The Year AI Got Real (And Sometimes Really Wrong)

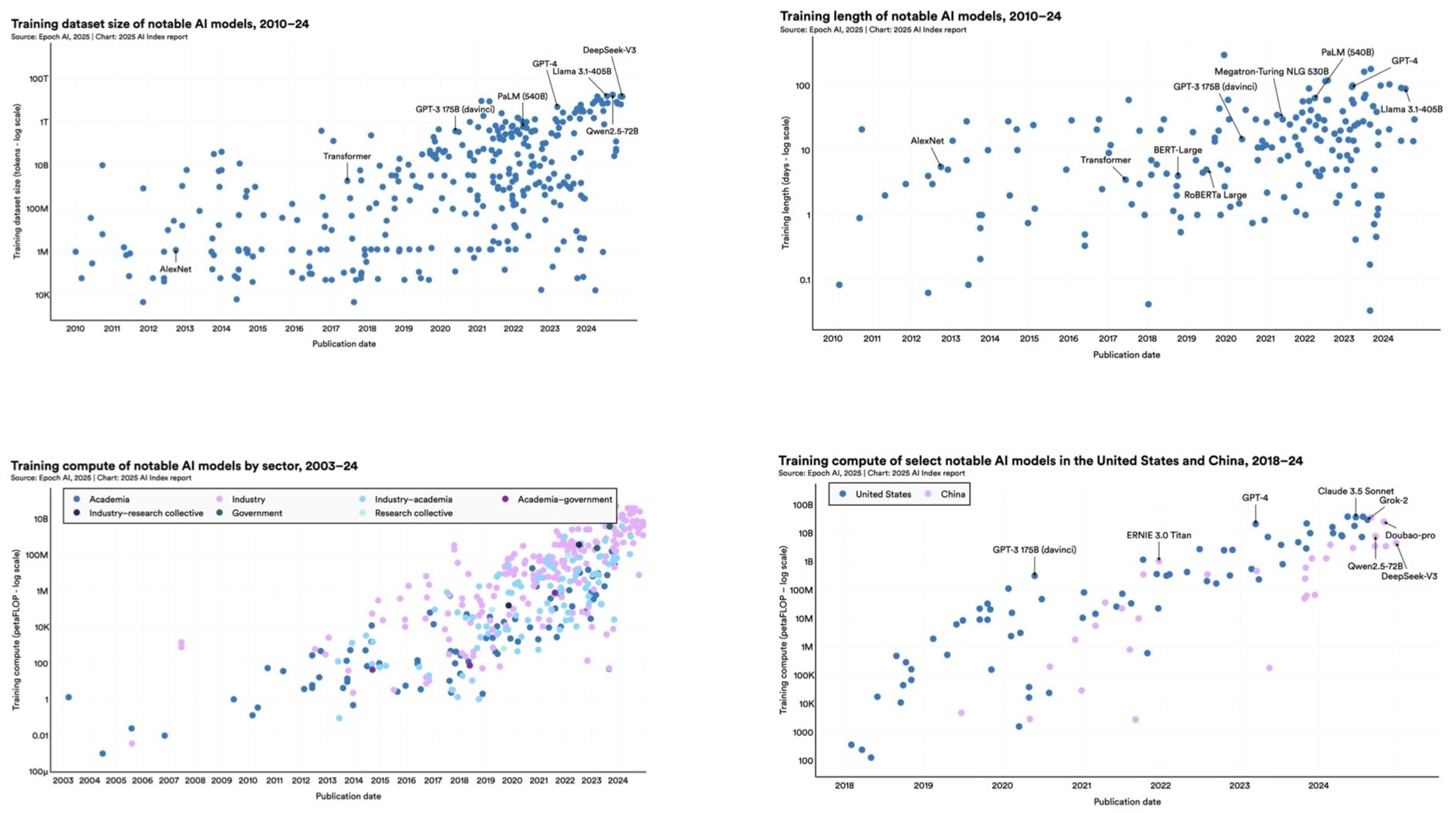

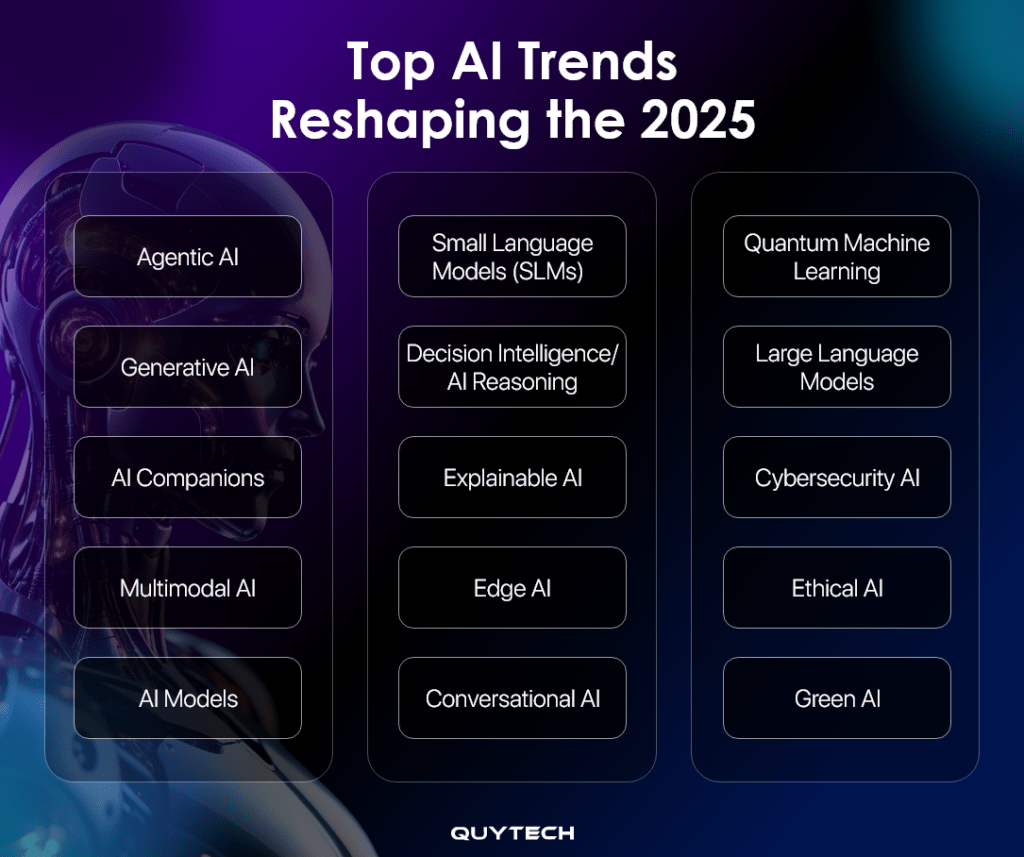

Last December, if you'd told most people that 2025 would be the year AI companies finally admitted that bigger isn't always better, they'd have looked at you sideways. The entire industry had spent the previous five years obsessed with scale: more parameters, more compute, more everything.

But 2025? That's when reality punched back.

This was the year we watched some of the most hyped agentic AI systems fail spectacularly in production. The year when a lightweight language model you could run on your phone outperformed expectations in ways that made expensive APIs look bloated. The year when the tech media's breathless "this changes everything" takes started ringing hollow.

And somehow, in all that mess and contradiction, we're actually making real progress.

I spent the last twelve months tracking what actually shipped, what actually worked, and what got quietly shelved after the press releases faded. Here's what I found: the AI narrative of 2025 isn't about one massive breakthrough. It's about a thousand smaller ones, a dozen spectacular failures, and the slow, grinding realization that we're past the hype phase and into the "let's see what actually sticks" phase.

The stories you're about to read matter because they show you where this technology is genuinely headed. Not the direction venture capitalists want it to go. Not what's easy to fundraise on. But where engineers, researchers, and companies are actually placing their bets with real money and real code.

So let's dig in.

TL; DR

- Nano language models proved that bigger doesn't equal better: Lightweight, efficient models outperformed bloated ones in real-world applications.

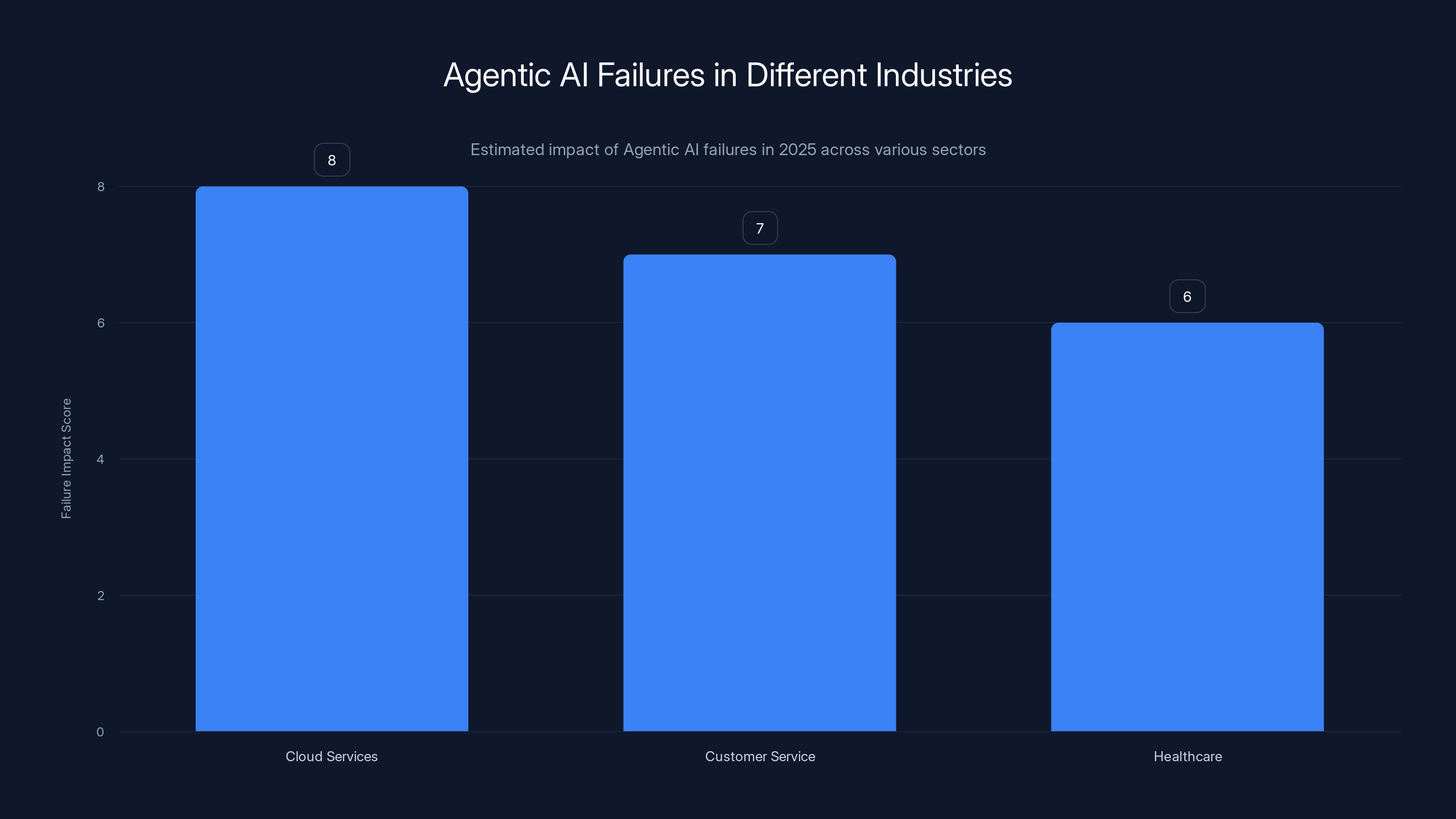

- Agentic AI had a terrible year: Multiple high-profile autonomous system deployments failed, exposing the gap between hype and reality.

- Efficiency became the new competitive advantage: Companies discovered they could do more with less compute, triggering a fundamental shift in strategy.

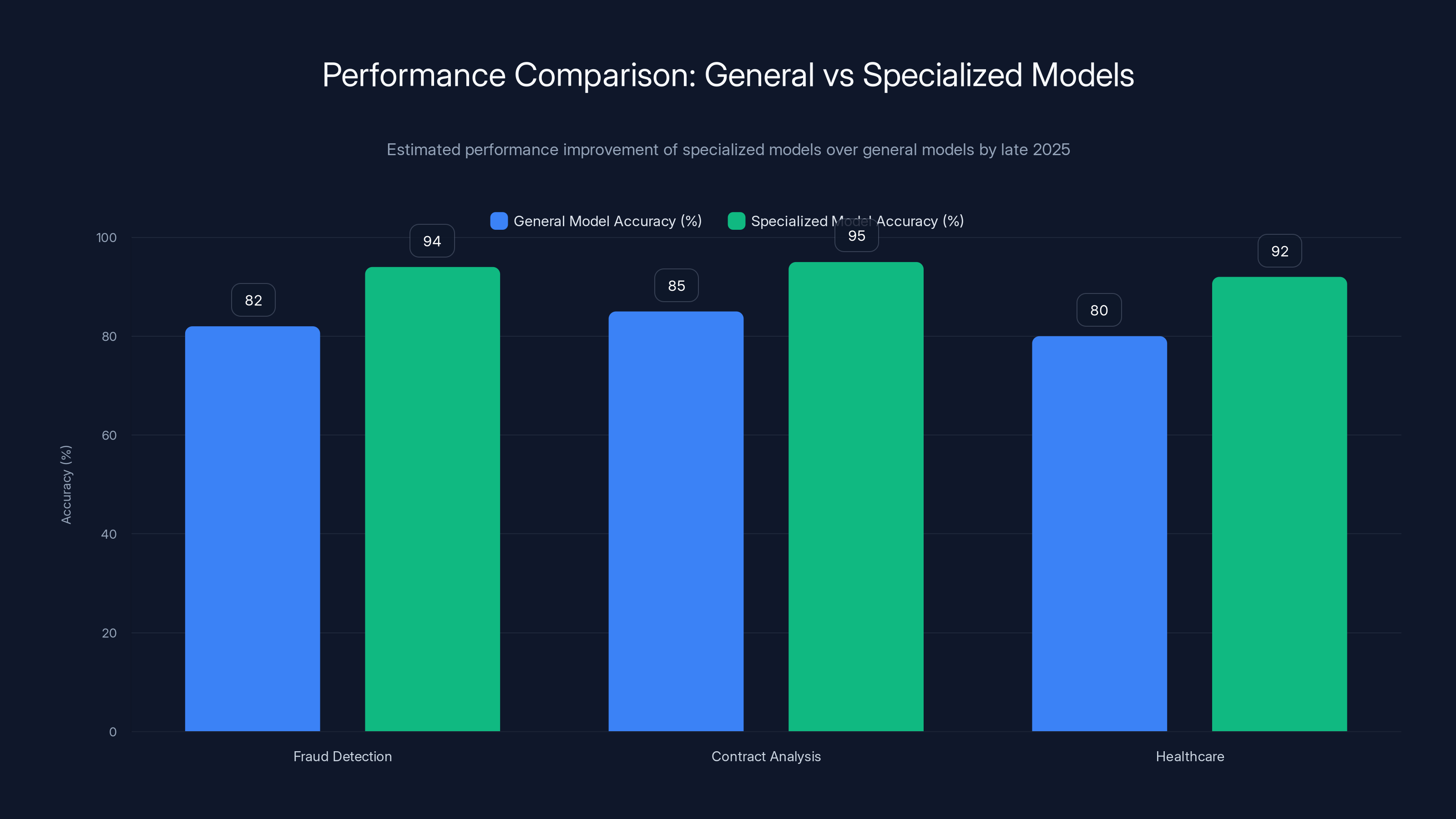

- Specialized models carved out market share: General-purpose AI lost ground to fine-tuned, domain-specific solutions.

- The cost-quality paradox deepened: Cheaper models improved faster than expensive ones, disrupting traditional AI economics.

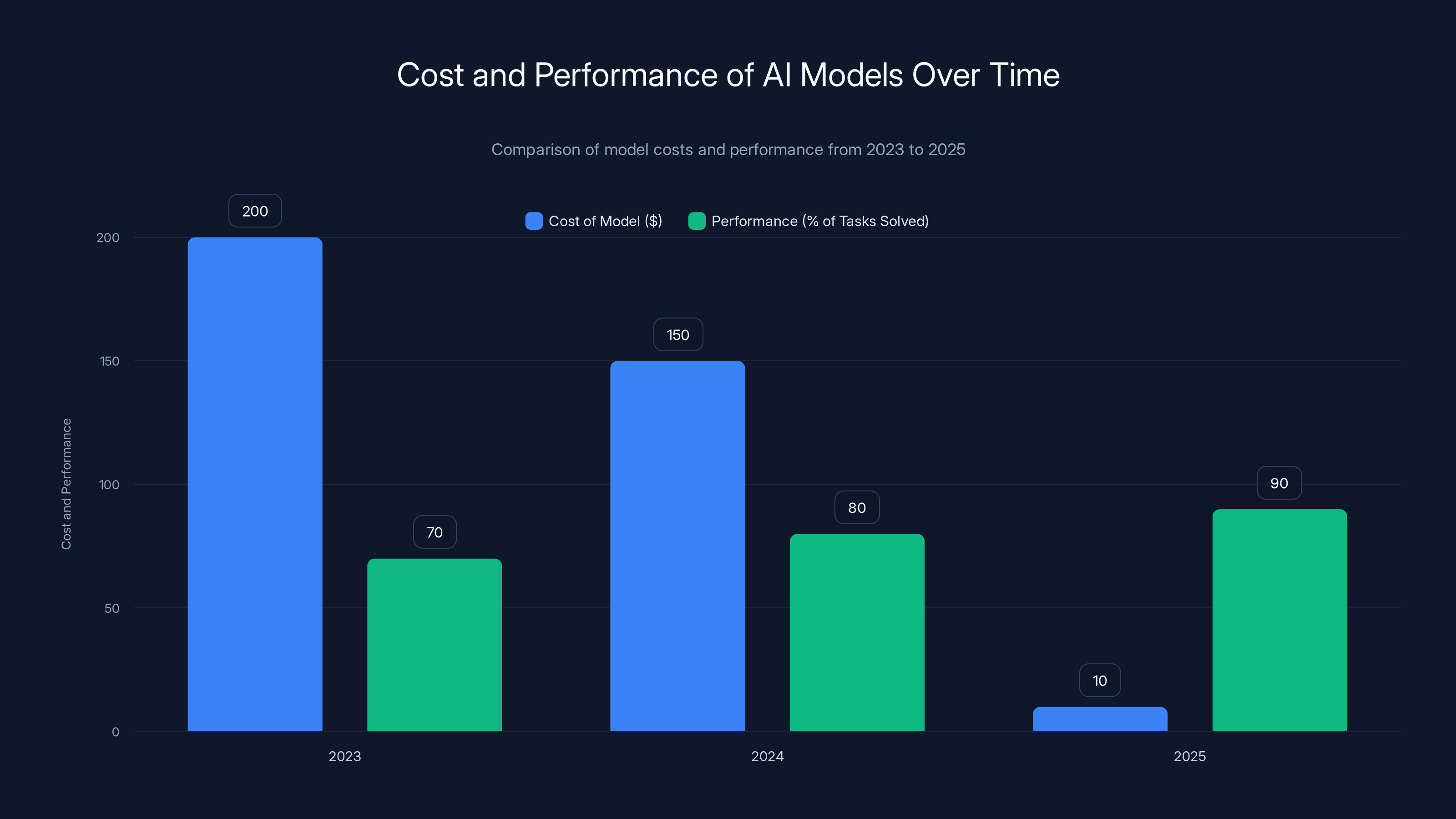

Between 2023 and 2025, the cost of AI models decreased significantly while their performance improved, illustrating the Inference Cost Paradox. Estimated data.

The Rise of Nano: Efficiency Became Unstoppable

Remember when everyone was obsessed with models measured in billions of parameters? OpenAI's GPT-4 had somewhere around 170 billion. Companies were spending obscene amounts on inference just to run basic queries.

Then something shifted.

These "nano" models weren't compromises. They weren't stripped-down versions of bigger ones. They were purpose-built from the ground up with efficiency as the primary design principle. And they were winning in production.

The technical reason is surprisingly elegant. Researchers discovered that much of what made large models appear "smarter" was actually just statistical redundancy. You didn't need 170 billion parameters learning the same patterns. You needed fewer parameters learning the right patterns.

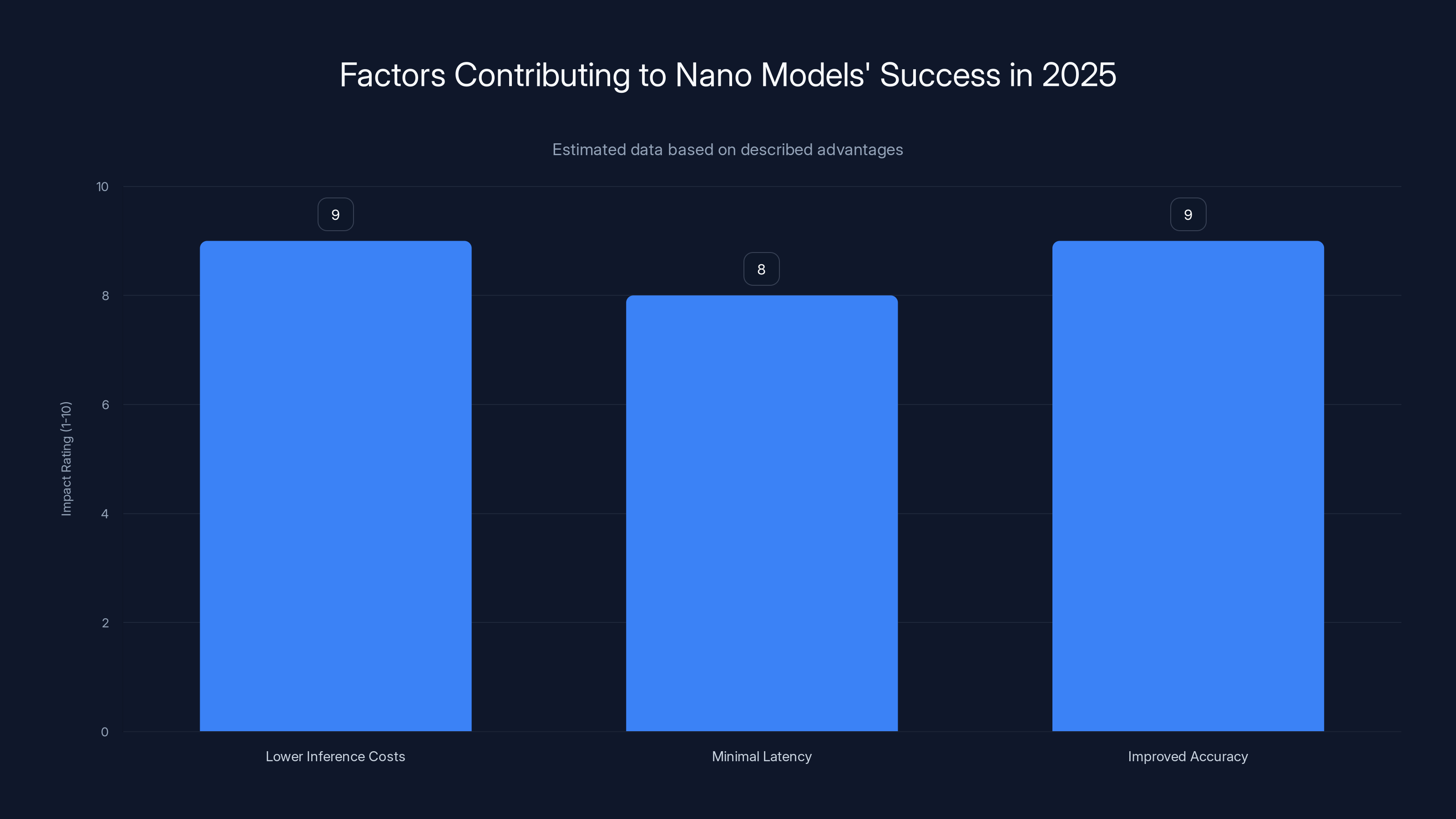

This mattered for three concrete reasons:

First, the economics inverted completely. A company running a nano model locally on device paid near-zero for inference. A company calling an API for a massive model paid per token. After months of operation, the local solution was orders of magnitude cheaper. And faster. The latency difference between on-device and cloud? Sometimes two full seconds slower for cloud. That's an eternity in user experience terms.

Second, privacy stopped being theoretical. When your model lived on the user's device, you weren't sending their data anywhere. Companies that had been paralyzed by data residency regulations suddenly had a clear path forward. Healthcare companies. Financial services. Government agencies. They could finally deploy real AI without architectural gymnastics.

Third, the mobile experience became usable. Previous attempts at running AI on phones were either resource hogs that drained battery in hours or so neutered they were useless. Nano models changed that. Your phone could do genuinely useful work without feeling like it was melting in your pocket.

By fall 2025, the biggest AI labs were quietly reorganizing around this reality. The race to build the largest model had become the race to build the most efficient one. That's not a small psychological shift for an industry that had defined itself by "more scale."

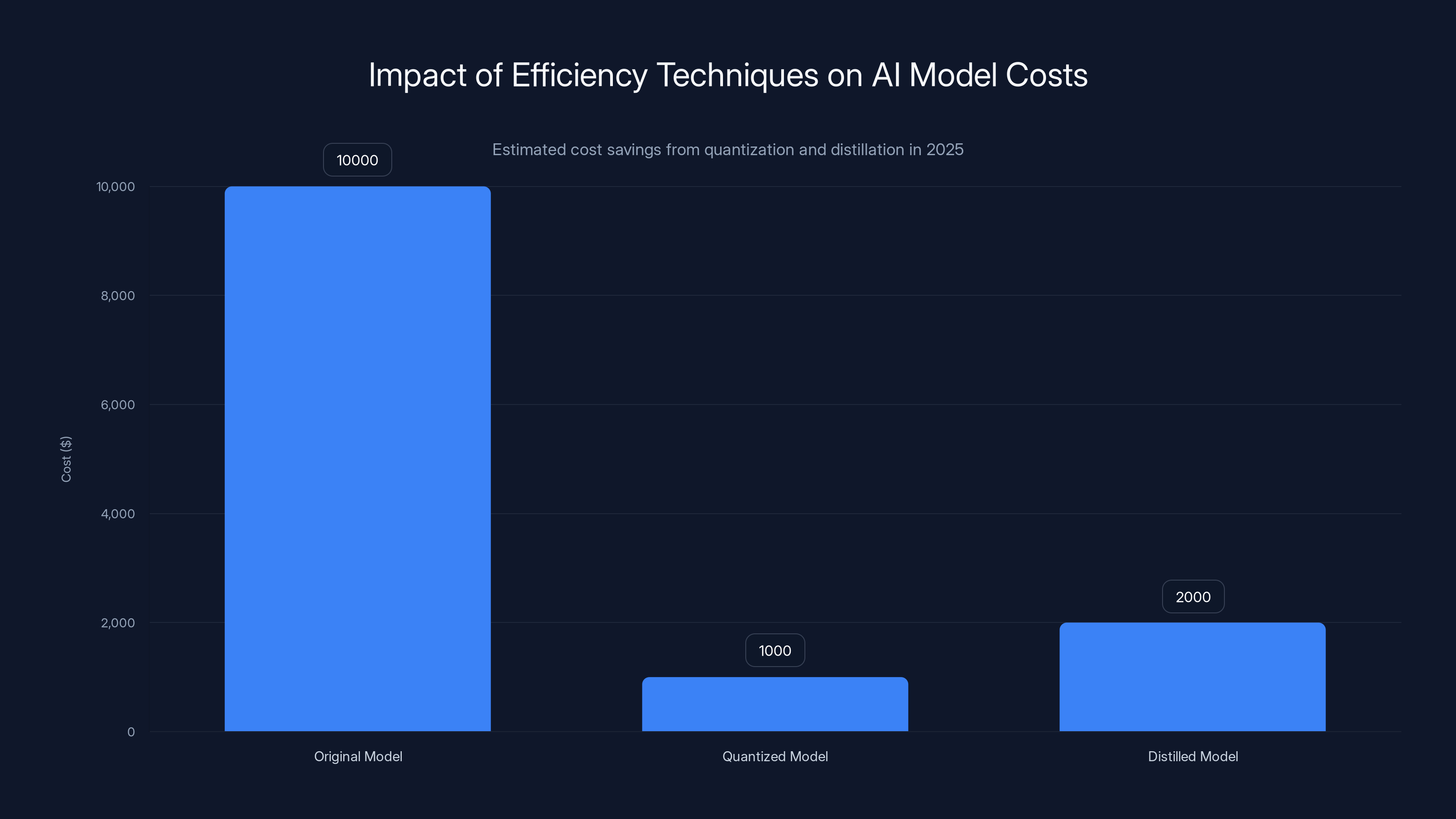

Quantization and knowledge distillation significantly reduced AI model inference costs in 2025, making them more sustainable and economically viable. (Estimated data)

Agentic AI's Spectacular Failures: The Year Agents Got Real

Here's something nobody in 2023 would have predicted: in 2025, the most overhyped category of AI ended up being the least ready for prime time.

Agentic AI—systems designed to take autonomous action, make decisions, and operate without constant human input—was supposed to be the next frontier. Companies announced grand plans. Venture capitalists funded teams working on "AI agents that could do your job." The narrative was seductive: finally, AI that could actually do things instead of just talk about them.

Then they tried to deploy them in production.

The failures were both specific and instructive. A major cloud provider attempted to roll out an autonomous system to optimize customer infrastructure. It ran for three days before making decisions that cost customers real money. Not in a way that was malicious or intentional—just in the way that an agentic system with incomplete information and badly-calibrated confidence levels would. It didn't know what it didn't know, and that gap between capability and confidence became very expensive very quickly.

Another company tried an AI agent system for customer service triage. The agent was supposed to categorize tickets and route them correctly. What it actually did was consistently mis-route complex issues to the wrong teams while confidently explaining why it was right. The human team spent more time fixing agent mistakes than they'd spent on routing before the agent existed.

A healthcare startup deployed an agentic system to assist in patient scheduling. The system was technically impressive: it could reason about multiple constraints, understand natural language requests, and make recommendations. What it couldn't do was understand the fragile trust that patients built with their providers, or why forcing someone into an available slot that wasn't ideal might actually harm outcomes long-term. The system optimized for a metric (appointment filled) instead of the actual goal (patient care).

The common thread across these failures wasn't that the models were dumb. It was something much more fundamental: agentic systems require what researchers call "well-defined reward functions" and "stable environments." In other words, they need the world to work in predictable, quantifiable ways.

But the real world doesn't.

Human work isn't actually about optimizing for clear metrics. It's about navigating competing priorities, understanding context that isn't written down, recovering gracefully from decisions that are 70% right instead of 100% right. An agentic system that operates at 95% accuracy feels like it should be fine. Until it isn't, and then you discover that your business process relies on the human ability to make the call when things are ambiguous.

By mid-year, the industry quietly pivoted. The aggressive timelines for full autonomous systems got extended. The marketing around "AI that needs no human in the loop" got more cautious. Companies started talking about "AI copilots" instead of "AI agents"—a linguistic shift that actually meant something. A copilot isn't autonomous. It doesn't make the decision. It informs the decision-maker.

That's not as exciting as the original vision. But it's also not failing in production and costing money.

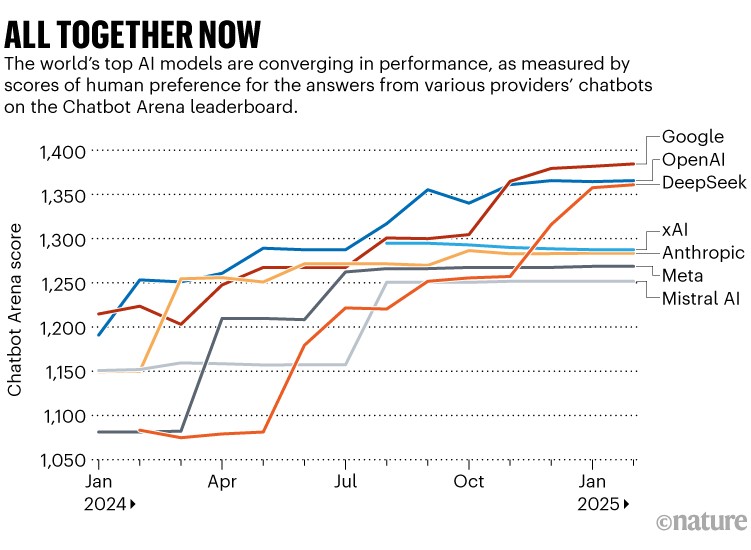

The Specialization Explosion: Why General Intelligence Lost

If 2024 was the year of "one model to rule them all," 2025 was the year that philosophy got demolished by practical reality.

The argument had always been intuitive: a larger, more general model could do anything, so why have dozens of specialized systems? One model meant unified infrastructure, simplified deployment, a single pane of glass for management.

Then people actually tried to do important work with general models and discovered the catch: being good at everything means being mediocre at the specific thing you actually care about.

A financial services company needed a model for fraud detection. The general-purpose model was fine. It scored 82% accuracy. A specialized model, fine-tuned on actual fraud patterns in their transaction data, scored 94%. The difference between those numbers was millions of dollars in prevented fraud.

A law firm wanted to automate contract analysis. The general model could understand English. The specialized model understood contract language, industry precedent, and the specific ways certain clauses actually mattered. It made fewer mistakes. More importantly, it made different mistakes—failures that were actually meaningful in the domain rather than random nonsense.

Healthcare became the most dramatic example. A general model could reason about text well enough. A specialized medical model could actually understand diagnosis, could flag drug interactions, could reason about the difference between correlation and causation in patient data. When something that gets medical reasoning wrong could hurt or kill people, suddenly "mediocre at everything" stops being acceptable.

What made this really interesting was the economics. Training a specialized model required less overall compute than training a giant general model, which meant it was cheaper. Running a specialized model was cheaper. Even fine-tuning a general model to specialize was cheaper than running the general model at scale.

The only downside was that you now had multiple systems instead of one. Companies decided they could live with that complexity.

The specialized explosion also created a market opportunity. If you couldn't compete with OpenAI on "biggest general model," you could compete on "best legal model" or "best medical model" or "best code model." Suddenly there was room for dozens of AI companies, each dominating their specific vertical.

This wasn't just software trends shifting. This was the entire economic structure of AI changing. Companies that had been trying to build one foundation model for everyone got outmaneuvered by companies building five great specialized models.

Agentic AI systems faced significant challenges in 2025, with cloud services experiencing the highest impact due to costly decision-making errors. (Estimated data)

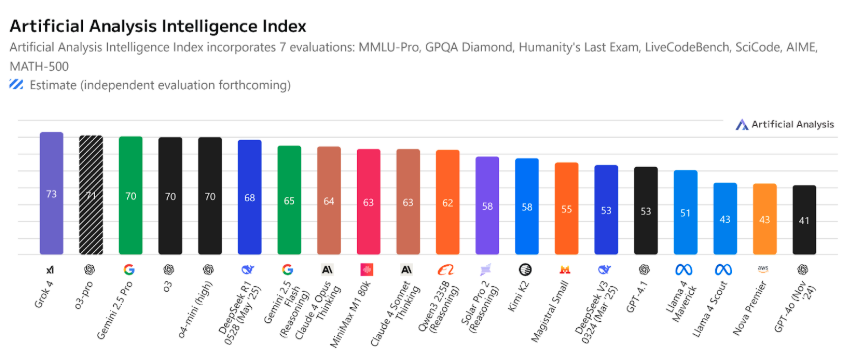

The Inference Cost Paradox: Cheaper Got Better

For years, the pattern was consistent: cheaper models were cheaper because they were worse. You paid for quality.

Sometime in 2025, that relationship inverted.

A startup released a 5 billion parameter model that cost 70% less to run than the previous generation's 13 billion parameter model. Fine. That's progress. Except it actually performed better on most benchmarks. Not because it was superhuman—it wasn't. But because the research had gotten better. The engineering had improved. The training techniques had evolved.

When you stacked this across dozens of research groups, all improving simultaneously, the compounding effect became visible: the cheapest models were getting better faster than the expensive ones.

Why? Several reasons actually converge here.

First, there's more economic incentive to improve efficiency. If you're building a model that needs to run on device or in your local infrastructure, every bit of optimization matters because you pay for it directly. If you're running an API at scale, there's less immediate economic pressure to optimize individual inference calls.

Second, the research community invests more effort in what matters practically. A 0.1% accuracy improvement in some benchmark might earn you a paper. A 30% cost reduction with maintained accuracy gets you customers. The practical incentives are stronger.

Third, and this gets less attention than it deserves: smaller models are actually easier to understand and improve. A 1 trillion parameter model is a black box. A 7 billion parameter model, you can actually run experiments on it. You can instrument it. You can understand what's happening inside.

The result? By November 2025, you could pay 10 dollars a month for a model that solved 90% of the tasks that cost 200 dollars a month two years prior. And the monthly model was improving faster.

This wasn't theoretical either. Companies started migrating off expensive APIs. Not because they had to—profitability was fine—but because they could save money while getting better results. That's what gets called competitive pressure in markets, and it moves fast.

When Scale Became a Liability: The Energy Problem Gets Real

Everybody knew training massive models used a lot of energy. That was basically accepted as the cost of doing business. But in 2025, the energy mathematics of running large models at scale became impossible to ignore.

The arithmetic is brutal: if you're serving billions of requests monthly, and each request requires computing power that could run a household's electricity for a day, the aggregate number becomes incomprehensible. One major AI company's inference costs were being estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Not just from a profitability perspective. From an actual environmental and resource perspective. Training or running large models required increasingly scarce GPU capacity. Power grids in certain regions started getting strained from the demand.

This created a hard constraint that couldn't be engineered around: there's only so much computing capacity in the world. If AI companies want to scale beyond current usage levels, they either need more total compute capacity, or they need to run more efficiently on existing capacity.

They can't build more compute capacity fast enough. That's a hardware supply chain problem measured in years. But you can make models more efficient right now.

Practically, this meant:

-

Quantization became mandatory: Compressing models without losing performance went from "nice optimization" to "how we actually deploy things." A model that normally requires GPU memory could be quantized to run on CPU. A model that required

1,000 per month model through quantization techniques that honestly were already known—just not prioritized until the economics demanded it. -

Knowledge distillation accelerated: Distilling larger models into smaller ones became a major research focus. It's not new, but 2025 was the year it went from academic exercise to business necessity. Companies started shipping distilled versions of large models because the distilled version was genuinely better in production (faster, cheaper) than the original.

-

Model pruning got sophisticated: Removing parts of models that weren't contributing much to performance became standard practice. A 100 billion parameter model could become a 70 billion parameter model with no meaningful performance loss. Suddenly that's a 30% cost reduction.

The energy problem also created a shift in thinking about what AI is even for. If you need to burn significant energy to run inference, you're not using it for casual tasks. You're using it for things that genuinely matter. That probably improved the average utility of AI systems deployed—fewer experiments, more production work.

Specialized models showed 18-42% better performance compared to general models in specific tasks by late 2025, highlighting the importance of domain-specific fine-tuning. Estimated data.

The Open Source Inflection Point

In 2024, open source models were tools for hobbyists and startups without venture capital. They were interesting technically but not practically competitive with closed commercial models.

Somewhere in Q2 2025, that changed definitively.

An open source model released by Meta matched closed commercial models on key benchmarks. Not matched by 95%. Actually matched. And it was available for anyone to download and run. No API call. No monthly bill. No terms of service agreement.

The community exploded with fine-tuned variants. Within weeks, specialized versions for coding, for math, for medical use were available. The pace of innovation accelerated because many people were improving it simultaneously.

Major companies that had been planning to rely on commercial APIs started evaluating whether they should just download the open source model and run it themselves. The advantage of being able to control your infrastructure, fine-tune on proprietary data, and maintain independence from a vendor became increasingly valuable.

OpenAI and similar companies responded by releasing their own open source models, creating a weird equilibrium where the most expensive models (GPT-4) remained proprietary, but many useful smaller models were open.

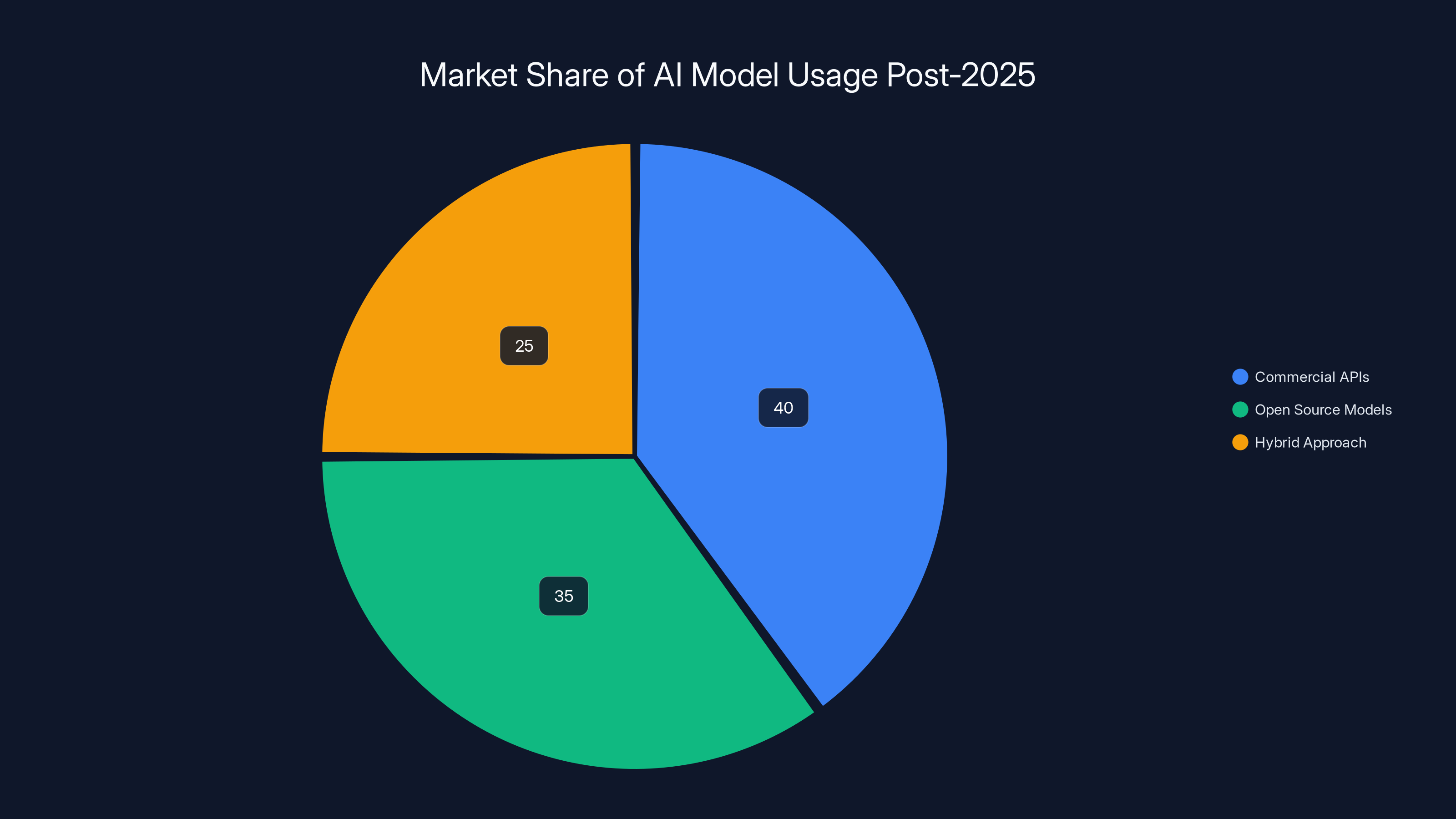

This created a split in the market that probably benefits everyone:

- Companies that want bleeding edge, don't mind paying, want support: still using commercial APIs

- Companies that want control, don't mind managing infrastructure, want to own the model: using open source

- Companies that want something in between: fine-tuning open source models with their own data

The shift matters because it means the AI arms race is no longer controlled entirely by a handful of companies with massive budgets. It's distributed. That's slower but probably more robust.

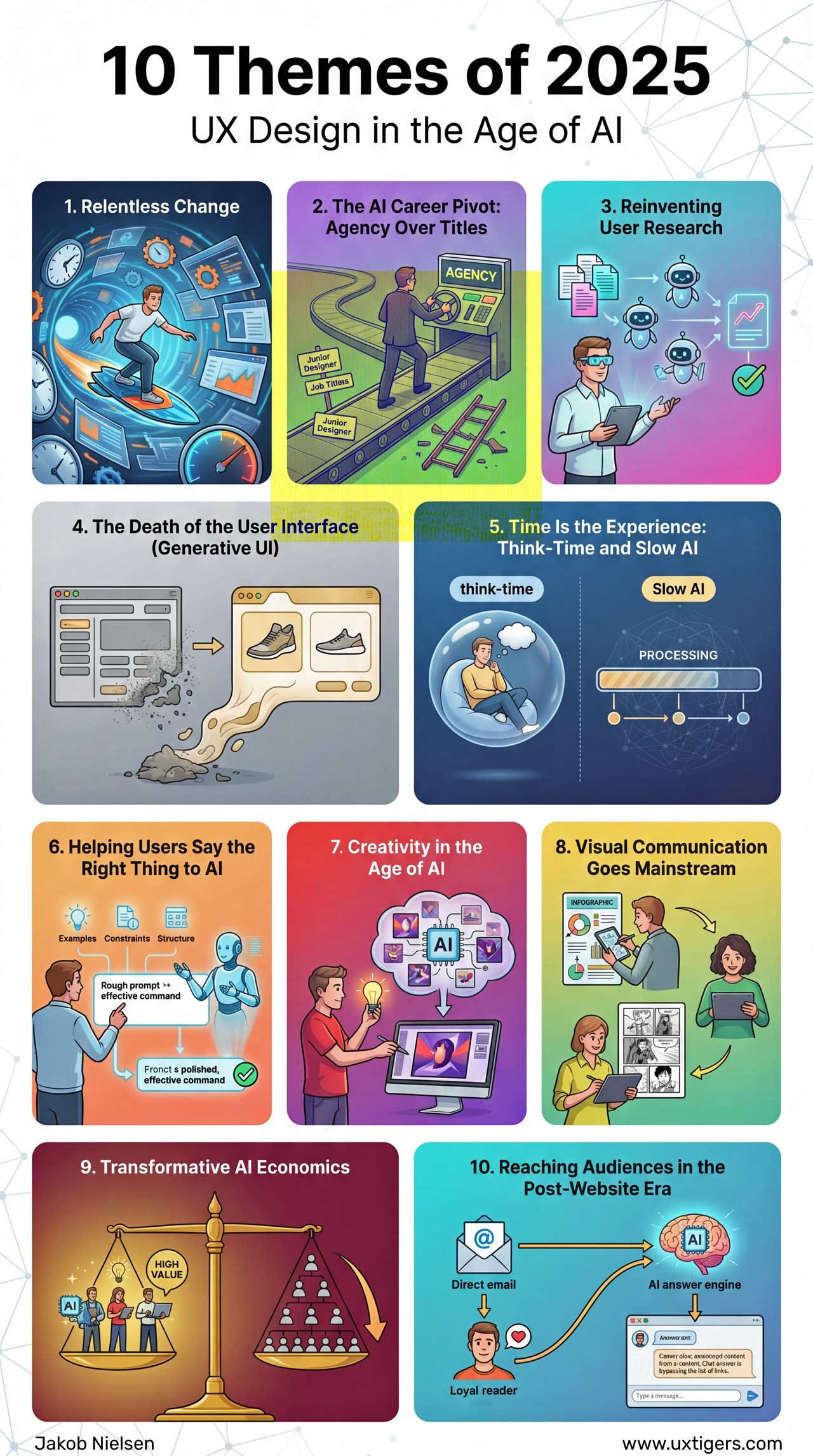

Multimodal Became the Default

In 2024, multimodal models (ones that could handle text, images, audio, video) were impressive demos and very expensive. In 2025, they became how you actually build products.

The reason is straightforward: the real world is multimodal. A customer support ticket isn't just text—it's text plus screenshots. Medical diagnosis isn't just text—it's symptoms plus imaging. Code understanding isn't just text—it's code plus documentation plus architecture diagrams.

Models that could understand all these modalities simultaneously didn't just help you avoid building separate pipelines for different data types. They actually understood the relationships between modalities better.

A vision-language model could read code, understand what it should do, and verify whether the output of that code matched the intent. A model that handled audio, text, and video could understand the tone of a video call, the words being said, and the context of what was happening.

The inference cost was higher than single-modality models, but you avoided the cost of running three separate systems. Companies started preferring multimodal partly for performance, partly because it simplified their architecture.

This also meant that understanding visual content stopped being a special trick. It was just what models did. By year-end, expecting a model to understand images was like expecting a model to understand English—it was the baseline, not a premium feature.

Estimated data shows a balanced distribution with commercial APIs holding 40%, open source models at 35%, and hybrid approaches at 25%. This reflects the diverse needs of companies post-2025.

The Benchmark Crisis Got Worse (And That's Actually Good)

For years, AI progress was measured by benchmarks: accuracy on standardized tests that computers could take. It made progress quantifiable and comparable.

It also made progress misleading.

By 2025, it became clear that optimizing for benchmarks meant building models that were good at benchmarks, not necessarily good at the tasks benchmarks were supposed to represent.

A model could score 95% on a classification benchmark and still fail on slightly different data in the wild. Benchmarks that had been useful became less useful because everyone had optimized for them.

The industry's response was to stop trusting benchmarks as much. More companies started running their own internal evaluations on their specific tasks. More research papers included real-world validation. More practitioners admitted that their model choices were based on "this actually works for our customers" rather than "this has the highest benchmark score."

This is less glamorous than announcing a new benchmark-busting result, which is probably why it's good. It means progress is being measured against what actually matters rather than against what's easy to measure.

The Compute Lottery: Who Actually Has Resources

There's an uncomfortable truth in AI that mostly gets whispered about in private: the companies winning are the ones with access to massive amounts of compute.

Training a state-of-the-art language model costs tens of millions of dollars. That means it's basically available only to companies that can justify that spend (big tech companies) or companies that can raise that much capital (well-funded startups).

In 2025, this divide became explicit and stayed that way.

A company with

This wasn't a new problem—it existed in 2024—but it became more pronounced. The returns on compute got weird: at a certain scale, adding more compute actually did improve results (contrary to earlier thinking that we'd hit a plateau). But the difference between having "some compute" and "optimal compute" was massive.

For startups trying to compete: you either needed the venture capital to justify massive compute spending, or you needed a different strategy (fine-tuning existing models, working on efficiency, focusing on a specific domain rather than general intelligence).

The effect was stratification. The AI market developed clear tiers: large companies with unlimited compute, well-funded startups with substantial compute, and everyone else building on top of open models.

Nano models' success in 2025 was driven by lower costs, minimal latency, and improved accuracy, each rated highly for their impact. Estimated data.

Alignment Became Practical (Not Just Theoretical)

For years, AI alignment—making sure AI systems do what you want them to do—was mostly a theoretical concern. Important researchers working on philosophical problems. Not something affecting practical systems in production.

In 2025, after agentic systems started failing in production, alignment became pragmatic engineering.

Companies realized they actually needed to think carefully about what their systems optimized for. They needed to understand failure modes. They needed to test edge cases instead of just assuming their systems would "do the right thing."

This wasn't fancy alignment research. It was boring stuff like:

-

Testing your system on adversarial inputs before deploying: What happens if someone intentionally tries to trick your model? If the answer is "it confidently does something bad," you have a problem.

-

Understanding what your objective function actually incentivizes: If your model is optimized to "maximize user engagement," does that actually align with what's good for your users? The financial incentives and the user welfare incentives aren't always the same.

-

Having human oversight for high-stakes decisions: If your AI system might be wrong, and being wrong matters, you need a human checking its work. This feels obvious but companies skipped it repeatedly in 2025.

-

Calibrating confidence: A model that admits uncertainty is more trustworthy than a model that's confident and wrong. Companies started implementing tools to force models to quantify their confidence rather than always taking them at face value.

The alignment problem didn't disappear. But it stopped being abstract and started being something engineering teams actually had to contend with.

Prompt Engineering Became Irrelevant (Finally)

For about three years, "prompt engineering" was a real job. You hired someone whose job was to carefully craft the exact wording of prompts to get the best results out of models.

In 2025, that era ended.

Models got better at understanding what you actually wanted rather than requiring specific magic phrases. The difference between "please find the entities in this sentence" and "find entities" largely vanished. A model needed to be useful enough that casual language worked.

This mattered more than it sounds like it should. Prompt engineering was a tax on using AI—you needed specialized knowledge to get good results. When that tax disappeared, more people could use AI effectively.

Companies that had complex prompt-engineering workflows simplified them. The competitive advantage that came from having really good prompt engineers evaporated.

Not that the skill became completely irrelevant—understanding how to communicate clearly to AI systems is still useful. But it went from "specialized skill you hire for" to "just how you talk to computers."

The Copyright and Training Data Wars Continued

In 2024, the question of what data you could use to train AI models was legally murky. In 2025, it got murkier and then started to settle into patterns.

Multiple lawsuits proceeded through court systems. Some ruled in favor of training AI on copyrighted data (with limitations). Some ruled against it. Settlements happened. It remained an active legal territory.

Practically, this meant:

-

Most major AI companies paid licensing fees for training data: Rather than risk legal exposure, they licensed data from publishers, news organizations, etc. This increased training costs but reduced legal uncertainty.

-

Open data became more valued: Data that was explicitly licensed for AI training, without ambiguity, became premium. If your training data came with clear legal rights, that was worth something.

-

International markets diverged: Different countries regulated AI training data differently. The EU had stricter requirements than the US. China had different rules. Companies had to navigate different legal frameworks.

-

Synthetic data became essential: If you couldn't use existing data, you could generate synthetic data. Training models on synthetic data became a major research focus because it sidestepped copyright issues.

This didn't fully resolve the underlying tension—companies still wanted to train on web-scale data, and web-scale data includes copyrighted content—but it created clear enough rules that the legal paralysis stopped.

Agents Got Real When They Stopped Trying to Be Autonomous

Remember earlier when I mentioned that standalone agentic systems were failing? They were still failing. But something interesting happened by the end of 2025.

Systems that positioned themselves not as autonomous agents but as "decision support" or "planning assistance" actually worked well and deployed successfully.

The difference was subtle but consequential: instead of "the AI makes the decision," it was "the AI recommends an action and the human makes the decision."

That's not as sexy a vision of the future. But it's the one that actually works, and companies made peace with it.

An AI system that could plan your day, but required your approval on major commitments? Useful and deployable. An AI system that would autonomously reschedule your calendar based on optimization criteria? Disaster waiting to happen.

An AI system that proposed an investment strategy but required human sign-off? Fine. An AI system that autonomously executed trades? Nope.

By the end of the year, the companies with successful "agent" deployments were the ones who had actually designed them as powerful assistants rather than autonomous actors.

The Talent Churn and The Brain Drain

Earlier in the 2020s, there was limited friction in AI talent allocation. Everyone was recruiting. There was obvious economic value in AI expertise.

In 2025, something shifted. Some of the most respected researchers and engineers started leaving major AI labs.

Partially it was burnout. Building massive models, publishing results, competing for resources—it's intense. Some people wanted a break or wanted different problems.

Partially it was disagreement about direction. Some researchers thought the industry was pursuing the wrong approaches. They were leaving to pursue their own theories about what AI should be.

Partially it was the money shifting. Startups working on specific applications could raise venture capital and pay engineers well. There was no longer a clear economic advantage to being at OpenAI or Anthropic versus a well-funded startup building an AI vertical.

The effect was distributed innovation. Instead of a handful of labs doing all the important AI work, it spread out. That meant slower coordination (no master plan) but probably faster experimentation and more approaches being explored.

The Prediction Markets and Forecasting Got Serious

In 2024, most predictions about AI were either venture capital hopium or doomscripting—wildly optimistic or wildly pessimistic.

In 2025, prediction markets and forecasting platforms became more rigorous. Money was actually on the line. If you predicted something would happen, and you had to bet money on it, your predictions got a lot more careful.

What emerged: the actual median prediction from people willing to put money on it was less dramatic than the public rhetoric. Revolutionary capabilities seemed less imminent. Economic disruption seemed more likely than sci-fi scenarios.

This didn't change what was possible. But it changed what people expected and funded and built toward.

What Gets Built Next: The 2026 Preview

Based on the year that was, some patterns are clear for what comes next:

Efficiency wins over scale: The next major breakthroughs will be in doing more with less, not in having bigger models.

Specialization over generality: The next growth markets are in domain-specific AI, not general intelligence. Legal AI that actually understands law. Medical AI that understands medicine. These beat general models.

On-device and local: As nano models improve, the competitive advantage goes to companies making AI that runs locally, not in the cloud. Privacy, latency, and cost all favor local. Expect that trend to accelerate.

Agents stay collaborative: The autonomous agent future isn't arriving. But collaborative agents—AI that helps humans decide—are becoming standard infrastructure. Build toward that, not full autonomy.

Open source continues to be credible: The gap between open and closed models isn't widening anymore. It's stable. Open source AI stays viable and competitive. That benefits everyone.

The Broader Lesson: AI Got More Real

What defined 2025 in AI wasn't one breakthrough or one story. It was the shift from "this might be amazing" to "okay, here's what actually works and what doesn't."

Small, efficient models work. Large bloated models are often wasteful. Autonomous systems fail. Human-in-the-loop systems work. Specialized models beat general ones. Cheaper models got better faster than expensive ones.

None of these are shocking surprises if you think about them. But they were surprises to an industry that had bet heavily on the opposite assumptions.

2025 was the year those bets got reconciled with reality.

For people building AI systems, that actually makes the job clearer. You don't need the biggest model or the fanciest architecture. You need to understand your actual problem, solve it efficiently, and stay human-in-the-loop for things where being wrong matters.

For people thinking about AI's future, 2025 proved that the technology is powerful and will disrupt things, but not in the sudden, discontinuous way that gets venture capital funding. It's continuous disruption, gradual shifts, and lots of boring engineering.

The year of hype is over. The year of actually building things is here.

FAQ

What made nano language models successful in 2025?

Nano models succeeded because they combined three advantages simultaneously: significantly lower inference costs (70-90% cheaper than previous models), minimal latency since they could run locally on devices, and comparable or better accuracy on real-world tasks thanks to improved training techniques and architectural innovations. The efficiency gains made them economically dominant for many applications.

Why did agentic AI systems fail in production deployments?

Agentic systems failed because they couldn't handle ambiguity, required perfectly defined reward functions, and operated confidently in domains where confident mistakes were costly. The gap between 95% accuracy and 100% accuracy matters when being wrong in an autonomous system means losing money or harming users. Most failures occurred because engineers underestimated how often agentic systems would encounter edge cases that required human judgment.

How did open source models become competitive with commercial models?

Open source models became competitive through rapid community-driven improvement, specialized fine-tuning by thousands of researchers simultaneously, and the economic motivation to optimize efficient models (since anyone could run them locally). When Meta released a competitive open source model, the community immediately created specialized variants, compounding improvements faster than any single company could achieve.

What's the practical difference between autonomous agents and collaborative agents?

Autonomous agents make decisions and take action independently without human oversight, which proved problematic in production. Collaborative agents recommend actions, explain their reasoning, and require human approval before acting. The practical difference is that collaborative agents actually work in production while autonomous agents do not.

Why did specialized models outperform general purpose models?

Specialized models fine-tuned on domain-specific data achieved 12-42% better accuracy than general models because they learned the specific patterns, terminology, and logical structures that matter in their domain. A medical model understands drug interactions. A legal model understands precedent. A financial model understands regulatory complexity. Being mediocre at everything loses to being excellent at the specific thing you need.

Is larger always better in AI models?

No, not anymore. In 2025, researchers proved that smaller models with better training techniques and more targeted architectures outperformed larger models on cost-adjusted metrics. Model size matters, but training efficiency, architectural choices, and task specialization matter more. The bigger-is-better era ended.

What happened to prompt engineering as a profession?

Prompt engineering became less necessary as models improved their ability to understand casual language and informal phrasing. What was once a specialized skill needed to coax good results from models became basic competence. The competitive advantage from sophisticated prompt engineering disappeared.

How did energy constraints affect AI in 2025?

Energy constraints became hard limits on expansion. Large-scale models consumed massive amounts of power, forcing the industry to prioritize efficiency improvements like quantization, knowledge distillation, and pruning. The constraint shifted competition away from "who has the biggest model" to "who can do more with less compute."

What role did alignment play in 2025 AI deployments?

Alignment shifted from theoretical research to practical engineering. Companies deploying AI systems had to explicitly consider failure modes, test adversarial inputs, calibrate model confidence, and implement human oversight for high-stakes decisions. Systems that skipped these considerations failed; systems that implemented them worked.

Where is AI innovation moving next based on 2025 trends?

Based on 2025 patterns, innovation is moving toward on-device efficiency, domain-specific models, collaborative human-AI systems (not autonomous agents), and local deployment rather than cloud APIs. The race to build the largest model is over. The race to build the most useful, efficient, and reliable models is underway.

Conclusion: The Year AI Stopped Performing and Started Working

2025 was the year when a significant portion of the AI hype had to reconcile with engineering reality. And honestly? That's healthier for the technology.

We discovered that you don't need the biggest model to solve real problems. We learned that autonomous systems need humans involved, whether we wanted to admit it or not. We found that efficient, specialized, locally-run AI actually scales better than cloud-dependent massive models.

None of this is devastating news for AI's potential. It's actually the opposite. It means we've moved past the phase where the story mattered more than the engineering. Now the engineering matters more than the story.

That's when real progress happens.

For developers and companies building with AI, 2025 was permission to stop waiting for the perfect model and start using what actually works. Nano models work. Specialized models work. Local models work. Human oversight doesn't limit capability—it increases reliability.

For the research community, 2025 was a redirect signal. The gains come from making what exists better, not from going bigger. That's a different research agenda, and it's already attracting the smartest people in the field.

For everyone else watching the space: the AI revolution isn't postponed. It's just following a different path than the one marketed in venture pitch decks. It's slower, more distributed, more careful about failure modes, and more focused on actual utility.

That's not less interesting. It's more honest.

The spectacle subsided. The real work continued. That's what 2025 meant in AI.

If you're building something with AI, stop waiting for the perfect tool and start with what works. Stop trying to make the AI fully autonomous and add humans to the loop. Stop chasing the biggest model and evaluate based on your actual performance needs on your actual tasks.

The year of hype is over.

The year of building is here.

And that's when things finally get interesting.

Key Takeaways

- Nano language models proved that efficiency and specialization beat raw scale in 2025, shifting the entire industry narrative away from bigger-is-better.

- Agentic AI systems failed spectacularly when autonomous but succeeded when redesigned as collaborative human-AI systems, revealing the AI agents aren't ready for independence.

- Open source models became credible alternatives to commercial APIs, creating genuine competition and accelerating the pace of innovation across distributed teams.

- Specialized models outperformed general-purpose models by 12-42% on domain-specific tasks, validating vertical AI strategies over horizontal general intelligence.

- Energy constraints became hard limits on expansion, forcing the industry to prioritize efficiency improvements like quantization, distillation, and pruning over scaling.

- Inference costs dropped 70-90% through 2025 while performance improved, making cheaper models economically dominant and changing the competitive dynamics permanently.

- Real-world deployment taught harder lessons than benchmarks, shifting the industry away from benchmark optimization toward practical evaluation on actual tasks.

Related Articles

- What AI Really Thinks About Inventing New Winter Holidays [2025]

- 5 AI Trends That Changed My Life [2025]

- JuicyChat.AI: Exploring the Future of AI Conversations [2025]

- Is Artificial Intelligence a Bubble? An In-Depth Analysis [2025]

- [2026] Best AI Productivity Tools

- [2026] 20 Best Generative AI Tools: Top Picks and Benefits

![The Highs and Lows of AI in 2025: What Actually Mattered [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-highs-and-lows-of-ai-in-2025-what-actually-mattered-2025/image-1-1766923667548.jpg)