Introduction: When Silicon Valley Wants a Seat at the Table

Silicon Valley doesn't just make products anymore. It makes presidents. Or tries to.

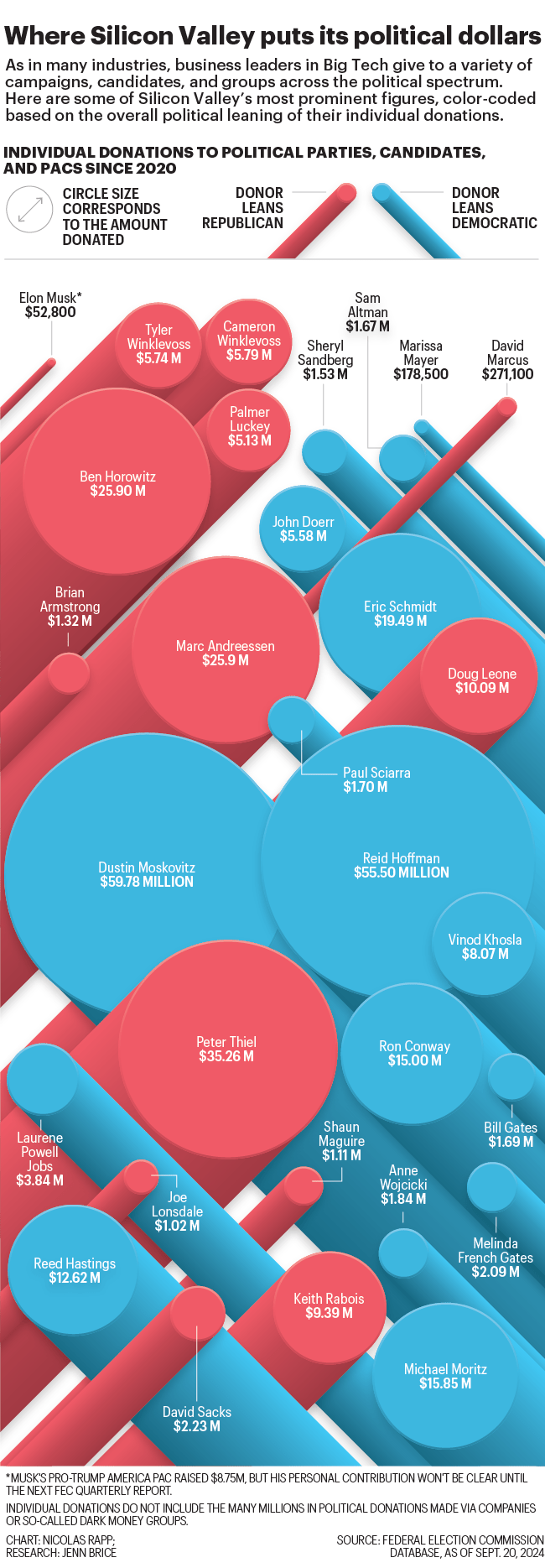

That's not hyperbole. Over the past decade, tech billionaires and venture capitalists have become kingmakers in American politics, wielding influence that extends far beyond campaign donations. They shape policy priorities, veto candidates' staffing choices, and demand concessions in exchange for their financial support. The relationship between the Democratic Party and Big Tech has grown so intertwined that it's become nearly impossible to distinguish where Silicon Valley's interests end and the party's platform begins.

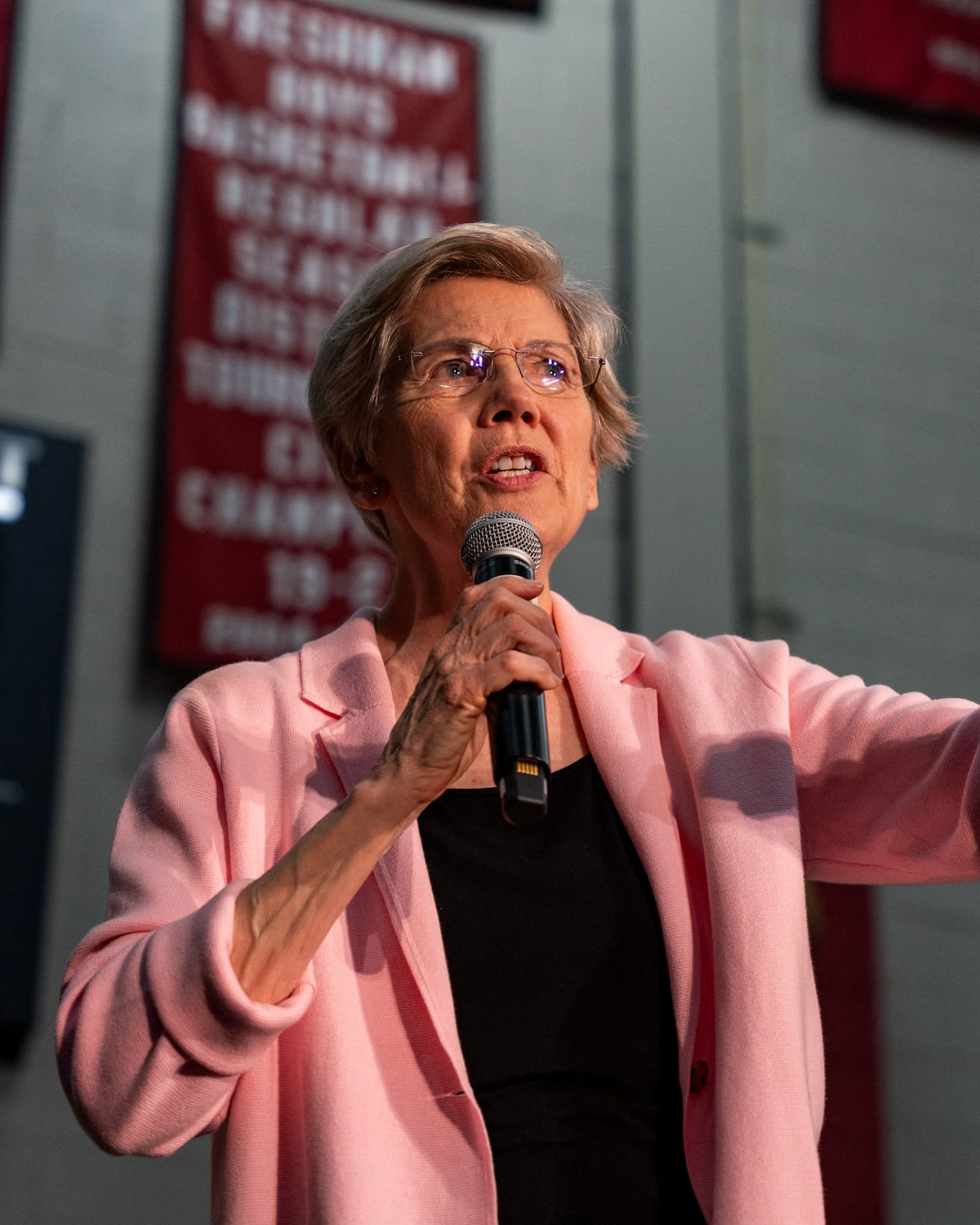

Senator Elizabeth Warren sees a problem here. A big one.

In a speech delivered at the National Press Club in Washington, DC, Warren laid down a challenge to her fellow Democrats: either you rebuild trust with working people by standing up to corporate power and wealthy donors, or you accept permanent minority status. She didn't mince words. She called out specific names, specific incidents, and specific moments when Democratic leadership chose the comfort of wealthy benefactors over the needs of ordinary Americans. This was highlighted in a report by NBC News.

This isn't about campaign finance in the abstract sense. This is about the actual mechanics of political power: who gets to decide what Democrats run on, who gets fired when they become inconvenient, and whether the party's platform reflects what's good for working families or what's good for tech executives' bottom lines.

Warren's argument cuts to something much deeper than standard political discourse. She's not just critiquing Democratic strategy. She's questioning the entire framework that's developed where accepting a tech mogul's policy preferences has become a prerequisite for Democratic funding. And she's suggesting that this framework is precisely why Democrats lost in 2024, as analyzed in The Nation.

This tension between populist economics and billionaire influence defines modern Democratic politics. Understanding how we got here, why it matters, and what might happen next requires looking at the actual power dynamics at play, the specific moments that illustrate the problem, and the fundamental question: can a party funded by the ultra-wealthy ever truly represent working people?

TL; DR

- Tech moguls have become kingmakers: Warren argues Democratic reliance on Silicon Valley donors compromises working-class priorities

- Specific pressure campaigns changed appointments: Reid Hoffman lobbied to remove FTC Chair Lina Khan over consumer protection policies, as noted in The New York Times.

- Corporate accountability creates donor conflict: Progressive enforcement against corporate abuses alienates wealthy benefactors

- Trust requires taking unpopular stances: Democrats must prioritize working people even when it offends their richest supporters

- 2024 losses signal strategic failure: Warren frames the party's defeat as a consequence of abandoning populist economics

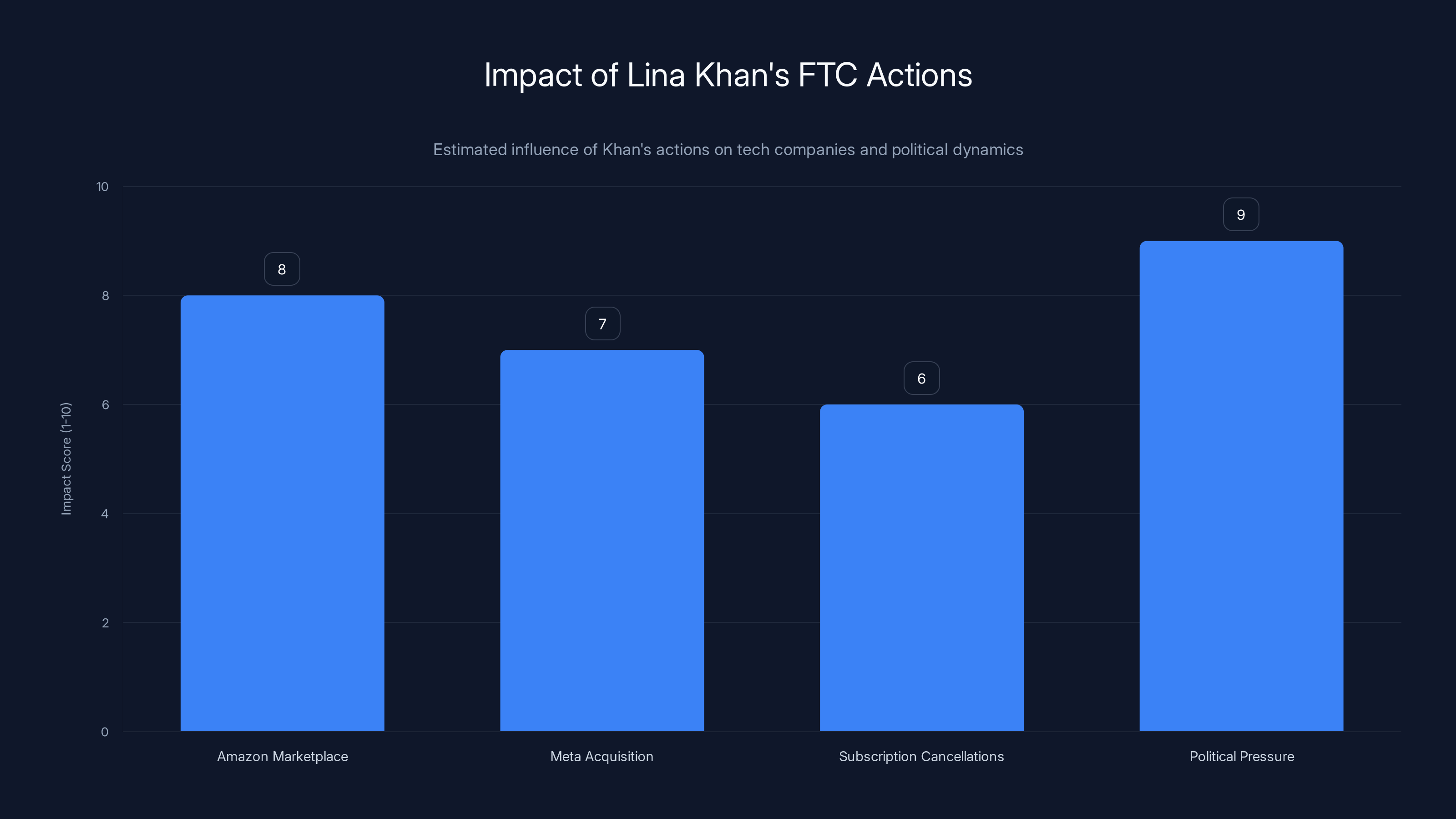

Lina Khan's regulatory actions significantly impacted tech companies, leading to increased political pressure. Estimated data.

The Warren Challenge: A Blueprint for Democratic Realignment

Warren's speech functioned as both diagnosis and prescription. She identified a specific disease afflicting the Democratic Party and proposed a radical cure: reject the entire framework of catering to tech billionaires.

The core argument is deceptively simple. Trust gets built through consistent action, not through careful positioning. When the Biden-Harris administration appointed Lina Khan as FTC chair, it sent a signal to working people: we're actually going to hold corporations accountable. Khan's tenure proved transformative. She pursued enforcement actions against companies for unfair subscription cancellation practices, opposed major tech acquisitions on competition grounds, and generally operated from the principle that market concentration and corporate abuse harm ordinary Americans.

But Khan became inconvenient for tech leaders. Reid Hoffman, LinkedIn's co-founder and a major Democratic donor, explicitly lobbied the Harris campaign to replace Khan if Harris won the election. Hoffman's reasoning was straightforward: Khan's aggressive enforcement threatened his interests and those of other tech moguls. Her policies made business harder. They raised costs. They reduced the ability of dominant platforms to operate without regulatory scrutiny.

Warren's point is brutal: when Democrats consider firing an enforcer who fights for consumers because a billionaire donor asks them to, working people notice. They understand what that signals about priorities. It says: "We'll protect corporate interests over your interests if the price is right."

This isn't theoretical damage. This is concrete, measurable betrayal. And it compounds across dozens of similar moments, each one chipping away at working-class willingness to believe that Democratic leadership actually cares about anything except maintaining access to billionaire money.

Warren proposes flipping this entirely. Stop asking what donors want. Start asking what working people need. And be willing to fight for it even when that fight alienates the wealthy and powerful. Because trust, once rebuilt, becomes the most powerful political asset you can own.

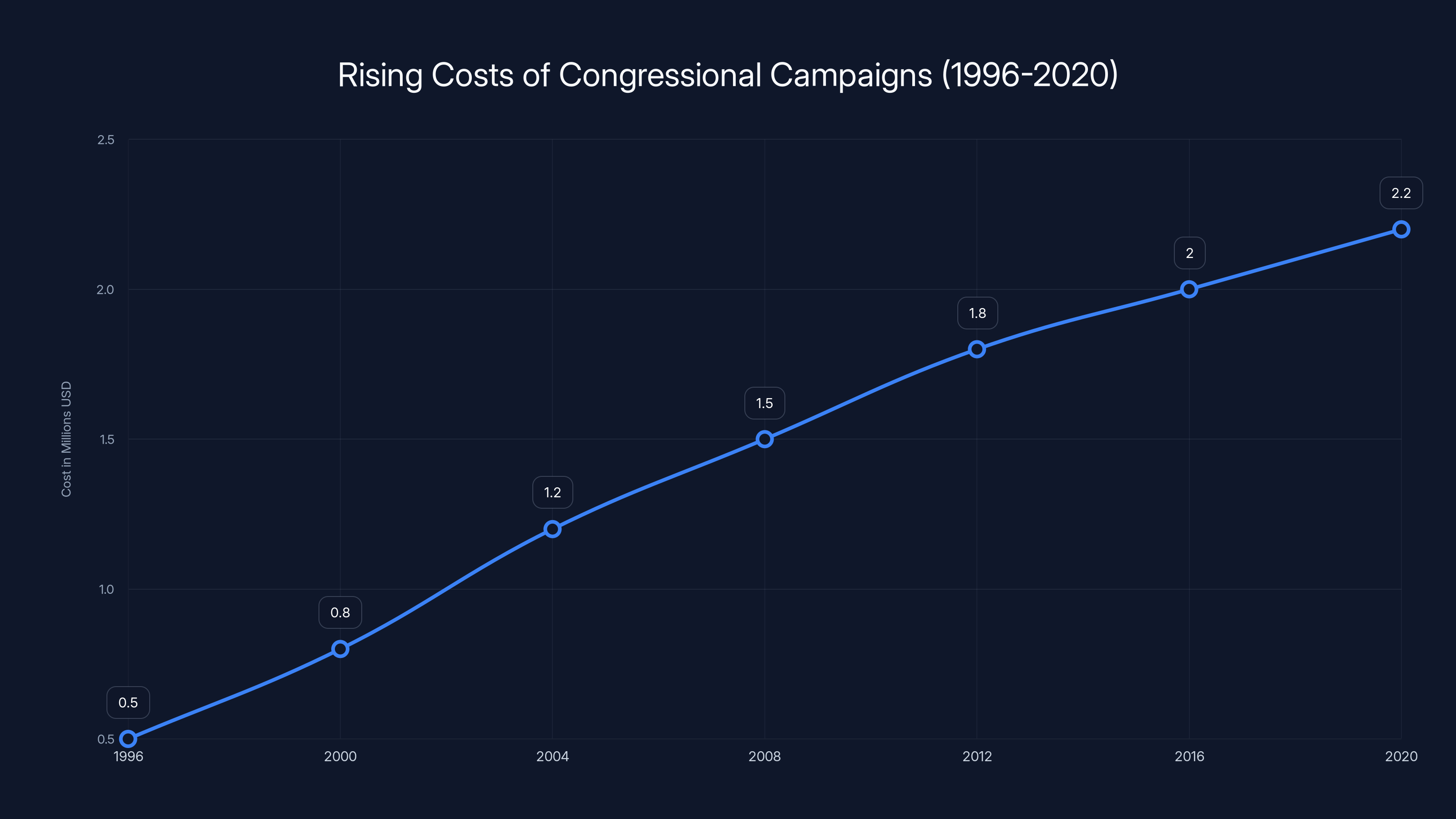

The average cost of Congressional campaigns has increased by 340% from 1996 to 2020, highlighting the growing financial demands of political campaigns.

The Lina Khan Moment: When Donors Became Directors

The Lina Khan situation deserves close examination because it's not some obscure Washington battle. It crystallizes how tech influence actually operates in real time.

Khan, appointed by President Biden in 2021, represented something genuinely new in American regulatory life: an FTC chair who believed that the agency's fundamental purpose was protecting consumers and maintaining competitive markets, not accommodating corporate convenience. She wasn't a radical. She was operating within the FTC's actual statutory mandate. But her approach contrasted sharply with decades of light-touch, industry-friendly regulation that had allowed tech giants to consolidate power with minimal friction.

Khan's concrete actions included pursuing enforcement against Amazon for allegedly abusing its marketplace position, challenging Meta's acquisition of Instagram, and making it dramatically easier for consumers to cancel subscriptions and memberships. Each of these actions generated enormous pushback from tech companies. And with that pushback came pressure on Democratic politicians through donations, media access, and explicit threats about future campaign support.

When Kamala Harris became the presumptive Democratic nominee, these pressures intensified. Reid Hoffman didn't just politely suggest Khan's removal. He made it a condition. The message from major tech donors was clear: if you want our money and our organizational support, Khan goes. She's too aggressive. She's making business harder. Replace her with someone more reasonable.

Warren's critique focuses on what this moment revealed about power dynamics within the Democratic Party. The party had become so dependent on tech billionaire funding that a single donor could effectively direct personnel decisions in a Democratic administration. A sitting FTC chair—someone with statutory independence, someone pursuing legitimate regulatory enforcement—could face removal because a tech executive found her actions inconvenient.

Think about what that signals to voters. If you're a working person paying too-high subscription prices, being locked into auto-renewal traps, or watching Amazon crush local business competition, you've just learned that your party is more responsive to billionaire pressure than to your interests.

The Elon Musk Paradox: When Enemies Become Allies Overnight

Warren also directly called out what she termed the "opportunistic alliance" dynamic with Elon Musk. This deserves unpacking because it illustrates something even broader about how Democratic strategy has warped around tech influence.

Musk spent years as a progressive villain. His union-busting tactics at Tesla, his environmental double-speak, his increasing drift toward far-right politics all made him an obvious target for Democratic criticism. Democrats rightly called him out for these things. But then something changed.

When Musk had a public conflict with Donald Trump, suddenly Democratic strategists saw opportunity. The logic went something like this: Musk is powerful. Musk disagrees with Trump on something. Maybe we can flip him. Maybe we can get his money, his media megaphone, his technical expertise if we just offer him enough. What would it take? What policy concessions would turn Elon Musk into a Democratic supporter?

This is the inverse of the Khan scenario. Instead of removing someone who fights for working people to please a billionaire, Democrats considered offering concessions to a billionaire in exchange for his support. Either way, the operating assumption is identical: the party's first priority is managing billionaire preferences, not advancing working-class interests.

Warren's point is that this is strategically catastrophic. When you're willing to make a deal with someone who's been openly hostile to your values, you signal that those values aren't actually values—they're negotiating positions. You're saying: we'll oppose union-busting if you're on Trump's side. But if you're on our side, union-busting is fine. We're flexible on everything if it helps us win.

Working people understand this too. They see the Democratic Party making arms-deals with Elon Musk and understand that the party's historic commitment to labor rights is contingent, not foundational. It exists only when convenient.

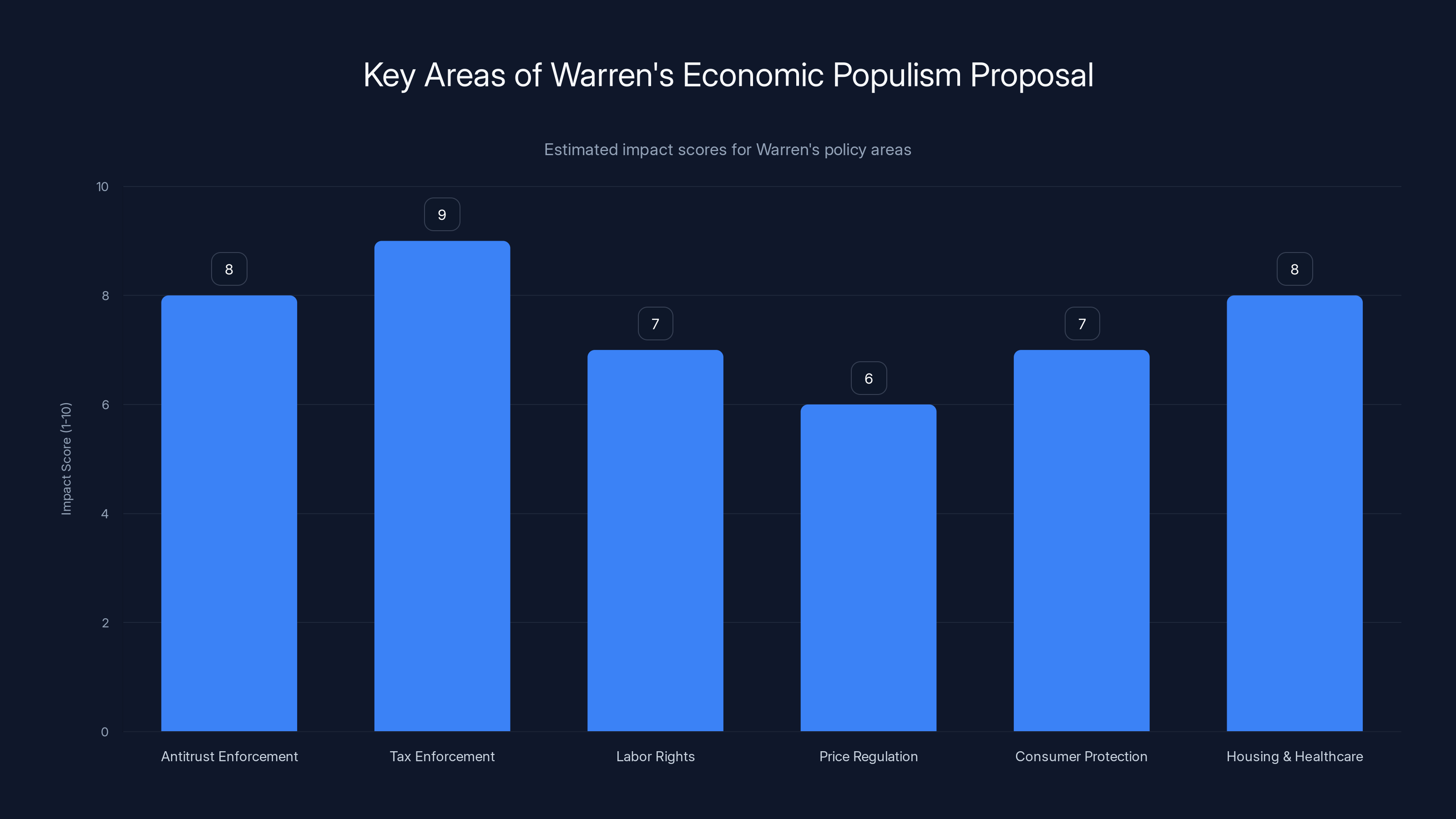

Warren's economic populism proposal emphasizes tax enforcement and antitrust measures, estimated to have the highest impact on improving economic fairness and competition. Estimated data.

Corporate Power and the Tax Fairness Problem

One of Warren's sharpest critiques addresses what she calls staying "silent about abuses of corporate power and tax fairness simply to avoid offending the delicate sensibilities of the already-rich and powerful."

This connects to a genuine crisis in working-class economics. Corporate power has consolidated to extraordinary degrees. Tech companies operate in their own regulatory universe. Amazon avoids billions in taxes while crushing independent retailers. Meta extracts value from billions of users without compensating them. Google's search dominance lets them favor their own services in ways that would once have triggered antitrust action.

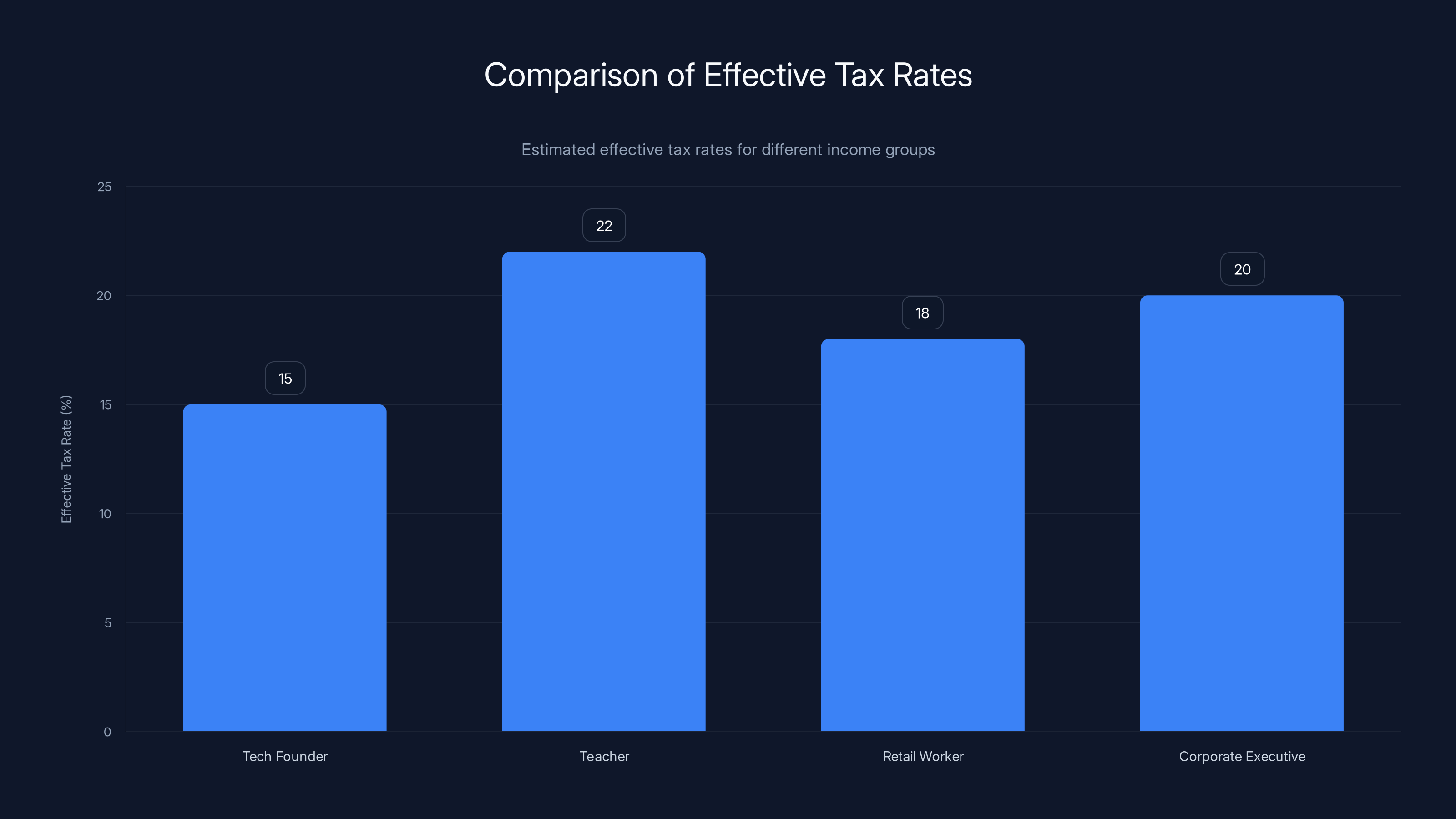

Meanwhile, the tax system allows the ultra-wealthy to pay effective rates far below middle-class workers. A wealthy tech founder might pay 15% on investment income while a teacher pays 22% on wages. The mechanisms for this are complex—capital gains treatment, charitable donation deductions, carried interest loopholes, foreign tax credits—but the outcome is straightforward: the billionaire pays less tax than the teacher.

Democrats have a potentially powerful message here. Tax fairness. Corporate accountability. Enforcement against market abuse. These resonate with working people. They address real economic pain points.

But when party leadership is also asking for donations from the people who benefit from these unfair structures, there's enormous pressure to moderate the message. To soft-pedal. To suggest that really we need "sensible" tax policy and "reasonable" corporate regulation. Words that mean nothing. Words that translate to working people as "we're not going to actually do anything threatening to our donors."

Warren's argument is that this equivocation is worse than useless. It's actively damaging. Because working people can see the contradiction. They understand that you can't simultaneously fight for their economic interests and maintain the friendships of people whose wealth depends on extracting value from them.

The 2024 Loss as Strategic Failure

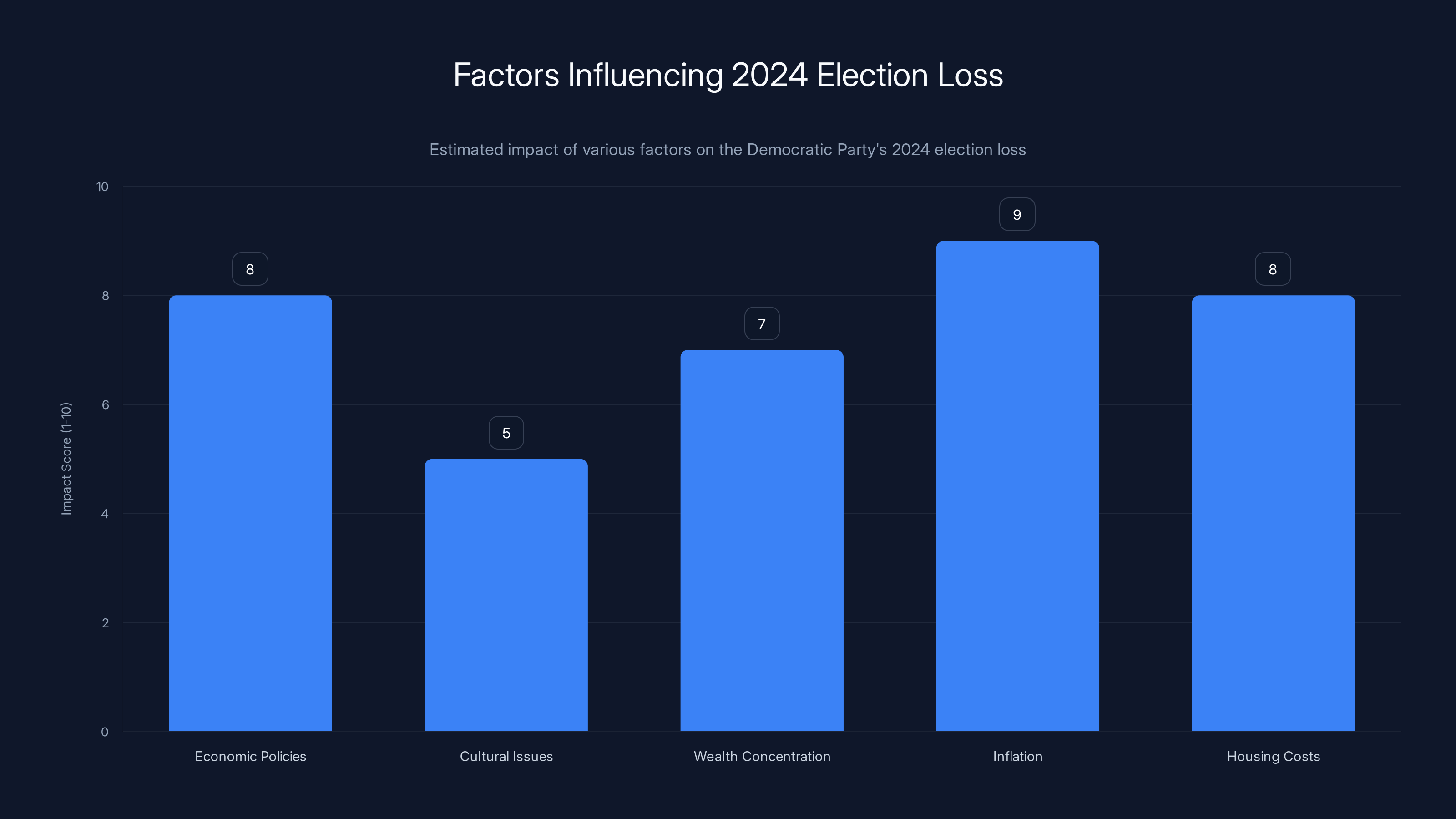

Warren frames the 2024 election loss not as a result of insufficient accommodation to wealthy interests, but as a consequence of abandoning populist economics entirely.

The Democratic Party's polling and demographic data painted a specific picture heading into 2024. Working-class voters—particularly white working-class voters but also voters of color dealing with stagnant wages and rising costs—were abandoning the Democratic Party. The supposed reason was cultural issues. The Democrats were too focused on identity politics. They were out of touch with "real Americans."

But Warren suggests this diagnosis misses the actual problem. The issue wasn't that Democrats talked about racism or gender or LGBTQ+ rights. The issue was that they stopped talking convincingly about economics. They couldn't make a credible case that Democratic leadership would actually fight for working-class economic interests because working people could see that the party was more responsive to billionaire donors than to their own needs.

Consider the specific dynamics. Inflation hit hard in 2021-2023. People were genuinely struggling. Wages weren't keeping up. Housing costs exploded. Childcare became unaffordable. The Democratic administration had some legitimate achievements—the IRA climate investments, negotiating drug prices through Medicare—but the dominant experience for working people was economic distress while billionaire wealth concentrated further.

What would have changed the narrative? Actually fighting for working people. Blocking corporate mergers that reduce competition. Aggressive antitrust enforcement. Tax enforcement against billionaires. Breaking up concentrated tech platforms. Holding CEOs accountable for price-gouging. Aggressive regulation of subscription traps and hidden fees.

But all of these require fighting against powerful interests. And powerful interests are Democratic donors. So the party struggled to do any of it effectively. And working people noticed.

Warren's argument is that this created a death spiral. Every compromise to please donors cost credibility with working people. Every failure to deliver on populist economics cost working-class votes. And the more votes the party lost in working-class areas, the more dependent it became on the remaining voter coalition—which included more wealthy voters. Which meant even more pressure to accommodate billionaire interests. Which meant even less credible messaging about standing up for working people.

The 2024 loss, in this analysis, was the inevitable result. Not because Democrats weren't progressive enough on culture war issues, but because they weren't credible on economics.

Estimated data shows that tech founders often pay lower effective tax rates compared to middle-class workers like teachers, highlighting tax fairness issues.

The Broader Pattern: When Democracy Becomes Pay-to-Play

Warren's critique isn't unique to Democratic-tech mogul relationships, but the concentration of tech wealth and influence does make this particular manifestation especially acute.

Consider how much of the modern political economy flows through a handful of tech billionaires. They own major media platforms. They direct massive campaign donations. They employ thousands of people whose jobs depend on their companies' regulatory relationships with government. They shape the information environment that shapes public opinion. And they have direct access to political leadership that most people don't.

This creates a structural situation where tech billionaire preferences become proxies for what's "realistic" in politics. When someone proposes aggressive tech antitrust enforcement, the response isn't just opposition from the affected companies. It's a broader ecosystem of venture capitalists, tech workers, and other stakeholders raising concerns. It's journalists employed by platforms those billionaires influence reporting skeptically on the proposal. It's talking heads trained in tech's preferred policy frameworks explaining why such enforcement would be counterproductive.

Meanwhile, working people's preferences—for affordable housing, for affordable healthcare, for fair wages, for business competition that benefits consumers—get expressed in polls and surveys but rarely get translated into actual policy priority. Why? Because working people don't have organized mechanisms to pressure political leadership. They don't run major tech platforms. They don't employ thousands. They don't cut million-dollar checks to campaigns.

So they gradually come to understand that their preferences simply don't matter in this system. And when you no longer believe your preferences matter, you stop voting. Or you vote for someone outside the system who at least promises not to pretend otherwise.

This is the actual problem Warren is identifying. Not that tech billionaires are uniquely evil. But that they've accumulated such concentrated power that political outcomes increasingly reflect their interests rather than democratic preferences. And the Democratic Party, which ostensibly stands for democratic values and working-class interests, has become so dependent on their support that it can't effectively oppose them.

The Personnel Appointment Problem: Who Controls the Government?

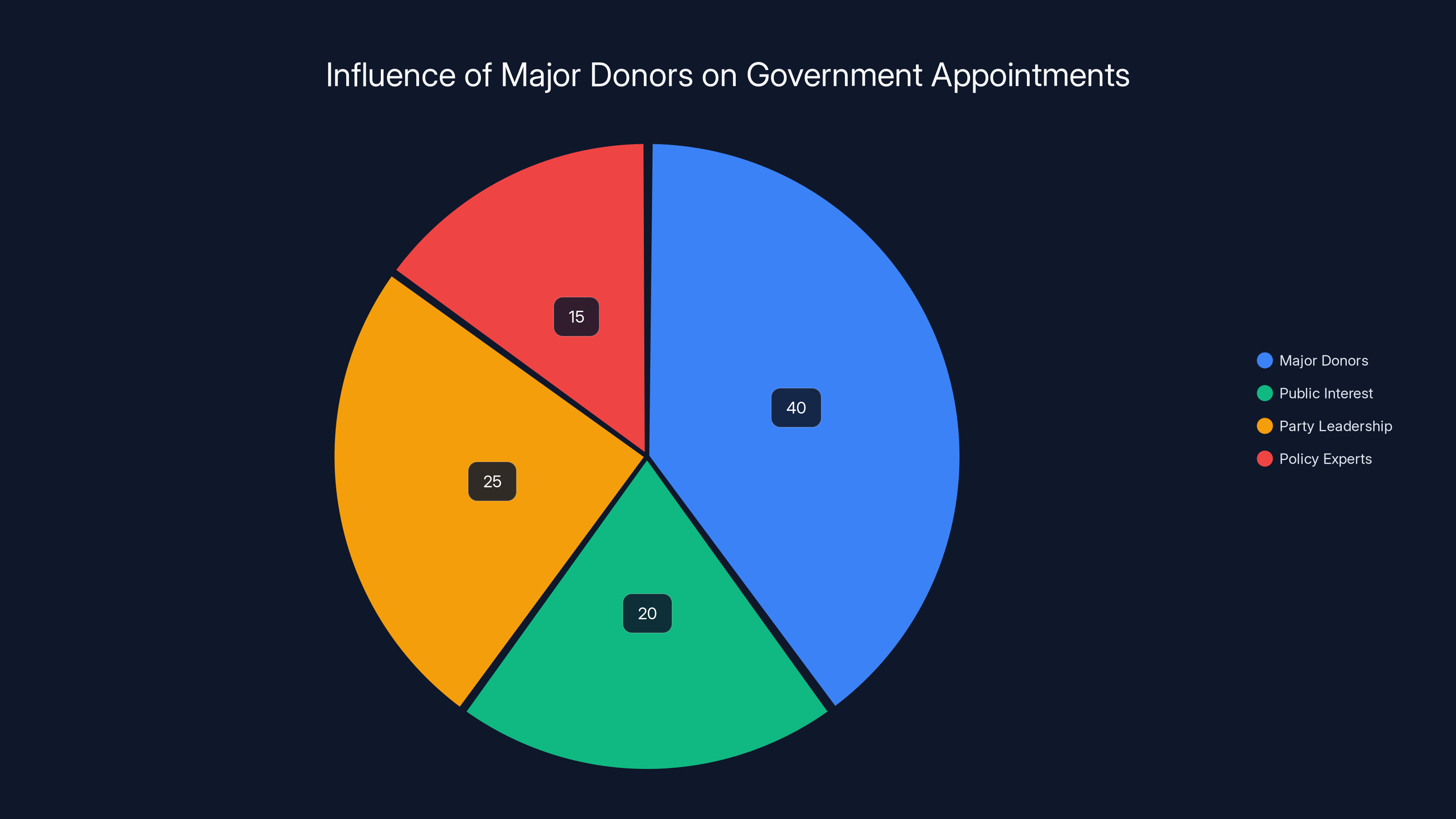

One of Warren's sharpest points involves personnel—specifically, the idea that major campaign donors now effectively control who gets appointed to positions of power.

Historically, major campaign donors expected access, influence, and favorable consideration. But there were limits. A donor couldn't just demand that the party fire a sitting Cabinet member because that donor disliked their policies. That would be too naked. Too obviously corrupt.

But the normalization of billionaire influence has eroded these limits. When Reid Hoffman told the Harris campaign that Khan had to go, he was essentially exercising what used to be considered a patronage power. The power to demand personnel changes in exchange for financial support. The power to veto who gets to serve in the government if you're wealthy enough and connected enough.

This is genuinely dangerous to democratic governance. Because it means that major policy decisions get made not based on what's best for the country or what's mandated by law, but based on what wealthy people prefer. Lina Khan's job security isn't supposed to depend on whether a tech billionaire is happy with her regulatory approach. Her job security is supposed to depend on whether she's executing the FTC's statutory mandate.

But when you're running for president and you need a billion dollars to get there, and tech billionaires have a significant portion of that billion dollars, their personnel preferences effectively become your personnel decisions.

Warren argues that the solution is to reject the entire framework. Don't accept the donation in the first place if it comes with personnel strings attached. Don't promise to fire effective regulators to please donors. Don't accept the premise that winning campaigns requires billionaire support.

This is radical because it's actually radical. Most Democratic politicians have internalized the framework so completely that rejecting it seems unrealistic. But Warren suggests that this acceptance of billionaire kingmaking is itself what's unrealistic—unrealistic as a basis for political credibility and electoral success.

Economic policies and inflation had the highest estimated impact on the Democratic Party's 2024 election loss, overshadowing cultural issues. Estimated data.

Corporate Price-Gouging and the Accountability Gap

One specific issue Warren mentions deserves attention: corporate power and pricing. This became a major economic issue in 2022-2024, as prices rose dramatically for basics like food, housing, and utilities.

The standard explanation was inflation: everyone had extra money, so demand increased, so prices went up. Simple supply and demand. But the actual economics were more complicated. Corporate profit margins expanded significantly. Companies weren't just raising prices to cover higher input costs. They were raising prices beyond that, pocketing the difference as extra profit.

Prices for products as diverse as cereal, beef, airline tickets, and hotel rooms increased well beyond what cost increases would justify. This wasn't coincidental. Companies announced explicitly that they were raising prices to expand profit margins. Wall Street rewarded them for it. Investor presentations celebrated how successfully firms were "passing through" price increases to consumers.

For working people, this represented a real cost-of-living crisis. Groceries cost significantly more. Rent consumed larger shares of income. Childcare became even less affordable.

The Democratic response was oddly muted. They could have made price-gouging a central issue. They could have proposed investigations, enforcement, price controls, or penalties for excessive price increases. They could have made corporate accountability the centerpiece of their economic messaging.

But doing so would have meant offending major corporate donors and the venture capital ecosystem that sees all regulation as dangerous. So instead, the administration suggested that inflation was transitory, that supply chains would fix themselves, that the Federal Reserve's interest rate increases would solve the problem. None of this addressed the actual problem, which was that companies were choosing to expand profit margins.

Working people noticed this failure. They understood that if the Democratic Party actually stood for their interests, corporate price-gouging would be a major political issue. The fact that it wasn't suggested, once again, that the party's first loyalty was to corporate interests, not working-class interests.

This connects back to Warren's fundamental argument. To rebuild trust, you have to actually fight for working people on the issues that matter to their lives. You can't do that credibly while also accepting massive donations from the people whose interests you're fighting against.

The Media Ecosystem Problem: When Donors Control Information

There's a meta-level problem that deserves attention: many of the billionaires exercising influence over Democratic politics also own or control major media platforms. This creates a perverse dynamic where opposition to billionaire interests gets mediated by media they own.

Consider a proposed policy: aggressive antitrust enforcement against Meta. This is reasonable policy, well-supported by evidence that Meta's size and power harm competition and innovation. But Meta's CEO also owns The Washington Post. And the publication of major investigative stories about Meta practices occurs under his editorial direction. There's an inherent conflict of interest.

Or consider tech regulation more broadly. Major tech billionaires fund think tanks, universities, and media outlets that produce research and commentary on tech policy. A study finding that tech regulation is beneficial? Less likely to get funded or prominently featured. A study finding that tech regulation is harmful? Gets promoted extensively.

This creates an ecosystem where certain arguments seem dominant simply because billionaires have funded their promotion. The actual evidence might support different conclusions, but those conclusions don't get the same amplification.

Warren's point is that this distorts democratic deliberation. Working people don't have equivalent media platforms to promote their interests. They don't own major newspapers or television networks. So their perspectives, preferences, and arguments get marginalized not because they're wrong, but because they're not funded by billionaires.

In a healthier democratic system, this wouldn't happen. Diverse viewpoints would compete in a genuinely open marketplace of ideas. But when billionaires own the marketplace, they can tilt the competition in their favor.

Estimated data showing that major donors hold the largest influence (40%) over government appointments, overshadowing public interest and policy experts.

The Economic Populism Alternative: What Warren Actually Proposes

Warren's speech functions as a case for specific economic populism as Democratic strategy. This isn't about cultural issues or abstract values. It's about concrete policies that affect working people's lives and wallets.

What does this look like in practice? Start with antitrust enforcement. Meta shouldn't have been allowed to acquire Instagram and WhatsApp. Amazon shouldn't be allowed to operate a marketplace and compete directly with sellers on that marketplace. Google shouldn't be able to favor its own services in search results. These create monopolies that reduce consumer welfare, kill competition, and concentrate power in ways inconsistent with actually competitive markets.

Second, tax enforcement. The billionaires and large corporations paying less in taxes than middle-class workers is a policy choice, not inevitable. You could increase enforcement against tax avoidance. You could close loopholes. You could increase the capital gains rate. You could implement a wealth tax. These are all policy levers that would improve fairness and fund public investment.

Third, labor rights. Strengthen organizing, union power, and collective bargaining capacity. This directly increases working-class economic power and bargaining ability with employers.

Fourth, price regulation or investigation. In extreme situations where companies are demonstrably price-gouging, you can investigate, penalize, or regulate prices. This is standard in many democracies and has precedent in American history.

Fifth, consumer protection. Make it easier to cancel subscriptions. Require transparent pricing. Prevent hidden fees. Enforce against unfair business practices. This protects ordinary consumers from exploitation.

Sixth, housing and healthcare. Build more housing to address supply constraints. Negotiate drug prices more aggressively. These are the cost-of-living issues that dominate working people's economic lives.

None of these are radical. Most have significant public support. Most would improve working-class economic welfare. But all of them face opposition from wealthy interests who profit from the current system.

Warren's argument is that Democrats should do these things anyway. Because building trust with working people requires actually fighting for their interests. Because you can't be credible as an advocate for working people while simultaneously accepting massive donations from the people whose interests you're fighting against.

The Fundamental Tension: Can You Serve Two Masters?

This gets to the real issue Warren is raising, and it's ultimately a question about political honesty.

The Democratic Party would like to serve both working people and billionaire donors. It would like to get billionaire money while also claiming to stand up against billionaire power. It would like to accept tech mogul donations while also regulating tech companies. It would like to take corporate donations while also fighting corporate exploitation.

But you can't do all of these simultaneously. At some point, interests diverge. Working people want affordable housing, healthcare, and childcare. Tech billionaires want minimal regulation. You can't give both of them what they want. You have to choose.

For decades, the Democratic Party has chosen billionaires. It's accepted their donations, adopted their policy preferences, removed effective regulators who threatened their interests, and softened its economic messaging to avoid offending wealthy donors. And it's done all this while claiming to stand for working people.

Warren is saying this is a false choice. Choose working people. Stop accepting billionaire donations if they come with policy strings. Stop firing regulators because donors demand it. Stop muting economic populism to keep donors happy. Build your coalition on the basis of actually fighting for working-class interests.

Will this cost Democratic funding? Yes, probably. Some tech billionaires will find other candidates to fund. Some venture capitalists will go elsewhere. Some wealthy donors will withhold support.

But Warren argues that this is actually the path to electoral success, not failure. Because trust is more valuable than money. Working people will show up and vote for candidates they believe actually stand for their interests. And there are more working people than billionaires.

This is the crux of her argument: the Democratic Party's recent approach is not just ethically problematic. It's strategically failing. And the solution is not to accommodate billionaires even more, but to reject that framework entirely.

The Structural Problem: Billionaires, Money, and Political Access

Underlying all of Warren's specific critiques is a structural problem: American political campaigns require enormous amounts of money, and billionaires have that money.

Running a competitive presidential campaign costs over a billion dollars. Congressional campaigns cost tens of millions. State races cost millions. All of this money has to come from somewhere. And increasingly, it comes from wealthy individuals and the corporations they control.

This creates an automatic dependency. If you want to run for president, you need billionaire support. If you need billionaire support, you have to be responsive to their preferences. If you're responsive to their preferences, you can't credibly stand up against them on policy.

The most direct solution would be campaign finance reform: public funding of campaigns, limits on individual donations, transparency requirements. But campaign finance reform is opposed by the people who benefit from the current system—billionaires and the politicians they fund. So it doesn't happen.

Instead, you get the system Warren describes: Democrats pretending they're standing up for working people while simultaneously doing what their billionaire donors want. They get billionaire money, which they need to compete. But they pay for it with credibility and actually serving working-class interests.

Warren suggests that rejecting this framework—running campaigns that don't depend on billionaire money, building constituencies based on actual working-class politics rather than billionaire preferences—is not just principally correct, but politically smarter than accommodation.

Whether she's right about this is an empirical question that future elections will test.

The Historical Context: How Democrats Became the Party of Billionaires

This didn't happen overnight. Understanding how the Democratic Party became so dependent on billionaire funding requires looking at the last four decades.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Democrats lost working-class voters, particularly white working-class voters. This was driven by a complex mix of issues: deindustrialization, concerns about crime, federal enforcement of civil rights, and cultural changes. But the fundamental problem was that Democrats were becoming less appealing to working people.

Instead of rebuilding a working-class coalition, Democratic leadership chose a different strategy: build a coalition that included wealthy urban professionals, college-educated voters, minorities, and wealthy business interests that supported Democratic positions on social and environmental issues. This coalition was more stable than a working-class coalition in some ways. Wealthy people vote more reliably. They donate more. They're easier to reach through upscale media.

But this coalition had an inherent problem: wealthy people and working people have different economic interests. Wealthy people benefit from tax cuts, deregulation, and weak labor rights. Working people benefit from the opposite. So to maintain this coalition, Democrats had to mute their economic messaging. They couldn't credibly fight for working-class interests because their coalition included wealthy people whose interests were opposed to those of working people.

This manifested in specific ways. Democrats supported free trade even though it cost working-class manufacturing jobs. They supported financial deregulation even though it contributed to financial crises that hurt working people. They were cautious about challenging corporate power even though that power worked against working-class interests.

Over time, this became the default Democratic strategy. Not because anyone consciously decided to abandon working people. But because the coalition had shifted to include wealthy voters, and maintaining that coalition required modulating economic messaging.

But the problem with this strategy is that you can't win national elections without working-class votes. Without working people showing up and voting for you, you lose even competitive races. And working people aren't going to turn out for a party they don't believe stands for their interests.

Warren's argument is that Democrats need to rebuild that coalition, which means going back to actually fighting for working-class interests. Which means accepting that some wealthy people will exit the coalition. Which means being willing to be opposed by the tech billionaires and corporate interests that have become so influential.

The 2026 Implications: A Test Case for Warren's Strategy

Warren's speech looks to 2026, the midterm elections where Democrats will have a chance to rebuild after 2024's losses.

If Warren is right, Democratic candidates who campaign on credible working-class economic messaging should outperform. Candidates who propose aggressive antitrust enforcement, tax enforcement against billionaires, strong labor policies, and price regulation should do better in working-class districts than candidates offering moderate technocratic policy.

If Warren is wrong, it might be because working-class voters have different primary concerns, or because billionaire-funded campaigns can still win through superior resources and messaging, or because cultural issues really do dominate working-class voting decisions.

2026 will test these hypotheses. We'll see whether Democratic candidates running on economic populism do better or worse than those taking more moderate approaches. We'll see whether aggressive rhetoric against billionaires and corporate power helps or hurts with voters. We'll see whether the base can be mobilized through economic messaging or whether other factors dominate.

But regardless of the specific outcome, Warren has framed the core strategic question for Democrats going forward: do you try to maintain a coalition of wealthy voters and working-class voters with incompatible interests, or do you choose working-class voters and accept that some wealthy voters will be opponents?

This is ultimately a more fundamental question than specific policy platforms. It's about what the Democratic Party is for. Is it a party that aspires to represent working people? Or is it a party that represents a coalition including wealthy interests, and occasionally throws working people a bone to keep them voting?

Warren's argument is that you can't have it both ways anymore. Working people have figured out the game. They see the contradictions. They understand that claims to stand for them while simultaneously accepting billionaire money don't mean anything.

So the choice is genuine: either rebuild as a genuinely working-class party, or accept that working-class voters will defect and build a purely wealthy-professional coalition. And that coalition probably can't win national elections.

The Broader Democracy Question: What Does Democratic Accountability Look Like?

Warren's critique ultimately raises questions that extend beyond Democratic strategy. It's really about democratic governance itself.

In a functional democracy, public policy should reflect the preferences of ordinary citizens. Not perfectly, not constantly, but generally. When policy systematically reflects the preferences of billionaires while ignoring those of ordinary working people, something has gone wrong with democracy.

This doesn't mean that all billionaires are evil or that all wealthy people are self-interested in bad ways. It means that a system where billionaires have vastly more political power than ordinary people is inconsistent with democratic principles.

Democratic accountability requires that elected officials be responsive to the people who elect them. But when elected officials are more dependent on billionaire donations than on working-class votes, the dependency runs the wrong way. They're responsive to billionaires rather than to ordinary people.

Fixing this requires multiple interventions: campaign finance reform to reduce the importance of billionaire money, media regulation to prevent billionaire control of information, antitrust enforcement to prevent economic concentration, and tax policy to reduce billionaire wealth accumulation. These are all contested political issues where billionaires have strong preferences opposed to reform.

But Warren's argument is that democracy itself depends on making progress on these issues. You can't have a functioning democracy where a handful of billionaires exercise veto power over appointments and policy through their financial leverage.

So while her immediate argument is directed at Democratic strategy, the deeper argument is about democracy. And that argument doesn't depend on whether it would help Democrats electorally. It depends on whether it's necessary for democracy to function at all.

The Path Forward: Warren's Implicit Roadmap

Warren doesn't spell out a complete alternative strategy, but her critique suggests some directions.

First: rebuild the party's credibility with working people by actually delivering on working-class economic policies. Push aggressive antitrust enforcement. Enforce taxes against billionaires and large corporations. Strengthen labor rights. Regulate corporate price-gouging. These policies are popular with working people and would genuinely improve their lives.

Second: accept that this will require losing some wealthy donors and wealthy voters. They won't support policies that threaten their interests. But working people will support a party that credibly stands up for their interests. And there are more working people than billionaires.

Third: rebuild the party's economic messaging around populist themes. Make economic inequality, corporate power, and fairness central themes. Talk constantly about how the system is rigged against working people and how Democratic policies will unrig it.

Fourth: reduce campaign dependence on billionaire money. This requires either campaign finance reform or finding alternative funding sources. It probably requires some of both.

Fifth: challenge billionaire control of media and information. Support media regulation, encourage alternative media, invest in party media infrastructure, use the Democratic megaphone to call out billionaire influence on policy.

None of these are easy. All require overcoming entrenched interests and institutional momentum. But Warren argues they're necessary if Democrats want to rebuild trust with working people and win elections.

More fundamentally, she argues they're necessary if the Democratic Party wants to have any claim to representing working people. Because right now, the contradictions between claims and actions are too visible to maintain credibility.

Conclusion: The Stakes of Democratic Realignment

Elizabeth Warren's speech at the National Press Club frames a fundamental choice for the Democratic Party and for American democracy more broadly.

On one level, it's about 2026 strategy. How should Democrats run in a post-2024 environment where working-class voters have defected? Warren argues that the answer is not further accommodation to wealthy interests, but a decisive turn toward economic populism that credibly stands up for working people even when that offends billionaire donors.

But on a deeper level, Warren's argument is about what kind of party Democrats aspire to be. Is it a party that represents working people, or is it a coalition that includes working people alongside wealthy interests? If the former, then billionaire influence and comfortable accommodation to corporate power are incompatible with that mission. If the latter, then Democrats should be honest about what they represent and not claim to stand for working people when they're actually responsive to billionaire preferences.

Warren is essentially saying: choose. Because you can't do both. You can't accept billionaire money while credibly fighting billionaire interests. You can't remove effective regulators to please donors and then claim you're standing up to corporate power. You can't stay silent on corporate abuse because it might offend wealthy supporters and then expect working people to believe you care about fairness.

The political question is whether her diagnosis is correct: whether Democratic losses stem from loss of working-class trust specifically because of visible contradiction between claims and actions. If so, her prescription follows logically. Rebuild credibility by actually fighting for working-class interests, even when that offends billionaires.

The meta question is what this says about American democracy more broadly. If billionaire influence over appointments, policy direction, and political strategy is sufficiently powerful to pull an administration away from its regulatory mission, something fundamental has warped about how democracy works. Fixing that requires confronting billionaire power directly, not accommodating it.

Warren's argument is that the Democratic Party should make that confrontation central to its strategy. Not as a moral statement, but as practical politics. Not because the rich are uniquely evil, but because a party claiming to represent working people can't credibly do so while systematically choosing billionaire interests over working-class interests when they conflict.

Whether she's right about this is something 2026 will help test. But the argument itself deserves to be taken seriously as a challenge to both Democratic strategy and American democratic functioning. Because if a major political party can't stand up to its biggest donors even when doing so would help it achieve its stated mission, what does that say about how much real power ordinary citizens actually have in the system?

FAQ

What is tech billionaire influence on Democratic politics?

Tech billionaire influence refers to the ability of extremely wealthy technology executives and entrepreneurs to shape Democratic Party strategy, policy preferences, and personnel decisions through financial contributions, media control, and political pressure. This influence operates through campaign donations, media ownership, employment relationships, and direct lobbying efforts that make Democratic leaders responsive to billionaire preferences over working-class interests.

How does tech billionaire influence actually operate in practice?

Influence operates through multiple mechanisms: campaign donations create financial dependency, ownership of media platforms shapes information environments, employment by tech companies creates worker constituencies dependent on tech leadership, and direct lobbying makes policy demands explicit. When Democratic leadership faces pressure from a billionaire donor, they often accommodate those preferences rather than risk losing funding, even when accommodation contradicts working-class interests.

Why does Warren argue this harms Democratic electoral performance?

Warren contends that when working people see Democrats responding to billionaire preferences at the expense of working-class interests—firing regulators because donors demand it, softening corporate accountability messaging, accepting tech mogul deals—they correctly understand that the party isn't actually standing up for them. This destroyed working-class trust, leading to defection to Republican candidates. Electoral success requires credible commitment to working-class interests, which is impossible while accepting billionaire influence.

What specific example does Warren use to illustrate billionaire influence?

Warren points to Reid Hoffman's explicit demand that Kamala Harris remove FTC Chair Lina Khan as a condition of his support. Khan had pursued aggressive consumer protection enforcement and competition policy that threatened tech interests. When a major donor could credibly demand removal of a sitting official through implicit threat of withholding financial support, it demonstrated that billionaires had veto power over appointments and policy in Democratic administrations.

What policies would reduce billionaire influence on Democratic politics?

Policies Warren's argument supports include campaign finance reform to reduce dependency on billionaire donations, media regulation to prevent billionaire control of information, antitrust enforcement to break up tech monopolies, tax enforcement to reduce billionaire wealth accumulation, and explicit party decisions to reject billionaire donations that come with policy strings. The underlying principle is reducing the structural power billionaires have over political outcomes.

How would Democrats rebuild working-class trust according to Warren's framework?

Rebuild through credible action on working-class economic issues: aggressive antitrust enforcement against dominant platforms, tax enforcement against billionaires and corporations, strong labor rights and union support, consumer protection against corporate abuse, housing policy to address supply constraints, and healthcare policy to reduce costs. The key is demonstrating through action, not rhetoric, that working-class interests genuinely come first even when that conflicts with billionaire preferences.

Key Takeaways

- Tech billionaires have become kingmakers in Democratic politics through campaign donations and media control, creating conflicts between billionaire interests and working-class interests

- Specific incidents like Reid Hoffman demanding Lina Khan's removal demonstrate how billionaire donors effectively veto appointments and policies that threaten their interests

- Warren argues that accommodation to billionaire preferences destroys Democratic credibility with working-class voters who can see the contradiction between claims and actions

- Democratic electoral losses stem not from insufficient accommodation to wealthy interests, but from loss of working-class trust due to visible prioritization of billionaire preferences

- Rebuilding Democratic strength requires credible economic populism: aggressive antitrust enforcement, tax enforcement, labor rights support, and corporate accountability measures