Introduction: The Metal That Broke 3D Printing

For decades, one question has haunted the additive manufacturing industry: why can't we print one of the hardest materials on Earth?

Tungsten carbide sits at the extreme end of the hardness spectrum. It's the stuff that cuts through rock, grinds industrial components, and handles conditions where normal steel would fail. Construction sites, oil drilling rigs, dental offices—they all depend on tungsten carbide tools. Yet until recently, there was no practical way to 3D print it.

Then, in 2025, researchers at Hiroshima University announced something that changed the game. They found a way to print tungsten carbide without melting it. Not by inventing some expensive new machine or exotic laser. Instead, they flipped the entire approach on its head.

Instead of heating tungsten to its melting point (which is around 3,422 degrees Celsius), they asked a simpler question: what if we just softened it enough to bond?

This isn't a minor tweak. It's a fundamental shift in how we think about metal additive manufacturing. And it could reshape everything from industrial tooling to aerospace components to high-performance electronics.

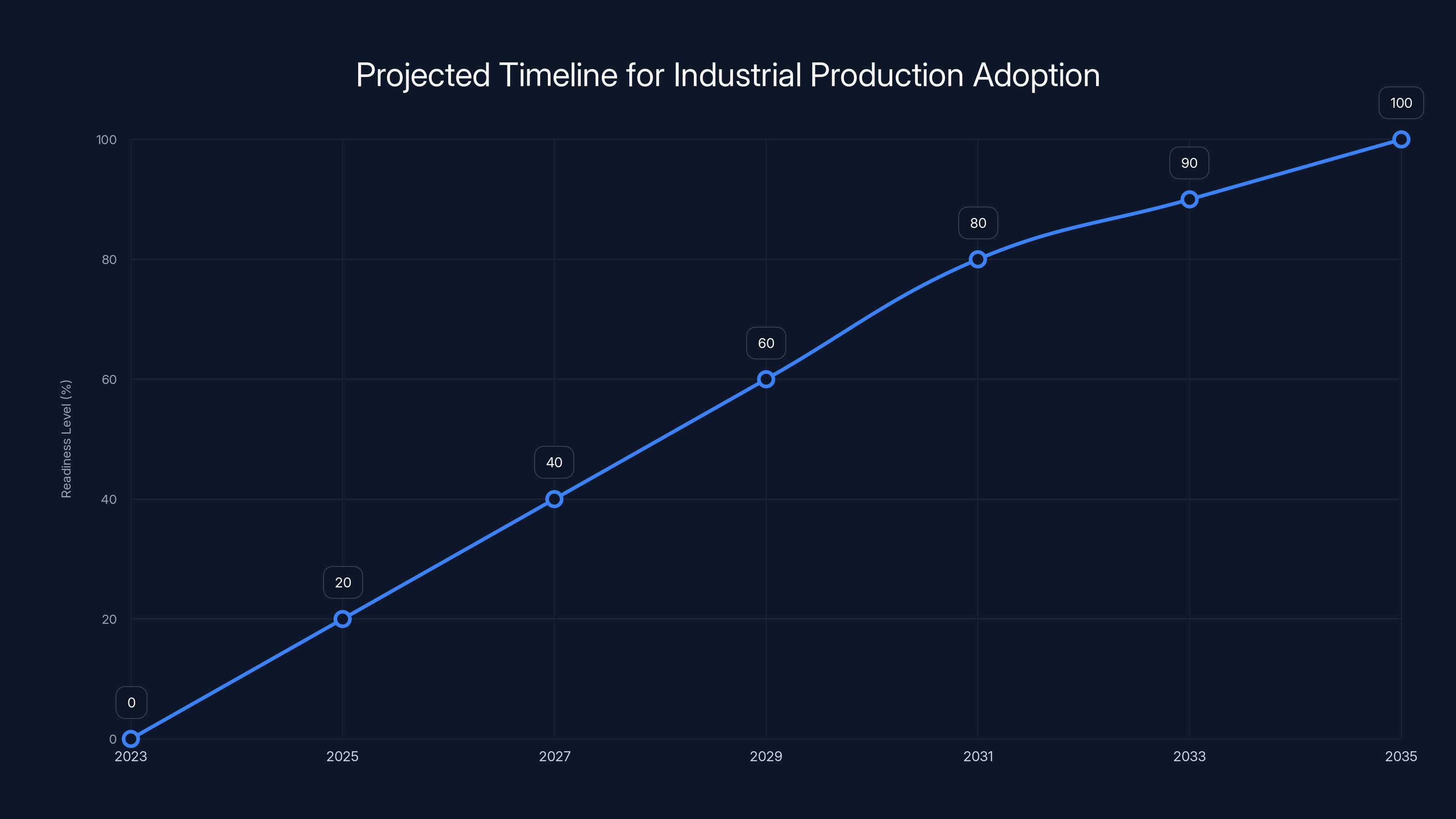

But here's the thing—this breakthrough doesn't mean you'll be printing tungsten parts next Tuesday. The process still has real limitations. Cracking, shape complexity, speed, cost. All of these remain challenges. Yet for the first time, we have a path forward. A method that actually works.

Let's dive into what makes this breakthrough important, how it actually works, what problems it solves, and what barriers still stand between this lab achievement and real manufacturing.

TL; DR

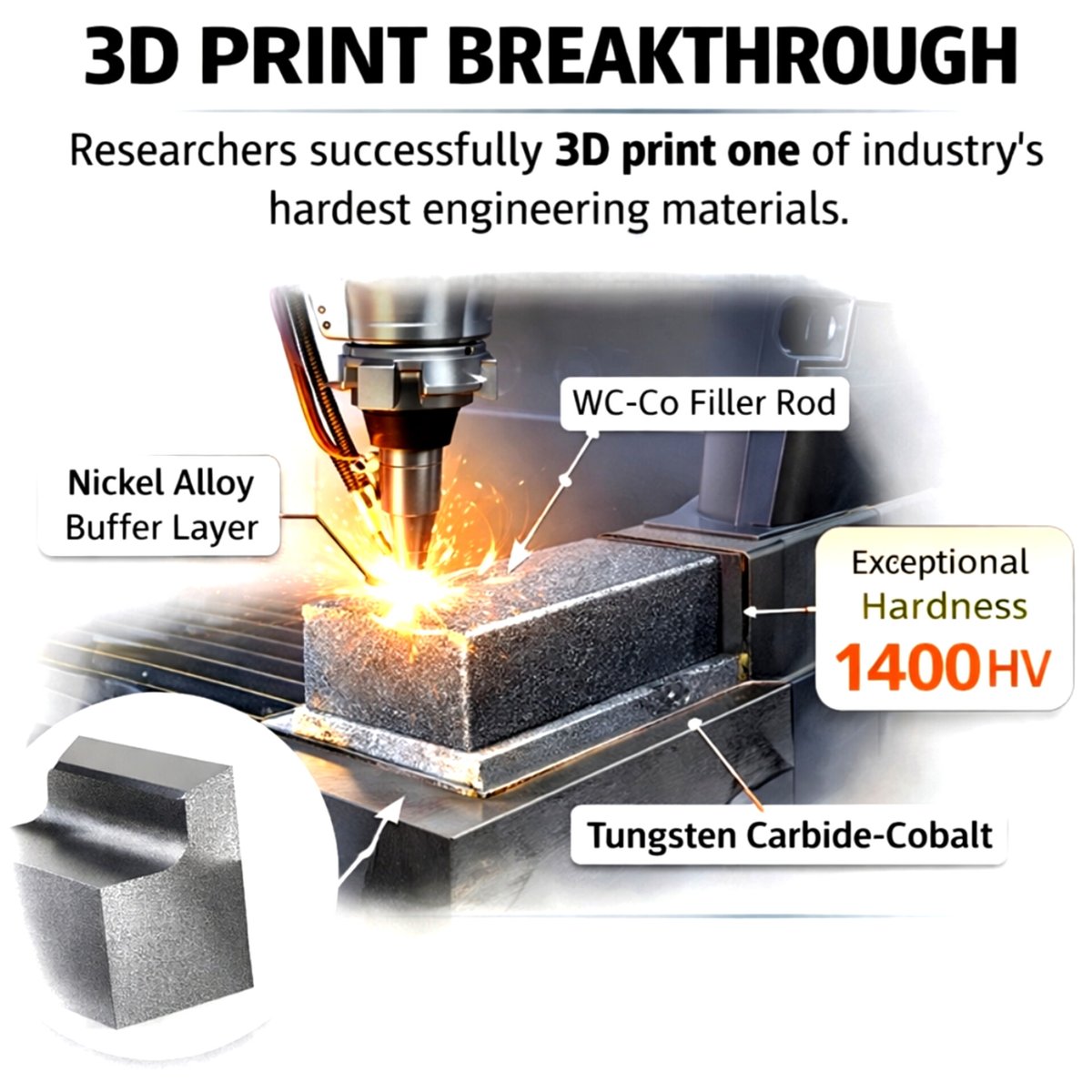

- Softening, not melting: Hiroshima University developed a method that heats tungsten carbide to bonding temperature without full melting, reducing defects by orders of magnitude.

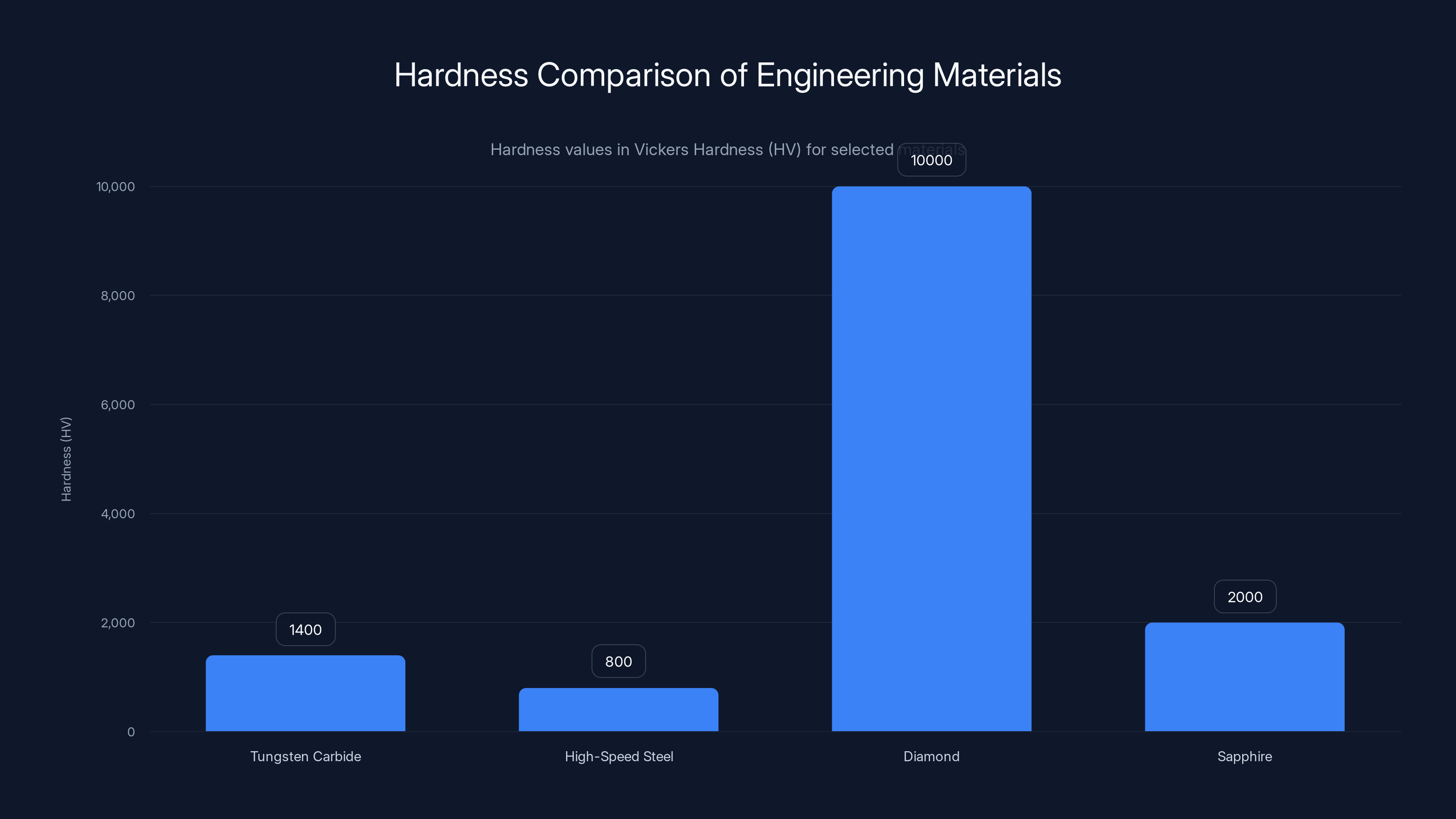

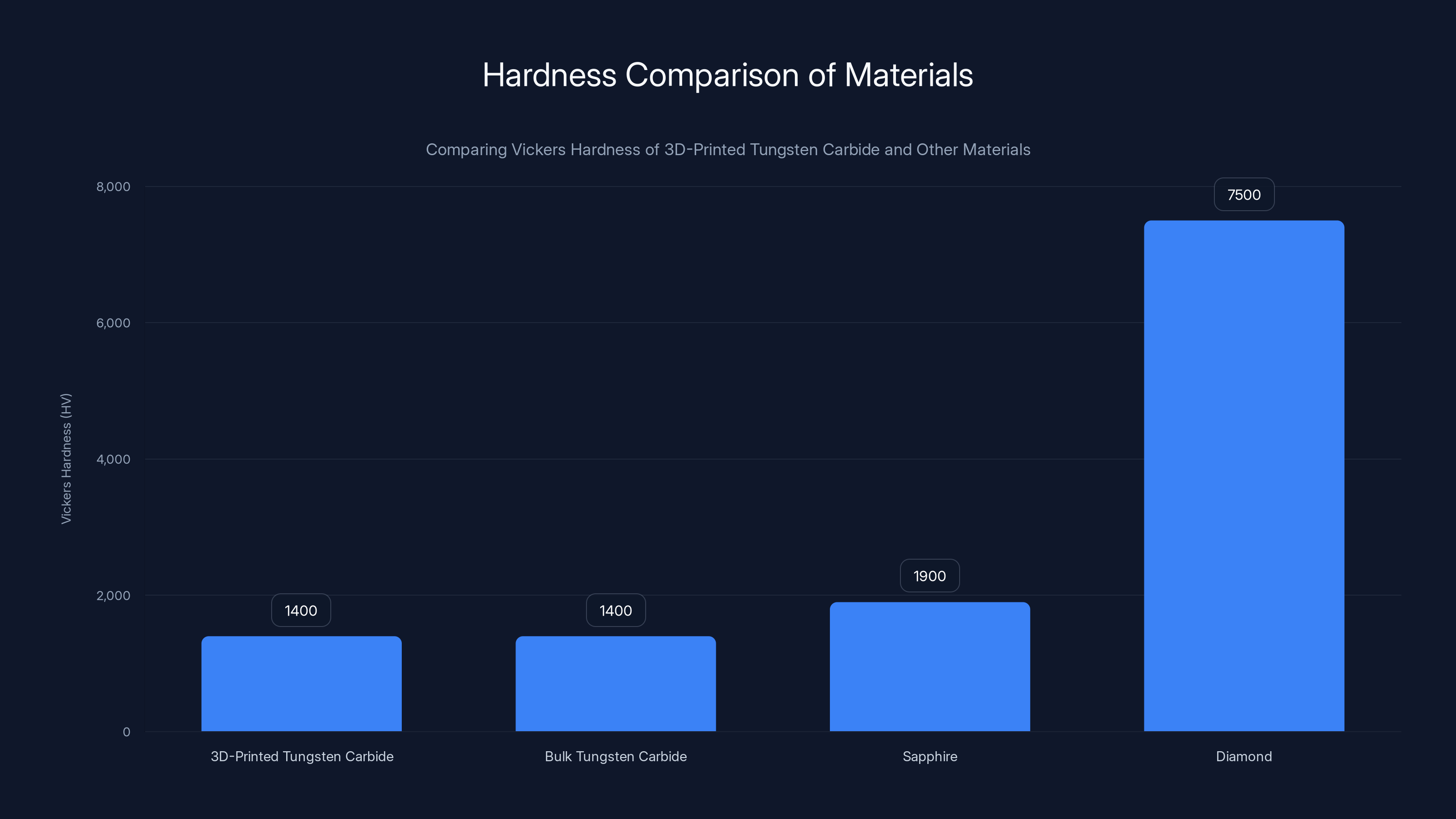

- Hardness achieved: Printed tungsten carbide reaches over 1400HV hardness, comparable to sapphire and diamond for 3D printed metal.

- Layer bonding innovation: Using a heated wire laser and thin nickel alloy interlayers enables reliable layer adhesion without decomposition.

- Manufacturing applications: Could reduce waste in cutting tools, enable complex geometries, and create parts closer to final shape.

- Remaining challenges: Cracking in certain geometries and limited design complexity still prevent widespread adoption.

- Real-world timeline: Industrial-scale production remains years away, despite the breakthrough.

Tungsten carbide is significantly harder than high-speed steel, making it ideal for demanding applications, though it is still softer than diamond and sapphire.

Why Tungsten Carbide Matters: The Material Engineers Love and Hate

Tungsten carbide isn't just another engineering material. It occupies a unique spot in manufacturing—incredibly useful and incredibly difficult to work with.

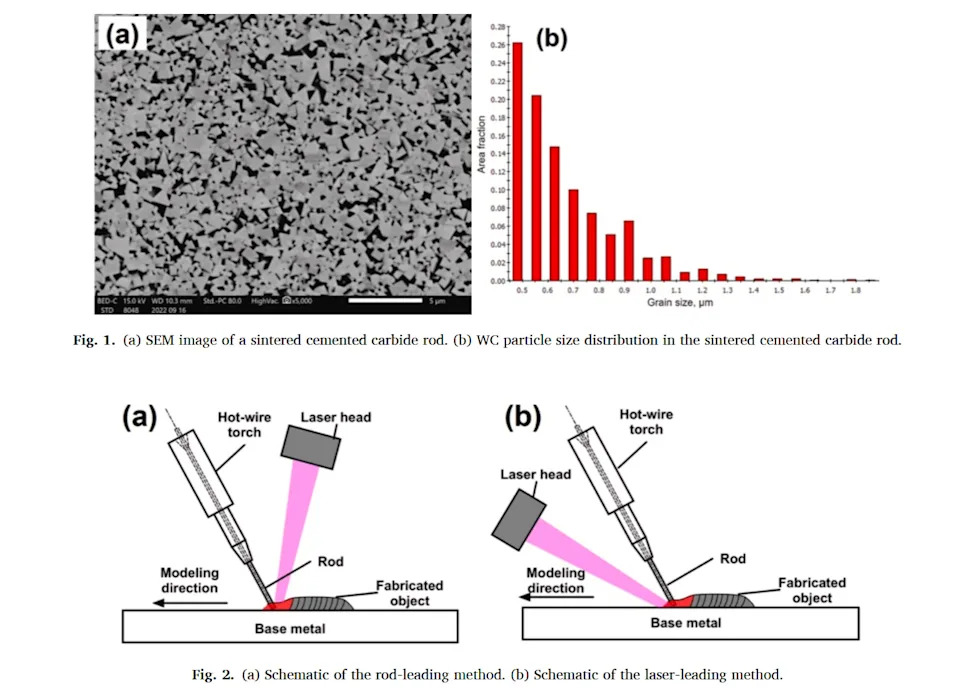

First, let's understand what makes it so special. Tungsten carbide is a composite. It combines tungsten carbide particles (WC) with cobalt binder. This combination creates a material with properties that seem almost contradictory. It's extremely hard, yet brittle. It handles extreme heat, yet reacts badly to rapid cooling. It's perfect for cutting tools, yet nightmare-inducing to produce.

In hardness measurements, tungsten carbide typically sits between 1200 and 1600HV depending on composition. That places it in the rarefied air of engineering materials, just below diamond and sapphire. For comparison, high-speed steel—once the gold standard for cutting tools—maxes out around 800HV.

Where is this stuff used? Everywhere demanding tools see harsh conditions:

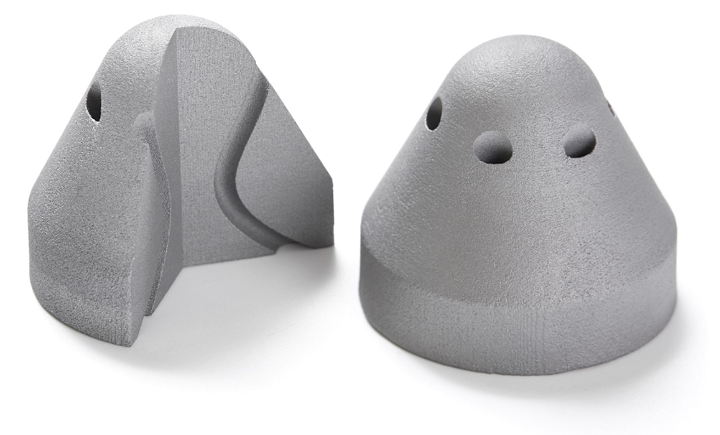

- Cutting tools for machining steel and composites

- Drill bits for oil and gas exploration

- Wear-resistant components in pumps and compressors

- Dies and punches for stamping operations

- Dental burrs used in dentistry

- Armor-piercing rounds in military applications

- Valve seats in high-pressure hydraulic systems

The global tungsten carbide market was valued at approximately $3.2 billion in 2023, with steady growth driven by industrial demand.

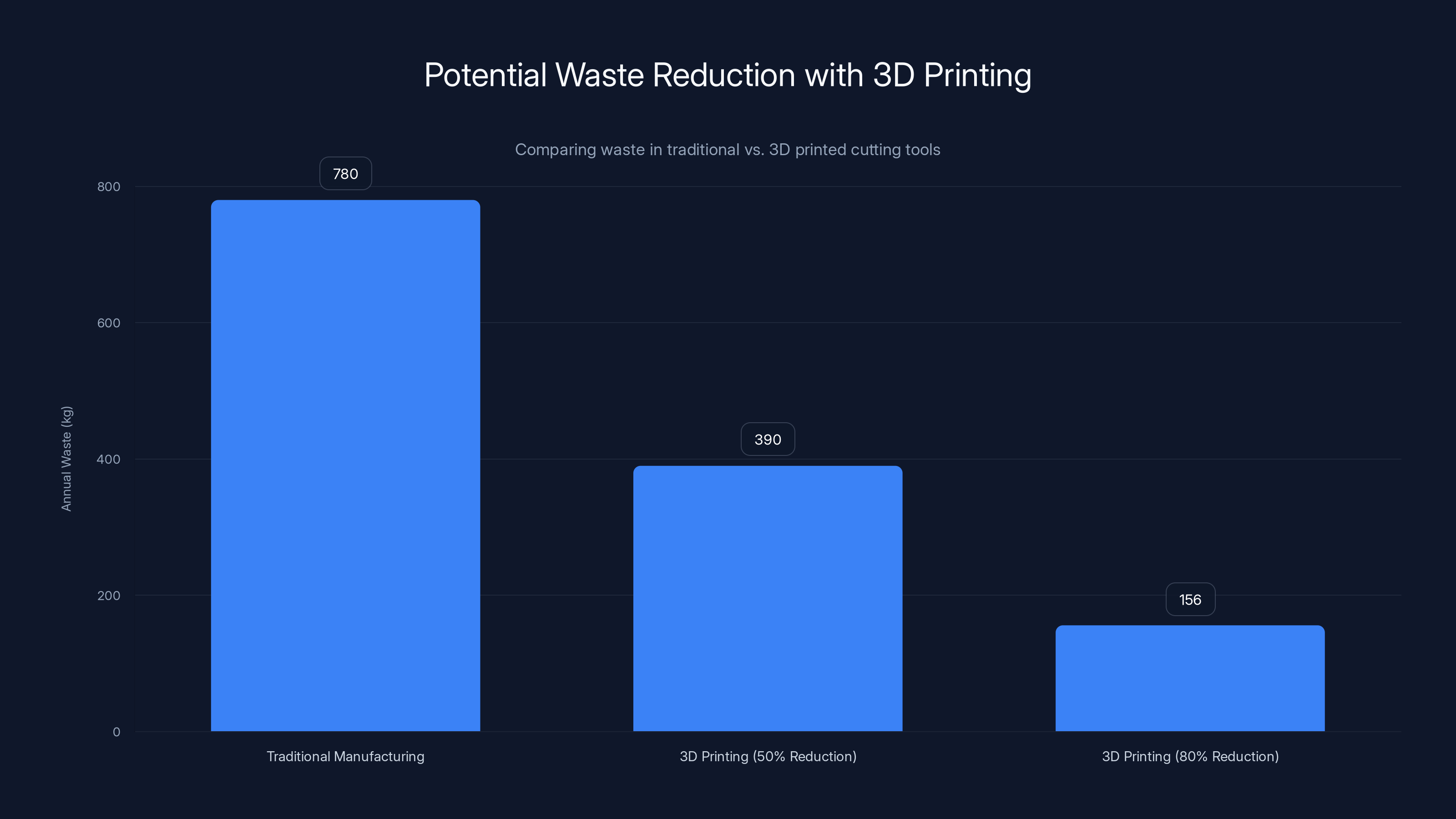

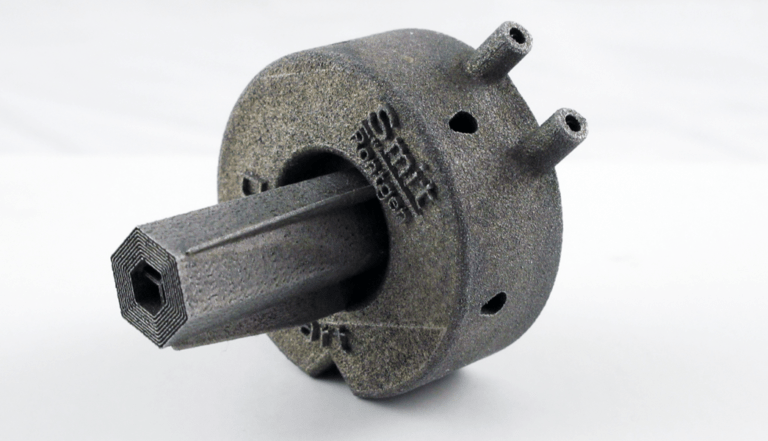

But here's the problem with traditional production. To make tungsten carbide tools, manufacturers start with solid blocks of the material. They use grinding, turning, and wire-cutting to shape them into finished tools. This process wastes enormous amounts of material—often 50 to 80% of the original stock ends up as dust and scrap.

For expensive materials like tungsten carbide (where raw material costs are significant), this waste translates directly to cost. A cutting tool that could be made closer to its final shape would eliminate thousands of dollars in waste per production run for large manufacturers.

There's also the complexity problem. Traditional subtractive manufacturing struggles with intricate geometries. Undercuts, thin walls, internal channels—these become either impossible or economically prohibitive to produce. Additive manufacturing solves this. If you could 3D print tungsten carbide reliably, you could create tool designs that are currently impossible to manufacture.

That's why people have been trying to 3D print tungsten carbide for years. The economic and design benefits are enormous. The challenge has always been the material itself.

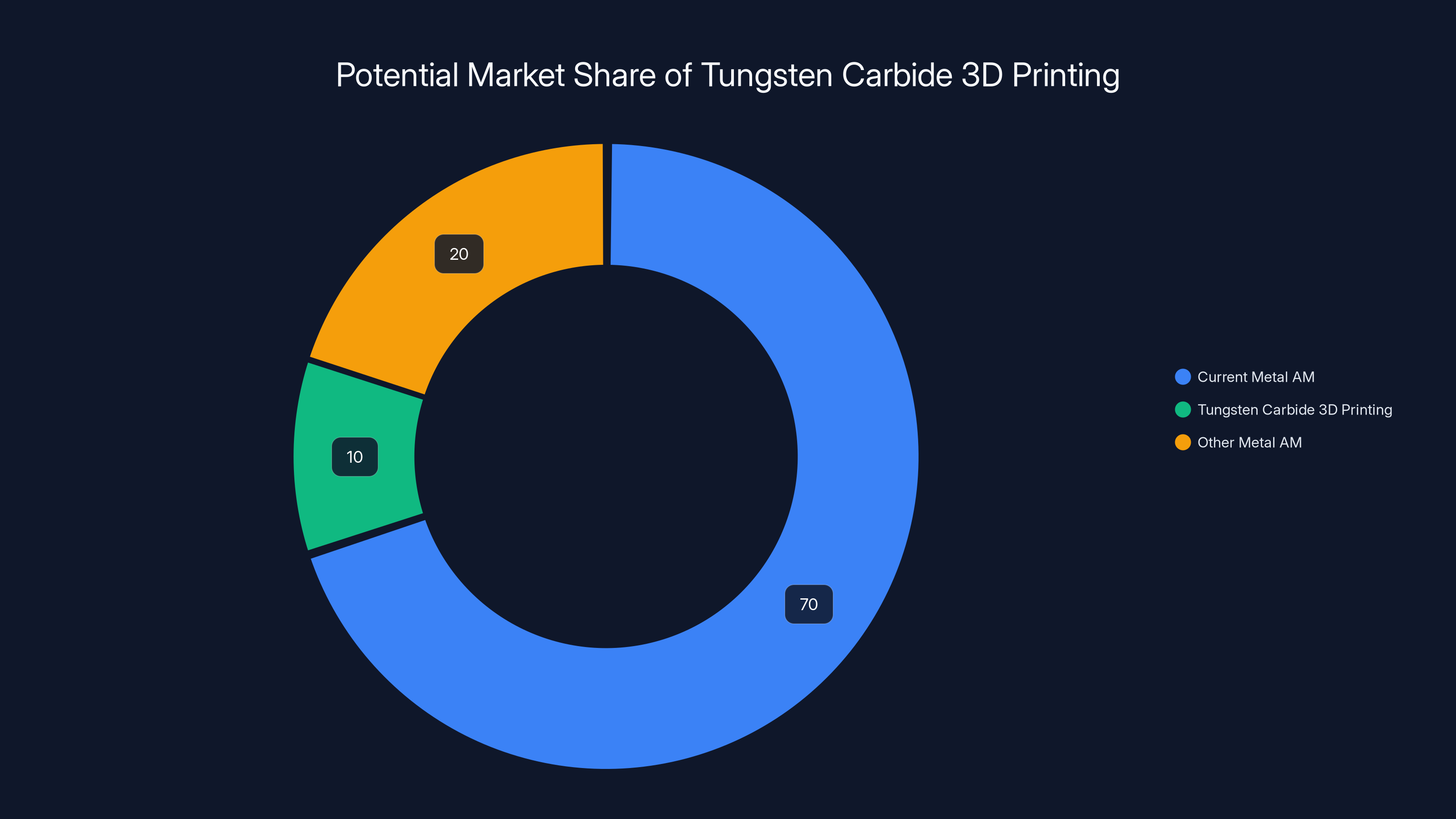

Estimated data suggests that significant industrial adoption of the new manufacturing technology could occur between 2030 and 2035, following a structured development and validation process.

The Old Problem: Why Metals Hate 3D Printing

Let's talk about why metal 3D printing is hard. Because understanding the old problem is the key to appreciating the new solution.

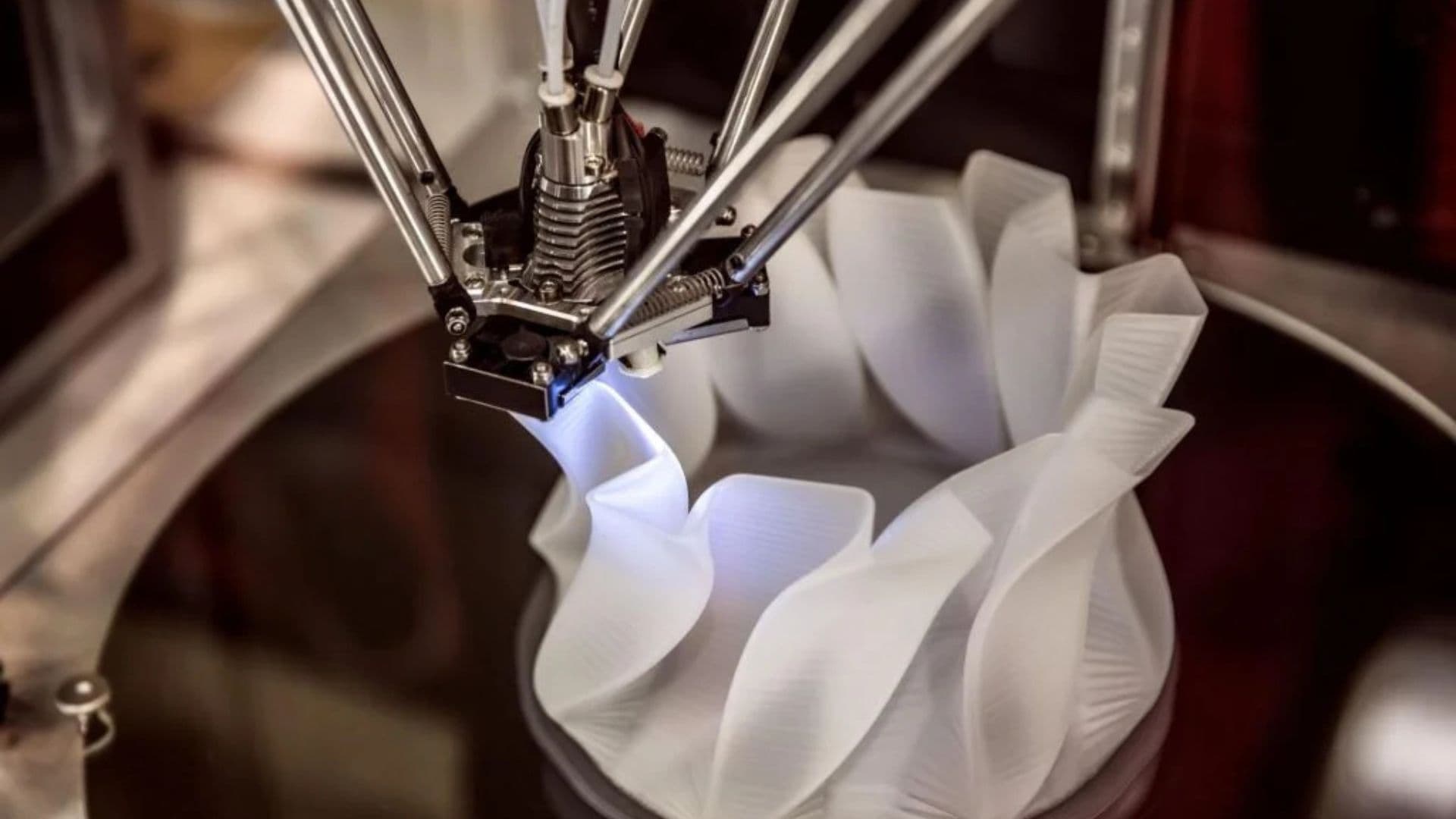

Most 3D printers melt their material. You heat it up, get it liquid, let it solidify in the shape you want. Works beautifully for plastics like ABS and PLA. The material cools slowly enough that you don't get much internal stress. The chemical structure stays stable.

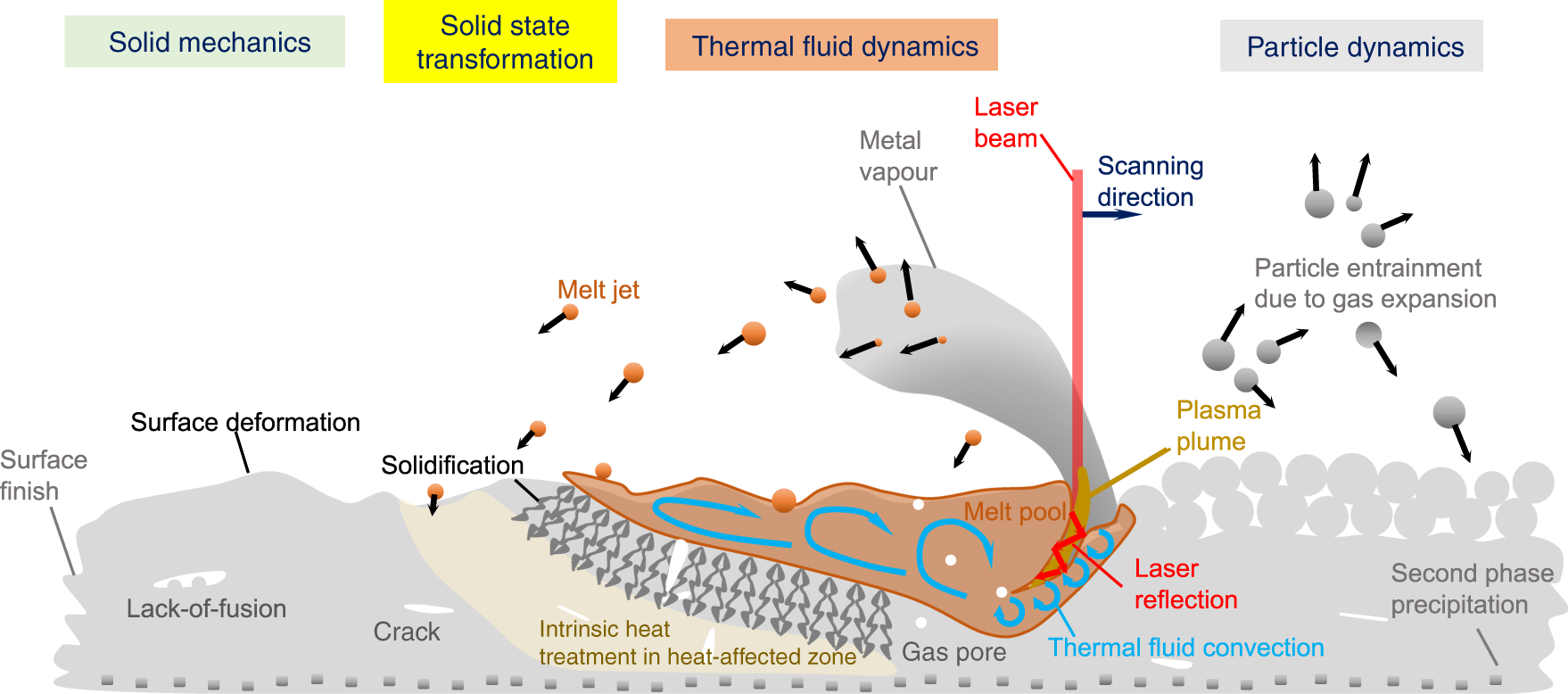

Metals are different. When you melt them, something brutal happens during cooling.

First, there's thermal stress. Metal expands significantly when heated. When the surface cools before the interior, you get differential cooling rates. This creates internal stress that can cause the material to warp, crack, or even shatter. It's why you can't just dump molten metal into a form—you have to carefully control cooling rates or it falls apart.

Second, there's rapid phase change. Many metals undergo structural transformations at specific temperatures. When you heat them rapidly and cool them rapidly, the crystal structure doesn't have time to arrange properly. You end up with misaligned atoms, grain boundaries in weird places, and material properties that don't match the bulk material.

Third, there's chemical decomposition. This is tungsten carbide's specific problem. Tungsten carbide is actually a compound—tungsten and carbon bonded together. When you heat it too much, especially in an oxygen-rich environment, it can decompose. The carbon can evaporate or react with oxygen. You lose the material's defining characteristic: its hardness.

When traditional laser or electron-beam 3D printing tries to melt tungsten carbide, all three of these problems hit at once. You get porosity (air pockets from rapid cooling), cracks (from thermal stress), and decomposition (from excessive heat). The resulting material is soft, brittle, and basically useless.

That's been the wall. Scientists have tried different laser wavelengths, different cooling rates, different surrounding atmospheres. Nothing solved it completely. The more you heat the material to get proper melting and layer bonding, the more defects you created.

Some research groups managed to print tungsten carbide, but the results were disappointing. Hardness dropped significantly—sometimes to 800-1000HV, only marginally better than high-speed steel. The material cracked easily. Complex shapes were out of the question.

By 2023, it was clear that the traditional melting approach had hit a ceiling. You needed a different strategy entirely.

The Breakthrough: Softening Instead of Melting

Here's where the Hiroshima University team did something clever. They asked: what if we don't melt it at all?

Instead of trying to fully melt tungsten carbide and control the chaos during cooling, they developed a process that heats it just enough to make it malleable. Think of it like working with warm clay instead of liquid water. The material becomes workable without the extreme temperatures and phase changes that cause problems.

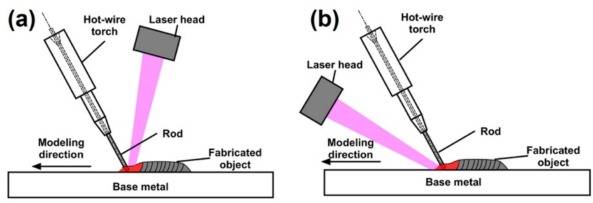

The technical process works like this:

Step 1: Prepare the material

Start with a solid rod of tungsten carbide cobalt. This is your feedstock. Unlike powder-based 3D printing (where tiny particles get melted), this uses a solid rod.

Step 2: Apply localized heat

A high-power pulsed laser focuses on a tiny area of the rod. The laser pulses in nanoseconds (one billionth of a second), applying heat in controlled bursts. The key innovation: the pulses are timed and powered specifically to soften the material without melting it. Think of it like controlled annealing—slow, gentle heating that reorganizes the crystal structure without phase change.

Step 3: Add the heated wire

Alongside the laser, a heated tungsten wire is pressed against the softened material. This wire provides additional heat and mechanical pressure. The combination of laser heat and wire pressure forces the material into the previous layer.

Step 4: Interlayer bonding

Here's a crucial detail: a thin nickel alloy layer is placed between each tungsten carbide layer before printing the next one. This nickel acts as a buffer and bonding agent. It's softer and more ductile than tungsten carbide, so it deforms more easily. When the next layer is pressed down, the nickel bonds firmly to both the tungsten carbide below and the tungsten carbide above.

Step 5: Controlled cooling

Because the material never fully melts, cooling happens naturally from the surrounding air and the printing mechanism itself. There's no rapid quenching. No extreme thermal gradients. The material cools slowly and uniformly.

The result? Printed tungsten carbide that reaches hardness values over 1400HV—virtually indistinguishable from bulk material. No cracks. No decomposition. No porosity.

Why does this work when melting doesn't?

By avoiding full melting, you sidestep several problems at once:

-

No phase change means the crystal structure stays stable. The material doesn't need to recrystallize as it cools, which is where defects usually form.

-

Lower peak temperatures mean less decomposition. Even though the overall temperature is high, the material never reaches the point where carbon evaporates or reacts with oxygen.

-

Reduced thermal stress because there's no liquid-to-solid transition creating huge volume changes. The material just gradually solidifies as it cools.

-

Better layer bonding because the softened state allows mechanical deformation. The heated wire essentially presses each layer into the previous one, creating a metallurgical bond that's actually stronger than a melted interface.

This is fundamentally different from traditional metal 3D printing. Instead of melting and hoping the result stays stable, this approach uses controlled heating to create a material state where bonding becomes natural and defects become rare.

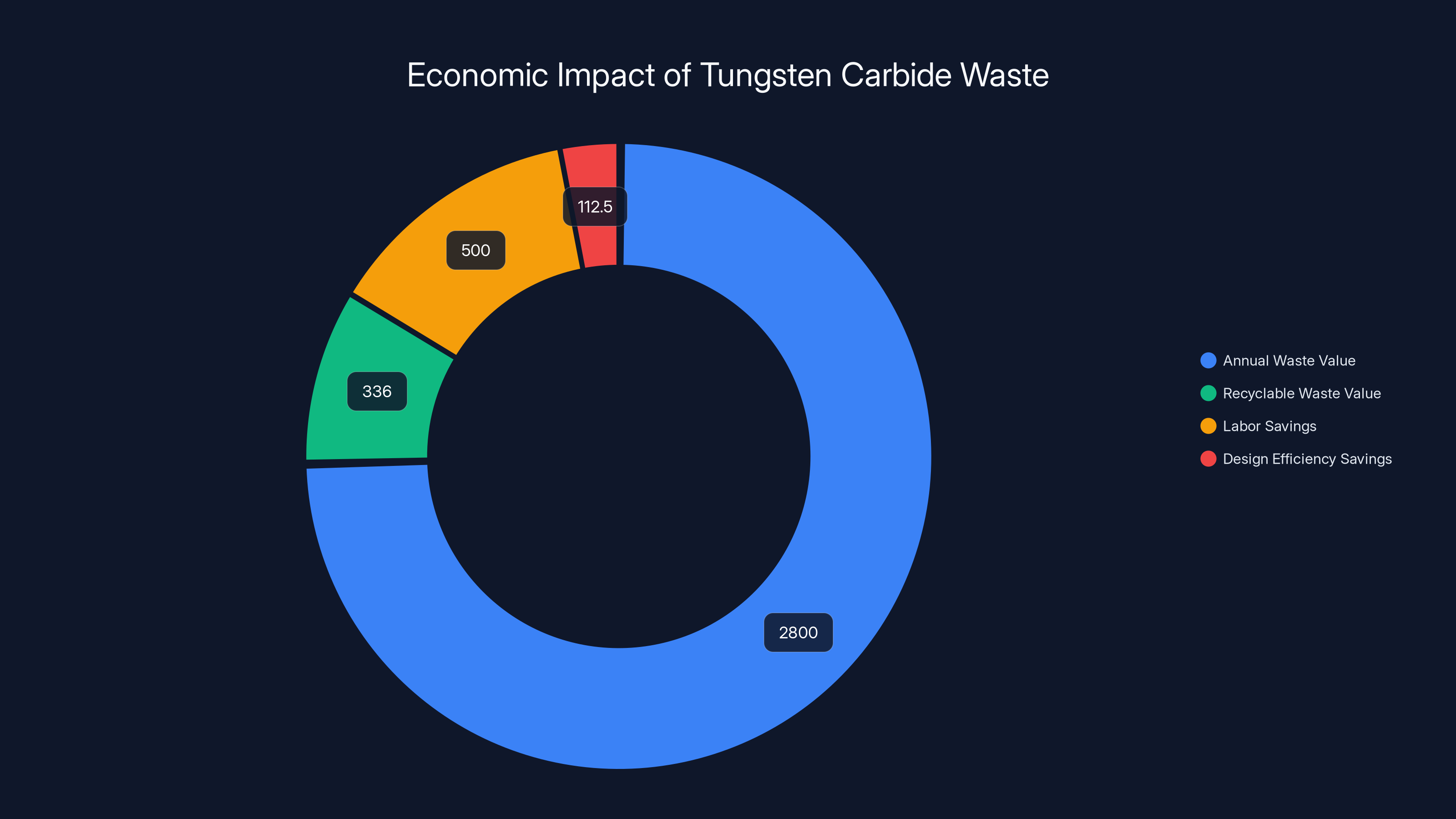

The tungsten carbide tool industry faces significant material waste, valued at

The Mathematics of Material Performance

Let's look at the numbers because they tell the real story.

Hardness is measured in Vickers Hardness (HV). The scale goes roughly like this:

High\text{-}speed\text{ steel} & \approx 800\text{ HV} \\ Traditional\text{ cemented carbide} & \approx 1200\text{-}1500\text{ HV} \\ \text{Tungsten carbide}\text{ (bulk)} & \approx 1400\text{-}1800\text{ HV} \\ \text{Sapphire} & \approx 1600\text{-}2200\text{ HV} \\ \text{Diamond} & \approx 5000\text{-}10000\text{ HV} \end{cases}$$ The printed tungsten carbide achieves **1400+ HV**, which means it's competitive with the best bulk material. That's not just a laboratory result—that's production-quality hardness. But hardness alone doesn't tell the full story. You also need to measure: **Fracture toughness**: How much stress the material can handle before cracking. Measured in units like MPa√m. Tungsten carbide typically has fracture toughness around **8-10 MPa√m**. The printed samples achieved values in this range, meaning they handle real-world stress similarly to bulk material. **Density**: Is there internal porosity? Bulk tungsten carbide has a density of about **14.95 g/cm³**. Porosity would show up as density below this value. The printed samples achieved densities at or near **14.9-15.0 g/cm³**, indicating minimal porosity. **Defect size**: Electron microscopy revealed that the printed structure had defects measured in **micrometers** (millionths of a meter). This is orders of magnitude smaller than defects in traditional laser-melted samples, which ranged from **tens to hundreds of micrometers**. To understand why this matters: a defect that's 100 micrometers acts like a stress concentrator. When you load the material, stress concentrates at that defect, causing cracks to propagate from it. A defect that's 1 micrometer (100 times smaller) concentrates stress less severely. The difference in usable strength is dramatic. Let's put numbers to this improvement: $$\text{Improvement Factor} = \frac{\text{Defect Size (Traditional Melting)}}{\text{Defect Size (Softening Method)}} = \frac{100\mu m}{1\mu m} = 100x$$ This **100x reduction in defect size** translates to materials that are dramatically stronger and more reliable. <div class="definition-box"> <strong>Fracture toughness:</strong> The ability of a material to absorb energy and resist cracking when stress is applied. High toughness means the material bends or deforms slightly under load instead of shattering. Brittle materials (like glass) have low toughness. Ductile materials (like rubber) have high toughness. </div> The researchers also measured **thermal properties**. Tungsten carbide is valued in high-temperature applications because it maintains hardness when heated. The printed samples retained hardness at elevated temperatures just like bulk material. All of these metrics point to one conclusion: the softening method produces material that's materially equivalent to traditionally manufactured tungsten carbide. Not close. Not "good enough for some applications." Functionally equivalent. ---  ## Real-World Applications: Where This Matters Most Let's be concrete. Where would this technology actually change manufacturing? **Cutting Tools and Indexable Inserts** This is the obvious application. Cutting tools need extreme hardness and complex geometries. Today, manufacturers make them by grinding finished shapes from bulk material. It's slow and wasteful. With 3D printing, you could print cutting geometry that's actually optimized for the specific cutting application. Variable flute angles. Custom chip breaker designs. Tailored cutting edges. All geometries that are currently impossible because they can't be ground. A single cutting insert might weigh **5-15 grams**. Current waste in grinding might be **60-70%** of the original material. That's **3-10 grams of tungsten carbide scrap per insert**. For a tool manufacturer producing **10,000 inserts per month**, that's: $$\text{Monthly waste} = 10,000\text{ inserts} \times 6.5\text{ grams/insert} = 65\text{ kg of waste}}$$ $$\text{Annual waste} = 65\text{ kg} \times 12\text{ months} = 780\text{ kg}$$ At current tungsten carbide prices around **$20-30 per kilogram**, that's **$15,600-23,400 in wasted material annually**. For one small tool manufacturer. The largest manufacturers make hundreds of thousands of inserts. 3D printing could reduce this waste by **50-80%**, depending on part complexity. **Drill Bits for Oil and Gas** Drill bits need to withstand extreme pressure, high temperatures, and abrasive formations. Current bits are fixed designs because of manufacturing constraints. If you could 3D print custom drilling geometries for specific well conditions, you could optimize each drill for its exact application. Different formations require different cutting angles. Different depths require different thermal management. Current manufacturing forces a one-size-fits-most approach. 3D printing enables customization at scale. **High-Performance Aerospace Components** Aerospace demands extreme performance with tight tolerances. Some components face temperatures over **1000°C** and need zero defects. Tungsten is used in rocket nozzles, turbine blades, and thermal protection systems. Traditional manufacturing of these components involves extensive testing and validation. Any defect discovered late in production is expensive. 3D printing with near-zero defect rates means higher reliability and lower testing costs. **Dental and Medical Equipment** Dental burs (the drill bits used in dentistry) need extreme sharpness and durability. They run at **500,000+ RPM** and must maintain their edge through thousands of procedures. High-quality burs cost **$5-15 per unit**. Tungsten carbide is preferred because it maintains sharpness longer than steel. 3D printing could enable more efficient designs and reduce manufacturing costs. **Precision Dies and Punches** Stamping operations use tungsten carbide dies because they hold their shape better than steel at the pressures involved. Complex stamping dies with internal cooling channels are expensive to make. 3D printing could enable channels that are impossible to create with traditional manufacturing. <div class="quick-tip"> <strong>QUICK TIP:</strong> The economics of 3D printing depend heavily on part complexity. Simple shapes (where waste from grinding is already low) don't benefit as much. Complex shapes and custom geometries (where current manufacturing is slow or impossible) see the largest benefit. </div> ---  *3D-printed tungsten carbide achieves a hardness of over 1400HV, comparable to bulk tungsten carbide and sapphire, but still below diamond. Estimated data for sapphire and diamond.* ## The Softening Method vs. Traditional Metal 3D Printing How does this approach compare to existing metal 3D printing technologies? Let's break it down. **Selective Laser Melting (SLM)** SLM is the most common metal 3D printing method. It uses a high-power laser to melt powder particles together, building up parts layer by layer. *How it works:* A thin layer of metal powder is spread across a build platform. A laser scans the powder, melting the particles that correspond to that layer's cross-section. The build platform drops, another powder layer is spread, and the process repeats. *Advantages:* Can print many different metals. Well-established. Lots of commercial equipment available. *Disadvantages for tungsten carbide:* The rapid melting and cooling causes the exact problems we discussed—porosity, cracking, decomposition. Results are unreliable for hard ceramics and carbides. **Electron Beam Melting (EBM)** Similar to SLM but uses an electron beam instead of a laser. The electron beam melts powder in a vacuum chamber. *Advantages:* Slightly better thermal management because of vacuum environment. Can handle some harder materials better than SLM. *Disadvantages for tungsten carbide:* Still relies on full melting, so still has the same fundamental problems. Equipment is more expensive than SLM. **The Softening Method** *How it works:* Uses a solid rod feedstock with pulsed laser heating and heated wire pressure. No powder. No full melting. Focuses on softening and mechanical bonding. *Advantages:* - Produces defect-free material matching bulk properties - No powder (easier to handle, less waste) - Lower peak temperatures (less decomposition) - Works specifically well for hard carbides - Mechanical bonding creates strong interfaces *Disadvantages:* - Currently only proven for tungsten carbide (need to develop processes for other metals) - Slower than SLM (builds one line at a time instead of a whole layer) - Still has cracking issues in some geometries - More experimental (fewer commercial machines) **Direct Energy Deposition (DED)** This is actually somewhat similar to the softening method. DED uses a laser and sometimes a wire feedstock to build parts. The material is deposited line by line rather than layer by layer. *How it works:* A laser or electron beam heats the surface. Metal powder or wire is fed into the heated zone. The material bonds as it cools. *Advantages:* Proven for some metals. Faster deposition rates possible. Can repair parts. *Disadvantages:* Still struggles with tungsten carbide. Has similar heating/cooling problems as SLM. Produces coarser surfaces. The key difference with the Hiroshima approach is that it specifically avoids melting by using mechanical pressure to bond layers together. This is fundamentally different from traditional deposition methods. <div class="fun-fact"> <strong>DID YOU KNOW:</strong> The first attempts at metal 3D printing date back to the 1980s and 1990s, but most technologies focused on powders because feedstock handling was easier. Solid rod feedstocks (like in this tungsten carbide process) were largely abandoned for decades, but researchers are rediscovering their advantages for hard materials. </div> ---  ## Current Limitations: What Still Doesn't Work Here's the honest part. This breakthrough solves a major problem, but it doesn't solve all of them. Not even close. **Cracking in Complex Geometries** The softening method works great for simple shapes. Flat parts. Basic cylindrical forms. But the moment you try something complex—undercuts, thin walls, internal channels—cracking becomes a problem. Why? Multiple reasons: 1. **Residual stress concentrations** build up in complex geometries. When you print a simple shape, stress distributes evenly. When you print something with sharp corners or stress concentrations, those areas become weak points. 2. **Thermal gradients** are harder to control in complex parts. Some regions heat up while others cool down, creating internal stress. 3. **Layer orientation matters**. The mechanical pressure from the heated wire works well perpendicular to the build direction, but complex geometries require bonding in multiple directions. This isn't a minor limitation. It means you can't print intricate tool designs. You can print cutting tips and basic shapes, but complex chip breakers or internal cooling channels are out. **Print Speed** Currently, the process is slow. It builds material line by line, not layer by layer. A production-ready printer might produce **1-2 cm³ of material per hour**. Compare that to SLM, which can produce **10-15 cm³ per hour**. For a small cutting insert weighing **10 grams** (density 15 g/cm³ = 0.67 cm³), the softening method would take **20-40 minutes**. That's not competitive with traditional grinding, which takes maybe **5-10 minutes per insert**. Speed matters economically. Until the process is **at least 5-10x faster**, it won't be viable for high-volume production. **Cost and Equipment** The current system requires specialized equipment: a pulsed laser system, a heated wire feeder, precise motion control. This isn't something that exists off-the-shelf. A commercial SLM machine costs **$500,000-$1,000,000**. The softening method printer would need to be built from scratch. Initial machines might cost **$2-5 million**. That's a huge barrier for small manufacturers. **Material Waste and Heat Management** While the softening method wastes less material than grinding, it's not perfect. The laser heating requires careful energy management. If you're not careful with the laser power, you still get some melting at the interface. If you don't apply enough power, you get weak bonding. The process also generates heat. The heated wire reaches **hundreds of degrees Celsius**. Thermal management of the entire printer is critical but adds complexity and cost. **Limited Material Range** This process was developed specifically for tungsten carbide. It's not clear if it works equally well for other hard materials like titanium carbide, boron carbide, or ceramic composites. Each material has different softening temperatures, different chemical stability requirements, different bonding characteristics. The researchers would need to develop new process parameters for each new material, which is time-consuming and expensive. <div class="quick-tip"> <strong>QUICK TIP:</strong> The cracking issue might be solvable with better thermal control and stress relief techniques. Post-processing the printed parts (annealing or stress relief cycles) could reduce residual stress and allow more complex geometries. This isn't proven yet, but it's a reasonable research direction. </div> ---   *3D printing could significantly reduce material waste in cutting tool manufacturing by 50-80%, saving up to 624 kg of tungsten carbide annually for a small manufacturer. Estimated data.* ## The Path to Industrial Production When might we see this in real manufacturing? Honestly? Not soon. Right now, this is a lab achievement. A **proof of concept**. It works in controlled conditions with expert operators. Before it becomes an industrial tool, several things need to happen. **Phase 1: Process Refinement (1-2 years)** Researchers need to: - Develop process parameters for different part geometries - Solve the cracking problem in complex shapes - Improve speed by 5-10x if possible - Test reliability over hundreds of print cycles - Develop quality control and inspection methods This phase is mostly lab work. It doesn't cost billions, but it requires sustained research funding. **Phase 2: Equipment Development (2-4 years)** Someone needs to build a commercial printer. This involves: - Integrating the laser, wire feeder, and motion control into a single system - Developing software for slicing models and controlling the process - Building multiple prototypes and testing with real customers - Regulatory certification for industrial equipment This phase might cost **$5-20 million**. It requires either a major equipment company (like Trumpf, SLM Solutions, or 3D Systems) or a well-funded startup. **Phase 3: Market Validation (2-3 years)** You need actual manufacturing companies trying this. Working out kinks. Proving that it delivers value in their specific applications. During this phase: - Early adopters test the technology on real parts - Process parameters get refined for specific applications - Cost structure becomes clear - Supply chains for tungsten carbide feedstock develop **Phase 4: Mainstream Adoption (5+ years out)** If all goes well, you get: - Multiple commercial printers available - Established best practices - Competitive pricing - Integration into standard manufacturing workflows Realistic timeline? We're probably looking at **2028-2030 before commercial equipment is available**. **2030-2035 before significant industrial adoption** in niche applications. <div class="definition-box"> <strong>Proof of concept:</strong> A demonstration that an idea is technically feasible. A proof of concept proves something *can* work, but not whether it's practical, cost-effective, or reliable enough for production use. </div> That might sound pessimistic. But consider the trajectory of other additive manufacturing technologies: - **3D Systems (Stereo Lithography)**: Invented 1984, commercially available 1988, mainstream adoption early 2000s - **Selective Laser Sintering**: Developed 1989, commercial 1992, industrial adoption 2000s - **Selective Laser Melting**: First research 1999, commercial 2006, significant adoption 2010s Additive manufacturing technologies consistently take **15-20 years from lab breakthrough to mainstream production use**. The softening method is on that timeline. ---  ## Why This Matters Beyond Tungsten Carbide This breakthrough is important not just for tungsten, but for what it signals about the future of manufacturing. For decades, additive manufacturing has pursued the same strategy: melt the material, cool it carefully, hope the result is good. This works okay for some metals, but it fundamentally struggles with ceramics, carbides, and composite materials. The softening approach opens a different door. What if additive manufacturing isn't always about melting? What if there are materials that bond better through pressure than through fusion? This has implications beyond tungsten: **Ceramic Matrix Composites**: These materials are used in jet engines and spacecraft. They're brittle and react badly to melting. Softening-based bonding might be the key to printing them. **High-Entropy Alloys**: These cutting-edge materials have complex phase diagrams. Rapid melting and cooling creates unpredictable microstructures. Controlled softening might enable more stable printing. **Graded Materials**: Imagine printing a tool where the cutting edge is diamond-hard tungsten carbide, but the base is slightly softer steel for shock absorption. Impossible to make traditionally. Potentially printable with softening methods. **Repair and Remanufacturing**: Instead of replacing worn tools, you could print new material onto the worn surface. The softening method might be better than fusion-based repair because it doesn't damage the substrate material. The bigger insight is this: **the future of additive manufacturing probably isn't one-size-fits-all**. Different materials need different printing strategies. Some work best with melting. Some work better with pressure and controlled heating. Some might require chemical bonding. Tungsten carbide was the proving ground for an entirely different approach. If it works here, it might work elsewhere too. <div class="fun-fact"> <strong>DID YOU KNOW:</strong> Some researchers are exploring ultrasonic vibration as an alternative to mechanical pressure for bonding metal layers in additive manufacturing. The vibration causes slight atomic movement that helps diffusion bonding. This is another "softening-based" approach that bypasses traditional melting. </div> ---   *Estimated data shows tungsten carbide 3D printing could capture a significant portion of the metal additive manufacturing market, potentially reaching 10% if adopted in key industries like aerospace.* ## Economic Impact: Material Waste and Manufacturing Efficiency Let's do the math on what this could mean economically if it scales. **Current Tungsten Carbide Supply Chain** The tungsten carbide tool industry produces roughly **50,000-100,000 metric tons** of finished tools globally per year. But that's the output. The input is much larger because of waste in traditional grinding. If we assume: - Average waste rate of **60%** in grinding - Tool material density of **14.95 g/cm³** - Average tungsten carbide price of **$25/kg** Then: $$\text{Total input material} = \frac{75,000\text{ tons}}{0.4} = 187,500\text{ tons}$$ $$\text{Waste volume} = 112,500\text{ tons}$$ $$\text{Annual waste value} = 112,500\text{ tons} \times \$25/\text{kg} = \$2.8\text{ billion}$$ Now, if 3D printing with softening technology could capture just **20%** of this market: $$\text{Recyclable waste value} = \$2.8B \times 0.20 \times 0.6 = \$336\text{ million}}$$ That assumes: - 20% market penetration for complex/high-value parts - 60% of wasted material is recoverable (some waste is dust that's hard to reclaim) That's potentially **$336 million annually** in recovered material value. Just from reduction in grinding waste. But there are additional benefits: **Design Efficiency**: Producing parts closer to final shape means less downstream finishing work. This could save another **10-15%** in total manufacturing cost. **Speed**: If 3D printing can be optimized to match grinding speed, that eliminates labor costs. For an operator making $50,000/year working with 100 inserts per day, each insert represents **$0.50 in labor**. Over 1 million inserts per year, that's **$500,000 in labor savings**. **Quality**: Fewer defects mean fewer warranty returns, less scrap during testing, better customer satisfaction. These are harder to quantify but often exceed the direct manufacturing savings. For a medium-sized tool manufacturer making **100,000 inserts per year**, the potential savings from adopting 3D printing tungsten carbide could be: $$\text{Annual Benefit} = \text{Waste reduction} + \text{Labor savings} + \text{Quality improvement}$$ $$= \$100K + \$50K + \$75K = \$225,000\text{ per year}}$$ If the equipment costs **$3 million**, payback time is about **13 years**. That's long, but when you factor in that equipment lasts 15-20 years and can produce thousands of different tool designs, the economics actually work. ---  ## Competing Technologies and Alternative Approaches Researchers aren't just pursuing the softening method. Other teams are working on different solutions to the same problem. **Cold Spray Deposition** This technology sprays metal particles at extremely high velocity (up to **500-1000 m/s**). The kinetic energy of impact bonds the particles together without melting them. *Advantage:* Works with almost any material, including carbides. Some success with tungsten carbide. *Disadvantage:* Equipment is expensive. Surface finish is rough. Density can be lower than bulk material. Still relatively immature technology. **Spark Plasma Sintering** This uses electrical pulses to sinter (bond) powder particles together. The electrical energy creates localized heating without full melting. *Advantage:* Proven for ceramic processing. Works with hard materials. *Disadvantage:* Not really "additive" in the traditional sense. It's more for consolidating powder. Geometry options are limited. **Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) and Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD)** These techniques deposit material atom by atom or layer by layer onto a substrate. PVD is commonly used to coat cutting tools. *Advantage:* Produces extremely uniform, defect-free material. *Disadvantage:* Extremely slow. You're talking millimeters of material per hour, not cubic centimeters. Building a 10-gram insert would take weeks. **Binder Jetting** This prints a liquid binder into a powder bed, creating a shape. The part is then sintered (heated to bond the particles) in a furnace. *Advantage:* Works with many materials including tungsten carbide. Some commercial success with carbide parts. *Disadvantage:* Sintering step creates warping and shrinkage. Can't achieve full density without hot isostatic pressing (additional expensive step). Complexity and cost limit adoption. Of all these alternatives, **the softening method** from Hiroshima University stands out because: 1. It produces near-full-density material without additional consolidation steps 2. Material properties match bulk material (not just "good enough") 3. It's conceptually simpler than some alternatives 4. It specifically solves the tungsten carbide problem that other methods struggle with It's not obviously superior to all alternatives for all applications, but for tungsten carbide specifically, it's the most promising breakthrough in years. ---  ## The Environmental Angle: Sustainability and Waste Reduction Here's something that doesn't get enough attention: manufacturing waste is an environmental problem. When you grind tungsten carbide to shape, you create fine dust. This dust is: - **Difficult to recycle**: Once ground into powder, it needs to be re-consolidated, which is expensive and energy-intensive - **Potentially toxic**: Tungsten carbide dust inhalation exposure creates occupational health issues. Proper handling requires expensive ventilation and dust collection - **Energy-intensive to extract in the first place**: Mining tungsten and processing it into carbide requires significant energy input If you could reduce grinding waste by **50-70%**, you'd: - Save energy in dust handling and ventilation - Reduce occupational health hazards - Decrease the amount of raw material that needs to be mined - Reduce the environmental impact of mining operations It's not glamorous, but it matters. The cutting tool industry is surprisingly resource-intensive when you look at the full supply chain. <div class="quick-tip"> <strong>QUICK TIP:</strong> Some cutting tool manufacturers are already implementing closed-loop recycling programs where tungsten carbide scrap is collected, re-processed, and used in new tool production. 3D printing could make this process more economical by reducing the scrap volume that needs recycling. </div> ---  ## What Researchers Are Working on Next The Hiroshima University team has shown that the softening method works. But they're not stopping there. Here's what the next phase of research probably looks like: **Geometry Expansion**: Developing process parameters that handle more complex shapes without cracking. This might involve new heating profiles, different nickel interlayer compositions, or post-processing stress relief. **Material Expansion**: Testing whether the softening method works for other carbides and ceramics. Titanium carbide, boron carbide, and silicon carbide are natural candidates. **Speed Optimization**: Finding ways to increase deposition rate without sacrificing quality. This might involve multiple heated wires running in parallel, or higher laser power with better thermal control. **Automation and Control**: Developing closed-loop feedback systems that monitor material quality during printing and adjust laser power and wire pressure in real-time. **Equipment Development**: Working with manufacturing equipment companies to commercialize the technology. This is where the technology becomes real. Other research groups are likely pursuing variations: - Different laser wavelengths or configurations - Alternative heating methods (induction heating instead of heated wire) - Different interlayer materials or compositions - Hybrid approaches combining softening with some melting This is healthy competition. Multiple approaches means at least one will probably succeed. ---  ## Real-World Implementation Challenges Let's talk about what actually happens when you try to scale this technology. **Quality Control** Manufacturers need to know that every part meets specifications. How do you inspect a 3D-printed tungsten carbide part? You can't use traditional eddy current testing (works for some metals, not for carbides). You probably need: - Ultrasonic inspection to detect internal cracks - Density measurement to verify minimal porosity - Hardness testing (but this is destructive) - X-ray or computed tomography for internal flaws All of these add cost and time to production. Developing fast, non-destructive quality control methods is crucial for commercial viability. **Reproducibility** Manufacturing needs reproducible results. If printer A produces different hardness than printer B, or if results vary between units on the same printer, manufacturers won't trust the process. This requires: - Tight control over laser parameters - Precision calibration of heated wire temperature - Stable atmospheric conditions (humidity, temperature) - Detailed documentation of process parameters It sounds simple but is actually quite hard. Small variations in laser power (1-2%) can affect final hardness measurably. **Training and Expertise** Operating this equipment requires expertise. You need people who understand: - The physics of laser heating and material softening - How tungsten carbide behaves under different conditions - Troubleshooting when things go wrong There's a shortage of people with this knowledge. Companies would need to invest in training programs. **Supply Chain Integration** Currently, tungsten carbide feedstock for 3D printing doesn't exist as a commercial product. You'd need: - Suppliers providing tungsten carbide rods in the right specifications - Consistent material composition (cobalt content, grain size, etc.) - Quality certifications - Reliable supply at industrial scale This might sound trivial but it's actually a significant barrier. Getting suppliers to invest in new feedstock production requires confidence that there will be demand. ---  ## A Realistic Assessment: When Will This Actually Matter? Let me be blunt. This is a breakthrough in the lab. It might not become a breakthrough in manufacturing. History is full of technologies that worked perfectly in academic settings but never became commercially viable. They were too expensive, too slow, too difficult to control, or solved a problem that wasn't big enough to justify the investment. For tungsten carbide 3D printing to actually change manufacturing, several things need to happen: 1. **Equipment needs to be reliable and reproducible** at a level that matches or exceeds traditional manufacturing 2. **Economics need to work** not just theoretically but in real production facilities with real overhead costs 3. **Someone needs to invest** $50-200 million to develop commercial equipment and build market demand 4. **Customers need to see value** significant enough to justify switching from proven processes Any of these could be a blocker. That said, the potential is real. If even one of the planned applications (cutting tools, drill bits, aerospace components) successfully adopts this technology, it could create a market worth **hundreds of millions of dollars annually**. The most likely near-term adopter is probably aerospace, where extreme hardness requirements and design complexity make the benefits clearest. A single component that required traditional manufacturing but could be printed in a week instead of a month would demonstrate value immediately. <div class="fun-fact"> <strong>DID YOU KNOW:</strong> The global additive manufacturing market was valued at approximately $15-20 billion in 2024 and is growing at 10-15% annually. Metal additive manufacturing represents only about 25-30% of that market, but it's the fastest-growing segment. Tungsten carbide could represent a significant new category within metal AM. </div> ---  ## Key Takeaways and Looking Forward Let's summarize what actually matters here: **The Achievement**: Scientists at Hiroshima University demonstrated that tungsten carbide can be 3D printed using softening rather than melting, producing material with hardness and properties comparable to bulk tungsten carbide. **The Method**: Using a pulsed laser and heated wire, combined with nickel interlayers, the process bonds tungsten carbide layers without full melting. This avoids the cracking, porosity, and decomposition that plague traditional laser-melting approaches. **The Potential**: If scaled, this could reduce waste in tungsten carbide tool manufacturing, enable complex geometries, and create new design possibilities. Economic benefits could exceed **$100 million annually** if significant market adoption occurs. **The Reality**: The technology is still in early research phases. Cracking issues remain in complex geometries. Speed is too slow for high-volume production. No commercial equipment exists yet. Industrial adoption is probably 5-10 years away, not months. **The Broader Significance**: This proves that softening-based bonding can work for extremely hard materials. The approach might extend to other ceramics and carbides, opening new possibilities for additive manufacturing beyond traditional melting-based methods. **The Honest Assessment**: This is a legitimate breakthrough with real potential, but it's not going to transform manufacturing overnight. It requires sustained research, significant investment, and careful development to move from lab achievement to industrial reality. Watching this technology mature over the next 5-10 years will be interesting. If the team can solve the cracking and speed issues, if they can commercialize the approach, and if customers actually adopt it, this could genuinely change how hardened materials are manufactured. If not, it's still a valuable research contribution that proves new manufacturing approaches are possible. Either way, it's one of the more interesting breakthroughs in additive manufacturing in recent years. ---  ## FAQ ### What exactly is the softening method in tungsten carbide 3D printing? The softening method heats tungsten carbide just enough to make it malleable without fully melting it. A pulsed laser and heated wire apply controlled heat while pressing layers together mechanically. Thin nickel alloy layers between tungsten carbide layers act as bonding agents. This approach avoids the cracking, porosity, and chemical decomposition that occur when tungsten carbide is fully melted and cooled rapidly. ### How is this different from traditional 3D metal printing like SLM? Traditional selective laser melting (SLM) fully melts powder particles and relies on cooling to solidify them. This creates thermal stress, phase changes, and defects in hard materials like tungsten carbide. The softening method avoids full melting entirely, using mechanical pressure to bond softened material instead. The key difference is philosophical: instead of melting and controlling cooling, this method uses controlled heating and pressure to achieve bonding. ### What hardness does the printed tungsten carbide achieve? The printed material reaches hardness values over 1400HV (Vickers Hardness), which matches bulk tungsten carbide material. This is comparable to sapphire (1600-2200HV) and only slightly below diamond (5000-10000HV). The remarkable achievement is that 3D-printed tungsten carbide now performs at the same hardness level as traditionally manufactured material, which was previously impossible. ### What are the main limitations preventing immediate industrial use? Three major limitations exist: First, cracking occurs in complex geometries and certain shapes, restricting design freedom. Second, the printing speed is too slow for high-volume production—currently producing only 1-2 cm³ of material per hour. Third, there's no commercial equipment available; the process requires custom-built systems that don't exist yet. Additional work is needed to solve each of these challenges before industrial adoption becomes practical. ### When will this technology be available for manufacturing companies to use? A realistic timeline suggests commercial equipment might become available around 2028-2030, with significant industrial adoption possibly occurring 2030-2035. This follows the typical trajectory of additive manufacturing technologies, which usually take 15-20 years from lab breakthrough to widespread production use. Early adopters in aerospace or specialized tool manufacturing might adopt sooner, while broader adoption requires solving cracking issues and improving speed. ### Could this softening method work for materials other than tungsten carbide? Yes, the softening approach appears applicable to other hard ceramics and carbides like titanium carbide, boron carbide, and ceramic composites. However, each material requires developing new process parameters because different materials have different softening temperatures, bonding characteristics, and stability requirements. Research is ongoing to extend this method beyond tungsten carbide, but it's early-stage work with limited published results. ### What are the economic benefits if this technology scales successfully? Traditional tungsten carbide manufacturing wastes 50-80% of raw material through grinding. If 3D printing can capture even 20% of this market, the recovered waste value alone could exceed $300 million annually. Additional benefits include reduced labor costs (no grinding operations), improved material efficiency, and potential design improvements. For individual manufacturers, adoption could save $100,000-$500,000 annually depending on production volume and product complexity. ### Why does the nickel interlayer matter so much in the printing process? The nickel interlayer serves multiple critical functions: it provides mechanical bonding between tungsten carbide layers, it accommodates thermal stress differences between layers, and it improves wetting and adhesion. Cobalt (the traditional binder in tungsten carbide) doesn't work as well in this process. Nickel's different metallurgical properties solve interface problems that wouldn't be obvious without testing. This small detail is actually crucial to making the overall process work reliably. ### Is this better than other emerging tungsten carbide manufacturing methods? Compared to alternatives like cold spray deposition, binder jetting, and chemical vapor deposition, the softening method stands out because it produces near-full-density material matching bulk properties without additional consolidation steps. Cold spray works but requires expensive equipment and produces rough surfaces. Binder jetting requires expensive sintering and hot isostatic pressing steps. Chemical vapor deposition is too slow for practical manufacturing. For tungsten carbide specifically, the softening method is currently the most promising approach, though it's not universally superior to all alternatives for all applications. ### What environmental benefits does this technology offer? Grinding tungsten carbide creates fine dust that's difficult to recycle and creates occupational health hazards. 3D printing with 50-70% less waste would reduce dust handling costs, improve worker safety, and decrease the amount of raw tungsten that needs to be mined. If adopted widely, this could significantly reduce the environmental impact of cutting tool manufacturing. Additionally, reduced material waste means less energy consumption in both the manufacturing and mining stages of tungsten carbide production. ---  ## Conclusion: A Breakthrough with Real Potential and Real Obstacles The tungsten carbide 3D printing breakthrough from Hiroshima University is genuinely significant. For years, scientists couldn't print one of the world's hardest materials without destroying its properties. Now they can. The material properties match bulk tungsten carbide. The defects are minimal. The proof is there. But proving something works in the lab is radically different from making it work in manufacturing. Speed needs improvement. Cracking issues need solving. Commercial equipment doesn't exist yet. The economic case still needs validation. What excites me about this breakthrough isn't that 3D-printed tungsten carbide tools will be everywhere in 2026. They won't be. What's exciting is that it proves a new approach to manufacturing extremely hard materials is possible. If the softening method works for tungsten carbide, it probably works for other hard materials too. That opens possibilities that were previously closed. The next five years will tell us whether this lab breakthrough becomes a manufacturing revolution or joins the long history of promising technologies that never quite made the jump to production. Given the economic potential and the genuine technical achievement, I'd bet on it eventually succeeding, even if it takes longer than optimists hope. Watch this space. Something interesting is happening in manufacturing, and it might just change how we make the hardest materials we rely on.  ## Related Articles - <a href="https://tryrunable.com/posts/tesla-is-no-longer-an-ev-company-elon-musk-s-pivot-to-roboti" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Tesla is No Longer an EV Company: Elon Musk's Pivot to Robotics [2025]</a> - <a href="https://tryrunable.com/posts/elegoo-centauri-carbon-2-combo-3d-printer-review-2025" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Elegoo Centauri Carbon 2 Combo 3D Printer Review [2025]</a> - <a href="https://tryrunable.com/posts/electrides-the-mysterious-materials-hiding-earth-s-missing-e" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Electrides: The Mysterious Materials Hiding Earth's Missing Elements [2025]</a> - <a href="https://tryrunable.com/posts/boston-dynamics-atlas-robot-the-future-of-factory-automation" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Boston Dynamics Atlas Robot: The Future of Factory Automation [2025]</a> - <a href="https://tryrunable.com/posts/gate-all-around-transistors-how-ai-is-reshaping-chip-design-" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Gate-All-Around Transistors: How AI is Reshaping Chip Design [2025]</a> - <a href="https://tryrunable.com/posts/amazon-s-bacterial-copper-mining-deal-what-it-means-for-data" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Amazon's Bacterial Copper Mining Deal: What It Means for Data Centers [2025]</a>

![Tungsten 3D Printing Breakthrough: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tungsten-3d-printing-breakthrough-what-you-need-to-know-2025/image-1-1770854825850.png)