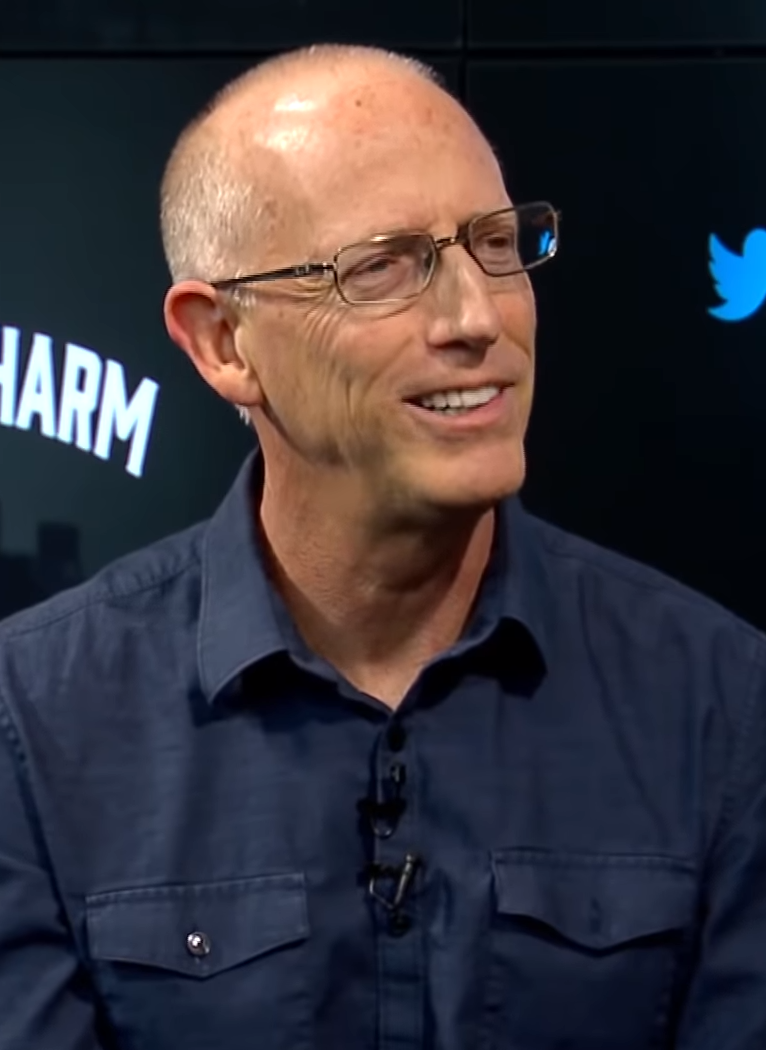

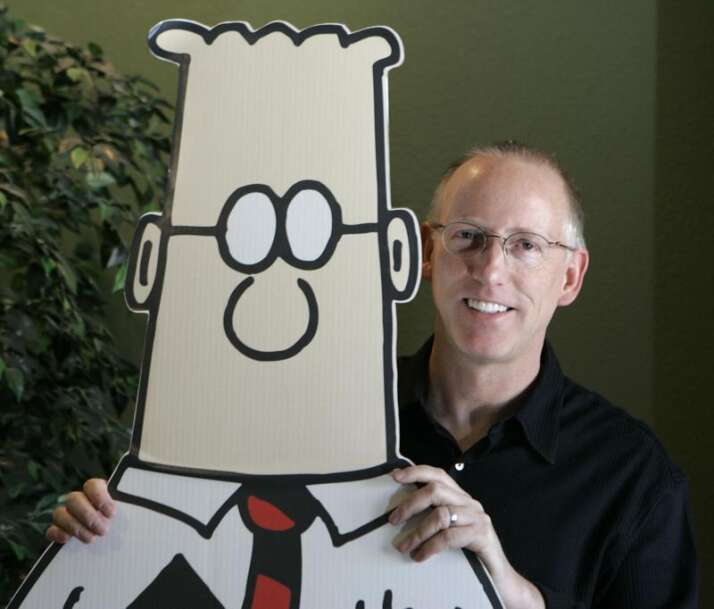

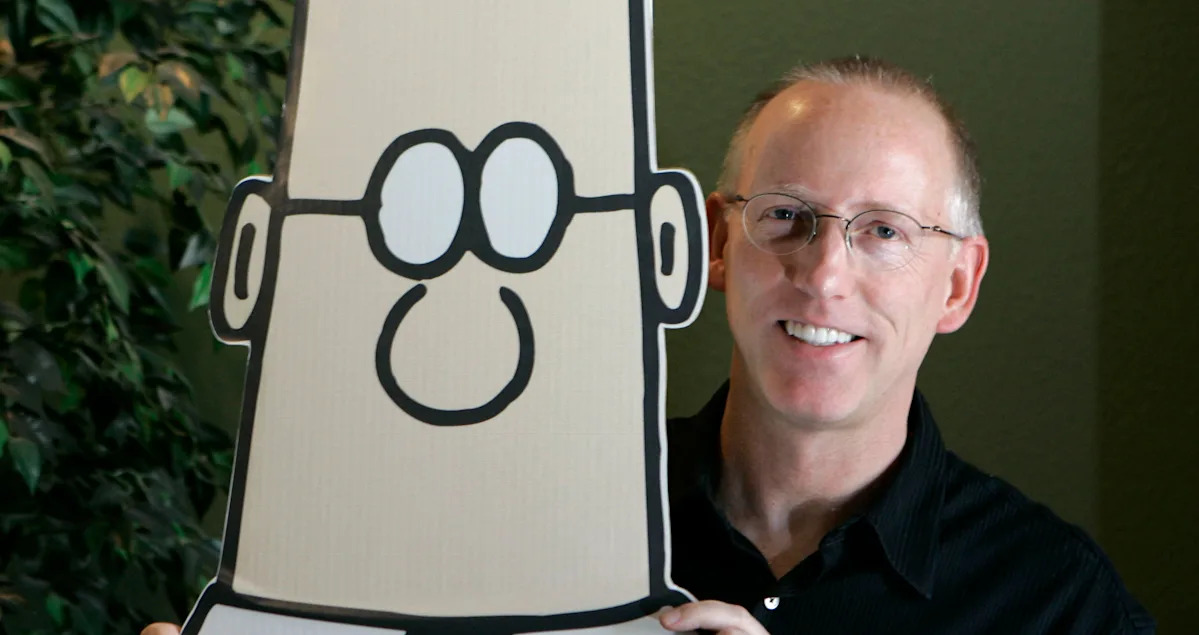

Scott Adams, Dilbert Creator, Dead at 68: A Legacy of Satire, Success, and Controversy

Scott Adams, the visionary cartoonist behind one of the most widely syndicated comic strips in history, has died at age 68 from prostate cancer. His passing marks the end of an era for workplace satire and draws a complicated conclusion to a career that spanned decades of cultural influence, financial success, and ultimately, personal controversy. According to The New York Times, Adams' death was confirmed by his ex-wife.

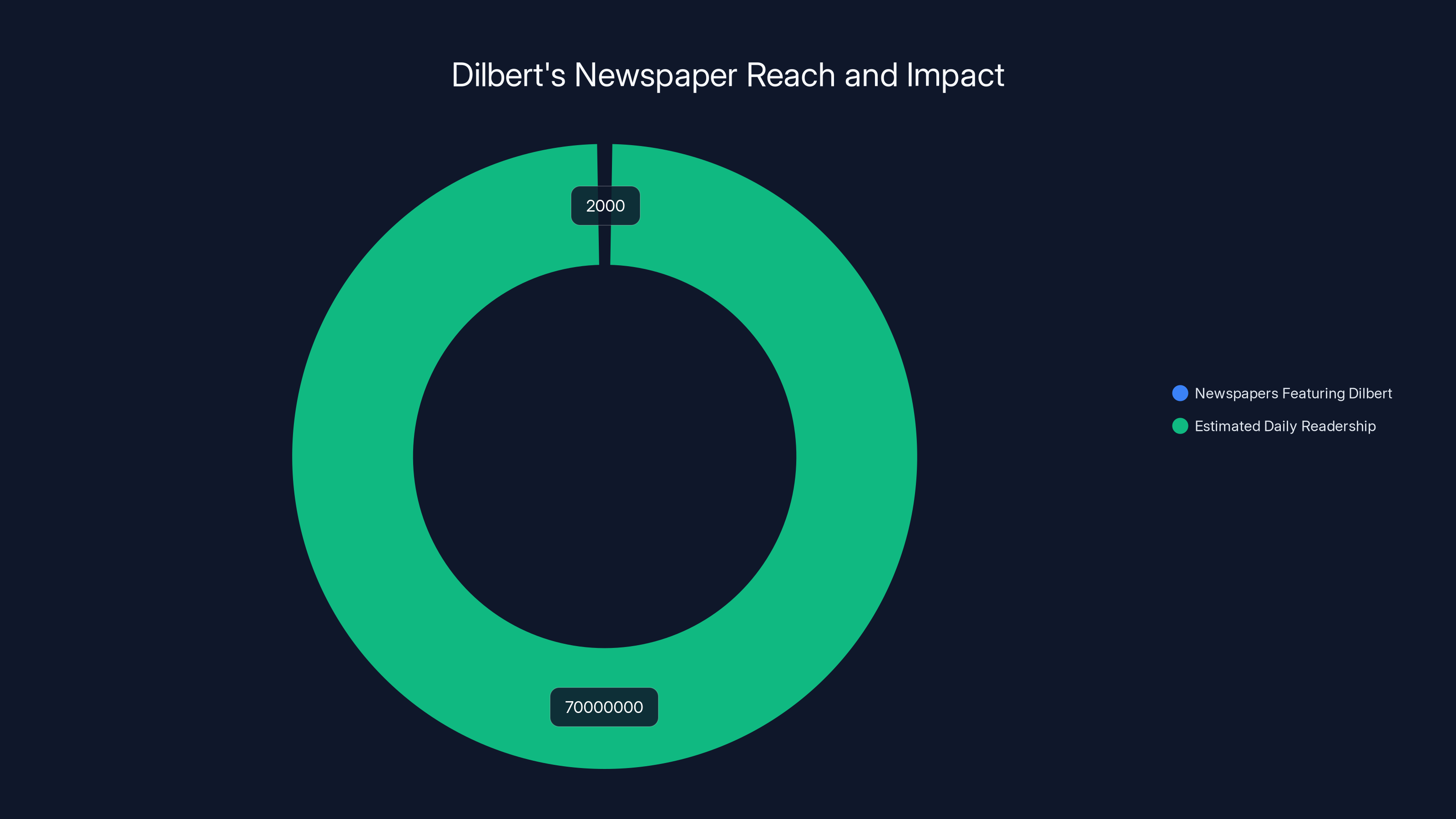

Adams created Dilbert in 1989, and by the peak of its popularity, the strip appeared in roughly 2,000 daily newspapers worldwide. For millions of readers, Dilbert wasn't just entertainment—it was a mirror held up to the absurdity of corporate life, IT departments, and management culture. The comic's protagonist, an engineer surrounded by incompetence, became an icon for anyone who'd ever felt frustrated by pointless meetings, clueless bosses, and bureaucratic nonsense.

But Adams' later life tells a different story. Over the past two decades, his public persona shifted dramatically. What began as clever workplace satire gradually transformed into increasingly vocal political commentary, controversial statements about race and identity, and a rightward ideological turn that culminated in strong support for Donald Trump. This evolution cost him dearly. By 2023, Dilbert had been dropped from most major newspapers. His attempted relaunch as a subscription-based "Dilbert Reborn" struggled to gain traction. And yet Adams pressed forward, building an online community called "Real Coffee with Scott Adams," where he continued hosting streams and engaging with followers right up until his final days, despite declining health.

Adams' death at 68 raises important questions about legacy, redemption, and how public figures navigate cultural shifts. Was he a victim of cancel culture, as he portrayed himself? Or did his own words and actions distance him from the mainstream audience that had once adored his work? The answer, as with most complicated lives, likely involves truth from multiple perspectives.

This article examines Scott Adams' extraordinary career, his cultural impact, the controversies that reshaped his public image, and what his life and death might mean for the future of satire, comic strips, and workplace culture.

TL; DR

- Peak Influence: Dilbert appeared in approximately 2,000 newspapers at its height, making it one of the most widely syndicated comic strips ever created.

- Cultural Impact: The strip fundamentally changed how people talked about and understood workplace absurdity, corporate management, and IT culture.

- Controversial Turn: Adams' statements about race and identity starting in 2022 led to the cancellation of Dilbert from over 75 newspapers within months.

- Final Chapter: Adams attempted to rebuild through subscription-based "Dilbert Reborn" and online streaming community "Real Coffee with Scott Adams."

- Legacy Question: His death reignites debate about artistic legacy, personal conduct, and whether satirists must practice what they preach.

At its peak, Dilbert appeared in about 2,000 newspapers with an estimated daily readership of 70 million, highlighting its significant cultural impact. Estimated data.

The Dilbert Phenomenon: How One Comic Strip Captured Corporate Absurdity

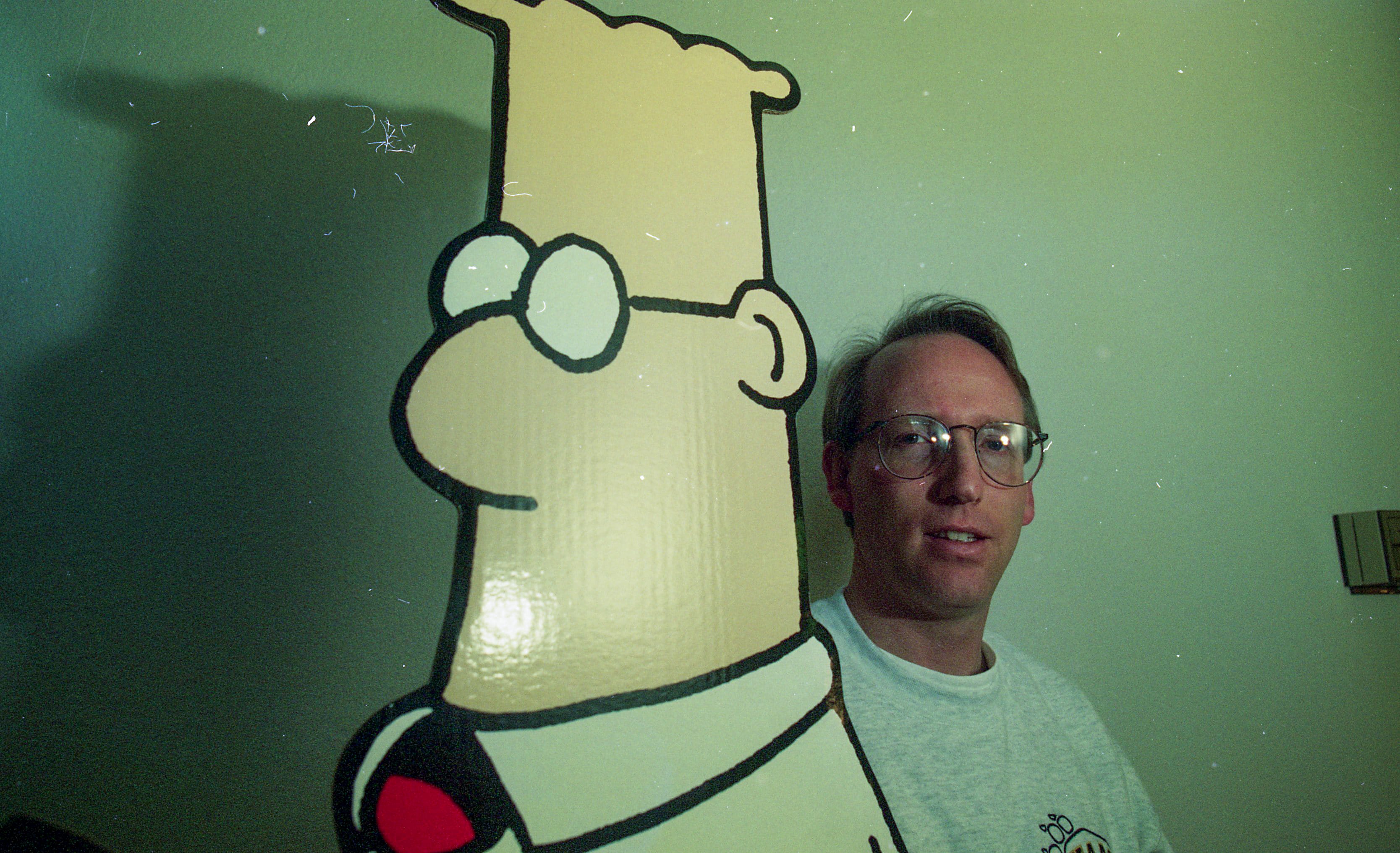

When Scott Adams first introduced Dilbert in 1989, he wasn't working in a basement or pursuing a pipe dream. He was already a salaried employee at Pacific Bell, working in the very corporate environment his comic would eventually skewer. This wasn't theoretical satire—it was lived experience translated into four-panel observations about the human condition in cubicles.

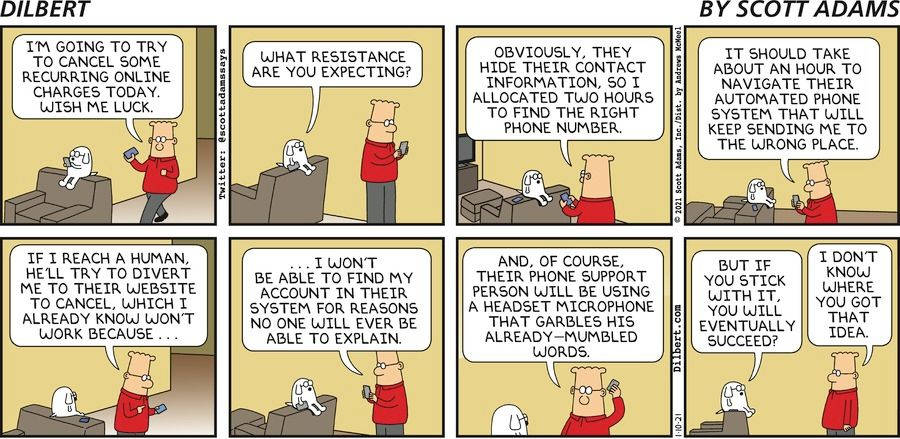

The early strips established the core cast: Dilbert, an intelligent engineer with minimal social skills; the Pointy-Haired Boss, a caricature of managerial incompetence; and Dogbert, a cynical talking dog who served as both comic relief and philosophical foil. But the real genius of Dilbert wasn't the characters—it was the observations. Adams wrote about things that happened in actual workplaces. The useless meetings. The metrics that measure nothing. The way management rewarded loyalty while eliminating jobs. The contradiction of asking employees to "think outside the box" while enforcing rigid conformity.

By the mid-1990s, Dilbert had become something more than entertainment. It became a shared language for discussing workplace frustration. Business leaders, engineers, and middle managers all recognized themselves in the strip. Dilbert coffee mugs appeared in cubicles across America. Companies actually started buying Dilbert books and distributing them to employees as a way to acknowledge (and often excuse) workplace dysfunction.

What made Dilbert different from other workplace comedies was its specificity. The humor didn't rely on slapstick or physical comedy. Instead, it used precise observation and subtle misdirection. A classic Dilbert strip might involve the Pointy-Haired Boss announcing a new initiative that sounds important but is actually nonsensical—and everyone nodding along as if it makes sense. The comedy came from recognition, from the reader thinking, "Oh God, I've been in exactly this meeting."

Adams' background gave him credibility that pure comedy writers might lack. He understood corporate metrics systems because he'd lived them. He knew the frustration of explaining technical concepts to non-technical managers because he'd done it countless times. This authenticity resonated with millions of readers who felt similarly invisible and undervalued in their own organizations.

By 2000, Dilbert was appearing in approximately 2,000 newspapers daily. That's not a niche audience—that's mainstream cultural penetration comparable to major news columnists. Adams had book deals, licensing agreements, merchandise sales, and speaking engagements where corporations literally paid him to lecture them about their own dysfunction. It was a remarkable achievement for a comic strip that could have easily been dismissed as too technical or too insider for mass appeal.

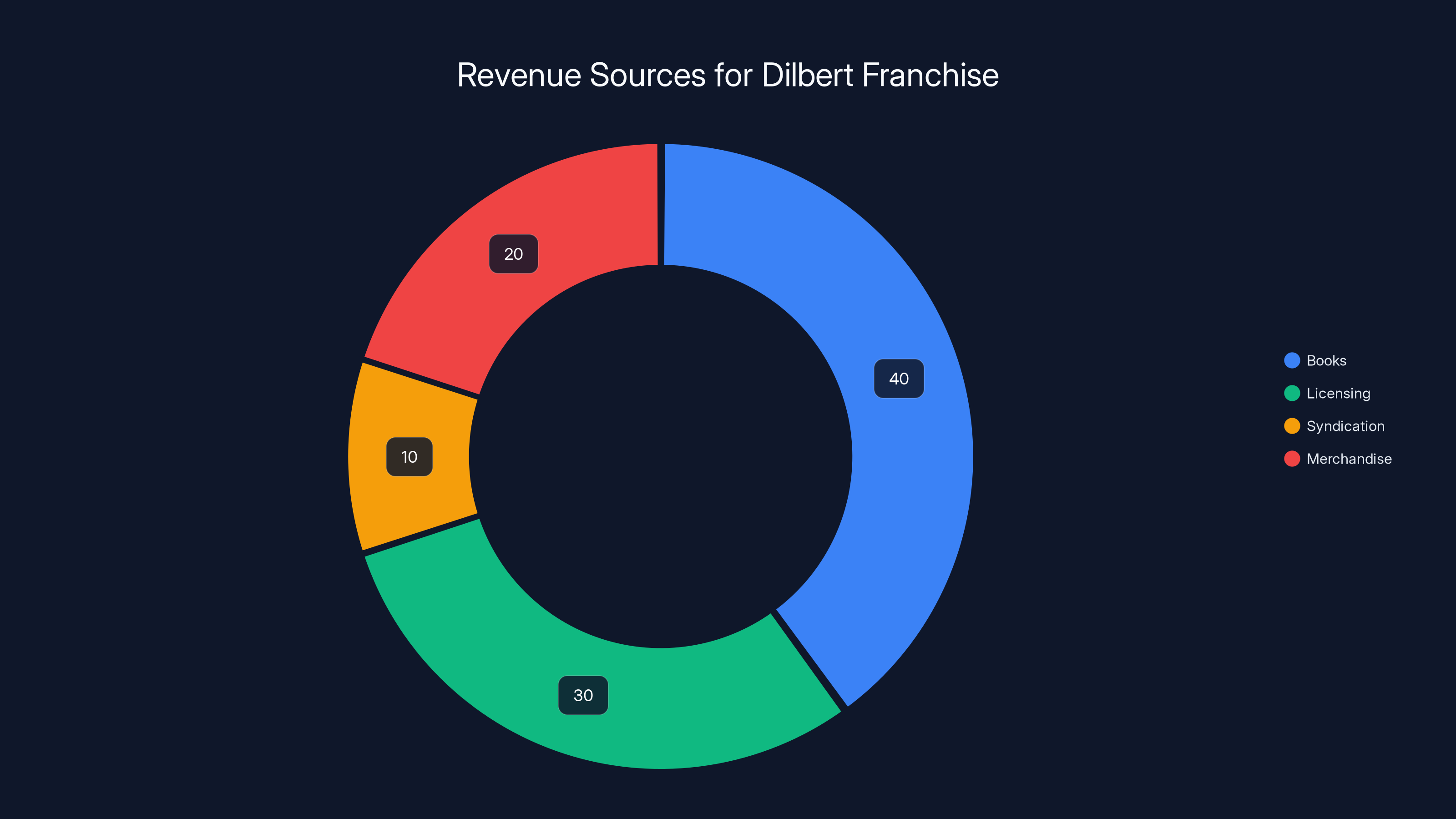

The strip generated an estimated $100 million in annual revenue at its peak through various licensing deals and merchandise. Adams went from being a salaried engineer to a cartoonist whose work was read by tens of millions of people globally. Few creators achieve that level of commercial success while maintaining critical respect and cultural relevance.

The Business of Satire: How Adams Built a Billion-Dollar Franchise

Scott Adams wasn't just a talented cartoonist—he was a shrewd businessman who understood the economics of intellectual property long before it became a dominant concern in the media industry. His approach to monetizing Dilbert went far beyond syndication fees, which provided a baseline income but were never meant to be the primary revenue stream.

The real money in Dilbert came from books. Adams wrote dozens of Dilbert collections, each one carefully merchandised to specific audiences. There were books focused on management failures, books about technology, books about workplace relationships, books about life as an engineer. Each collection allowed Adams to repackage previously published strips in new configurations while adding new commentary and insights. These books sold millions of copies worldwide and generated substantial royalties.

More importantly, Adams licensed Dilbert to countless companies. Office supply companies put Dilbert on their packaging. Technology firms used Dilbert references in their marketing. Corporate training programs incorporated Dilbert strips into their materials. This licensing revenue became increasingly significant as merchandise, board games, and other tie-ins proliferated.

Adams also pioneered using Dilbert as a platform for his own books on business, management, and later, politics. "The Dilbert Principle," published in 1996, became a bestseller that explained corporate dysfunction through the lens of his comic strip. This book legitimized Adams as a business commentator, not just a humorist. It led to speaking engagements, consulting opportunities, and an expanded platform to share his views on management, economics, and human behavior.

The formula worked remarkably well. Adams would observe a workplace phenomenon, turn it into a comic strip, compile strips into a book with additional commentary, and then leverage the book's success to build his personal brand as a management expert. By the early 2000s, he was generating income from multiple revenue streams simultaneously: syndication fees, book royalties, licensing agreements, speaking engagements, and consulting work.

This business acumen allowed Adams to maintain creative control in ways many cartoonists couldn't. He owned Dilbert outright, which meant he wasn't dependent on any single newspaper or publisher. If one newspaper dropped the strip, dozens of others still carried it, and the licensing deals provided more revenue than syndication alone. This independence would later prove crucial when his public statements became controversial.

By 2010, Adams had built something extraordinary: a personal brand and intellectual property portfolio that generated substantial income from multiple sources while maintaining creative autonomy. Few cartoonists achieve this level of financial success and independence. Most remain dependent on their syndicators or publishers. Adams had transcended that dependency.

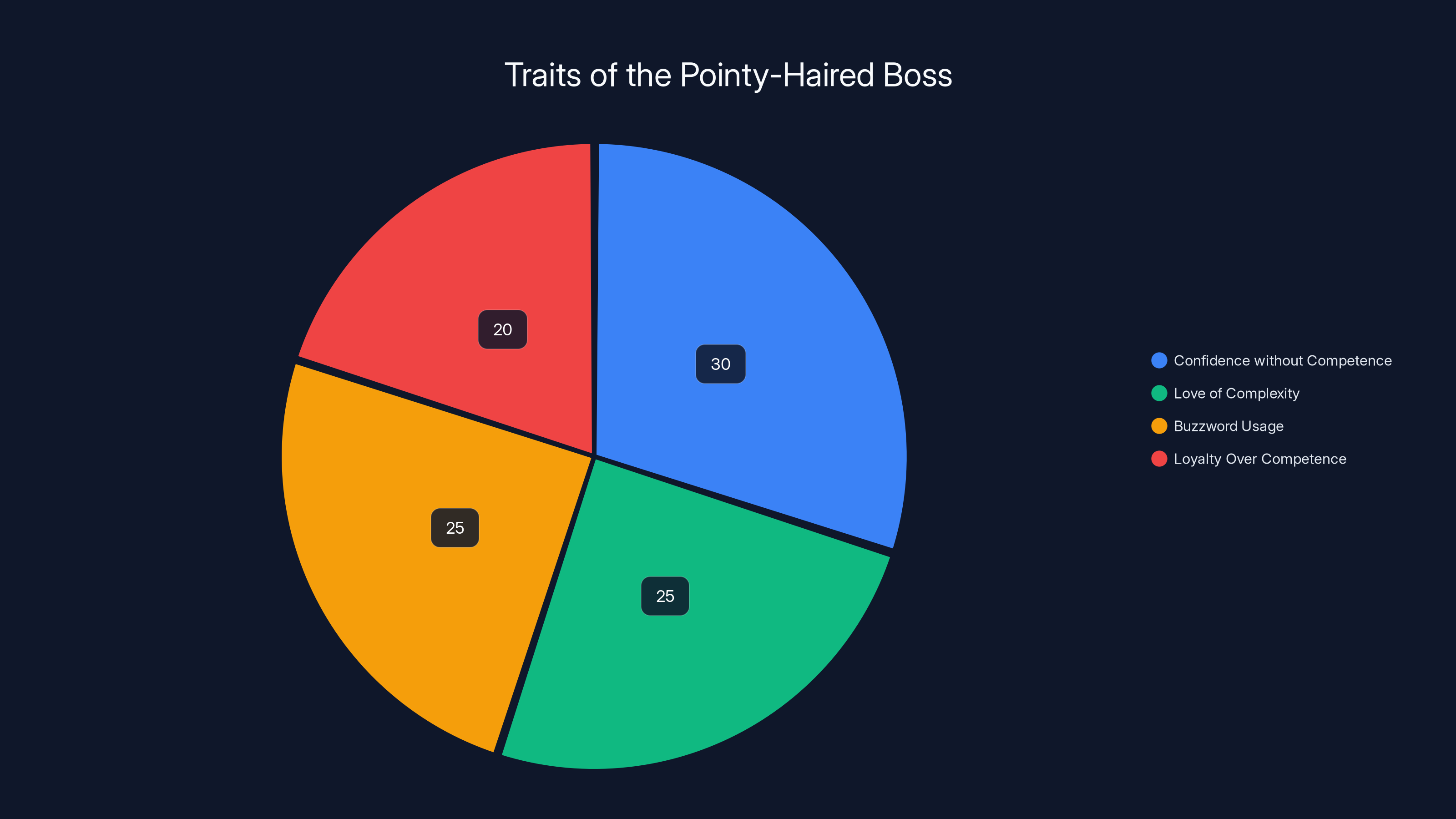

The Pointy-Haired Boss character resonates due to common traits like confidence without competence and buzzword usage. Estimated data based on typical corporate experiences.

The Pointy-Haired Boss: Why Dilbert Resonated With Millions

At the heart of Dilbert's success was a character that many workers found more realistic than the protagonist himself: the Pointy-Haired Boss. This caricature represented everything that frustrated workers in corporate environments. The Pointy-Haired Boss was incompetent but confident. He made decisions based on what sounded good rather than what made sense. He rewarded loyalty over competence. He created nonsensical metrics that measured activity rather than outcomes. He talked about "synergy" and "optimization" without understanding what those words actually meant.

What made this character genius was his universality. Almost everyone who's worked in a corporate environment has encountered a version of the Pointy-Haired Boss. Not necessarily someone identical, but someone who shares the fundamental traits: confidence without competence, love of complexity over simplicity, tendency toward buzzwords over clarity.

Adams understood something crucial about management dysfunction: it's rarely malicious. The Pointy-Haired Boss isn't trying to make his employees miserable. He's trying to advance his own career, impress his superiors, and appear decisive. The fact that his decisions make the workplace worse is almost incidental to his actual motivations. This psychological insight gave Dilbert depth that simple office comedy lacked.

The strip also tapped into a genuine historical moment in American business culture. The 1990s and 2000s were characterized by massive organizational restructuring, the rapid growth of the internet industry, increasing globalization, and the rise of metrics-driven management. Companies downsized while demanding more productivity from remaining workers. They invested in consultants and expensive software while ignoring what actual employees were telling them about problems. They created middle management positions whose main purpose seemed to be justifying their own existence.

Dilbert didn't invent these problems, but it named them in a way that made them visible. Workers could share a Dilbert comic with their colleagues and communicate complex frustrations without direct confrontation. It was a safety valve for workplace dissatisfaction.

The Pointy-Haired Boss also represented something deeper: the anxiety that intelligence and competence weren't actually rewarded in corporate hierarchies. Dilbert and his engineer friends were consistently smarter than their management, yet management made decisions that affected their lives. This powerlessness—being ruled by people you know are less competent than yourself—was the actual source of frustration that Dilbert captured.

This dynamic became even more relevant as technology companies grew in the 1990s and 2000s. Technical workers found themselves reporting to managers who didn't understand technology. Software engineers watched non-technical executives make decisions that would affect their projects. Database administrators saw their expertise ignored in favor of fashionable but inappropriate solutions. Dilbert gave voice to this specific form of workplace frustration.

Adams also understood that the Pointy-Haired Boss represented a system, not just an individual. The character was incompetent partly because the system incentivized incompetence. Advancing in corporate hierarchies often required political skills, not technical competence. Speaking confidently about vague concepts could advance your career more effectively than admitting uncertainty or limitations. Dilbert satirized the system as much as individual bad actors.

Peak Circulation and Cultural Dominance: The Height of Dilbert's Influence

By the early 2000s, Scott Adams had achieved something remarkable: his comic strip was read by an estimated 60 to 80 million people daily across approximately 2,000 newspapers. To put this in perspective, that's nearly a quarter of the United States population reading about Dilbert in their local newspapers every single day. No other satirist, comedian, or social commentator had reached such a vast audience without access to broadcast television or radio.

The strip's cultural dominance manifested in countless ways. Business schools assigned Dilbert comics to illustrate management failures. HR departments tried to distance themselves from the Pointy-Haired Boss stereotype. Engineers recognized themselves in Dilbert's social awkwardness and technical competence. Corporate consultants found their own positions subtly mocked in strip after strip.

Adams' books were bestsellers. "The Dilbert Principle" spent weeks on the bestseller lists and was translated into multiple languages. Academic researchers studying corporate culture cited Dilbert as a cultural artifact worth analyzing. Mainstream media outlets interviewed Adams about his observations on management and workplace culture.

The strip also spawned a television animated series that aired from 1999 to 2000 and later as movies and specials. While the TV show never matched the strip's cultural penetration, it extended Dilbert's reach into visual media and introduced the characters to audiences who didn't read newspapers. The show maintained the satirical edge of the comic while adding visual comedy and voice acting that brought the characters to life.

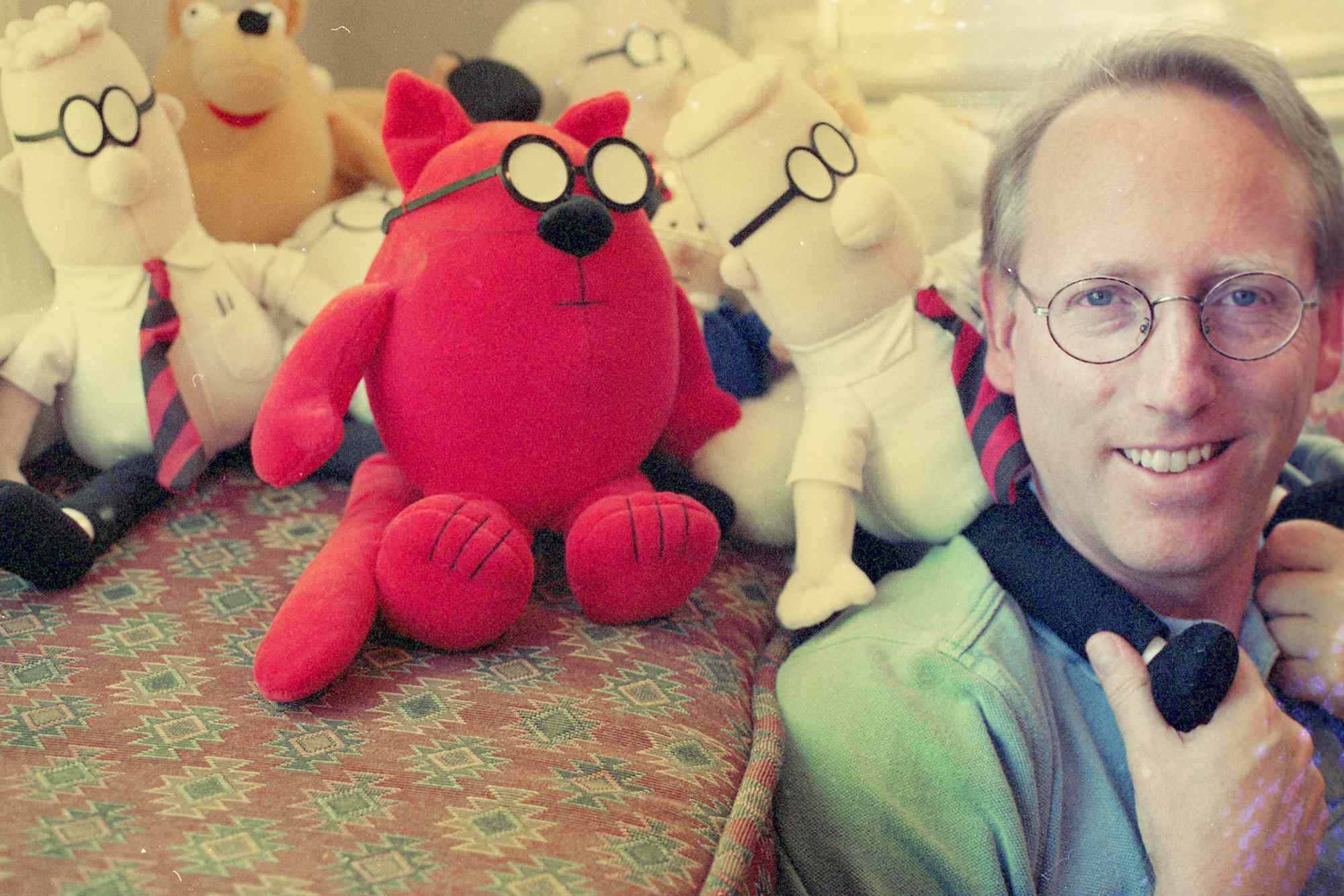

Licensing deals proliferated during this period. Dilbert appeared on office supplies, coffee mugs, t-shirts, calendars, greeting cards, and countless other products. Companies bought Dilbert merchandise in bulk to distribute to employees or sell in their gift shops. The character became visually recognizable to people who might never read the actual strip.

Dilbert conventions and fan gatherings emerged. There were online communities dedicated to discussing and sharing Dilbert comics. The strip inspired spin-offs and fan creations. Some workplaces developed their own "Dilbert" characters based on their own management styles. The strip had become so culturally embedded that people referenced it as shorthand for workplace dysfunction: "That's so Dilbert," someone might say about a particularly pointless meeting.

Advertisers and marketers tried to capitalize on Dilbert's popularity. Some attempts were successful (office supply companies, business book publishers). Others rang false (Dilbert had the cultural credibility to mock corporate messaging, so using him to sell actual corporate products often backfired). But the sheer fact that so many companies wanted to associate with Dilbert demonstrates how culturally significant the strip had become.

Adams had become wealthy beyond what most cartoonists could expect. Estimates suggest he was earning millions annually from various Dilbert-related revenue streams. He'd transcended the traditional cartoonist's career path—syndication, licensing, occasional TV deals—to become a genuine brand and media empire. He was as much a business writer and management consultant as he was a cartoonist.

The Shift From Satire to Politics: When Adams Became The Story

Somewhere around the late 2000s and early 2010s, Scott Adams began using his platform differently. The early Dilbert strips focused almost exclusively on workplace dysfunction and management failures. But as Adams aged and became wealthier, his interests diversified. He started writing books about technology, economics, and the nature of persuasion. He became increasingly vocal about political issues. And gradually, his personal politics—conservative, libertarian-leaning, eventually strongly pro-Trump—became increasingly visible in both his public statements and his comic work.

This shift wasn't necessarily surprising. Many cartoonists and artists have used their platforms to express political views. But for Adams, the transition created tension. Dilbert's strength came from its universality—workers across the political spectrum could enjoy the comic because it focused on shared workplace frustrations rather than partisan divisions. As Adams introduced more explicitly political content, he risked alienating part of his audience.

Initially, the political commentary was relatively subtle. Adams would make jokes about government inefficiency or bureaucratic waste—observations that many readers could agree with regardless of their politics. But as the 2010s progressed, Adams became more explicitly conservative in his public statements. He criticized certain political movements, expressed skepticism about progressive causes, and eventually became an outspoken supporter of Donald Trump.

Adams also became active on social media platforms like Twitter, where he engaged in political debates and made controversial statements. Social media is fundamentally different from traditional comic syndication—it's more immediate, more reactive, and leaves less room for nuance or context. What might work as a satirical jab in a comic strip can seem aggressive or offensive as a direct social media post.

The shift from cartoonist to political commentator also changed the nature of Adams' platform. Newspapers carried Dilbert because it was funny and relatively non-controversial. But they had editorial standards and advertising considerations. Political statements that might be acceptable in his personal Twitter account or podcast could be problematic for newspapers to associate with, especially if those statements were perceived as inflammatory.

This dynamic set the stage for the controversies that would eventually lead to Dilbert's cancellation from major newspapers. Adams' political statements hadn't changed the nature of his comic strip itself—Dilbert still featured the same characters and workplace satire that had always been the strip's core. But the public perception of Adams himself had shifted, and in modern media, the creator's personal brand is inseparable from the work.

Books and licensing are the primary revenue sources for the Dilbert franchise, with books contributing an estimated 40% and licensing 30% of total revenue. Estimated data.

The 2022 Controversy: When Dilbert Became Politically Polarized

In 2022, Scott Adams introduced Dilbert's first Black character. The character's introduction could have been an unremarkable diversification of the strip's cast. Instead, Adams used the character as a vehicle to mock what he perceived as excessive "woke" culture and progressive identity politics. The Black character was drawn with the intention of making a statement about identity and representation, but Adams' approach came across to many readers and newspapers as mockingly dismissive of diversity itself.

Over 75 newspapers dropped Dilbert in response to this storyline. For a comic strip that had spent decades building syndication, dropping from 75 papers represented a significant loss of reach and revenue. The incident demonstrated that there were real limits to how far advertisers, newspapers, and readers would tolerate Adams' political commentary, even when it was technically still embedded in the comic strip format.

Adams responded to the controversy by claiming that critics had misunderstood his intentions. He argued that he wasn't mocking the Black character or the concept of diversity, but rather mocking what he saw as absurd approaches to identity and representation. But this explanation didn't satisfy the newspapers that had dropped the strip or the readers who had found the content offensive.

The incident proved instructive. It demonstrated that in the modern media environment, a creator's stated intentions matter far less than how the audience interprets the work. Adams had built his career on understanding what resonates with audiences, but he seemed less adept at understanding how his political statements would be received.

The 2022 controversy also highlighted a generational shift in media consumption. Younger readers and younger newspaper editors were increasingly unwilling to separate the creator from the work. If they disagreed with Adams' politics or found his statements offensive, they weren't interested in reading Dilbert, regardless of the comic's historical cultural value. This was fundamentally different from earlier decades when a comic's quality could overcome the creator's personal controversies.

The "It's Okay to Be White" Incident: The Final Fracture

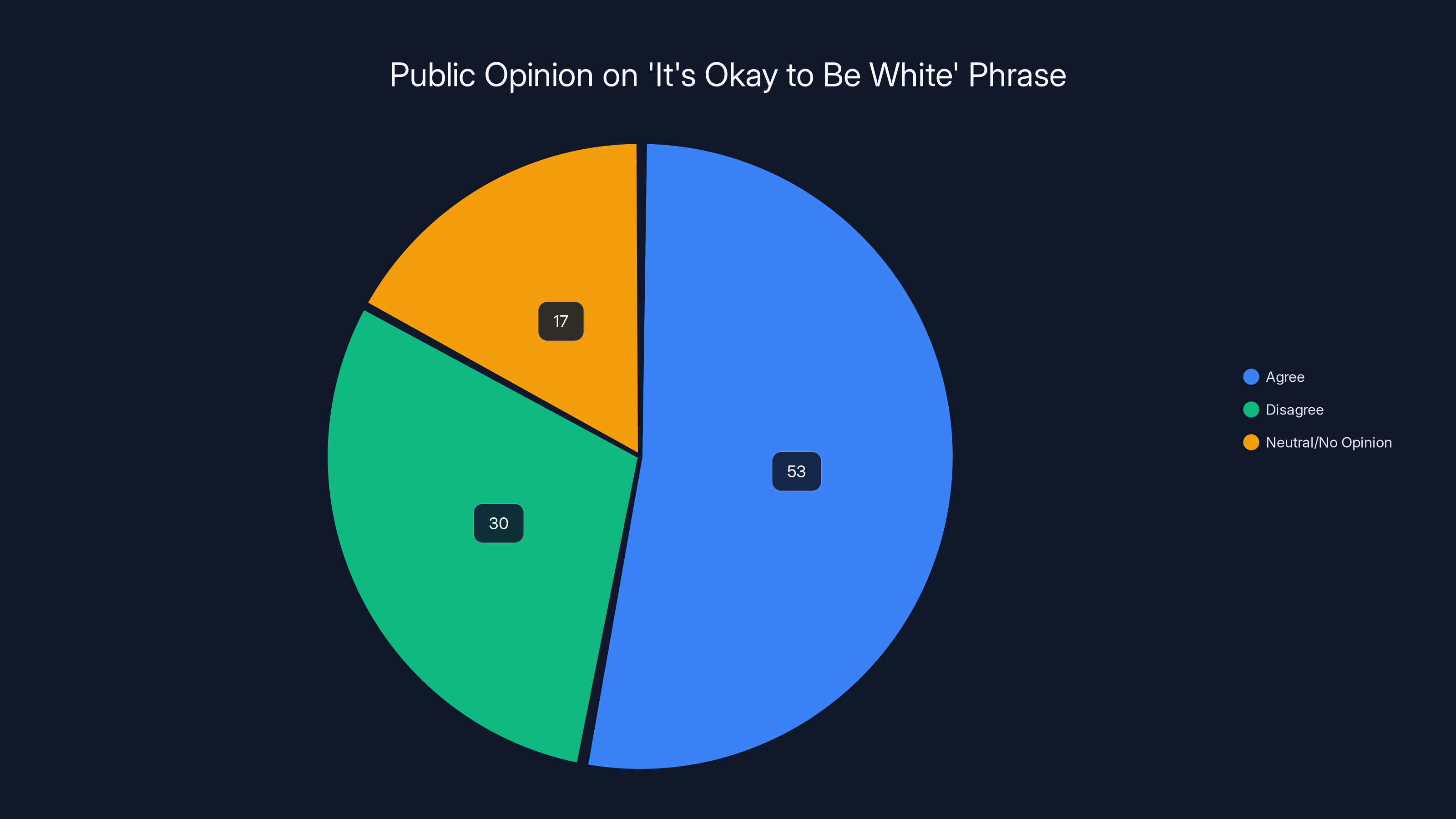

Less than a year after the 2022 controversy, Scott Adams made public comments that would prove far more damaging to his career than the Black character incident. In 2023, Adams responded to a poll that found that only 53 percent of Black Americans agreed with the phrase "It's okay to be white." This phrase has origins in alt-right online spaces and is often used as a deliberately provocative statement intended to expose what some perceive as anti-white sentiment.

On his podcast, Adams discussed the polling data and made several inflammatory statements. According to reporting at the time, Adams said that Black Americans who didn't agree with the phrase "It's okay to be white" constituted a "hate group." He then said: "I would say, based on the current way things are going, the best advice I would give to white people is to get the hell away from Black people."

These statements went far beyond satire or political commentary. They were presented not as jokes or comic exaggeration, but as direct advice and political analysis. The statements drew immediate condemnation from civil rights organizations, journalists, and cultural commentators. Most importantly for Adams' career, they prompted a major wave of newspaper cancellations.

Adams later clarified his remarks, claiming he was speaking "hyperbolically" and that he wasn't advocating for actual racial separation. He argued that he was warning white people to avoid social groups that viewed them as inherent enemies. But this clarification came too late and lacked the force of the original statements. Major newspapers that had carried Dilbert for decades made the decision to drop the strip.

The fallout was severe and immediate. Unlike the 2022 incident where over 75 newspapers dropped the strip, the 2023 controversy led to Dilbert being dropped from most major metropolitan newspapers and syndicates. The combined circulation loss from 2022 and 2023 essentially reduced Dilbert from approximately 2,000 newspapers to a handful of remaining outlets.

For Adams, this represented an extraordinary reversal of fortune. He had spent thirty-plus years building one of the most successful comic strips in history. At its height, it was read by tens of millions of people daily. Within the span of less than two years, the strip had been canceled from nearly every significant newspaper in the country.

Adams' response to this second wave of cancellations was to accuse critics of attempting to silence him and to double down on his statements. He created a website explaining his perspective and defending his podcast comments. He argued that he was being unfairly portrayed and that critics were twisting his words to create outrage. But none of these arguments prevented the newspaper cancellations or restored the syndication deals that had been terminated.

Dilbert Reborn: The Failed Pivot to Direct-to-Consumer

With most newspapers having dropped Dilbert, Scott Adams attempted to salvage his comic strip through a subscription model. He launched "Dilbert Reborn," positioning it as a version of the strip "too spicy for the general public." The implication was that newspapers were unwilling to carry Dilbert because of cancel culture and oversensitivity, not because his statements had been genuinely offensive.

The subscription model offered Adams a potential escape from newspaper syndication dependency. If he could build a sufficiently large subscription base, he wouldn't need newspapers at all. Readers could access new Dilbert comics directly through his website for a subscription fee, creating a more direct relationship between creator and audience.

However, the Dilbert Reborn launch struggled to gain traction. While Adams had a dedicated core of supporters, converting them into paying subscribers proved difficult. The subscription model removed the frictionless distribution that traditional newspaper syndication provided. Readers who had enjoyed Dilbert in their morning paper found that getting the same comic now required a separate subscription, which created friction and friction generally reduces conversion rates.

The subscription strategy also lacked the cultural visibility that newspapers provided. A comic in 2,000 newspapers is encountered by people who never specifically sought it out. A subscription-only comic is only discovered by people actively looking for it or already familiar with Adams' work. This creates a much smaller potential audience.

Moreover, the positioning of Dilbert Reborn as "too spicy for the general public" actually limited its audience further. Adams was explicitly excluding people who wanted mainstream, inoffensive humor. He was signaling that his content was now deliberately provocative, which appealed to his core supporters but alienated potential new readers and casual fans.

Adams' attempt to position Dilbert Reborn as victim of cancel culture also had unintended consequences. It reinforced the perception that his recent statements had been genuine expressions of his beliefs rather than satire or misunderstandings. If he were truly the victim of misinterpretation, he might have tried to clarify or distance himself from the controversial statements. Instead, he doubled down and created a space explicitly designed to continue provocative commentary.

By most accounts, Dilbert Reborn never achieved significant subscription numbers. Adams' estimates of his subscriber base varied and were never independently verified. But given that the subscription model didn't restore his publishing presence or relevance, it's reasonable to conclude that the strategy failed to achieve its objectives.

A 2023 poll found that 53% of Black Americans agreed with the phrase 'It's okay to be white', while 30% disagreed and 17% were neutral or had no opinion. Estimated data based on context.

The Pivot to Books and Personal Branding: What Came After Comics

With Dilbert's newspaper syndication essentially eliminated, Adams focused his energy on other projects and revenue streams. He continued writing books, particularly business and political books that allowed him to articulate his perspectives at length. These books targeted audiences specifically interested in his ideas, rather than the general newspaper-reading public that had once embraced Dilbert.

Adams wrote books exploring topics like persuasion, decision-making, systems thinking, and political analysis. Some of these books were best-sellers, particularly among conservative and libertarian audiences who appreciated his contrarian perspective and skepticism toward progressive politics. The book business provided steady income and maintained his platform as a thought leader, even as his comic strip faded from popular consciousness.

He also maintained a significant social media presence, particularly on Twitter/X, where he continued to express political views and engage in debates with critics. Social media allowed him to maintain direct communication with supporters without relying on traditional media gatekeepers. This was simultaneously a strength and a weakness: it kept him visible to his core audience, but it also meant he was constantly available for criticism and confrontation.

Adams' podcast, "Real Coffee with Scott Adams," became his primary platform for regular engagement with his audience. The podcast format allowed him to discuss topics in depth, interview guests, and maintain a direct relationship with his supporters. Unlike the comic strip, which was distributed through newspapers to passive readers, the podcast required active subscription or listening—a fundamentally different relationship with the audience.

The transition from comic strip to podcaster and book author represented a significant shift in Adams' relationship with his audience and with media itself. The comic strip's strength was its universality and its regular, casual presence in readers' daily lives. A comic takes two minutes to read, appears whether you actively seek it out or not, and invites no particular political affiliation.

Books and podcasts, by contrast, require active engagement and commitment. They appeal to audiences already interested in the creator's specific perspective. This tends to create more politically and ideologically homogeneous audiences. Someone who seeks out a Scott Adams book or podcast is already predisposed to be interested in his ideas.

This audience shift fundamentally changed Adams' cultural role. He went from being a universal satirist whose work everyone encountered to being a political commentator whose audience self-selects based on ideological compatibility. This isn't inherently bad, but it represents a dramatic reduction in scope and cultural influence.

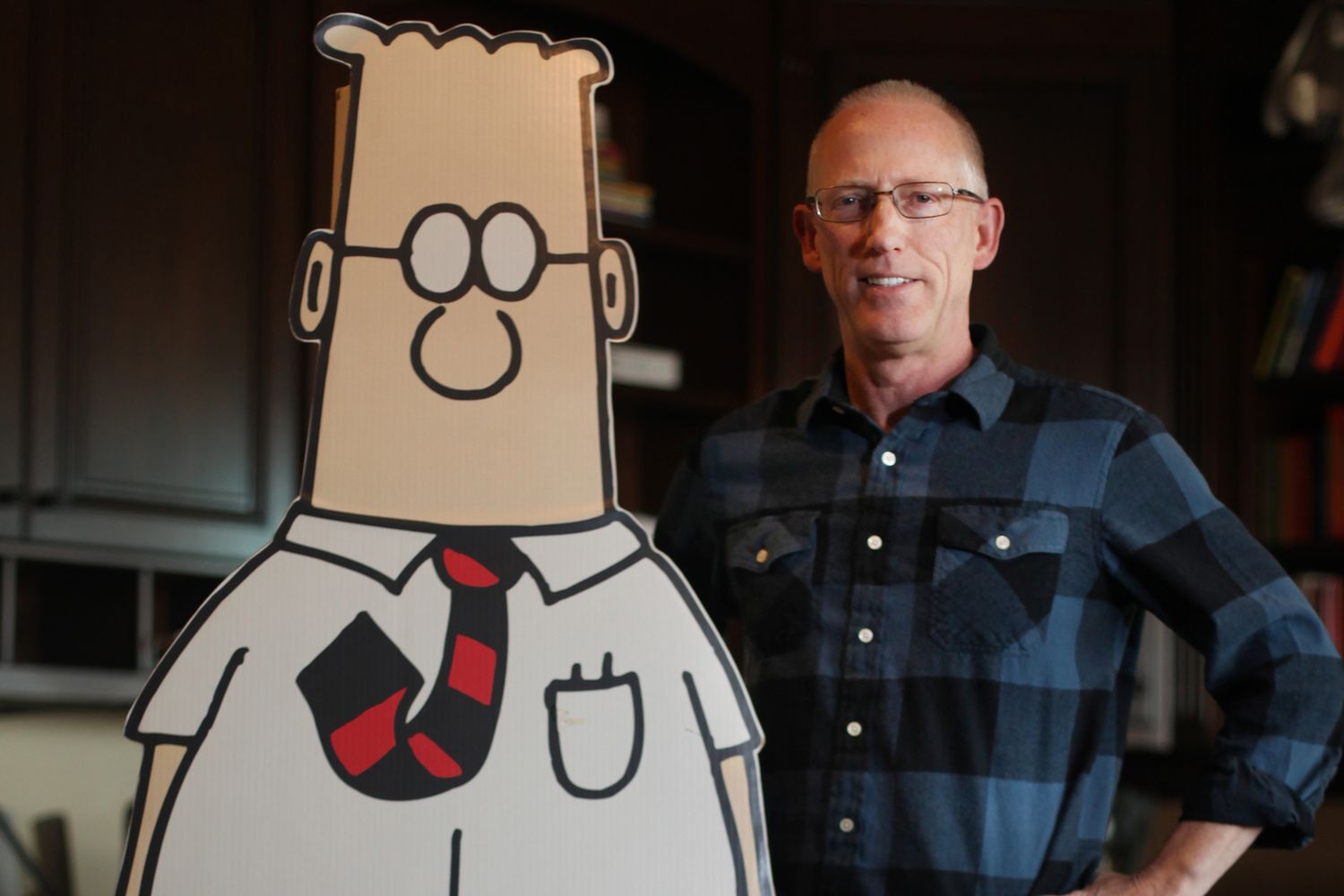

Health Challenges and the Final Years: Continuing Despite Decline

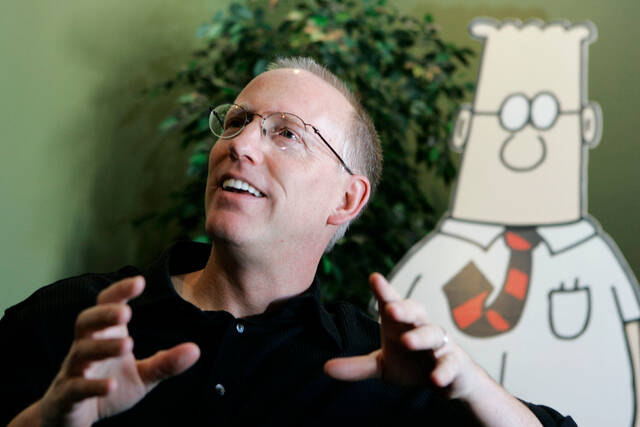

In the final years of his life, Scott Adams dealt with significant health challenges that gradually deteriorated his physical capabilities. He lost feeling in his legs and struggled with mobility issues that would eventually make normal movement difficult. Despite these physical challenges, Adams maintained his online presence and continued hosting Real Coffee streams with remarkable regularity.

What's striking about Adams' final years is his apparent determination to maintain his public presence despite declining health. He appeared on video streams even when visibly unwell. He continued engaging with the audience and discussing current events. He maintained his podcast schedule with few cancellations. This reflects either remarkable dedication to his work and audience or perhaps a recognition that his online community had become central to his life after the newspaper syndication had essentially ended.

Adams' health challenges also put his controversial statements into different context. Some observers wondered whether the increasingly inflammatory rhetoric was connected to health-related stress or cognitive changes. Others suggested that his focus on outrage and controversy was a way to maintain relevance and audience engagement as traditional revenue streams dried up.

Adams continued streaming and appearing online right up until two days before his death from prostate cancer. His final appearance was reported to include jokes about "liberal women" and politics, suggesting that his provocative style remained consistent even as his physical health was obviously failing.

The contrast between Adams' declining health and his continued online activity raises questions about loneliness, purpose, and how digital communities can provide meaning even when traditional career success has been eliminated. The Real Coffee community wasn't a replacement for the newspaper audience Adams once had, but for someone dealing with serious health issues, it may have provided important connection and sense of purpose.

The Final Statement: Adams' Last Words and Spiritual Questions

Adams' final statement, read aloud on his Real Coffee channel by his ex-wife after his death, is notable for what it doesn't emphasize. Rather than celebrating Dilbert or his role as a cartoonist and workplace satirist, Adams focused on his other work, particularly his books. He expressed a desire to have been "useful" and encouraged his followers to do likewise.

The statement also included a surprising spiritual element. Adams, who had not been a practicing Christian during his life, included a statement claiming to "accept Jesus Christ as my lord and savior." He acknowledged this was somewhat strategic, noting the "risk-reward calculation" was favorable: if he was wrong about God, nothing was lost. If he was right, the potential consequences were significant. He added a pragmatic note: any question about his actual belief would be resolved definitively if he woke up in heaven.

This theological pragmatism is actually entirely consistent with Adams' public persona. He'd long positioned himself as someone who thought clearly about complex systems and incentive structures. Approaching religion as a risk-benefit calculation is very much in character for someone who spent years analyzing management failures through systems-thinking frameworks.

The statement provides little window into whether Adams had genuine regret about his controversial statements or whether he was attempting to manage his legacy as he faced mortality. It's conspicuously brief on personal relationships and lacks any acknowledgment of the human cost of the controversies he'd created. There are no apologies, no explicit recognition of harm, no suggestions that he'd changed his mind about his stated views.

Instead, the statement emphasizes usefulness and encourages followers to pursue similar goals. It's a summation that frames his life as productive and well-spent, even as his final years were characterized by the loss of the institution he'd spent decades building and by escalating public controversy.

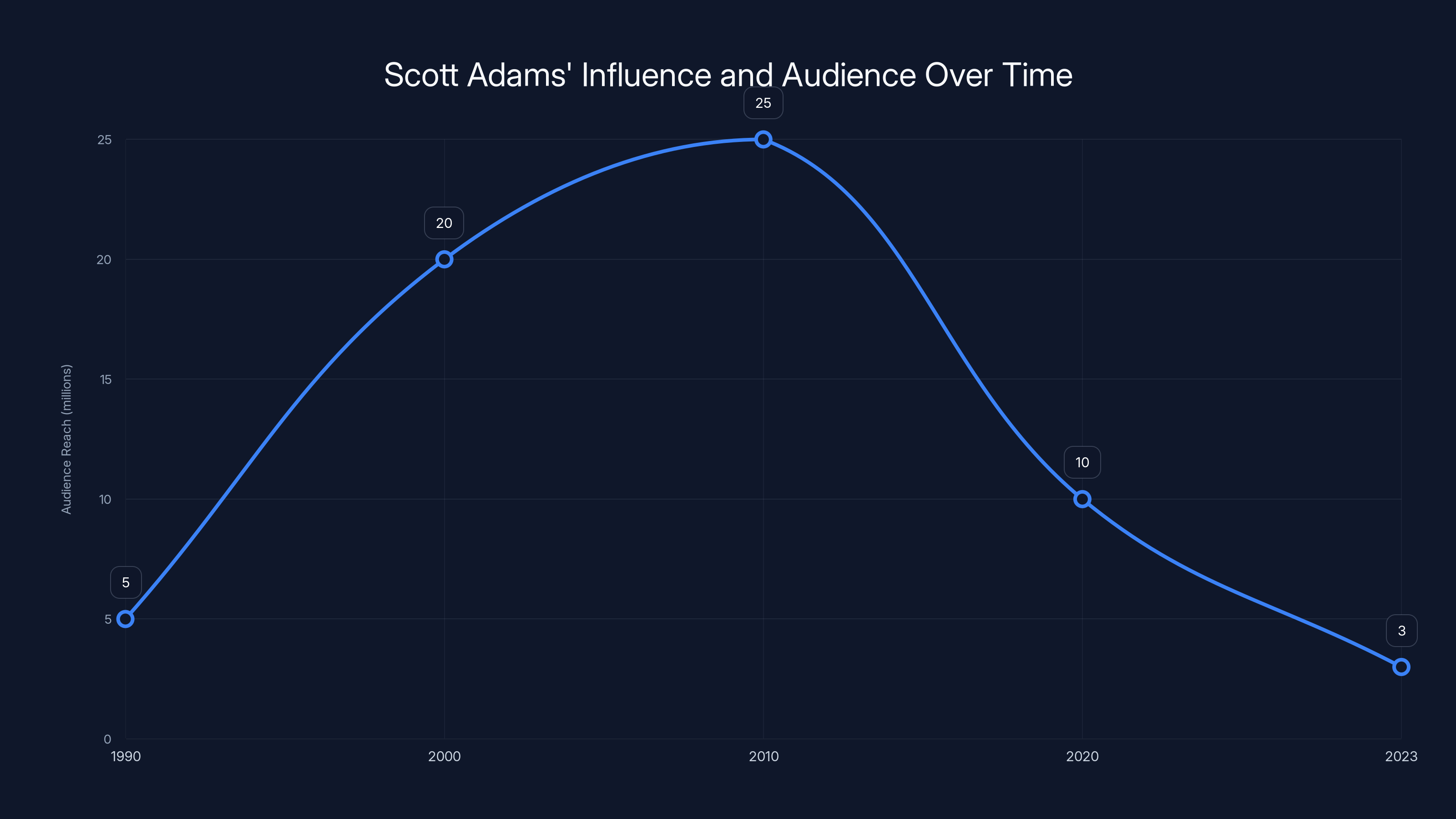

Scott Adams' audience peaked in the early 2000s with Dilbert's widespread popularity, but declined significantly in the 2020s due to controversial political commentary. Estimated data.

Cancel Culture and Consequences: Was Adams Unfairly Treated?

Scott Adams' cancellation raises important questions about accountability, fairness, and the consequences of public statements in the modern media environment. Different observers interpret the events quite differently based on their political perspectives and views on cancel culture.

Adams and his supporters argue that he was unfairly maligned and that his statements were taken out of context or distorted by hostile media. They point out that he was engaging in political commentary and analysis, not making explicit threats or inciting violence. They suggest that newspapers dropped Dilbert not because the comic itself was problematic, but because of pressure from woke activists who couldn't tolerate conservative perspectives.

Critics counter that Adams' statements, particularly about race, went beyond political commentary into territory that was genuinely offensive and harmful. They argue that calling Black Americans who disagreed with a provocative statement a "hate group" and suggesting racial separation was advice rather than satire crossed a line that newspapers were reasonably unwilling to associate with. They note that editorial decisions about what content to publish are not censorship, but normal business decisions.

There's a legitimate underlying debate here about political tolerance and acceptable discourse in mainstream institutions. Newspapers have editorial standards and advertiser sensitivities. They have to consider not just individual comics, but their overall brand and what associations they're comfortable with. A newspaper can reasonably decide that associating their publication with certain statements or perspectives damages their brand or alienates their readership.

Adams' perspective was that newspapers should separate the creator from the work. Dilbert itself hadn't changed—the comic was still about workplace dynamics and management failures. The newspaper's responsibility was to publish good content, not to police the personal political views of creators. From this perspective, dropping Dilbert because of Adams' podcast statements was an overreaction that conflated the person with the product.

But this perspective overlooks how brand association works in modern media. In 2025, audiences don't separate creators from their work as neatly as they might have in 1995. When you publish Dilbert, you're also implicitly endorsing or at least associating yourself with Scott Adams. Readers encounter the comic with knowledge of the creator's recent controversial statements. This creates a context that newspapers felt they couldn't ignore.

There's also a question about consequences versus censorship. Nobody prevented Adams from speaking. His podcast remains available. He continues tweeting. His books remain in print. What he lost was the distribution that newspapers provided. But distribution isn't a right—it's a business arrangement. Newspapers are free to choose what content they publish, and if Adams' personal brand became toxic to them, they can decide not to carry his work.

This raises a deeper question about power and inequality in media consequences. Newspapers arguably had more power to affect Adams' career than individual activists or critics. The decision to drop Dilbert came from editorial boards and management, not from grassroots campaigns. So framing this as "cancel culture" might misidentify who holds the actual power in the situation.

The Comic Strip Industry in Decline: Dilbert's Fate in Context

To fully understand what happened to Dilbert, it's important to recognize that the entire newspaper comic strip industry has been in decline for years. This isn't unique to Dilbert or to the controversies surrounding Adams. It's a structural shift in media consumption.

Newspapers themselves have been consolidating and shrinking since the rise of the internet. Fewer people read physical newspapers. Those who do are generally older and often less engaged with political Twitter and social media discourse. Comic strip syndication—once a primary source of income for cartoonists—has become a declining business.

Most successful cartoonists have diversified or pivoted entirely away from newspaper syndication. Some focus on graphic novels and collections that appeal to younger audiences. Others have moved to digital platforms, Patreon-based models, or merchandise. The newspaper comic strip, once the primary way to reach a mass audience, is now a niche platform.

Dilbert's decline would likely have happened anyway due to structural industry changes. The newspapers carrying Dilbert were themselves struggling financially. As print audiences aged and younger readers got their content from digital sources, comic strip syndication became less central to newspaper business models. Some newspapers might have eventually dropped Dilbert regardless of Adams' statements, simply due to declining reader interest or budget cuts.

But while the newspaper comic strip industry was declining anyway, the controversies clearly accelerated Dilbert's specific decline. A comic strip that might have gradually lost circulation due to industry trends instead lost most of its syndication within months due to editorial decisions about Adams' statements.

Adams himself often framed his cancellation as evidence of cancel culture and intolerance. But it's worth considering whether the newspaper cancellations would have happened at all in a different political moment or if Adams had made similar statements in a different way. The visibility and severity of the backlash was partly a function of timing, technology, and the particular intensity of political divisions in 2022-2023.

Legacy Questions: What Does Scott Adams Leave Behind?

As we assess Scott Adams' legacy, we face a complicated picture. Undeniably, he created something remarkable in Dilbert. For a period of roughly two decades, he was one of the most influential satirists in American culture. He gave voice to millions of workers' frustrations with corporate dysfunction. He made it okay to acknowledge that management was often incompetent and that workplace meetings were frequently pointless. In this sense, he shaped how people understand and talk about work.

But his final decade overshadows this earlier achievement. Rather than being remembered primarily for creating Dilbert, there's a real possibility he'll be remembered primarily for the controversial statements that ended his career as a syndicated cartoonist. This is partly unfair—the quality of his earlier work hasn't changed—but it's also how historical memory works. Later actions and statements often recontextualize earlier work.

Adams' career raises important questions about the relationship between art and artist, between legacy and responsibility. Can we appreciate Dilbert's insights about workplace culture while simultaneously criticizing Adams' later statements? Most people would say yes, we can and should do both. We can recognize that a creator made genuine contributions while also acknowledging that they made mistakes or crossed ethical lines.

But Adams' own path suggests that the separation between creator and work isn't always possible. When he made controversial statements, those statements became inseparable from Dilbert. Readers couldn't encounter the comic strip without thinking about Adams' podcast remarks. Newspapers couldn't publish the comic without implicitly endorsing their cartoonist. The integration of creator and work is stronger in modern media than Adams perhaps recognized.

There's also a question about redemption and whether Adams could have recovered from the controversies. If he had offered genuine apologies, acknowledged harm, and committed to different behavior, perhaps the narrative would have shifted. But instead, he doubled down, reframed critics as unfair, and created a subscription service explicitly positioned around continuing provocative content. This made reconciliation with his former newspaper audience nearly impossible.

For future cartoonists and satirists, Adams' story offers a cautionary tale: building something valuable takes decades, but losing audience trust can happen very quickly. The distribution channels that took years to establish can be abandoned in months. And in modern media, personal brand and creative work are inseparably intertwined.

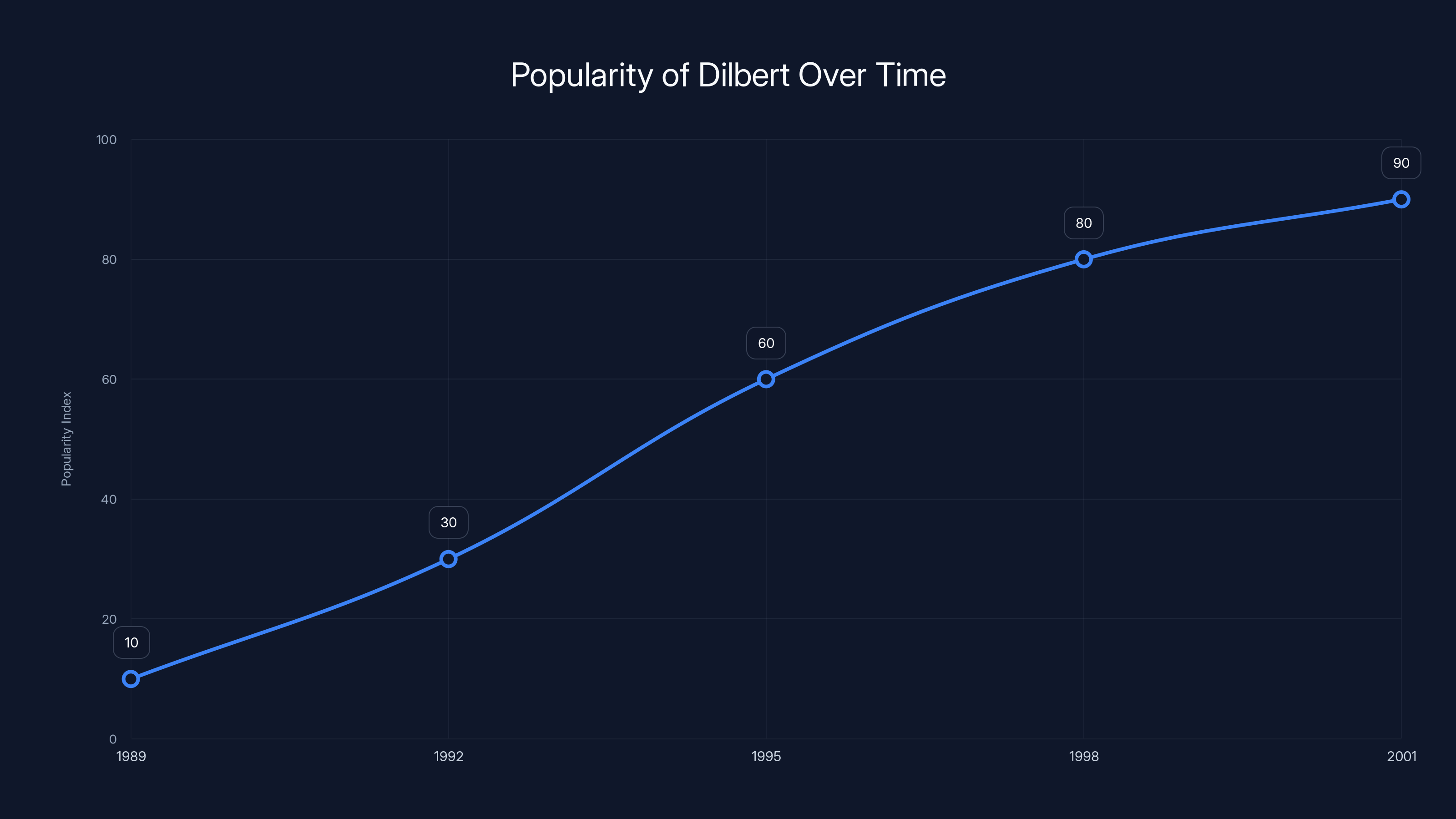

Dilbert's popularity grew rapidly from its inception in 1989, peaking in the late 1990s as it became a cultural touchstone for workplace satire. (Estimated data)

The Broader Impact: How Dilbert Changed Workplace Culture

Regardless of how we ultimately judge Scott Adams as a person or creator, Dilbert had genuine cultural impact beyond entertainment. The comic strip changed how people talked about and understood workplace dysfunction.

Before Dilbert, workplace frustration and corporate absurdity were often seen as individual problems. If you were frustrated with your job, perhaps you weren't a good fit for corporate work. If you couldn't understand your manager's decisions, perhaps you lacked the context to judge. Dilbert reframed workplace dysfunction as a systemic problem. The Pointy-Haired Boss, the senseless meetings, the incompetent executives—these weren't individual failings but features of corporate structure itself.

This reframing had real effects. It validated workers' frustrations and made them feel less isolated. It gave managers language to think about their own organizations differently. It made workplace absurdity visible and discussable in ways that mere complaining couldn't achieve.

Adams also influenced business writing and management thinking. "The Dilbert Principle"—the observation that organizations tend to move incompetent workers upward to remove them from productive roles—is now a recognized concept in management literature. Other writers and researchers have built on the framework Adams established.

The comic also provided a cultural counterweight to corporate messaging and management-speak. When executives talked about synergy and optimization, Dilbert pointed out how often these terms obscured rather than clarified. This skepticism toward corporate language has probably influenced actual workplace discourse, even among those who've never read the comic.

In this sense, Dilbert may have left the world better than Adams found it. The comic strip contributed to a culture where workplace dysfunction is explicitly acknowledged and discussed rather than silently endured. Whether that's attributable to Adams' genius or to broader cultural shifts is debatable, but Dilbert clearly played a role.

Modern Satire and Its Discontents: What Happened to Workplace Comedy

One might expect that with Dilbert's newspaper presence eliminated, another comic strip would emerge to fill the gap and provide workplace satire for modern audiences. Interestingly, this hasn't really happened. Very few comic strips focus on workplace culture anymore.

Part of this is technological. Workplace culture is now discussed through podcasts, newsletters, Twitter threads, and Tik Tok videos rather than through comic strips. The medium itself has shifted away from comics. Young workers encountering workplace absurdity for the first time are more likely to discover it through social media than through newspaper comics.

But there's also something about the nature of modern workplace culture that might make Dilbert-style satire less relevant. The problems Dilbert addressed—senseless meetings, incompetent middle management, bureaucratic waste—were characteristic of large, stable corporate hierarchies. The modern workplace is increasingly characterized by startup culture, remote work, gig economy positions, and rapid organizational change.

A Pointy-Haired Boss managing a stable corporate division for 20 years is a very different thing from a startup founder who might be fired by investors next quarter. The incompetence Dilbert mocked was often the incompetence of stability and complacency. Modern workplace dysfunction more often stems from rapid change, unclear direction, and the frenzy of competition in venture-backed startups.

Dilbert addressed a specific historical moment: the corporate consolidation of the 1990s and 2000s, the rise of management consultants, the expansion of IT departments, and the entrenchment of middle management layers. That world is still present, but it's no longer the primary experience of work for many people, especially younger workers.

The Death of Scott Adams: What It Means for His Legacy

Scott Adams' death from prostate cancer at age 68 closes the final chapter on one of the most significant satirists and cartoonists of the late 20th century. He created a cultural artifact—Dilbert—that genuinely mattered and shaped how millions of people understood their work lives.

But his death also crystallizes a complicated legacy. Rather than being remembered as the creator of a beloved comic strip that brought laughter and insight to millions, Adams will likely be remembered for the controversies that ended his career. The narrative arc of his life doesn't follow the trajectory of a triumphant artist. Instead, it's the story of someone who achieved extraordinary success and then gradually lost it, partly through circumstances beyond his control (industry decline, changing media consumption) and partly through his own choices (increasingly inflammatory statements, inflexible response to criticism).

For those who loved Dilbert, his death may prompt them to revisit the comics and rekindle their enjoyment of that era of the strip. For those who grew frustrated with Adams' political statements, his death may seem less like a loss and more like a conclusion to a narrative that had already reached its endpoint.

What's certain is that Dilbert represented something specific and time-bound. It captured a particular moment in American corporate culture and gave voice to frustrations that millions of workers felt. Whether future generations will still find Dilbert funny and relevant, or whether it will seem like an artifact of a bygone era, remains to be seen.

Adams himself seemed less concerned with his posthumous fame than with the philosophical question of whether his risk-benefit calculation regarding Jesus Christ would prove correct. It's a very Scott Adams kind of question to end on—practical, calculating, and tinged with irony even in mortality.

Lessons for Content Creators and Public Figures

Scott Adams' career provides several important lessons for anyone building an audience or personal brand.

First, understand that building something takes far longer than destroying it. Adams spent decades creating Dilbert, building syndication relationships, establishing himself as a cultural authority, and developing revenue streams. He lost most of that in less than two years. The asymmetry between creation and destruction is stark.

Second, recognize that audience tolerance has limits and varies significantly based on context. Dilbert worked because it was universal satire that most people could enjoy regardless of their politics. When Adams shifted to more explicitly partisan statements, he lost the universality that had made him broadly appealing. Different audiences have different tolerances for political content and controversial statements from creators.

Third, understand that in modern media, the creator and the work are inseparable. Audiences don't compartmentalize the way Adams perhaps hoped they would. When someone encounters Dilbert, they do so with knowledge of who created it and what that person has said publicly. This context shapes the experience of the work.

Fourth, recognize that audience relationships built through one-way communication (newspapers) are more fragile than you might think. When papers had the power to distribute Dilbert to millions of people who never specifically sought it out, that distribution was extremely valuable. But it was also conditional. When circumstances changed, that distribution evaporated. Diversifying your audience relationship and building more direct connections would have provided more stability.

Fifth, understand the limitations of doubling down. When Adams faced criticism, his instinct was to reframe himself as the victim of cancel culture and continue making controversial statements. But this approach doesn't typically rebuild lost relationships or recover lost audience. It reinforces the division and cements people's decisions to move away from your work.

FAQ

What was Scott Adams' most significant cultural achievement?

Scott Adams' most significant cultural achievement was creating Dilbert, a comic strip that revolutionized how people understood and discussed workplace dysfunction. At its peak, Dilbert appeared in approximately 2,000 newspapers with a daily readership estimated between 60 and 80 million people. The comic strip provided a shared language for workers to discuss management incompetence, corporate absurdity, and bureaucratic waste. Adams also introduced the concept of "The Dilbert Principle"—the observation that organizations tend to promote incompetent workers upward to remove them from productive roles—which became recognized in management literature and organizational theory. The comic fundamentally changed workplace culture by making dysfunction explicitly visible and discussable rather than silently endured.

Why was Dilbert cancelled from newspapers?

Dilbert was cancelled from major newspapers for two primary reasons related to Scott Adams' public statements rather than the comic itself. In 2022, Adams introduced the strip's first Black character but used the character to mock what he perceived as excessive "woke" culture and progressive identity politics, leading over 75 newspapers to drop the strip. In 2023, Adams made more inflammatory statements on his podcast, describing Black Americans who disagreed with the phrase "It's okay to be white" as a "hate group" and suggesting that white people should "get the hell away from Black people." These remarks led to cancellation from most major metropolitan newspapers. While newspaper circulation was already declining industry-wide, the combination of controversial statements and newspaper editorial decisions to distance themselves from Adams' personal views accelerated Dilbert's elimination from mainstream distribution.

How did Scott Adams attempt to recover his career after losing newspaper syndication?

After losing newspaper syndication, Scott Adams pursued several strategies to maintain his career and income. He launched "Dilbert Reborn," a subscription-based version of the comic strip positioned as content "too spicy for the general public," though this subscription model struggled to gain significant adoption. Adams also focused more intensely on writing books, particularly business and political books that allowed him to articulate his perspectives at greater length to audiences already interested in his ideas. He maintained a prominent presence on social media, particularly Twitter, where he engaged in political debates with critics and followers. Most importantly, Adams created and regularly hosted the "Real Coffee with Scott Adams" podcast, which became his primary platform for regular engagement with supporters and allowed him to maintain direct communication without traditional media gatekeepers. These alternative platforms provided income and audience engagement but never restored the cultural dominance he'd achieved through newspaper syndication.

Was Scott Adams a victim of cancel culture or did his statements cross legitimate lines?

This question has no objective answer and different observers interpret the events very differently based on their political perspectives. Adams and his supporters argue that he was unfairly maligned, that his statements were taken out of context, and that he was expressing legitimate political viewpoints that newspapers were intolerant of. Critics counter that his statements—particularly about race—went beyond political commentary into territory that was genuinely offensive and harmful. They note that editorial decisions about what content to publish are normal business judgments, not censorship. A reasonable assessment acknowledges both perspectives: Adams expressed his views as a private citizen and faced no legal consequences, but newspapers made editorial decisions not to associate their publications with certain statements, which is within their rights. The asymmetry of consequences—his loss was severe—doesn't necessarily indicate unfairness if those consequences were a logical result of mainstream outlets' editorial standards.

How much money did Dilbert generate for Scott Adams during its peak?

Exact figures for Adams' total Dilbert earnings were never publicly disclosed, but available estimates suggest substantial revenue. At its peak, Dilbert generated an estimated $100 million in annual revenue through various sources including newspaper syndication fees, book sales ("The Dilbert Principle" and numerous Dilbert collections were bestsellers), licensing agreements (Dilbert appeared on office supplies, merchandise, clothing, and countless other products), TV animation and specials, consulting work, and speaking engagements. This diverse revenue portfolio made Adams extremely wealthy and provided him with financial independence by the 2000s. The exact portion that flowed to Adams personally depended on various contracts and arrangements with syndicators, publishers, and licensees, but his net worth was estimated in the range of tens of millions of dollars at its peak. This wealth and independence would later prove consequential—unlike many cartoonists dependent on newspapers for income, Adams had the financial ability to continue working even after newspaper syndication ended.

What was Scott Adams' educational and professional background before creating Dilbert?

Scott Adams had an engineering background and worked as a salaried employee at Pacific Bell, a major telecommunications company, in the late 1980s when he created Dilbert. His experience in corporate environments—specifically in engineering and technical roles—directly informed the observations and insights that made Dilbert successful. Adams worked full-time at Pacific Bell while simultaneously developing Dilbert comics before breakfast, during lunch breaks, and on weekends. This direct experience of corporate dysfunction wasn't theoretical but lived experience, which gave his satire credibility and specificity that pure comedy writers might lack. He spent several years in this dual-role situation before Dilbert achieved sufficient syndication and income to allow him to become a full-time cartoonist. This background in actual corporate work, combined with his ability to observe and articulate workplace dynamics, distinguished Adams from cartoonists without similar experience.

How did Dilbert's audience demographics change over time?

Dilbert's audience shifted significantly from its creation in 1989 through its peak around 2000-2010 and into its decline in the 2020s. Initially, the strip's core audience was engineers, IT workers, and middle managers—people working in technical fields or corporate hierarchies who directly experienced the dysfunction Dilbert satirized. As the strip achieved greater syndication and cultural prominence, it expanded to reach broader audiences including office workers across different industries, business students, and executives who found the satire relevant to their experience. However, the core audience remained relatively consistent: educated, white-collar workers in corporate or technical environments. When Adams shifted toward explicit political and racial commentary, the audience began fragmenting. Older readers from the original newspaper audience (who skewed older anyway as newspapers aged) tended to be more conservative and sometimes supportive of Adams' statements. Younger, more progressive readers tended to find his comments offensive and abandoned the strip. The shift from newspaper syndication to podcasts and subscription content also changed audience composition, attracting more politically aligned supporters and losing casual readers who had enjoyed Dilbert without seeking Adams' other content.

Did Dilbert influence actual corporate management practices and workplace culture?

Yes, Dilbert demonstrably influenced how people understood and discussed workplace dysfunction, and this likely had secondary effects on actual corporate practices. The comic strip provided legitimacy and visibility to critiques of corporate management that had previously been dismissed as individual employee complaints. By articulating workplace absurdity through humor and observation, Dilbert made dysfunction visible and discussable. Some evidence suggests managers and executives took the satire seriously enough to address some of the problems Dilbert mocked. Companies became more aware of the absurdity of certain management practices and the morale damage caused by pointless meetings and metrics-focused management. Additionally, Adams' concept of "The Dilbert Principle"—that organizations promote incompetent workers upward—became a recognized framework in management literature and was referenced by consultants and academics studying organizational behavior. Whether these influences led to substantial changes in actual corporate practices is debatable, but Dilbert clearly shaped the discourse around workplace management and made certain forms of dysfunction less acceptable. The comic provided vocabulary for discussing problems that had previously been seen as inevitable features of corporate work rather than problems to solve.

Conclusion: The Complicated Legacy of a Comic Strip Creator

Scott Adams' death at age 68 marks the end of an extraordinary and ultimately complicated life. He created something remarkable in Dilbert—a satirical comic strip that shaped how millions of people understood work, management, and corporate culture. For roughly two decades, he was one of the most influential and widely-read satirists in America. His observations about workplace dysfunction were so precise and resonant that they influenced not just how people talked about work, but how management scholars and corporate leaders thought about organizational structure.

But the latter part of Adams' career tells a very different story. Rather than maintaining his role as a universal satirist, he increasingly positioned himself as a political commentator. His statements about race, identity, and politics grew progressively more inflammatory. The universal audience that had embraced Dilbert fragmented into ideologically divided camps. What had taken decades to build—a presence in 2,000 newspapers and an audience of tens of millions—was lost in less than two years.

Adams' response to this decline reveals something important about how people handle loss of status and audience. Rather than reflecting on whether his statements had been problematic, he reframed himself as a victim of cancel culture. Rather than attempting reconciliation with the mainstream audience he'd lost, he doubled down on provocative commentary and created subscription services explicitly designed around "spicy" content. None of these approaches restored what he'd lost, but they did seem to reinforce the divisions that had caused the loss in the first place.

For creators, entrepreneurs, and public figures, Adams' story offers important lessons about the relationship between personal brand and creative work, about the fragility of audience relationships built through institutional distribution, and about the difficulty of recovering from lost audience trust. It's a story about how something valuable can be built slowly over decades and lost quickly, about the impossibility of fully separating the creator from the creation in modern media, and about the limitations of doubling down when circumstances call for reflection.

Adams himself seemed less concerned with these legacy questions than with his own mortality and a final philosophical gamble on religious salvation. His last recorded statement—accepting Jesus Christ as his savior with a pragmatic note about risk-benefit calculations—is characteristically Adams: even facing death, he approached major life questions as optimization problems rather than matters of pure faith.

What remains is Dilbert itself. The comic strips still exist. They're still funny. The observations about workplace absurdity are still valid. The Pointy-Haired Boss still represents something true about organizational dysfunction. Whether future generations will appreciate the comic for what it is, or whether it will be forever tainted by association with its creator's final controversies, remains to be determined. But in the moment of Adams' death, both possibilities are equally real: Dilbert as a genuine cultural achievement deserving of appreciation, and Dilbert as an artifact of a creator whose trajectory offers cautionary lessons about how power and platform can be deployed.

Key Takeaways

- Dilbert appeared in approximately 2,000 newspapers daily at its peak, reaching 60-80 million readers and fundamentally changing workplace discourse.

- Adams built a multi-million dollar franchise through syndication, books, licensing, and speaking engagements by diversifying revenue streams.

- The shift from universal satirist to political commentator fractured Adams' audience and accelerated decline after 2022 controversies.

- Adams lost newspaper syndication within two years despite building it over three decades, demonstrating asymmetry between creation and destruction.

- The integration of creator brand and creative work in modern media means personal statements directly impact audience reception of the artistic product.

- Adams' attempted recovery through subscription-based Dilbert Reborn and podcasting failed to restore his cultural influence or audience reach.

![Scott Adams, Dilbert Creator, Dead at 68: Legacy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/scott-adams-dilbert-creator-dead-at-68-legacy-2025/image-1-1768329583348.jpg)