Smartwatch Fall Detection Lawsuits: What You Need to Know [2025]

Your smartwatch is supposed to save your life. That's the promise. Fall detection technology has been marketed as a game-changer for elderly users and active people alike, with companies claiming their sensors can detect a dangerous tumble and automatically alert emergency contacts or call for help.

But here's where it gets complicated.

New lawsuits are challenging whether these features actually work as advertised. Companies like Apple, Samsung, and others are facing legal scrutiny over fall detection accuracy claims. Some users report their watches failed to detect real falls. Others claim the feature triggers false alarms from everyday activities. And now, regulators and attorneys are asking harder questions about whether marketing claims match reality.

This isn't a theoretical issue anymore. There are real cases, real users, and real questions about liability. If you own a smartwatch with fall detection, or you're considering buying one, you need to understand what's actually happening behind the scenes and what the legal landscape looks like right now.

Let's break down the fall detection wars, what the lawsuits are really about, and what happens next.

TL; DR

- Fall detection lawsuits target major smartwatch makers over accuracy claims and false advertising allegations

- The technology is imperfect and relies on accelerometers and algorithms that can't distinguish between real falls and sudden movements

- Apple Watch and Samsung Galaxy Watch are among the most commonly cited in legal disputes

- Regulatory uncertainty means fall detection features could face stricter oversight or even restrictions in some markets

- False alarms carry real costs including emergency responder time, user frustration, and potential liability for manufacturers

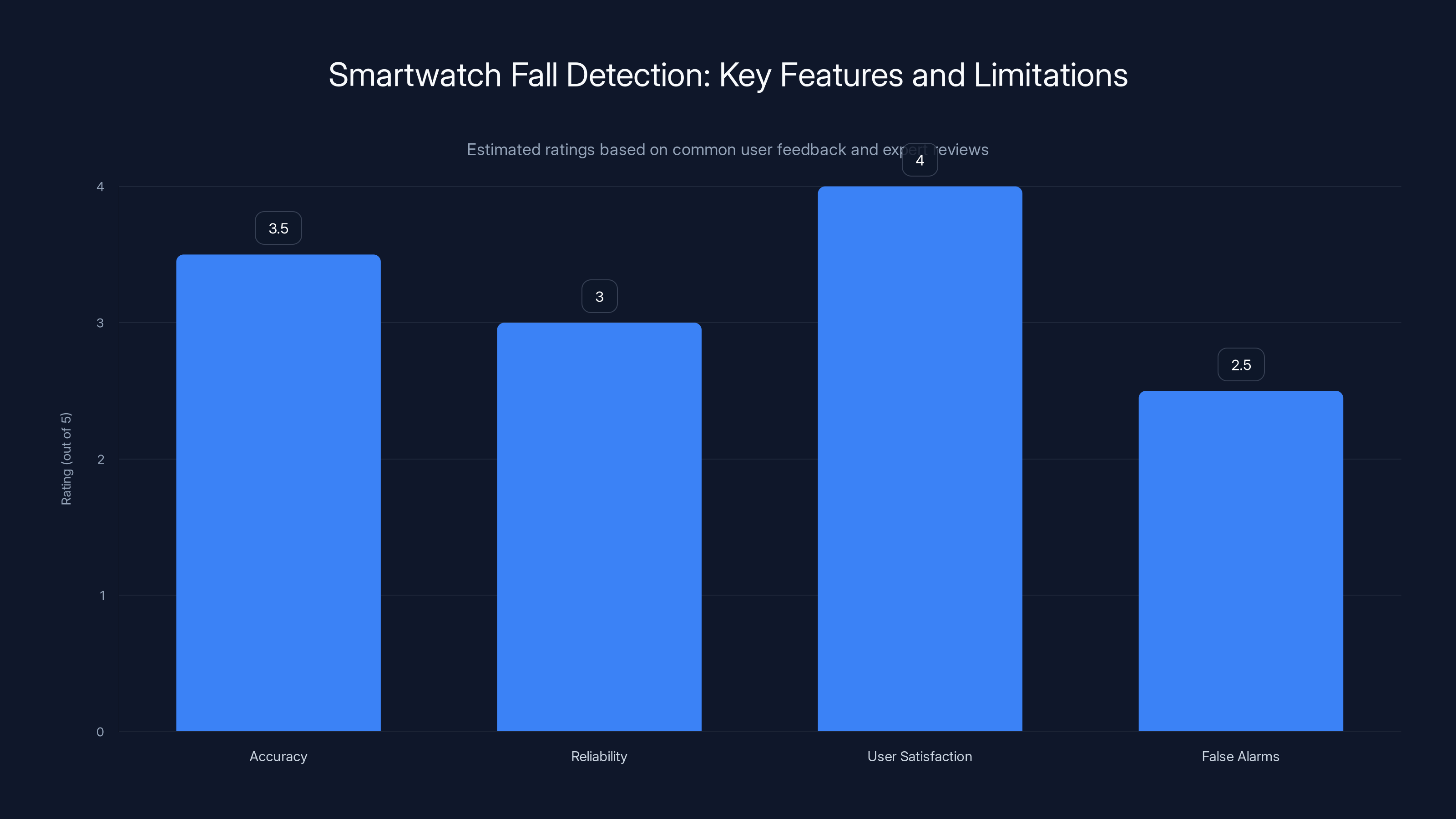

Estimated data shows that while user satisfaction is relatively high, accuracy and reliability of fall detection are moderate, with false alarms being a notable issue.

What Is Fall Detection Technology and How Does It Actually Work?

Fall detection sounds straightforward. Your smartwatch is constantly monitoring for sudden changes in motion and acceleration. When it detects a pattern that matches a "fall," it triggers an alert. Sounds simple. Reality is messier.

The technology relies on a combination of sensors embedded in the smartwatch. The primary sensor is an accelerometer, which measures changes in velocity and gravitational force. Think of it as a motion detector that's constantly sampling data dozens of times per second. When your watch detects a rapid downward acceleration followed by an impact (sudden stop), it flags this as a potential fall.

But here's the problem: your watch can't actually see what's happening. It's making educated guesses based on mathematical patterns.

The sensor hardware and what it measures:

Smartwatch manufacturers also use gyroscopes, which measure rotation and orientation. Some newer devices include barometric sensors that track altitude changes. Together, these sensors feed data into algorithms designed to distinguish between a genuine fall and, say, you quickly bending down to pick something up or jumping into a pool.

The algorithms are trained using datasets of real falls. Companies collect video of people actually falling, record the sensor data from smartwatch devices during those falls, and then build machine learning models to recognize similar patterns in real-time. It's actually pretty sophisticated work.

But training data has limitations. Falls don't all look the same. A 75-year-old person falling from standing height generates different sensor data than a 35-year-old person falling while running. A fall onto carpet feels different from a fall onto concrete. Regional variations matter too—gravity varies slightly depending on latitude.

Why false positives happen:

Your watch might interpret a sudden jump as a fall. Dropping your arm quickly while reaching. Sitting down hard. Getting up from a chair at the wrong speed. These activities generate acceleration and impact-like patterns that can fool the algorithms.

This is why smartwatch makers built in a critical delay. When your watch detects what it thinks is a fall, it doesn't automatically call emergency services. Instead, it prompts you on the screen asking "Are you okay?" If you don't respond or tap "I need help" within a set time (usually 30-60 seconds), then the watch proceeds to contact emergency services or your emergency contact.

It's a safety buffer. But it's also an admission that the system isn't 100% certain. And it creates a new problem: what if you're injured and can't respond to the prompt? What if you don't see the notification because your arm is pinned or you're unconscious?

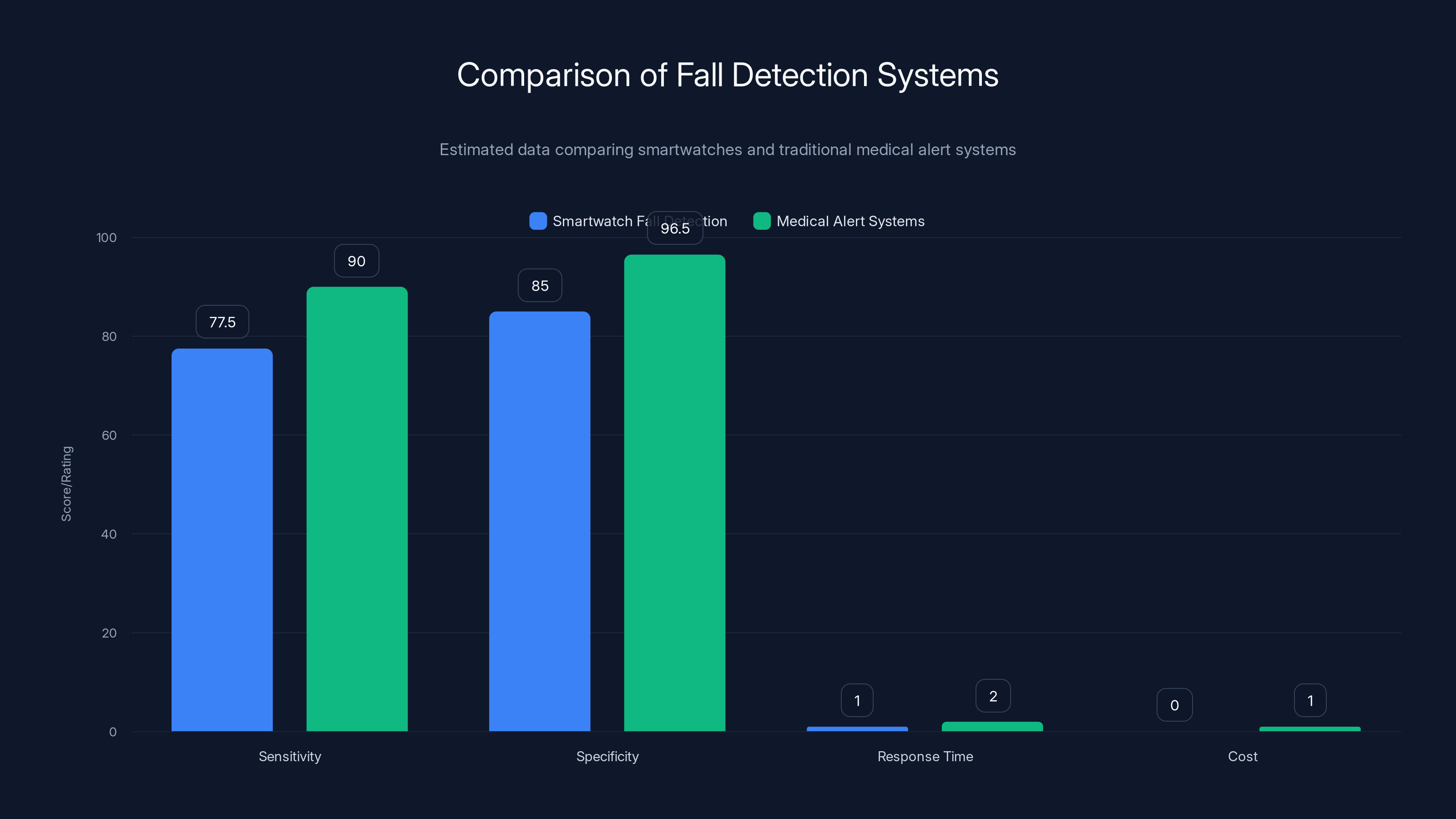

Traditional medical alert systems outperform smartwatches in sensitivity and specificity but at a cost. Smartwatches offer faster response times and no additional cost, but with reduced reliability. (Estimated data)

The Legal Challenge: What the Lawsuits Actually Claim

The legal cases targeting smartwatch fall detection aren't new in spirit, but they're intensifying. The core argument is this: companies made specific claims about fall detection capability in their marketing materials and product documentation, but the feature doesn't perform reliably enough to justify those claims.

False advertising allegations:

Plaintiffs' attorneys are arguing that smartwatch manufacturers overstated the reliability and accuracy of fall detection features. When Apple markets the Apple Watch Ultra as having "advanced fall detection," or when Samsung advertises the Galaxy Watch 6 as automatically detecting falls, there's an implied promise about how well these systems work.

But internal testing data—which sometimes surfaces through litigation discovery—suggests the systems fail in specific scenarios. A user might fall backwards and not have their arm extended (where the accelerometer is positioned). A person might fall slowly rather than suddenly. Someone could fall on soft surfaces that don't trigger the impact detection.

The disconnect between marketing claims and real-world performance is the legal issue.

Accuracy and efficacy disputes:

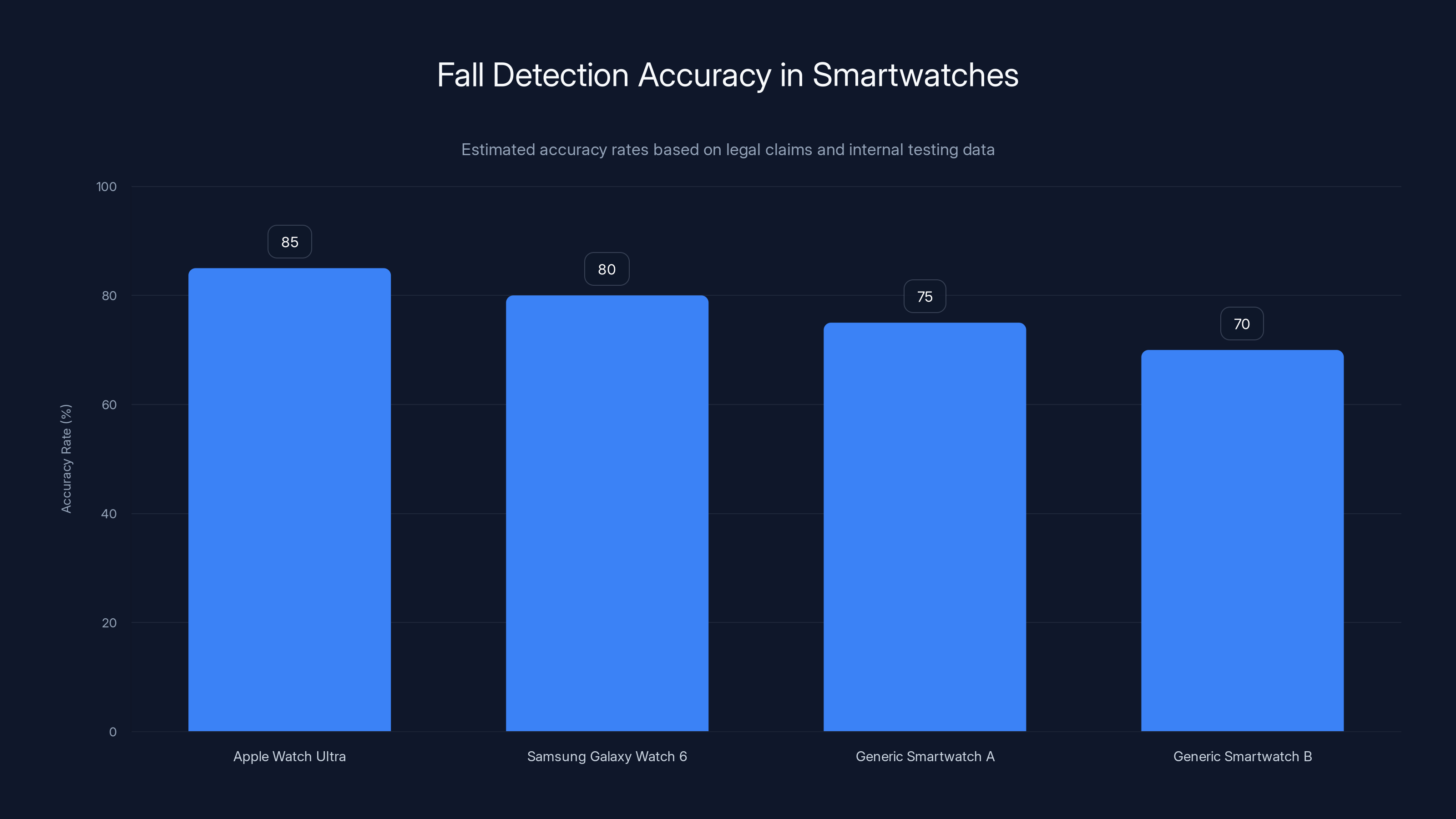

What counts as "good enough" for fall detection? If the feature works 85% of the time, is that acceptable? What about 70%? Industry standards don't exist yet, which is actually a huge problem for these lawsuits. Without an agreed-upon benchmark, it's difficult to prove a product is defective.

Some cases focus on specific user populations. Fall detection may work fine for a 40-year-old who falls during exercise but fail for an 80-year-old with slower, stumbling falls. That's a product liability issue: the device was sold to both users with the same promised functionality, but it only delivers for one group.

Liability concerns for failing to detect real falls:

This is darker. What happens when someone actually falls, their watch doesn't detect it, and they suffer a serious injury because no one came to help them? The family might sue, claiming the smartwatch marketed itself as a safety device but failed in the critical moment it was supposed to protect them.

Manufacturers have legal language in their terms of service stating that fall detection is not a substitute for professional medical devices. But marketing materials often emphasize safety and peace of mind, creating emotional expectations that exceed the legal disclaimers.

The Apple Watch Fall Detection Controversy: A Deep Dive

Apple didn't invent fall detection, but Apple was one of the first companies to integrate it into a mainstream consumer smartwatch. This made them a target when problems emerged.

The Apple Watch fall detection works through a combination of motion analysis and impact detection. The device can sense when you're standing, moving, or falling. When it detects a fall, the screen displays an alert with large buttons. You can dismiss it if it was a false alarm, or you can confirm you need help.

If you don't respond within 60 seconds, the Apple Watch automatically calls emergency services. It also sends a message to your emergency contacts with your location. For people living alone or with mobility challenges, this is genuinely life-saving.

But complaints have mounted. Users report scenarios where the feature should have triggered but didn't.

Real-world failure scenarios:

One documented case involved someone falling down stairs. Their Apple Watch didn't detect it because they maintained contact with the banister while falling. The device interpreted this as controlled descent rather than a fall.

Another involved a person falling while lying down. Since they didn't go from vertical to horizontal with sufficient acceleration, the sensors didn't flag it as a fall. They could have been lying on the ground for hours before being discovered.

These aren't edge cases in the legal sense—they're exactly the situations fall detection is supposed to handle. An elderly person isn't always standing upright when they fall. They might already be in a weakened state, partially supported by furniture.

Apple's response and updates:

Apple has made improvements over the years. The Series 8 and Series 9 received updated algorithms. The Ultra version has more sensitive sensors intended to catch more falls. But these updates haven't eliminated the underlying issue: algorithmic uncertainty.

The company has invested significant engineering resources into fall detection. They've probably spent millions on research and development. But throwing engineering at an algorithmic problem has inherent limitations. You can't use hardware alone to fix a software logic problem.

Marketing claims vs. technical reality:

Apple's marketing materials emphasize safety and peace of mind. Advertisements show elderly users living independently with Apple Watch protecting them. The implicit message is that you can rely on this feature. Yet Apple's terms of service contain disclaimers stating that fall detection is not a medical device and shouldn't be relied upon as a substitute for professional emergency systems.

This gap—between what the marketing suggests and what the legal fine print allows—is the foundation of the lawsuits.

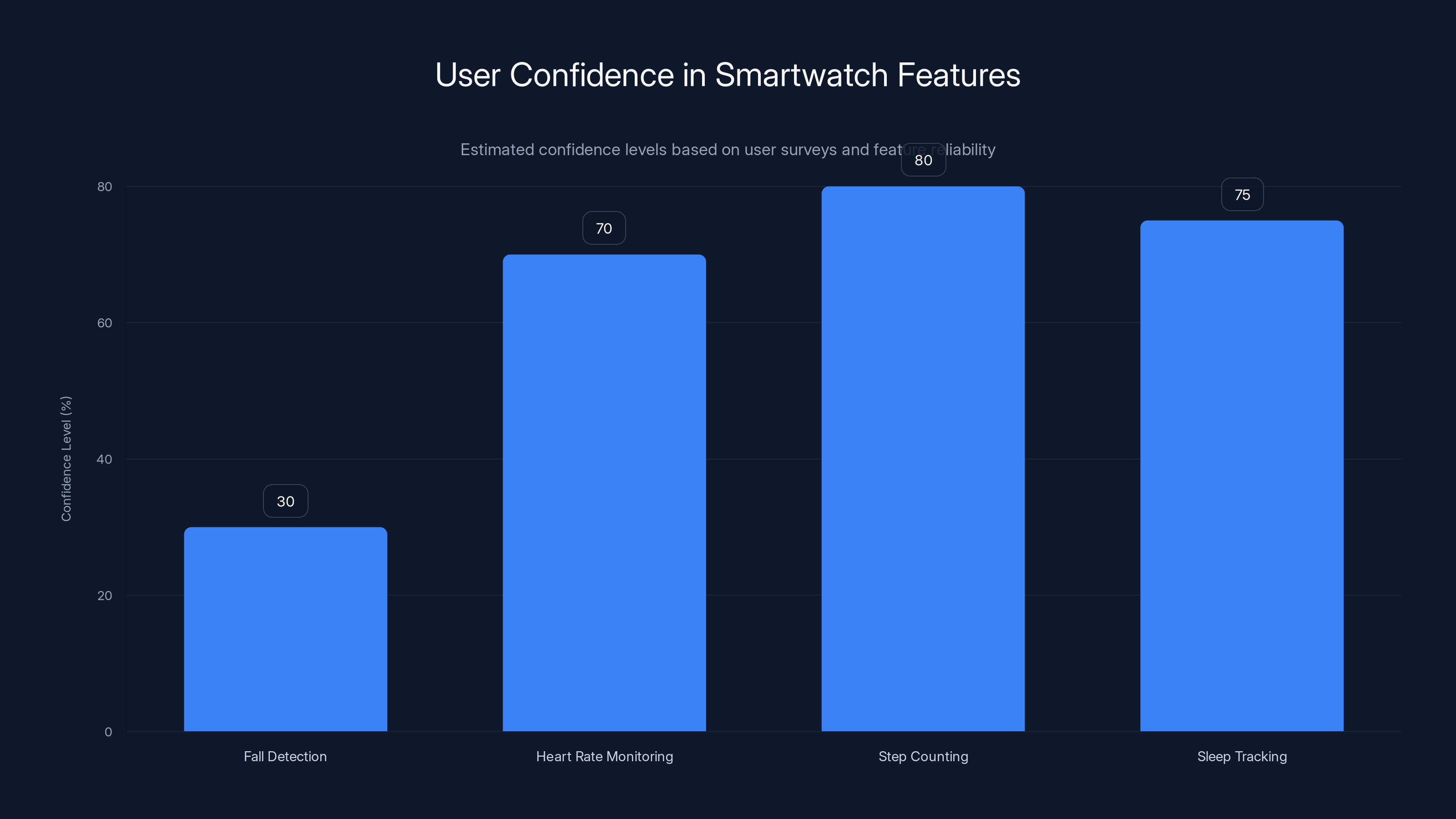

Estimated data shows that user confidence in fall detection is significantly lower compared to other smartwatch features, reflecting trust issues due to reliability concerns.

Samsung Galaxy Watch and Other Competitors Under Fire

Apple isn't alone in the fall detection legal crosshairs. Samsung Galaxy Watch devices face similar challenges, as do smartwatches from Fitbit, Garmin, and others. Each manufacturer makes fall detection claims, and each faces questions about accuracy and reliability.

Samsung's fall detection implementation:

Samsung's approach is similar to Apple's but with different algorithmic tuning. The Galaxy Watch 5 and 6 use accelerometers to detect falls, with a 30-second notification window before contacting emergency services. Samsung markets this as advanced protection for older users.

Complaints about Samsung's fall detection often involve false positives. Users report their Galaxy Watches triggering fall alerts while playing sports, gardening, or even just sitting down quickly. Each false positive is embarrassing—you're getting an emergency call asking if you're okay when you're perfectly fine.

But false negatives are worse. There are documented cases where Galaxy Watch owners fell and the device didn't alert them or their emergency contacts.

Fitbit's different approach:

Fitbit focuses heavily on the elderly market and uses slightly different sensor arrangements. Their fall detection also relies on accelerometer data but incorporates heart rate monitoring as a secondary signal. The theory is that a fall is often accompanied by a heart rate spike, so combining these signals reduces false alarms.

But Fitbit still faces the same fundamental challenge: distinguishing genuine falls from normal movement. Heart rate changes also happen when you're exercising intensely, stressed, or anxious.

Garmin's position:

Garmin, traditionally focused on outdoor sports and adventure, has been more cautious about fall detection marketing. Their approach is similar to other manufacturers technically, but they've been more explicit about limitations. This positioning may shield them from some legal exposure, though it also limits the market they're targeting.

The pattern across manufacturers:

What's clear is that no smartwatch company has solved fall detection perfectly. Every implementation has trade-offs. More sensitive algorithms catch more real falls but trigger more false alarms. More conservative algorithms reduce false positives but miss real falls.

This trade-off is inherent to the technology. And it's exactly what the lawsuits are focused on: companies claiming to have solved it, when actually they've just chosen a different point on the accuracy-versus-false-alarm spectrum.

Why Fall Detection Fails: Technical Limitations and Real-World Challenges

Understanding why fall detection fails requires understanding the fundamental limitations of the technology. It's not laziness or negligence on the manufacturer's part. It's physics and mathematics pushing back against the problem.

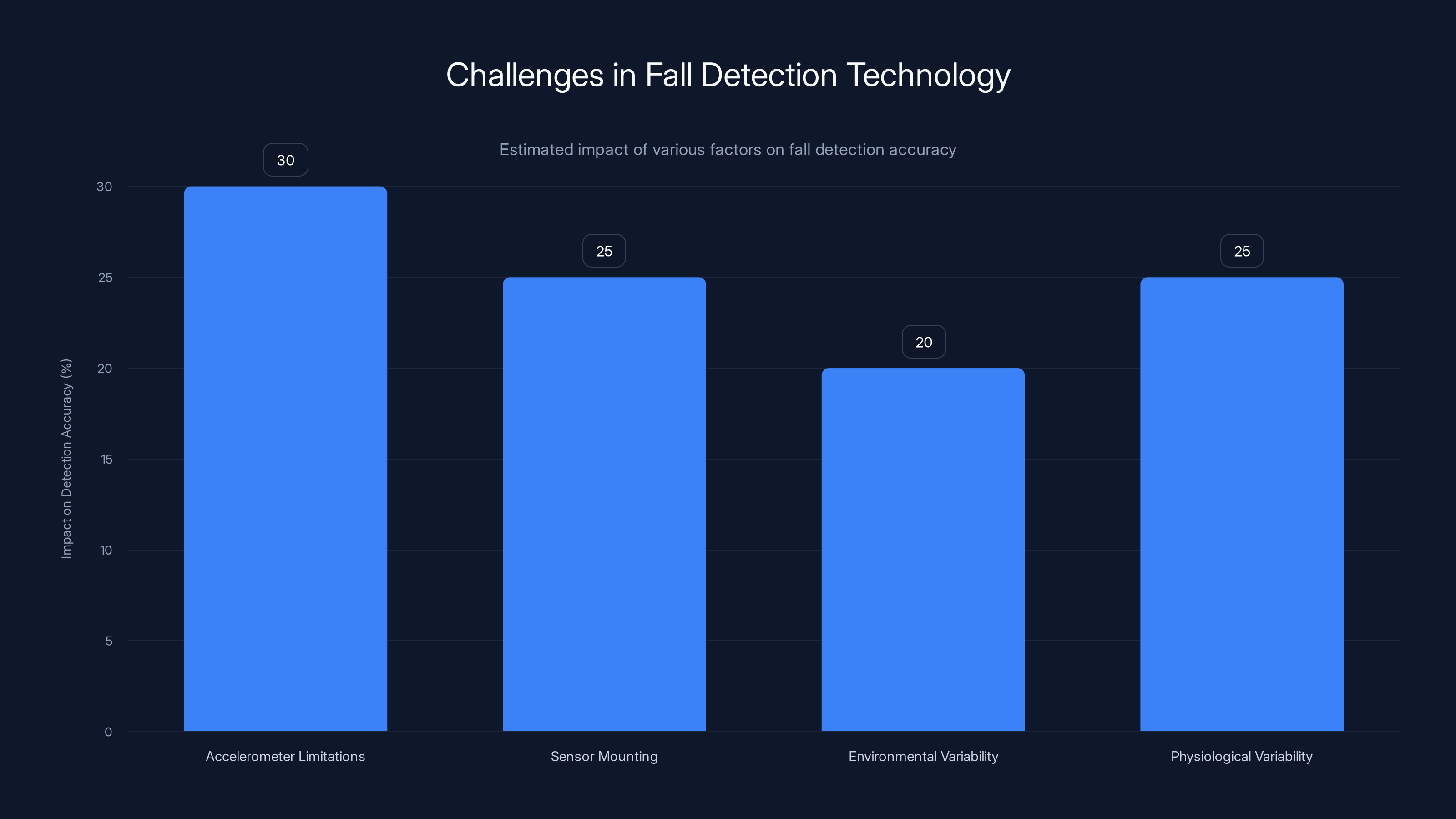

Accelerometer limitations:

An accelerometer measures proper acceleration—the change in velocity experienced by an object. But accelerometers can't directly measure the thing we actually care about: whether someone has lost their footing and is falling to the ground.

Think about what actually happens during a fall. You lose your balance. Gravity pulls you down. You might touch objects on the way down (handrails, walls, furniture). You hit the ground. Each of these moments generates different acceleration patterns.

A genuine fall might generate accelerations of 2-3 times gravitational force, depending on how fast you fall and what you hit. But shaking your arm vigorously, jumping, or sitting down hard can generate similar accelerations. Without additional context—without knowing you were standing, without knowing the room layout, without seeing the actual event—the accelerometer data alone is ambiguous.

The sensor mounting problem:

Your smartwatch is worn on your wrist. This is convenient for the user and terrible for fall detection. When you fall, your wrist motion might be completely different from your body's motion. You might instinctively extend your arm to catch yourself. You might tuck your arm during a fall. You might fall on the side where your watch is worn, dampening the sensor's ability to detect the impact.

Mobile medical alert devices worn on the hip have a natural position that correlates more directly with body position. A smartwatch on your wrist is further removed from the fall event itself.

Environmental and physiological variability:

Falls are context-dependent. Falling on carpet creates different impacts than falling on tile. Falling down stairs creates a series of impacts. Falling into water creates a completely different acceleration signature. Older people often fall slowly—they lose balance and gradually descend—rather than dropping suddenly.

Young, healthy people generate distinct fall patterns from older people with reduced mobility. Someone falling while running generates different sensor data than someone stumbling and barely catching themselves.

This variability is why fall detection algorithms need extensive training data covering diverse populations, fall types, and environments. But collecting this data is expensive and logistically challenging. You're asking people to deliberately fall in controlled settings.

Algorithmic uncertainty:

Machine learning models are probabilistic. They don't definitively classify something as a fall. Instead, they assign a confidence score. Fall detection algorithms likely operate at something like 85% confidence for the movements they classify as falls. That means 15% of the time, the system is guessing wrong about something.

Manufacturers have to set a threshold for action. Should the algorithm trigger an alert at 60% confidence? 70%? 80%? Higher thresholds catch fewer real falls (false negatives). Lower thresholds catch more real falls but trigger more false alarms (false positives).

Each manufacturer chooses differently. There's no objective "correct" answer. But there is a point beyond which the false alarm rate becomes unacceptable. Some users report 3-5 false fall alerts per week. That's dozens of unnecessary emergency calls. Eventually, they turn off the feature entirely, eliminating its utility.

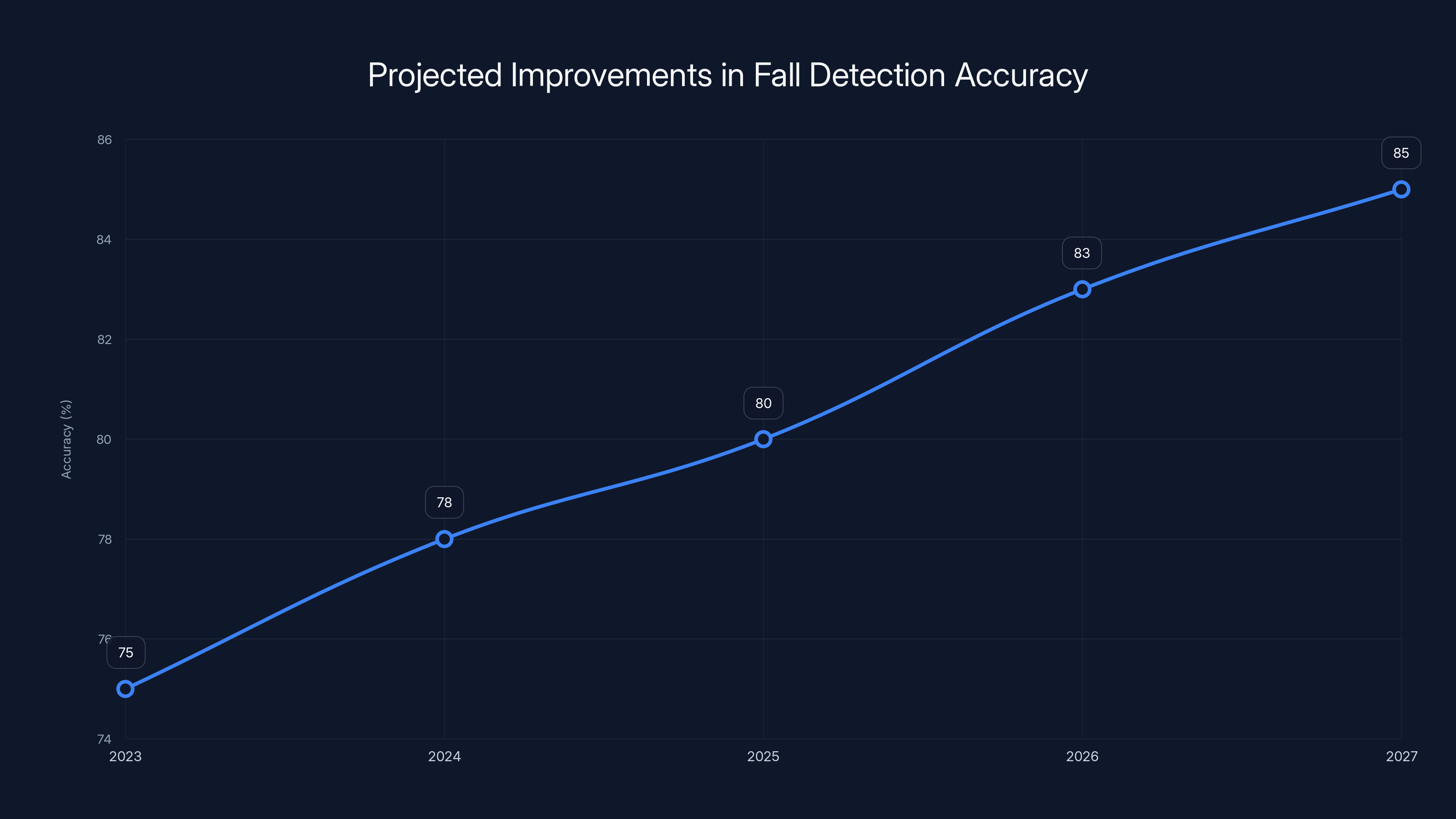

Fall detection accuracy is projected to improve incrementally from 75% in 2023 to 85% by 2027, driven by advancements in sensor technology and data integration. Estimated data.

The Regulatory and Legal Landscape in 2025

Fall detection exists in a regulatory gray zone. The devices are marketed as health and safety tools, but they're not classified as medical devices in most markets. This creates an odd situation where companies can make health-related claims without going through medical device approval processes.

FDA's current position:

In the United States, the FDA hasn't actively regulated smartwatch fall detection features as medical devices. This is partly because fall detection is positioned as a convenience feature, not a replacement for actual medical alert systems. Actual medical alert systems—wearable devices specifically designed for detecting falls in elderly people—go through FDA approval and are held to higher standards.

But there's pressure building. Senators and consumer safety advocates have questioned whether fall detection claims should trigger medical device regulations. If smartwatch makers are going to position fall detection as a safety feature, shouldn't they have to prove it works reliably?

The FDA is likely to clarify its position in the next few years. This could go two ways: either fall detection gets explicitly carved out as a non-medical feature (meaning lighter regulation), or it gets classified as a medical device requiring approval and ongoing monitoring.

European Union approach:

Europe has been stricter about health claims. The European Commission and national health authorities are more likely to scrutinize fall detection marketing. Some regulators have already questioned whether marketing falls detection as a safety feature without concrete evidence of efficacy violates consumer protection laws.

The Medical Device Regulation in Europe is broader than FDA rules. A device marketed as helping detect medical events might be classified as a medical device even if traditional smartwatch makers never intended that classification.

Class action litigation:

Multiple class action lawsuits are already filed or in preparation. These cases typically target either false advertising or product liability. False advertising cases argue that marketing materials overstated fall detection capability. Product liability cases argue that the device failed to perform its intended function and caused harm through that failure.

Class actions in this space are complicated because fall detection failure is hard to prove causally. If someone falls and their watch doesn't detect it, how do you prove the watch was the cause of any injury? They might have been injured anyway. They might have called for help anyway using another method. Causation is genuinely difficult to establish.

International variations:

Different countries regulate health and safety claims differently. Canada's regulatory approach differs from Australia's. Japan has different standards than South Korea. This creates complexity for manufacturers who sell globally. A device complaint that triggers investigation in one country might face no scrutiny in another.

Some manufacturers are preemptively adjusting marketing materials to be more cautious about fall detection claims. They're adding disclaimers, emphasizing that it's not a substitute for professional medical devices, and being more specific about use cases and limitations.

What Happens When Fall Detection Triggers a False Alarm?

False alarms seem annoying. They're actually a much bigger problem than most users realize. The costs are distributed across multiple parties, and they compound quickly.

Emergency responder burden:

When a smartwatch calls 911 with a false fall alert, emergency dispatch has to treat it as a real emergency. They send paramedics or police to the location. This ties up emergency resources. In some cities, emergency services are already stretched thin. A fleet of smartwatch false alarms diverts resources from actual emergencies.

Some areas have already documented increases in false fall alerts correlated with smartwatch adoption. Emergency dispatch centers are tracking this and asking questions.

User experience and feature abandonment:

When you experience your third false fall alert in a week, you turn off the feature. You just don't trust it anymore. And now, the device that was supposed to protect you has become useless for that purpose.

This is the silent failure mode. No lawsuit will find this out easily. But widespread feature abandonment among elderly users—the people who needed it most—is a real problem.

Privacy and data concerns:

Each fall detection alert, real or false, sends your location data to emergency services and potentially to emergency contacts. That's location tracking at scale. If you have 100 false alarms per month from a buggy algorithm, you've transmitted your location 100 times.

Users might not realize they're being tracked this extensively. The privacy implications are concerning, especially for people who enable fall detection and expect it to be discreet.

Liability exposure for manufacturers:

From the manufacturer's perspective, false alarms are a serious problem. If your smartwatch calls 911 on someone's behalf, and that person is embarrassed, harassed, or charged with filing false reports, could they sue the manufacturer?

Some users have actually been charged with making false emergency calls because their smartwatch repeatedly triggered false alarms. This is unconscionable and creates potential liability for the device maker who sold them the watch.

Cascading failures:

Once emergency responders arrive and find no emergency, they still have to document the incident and file a report. In some jurisdictions, repeat false alarms trigger financial penalties. Some fire departments charge response fees for confirmed false alarms. Users can actually be billed money because their smartwatch malfunctioned.

This creates a vicious cycle: watch triggers false alarm > emergency responders arrive > user might be charged > user disables feature > real falls won't be detected.

Estimated data suggests that fall detection accuracy varies across smartwatch models, with some performing better than others. This variability is central to legal disputes over advertising claims.

Comparing Fall Detection to Actual Medical Alert Systems

This is crucial context. Smartwatch fall detection isn't competing with nothing. It's competing with—or positioned as a replacement for—actual medical alert systems. And the comparison reveals how far smartwatch technology still has to go.

Traditional wearable medical alert devices:

Companies like Life Alert, Medical Guardian, and Philips Lifeline manufacture actual fall detection systems designed specifically for elderly and mobility-limited users. These devices are classified as medical devices. They've undergone rigorous testing. They have documented accuracy rates. They're monitored by companies with 24/7 human staff.

These systems cost money—typically

Accuracy comparison:

Dedicated medical alert devices typically achieve 85-95% sensitivity (detecting real falls) and 95-98% specificity (not triggering false alarms). Smartwatch fall detection achieves 70-85% sensitivity with higher false alarm rates.

For people whose lives depend on reliable fall detection, that difference is meaningful.

Response time:

Medical alert systems are monitored by trained staff. When a fall is detected, a person answers the call. They ask if you need help. They can determine if it's a real emergency or a false alarm. If you don't respond, they contact emergency services and provide context.

Smartwatch fall detection is automated. If you don't dismiss the alert, it automatically calls 911 with no human verification. This is faster but less accurate.

Cost and accessibility:

Smartwatch fall detection is free (you've already paid for the watch). Medical alert systems require monthly subscriptions. This is why smartwatches are attractive—they democratize fall detection. But the trade-off is reduced reliability.

For people who can't afford medical alert systems, smartwatches with fall detection are better than nothing. For people who can afford dedicated systems, those systems are probably more reliable.

The cannibalization question:

Smartwatch makers are essentially marketing fall detection as a feature that could reduce the market for dedicated medical alert systems. Some of the litigation might be driven by medical alert companies seeing their market shrink. But the substantive issue—that smartwatch fall detection isn't as reliable—remains valid regardless of motive.

The User Experience Problem: Trust Erosion

Beyond legal and technical issues, there's a trust problem. Users buy smartwatches with fall detection expecting a certain level of reliability. When the feature fails or produces false alarms, that trust erodes.

Initial expectations vs. reality:

Marketing materials suggest that fall detection is a solved problem. "Advanced fall detection." "Automatic emergency calls." "Stay safe with technology." These phrases set expectations. Reality doesn't match.

Users report discovering limitations through experience, not through careful reading of technical specifications. They expect it to work in all fall scenarios and are surprised when it doesn't work for falls in certain positions or certain environments.

The notification fatigue problem:

Users who experience multiple false alarms develop notification fatigue. They stop responding to alerts because they've learned it's probably false. This is dangerous psychology. They might ignore a real fall alert because they've trained themselves to ignore smartwatch alerts.

Notification fatigue is a known problem in security and safety systems. It's well-documented in academic research. Smartwatch makers understand this but struggle to fix it because they're caught between the trade-offs we discussed earlier.

Comparison with other smartwatch features:

Other smartwatch features like heart rate monitoring, step counting, and sleep tracking are imperfect too. But people don't rely on them for safety. If your step count is off by 10%, who cares? If your fall detection is off by 10%, someone might not get help when they need it.

This difference in consequence drives higher expectations for fall detection than for other features.

User research findings:

Surveys of smartwatch owners reveal low confidence in fall detection. Most users don't actually rely on it as a safety mechanism. They view it as a "nice to have" feature, not something they trust with their physical safety. This suggests marketing claims haven't translated into actual user trust or adoption.

For a feature that's heavily marketed as a safety tool, this low trust is a failure.

Fall detection accuracy is significantly impacted by accelerometer limitations, sensor mounting, and environmental and physiological variability. Estimated data based on typical challenges.

What's Likely to Happen: Predictions for 2025 and Beyond

The fall detection lawsuit landscape is still developing. Here's what's likely to happen based on current trends.

Regulatory clarification:

The FDA will likely issue guidance on whether fall detection is a medical device function. This could go either way, but I'd predict that fall detection features on consumer smartwatches won't be classified as requiring full medical device approval. Instead, the FDA will likely create a middle ground: companies must provide documented accuracy data and not make claims they can't support.

This doesn't require clinical trials, but it requires honest testing and transparent communication of limitations.

Marketing language changes:

Smartwatch makers will almost certainly become more cautious about fall detection claims. Instead of "fall detection," you'll see language like "fall detection candidate" or "potential fall notification." Disclaimers will be more prominent.

These changes might happen through litigation settlement agreements, through FDA guidance, or simply through manufacturers being preemptive about legal risk.

Technology improvements:

There's genuine research happening to improve fall detection. Multi-modal sensor fusion (combining accelerometer, gyroscope, barometer, and other sensors) shows promise. Integration with other data (heart rate changes, sudden stillness, audio cues) could reduce false alarms.

But these improvements are incremental, not revolutionary. We won't see fall detection accuracy jump from 75% to 95%. We'll see gradual improvements from 75% to 80% to 85% over several years.

Market bifurcation:

The market might split. Premium smartwatches will offer more sophisticated fall detection with higher accuracy. Budget smartwatches will either drop the feature or offer a more basic version with clear limitations.

Users will learn that fall detection quality varies by device, similar to how camera quality varies by price point. This is actually more honest than current marketing suggests.

Integration with other systems:

Smartwatch fall detection might become more useful when integrated with home systems. If your smartwatch detects a fall and your smart home system confirms you haven't moved in 30 seconds (using other sensors), the combined signal is much stronger than the smartwatch alone.

This multi-layer verification could dramatically improve reliability. It also makes the smartwatch part of a broader ecosystem rather than a standalone safety device.

Regulatory requirements for elderly users:

Some regulators might create specific rules for devices marketed to elderly users. If you're advertising fall detection as a feature for people over 65, you might need to show specific testing with that demographic.

This could actually drive better innovation because manufacturers would be incentivized to understand elderly fall patterns specifically.

The Hidden Costs Nobody's Talking About

Beyond the obvious litigation and regulatory issues, there are costs that don't show up in lawsuits but are real and growing.

Emergency service strain:

If smartwatch adoption reaches 50% of the population and false alarm rates are 5%, that's potentially millions of false emergency calls per year. Some fire departments have already expressed concern about this. A few jurisdictions have started tracking smartwatch-related false alarms separately.

This isn't just a nuisance. Emergency response capacity is finite. In some cities, delays in emergency response to real emergencies are already measured in minutes. Adding smartwatch false alarms makes this worse.

User safety through non-use:

When people disable fall detection due to false alarms, they lose whatever protection it might have provided. This is a real safety cost that's hard to quantify but genuinely concerning.

An elderly person with reliable fall detection capability is safer than one without it. An elderly person with unreliable fall detection that they've disabled is back to baseline safety. But they might feel like they've done something to protect themselves, creating a false sense of security.

Insurance and liability implications:

As fall detection litigation develops, insurance companies will have to reassess risk. If you're an elderly person using smartwatch fall detection, does that reduce your insurance risk? Or increase it (because you might delay other interventions)?

These questions could have real impacts on insurance pricing. They could also affect liability determinations—if someone had a smartwatch, did they use fall detection? Why not? Did they know about the limitations?

Data collection and monetization:

Every fall detection alert—real or false—represents data about your location, activity level, and health status. Manufacturers collect this data. They might use it to improve their algorithms, sell it to insurers, or use it for other purposes.

Fall detection becomes a data collection mechanism disguised as a safety feature. The privacy implications are substantial and mostly unexamined.

How to Evaluate Fall Detection Claims: A Consumer Guide

If you're considering buying a smartwatch with fall detection, or if you already own one, here's how to actually evaluate whether it's useful for your situation.

Ask specific questions:

Don't ask "does this watch detect falls." Ask "what fall scenarios has this watch been tested on? What's the documented accuracy rate? What population was tested (age, mobility level, activity level)?"

Better yet, find independent testing data. Some researchers and tech reviewers have tested smartwatch fall detection. Their results are more credible than manufacturer claims.

Check the notification behavior:

Understand how the watch responds to a detected fall. Is it instant or delayed? Does it give you a chance to dismiss it? Does it contact emergency services automatically after a timeout?

Different watches behave differently, and this affects practical utility. A watch that waits 60 seconds before calling emergency services gives you time to respond if you're able to. One that calls immediately is faster but less accurate.

Look at false alarm reports:

Find user reviews that specifically mention false alarms. If a smartwatch consistently triggers false alarms during exercise, and you exercise regularly, that watch isn't a good fit for you.

Be skeptical of reviews that don't mention false alarms at all. Either the reviewer's use case doesn't trigger them, or the reviewer isn't looking carefully enough.

Consider your actual risk profile:

Fall detection is most valuable for elderly people, people with mobility issues, and people living alone. If you're young and healthy and living with other people, fall detection adds little value. The false alarms are pure downside.

If you're elderly or isolated, fall detection has more value, but you should supplement it with other measures—like a dedicated medical alert system—rather than relying on smartwatch fall detection alone.

Test it yourself:

If you're concerned about fall detection reliability, do controlled tests. Simulate falls in safe ways. See whether the watch detects them. Get a feel for the notification delay and false alarm rate.

You won't test all scenarios, but you'll get practical knowledge about how the system behaves in your environment.

The Broader Implications: When Marketing Exceeds Technology

Fall detection lawsuits aren't just about fall detection. They're a proxy for a larger problem in consumer technology: aggressive marketing for features that don't quite work.

The pattern in smartwatch marketing:

Smartwatch makers constantly push features beyond what the underlying technology can reliably deliver. Sleep tracking is famously unreliable. Heart rate monitoring drifts. GPS navigation gets confused. But these features are marketed confidently anyway.

Fall detection is just the most serious example because the stakes are higher. A wrong sleep score is irritating. A failed fall detection could mean serious injury or death.

Why manufacturers do this:

Competition drives marketing escalation. If one company claims fall detection, competitors must claim it too or risk losing market share. Feature lists have to grow to justify annual price increases. Incrementally better technology is marketed as revolutionary change.

This competitive dynamic creates incentives to overstate capability and understate limitations.

What needs to change:

Regulators need to hold manufacturers accountable for health-related claims. Companies should be required to provide documented accuracy data for features like fall detection. Marketing materials should be consistent with technical capabilities.

This might reduce the rate of feature releases. It might slow innovation in less critical areas. But it would increase consumer trust and reduce litigation.

The long-term industry response:

I expect smartwatch makers will eventually separate health features from fitness features in their marketing. Fitness features (step counting, workout detection) will remain loosely regulated. Health features (fall detection, heart rate monitoring for arrhythmia detection) will face higher standards.

This separation makes sense. A 5% error in step counting affects nobody. A 5% error in fall detection could be serious.

FAQ

What is fall detection and why do smartwatches include it?

Fall detection is a feature designed to automatically identify when a person has fallen and alert emergency services or emergency contacts. Smartwatches include this feature by using accelerometers to sense rapid downward acceleration followed by impact, attempting to distinguish between genuine falls and normal movement. The feature is marketed as a safety tool, particularly for elderly users or people with mobility challenges who might not be able to call for help themselves.

How does smartwatch fall detection actually work?

Smartwatch fall detection uses an accelerometer (and sometimes a gyroscope) to continuously monitor motion and detect patterns consistent with a fall—typically rapid downward acceleration followed by a sudden stop. When the watch detects a potential fall, it displays a notification on your screen asking if you need help. If you don't respond or explicitly request help within 30-60 seconds, the watch automatically calls emergency services and shares your location. The system relies on machine learning algorithms trained on real fall data to distinguish genuine falls from normal activities.

Why are people suing smartwatch makers over fall detection?

Lawsuits target smartwatch manufacturers for allegedly making false advertising claims about fall detection accuracy and reliability. Plaintiffs argue that marketing materials overstated how well these features work and that real-world performance falls short of promised capability. Cases focus on scenarios where fall detection failed to trigger for genuine falls or triggered false alarms during normal activities, suggesting the technology isn't as advanced as claimed.

What are the main limitations of smartwatch fall detection?

Smartwatch fall detection has several fundamental limitations: accelerometers can't see what's happening, only sense motion; the wrist-mounted position doesn't directly measure body motion during a fall; falls vary widely (stumbling vs. dropping, falling onto different surfaces, falling while in different positions); algorithms must balance between catching real falls and avoiding false alarms, creating inherent trade-offs; and the technology hasn't been validated across diverse populations and fall scenarios the way medical devices are tested.

How does smartwatch fall detection compare to dedicated medical alert devices?

Dedicated medical alert systems achieved 85-95% accuracy in detecting real falls and have extremely low false alarm rates. They're monitored by human staff who verify if a fall is real before dispatching emergency services. Smartwatch fall detection achieves 70-85% accuracy and is fully automated, meaning false alarms are common. Medical alert systems are more expensive (typically $25-40/month) but specifically designed for fall detection. Smartwatch fall detection is free but less reliable and should be considered supplementary, not a replacement for dedicated systems.

What is the current regulatory status of smartwatch fall detection?

In the United States, the FDA hasn't classified smartwatch fall detection as requiring medical device approval, treating it as a consumer convenience feature instead. However, regulatory pressure is building, and the FDA is expected to provide clearer guidance in 2025 or later. The European Union has stricter requirements for health claims, and various countries are questioning whether fall detection marketing overstates capability. Regulators may eventually require manufacturers to provide documented accuracy data or impose restrictions on how these features are marketed.

What happens when a smartwatch falsely triggers a fall alert?

When a smartwatch incorrectly detects a fall, it contacts emergency services, requiring paramedics or police to respond. This ties up emergency resources, wastes responder time, and creates documentation burden on dispatch centers. Users may be charged response fees in some jurisdictions. Repeated false alarms lead many users to disable fall detection entirely, eliminating any protection it might have provided. Some users have been charged with filing false emergency reports due to smartwatch false alarms, creating potential liability for device manufacturers.

Should I rely on smartwatch fall detection as my primary safety tool?

No. Smartwatch fall detection should be considered supplementary to other safety measures, not your primary protection. If fall detection is critical to your safety due to age or mobility challenges, combine it with other approaches: living arrangements where other people are nearby, a dedicated medical alert system, home safety modifications, regular check-ins with family or friends, and open communication about what types of falls your smartwatch can reliably detect. The technology isn't mature enough to be a sole source of protection.

How accurate is fall detection for elderly users specifically?

Fall detection accuracy varies by device, but studies show it's generally lower for elderly users than for younger, more active users. Elderly people often experience slower, stumbling falls rather than sudden drops, and they may fall from lower heights (from sitting or lying down), both of which are harder for smartwatch sensors to detect. Elderly users also report higher false alarm rates during normal activities. This is particularly problematic because elderly users are the population for whom fall detection is most marketed and most important.

What should I do if I own a smartwatch with fall detection?

Understand the specific capabilities and limitations of your device by reading technical documentation and testing it in safe scenarios. Don't assume it will catch all falls or that it's 100% reliable. If you're relying on fall detection for actual safety (due to age, mobility, or living situation), supplement it with additional measures like a dedicated medical alert system. Be aware of false alarm patterns specific to your activities and adjust notification settings accordingly. Regularly verify that fall detection is still enabled if it's important to you, and check that emergency contact information is current and correct.

Conclusion: The Smartwatch Fall Detection Reckoning

Smartwatch fall detection represents a fascinating collision between marketing ambition and technical reality. Companies have been selling confidence in a feature that's inherently uncertain. Now they're facing legal consequences for that gap.

The lawsuits are about more than money. They're about the question of what happens when you market a safety feature that doesn't quite work. They're about emergency services strain from false alarms. They're about elderly people relying on technology that might fail them when they need it most.

The technical reality is this: fall detection is harder than it looks. Humans can watch someone fall and instantly know what happened. Accelerometers and algorithms can't. There's no engineering solution to that fundamental information gap. All smartwatch makers can do is improve the probability that their algorithms get it right most of the time. And they have, somewhat. But probability isn't certainty, and certainty is what safety requires.

What's likely to happen next? Regulatory clarification will force more honest marketing. Technology will gradually improve. Insurance companies and emergency services will push back on false alarms. The market will bifurcate, with premium devices offering better fall detection and budget devices dropping the feature or offering a more limited version.

For users, the lesson is simple: don't assume your smartwatch fall detection is a safety system. Treat it as a feature that might help in some scenarios but could fail when you need it most. If fall detection is genuinely important to your safety, supplement it with dedicated medical alert systems and other protective measures. And for smartwatch makers, the lesson is equally clear: marketing should match capability. Claiming you've solved fall detection when you've actually solved 70-80% of it creates liability and erodes trust.

The smartwatch fall detection controversy isn't the end of the story. It's a preview of what happens when consumer tech companies make health-related claims without proportional evidence or accountability. More lawsuits are coming. More regulatory scrutiny is coming. And honestly, that's probably appropriate. Safety features shouldn't be sold with false confidence.

The good news is that fall detection will improve. Companies are investing in better sensors, better algorithms, and multi-modal signal fusion. Within 5-10 years, we might see smartwatch fall detection that's genuinely reliable enough to trust. But that's a few years away, and we're not there yet. Don't pretend we are, and don't buy a smartwatch expecting fall detection to protect you.

It's a useful feature. Just not a reliable one. And there's a big difference.

Key Takeaways

- Fall detection lawsuits allege that smartwatch manufacturers overstate accuracy and reliability of features that can't distinguish all fall types

- Smartwatch fall detection achieves 70-85% accuracy compared to 85-95% for dedicated medical alert systems, making them supplementary, not primary safety tools

- False alarms create cascading problems: emergency responder burden, user frustration leading to feature disablement, and potential liability for manufacturers

- Technical limitations are fundamental—accelerometers can't see context, and algorithms must choose between missing real falls or triggering false alarms

- Regulatory agencies will likely require manufacturers to provide documented accuracy data and be more cautious about health-related marketing claims by 2026

![Smartwatch Fall Detection Lawsuits: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/smartwatch-fall-detection-lawsuits-what-you-need-to-know-202/image-1-1768829935886.jpg)