The Complete History of TiVo: How It Changed Television Forever

There's a moment in television history when everything shifted. Not when color arrived, not when cable exploded, not even when streaming launched. It happened when a company figured out how to let you pause live television.

Sound simple? It wasn't. In 1999, the idea felt like magic. You hit a button, and the broadcast froze. You could skip the commercials. You could rewind the moment you missed. You could set a show to record and actually know it would be there when you wanted it, not scrambled by cable guides or forgotten in some digital void.

That company was TiVo. For a brief, shining moment in the early 2000s, it seemed like everyone had one. Your neighbors had one. Your favorite celebrities had one. The company became so ubiquitous that the product name became a verb—people didn't record shows, they "TiVoed" them. It was the rare tech product that transcended gadget culture and entered actual human conversation.

But here's the brutal irony: almost nobody has a TiVo anymore. The company that fundamentally changed how we consume television, that proved pause buttons and on-demand watching were essential features, that shaped an entire generation's relationship with their screens—that company lost. Completely. Utterly. The world caught up, the technology became commodified, and TiVo never figured out how to stay relevant as everything they pioneered became standard.

This is the story of how one company changed television forever and then got left behind. It's a story about innovation, about the difference between inventing something and building a sustainable business around it, and about how the products that matter most to us are often the ones we forget to credit.

TL; DR

- TiVo invented the DVR and made pausing, rewinding, and recording live TV possible for regular consumers

- Cultural phenomenon: The product became a verb and appeared on major TV shows, with Hollywood celebrities and A-list fans

- Business failure: Despite creating a revolutionary product, TiVo never turned it into a sustainable, profitable business model

- Technology was commodified: Cable boxes added DVR functionality, streaming platforms made recording obsolete, and the features TiVo pioneered became standard

- Legacy is complicated: We all live in the world TiVo imagined, but we do it without TiVo—proving brilliant innovation isn't always rewarded

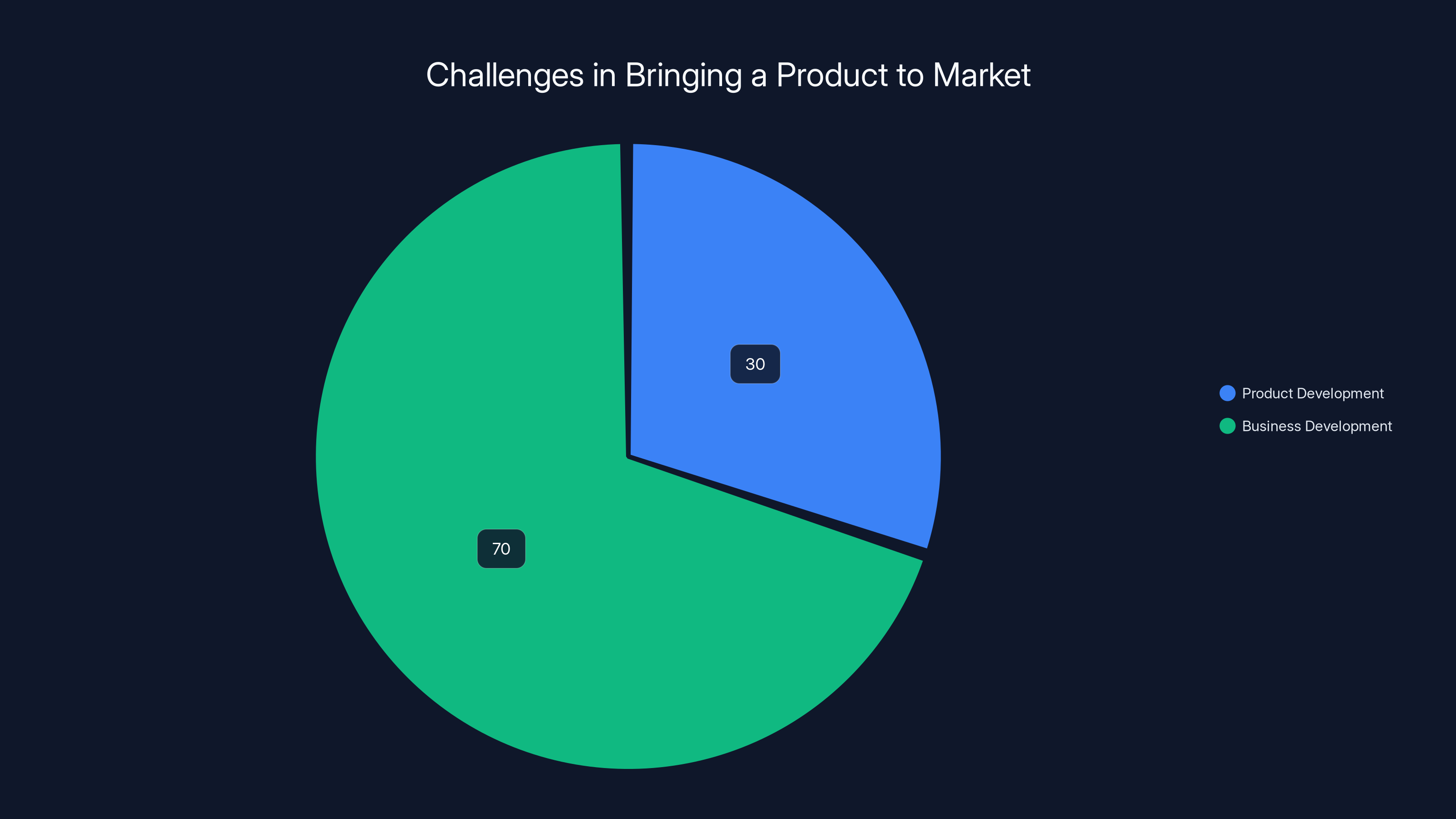

Inventing a product accounts for only 30% of the challenge, while building a business around it represents 70% of the effort. (Estimated data)

The Pre-TiVo World: When Television Controlled You

To understand what TiVo actually did, you need to understand what television was like before it arrived. And I mean really understand it—not just theoretically, but viscerally.

Imagine this: It's 8 PM. Your favorite show starts in five minutes, but you haven't finished dinner. Too bad. You're missing the opening. Or maybe you're stuck in traffic and your show starts in an hour, but you can't record it because your VCR isn't programmed, and you don't know how to program it, and the manual is somewhere in a drawer you'll never find.

Or picture this: You want to watch something at a different time than it airs. Your only option is to hope you can set up your VCR correctly—which involved programming the channel, the start time, the end time, and the duration, and if you got any of those wrong, the recording wouldn't work. Recording something on VCR was a technical skill that required planning, written notes, and genuine anxiety. Get it wrong, and you'd miss the show entirely.

Live television was non-negotiable. If you missed something, it was gone. There was no pausing to grab food. There was no rewinding to catch what you missed. There was no "I'll watch it later." Television owned your schedule, not the other way around.

Cable companies had introduced electronic program guides in the late 1990s, which was an improvement—you could see what was on without a printed TV Guide—but you still couldn't control when things aired. You couldn't skip commercials. You couldn't pause the moment someone said something shocking. You were a passive consumer, and television networks had all the power.

VCRs were supposed to solve this. They'd been around since the 1970s, and technically, they could record anything. But in practice, they were frustrating, error-prone, and required expertise most people didn't have. The "blinking 12:00" on millions of VCRs became a cultural shorthand for consumer technology that was too complicated to use.

There was also the practical problem of physical media. Videotapes took up space. You'd accumulate stacks of them. Organizing them was a nightmare. Finding something you'd recorded three months ago meant digging through your library. And the tapes degraded over time. Something recorded in 1995 probably didn't look great in 2000.

Into this world—this world of passive consumption, clunky technology, and missed shows—stepped TiVo.

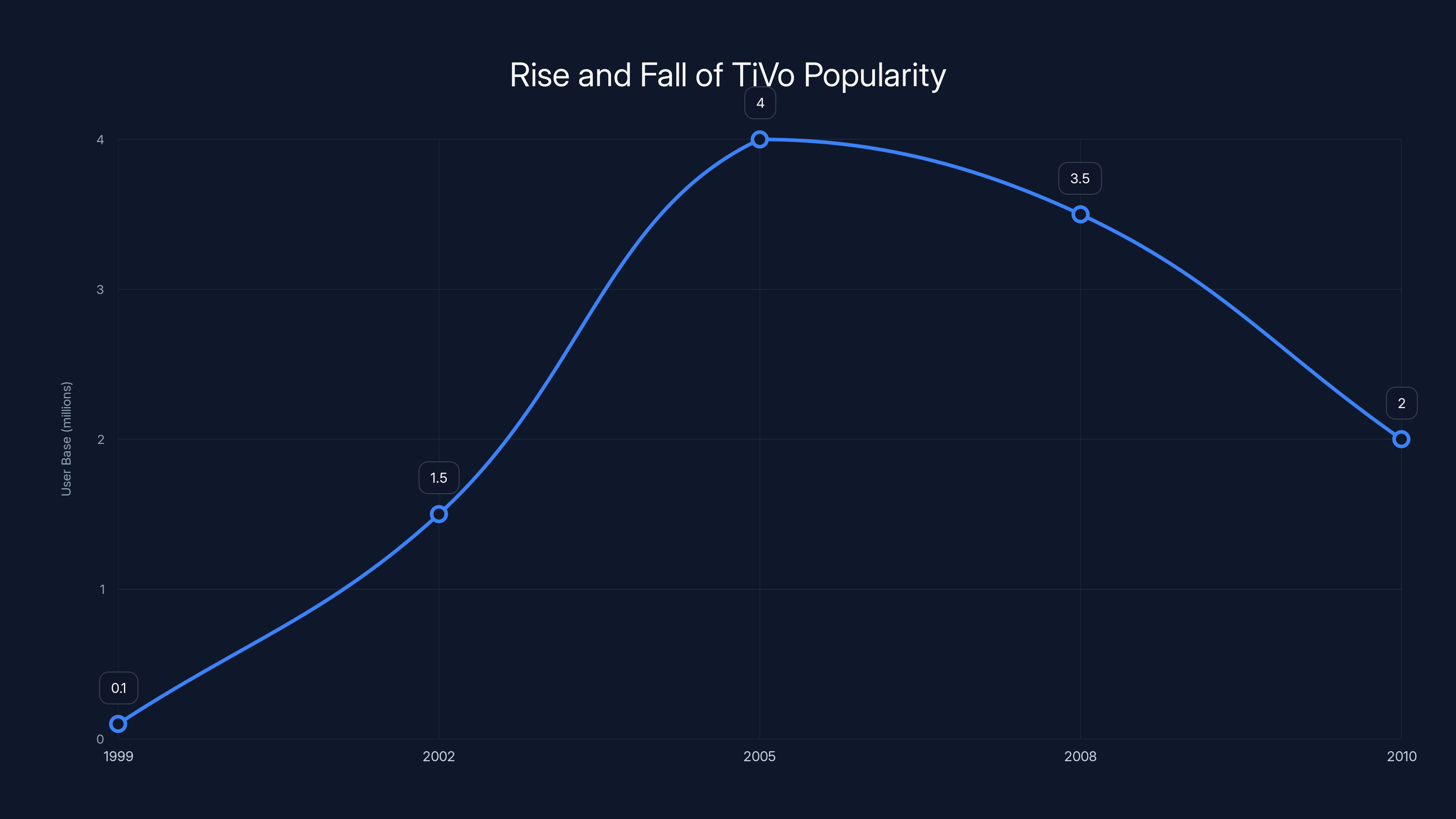

TiVo's user base grew rapidly after its launch in 1999, peaking around 2005 before declining due to competition from cable DVRs and streaming services. (Estimated data)

TiVo Arrives: The Invention That Changed Everything

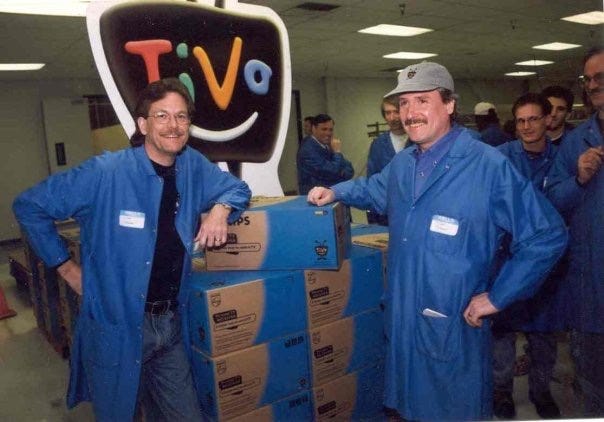

TiVo was founded in 1997 by Mike Ramsay and Jim Barton, two engineers who had a radical idea: what if your television recorder was actually smart? What if instead of programming it manually, the device could learn what you liked to watch and record it automatically?

It sounds almost mundane now, but imagine pitching that in 1997. These weren't just engineers. They understood consumer technology, and they understood that the biggest barrier to VCR adoption wasn't the recording part—it was the complexity. They wanted to build something that felt effortless.

Their first TiVo boxes arrived in 1999, and they cost around

The user experience was designed to be intuitive. You didn't program channels and times—you told TiVo what shows you liked, and it would watch for them in the program guide and record them automatically. You could name recordings. You could search by actor or director. You could set season passes for shows, and it would grab every episode. If a show aired at an unusual time, you didn't care—TiVo would find it and record it.

And the pause button. God, the pause button. That simple feature—the ability to freeze live television, to add a commercial break whenever you wanted one—was genuinely transformative. It's hard to overstate how much this single feature changed the relationship between viewers and their televisions.

When the TiVo boxes started appearing in homes, people's reactions were overwhelmingly positive. Early adopters—and TiVo's initial audience was definitely early adopters—felt like they'd hacked television. They'd found the exploit. They could watch anything, whenever they wanted, and skip the commercials. It felt like freedom.

The Cultural Moment: When TiVo Became a Verb

Something unexpected happened in the early 2000s. TiVo stopped being a tech product and became a cultural phenomenon.

It showed up as a plot point on television shows. Characters would mention TiVoing something. "I'll TiVo it" became something people actually said in conversation—and major networks and studios noticed. Madison Avenue was watching. Hollywood was watching. TiVo boxes started appearing in celebrities' homes. Actors talked about their TiVos in interviews.

By 2002 or 2003, TiVo had become a status symbol. Owning one meant you were sophisticated enough to appreciate good television, wealthy enough to afford it, and smart enough to use the technology. It was the intersection of tech enthusiasm and cultural cachet that most gadgets never achieve.

The company's stock price reflected this enthusiasm. In 2000, TiVo went public, and the stock soared. Investors saw a company that had invented something genuinely new, that had proven people wanted this product, and that had created brand awareness most startups only dream of.

Magazines profiled the company. Technology blogs obsessed over every update. When a new version of the TiVo software arrived, it was a news event. When the pause button behavior changed slightly, people noticed. The community of TiVo users became vocal, passionate, and loyal.

Advertisers, meanwhile, were horrified. TiVo's whole value proposition—its core feature—was the ability to skip commercials. From the networks' perspective, TiVo was a threat. They were selling airtime based on the promise that people would watch the ads, and TiVo was letting viewers ignore the ads entirely.

This tension would become important later. For now, though, TiVo was the hottest consumer electronics company in America. The future seemed bright.

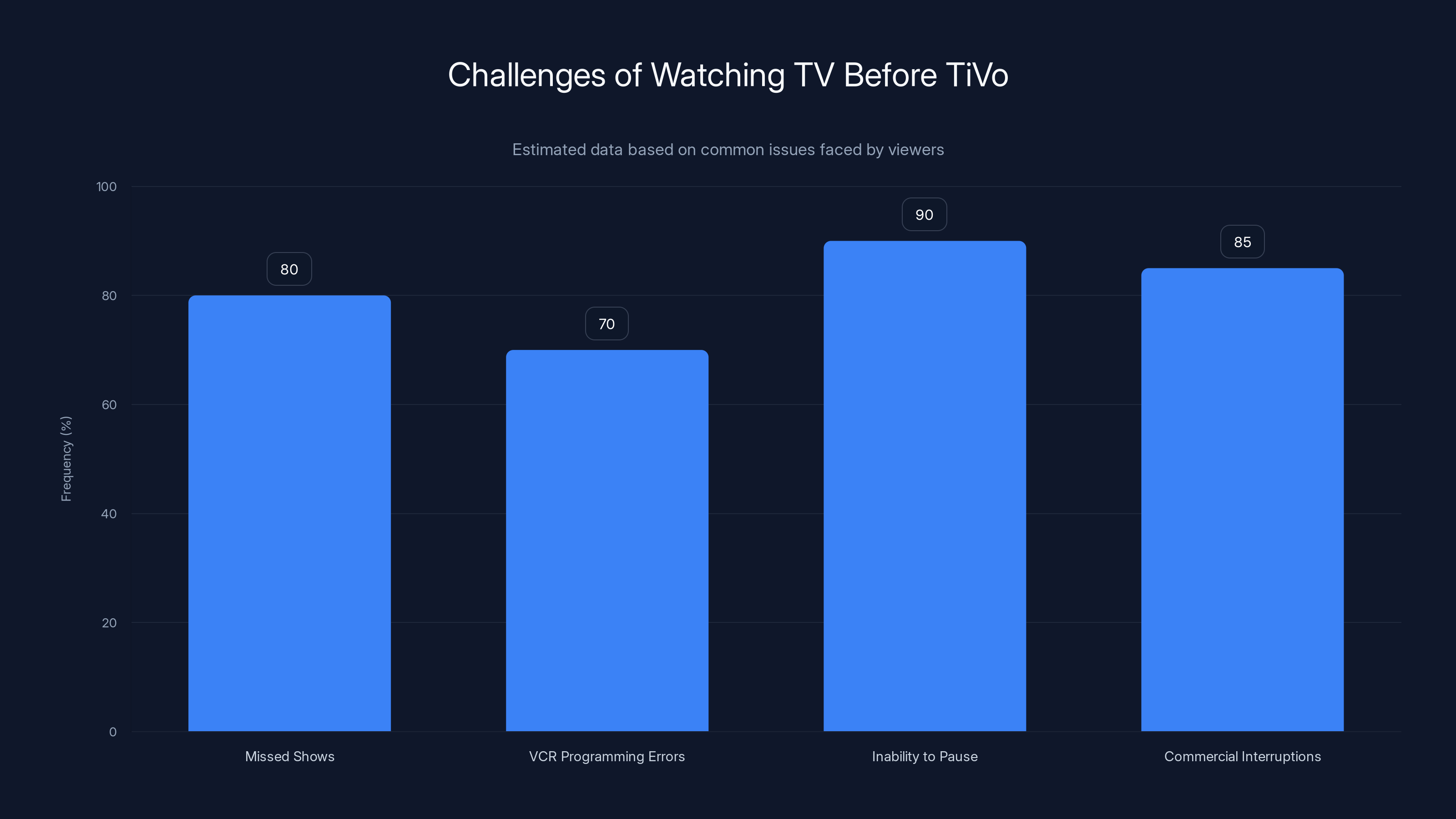

Before TiVo, viewers frequently faced issues like missing shows and being unable to pause live TV. Estimated data shows high frustration levels with traditional TV viewing.

The Technical Innovation: How TiVo Actually Worked

Understanding TiVo's failure requires understanding what made it work in the first place, and that means looking at the actual technology.

Early TiVo boxes were essentially small computers running a custom operating system. They connected to your cable box or satellite receiver, intercepted the signal, and stored it on an internal hard drive. The hard drive was the critical component—it provided storage that was impossible with VCRs, and it was durable in a way that magnetic tape wasn't.

The real magic, though, was in the software. TiVo's recommendation engine learned what you watched and suggested shows you might like. The program guide was automatically updated (later versions connected to the internet to fetch new listings). The interface was designed to feel responsive and alive—when you paused, it paused instantly. When you rewound, the scrubbing was smooth. Everything felt intuitive because the engineers had obsessed over every interaction.

There was also a subscription component. TiVo didn't just sell boxes—you had to pay for the service. The monthly fee (usually $10-15) got you access to the program guide and the electronic scheduling. This subscription model was ahead of its time. It meant TiVo had recurring revenue, not just one-time hardware sales. It also meant the company could improve the service over time and charge for those improvements.

The cable and satellite companies immediately saw TiVo as a threat. They controlled the box in your home (the cable box), and now this upstart company was creating a device that sat between their box and your TV, taking a cut of the relationship. The cable companies saw an opportunity and a danger: the danger was that TiVo was more user-friendly than anything they controlled, but the opportunity was that they could build DVR functionality into their own boxes and cut TiVo out entirely.

This would be one of TiVo's fatal mistakes: relying on cable and satellite companies as partners when those companies were actually competitors.

The Business Problem: Inventing Isn't Enough

Here's the thing about inventing something great: making the product is only about 30% of the challenge. The other 70% is building a business around it.

TiVo invented the DVR. But they didn't own the cable boxes that connected to the DVR. They didn't control the program guides that the networks used. They couldn't force cable companies to carry their boxes. They had no leverage.

Meanwhile, cable and satellite companies watched the TiVo phenomenon with interest. They saw a product that customers loved. They also saw an opportunity. If they added DVR functionality to their own boxes—boxes that they already controlled and that were already in millions of homes—they could offer the same features without paying TiVo a dime.

Starting in the early 2000s, cable and satellite providers began rolling out their own DVRs. Comcast created their own DVR. DirecTV partnered with others. Suddenly, the feature that made TiVo special—the ability to record and pause live television—was no longer exclusive to TiVo. Cable customers could get basically the same functionality from their cable provider, included in their subscription or for a small additional fee.

TiVo's market immediately started shrinking. The company had grown to a point where they were actually shipping a reasonable number of boxes, but the addressable market—people who wanted a DVR and didn't already have one from their cable company—was evaporating.

The company tried to adapt. They pursued licensing deals with cable companies, hoping to provide the software that powered their DVRs. Some deals went through, but many cable companies preferred to build or customize their own systems. TiVo also tried different revenue models: would people pay for premium features? Would they pay for a higher-quality guide? Would they pay for advanced search capabilities?

None of it stuck. The market had spoken, and what it said was: DVR functionality should be included with your cable service, not purchased separately.

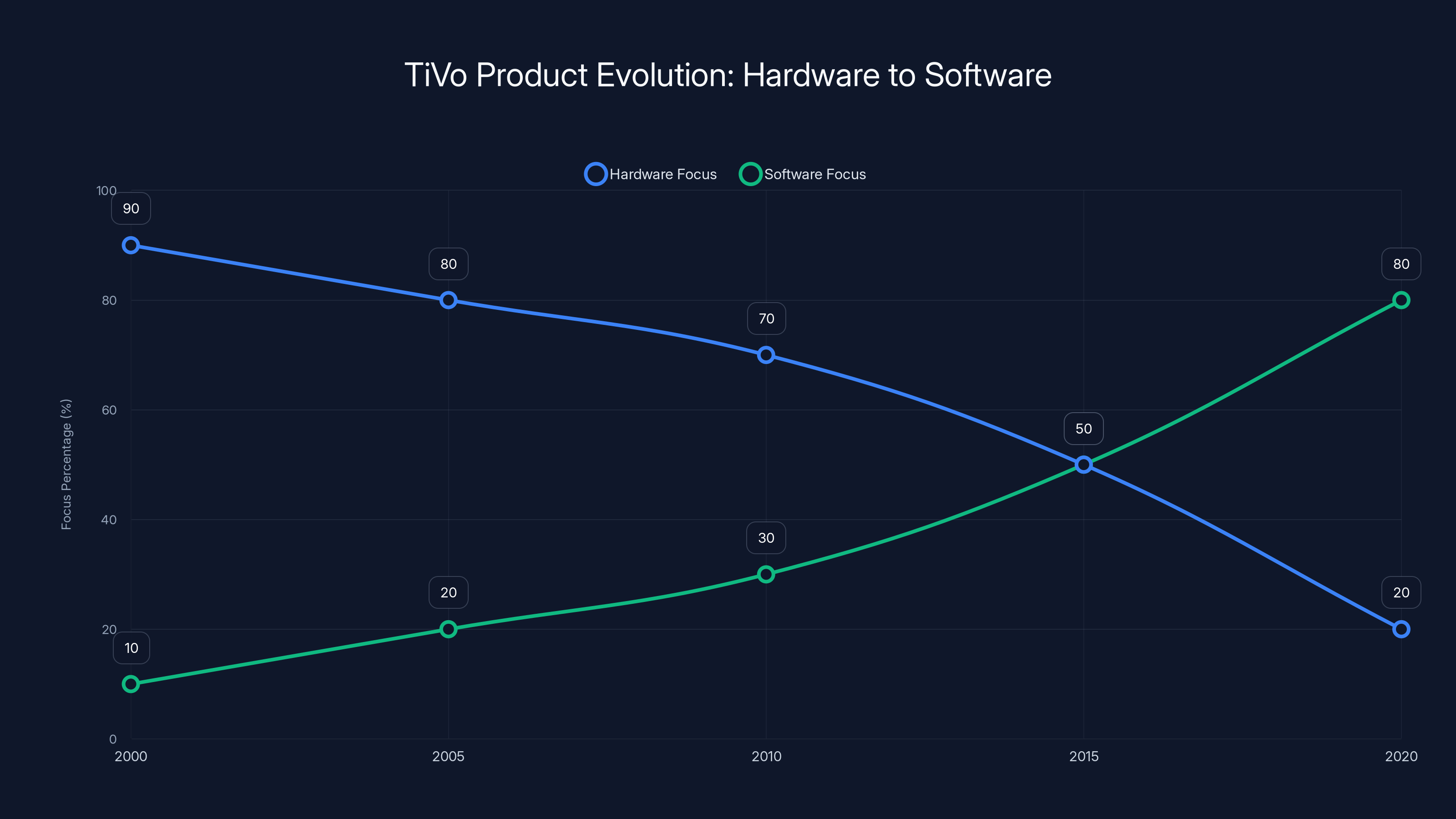

Estimated data shows TiVo's shift from hardware to software focus over two decades, reflecting market trends towards software solutions.

The Streaming Problem: The Real Killer

If cable companies building their own DVRs was TiVo's first major threat, streaming services were the meteor strike that ended the dinosaur.

Netflix launched in 1997—the same year TiVo was founded—but for most of TiVo's peak years, streaming wasn't really a thing. Netflix was about getting DVDs by mail. Then broadband got faster, video compression got better, and in 2007, Netflix started streaming movies. Hulu launched in 2008. YouTube was already huge.

These services didn't require DVRs. If you wanted to watch something, you didn't have to wait for it to air at a specific time. It was just there, on demand, whenever you wanted. No commercials (or at least, no commercials that you couldn't skip). No waiting for a recording to finish. Just pick what you want to watch and watch it.

TiVo's entire value proposition was built on solving a problem that streaming services made irrelevant. They had solved the problem of "how do I watch what I want when I want to watch it?" But Netflix and Hulu had solved it better. They'd made the problem go away entirely.

Worse, the people who had the problem now weren't the target audience anymore. By 2012 or so, people who wanted on-demand TV were subscribing to streaming services, not buying TiVo boxes. And the people who still had TiVos were the ones who primarily watched live television—sports fans, news junkies, people who couldn't adapt to streaming.

The irony is savage: TiVo had proven that on-demand television was what people actually wanted. They'd created the market and demonstrated demand. But they'd done it in a way that the cable companies could copy, and then the streaming companies had come along and made the entire approach obsolete.

TiVo had won the battle and lost the war.

The Patent Wars: Winning Legally While Losing Commercially

As TiVo's business model crumbled, the company pivoted to what would become its defining characteristic: patent litigation.

TiVo held fundamental patents on DVR technology. They had invented the category, so they owned the underlying intellectual property. As cable companies and device manufacturers built DVRs, TiVo sued them. A lot. The company started winning settlements and licensing fees.

On paper, this looked like a victory. TiVo won court cases against Comcast, against EchoStar, against various cable companies. The company extracted billions in licensing fees. Hundreds of millions in settlements. At one point, TiVo's revenue was primarily coming from patent litigation and licensing rather than actual product sales.

But this was a losing play over the long term. Every time TiVo sued someone, it reinforced that they were now a litigation company, not a product company. The brand that had been cool and innovative became associated with patent trolling. Every lawsuit was a story about a company suing for innovation it had created, not innovating itself.

Moreover, the licensing revenue was finite. Once you've sued all the cable companies, once you've extracted licensing fees from the major players, what's left? You're suing smaller players for smaller sums. The revenue trend was eventually going to be downward.

The patent wins proved that TiVo had invented something fundamental and protected it well. But they proved it in a way that destroyed the company's future. They were getting paid for past innovation, not creating the future.

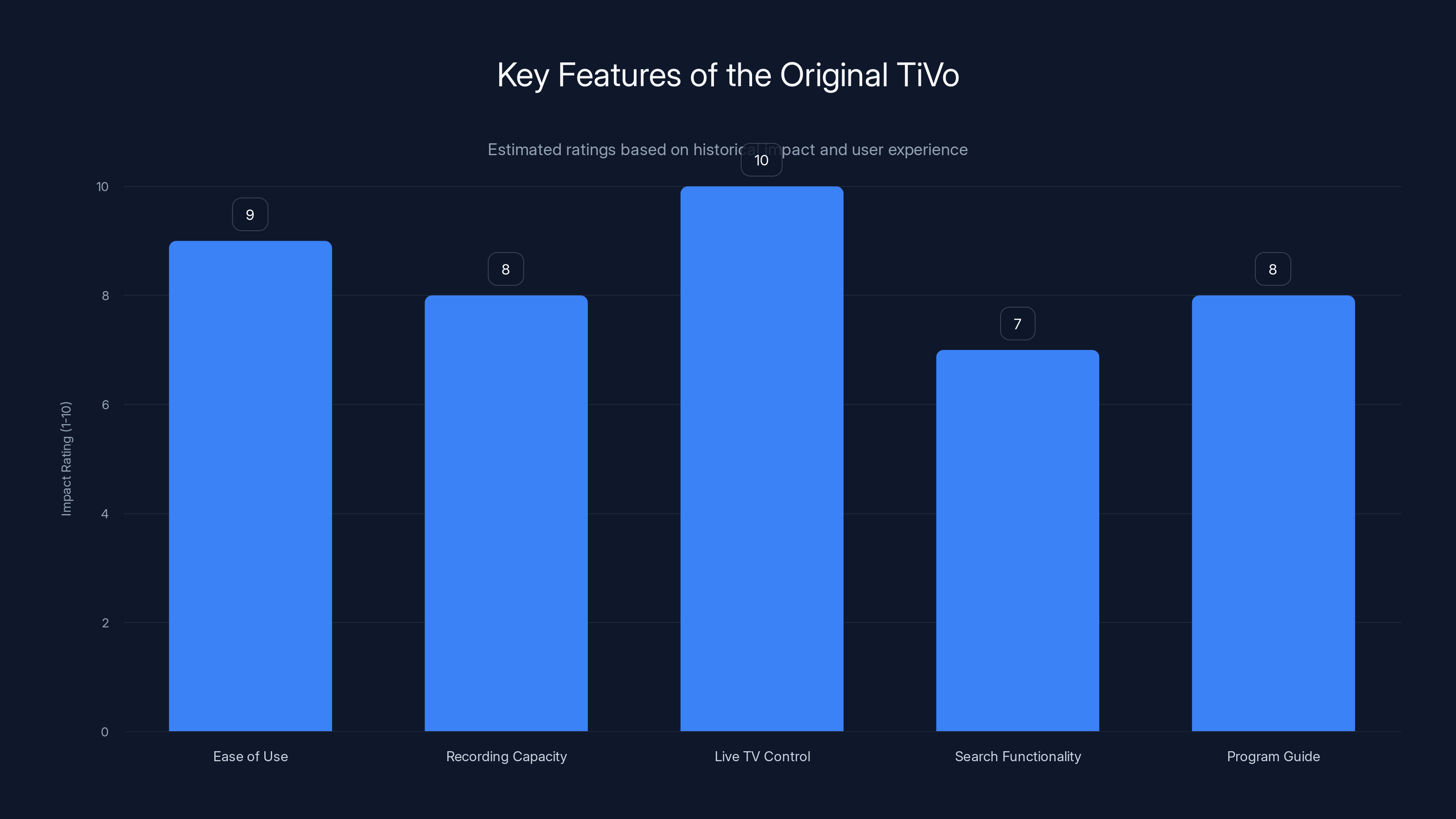

TiVo's live TV control and ease of use were its most revolutionary features, transforming how viewers interacted with television. (Estimated data)

The Product Evolution: From Hardware to Software

TiVo didn't just sit around suing people. The company continued iterating on its hardware, releasing new boxes, adding new features, and trying to adapt to the changing market.

The TiVo Bolt came out in 2015. It was a beautifully designed box that looked more like high-end audio equipment than consumer electronics. It supported 4K, had a faster interface, and included features like voice search. It was genuinely a nice product. But by 2015, who was even buying standalone DVRs anymore? The market had moved on.

The company also developed software that could run on TiVo boxes, and they licensed that software to cable companies. Some of this licensing was successful—they had relationships with various cable providers—but it was a far cry from the days when TiVo boxes were in millions of homes.

There was also the TiVo Stream, which was an attempt to bridge the gap between traditional DVR functionality and streaming. It let you watch your TiVo box remotely, which was actually pretty useful for people who still had TiVo systems. But it was a niche product for a niche market.

Everything TiVo did in this period was competent. The products were good. But none of it mattered because the fundamental use case for standalone DVRs had disappeared. TiVo had solved the problem of controlling your television so thoroughly that the solution had become a utility, commodified and bundled with cable service or made irrelevant by streaming.

The Rovi Merger: The Last Hope

In 2016, TiVo merged with Rovi, a company that provided metadata for DVRs, cable boxes, and other devices. It was a merger that made sense on paper: Rovi had business relationships with cable companies and device manufacturers. TiVo had technology and IP. Together, they might be able to create something sustainable.

For a brief moment, it looked like it might work. The merged company called itself TiVo (keeping the stronger brand name) and positioned itself as a software and service company for the pay-TV industry. They could provide the guide data, the DVR software, and the user interface for cable companies' boxes.

But by 2016, the underlying problem hadn't changed: the market for cable-based DVR services was shrinking because streaming was growing. Cable companies were losing customers, cutting costs, and weren't interested in paying more for premium DVR software. They wanted cheaper solutions.

The Rovi merger ultimately didn't save TiVo. By the early 2020s, TiVo had become primarily a licensing company that handled metadata and guided user experiences for some cable providers, but it was no longer relevant to actual consumers. If you bought a TiVo product, you were probably out of the mainstream—you were someone who wanted a premium DVR for some reason.

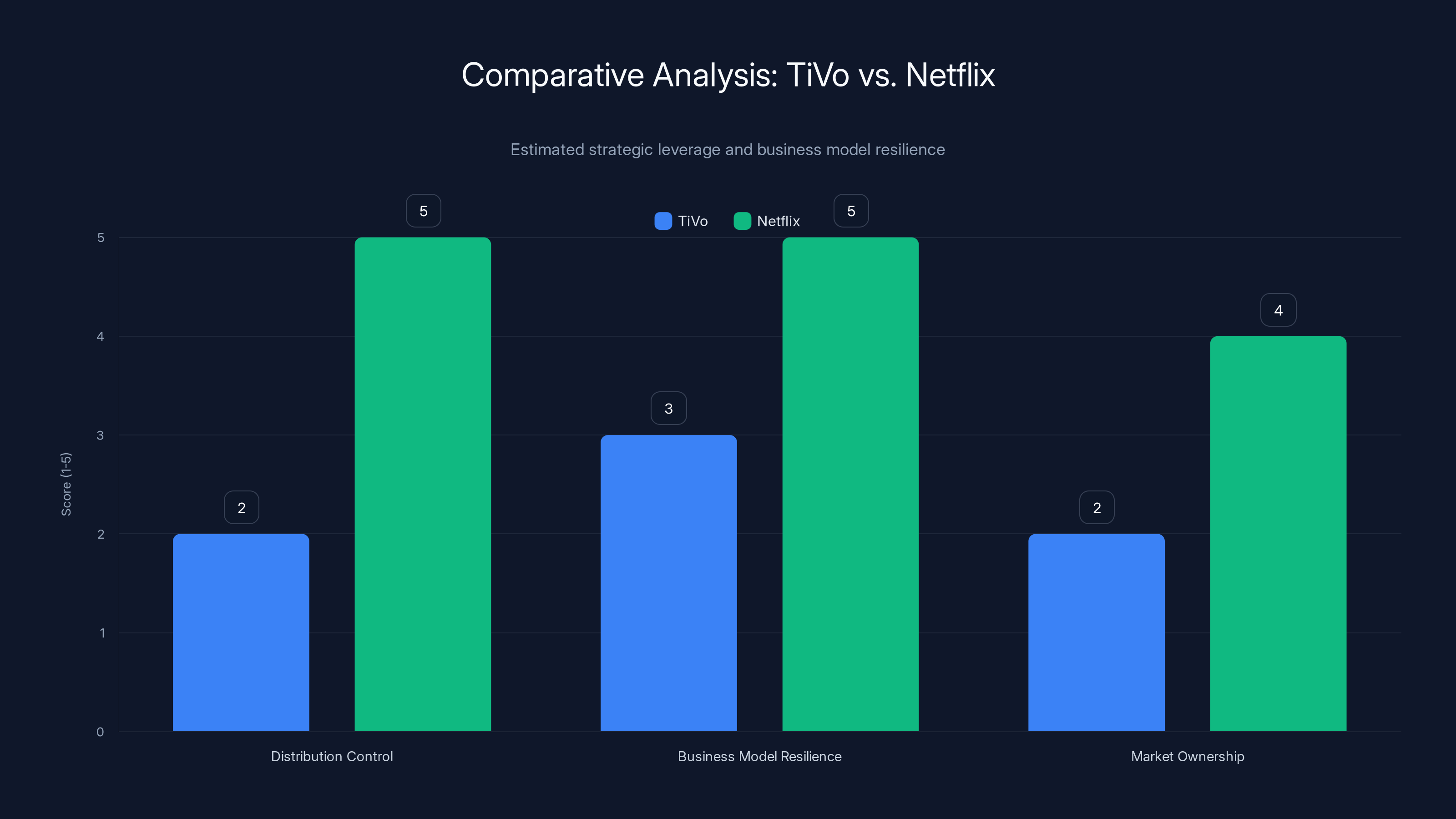

Netflix outperformed TiVo in distribution control and business model resilience, leading to greater market ownership. Estimated data based on strategic insights.

The Shutdown: The End of an Era

In 2024, TiVo announced that it would be discontinuing its DVR hardware business. No more new TiVo boxes. The company would focus entirely on licensing and software for cable companies.

It was the final, definitive acknowledgment that TiVo the product was dead. The company that invented the DVR, that proved pausing and recording live TV was something people wanted, that became so culturally significant that its name became a verb—that company was getting out of the DVR business entirely.

For people who still had old TiVo boxes at home, the decision was bittersweet. The boxes mostly still work. TiVo service continued for existing customers, at least for a while. But there would be no new products, no new hardware. The TiVo brand in consumer consciousness was effectively retired.

What killed TiVo wasn't a lack of innovation. It wasn't bad products. It was something more fundamental: the company invented a category, proved the market existed, and then got disrupted by two different forces (cable companies copying them, and streaming services making the whole category unnecessary) that they couldn't control and couldn't compete against.

It's one of the most instructive failures in technology history. TiVo did everything right and still lost.

The Lasting Impact: Living in the World TiVo Imagined

Here's the thing that makes TiVo's story truly bittersweet: we live in the world that TiVo created. We just do it without TiVo.

The fundamental insight that TiVo had was correct: people don't want to be slaves to broadcast schedules. They want to watch what they want when they want to watch it. They want to skip commercials. They want to pause and rewind. They want control over their television experience, not the other way around.

Netflix, Hulu, Disney Plus, Amazon Prime—all of these streaming services are built on that exact premise. They've proven, decisively and repeatedly, that TiVo was right about what the market wanted. They've just solved the problem more thoroughly than TiVo could have.

But there's more to TiVo's legacy than just the concept. TiVo changed how television is made. Once TiVo boxes were in millions of homes, studios and networks realized they needed to adapt. They couldn't rely on people watching shows at scheduled times anymore. Shows needed to be findable, searchable, and attractive to watch on-demand.

This led directly to binge-watching culture, to serialized shows that are designed to hook you for entire seasons, to television that's optimized for non-linear consumption. Prestige television—the golden age of HBO and then Netflix originals—emerged in a world where TiVo had already proven that people wanted control over when they watched things.

TiVo also proved that the technology industry underestimates how much people hate complexity. The company's entire success was built on the insight that VCRs were too hard to use, so if you made something easier, people would choose it even if it cost more. This principle has guided consumer electronics ever since.

And the pause button. The pause button that TiVo pioneered is now so fundamental to our experience of media that we barely notice it. You can pause anything on any streaming service. You can pause live television on cable-provided DVRs. You can pause YouTube videos, podcasts, music. The ability to pause and resume has become so universal that it's now a basic feature, not a radical innovation.

But it took TiVo to prove that was something people actually wanted.

Why TiVo Failed: The Strategic Lessons

If you want to understand why a company that invented an entire category could end up irrelevant, TiVo is the textbook case.

The first lesson is about distribution. TiVo's boxes were sold directly to consumers, but the infrastructure they depended on—the cable signal, the program guide data, the commercial broadcasts—was controlled by other companies. Those companies could choose to work with TiVo or work against them. When working against TiVo became profitable, they did it. TiVo had no leverage.

Compare this to Netflix, which built its own infrastructure. Netflix doesn't depend on cable companies for content delivery. It controls its own destiny (or at least, it controls it much more than TiVo did). The lesson is that if you're going to create a new category, you need to control the critical path.

The second lesson is about business models. TiVo's business model was based on hardware sales and subscriptions. Both of these are good, but they're vulnerable to disruption. If hardware gets cheaper (which it did, as cable boxes became DVRs), your hardware business dies. If someone offers better service (streaming, in TiVo's case), your subscription becomes less relevant. A business model that relies on staying ahead of competition through constant innovation is fragile. A business model that locks in customers or creates switching costs is more durable.

The third lesson is about the difference between inventing a category and building a sustainable business. TiVo invented the DVR category. They proved the market existed. But they didn't own the market in a way that would let them capture the value they created. They were, in a sense, too successful at proving the concept—because once the concept was proven, larger companies with more resources and control over distribution could execute on it better than TiVo could.

This is actually a pretty common pattern in technology. The company that invents something doesn't always end up being the company that wins commercially. VCRs were invented before TiVo existed, but the winners in the home video market ended up being companies like Sony and Panasonic that could manufacture at scale, not the inventors. The same dynamic played out with TiVo.

TiVo's Cultural Legacy: Why We Still Remember It

TiVo is gone, or at least, TiVo the consumer brand is gone. But the company has had an outsized impact on how we think about technology, consumer experience, and the relationship between viewers and media.

First, there's the brand achievement. "TiVo" became a verb. "To TiVo" meant to record something, and for a while, that was how regular people talked about the feature. Google eventually achieved the same status, but TiVo got there first. That's remarkable. Most technology companies are doing well if their product becomes well-known. Becoming a verb means you've achieved a level of cultural penetration that's almost impossible to imagine.

Second, there's the user experience principle. TiVo proved that ease of use can be a competitive advantage, and that there's significant value in removing friction from consumer experiences. The company's obsession with making complicated technology simple influenced how consumer electronics companies approach interface design. The principle of making things as intuitive as possible has become standard, and TiVo deserves some credit for proving that was valuable.

Third, there's the innovation lesson. TiVo showed that you could take existing technology (hard drives, program guides, television signals) and combine them in a new way to create something that felt genuinely transformative. The company didn't invent hard drives or electronic program guides. They took existing components and assembled them in a way that nobody else had thought to do. That's an important type of innovation.

And then there's what TiVo proved about how technology should work. The company created the vision of television on-demand, of viewers controlling their own experience, of the collapse of the distinction between "now" and "later" in entertainment. That vision has completely won. We live in a world where on-demand is normal, where the idea of being forced to watch something at a scheduled time seems ridiculous, where DVRs (whether physical or integrated into cable boxes or replaced by streaming services) are just an assumption.

TiVo proved that was the future. They just didn't get to own the future once it arrived.

The Streaming Wars: How TiVo's Legacy Evolved

If TiVo invented on-demand television, streaming services have perfected it.

When you subscribe to Netflix, you're experiencing the logical endpoint of what TiVo pioneered. You don't care when a show aired. You don't need to record it. You don't need to wait for reruns. You just click play and watch. The show is available on demand, forever, whenever you want it.

But there's a catch, and TiVo understood this better than most companies: on-demand television is only valuable if you have a good way to discover what to watch. This is why Netflix invested so heavily in recommendation algorithms, and why the home screen of every streaming service is carefully designed. You could have infinite content available, but if you can't find anything to watch, it's useless.

TiVo understood this too. The company's recommendation engine and program guide were as important as the pause button. They helped you figure out what was worth watching.

Streaming services have taken this principle further. They use machine learning to recommend shows. They create playlists based on your viewing history. They highlight new releases. They've essentially turned content discovery into the core product.

This is another area where TiVo's DNA lives on, even if the company doesn't. The fundamental idea that the technology around television—the recommendations, the guides, the way content is organized—is just as important as the content itself has become industry standard.

What Modern Tech Companies Get Right That TiVo Got Wrong

Looking at TiVo's failure through the lens of 2025, there are some clear patterns about what modern tech companies do that TiVo didn't.

First, modern winners control their full stack, or they partner strategically. Apple controlled the iPhone, the App Store, and the services. Amazon controlled AWS, its retail platform, and its streaming service. Netflix controlled content, distribution, and the recommendation engine. TiVo relied on cable companies for distribution and couldn't force them to partner on favorable terms. That's a fundamental weakness.

Second, modern winners focus on network effects or lock-in. Netflix has your watch history, your recommendations, and your playlists. Switching costs are high. TiVo had your recorded shows and your preferences, but once cable companies added DVRs, switching to a cable-provided DVR had zero switching cost and zero benefit to the cable company—they just didn't have to pay TiVo licensing fees.

Third, modern winners understand that hardware is a Trojan horse for software and services. Apple makes hardware, but the real value is the ecosystem. Amazon sells devices, but the real business is AWS and advertising. TiVo made hardware and tried to sell subscriptions, but the subscriptions were optional, and other companies could provide the same feature bundled with other services. The business model wasn't sticky enough.

Fourth, modern winners expand before they can be disrupted. Netflix could see that streaming would eat cable—because streaming was eating cable, and the company was the one doing the eating. TiVo should have seen that streaming would make standalone DVRs obsolete, and they should have either built a streaming service or pivoted into software much earlier than they did. They didn't move fast enough.

The Verdict: Innovation Isn't Enough

So what's the ultimate verdict on TiVo? It's more complicated than just "the company failed."

TiVo succeeded in the most important way: it created a new market and proved that the market existed. The company invented something that people genuinely wanted, and they proved it by selling boxes, building a brand, and creating a product that people loved.

But TiVo failed in the ways that matter commercially: it didn't own the market it created, it didn't build switching costs that would keep customers loyal, and it didn't expand fast enough to survive the disruption that it itself had enabled.

The tragic irony is that TiVo won the battle to show the future was on-demand television. Then larger companies with more resources, better distribution, and deeper pockets copied their innovations and did them at scale. And then entirely new companies (Netflix, Amazon, Disney) came in from left field with a completely different model and made the whole category obsolete.

TiVo took the pause button from science fiction and put it in living rooms across America. For a moment, that was enough to make the company a phenomenon. But the moment passed, and the company couldn't adapt fast enough to survive it.

The world that TiVo imagined—a world where television is on demand, where you control when you watch, where commercials can be skipped—that world is here. It's just not a TiVo world. It's a Netflix world, a Disney Plus world, an Apple TV Plus world. TiVo won the war of ideas and lost the war for market dominance. In technology, that's often how it goes.

FAQ

What exactly was TiVo?

TiVo was a digital video recorder (DVR) company that pioneered the consumer market for DVRs starting in 1999. The company sold standalone boxes that could pause, rewind, and record live television, and automatically record shows based on your preferences. It was genuinely revolutionary at the time and became so popular that "to TiVo" became a common verb meaning to record a TV show.

How did TiVo's technology actually work?

TiVo boxes contained hard drives to store video, a tuner to receive TV signals, and custom software to manage recordings and create an intuitive user interface. The software included a recommendation engine that learned what shows you liked and automatically recorded them based on your preferences. Users could pause live television, rewind, search for shows by actor or director, and set season passes to automatically record future episodes. The program guide was updated automatically via internet connection, eliminating the need for manual programming.

What made TiVo so special when it first launched?

TiVo solved a fundamental consumer frustration: VCRs were complicated, error-prone, and required technical expertise to operate. TiVo made recording and watching television simple and intuitive. The pause button alone was revolutionary—it allowed viewers to pause live television, something that seemed like magic in 1999. Combined with the ability to skip commercials, automatically record shows, and search for content, TiVo fundamentally changed the relationship between viewers and their televisions.

Why did TiVo fail despite being a great product?

TiVo failed for several strategic reasons. First, cable and satellite companies immediately saw TiVo as a threat and built DVR functionality into their own boxes, making TiVo's standalone product redundant for most consumers. Second, streaming services like Netflix made on-demand television available without requiring a DVR at all, making the entire product category less relevant. Third, TiVo lacked control over distribution and couldn't force cable companies to partner with them. Finally, the company pivoted to patent litigation rather than continuing to innovate, which hurt the brand and couldn't sustain long-term growth.

What happened to TiVo after it fell behind?

After losing the consumer market, TiVo pivoted to patent licensing, winning billions in settlements and licensing fees from cable companies and device manufacturers. The company merged with Rovi in 2016 to create a metadata and software licensing business focused on serving cable providers. By 2024, TiVo announced it would discontinue its DVR hardware business and focus entirely on software licensing, effectively ending the company's role as a consumer brand.

How did TiVo change television and TV consumption?

TiVo proved that viewers wanted control over when they watched television, not broadcast schedules. This insight revolutionized television production and distribution. Networks and studios adapted their strategies to assume viewers would watch on-demand. Streaming services like Netflix built their entire model on the principle that TiVo had proven: people want to watch what they want when they want to watch it. The binge-watching culture and prestige television era emerged directly from a world where TiVo had already demonstrated that on-demand viewing was what audiences actually wanted.

Is TiVo still relevant today?

TiVo the consumer brand is essentially dead—the company stopped making DVR hardware in 2024. However, TiVo's intellectual property, patents, and licensing deals continue to generate revenue from cable companies and device manufacturers. More importantly, TiVo's legacy lives on in every streaming service and cable-provided DVR that lets you pause, record, and watch television on-demand. The fundamental innovations TiVo pioneered have become so universal that they're now invisible—but they're everywhere.

Conclusion

TiVo's story is one of the most instructive in technology history, and not because the company won. It's instructive because it won in every way except the way that mattered most commercially.

The company invented something genuinely revolutionary. It created a product that people loved. It became a cultural phenomenon. It proved that on-demand television was not just something consumers wanted but something they would pay premium prices to get.

And then it lost.

The pause button that TiVo gave the world is now everywhere. You can pause any streaming service. You can pause your cable DVR. You can pause YouTube, podcasts, music. Pausing live television is so standard that nobody even thinks about it anymore. TiVo proved that was something people needed, and the world agreed. The category TiVo invented—the DVR—is now just a basic feature, bundled into cable service or made irrelevant by streaming.

But TiVo, the company, didn't win that world. Netflix won. Streaming won. Cable companies won by copying TiVo's innovations before TiVo could lock down the market. Apple and Amazon and Disney won by building ecosystems that made standalone DVRs unnecessary.

TiVo had the right idea. It just didn't have the distribution, the switching costs, the strategic positioning, or the execution to defend its market. And in the end, that's what matters in technology. Having a good idea is table stakes. Executing on it, building a durable business around it, and defending it against competitors—that's what actually wins.

We live in the TiVo world. We just don't live with TiVo anymore. And that, perhaps, is the most fitting ending for a company that proved it understood the future better than anyone else, but couldn't quite stay relevant long enough to inherit it.

If TiVo's story teaches us anything, it's that innovation is only the beginning. The real challenge in technology is turning innovation into a sustainable, defensible business. TiVo proved the market existed but couldn't capture the value they created. That's a lesson that every startup founder should learn from this company's remarkable and tragic history.

The pause button changed television forever. But the company that invented it? It couldn't quite pause long enough to survive the future it imagined.

Key Takeaways

- TiVo invented the DVR and proved consumers wanted on-demand television with pause, rewind, and recording capabilities

- The company became a cultural phenomenon and even a verb, but failed to maintain market dominance as cable companies and streaming services copied its innovations

- TiVo's core failure was lack of control over distribution and inability to build switching costs that would lock in customers

- The company won the patent litigation wars but ultimately pivoted to licensing rather than innovation, signaling commercial defeat

- We live in the world TiVo imagined—with on-demand television everywhere—but without TiVo, proving that inventing a category isn't enough to win it

Related Articles

- Best Tech Deals This Week: Fitness Trackers, Chargers, Blu-rays [2025]

- CES 2026 Best Products: Pebble's Comeback and Game-Changing Tech [2025]

- Best CES 2026 Gadgets Worth Actually Buying [2025]

- CES 2026 Best Tech: Complete Winners Guide [2026]

- Ozlo's Sleep Data Platform: The Future of Sleep Tech [2025]

- Where's the Trump Phone? CES 2026's Biggest No-Show [2026]

![The Complete History of TiVo: How It Changed TV Forever [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-complete-history-of-tivo-how-it-changed-tv-forever-2025/image-1-1768142162780.jpg)