Quadruple Axel Physics: How Ilia Malinin Defies Gravity [2025]

Watch Ilia Malinin launch himself into the air on the ice and you're seeing something that, just five years ago, most people thought was physically impossible. Four and a half rotations. In the span of roughly one second. While spinning around a single axis at mind-bending velocity.

The quadruple axel—often called the "Quad A" or "4A"—has become the holy grail of figure skating. It's the kind of move that gets replayed endlessly on social media, the kind that makes casual viewers go absolutely silent when it lands clean. And it's not just flashy athleticism. In modern competitive figure skating, landing a quad axel is the difference between winning and losing, between making history and fading into obscurity.

Here's what makes this so wild: until Ilia Malinin landed the first successful quad axel in competition in 2022, the move was purely theoretical. Biomechanics researchers had written papers about whether it was even possible. Coaches debated it. Skaters attempted it. And then Malinin, a teenager from Maryland with exceptional vertical leap and explosive power, just... did it. Now he's competing at the 2026 Winter Olympics as the clear favorite in men's figure skating, and the quad axel is no longer a "what if." It's a baseline expectation for elite male skaters.

But here's the thing: understanding how the quad axel actually works requires diving deep into physics, biomechanics, muscle physiology, and training methodology. It's not magic. It's science. And once you understand the science, the move becomes even more impressive because you realize just how finely tuned the human body has to be to pull it off. This guide breaks down everything you need to know about the quadruple axel, from the fundamental physics to the training protocols that make it possible.

TL; DR

- The quad axel requires 4.5 rotations in approximately 0.8 seconds, necessitating angular velocity of roughly 5.6 rotations per second

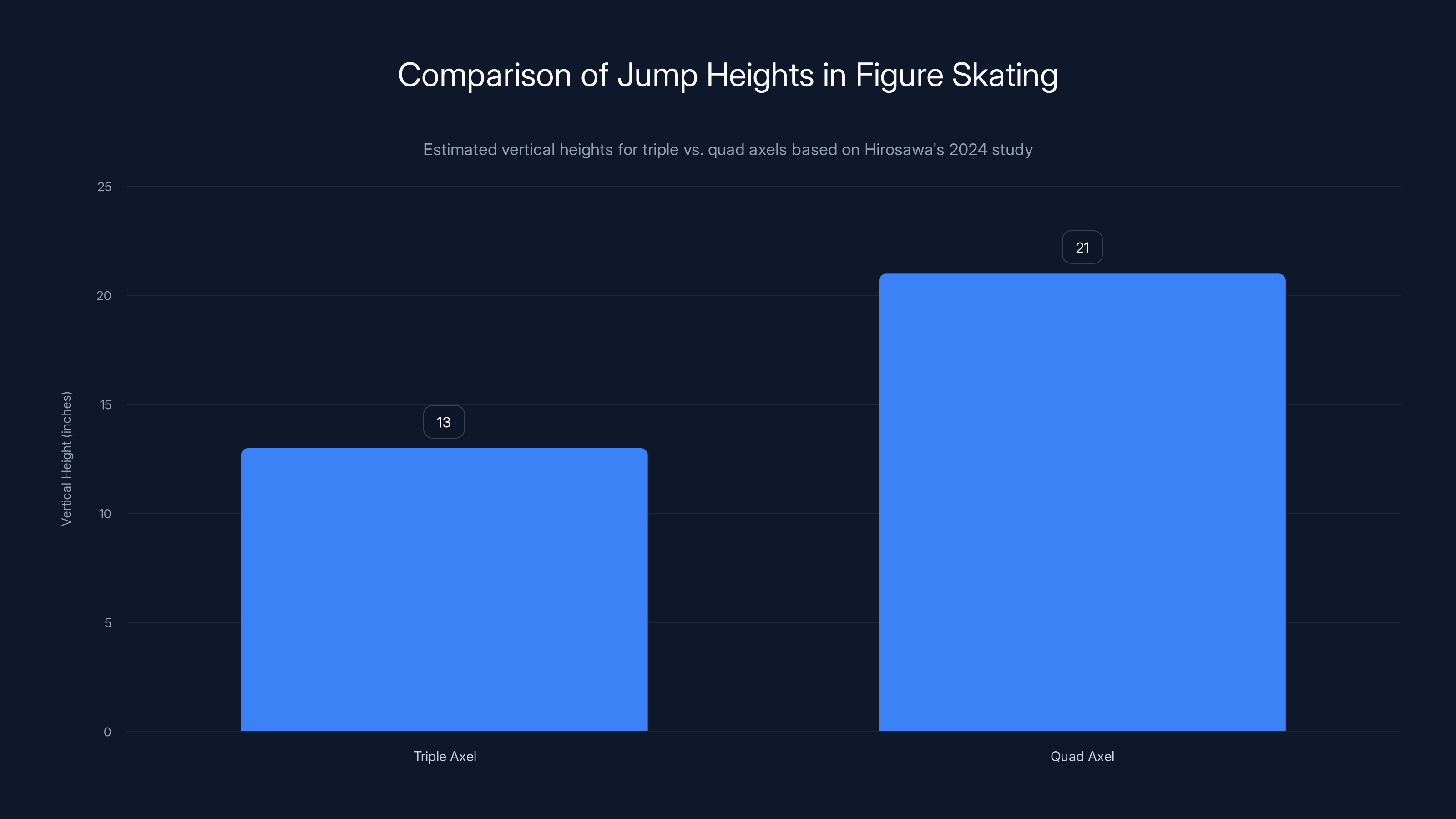

- Jump height is absolutely critical, with successful quad axels typically reaching 20+ inches, compared to 12-14 inches for triple axels

- Angular momentum is conserved during the jump, meaning pre-jump momentum directly determines how many rotations are possible

- Ilia Malinin's 2022 breakthrough changed everything, proving the move was possible and setting off an arms race among elite skaters

- Training for the quad axel requires years of preparation, specialized strength work, and a unique combination of power, flexibility, and proprioceptive awareness

The study revealed that skaters achieve significantly greater vertical heights during quad axels (around 21 inches) compared to triple axels (around 13 inches). Estimated data based on study insights.

The Fundamentals: What Makes an Axel Different From Every Other Jump

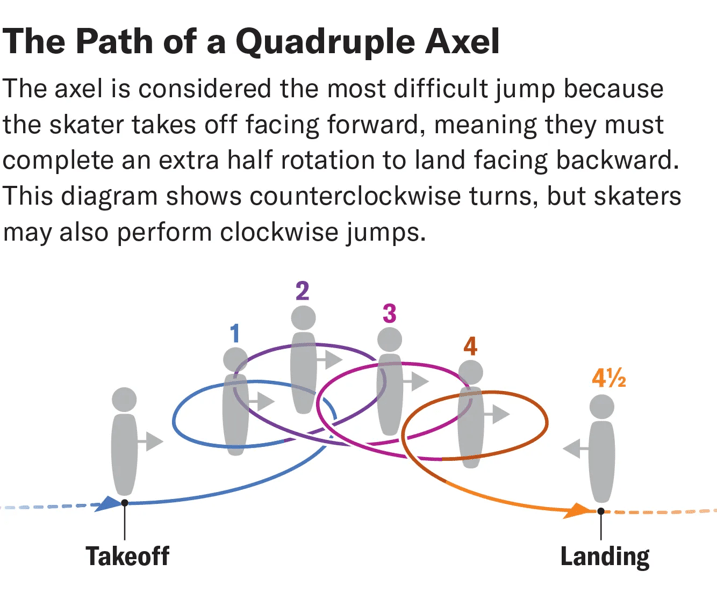

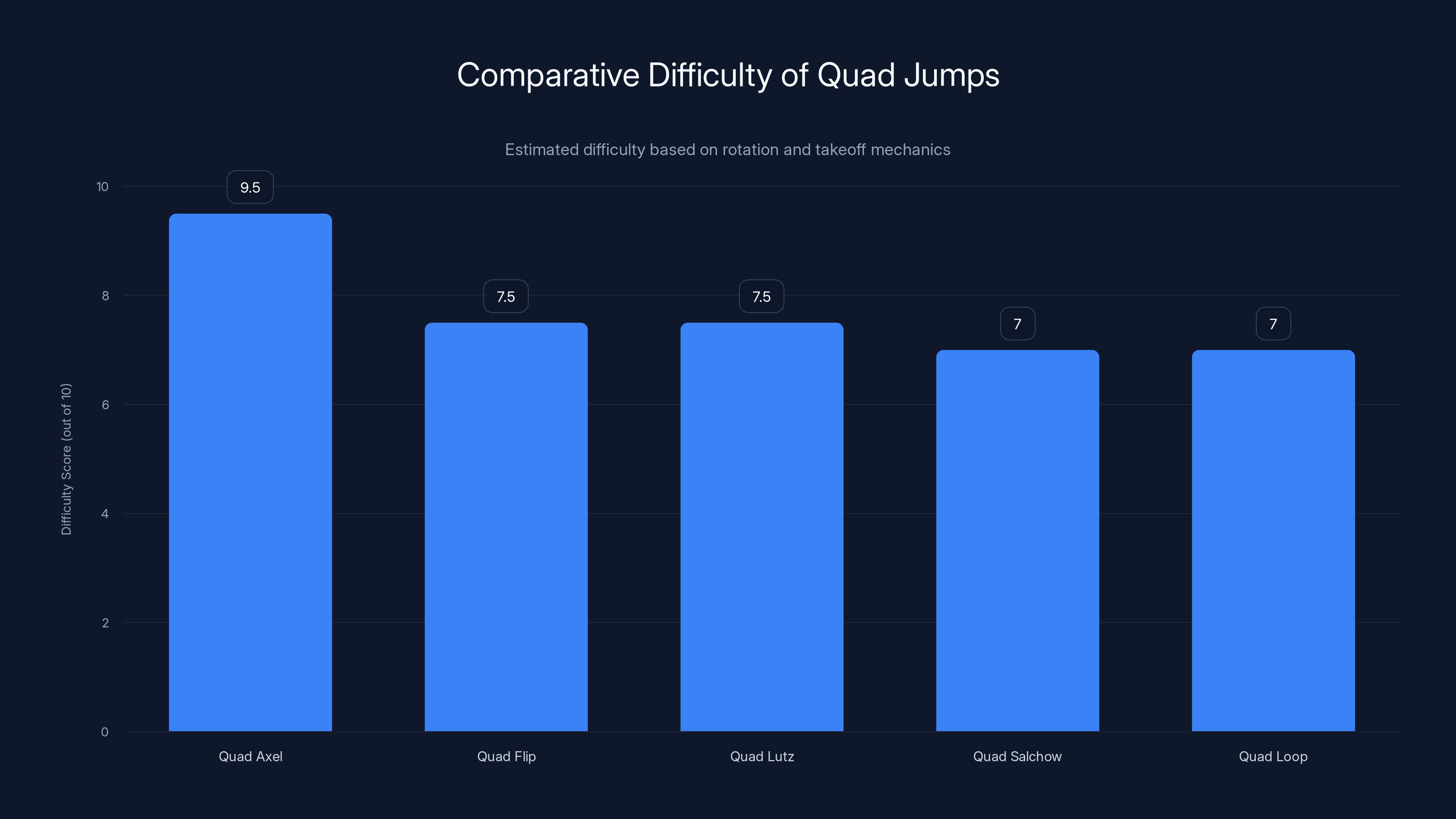

Before we can understand the quad axel, we need to understand what makes the axel fundamentally different from every other jump in figure skating. And this is crucial because the axel's mechanics directly inform why the quad version is so much harder than a quad flip or quad lutz.

There are six main jump categories in figure skating: the axel, lutz, flip, salchow, loop, and toe loop. Most of these are named after the person who first performed them, which is why the history of the sport is embedded in its vocabulary. The axel is named after Axel Paulsen, a Norwegian skater who first performed it in the 1880s. The lutz is named after Alois Lutz, the flip after Don Jackson, and so on.

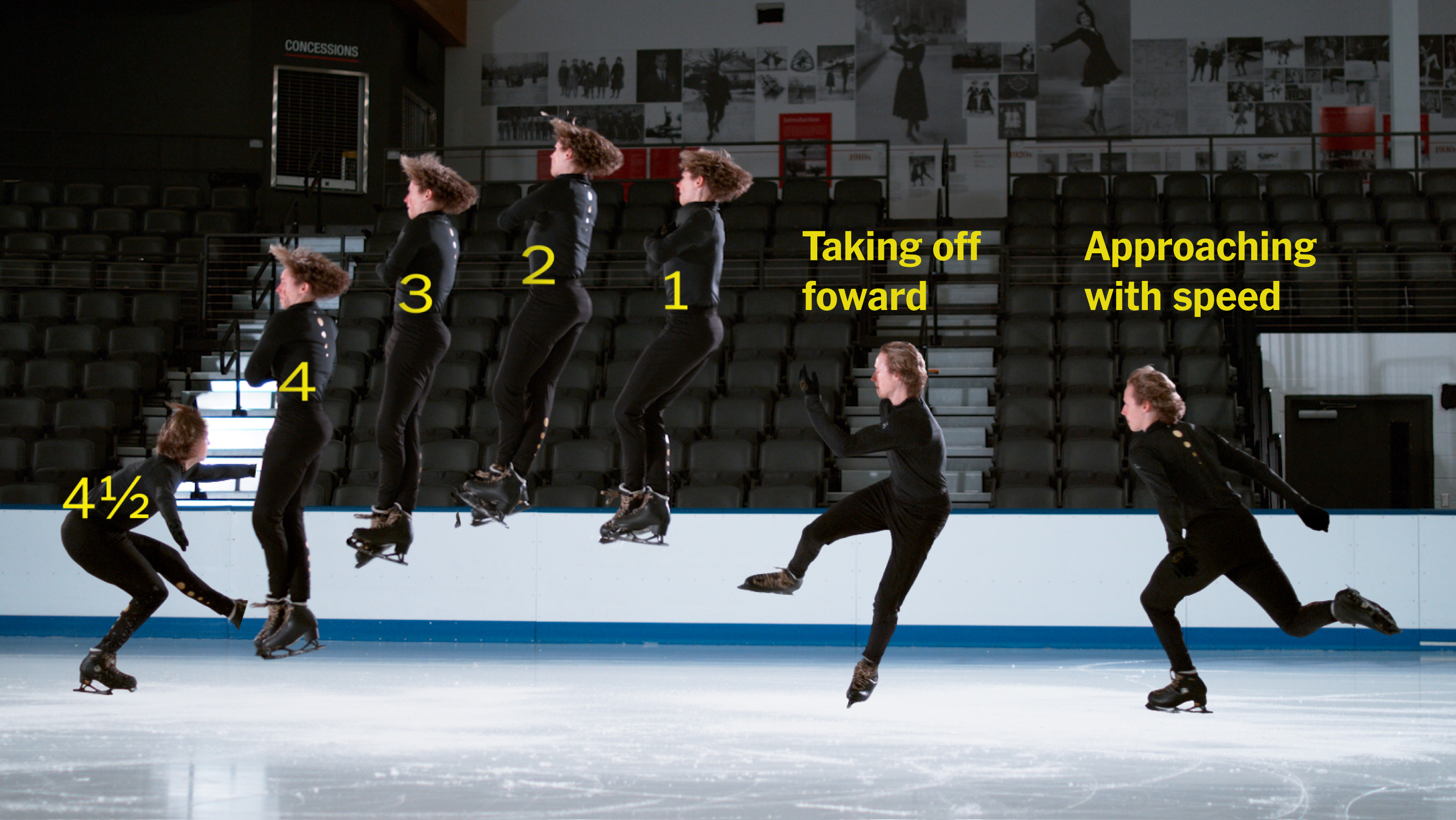

What distinguishes the axel from all other jumps is its forward takeoff. Every other jump in figure skating involves a backward takeoff, meaning the skater approaches the jump by traveling backward. The axel is the only jump where the skater takes off while moving forward. This seemingly small detail cascades into massive implications for the entire jump.

Because the skater is moving forward when they take off, they need to complete an extra half rotation just to end up facing backward (the landing direction for all jumps). So a simple axel, the most basic version, requires 1.5 rotations. A double axel requires 2.5 rotations. A triple axel requires 3.5 rotations. And a quadruple axel requires 4.5 rotations.

This is why quad axels are harder than quad flips or quad luzts. The lutz and flip only require 4 full rotations because they start with a backward takeoff. The extra half rotation in the axel means you're spinning faster overall, and you need more height to accommodate those extra spins.

The axel can be performed with three different types of takeoffs: the inside edge, the outside edge, or the toe pick (toe axel). Most competitive skaters use one of these variations almost exclusively throughout their career. The variation a skater chooses affects their approach angle, their rotational mechanics, and their injury risk profile. But the fundamental physics remains the same: get airborne, rotate as many times as possible, land cleanly on a backward edge.

The takeoff mechanics also determine how much angular momentum the skater can generate before leaving the ice. Angular momentum, which we'll discuss in depth shortly, is the rotational equivalent of linear momentum. It's the quantity that determines how fast you'll spin while airborne. And once you're in the air, there's no way to generate new angular momentum. You can only work with what you generated during the push-off.

This is a hard constraint. The harder you push against the ice, the more momentum you generate. But there's a limit to how hard a human can push while maintaining the precise balance and positioning required for the jump. Elite skaters operate right at that edge, maximizing their push-off force while maintaining the technical precision needed to land cleanly.

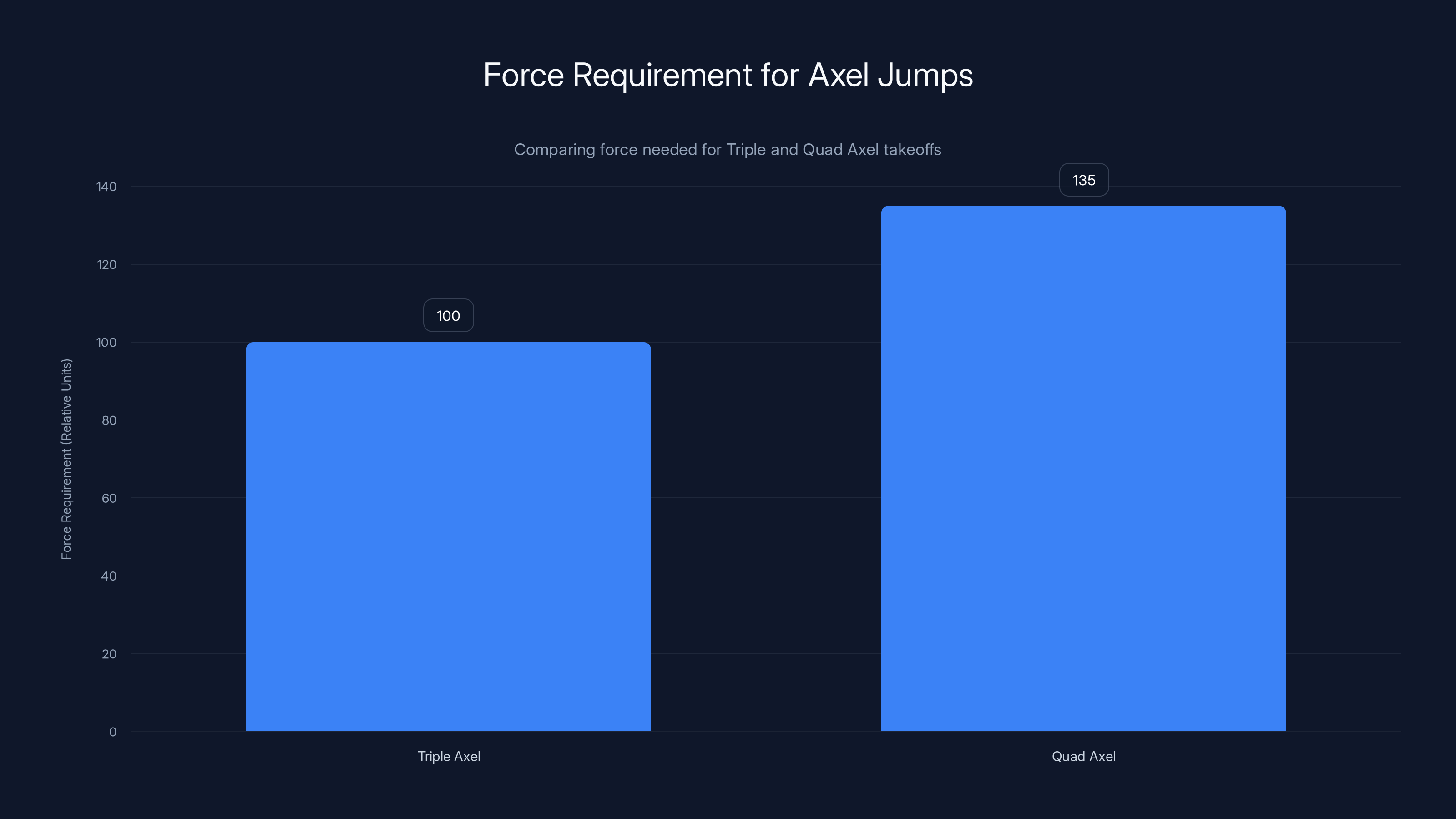

A quad axel requires approximately 35% more force during takeoff compared to a triple axel, highlighting the increased physical demands of executing this complex jump.

Angular Momentum and Rotational Physics: The Foundation of All Jumps

Okay, let's get into the actual physics now. And I know this might sound intimidating, but I promise it's intuitive once you see how it applies to figure skating.

Angular momentum is a fundamental property of rotating objects. It's defined by the equation:

Where:

- L is angular momentum (measured in kg⋅m²/s)

- I is moment of inertia (how much rotational resistance an object has)

- ω is angular velocity (how fast something is spinning)

Here's the critical insight: angular momentum is conserved in the air. This is the principle of conservation of angular momentum, and it's one of the most important laws in physics governing jumping and spinning.

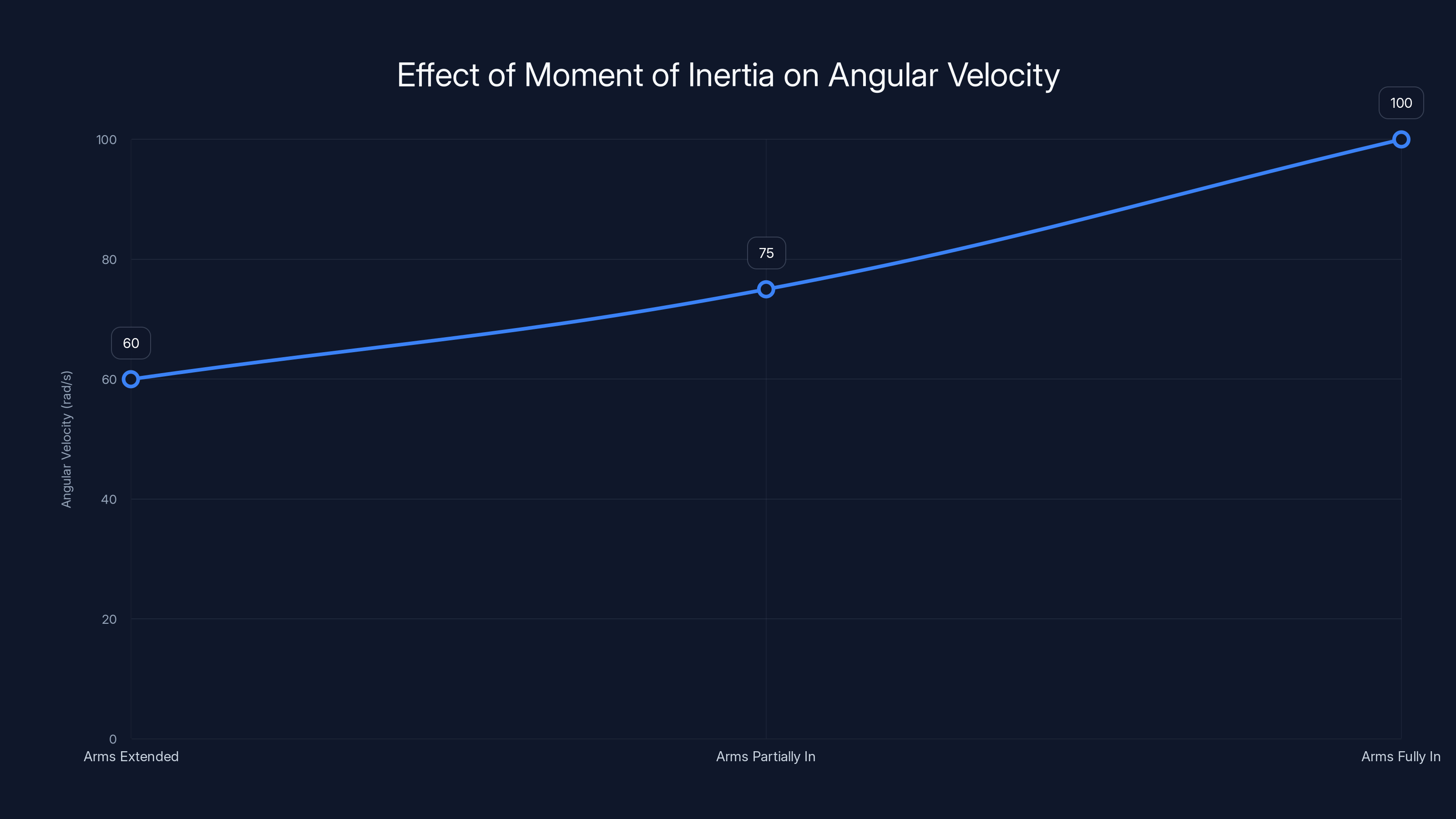

When a figure skater takes off and leaves the ice, they can't generate any new angular momentum. They can only work with what they created during the takeoff phase. But—and this is the clever bit—they can change how that momentum is distributed by changing their moment of inertia.

When your arms are extended out to the sides, you have a larger moment of inertia. Your body is spread out. When you pull your arms in tight toward your body, you have a much smaller moment of inertia. Your body is compact and dense.

Because angular momentum is conserved, if you decrease your moment of inertia, you must increase your angular velocity to compensate. This is why figure skaters pull their arms and legs in tight during jumps. They're literally using physics to spin faster.

Let's do some actual math here. A typical skater might generate an angular momentum of roughly 150 kg⋅m²/s during takeoff (this varies significantly based on the skater's strength and technique). During the takeoff, their moment of inertia might be around 2.5 kg⋅m² (arms extended for balance). This gives them an initial angular velocity of:

Now, as they pull their arms in for the rotation, their moment of inertia decreases to maybe 1.2 kg⋅m². The same angular momentum of 150 kg⋅m²/s now produces a much faster spin:

To convert that to rotations per second, we divide by 2π (since one full rotation is 2π radians):

Now, a quadruple axel requires 4.5 rotations in approximately 0.8 seconds of airtime. That's a required rotation rate of 5.6 rotations per second. This means skaters attempting quad axels need to generate significantly more angular momentum during their takeoff than skaters performing lower-level jumps.

Here's why this matters for Ilia Malinin specifically: he generates more angular momentum during his takeoff than almost any other skater. This is partly due to his exceptional lower-body strength, partly due to his technique, and partly due to his natural body proportions and muscle fiber composition. His moment of inertia during the rotation is also slightly smaller than average due to his lean muscle mass and long limbs.

The combination of higher initial angular momentum and effective arm compression creates the conditions necessary for the quad axel. Other skaters can't pull it off not because they're weak or unskilled, but because the physics simply doesn't work out. They don't generate enough angular momentum to complete 4.5 rotations in the available airtime.

Vertical Height: The Secret Ingredient Nobody Emphasized Until Recently

For decades, figure skating coaches and biomechanics researchers didn't fully appreciate the role of vertical height in quad jumps. The prevailing wisdom was that jump height didn't correlate strongly with successful rotations. The thinking was, "Your angular momentum is generated during takeoff. Height is almost secondary."

Then came the 2024 study from Toin University researcher Seiji Hirosawa, published in the journal Sports Biomechanics. And it completely upended conventional thinking.

Hirosawa analyzed video footage of two elite skaters attempting quadruple axels in competition using the Ice Scope motion tracking system. This system captures detailed three-dimensional position data of the skater's body throughout the jump. The study measured several key metrics: vertical height achieved, horizontal distance traveled, takeoff speed, and various kinematic angles.

What Hirosawa found was striking: both skaters achieved significantly greater vertical heights during their quad axel attempts compared to their triple axel attempts. We're talking about the difference between 12-14 inches for a triple axel versus 20+ inches for a quad axel.

Why does this matter so much? It's about time.

When you're rotating in the air, you need a minimum amount of time to complete your rotations. If you're spinning at 5.6 rotations per second, and you need to complete 4.5 rotations, you need at least 0.8 seconds of airtime. But in practice, successful quad axels have airtime closer to 0.9 to 1.0 seconds because the skater's spin rate isn't perfectly constant and there's some margin for error.

The relationship between jump height and airtime is governed by basic kinematics. When you jump with an initial vertical velocity

Where g is the acceleration due to gravity (9.81 m/s²).

For a 20-inch jump (about 0.51 meters), the required initial vertical velocity is:

This gives a total flight time of:

But wait—that's the total flight time. The actual rotation happens during the entire flight. But the skater spends less time spinning at maximum velocity because they're decelerating as they fall. The average rotation rate is actually somewhat lower than peak rotation rate.

What Hirosawa's research revealed is that this extra height is absolutely critical. It provides the additional airtime necessary to complete 4.5 rotations before landing. Skaters attempting quad axels have to be more explosive during takeoff. They have to recruit more muscle fibers, generate greater force, and achieve greater peak power output.

This finding has influenced how coaches now train skaters for quad axels. The old model was "focus on spin technique." The new model is "build explosive power to achieve greater height."

Elite strength and conditioning coaches working with quad axel athletes now incorporate plyometric training, Olympic lifting variations, and specialized exercises designed to maximize vertical jump height. Skaters are doing box jumps with weights, explosive goblet squats, and banded resistance training to build the specific strength profile needed for the quad axel.

Ilia Malinin's training program specifically emphasizes vertical jump development. He works with a strength coach to maximize his explosiveness off the ice. During the off-season, he dedicates significant time to building power in his legs, hips, and core. This translates directly into greater initial vertical velocity during his jumps, which translates into more airtime, which makes completing 4.5 rotations actually possible.

As a skater pulls their arms in, their moment of inertia decreases, leading to an increase in angular velocity to conserve angular momentum. Estimated data based on typical skater movements.

The Biomechanics of Takeoff: Where It All Begins

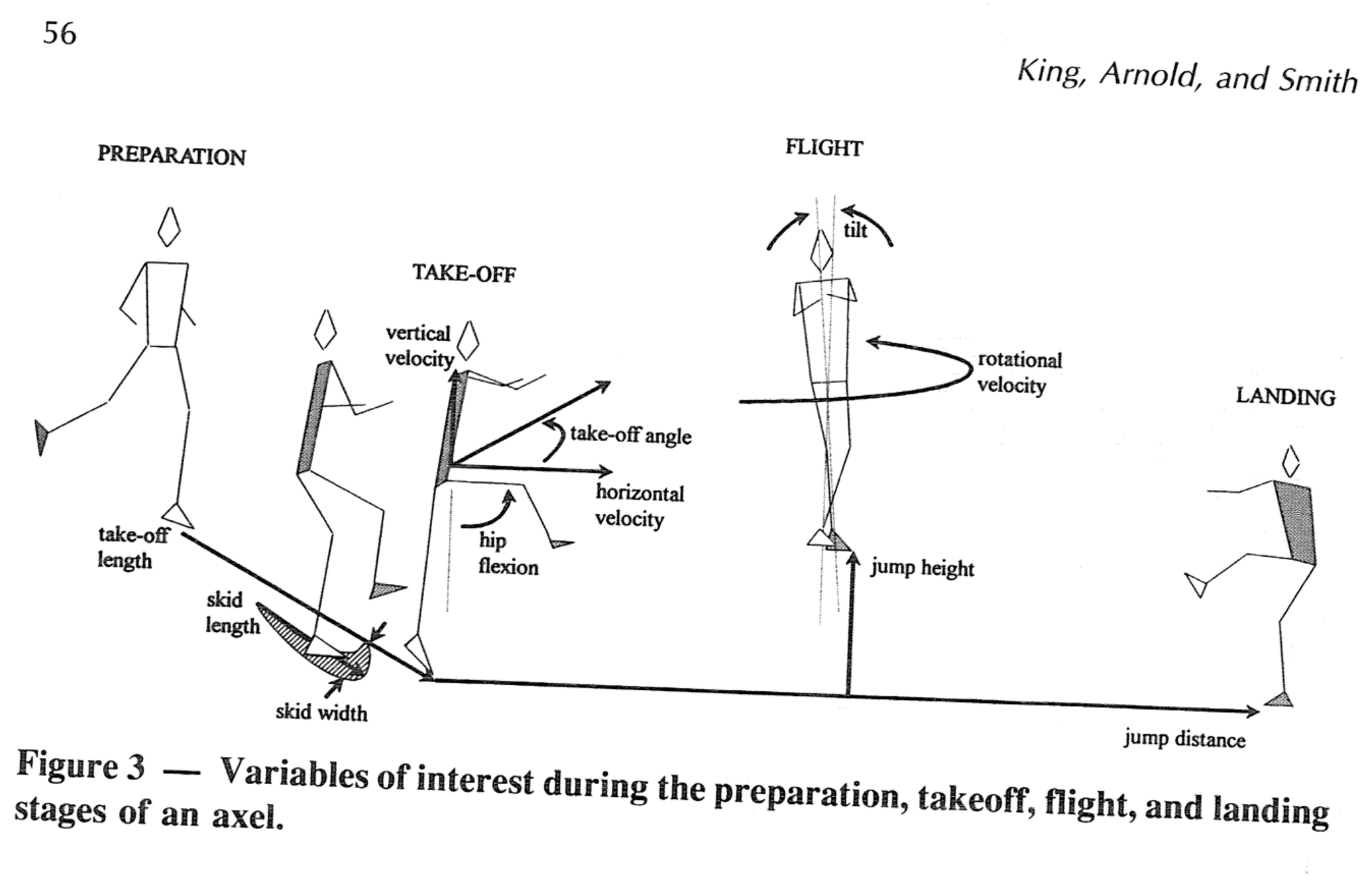

The takeoff phase of a jump is absurdly brief—we're talking about 0.2 to 0.3 seconds of contact with the ice. In that quarter-second, the skater is doing something incredibly complex: generating angular momentum, creating vertical velocity, maintaining balance, and setting up the rotation dynamics for the jump.

For a quad axel specifically, the takeoff is even more critical because the requirements are more stringent. The skater needs to generate roughly 30-40% more force compared to a triple axel takeoff.

Let's break down what happens during the takeoff phase of a quad axel:

The Approach (2-3 seconds before takeoff)

The skater begins their approach by building speed on the ice. They're typically traveling at 10-12 feet per second by the time they reach the takeoff point. This forward momentum is important because it carries them through the jump and provides a baseline for their horizontal velocity at landing.

During the approach, the skater is also positioning their body to set up the jump geometry. For an axel, this means being on a forward edge, ready to transition into the takeoff position. The skater's weight is balanced over the blade of the skate, their posture is upright but flexible, and their arms are positioned to help generate rotational momentum.

The Transition (0.5-1 second before takeoff)

Here's where the skater starts to build rotational momentum. They're still moving forward, but now they're introducing rotation. The upper body starts to rotate against the lower body, creating what's called "pre-rotation" or "off-ice rotation." This is the setup phase for angular momentum generation.

For an axel specifically, the skater transitions from a forward edge to a position where they can push off effectively. Their arms begin to spread slightly to help with balance and to set up the momentum accumulation.

The Push-Off (0.2-0.3 seconds)

This is where the actual jump happens. The skater applies force to the ice through their skate blade, accelerating both upward and rotationally. The muscles involved include:

- Plantar flexors (calf muscles) for upward force

- Quadriceps for knee extension and forward power

- Hamstrings for hip extension and rotational force

- Glutes for hip extension and power generation

- Core musculature for rotational control and stability

- Hip abductors and adductors for lateral force control

Elite figure skaters generate peak power outputs during this phase that rival professional athletes in other sports. Biomechanics research has found that figure skaters can generate peak power outputs exceeding 4,000-5,000 watts during a maximal quad jump attempt—for comparison, that's in the range of elite volleyball players and track athletes.

During the push-off, the skater's entire leg extends against the ice, creating both vertical force (to achieve jump height) and rotational force (to generate angular momentum). The arms are fully extended and rotating, adding to the rotational momentum. The movement pattern is incredibly precise—any deviation from optimal technique results in either inefficient energy transfer or a botched landing.

The Liftoff (instantaneous)

At the moment the skate leaves the ice, everything that's going to happen during the jump is already determined. The skater's angular momentum is locked in. Their vertical velocity is locked in. Their body position at liftoff sets up everything that comes next.

At this instant, Ilia Malinin has achieved something remarkable: he's generated enough angular momentum to complete 4.5 rotations. His vertical velocity is approximately 2.3 m/s (achieved through nearly 2,000 pounds of force applied over about 0.25 seconds). His body is in a position to immediately pull his arms in tight and increase his spin rate.

The asymmetry between left and right sides is also important. Figure skaters have developed considerable asymmetry from years of practicing the same jumps on the same side. Right-handed jumpers are typically stronger on their right side. This affects how they distribute forces during takeoff and contributes to slight deviations in jump geometry.

One of the reasons Ilia Malinin is exceptional is his relative symmetry compared to other elite skaters. He can jump from both feet nearly equally well. He can attempt jumps in both directions with good technique. This gives him flexibility in competition and also means his training can be more balanced.

The Flight: Angular Acceleration and Spin Dynamics

Once the skater leaves the ice, they're in free fall. The only forces acting on them are gravity (downward) and air resistance (which is relatively minimal and usually ignored in figure skating biomechanics studies). There's no way to generate new angular momentum once airborne.

But the skater can completely control how fast they spin by adjusting their body shape. This is where the real artistry meets the physics.

The Arm Pull

Immediately after liftoff, the skater begins pulling their arms inward. This is sometimes called "closing" in figure skating terminology. As the arms come in, the moment of inertia decreases, and angular velocity increases proportionally (because angular momentum is conserved).

The timing of this arm pull is critical. Pull too early, and you might lose some of your angular momentum setup. Pull too late, and you won't complete the rotation. Elite skaters have developed an almost unconscious sense of timing, refined through thousands of practice repetitions.

For a quad axel, the arm pull typically happens within the first 0.1-0.15 seconds of flight. The skater goes from arms extended (moment of inertia ~2.5 kg⋅m²) to arms pulled in (moment of inertia ~1.2 kg⋅m²) very quickly.

The Rotation Phase

Once the arms are pulled in, the skater is in their maximum spin configuration. They're rotating at roughly 5-6 rotations per second. From the skater's perspective, the world is spinning past them at an incredible rate. Their visual system is being activated and deactivated multiple times per second as their head rotates.

One of the things that separates elite skaters from everyone else is their ability to maintain body position during the rotation. The core muscles are activated to maintain rigidity. The legs are held tight together. The head is either spotting (focusing on a fixed point and then rotating around quickly) or maintaining fixed visual focus.

The physics here is actually quite elegant. Because angular momentum is conserved and no external forces can change rotational motion while airborne, the skater maintains a constant angular velocity throughout the flight (ignoring the small effects of air resistance). So if they're rotating at 5.6 rotations per second, they'll continue at that rate until landing.

But here's where technique comes in: maintaining perfect body position ensures that the skater doesn't accidentally increase their moment of inertia (by loosening an arm, for example) which would decrease their spin rate and prevent them from completing the rotation.

Gaze Control and Vestibular System

One fascinating aspect of quad jumps that's often overlooked is the role of gaze control and the vestibular system. The vestibular system is the part of your inner ear that controls balance and spatial orientation. It's being activated many times per second during a quad axel rotation.

Elite skaters have highly trained vestibular systems. They're less susceptible to dizziness because their brains have adapted to the rapid rotational input. They also practice gaze control techniques to maintain awareness during the rotation.

Some skaters use a technique called "spotting" where they keep their eyes focused on a fixed point as long as possible, then rapidly rotate their head to re-acquire the same point. This reduces the rotational velocity input to the vestibular system and helps prevent disorientation.

Other skaters simply accept the disorientation and rely on proprioceptive awareness (the sense of where their body is in space without looking) to maintain position. This is partially learned through practice but also involves some genetic component in terms of vestibular sensitivity.

Slowing Down the Rotation (Final Preparation for Landing)

Actually, contrary to what you might think, skaters don't intentionally slow down their rotation before landing. They maintain their spin rate right up until the landing edge contacts the ice. However, what they do is adjust their body position slightly to prepare for the impact.

About 0.1-0.15 seconds before landing, the skater begins to extend their arms outward slightly and prepare their landing edge. This is happening while they're still rotating, just moments before impact. The timing is incredibly precise because if they extend their arms too early, they'll slow down their rotation and potentially not complete the necessary 4.5 turns.

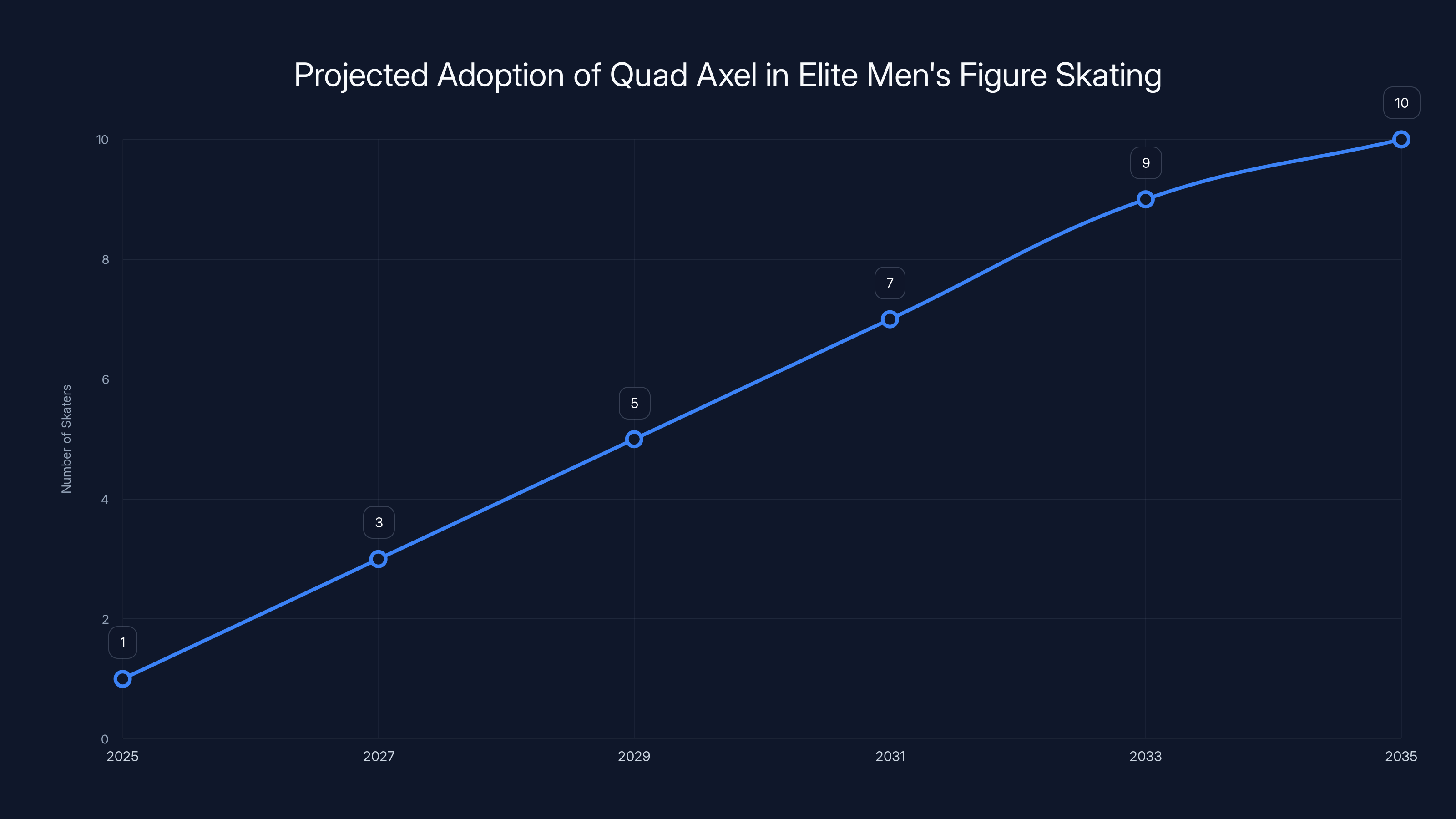

Estimated data suggests that by 2035, around 10 elite male skaters will consistently land the quad axel, indicating its normalization in competitive figure skating.

The Landing: Impact Dynamics and Deceleration

The landing is where everything can fall apart. You can nail the takeoff, execute the rotation perfectly, but if the landing is off, the entire jump is failed in the eyes of the judges.

For a quad axel, the landing involves the skate blade contacting the ice while the skater is still rotating at roughly 5+ rotations per second. The blade hits the ice on a specific edge (the back outside edge of the landing foot), and at that instant, friction and impact forces come into play.

Impact Force

The landing involves a massive, sudden deceleration. The skater goes from moving forward at about 8-10 feet per second to nearly stationary in about 0.3-0.5 seconds. This creates peak impact forces that exceed 5-6 times body weight.

For a 130-pound skater, that's roughly 650-780 pounds of force concentrated through the blade of the skate. The human body is remarkably tough and adapted to these forces through years of training, but this is still significant trauma to the joints, muscles, and connective tissues.

The impact is distributed through several structures:

- The landing ankle joint

- The landing knee joint

- The hip of the landing leg

- The lower back and core stabilizers

- The non-landing leg (which is being held tightly for rotation)

Elite skaters have developed exceptional landing mechanics to distribute these forces efficiently. Weak ankles, poor knee alignment, or inadequate core strength are common reasons why otherwise talented skaters can't consistently land quad jumps.

Blade Edge Control

The specifics of which blade edge the skater lands on are critical. For an axel, the landing is always on a back edge (as opposed to a forward edge). The exact edge—inside versus outside, and the angle of that edge—determines whether the jump counts as a legal landing.

Most quad axels are landed on the back outside edge, which means the outer edge of the blade contacts the ice and the skater is moving forward (relative to the edge) as they land. This edge provides specific friction characteristics that help decelerate the rotational motion.

If the skater lands on the wrong edge, the jump is called a "wrong edge" by the judges and receives a deduction (in the modern scoring system). If they completely fail to land on the required back edge, the jump is downgraded to a lower value.

Rotational Momentum During Landing

Here's something that's often misunderstood: the skater doesn't stop rotating when they land. They're still spinning at high velocity when the blade contacts the ice. The friction between the blade and ice gradually decelerates the rotation.

This is why the landing phase typically takes 0.3-0.5 seconds. The skater needs time to dissipate the rotational energy and come to a stop in their landing position.

The landing arm positions also matter. Some skaters land with one arm extended forward (to help with the deceleration and balance), while others land with both arms coming together on their body. The arm position affects the moment of inertia during landing and thus affects how quickly they decelerate their rotation.

Muscle Physiology: The Hidden Requirement for Quad Axels

Now let's talk about what has to happen inside the skater's body to make a quad axel possible. This is where genetics, training, and neuromuscular adaptation all come together.

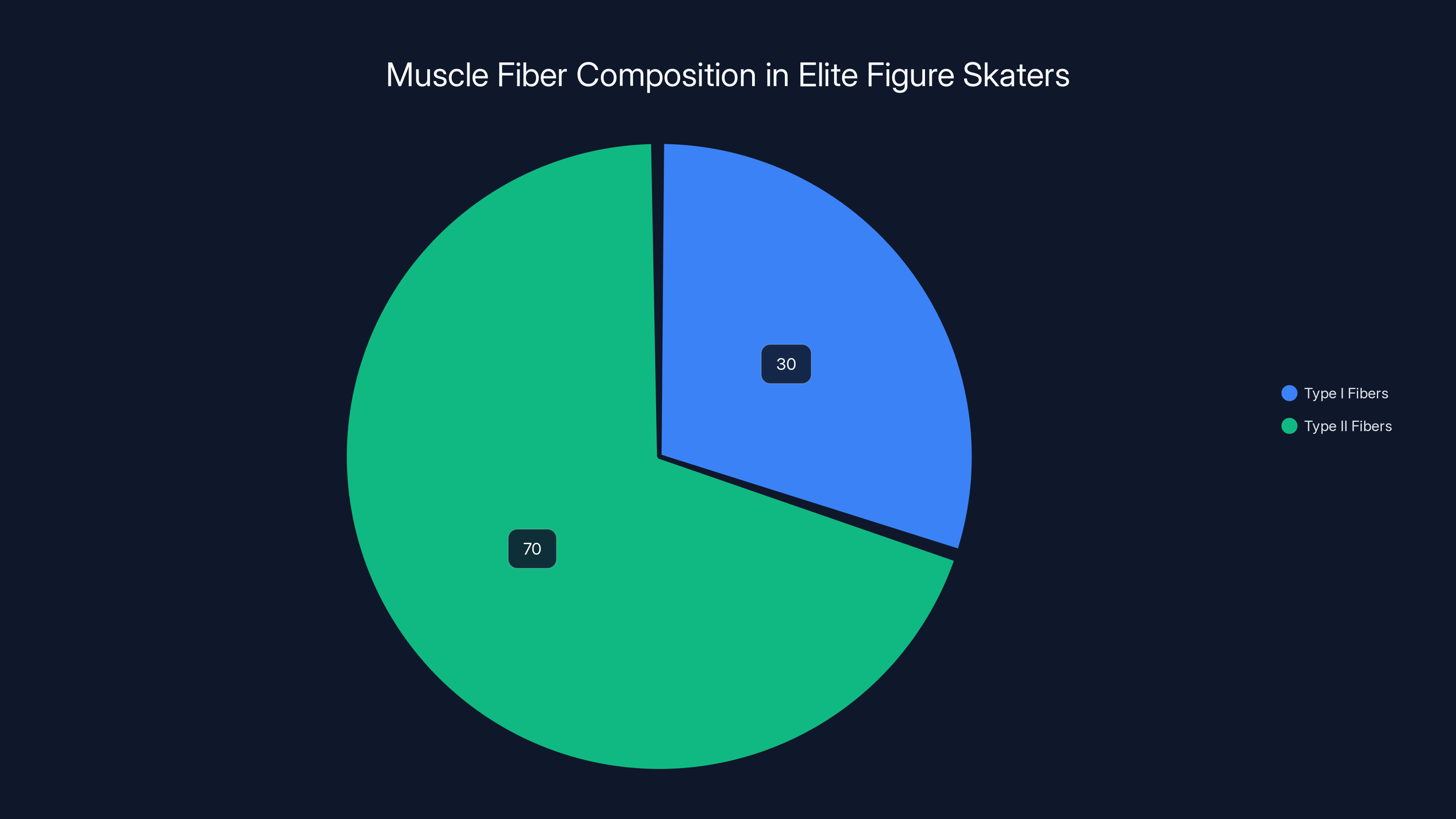

Muscle Fiber Composition and Power Output

Muscle fibers come in different types, and the ratio of fiber types in an athlete's muscles is partly genetic and partly determined by training. Type I fibers are slow-twitch: they have high endurance, low power output, and rely on aerobic metabolism. Type II fibers are fast-twitch: they have lower endurance, high power output, and rely on anaerobic metabolism.

Elite figure skaters, especially those attempting quad jumps, typically have a higher proportion of Type II muscle fibers in their lower body compared to the general population. This is partly genetic—some people are born with more fast-twitch fibers—and partly trained through years of explosive movements.

Malinin likely has a favorable genetic predisposition toward fast-twitch fibers combined with expert training that's further developed these fibers' power output capacity. This allows him to generate the ~5,000 watts of power necessary during takeoff.

The Phosphocreatine System and ATP Regeneration

When muscles contract, they use ATP (adenosine triphosphate) as their energy currency. The phosphocreatine system is the fastest way to regenerate ATP during explosive, brief efforts like jumping.

During the 0.25-second takeoff of a quad axel, the skater's muscles are operating at nearly their absolute maximum power output. This is energy system dominated by the phosphocreatine system, which can supply energy for about 10-15 seconds of maximal effort.

One quad axel attempt isn't anywhere near exhausting the phosphocreatine system. But during competition, where skaters might perform multiple quad axels in the span of a few minutes (in their free skate routine), the accumulated demand on this energy system becomes significant.

Elite skaters train to enhance the capacity of their phosphocreatine system through appropriate strength and power training. High-intensity interval training, heavy resistance training, and explosive plyometrics all contribute to better phosphocreatine system function.

Proprioception and Motor Control

Propriception is the sense of where your body is in space. It's mediated by mechanoreceptors in your muscles, joints, and connective tissues that constantly send signals to your brain about position and tension.

During a quad axel, proprioception is critical. The skater is rotating at extreme velocity, they can't see clearly where they are or what's coming, and they have to maintain perfect body position. This requires exceptional proprioceptive awareness.

Elite skaters develop extraordinary proprioceptive acuity through years of training. They practice landing on one foot at extreme angles. They do balance exercises on unstable surfaces. They spend thousands of hours refining their motor control. By the time they're attempting quad axels, their motor cortex has developed incredibly detailed neural maps of their body and how it needs to move.

Malinin's proprioceptive abilities are likely exceptional. He can "feel" his body position during the rotation and make minute adjustments to ensure proper landing alignment.

Core Stability and Anti-Rotation Strength

The core muscles—including the rectus abdominis, obliques, transverse abdominis, and erector spinae—provide essential stability during jumps. But for quad axels specifically, the core's role is even more critical.

During the landing, the core muscles have to rapidly decelerate the rotation while maintaining spinal alignment. This requires not just strength but also rapid force production and proper timing of muscle activation.

Elite skaters spend significant time training core stability, often using exercises that involve resisting rotation or maintaining position under load. Pallof presses, anti-rotation exercises, dead bugs, bird dogs, and planks are common in skaters' training programs.

Malinin's training program includes dedicated core work at least 3-4 times per week, targeting both the muscles that generate power (for the takeoff) and the muscles that stabilize and control deceleration (for the landing).

Elite figure skaters attempting quad axels have an estimated 70% Type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers, crucial for high power output. Estimated data.

Training Protocols: How Skaters Build Quad Axel Capability

The process of learning to land a quad axel typically takes 3-5 years of dedicated training. It's not something a skater can learn in a single season. It requires progressive development across multiple dimensions.

Phase 1: Foundation Building (Years 1-2)

During this phase, skaters are developing their basic jumping technique and building the foundational strength required for quad jumps. They're focusing on triple axels and other triple jumps, perfecting the mechanics, and developing consistency.

Training during this phase includes:

- Daily on-ice training (2-3 hours)

- Strength training 3-4 times per week focusing on compound movements

- Flexibility and mobility work

- Core stability exercises

- Landing mechanics practice

- Video analysis and technique refinement

The goal is to develop a skater who can consistently land difficult triple jumps with good technique. Success at triple jumps is a prerequisite for quad attempts.

Phase 2: Strength Development and Introduction to Quad Jumps (Years 2-3)

During this phase, skaters begin attempting easier quad jumps, typically quad flip or quad lutz (which require fewer rotations than quad axel). They're also increasing their strength training intensity and specificity.

Training during this phase includes:

- Daily on-ice training (2.5-3 hours) with quad jump attempts

- Intensive strength training 4 times per week with periodized programming

- Olympic lifting movements (front squats, back squats, deadlifts, power cleans)

- Plyometric training (box jumps, depth jumps, explosive movements)

- Sport-specific power work

- Flexibility and recovery protocols

During this phase, skaters are building the power output necessary for quad jumps. They're testing their bodies to see if they have the physical capability to complete these extremely demanding jumps.

Phase 3: Quad Axel Preparation (Years 3-4)

Once a skater can consistently land other quad jumps, they can begin seriously preparing for the quad axel. This phase involves:

- Targeted quad axel training with gradual progression

- Plyometric training specifically for vertical jump height

- Continued strength development

- Technique refinement on the specific takeoff mechanics needed for quad axels

- Mental preparation and visualization

- Landing mechanics practice on specialized equipment

During this phase, skaters might land quad axels in practice but not in competition for extended periods. They're building consistency and reliability. They're also managing injury risk, as repeated quad axel attempts put significant stress on the body.

Phase 4: Competition Preparation and Mastery (Year 4+)

Once a skater can consistently land quad axels in training, they begin introducing them into competition routines. This phase involves:

- Strategic placement of quad axels in competitive programs

- Mental preparation for the pressure of competition

- Recovery and injury management

- Fine-tuning technique based on competitive outcomes

- Building redundancy (being able to land the jump reliably even when fatigued or under pressure)

Ilia Malinin spent roughly three years intensively preparing for the quad axel before landing it in competition in 2022. Since that breakthrough, he's continued to refine his technique and improve his consistency.

Comparative Analysis: Quad Axel vs. Other Quad Jumps

To really understand why the quad axel is uniquely difficult, let's compare it to other quadruple jumps. All quad jumps are hard. But they're hard in different ways.

Quad Flip vs. Quad Axel

A quad flip requires 4 full rotations. A quad axel requires 4.5 rotations. That extra half rotation seems small, but it's actually significant. It means the skater needs about 12% more angular velocity to complete the jump in the same amount of time.

But there's more to it than just rotation count. The takeoff mechanics are different. For a flip, the skater approaches backward and takes off from a toe pick (hence the name "flip"—you flip off the toe pick). For an axel, the approach is forward and the takeoff is from an edge.

The forward takeoff of an axel makes it harder to generate rotational momentum because you have to create rotation while moving forward—somewhat counterintuitively. With a backward takeoff like the flip, you can naturally build rotation as you approach the jump.

Most elite skaters find the quad flip easier than the quad axel. They can land quad flips before quad axels. Only the most exceptional skaters (like Malinin) can land quad axels.

Quad Lutz vs. Quad Axel

The quad lutz is similar to the quad flip—it's a backward takeoff that only requires 4 rotations. The main difference between flip and lutz is the edge you take off from (flip is from inside edge, lutz is from outside edge), but the rotation count is the same.

Like the quad flip, the quad lutz is generally considered easier than the quad axel for the same fundamental reasons: fewer rotations required and more natural rotational momentum generation from the backward approach.

Quad Salchow and Quad Loop

The quad salchow and quad loop are less commonly attempted at the highest levels, but they also only require 4 rotations. They're backward jumps, making them inherently easier than the quad axel from a rotation perspective.

Quad Toe Loop

The quad toe loop is the "easiest" quad jump—requiring only 4 rotations and using a backward takeoff with a toe pick. Many competitive men now include this jump in their programs, even though it's worth significantly less in the scoring system than quad flips or lutz jumps.

The quad axel stands alone as the only forward takeoff quad jump. This is why it's unique and why it's universally acknowledged as the most difficult quad jump in figure skating.

The quad axel is the most difficult jump due to its 4.5 rotations and forward takeoff, requiring higher angular velocity and complex mechanics. Estimated data.

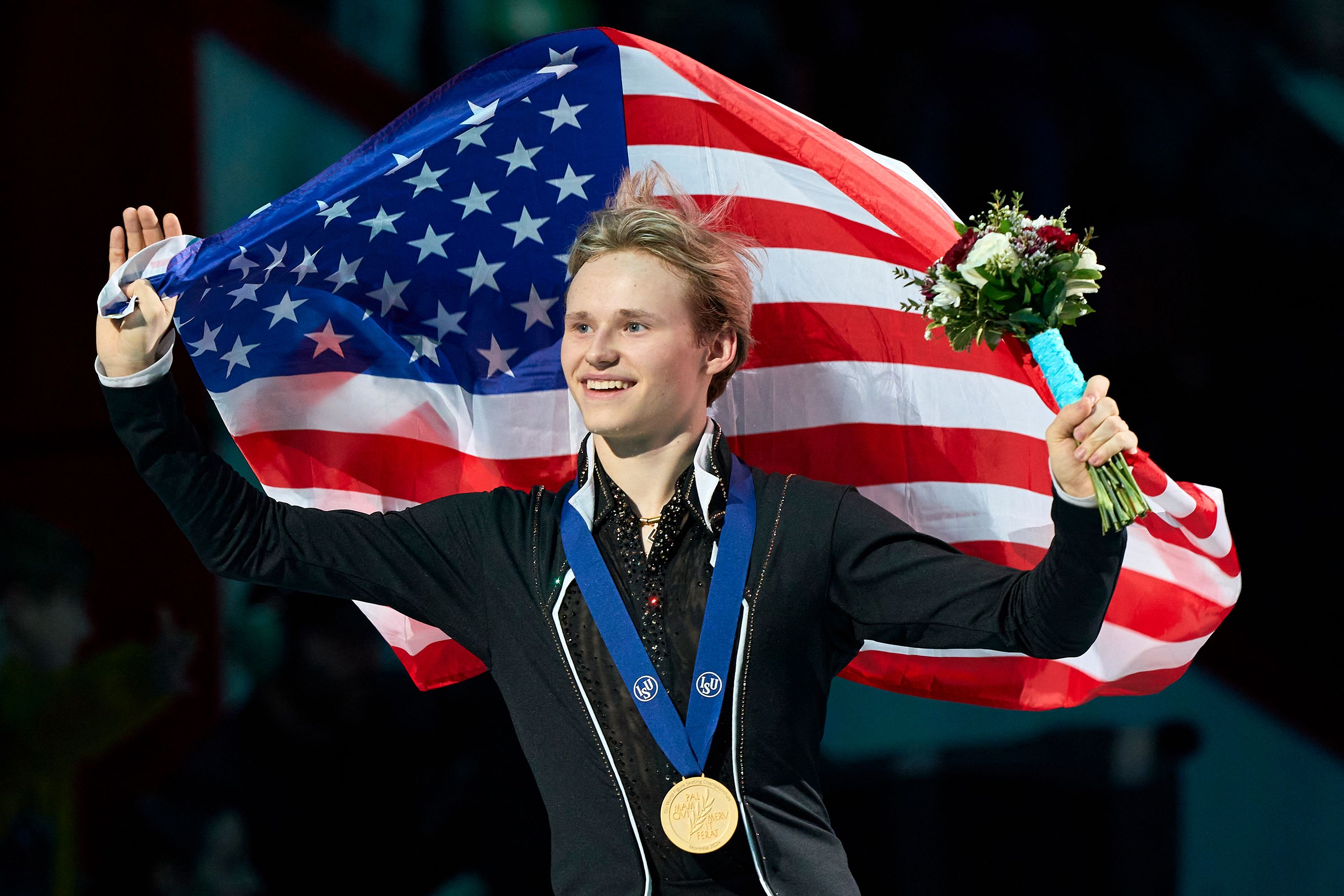

The Breakthrough: Ilia Malinin and the 2022 Quad Axel

On October 30, 2022, at the Skate America competition in Providence, Rhode Island, Ilia Malinin did something nobody had ever done before in competition: he landed a quadruple axel. In the technical standards of figure skating, this moment was seismic.

Malinin was 17 years old, competing in his second year of senior-level figure skating. He'd already shown exceptional promise as a jumper, landing other quad jumps cleanly. But the quad axel was theoretical—something that might be possible in the distant future, not something anyone actually expected to see.

When Malinin landed that first quad axel in competition, it fundamentally shifted what people thought was possible in figure skating. Suddenly, the impossible became merely extremely difficult. Within a few years, top skaters were expected to have a quad axel in their arsenal, or at least to be working toward one.

Malinin's breakthrough came down to a specific combination of factors:

-

Natural ability: Malinin has exceptional vertical jump height, landing power, and proprioceptive awareness. These aren't entirely learnable—they have genetic components.

-

Training expertise: Malinin works with Oleg Epstein, a coach with exceptional understanding of jump technique and biomechanics. Epstein specifically engineered the training program to develop the specific physical and technical requirements for quad axels.

-

Correct technical approach: Before Malinin, some skaters had attempted quad axels, but they were using suboptimal technique. Malinin's approach—emphasizing high takeoff force, vertical height, and precise body position—proved to be the biomechanically correct way to execute the jump.

-

Persistence and opportunity: Malinin was willing to attempt the jump repeatedly in competition, accepting failures and learning from each attempt. This took courage and opportunity.

-

Timing: Malinin came along at a moment when figure skating was ready to embrace this advancement. If he'd attempted the quad axel 20 years earlier, the reaction might have been skepticism rather than celebration.

Since that 2022 breakthrough, Malinin has continued to dominate in figure skating, and his success with the quad axel has been a defining part of his career. He's landed quad axels in almost every competition since, making it look increasingly routine (though it's anything but routine).

Malinin's success has also inspired other skaters to pursue quad axels. Several elite skaters have now landed quad axels in competition, including Japanese skater Yuzuru Hanyu and a few others. The move is slowly transitioning from "the most impressive jump" to "an expected skill for top men's skaters."

Training Malinin: Inside the Program of Quad God

So what does the training program of the world's best quad axel skater actually look like? Let's break down Malinin's approach.

Off-Ice Strength Training

Malinin works with a specialized strength and conditioning coach focused on developing the specific power and strength profile needed for quad jumps. His off-ice training typically includes:

Monday and Thursday: Lower Body Power Focus

- Warm-up: Dynamic stretching and mobility work (10 minutes)

- Olympic lifting variations: Front squats, power cleans, or variations (4 sets of 3-5 reps)

- Explosive movements: Box jumps, banded jump squats, or depth jumps (3-4 sets of 3-5 reps)

- Accessory work: Single-leg Romanian deadlifts, single-leg squats, Bulgarian split squats (3 sets of 8-10 reps)

- Core work: Anti-rotation exercises, planks, bird dogs (2-3 sets of 10-15 reps)

- Cool-down and stretching (5-10 minutes)

Tuesday and Friday: Strength Endurance and Conditioning

- Warm-up: Light cardio and dynamic stretching (10 minutes)

- Compound strength movements: Deadlifts or squat variations (3-4 sets of 5-6 reps)

- Assistance exercises: Leg press, leg curls, calf raises (2-3 sets of 8-12 reps)

- Core and stability work (2-3 sets of 10-15 reps)

- Conditioning: Light intervals or sustained moderate-intensity work (10-15 minutes)

- Cool-down and stretching (5-10 minutes)

Wednesday: Active Recovery or Technical Work

- Often skipped entirely for complete rest, or

- Light mobility and flexibility work (20-30 minutes)

- Possibly some light technical work on specific jump components

On-Ice Training

Malinin practices on the ice 2.5-3 hours per day, typically split into morning and afternoon sessions. His on-ice work includes:

Technical development: Working on individual jumps, rotations, and specific technical elements. This might include multiple quad axel attempts during dedicated training blocks.

Program run-throughs: Skating his entire competitive program at full intensity to build stamina and mental toughness.

Choreography and artistry: Developing the skating skills, footwork, and interpretation that are also judged in figure skating competitions.

Jumps and spins: Extended warm-up work to develop consistency and reliability.

Malinin's training is periodized throughout the year. During off-season periods (typically July-August), he might focus more on strength development with less intensity on-ice. During competitive season (September-March), he maintains his strength but emphasizes consistency and program readiness.

Mental Training and Recovery

What often gets overlooked is the mental side of quad axel training. Landing this jump under pressure requires exceptional mental resilience. Malinin works with sports psychologists to develop:

- Visualization techniques

- Pressure management strategies

- Goal-setting and periodization

- Confidence-building protocols

- Routine development for consistent execution

Recovery is also critical. Elite skaters like Malinin invest in:

- Adequate sleep (typically 8-10 hours per night)

- Nutrition optimization

- Massage and soft tissue work

- Ice baths or contrast therapy

- Flexibility and mobility work

All of this comes together to enable Malinin to consistently land quad axels in competition while maintaining his overall skating performance.

The Injury Risk: What Happens When Quad Axels Go Wrong

Let's be real: attempting quad axels is dangerous. When the jump goes wrong, the consequences can be serious.

Common Injuries

Skaters who attempt quad jumps frequently experience:

- Ankle sprains: The most common injury, resulting from landing on an incorrect edge or with insufficient ankle stability

- Knee ligament injuries: ACL, MCL, or PCL injuries can result from the massive impact forces and rotational loading

- Stress fractures: Repeated high-impact training can lead to stress fractures, particularly in the tibia, fibula, or metatarsals

- Lower back strains: The repetitive flexion and rotational loading can cause acute strains or chronic degeneration

- Hip labral tears: The hip joint experiences significant load during jumps, and the labrum can become damaged with repetitive stress

- Overuse injuries: Tendinitis, bursitis, and other soft tissue injuries from repeated training

Malinin has experienced a few injuries throughout his career, including ankle and knee issues, but nothing that's significantly derailed his trajectory. This is partly due to excellent injury management, appropriate training load management, and genetics.

Fall Mechanics

When a quad axel goes wrong, the skater typically falls to the ice. The biomechanics of these falls are fascinating from an injury prevention standpoint.

If the skater doesn't complete the rotation, they might land on their hip, back, or chest. If they land on the wrong edge, they might twist their ankle upon impact. If they lose control during rotation, they might tumble.

Elite skaters learn falling techniques over years of training. They know how to distribute impact, where to position their arms to absorb force, and how to minimize injury risk when things go wrong. It's not intuitive—it's a learned skill.

Long-Term Consequences

One of the open questions in figure skating is what the long-term consequences of repeatedly attempting quad jumps might be. The impact forces, landing mechanics, and accumulated joint stress are substantial.

Some retired elite skaters have reported chronic joint pain, arthritis, and mobility issues in their 40s and 50s. Whether this is specifically due to quad jumps or to figure skating in general isn't entirely clear because figure skating as a whole is a high-impact activity.

Malinin is only in his early 20s, so the long-term impacts of his quad axel training remain to be seen. But given the intensity of his training and the frequency of his quad axel attempts, he's certainly at risk for some degree of joint wear and tear over the long term.

The 2026 Olympics and the Future of the Quad Axel

As of 2025, the quadruple axel is the cutting edge of figure skating. Ilia Malinin is widely expected to win the men's figure skating competition at the 2026 Winter Olympics, and the quad axel will be a central part of his success.

But what's the future of the quad axel? Will it become standard among elite skaters? Will someone eventually land a quintuple axel?

The Next Frontier: Quintuple Jumps

Some people have speculated about whether a quintuple jump (5 full rotations or 5.5 rotations for an axel) might someday be possible. The physics say it could theoretically work if a skater could generate enough angular momentum and achieve sufficient height.

However, the practical barriers are enormous. A quintuple axel would require 5.5 rotations in roughly 0.9-1.0 seconds of airtime. That's a rotational velocity of 6.1 rotations per second. The angular momentum required would be roughly 40-50% higher than what's needed for quad axels.

We might eventually see someone land a quintuple flip or lutz (which would only require 5 rotations), but the quintuple axel probably remains decades away, if it's possible at all with human physiology.

The Democratization of the Quad Axel

Right now, Malinin is essentially alone at the elite level in his comfort with the quad axel. But this is starting to change. As more elite skaters attempt it and land it successfully, the jump will become more normalized.

Within the next 5-10 years, we might expect that the top 5-10 male figure skaters in the world will be able to land at least one quad axel. This would represent a significant evolution in the sport.

The Scoring Implications

Under the current ISU (International Skating Union) scoring system, a quad axel is worth approximately 14.3 base points with potential grade-of-execution (GOE) bonuses bringing the total to 15-17 points. This is the most valuable single jump in figure skating.

As more skaters land quad axels, the judges might adjust the base value downward (as they've done historically with jumps that become more common). Conversely, if the quad axel remains extremely rare, it might retain its high value as long as skaters who execute it are rewarded.

Malinin's edge in the quad axel is partially about the jump itself (he's one of the few who can land it consistently) and partially about his execution quality (he typically lands it with excellent technique and high artistic value). As others learn the jump, his advantage will narrow unless he continues to execute it better than his competition.

Evolution of Men's Figure Skating

The quad axel has already fundamentally changed men's figure skating. Before 2022, technical content was valued, but quad axels were so rare that programs were won on the basis of overall skating quality, artistry, and consistency on other jumps. After 2022, having a quad axel in your program is becoming non-negotiable at the highest levels.

This shift has implications for how skaters train, what they prioritize, and who succeeds in the sport. It creates a genetic and physical filtering mechanism—only skaters with certain physical attributes can even attempt this jump, let alone land it consistently.

Some in the skating community have expressed concerns about this overemphasis on technical difficulty at the expense of artistry and skating quality. These are valid concerns. But from a pure "sport evolution" perspective, the quad axel represents the frontier of what's athletically possible, and it's natural that the sport's elite gravitate toward it.

The Science of Training Progression: How to Build a Quad Axel Skater From Scratch

If you were a coach trying to develop a young skater into a quad axel-capable athlete, what would you do? Let's think about the science of training progression.

Talent Identification and Selection

First, you'd identify skaters with the right physical characteristics:

- High vertical jump capacity (naturally good at jumping sports)

- Good proprioceptive awareness and body control

- Quick-twitch muscle fiber predominance (which shows up as natural explosiveness)

- Appropriate height and weight for the sport (typically lightweight with strong, compact lower bodies)

- Willingness to train intensely and work through discomfort

You can't create these traits entirely through training. Some are genetic. The best quad axel skaters have the right physical blueprint to start with.

Early Development (Ages 8-12)

During this phase, focus on:

- Basic skating skills and balance

- Fundamental jump technique

- General athletic development (all-around movement skills)

- Building a strong foundation of single and double jumps

- Flexibility and mobility development

There's no specific quad axel training at this age. You're just building athletic capability and technical foundation.

Intermediate Development (Ages 13-16)

During this phase:

- Progress to triple jumps and perfection of technique

- Intensive strength training focused on functional movements and power

- Introduction of more specific quad jump training (quad toe loop, quad flip)

- Development of consistency and reliability

- Mental training and pressure management

Some skaters might start attempting quad axels late in this phase, but not the primary focus yet.

Advanced Development (Ages 16-20)

During this phase:

- Intensive quad axel-specific training

- Periodized strength and power training

- Competition experience with the jump

- Refinement of technique based on competitive feedback

- Development of mental resilience and consistency

This is where Malinin was during his breakthrough period—developing the specific adaptations needed for quad axels.

Mastery and Maintenance (Ages 20+)

Once a skater can land quad axels consistently:

- Maintain technical skill and consistency

- Continue power development to stay competitive

- Manage injury prevention and recovery

- Refine artistry and overall program quality

- Adapt to competitive environment and evolving standards

Key Training Principles

Throughout this progression, several science-based principles should guide training:

Periodization: Training should be divided into periods with specific focus areas (strength, power, technique, competition).

Progressive Overload: Training demands should gradually increase over time, but within managed increments to avoid injury.

Specificity: Training should become increasingly specific to the demands of quad axels as skaters progress.

Recovery: Adequate recovery between training sessions is essential, especially as training intensity increases.

Variation: Training should include variation to prevent plateaus and adaptations, and to reduce injury risk from repetitive stress.

Following these principles, a talented skater with excellent coaching could potentially land their first quad axel in competition by age 18-20. Malinin achieved this by age 17, which is exceptionally young.

FAQ

What exactly is a quadruple axel in figure skating?

A quadruple axel (or "4A") is a jump in which the skater takes off from a forward edge, rotates 4.5 times in the air, and lands on a backward edge. It's called "quadruple" because of the four full rotations, with the extra half rotation coming from the forward takeoff direction (all other jumps start backward). The jump is completed in approximately 0.8-1.0 seconds of airtime and is considered the most difficult jump in figure skating.

Why is the quadruple axel harder than other quadruple jumps?

The quadruple axel requires 4.5 rotations (due to the forward takeoff), while other quad jumps require only 4 full rotations. Additionally, the forward takeoff mechanics make it harder to generate rotational momentum, unlike backward takeoffs where rotational momentum develops more naturally. Most elite skaters find quad flips and quad lutz (which are backward jumps) easier to execute than quad axels because they require fewer rotations and allow for more intuitive momentum generation.

How much height do skaters need to jump to land a quadruple axel?

Research from Toin University's 2024 biomechanics study found that successful quad axel attempts achieve vertical heights of 20+ inches (approximately 0.5 meters). This is significantly higher than triple axel jumps, which typically reach 12-14 inches. The additional height provides the extra airtime necessary to complete the additional half rotation before landing.

How fast is a skater spinning during a quadruple axel?

During the rotation phase of a quadruple axel, skaters spin at approximately 5-6 rotations per second. To complete 4.5 rotations in 0.8 seconds requires a rotational velocity of about 5.6 rotations per second. This is achieved through the conservation of angular momentum—skaters generate rotational momentum during takeoff and then increase their spin rate by pulling their arms inward, reducing their moment of inertia and maintaining constant angular momentum.

How long does a quadruple axel take from start to finish?

The entire jump from takeoff to landing takes approximately 0.8-1.0 seconds. The takeoff phase (contact with ice) lasts about 0.2-0.3 seconds, the flight and rotation phase lasts about 0.4-0.5 seconds, and the landing phase (deceleration on ice) lasts about 0.3-0.5 seconds. The entire complex movement occurs in less time than it takes to blink.

When was the first quadruple axel landed in competition?

Ilia Malinin of the United States landed the first quadruple axel in competition on October 30, 2022, at the Skate America competition in Providence, Rhode Island. He was 17 years old at the time. Prior to this, while some skaters had attempted quad axels, none had successfully landed one in an official competition. This breakthrough fundamentally changed expectations for elite men's figure skaters.

How much impact force does a skater experience when landing a quadruple axel?

Landing a quadruple axel involves impact forces exceeding 5-6 times the skater's body weight. For a 130-pound skater, this translates to peak impact forces of 650-780 pounds concentrated through the skate blade (an area smaller than the thumb). This massive force is distributed through the ankle, knee, hip, and spine, which is why quad-jumping skaters frequently experience lower-body injuries and why specialized strength training is essential.

What training is required to learn a quadruple axel?

The typical progression involves 3-5 years of dedicated training, including daily on-ice practice (2.5-3 hours), off-ice strength training (60-90 minutes, 3-4 times per week), and mental training. The training emphasizes vertical jump power, rotational control, ankle and core stability, and proprioceptive awareness. Most elite skaters can land other quadruple jumps (like quad flip or quad lutz) before they can successfully land a quad axel, as those jumps have less stringent physical requirements.

Can women's figure skaters land quadruple axels?

While theoretically possible, quadruple axels have not yet been successfully landed by women in competition. The sport's gender differences in physiology, training culture, and program expectations have meant that women typically compete at lower technical difficulty levels than men. However, this is gradually changing as training methods improve and more women pursue advanced quad jumps. Some women have landed quadruple flips and lutz jumps in recent years, suggesting quad axels may become achievable for women in the future.

What role does body size and composition play in quad axel capability?

Body size and composition are significant factors. Smaller, leaner athletes have advantages in quad axel execution because they have lower moment of inertia (which helps with spin rate) and less mass to lift (which reduces the power requirement). Conversely, stronger athletes with more muscle mass might struggle due to increased moment of inertia. The ideal body composition for quad axels is lean muscle with high power-to-weight ratio. Malinin's relatively light weight combined with exceptional lower-body strength makes him biomechanically well-suited to this jump.

Conclusion: The Future of Impossible Jumps

When you watch Ilia Malinin launch himself into the air and complete 4.5 rotations before landing cleanly, you're seeing the convergence of multiple factors: exceptional genetics, years of specialized training, expert coaching, precise biomechanical technique, mental resilience, and probably some element of luck.

The quadruple axel isn't magic. It's physics. It's muscle physiology. It's years of training and refinement. But understanding the science doesn't make it any less impressive. If anything, understanding exactly what's required makes Malinin's achievement even more remarkable.

The science tells us several important things. First, jump height is absolutely critical—you need roughly 20+ inches of vertical leap to even have a chance at a quad axel. Second, angular momentum must be generated during takeoff and conserved during flight. Third, the specific biomechanics of the forward takeoff make quad axels inherently harder than other quad jumps. Fourth, the training progression that builds quad axel capability takes years and requires both genetic predisposition and expert coaching.

Looking forward, the quad axel will likely become more common among elite male figure skaters. As training methods improve and more specialized coaches develop expertise, the jump will gradually spread from the elite few to the elite many. Within 5-10 years, we might expect that the top 10-15 male figure skaters in the world will be capable of landing at least one quad axel.

Beyond that, the sport will undoubtedly continue evolving. Could quintuple jumps eventually become possible? Theoretically, perhaps. But the practical and physiological barriers are enormous. The quad axel will likely remain the frontier of figure skating difficulty for the foreseeable future.

For now, Ilia Malinin stands at the pinnacle of the sport, dominating with a jump that seemed impossible just a few years ago. He's proved that with the right combination of talent, training, and technique, even the impossible can become routine.

The quadruple axel is here to stay. And it's only the beginning of what figure skating will become.

Key Takeaways

- The quadruple axel requires 4.5 rotations in approximately 0.8 seconds, demanding angular velocity of 5.6 rotations per second—physically possible only for elite skaters

- Jump height is critical: successful quad axels achieve 20+ inches vertical leap versus 12-14 inches for triple axels, providing essential airtime for rotations

- Angular momentum conservation means the skater generates rotational force during takeoff (worth ~150 kg⋅m²/s) then increases spin rate by pulling arms inward

- Ilia Malinin's 2022 breakthrough proved quad axels were possible and changed competitive expectations for elite male figure skaters forever

- Training for quad axels requires 3-5 years of progression: foundation building, strength development, quad jump introduction, and competitive mastery phases

- Landing a quad axel involves impact forces exceeding 5-6 times body weight, creating significant injury risk to ankles, knees, hips, and spine

- The forward takeoff unique to axels (vs. backward takeoffs for other quads) makes them inherently harder and explains why quad axels are more difficult than quad flips or lutz

Related Articles

- Curling at the Winter Olympics: Complete Guide & History [2026]

- Walmart Presidents' Day WHOOP Band Deal: Best Fitness Tracker Bargain [2025]

- Watch Ski Jumping Winter Olympics 2026 Free Live Streams [2025]

- Watch Alpine Skiing Winter Olympics 2026 Free Streams [2025]

- Freestyle Skiing Winter Olympics 2026: Free Live Streams & TV Channels [2026]

- How to Watch Winter Olympics 2026 Opening Ceremony: FREE Streams [2025]

![Quadruple Axel Physics: How Ilia Malinin Defies Gravity [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/quadruple-axel-physics-how-ilia-malinin-defies-gravity-2025/image-1-1770757902878.jpg)