How America's Official Time Source Nearly Failed the Internet

You probably didn't notice it last month, but somewhere in Boulder, Colorado, the heartbeat of the internet skipped. Not dramatically. Not catastrophically. Just a tiny, almost imperceptible drift—about four microseconds. But that's the whole problem. When you're running systems that depend on atomic precision, four microseconds is enough to break things in ways most people never think about.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology operates the atomic clocks that define America's official time. These aren't ordinary clocks. They're cesium-based instruments so accurate they lose only one second every 300 million years. Everything downstream of them—your bank transactions, power grid synchronization, military communications, the entire synchronized backbone of modern infrastructure—trusts these clocks to be right.

On a day marked by high winds and power line damage, the backup systems at NIST's Boulder facility failed in a way that exposed something troubling: our most critical infrastructure can silently serve wrong information while appearing to work perfectly.

The Outage That Broke Nothing (But Could Have)

Let me be clear about what happened. A utility power outage knocked out primary power at the Boulder campus. Fair enough. Backup generators kicked in. That's what they're supposed to do. But here's where it gets weird: the generator downstream from the atomic clock systems failed. Not catastrophically exploded. Just failed quietly enough that the time servers kept running, kept responding to requests, kept appearing to work normally. Except they weren't referencing the atomic standard anymore.

Think of it like a car that's mechanically running but has no GPS signal. The engine sounds fine. The dashboard lights are all green. But you're navigating blind, and you don't realize it until you're completely lost.

NIST confirmed that the UTC(NIST) signal—that's Coordinated Universal Time maintained by their atomic standard—drifted by roughly four microseconds. That's four millionths of a second. For most people, this is meaninglessly small. For systems that depend on nanosecond-level precision, it's a catastrophe waiting to happen.

The really troubling part? The servers stayed online. They continued responding to network time protocol requests. They just served inaccurate timestamps. Some administrators relying on those specific NIST servers—particularly anyone hard-coding individual time-x-b.nist.gov addresses instead of using the round-robin distributed system—would have been silently feeding wrong time into their systems without any warning.

This is the kind of failure that doesn't announce itself. Your monitoring dashboards wouldn't light up red. Your alerts wouldn't fire. The server would keep pinging back with a response. It just wouldn't be right.

Why This Matters: The Time Dependency Chain

Here's what most people don't understand about timekeeping at scale: everything is stacked on top of it. It's not just about knowing whether it's noon or one o'clock.

Telecommunications networks use precise timing to synchronize voice calls and data streams across continents. If the timing drifts, packets get out of order, connections drop. Power grids depend on synchronized timing to balance load across different regions. If power stations aren't perfectly synchronized—down to microseconds—you get cascade failures and blackouts. Financial systems timestamp every transaction. If timestamps aren't synchronized, you can't determine whether Trade A happened before Trade B, which fundamentally breaks market integrity.

Data centers run thousands of servers. Those servers need to log events in proper temporal order. If they don't, you can't debug production incidents, you can't audit security logs, you can't prove when things happened. Scientific research depends on synchronized timing. Particle physics experiments, astronomical observations, gravitational wave detection—all of these require nanosecond-level synchronization across instruments.

The NIST-F4 atomic clock at Boulder is the actual reference. It doesn't just sit there ticking perfectly. It's the definition against which everything else gets measured. When it's offline or drifting, the entire distributed time system upstream of it slowly loses accuracy.

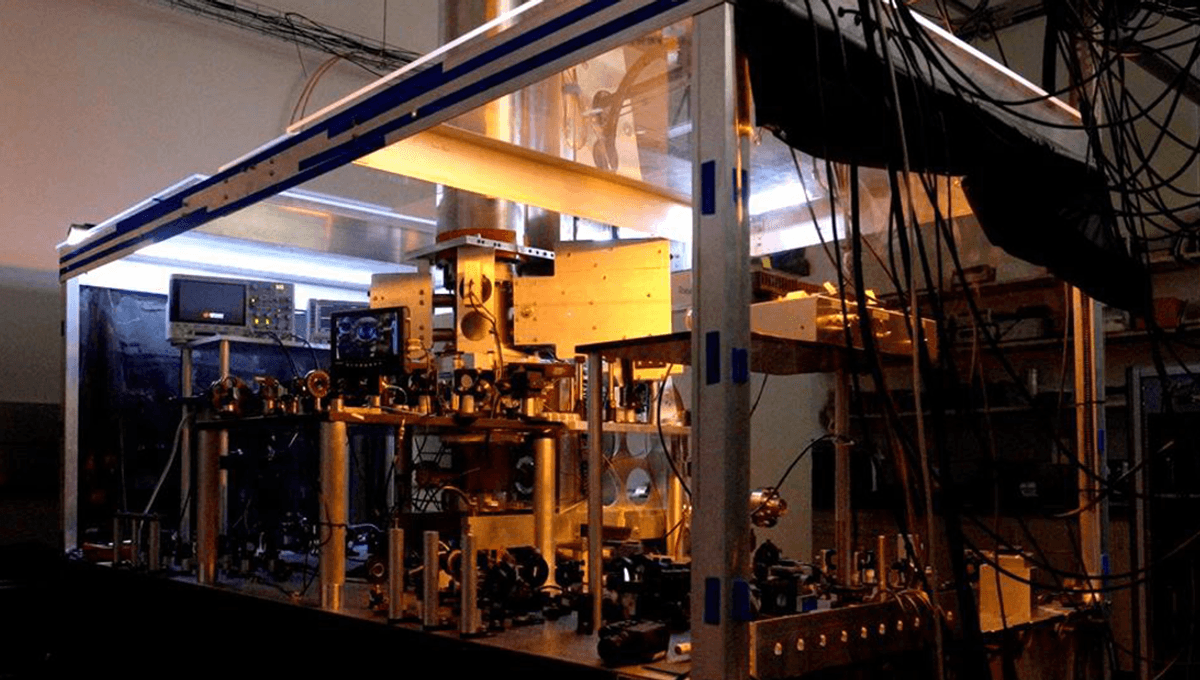

The Boulder Facility: Where Precision Lives

The Boulder, Colorado campus isn't some dusty old facility. It's a state-of-the-art laboratory where some of the most precise measurements in human history happen. The NIST-F4 atomic clock is one of the most accurate timekeeping devices ever built. It uses cesium atoms oscillating at 9,192,631,770 cycles per second to define the length of a second itself.

This is the atomic standard that international timekeeping bodies use. When the International Bureau of Weights and Measures calculates Coordinated Universal Time, they're comparing measurements from NIST's Boulder facility along with other national labs around the world. The U. S. atomic clock doesn't just keep American time accurate. It contributes to global timekeeping.

The Boulder facility sits on a power grid served by local utilities. On the day in question, high winds damaged power lines in the area, triggering safety-related shutdowns. The facility has backup power systems. Generators are sitting there ready to kick in. But the generator that serves the atomic clock distribution system failed—creating a situation where everything else kept running, but the actual time reference started drifting.

NIST engineers are still working on full restoration. They haven't given a firm timeline. That's actually worse from a security standpoint than a total outage would be. With a total outage, every system administrator would know something was wrong. With a drifting system that keeps responding, some systems might not realize they're using wrong time for hours or days.

Round Robin DNS: The Unsung Hero That Actually Worked

You know what saved millions of people from time synchronization disasters? An engineering pattern that's almost boring in how routine it is: round robin DNS.

NIST doesn't run a single time.nist.gov server sitting in one location. Instead, they distribute multiple time servers across different geographic locations. When you request the address time.nist.gov, the DNS system automatically routes you to one of several servers. If one location goes down, or in this case, starts serving inaccurate time, most users automatically get routed to a different, working location.

This is why most consumer systems and many enterprise systems were protected. They weren't directly tied to the Boulder facility. They were hitting the distributed pool, which automatically failed over.

But here's where the exposure lived: users who had hard-coded specific hostnames like time-x-b.nist.gov in their configuration were directly pointing to Boulder. Those systems kept getting wrong time without any fallback. If an administrator had set up their data center to sync specifically to that Boulder address because it was "local" or because they'd read it was the "official" source, they were now silently feeding incorrect time into their entire infrastructure.

The Boulder facility hosts multiple NIST time service endpoints. The advisory that NIST issued specifically called out the affected hosts: the time-x-b.nist.gov addresses and the authenticated ntp-b.nist.gov service. Not time.nist.gov itself—that's the round-robin version. If you were using that, you were mostly fine.

This is a critical lesson in infrastructure design. Single points of failure are dangerous. But single points of failure that keep appearing to work while serving wrong data are worse.

What About Enterprise Infrastructure?

Enterprise data centers operate under different constraints than cloud platforms. A large bank or insurance company might run thousands of servers. Those servers need synchronized time. Some of them are using cloud services. Some are running on-premises. Some are hybrid.

Many enterprises configure their own Network Time Protocol servers. They point those servers to authoritative sources like NIST. They then point all their internal systems to their own NTP servers. This creates a hierarchy: authoritative source (NIST) → corporate NTP servers → individual systems.

When something goes wrong at the top of that chain, you're only as accurate as your last synchronization. If your corporate NTP server last synced to NIST and got a wrong time five minutes before the outage, your entire infrastructure is operating on that stale, wrong time. Some systems have built-in checks that refuse to update time by more than a certain amount. Others just accept whatever the NTP server tells them.

The real danger is in systems that depend on consistent time but don't actively monitor that the time they're getting is reasonable. A security system that logs access events depends on time being correct. If time is wrong, your audit trail is wrong. A transaction ordering system assumes time flows forward. If time suddenly jumps backward, weird things happen.

Cloud-native systems actually handle this better. AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure all run their own synchronized time infrastructure and don't rely on external time sources as heavily. They're more resistant to this kind of failure.

The Gaithersburg Incident: This Wasn't The First Time

Here's something that should concern you: the Boulder outage wasn't even the worst time service disruption NIST has had recently.

Earlier in the same month, NIST's Gaithersburg, Maryland facility experienced another time service disruption. This one caused a larger time step error measured in milliseconds, not microseconds. Milliseconds. That's a thousand times worse than the Boulder drift.

Two major NIST facilities, two time-related incidents in the same month. That's not a coincidence. It's a pattern. And it suggests that whatever is causing these problems might be systematic.

The Gaithersburg facility also hosts critical atomic clock infrastructure. When it went down, the same issues emerged: the Internet Time Service was disrupted. Some time servers continued responding while serving inaccurate data. The same fundamental problem: systems that look like they're working but aren't.

How Time Works on the Internet: The Protocol Level

Network Time Protocol—NTP—is how systems keep time synchronized across the internet. It's been around since the 1980s, and despite being ancient by internet standards, it's still the global standard.

Here's how it works at the simplest level: your system asks an NTP server "what time is it?" The server responds with a timestamp. Your system adjusts its local clock. Done.

Of course, it's more sophisticated than that. NTP accounts for network latency. It uses multiple servers and picks the most reliable one. It has built-in checks for sanity. If a server says the time is currently 1952, NTP will probably reject that because it's clearly wrong.

But NTP has limits. It assumes the servers it's talking to are telling the truth. If they're silently serving wrong time, NTP will synchronize to that wrong time. It trusts the source.

There's a newer protocol called NTPv 4, and work is ongoing on NTPv 5. These are more sophisticated. But adoption is slow. Most systems are still using older versions.

The really critical systems—the ones where millisecond-level accuracy matters—often use more exotic timing methods. GPS receivers that lock onto satellite signals. Atomic clocks. Specialized hardware with redundant references. The more critical your timing requirements, the more exotic and expensive your solution.

The Security Implications Nobody Talks About

There's a security angle to this that doesn't get enough attention.

Cryptographic systems depend on accurate time. Certificate-based authentication systems use time to validate whether a certificate is currently valid or has expired. If your system's time is wrong, you might accept an expired certificate or reject a valid one.

OAuth tokens, JWT tokens, and other temporary credentials depend on time. They're valid for a specific duration. If the time is wrong, the token validity window is wrong. You might accept a token that should have expired, or reject one that's still valid.

Two-factor authentication systems use time-based one-time passwords. If your phone's time is out of sync with the server's time, you can't log in. More importantly, if the server's time is wrong, the password window is wrong.

Now imagine a scenario where an attacker can manipulate time for specific systems. They could make certificate expirations seem valid when they're not. They could make tokens seem fresh when they're stale. They could create windows of time where authentication checks fail.

NIST serves government clients, financial institutions, and critical infrastructure operators. If those systems are silently running on wrong time, the security implications are real. Not theoretical. Real.

The fact that the time servers continued responding while serving wrong data makes this worse. An administrator might not realize their systems are out of sync. They might think they're secure when they're not.

Why Backup Power Systems Failed

NIST has backup power. This is a facility running atomic clocks. Of course it has backup power. But backup systems can fail. They do fail. And when they do, the failures can cascade in unexpected ways.

On the day of the outage, high winds damaged local power lines. This triggered automatic safety shutdowns in the facility. Backup generators were supposed to kick in. They did. But the generator that serves the atomic clock distribution system had a downstream failure. The cause of that failure hasn't been publicly detailed, but it meant that the atomic clock equipment kept running—they have their own backup power—but the distribution infrastructure that feeds time to the internet services went offline.

This created an asymmetry: the atomic clocks themselves stayed accurate, but the systems that distribute that accuracy to the internet lost their power reference and started drifting.

Backup systems introduce their own complexity. You need generators. You need fuel. You need automatic switchover systems. You need monitoring to know when switchover happened. You need maintenance and testing. All of these are failure points. And they often fail in non-obvious ways.

Large data centers that run critical infrastructure usually have multiple backup power sources: UPS systems, diesel generators, sometimes even natural gas turbines. They test them regularly. They have monitoring. When one fails, others take over. But even with redundancy, sometimes multiple failures cascade.

The Cloud Advantage: Why Cloud Platforms Didn't Break

Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure—these platforms have their own time synchronization infrastructure. They don't rely on external time sources the way traditional data centers do.

They run atomic clocks in data centers. Not cesium clocks like NIST uses, but high-precision quartz oscillators and GPS-disciplined clocks. These are synchronized across multiple data centers. If one facility's time drifts, the system detects it and fails over to other sources.

Cloud platforms also have built-in time sync at the hypervisor level. Virtual machines running on cloud infrastructure get synchronized time from the host system. This abstraction means application developers usually don't have to think about timekeeping. It just works.

This is one of the reasons cloud adoption has been so successful in enterprises. It abstracts away a lot of infrastructure complexity that's easy to get wrong. Time synchronization is one of those things that's trivial until it isn't, and then it's catastrophic.

How to Know If Your Systems Were Affected

If you run infrastructure that depends on external time sources, here's how to know if the NIST outage affected you:

First, check your NTP configuration. Look for any explicit references to NIST time servers. Specifically, look for time-x-b.nist.gov or ntp-b.nist.gov addresses. If you have those hard-coded in your configuration, you were potentially affected.

Second, check your monitoring logs during the time of the outage. Look for time jumps or unusual time behavior in your systems. If your logs show that your system's time drifted during the outage window, that's evidence you were pulling time from the affected servers.

Third, validate your current time against multiple independent sources. Your system should be correct now, but if it's still off, that indicates a persistent problem.

Fourth, review your backup time sources. If you're only using one NTP server, you have a single point of failure. Use at least three independent sources. Prefer public NTP pools that distribute across multiple servers.

Building Resilient Time Infrastructure

If this incident has taught anything, it's that you can't assume external time sources are always reliable. Even NIST, the official source, had a failure.

Here's how to build time infrastructure that can survive failures:

Use multiple independent time sources. Don't hard-code a single server address. Use NTP pools that distribute across many servers. If one fails, you automatically fall back to others.

Monitor time drift independently. Don't just assume your NTP source is correct. Monitor the time reported by your system against a completely independent reference. This could be a GPS receiver, a local atomic clock, or a different external time service. If drift exceeds your threshold, alert and investigate.

Implement time sync validation at the application level. Don't just rely on the operating system to handle it. Applications that care about time should validate that the time they receive is sane. Check for backward time jumps. Check for unreasonably large forward jumps. If something looks wrong, fail safe.

Use redundant time hardware. If you run a data center, consider GPS-disciplined clocks in addition to NTP. GPS satellites have atomic clocks. If you can receive the signal, you have a direct reference. It's radiation-hardened and military-grade reliable.

Version your NTP pool carefully. NTP has multiple versions. Newer versions are better in most ways, but adoption is slow. Make sure you're using versions that your entire infrastructure understands. Mixed versions can sometimes cause synchronization issues.

The Global Timekeeping System and National Redundancy

America's official time isn't just maintained at NIST. There are backup systems. NIST operates multiple facilities. The U. S. Naval Observatory also maintains atomic clocks. There are commercial time service providers.

But the real redundancy is global. The International Bureau of Weights and Measures in France coordinates Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) by averaging atomic clock measurements from national laboratories around the world. The U. S. contributes to this. So does the U. K., France, Germany, Japan, and dozens of other countries.

If NIST's clocks went completely offline, UTC would still exist, maintained by measurements from other national laboratories. The U. S. would lose its primary reference, but the global system would continue.

This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength because it means there's global redundancy. A weakness because if you depend on a specific national laboratory's time, and that lab goes down, you need to have fallback procedures.

Many countries are investing in more robust timekeeping systems. The European Union has Galileo satellites with atomic clocks. China has launched Bei Dou, which also includes precision timing. India has Nav IC. These are global navigation systems, primarily, but they all carry atomic clocks and can serve as timing references.

The future of timekeeping might be more distributed and decentralized. Instead of relying on a single national laboratory, systems might pull timing from multiple satellite systems, multiple ground-based references, and have sophisticated algorithms to detect and reject false information.

What NIST Should Have Done (And What They Might Do Now)

Looking back at the outage, there are some obvious improvements that could have prevented or mitigated the issue:

Separate power infrastructure for distribution systems. The atomic clocks had backup power. The distribution systems didn't, or the backup failed. These should be on completely independent power grids, with independent UPS and generator systems. If one fails, the other keeps running.

Better monitoring and alerting. NIST should have caught the time drift immediately and alerted customers. It's not clear how quickly the drift was detected. The alert should go out the moment the atomic reference signal is lost, not after discovering that time is drifting.

Automatic failover for distribution servers. If a time server detects that it's no longer referenced to atomic time, it should automatically take itself offline or indicate in its response that it's not a reliable source. Don't silently serve wrong time.

Redundant atomic clocks within the facility. NIST-F4 is the primary. But there should be a secondary cesium clock that takes over if the primary is offline. The time wouldn't change—two cesium clocks agree—but the distribution would continue.

Faster recovery procedures. The outage happened. Recovery is ongoing. Having a documented, tested recovery procedure that takes minutes instead of days would reduce exposure.

Some of these might already be in progress. NIST hasn't released detailed information about lessons learned or changes being made. But for a facility this critical, continuous improvement should be standard practice.

Consumer Impact: Why You Probably Didn't Notice

You're probably reading this and wondering if this affected you personally. The honest answer is probably not.

Consumer devices—phones, computers, smart home devices—usually sync time with multiple sources. Your phone syncs with cell tower time and with NTP pools. Your computer syncs with internet-based time sources. These systems are designed to be robust against single failures.

Browsers and web services depend on time, but they have tolerance for small deviations. A few microseconds doesn't matter for most applications.

The services that really care about precision—financial systems, scientific equipment, power grids, military communications—have more sophisticated time infrastructure. They have redundancy. They have monitoring. They're not directly exposed to every NIST outage.

But here's the thing: that same reasoning makes us complacent. We assume everything is fine because consumer impact is limited. Meanwhile, we're slowly realizing that critical infrastructure has single points of failure that we thought were redundant.

The more insidious problem is systems that were affected but didn't realize it. A data center that was pulling time from one of the affected NIST servers might have been running on wrong time for hours. Their monitoring and logging would all be timestamped wrong. If an incident occurred during that window, investigating it becomes difficult because the timeline is wrong.

The Larger Problem: Hidden Dependencies

This incident exposes something that's becoming more obvious: we have hidden dependencies on infrastructure we don't fully understand.

Most organizations don't think much about time synchronization until it breaks. And when it breaks, it breaks in weird ways that are hard to diagnose. Systems keep running. Services keep responding. But the foundation beneath them is wrong.

This is similar to the broader problem of infrastructure fragility. We've built incredibly complex systems that are sensitive to small deviations in foundational services. A DNS outage breaks everything that depends on DNS. A time outage breaks everything that depends on timing.

And we've optimized for cost and efficiency, not for robustness. Having multiple redundant time sources, multiple backup power systems, multiple geographic locations—that all costs money. So we do the minimum: primary service plus one backup.

Then we're surprised when that one backup fails.

Lessons for Infrastructure Reliability

If you run any infrastructure that depends on external services, this incident teaches some hard lessons:

Understand your dependencies. Know what your systems depend on. Not just directly, but transitively. If you depend on a time service, what does that time service depend on? If you depend on a DNS resolver, what does it depend on? Map the dependency graph. Identify single points of failure.

Diversify your sources. Use multiple independent sources for critical services. Don't have a primary and a backup from the same vendor. Use different vendors, different geographic locations, different technologies.

Monitor at multiple levels. Monitor your own systems. Monitor your immediate dependencies. Monitor the dependencies of your dependencies. If something at the edge of your control system changes, you want to know immediately, not when users start complaining.

Test your redundancy. Don't just have backups. Test them regularly. And test under realistic conditions. If your backup generator has never actually powered your critical systems, it won't work when you need it.

Build in detection for silent failures. The worst failures are the ones that don't announce themselves. A server that goes completely offline is obvious. A server that serves wrong data silently is a nightmare. Build in checks: are my dependencies returning sane data? Are the responses internally consistent? Do multiple independent queries agree?

Have procedures for degraded operation. When something fails, what do you do? Do you have documented procedures? Have you practiced them? Can you recover in minutes or hours, not days?

The Future of Timekeeping Infrastructure

There are hints that timekeeping infrastructure is evolving.

Morecas are developing more sophisticated time protocols that are resistant to attacks and failures. These protocols explicitly assume that some time sources are untrustworthy and use Byzantine fault tolerance to determine consensus time.

Satellite systems like Galileo, Bei Dou, and GPS are becoming more redundant and more precise. In the future, getting accurate time might not require any centralized facility. You'd just query multiple satellite systems and let them vote.

Some researchers are investigating quantum timekeeping. Using quantum mechanics principles, you can potentially create even more precise time references. This is still experimental, but it's the direction the field is moving.

The NIST incident might actually accelerate some of these developments. When the official national time source fails, even slightly, it raises questions about whether we're building this system robustly enough.

What to Do If You Manage Infrastructure

If you run systems that depend on time:

Immediately audit your NTP configuration. Look for hard-coded references to specific NIST servers, particularly the time-x-b.nist.gov addresses. Replace those with references to NTP pools that distribute across multiple servers.

Check your logs for time drift during the outage window. If your systems experienced time jumps, that's evidence you were affected. Plan to replace whatever time source was causing the problem.

Set up monitoring for time drift. Your systems should monitor their own time against multiple independent sources and alert if drift exceeds thresholds. Automate this. Don't rely on manual checks.

Document your critical time dependencies. What systems absolutely need correct time? What will happen if time is wrong? What's your tolerance for drift? Answer these questions and build redundancy accordingly.

Test your backup time sources. If you have GPS receivers, make sure they work. If you have multiple NTP servers, make sure all of them are actually being consulted and that failover works. Don't just assume it works.

Consider building local time infrastructure. If you have critical timing requirements, consider maintaining your own atomic clocks or GPS-disciplined clocks rather than relying entirely on external sources. It's expensive, but for the most critical systems, it might be worth it.

FAQ

What is NIST and why does their atomic time matter?

The National Institute of Standards and Technology maintains America's official atomic time using cesium-based clocks that are accurate to within one second every 300 million years. This time standard feeds the Internet Time Service, which keeps the global internet synchronized. Financial systems, power grids, telecommunications networks, and scientific research all depend on this official time source to stay in sync.

How did the power outage cause time servers to serve wrong data?

During high winds that damaged local power lines, a generator failure disrupted the atomic time distribution systems at NIST's Boulder facility. While the atomic clocks themselves remained accurate due to backup power, the systems that distribute this time to internet servers lost their reference signal. The servers continued running and responding to time requests, but without the atomic reference, they started drifting and serving inaccurate timestamps.

Why didn't everyone notice the time drift if it lasted for hours?

Most internet systems use round-robin DNS and geographically distributed time servers, which automatically routed requests away from the affected Boulder facility to working servers elsewhere. Only systems that had hard-coded specific NIST server addresses like time-x-b.nist.gov continued pulling time from Boulder and received inaccurate data without any alert or indication of the problem.

How much did time actually drift, and does four microseconds really matter?

The atomic time drifted by approximately four microseconds, which is four millionths of a second. For most consumer applications, this is imperceptibly small. However, for high-frequency financial trading systems that execute thousands of transactions per microsecond, or for scientific equipment requiring nanosecond-level precision, this drift can cause serious ordering problems and transaction errors.

What systems are most vulnerable to time source failures like this?

Enterprise data centers that hard-code specific authoritative time server addresses rather than using distributed pools are most vulnerable. Cloud-native systems are more resilient because they use multiple independent time sources and don't rely on external references as heavily. Systems requiring high-precision timing, including financial trading platforms, power grid management, military communications, and scientific research equipment, are also more exposed.

How can organizations protect themselves from similar outages?

Organizations should use multiple independent NTP sources rather than hard-coding single server addresses, implement independent time drift monitoring against multiple reference sources, test backup time infrastructure regularly under realistic conditions, and maintain geographic redundancy in time sources. For mission-critical systems, maintaining local atomic clocks or GPS-disciplined oscillators provides protection against failures in external time services.

Has NIST had other time service failures recently?

Yes. Earlier in the same month, the Gaithersburg, Maryland facility experienced another disruption that caused a time step error measured in milliseconds, which is significantly worse than the microsecond-level drift in Boulder. Two major NIST facilities experiencing time-related incidents within weeks suggests potential systematic issues with how time distribution is handled across their infrastructure.

What is round-robin DNS and how did it protect against this outage?

Round-robin DNS distributes requests across multiple servers by cycling through different IP addresses. When you request time.nist.gov, the DNS system automatically routes your request to one of several distributed servers. If one location fails or serves bad data, most clients automatically get routed to different, working locations. This automatic failover is why most users weren't affected by the Boulder outage.

Could this type of outage affect cybersecurity systems like certificate validation?

Yes. Certificate-based authentication, OAuth tokens, JWT credentials, and two-factor authentication all depend on accurate time. If systems silently run on wrong time without realizing it, they could accept expired credentials as valid or reject current credentials as expired, potentially creating security vulnerabilities. Time drift of even a few seconds can break authentication windows.

What should I do if I suspect my infrastructure was affected by this outage?

Audit your NTP configuration for hard-coded references to specific NIST servers, particularly time-x-b.nist.gov addresses. Check your system logs for unusual time behavior during the outage window. Validate your current time against multiple independent sources. Replace any single-source time dependencies with multi-source NTP pools. Set up ongoing monitoring to detect future time drift before it causes problems.

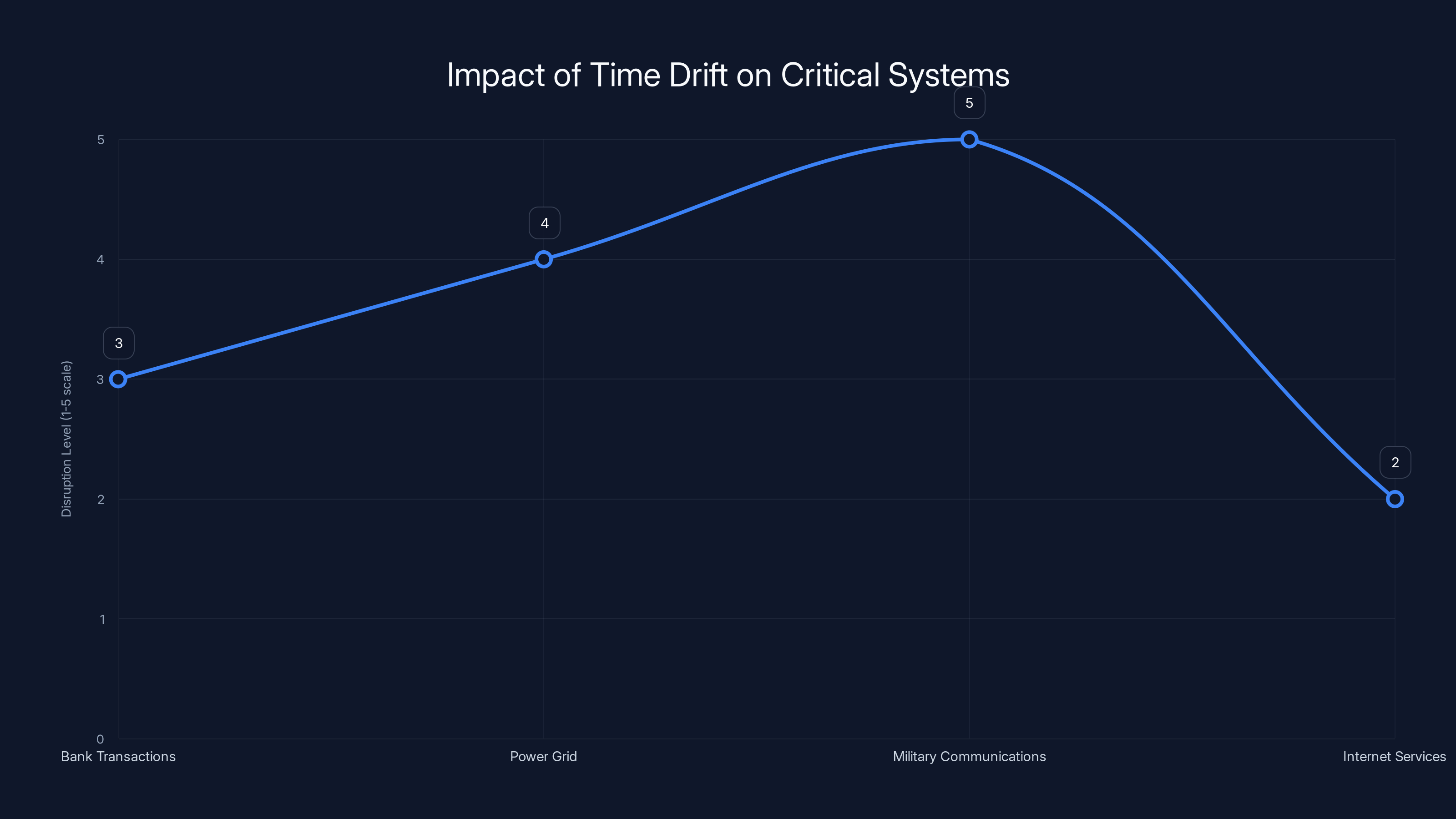

A 4 microsecond drift in atomic time could cause varying levels of disruption across critical systems, with military communications being most affected. Estimated data.

Conclusion: Why This Matters More Than You Think

A four-microsecond drift in atomic time doesn't sound dramatic. But it revealed something important about how we've built critical infrastructure: we've optimized for efficiency and cost, not robustness.

NIST is supposed to be the single source of truth for American timekeeping. It's the reference that everything else synchronizes against. When it drifts, even slightly, the entire downstream ecosystem becomes slightly less accurate. Most people never notice. But the systems that depend on precision absolutely do.

What's more troubling is that this wasn't an isolated incident. The Gaithersburg facility had a more serious time disruption in the same month. Two major NIST facilities, two time-related failures. That's not random. That suggests something systematic needs to change in how they maintain and back up their atomic time infrastructure.

For organizations managing any kind of infrastructure that depends on time, this is a wake-up call. Audit your time sources. Don't assume that distributed systems will protect you if you've hard-coded dependencies into configuration. Test your backups. Monitor for drift. Have procedures for detecting when time goes wrong.

Because time is one of those things that's invisible until it breaks. Your systems will keep running. They'll keep responding. But they'll be serving wrong information, and you might not realize it until something catastrophic happens.

The internet runs on seconds. Literally. Everything is timestamped, everything is ordered by time, everything depends on the assumption that time flows forward consistently. When that assumption breaks—even silently, even slightly—the whole system becomes fragile in ways that aren't obvious until they fail.

NIST will recover. The systems will be fixed. Life will go on. But the real question is whether this incident will drive the systemic changes in redundancy and monitoring that critical infrastructure actually needs.

Based on past incidents, I'm not optimistic. But I hope I'm wrong.

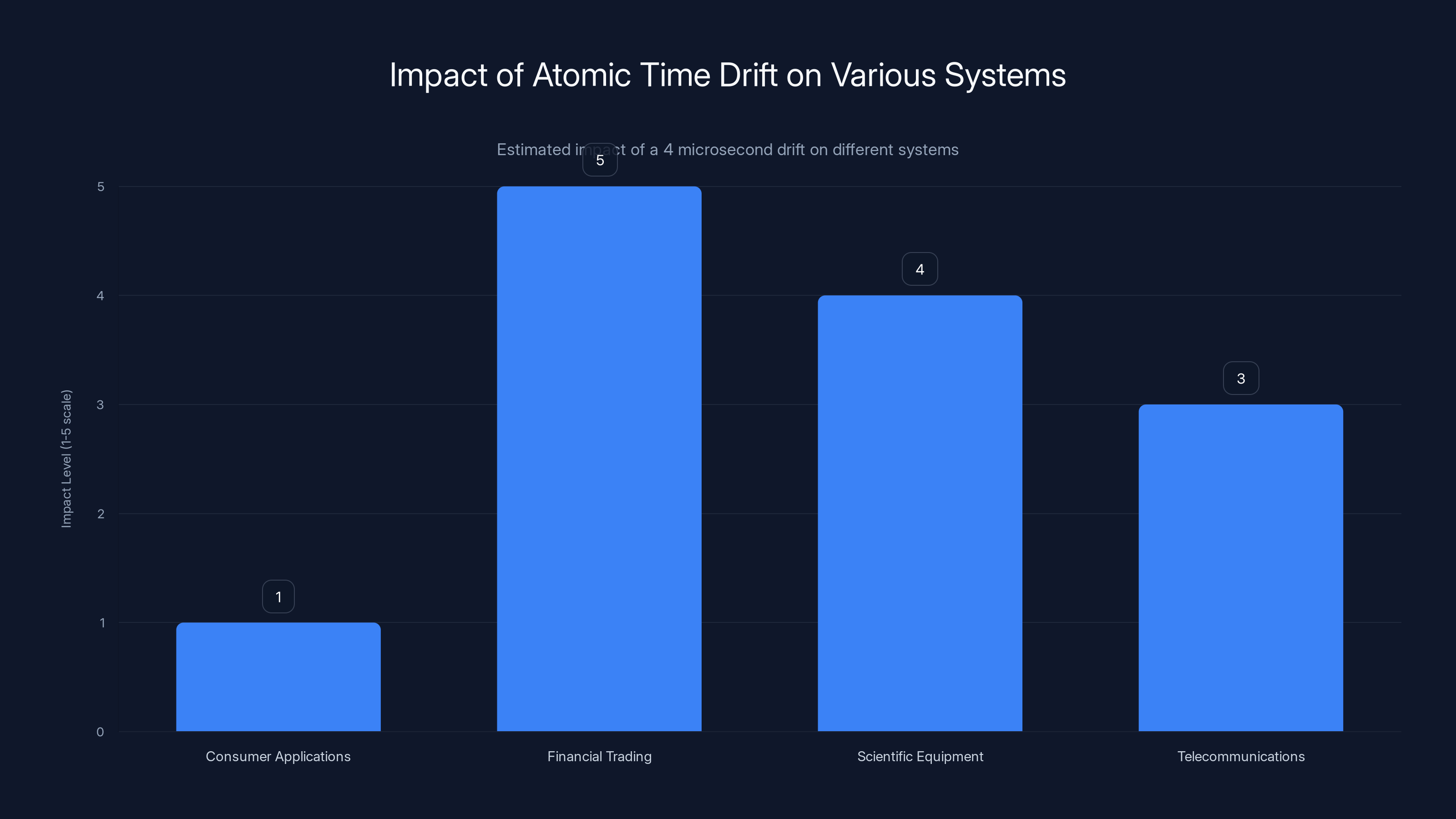

While a 4 microsecond drift is negligible for consumer applications, it poses significant challenges for high-frequency financial trading and scientific equipment requiring precise timing. Estimated data.

Key Takeaways

- NIST's atomic time reference drifted by four microseconds during a power outage at the Boulder, Colorado facility, but affected servers silently continued serving inaccurate time without alerts

- Round-robin DNS and geographic distribution protected most users, but systems with hard-coded server addresses were exposed to incorrect timestamps without warning

- Financial trading systems, power grids, and scientific research equipment require nanosecond-to-microsecond precision, making even small time deviations catastrophic for these applications

- This was the second major NIST time service disruption in a single month (Gaithersburg incident was even worse at millisecond-level drift), suggesting systematic infrastructure vulnerabilities

- Organizations can protect themselves by using multiple independent time sources, implementing drift monitoring, testing backup systems regularly, and maintaining geographic redundancy in time references

![NIST Atomic Time Server Outage: How America's Internet Lost Precision [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nist-atomic-time-server-outage-how-america-s-internet-lost-p/image-1-1766608534158.jpg)