Introduction: The Militia Call That Never Came

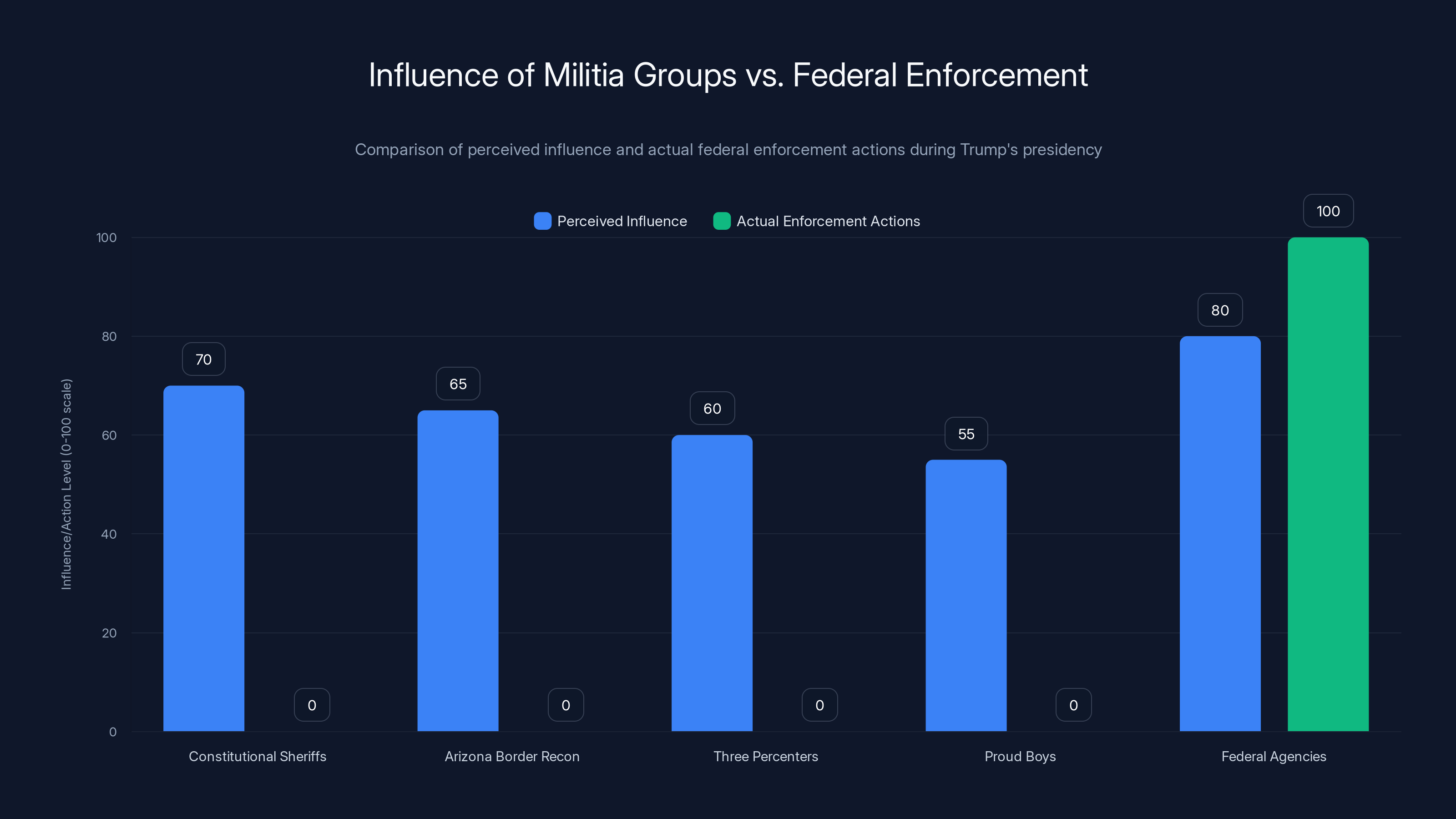

When Donald Trump announced his return to the presidency, militia leaders thought they'd finally get their moment. For years, groups like the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, the Arizona Border Recon, and various Three Percenters cells had positioned themselves as the vanguard of border security. They'd spread election fraud lies, mobilized supporters, and prepared for what they believed was their calling: enforcing Trump's promised mass deportations.

Richard Mack, the founder of the Constitutional Sheriffs group, confidently told media outlets he was already in touch with Tom Homan, Trump's "border czar." William Teer, then leading the Texas Three Percenters militia, didn't wait to be asked. He penned a letter to Trump offering his armed group's services. Tim Foley, running the Arizona Border Recon, claimed direct contact with administration officials. Even the Proud Boys got a meeting with Tom Homan's team, according to reporting from the Southern Poverty Law Center, where they apparently discussed deportations and enforcement strategies.

But here's what actually happened: nothing. Not a single militia member was deputized. Not one extremist group got official marching orders. The call to arms never came.

Instead, something far more consequential took place behind the scenes. The Trump administration didn't need volunteers in tactical gear. It had something much more powerful: the entire federal government, restructured to make immigration enforcement its primary mission. What emerged wasn't militia-led chaos on America's streets. It was an unprecedented militarization of existing federal law enforcement agencies, given unprecedented funding, unprecedented authority, and unprecedented cover from the White House to do whatever they deemed necessary.

This shift represents a fundamental transformation in how immigration enforcement operates in the United States. Rather than relying on external extremist groups, the administration weaponized the bureaucracy itself. The implications are staggering: we're not talking about hundreds of armed volunteers operating in gray areas. We're talking about thousands of federal agents with badges, arrest authority, and explicit presidential backing to treat immigration enforcement as their sole mission.

Naureen Shah, director of government affairs at the American Civil Liberties Union, captured the scale of what's coming in a statement that should concern anyone paying attention: "I think we're just at the beginning. I think we ain't seen nothing yet. They will scale up dramatically in the coming months." One year into Trump's second term, her prediction looks disturbingly on track.

TL; DR

- Federal Militarization Over Militia Recruitment: Trump rejected far-right militia involvement in deportations, instead restructuring federal agencies like ICE and CBP into dedicated enforcement forces.

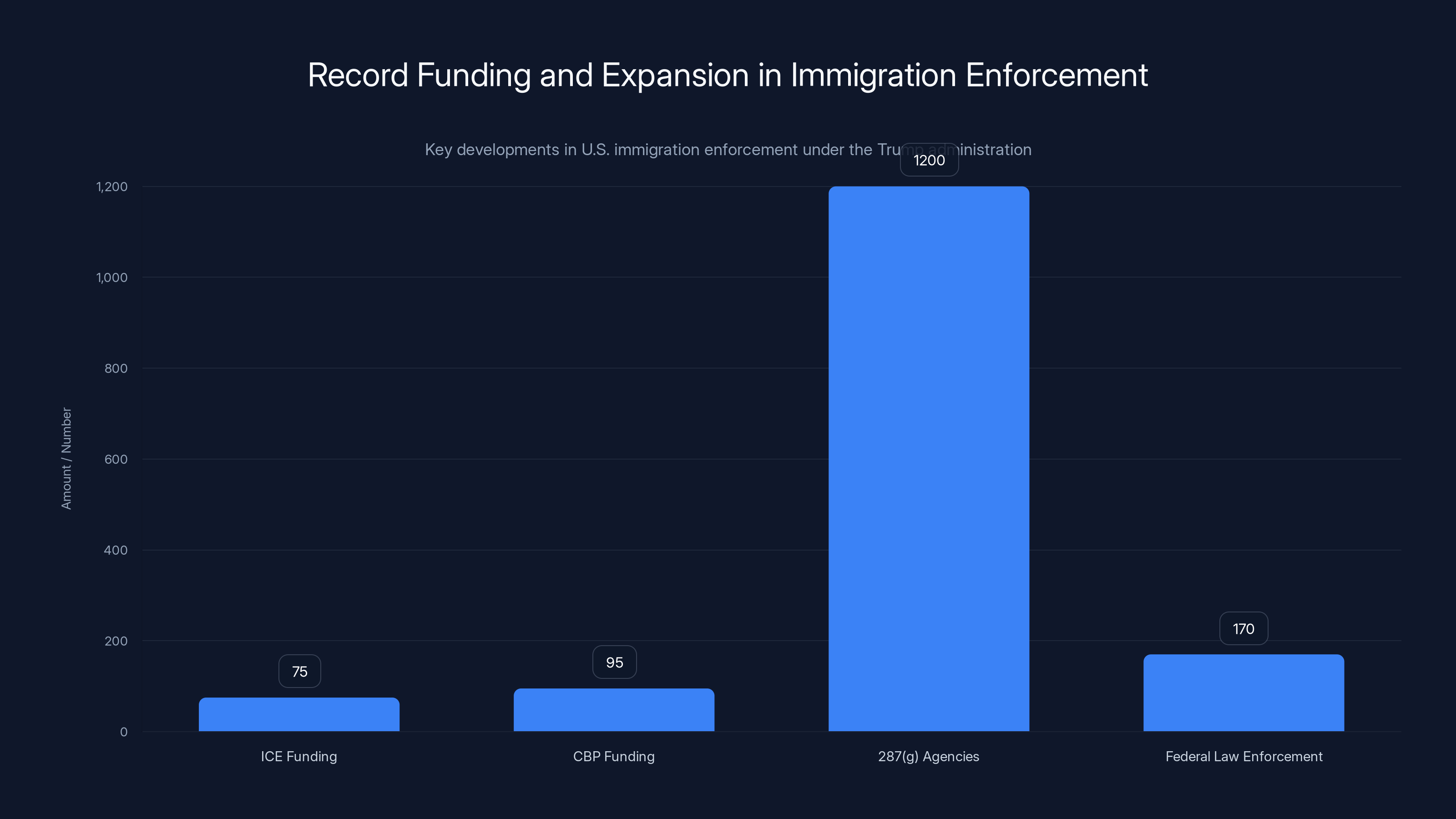

- Record Funding for Immigration Enforcement: Congress approved 75 billion going directly to ICE, making it the highest-funded federal law enforcement agency in history.

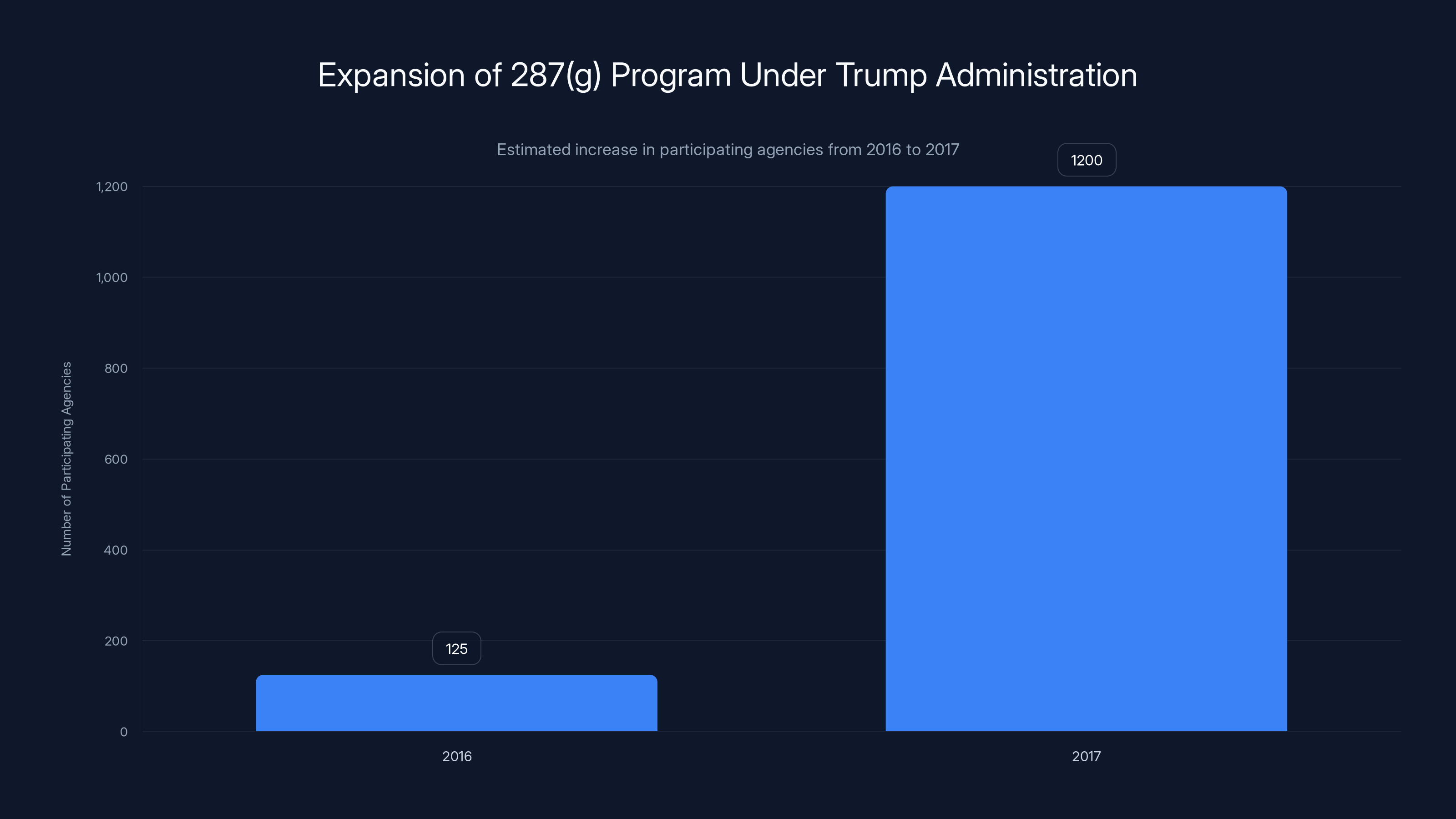

- Expansion of 287(g) Programs: Local law enforcement participation in immigration enforcement jumped from 125 agencies to over 1,200 in less than a year, expanding federal reach into communities nationwide.

- Constitutional Violations and Overreach: The administration has conducted raids at schools, courthouses, and hospitals; disappeared people to countries without connection to them; and arrested elected officials.

- Expert Predictions of Escalation: Civil liberties experts believe the first year represents only the foundation for dramatic scaling up in coming months and years.

The 287(g) program saw a significant expansion from 125 to over 1,200 participating agencies in a year, enhancing local law enforcement's role in immigration enforcement. Estimated data.

Why Militias Aren't Getting Called: The Strategic Calculation

The decision to bypass militia groups wasn't accidental or reluctant. It was strategic. Militia movements come with complications that federal agencies don't: they generate media scrutiny, create legal exposure for official actors, attract federal infiltrators and informants, and complicate the government's ability to deny participation in problematic activities.

Federal law enforcement, by contrast, operates under official authority. ICE agents wear badges. Border Patrol agents have arrest powers codified in statute. The FBI has institutional capacity. These agencies can conduct raids that are technically legal under existing law, making it harder to challenge them as unconstitutional even when the results are arguably unjust.

When Richard Mack claimed he was in ongoing contact with Tom Homan "as recently as this past fall," it underscored how completely the militia leaders had misread the situation. Homan didn't need volunteers. He had an agency to rebuild and expand. The administration didn't need militias because it had something more valuable: legitimate government power, federal funding, and bureaucratic machinery that could execute the deportation agenda at scale.

This was a humbling realization for militia movements that had spent years positioning themselves as essential to Trump's immigration agenda. They'd expected a seat at the table. Instead, they got sidelined by the actual apparatus of federal power. The administration essentially said: we can do this better ourselves, with more authority, fewer complications, and plausible deniability about the details.

What's significant here is that the federal government achieved through institutional restructuring what would have required explicit deputization if militias had been involved. By redirecting existing agencies and personnel toward immigration enforcement, the administration avoided the optics problem of armed civilians conducting raids. Instead, these raids carry official government authority and protection.

The Restructuring: How the Federal Government Became an Immigration Machine

The machinery of federal immigration enforcement extends far beyond ICE and Customs and Border Protection. The Trump administration has successfully redirected resources and personnel from agencies that have never traditionally focused on immigration enforcement into dedicated deportation operations. This includes the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration, various task forces, and countless local law enforcement agencies.

Nayna Gupta, policy director at the American Immigration Council, described the transformation accurately: "What we're seeing right now is the Trump administration effectively realigning the federal government to support mass deportation. This has meant diverting law enforcement resources from several agencies that have never before been involved with low-level immigration arrests, so that they are now focused only on profiling and arresting immigrants."

This isn't subtle reorganization. It's a fundamental reorientation of federal law enforcement priorities. Agencies created for other purposes—drug enforcement, terrorism investigation, organized crime—are now being redirected to immigration work. The FBI has personnel assigned to immigration task forces. The DEA, created to combat drug trafficking, has been brought into deportation operations.

The machinery includes information-sharing systems that federal agents can use to identify people in their communities, workplace enforcement operations that could involve agents from multiple agencies, and coordination protocols that link federal agents with local law enforcement. Every piece of this apparatus was available before, but it's being deployed at unprecedented scale and with unprecedented focus.

What makes this effective from the administration's perspective is that it's not technically new law. The agencies had these powers. What's new is the prioritization, the funding, and the explicit directive that immigration enforcement is the top priority for law enforcement across federal, state, and local governments.

The enforcement infrastructure has expanded significantly, with ICE funding and 287(g) agency participation seeing the most growth. Estimated data reflects narrative insights.

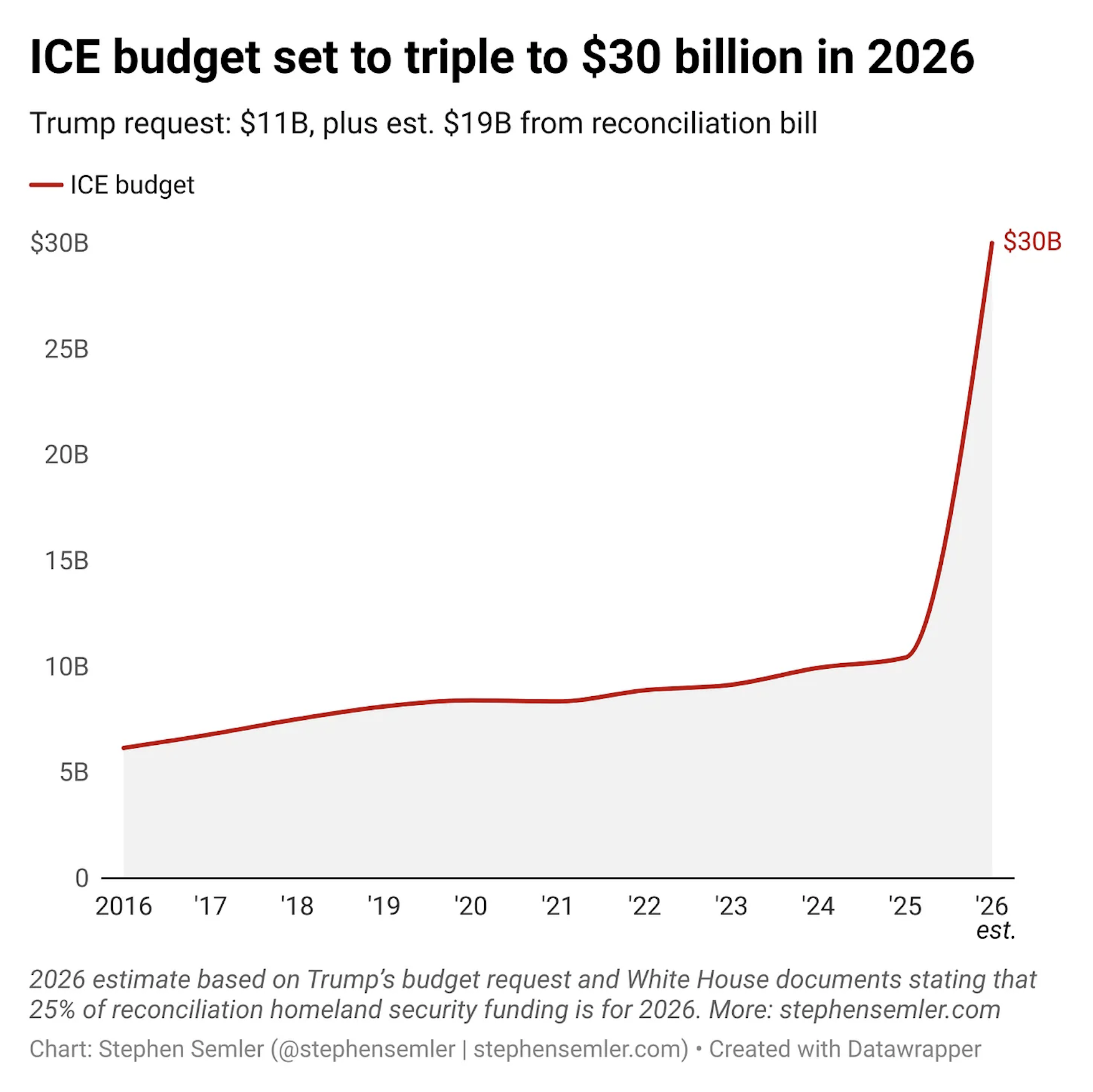

The $170 Billion Question: Funding the Enforcement State

In July, buried in Trump's "One Big Beautiful Bill," Congress approved $170 billion in funding for immigration and border enforcement over the next four years. That's not a rounding error. That's a comprehensive restructuring of federal priorities through the budget process.

Of that

Funding at this scale isn't just about hiring more agents, though there will be thousands of new hiring. It's about infrastructure. It's about detention facilities. It's about intelligence systems. It's about vehicles, technology, and operations. It's about creating a class of federal employment around immigration enforcement that will persist long after Trump leaves office. Once you build bureaucratic structures and fund them at that level, they develop institutional inertia. They lobby for continued funding. They protect their missions.

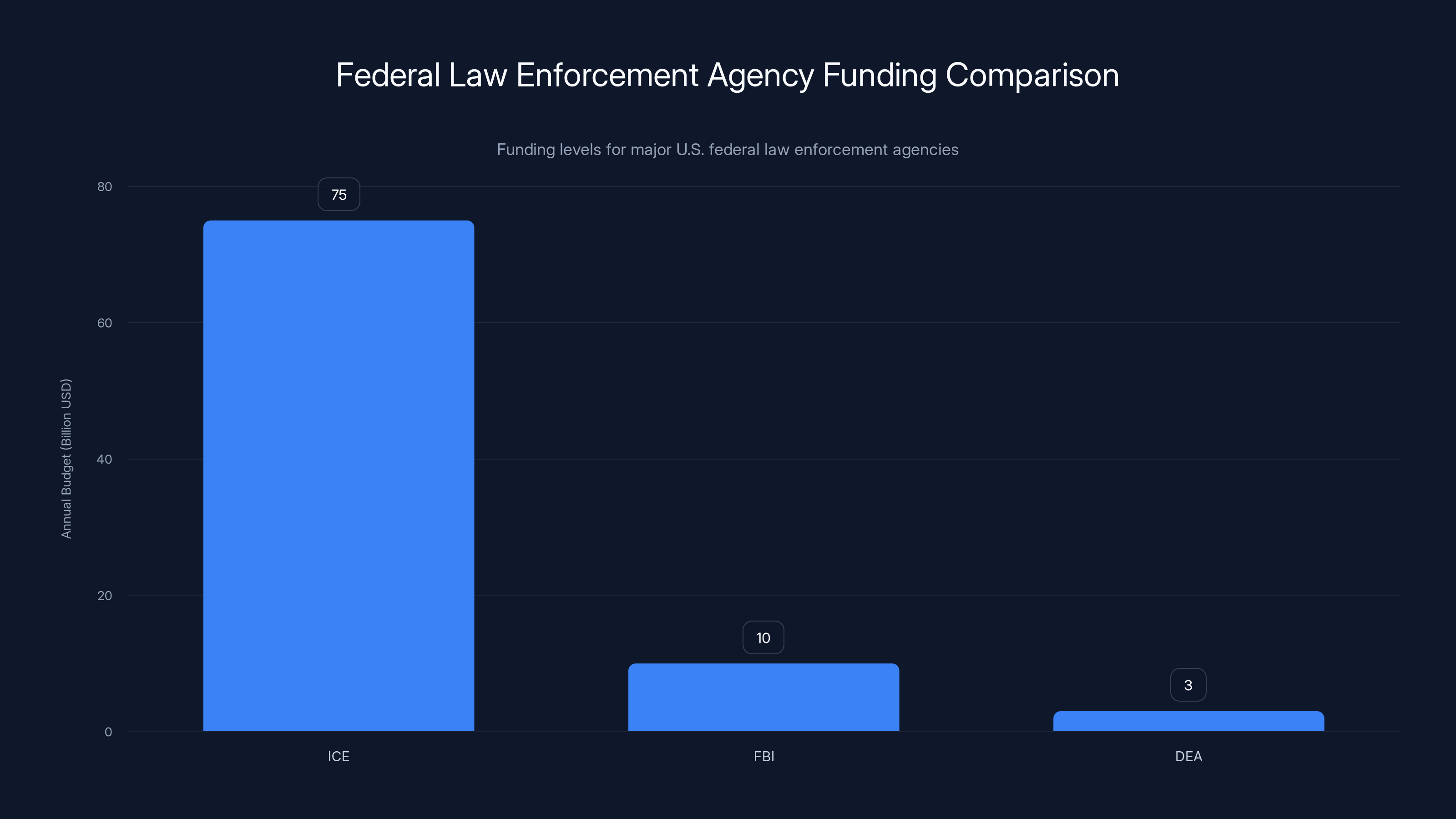

The scale of this investment dwarfs what the federal government spends on other law enforcement priorities. To understand what

This funding doesn't just enable current operations. It enables expansion. It enables agencies to hire aggressively, to pursue operations they've been unable to pursue due to resource constraints, and to deploy surveillance and enforcement technology at scale. The funding is also flexible enough that it can be directed toward detention, away from social services, toward enforcement technology, or toward personnel. The administration maintains discretion on how to allocate most of this money.

From 125 to 1,200: The Local Law Enforcement Multiplication

One of the most dramatic expansions in immigration enforcement involves the 287(g) program, which allows state and local law enforcement to perform immigration enforcement functions on behalf of federal authorities. A year ago, only 125 law enforcement agencies had agreements under this program. As of late November, that number had skyrocketed to over 1,200.

This is the federal government's way of extending its reach into communities that might not otherwise cooperate with ICE directly. By deputizing local sheriffs and police departments—creating what Naureen Shah accurately called "miniature ICEs all across our communities"—the administration weaponizes existing local law enforcement infrastructure for federal immigration purposes.

When a local cop stops someone for a traffic violation, they can now demand citizenship papers. When they make an arrest for a minor local crime, they can detain that person and call ICE. When they conduct investigations, they can work with immigration agents. What this means in practice is that the federal immigration enforcement apparatus has expanded from specialized agencies to every police department in America that chooses to participate.

The expansion to 1,200 agencies in a single year is unprecedented. It represents an institutional choice by local law enforcement to align with federal deportation priorities. Some sheriffs did this enthusiastically. Richard Mack's Constitutional Sheriffs group had been advocating for exactly this kind of role for years. Other sheriffs and police departments may have felt pressure to participate, or saw federal cooperation and funding as beneficial to their own operations.

The result is a vast network of local enforcement that can identify, detain, and hand over immigrants to federal authorities. This solves a massive practical problem that ICE had: capacity. ICE doesn't have enough agents to conduct all the arrests the administration wants to conduct. By expanding 287(g) dramatically, they outsource much of the groundwork to local police.

Raids at Schools, Courthouses, and Hospitals: The Normalization of Enforcement Everywhere

Traditionally, ICE maintained certain unofficial protocols about where raids would and wouldn't happen. Raids at schools, courthouses, and hospitals were supposed to be exceptions. These places were theoretically protected because interfering with education, legal proceedings, and medical care creates obvious problems.

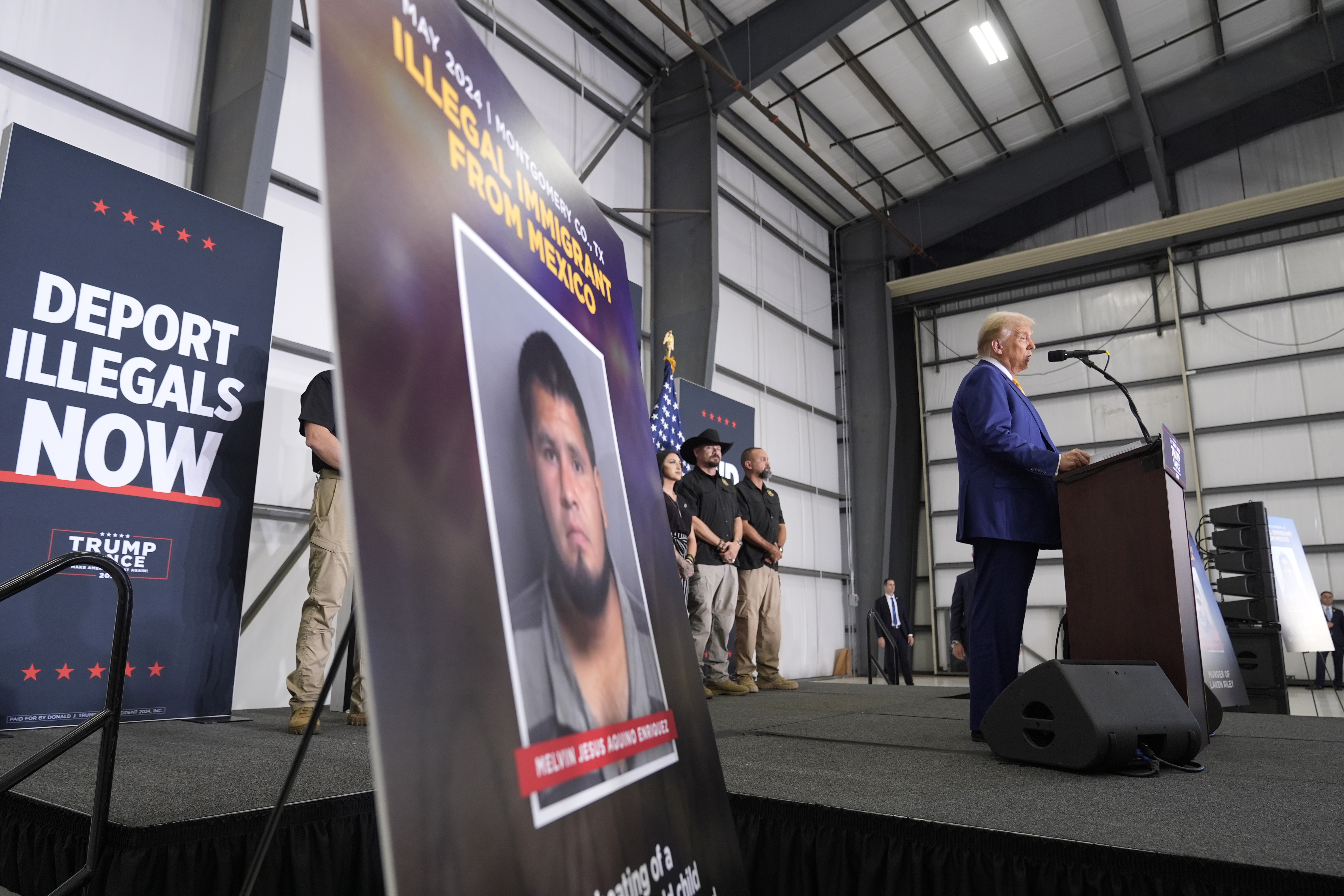

Under this administration, those protocols evaporated. ICE began conducting raids at schools, detaining people at courthouses while they were attending legal proceedings, and intercepting people at hospitals. The administration didn't hide these operations. It documented them.

DHS and White House accounts posted videos of raids to social media. They shared photos, memes, and what critics describe as "AI slop"—AI-generated content that celebrated enforcement actions. Some of this material was incomprehensible outside extremist circles, suggesting the administration was signaling to its base in language designed to excite immigration hardliners while maintaining plausible deniability about actual policies.

The practice of conducting raids at schools is particularly significant. Schools are where immigrant children are most vulnerable and where their presence is documented. Conducting raids at schools creates psychological terror that extends beyond the people arrested. It affects attendance rates, educational engagement, and the willingness of immigrant families to participate in normal civic institutions.

Courthouse raids similarly undermine the rule of law. If people can be arrested at courthouses while attempting to participate in legal proceedings, what's the incentive to appear in court? What's the incentive to trust the legal system? This creates a situation where immigrants are less likely to report crimes, less likely to testify as witnesses, and less likely to engage with courts even when they have legal rights.

Hospital raids create an obvious public health problem. If people are afraid to go to hospitals, they don't seek medical care. Pregnant women don't get prenatal care. Sick people don't get treatment. This endangers the health of immigrant communities and, by extension, public health overall.

The fact that these raids happened wasn't exceptional. It became policy. Multiple raids at schools, multiple incidents at courthouses, multiple hospital operations—these weren't anomalies. They were the operating procedure under this administration.

The cost of detaining immigrants scales significantly with the number of detainees, reaching up to

Disappeared: The Deportation Without Due Process

Among the most alarming developments reported during this period were cases where individuals were deported to countries they had no actual connection to, without due process or meaningful opportunity to contest the deportation. Immigration courts and removal proceedings have always had problems, but the speed and arbitrariness with which deportations were being executed reached new levels.

The phrase "disappeared" isn't exaggeration. People were taken from their homes, places of work, or communities, held briefly, and then transported out of the country within days, sometimes without meaningful communication with family members, lawyers, or advocates who might have identified legal issues with their removal.

This violates basic due process principles that have been part of American law for centuries. Every person in the United States, regardless of immigration status, has certain constitutional protections against arbitrary government action. These include notice of charges, opportunity to be heard, access to counsel, and meaningful review of government decisions.

What was happening was functionally the bypass of these protections at scale. ICE was moving people out of the country faster than the legal system could process challenges to deportation. This is possible when immigration enforcement is treated as the top priority and when agencies are funded and empowered to move quickly without regard to the usual safeguards.

The Military in the Streets: Deployment Against Protesters

When Americans who opposed the deportation operations protested, the administration responded by deploying military personnel to U.S. cities. The justification was that there was a threat of violence from protesters. That threat appears to have been largely fabricated or vastly exaggerated.

The deployment of military forces to American cities is a serious constitutional matter. The Posse Comitatus Act, passed after the Civil War, restricts the federal government's ability to use military personnel for domestic law enforcement. There are exceptions for national emergencies, but the standard for invoking those exceptions is high.

The administration appeared to invoke emergency authority to deploy military personnel against what was characterized as a violent protest threat, but the actual threat level seemed substantially lower than the deployment warranted. This created a situation where military personnel were used domestically, not because of an overwhelming emergency, but because the administration wanted to demonstrate force and suppress protest.

This is significant for what it reveals about the administration's willingness to use military power to maintain its policy agenda. It's one thing to have ICE conduct aggressive enforcement. It's another to deploy military personnel in American cities because people are protesting. The latter suggests a level of comfort with using federal force against the civilian population that goes beyond traditional law enforcement.

Stephen Miller: The Immigration Policy Architect Behind the Curtain

While Kristi Noem, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and Tom Homan received media attention, actual immigration policy was being dictated by Stephen Miller, Trump's deputy chief of staff for policy. Miller's influence over immigration policy isn't new—he's been a major force in Trump administration immigration policy since 2017—but his control in the second term appears more complete.

Miller has a documented history of promoting white nationalist ideas and concepts. His elevation to a position where he effectively controls immigration policy means that the ideological foundation for enforcement actions isn't simply about border security or enforcement efficiency. It's rooted in a particular vision of American immigration that centers on racial and ethnic restrictions.

This matters because it explains some of the enforcement patterns that might otherwise seem arbitrary. The targeting of specific communities, the rhetoric used to justify operations, the selection of which enforcement tools to deploy—these reflect Miller's ideological commitments, not just pragmatic concerns about immigration enforcement.

When Kristi Noem "LARP-ed" as an immigration agent, conducting raids and making speeches, she was implementing Miller's policy direction. When Tom Homan met with militia groups, he was operating under the framework that Miller had established. The system was being run by someone whose motivation isn't simply law and order—it's a particular vision of the American nation that involves restricting immigration based on nationality and race.

While militia groups perceived themselves as key players in immigration enforcement, actual actions were entirely federal, highlighting the government's comprehensive control. Estimated data.

Civil Rights at Risk: Schools, Hospitals, and Legal Proceedings

The decision to conduct enforcement operations at schools, hospitals, and courthouses isn't just about strategy. It's about the systematic destruction of the spaces where rights are actually protected and realized. When you make schools unsafe, you deny immigrant children an education. When you make hospitals dangerous, you deny immigrant communities access to healthcare. When you make courthouses threatening, you deny immigrants access to justice.

This is why these particular targets matter so much. These aren't just places where immigrants happen to be. These are places where immigrants are supposed to be protected because the larger system depends on their participation. If immigrant children don't attend school, the education system is undermined. If immigrants don't access healthcare, public health is undermined. If immigrants don't participate in legal proceedings, the justice system is undermined.

By making these spaces unsafe for immigrants, the administration isn't just conducting enforcement operations. It's actively undermining the functioning of the American system by driving immigrants out of participation in core institutions. This creates a permanent underclass of people who exist in American society but are excluded from its protections and benefits.

The ACLU, various immigrant rights organizations, and civil rights advocates have documented the chilling effect. Reported immigration-related emergency room visits dropped. School attendance in immigrant-heavy areas declined. The message was clear: participate in American institutions and risk deportation.

The Scale of Operations: Numbers and Logistics

The scale of mass deportation operations exceeds what most Americans understand. We're not talking about hundreds of deportations. We're talking about tens of thousands of people being removed from the country each month. This requires infrastructure.

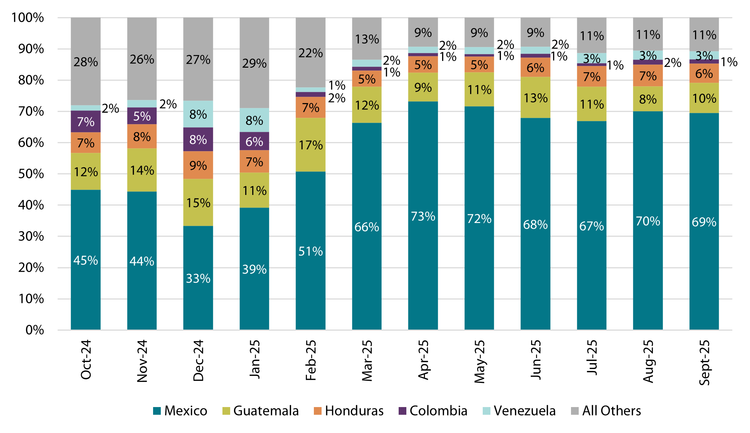

Immigration detention facilities filled up. The administration used other facilities, including military bases, to house people awaiting deportation. Transportation had to be arranged. Deportations to specific countries required coordination with those governments. The logistics of removing this many people from the country is a massive operational undertaking.

What made it feasible was the combination of federal resources, the expansion of local law enforcement cooperation through 287(g), and the elimination of many due process protections that would normally slow down removals. By cutting corners on legal procedure and deploying massive resources, the administration could execute removals at a scale that would be impossible under normal enforcement conditions.

The numbers also have economic implications. Every person detained is in a detention facility, which costs money. Every deportation requires transportation. The administration was essentially spending federal money at an unprecedented rate to remove immigrants. Some of this came from the $75 billion for ICE. Some came from other law enforcement budgets that were diverted to immigration enforcement.

The Arrest of Elected Officials: When Enforcement Became Indiscriminate

One indicator of how far enforcement operations extended was the arrest of elected officials. Democratic mayors, city council members, and state officials who had opposed deportation operations or protected immigrants in their jurisdictions found themselves targeted by federal enforcement actions.

The arrest of elected officials represents a dramatic escalation. These aren't people who are in the country illegally or under simple administrative deportation. These are elected representatives of American cities and states. Their arrest for opposing federal deportation policy or protecting immigrants suggests that the administration was willing to use enforcement operations against political opponents.

This crosses an important line. When the federal government uses law enforcement against elected officials primarily because of their political opposition to federal policy, it suggests the instrumentalization of law enforcement for political purposes. This is a hallmark of authoritarian governance.

The message sent by arresting elected officials was clear: opposition to federal immigration enforcement will be treated as a federal law enforcement matter. This created a chilling effect on political opposition to deportation policies. Mayors became hesitant to protect immigrants or refuse cooperation with ICE if doing so could result in their own legal jeopardy.

ICE received $75 billion, the highest funding for a federal law enforcement agency, while 287(g) programs expanded to over 1,200 agencies. Estimated data.

What's Coming: Expert Predictions of Escalation

Naureen Shah's prediction that "we ain't seen nothing yet" isn't hyperbole based on sentiment. It's based on structural analysis. The first year of mass deportation operations essentially established the infrastructure and demonstrated that the resistance was insufficient to prevent them. That's a foundation for escalation.

Experts in immigration law and civil liberties point to several indicators that suggest more dramatic enforcement actions are coming. First, the administration is comfortable operating at the current scale. That suggests they believe they can expand. Second, they've demonstrated willingness to ignore or bypass legal restrictions that would normally limit enforcement. That suggests they're not constrained by law. Third, they've successfully diverted federal resources and established new cooperation agreements. That means the infrastructure for expansion is in place.

When Naureen Shah says the administration will "scale up dramatically," she's not predicting chaos. She's predicting more of what we've already seen, but at larger scale and with fewer restrictions. More raids. More deportations. More use of 287(g) authority. More cooperation between federal and local enforcement. More people being removed.

The question isn't whether escalation is coming. The structural indicators suggest it is. The question is what it will look like and whether legal challenges or political resistance will effectively constrain it. So far, neither has been particularly effective.

The Role of Immigration Courts: Overburdened and Overwhelmed

Immigration courts in the United States were already stretched thin before the mass enforcement operations began. The immigration court system handles removal cases and was designed to process thousands of cases per year. It's now being asked to process tens of thousands.

This creates a perfect storm. People are being detained in large numbers and need legal hearings. Those hearings require immigration judges, court staff, and facilities. The court system doesn't have the capacity to provide timely hearings for everyone being detained. The result is that people sit in detention for months or longer while awaiting their legal hearing.

This has the effect of both serving the administration's interests and violating due process. People detained for months are more likely to accept voluntary departure (deportation without a hearing) rather than wait for a hearing that might vindicate their legal rights. The system is effectively pressuring people to give up legal rights simply through the burden of detention.

The immigration court system is also structurally biased toward deportation. Immigration judges are part of the executive branch, not independent judges. They have incentives to maintain high deportation rates. The legal standard is also different—immigrants don't have a right to an attorney at government expense in immigration court, unlike in criminal court. These structural features mean that even when hearings do occur, they're often not fair in any meaningful sense.

Data Sharing and Surveillance: The Infrastructure of Enforcement

A crucial piece of the enforcement infrastructure that doesn't get as much media attention is the data and surveillance systems that enable agencies to identify and locate immigrants. Federal agents can query national databases to identify people in their communities, pull information about where they work, find their residential addresses, and determine whether they have legal status.

These systems were developed for various purposes—criminal justice, employment verification, immigration processing—but they're being integrated into a comprehensive surveillance architecture for deportation enforcement. When a person is arrested for any crime, federal systems can flag their immigration status. When a person applies for a job, employment verification systems can alert ICE. When someone registers a vehicle or gets a driver's license, that information can be available to immigration agents.

The integration of these systems across federal, state, and local agencies means that the infrastructure for mass deportation isn't just ICE agents conducting raids. It's a comprehensive data architecture that enables identification and location of immigrants. This explains why 287(g) participation is so valuable to the federal government. Local police have access to local information and data systems that ICE doesn't directly control. When local agencies cooperate, they're essentially feeding their data into the federal enforcement apparatus.

Privacy advocates have raised alarms about this level of data integration, but there's limited legal restriction on it. The federal government is allowed to collect and share data about people in the country illegally, and agencies can use that data for enforcement. The level of integration that's occurring now goes beyond what was previously typical, but it's not technically illegal.

ICE's $75 billion budget significantly surpasses the combined budgets of the FBI and DEA, highlighting a major shift in federal law enforcement funding priorities.

Community Impacts: The Ripple Effects of Enforcement Operations

The effect of mass enforcement operations extends far beyond the people who are actually deported. It creates terror and deterrence effects throughout immigrant communities. People who haven't been arrested or detained become afraid to go to work, to send their children to school, to seek medical care, or to report crimes.

This has measurable effects on the community level. Workplaces with large immigrant populations experience labor shortages as people become afraid to work. Schools with large immigrant populations experience attendance declines. Emergency rooms in areas with large immigrant populations report lower emergency visit rates. Police departments report lower crime reporting rates in immigrant communities.

These ripple effects mean that the impact of mass deportation operations is much broader than the people actually removed. The entire community becomes affected. The entire community experiences the chilling effect of enforcement. The entire community becomes less economically productive, less engaged with schools, less willing to seek healthcare or report crimes.

Some economists have begun to quantify the economic impact. Agricultural regions dependent on immigrant labor experience labor shortages that reduce productivity. Construction sectors dependent on immigrant workers face project delays. Restaurants and hospitality businesses dependent on immigrant workers close or reduce hours. The economic impact of mass deportation operations is substantial, even beyond the human rights concerns.

Legal Challenges: Can the Courts Stop This?

Various legal challenges to the enforcement operations have been filed. Civil rights organizations have challenged the legality of raids at schools and hospitals. Immigration attorneys have challenged the speed of deportations and the denial of due process. Constitutional lawyers have challenged the deployment of military forces.

The question of whether courts will effectively limit these enforcement operations is still being determined. Courts have granted some temporary restraining orders and injunctions stopping specific operations, but they haven't stopped the overall enforcement machinery. The Supreme Court's composition means that constitutional challenges face an unfavorable audience. The judicial system has traditional deference toward immigration enforcement.

What's clear is that legal challenges alone haven't been sufficient to constrain enforcement operations significantly. For legal challenges to be effective, they would need to result in injunctions that prevent large-scale enforcement operations or court decisions that substantially limit the government's authority. We haven't seen that yet.

Some legal scholars argue that the fundamental problem is that immigration law itself is structured to give the government broad enforcement authority. Until the law changes, courts will struggle to limit enforcement based on existing law. Others argue that constitutional protections should apply even in immigration enforcement, and courts have been too deferential to executive authority in this area.

Political Resistance: The Limits of Opposition

Political opposition to mass deportation operations has been significant in certain quarters. Democratic governors have refused cooperation with federal agents. Sanctuary cities have limited their cooperation. Some law enforcement agencies have declined 287(g) participation. Civil rights organizations have mobilized opposition.

But opposition has been insufficient to stop operations. This is partly because immigration policy is one area where presidential power is particularly broad. Presidents have significant authority to direct immigration enforcement. Congress has broad authority to set immigration law. The structure of our system doesn't give much room for resistance from states and cities if the federal government is determined to enforce.

It's also partly because support for enforcement is substantial. Polling data shows that majorities of Americans support deportations of people in the country illegally. While opposition is significant, support is larger. This means that politically, the administration faces more pressure to continue enforcement than to stop it. Elected officials who oppose enforcement face potential electoral consequences.

The result is that political resistance, like legal resistance, has been insufficient to significantly constrain enforcement operations. We've seen individual communities protect immigrants in some circumstances, but the overall trend has been toward greater cooperation and less resistance.

International Dimensions: Deportations to Countries Without Connection

One particularly alarming element of enforcement operations has been the deportation of people to countries they had no connection to. Reported cases included people being deported to countries where they didn't speak the language, had no family, and had never lived. This appears to have happened in some cases where the individual's actual country of origin was different from the country they were deported to.

This practice violates international law and basic humanitarian principles. Countries have obligations not to deport people to places where they're at risk of persecution or where they'll face harsh treatment. Many of the deportations were happening to countries with serious human rights problems.

The motivation for this practice appears to be operational efficiency. Rather than coordinating with multiple countries for deportation agreements, it may have been easier to deport people to countries with whom the administration had specific agreements, regardless of whether those countries were actually the person's origin. This treats individual human beings as fungible objects to be deposited somewhere, anywhere, rather than respecting their fundamental identity and connections.

It also explains why some of the international response to American deportation operations has been critical. Countries receiving deportations are dealing with people who don't belong there, creating diplomatic tensions and practical problems in those countries.

Workforce and Economic Disruption: The Unintended Consequences

Mass deportation operations, while they achieve the enforcement goal of removing immigrants, create significant economic disruption. Certain sectors of the American economy depend heavily on immigrant labor. Agriculture in particular relies on seasonal immigrant workers. Construction depends on immigrant workers. Hospitality and food service depend on immigrant workers.

When these workers are deported, the sectors they worked in experience labor shortages. Labor shortages mean reduced productivity, delayed projects, increased wages in some cases, and reduced profitability. Some agricultural regions have reported crops going unharvested because the labor to harvest them was deported.

This creates a tension for policymakers. The goal of deportation operations is to enforce immigration law and remove immigrants. But the effect is economic disruption that affects American consumers and businesses. Ultimately, this tension may prove to be one of the limiting factors on how much mass deportation can actually occur, if the economic impacts become severe enough that political support erodes.

Some economists have argued that the economic disruption from mass deportation would exceed the benefits of reduced immigration. The calculations are complex, but they suggest that there's a trade-off between strict immigration enforcement and economic performance.

Looking Forward: What Escalation Could Look Like

If enforcement operations do scale up dramatically as experts predict, what might that escalation look like? Possible scenarios include:

Expanded workplace enforcement: Operations targeting entire businesses or industries to identify and deport undocumented workers at scale.

Expanded community enforcement: Broader neighborhood-level operations that go beyond targeted raids at specific locations.

Further reduction in due process: Faster deportations with even less opportunity for legal hearings or judicial review.

Expanded geographic reach: Operations in every part of the country, not just border regions, normalizing enforcement everywhere.

Military involvement: Greater use of military resources or military personnel for enforcement operations.

Punitive measures: Operations targeting people who help or harbor immigrants, as well as the immigrants themselves.

Each of these escalations is technically possible within existing law and would follow logically from the infrastructure that's already in place. The limitation on escalation isn't legal—it's political and practical. How far can enforcement go before the political costs become too high? How far can enforcement go before the economic disruption becomes intolerable? How far can enforcement go before international criticism becomes a serious problem?

These are the real constraints on escalation, not legal ones. The legal structures are already in place.

The Militia Sidelined: Why Far-Right Groups Lost Out

Returning to where we started: the militia groups that expected to be central to Trump's deportation efforts were completely sidelined. Why? The answer reveals something important about how power actually works in government.

Militias are useful for certain things: they provide ideological fervor, they attract supporters, they generate media coverage that excites the base. But they're not useful for carrying out sustained, large-scale operations that require legitimacy and legal authority. When the Trump administration needed to conduct massive enforcement operations, it didn't need volunteers. It needed the federal government.

Federal agencies have what militias don't: legal authority, funding, personnel, infrastructure, and institutional legitimacy. When ICE conducts a raid, it's a legal law enforcement operation. When a militia conducts a raid, it could be kidnapping. The difference is institutional authority.

By redirecting federal agencies and federal resources toward immigration enforcement, the administration achieved the enforcement goal without needing militia participation. The administration got what it wanted—mass deportations—through a path that was actually more effective because it used legitimate government power rather than extra-governmental groups.

For militia leaders who expected to be central to Trump's immigration agenda, this was a humbling recognition that the actual mechanisms of state power supersede extra-governmental movements, even when those movements helped get the person in power elected. The lesson: the people who actually control government machinery don't need your help to govern. They might appreciate your support in getting into power, but once they're there, they have better tools at their disposal.

FAQ

What is mass deportation and how does it differ from routine immigration enforcement?

Mass deportation refers to the removal of large numbers of people from the country in a coordinated campaign, rather than the gradual enforcement of immigration law through normal channels. Routine immigration enforcement happens through ICE agents investigating specific cases, identifying people who've committed crimes or violated immigration law, and initiating removal proceedings through immigration courts. Mass deportation involves coordinated operations targeting broad populations, often with reduced due process protections and at scales far exceeding typical enforcement. The Trump administration's deportation campaign involving tens of thousands of people monthly represents mass deportation rather than routine enforcement.

How does the 287(g) program expand federal immigration enforcement authority?

The 287(g) program allows the Department of Homeland Security to enter into agreements with state and local law enforcement agencies, giving them the authority to perform certain immigration enforcement functions. Under these agreements, local police can interrogate people about immigration status, arrest those suspected of being in the country illegally, and detain them for ICE pickup. By expanding 287(g) from 125 participating agencies to over 1,200 in a single year, the Trump administration essentially created a massive network of local law enforcement agents acting as immigration enforcers. This allows federal immigration enforcement to scale up dramatically because ICE no longer needs to do all the enforcement work itself—local police do much of the groundwork.

Why didn't the Trump administration use militia groups for mass deportation operations?

While militia leaders expected to be deployed for deportation operations, the administration ultimately chose to use federal law enforcement agencies instead. This was a strategic calculation: federal agencies have legal authority, federal funding, federal personnel, and institutional legitimacy that militias lack. When ICE conducts a raid, it's a legal law enforcement operation. When a militia conducts the same operation, it could be illegal. By restructuring and expanding federal agencies, the administration achieved mass deportation goals more effectively through legitimate government power than it could have through extra-governmental groups. Militia groups were essentially sidelined because the federal government proved to be a more efficient tool for the administration's goals.

What are the constitutional concerns about enforcement at schools, hospitals, and courthouses?

Schools, hospitals, and courthouses are places where the government has traditionally protected certain activities from interference. Students have the right to education, patients have the right to medical care, and litigants have the right to access courts. Conducting immigration enforcement operations at these locations undermines these rights and creates chilling effects that discourage immigrant participation in education, healthcare, and legal proceedings. Constitutional scholars argue that enforcement operations at these locations violate due process rights and the right to access courts. Additionally, because these are spaces where vulnerable populations are present, enforcement operations at these locations create secondary harms beyond the people directly deported.

How does federal funding for immigration enforcement impact other law enforcement priorities?

With

What evidence suggests that enforcement operations will escalate beyond current levels?

Experts predict escalation for several reasons: the infrastructure for enforcement is established and functioning, demonstrating that the federal government can execute operations at scale; legal challenges haven't effectively constrained operations; political resistance has been insufficient to stop operations; the administration has shown willingness to ignore or bypass legal restrictions; and the first year of operations appears to be viewed by the administration as a foundation for expansion rather than the full scope of enforcement. Additionally, the explicit goal announced by Trump and his administration is the "largest deportation operation in the history of our country," suggesting that current operations are viewed as preliminary rather than complete. The scale of current operations, while substantial, represents a relatively small percentage of the estimated 10-15 million undocumented immigrants in the United States, suggesting that the administration could expand operations significantly while still being far from achieving its stated goal.

How do immigration courts handle the volume of deportation cases resulting from mass enforcement operations?

Immigration courts were already dealing with massive backlogs before mass enforcement operations began, with hundreds of thousands of pending cases. The sudden increase in deportations from enforcement operations has overwhelmed the system further. Immigration courts don't have sufficient judges, staff, or facilities to provide timely hearings for everyone being detained. This creates situations where people sit in detention for months or longer awaiting their hearing. Structurally, immigration courts are part of the executive branch (unlike regular federal courts), immigration judges have incentives to maintain high deportation rates, and immigrants don't have a right to government-provided attorneys in immigration court. These factors mean that even when hearings do occur, they may not provide meaningful due process or effective advocacy for immigrants facing deportation.

What international implications does mass deportation have, particularly when people are deported to countries they have no connection to?

Deporting people to countries they have no connection to violates international law principles against stateless deportation and has created diplomatic tensions with the countries receiving deportations. Countries receiving deportees are dealing with individuals who don't speak their language, have no family there, and have never lived there. Many receiving countries have criticized the practice and the United States for essentially exporting its immigration enforcement problem. Additionally, if people are deported to countries with serious human rights problems, the United States may be violating international law against refoulement, which prohibits returning people to places where they face persecution. These international implications create diplomatic costs that weren't fully anticipated when mass enforcement operations began.

What economic impacts result from mass deportation operations?

Sectors dependent on immigrant labor—particularly agriculture, construction, hospitality, and food service—experience labor shortages when workers are deported. These shortages reduce productivity, cause project delays, increase labor costs, and can reduce profitability. Some agricultural regions have reported crops going unharvested because deportations removed the workers available to harvest them. These economic impacts affect American consumers through higher prices in affected sectors and affect American businesses through reduced productivity. Some economists argue that the economic disruption from mass deportation exceeds the benefits of reduced immigration, though these calculations are complex and depend on various assumptions about labor markets and economic impacts.

Conclusion: The Architecture of Enforcement

The story of Trump's mass deportation operations is ultimately not the story of militia groups and far-right extremists getting deputized to round up immigrants. It's the story of how a government restructured its entire institutional machinery to make immigration enforcement its primary mission. The militias thought they were going to be important. They weren't. They discovered that the actual power of government supersedes extra-governmental movements, even when those movements helped get the person in power elected.

What we've seen over the first year of this administration is the construction of an enforcement apparatus that doesn't depend on militia participation because it has something more powerful: federal authority, federal resources, federal personnel, and bureaucratic machinery. This apparatus goes far beyond what could have been accomplished through militia recruitment because it's legitimate government power rather than extra-governmental formations.

The expansion of ICE funding to $75 billion, the jump in 287(g) participation from 125 to over 1,200 agencies, the coordination of federal law enforcement across multiple agencies, the integration of data systems for identifying immigrants, and the normalization of enforcement operations at schools, hospitals, and courthouses all represent the construction of an enforcement state oriented primarily toward immigration.

Where this goes from here depends partly on whether political resistance becomes more effective, whether courts enforce legal constraints on enforcement, and whether the economic and social costs of mass deportation become so high that political support erodes. But structurally, the foundation is in place for dramatic escalation. The experts who say "we ain't seen nothing yet" aren't making idle predictions. They're observing that the first year has established an infrastructure for enforcement that could be significantly expanded within existing legal frameworks.

The sidelining of militia groups in favor of federal enforcement machinery reveals something important about how power actually works in government. The most effective enforcement isn't conducted by enthusiastic volunteers. It's conducted by permanent institutions with legal authority, funding, and bureaucratic stability. Militia groups are useful for political purposes—generating excitement, mobilizing supporters, creating the sense that action is being taken. But when it comes to actually governing, actual governments prefer to do it with their own machinery.

What we've witnessed is the effective answer to a question militia leaders asked themselves: will Trump let us participate in his immigration enforcement agenda? The answer, delivered through institutional action, was: no. We don't need you. We have the federal government. And with the federal government, we can do this more effectively, more legally, and at much greater scale than we could ever do with volunteers.

For immigrant communities, for civil liberties advocates, for local governments trying to resist federal enforcement, and for international observers watching from abroad, the practical implication is clear: the machinery for mass deportation has been built, funded, and deployed. Whether it escalates further depends on factors that have little to do with the enthusiasm of militia leaders and everything to do with whether legal, political, and practical constraints prove effective enough to limit expansion.

Based on the first year, those constraints have proven insufficient. The institutions are in place. The funding is allocated. The agreements are signed. The legal authority exists. What comes next will depend on political will, not on whether the administrative machinery is ready. And so far, the administration has shown every indication that it's ready to escalate.

There's one more element to consider: the precedent being set. Once you've built an enforcement apparatus of this scale and deployed it, it doesn't disappear when the administration changes. It persists. It becomes part of the permanent bureaucracy. Future administrations inherit the institutions, the procedures, the data systems, and the cultural normalization that immigration enforcement is a primary government mission. This means that even if political winds shift, the machinery remains for any future administration to activate and expand. The infrastructure of enforcement, once built, is very difficult to dismantle.

The militia leaders who thought they'd be central to Trump's deportation agenda were looking at the wrong power source. The power wasn't going to come from volunteers. It was going to come from permanent government institutions. They're learning what many political movements learn when their candidates actually get elected: governing through institutions is vastly more powerful than governing through movements, and movements are inevitably subordinated to institutional power.

Key Resources and Next Steps

If you're concerned about these issues or want to learn more, here are practical next steps:

-

Connect with legal support organizations if you or someone you know faces immigration enforcement action. Organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Immigration Council, and local immigrant rights organizations provide legal representation and advocacy.

-

Document enforcement operations if you witness them. Video documentation and testimony can support legal challenges and public awareness.

-

Advocate for local policies that limit cooperation with federal immigration enforcement. Some cities and states have enacted policies limiting 287(g) participation or protecting immigrants in certain situations.

-

Support legal challenges to enforcement operations through civil rights organizations that file litigation against unlawful enforcement practices.

-

Stay informed through reporting from outlets that cover immigration policy in depth, rather than relying on incomplete news coverage that may miss important details about how enforcement is scaling.

The stakes are high. The machinery is in place. The escalation is coming, according to experts who study immigration policy. Understanding how that machinery works and where it's heading is the first step toward resisting it effectively.

Key Takeaways

- Trump administration sidelined militia groups expecting to lead deportations, instead restructuring federal agencies into dedicated enforcement apparatus with unprecedented authority and funding.

- Expansion of 287(g) program from 125 to over 1,200 local law enforcement agencies created vast network of federal enforcement reach into American communities.

- 75 billion to ICE alone, makes immigration enforcement the highest-priority law enforcement mission federally.

- Enforcement operations at schools, hospitals, and courthouses represent unprecedented violation of previously protected spaces, creating chilling effects on immigrant participation in essential services.

- Civil liberties experts predict dramatic escalation of enforcement operations beyond current levels, with infrastructure already in place for significant expansion.

- Mass deportation operations create ripple effects through entire immigrant communities, not just those directly removed, affecting education, healthcare, and crime reporting.

- Legal and political resistance has proven insufficient to constrain enforcement operations, with courts deferring to executive immigration authority.

Related Articles

- Plants vs. Zombies: Replanted Review [2025]

- HP ZBook 8 G1i 14-Inch Review: Is This Workstation Worth It? [2025]

- Gmail Finally Lets You Change Your Primary Email Address [2025]

- Best SSDs for PS5 [2026]: Speed, Storage, & Setup Guide

- We Are Rewind GB-001 Boombox Review: Tape Recording Nostalgia [2025]

- Robot Vacuum Losing Connection: 7 Expert Fixes That Actually Work [2025]

![Trump's Mass Deportation Machine: How Federal Law Enforcement Replaced Militias [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/trump-s-mass-deportation-machine-how-federal-law-enforcement/image-1-1766748972861.jpg)