Introduction: The Glove That Nobody Wanted But Everyone Remembers

The Nintendo Power Glove was objectively bad. Let's get that out of the way first, because it's important context for everything that follows. When you strapped that silver mesh gauntlet onto your hand in 1989, you were signing up for frustration, imprecision, and the kind of technical failure that made you question why you spent your birthday money on it in the first place.

But here's the thing about bad ideas that become culturally significant: sometimes the failure matters more than the success would have. The Power Glove didn't work well, which is exactly why its existence was so important. It introduced millions of players to a concept that nobody had really experienced before—the idea that you didn't need to hold a plastic pad with buttons anymore, that your actual body could be the controller. You could wave your hand and make things happen on screen. That sounds obvious now. In 1989, it felt like the future.

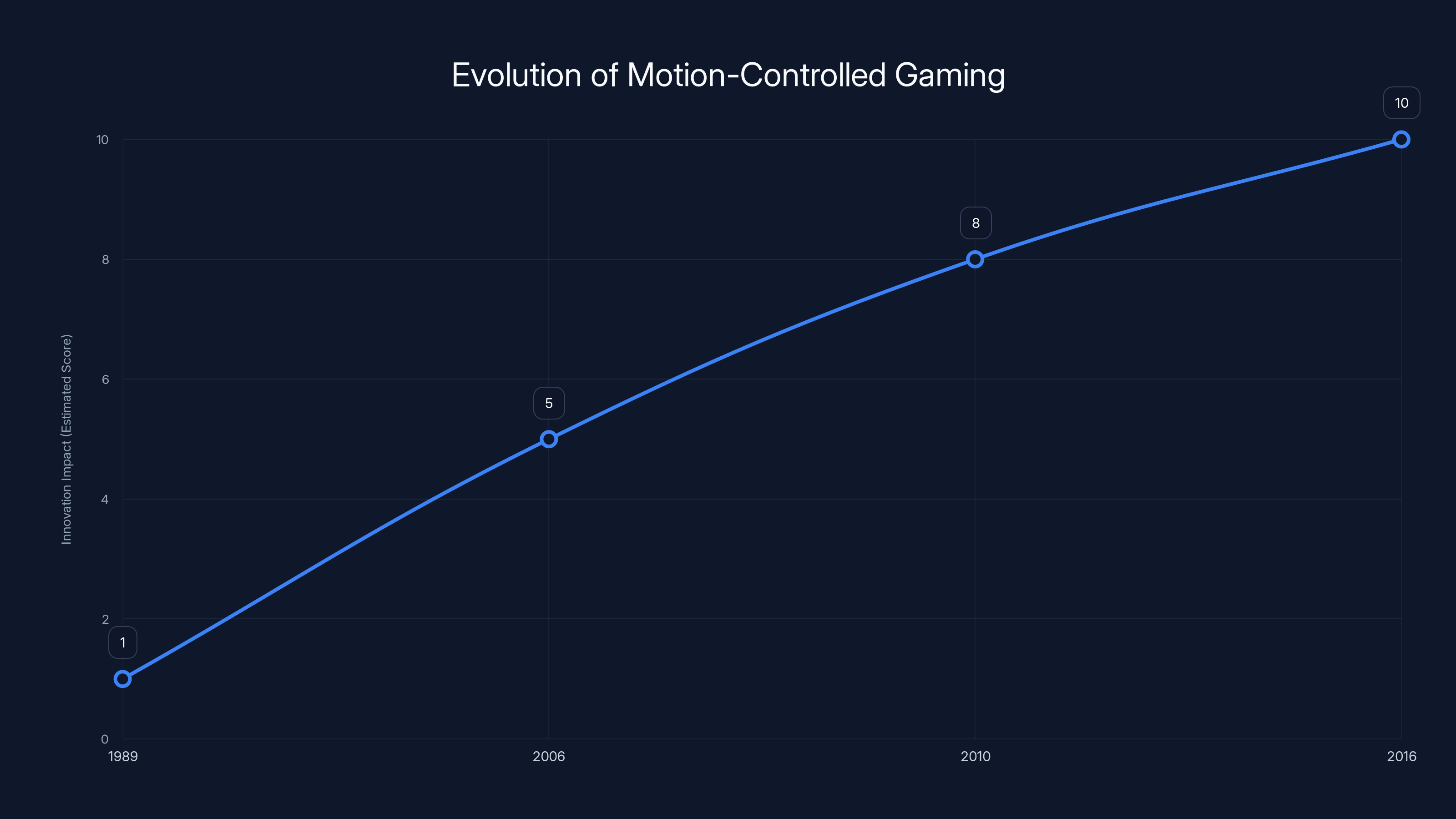

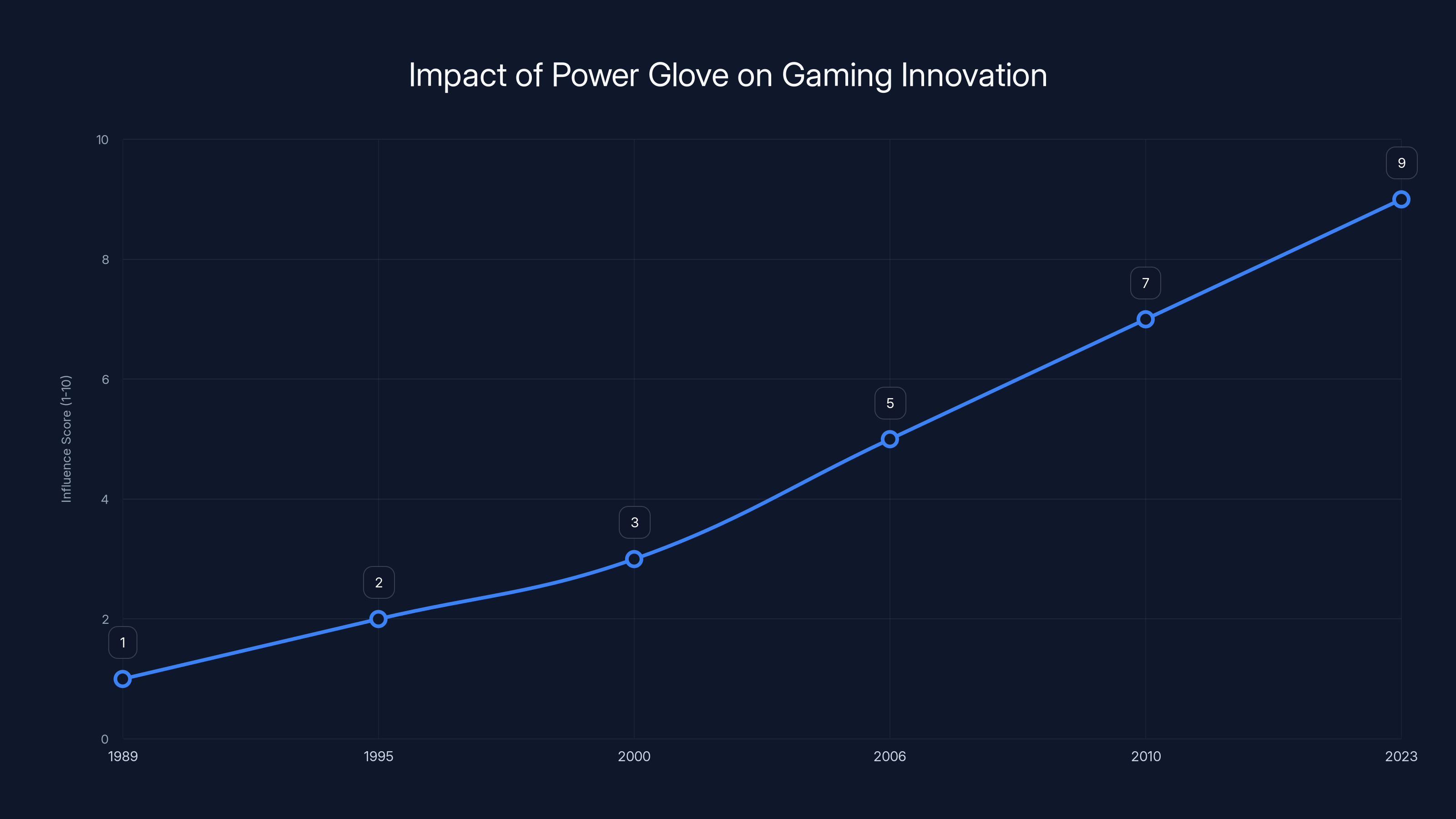

What makes the Power Glove's story so fascinating is that it wasn't even supposed to be a Nintendo product. It started as a research project somewhere else, got picked up by toymakers, went through a marketing campaign so aggressive it would be impossible today, and somehow ended up being remembered as one of the defining peripherals of an entire console generation. More importantly, you can draw a direct line from this flawed glove to the motion-controlled gaming that would dominate the next two decades. The Wii, the Kinect, even modern VR systems—they all owe something to the Power Glove's awkward, ambitious attempt to let people control video games with their entire bodies.

This is a story about ambition, failure, and how sometimes the best innovations come from products that almost nobody likes. It's about a device that was broken in almost every measurable way, yet somehow helped define the future of interactive entertainment. Understanding the Power Glove means understanding why we're still experimenting with body-controlled gaming today, why VR companies keep trying to get hand tracking right, and why video game companies have never stopped chasing the idea that maybe, just maybe, we could do more with our controllers than push buttons.

TL; DR

- The Power Glove was a technological failure: Poor tracking, imprecise controls, and a learning curve meant it was rarely useful for actual gaming

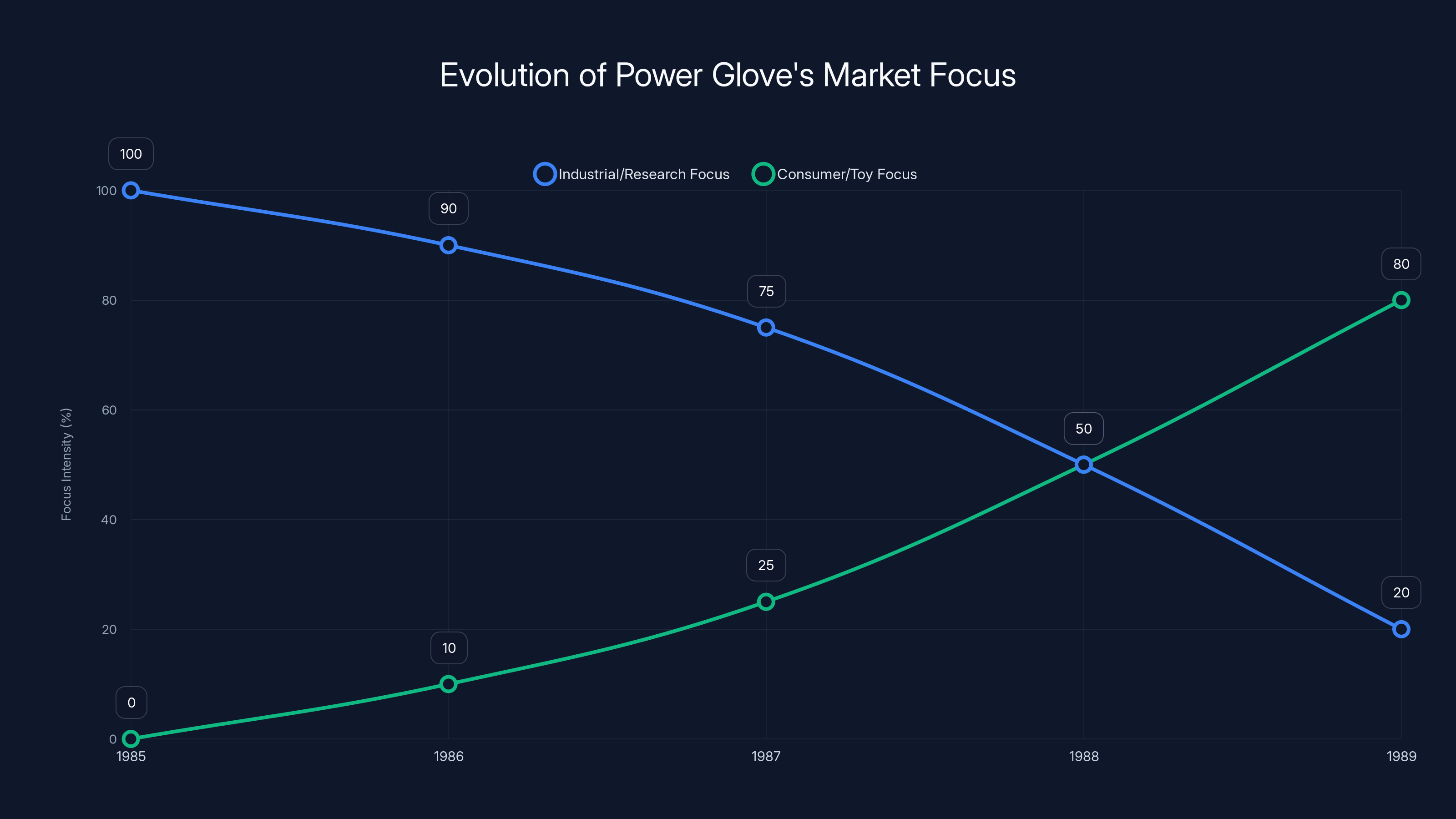

- It wasn't really a Nintendo product: The glove was developed by VPL Research and licensed to Mattel before Nintendo attached its name

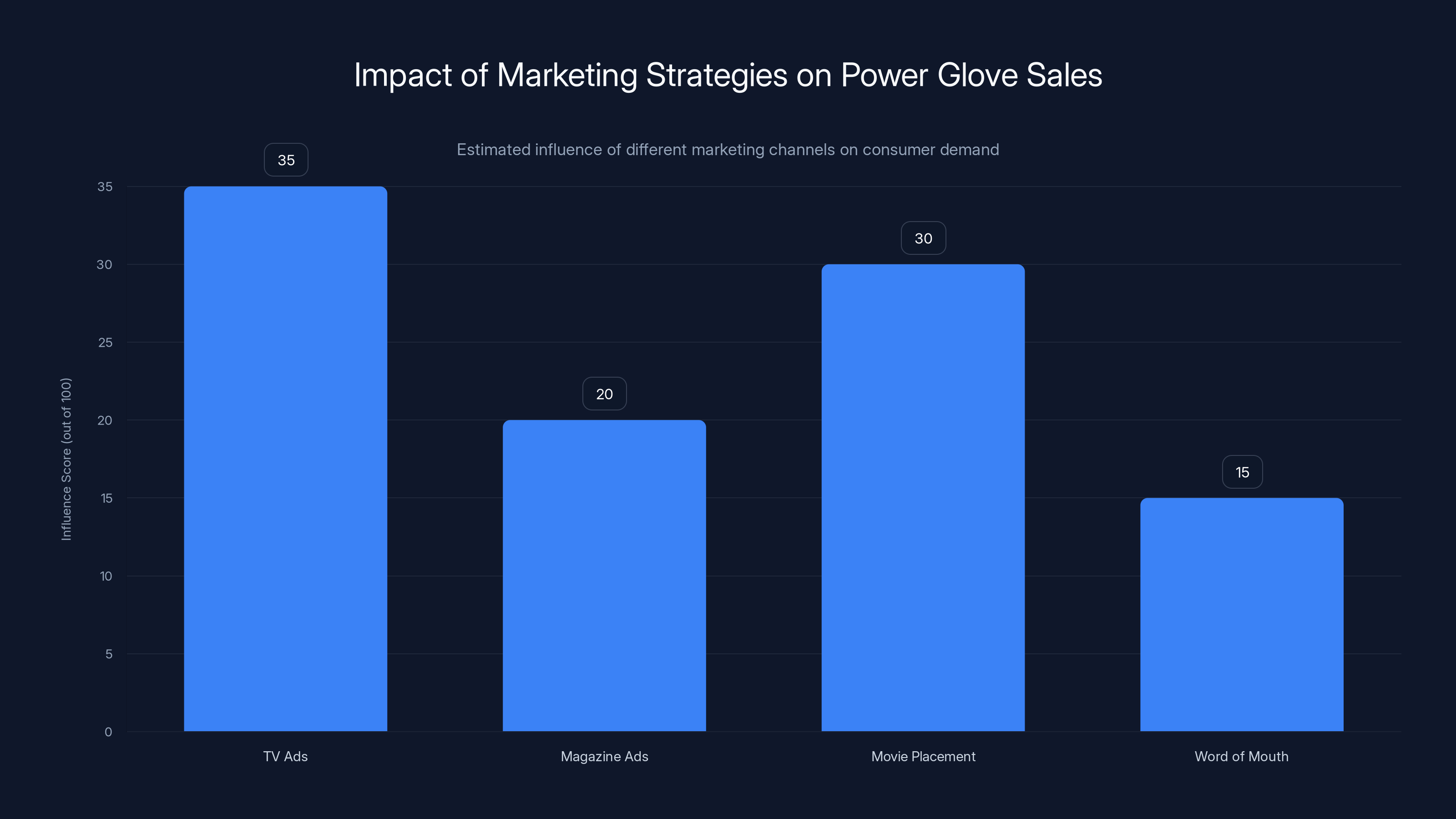

- Marketing made it matter: An aggressive advertising campaign and film placements made it essential to have, even if it didn't work

- It pioneered body-controlled gaming: The Power Glove introduced mainstream consumers to gesture-based control years before the Wii

- Its legacy is everywhere: Modern motion controllers, hand tracking, and VR systems all trace their lineage back to this failed peripheral

Despite the Power Glove's poor functionality, effective marketing strategies, particularly TV ads and movie placements, significantly drove consumer demand. Estimated data.

The Strange Origins: How a Research Project Became a Toy

Before the Power Glove was a Nintendo peripheral, it barely existed as anything at all. The actual technology came from VPL Research, a company founded by Jaron Lanier in the mid-1980s that was experimenting with early virtual reality hardware. Lanier and his team were building VR systems intended for expensive industrial and research applications, not for kids playing Super Mario Bros.

The hand tracking technology itself was genuinely impressive for its time. It used ultrasonic sensors and magnetic tracking to detect hand position and gesture, then translate that into digital input. The concept was sound. Two people in a room with different equipment could theoretically communicate through gesture-based VR interfaces. Scientists and researchers were genuinely interested in this technology. It represented a real breakthrough in how humans could interact with digital systems.

But VPL Research needed money, and the consumer market—specifically the toy market—represented a much larger potential revenue stream than industrial applications. The company couldn't manufacture and distribute a consumer product on its own, so they licensed the technology to Mattel, which had the manufacturing capability and retail relationships to actually get the thing into stores.

Mattel's approach was revealing. They understood that most consumers didn't care about the underlying technology. What they needed was a hook, a story, a reason to care. They rebranded the experimental VR glove as the "Power Glove," slapped it with an NES-themed visual identity, and positioned it as the next evolutionary step in gaming peripherals. It wasn't meant to be just another accessory—it was supposed to be revolutionary.

Nintendo's involvement was almost accidental. Nintendo had massive cultural clout in the late 1980s. If you could get Nintendo's blessing—or better, get Nintendo to attach its branding to your product—you basically won the market. Mattel pitched the Power Glove concept to Nintendo, and somehow convinced them that this experimental VR peripheral was worth putting their name on. Nintendo saw an opportunity to position themselves as the company pushing technology forward, and Mattel got the endorsement they needed. It was a marriage of convenience that nobody particularly wanted but everyone understood made business sense.

What made this partnership possible was timing. The Nintendo Entertainment System was at peak dominance. The company had successfully revived the console market after the 1983 crash. Parents, kids, and gamers all looked to Nintendo to define what gaming would be next. If Nintendo said the Power Glove was the future, millions of people would at least consider buying it.

The Power Glove in 1989 marked the beginning of motion-controlled gaming, paving the way for significant innovations like the Wii in 2006, Kinect in 2010, and VR systems in 2016. Estimated data.

The Marketing Machine: Creating Demand for Something That Didn't Work

This is where the Power Glove's story gets weird, because the marketing was actually brilliant, even if the product was terrible. Mattel and Nintendo understood something fundamental about consumer technology: if you can make people believe something is the future, you can sell it before anyone figures out it doesn't actually work.

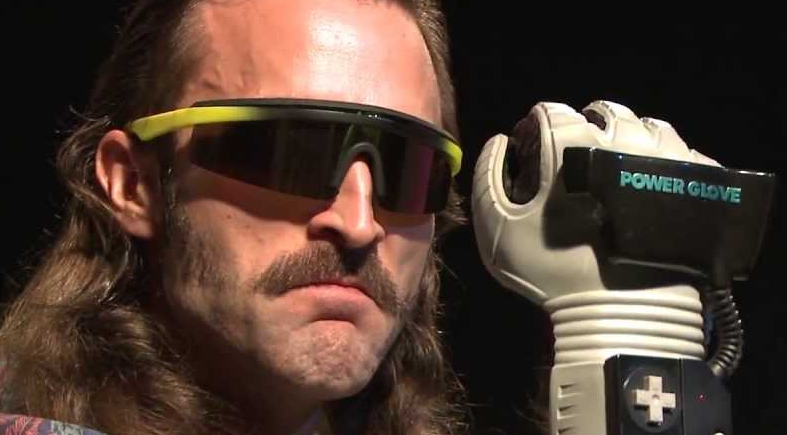

The advertising campaign for the Power Glove was relentless and sophisticated. We're talking primetime television spots during Saturday morning cartoons, magazine ads in gaming publications, and most critically, a major motion picture product placement that most people have forgotten but that absolutely shaped the glove's cultural moment.

That film was "The Wizard," released in 1989, a movie that was essentially a 90-minute advertisement for Nintendo products. The entire film was structured around a cross-country journey to a Nintendo gaming tournament, and the Power Glove was featured prominently as the ultimate gaming device—shown in trailers, worn by characters, positioned as the thing that would blow everyone's minds. The movie was barely coherent as a narrative, but as marketing, it was genius. Kids saw it and wanted the glove.

The television advertising was equally clever. Ads showed kids wearing the silver mesh glove, dramatically gesturing to control games, making it look like they had incredible power over the game world. The glove looked futuristic, felt exclusive, and represented everything that gaming kids thought they wanted—technology that was cutting-edge, that separated you from regular players, that made you feel like you had access to something most people didn't understand yet.

Here's what's important about this marketing: it worked. The Power Glove became a genuine cultural phenomenon. Kids wanted it. Not because it was good—most kids who actually used it figured out pretty quickly that it was basically unusable—but because everyone else wanted it, and because the marketing had successfully created an association between the glove and the future of gaming.

This is a masterclass in consumer psychology. You don't have to sell people a good product. You have to sell them the idea of a good product, the feeling of being ahead of the curve, the sense that owning this thing puts them in a special category. The Power Glove did that perfectly. For a while, if you had a Power Glove, you were cool. You were futuristic. You had the next generation of gaming technology in your living room.

Mattel sold something like 1 million units, which for a $200+ accessory in 1989 was actually pretty impressive. These were mostly purchased by kids who were convinced by advertising and cultural momentum, not by people who had actually tried one and thought it was good. The business model was essentially complete before anyone had time to figure out that the technology didn't actually work.

Why It Was Absolutely Terrible: The Technical Reality

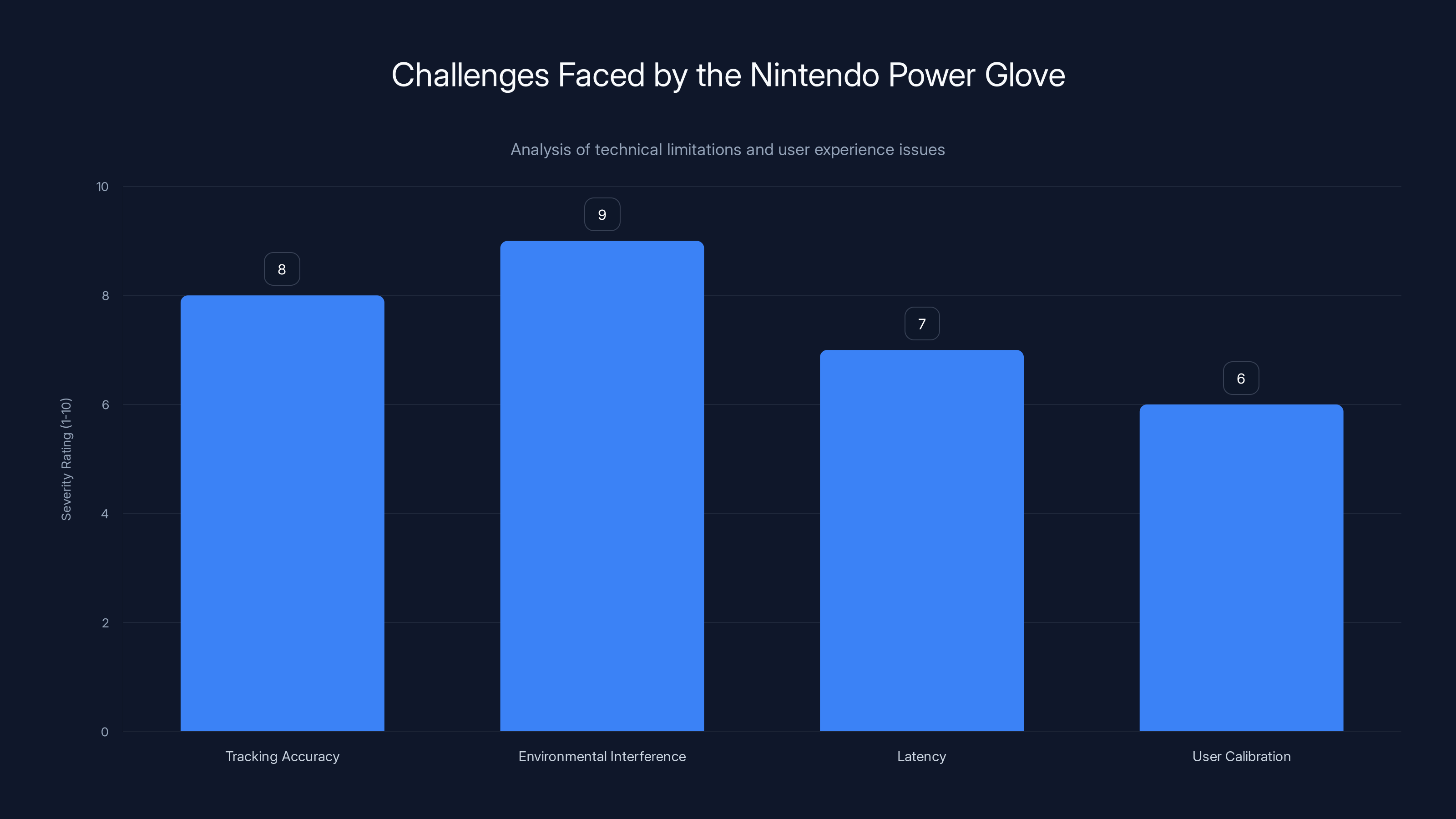

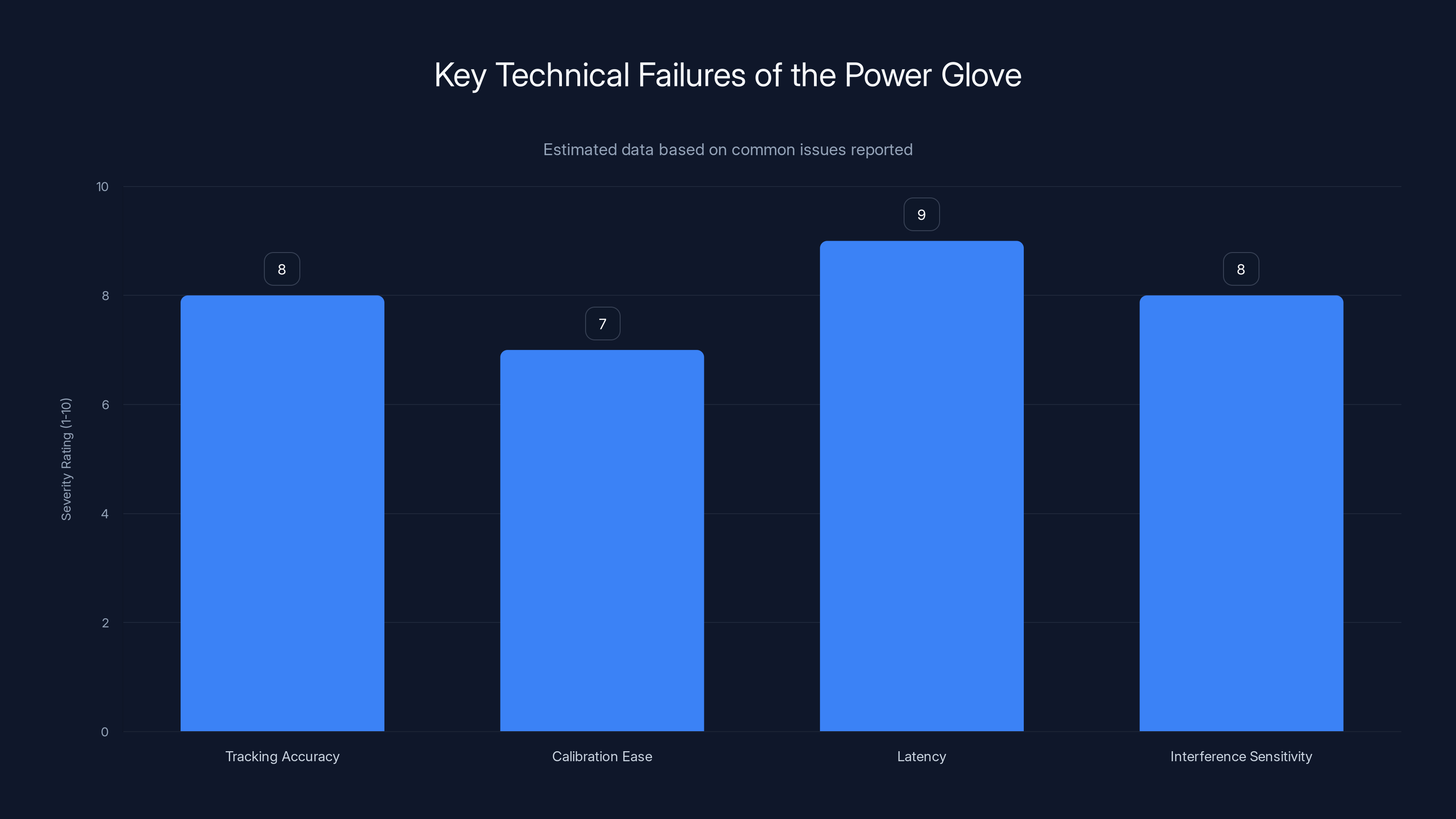

Now we get to why the Power Glove actually failed, and why understanding its failures is important to understanding its legacy. The problems were fundamental, not superficial. This wasn't a device that was close to working but had some rough edges. This was a device where almost nothing worked as intended.

The tracking system was the biggest issue. The Power Glove relied on ultrasonic sensors and magnetic position tracking, which sounds good in theory. In practice, it meant the glove was extraordinarily sensitive to interference. Metal objects in your environment could completely destroy the tracking. Your television set was made of metal. Your living room probably had other metal objects. The glove would just... lose track of where your hand was. You'd be gesturing at the screen, and the glove would think you were pointing in a completely different direction.

Calibration was another nightmare. You had to calibrate the glove every time you used it, running through a specific gesture sequence to tell it where your hand was in relation to the screen. Even after calibration, the accuracy was terrible. Your hand could be pointing directly at something on the screen, and the game would register your input somewhere completely different. The margin of error was huge—we're talking several feet in some cases.

The latency was awful too. There was a noticeable delay between when you moved your hand and when the game registered the movement. For a device that was supposed to let you use your body as a controller, any latency was catastrophic. It destroyed the sense of direct control. You'd move your hand, wait for the game to catch up, and by the time it did, you'd already moved on. It made the glove feel sluggish and unresponsive, which is basically the worst possible feeling for a controller.

The glove also had physical ergonomic problems. It was uncomfortable to wear for long periods. The fit was imprecise—it basically came in one size, and hands are not one size. If you had smaller hands, the sensors didn't track properly. If you had larger hands, the glove was too tight. Playing games for more than 15 or 20 minutes would leave your hand hurting.

Software support was minimal. Most NES games weren't designed for glove input, so the compatibility was limited. The games that did support it were often crude experiences that didn't really take advantage of the technology. You got a few games that let you play tic-tac-toe or draw pictures, but nothing that actually demonstrated why body-controlled gaming would be better than traditional controls.

The fundamental problem was that the underlying technology—sensing hand position and gesture in 3D space—was actually harder than anyone had really appreciated. It's still hard today. Modern VR hand tracking systems with cameras and neural networks still struggle with accuracy and latency. Doing it with ultrasonic sensors and magnetic tracking in 1989 was basically impossible to do well.

Yet despite all of this, or maybe because of it, the Power Glove mattered. The fact that it was so visibly broken meant that when people held it, when they tried to use it, when they experienced the gap between what the marketing promised and what the technology actually delivered, they understood something important: this is the future, but it's not ready yet. And maybe, just maybe, someone would fix it.

The Power Glove's focus shifted from industrial applications to consumer gaming between 1985 and 1989, driven by market potential. (Estimated data)

The Cultural Impact: Why a Bad Product Became Iconic

The Power Glove's cultural impact was completely disproportionate to its actual utility. This thing barely worked, yet it became iconic, memorable, and deeply associated with 1980s gaming and early VR experimentation. How does a broken product become culturally significant? That's actually a really important question.

Part of it was timing. The Power Glove arrived at exactly the moment when people were getting curious about what gaming could be if it pushed beyond just controllers and joysticks. Virtual reality was starting to appear in science fiction, in magazines, in the cultural consciousness. People were wondering if this was where entertainment was heading. The Power Glove, despite being broken, represented a tangible expression of that future.

Part of it was also the sheer audacity of the attempt. The glove was so different from anything else in gaming that it demanded attention. It looked futuristic. It promised something revolutionary. Even if it didn't work, even if gamers figured out pretty quickly that it was a waste of money, it was the kind of thing you told your friends about. It became conversation fodder, a shared cultural reference point.

The fact that it appeared in "The Wizard" was huge for its legacy. That film, despite being basically unwatchable, was seen by millions of kids. The Power Glove became associated with that moment, with that representation of gaming as aspirational and futuristic. Even if you never owned one, even if you never used one, you knew what it was. It had entered the cultural lexicon.

Gaming culture also played a role. The gaming community loves history, loves talking about weird peripherals, loves remembering the strange and ambitious failures. The Power Glove became the subject of countless retrospectives, YouTube videos, and nostalgic gaming blogs. People who never owned one started seeking them out, trying them, documenting how broken they were. It became a cult object, something you could point to as emblematic of a specific moment in gaming history.

The irony is that the Power Glove's cultural legacy is almost entirely built on its failure. If the device had actually worked perfectly, if everyone had loved it and it had been universally adopted, it would probably be forgotten now, just another successful gaming peripheral that did its job and got replaced by the next thing. Instead, because it was so visibly, obviously broken, it became something people remembered, talked about, and revisited. It became a symbol not of gaming's present, but of gaming's future aspirations and the gap between what we want and what we can build.

The Wii: How Nintendo Finally Got Motion Control Right

Fast forward to 2006. Nintendo released the Wii, and suddenly, motion-controlled gaming didn't seem weird or broken anymore. It seemed like the logical next step in gaming evolution. The Wii controller was simple—just an accelerometer and some buttons—nothing like the Power Glove's complex gesture tracking. But it worked. It actually worked.

The connection between the Power Glove and the Wii isn't direct. The Wii didn't use Power Glove technology or even build on it technically. But conceptually, they're intimately connected. The Power Glove introduced the idea that you could control games with your body instead of just your thumbs. The Wii proved that idea could actually be executed well.

Nintendo's leadership understood this connection. They knew that consumers were still curious about motion control, still interested in the idea of body-as-controller, but had been burned by the Power Glove experience. The Wii's marketing didn't have to convince people that motion control was the future—the Power Glove had already done that work. The Wii just had to convince people that motion control could actually work. And it did.

The difference was technological simplification. The Wii didn't try to do everything the Power Glove promised. It just tracked basic arm motion and rotation. That constraint—that willingness to do less but do it well—is what made the Wii successful. It took the ambitious concept from the Power Glove and made it practical.

In a very real sense, the Power Glove's failure paved the way for the Wii's success. By showing what didn't work, by demonstrating the gap between promise and reality, the Power Glove defined the challenge that Nintendo had to solve. Twenty years later, Nintendo succeeded where Mattel had failed.

The Power Glove, despite its commercial failure, set the stage for future innovations in gaming and VR, with its influence growing significantly over the decades. Estimated data.

Kinect and the Evolution of Motion Gaming

The story didn't end with the Wii. Microsoft's Kinect took the concept of full-body motion control even further. Where the Wii remote controlled your on-screen character by mimicking your movements, Kinect tried to understand your entire body in space and translate that directly into game input.

Kinect was, in many ways, a second attempt at what the Power Glove was trying to do—use your whole body to control games. But instead of a glove, Kinect used a camera and computer vision algorithms to track your skeleton. It was a completely different technical approach, but the goal was similar. It wanted to eliminate the controller entirely and just watch you move.

Kinect was successful in a way the Power Glove never was. It actually worked well enough to be useful. It had limitations—you needed space in front of your TV, tracking wasn't perfect—but it was functional and engaging. For several years, Kinect was genuinely popular. But it ultimately faced the same problem the Power Glove did: motion-controlled gaming was fun for novelty games but didn't necessarily make traditional gaming better.

However, Kinect's legacy wasn't in games. It was in VR, robotics, and computer vision more broadly. The computer vision technology that Kinect pioneered became foundational for how modern VR systems track hands and body position. When you use Meta Quest hand tracking today, or when you watch a VR system understand your hand gestures, you're using technology that has direct lineage to Kinect.

VR Hand Tracking: Finally Getting It Right

Modern VR systems are finally solving the problem that the Power Glove was attempting to solve in 1989. Inside-out hand tracking—where a VR headset's cameras watch your hands and understand what they're doing—is now table stakes for the best VR systems.

This technology is actually good now. A modern VR system can track your hands with sub-centimeter accuracy. It can understand individual finger movements. You can pick up virtual objects and manipulate them with precision. You can gesture and have the system understand what you mean. It's not perfect, but it's fundamentally different from what the Power Glove was attempting.

The leap from the Power Glove to modern VR hand tracking involved several technological breakthroughs. Machine learning made it possible to recognize hand postures in real time. Camera technology improved dramatically. Processing power increased. The algorithms got better. But the core ambition was the same: let people interact with digital environments using their hands instead of controllers.

What's interesting is that VR hasn't entirely ditched traditional controllers. Meta, Valve, PlayStation—they all still use handheld controllers as the primary input method. But they're adding hand tracking as an option, as an alternative, as a secondary input method. The lesson of the Power Glove—that hands are better than nothing but imperfect as controllers—has been learned and accepted.

Yet the conversation continues. VR companies still want to make hand tracking better. They want to reduce latency, improve accuracy, make it work in more lighting conditions. The dream of fully natural hand interaction in virtual environments is still very much alive. Every time a VR researcher works on hand tracking, they're working on a problem that the Power Glove identified 35 years ago.

The Power Glove faced severe challenges, particularly with tracking accuracy and environmental interference, which were rated highest in terms of issue severity. Estimated data.

The Technical Heritage: What Actually Worked About the Power Glove

Despite being broken, the Power Glove did introduce one genuinely innovative concept: using sensors embedded in a wearable device to track hand position. This wasn't entirely new—military research had explored similar ideas—but it was the first time this approach reached mainstream consumers.

The ultrasonic sensors were actually a decent idea, even if the execution was terrible. Ultrasound can propagate through air and bounce off hard surfaces, which means it can be used to estimate distance. Multiple sensors can triangulate position. In theory, this should work. In practice, the sensitivity to environmental interference made it unusable.

The magnetic tracking was another attempt at the same problem using a different technology. A magnetic emitter creates a field, and receivers in the glove detect the field strength and orientation to determine position. This also should work in theory, but again, real-world objects—especially metal objects—interfered with the signal.

What we know now is that these 1980s-era tracking technologies were fundamentally limited. They couldn't overcome their environmental sensitivity, and they couldn't provide the necessary accuracy and latency for real-time interactive control. But they represented a genuine attempt to solve a hard problem.

Modern hand tracking uses completely different technologies—primarily cameras and computer vision with machine learning post-processing. Instead of trying to track hardware sensors, it watches the actual hand and understands its position through visual analysis. This is technically more complex but fundamentally more robust. It doesn't require hardware in the hand, it doesn't depend on environmental emitters, and it can provide sub-centimeter accuracy.

Yet the Power Glove deserves credit for being the first mainstream exploration of this space. It demonstrated the problem, showed why it mattered, and gave people a concrete sense of what hand-based control could feel like, even if the execution was broken.

Why Motion Control Never Became the Default

Here's the fascinating paradox: despite all of this—despite the Power Glove, despite the Wii's success, despite Kinect, despite decades of VR development—traditional controllers are still the dominant input method for games. You sit down to play a game, and you pick up a controller. Your thumbs do most of the work. That's still the norm.

Why is that? Why hasn't motion control taken over? The answer is more nuanced than just "motion control doesn't work well." It's that traditional controllers are actually really, really good at what they do.

A traditional game controller gives you immediate, precise, analog control over character movement. You push the stick forward, your character moves forward. You push it all the way forward, your character runs. You push it halfway, your character walks. The latency is minimal. Your thumb provides constant, subtle feedback to the game.

Motion control is great for gesture-based input—for pointing, for selecting, for specific actions. It's less good for continuous analog input. You can't easily express "move forward at 30% speed" by moving your arm. You can express it with a thumbstick. That's why the Wii remote worked best when it was doing pointer-based controls (like in Wii Sports) rather than continuous movement.

The Power Glove and subsequent motion control attempts were always fighting against this fundamental limitation. Games are optimized around stick-based analog input. Making motion control work for those games meant designing around a less precise input method. It was possible, but it wasn't better.

So motion control found its niche. It works great for fitness games, for spatial manipulation games (like early VR), for experiences where you want the full-body engagement. But for traditional games—action games, sports games, racing games—stick-based controllers are still the standard because they're still the best tool for the job.

The Power Glove's failure was due to severe issues in tracking accuracy, calibration, latency, and sensitivity to interference. Estimated data.

The Persistence of the Vision: Why We Keep Trying

Despite the Power Glove's failure, despite motion control never becoming dominant, despite the technical limitations, the vision persists. Companies keep trying to make hand-based control work better. Why?

Because the vision is compelling. The idea that you could step into a virtual space and interact with it using your hands—not with controllers, not with keyboards, just your hands—feels right. It feels like the future. Even though the technical reality has proven that perfect hand-based control is harder than it seems, the goal is still worth pursuing.

Every generation of VR researchers builds on the work that came before. They understand what failed about the Power Glove, what didn't work about earlier VR systems, and what limitations they're facing with current technology. But they keep pushing, keep improving, keep trying to make hand control better and more reliable.

Part of this is just technological progress. A problem that was impossible in 1989 might be solvable with 2025 technology. The sensors are better. The processors are faster. The algorithms are smarter. What the Power Glove was attempting with rudimentary hardware, modern systems can accomplish with sophisticated computer vision and machine learning.

But part of it is also vision. Some engineers and researchers genuinely believe that hand-based interaction is going to be important for the future. They see a world where you don't need controllers, where you can just gesture and communicate with digital systems naturally. That vision drives them to keep working on the problem, even when progress is slow.

The Power Glove was broken, but it wasn't wrong about where technology was heading. It was just too early, with tools that weren't good enough. Eventually, the tools improved. The dream persists.

Learning from Failure: What the Power Glove Teaches Us About Innovation

There's a business lesson embedded in the Power Glove story that applies way beyond gaming. The lesson is about the gap between vision and execution, and about how sometimes the most important innovations come from products that fail commercially.

The Power Glove failed as a product. Most people who bought one quickly realized it was a waste of money. It had a brief moment of cultural visibility and then essentially disappeared from the market. By conventional metrics, it was a failure.

But in terms of impact on the industry, the Power Glove was wildly successful. It introduced a new way of thinking about game controllers. It showed the consumer market that gesture-based control was possible, even if it wasn't practical yet. It inspired two decades of follow-up attempts, from the Wii to modern VR hand tracking.

The lesson is that you can't always predict which failures will be important failures. Some failures are just products that nobody wants. Other failures are attempts at something genuinely new, where the failure teaches the industry something valuable. The Power Glove was the latter.

This has huge implications for how we think about innovation. It suggests that failure isn't always bad. Sometimes the most important thing a company or inventor can do is fail visibly, fail in a way that teaches the world something useful. The Power Glove showed that hand-based control was possible, even if the technology wasn't ready. That lesson has reverberated through 35 years of gaming and VR development.

The other lesson is about the relationship between marketing and reality. The Power Glove succeeded in marketing far beyond what the product deserved. Part of that was brilliance—the "The Wizard" tie-in was genuinely clever marketing. But part of it was also evidence of a willingness to sell a product that the company knew had serious limitations.

This isn't unique to the Power Glove. The entire history of consumer technology is littered with products that were marketed better than they worked. But the Power Glove is particularly instructive because the gap between promise and reality was so large, and yet the product still had cultural impact.

Modern companies have gotten better at managing these gaps. But the underlying tension remains: you want to generate excitement about what technology could do, while also being honest about what it actually does right now. The Power Glove basically ignored that tension and went all-in on excitement. It worked in the short term but left buyers disappointed.

The Legacy in Modern Gaming: Echoes of the Power Glove

Walk through a modern gaming convention, and you'll see echoes of the Power Glove everywhere. VR booths where people are using hand tracking instead of controllers. Motion capture systems for esports. Mobile games that use your phone's gyroscope to control gameplay. The concept that the Power Glove introduced—that your body could be the controller—has become foundational to how we think about interactive entertainment.

The Nintendo Switch includes motion controls in every Joy-Con controller, a feature inherited from the Wii but tracing back conceptually to the Power Glove. PlayStation VR uses hand tracking. Meta Quest hand tracking keeps getting better with each generation. The entire VR industry is built on the premise that hand-based interaction is important.

Even in games that don't use motion control, the influence persists. Game designers understand, at a fundamental level, that there are different ways to control games. Buttons and sticks are the traditional method, but they're not the only method. That expanded thinking about control schemes comes directly from the Power Glove era.

What's interesting is that motion control hasn't replaced traditional controllers. Instead, it's complemented them. Modern gaming systems let you choose how you want to interact with games. Want to use a controller? Sure. Want to use motion controls? Also available. Want to use hand tracking in VR? That's an option too. The industry has learned that one-size-fits-all input method doesn't work. Different games need different input methods.

This is, in a sense, the final victory of the Power Glove. It didn't win the battle to replace the controller. But it won the war to expand what was possible, to show that gaming could be more than just thumbs on sticks, to inspire 35 years of exploration into different ways of interacting with digital worlds.

The Future: Where Hand-Based Control Is Heading

Looking forward, hand-based control is going to keep improving. The next generation of VR systems will have even better hand tracking. The latency will drop further. The accuracy will improve. The finger-level tracking will become more sophisticated. Within a few years, hand tracking in VR will probably be better than any handheld controller for certain types of tasks.

But that doesn't mean controllers will disappear. Controllers are probably going to remain the primary input method for traditional games. What will change is that you'll have more options. You'll be able to reach for whatever input method works best for what you're trying to do.

The other frontier is gesture recognition at a distance. Instead of wearing a glove or holding a controller, instead of relying on hand tracking in VR, what if you could just gesture in space and your device would understand what you meant? Imagine walking into your living room and gesturing to start your game, pause it, adjust settings—all without holding anything.

That's what we're moving toward. It's the natural end-point of the trajectory that the Power Glove started. It's not here yet. There are still problems with latency, with recognizing ambiguous gestures, with working in different lighting conditions. But these are engineering problems, not fundamental impossibilities. We'll probably solve them.

When we do, the Power Glove will be remembered as the first step on that journey. Not the last word, not even particularly successful as a product, but the first real attempt to show consumers that there was another way. That you didn't have to hold something to control games. That your body could be the input device.

That was the Power Glove's real innovation. Not the technology itself—that was broken. But the idea. The demonstration that the category existed, that it mattered, that it was worth pursuing. Thirty-five years later, we're still pursuing it. That's the real legacy.

Why the Power Glove Mattered More After It Flopped

There's one final layer to understanding the Power Glove's significance, and it involves understanding what happened after it failed. Because here's the thing: the Power Glove could have just disappeared. Nobody would have remembered it. It would have been a footnote, a weird peripheral that existed for a few years and nobody cared about.

But that's not what happened. Instead, the failure became interesting. Gaming culture looked back at the Power Glove and said, "Wait, this was actually trying something new, even if it didn't work." The product became more culturally significant after it failed than it was when it was being marketed.

This happens with certain technologies. We mythologize the failures that represented ambitious attempts. The Segway is a great example—it was supposed to revolutionize urban transportation, nobody actually uses them, but people are still fascinated by it because it represented an ambitious vision. The Power Glove is similar.

What makes the Power Glove special is that the vision it represented—hand-based, gesture-based control of digital systems—actually did become important. Not exactly as the Power Glove imagined it, but conceptually, that direction is where gaming has gone. The Power Glove was wrong about how it would happen, wrong about the timeline, wrong about the technology, but right about the direction.

That's rare. Most failed products represent visions that turned out to be wrong. They tried something, it didn't work, and we learned that that particular direction wasn't viable. The Power Glove tried something, it didn't work, but the underlying vision turned out to be right. We just needed better technology and better approaches.

So the Power Glove is instructive as a failure because it teaches us something important about innovation: sometimes the right vision and the wrong execution can still point you in the direction of the future. The Power Glove didn't work, but it worked well enough to inspire everyone who came after it. That's actually a pretty valuable failure.

FAQ

What was the Nintendo Power Glove?

The Nintendo Power Glove was a peripheral controller released in 1989 for the Nintendo Entertainment System that attempted to let players control games using hand gestures and arm movements instead of traditional button-based controllers. It was a silver mesh glove that used ultrasonic and magnetic sensors to track hand position and translate movements into game input. Despite being marketed as a revolutionary gaming device, it was notoriously unreliable and largely abandoned after a brief period of popularity.

How did the Power Glove technology actually work?

The Power Glove used multiple tracking technologies simultaneously. Ultrasonic sensors in the glove would emit ultrasonic signals that bounced off hard surfaces in the room to estimate the glove's distance from receivers, while magnetic position sensors tracked the glove's location relative to a magnetic emitter near the television. The combination of these two systems was supposed to create accurate 3D hand tracking, but environmental interference from metal objects and other obstacles made the system highly unreliable and prone to losing calibration constantly.

Why was the Power Glove so bad at tracking hand movement?

The Power Glove suffered from fundamental technical limitations that were difficult to overcome with 1980s technology. The ultrasonic sensors were extremely sensitive to environmental interference from metal objects, appliances, and even the television itself, which could completely destroy tracking accuracy. Magnetic tracking was similarly vulnerable to interference. The glove required constant recalibration, had significant latency (delay) between hand movement and game response, and couldn't maintain consistent accuracy across different room configurations. These weren't design flaws that could be easily fixed—they were inherent limitations of the tracking technologies being used.

Did the Power Glove actually influence modern gaming and VR?

Yes, the Power Glove was conceptually influential even though it was technically flawed. It introduced mainstream consumers to the idea that games could be controlled with full body movement rather than just button presses and joysticks. This vision directly inspired the Nintendo Wii's motion controls, which dominated the 2000s, and conceptually paved the way for modern VR hand tracking systems that now use camera-based computer vision instead of sensor gloves. While the Power Glove's specific technology didn't persist, the category of gesture-based and motion-based gaming that it pioneered has become standard across multiple gaming platforms.

Why did the Power Glove fail commercially if it was so well-marketed?

The Power Glove failed commercially because the gap between what the marketing promised and what the product actually delivered was enormous. Advertising campaigns and its appearance in "The Wizard" convinced consumers that the glove offered intuitive, responsive hand-based control. In reality, the tracking was unreliable, the latency was significant, and most games that supported it offered poor experiences. Once buyers realized the product didn't work as advertised, word-of-mouth quickly turned negative and sales dried up. It's a classic example of how superior marketing can't overcome fundamental product failures for long-term success.

What was the relationship between the Power Glove and Nintendo?

The Power Glove was developed by VPL Research and manufactured by Mattel, who licensed the technology. Nintendo didn't actually invent or develop the device—they licensed the use of their brand and their platform compatibility. Nintendo's involvement was more about lending credibility and distributing the product through Nintendo channels rather than being involved in the actual technology development. This is why the Power Glove is technically a Mattel product that happened to have the Nintendo Entertainment System branding, not an original Nintendo peripheral.

Conclusion: The Broken Promise That Built the Future

The Nintendo Power Glove sits at a weird intersection of failure and influence. It's a product that almost nobody liked, that performed poorly technically, that burned consumers who bought it, and yet somehow managed to be foundational to how we think about gaming input methods today.

That's actually the point. The Power Glove's importance isn't despite its failure—it's partly because of it. By failing so visibly, so publicly, and so dramatically, the Power Glove forced the industry to confront a question: what would body-controlled gaming actually look like if we did it right? That question drove innovation for 35 years.

We can draw a direct line from the Power Glove to the Wii, to Kinect, to modern VR hand tracking. But we can also draw a line in the opposite direction—from modern success back to that failed 1989 peripheral, recognizing it as the first serious attempt at something that the industry had been speculating about but never really tried.

The lesson is worth internalizing. Sometimes the most important innovations come from visible failures. Sometimes the product that everyone knows doesn't work teaches you more than the product that works perfectly. Sometimes the company that takes the biggest swing and misses is the one that points the entire industry in a new direction.

The Power Glove was broken. But what it broke was the assumption that you could only control games by holding a device with buttons. That was worth breaking. That break echoes through gaming and VR today.

So yeah, the Power Glove was terrible. And that made it important. That made it memorable. That made it the first step toward a future that we're still walking toward, one hand gesture at a time.

Use Case: Document the technical history of a failed gaming peripheral, create an interactive timeline, or generate a presentation about gaming innovation and its influence on modern VR systems.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- The Power Glove was technically broken but conceptually important—introducing body-controlled gaming to mainstream consumers

- A failed product can teach an industry more than a successful one if it represents an ambitious vision

- The line from Power Glove through Wii to modern VR hand tracking shows 35 years of iterative improvement on the same core idea

- Motion control hasn't replaced traditional controllers because sticks are still better for certain tasks, but complementary input methods are now standard

- The Power Glove's real legacy isn't the technology—it's proving that gesture-based interaction was possible and worth pursuing

![Nintendo Power Glove: The Failed Controller That Shaped VR [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nintendo-power-glove-the-failed-controller-that-shaped-vr-20/image-1-1766950543151.jpg)