Nintendo's Virtual Boy Switch Peripheral: Design Triumph, Gameplay Struggle [2025]

Last month, I spent two hours with Nintendo's newly reimagined Virtual Boy—the $100 headset peripheral that turns your Switch into a stereoscopic 3D gaming machine. Walking into that hands-on event, I expected either buyer's remorse waiting to happen or a clever piece of gaming archaeology that actually works. What I found was something weirder than both.

The Virtual Boy sits in this strange middle ground where it excels at one job—looking impossibly cool—while completely fumbling another—actually being fun to play. And that contradiction is way more interesting than it sounds.

Here's the thing: Nintendo's original Virtual Boy, released in 1995, ranks among the company's most spectacular failures. It sold roughly 770,000 units in a world where the Game Boy had already crushed 118 million. The red monochromatic display caused headaches, the game library was thin, and the whole thing felt like a gimmick looking for a reason to exist. For decades, Nintendo basically pretended it never happened—which somehow made the device even more legendary among collectors. Original cartridges now sell for hundreds of dollars, and obsessive hobbyists have spent years reverse-engineering the hardware.

But timing changes everything. In 2025, Nintendo's confidence seems unshakeable. The Switch is the second-best-selling console ever, Switch 2 is launching, and the company has proven it can monetize nostalgia through its Nintendo Switch Online service. Resurrecting the Virtual Boy as a $100 accessory—not a standalone console—is exactly the kind of calculated risk that feels almost arrogant. And maybe that's why it worked at the design level. The execution, though? That's where things get messier.

Design That Actually Impresses

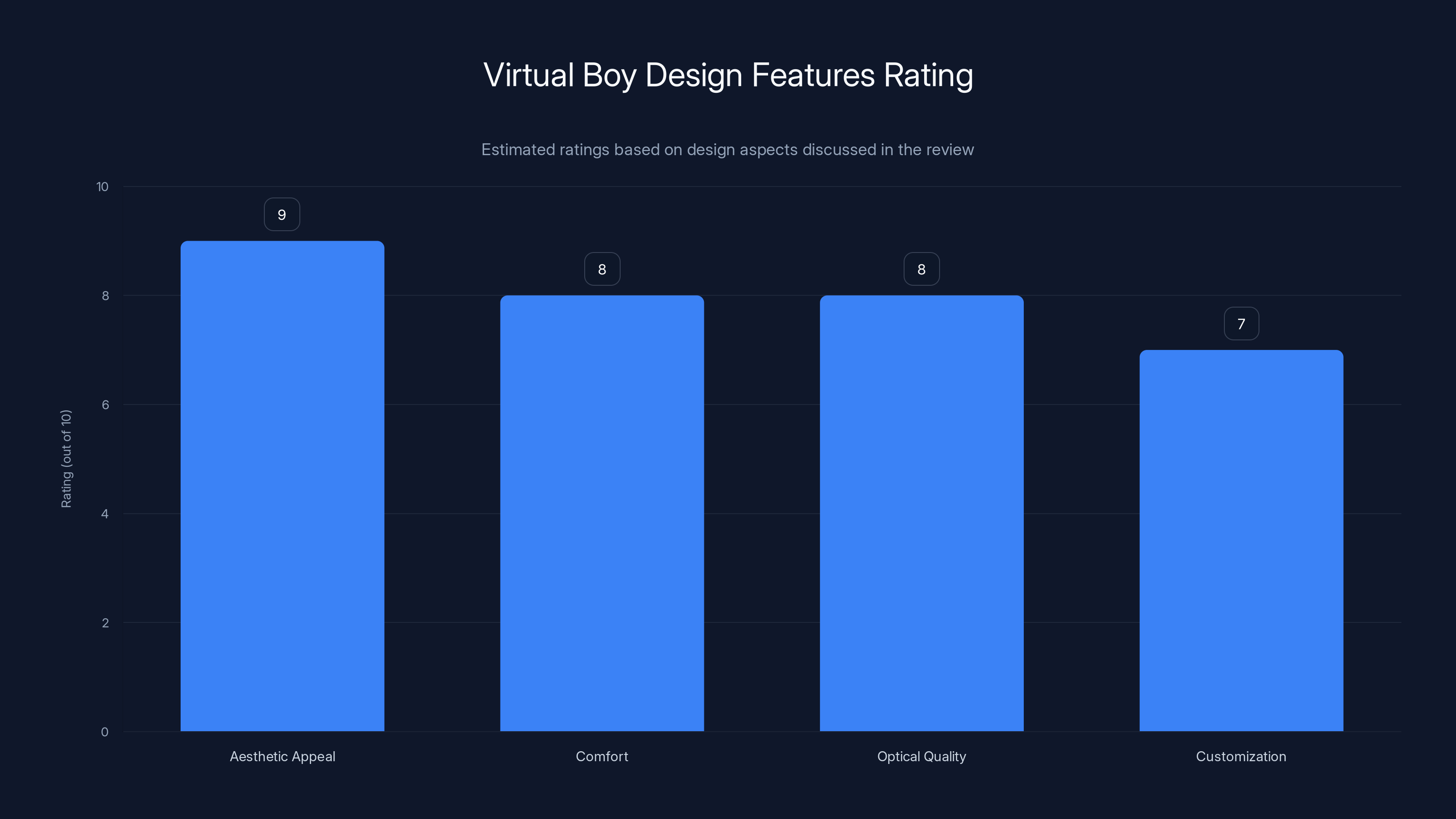

Let me be direct: the physical device is beautiful. I say that as someone who usually finds VR headsets uncomfortable and vaguely ridiculous-looking. The Virtual Boy peripheral somehow avoids both traps.

The red plastic chassis feels immediately familiar if you grew up in the '90s. Nintendo could've made this thing look like every modern VR headset—black, angular, aggressively futuristic. Instead, they committed to the aesthetic. The device has a retro charm that doesn't feel ironic or condescending. It's not winking at you. It just looks good.

The comfort factor is where I was genuinely surprised. Most VR headsets create a seal around your eyes that can feel claustrophobic after ten minutes. The Virtual Boy's design distributes weight differently. Your face slots into the headset, and there's this weird proprioceptive comfort to how it sits. After two hours of testing, I didn't have a headache. My face didn't feel bruised. The padding could use more sophistication, but for a device that costs less than most actual VR headsets, it's surprisingly thoughtful.

The optical quality is another win. You insert your Switch or Switch 2 into a dock at the front of the headset, and the stereoscopic lenses do their job without distortion. The depth perception is noticeable—sometimes subtle, sometimes dramatic depending on the game. Unlike my old Labo cardboard headset, which would leak external light and kill the illusion, the plastic Virtual Boy creates genuine darkness. That matters for immersion.

One small detail that speaks volumes: the color palette is customizable. The original console was locked to red and black. This one lets you shift the color scheme through system settings. It's a tiny feature, but it shows Nintendo learned something from the original device's limitations. Variety helps with comfort during longer play sessions.

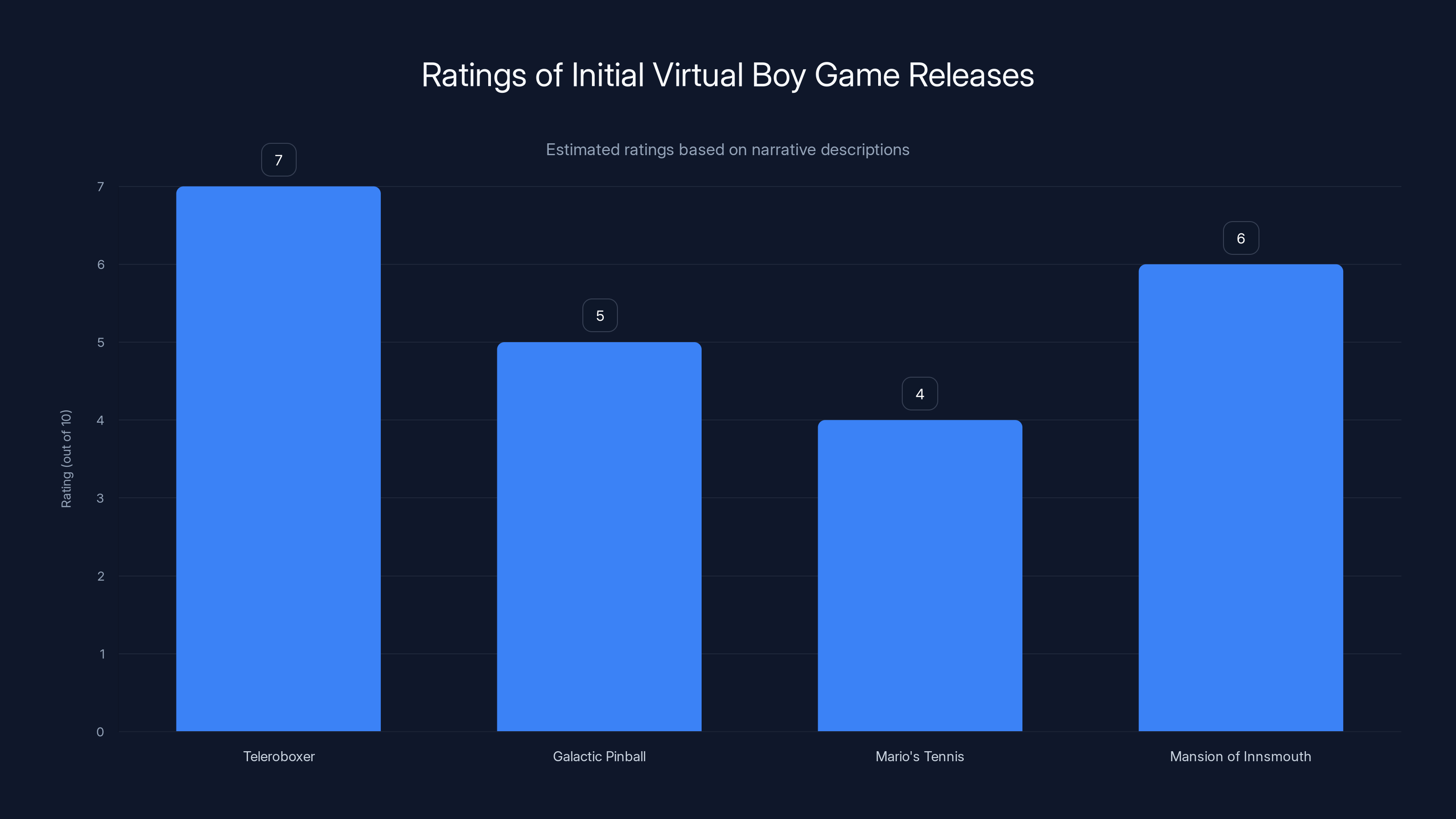

Estimated ratings suggest Teleroboxer is the most playable, while Mario's Tennis struggles with perspective issues. Estimated data.

The Game Library Problem

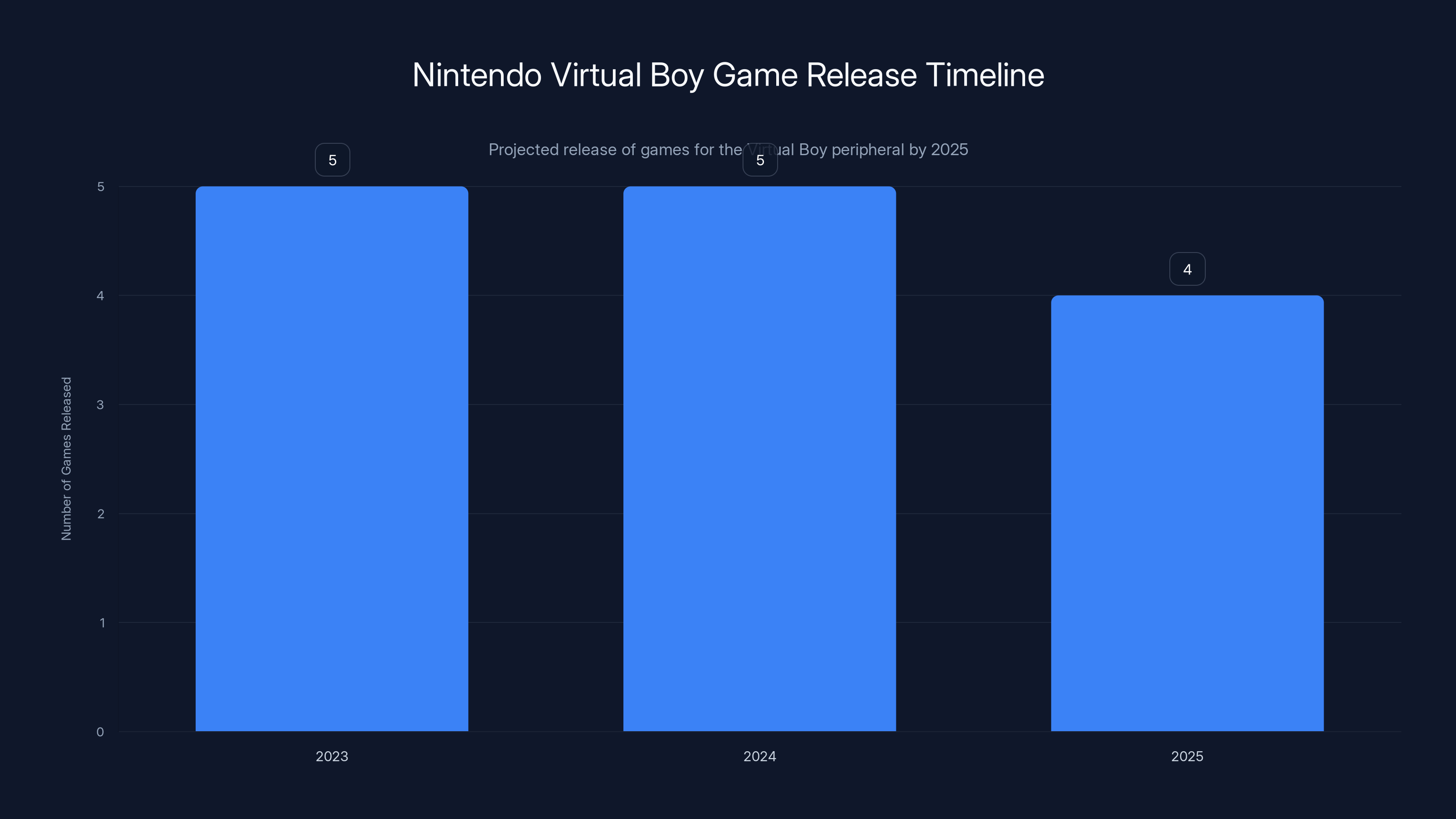

Here's where the device hits a wall. Nintendo plans to release 14 Virtual Boy games through Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack by the end of 2025. The first batch arrived on February 17th: Galactic Pinball, Teleroboxer, Mario's Tennis, Mario's Game Gallery, and a new port of The Mansion of Innsmouth.

Fourteen games. For a $100 piece of hardware. Even if every single one was exceptional, that's a problem. But these aren't exceptional. They're relics.

Teleroboxer is the most immediately playable. You control a wireframe boxer, and the 3D perspective actually creates tactical depth. You need to read distance, timing, and punch angles in a way 2D wouldn't allow. It's not complex, but it works. The game feels designed for what the hardware can do.

Galactic Pinball, by contrast, feels like someone translated a pinball table into wireframe geometry and hoped for the best. The ball physics work, technically. Your flippers respond. But there's no visceral feedback. Traditional pinball on a 2D screen is more fun because you can actually read the table. Here, the 3D angle makes it harder to track the ball's movement.

Mario's Tennis is perhaps the most telling failure. The sport demands precision timing and clean visual feedback. On the Virtual Boy, the perspective shifts constantly as you move around the court. Players appear at odd angles. Judging depth becomes a guessing game. After three matches, I understood why the original sold only 770,000 units. This shouldn't have been ported. It was probably not a great game in 1995, and it's definitely not a great game now.

The new Mansion of Innsmouth port is interesting because it's actually a more modern game (originally a 1997 PC adventure) adapted for stereoscopic 3D. It's the closest thing to a "full game" in the launch lineup. But even that reveals the core problem: these games were never designed with modern expectations in mind. No procedural generation, no branching narratives, no accessibility features.

Nintendo says 14 games by December 2025, but hasn't committed to more. That number feels simultaneously generous and insufficient. Generous because porting old games costs money, and Nintendo is essentially subsidizing your hardware purchase through Switch Online. Insufficient because 14 games doesn't create an ecosystem. It creates a curiosity.

Why the Gameplay Feels Dated

There's something specific happening here that's worth unpacking. These games don't just feel old because they're from 1995. They feel old because game design has moved on in ways that make stereoscopic 3D actually matter less than you'd think.

Modern game design assumes complexity. Multiple layers of UI, branching mechanics, dynamic systems. The Virtual Boy games are deliberately simple. Teleroboxer is literally: punch, block, move. That's not a limitation of the hardware anymore. It's a limitation of the original design philosophy.

When you add stereoscopic 3D to simple games, the depth doesn't compensate for the lack of depth in other dimensions. You're not gaining anything. You're trading speed and clarity for dimensional information you never really needed.

Compare this to something like Tetris Effect on a modern display—which uses 2D brilliantly—versus the Virtual Boy's version of Tetris, which just adds depth without changing how the game plays. The 2D version is faster, cleaner, and more satisfying. The 3D version is technically impressive and mechanically identical.

This is why the device feels less like a rediscovery of a lost format and more like an expensive museum exhibit. You appreciate what it represents. You don't actually want to spend forty hours with it.

Nintendo plans to release a total of 14 games for the Virtual Boy peripheral by the end of 2025, with 5 games already available in 2023.

The Hardware: Comfort and Ergonomics

Let's separate the device from the software for a moment. Purely as a piece of engineering, the Virtual Boy peripheral makes smart compromises.

Weight distribution is handled better than most VR headsets. The device doesn't clamp around your head with excessive force. Instead, it rests on your face with measured pressure. This matters because neck strain during VR use is real, and Nintendo's approach minimizes that particular complaint.

The dock mechanism for inserting your Switch is intuitive. There's no fumbling. The screens align properly, and the lenses focus without adjustment. You insert, close the panel, and you're in the game. Setup takes maybe ninety seconds. That's genuinely well-designed.

The controller options are flexible. You can use a single Joy-Con, paired Joy-Cons, or a Pro Controller. Nintendo didn't force a proprietary controller, which would've been the aggressive move. Instead, they let you use whatever you're comfortable with. That's consumer-friendly thinking.

But here's the issue: comfort stops mattering when you're not having fun. I could wear the Virtual Boy for eight hours straight if I wanted. I'd be comfortable the entire time. I'd also be bored after the second hour.

Nintendo Switch Online Integration

The real genius of this product isn't the hardware. It's how Nintendo positioned it within their ecosystem.

The Virtual Boy isn't sold as a standalone console. It's a

That's actually clever. It lowers the barrier to entry. You're not investing in a new console. You're buying a peripheral that unlocks specific games within a service you probably already use.

But it also reveals the limitation. If you're not subscribed to Switch Online +, the Virtual Boy is literally a fancy piece of plastic. There are no cartridges. There's no local storage. Everything is tied to the subscription. That's convenient for Nintendo's revenue stream and terrible for your ownership rights.

The pricing structure also creates a weird incentive problem. Fourteen games included in your subscription doesn't feel like value when you paid $100 for the privilege of accessing them. It feels like you're paying twice.

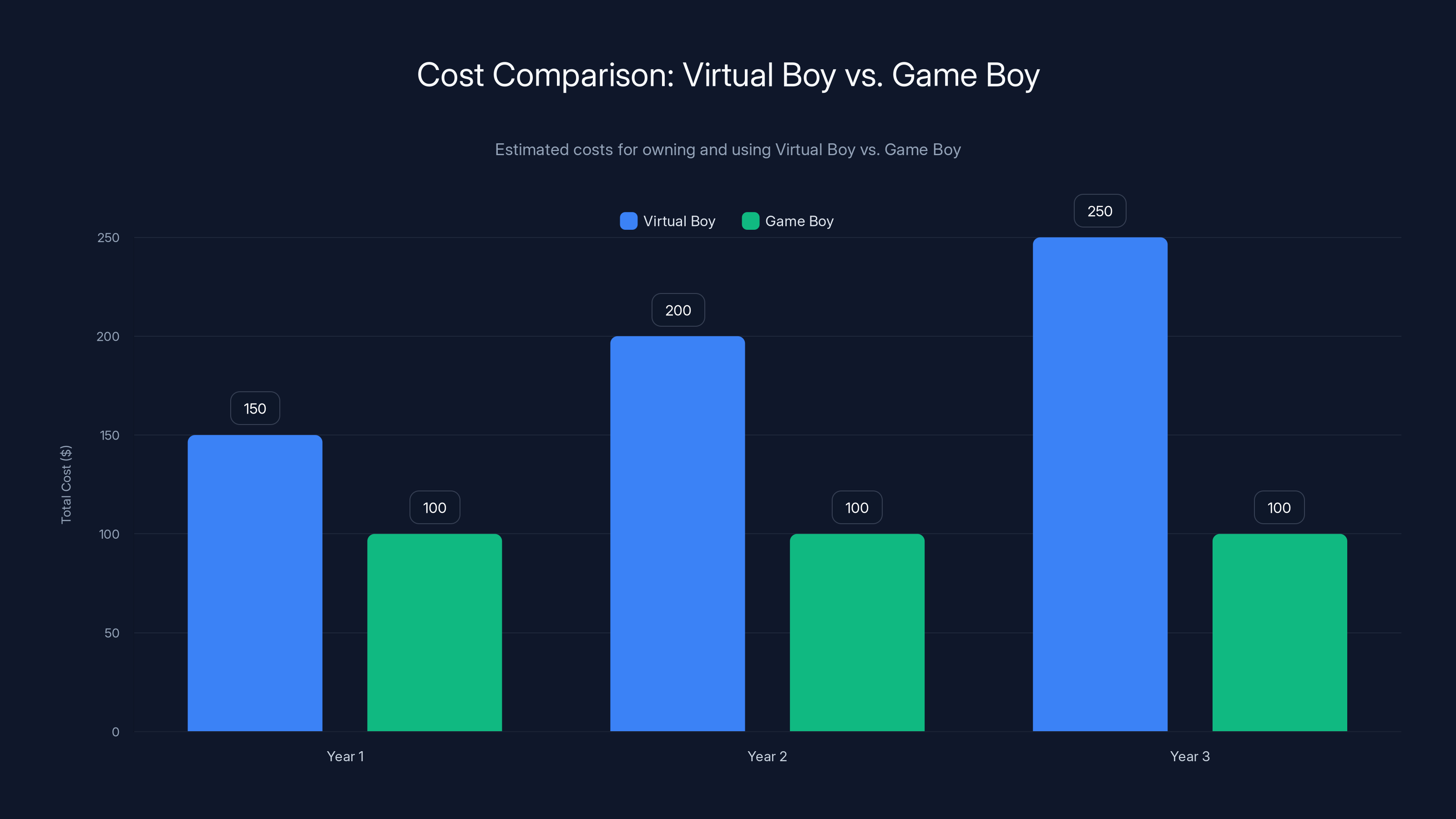

Compare this to how Nintendo handled the Game Boy: you bought the hardware, you bought the cartridge, you owned both. Complete ownership and no recurring fees. The Virtual Boy peripheral model is fundamentally different, and whether that's good or bad depends entirely on how you feel about subscription gaming.

Why Nostalgia Alone Doesn't Work

There's a dangerous assumption baked into this entire product: that people want to play Virtual Boy games because those games represent a piece of Nintendo history. That's true in a narrow sense. Collectors do. Hobbyists do. Hardcore Nintendo fans curious about an artifact of corporate history—sure.

But regular consumers? Not really.

The original Virtual Boy was a failure not because it was ahead of its time, but because it solved a problem nobody had. People didn't want stereoscopic 3D gaming in 1995. They wanted better games, more games, and hardware that didn't give them migraines. The Virtual Boy offered none of those things.

Fast-forward thirty years, and the problem statement has changed, but the solution hasn't improved. Stereoscopic 3D gaming is still a niche feature. Modern gamers care about frame rates, graphics quality, gameplay innovation, and massive game libraries. The Virtual Boy offers exactly one of those things—frame rates are solid—and it's the least important one.

Nostalgic purchases work when they deliver on the nostalgia while also being functional modern products. The Teenage Engineering OP-1 field synthesizer works because it's retro-styled but also genuinely useful for modern music production. Nintendo's Game Boy Pocket worked because it looked cool and still played every Game Boy game ever made.

The Virtual Boy peripheral works as a nostalgic object—it looks cool sitting on your desk—but not as a platform for modern gaming. That's a fundamental issue that no amount of design polish can fix.

The Virtual Boy, including subscription costs, becomes more expensive over time compared to the one-time purchase cost of a Game Boy. Estimated data.

The Cardboard Alternative

Nintendo also released a $25 cardboard version of the Virtual Boy, styled after their Labo kits. It's almost tempting to recommend that over the plastic version.

The cardboard version uses the same lenses and basic optical design. The main differences are material and durability. Cardboard is clearly not as robust as plastic. After six months of regular use, the cardboard would probably start showing wear. But if you only plan to use the Virtual Boy occasionally—which you probably should, given the limited library—the $25 option makes financial sense.

Cardboard also has a fun tactile quality. There's something appealing about a gaming device you can customize or even rebuild if it gets damaged. The plastic version is locked and finished. The cardboard version feels more experimental and playful.

For a

The Precedent This Sets

Here's what actually matters about the Virtual Boy peripheral: it shows Nintendo is willing to resurrect any piece of its history if the nostalgia angle seems profitable.

That's not inherently bad. Nostalgia is powerful, and Nintendo's back catalog is genuinely valuable. But it creates a strange dynamic where hardware success is decoupled from software quality. The Virtual Boy peripheral will probably sell fine. Not millions of units, but enough to be profitable. People will buy it for the aesthetic, the collection factor, and the curiosity. They'll use it for a weekend and put it on a shelf.

That's also kind of fine. Not every product needs to be a daily driver. Some products can exist purely as novelties. The question is whether Nintendo is honest about that positioning.

If Nintendo positions the Virtual Boy as "here's a cool piece of hardware you can collect," that's one conversation. If they position it as "this is the next frontier in gaming," that's dishonest. The messaging seems to hover somewhere between the two.

Performance and Technical Specs

The hardware runs through your Switch or Switch 2, so processing power isn't a constraint. The optical performance is clean. Colors render without distortion. The 3D effect is noticeable when games are designed for it, subtle when they're not.

Frame rate consistency is solid. I didn't experience drops during testing. The lenses maintain focus across the visual field. Brightness can be adjusted to suit your preference and lighting conditions.

One technical limitation worth noting: the Virtual Boy only displays one color channel at a time. This is a heritage design choice that carries forward from the original. So games are monochromatic—red, blue, or green—rather than full RGB. Modern gamers used to color variety might find this restrictive. But it's also part of the device's identity. Changing it would undermine the aesthetic.

The stereoscopic depth perception works within the physical constraints of the lenses. Objects feel genuinely three-dimensional, not just layered. This is where the engineering actually shines. Creating believable depth on a small screen through optical design is harder than it sounds, and Nintendo got it right.

The Virtual Boy excels in aesthetic appeal and optical quality, with strong comfort and customization features. Estimated data based on review insights.

Who This Is Actually For

Let's be honest about the target audience here. This device isn't for casual gamers. It's not for people who play primarily on mobile or on modern consoles with deep game libraries.

The Virtual Boy peripheral is for:

Collectors. If you have an original Virtual Boy and its games, you already know you're spending money on artifacts. Adding the switch peripheral to that collection makes sense.

Nintendo historians and enthusiasts. People who care deeply about gaming history and want to experience pivotal (even if failed) moments in that history.

Content creators. YouTubers and streamers can definitely squeeze novelty value out of unboxing, reviewing, and playing with this thing. "Playing the worst Nintendo console ever on your Switch" is inherently entertaining to an audience.

Casual curiosity buyers. People with disposable income who see this in a store and think "that looks cool." They'll use it once, enjoy the experience, and move on.

For regular gamers looking for actual enjoyment? This isn't it. At least not yet. If Nintendo releases 50 Virtual Boy games and commits to the platform long-term, the value proposition changes. With 14 games that are mostly 25+ years old, there's no reason to recommend this to someone with limited discretionary spending.

The Broader VR Question

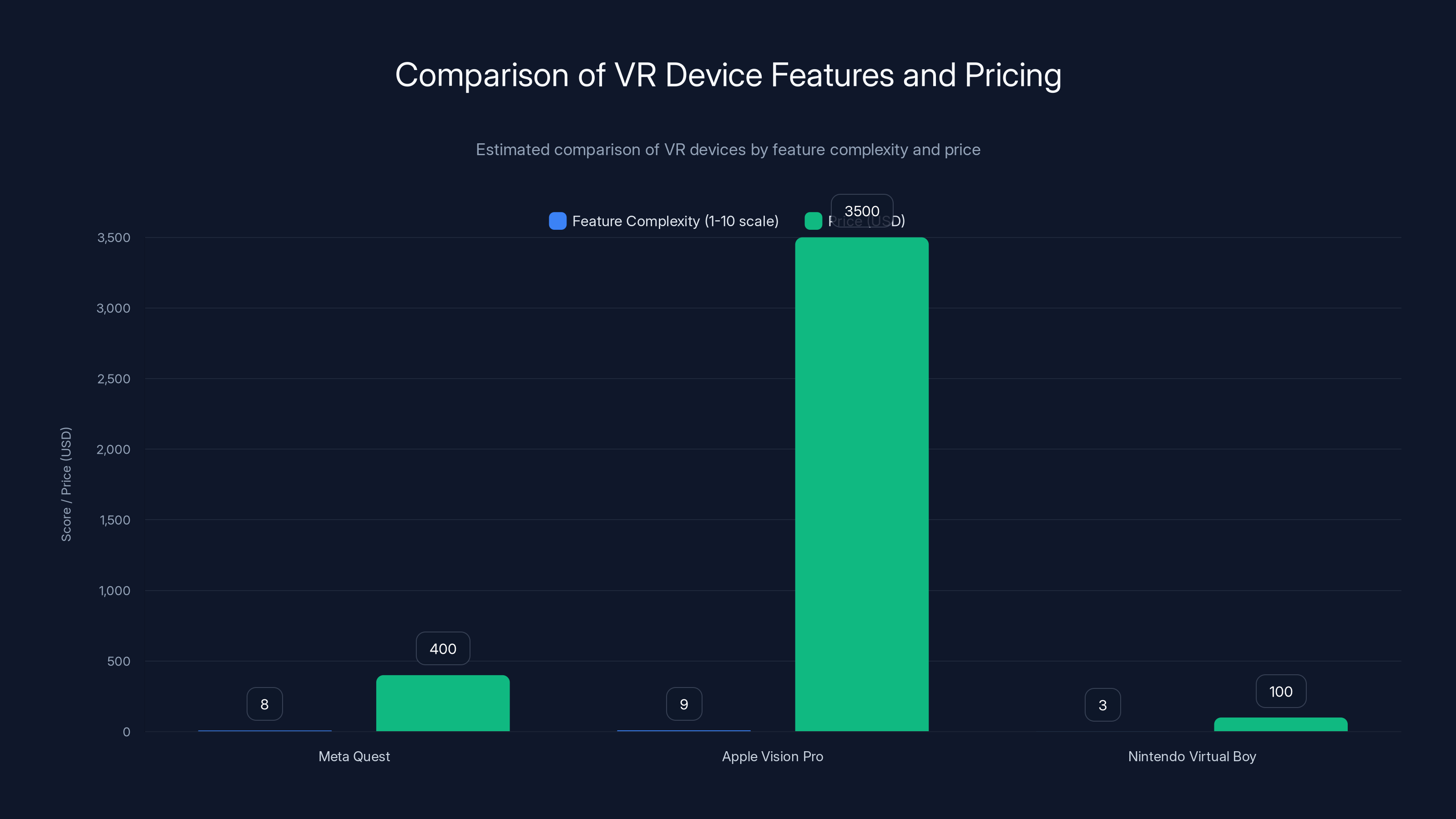

There's an interesting parallel happening in gaming right now. Meta is pushing aggressive VR development with Quest. Apple released the Vision Pro at

That positioning matters. Nintendo isn't trying to compete with cutting-edge VR. They're offering a retro-styled, limited-scope alternative that's infinitely more affordable. In a market where VR adoption has been slow despite massive corporate investment, Nintendo's approach is refreshingly humble.

The Virtual Boy peripheral acknowledges that full VR isn't necessary for depth perception gaming. You don't need hand tracking, inside-out tracking, or complex motion controllers. You need lenses and patience.

But that humility also becomes a limitation. Once you've experienced the device for an hour or two, you've experienced most of what it can offer. The technology doesn't evolve during gameplay. The games aren't designed to push the hardware. There's no progression or discovery.

Compare this to actual VR experiences like Half-Life: Alyx or Beat Saber, which are designed from the ground up to leverage VR's unique affordances. Those games are fundamentally different from their non-VR counterparts. The Virtual Boy games are just old games with depth added. That's not the same thing.

Software Expectations and Future Releases

Nintendo said "by the end of 2025" for all 14 games. That's oddly vague for a company that usually commits to specific release dates. It suggests the schedule isn't fully locked, or they want flexibility to delay if needed.

There's also zero commitment to post-launch titles. Nintendo could release 14 games in Q1 2025 and then completely abandon the platform. Or they could keep releasing at a pace of two games per quarter indefinitely. The lack of communication is revealing.

The company could accelerate this library dramatically if they wanted. Virtual Boy games are old. Emulation and porting technology is mature. Getting 50 games running on Switch in stereoscopic mode wouldn't be technically difficult. The constraint is purely business decision—whether Nintendo thinks the audience is large enough to justify the development effort.

Based on expected sales, the audience is probably smaller than Nintendo would like. Which means you shouldn't expect aggressive software support. You should expect a slow trickle of games as a low-priority project for the company.

That's not necessarily a death knell. Nintendo can make this work as a long-tail product. But it does mean expectations should be modest. This isn't the next big thing for Nintendo. It's an interesting side experiment that might eventually become a cult favorite.

The Meta Quest and Apple Vision Pro offer high feature complexity at higher prices, while Nintendo's Virtual Boy provides a simpler, more affordable option. (Estimated data)

Value Proposition Analysis

Let's do the math on whether this makes sense financially.

Best case scenario: You use the Virtual Boy for 50 hours across the year. Cost per hour:

Realistic scenario: You use the Virtual Boy for 5-10 hours total. You're paying $100 for a novelty. That's not great value. You could buy a new indie game that will give you more enjoyment for less money.

Worst case scenario: You buy it, use it once, and it sits in a drawer. $100 wasted. This is more likely than Nintendo would like to admit.

The subscription cost compounds the problem. If you don't already have Switch Online +, adding it specifically for Virtual Boy games costs an extra

This is where Nintendo's clever ecosystem design becomes a point of friction. The device exists within their walled garden. You can't easily move the games elsewhere. You can't own them permanently. You're renting access to a service.

Build Quality and Durability

One thing I should emphasize: the Virtual Boy feels well-built. The plastic is rigid, not flimsy. The lenses are properly seated. The dock mechanism has satisfying click to it. This isn't a cheap device constructed to fail after a year.

That said, VR headsets have failure modes that traditional hardware doesn't. Lenses can scratch or fog. Seals can degrade. Padding can flatten. The Virtual Boy peripheral is more durable than most cardboard VR solutions, but it's still an optical device with moving parts.

Nintendo's warranty situation is typical: one year of hardware coverage. If the lenses get scratched or the dock gets damaged after that point, you're buying a replacement. At $100 per unit, that's not a trivial repair cost.

The $25 cardboard version is even more fragile. It'll definitely show wear after six months of regular use. Creases, tears, and warping are inevitable. That's actually kind of fine—the price point expects that. But it's worth knowing that cardboard isn't a long-term solution.

The Design Philosophy Behind the Device

What's fascinating about the Virtual Boy peripheral is how it reveals Nintendo's current design thinking. The company is clearly willing to support multiple form factors, play with retro aesthetics, and commit hardware development to niche experiences.

That's different from Nintendo's approach in the 2000s, when the company was trying to expand the gaming audience with motion controls and casual gaming. The Virtual Boy represents a different bet: that hardcore gaming audiences care about variety, history, and experimental hardware.

Whether that bet pays off depends entirely on whether sufficient people decide a $100 novelty item is worth the shelf space and attention. My instinct says yes, but not in overwhelming numbers. The Virtual Boy will probably sell 200,000-500,000 units in its first year. Respectable for a niche product. Not impressive by Nintendo standards.

But Nintendo seems okay with that. They're not trying to replace the Switch with the Virtual Boy. They're not even trying to make it a primary platform. They're creating an optional experience for people curious about where gaming came from and how perception of depth changes play.

That's honest design philosophy, even if it's not going to be for everyone.

Why the Original Failed (And Why This Won't)

Understanding why the original Virtual Boy failed in 1995 is essential context for why this peripheral might actually work in 2025.

The original Virtual Boy was a complete system. It cost $180, had no games at launch, and required committed investment. Nintendo was asking consumers to buy unfamiliar hardware for a new type of game experience without proof that the experience would be better than existing alternatives. Most people said no.

The 2025 Virtual Boy is a $100 add-on for hardware you probably already own. The barrier to entry is infinitely lower. You already know what Nintendo is. You already have a Switch. Adding a peripheral is low-risk experimentation.

Also, the cultural context is completely different. VR is now normalized in consumer consciousness. People understand stereoscopic 3D from movie theaters and phone VR experiments. The technology isn't mysterious. It's familiar. That familiarity removes the friction that killed the original device.

Does that mean the peripheral will succeed where the original failed? Not necessarily. It still has fundamental limitations as a gaming platform. But it removes the primary barrier that destroyed the original: the requirement to commit to a completely unfamiliar system.

The Honest Review

Here's my actual take after two hours with this device: it's a well-engineered piece of hardware that solves a problem nobody has. The plastic feels nice. The optical quality is clean. The stereoscopic depth is genuine and sometimes impressive.

But the games are tired. The library is anemic. And once you've experienced what the device can do, you've experienced most of what's interesting about it. There's no progression. There's no surprise. There's no reason to come back after the novelty wears off.

I'd recommend the Virtual Boy peripheral to exactly three groups of people: Nintendo collectors, content creators, and people who explicitly want a piece of gaming history. I'd recommend it to nobody else.

Is that unfair to the product? Maybe. The original Virtual Boy deserves credit for attempting something technically ambitious in 1995. This peripheral deserves credit for revisiting that vision with more maturity and better engineering. But credit for trying is different from credit for succeeding.

Nintendo tried. The peripheral is legitimately well-made. The implementation is thoughtful. But none of that changes the core reality: there just isn't enough compelling software to justify the investment for most gamers.

That's not a fatal flaw. It's just honest context for anyone considering the purchase.

FAQ

What is the Nintendo Virtual Boy peripheral?

The Virtual Boy is a $100 stereoscopic 3D headset accessory for the Nintendo Switch that displays classic Virtual Boy games in three dimensions. Unlike the original 1995 Virtual Boy console, this version is a peripheral that attaches to your Switch or Switch 2 and requires Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack subscription to access its game library.

How does the Virtual Boy peripheral work?

You insert your Switch or Switch 2 into a dock at the front of the headset, position the device against your face, and play using a standard controller. Specialized lenses create stereoscopic depth perception by displaying slightly offset images to each eye, simulating three-dimensional space. The device creates total darkness around the display, which enhances the illusion of depth.

What games are available for the Virtual Boy?

Nintendo released five games initially (Galactic Pinball, Teleroboxer, Mario's Tennis, Mario's Game Gallery, and The Mansion of Innsmouth), with plans to release 14 total games by the end of 2025 through Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack. No additional games beyond that commitment have been announced.

Is the Virtual Boy peripheral comfortable to wear?

Yes, the Virtual Boy is surprisingly comfortable compared to most VR headsets. It distributes weight across your face rather than clamping around your head, includes adequate padding, and doesn't typically cause headaches or eye strain. That said, comfort is subjective—some users may find it less accommodating.

How much does the Virtual Boy cost?

The plastic Virtual Boy headset costs

Is the Virtual Boy worth buying?

That depends on your interests. For Nintendo collectors, content creators, or people specifically interested in gaming history, yes—the device is well-engineered and offers a unique experience. For casual gamers looking for compelling software, probably not. The game library is limited (14 games by year-end), and most are 25+ years old without significant modern updates. The value proposition is better if you already subscribe to Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack.

What's the difference between the plastic and cardboard Virtual Boy?

Both versions use identical lenses and optical designs. The main differences are material durability and aesthetics. The plastic version (

Can I use the Virtual Boy with original Virtual Boy cartridges?

No. The peripheral only works with games available through Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack. It cannot read original Virtual Boy cartridges and includes no traditional cartridge slot. All games must be downloaded through the subscription service.

How is the stereoscopic 3D effect?

The 3D effect is noticeable and creates genuine depth perception without distortion. The quality depends on the specific game—some titles leverage stereoscopic depth effectively (like Teleroboxer), while others add depth without meaningful gameplay changes (like Mario's Tennis). Most users report the effect is impressive initially but becomes less remarkable after an hour of use.

Will there be more Virtual Boy games released after 2025?

Nintendo has only committed to releasing 14 games by the end of 2025. No announcement has been made regarding post-2025 support. Given the niche nature of the product and limited initial library, additional games will likely come slowly, if at all.

The Bottom Line

The Virtual Boy peripheral represents Nintendo at its most confident and experimental. The company resurrected one of its biggest failures, engineered it better, and positioned it as an optional accessory rather than a required platform. That's thoughtful product strategy.

But thoughtful strategy doesn't automatically translate to compelling entertainment. The Virtual Boy peripheral is a beautiful museum piece masquerading as a modern gaming device. For most people, looking at it will be more fun than playing it. And that's genuinely fine—not every product needs to serve everyone.

Key Takeaways

- The Virtual Boy peripheral is expertly engineered hardware with comfortable fit, clean optical quality, and genuine stereoscopic 3D depth perception

- Limited game library of 14 aging titles by year-end 2025 lacks compelling modern gameplay, making the $100 investment difficult to justify for casual gamers

- Total cost of ownership extends beyond 50-80 annual Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack subscription requirement

- Target audience is primarily collectors, Nintendo historians, and content creators—not mainstream gamers looking for substantial entertainment value

- The $25 cardboard Labo variant offers identical optical technology at lower cost but sacrifices durability, making it better for experimental users

Related Articles

- Nintendo Switch 2's Virtual Boy: A 30-Year Legacy Reimagined [2025]

- Abxylute N9C Switch 2 GameCube Controller: Design, Features & Review [2025]

- GameCube Games Leaked for Nintendo Switch Online [2025]

- Anbernic RG G01 Gamepad: A Screen, Heart Rate Sensor & Gaming Innovation [2025]

- Nintendo Switch 2's GameCube Library: Why It's Missing the Console's Best Games [2025]

- Joy-Con 2 Color Variants: Light Purple and Green Coming [2025]

![Nintendo's Virtual Boy Switch Peripheral: Design Triumph, Gameplay Struggle [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nintendo-s-virtual-boy-switch-peripheral-design-triumph-game/image-1-1770242855059.png)