Nex Gen, AMD's $850 Million Gamble: How a Startup Challenged Intel's Pentium Dominance [2025]

Something shifted in the semiconductor industry during the mid-1990s. While Intel seemed unstoppable with its Pentium line, a small California-based startup was quietly building something different. Nex Gen wasn't trying to copy Intel's architecture. It was building around it, using a completely different approach to execute the same x86 instruction set that the entire PC ecosystem depended on.

That decision, and the engineering brilliance behind it, eventually cost AMD nearly a billion dollars. Not because Nex Gen failed, but because it succeeded at something AMD desperately needed: proving that Intel's dominance wasn't inevitable.

This is the story of how a fabless chip designer with a radical idea forced one of tech's biggest players to make a pivotal acquisition. It's also the story of how that single deal reshaped the CPU market for the next decade, and why understanding Nex Gen matters if you want to understand why AMD exists as a serious processor competitor today.

TL; DR

- Nex Gen was founded in 1986 and pioneered an innovative RISC-based x86 implementation that outperformed Intel's direct CISC approach

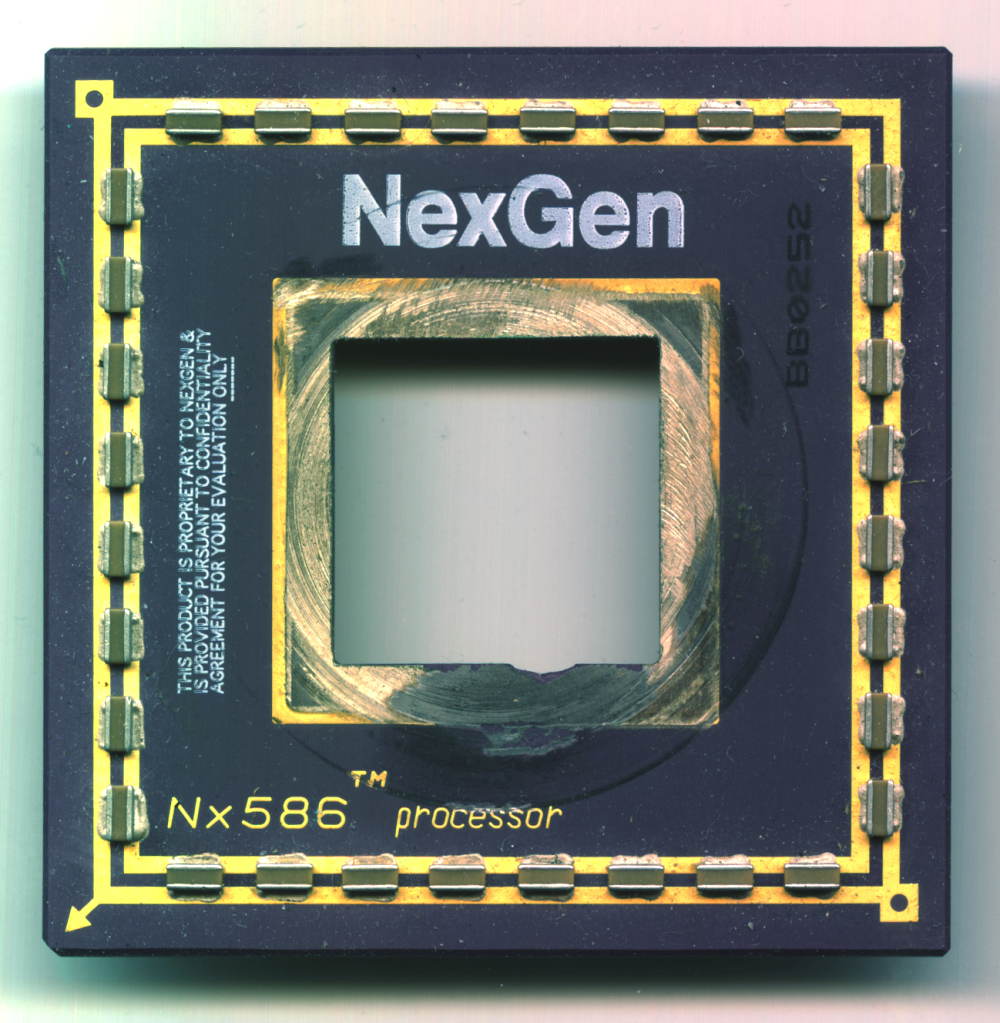

- The Nx 586 processor competed directly with Intel's Pentium line, achieving 75MHz performance without pin compatibility constraints

- AMD acquired Nex Gen for $850 million in 1995, seeing the company's superior design as the solution to its failed K5 product line

- The K6 processor (1997) drew heavily from Nex Gen's Nx 686 architecture, directly challenging Intel's Pentium Pro dominance with competitive performance at lower costs

- This acquisition marked a turning point in the CPU market, establishing AMD as a sustained competitor rather than a price-based alternative

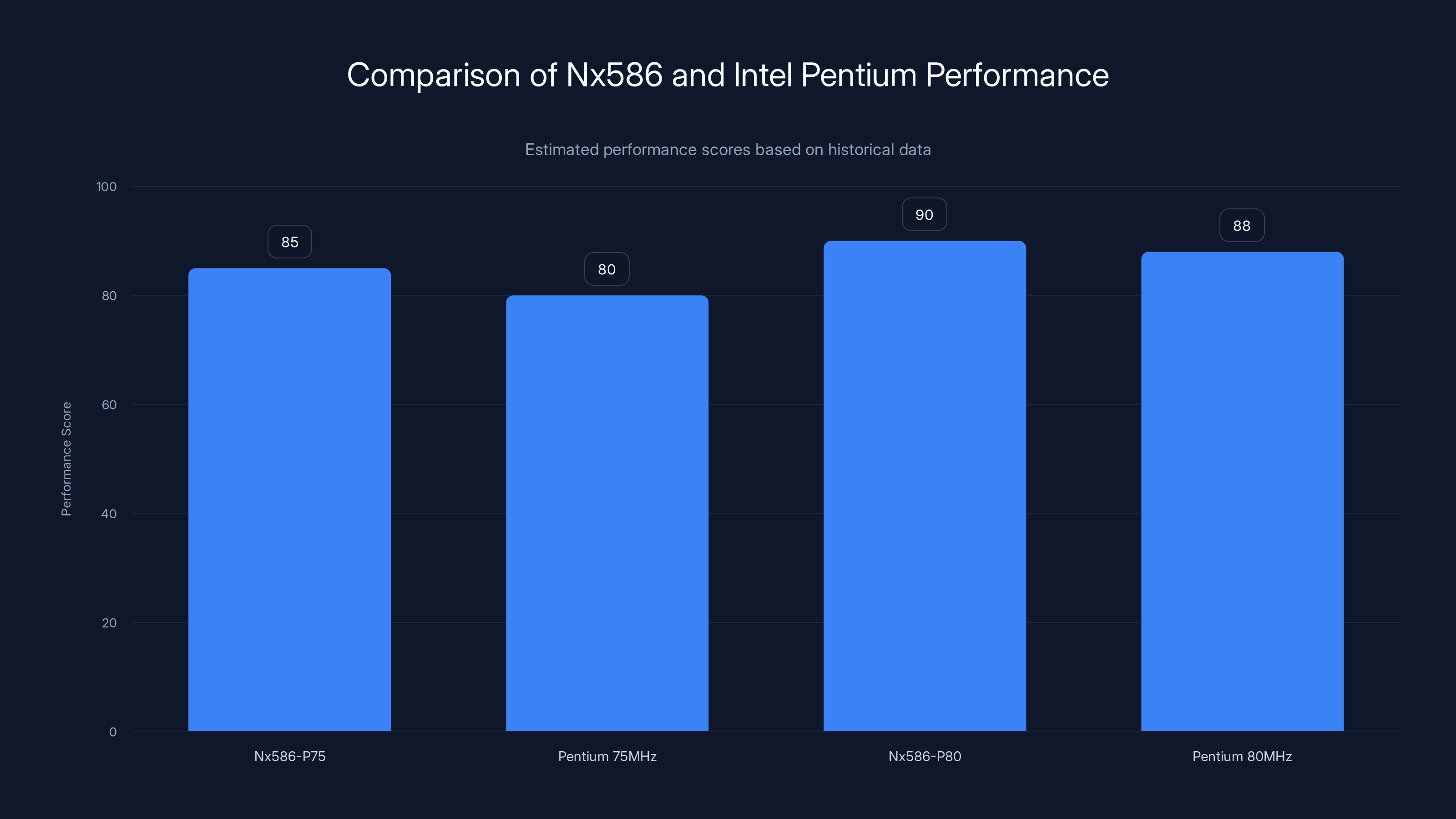

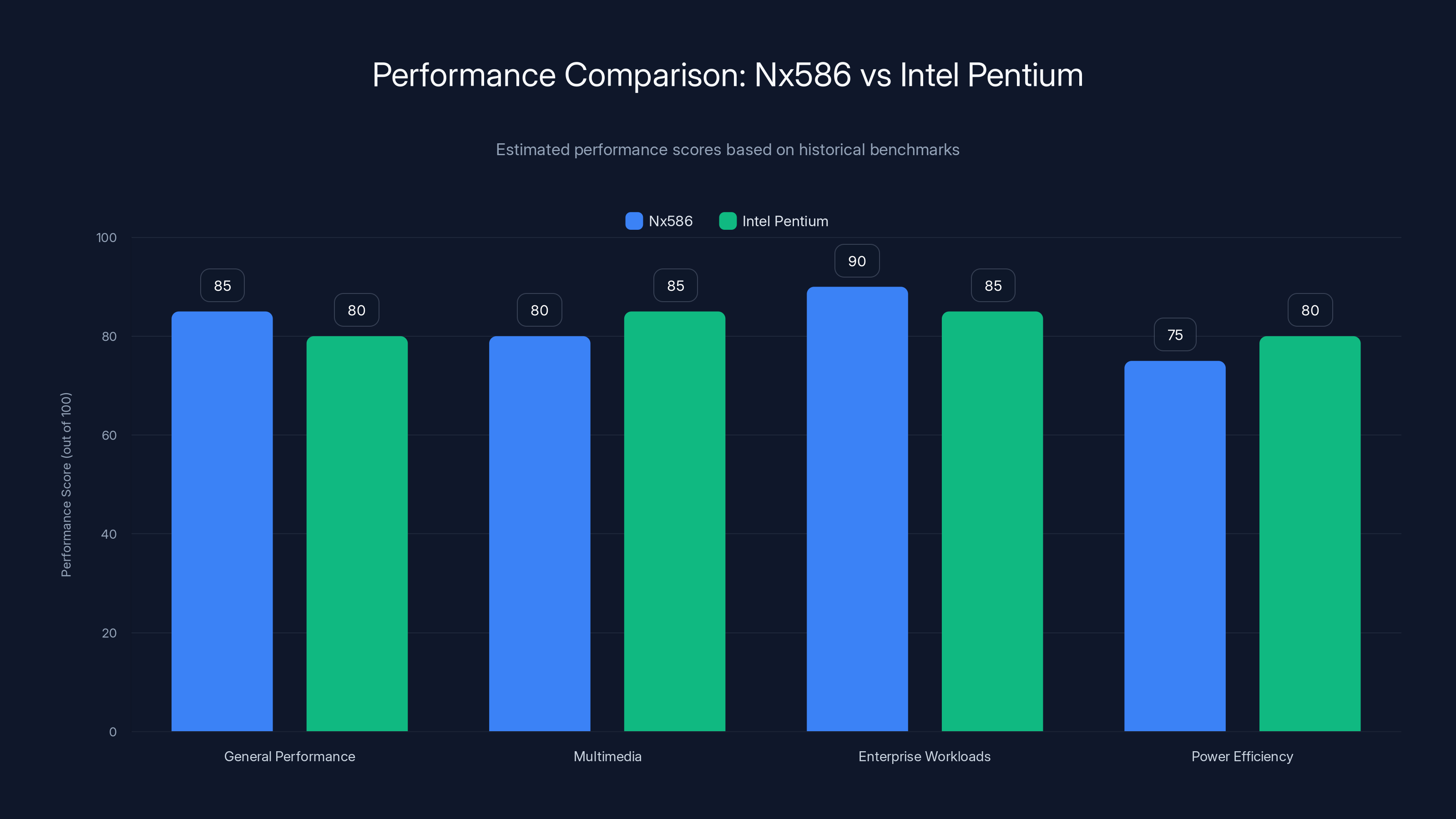

The Nx586 processors demonstrated competitive performance against Intel's Pentium line, showcasing the effectiveness of NexGen's RISC-based architecture. Estimated data.

The Silicon Valley Startup That Dared to Challenge Intel

When Nex Gen was founded in 1986, Intel's Pentium era hadn't even begun. The company was born during a transformative moment in computing, when the x86 architecture had become the de facto standard for personal computers, but the engineering approaches to implementing it were still being debated.

Thampy Thomas, Nex Gen's founder, had already proven he could build semiconductor companies. He'd previously co-founded Elxski, a California-based minicomputer manufacturer that had made waves in the industry. But Thomas saw something others missed: the x86 architecture was becoming locked in, but the ways you could execute it were wide open.

Nex Gen positioned itself as a fabless design house. This was crucial. The company wouldn't manufacture its own chips. Instead, it would design processors and contract manufacturing to companies like IBM's Microelectronics division in Vermont. This model meant lower overhead, faster iteration, and the ability to focus entirely on architectural innovation.

The company raised serious capital early on. Compaq invested heavily, as did ASCII (a Japanese conglomerate), and venture capital powerhouse Kleiner Perkins. These weren't random investors. They represented the entire ecosystem: a major PC manufacturer, an international technology firm, and some of the sharpest venture minds in Silicon Valley.

Their confidence in Nex Gen reflected something important: there was genuine belief that Intel's dominance could be challenged. Not through copying, but through architectural superiority.

The Revolutionary x86 Implementation That Nobody Expected

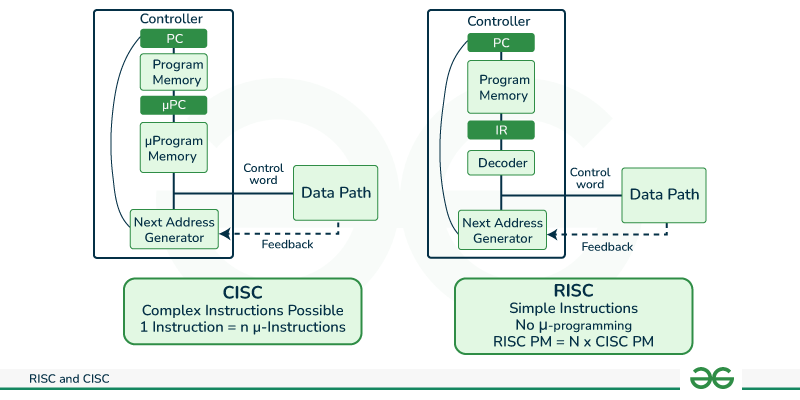

Here's where Nex Gen's engineering becomes genuinely fascinating. Every processor executes instructions, but the path from instruction to execution varies wildly. Intel's x86 implementation was based on CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computing). This meant complex instructions that did multiple operations in a single instruction cycle.

Nex Gen took a different approach entirely. The company built a RISC-based (Reduced Instruction Set Computing) core inside the processor. When x86 instructions arrived, the chip would translate them into simpler RISC operations, execute those on the internal RISC core, then return the results.

This sounds inefficient. It should have been slower. But Nex Gen's engineers understood something critical: modern processors spend most of their time on a few common operations. If you optimize the internal execution engine for simplicity and speed, and only pay a small penalty for translating complex instructions, you often win overall.

The result was counterintuitive. A processor that translated instructions was faster than one that executed them directly. This architectural insight became Nex Gen's most valuable intellectual property.

Compaq recognized the potential immediately. The company began integrating Nex Gen processors into some of its higher-end systems. This wasn't a mainstream success, but it proved something crucial: the architecture worked. It was competitive. It executed real-world code at speeds that challenged Intel.

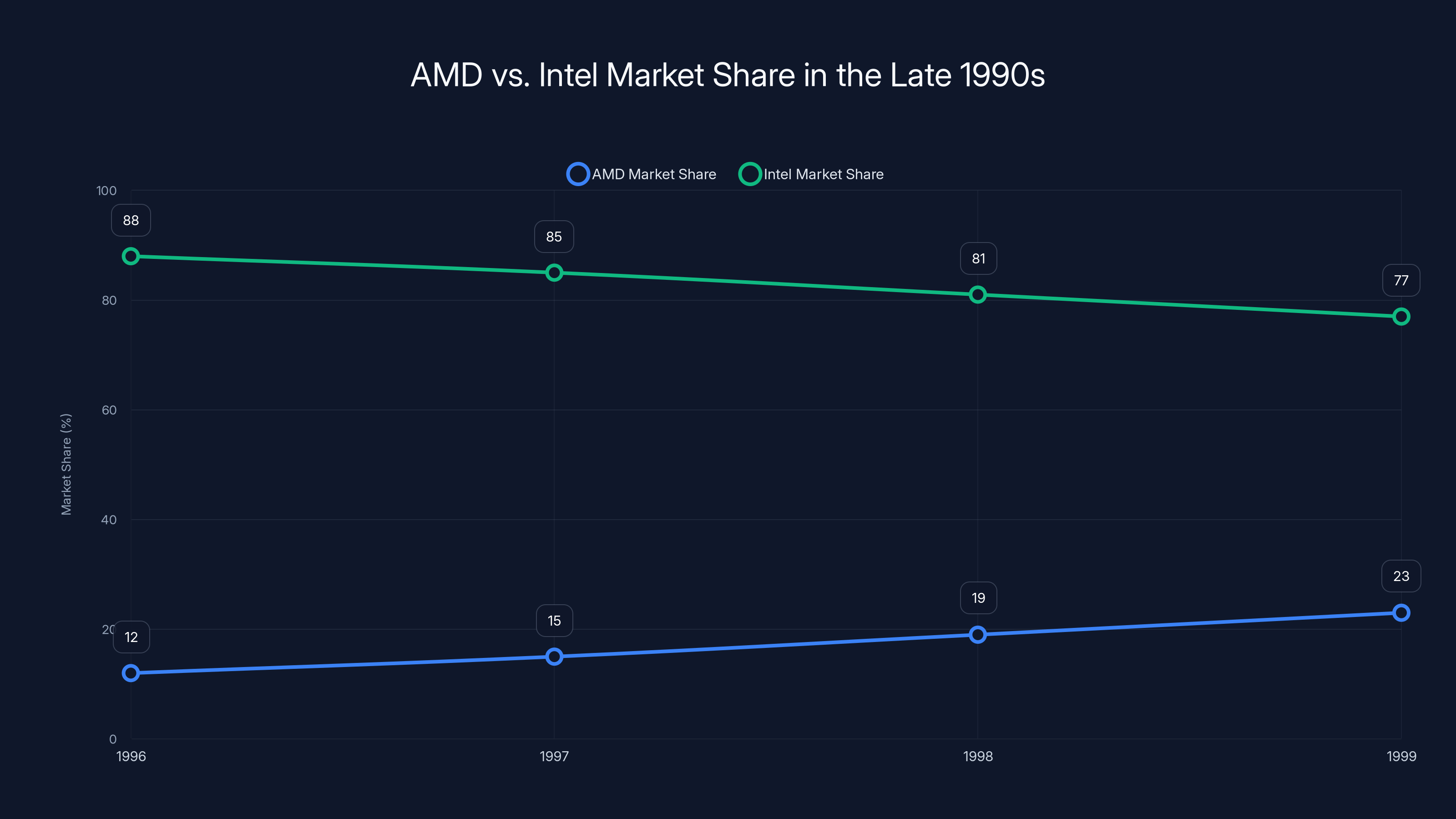

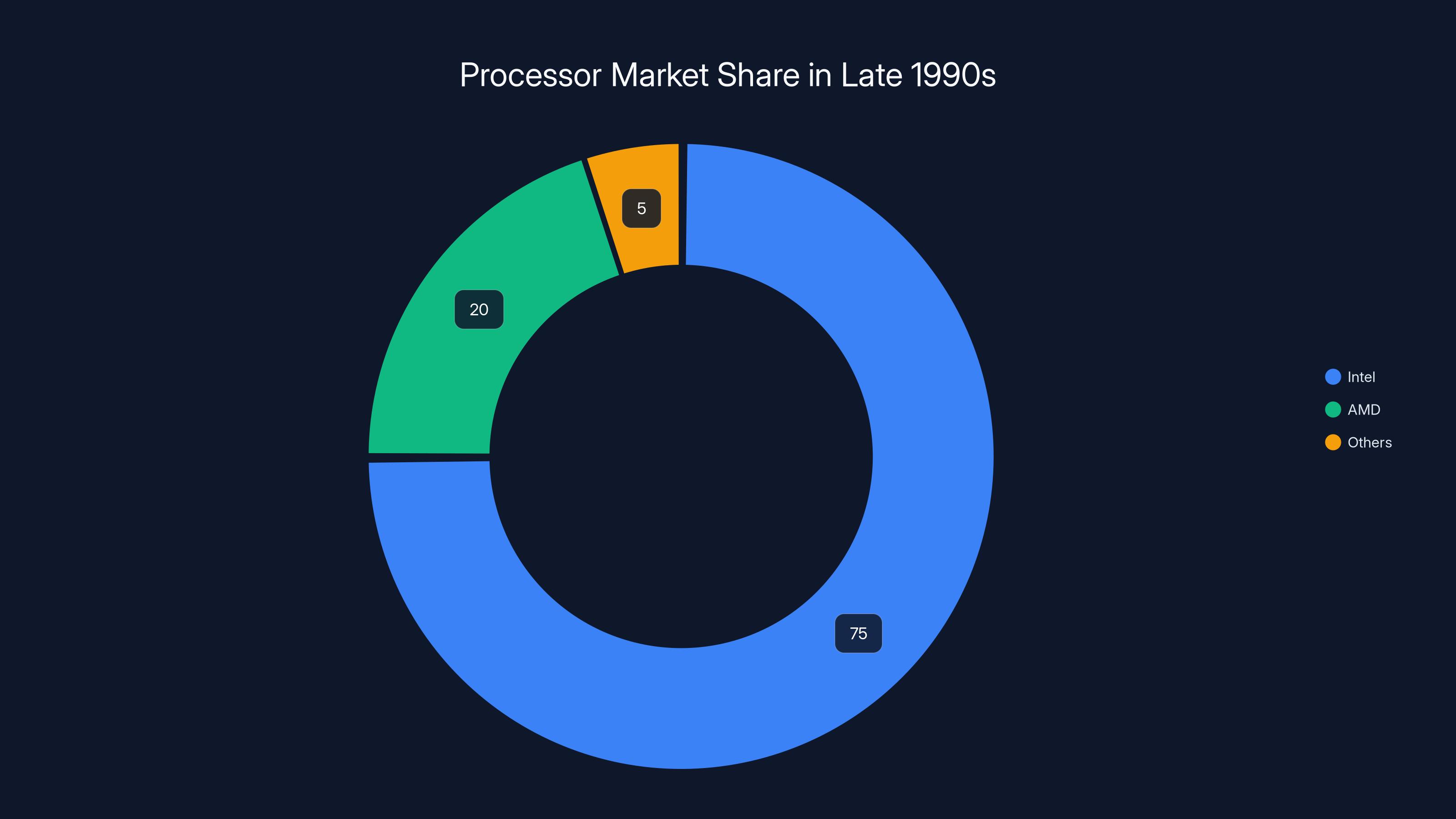

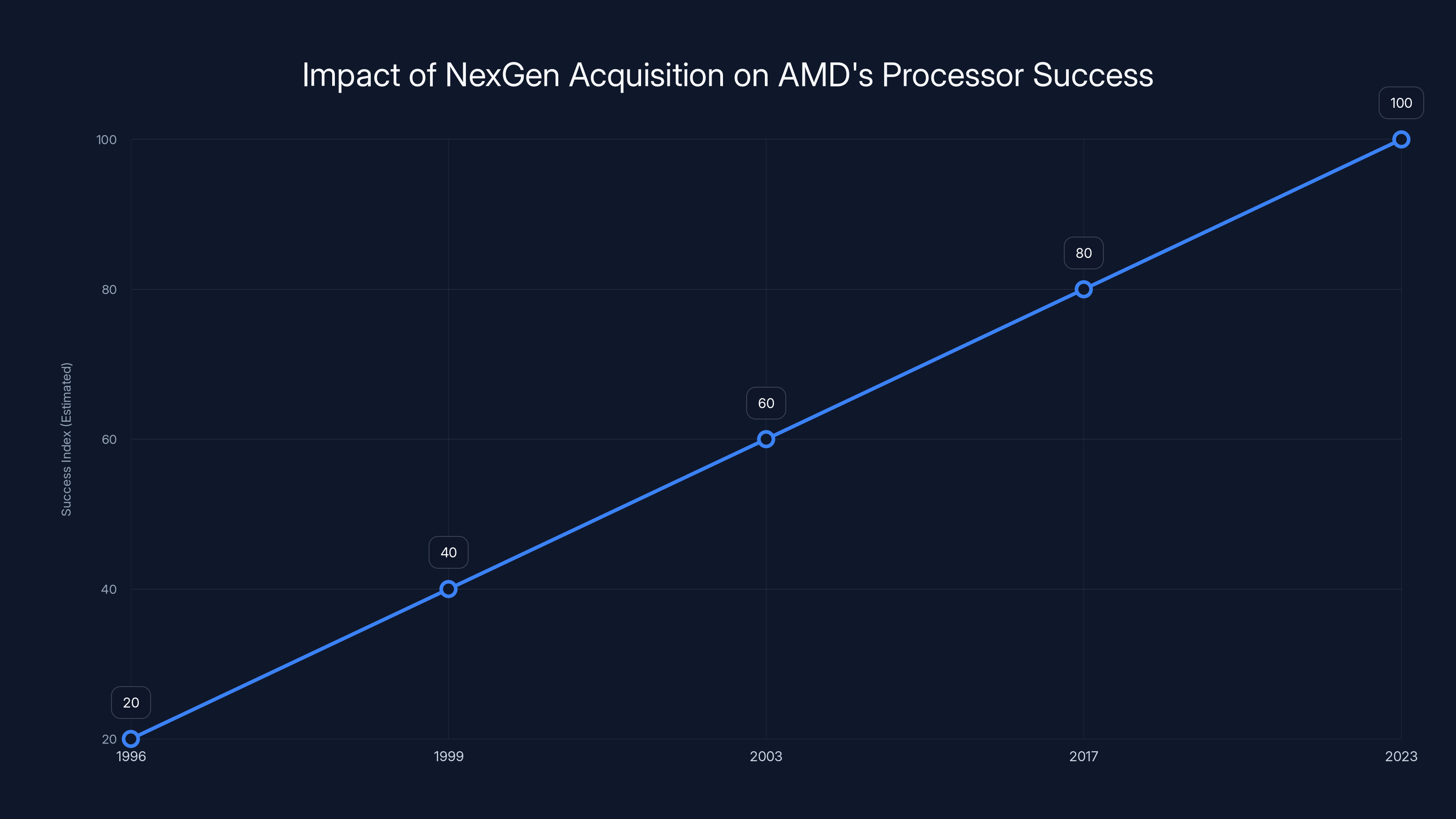

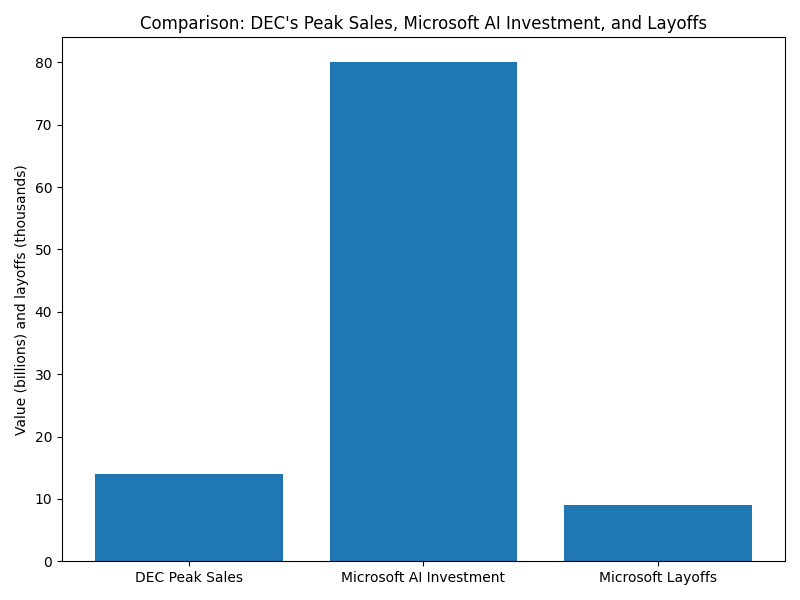

AMD's market share grew from 12% in 1996 to approximately 23% by 1999, challenging Intel's dominance. Estimated data.

The Nx 586: Toe-to-Toe with Intel's Pentium

Nex Gen's early efforts targeted Intel's 80286 and 80386 processors. These designs showed promise but struggled with production challenges. The company faced the classic startup problem: proving the technology in the lab was different from shipping it at scale.

But the company learned. By the time Nex Gen designed the Nx 586, the company had solved those manufacturing issues. This processor was built specifically to compete with Intel's Pentium line, which had launched in 1993 and dominated the market.

The Nx 586-P80 operated at 75MHz, placing it directly in competition with Pentium processors of similar speed. But here's the catch: the Nx 586 wasn't pin-compatible with Pentium systems. You couldn't drop an Nx 586 into an existing Pentium motherboard. It required custom motherboards and chipsets specifically designed for Nex Gen's architecture.

This was both a limitation and a strategic choice. Pin compatibility meant you were locked into existing socket designs. Custom architecture meant freedom, but also market friction. System builders would need to redesign around Nex Gen's specifications. For Compaq and a few other forward-thinking OEMs, this was worth doing. For the broader market, it created barriers.

Despite these constraints, the Nx 586's performance was genuinely impressive for its era. Benchmarks showed it competing effectively with the Pentium, and in some workloads, exceeding it. The RISC-based translation approach was proving itself in the real world.

Enterprise customers took notice. Compaq didn't just toy with Nex Gen processors. The company actually shipped systems with them in meaningful volume for enterprise computing. This validation was crucial. Nex Gen had proven it wasn't a lab curiosity. It was a viable alternative.

Why Intel Didn't Crush Nex Gen (And Why AMD Was Watching)

You might wonder why Intel simply didn't eliminate this threat through aggressive pricing or technology leaps. Intel certainly had the resources. But the market in the mid-1990s had more room for competition than it does today.

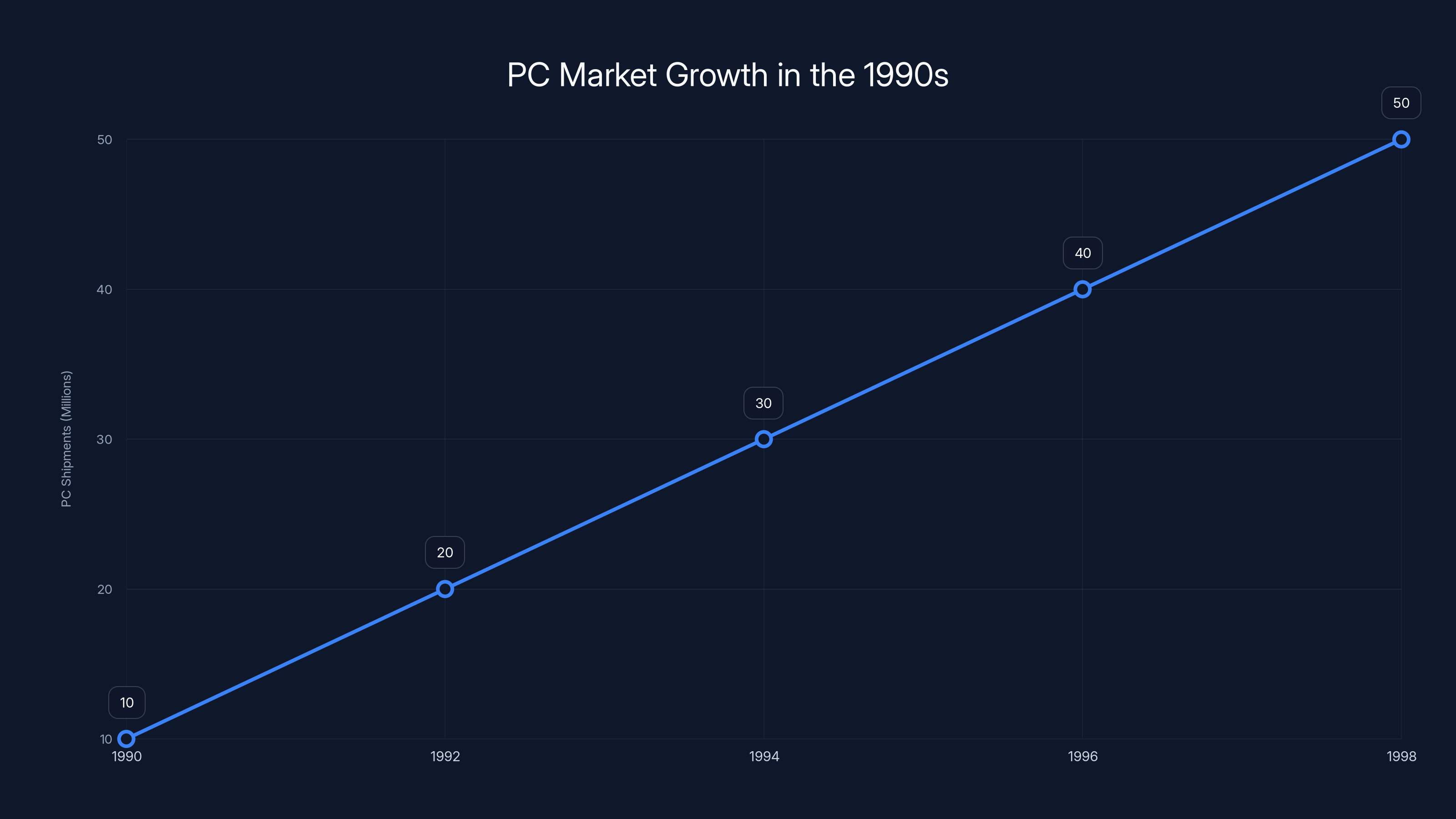

PC shipments were growing exponentially. The PC market went from roughly 10 million units annually in the early 1990s to over 50 million by the late 1990s. There was room for multiple processor vendors. AMD had built a successful business cloning Intel's architectures. Cyrix had carved out a budget segment. Nex Gen was targeting a different niche: innovative architecture with superior performance.

Intel's response was typical of market leaders facing disruption. The company improved the Pentium line incrementally. The Pentium Pro (launched 1995) pushed performance higher. But Intel didn't need to do anything radical because the market was big enough for multiple vendors to be profitable.

AMD, however, was in crisis. The company's K5 processor line, launched in 1995, had been a disaster. AMD had hoped to leapfrog Pentium performance through its own architectural innovations. Instead, the K5 suffered from poor performance, efficiency problems, and weak market reception. AMD's revenue was solid, but the company faced a fundamental problem: it had invested billions in a processor that wasn't competitive enough.

That's when AMD looked at Nex Gen and saw the answer. The company had the architectural innovation AMD needed. The engineering team had solved the problems. And the market was validating the approach.

But Nex Gen was running into its own constraints. Going public in 1994 brought capital, but public markets want growth and profitability. Nex Gen was technically impressive but still niche. The custom motherboard requirement limited market penetration. Manufacturing partnerships with IBM were solid but not unlimited in scale.

AMD's acquisition wasn't about desperation. It was about recognizing that integrating Nex Gen's architecture into AMD's own product line could solve multiple problems at once.

The $850 Million Bet: Why AMD Paid What It Paid

When AMD announced the acquisition in 1995, the price shocked the industry. $850 million for a fabless design company that hadn't achieved mainstream success? Some analysts questioned the move. Others saw it as brilliant.

To understand the price, you need to understand what AMD was actually buying. AMD wasn't buying revenue. Nex Gen's sales were modest. AMD was buying intellectual property: the RISC-based x86 core design, the architectural innovations, and the engineering team that created it.

More importantly, AMD was buying a solution to an urgent problem. The K5 had cost AMD billions. The company needed a hit in the processor market. Every quarter without a competitive high-end processor meant lost market share to Intel and lost revenue that competitors like Cyrix were capturing.

The $850 million figure reflected several factors:

The IP Value: Nex Gen's patents and core designs represented years of engineering work. Recreating that architecture internally would have taken AMD 3-5 years and hundreds of millions in R&D. Buying it upfront compressed the timeline dramatically.

The Talent Acquisition: Tech acquisitions are often talent grabs. Nex Gen's engineering team had proven they could innovate. Acquiring Nex Gen meant bringing that talent directly into AMD, fully trained in the architecture they'd built.

The Market Timing: The mid-1990s were when processor performance gaps mattered most. A company that could ship a competitive processor 12-18 months faster than developing one from scratch could capture significant market share. AMD was willing to pay a premium for speed.

The Risk Mitigation: This is the factor that's often overlooked. Building new processors is inherently risky. Some work, others fail. AMD was reducing risk by acquiring a design that had already been validated in the market. Compaq had tested it. The architecture worked. The remaining question was whether AMD could manufacture and market it profitably.

Looking back, $850 million proved to be one of the better acquisitions in semiconductor history. The return on that investment came quickly and lasted for years.

The PC market experienced exponential growth from the early to late 1990s, expanding from approximately 10 million units to over 50 million units annually. This growth created opportunities for multiple processor vendors. (Estimated data)

The K6 Processor: Nex Gen's Architecture Finds Its Audience

AMD immediately began integrating Nex Gen's architecture into its own processor roadmap. The company didn't just rebrand the Nx 686. It adapted the RISC core design, optimized it for AMD's manufacturing relationships, and built a new processor around it: the K6.

The K6 launched in 1997, and it fundamentally changed the processor market.

Where the Nx 586 had required custom motherboards, the K6 was designed for Socket 7, the same socket that hosted Pentium processors. This was a crucial decision. Suddenly, you could replace a Pentium in an existing system with a K6. No motherboard redesign. No custom chipsets. Just a drop-in upgrade.

The K6's performance was competitive with Intel's Pentium line and outpaced Intel's earlier Pentium Pro in many workloads. The initial versions clocked at 200MHz, with 233MHz versions launching later. For the time, this was genuinely competitive performance at prices AMD could undercut Intel on.

But the real victory was Market positioning. AMD could now say to PC builders: "Use our processor instead of Intel's. Same socket. Better price. Competitive performance." That's a far more compelling pitch than Nex Gen had ever been able to offer with its custom architecture requirement.

The K6 became a mainstream success. PC builders used it extensively. System integrators offered it as a cheaper alternative to Pentium systems. Consumer PC buyers could get K6-based machines at prices that undercut Pentium-based systems.

When Intel released the Pentium II in 1997, the K6 was already gaining market share. Intel's response was typical: they were faster, but more expensive. The market showed that many buyers preferred AMD's value proposition.

For the first time, AMD wasn't just surviving on being cheaper than Intel. The company was competitive on performance while remaining cheaper. That's the difference between a vendor and a competitor.

How Nex Gen's Acquisition Changed Semiconductor Strategy

The Nex Gen acquisition became a template for how large semiconductor companies should approach innovation. When a startup develops something genuinely innovative but faces market barriers, acquisition by a larger player isn't failure. It's the startup's most valuable outcome.

Nex Gen's investors, particularly Kleiner Perkins, had funded the company betting on acquisition. That's not surprising for venture capital, but it's important context. The plan was never to build Nex Gen into a $50 billion chip manufacturer. The plan was to prove the technology, get it to market validation, and then sell it to someone with manufacturing scale and market reach.

That strategy worked perfectly. Investors made substantial returns. The engineering team got to work on a much larger scale. And AMD got exactly what it needed: an architecture that could compete with Intel's best designs.

The acquisition also signaled something important to the semiconductor industry: good ideas get bought. If you can prove that your architectural approach is better, you don't need to match Intel's scale to succeed. You need to demonstrate advantage, and the acquirer will come to you.

Intel took note. The company began acquiring smaller semiconductor firms more aggressively. Intel acquired Advanced Silicon Technology (AST), which had designed the i740 graphics processor. The company acquired Altera, a major FPGA manufacturer. Intel understood that controlling cutting-edge technology sometimes meant acquiring the teams that designed it.

This pattern became foundational to how technology companies compete. You don't have to build everything yourself. If innovation happens elsewhere, acquisition becomes a valid strategy for integrating it into your product line.

The Technical Legacy: RISC vs. CISC Lives On

Nex Gen's most enduring contribution wasn't just the K6 processor. It was proving that RISC-based approaches to x86 execution could be superior to Intel's CISC implementations.

This insight influenced semiconductor design for decades. Intel eventually moved toward this approach with the P6 architecture (Pentium Pro), which incorporated RISC-like features. Modern processors from all manufacturers now use this hybrid approach: simple RISC-like instruction execution with a translation layer for complex instructions.

The irony is delicious. Intel built its empire on CISC complexity. Nex Gen proved you could get better performance by simplifying execution and translating complex instructions. Today, virtually every high-performance processor, regardless of manufacturer, uses variations of the approach Nex Gen pioneered.

AMD's subsequent processor lines, from the Athlon through the Ryzen series, incorporated and refined Nex Gen's architectural principles. The company never abandoned the core insight: simplify what happens every cycle, and you can make the whole system faster.

Intel, too, evolved its architecture toward this model. The company's modern x86 processors use extensive instruction translation and RISC-like internal execution. The Pentium 4, released in 2000, took this approach to extremes (with mixed results, but the strategy remained sound).

What Nex Gen proved was that chip design wasn't destiny. The x86 instruction set was fixed. But the ways to execute it were infinite. That realization is why, three decades later, both AMD and Intel are still finding ways to optimize the execution path.

During the late 1990s, AMD held an estimated 15-20% market share, challenging Intel's dominance. Estimated data.

AMD's K6 vs. Intel's Pentium: Market Reality in the Late 1990s

Once the K6 launched, the processor market became genuinely competitive for the first time since the 80386 era. This wasn't a situation where AMD merely offered budget alternatives. The K6 was fast. It was cheap. And it was reliable.

System Builder confidence in AMD increased dramatically. Companies like Gateway, Dell (in certain markets), and ASI built systems around K6 processors. These weren't budget lines. These were mainstream offerings.

Intel's response was measured. The Pentium II, launching in 1997, was faster than the K6 but at higher cost. Intel also controlled the OEM relationships and had better marketing. But for the first time, Intel couldn't just command the market. It had to compete.

Pricing pressure became real. Where Intel had maintained 50%+ gross margins on Pentium processors, the K6 forced the company to compress those margins. System builders could negotiate better pricing by threatening to switch to K6 systems.

This competitive pressure eventually benefited consumers, but it also affected both companies' profitability. Intel adapted by investing more heavily in marketing and brand development. AMD adapted by improving K6 derivatives and planning the next-generation Athlon processor.

The market dynamics proved durable. From 1997 through the early 2000s, AMD held 15-20% processor market share. This wasn't overwhelming Intel dominance. It was genuine competition.

When you trace this history forward, you can see how the AMD that exists today emerged from Nex Gen's acquisition. The company proved it could compete on architecture, not just price. That changed everything.

The Bigger Picture: Why Startup Innovation Matters in Semiconductors

Nex Gen's story illustrates something fundamental about technology innovation. The largest companies don't always innovate most aggressively. Sometimes they refine what exists. Sometimes they play defense.

Startups like Nex Gen can take bigger architectural risks because they don't have an existing product line to protect. Intel was committed to CISC approaches because the company had decades of architecture and manufacturing processes built around them. Changing fundamentally meant breaking compatibility, upsetting OEMs, and potentially obsoleting existing products.

Nex Gen had no such constraints. The company could experiment with RISC cores because it wasn't defending legacy x86 implementations. That freedom enabled genuine innovation.

This pattern repeats throughout tech history. The innovation often comes from the outsider with nothing to protect. The incumbent either ignores it (until it's too late) or acquires it (paying a premium for speed).

AMD chose acquisition. It was the right call. But the decision acknowledged something important: innovation sourcing matters. Sometimes the best processor architecture comes from a 200-person startup in California, not from a Fortune 500 company with 50,000 engineers.

That insight shaped how AMD approached its subsequent decades. The company would continue acquiring smaller firms with innovative technology (ATI Technologies for graphics, numerous smaller design firms). AMD understood that controlling cutting-edge innovation sometimes meant buying companies that had already found it.

Intel learned the same lesson, perhaps more slowly. The company's acquisition strategy evolved from reactive (buying things to block competitors) to proactive (buying innovation that could enhance existing products).

The Human Side: The Engineers Behind Nex Gen's Innovation

There's a tendency to discuss tech acquisitions in purely financial terms. Cost, return on investment, market share impact. But behind Nex Gen's architectural breakthrough were specific engineers with specific ideas.

Thampy Thomas, the founder, had previous startup experience. That mattered. He understood both the technical challenges of chip design and the business challenges of bringing products to market. This combination is rarer than you might think.

The engineering team that designed the Nx 586 and Nx 686 included people with deep x86 expertise. Some had worked at Intel and understood the instruction set from the inside. Others came from academia or smaller chip companies and brought fresh perspectives.

When AMD acquired Nex Gen, the company didn't just buy designs. It absorbed an engineering culture that was comfortable taking architectural risks. That culture influenced AMD's subsequent processor design. Teams that had proven they could question conventional wisdom about x86 architecture were suddenly part of the larger AMD organization.

This cultural integration was crucial. Some acquisitions fail because the acquired company's engineering approach conflicts with the acquirer's. But Nex Gen and AMD were aligned. Both wanted to beat Intel. Both believed that architectural innovation was the path to doing so.

The people who designed Nex Gen's processors went on to shape AMD's entire processor roadmap through the late 1990s and 2000s. Some moved into leadership roles. The influence of those acquired engineers rippled through the entire organization.

This is one reason why semiconductor acquisitions are often so valuable. You're not just buying designs that already exist. You're bringing in engineering thinking that shaped those designs. That thinking can transform the acquiring company's approach to future problems.

The acquisition of NexGen in 1996 marked a pivotal moment for AMD, leading to significant milestones such as the Athlon and Ryzen processors. Estimated data reflects AMD's increasing success in the processor market over the years.

The K6 Family: Evolution of Nex Gen's Architecture

AMD didn't just build one processor from Nex Gen's technology. The company extended the architecture across multiple generations and variations.

The original K6 at 200MHz and 233MHz was just the starting point. AMD quickly released K6-2, which added MMX instructions and improved the core design. The K6-2 was faster and more efficient than the original K6.

Then came the K6-III, which added on-die L2 cache. This was significant because it moved AMD closer to competing with Intel's Pentium II, which also had on-die cache. The K6-III represented a genuine evolution of Nex Gen's architecture, not just a minor refresh.

Each iteration improved manufacturing efficiency, increased clock speeds, and added features. By the time AMD moved to the Athlon processor (the spiritual successor to the K6 line), the company had refined Nex Gen's core architecture into something genuinely advanced.

This evolutionary approach is important for understanding why the acquisition was so valuable. Nex Gen's architecture wasn't a static design that AMD simply integrated. It was a foundation that AMD could build upon, improve, and evolve. The company had the manufacturing scale and engineering resources to take Nex Gen's innovation and push it further than Nex Gen could have independently.

It's the opposite of what happens when a large company acquires a startup and kills it. AMD integrated Nex Gen fully and let the architecture flourish. That decision paid dividends for years.

Market Share Battles: AMD vs. Intel in the Late 1990s

The K6's success translated into real market share. In 1996, AMD held roughly 12% of the x86 processor market. By 1998, that had grown to 18-20%. By 1999, AMD was challenging for 25% market share in some segments.

These numbers might not sound dramatic, but for context, AMD had been below 10% market share for years. The K6 represented genuine growth.

Intel's response was measured but effective. The company released the Celeron processor in 1998, targeting the budget segment that AMD had been exploiting. The Celeron competed aggressively on price while offering Pentium performance.

Intel also improved the Pentium II and released the Pentium III, maintaining performance leadership. But the key insight for Intel was that it couldn't ignore the budget and mainstream segments anymore. AMD had made these segments competitive.

System builders responded to this competition by playing vendors against each other. The days of just accepting Intel's pricing and supply were over. If AMD could provide competitive performance at better prices, OEMs would use AMD chips.

This dynamic persisted for over a decade. Intel held overall market share dominance, but AMD owned meaningful share and maintained profitability. Both companies could invest in R&D because both were making money.

The irony is that this competition probably benefited consumers more than any other period in PC history. Processor prices fell steadily. Performance improved rapidly. Choice existed. The market was genuinely competitive.

That competitive dynamic traces directly back to Nex Gen's acquisition. Without the K6, AMD likely would have faded as a processor vendor. Instead, AMD became a permanent fixture in the market.

The Ripple Effects: How Nex Gen Shaped Processor Markets Forward

Nex Gen's acquisition didn't just affect the immediate processor market. The decision rippled forward, influencing how semiconductor companies approach innovation for decades.

First, it established that architectural innovation could be acquired. Smaller companies could pursue radical architectural changes without needing to build manufacturing capacity or market presence. Success would be proven in the market, then acquired by larger players.

Second, it proved that x86 compatibility was a constraint, not a requirement. Nex Gen's initial custom architecture required new motherboards. The K6 solved this through Socket 7 compatibility. But it showed that you didn't need pin compatibility to succeed. Market timing and performance mattered more.

Third, it demonstrated that price-performance was a legitimate competitive axis. Intel had dominated through performance and brand. AMD, through the K6, showed that offering 95% of Intel's performance at 70% of the price was a winning strategy.

Fourth, it influenced how AMD built its company culture. The engineering teams that designed the Athlon, Opteron, and later Ryzen processors all inherited DNA from the Nex Gen acquisition. The idea that you could challenge Intel through clever architecture, not just manufacturing scale, became embedded in AMD's approach.

Fifth, it changed Intel's strategy. Intel eventually embraced acquisitions more aggressively. The company recognized that controlling innovation sometimes meant acquiring companies that had already achieved it. This led to Intel's acquisition of Altera (FPGAs), Habana Labs (AI accelerators), and numerous smaller firms.

The ripple effects continue today. AMD's current competitive position against Intel traces back to the company's architectural choices. Those choices can be traced back to the K6. The K6 can be traced back to Nex Gen.

The Nx586 showed competitive performance against Intel's Pentium, particularly excelling in enterprise workloads. (Estimated data)

Why This Matters Today: Lessons from a 30-Year-Old Acquisition

You might wonder why a 1995 acquisition still matters in 2025. The answer is that Nex Gen's story encodes fundamental lessons about technology, competition, and innovation that remain relevant.

Lesson One: Architectural innovation beats scale in the short run. Nex Gen was tiny compared to Intel. But the company's architectural insight provided competitive advantage. Scale and manufacturing capacity eventually matter. But clever architecture matters first.

Lesson Two: Timing matters enormously. Nex Gen launched when the PC market was growing exponentially. The company's custom motherboard requirement could have been fatal in a mature market. It was manageable when there were enough system builders willing to redesign. Timing makes or breaks innovations.

Lesson Three: Acquisition isn't failure for startups. Nex Gen was genuinely successful. The company proved its technology, attracted major customers, went public, and eventually sold at a premium. That's not failure. That's a successful outcome for a startup.

Lesson Four: Large companies need external innovation sources. AMD couldn't innovate fast enough internally to beat Intel's Pentium line. Acquiring Nex Gen compressed development time and brought proven technology into the company faster than internal R&D could.

Lesson Five: Sustained competition requires continuous investment. AMD didn't buy Nex Gen and coast. The company invested heavily in evolving the K6, creating the Athlon, and building future processors. Acquisition solved immediate problems but required sustained effort.

These lessons apply to modern technology challenges. Companies like Open AI, Anthropic, and others building AI systems face the same dynamics. Larger companies need their innovation. Acquisition becomes a natural outcome. The question for acquirers is whether they'll integrate the technology effectively or kill it.

The Evolution of Competition: From Nex Gen to AMD to Ryzen

Tracking the evolution from Nex Gen through modern AMD processors shows how architectural decisions compound over time.

Nex Gen's RISC-based x86 execution became the K6's foundation. The K6 evolved into the Athlon (which revolutionized performance-per-watt). The Athlon evolved into the Opteron (which brought AMD's architecture to servers). The Opteron evolved into modern Ryzen and EPYC processors.

Each generation refined the core insights that Nex Gen engineers had originally proven: that you could beat CISC complexity through intelligent RISC-based execution, that you could compete on performance without matching Intel's scale, and that architectural thinking could compound advantages over time.

Intel, for its part, moved in similar directions. The company's modern processors use instruction translation (similar to Nex Gen's approach), maintain multiple execution cores (similar to Athlon's approach), and focus on performance-per-watt (similar to AMD's emphasis).

The funny thing is that Intel probably could have developed these ideas internally. But Nex Gen proved them in the market first. That proof was valuable. It showed what worked and what didn't. It reduced risk for AMD's acquisition decision.

This dynamic is present in modern competition. The company that can learn from others' proven innovations, then execute better, often wins. AMD did exactly that with Nex Gen. That skill remains relevant.

The Competitive Landscape: Where We Are Now

In 2025, the processor market remains genuinely competitive. AMD holds roughly 20% market share in client CPUs and has been growing in server and data center markets. Intel has maintained dominance but has lost ground to AMD in recent years.

But the foundation of that competition traces back to decisions made in the 1990s. AMD's ability to compete at all came from acquiring Nex Gen and committing to architectural innovation. Intel's continued dominance comes partly from the company's own innovations but also from its eventual recognition that it needed to compete harder.

The companies are more balanced now than they were in the Pentium era. That balance is partially due to Nex Gen's acquisition. The startup's innovation forced AMD to become a real competitor and forced Intel to stop coasting.

Market competition drives innovation. Both companies are better because they have to compete. Consumers benefit through better processors, faster innovation, and lower prices.

Nex Gen's legacy is that competition itself. The startup didn't survive as an independent entity, but it created the conditions for sustained competition in the processor market.

The Value of Proven Technology: Why Acquisition Made Sense

When AMD paid $850 million for Nex Gen, critics questioned the decision. But financial analysis shows it was one of the best acquisitions in semiconductor history.

Consider the alternative: AMD could have tried to develop a competitive architecture internally. That would have cost billions, taken 5-7 years, and risked failure. Nex Gen had already proved the architecture worked. Compaq was already using it. The market had validated the approach.

So AMD's choice was:

Option A: Spend $850M to acquire proven technology immediately

Option B: Spend $3-5B over 5-7 years to develop competitive technology with significant risk of failure

Option A was obviously better. It compressed the timeline, reduced risk, and brought proven technology into AMD's portfolio immediately.

The K6's market success proved the acquisition logic sound. The processor generated billions in revenue for AMD. The profit from K6 sales alone likely exceeded the acquisition cost within 3-4 years. From that point on, the acquisition was essentially free. Every dollar earned from K6 and its descendants was pure benefit.

This financial math is important context for understanding why large technology companies acquire startups. It's not always about eliminating competitors. Sometimes it's about buying proven technology faster than you could develop it internally.

Nex Gen's acquisition became a template. When Qualcomm wanted to compete in mobile processors, the company acquired ARM architectural licenses and later acquired specific processor designs. When Nvidia wanted to compete in mobile processors, the company acquired Nvidia Tegra technology through various acquisitions.

The pattern is consistent: large companies acquire proven innovations to accelerate time to market and reduce development risk. Nex Gen was an early example of this pattern becoming standard practice.

FAQ

What was Nex Gen and why did it matter?

Nex Gen was a California-based fabless chip designer founded in 1986 that pioneered an innovative RISC-based approach to executing x86 instructions. The company's Nx 586 processor competed directly with Intel's Pentium line and proved that architectural innovation could challenge Intel's dominance. It mattered because it demonstrated that you didn't need to copy Intel's architecture to compete. You could design something fundamentally different and still be competitive or superior.

Why did AMD acquire Nex Gen for $850 million?

AMD acquired Nex Gen because the company's K5 processor had failed to compete effectively against Intel's Pentium. The acquisition provided AMD with proven x86 architecture that had already been validated in the market (Compaq was using it). Rather than spending years developing competitive technology internally with high risk of failure, AMD could acquire Nex Gen's proven architecture immediately and integrate it into the K6 processor, which launched in 1997 and became hugely successful.

How did Nex Gen's architecture differ from Intel's approach?

Nex Gen used a RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computing) core to execute x86 instructions, rather than directly executing the complex CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computing) x86 instructions like Intel did. Nex Gen's processors translated x86 instructions into simpler RISC operations that executed on an optimized internal core. This approach was counterintuitively faster because the simple RISC execution could be optimized more effectively, and the translation overhead was minimal. This same principle influenced chip design for decades and is still used in modern processors.

What was the Nx 586 processor and how did it perform?

The Nx 586 was Nex Gen's main processor design that competed with Intel's Pentium line. Operating at 75MHz, the Nx 586-P80 delivered performance competitive with Pentium processors at similar speeds. However, unlike other Intel competitors like AMD and Cyrix processors that were pin-compatible with Pentium systems, the Nx 586 required custom motherboards and chipsets. This compatibility requirement limited mainstream adoption, though Compaq and other enterprise customers did adopt it. The processor proved the viability of Nex Gen's architectural approach.

How successful was the K6 processor that AMD created from Nex Gen's technology?

The K6 was hugely successful and became a mainstream processor throughout the late 1990s. Launching in 1997 at 200MHz with 233MHz versions following, the K6 was Socket 7 compatible, meaning it could replace Pentium processors in existing systems without requiring new motherboards. The K6 delivered competitive performance at significantly lower prices than Intel's Pentium line. AMD's market share grew from around 12% to 18-20% during the K6 era, establishing AMD as a genuine competitor rather than just a budget alternative. System builders like Gateway and Dell offered K6-based systems to mainstream customers.

What was the long-term impact of the Nex Gen acquisition on AMD?

The acquisition fundamentally transformed AMD from a company that competed primarily on price to one that could compete on architecture and innovation. The engineering teams that designed Nex Gen's processors influenced AMD's entire processor roadmap for decades, including the successful Athlon, Opteron, and modern Ryzen processors. The K6 and its successors generated billions in revenue, and the profit from these processors exceeded the acquisition cost within just 3-4 years. More broadly, the acquisition established that AMD could compete seriously with Intel on performance, fundamentally changing market dynamics and benefiting consumers through competition, lower prices, and faster innovation.

Why didn't Intel simply crush Nex Gen as a threat?

The PC market in the mid-1990s was growing explosively (roughly 10 million units annually in the early 1990s growing to 50 million by the late 1990s), providing room for multiple profitable processor vendors. Intel focused on technology leadership and premium market segments, while Nex Gen carved out space in performance-conscious systems and later through AMD's K6 in the mainstream market. Intel's strategy of incremental improvement worked because the market was large enough for both companies to be profitable. It wasn't until much later that consolidation and market saturation forced more aggressive competition.

How did Nex Gen's acquisition influence how large tech companies approach innovation?

The Nex Gen acquisition established acquisition strategy as a legitimate way for large companies to obtain cutting-edge technology faster than developing it internally. Rather than viewing startups with better technology as threats to be crushed, larger companies recognized that acquiring proven innovations could compress development timelines and reduce risk. This pattern has repeated throughout tech: Intel acquiring Altera (FPGAs), Nvidia acquiring various processor design teams, and AMD subsequently acquiring ATI (graphics). The acquisition demonstrated that you don't need to build everything yourself. Smart companies recognize when external innovation is superior and acquire it quickly.

What architectural principles from Nex Gen survive in modern processors?

The fundamental principle that Nex Gen proved—that a RISC-based approach to executing x86 instructions could be superior to direct CISC execution—remains embedded in virtually all modern processors. Both AMD (Ryzen) and Intel (current x86 processors) use instruction translation and RISC-like internal execution, exactly as Nex Gen pioneered. Modern processors decode complex instructions into simpler micro-operations that execute on optimized cores, a direct echo of Nex Gen's approach. Additionally, Nex Gen's success influenced thinking about performance-per-watt efficiency and the value of architectural specialization, principles that still guide processor design. The architectural lineage from Nex Gen through K6, Athlon, Opteron, and modern Ryzen is a direct chain of inheritance.

How did the Nex Gen acquisition affect competition between AMD and Intel long-term?

The acquisition transformed AMD from a marginal competitor into a sustained rival. Before Nex Gen, AMD competed primarily on price with architecturally similar processors. After the acquisition, AMD could compete on architecture, performance, and price simultaneously. This forced Intel to innovate harder and be more competitive on pricing, benefiting the entire market. The competitive dynamic established in the late 1990s persisted for decades, with both companies maintaining innovation investments and market share battles remaining genuinely competitive rather than one company dominating completely. This sustained competition has been beneficial for the industry, driving faster performance improvements and lower prices than would likely exist in a monopoly scenario.

Conclusion: The Startup That Changed an Industry

Nex Gen's story isn't just about one acquisition from 30 years ago. It's about how innovation flows through technology markets, how large companies respond to disruption, and why competition matters.

When Thampy Thomas founded Nex Gen in 1986 with backing from Compaq, ASCII, and Kleiner Perkins, the company wasn't trying to build a billion-dollar processor manufacturer. The founders were engineers solving a specific problem: proving that you could beat Intel's x86 architecture through clever design rather than copying its approach.

That proved harder than expected. Nex Gen's custom architecture required new motherboards. Market adoption was limited. The company went public but remained niche.

Then AMD recognized what Nex Gen had achieved. The company didn't need the entire business. It needed the architecture, the engineers, and the proof that this approach worked. That insight led to one of the best acquisitions in semiconductor history.

The K6 processor that followed wasn't revolutionary. It was a well-executed commercial product built on proven technology. It succeeded not because of dramatic innovation but because it delivered competitive performance at attractive prices to system builders and consumers.

From that success flowed everything that followed. AMD's continued existence as a processor competitor. The Athlon's dominance in the 2000s. The Opteron's success in servers. Modern Ryzen's current competitive position. All of it can be traced back to the decision to acquire Nex Gen and the decision to do it right.

The lesson for today's technology companies is clear: innovation doesn't happen exclusively at scale. Sometimes a small team with a good idea creates something valuable. Sometimes that valuable thing is best realized through acquisition and integration by a larger company. The companies that recognize this, move quickly, and execute integration effectively are the ones that maintain competitive advantage.

Nex Gen didn't survive as an independent company, but the company's architectural innovations shaped processor markets for decades. That's not failure. That's success in the only way that matters: the innovation got into the market, benefited users, and drove industry progress.

Thirty years later, every high-performance processor still carries traces of the ideas Nex Gen engineers pioneered. That's a legacy worth understanding.

Ready to build your own competitive advantage through intelligent technology decisions? Tools like Runable help engineering teams automate documentation, design presentations, and generate reports using AI-powered workflows starting at just $9/month. Whether you're analyzing complex technical decisions or building competitive strategy documents, AI-assisted automation accelerates your team's productivity.

Use Case: Engineering teams can use Runable to automatically generate technical analysis documents, competitive intelligence reports, and architectural decision documents—saving hours on research synthesis and documentation.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- NexGen pioneered RISC-based x86 execution that proved superior to Intel's CISC approach, a principle still used in modern processors

- AMD's $850 million acquisition of NexGen in 1995 compressed processor development timelines and reduced risk compared to 5-7 year internal R&D programs

- The K6 processor proved that competitive x86 architecture could succeed through intelligent design rather than manufacturing scale or brand dominance

- This acquisition established acquisition strategy as a core innovation method for large tech companies seeking to accelerate technology integration

- NexGen's legacy extends to modern Ryzen processors, showing how architectural decisions compound competitive advantages over decades

![NexGen, AMD's $850M Gamble: How a Startup Challenged Intel [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nexgen-amd-s-850m-gamble-how-a-startup-challenged-intel-2025/image-1-1768563738184.jpg)