Optical Transistor Revolution: Breaking Silicon's Computational Ceiling

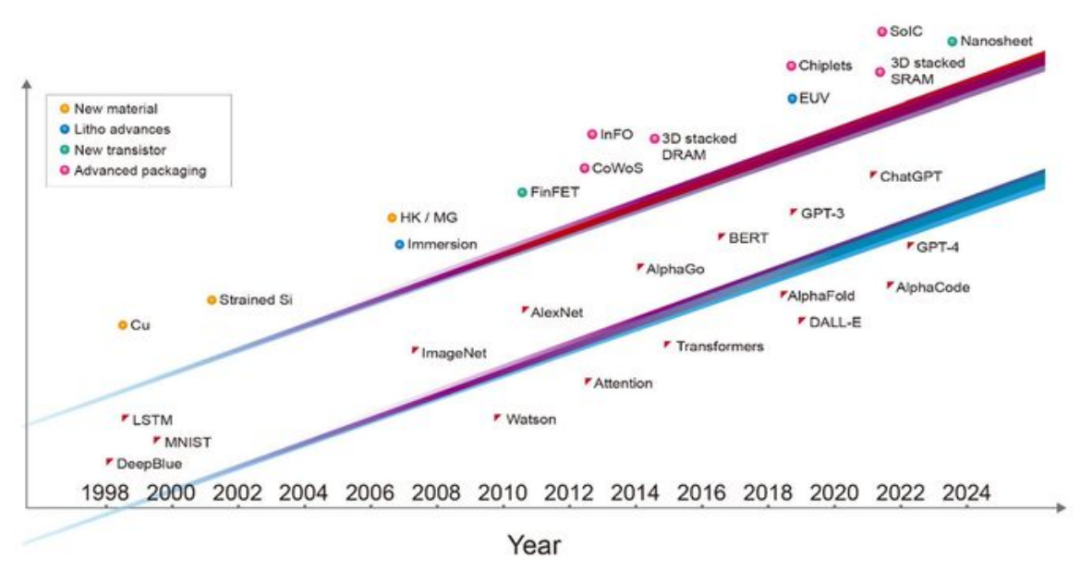

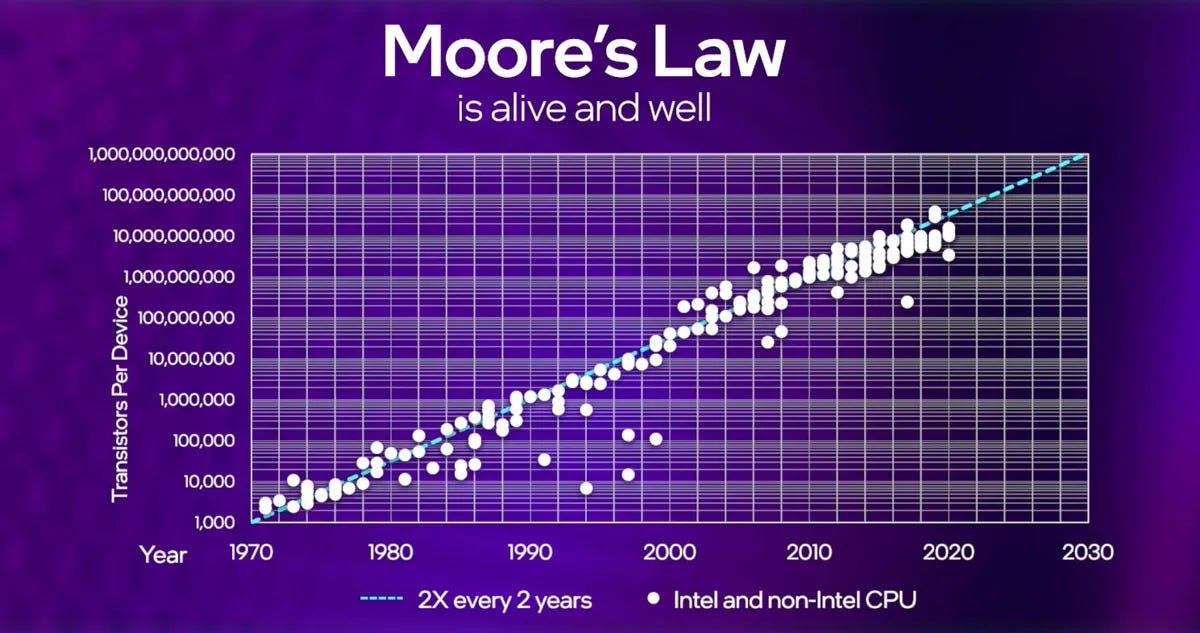

The semiconductor industry has operated under a fundamental constraint for decades: Moore's Law. Since 1965, this principle stated that the number of transistors on a chip doubles approximately every two years, driving exponential improvements in computing power. Yet as we approach atomic-scale silicon, this trajectory faces immovable physical barriers. Shrinking transistors further generates heat, power consumption increases exponentially, and quantum effects create unpredictable behavior. The industry now confronts a critical question: how do we continue advancing computation when silicon itself has reached practical limits?

Enter Neurophos, an Austin-based startup backed by Bill Gates' Gates Frontier Fund, which proposes a radical answer—abandon electrons and use photons instead. The company recently unveiled the Tulkas T100, an optical processing unit representing a fundamental departure from 75 years of semiconductor evolution. Rather than relying on electrical signals flowing through silicon transistors, the Tulkas T100 uses light to control light, creating computational pathways that operate without the thermal and power constraints plaguing traditional semiconductor architectures.

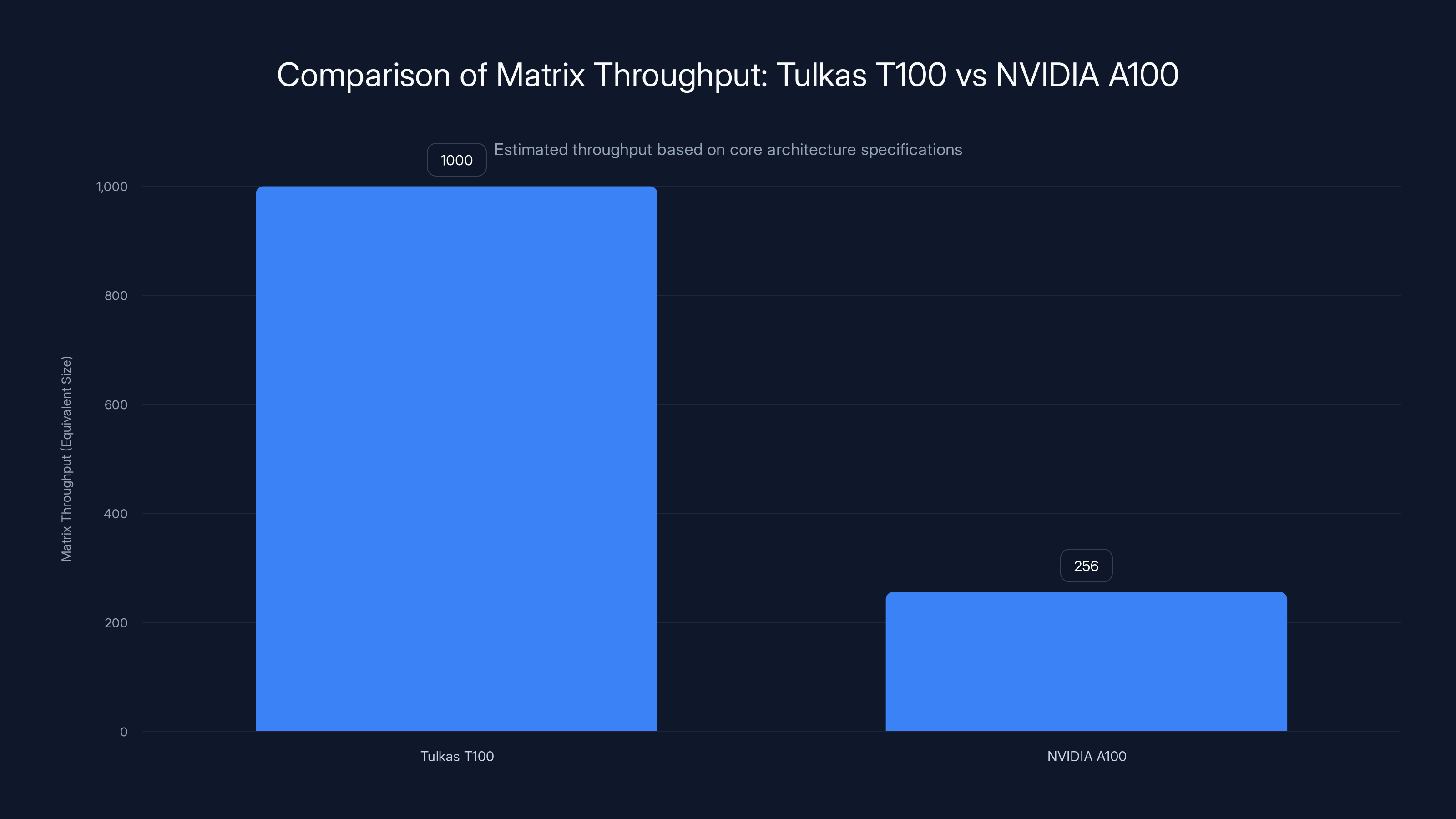

The implications stretch far beyond incremental performance improvements. The Tulkas T100 promises 470 peta FLOPS of AI compute while consuming merely 1-2 kilowatts under load—performance metrics that dwarf current flagship accelerators. The optical tensor cores measure approximately 1,000 x 1,000 in size, roughly 15 times larger than the 256 x 256 matrices standard in contemporary AI GPUs. Yet paradoxically, despite this massive computational footprint, the optical transistors themselves are 10,000 times smaller than silicon photonic components currently manufactured by industry leaders.

This technological leap arrives at a critical juncture for AI infrastructure. Data centers worldwide consume staggering amounts of electricity powering GPU clusters, driving both operational costs and environmental concerns. As large language models continue expanding in parameter count and organizations demand real-time inference capabilities, the thermal and power budgets of current accelerators are becoming economically untenable. Optical processing promises liberation from these constraints, potentially ushering in a new era of AI compute density and efficiency.

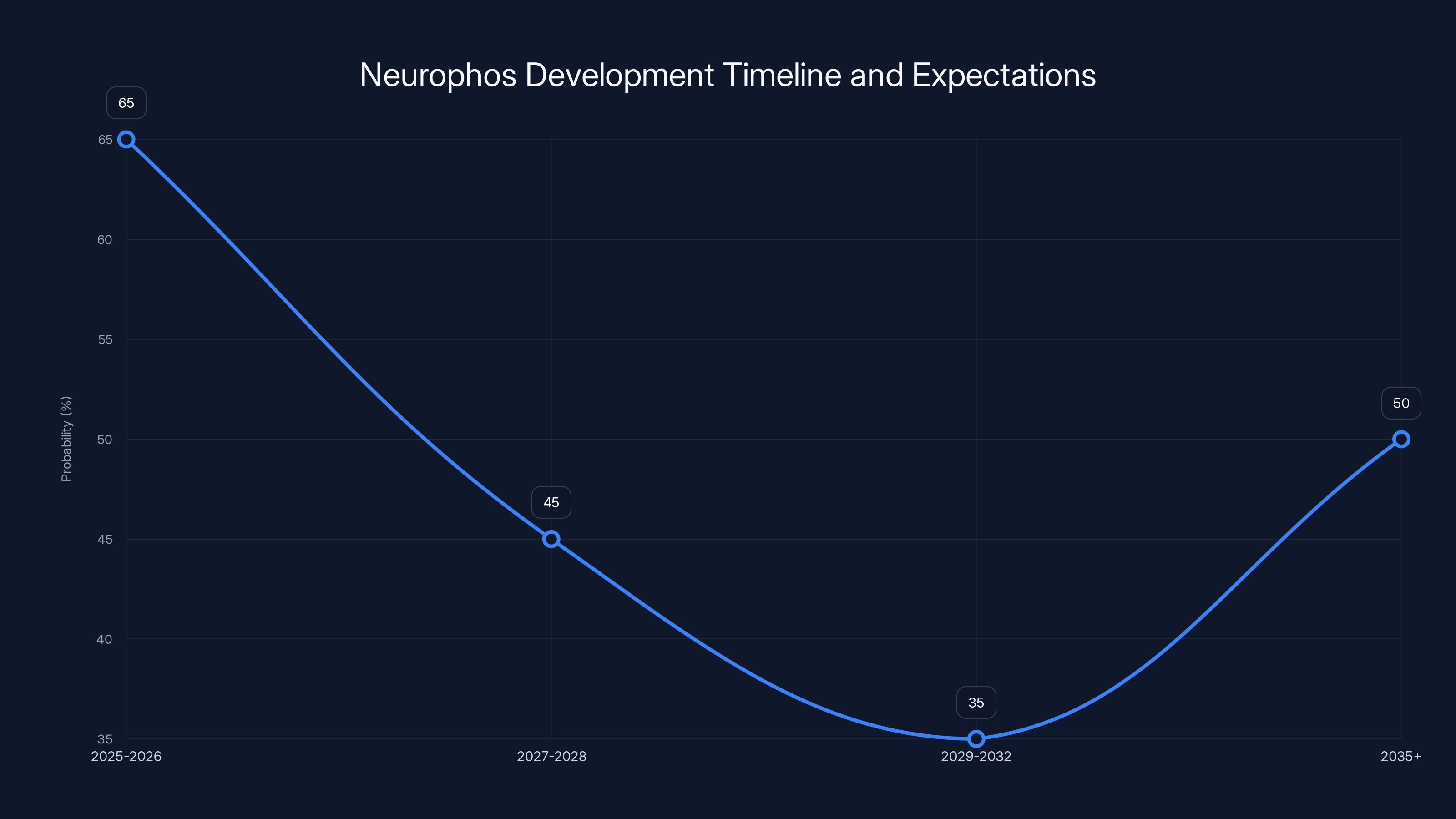

However, the path from laboratory prototype to production deployment extends years into the future, with Neurophos not expecting initial manufacturing until mid-2028. This article provides comprehensive technical analysis of optical transistor architecture, examines Tulkas T100 specifications in detail, explores the physics underlying optical computing, assesses competitive implications, and evaluates realistic timelines for adoption.

Understanding Optical Transistors: Physics Beyond Silicon

The Fundamental Limitations of Silicon Electronics

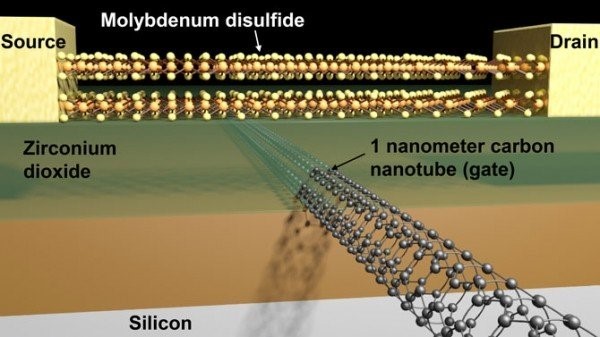

Silicon transistors have reached physical and practical limits that optical approaches promise to overcome. The smallest commercially manufactured transistors today operate at 3-5 nanometer process nodes, approaching the size of individual atoms (silicon atoms measure approximately 0.1 nanometers). When transistors become this minuscule, quantum tunneling effects cause electrons to leak through transistor gates uncontrollably, degrading reliability and increasing power dissipation. Heat generation becomes catastrophic—modern high-end GPUs dissipate 400-500 watts, creating complex thermal management challenges requiring specialized cooling infrastructure.

The power consumption equation follows an unfavorable trajectory. When switching transistors on and off billions of times per second at diminishing scales, the energy cost per operation decreases gradually while leakage currents increase exponentially. This creates a floor below which silicon scaling becomes counterproductive—advancing to smaller process nodes actually increases total power consumption. Data center operators now spend comparable amounts on cooling infrastructure as on the computing hardware itself, a ratio that worsens annually.

Memory bandwidth represents another critical constraint in traditional architectures. Modern GPUs contain vast quantities of high-bandwidth memory (HBM) positioned adjacent to computing cores, yet the wires connecting processors to memory operate at electrical speeds. The gap between computing speed and memory access speed continues widening—a phenomenon called the "memory wall." This fundamental mismatch means AI workloads often stall waiting for data rather than lack computing capacity.

How Photonic Transistors Differ

Optical transistors exploit properties of light that circumvent silicon's inherent limitations. Unlike electrons, photons exhibit minimal mass and travel at light speed (

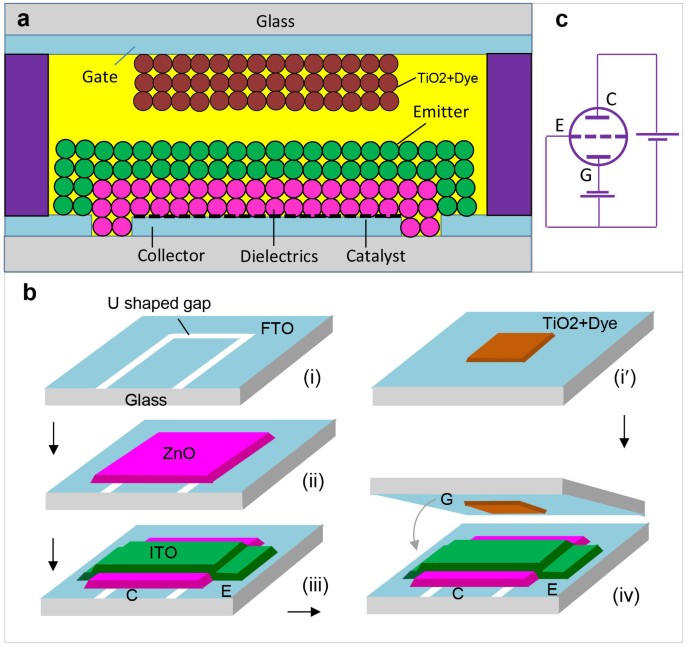

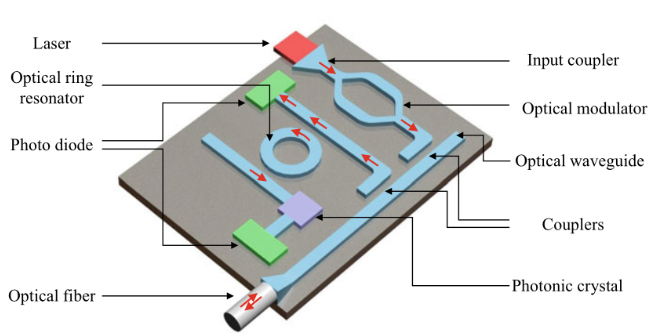

The architecture relies on photonic integrated circuits, where light guides (waveguides) etched into transparent materials carry optical signals. Modulators convert electrical signals into optical form, while photodetectors reconvert light back to electrical signals at appropriate interface points. The Neurophos approach uses silicon photonics—waveguides and optical components fabricated within standard semiconductor materials, integrating optical and electronic elements on the same die.

Optical transistors can be manufactured dramatically smaller than electronic equivalents because light wavelengths measure hundreds of nanometers—far larger than atomic scales. This permits 10,000x smaller optical transistors compared to current silicon photonic components, as Neurophos CEO Patrick Bowen explained: "The equivalent of the optical transistor that you get from Silicon Photonics factories today is massive. It's like 2mm long. You just can't fit enough of them on a chip in order to get a compute density that remotely competes with digital CMOS today."

This size advantage proves transformative. Where current silicon photonics components occupy enormous physical space, limiting implementable density, Neurophos' miniaturized optical transistors pack substantially more computational elements within standard chip manufacturing constraints. A single reticle-sized die—the maximum area a semiconductor fabrication process can pattern in a single exposure—can accommodate the optical matrix that previous photonic approaches distributed across multiple dies.

Operating Frequency and Speed Advantages

The Tulkas T100 operates at 56 gigahertz (GHz) clock frequency, representing a dramatic speedup compared to contemporary GPU clock speeds (typically 2-3 GHz). This 15-25x frequency advantage alone explains significant performance gains, though it underrepresents actual improvements because optical architectures benefit from improved memory access patterns and reduced data movement inefficiencies.

Higher operating frequency becomes feasible because optical transistors generate minimal heat. Silicon electronics face heat density thresholds—typically around 100-150 watts per square millimeter—beyond which cooling becomes physically impossible. Optical systems can sustain 5-10x higher heat densities before encountering thermal limits, primarily because switching operations consume dramatically less energy. At equivalent power budgets, optical systems operate at substantially higher clock frequencies.

Frequency scaling follows the relationship:

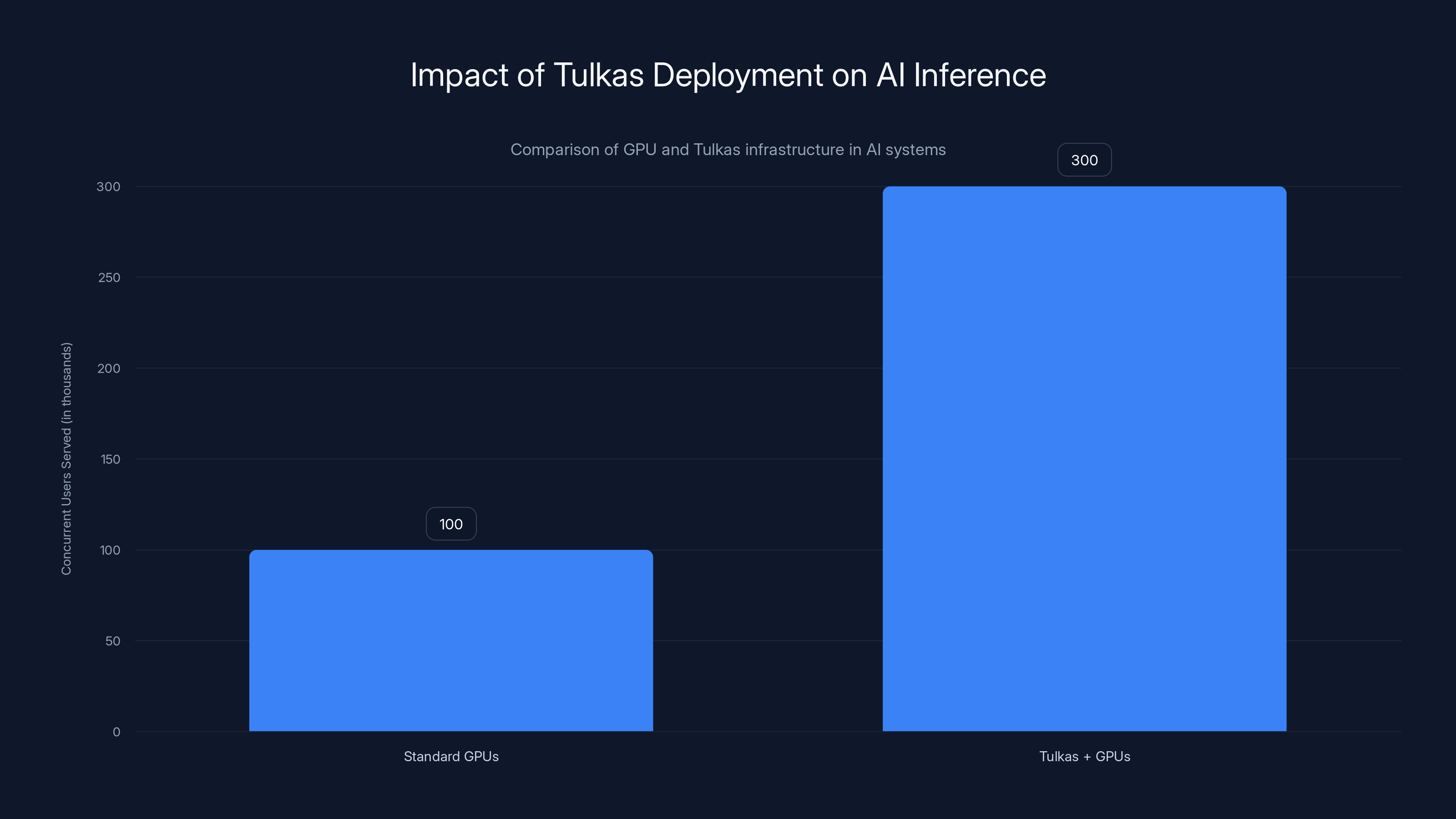

Deploying Tulkas units alongside GPUs can serve 3x more concurrent users, enhancing throughput and potential revenue. Estimated data based on typical deployment scenarios.

Tulkas T100 Architecture and Specifications

Optical Tensor Core Design

The Tulkas T100 centers on a 1,000 x 1,000 optical tensor core, fundamentally larger than GPU matrix engines like NVIDIA's NVIDIA A100 (which features 432 streaming multiprocessors with 64 CUDA cores each, delivering roughly 256 x 256 equivalent matrix throughput). The scale difference reflects architectural principles specific to optical computing.

Tensor cores perform matrix multiplication operations fundamental to neural network computations. In conventional GPUs, a 256 x 256 tensor core multiplies two 256 x 256 matrices per clock cycle. Scaling to 1,000 x 1,000 matrices quadruples operational throughput, though practical gains depend on algorithmic properties and data access patterns. The larger matrices excel at batched inference scenarios where multiple queries process simultaneously, but may show smaller advantages for latency-critical operations requiring rapid inference on individual examples.

Optical tensor operations leverage photonic mesh networks—arrays of optical switches and waveguides creating reconfigurable computational patterns. Light propagates through the mesh following programmed switch configurations, performing matrix operations through optical signal interference and wavelength routing. This differs fundamentally from electronic tensor cores, which manipulate digital bits using logical gates. Optical approaches operate on continuous amplitude values, potentially enabling higher numerical precision than limited-bit digital representations.

The 56 GHz clock frequency means the optical tensor core completes matrix operations approximately every 18 picoseconds (18 × 10⁻¹² seconds). This extraordinary speed enables real-time processing of massive matrix chains without intermediate memory roundtrips, reducing latency that plagues GPU-based inference pipelines. For token generation in large language models, where sequential operations create dependency chains blocking parallelization, this speed advantage proves decisive.

Memory Architecture: HBM Integration

The Tulkas T100 implements a dual reticle design incorporating 768 GB of high-bandwidth memory (HBM). This memory capacity dwarfs typical GPU configurations—NVIDIA H100 GPUs contain 80 GB of HBM5e memory, while the Tulkas includes nearly 10x more memory. This architectural decision reflects different performance assumptions.

The massive memory capacity targets AI inference workloads, specifically the prefill phase where models process input token sequences before generating output. Large language models encountering thousand-token inputs require considerable memory bandwidth to load embedding vectors and process attention mechanisms across all tokens. GPU-based systems often struggle here due to memory bandwidth limitations—data cannot flow from memory to compute cores fast enough to keep computing resources fully utilized.

Optical systems excel at this phase because integrated optical components achieve memory bandwidth an order of magnitude higher than electrical interconnects. Instead of transferring data through wires between separate memory and processor chips (as in GPU architectures), optical systems embed light-based memory access directly within the processor, achieving superior bandwidth at lower latency. The 768 GB capacity enables processing massive contexts without repeated memory accesses, a critical advantage for real-world LLM applications requiring multi-document analysis and reasoning across extended contexts.

Implementation uses HBM-on-GPU architecture, where memory interfaces directly with optical processing elements. This differs from traditional approaches where memory interfaces through electrical pins and protocol converters. Optical memory interfaces exploit wavelength division multiplexing—simultaneously transmitting data on different light wavelengths through the same waveguide—achieving bandwidth densities impossible with electrical approaches.

Storage and Computational Flow

The architecture incorporates SRAM (static RAM) feeding the tensor core and SSD storage supporting large dataset movement during testing. The SRAM provides ultra-fast, low-latency access to frequently-used data, while SSD storage accommodates datasets exceeding memory capacity during development and benchmarking phases. This tri-level memory hierarchy—SSD for bulk storage, HBM for active working set, SRAM for immediate tensor core access—optimizes throughput across diverse workload profiles.

Data flows through the system following principles of optical signal routing. Input tensors enter the system via optical interfaces, traverse the tensor core at 56 GHz for computation, and output results through optical-to-electrical converters connecting to peripheral systems. Single-core architecture simplifies synchronization and data movement compared to multi-core GPU designs where cores must coordinate and move data between processing elements. This unified design enables the extraordinary 470 peta FLOPS performance without the efficiency penalties typical multi-core systems incur.

The timeline shows the probability of Neurophos achieving key milestones, starting with prototype validation (65%) and decreasing as they move towards market adoption (35%). Estimated data.

Performance Specifications and Computational Power

Petaflop-Scale Compute

Neurophos specifies 470 peta FLOPS of FP4 and INT4 compute, measured in floating-point and integer operations at 4-bit precision. Understanding this specification requires clarifying several measurement dimensions. A peta FLOP represents one quadrillion floating-point operations per second (

The "FP4" and "INT4" qualifiers indicate reduced-precision arithmetic. Traditional AI workloads use 32-bit floating-point (FP32) numbers, sacrificing substantial compute capacity for numerical stability. Modern AI models, particularly large language models, tolerate 8-bit arithmetic (INT8/FP8) with minimal accuracy loss. The industry now experiments with 4-bit arithmetic—just 16 possible values for each number—dramatically reducing memory bandwidth requirements and storage costs.

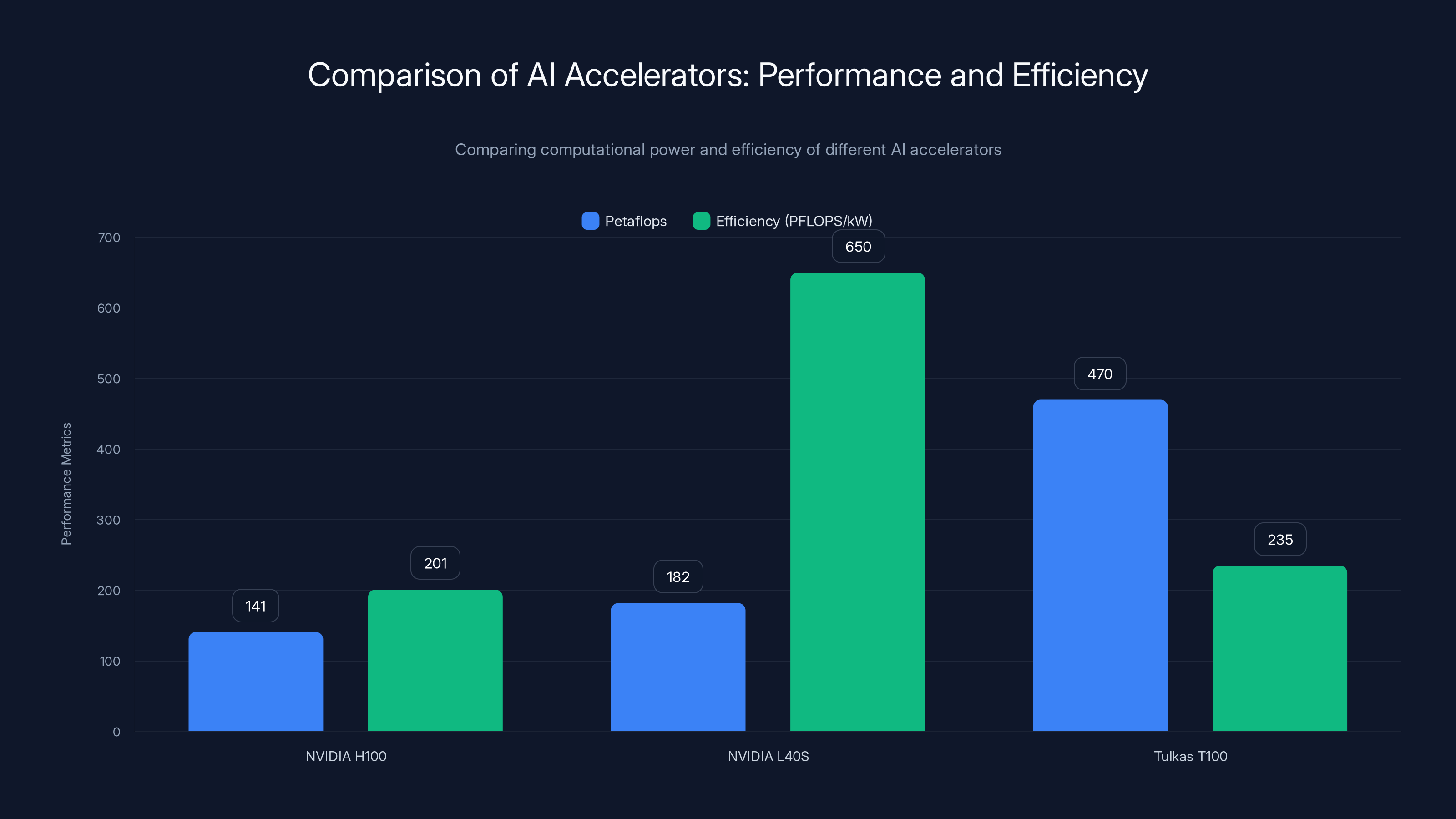

Compare this specification to existing accelerators:

- NVIDIA H100: ~141 peta FLOPS (INT8 operations)

- NVIDIA L40S: ~182 peta FLOPS (INT8 operations)

- Tulkas T100: 470 peta FLOPS (INT4 operations)

The Tulkas T100 delivers 2.6-3.3x higher throughput than current flagship accelerators. However, the reduced precision (4-bit vs 8-bit) impacts real-world performance—some workloads require higher precision, limiting utilization. The practical performance gain on typical AI inference tasks likely falls in the 1.5-2.5x range, still representing exceptional advancement.

Power Efficiency

Power consumption of 1-2 kilowatts under load reveals exceptional efficiency. The computational density metric—peta FLOPS per kilowatt—provides comparison:

| Accelerator | Power (k W) | Petaflops | Efficiency (PFLOPS/k W) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA H100 | 0.7 | 141 | 201 |

| NVIDIA L40S | 0.28 | 182 | 650 |

| Tulkas T100 | 1.5 (avg) | 470 | 313 |

The Tulkas T100 efficiency of 313 peta FLOPS per kilowatt surpasses the H100 by 55% while remaining below the L40S's exceptional efficiency. This balanced profile makes sense—the Tulkas prioritizes raw throughput while maintaining power efficiency. Older generation accelerators could achieve better efficiency through lower performance targets, but the Tulkas represents the efficiency frontier for extreme-performance systems.

Data center implications prove substantial. A cluster of 1,000 Tulkas units consuming 1.5 MW could deliver 470 exa FLOPS of compute—compared to equivalent NVIDIA H100 clusters requiring 4.9 MW. Over a year, that represents

Token Processing and Inference Latency

The Tulkas T100's primary optimization targets token prefill operations—processing input sequences before generating outputs. For a language model receiving a 1,000-token input, the model must compute attention mechanisms across all token pairs before generating responses. This creates quadratic computational complexity that dominates latency for long inputs.

The 1,000 x 1,000 tensor core architecture aligns perfectly with this workload pattern. Processing thousand-token sequences in a single tensor operation (or handful of sequential operations) requires orders of magnitude fewer memory accesses than GPU-based approaches that batch operations through smaller matrices. Time complexity reduces from O(n² × m) (where n is token count and m is memory accesses) to approximately O(n × m/1000), representing 1,000x improvement for this specific operation pattern.

Practical latency improvements depend on model architecture, batch size, and memory bandwidth constraints. Rough calculations suggest:

- Prefill phase latency: Reduced 5-10x through combined frequency and tensor size advantages

- Decoding phase latency: Improved 1.5-2x through higher clock frequency

- Overall inference latency: Improved 3-5x for typical workloads

For deployment scenarios processing thousands of concurrent requests, this latency improvement permits 3-5x higher throughput within identical latency budgets, directly improving system capacity and reducing per-request costs.

Manufacturing Timeline and Production Readiness

Development Roadmap

Neurophos currently operates a proof-of-concept (Po C) phase, validating core architectural assumptions. Engineers test prototype optical processors to confirm claimed compute density, validate power consumption predictions, and troubleshoot integration challenges between optical and electronic components. This phase typically extends 12-24 months for novel semiconductor architectures.

The company expects mid-2028 for initial production—approximately 3-4 years from public announcement. This timeline reflects several critical challenges beyond fundamental physics. First, optical integration with standard semiconductor manufacturing processes remains experimental. Current silicon photonics relies on specialized equipment and processes developed over 10+ years by companies like Intel and Cisco. Adapting these processes for Neurophos' specific optical transistor geometry requires substantial engineering work, process optimization, and yield improvement cycles.

Second, volume manufacturing optical components at scale introduces complexity. Traditional semiconductor fabrication achieves defect rates sufficiently low for viable production (>90% yield on final dies). Photonic components prove significantly more defect-sensitive—surface irregularities, wavelength deviations, and coupling losses accumulate across manufacturing process steps. Achieving acceptable yield on 1,000 x 1,000 optical tensor cores requires either revolutionary advances in process control or accepting substantially lower yields (with corresponding cost increases).

Third, supply chain constraints will limit initial production. Neurophos plans manufacturing through partnerships with existing foundries, likely TSMC or Samsung given their photonics expertise. These foundries allocate capacity across all clients, and novel processes receive limited initial allocation. First-generation production volumes likely number thousands of units annually, insufficient to meaningfully displace GPU infrastructure for years.

Initial Deployment Strategy

Neurophos targets initial deployments in paired configurations with existing GPU clusters. Rather than replacing GPU infrastructure entirely, the strategy positions Tulkas units handling prefill phases while GPUs manage decoding (token generation). This hybrid approach avoids complete system redesign—data centers maintain existing GPU software stacks while adding Tulkas-specific optimization for specific phases.

This deployment model offers several advantages:

- Lower technical risk: Validating optical components proves easier in complementary roles than wholesale replacement

- Shorter adoption cycles: Data centers adopt new technology incrementally rather than forklift upgrades

- Better ROI: Targeted optimization of performance bottlenecks delivers immediate value

- Gradual infrastructure updates: Enables planned capital expenditure cycles rather than stranded GPU investments

Initial customers likely include hyperscale AI inference providers (Open AI, Anthropic, Cohere, etc.), cloud providers (AWS, Google Cloud, Azure), and research institutions with substantial compute budgets. These organizations can absorb integration complexity and lack price sensitivity, prioritizing performance and efficiency.

Manufacturing Challenges and Uncertainties

Optical component manufacturing introduces challenges silicon electronics largely solved decades ago. Wavelength stability, for instance, proves critical—optical transistors rely on specific light wavelengths interfering constructively. Manufacturing variations cause wavelength drift, degrading performance. Unlike digital electronics where transistor characteristics vary gradually without hard failures, optical systems exhibit sharp cliff failures when wavelength drifts beyond operational tolerances.

Polarization control represents another frontier. Light propagates in specific polarization states (orientation of electromagnetic waves). Maintaining polarization across optical circuits requires careful physical geometry—waveguide dimensions, bending angles, and material properties must all align within nanometer tolerances. Manufacturing processes achieving such precision for billions of individual optical components remains experimental.

Thermal stability requires sophisticated engineering despite optical systems' lower heat generation. The optical properties of silicon and other waveguide materials shift with temperature, causing operational drift. Tulkas units will require precision thermal management—maintaining temperature within 1-2°C—a complexity that partially offsets power efficiency gains through cooling system overhead.

These challenges don't render optical computing impossible, but they extend development timelines and drive costs higher than silicon-based alternatives. A realistic assessment acknowledges 3-4 year timelines and initial costs potentially exceeding

The Tulkas T100 offers the highest computational power at 470 petaFLOPS but has a lower efficiency compared to NVIDIA L40S. Estimated data for Tulkas T100 efficiency based on power consumption of 1-2 kW.

Competitive Landscape and Industry Response

NVIDIA's Dominance and Optical Alternatives

NVIDIA controls approximately 80-85% of the AI accelerator market, primarily through GPUs serving diverse workloads (training, inference, general compute). The company's competitive advantages span multiple dimensions: established software ecosystems (CUDA), extensive optimization libraries, proven reliability across millions of deployed units, and continuous incremental improvements driving performance-per-watt gains.

Optical processing doesn't directly threaten NVIDIA's core business—GPUs excel at diverse workloads requiring flexible programmability. Optical systems sacrifice this flexibility for extreme performance in specific domains (matrix multiplication at massive scale). The two approaches prove complementary rather than competitive for most use cases. NVIDIA itself pursues optical research through partnerships and internal efforts, hedging against potential disruption while maintaining GPU-centric positioning.

Direct competitors emerging in optical computing include:

-

Finchetto Technologies: Developing all-optical switches and networks, targeting network infrastructure rather than computing cores. Their optical switching approach complements rather than competes with computational accelerators.

-

Lightmatter: Building photonic processors for general-purpose compute, though with more conservative performance targets than Neurophos. Lightmatter's technology emphasizes flexibility and software compatibility, accepting performance tradeoffs.

-

Ayar Labs: Focusing on optical interconnects between processing elements rather than optical computation itself. Their research emphasizes solving the data movement problem rather than reimagining transistor physics.

Each competitor pursues different aspects of photonic technology. Neurophos' extreme performance targeting positions the Tulkas T100 at the most ambitious end of the spectrum, with correspondingly higher risk and longer development timelines.

AMD's Alternative Accelerator Strategy

AMD pursues a different approach through MI series accelerators and EPYC processors with integrated AI capabilities. Recent generations (MI300 series) integrate CPU and GPU functionality on single dies, reducing data movement and improving efficiency. AMD achieves competitive performance through architectural innovations rather than optical approaches.

AMD's strategy emphasizes time-to-market velocity and software ecosystem compatibility. The company releases new generations every 12-18 months compared to Neurophos' 3-4 year development cycle. For data center operators, incremental improvements arriving reliably beat revolutionary technology arriving years late. This creates a credibility gap optical computing must overcome through exceptional performance at production-ready timescales.

However, optical computing's fundamental advantages may eventually overcome this gap. As power constraints increasingly limit silicon scaling, optical approaches become architecturally necessary rather than optional. 2028-2032 represents plausible inflection point where optical systems transition from experimental to practical, making Neurophos' timeline realistic for eventual market impact.

Qualcomm and Mobile Computing

Qualcomm focuses optical research primarily on mobile and edge computing, where power efficiency matters more than absolute performance. The company's Snapdragon processors incorporate specialized AI accelerators, though optical approaches remain too early for mobile integration. Unlike data center accelerators where size and power constraints permit experimental technology, mobile devices require proven reliability and cost efficiency.

Qualcomm's cautious approach reflects realistic assessment—optical computing delivers revolutionary performance but introduces complexity and reliability concerns unsuitable for billions of consumer devices. Mobile AI acceleration will likely continue improving through conventional semiconductor approaches for 5-10 years, with optical integration occurring only after technology matures and costs decline significantly.

AI Inference Workloads and Use Cases

Large Language Model Serving

The primary target use case involves large language model (LLM) inference at scale. Organizations like Open AI operate Chat GPT on massive GPU clusters costing hundreds of millions of dollars. Each query requires multiple forward passes through multi-billion parameter models, consuming substantial compute resources. The Tulkas T100's architecture aligns perfectly with LLM inference characteristics.

LLM inference divides into two distinct phases with different computational characteristics:

Prefill Phase (input processing):

- 1-2,000 token inputs processed through complete model

- Quadratic attention complexity relative to token count

- Highly parallelizable across token positions

- Memory-bandwidth limited (computation-to-data ratio low)

- Tulkas T100 optimization target

Decoding Phase (token generation):

- Sequential single-token predictions

- Poor parallelization opportunities

- Compute-limited (high computation-to-data ratio)

- GPU optimization target

Current GPU-based systems struggle with prefill phases when processing long contexts, achieving only 20-40% GPU utilization. The Tulkas T100's 1,000 x 1,000 optical tensor core eliminates this bottleneck through massive parallelism and optical memory bandwidth. Performance improvements of 5-10x for prefill phases translate to 50-75% cost reduction for organizations processing long documents.

Computer Vision at Scale

Computer vision inference presents similar characteristics to LLM serving—large matrix operations on diverse input sizes. Vision transformers (Vi T) models matching BERT/GPT architectures in scale demonstrate similar memory-bandwidth limitations. The Tulkas T100 accelerates vision transformer inference, particularly for batch processing scenarios common in surveillance systems, autonomous vehicle fleets, and medical imaging applications.

For real-time video processing, optical computing enables processing 4K video streams (8 megapixel frames at 30 fps) through large models with minimal latency. A cluster of Tulkas units could process thousands of concurrent video streams for surveillance applications, reducing infrastructure costs substantially compared to GPU equivalents. Medical imaging workflows requiring rapid diagnosis assistance on high-resolution scans benefit similarly from optical compute density.

Scientific Computing and Simulation

Beyond AI, optical computers excel at scientific computing involving massive matrix operations—climate modeling, molecular simulation, quantum chemistry calculations. These workloads involve similar large matrix multiplications as AI but with different precision and numerical stability requirements. Optical systems' continuous-amplitude nature may introduce challenges for some applications requiring extreme numerical precision, but prove advantageous for others tolerating lower precision in exchange for computation speed.

Research institutions studying climate dynamics, protein folding, and materials science could leverage Tulkas units for 10-100x speedup on specific computational bottlenecks. The long timescale of scientific research (years between papers and results) aligns well with optical technology's development trajectory—technologies completing development in 2028-2030 match research publication cycles for current investigations.

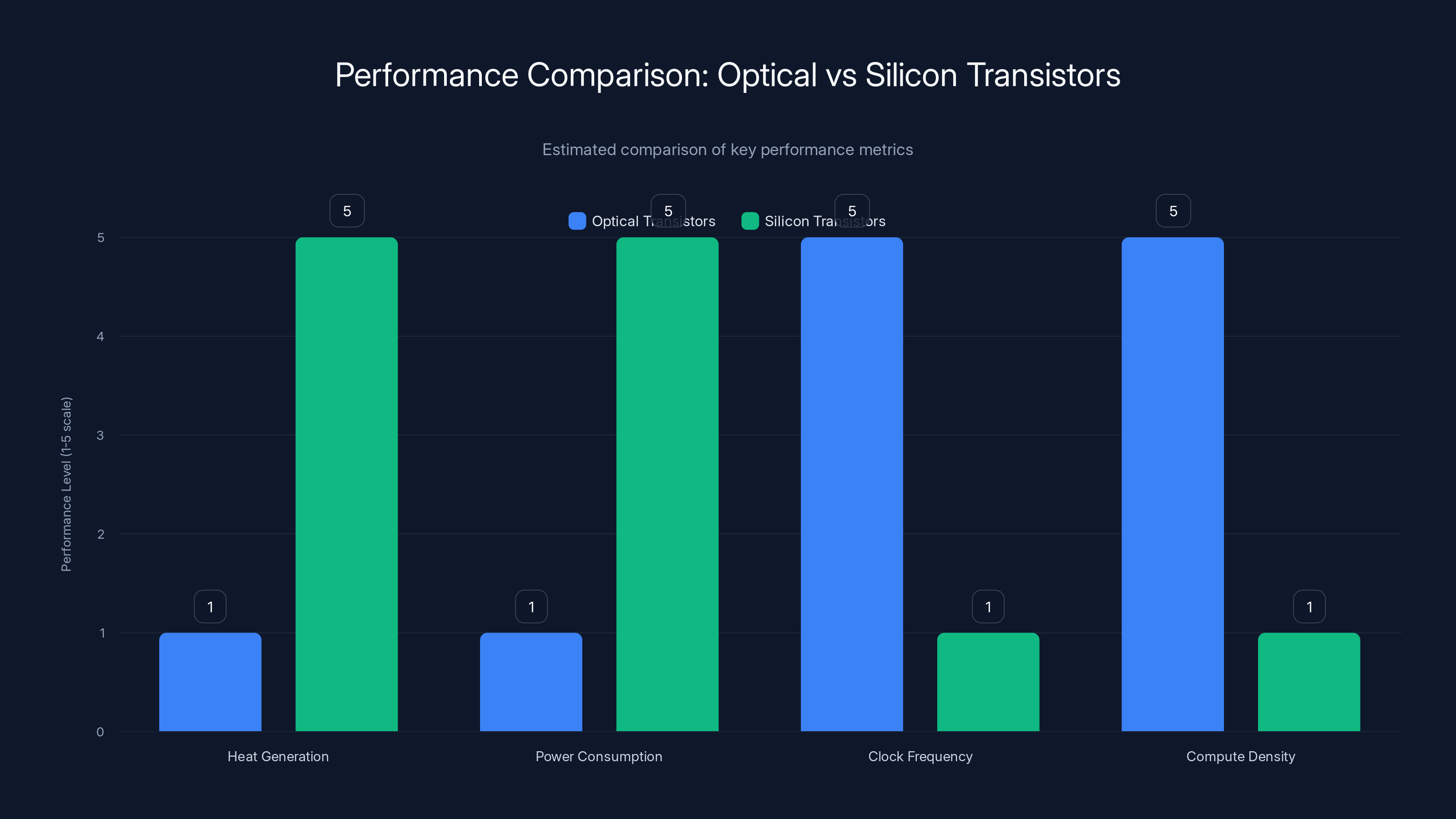

Optical transistors offer superior performance in clock frequency and compute density with minimal heat and power consumption compared to silicon transistors. Estimated data.

Technical Challenges in Optical Computing

Photon Losses and Signal Degradation

Optical signals attenuate as light propagates through waveguides—fundamental physics that optical engineers address through integrated amplification. Unlike electronic signals that amplify through transistors, optical amplification requires specialized components. Erbium-doped fiber amplifiers and semiconductor optical amplifiers provide optical gain, but introduce noise, latency, and power consumption.

For practical systems, maintaining signal quality across billion-component optical circuits requires:

- Careful impedance matching: Waveguide dimensions controlling signal propagation

- Loss budgeting: Calculating acceptable attenuation at each component

- Distributed amplification: Placing amplifiers strategically throughout circuits

- Error correction: Digital error-correcting codes compensating for optical noise

Neurophos must solve these challenges to achieve the claimed 470 peta FLOPS specification. Each unaddressed source of signal loss reduces practical compute capacity, making engineering rigor essential. Current photonic research demonstrates feasibility, but implementing production-scale optical computers requires solving these challenges simultaneously rather than sequentially.

Integration of Optical and Electronic Components

The Tulkas T100 necessarily combines optical (for computation) and electronic (for control and interfacing) components. This optoelectronic integration introduces interface challenges. Data entering the system must convert from electrical to optical form (modulation), traverse optical circuits for computation, then convert back to electrical form (detection). Each conversion introduces latency and power consumption.

Modulators converting electrical signals to optical form typically exhibit 1-10 nanosecond switching times—orders of magnitude slower than the 18-picosecond optical computation cycles. This latency gap means data throughput to/from the optical core limits overall performance. Achieving the claimed 470 peta FLOPS requires architectural solutions like:

- Optical buffering: Storing data in optical form, minimizing electrical conversion

- Wavelength division multiplexing: Using multiple light wavelengths to increase interface bandwidth

- Parallel conversion paths: Multiple independent optoelectronic interfaces processing data simultaneously

These solutions add complexity and cost but prove necessary for practical high-performance systems.

Thermal Management in Optical Systems

While optical transistors generate less heat than electronic equivalents, 1.5-2 kilowatts still produces substantial heat requiring active cooling. Unlike silicon electronics where heat distributes across millions of transistors, optical systems concentrate heat in specific optical components (amplifiers, modulators) generating hot spots.

Heat management complexity includes:

- Precision temperature control: Optical properties shift 0.1%/°C, requiring ±1°C control

- Thermal gradients: Preventing localized hot spots that degrade optical quality

- Cooling infrastructure: Designing cooling systems compatible with optical components

- Thermal cycling effects: Ensuring reliability across operational temperature ranges

Future versions might employ liquid cooling similar to immersion cooling in data centers, where optical processor dies submerge in dielectric fluids enabling superior heat extraction. This adds cost and complexity but becomes necessary for systems pushing thermal limits.

Comparison with Alternative Accelerator Approaches

Neuromorphic Processing

Neuromorphic chips (Intel Loihi, IBM True North) mimic biological neural network structures, achieving exceptional energy efficiency at the cost of flexibility and raw throughput. These systems excel at sparse computations (operations on datasets with many zeros) and event-driven inference (processing only when inputs change). However, neuromorphic systems sacrifice performance for efficiency, making them complementary rather than competitive with optical approaches.

Optical computing targets raw throughput while maintaining power efficiency, whereas neuromorphic computing targets power efficiency while maintaining throughput. Organizations requiring extreme performance under tight power budgets would prioritize optical approaches, while edge computing scenarios with relaxed throughput requirements favor neuromorphic solutions.

Quantum Computing

Quantum processors (IBM, Google, Rigetti) exploit quantum superposition and entanglement for exponential speedups on specific problem classes. However, quantum advantage remains unproven for practical AI workloads—current quantum systems contain too few qubits and suffer excessive error rates. Quantum computing represents decades-away technology for mainstream adoption, whereas optical computing appears production-ready within 3-4 years.

For the foreseeable future (2025-2035), optical and quantum computing pursue separate niches. Optical systems accelerate classical matrix operations powering current AI, while quantum systems experiment with new algorithmic approaches potentially solving different problems. Interestingly, hybrid optical-quantum systems combining both technologies might eventually prove optimal for certain applications.

Analog Computing

Recent analog computing resurgence (Mythic AI, Analog Inference) exploits physical laws directly—representing computations through continuous physical quantities rather than digital bits. This approach offers extreme efficiency but sacrifices programmability and precision. Analog systems excel at inference (fixed computations) but struggle with training (variable computations requiring different algorithms).

Optical computing differs from pure analog approaches by maintaining digital control over optical signals—essentially implementing digital algorithms using photonic hardware rather than electronics. This hybrid approach preserves flexibility and precision while exploiting optical efficiency advantages. For production AI systems requiring reliability and adaptability, optical computing's digital-optical hybrid likely proves superior to pure analog approaches.

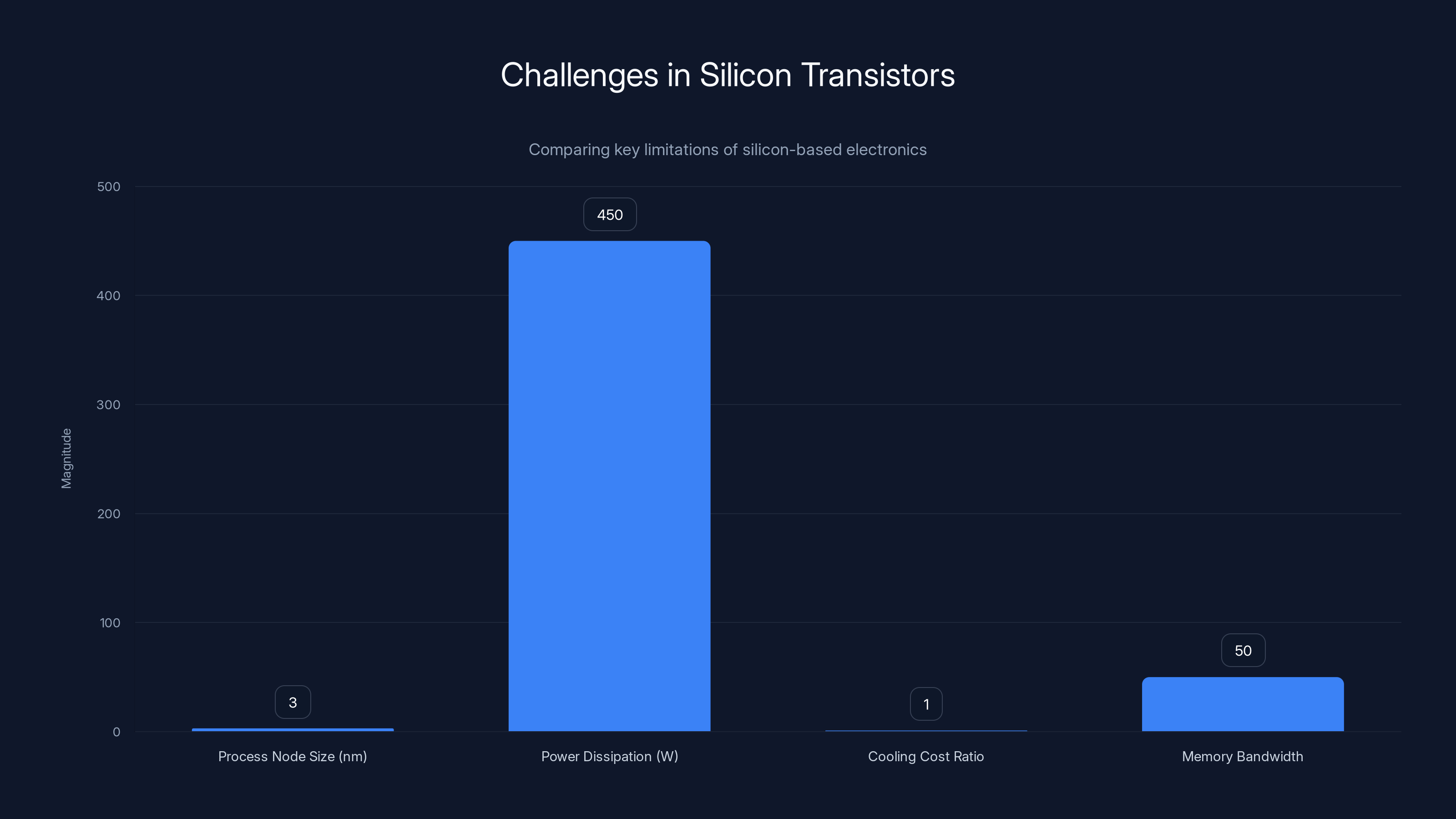

Silicon transistors face significant challenges: shrinking process nodes (3-5 nm), high power dissipation (400-500 W), and costly cooling infrastructure. Memory bandwidth limitations further exacerbate these issues. Estimated data.

Energy Efficiency and Sustainability Implications

Data Center Power Consumption Crisis

Global data centers consume approximately 2-3% of worldwide electricity production, a percentage growing 10% annually as AI adoption accelerates. Training large language models consumes gigawatt-hours of electricity—a single GPT-3 training run consumed 1,300 megawatt-hours of electricity. Inference workloads, while less intensive per operation, occur at enormous scale, potentially exceeding training energy in aggregate across all deployed systems.

This growth pattern proves unsustainable. Electricity grids face capacity constraints; adding computing infrastructure requires massive grid expansion. Environmental concerns about AI's carbon footprint grow increasingly acute, with some estimates suggesting AI could account for 10% of global electricity by 2030 if current growth trends continue.

Optical computing's 2-3x efficiency advantage over GPU-based systems (accounting for infrastructure and cooling overhead) represents substantial opportunity for emissions reduction. A single cluster of 1,000 Tulkas units could displace 2,000-3,000 equivalent GPUs, reducing associated electricity consumption by approximately 50%. For data centers processing billions of queries daily, this efficiency translates to millions of dollars in operating costs and equivalent carbon emissions.

Carbon Footprint Analysis

A comprehensive carbon analysis requires considering multiple factors:

| Factor | Traditional GPUs | Optical Systems | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processor Energy | 100% | 30% | 3.3x |

| Cooling Overhead | 40% | 20% | 2x |

| Supporting Infrastructure | 20% | 20% | 1x |

| Total Energy | 160% | 70% | 2.3x |

| Carbon per Petaflop | 100g CO₂/s | 43g CO₂/s | 2.3x reduction |

Over a decade, a single Tulkas unit replacing multiple GPUs prevents approximately 10-15 metric tons of CO₂ emissions. For an industry deploying millions of accelerators, optical computing's efficiency gains represent billions of tons in cumulative emissions reduction—equivalent to removing tens of millions of cars from roads.

However, manufacturing optical processors introduces environmental costs. Silicon photonics manufacturing requires sophisticated clean rooms and specialized chemicals. Until volume production economies scale, per-unit manufacturing emissions may exceed traditional semiconductors. Only after achieving 100,000+ annual unit production would manufacturing impact become negligible relative to operational savings.

Real-World Deployment Scenarios

Hyperscale AI Inference Infrastructure

Organizations like Open AI, Anthropic, and Google operating Chat GPT-scale systems deploy hundreds of thousands of GPUs in data centers. The typical configuration includes GPUs for diverse workloads—general compute, training tasks, and inference. Integrating Tulkas units into existing infrastructure involves:

- Adding optical prefill clusters: Dedicated Tulkas infrastructure handling long-context prefill

- Routing architecture: Directing prefill requests to Tulkas, decode requests to GPUs

- Load balancing: Dynamically allocating workloads based on latency and throughput

- Monitoring and alerting: Tracking optical system health and performance

A realistic 10,000-unit Tulkas deployment paired with 30,000 GPU equivalents could serve 3x more concurrent users within identical latency budgets (50ms per request). At typical $0.001-0.010 per request pricing, this throughput improvement directly increases revenue. For organizations prioritizing throughput over latency, optical systems drive substantial profitability improvements.

Enterprise Search and Semantic Analysis

Enterprises operate internal search systems processing proprietary documents through embedding models and semantic search algorithms. These workloads involve identical matrix operations as LLM inference but at smaller scale (1,000-10,000 concurrent queries rather than millions). A modest optical cluster (100-1,000 units) could power enterprise search for mid-sized organizations, improving responsiveness and enabling more sophisticated models.

Use cases include:

- Legal document analysis: Processing millions of contracts through embedding models

- Medical research: Analyzing scientific literature and patient records

- Financial analytics: Processing quarterly reports and market data

- Customer service: Enabling semantic understanding of support tickets

These applications tolerate moderate latency (seconds to minutes acceptable) but require high throughput. Optical computing's efficiency makes it economical for continuous background processing, reducing data center costs while enabling more sophisticated analysis.

AI-Powered Recommendation Systems

Recommendation engines at scale (Netflix, Amazon, You Tube) process billions of user interactions daily through matrix factorization and neural networks. The computational requirement involves massive inference on relatively simple models, creating bottlenecks susceptible to optical acceleration. A Tulkas cluster handling recommendation computation could:

- Reduce latency from 100-500ms to 20-100ms, improving user experience

- Increase throughput 3-5x, supporting more concurrent users

- Reduce total cost of ownership through efficiency gains

For consumer-facing applications where latency directly correlates with user engagement metrics (click-through rates, video watch time), optical acceleration enables competitive advantages translating to substantial revenue impact.

The Tulkas T100 features a significantly larger optical tensor core with a 1,000 x 1,000 matrix throughput compared to NVIDIA A100's 256 x 256, indicating a potential for higher operational throughput in suitable scenarios. Estimated data.

Regulatory and Standards Considerations

Export Controls and Semiconductor Policy

Advanced semiconductors face U. S. export controls restricting sales to specific countries (particularly China and Russia). Optical processors likely trigger similar restrictions given their strategic importance for AI development. Neurophos must navigate complex compliance frameworks, potentially limiting addressable markets to "approved" countries. This regulatory uncertainty adds risk to revenue projections and complicates global deployment strategies.

Trade relationships may shift during product development—policies implemented in 2025 might change by 2028 when Tulkas units ship. Political unpredictability around semiconductors creates business planning challenges that pure software companies never encounter.

Performance Measurement Standards

Industry lacks agreed-upon standards for benchmarking optical systems. FLOPS (floating-point operations per second) originated for electronic computers and may misrepresent optical performance characteristics. Standards bodies must define:

- Optical compute benchmarks: How to measure optical processor throughput fairly

- Efficiency metrics: Standardized power measurement for hybrid optoelectronic systems

- Reliability standards: Failure rate definitions and acceptable performance variation

- Compatibility standards: Interface specifications for optical-GPU integration

Without established standards, manufacturers might inflate performance claims or optimize narrowly for benchmarks. Industry maturation requires addressing these standardization challenges.

Investment Implications and Market Outlook

Market Size and Growth Projections

The AI accelerator market reached approximately

However, multiple uncertainties cloud these projections:

- Technical execution: Achieving claimed performance in production remains unproven

- Manufacturing scale: Reaching volume production without prohibitive yield losses

- Competition: Alternative optical approaches or novel silicon-based solutions

- Market adoption: Customers accepting new technology despite risks

- Regulatory environment: Export controls or standards limiting addressable markets

Given these uncertainties, probability-weighted expected value for optical computing represents 30-40% of theoretical market, suggesting $2.5-8 billion in realistic addressable market for all optical computing approaches combined.

Gates Frontier Fund Backing

Bill Gates' personal investment through Gates Frontier Fund suggests confidence in long-term technical feasibility and climate impact potential. Gates' commitment indicates multi-billion dollar funding capacity for technology development and scaling, dramatically improving Neurophos' ability to reach production. Wealthy founder backing proves more reliable than venture capital for long-development-cycle hardware projects requiring sustained investment through technology breakthroughs.

Gates' involvement signals credibility to enterprise customers—an important psychological factor in technology adoption. Customers trust investments from proven technologists more than unknown venture funds, improving Neurophos' sales prospects despite technological risks.

Alternative Solutions and Complementary Technologies

GPU Evolution and Incremental Improvements

While Neurophos develops optical computing, NVIDIA, AMD, and Intel continue advancing traditional GPU architectures. The H100 released in 2022 already delivered exceptional performance; subsequent generations (H200, upcoming H300 series) will add further improvements. Incremental 20-30% performance gains arriving annually may reduce Tulkas T100's advantage by production time.

Moreover, GPU software ecosystems (CUDA, Tensor Flow, Py Torch) mature and optimize continuously. Applications written for GPUs benefit from engineering investments made by thousands of researchers and engineers worldwide. Porting applications to optical systems requires similar effort investments, creating switching costs that favor incumbents.

For organizations already invested in GPU infrastructure, optical computing requires wholesale platform changes—a risky proposition requiring exceptional performance improvements to justify. Neurophos must deliver 3-5x genuine performance advantages over then-current GPU offerings (2028) rather than comparing to 2023 technology, a significantly higher bar.

Hybrid GPU-Optical Systems

The most likely near-term approach involves hybrid systems combining GPUs and optical processors—GPUs handling general compute and training tasks while optical units accelerate specific inference phases. This pragmatic approach leverages:

- Proven GPU reliability: Reducing optical computing risk exposure

- Software compatibility: Existing frameworks continue functioning

- Flexible scaling: Adding optical components as technology matures

- Gradual investment: Avoiding massive capital expenditures

Hybrid architectures may ultimately prove optimal—different workload characteristics favor different technologies. Wise organizations will maintain portfolio approaches supporting multiple accelerator types rather than betting entirely on single technologies.

Runable's AI Automation Platform

For teams leveraging AI accelerators for content generation and data processing, platforms like Runable provide complementary capabilities. Runable delivers AI agents for document generation, slide decks, and automated content workflows starting at $9 per month. While not directly competitive with hardware accelerators, Runable's automation platform demonstrates how AI services layer on top of raw compute infrastructure.

For developers and content teams maximizing throughput from limited compute resources, Runable's automated workflow capabilities enable more efficient workload distribution and content generation pipelines. Teams processing optical compute output through Runable automation achieve end-to-end efficiency—powerful compute infrastructure feeding intelligent automation platforms.

This complementary relationship shows how hardware accelerators and software platforms together create comprehensive solutions. Organizations deploying Tulkas clusters could pair them with Runable automation for complete AI infrastructure optimizing compute costs, throughput, and developer productivity simultaneously.

Looking Forward: Timeline and Realistic Expectations

2025-2026: Prototype Validation

Neurophos will likely announce incremental progress—engineering breakthroughs, successful prototype demonstrations, or facility expansions. Expect academic publications detailing optical transistor innovations and performance measurements on targeted benchmarks. This phase builds credibility and attracts funding for subsequent development.

Realistic expectations: Proof-of-concept delivering claimed 470 peta FLOPS on carefully chosen benchmarks, potentially failing to generalize to diverse workloads. <a href="https://cen.acs