Introduction: The Great Smartphone Escape Fantasy

Somewhere around 2023, a cultural shift started rippling through college campuses and TikTok feeds. Young people began openly fantasizing about ditching their iPhones for basic phones that only made calls and texts. Not as a joke. Not ironically. Genuinely.

At first, it seemed like peak Gen Z rebellion: reject the algorithm, reclaim your attention, stick it to Big Tech. The aesthetic was pure counterculture. Chunky Nokia bricks and flip phones appeared in Instagram stories like they were vintage band merch. Dumbphone users became the cool kids. They had better things to do than scroll. They had real conversations. They touched grass.

I get it. I really do. I waste approximately four hours daily to the tyranny of endless scrolling. I lose sleep to TikTok's infinite feed. I feel the familiar shame spiral every time I unlock my home screen and lose two hours to videos of strangers I'll never meet. My screen time is objectively out of control.

But here's what fascinates me about the dumbphone movement: it's rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding of how our brains actually work. The people ditching smartphones aren't evil geniuses who've figured out the ultimate hack. They're operating under an assumption that's almost certainly wrong. They believe that cognitive function is portable. That you can just... unplug from technology and your brain will bounce back to some earlier, purer version of itself.

The problem is messier than that. Over the past two decades, something genuinely strange has happened to human cognition. Our brains haven't just adapted to smartphones. They've fundamentally fused with them. We've outsourced core memory functions, navigation, social coordination, scheduling, and information retrieval to rectangular devices we keep in our pockets.

And here's the uncomfortable truth: you can't just undo that fusion.

This isn't speculation. This is cognitive science. This is what happens when external tools become so deeply integrated with our neural architecture that they stop being "tools" and become literal extensions of our mind.

Let me explain why Gen Z's dumbphone dream, while aesthetically appealing and ideologically satisfying, might actually represent a cognitive step backward that most of these users couldn't sustain even if they desperately wanted to.

TL; DR

- Extended mind hypothesis: Smartphones aren't separate from our brains; they're cognitive extensions that function as a single system

- Transactive memory: We've outsourced so much information storage to devices that losing them means losing actual memories

- Generational integration: Those who grew up with smartphones have never developed the offline cognitive skills that older generations had

- The illusion of choice: You can switch to a dumbphone, but your cognitive architecture remains enmeshed

- Real cost of quitting: Reduced competence, social friction, and authentic memory loss, not just digital detox benefits

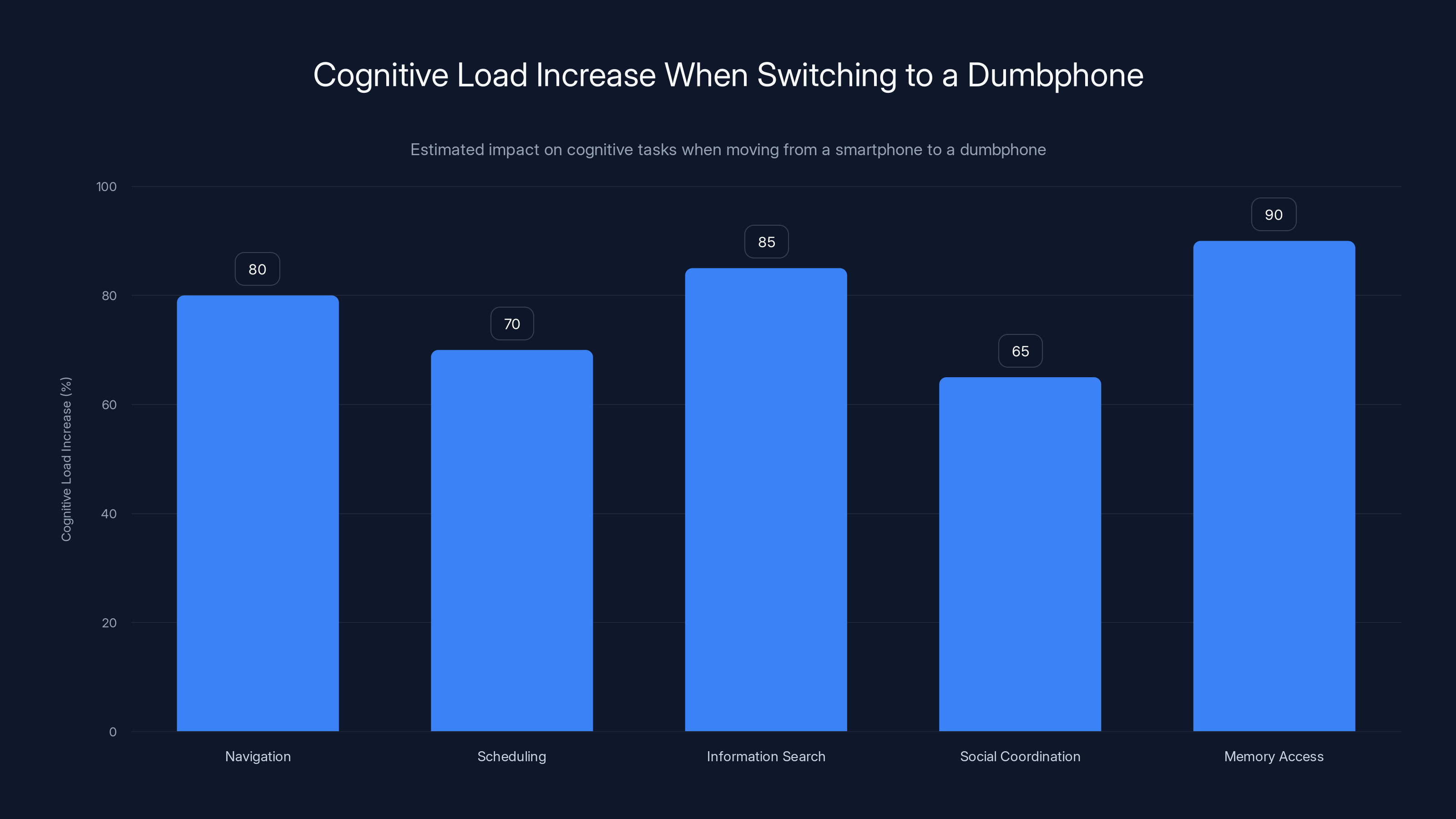

Switching to a dumbphone significantly increases cognitive load, particularly in memory access and information search, as these tasks are no longer outsourced to a smartphone. Estimated data.

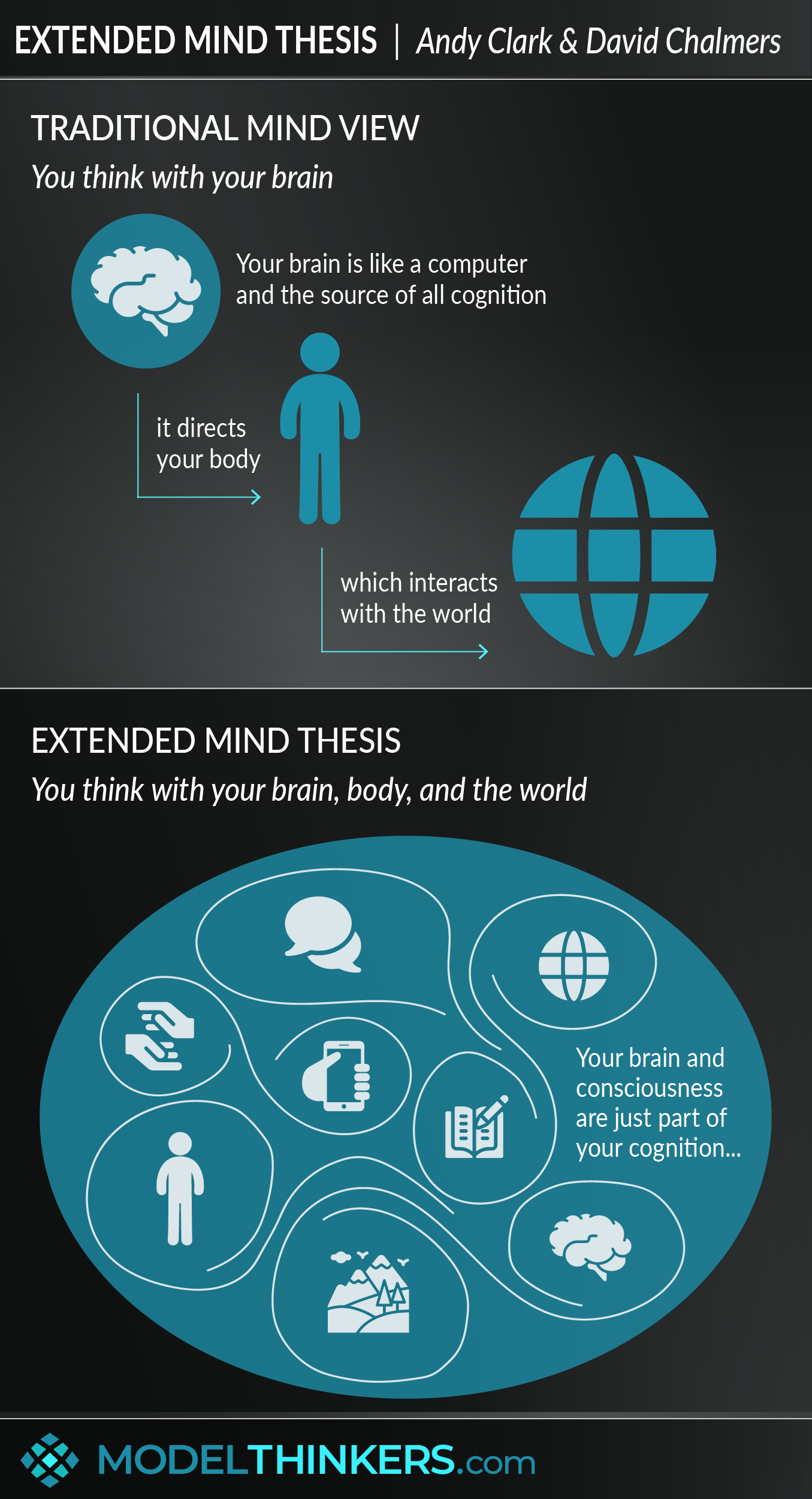

The Extended Mind Hypothesis: Your Phone Is Part of Your Brain

Back in 1998, two philosophers named Andy Clark and David Chalmers published a paper that seems almost prophetic today. They called it the "extended mind hypothesis," and it fundamentally challenges how we think about where cognition actually happens.

Here's the core idea: your mind doesn't stop at your skull. It extends outward into the tools and systems you use to think.

When you check your Notes app for a grocery list, you're not using a separate tool. You're not thinking separately from the app and then referencing it. Instead, you and the app form a single cognitive system. The information stored in the app is just as much part of your thinking process as neurons firing in your prefrontal cortex.

Same thing with Google Maps. You're not thinking separately from Maps and then consulting it. The map is part of your navigation cognition. It's part of how you think about space and direction.

Clark and Chalmers call this the "cognitive coupling." When a tool becomes sufficiently integrated into your regular thinking practices, it becomes part of your cognitive system. Full stop.

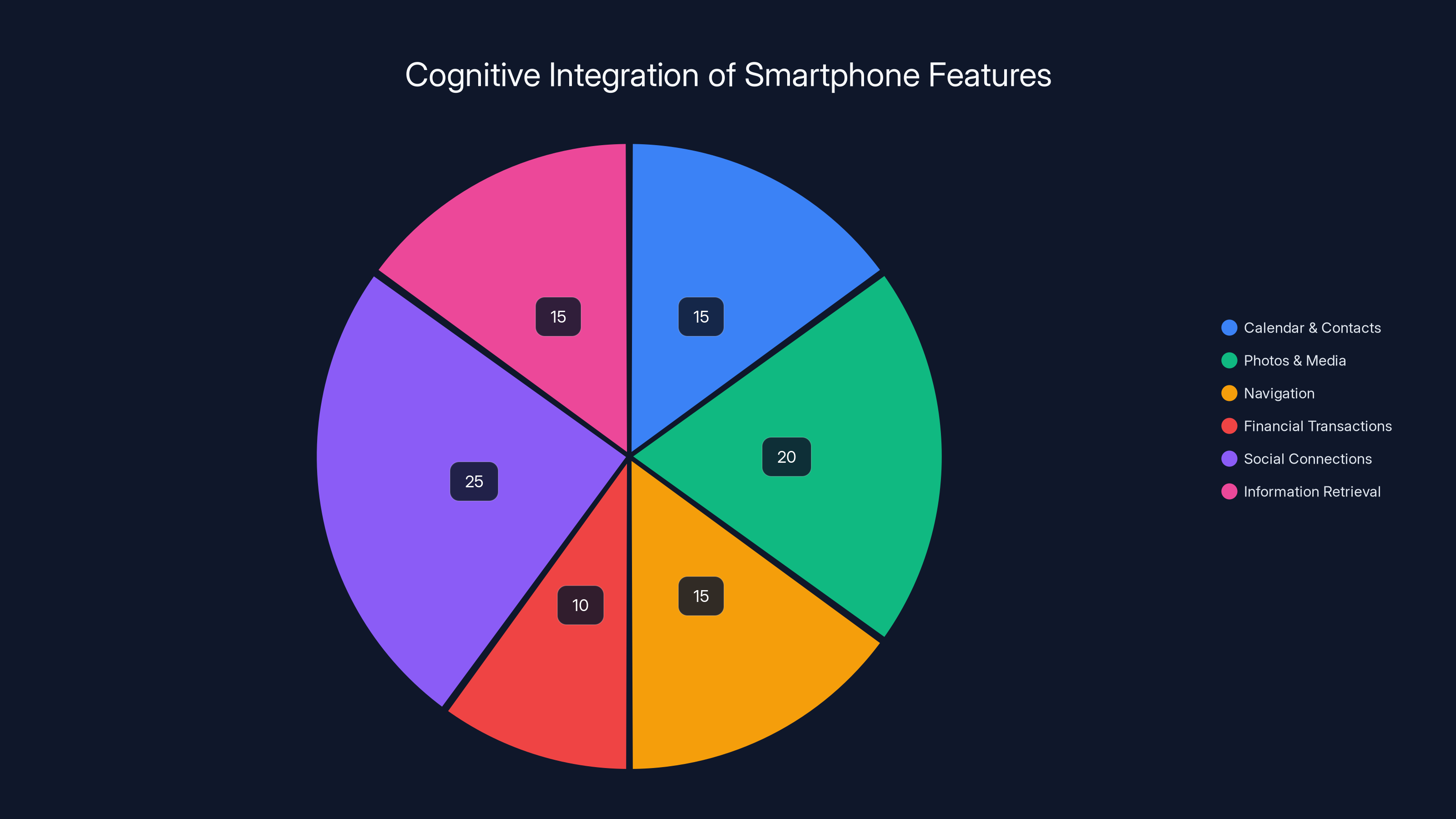

Now think about the average smartphone user in 2025. Your phone handles your calendar. Your contacts. Your photos. Your location. Your financial transactions. Your relationships. Your health data. Your work. Your entertainment. Your news. Your search queries.

This isn't theoretical integration. This is total cognitive merger.

For someone who grew up with a smartphone in their hand starting at age 14, this integration happened during the most neuroplastic period of your life. While your prefrontal cortex was still developing, while your neural pathways were being pruned and shaped and optimized, a smartphone was right there, reshaping how you think about memory, navigation, social connection, and information retrieval.

Your brain didn't just learn to use a smartphone. Your brain developed around the assumption that a smartphone would be there to handle certain functions. The neural pathways that would have specialized in remembering phone numbers? They never fully developed. The spatial reasoning that might have come from navigation without GPS? That got outsourced before it could fully form.

This is what Clark calls "cognitive offloading," and it's not inherently bad. Humans have always done this. We invented writing to offload memory. We invented calculators to offload arithmetic. We invented books to offload knowledge storage.

But there's a speed difference here. The integration happened fast. Really fast. In the span of 15 years, the smartphone went from an exotic luxury to a cognitive prosthetic that billions of people can't function without.

The crucial insight here is that Clark would emphasize: removing that external component doesn't just make you slightly less efficient. It drops your overall cognitive competence. "If we remove the external component," Clark and Chalmers write, "the system's behavioral competence will drop, just as it would if we removed part of its brain."

So when someone ditches their smartphone for a dumbphone, they're not just choosing to be less connected. They're actually choosing to be less cognitively capable.

And that's before we even get to memory.

Estimated data shows that social connections and photos/media are the most integrated smartphone features in cognitive processes by 2025, highlighting the deep cognitive merger between users and their devices.

Transactive Memory: Your Phone Is Your Memory

In 1985, a psychologist named Daniel Wegner introduced a concept that's even more unsettling than the extended mind hypothesis. He called it "transactive memory," and it explains how long-term couples actually function as a single memory system.

Wegner studied couples and found something fascinating: they didn't each maintain their own complete memories. Instead, they divided the labor. One person remembered dates. The other remembered names. One person knew the family history. The other knew how to fix things around the house. They created what Wegner called a "knowledge-acquiring, knowledge-holding, and knowledge-using system that is greater than the sum of its individual member systems."

Critically, Wegner noted that when one partner in a long-term couple dies, entire realms of shared knowledge just vanish. Not just emotionally. Literally. Memories that were stored in the couple's collective cognitive system are lost because they were never stored redundantly in individual brains.

Wegner's research was about romantic relationships, but the principle applies perfectly to our relationships with our devices.

Your smartphone has become your transactive memory partner. You don't remember phone numbers anymore because your phone does. You don't remember your friends' birthdays because your phone reminds you. You don't remember what you did last summer because your phone stores the photos. You don't remember how to get to places because your phone handles navigation.

The system works beautifully. Until it doesn't.

Consider what happens when you lose access to your phone, or when you switch phones without proper backup, or when you accidentally delete photos from a crucial period of your life. The memories associated with those experiences don't just become harder to access. They actually fade. You know intellectually that something happened. But you have no visceral memory of it. No specific images. No triggering details that bring the experience flooding back.

This is what happened to me during senior year of high school. I dropped my iPhone without backing up my recent photos. An entire semester of social milestones, road trips, and friend group moments simply vanished. I could tell you that these events happened. But I have no felt sense of them. They're blank.

And here's the scary part: that's not a bug. That's the system working exactly as designed. Your phone isn't just storing information about your memories. It's storing your memories themselves. The system assumes those memories will always be available.

So when someone switches to a dumbphone, they don't just lose access to technology. They lose access to their own memories. Not metaphorically. Literally.

The dumbphone users in the Gen Z movement aren't thinking about this. They're picturing themselves becoming more present, more mindful, more connected to the moment. They're not picturing the amnesia that comes with severing transactive memory partnerships.

The Cognitive Price of Going Dumb: What Actually Happens

Let's get practical. What happens when someone who's been deeply integrated with a smartphone for their entire adolescence suddenly switches to a dumbphone?

The first week feels amazing. No notifications. No algorithmic feed. No endless scroll. Your attention span immediately improves. You feel more present. You have real conversations without your phone buzzing on the table.

This is what dumbphone evangelists talk about. This is the narrative they share on TikTok and in interviews. And it's real. The attention benefits are immediate and genuine.

But then week two arrives, and something different starts happening.

You realize you have no idea where the coffee shop is without Google Maps. You've never actually learned that route because you've always just typed the address into your phone.

Someone asks for your friend's phone number and you can't remember it. You've never memorized it because your phone stored it in 2015.

You want to look up how to fix something, and you can't. Not because the information doesn't exist, but because accessing it requires a separate device. It requires friction. And more importantly, it requires conscious effort in a way that your smartphone never did.

Your memory of last week starts getting fuzzy. You can't find the photos. You didn't take notes. You didn't write anything down. The details just evaporate.

Your friends start getting frustrated because you can't coordinate plans as quickly. You're always ten minutes late because navigation is slower. You miss messages because your dumbphone doesn't have instant notifications.

Your professional competence takes a hit. You can't check your email on the train. You can't respond to work messages immediately. You can't reference documents you need. You're less available, less responsive, and frankly, less capable.

But the most insidious cost isn't any of these specific problems. It's the cumulative cognitive load.

When you had a smartphone, certain categories of thinking were outsourced. You didn't have to hold navigation details in your working memory. You didn't have to remember contact information. You didn't have to maintain your calendar mentally. Your cognitive resources were freed up to think about higher-level stuff.

With a dumbphone, all of that comes back. Your working memory suddenly has to hold navigation details. You have to consciously remember appointments. You have to maintain mental maps. Your cognitive resources get consumed by basic coordination tasks that a smartphone used to handle automatically.

Clark warned me about this when I asked him about it. "You're not just losing a tool," he said. "You're losing bandwidth." And the problem is that this bandwidth loss isn't uniformly distributed. It hits certain types of people harder than others.

If you're a knowledge worker who needs to coordinate with multiple people, manage complex projects, track information across different domains, the cognitive cost of ditching a smartphone is genuinely severe.

If you're someone with ADHD or executive dysfunction, the cost might be completely prohibitive. Your smartphone isn't a luxury. It's an assistive device. Going dumbphone means losing your external brain.

The dumbphone evangelists will tell you that this cognitive load is temporary. That you'll adapt. That your brain will rewire and develop new capabilities.

They're partially right. Your brain will adapt. But here's what they're not acknowledging: the brain that adapts isn't the same brain that developed with a smartphone integrated into it from age 14.

You're not returning to baseline. You're regressing to a cognitive state that your neural architecture never fully developed for.

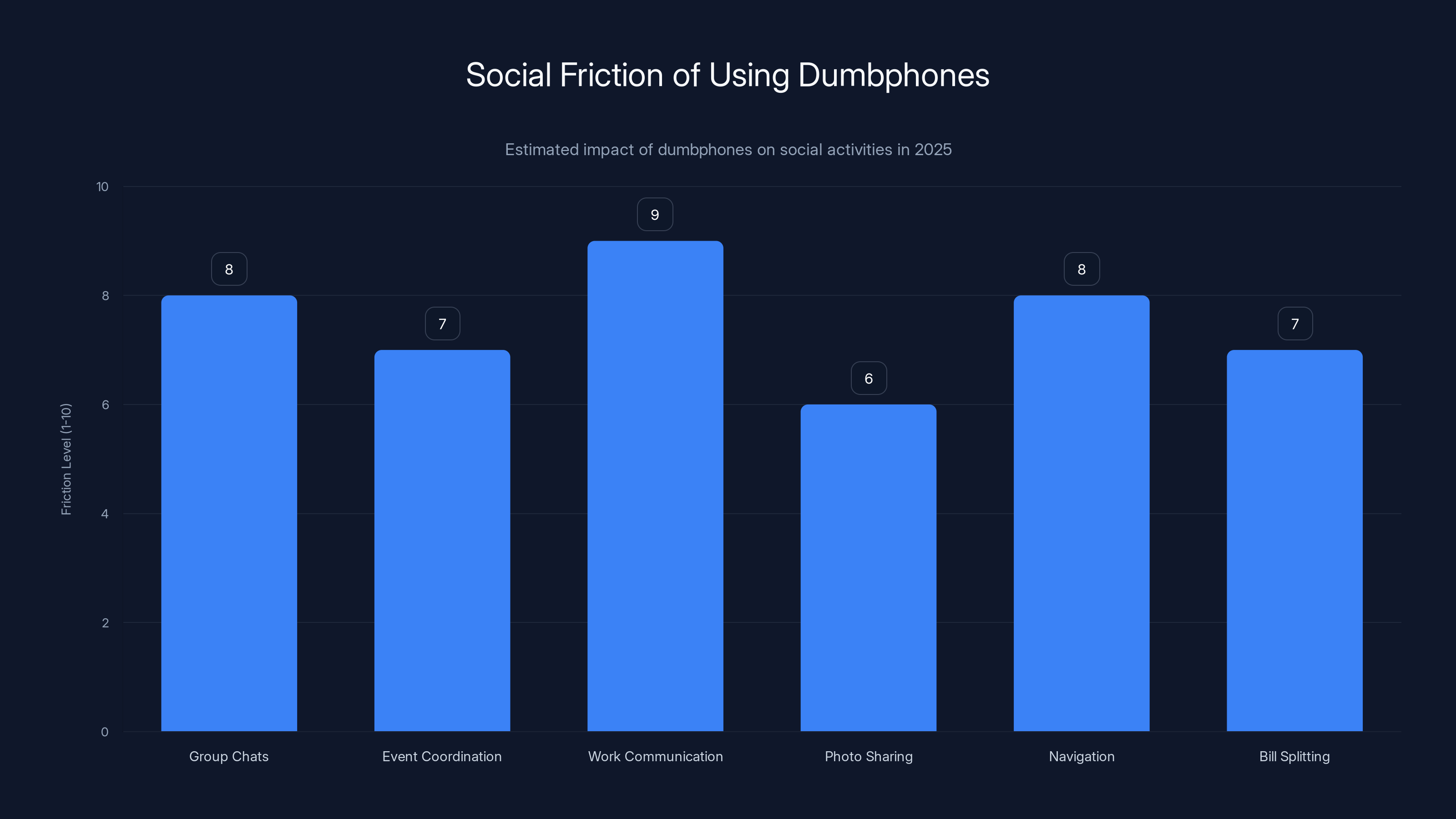

Dumbphones create significant social friction, especially in work communication and navigation, due to lack of integration with modern digital tools. Estimated data.

The Generational Mismatch: You Can't Unlearn a Brain

Here's where it gets really interesting, and frankly, a bit tragic.

People who grew up without smartphones have something that people who grew up with them don't: a fully formed set of offline cognitive skills. They can navigate without GPS. They can remember phone numbers. They can find information in books. They can navigate social coordination without instant messaging.

These aren't inherently superior skills. But they represent a fully developed cognitive architecture that doesn't require external offloading to function.

People who grew up with smartphones don't have that option. The critical periods of neural development happened with a smartphone already embedded in their cognitive system. The pathways that would have developed for offline navigation? They got pruned. The memory specialization for phone numbers? Never formed. The attention patterns for sustained reading without distraction? Shaped around the assumption that a notification might arrive at any moment.

Your brain didn't just learn to use a smartphone. Your brain developed assuming that smartphones would be there.

This is what neuroscientist Michel Haissaguerre calls "developmental neuroplasticity." During childhood and adolescence, your brain is building the scaffolding for how you think. If a smartphone is a crucial part of that scaffolding, the absence of that smartphone creates structural gaps.

So when a Gen Z person switches to a dumbphone, they're not just removing a tool. They're removing a fundamental part of how their cognitive architecture was built. They're trying to operate a brain that was developed for integrated technology using the constraints of a brain designed for pre-smartphone cognition.

It's like asking someone who learned to read on a computer to suddenly read exclusively on paper and expecting them to have the same experience. The neurological path is different. The eye movement is different. The cognitive processing is different. You can't just swap interfaces and expect everything to work the same way.

Some people will adapt. Some will have dramatic success with dumbphones and claim that their brains rewired completely. And maybe that's true for some small percentage of people who have unusual cognitive flexibility or who only lightly integrated with smartphones in the first place.

But for most people who grew up with smartphones as their extended cognitive system, the switch creates a genuine cognitive deficit.

And they're probably not going to acknowledge it because that would require admitting that they've lost something real. It's easier to frame it as gaining clarity and presence. It's harder to face the truth that you've actually become less cognitively capable in several important domains.

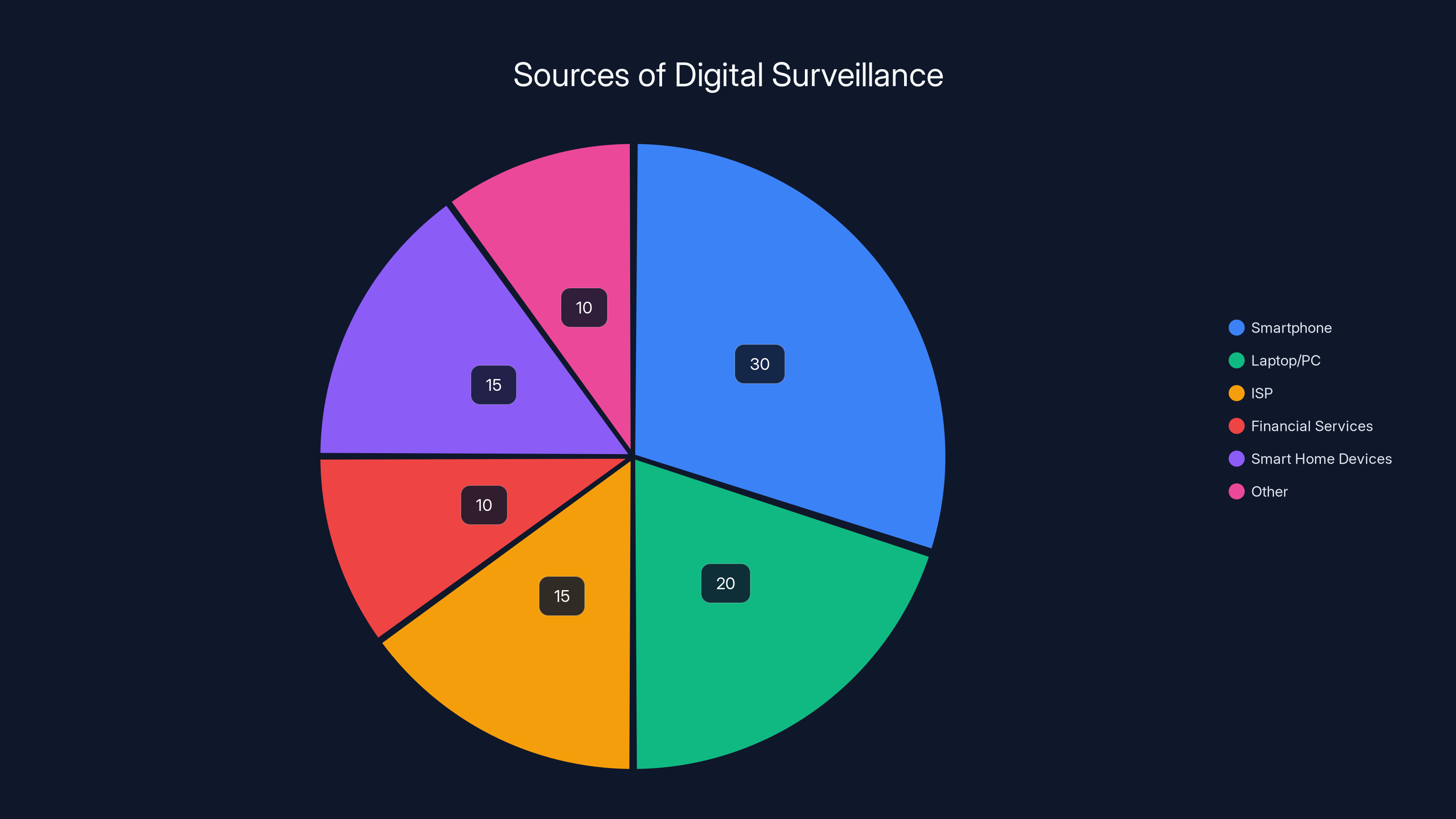

The Privacy Paradox: Why Ditching Your Phone Doesn't Actually Protect You

One of the biggest motivations for the dumbphone movement is privacy. Young people feel (correctly) that smartphones are surveillance devices. Your data is harvested. Your location is tracked. Your behavior is profiled. Ads follow you. You're the product.

Switching to a dumbphone feels like reclaiming privacy. No apps. No tracking. No corporate surveillance.

Except that's not really how it works.

First, your phone isn't the only surveillance vector. Your laptop tracks you. Your browser tracks you. Your ISP tracks you. Your bank tracks you. Your credit card company tracks you. Your fitness app tracks you. Your smart home tracks you. Your car tracks you. Your location data is sold by data brokers regardless of what phone you carry.

Second, and more importantly, switching to a dumbphone just transfers your digital identity to other platforms. You're not getting less tracked. You're getting tracked differently.

You still have email. You're still on social media on your computer. You're still using web services. You're still leaving digital traces. You're just not consolidating all of that tracking into one device.

In some ways, this might actually increase your overall vulnerability because your data is now spread across more fragmented systems with less integration and potentially less security.

But here's the real privacy paradox: the reason Big Tech wants your smartphone data isn't because they're villains. It's because your smartphone is the most intimate behavioral tracking device that exists. It knows everywhere you go. Everything you search for. Every person you contact. Every app you use. Every website you visit. Every moment when you pick it up.

That's incredibly valuable data. So companies built surveillance into smartphones.

But here's the thing: if you go dumbphone, someone else is going to build surveillance into something else. That's not a bug. That's how surveillance capitalism works. The medium might change, but the surveillance doesn't stop.

The real privacy solution isn't ditching your smartphone. It's understanding what data is being collected, demanding regulation, supporting privacy-focused tools, and making informed choices about what you're willing to share.

Switching to a dumbphone is like deleting your cookies instead of supporting privacy legislation. It feels like you're doing something, but you're not actually solving the problem.

Dumbphone users will tell you they feel more private. And subjectively, they might be right. They're not seeing their behavior profiled in real time by algorithmic systems. But objectively, they're probably not actually more private. They're just more invisible to one particular category of surveillance.

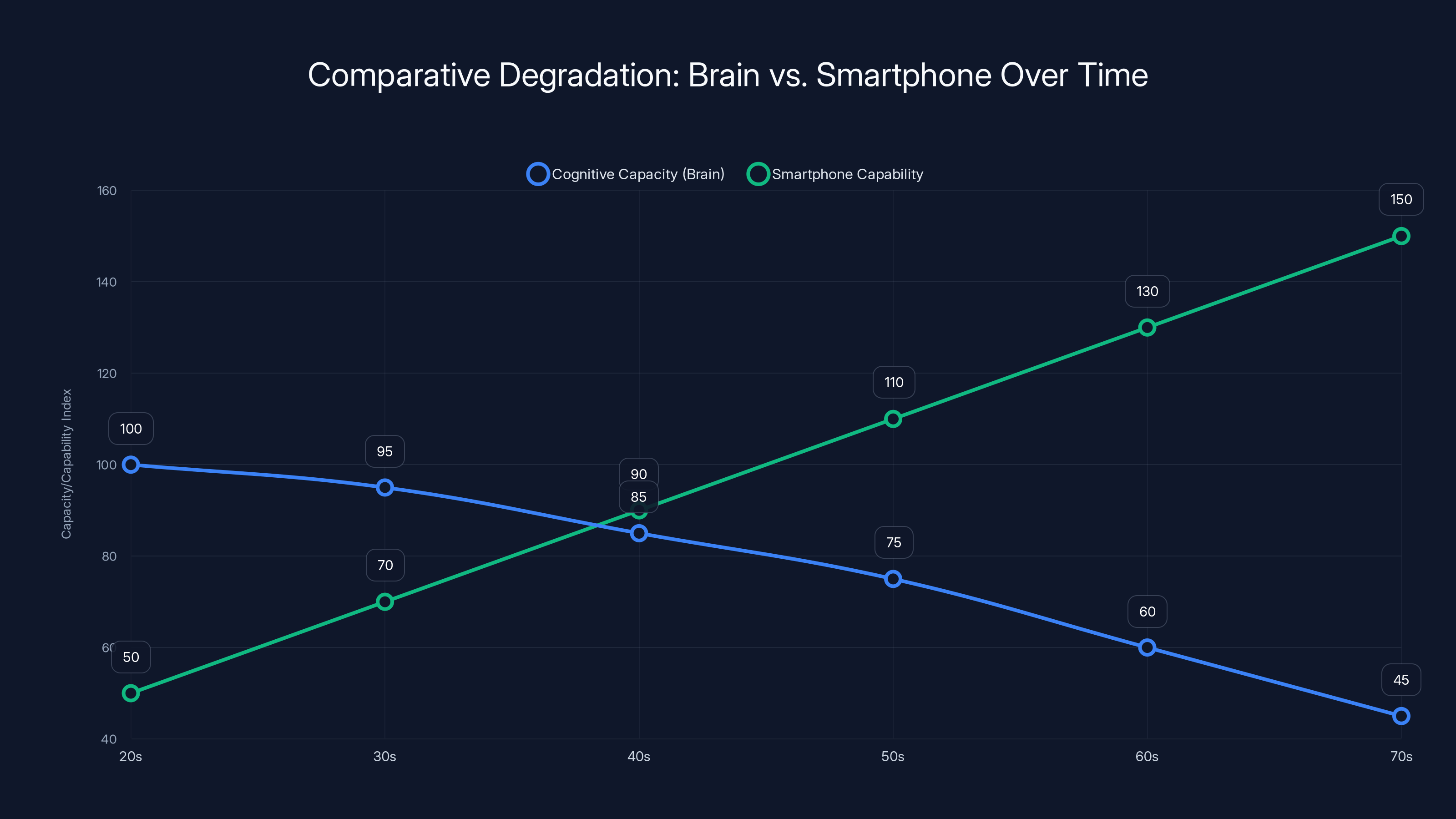

Estimated data shows cognitive capacity declines with age, while smartphone capabilities improve, widening the gap over time.

The Social Friction Problem: Dumbphones Don't Actually Fit Into Modern Life

Here's something dumbphone evangelists don't like to talk about: the social costs.

When you switch to a dumbphone in 2025, you're not just choosing a different device. You're choosing to opt out of how modern social coordination actually works.

Group chats? You're missing them. You might get a text, but you're not in the full conversation. When someone sends 15 messages over 10 minutes while you're busy, you're getting 15 separate text messages instead of one integrated chat.

Event coordination? Your friends send you a link to the event on Instagram or Facebook. You can't see it. Someone has to call you with details. This sounds nice and personal until it's the third time this week someone has to manually explain something to you that everyone else saw instantly.

Work communication? If your job has any level of digital coordination, you're immediately less capable. Slack? Nope. Email on mobile? Nope. Calendar integration? Nope. You're choosing to be slower and less responsive than everyone else.

Pictures with friends? Everyone else is taking photos and immediately sharing them to a group chat. You can take a photo, but you can't share it. You'll have to email it later if you remember.

Navigating with friends? Everyone else is using Google Maps and can see the route and how long it's taking. You're trying to navigate via written directions and a separate GPS device. You arrive 15 minutes late.

Splitting a bill? Venmo exists but not on a dumbphone. You either ask for cash or figure out later how to reimburse people from a computer.

Social friction is the price of opting out. And for Gen Z, which has never known a world without integrated mobile communication, that friction is genuinely severe.

Dumbphone users will frame this as a feature. "My friends call me instead of texting. We have real conversations!" That's great. But they're also the reason you're always late, always uninformed, always out of sync with group plans.

The dumbphone movement works in theory. In practice, it makes you harder to coordinate with. It makes you less reliable. It makes you the person everyone has to accommodate.

For people with a particular personality type (more introverted, more resistant to social pressure, more willing to be the unreliable friend), this might be acceptable. But for most people, the social friction becomes noticeable fast.

And unlike the cognitive benefits dumbphone users cite, the social friction doesn't disappear. It gets worse as more of your peers continue integrating with digital systems that you're now excluded from.

The Neuroscience of Attention: Are You Actually Less Distracted or Just Using Willpower?

One of the biggest claims from the dumbphone movement is that going dumb dramatically improves attention and focus.

And here's the thing: it kind of does. In the short term.

When you remove the notifications, the apps, the algorithmic feed, the infinite scroll, your attention span immediately improves. It's not imagination. Your prefrontal cortex isn't being constantly interrupted by dopamine hits. You can sustain focus on a single task for longer periods.

But here's what's really happening: you're not actually developing better attentional capacity. You're using willpower and artificial constraint to reduce the number of competing stimuli. That's different.

The moment you get access to a smartphone again, or the moment you return to digital systems that can interrupt you, those attentional abilities partially collapse. You haven't rewired your brain. You've just created a constrained environment.

Neuroscience research on attention shows that sustained attentional improvements require active practice and neural development. You have to train your brain to focus. Just removing distractions is the equivalent of removing weights from a barbell and then claiming you've gotten stronger. You've gotten better at lifting, but only because you've removed the load.

Dumbphone users often report that after a few months, their attention span has permanently improved. That they can now read books without checking their phone. That they can focus on conversations.

But controlled research on phone use and attention suggests something different: attention improvements from phone removal typically plateau after a few weeks, and many of those improvements are lost if you return to smartphone use.

What might be happening instead is that dumbphone users are getting real benefits from the reduced algorithmic pressure, the reduced social media consumption, and the reduced notification interruptions. But those benefits don't come from dumbphones specifically. They come from using their digital devices less.

You could get the same benefits from an iPhone with ruthless app deletion, notification settings disabled, social media deleted, and conscious usage patterns. You don't need a dumbphone. You need discipline.

But discipline is harder than just buying a Nokia brick and pretending your brain has fundamentally rewired.

Smartphones account for the largest share of digital surveillance, but other devices and services also contribute significantly. Estimated data.

The Reliability Problem: Your Brain Is Fragile, Your Phone Is Fragile, But One Degrades Faster

Here's an argument that Andy Clark made that really stuck with me, and it's kind of a dark one.

Clark pointed out that brains can fail. You could have a stroke. You could develop dementia. You could get Alzheimer's. Your biological memory system is not a reliable backup for your external system. In fact, it's often less reliable.

So from a pure reliability standpoint, outsourcing your memory and navigation and scheduling to a smartphone might actually be smarter than keeping it in your potentially-degrading biological brain.

Now, yes, smartphones can break. They can be lost. They can be stolen. They can be dropped in the toilet.

But here's the crucial difference: when a smartphone breaks, the data usually doesn't die. It's backed up to the cloud. It's recoverable. A new phone can be set up with your data in minutes.

When your biological brain degrades, that capacity doesn't come back. You don't get a new prefrontal cortex. You don't get a backup of your memories. You lose what you lose.

So from a pure resilience standpoint, the integrated cognitive system (you + smartphone) might actually be more resilient than the offline alternative (just you).

Clark also noted something else I hadn't considered: the trajectory of these systems is completely different.

Your brain will decline over your lifetime. Cognitive capacity peaks in your late 20s and then gradually decreases. Memory gets worse. Processing speed gets slower. Your biological hardware has a clear trajectory downward.

Smartphones are getting better. They're getting faster, smarter, more capable. The software that makes your iPhone uniquely yours lives in the cloud, theoretically forever. The processing power available on a phone is increasing exponentially.

So the reliability and capability gap between your brain and your external system is going to widen over your lifetime. Not narrow. Widen.

Going dumbphone means accepting that you're going to become increasingly disadvantaged as your brain degrades and as digital systems become more capable and more integrated into modern life.

It's not a romantic choice. It's a choice to become less capable as you age.

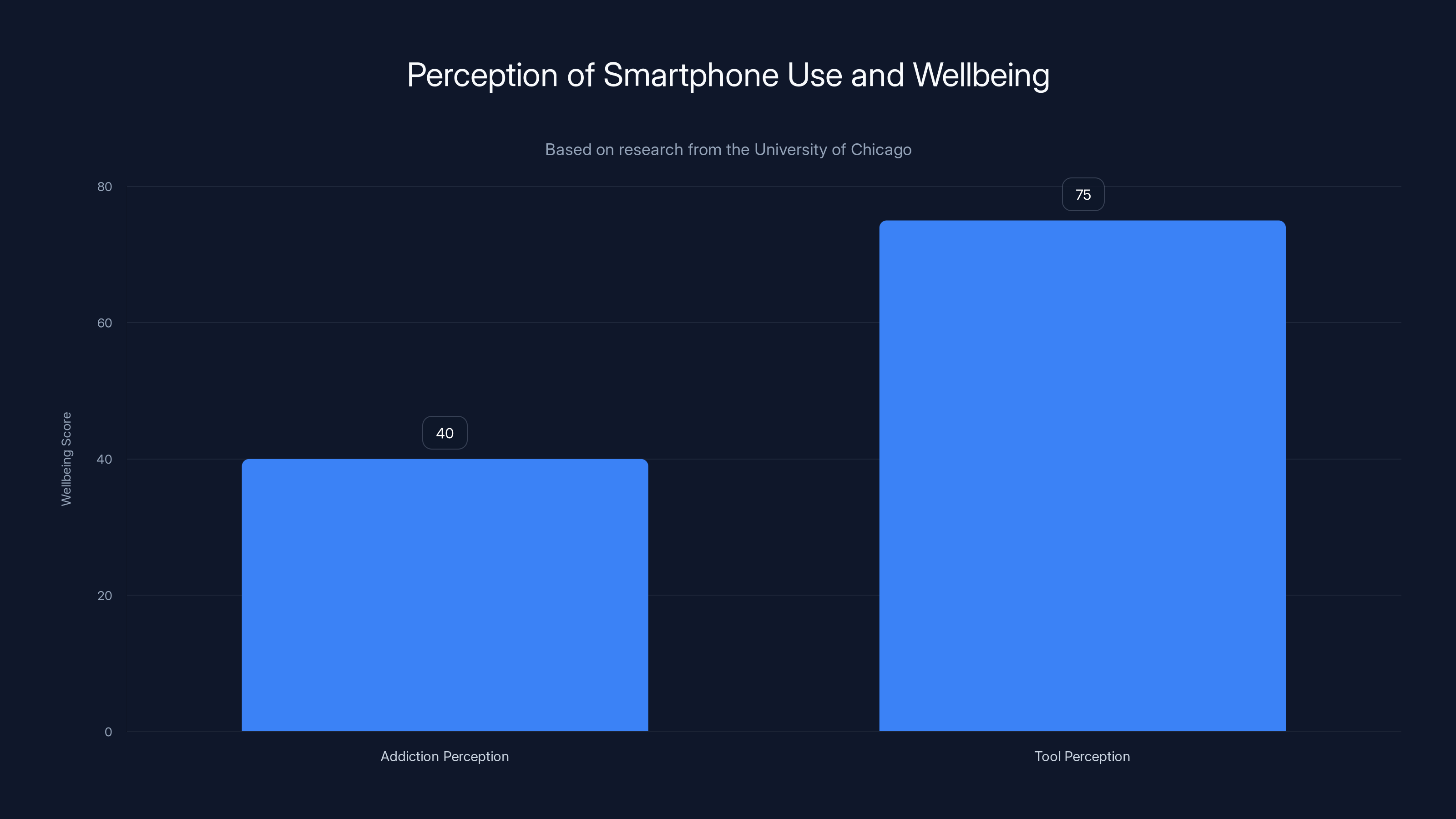

The Addiction Myth: Is Your Smartphone Addiction or Integration?

The dumbphone movement is often framed around addiction. People talk about smartphone addiction like it's nicotine or alcohol. Like they're trying to quit a substance.

But here's the thing: addiction language might be fundamentally wrong here.

Addiction implies pathological use of something that doesn't serve your interests. You know cigarettes are killing you, but you smoke anyway. That's addiction.

But smartphone use isn't like that. Yes, algorithmic feeds are designed to be compulsive. Yes, notifications are designed to interrupt you. Yes, social media is built to maximize engagement.

But the actual core functions of a smartphone serve your interests. Navigation serves you. Communication serves you. Information access serves you. Calendar management serves you. Photography serves you.

You're not addicted to your smartphone. You're integrated with it. You're dependent on it in the same way you're dependent on language or writing or electricity.

The fact that social media is exploitative and uses addictive design patterns doesn't make the entire device addictive. It makes specific apps exploitative.

So the framing of dumbphones as a solution to addiction is slightly dishonest. It conflates the genuine harms of algorithmic social media with the basic utility of having your external cognitive system integrated into your pocket.

A more honest framing would be: "I'm frustrated with algorithmic social media, and I'm using a dumbphone as a hammer to solve this problem, which is going to break a lot of other things in the process."

But that doesn't fit the narrative of digital detox and reclaiming your mind.

People who perceive their smartphone use as a 'tool' report higher wellbeing scores compared to those who see it as an 'addiction'. (Estimated data)

The Environmental Contradiction: Dumbphones Require More Stuff

Here's a bit of dark irony that the dumbphone movement doesn't often acknowledge: switching to a dumbphone usually means you need more separate devices.

You need a phone. But you also need a camera for photography. You need a GPS device for navigation. You need a music player. You need a computer for everything else.

Or you need to carry around a smartphone for specific situations (travel, emergencies, work), which means you're maintaining two devices instead of one.

From an environmental standpoint, this is arguably worse than just using one integrated smartphone.

Smartphones are incredibly efficient devices from a resource perspective. One device handles dozens of functions. A dumbphone approach requires multiple separate devices, more power adapters, more batteries, more mining of rare earth metals, more e-waste.

If you actually care about environmental impact, the dumbphone approach is probably the wrong direction.

Now, you could argue that you'll use your existing devices for photos and navigation, not buy new ones. But that's just a different framing of exactly what I described earlier: you're still dependent on smartphones for basic functions. You're just not carrying one. Your smartphone dependence hasn't changed. Your approach to managing it has.

The Selective Memory Problem: What Dumbphone Users Forget About Pre-Smartphone Life

There's a psychological bias called "rosy retrospection." It's the tendency to remember the past as better than it actually was.

The dumbphone movement seems affected by this. Dumbphone users talk nostalgically about the 1990s and early 2000s. More human connection. Real conversation. Face-to-face interaction. No algorithms determining what you saw.

All of that's partly true. But the selective memory is real too.

In the 1990s, you couldn't find information instantly. You had to go to a library. You had to spend hours researching something that takes 30 seconds to Google now.

You couldn't navigate without a paper map, which was often out of date. You couldn't coordinate plans with more than 3-4 people easily because communication was slow.

You couldn't stay in touch with friends from high school after college because that required intentional effort and phone calls, which were expensive.

You couldn't document your life or share experiences with people you care about. You took film photos and waited a week to see if they turned out.

You couldn't get emergency help as quickly. You couldn't call 911 from anywhere.

Yes, there were real benefits to that era. But there were also real costs that the dumbphone movement romanticizes away.

Pre-Smartphone life wasn't actually better. It was different. Some things were easier. Some things were harder. Some human connections were richer because they required deliberate effort. Other connections were impossible because the friction was too high.

The dumbphone movement is basically choosing to reintroduce that friction while forgetting why the friction existed in the first place.

The Compromise Position: Digital Minimalism Without Dumbphones

Here's what I think is the more honest approach for people who are genuinely frustrated with their smartphone use:

Stop pretending the solution is to go dumbphone. The solution is to use your smartphone more intentionally.

Delete social media apps from your phone. Disable notifications for everything except calls and messages from your contacts. Turn off your wifi at certain times. Set screen time limits. Use app blockers.

These are boring solutions. They don't look cool on TikTok. They don't give you the narrative of being the "person who ditched technology."

But they actually work. And they don't require you to create artificial friction in every basic coordination task.

You keep your extended mind integration intact. You keep your transactive memory partnership with your device. You keep your social coordination capabilities. You keep your reduced cognitive load.

But you eliminate the specific design patterns that are exploitative.

Is it as dramatic as going dumbphone? No. Is it as good a story? No. Does it satisfy the same ideological impulse? Sort of, but less pureistically.

But it's actually sustainable. Most dumbphone users eventually go back to smartphones because the friction is too high. The few who don't are either ideologically committed to a form of technological asceticism or they actually do have lower social coordination needs than average.

For most Gen Z users, the compromise position is the realistic one.

Looking Forward: The Future of Cognitive Integration

Here's what fascinates me about the dumbphone movement: it's a reaction to a real problem (exploitative social media, attention hacking, data surveillance) by choosing a technological regression that solves a different problem entirely.

The actual problems with smartphones aren't the smartphones themselves. They're specific design patterns built into specific apps. They're surveillance capitalism's business model. They're the outsourcing of attention capture to algorithmic systems.

None of those problems get solved by switching to a dumbphone. You just disconnect from one vector of exploitation while remaining connected to others.

The real future of cognitive integration isn't dumbphones. It's more thoughtful smartphones. It's regulatory frameworks that protect user attention and data. It's design patterns that don't exploit behavioral psychology. It's transparency about how your data is being used.

It's the recognition that external cognitive integration is here to stay, and it's the framework of the future, so we might as well design it thoughtfully instead of pretending we can go back to pre-integration cognition.

Because we can't. That option closed when 14-year-olds started getting iPhones. That option closed when neural pathways developed with the assumption of external systems. That option closed when we fused our biological and technological cognition into a single system.

The dumbphone movement is a beautiful aesthetic and a comprehensible reaction to real problems. But it's ultimately a fantasy. It's the fantasy that you can undo technological integration. That you can reclaim a simpler brain. That you can go back.

You can't. None of us can. So the question becomes: what do we do with the integration we've already created? How do we redesign these systems to serve us instead of exploit us?

That's the more challenging question. That's the one the dumbphone movement is avoiding. But it's the only one that matters.

FAQ

What exactly is the extended mind hypothesis?

The extended mind hypothesis, developed by philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers in 1998, proposes that your mind doesn't end at your brain. External tools like notebooks, maps, and smartphones become part of your cognitive system when they're integrated into your thinking process. When you check Google Maps for directions, that's not a separate action from thinking about navigation; it's part of how your navigation cognition works. Your smartphone has become so embedded in how you think, remember, and navigate that it functions as an extension of your biological brain.

How does transactive memory work with smartphones?

Transactive memory describes how you store knowledge collectively with another system. Just as couples distribute information storage between each other (one remembers dates, one remembers names), you and your smartphone distribute cognitive functions. Your phone stores photos, so you don't store detailed visual memories. Your phone stores contacts, so you don't memorize numbers. The system works beautifully until that device is lost, broken, or absent. When that happens, entire realms of memory simply vanish because you never stored that information redundantly in your biological brain.

What are the real cognitive costs of switching to a dumbphone?

When you switch from a smartphone to a dumbphone, your cognitive load increases across multiple domains simultaneously. Navigation requires active working memory instead of outsourced GPS. Scheduling requires you to hold appointments in your head. Information searches require deliberate effort rather than instant access. Social coordination becomes slower because group messaging requires friction. Most dramatically, you lose the ability to instantly access your external memory (photos, notes, information). Your biological brain has never fully developed the neural pathways to replace these functions because they've been outsourced since your teenage years.

Is it possible to rewire your brain after smartphone integration?

Your brain can adapt to new constraints, but it can't fully rewire the developmental scaffolding that was built with smartphone integration. During adolescence, your brain's neural pathways pruned and optimized around the assumption that certain functions would be externally offloaded. These aren't just habits that can be broken; they're architectural features of how your neurological system developed. You can adjust to using a dumbphone, but you'll be operating with a cognitive architecture that was designed for smartphone integration, operating under dumbphone constraints. Some people adapt successfully, but most experience a measurable reduction in overall cognitive competence.

Does a dumbphone actually improve privacy more than using a smartphone carefully?

Not really. Switching to a dumbphone transfers your data collection to different systems rather than eliminating it. You're still tracked through your email, laptop, internet browsing, banking, and digital services. Your location data is still sold by data brokers. You haven't gained privacy; you've just shifted your tracking vectors. A more effective approach is using privacy-focused settings on your smartphone, deleting social media apps, and supporting privacy regulation. The real solution to surveillance capitalism isn't dumbphones; it's policy and design changes that protect user privacy systemwide.

What's the difference between smartphone addiction and smartphone integration?

Addiction implies pathological use of something harmful that you can't stop using despite negative consequences. Smartphone integration is dependency on a system that genuinely serves your needs and is embedded in your cognitive architecture. Some apps (social media) use addictive design patterns, but the smartphone itself isn't inherently addictive; it's integrated. You're not addicted to navigation or calendar management or communication. Framing normal smartphone use as "addiction" conflates the genuine harms of exploitative design patterns with basic technological integration. The real problem isn't the device; it's specific apps and design choices.

Can you have smartphone benefits without the drawbacks by using digital minimalism?

Absolutely, and this is often more sustainable than switching to a dumbphone. By deleting social media apps, disabling notifications, setting screen time limits, and being intentional about your smartphone use, you can eliminate the exploitative design patterns while keeping your extended mind benefits intact. You maintain your navigation capability, your communication efficiency, your external memory access, and your social coordination. You just cut out the specific design patterns that are attention-hacking and exploitative. This approach is boring compared to "I quit my smartphone," but it's actually sustainable for most people.

What happens to relationships and social coordination if you use a dumbphone?

Dumbphone users experience significant social friction in modern life. Group chats are harder to participate in. Event coordination requires manual explanation instead of instant link sharing. Work communication becomes slower if your job uses Slack or similar tools. Splitting bills becomes awkward. Shared photo experiences are disrupted because you can't instantly share images. You become the person everyone accommodates instead of someone who's integrated into group communication systems. For people with lower social coordination needs, this might be acceptable. For most Gen Z users who've organized their entire social lives around instant group communication, the friction is severe.

Does the attention improvement from dumbphones actually last?

The attention improvement from dumbphone use is real but often temporary. Your focus immediately improves when you remove notifications and algorithmic feeds, but you're not actually developing better attentional capacity; you're using environmental constraint to reduce competing stimuli. Research suggests these improvements plateau after a few weeks and often reverse if you return to smartphone use. Most "permanent" improvements likely come from reduced algorithmic social media and reduced notifications, which you could achieve on a smartphone with careful settings without losing all other functionality.

Is the pre-smartphone era really better than people remember?

No. Rosy retrospection leads dumbphone users to romanticize the 1990s and early 2000s while forgetting the friction and costs. Pre-smartphone life required hours of research for information that takes 30 seconds to find now. Coordination required expensive phone calls and fragmented communication. You couldn't document your life or easily stay in touch with people. Emergency services were slower to reach. Friendships from high school often ended because maintaining them required deliberate effort that was too high. Navigation was slower and often inaccurate. The era wasn't better; it was different with different tradeoffs that dumbphone advocates often forget.

What's the most sustainable approach to smartphone concerns?

The most sustainable approach is digital minimalism on a smartphone rather than switching to a dumbphone. Delete exploitative apps (social media), disable notifications for everything except high-priority contacts, set screen time limits, use app blockers during work or focus time, and be intentional about when you use it. This eliminates specific design patterns that are exploitative while keeping your extended mind benefits, your social coordination capability, and your reduced cognitive load. It's less dramatic than dumbphones and doesn't produce good social media content, but it's actually sustainable and doesn't create unnecessary friction in modern life.

Conclusion: The Uncomfortable Truth About Going Dumb

The dumbphone movement represents something real and important: a genuine frustration with how technology companies have designed systems to exploit human attention and behavior. That frustration is completely valid. The surveillance capitalism business model is predatory. Algorithmic feeds are intentionally addictive. Your data is being harvested and monetized. All of that is true and deeply problematic.

But the dumbphone solution, while aesthetically appealing and ideologically satisfying, doesn't actually solve these problems. It solves a different problem: it disconnects you from one vector of exploitation. But it creates new problems in the process. It introduces friction into coordination. It reduces your cognitive competence. It makes you less capable in multiple important domains. It disconnects you from social systems that people around you depend on.

More importantly, it's built on a fundamental misunderstanding of how your brain has actually changed. You can't unintegrate. You can't go back. The cognitive architecture developed with a smartphone as an extension of your biological brain is permanent. Switching to a dumbphone doesn't remove that enmeshment; it just adds constraint on top of it.

So what's the actual move?

First, recognize that smartphone integration is real and probably permanent for anyone who grew up with one. You're not going to rewire your brain back to pre-smartphone cognition, and that's actually fine. External cognitive tools have been part of human civilization since writing was invented.

Second, stop blaming the device for problems that are actually caused by specific design choices. Your smartphone isn't the problem. Social media's addictive design is the problem. Notification hijacking is the problem. Algorithmic feeds that maximize engagement instead of user wellbeing are the problem. Data collection and profiling are the problem.

Third, solve those specific problems instead of burning down the whole device. Delete social media apps. Disable notifications. Turn off algorithmic feeds. Support privacy regulation. Use privacy-focused services. Make intentional choices about where your attention goes.

Fourth, recognize that the dumbphone movement, while sympathetic, is ultimately a luxury for people who can afford to opt out of modern systems. If you have a job that requires constant availability, you can't go dumbphone. If you need to coordinate with multiple people, you can't go dumbphone. If you have ADHD or executive dysfunction, a dumbphone might genuinely harm your functioning. For people in those situations, the movement's framing of dumbphones as the enlightened choice feels preachy.

And finally, understand that the future isn't dumbphones. The future is more thoughtful, more privacy-conscious, less exploitative smartphones. The future is regulation that protects user attention. The future is design patterns that serve users instead of manipulating them. The future is transparency about data collection and algorithmic recommendation.

The dumbphone movement is a reaction to a real problem. But it's a reaction that misdiagnoses the disease and prescribes a solution that creates new problems. The actual work is harder. It's about designing better systems. It's about demanding accountability from tech companies. It's about supporting privacy-focused alternatives. It's about being intentional with technology instead of either rejecting it entirely or surrendering to its exploitative design.

That work is less dramatic than buying a Nokia brick. But it's the only work that actually matters.

Key Takeaways

- Smartphones aren't external tools anymore; they're extensions of your cognitive system through the extended mind hypothesis

- Your brain's neural pathways developed WITH smartphone integration, making true disconnection neurologically impossible

- Transactive memory means losing your phone means losing actual memories stored in the device, not just convenience

- Dumbphone users face real social friction and reduced competence in modern coordination systems

- Digital minimalism on a smartphone achieves most dumbphone benefits without creating unnecessary cognitive and social costs

Related Articles

- Why Quitting Social Media Became So Easy in 2025 [Guide]

- Focused Work in a Distracted World: Stay On Task [2025]

- iPhone 18 Pro Design Leak: New Colors & Changes [2025]

- Samsung Galaxy S26 Leak: What We Know About Pro & Edge Models [2025]

- Importing Chinese Smartphones: Complete Guide [2025]

- Clicks Communicator Phone: The Keyboard-Driven Device Explained [2025]

![The Dumbphone Paradox: Why Gen Z Can't Actually Quit Smartphones [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-dumbphone-paradox-why-gen-z-can-t-actually-quit-smartpho/image-1-1768822639977.jpg)