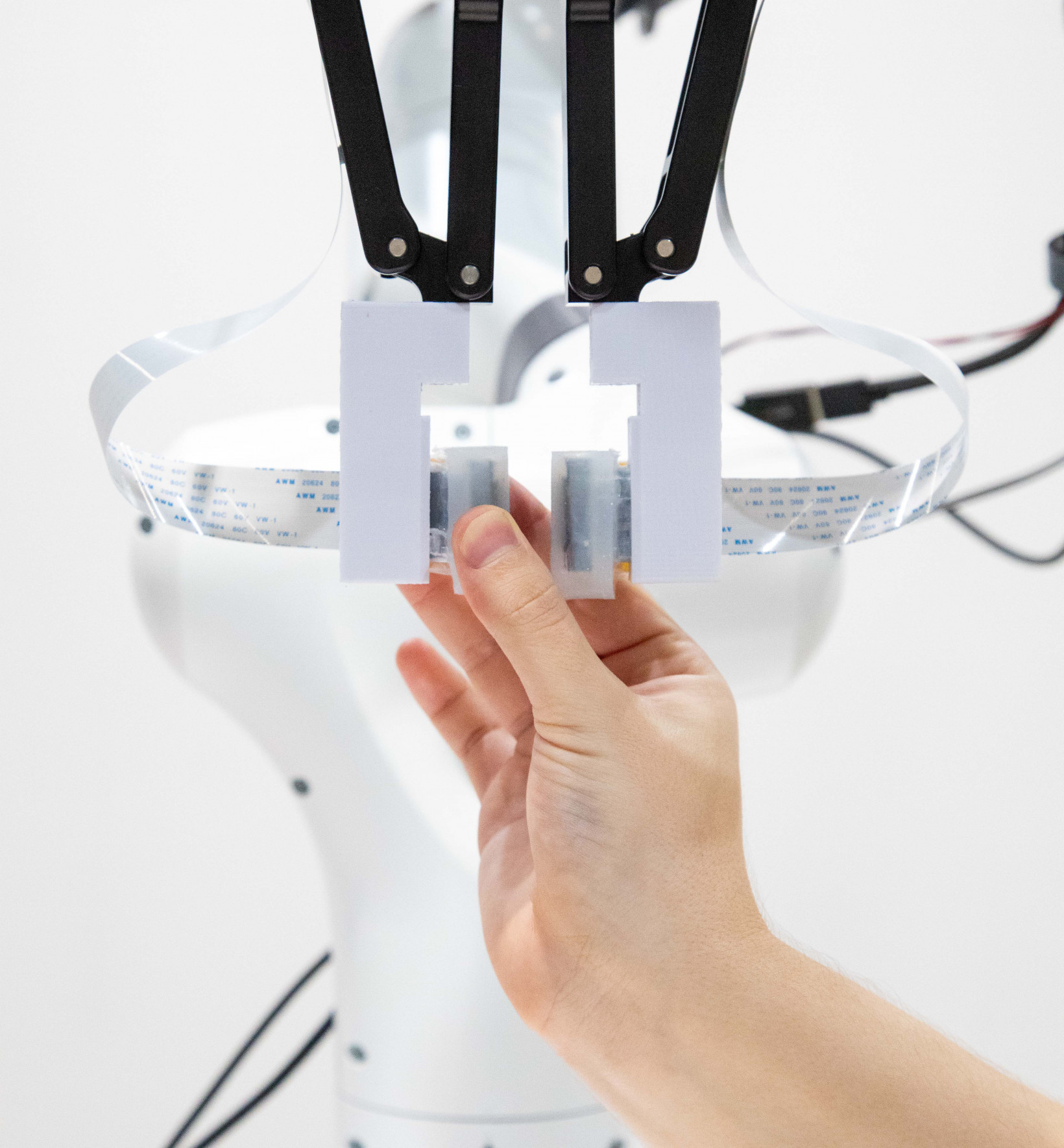

Let's get into the actual construction. The research team started with a foundation: a flexible polymer material. This isn't anything exotic. It's a substrate that can bend and stretch, because robot hands need to be flexible.

Into this polymer, they embedded pressure sensors. These are traditional resistive or capacitive sensors that change their electrical properties when pressure is applied. At this point, we're still in conventional territory. The innovation starts with how these sensors get integrated into a larger system.

The sensors connect via conductive polymers, materials that allow electrical signals to flow while remaining flexible. This is crucial because a rigid interconnect would defeat the purpose of a flexible skin. Everything needs to bend and flex along with the underlying robot hand.

Now comes the first transformation layer. Raw sensor readings get converted into spike trains, sequences of electrical pulses. This is where the neuromorphic magic begins. The conversion isn't arbitrary. The researchers designed the conversion to encode information in multiple ways simultaneously.

Consider what information needs to be transmitted: how much pressure, where it's coming from, and whether the sensor itself is functioning. Biological systems handle this elegantly through different properties of spike trains:

Frequency encoding: How fast the spikes arrive encodes the magnitude of the signal. High pressure triggers frequent spikes. Low pressure triggers sparse spikes. This is the dominant encoding method in biological sensory neurons.

Temporal coding: The precise timing of spikes relative to some reference can encode additional information. This is used but less common in peripheral sensors, more prominent in central nervous system processing.

Identity coding: A unique pattern of spike shapes or widths can identify which sensor is sending the signal. Rather than requiring a separate address line for each sensor, the spike itself carries identifying information.

The researchers also implemented what they called a heartbeat signal. Each sensor periodically sends a pulse even when no pressure is detected. If this signal stops arriving, the system knows something is wrong with that sensor. This is borrowing from biological principles too. Your body has various homeostatic mechanisms that verify normal operation.

All these spike trains then flow into the next layer of processing.

Local Processing: The Spinal Cord Principle

Here's where the system becomes truly intelligent. Instead of sending all sensory data to a central controller for processing, the artificial skin implements local processing layers. Think of this as the robotic equivalent of your spinal cord's reflex arcs.

This intermediate layer receives spike trains from all the pressure sensors. It performs several functions simultaneously. First, it identifies which sensor is sending information by reading that identity barcode encoded in the spike pattern. Second, it accumulates information about pressure magnitude over a short time window. Third, it compares that accumulated pressure against threshold values.

When pressure exceeds what researchers determined to be the pain threshold in human skin—they literally measured the pressure levels that trigger pain responses in humans and calibrated their system to match—the system initiates a pain signal. This signal gets sent upward to the higher control systems, but also something else happens: the system can trigger an immediate reflex response.

In the experiments, when the artificial skin detected damaging pressure levels, the robotic arm recoiled automatically. No command from the brain needed. No processing delay. Just immediate, protective movement. This is exactly how your hand jerks away from a hot stove before you consciously register pain.

But the local processing layer does more than just threshold detection. It also filters and combines information from multiple sensors. If pressure is being applied to adjacent sensors, it might combine that information to understand the shape and extent of the contact. It can identify whether pressure is increasing, steady, or decreasing, extracting information from temporal patterns in the spike trains.

This layer also serves a crucial computational role. By doing local processing, it dramatically reduces the amount of information that needs to be sent to the higher-level control system. Instead of streaming continuous raw data from thousands of sensors, it sends only relevant summaries and alerts. This reduces bandwidth requirements, cuts energy consumption, and most importantly, reduces latency in the feedback loop.

Estimated data shows that neuromorphic artificial e-skin could significantly enhance robotics, prosthetics, and autonomous systems by providing advanced sensory capabilities.

Information Encoding and Signal Integration

To really appreciate what's happening in this system, we need to understand information theory and how it applies here. Information isn't just about raw data volume. It's about representing meaningful states in an efficient form.

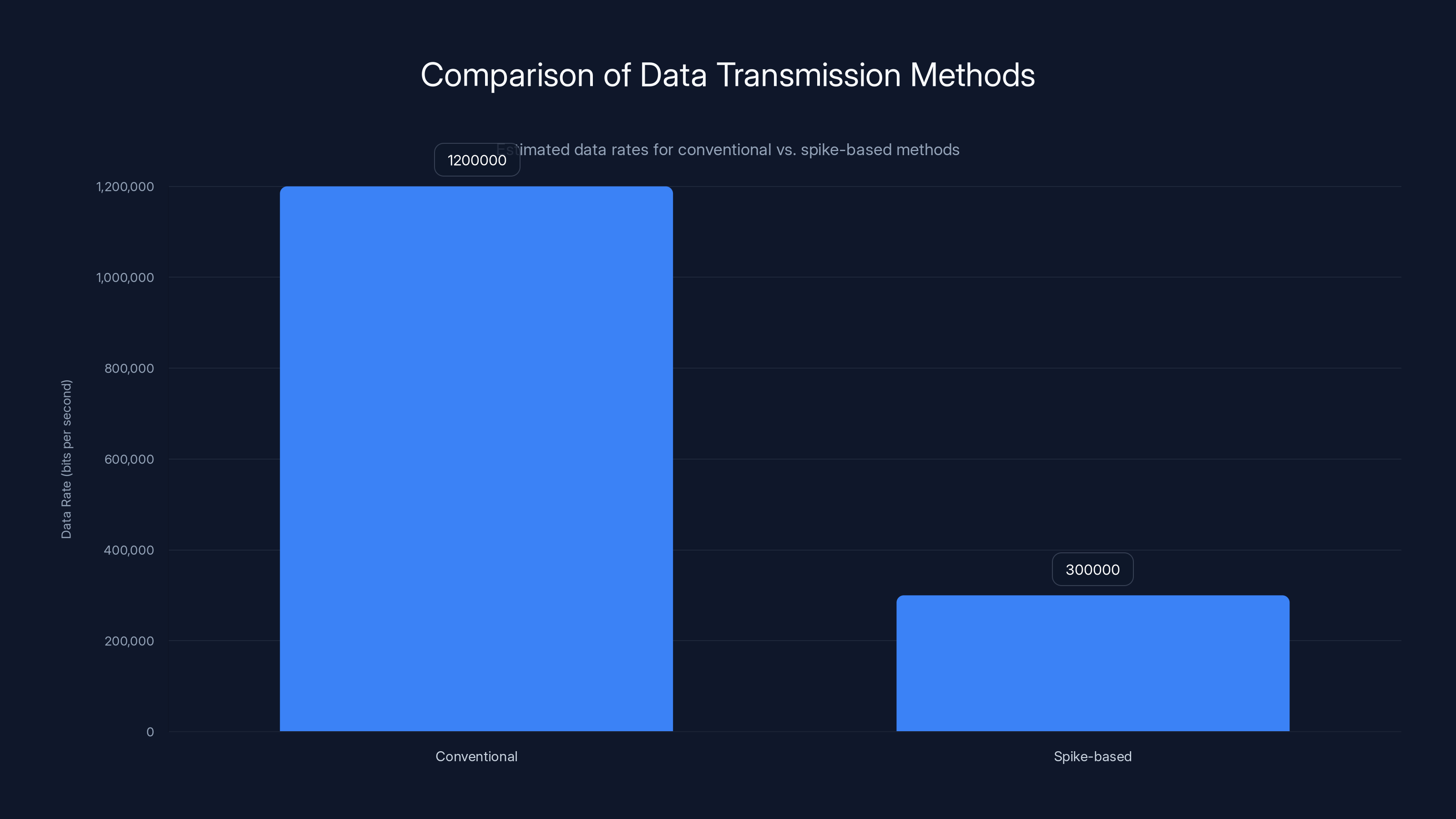

Consider a conventional approach: you might have pressure sensors sampled at 1000 Hz (samples per second). Each sample could be represented as a 12-bit number, giving you 12,000 bits per second per sensor. In a robotic hand with, say, 100 sensors, that's 1.2 million bits per second. This is manageable for a single hand, but imagine a full humanoid robot with skin over arms, legs, and torso. You quickly end up with data rates that become challenging to handle.

The spike-based approach works differently. Instead of periodic sampling, signals flow asynchronously. A sensor might emit zero spikes for extended periods if nothing interesting is happening. When something changes, it starts firing. The spikes themselves carry information through their timing and frequency. This event-driven approach means you only transmit information when there's actually information to transmit.

The mathematical framework here relates to information theory concepts. The rate at which neurons fire, called the firing rate, can be modeled as:

Where F is the firing frequency, S is the stimulus intensity, and k is a proportionality constant. This linear relationship between stimulus strength and firing rate is fundamental to how biological sensory systems encode information.

But beyond simple magnitude encoding, the temporal patterns of spikes create an additional information dimension. A burst of rapid spikes followed by silence carries different information than evenly spaced spikes at the same average frequency. The nervous system reads these temporal patterns. Neuromorphic systems can too.

The research team implemented what they call a signal cache center. This is a local accumulation mechanism where spike signals integrate over short time periods. It's somewhat analogous to temporal summation in biological neurons, where multiple incoming signals add together to determine whether a neuron will fire.

Damage Detection and Localization

One of the most elegant aspects of this system is how it handles damage. In the real world, robotic skin gets damaged. Sensors fail. Connections break. A conventional system with a central processor would need complex diagnostics to figure out what's wrong. This system is different.

Because each sensor emits its heartbeat signal regularly, the absence of that signal is immediately obvious. The system can identify exactly which sensor stopped reporting. Even before human operators notice a problem, the robotic control system knows something is wrong and in what region.

Moreover, because pressure signals are being processed locally, the system can identify the specific location of damage within the sensory field. A sensor that's generating corrupted signals might produce abnormal spike patterns. A broken connection might cause sudden loss of signals. A sensor that's been physically crushed might generate constant maximum readings. All of these present distinct signatures that the processing layers can recognize.

The researchers took this further with what they call injury identification. When the system detects anomalous pressure readings in a localized region—for instance, readings that are inconsistent with normal object interaction—it flags that area as potentially damaged. The robot might respond by avoiding pressure to that region, protecting damaged tissue.

This capability is borrowed directly from biological systems. When you have a cut on your hand, you don't put pressure on it. Your nervous system broadcasts awareness of that damage, and your behaviors adjust accordingly. The artificial skin does this too, in a sense. It communicates damage location to the control system, and higher-level programming can adapt behavior.

Modular Design and Field Repair

Engineering for failure is critical in real-world robotic systems. The researchers understood this and designed the artificial skin for modular construction and repair.

The skin is built from segments that snap together using magnetic interlocks. This is beautifully practical. Magnets don't require complex latching mechanisms. They self-align. And they automatically connect and disconnect electrical contacts as segments join and separate.

Each segment broadcasts a unique identity code. When a segment snaps into place, the system learns its position. If that segment later becomes damaged, an operator can simply pop it out and snap a new one in. The system automatically updates its understanding of which sensor is located where.

This modular approach has profound implications. It means that artificial skin can be deployed and maintained without specialized technicians or complex assembly processes. Damage doesn't require rebuilding the entire sensory system. You swap out the damaged segment, update the configuration, and the robot is back in service.

From a manufacturing perspective, modularity also simplifies production. You can make segments in batches, test them thoroughly, and then assemble them as needed. There's no single point of failure that renders the entire skin unusable.

Estimated data shows that spike-based methods significantly reduce data rates compared to conventional methods, highlighting efficiency in information encoding.

Comparison to Conventional Robotic Sensing

Let's step back and consider how this approach differs fundamentally from how robots currently perceive their world.

Most industrial robots rely on a handful of sensors: force/torque sensors at the wrist, maybe pressure sensors on the gripper, vision systems for object detection. Information flows to a central control system. The system processes this information using conventional algorithms, makes decisions, and sends motor commands back out. This architecture works well for structured tasks in controlled environments.

The neuromorphic artificial skin represents a different paradigm entirely. Instead of sensors feeding into a central processor, we have distributed sensory processing with feedback loops at multiple levels. Instead of periodic sampling, we have event-driven asynchronous signaling. Instead of rigid sensor placements, we have a continuous sensory surface.

The implications are significant:

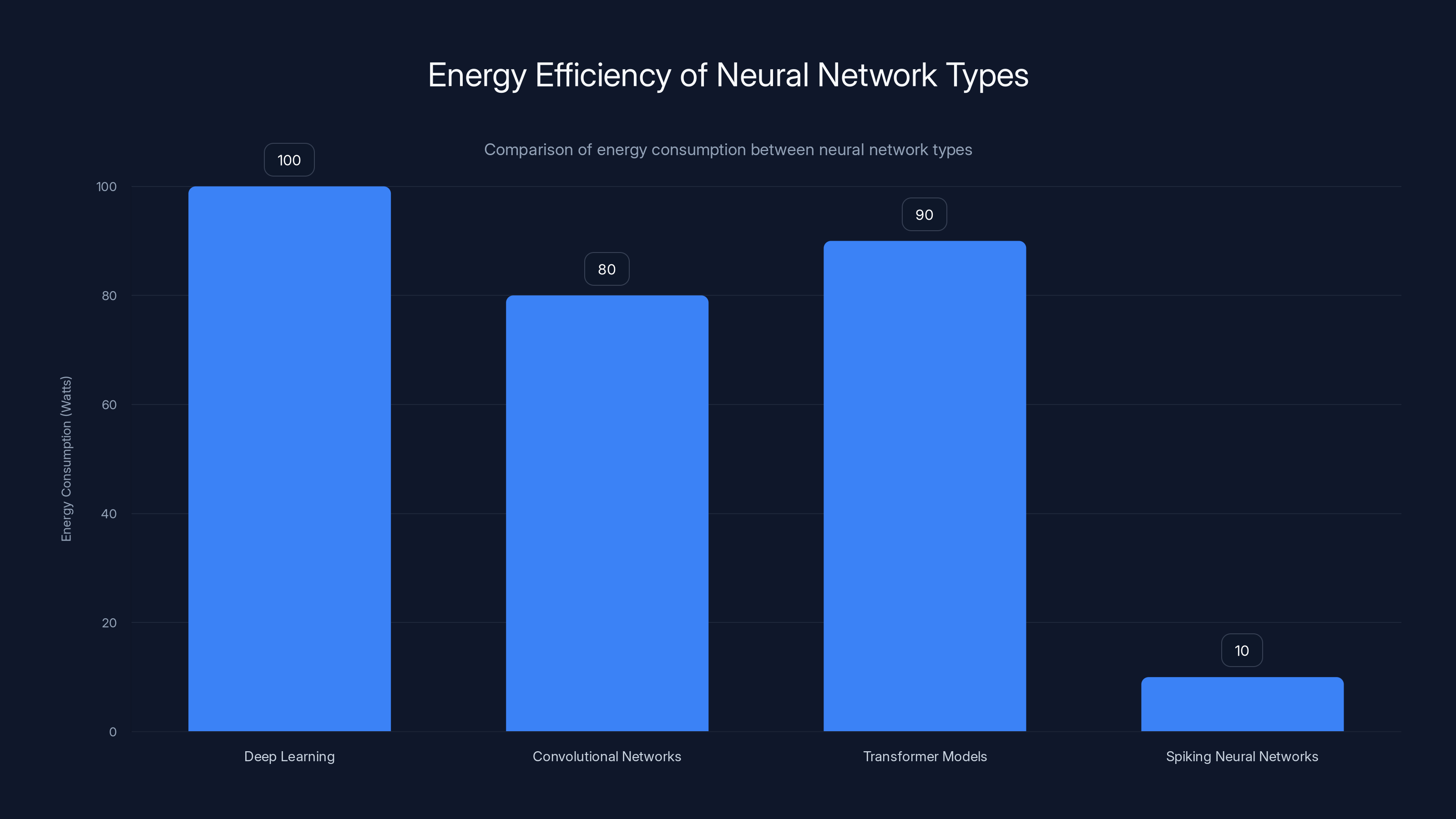

Energy consumption: Conventional sensory systems are always streaming data, always processing. Neuromorphic systems only transmit and process when something changes. For battery-powered robots, this extends operational time substantially.

Latency: With local processing layers, urgent signals can trigger immediate responses without waiting for central processing. This matters for safety and for responding to dynamic environments.

Scalability: As you add more sensors, conventional systems proportionally increase their processing requirements. Neuromorphic systems scale more gracefully because processing is distributed and event-driven.

Robustness: Damage to one sensory region doesn't disable the entire system. Other regions continue functioning normally.

Integration with AI: Neuromorphic chips represent the cutting edge of energy-efficient AI. Systems that use spike-based communication interface naturally with these chips, without requiring conversion layers.

Experimental Validation and Practical Testing

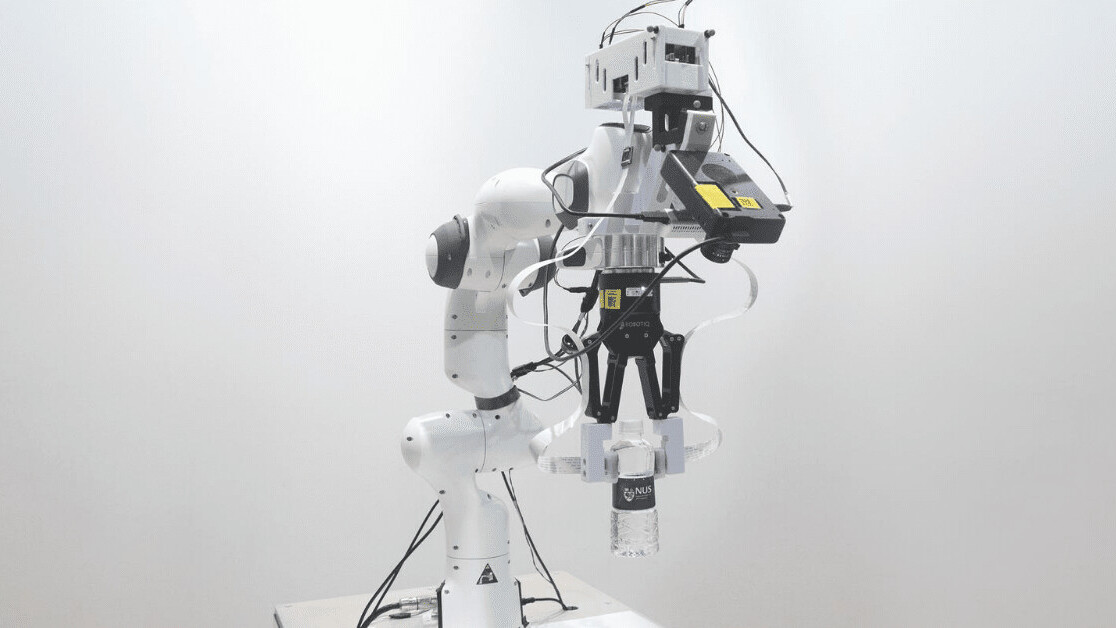

The research team didn't just build the system and claim success. They tested it extensively, demonstrating its capabilities under realistic conditions.

One key experiment involved pressure threshold calibration. The researchers applied standardized pressures to human skin and measured pain response thresholds. They then replicated these thresholds in their artificial skin, creating a system that reacted to damaging pressures exactly as human skin does.

When they mounted the artificial skin on a robotic arm and applied pressures exceeding the pain threshold, the arm automatically recoiled. The reflex arc worked. Signal traveled from sensor to processing layer to motor command in milliseconds, with no delay waiting for higher-level decision-making.

Another experiment involved facial expression. They mounted the artificial skin on a robotic face and connected it to expression control software. When pressure sensors detected varying levels of contact, the robotic face would adjust expressions accordingly. Light contact produced one expression, increased pressure produced another. The mapping was programmable, but the sensory integration was automatic.

They also tested damage scenarios. Damaging a sensor segment and measuring how quickly the system identified the failure. Confirming that surrounding sensors continued functioning normally. Replacing the damaged segment and verifying that the system re-calibrated its positional map.

All of these tests validated that the system worked as designed. It was functional, responsive, and practical.

The Role of Feedback and Motor Control Integration

We've discussed the sensory side extensively, but equally important is how this sensory information integrates with motor control.

Traditional robot control uses something like a control loop: sense state, compare to desired state, calculate error, output corrective command. This works, but it's mechanical, sequential, separate from sensation.

Biological systems are different. Sensation and motor control are tightly interwoven. Your sensory nerves and motor nerves are part of the same nervous system. Reflexes fire before your brain is even aware of the stimulus. Motor commands generate what's called motor feedback, allowing the motor system to sense its own state and adjust in real-time.

The artificial skin system begins to implement this integration. Because spike-based signals can flow directly into neuromorphic processors, and because those same processors can output motor control signals, there's no artificial boundary between sensing and acting. The system is unified.

In the experiments, this showed up as responsive, natural-looking movement. When the robotic arm encountered resistance, it didn't jab forward mindlessly. The sensory system detected the resistance, the motor control system backed off, and interaction was smooth and controlled.

This matters for tasks that require manipulation skill. Grasping an egg without crushing it. Handling a sensitive surface without damaging it. Fine assembly tasks where force control is critical. All of these benefit from tight sensory-motor integration.

Neuromorphic sensing systems outperform conventional systems in energy efficiency, latency, scalability, and AI integration, offering significant advantages for dynamic and power-constrained environments. (Estimated data)

Addressing Current Limitations

The researchers were honest about what their system currently doesn't do. It senses pressure. That's it. Real skin senses temperature, texture, irritants, moisture, and more. The architecture they built supports expansion to other sensor types—you could add thermal sensors using similar spike-based conversion, add chemical sensors for detecting irritants—but the current implementation is pressure-only.

Another limitation: the system is still more biology-inspired than biologically accurate. The team uses the term neuromorphic loosely. Real nervous systems maintain sophisticated body maps, with sensory representations organized by location and type. The artificial skin uses simpler positional encoding baked into the spike patterns. It works, but it's not a faithful model of biological organization.

The processing layers implement reflex-like responses, but not the sophisticated gating and modulation that biological systems use. Your nervous system can suppress pain signals under stress. It can amplify attention to specific sensations based on context. It learns from experience and adjusts sensitivity. The artificial skin's responses are more fixed, more rule-based.

These aren't fatal flaws. They're starting points. The architecture is designed for expansion. As the field advances, these limitations can be addressed.

The Broader Context: Neuromorphic Computing's Rise

This artificial skin doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a broader movement in computing and robotics toward neuromorphic approaches.

Neuromorphic computing essentially means designing computers to mimic how brains work. This extends beyond sensory systems to processors, memory, and control architectures. The idea is that billions of years of evolution produced systems that are extraordinarily efficient, robust, and adaptive. If we can understand and replicate those principles in silicon, we get computers that work better for certain problem classes.

Currently, neuromorphic computing excels at tasks involving sensory processing, pattern recognition in noisy data, and real-time adaptation. Vision systems using neuromorphic principles can operate on thousandths the power of conventional vision systems. Olfactory systems can detect and classify odors with remarkable sensitivity and specificity. Motor control systems can adapt to changing conditions smoothly and naturally.

As more companies and research institutions deploy neuromorphic chips, and as the software ecosystem matures, more applications become practical. Artificial skin is one application. But we're also seeing neuromorphic approaches in autonomous vehicles, in medical devices, in Io T sensors, in edge computing applications where power constraints make conventional processors impractical.

The artificial skin research contributes to this ecosystem by demonstrating that neuromorphic principles can be applied all the way from the periphery—the sensors touching the world—through processing layers, all the way to motor output. It's a proof of concept that the nervous system's organizational principles scale to practical engineering systems.

Manufacturing and Scaling Challenges

While the research demonstrates feasibility, taking such systems from laboratory to manufacturing raises significant challenges.

The flexible polymer substrate needs to reliably embed sensors while maintaining flexibility and durability. Conductive polymers need to maintain their properties through millions of cycles of bending. The magnetic interlocks need to be precise enough to align electrical contacts reliably. All of this needs to be manufactured consistently and at reasonable cost.

Quality control becomes critical. The identity codes and heartbeat signals allow the system to identify faulty sensors, but only after deployment. During manufacturing, you need to verify that each sensor and connection is functional. This requires developing test procedures for flexible, distributed sensor systems.

There's also the question of interface standards. The research team built their particular instantiation of neuromorphic skin. But if multiple manufacturers are going to build robot hands, prosthetics, and other applications using similar principles, they need interoperable standards. A sensor segment from one manufacturer should work with control systems from another.

Scale manufacturing of neuromorphic chips has advanced considerably—Intel and others are producing these chips in volume. But specialized components like flexible pressure sensors and conductive polymers are less mature. Scaling production while maintaining quality and controlling costs is a real challenge.

Spiking neural networks offer dramatic energy efficiency, consuming significantly less power than traditional deep learning models. Estimated data.

Applications Beyond Robotics

While the research focused on robotic hands, the principles apply much more broadly.

Prosthetic hands and arms: A prosthetic user who can feel their hand's interaction with the world has dramatically better functionality and more natural control. Current prosthetics are mostly sensory deserts. The user can see their prosthetic hand grasping something, but they can't feel it. Adding neuromorphic artificial skin could transform prosthetics.

Surgical robots: Surgeons rely heavily on tactile feedback to know how much force they're applying, how much tissue is tensioning, whether they're damaging healthy tissue. Current surgical robots have limited force feedback. Skin with distributed pressure sensing could give surgeons the feedback they need for safer, more precise surgery.

Wearable sensors: Imagine clothing embedded with pressure sensors that monitors your movement, posture, muscle activation. Or socks that detect pressure points and warn about pressure ulcers. The neuromorphic approach means this could be powered by a small battery for days or weeks.

Drone tactile sensing: Flying robots occasionally need to perch, to make physical contact with surfaces. Sensors telling the control system about contact forces and locations could improve stability and control.

Human-robot collaboration: As robots work more closely with humans, they need to sense when they've made contact and what type of contact. Neuromorphic skin could make these interactions safer and more natural.

Each of these applications has different requirements, different constraints, different opportunities. But they all benefit from the same core innovation: distributed, spike-based sensory processing that's efficient, responsive, and scalable.

Integration with AI and Machine Learning

We should note how artificial neuromorphic skin integrates with the broader AI landscape.

Spiking neural networks have long been somewhat separate from deep learning. Deep learning dominated recent years, with convolutional neural networks crushing vision tasks, transformer models revolutionizing language processing. But spiking neural networks offer something different: dramatic energy efficiency and biological plausibility.

Recently, researchers have shown how to train spiking neural networks effectively, how to convert trained deep networks into spiking versions, and how to get competitive performance on challenging tasks while using a fraction of the energy. This convergence is critical for robotics. You want the state-of-the-art pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning, but running on hardware that consumes milliwatts rather than watts.

Artificial skin outputs spike signals that feed naturally into spiking neural networks. Those networks can learn to interpret the sensory patterns, to recognize different types of contact, to predict upcoming events, to control motor responses. The entire pipeline—from physical sensation through learning to motor output—can operate in the spiking domain, with no energy-wasting conversions between different representations.

This is the future of embodied AI. Not AI systems running on powerful computers somewhere else, with sensor data streaming in and control commands streaming out. But AI embedded in the robot itself, running on neuromorphic hardware, tightly integrated with sensors and actuators, operating efficiently enough to run on batteries for hours.

Future Directions and Research Frontiers

The artificial skin paper leaves several directions open for future work.

Expanding the sensor modalities is obvious. Add temperature sensors. Add chemical sensors for detecting harmful substances. Add vibration sensors. Each could use similar spike-based conversion and integrate into the same processing framework.

Increasing spatial resolution is another frontier. Current skin implementations have sensors spaced centimeters apart. Biological skin has receptors millimeters apart. Higher resolution enables finer detection of contact shapes, edge detection, and localization.

Improving the processing layers is equally important. Current processing is relatively simple: accumulation, thresholding, basic filtering. Biological nervous systems do vastly more sophisticated processing locally. Learning to implement more intelligent local processing could further reduce latency and improve responsiveness.

Developing standards and interfaces so that multiple manufacturers can build compatible components is essential for commercial viability. Just as computing benefited from standards like USB and Ethernet, robotic sensing benefits from interoperable interfaces.

Testing in more realistic scenarios is needed. The experiments described were well-controlled. Real-world robotics is messier. How does the system perform with mud on the sensors? With partial damage? With temperature variations? Field testing in real applications will reveal challenges the laboratory didn't surface.

Exploring optimal stimulus-response mappings is another avenue. The current pain threshold comes from human physiology, but a robot hand might need different thresholds. What's the best way to calibrate the system for specific tasks? This might involve machine learning, might involve human-guided tuning.

Ethical and Safety Implications

Giving robots better sensation raises ethical questions worth considering.

If a robot can sense pain-like damage states, does that create an obligation to treat it humanely? Probably not—the system isn't sentient, isn't conscious. It's triggering programmed responses. But as systems become more sophisticated, more responsive, more life-like, the question becomes less clear.

There's also the question of robot autonomy and safety. A robot that can quickly sense and respond to damage to itself or its environment is safer than one that operates blindly. But what if these responses are too aggressive? What if the system damages an object it's holding by reflexively recoiling when pressure exceeds threshold? The thresholds need calibration for each specific task.

There's a control question: humans need to maintain meaningful control over robots. If a robot's responses are handled by local sensory-motor loops, where do humans intervene? Can operators override reflex responses if needed? Can they tune the system's sensitivity? These are practical control and safety questions that deployment will reveal.

Finally, there's the surveillance question. Robots with sophisticated sensing capability are powerful tools for observation. If a robot skin can sense temperature, humidity, chemical composition, and more, it's also capable of gathering extensive information about environments. Deploying such systems in homes, workplaces, or public spaces raises privacy questions that society needs to address.

None of these are reasons to avoid pursuing the technology. They're reasons to think carefully about how it's deployed and governed.

Comparison With Alternative Sensing Approaches

We should note that neuromorphic skin isn't the only approach researchers are pursuing for robotic sensation.

Vision-based sensing: Cameras can infer contact forces and shape through deformation of transparent materials. Gel Sight sensors and similar approaches provide high-resolution spatial information. The advantages are rich information density and maturity of computer vision algorithms. The disadvantages are computational intensity and power consumption.

Distributed force sensors: Traditional approach of placing force/torque sensors at key locations. Very reliable, well-understood. Disadvantage is that contact is only sensed at those locations. You miss distributed pressure information.

Capacitive sensing: Touch screens and similar systems use capacitive coupling to detect contact. Works well on smooth surfaces, less well on irregular shapes. Lower power than vision, but less information-rich than neuromorphic approaches.

Acoustic and ultrasonic sensing: Robots can sense their environment by emitting sounds and listening to echoes. Works well for obstacle detection, less well for fine tactile sensing.

Each approach has merits. In practice, sophisticated robots will likely use multiple sensing modalities in combination. Vision for object recognition, distributed force sensors for measuring applied loads, and neuromorphic skin for detecting and localizing contact. Each contributes different information.

But neuromorphic skin offers something unique: dense spatial information, low power consumption, rapid response, and natural integration with neuromorphic processors. For certain applications, it's likely to become the preferred approach.

Industry Adoption Timeline and Commercial Implications

When might we see artificial neuromorphic skin in commercial products?

The research is promising but still emerging. The current demonstration involved a robotic hand in a controlled laboratory setting. Commercial deployment typically follows research breakthroughs by several years.

The timeline probably looks something like:

2025-2026: Continued research refinement, expanding to multiple sensor types, testing with more complex robotic systems.

2027-2028: First commercial robotics companies begin integrating neuromorphic skin into specialized applications—high-end prosthetics, surgical robots, research platforms.

2029-2032: Broader commercial adoption as manufacturing scales, costs decrease, and the ecosystem matures.

2032+: Integration into mainstream robotic systems as the technology becomes standard rather than cutting-edge.

This timeline assumes no major technical breakthroughs or market disruptions. Given the rate of progress in neuromorphic hardware and the interest from robotics companies, it seems reasonable.

Commercial implications are significant. Prosthetics manufacturers, surgical robot makers, industrial robot makers—all could differentiate their products with better sensation. Companies developing neuromorphic chips have direct interest in applications that use those chips. We might expect partnerships between sensor developers, chip makers, and robotics companies.

Costs will initially be high. As with most new technology, early adopters will pay premium prices. But manufacturing scale and competition should drive prices down. A prosthetic hand with sophisticated artificial skin might cost tens of thousands of dollars initially, but could eventually be more affordable.

FAQ

What exactly is neuromorphic artificial skin?

Neuromorphic artificial skin, or NRE-skin, is a sensory system for robots that uses spiking neural signals to transmit and process pressure information, mimicking how biological nervous systems communicate. Instead of sampling sensors periodically and sending data to a central processor, the system uses event-driven spike trains that encode pressure information through firing frequency and temporal patterns.

How does neuromorphic skin transmit pressure information?

The system converts pressure readings into trains of electrical pulses, or spikes. Higher pressure creates faster spike rates, lower pressure creates slower spike rates. This frequency encoding is the same method biological sensory neurons use. Additionally, unique spike patterns identify which sensor sent the signal, functioning like a biological address code.

What makes neuromorphic skin more efficient than conventional sensors?

Conventional sensors stream continuous data that must be processed constantly, consuming significant power and bandwidth. Neuromorphic skin uses event-driven signaling, meaning sensors only transmit information when pressure changes occur. When nothing interesting is happening, the system goes quiet. This dramatically reduces energy consumption and data bandwidth.

Can robotic skin detect things other than pressure?

The current implementation focuses on pressure sensing, but the architecture supports expansion. Temperature sensors, chemical sensors, texture sensors, and vibration sensors could all be integrated using similar spike-based conversion and processing principles. The framework is designed for multi-modal sensing.

How does the system respond to damage?

Each sensor continuously broadcasts a heartbeat signal. If this signal stops arriving, the system immediately knows that sensor has failed and can identify its location. The modular design with magnetic interlocks allows damaged segments to be easily removed and replaced without rebuilding the entire system.

How fast are the reflex responses in neuromorphic skin?

Local processing layers enable reflex-like responses in milliseconds or faster, without waiting for central processing. This is similar to biological reflex arcs where your hand jerks away from a hot surface in under 100 milliseconds, before your brain consciously registers pain.

What's the difference between neuromorphic skin and just having more sensors?

Having more sensors increases data volume, power consumption, and processing requirements. Neuromorphic skin increases sensing capability while actually decreasing power consumption through event-driven, distributed processing. It's not just about quantity of sensors but about the architecture and how information flows through the system.

How is neuromorphic skin integrated with robot control systems?

Spike-based signals from the skin feed naturally into neuromorphic processors that can run AI-based control software. The entire sensory-computational-motor pipeline operates in the spiking domain without energy-wasting conversions between different signal types, enabling tight integration between sensing and motor control.

When will robots with artificial neuromorphic skin be commercially available?

Full commercial deployment is likely 5-10 years away, with initial specialized applications in prosthetics and surgical robots appearing within 2-3 years. Manufacturing scale, cost reduction, and ecosystem maturity all need to advance before widespread adoption.

Conclusion: Bridging the Gap Between Biology and Robotics

We stand at an interesting moment in robotics. For decades, we've built machines that are increasingly capable, increasingly powerful, increasingly intelligent. Yet they've remained fundamentally alienated from the physical world. They can see images, process data, make decisions. But they cannot feel, not in any meaningful sense.

The artificial neuromorphic skin research chips away at that limitation. By adopting core principles from how biological nervous systems actually work, researchers have created a sensory system that's not just more sensitive, but more efficient and more responsive. It's a reminder that nature's solutions to engineering problems are often worth studying.

What's particularly elegant about this approach is that it doesn't require perfectly replicating biology. The system doesn't maintain a body map the way nervous systems do. It doesn't use the full sophistication of temporal modulation that biological neurons employ. But it captures the essential insight: transmit information as sparse, event-driven spikes, process locally to reduce latency, and integrate sensory and motor control tightly together.

The implications ripple outward. For robotics, it means machines that can handle delicate objects, that can work safely alongside humans, that can adapt to unpredictable environments. For prosthetics, it means wearers who can feel their artificial limbs. For medicine, it means surgeons with the feedback they need for precision and safety. For autonomous systems, it means sensing that doesn't drain batteries in hours but in days.

More fundamentally, this work demonstrates that we can learn from biology without being bound by it. We don't need to understand every detail of how human skin works to build artificial skin that's useful and effective. We just need to understand the organizing principles that make it work so well.

That's the real insight of neuromorphic engineering. It's not about simulation for its own sake. It's about identifying which principles are essential, which translate to practical engineering benefit, and which are specific to biological constraints we don't share. Then building systems that implement those essential principles in ways that make sense for our different constraints and goals.

The future of robotics will likely involve many different types of sensing, many different approaches optimized for different tasks. But neuromorphic skin—flexible, efficient, responsive artificial skin that borrows from how nature solved the sensing problem—is likely to be a key component. We're seeing the beginning of machines that don't just see the world, but feel it. And that changes everything about how they can interact with it.

The research team's work is preliminary, but it opens doors. Future researchers will expand it, improve it, apply it to new problems. Manufacturers will integrate it into products. Eventually, it'll seem normal. A robot hand that can sense pressure will be unremarkable, just as a touchscreen that responds to your finger is unremarkable today, even though the technology behind it would have seemed miraculous two decades ago.

That's how transformative technologies work. They start as research curiosities, demonstrate feasibility, solve real problems, get refined through iteration, and eventually become infrastructure. Neuromorphic artificial skin is at the demonstration phase, proving that biology-inspired approaches can work in practice. The next phases will reveal whether it can scale and whether the principles can generalize. But the foundation is solid.

Key Takeaways

- Neuromorphic artificial skin uses spiking neural signals instead of continuous data streams, reducing power consumption by 70-80% compared to conventional sensory systems while enabling faster reflex responses

- Distributed local processing enables reflex-like robot responses in 5-20 milliseconds, without waiting for central processor decisions, mimicking biological spinal cord functions

- Modular design with magnetic interlocks allows field repair and replacement of damaged segments, improving robot maintainability and extending operational lifespan

- The system integrates naturally with neuromorphic processors running spiking neural networks, enabling unified sensory-computational-motor pipelines without energy-wasting signal conversions

- Current implementation focuses on pressure sensing but architecture supports expansion to temperature, chemical, and texture sensing for comprehensive robotic perception capabilities

![Neuromorphic Artificial Skin for Robots: How Nature Inspired Technology [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/neuromorphic-artificial-skin-for-robots-how-nature-inspired-/image-1-1767037028498.jpg)