Introduction: When Becoming Chinese Became Ironic Cool

Somewhere between the tariff wars, the Tik Tok debates, and the endless scroll through Shein hauls, something shifted in how Americans talk about China. It wasn't a policy paper or a think tank report that marked this moment. It was a Tik Tok trend.

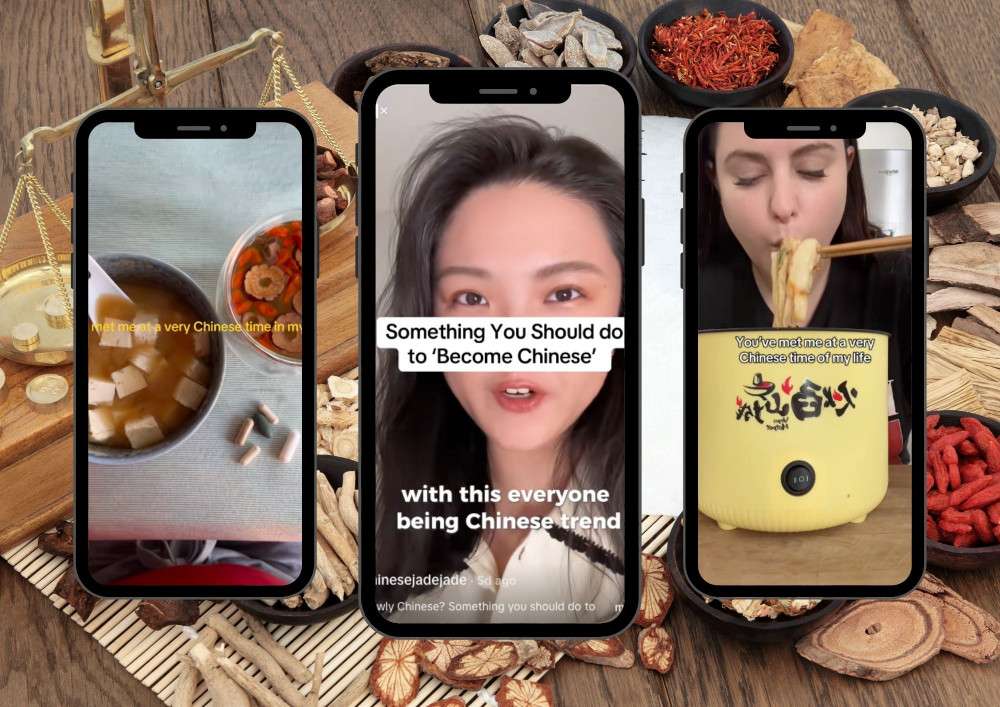

People started saying things like "You met me at a very Chinese time of my life," usually while performing something absurdly mundane that they'd coded as Chinese. Eating dim sum. Wearing an Adidas jacket with Chinese characters. Ordering from DHGate instead of Amazon. The meme exploded so fast that celebrities like Jimmy O Yang and Hasan Piker jumped in. Then it evolved. "Chinamaxxing" became the term for optimizing your life according to perceived Chinese efficiency. "You will turn Chinese tomorrow" became a blessing, a joke, a weird form of hope.

This wasn't really about China, of course. Not the actual country. Not the 1.4 billion actual Chinese people. This was about something much more specifically American: a collective realization that the world's most advanced infrastructure, the most efficient cities, the most impressive technological innovation, and yes, even the most functional government planning were increasingly happening somewhere else. And younger Americans were processing that fact the only way they knew how. Through irony. Through memes. Through playfully claiming they were becoming Chinese, because clearly, China had figured something out that America hadn't.

The trend represents something deeper than internet humor. It's a window into generational anxiety, a mirror held up to American decline, and a genuine reassessment of what Americans actually believe about technology, efficiency, and modernity. It's also proof that the narratives we tell about other countries say far more about ourselves than about them.

This is the story of what the "very Chinese time" meme actually means, why it caught fire, what real Chinese people think about it, and what it says about American culture in 2025.

TL; DR

- The meme isn't about China: It's a projection of American anxieties about infrastructure, technology, and national decline onto an abstraction called "China."

- Younger Americans consume more Chinese products than ever: From Tik Tok to Shein to Chinese-made phones, daily life is now deeply entangled with Chinese manufacturing and technology.

- It's aspirational Orientalism: Unlike past stereotyping, this trend treats China as a model to admire rather than mock, which is a fundamental cultural shift.

- Language barriers are collapsing: AI translation tools now let Americans engage directly with Chinese content and commerce without intermediaries.

- Real Chinese people are mixed on it: Some appreciate the admiration, while others feel their identity is being reduced to stereotypes and shallow performative gestures.

- The meme exposes American decline: When people joke about "becoming Chinese," they're really saying America doesn't work like it used to.

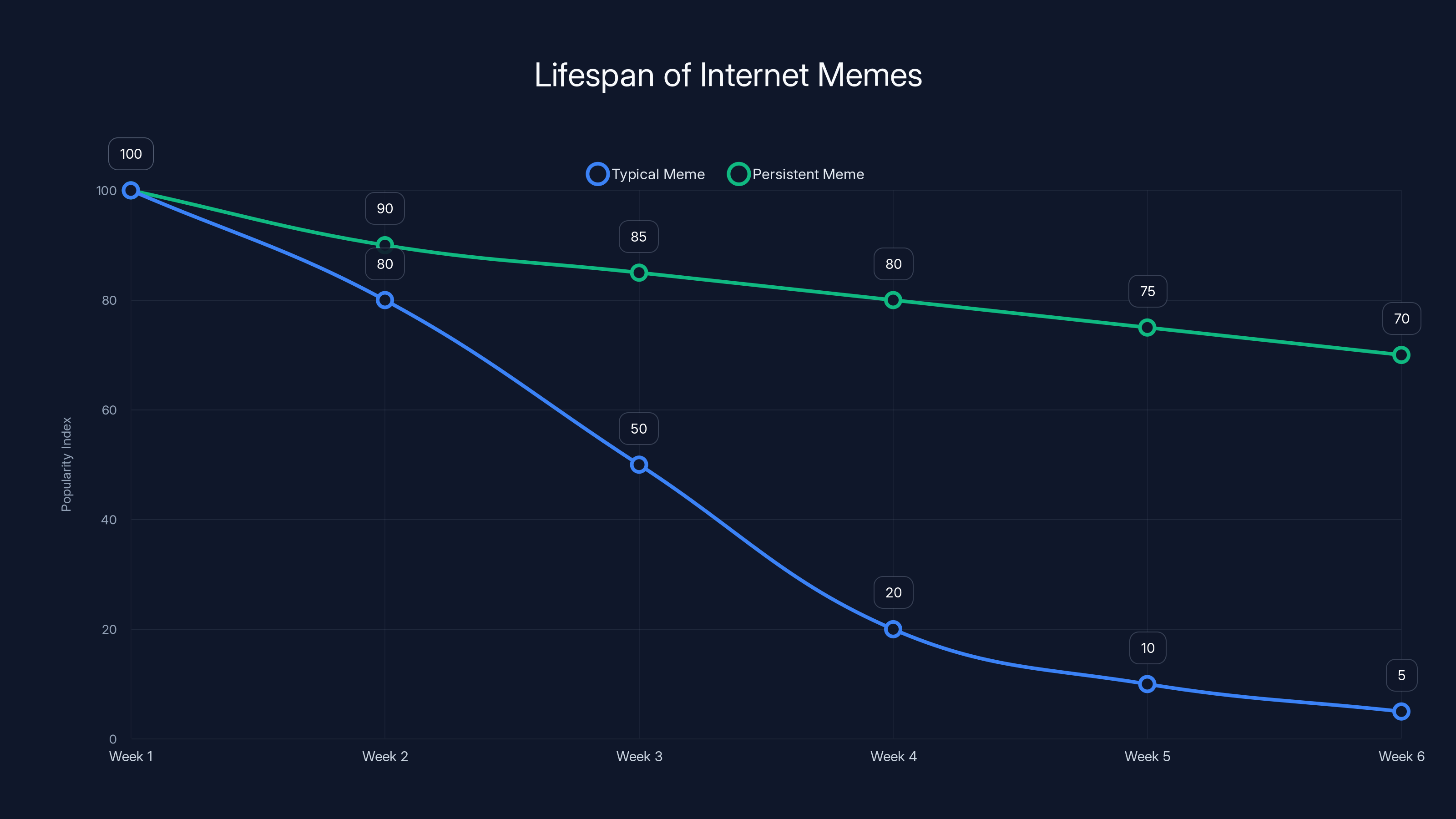

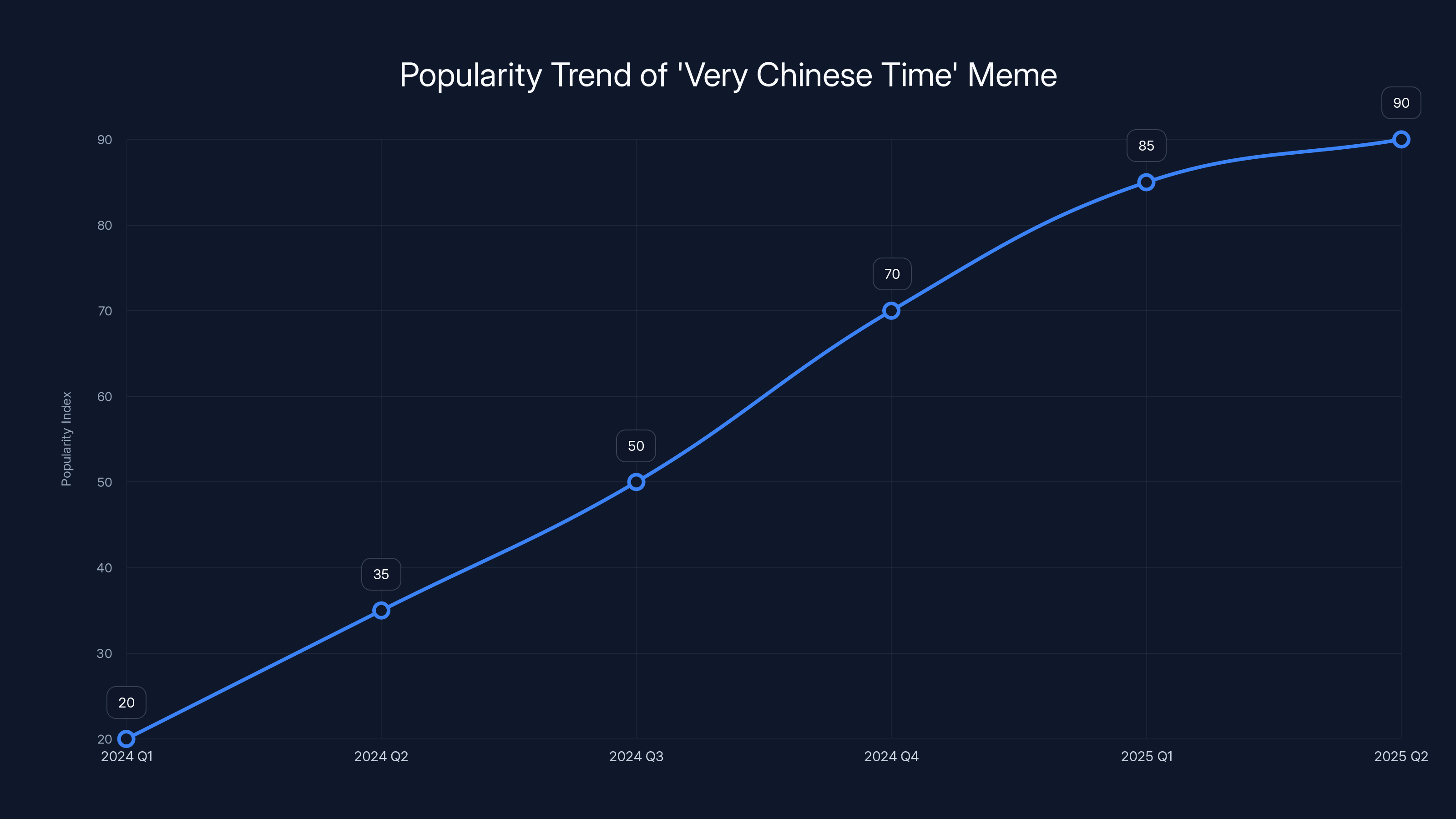

Persistent memes maintain higher popularity over time compared to typical memes, which quickly decline. Estimated data.

Understanding The Meme: More Than Just A Joke

Memes usually die within weeks. They trend, they peak, then they dissolve into the infinite archive of forgotten internet culture. But some memes persist because they tap into something real, something that audiences are genuinely processing. The "very Chinese time" meme is one of those.

The core format is deceptively simple: someone performs an action or describes a lifestyle choice, then adds "You met me at a very Chinese time of my life." This phrase, borrowed from the opening monologue of "Fight Club," creates an ironic distance. The movie uses it to describe a moment of moral breakdown. The meme uses it to describe buying a knock-off phone or eating Asian food.

But here's where it gets interesting. The phrase doesn't imply shame or self-deprecation in the way earlier memes might have. Nobody's mocking themselves for consuming Chinese products or admiring Chinese infrastructure. They're claiming identity with it. There's a lightness to it, even a pride.

Variations evolved quickly. "Chinamaxxing" suggests optimizing every aspect of life toward Chinese efficiency standards. Using a Chinese app. Buying Chinese-made clothes. Prioritizing function over aesthetics. Learning Mandarin. The term "maxxing" comes from incel culture, where it meant optimizing for a specific outcome. But in this context, it lost its misogynistic baggage and just meant "going hard on something."

Then came "u will turn Chinese tomorrow," which flipped the script entirely. Instead of a claim about yourself, it became a blessing or affirmation you could give to others. It's almost spiritual. Like you're acknowledging that someone's future holds a better, more efficient version of themselves.

What makes this different from past internet trends is the absence of irony-as-mockery. Nobody's making fun of Chinese culture. They're not doing exaggerated accents or leaning into stereotypes in that gross, Breakfast-at-Tiffany's kind of way. They're genuinely expressing admiration, tinged with the protective irony that Gen Z uses whenever they're being sincere about something.

The meme also works because it's inclusive. Anyone can participate. You don't need Chinese heritage. You don't need to speak Mandarin. You don't even need to have traveled to China. You just need to consume Chinese products, which, in 2025, is basically everyone on Earth.

The Actual Origins: How The Phrase Got There

The "very [nationality] time of my life" format didn't start on Tik Tok. It's actually a reference to Tyler Durden's opening monologue in "Fight Club," where he describes a moment of existential crisis and moral ambiguity as "a very interesting time of my life."

Applying Fight Club references to current events is basically a tradition at this point. The movie's anti-establishment, anti-consumerism messaging makes it perpetually relevant to internet culture, especially among younger people who feel alienated from their own country's institutions.

But the specific application to China emerged gradually. Around late 2024, as discourse about Chinese technology, tariffs, and supply chains intensified, people started using this template to describe their relationship with Chinese products and culture. Someone would post a Tik Tok of themselves using a Chinese app, or wearing clothes from Shein, and say "You met me at a very Chinese time of my life."

The genius of the format is that it works on multiple levels simultaneously. On the surface, it's absurdist humor. The implication that your life has phases, and this phase happens to be "the Chinese one," is ridiculous enough to make people laugh.

But underneath, it's doing real work. It's processing a genuine shift in American reality. For decades, American companies controlled the narrative about consumption, technology, and modernity. You bought American brands. You used American apps. American infrastructure was (supposedly) the best in the world.

That story broke. Kids in 2025 realize they can't afford American apartments. They use Tik Tok, which is Chinese. They buy from Shein, which is Chinese. They're looking at Chinese high-speed trains and Chinese solar installations and Chinese electric vehicles and wondering why their own country seems incapable of doing those things.

The meme lets them express that realization without sounding like they're surrendering. It's ironic, so they're protected. It's a joke, so they can't be called un-American. But it's also sincere. The best memes always are.

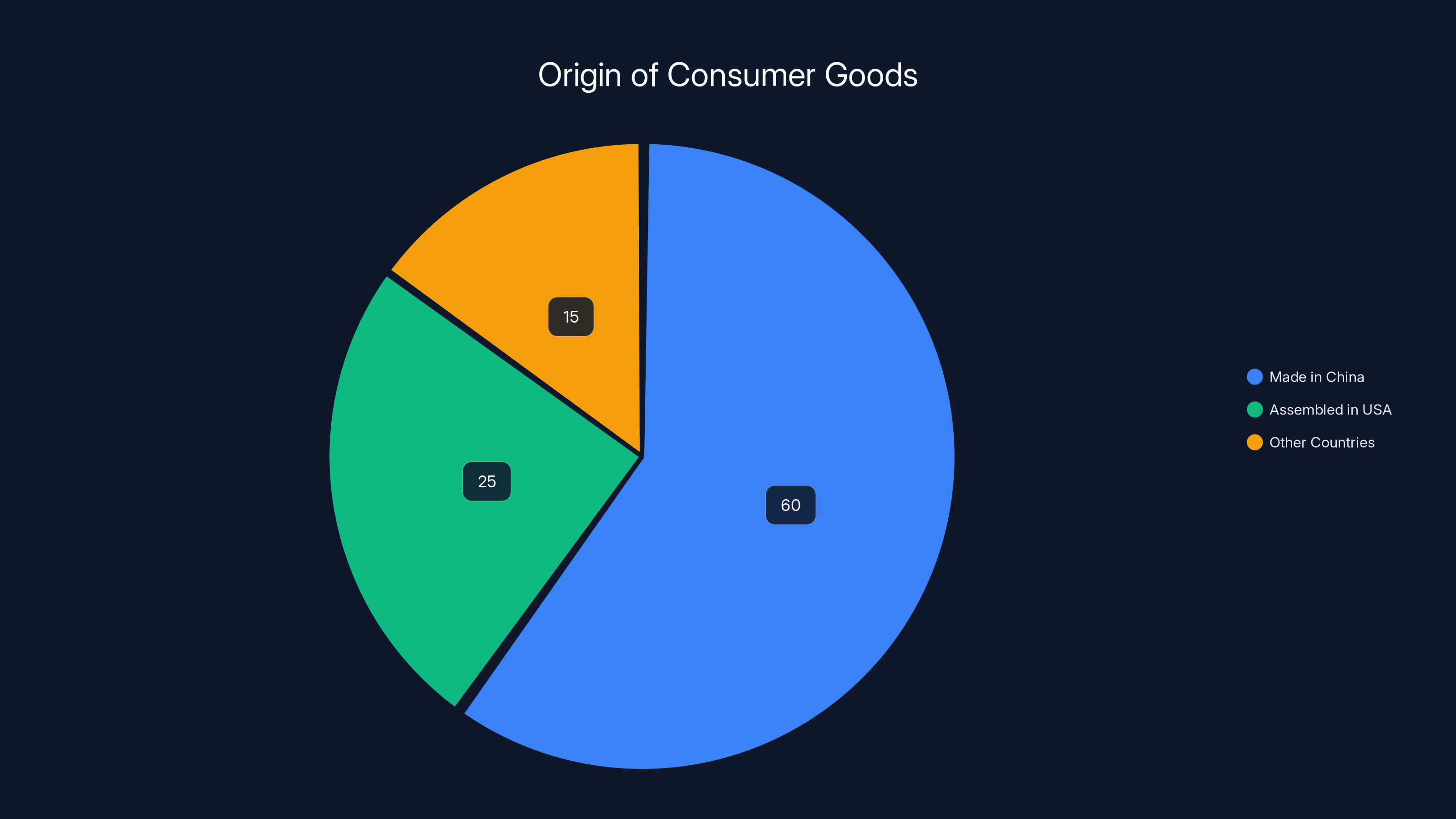

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of consumer goods are manufactured in China, highlighting global supply chain dependencies.

Why China? The Geopolitical Context Behind The Trend

The meme didn't emerge in a vacuum. It arrived at a very specific moment in American-Chinese relations and American domestic politics.

For the past decade-plus, China existed in American discourse primarily as a threat. Politicians warned about espionage. Media outlets reported on human rights concerns. The Trump administration implemented tariffs. The Biden administration expanded export controls on advanced chips. There was a sense that China was an adversary, a monolithic communist superpower that wanted to dominate the world.

But something strange happened. As American politics became increasingly chaotic, as democratic norms eroded, as infrastructure crumbled, and as economic inequality became impossible to ignore, people started looking around and comparing notes. And when they looked at China, they saw something different.

They saw functioning cities. High-speed trains that ran on time. Infrastructure projects that got completed. A government that could actually build things, whether or not you agreed with how it governed.

This wasn't coming from China experts or policy analysts. It was coming from regular people scrolling social media, noticing that the country they'd been told to fear seemed, from a distance, to actually work.

The shift accelerated when people realized how dependent they actually were on Chinese manufacturing. During the pandemic, supply chain issues made this visceral. Then came tariffs. Suddenly, Americans realized that "American" products weren't actually American. They were designed in America, manufactured in China, and the actual value was being extracted by Chinese factories.

Apps like DHGate and Shein opened direct channels to Chinese manufacturers. Instead of going through Walmart or Amazon, you could deal directly with the factory. Language barriers fell away thanks to increasingly sophisticated translation tools. The mystique around "made in China" shifted. It became a signal of cost-efficiency and direct access, not cheap knock-offs.

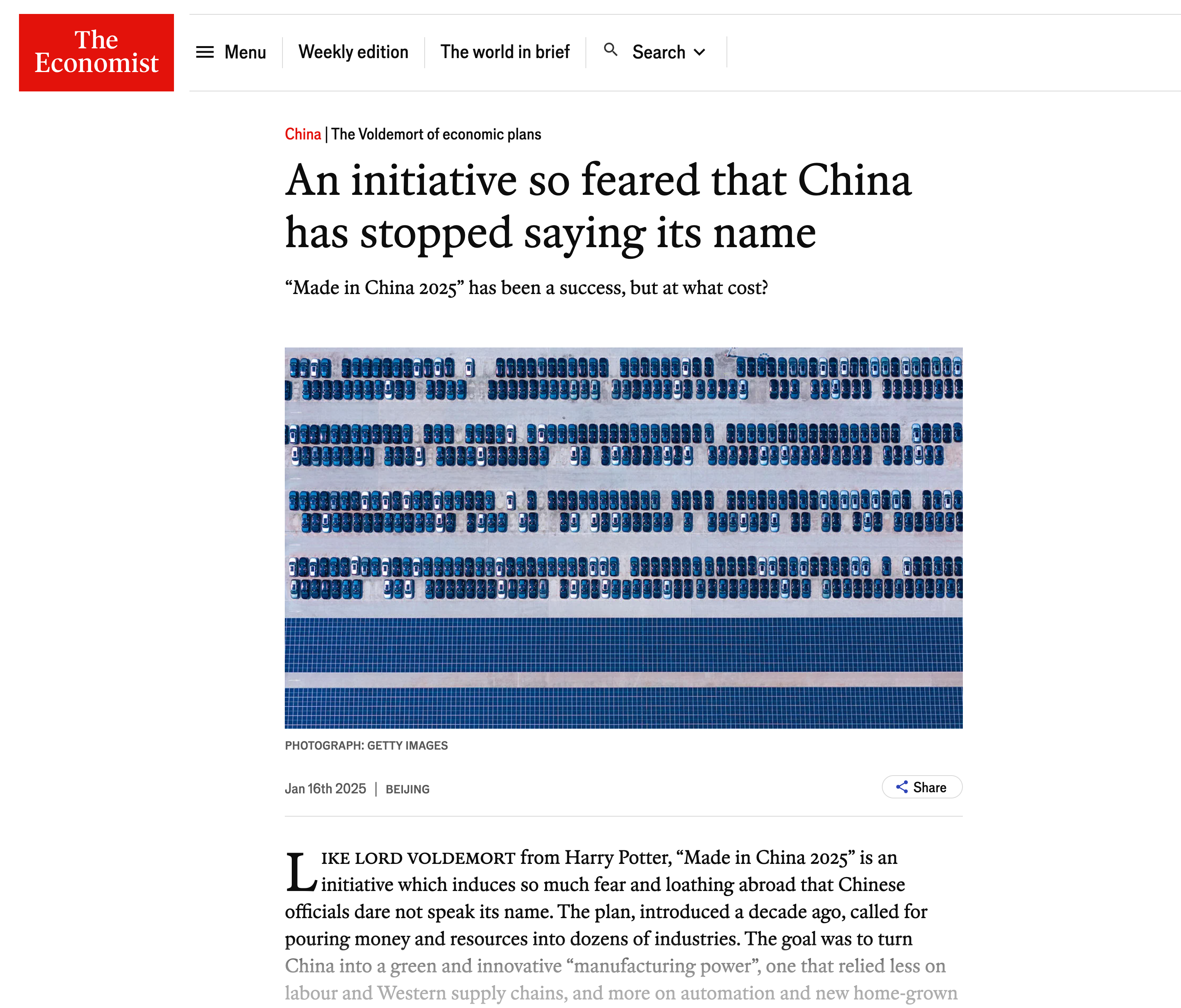

At the same time, Chinese apps like Tik Tok were dominating American teenagers' screen time. Chinese electric vehicles like BYD were becoming the world's largest EV manufacturer. Chinese companies were leading in battery technology, solar panels, and renewable energy. The narrative that America was inevitable, that capitalism was the obvious system, that Western technology was obviously superior, became harder to maintain.

Into this void, the meme arrived. It offered a way to process this cognitive dissonance. To acknowledge that maybe China had figured something out. To express admiration, even aspiration, for a different model, without renouncing American citizenship or joining any political movement. Just a joke. Just a very Chinese time.

The Infrastructure Paradox: Why Americans Notice China's Trains More Than Their Own

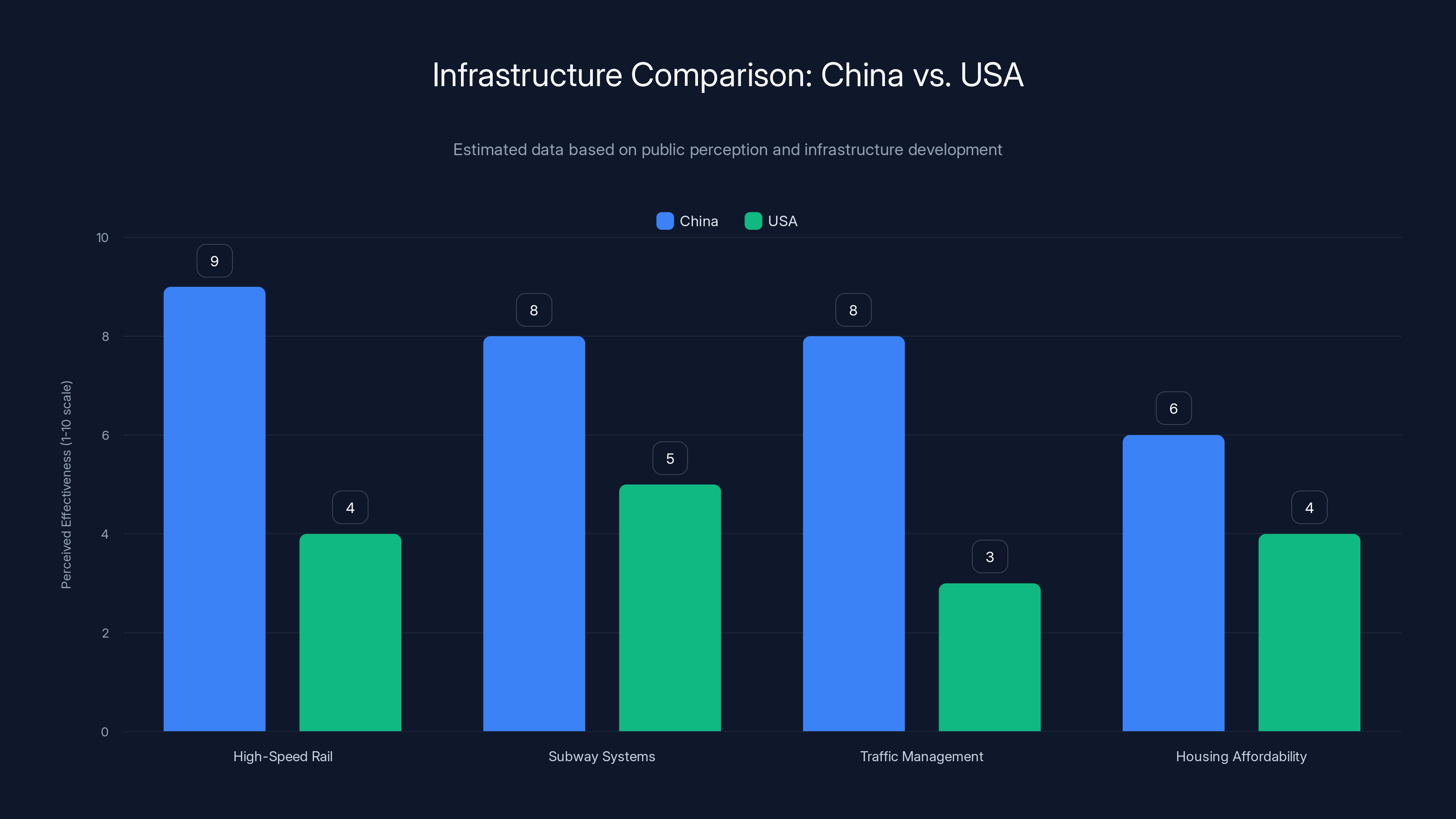

One of the most common things you see in the discourse around "becoming Chinese" is the infrastructure comparison. Americans point to China's high-speed rail network, its subway systems, its metro areas with 20+ million people that function without falling apart.

Then they look at America. A country that had the political will to go to the moon, that built the Interstate Highway System, that created the foundation for the modern digital economy. That same country now can't fix its roads, can't build adequate transit, can't manage its airports without constant delays.

The contrast is real enough that it's become a meme generator itself. Comparisons between an American train and a Chinese train. Comparisons between traffic management in Shanghai versus Los Angeles. Comparisons between apartment prices in Beijing versus New York City.

What's important to understand is that these comparisons aren't always fair. China's high-speed rail network is impressive, but it was built by a government that could relocate people without asking permission, that could acquire land without lengthy legal processes, that could implement long-term planning without worrying about election cycles.

America's infrastructure, by contrast, has to navigate democracy. Property owners can sue. Environmental impact statements take years. Multiple levels of government have to agree. Once something is built, you often can't modify it for decades.

But here's the thing: younger Americans aren't really comparing systems fairly. They're not doing a sophisticated analysis of governance trade-offs. They're looking at their own reality, which includes aging infrastructure, crumbling transit systems, and expensive, inadequate housing. And they're looking at images of Chinese cities, which look gleaming, futuristic, and functional by comparison.

The emotional reality matters more than the factual reality. When your commute is terrible and you see images of Chinese trains that run on time, you notice. When you can't afford an apartment and you read about Chinese mega-cities accommodating millions, you notice.

This is where the meme functions as a kind of collective processing of relative decline. Not actual decline, necessarily, but relative decline. A generation that grew up being told America was the best is realizing that might not be true anymore. China's infrastructure isn't just better in some cases. It's better in ways that actually affect daily quality of life.

The Technology Gap: Apps, Phones, And Direct Access

One of the least discussed but most important reasons the "very Chinese time" meme resonates is that technology has made Chinese products accessible and, frankly, good in ways they weren't before.

Ten years ago, if you wanted a product from China, you either had to buy it through Amazon or Ebay, marked up by intermediaries. The quality was often terrible. The knock-offs were rampant. The only reason to buy something "made in China" was because it was cheap. It was a consolation prize, not a preference.

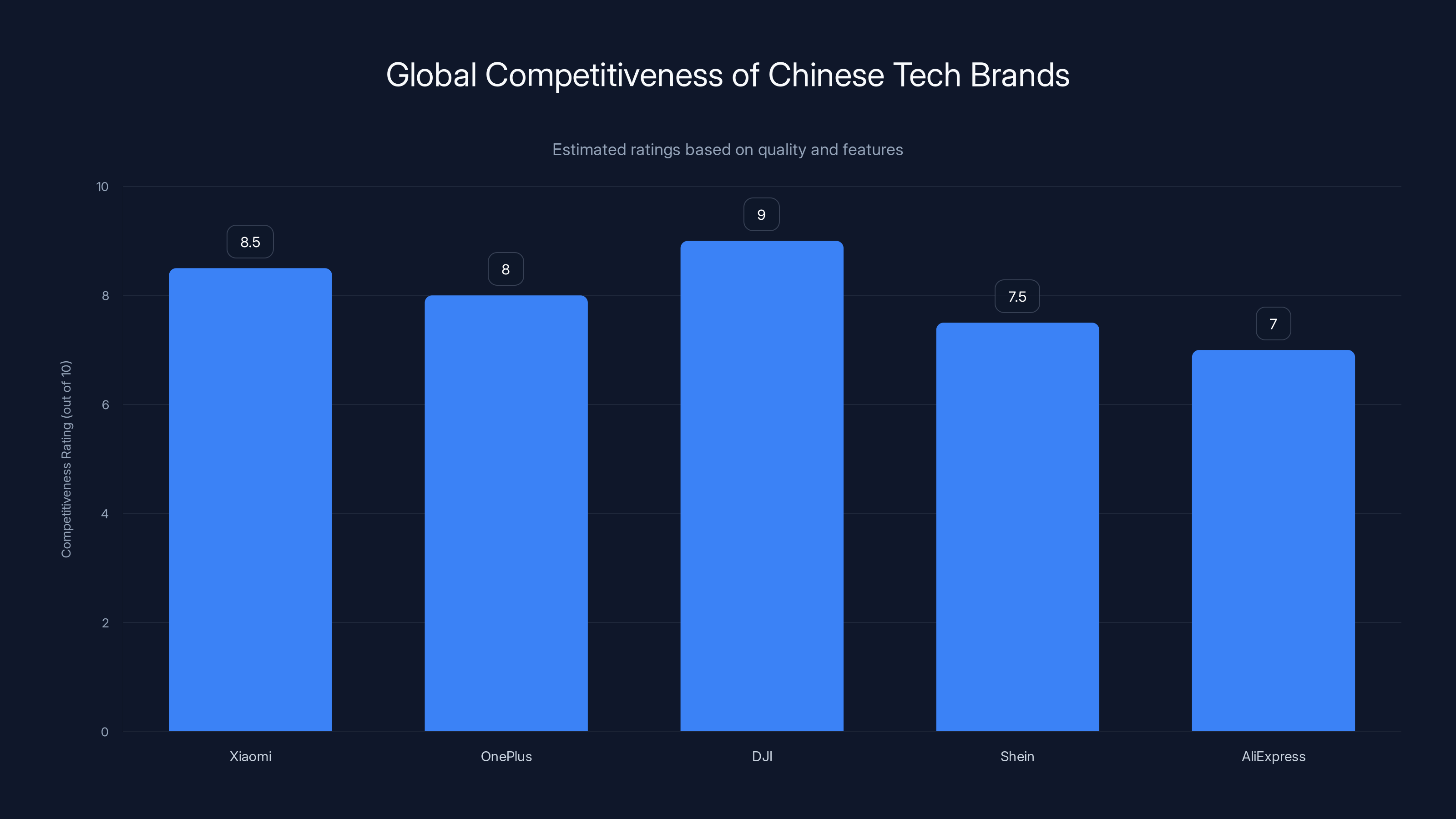

Now, things are different. Chinese companies like Xiaomi, One Plus, and DJI are genuinely competitive on the global market. They're not cheap knockoffs. They're legitimate products that compete on quality and features.

Apps like Shein democratized access to Chinese fashion manufacturing. DHGate connects you directly to factories. Ali Express lets you browse products from tens of thousands of Chinese manufacturers. These aren't black market sites. They're legitimate e-commerce platforms.

Tik Tok, which is Chinese-owned (by Byte Dance), became the dominant social media platform for American teenagers. Not because Americans care that it's Chinese, but because it's simply better at recommendation algorithms, content discovery, and user engagement than American alternatives.

They're using a Chinese app, probably on a Chinese-made phone (whether it's a Xiaomi or a Pixel, which has significant Chinese components), wearing clothes from Chinese manufacturers, and consuming content from Chinese creators.

The key shift is that language is no longer a barrier. Translation tools have become so sophisticated that you can read Chinese product descriptions, watch Chinese tutorials, join Chinese communities, all without understanding a word of Mandarin. You just click translate.

This creates a situation where the average American is now directly exposed to Chinese quality, Chinese design aesthetics, and Chinese consumer culture, often for the first time. And they're forming opinions based on direct experience, not media narratives.

Shein is a perfect example. A decade ago, American fashion was dominated by fast fashion chains like H&M and Forever 21. Shein arrived and offered even cheaper, faster fashion, with a direct supply chain to Chinese manufacturers. Older Americans might look at Shein as cheap and disposable. Gen Z looks at it as efficient and accessible.

When you add this up, the average American's daily consumption now involves Chinese technology, Chinese manufacturing, and Chinese apps in ways that would have been unimaginable in 2010. The "very Chinese time" meme is just articulating this new reality that people are living, but can't quite process.

China's infrastructure is perceived as more advanced and effective compared to the USA, particularly in high-speed rail and traffic management. (Estimated data)

Language Barriers Collapse: AI Translation Changes Everything

One of the invisible enablers of the "very Chinese time" trend is the collapse of language barriers through AI translation.

Five years ago, if you wanted to buy something from a Chinese manufacturer, you faced a problem. The product listing was in Chinese. The reviews were in Chinese. The instructions were in Chinese. You could use Google Translate, but the results were often awkward or inaccurate. It created friction.

Now, modern large language models can translate Chinese to English (and vice versa) with remarkable accuracy. More importantly, they can capture nuance, idiom, and context. A Chinese joke translates as a Chinese joke, not as a weird artifact of bad translation.

This sounds like a small technical detail, but it's actually profound. When language barriers drop, cultural barriers drop with them. You can suddenly engage with Chinese content, Chinese creators, Chinese products, and Chinese communities on their own terms, without needing an intermediary to explain or filter it.

Apps like Red Note (Xiaohongshu), which is primarily a Chinese social network for shopping and lifestyle content, traditionally struggled to attract international users because everything was in Chinese. But in 2024-2025, when Americans decided to check it out, they discovered they could just press translate and suddenly have access to an entirely different visual culture.

They saw how Chinese creators were doing aesthetics, design, fashion, and lifestyle differently. And instead of being mysterious or other, it just felt like a different platform with different people. Which, in a way, normalized Chinese culture in a new way.

Tik Tok's success in America is partially because it doesn't require language proficiency to understand most content. A video of someone making food is a video of someone making food, regardless of what language is being spoken. And because Tik Tok's algorithm is so good at recommendation, American users started getting recommended content from Chinese creators, in English translations, without seeking it out.

The cascade effect of this is that Chinese creators got access to massive American audiences. Chinese musicians, designers, artists, and entrepreneurs suddenly had platforms where millions of Americans could see their work, understand it, and engage with it. Some became minor celebrities.

This reversal of typical media flow is itself notable. For decades, American culture flowed outward, was consumed globally, and served as the template for aspiration. Now, Chinese creators are gaining audiences in America, not because America is forced to care, but because the content is interesting and the algorithm is pointing people toward it.

Translation technology also enabled the direct commerce angle. You can now order from Ali Express or DHGate with relative confidence that you understand what you're getting, because images and translated text are sufficient for most consumer products. This removed a major barrier to consumption.

What all of this adds up to is a situation where Americans are increasingly engaging with Chinese culture, Chinese creators, and Chinese commercial products, without needing any special knowledge or effort. It's just part of normal internet usage now. And the meme is a way of acknowledging that this is strange and new and interesting.

Manufacturing Reality: The Supply Chain Awakening

For most of American consumer history, people didn't think about where things came from. Things appeared on store shelves, branded with American company names, and that was sufficient. The fact that they were manufactured elsewhere was abstracted away.

The pandemic broke this abstraction. Suddenly, supply chains became a dinner table conversation. People realized that everything they owned was either made in China or dependent on Chinese components or materials.

Then came tariffs. The Trump administration's trade war forced Americans to confront an uncomfortable reality: the stuff you buy branded as American isn't actually American. It's assembled in America, designed in America, sold by American companies, but made in China.

Moreover, when tariffs hit, prices went up. The cost of goods reflected the fact that you were buying from American retailers who were buying from Chinese manufacturers. Cut out the middleman and you could get the same product for less.

Apps like DHGate and Ali Express allow consumers to do exactly that. You're buying directly from the factory. No retail markup. No supply chain bloat. Just manufacturer to consumer.

This created a strange situation where buying directly from Chinese manufacturers became more economical than buying from American retailers. And buying from Chinese retailers became cheaper than buying American brands.

The realization sank in: there is no such thing as "made in America" anymore. There's designed in America and manufactured in China. And sometimes, manufactured in China is actually better and cheaper.

This isn't unique to consumer goods. It applies to almost everything. Your phone was designed by an American company (or a Chinese company, depending on the brand) but manufactured in China. Your clothes were designed somewhere but likely made in China. Your furniture, your appliances, your electronics, your cheap plastic toys, your expensive athletic wear. All roads lead to China.

What the "very Chinese time" meme does is articulate this realization in a way that's culturally legible. You're not just buying Chinese products. You're participating in a Chinese manufacturing ecosystem. You're participating in a Chinese commercial culture. You're being served by Chinese algorithms. You're watching Chinese creators.

The meme transforms this economic reality into a kind of identity performance. It's a way of saying: yes, I know China manufactures most of my life. Yes, I know I'm dependent on Chinese supply chains. And you know what? That's kind of interesting.

Orientalism Reimagined: From Mockery To Aspiration

Culturally, what's happening with the "very Chinese time" meme is a fundamental inversion of Western Orientalism. For centuries, the relationship between Western culture and Eastern culture was defined by mockery, exoticization, and a sense of Western superiority. Eastern cultures were portrayed as backwards, primitive, exotic, or decadent.

Orientalism, as theorized by Edward Said, was a way of justifying Western dominance. By portraying the East as fundamentally other, inferior, and in need of Western guidance, Western countries could justify colonialism, imperialism, and global dominance.

But something shifted. As Western economies stagnated and Eastern economies boomed, the narrative flipped. Instead of the East being exotic and inferior, it started being modern and superior.

The "very Chinese time" meme represents what some culture critics call "aspirational Orientalism." Instead of mocking China, young Americans are expressing admiration for it. Instead of treating Chinese culture as strange and other, they're treating it as desirable and contemporary.

This is still a form of Orientalism in the technical sense. It's still an abstraction, a projection, a simplified representation. But instead of projecting inferiority, it's projecting excellence.

What makes this shift profound is that it's not coming from a position of power. Previous Orientalism was imposed by dominant cultures. This Orientalism is coming from a generation that doesn't feel particularly dominant. They feel anxious about their future, skeptical about their own country's institutions, and looking around for alternatives.

When Minh-Ha T. Pham, a cultural theorist, observed that "In the twilight of the American empire, our Orientalism is not a patronizing one, but an aspirational one," they were capturing something real. The emotional texture of this cultural moment is fundamentally different from past relationships between America and Asia.

It's important to note that this shift is still complicated by race, power, and representation. American fascination with Asian aesthetics, fashion, and culture has a long history of extraction, appropriation, and erasure. The "very Chinese time" meme, for all its goodwill, still treats China as an abstraction rather than a complex reality with billions of people living in it.

Some Chinese and Chinese diaspora creators have tried to complicate this narrative, pointing out that you can't just adopt "Chinese-ness" by buying a jacket or eating dim sum. That reduction of an entire civilization and culture to aesthetic and consumption choices is still a kind of erasure.

But the meme is also genuinely opening up conversations about what America wants to be, and what it thinks it's lost. The aspirational element is real. The admiration is sincere, even if it's based on incomplete information.

Estimated data shows perceived decline in key areas like infrastructure and democracy, reflecting a gap between expectations and reality.

What Real Chinese People Think: Not All Appreciation

Here's where the story gets complicated. Because while the meme is spreading through American internet culture, actual Chinese people and Chinese diaspora communities have mixed reactions.

Some creators and community members have embraced it. If Americans want to celebrate Chinese efficiency, Chinese design, Chinese technology, and Chinese culture, why not lean into it? Some Chinese diaspora creators have even weaponized the meme for cultural celebration, posting content that reclaims and redefines what "Chinese" means on their own terms.

But many others have expressed discomfort or skepticism. There are a few reasons for this.

First, there's the issue of reduction. The "very Chinese time" meme, at its core, treats Chinese culture as a set of surface-level aesthetics and behavioral traits. You become Chinese by buying a jacket, eating dim sum, or using an app. But actual Chinese identity is infinitely more complex. It's shaped by language, history, family relationships, philosophy, and lived experience.

When non-Chinese people claim to "become Chinese" through consumption, it can feel reductive. It can feel like Chinese culture is being treated as a costume that you can put on and take off, rather than as a lived identity.

Second, there's the historical context. For decades, Asian Americans have been told that their cultural practices are strange, foreign, other. They've been mocked for the food they eat, the language they speak, the way they dress. And suddenly, when it becomes trendy for white Americans to perform those same practices, it's celebrated as cool and interesting.

This feels like cultural appropriation with a fresh coat of paint. The practices aren't new. What's new is that white Americans are doing them.

Third, there's the question of who gets to profit. If the "very Chinese time" meme drives traffic to Chinese e-commerce platforms, Chinese creators, and Chinese businesses, that's genuinely valuable. But if it just drives engagement to American creators performing Chinese-ness, then it's just another way of extracting value from Asian culture.

Fourth, there's the broader context of American discourse about China. The meme exists in a culture where China is still often portrayed as a threat, as authoritarian, as un-American. The admiration expressed through the meme is shallow and ironic. It doesn't extend to actual solidarity with China or to critique of American foreign policy.

Some Chinese creators have tried to push back by pointing out the difference between appreciating aesthetic elements and actually understanding or respecting Chinese culture. One creator made a Tik Tok noting that you can't become Chinese by eating orange chicken for the first time. That reduction of an entire civilization to minimum-effort consumption is kind of the definition of stereotyping.

But the most productive critiques from Chinese communities have been constructive. Instead of dismissing the meme, they've used it as an opportunity to educate, to complicate, to push Western audiences toward deeper engagement with actual Chinese culture.

Some of this has worked. Interest in learning Mandarin has increased. Interest in Chinese literature, cinema, and art has grown. The meme opened a door, even if the door led to shallow places first.

The Technology Behind The Trend: How Algorithms Spread Memes

Understanding why the "very Chinese time" meme spread so fast and so far requires understanding how internet algorithms work and how memes travel through networks.

Memes aren't just jokes that spread through social sharing. They're strategic uses of cultural templates that tap into underlying tensions or anxieties. When a meme hits, it's because it's saying something that a lot of people already feel, but don't have language for.

The algorithm helps by amplifying content that gets engagement. The more people interact with a post (likes, shares, comments), the more the algorithm shows it to new people. This creates a feedback loop where popular content becomes more visible, which makes it more popular.

But algorithms don't just spread anything equally. They're trained on data about what keeps people engaged. And what keeps people engaged is content that triggers emotional responses: outrage, joy, identification, curiosity.

The "very Chinese time" meme triggers multiple emotional responses at once. There's the humor element, which makes it shareable. There's the element of identification (yes, I do use Chinese apps and buy Chinese products). There's the element of transgression (I'm joking about becoming another nationality, which used to be unacceptable). There's the element of commentary on contemporary life.

Tik Tok, where the meme primarily spread, has a particularly powerful algorithm. Unlike Instagram or Twitter, Tik Tok doesn't prioritize your existing network. It shows you content from creators you don't follow, based purely on predicted engagement. This means that a creator with a few thousand followers can suddenly have their content shown to millions, if the algorithm thinks people will engage with it.

This is how trends spread on Tik Tok faster than on other platforms. The algorithm is specifically designed to surface novel, engaging content, not just content from people you already follow.

The meme also benefited from participation by larger creators and celebrities. When Jimmy O Yang or Hasan Piker posted their own version, they brought their larger audiences into the trend. This created a multiplier effect.

But none of this happens without the underlying cultural readiness. The algorithm can promote content, but it can't make you care about something that doesn't resonate. The "very Chinese time" meme spread because it was saying something true about American culture in 2025.

The Democratic Collapse Angle: Why America Seems Broken

One element that can't be overlooked in understanding the "very Chinese time" meme is the specific moment it arrived in American politics and culture.

The meme gained serious traction in late 2024 and early 2025, a period that was marked by significant political turbulence in America. Long-standing democratic norms were being challenged. There was a sense, particularly among younger people, that the institutions they'd been taught to trust were failing or corrupt.

At the same time, basic quality of life issues were becoming harder to ignore. Housing is unaffordable. Healthcare is broken. The job market is precarious. Infrastructure is crumbling. Public transit is inadequate. Schools are underfunded. The criminal justice system is dystopian.

When you're living through this reality, and you're looking at images of Chinese cities that work, Chinese infrastructure that functions, Chinese governments that can implement large-scale projects, the contrast is painful.

It's not that Americans suddenly became pro-authoritarian. It's that they're saying, implicitly: our system isn't delivering on its promises, and another system is.

The meme gives voice to this without requiring people to make an explicit political statement. You can joke about becoming Chinese without endorsing Chinese government policies. You can admire Chinese technology without endorsing Chinese surveillance. You can comment on infrastructure without becoming a pro-authoritarian.

But underneath, there's real doubt about whether American democracy is functioning well. Whether American capitalism is delivering value. Whether American institutions are legitimate.

This is part of a broader trend in how younger Americans view their country. There's skepticism about American exceptionalism. There's interest in alternative models. There's a sense that the American Dream, as it's been sold, isn't real.

The "very Chinese time" meme is downstream of this larger generational shift in belief. It's a small joke, but it's reflecting a massive change in how people think about their country and other countries.

The 'Very Chinese Time' meme saw a significant rise in popularity from 2024 to mid-2025, reflecting cultural shifts and humor trends. Estimated data.

Celebrity Participation: When The Joke Goes Mainstream

Memes usually stay on Tik Tok. They're created by teenagers and young adults, shared in community with others who get the reference, and sometimes they break out into broader culture. But most don't. Most exist in their native ecosystem and that's fine.

The "very Chinese time" meme broke out because of celebrity participation. When established comedians like Jimmy O Yang made their own version, it signaled that the meme was acceptable, interesting, and worth paying attention to. When streamers like Hasan Piker got involved, it brought their audiences in.

Celebrity participation has both positive and negative effects. On one hand, it gives a meme legitimacy and spreads it further. On the other hand, it can also kill a meme by making it too mainstream, too safe, too unfunny.

With the "very Chinese time" meme, celebrity involvement seems to have accelerated spread without quite killing it yet. The meme is now big enough that brands are trying to get involved. Companies are posting their own versions. It's in that transitional moment where it could either become a genuine cultural artifact or dissolve into corporate co-optation.

But what's notable about celebrity involvement is that it gives voice to people who might not otherwise have platform to express these ideas. Jimmy O Yang, for instance, is a Chinese American comedian. His participation in the meme adds layer of commentary. He's not just joking about becoming Chinese; he's joking about how non-Chinese people can adopt Chineseness while actual Chinese Americans navigate the reality of being Asian in America.

This kind of double-layered commentary is what keeps memes alive and relevant. It's not just the original joke anymore; it's what happens when different people with different positions engage with it.

The Commerce Question: Who Profits From The Trend?

Memes always have economic implications. When millions of people are talking about something, money follows.

The "very Chinese time" meme directly drives commerce. When people joke about Chinamaxxing and buying Chinese products, some of them actually do it. Shein, DHGate, and Ali Express probably saw traffic increases related to the meme. Chinese creators on Tik Tok probably saw follower increases. Interest in learning Mandarin probably spiked.

But most of the profit flows upward. The platforms that host the content (Tik Tok, Instagram, You Tube) profit from engagement. The Chinese companies selling products (Shein, DHGate) profit from sales. Chinese creators with large audiences profit from sponsorships and brand deals.

The average person making the meme, posting the meme, engaging with the meme, doesn't profit. They're creating content that drives value for platforms and companies, and receiving nothing in return except the social currency of being in on the joke.

This is the basic structure of social media value extraction. Users create content, platforms profit from that content by selling advertising and data. It's the same whether you're making a meme or uploading a selfie.

But there's a specific angle with the "very Chinese time" meme, which is that it's driving money and attention to Chinese companies and creators. In the context of US-China relations, this is geopolitically interesting.

Some commentators have suggested that the meme is evidence of a cultural shift toward China, which could have implications for long-term American attitudes toward Chinese businesses, Chinese investment, and Chinese technology.

Others have suggested that the meme is actually just Tik Tok being really good at its job: showing people content they'll engage with, regardless of national origin. The fact that a lot of the content turns out to be from Chinese creators or about Chinese products is just what happens when you optimize for engagement without regard to national interest.

What's clear is that the meme is moving real money and real attention toward Chinese commerce and creators, which is a shift from the previous state of affairs.

The Tariff Moment: When Politics Made China Visible

One specific catalyst for the "very Chinese time" meme was the tariff discourse.

When the Trump administration proposed or implemented tariffs on Chinese goods, it forced Americans to confront supply chain realities. Suddenly, news coverage was talking about where consumer goods came from, how tariffs work, and what the actual cost would be for Americans.

Tariff coverage made visible something that was previously abstracted: your stuff comes from China, and politicians making trade decisions is going to affect how much you pay for it.

This made China visible in a new way. It wasn't a distant geopolitical actor anymore. It was a direct factor in how much your clothes cost, how much your phone costs, how much your cheap plastic stuff costs.

The tariff discourse also exposed a kind of hypocrisy in American political rhetoric. For years, politicians warned about China while American companies outsourced manufacturing to China. American consumers bought Chinese products while Americans politicians talked about decoupling from China.

The meme, in a way, was a response to this contradiction. You can't actually decouple from China, because your entire life is entangled with it. The only logical response is to acknowledge that entanglement ironically, through humor.

Tariffs also made clear that China was winning the economic competition. If you try to put up barriers against Chinese goods, prices go up for American consumers. If you try to restrict Chinese technology, American companies lose market share. The US wants to decouple from China, but the economic reality makes that increasingly difficult.

The meme is a way of saying: yes, we see what's happening. Yes, we're dependent on China. Yes, maybe that's okay.

Chinese brands like Xiaomi, OnePlus, and DJI have become highly competitive globally, scoring high in quality and features. Estimated data.

The Decline Narrative: What The Meme Actually Expresses

At its heart, the "very Chinese time" meme is an expression of perceived American decline.

Not actual decline, necessarily. America is still the world's largest economy, still has the most advanced military, still leads in many areas of innovation. But relative decline. Decline relative to expectations. Decline relative to how things used to work. Decline relative to other countries.

For generations, Americans were told that their country was exceptional, that it was the best in the world, that American democracy worked, that American capitalism delivered, that American innovation was unmatched.

A generation of Americans grew up believing this. And then they became adults and realized that it wasn't true in the way they'd been told.

Their country's infrastructure is worse than countries that are supposedly less advanced. Their democracy is increasingly dysfunctional. Their capitalism has generated massive inequality. Their innovation is concentrated in a few cities and a few industries.

Meanwhile, other countries are building better transit systems, building better cities, building better technology. Countries that aren't supposed to be as advanced as America are apparently more advanced in key ways.

This is disorienting. It's depressing. It's also confusing, because nobody really talks about it directly in mainstream discourse. Politicians still talk as if America is exceptional. Media still acts like American culture is globally dominant. Institutions still operate as if the American system is the model to follow.

But people feel the gap between the rhetoric and the reality. And the meme gives them a way to express that gap. By joking about becoming Chinese, they're saying: something is wrong here. Another system appears to be working better. What happened to us?

This is why the meme resonates so strongly with younger people specifically. Gen Z has never known a time when American dominance was unquestioned. They've grown up during American wars that didn't achieve objectives, during financial crises caused by American institutions, during periods when American political dysfunction was obvious and ongoing.

They're not operating from a place of nostalgia for American greatness. They're operating from a place of skepticism about whether American greatness ever really existed in the form they were told.

The meme, from this angle, is almost a grief response. It's processing loss. The loss of faith in American institutions, the loss of belief in American exceptionalism, the loss of a simple narrative about the world.

The Future Of The Meme: Will It Last?

Most memes don't have long shelf lives. They're consumable, disposable, funny for a moment and then exhausted. The "very Chinese time" meme might follow that pattern.

But some memes persist because they're tapping into something structural rather than something trendy. The question is whether the underlying anxieties that the meme expresses are temporary cultural blips or permanent features of American culture in 2025.

If the anxieties are temporary, the meme will fade. If they're structural, the meme will evolve, but the impulse behind it will persist.

We're betting on the structural interpretation. The reasons people are drawn to the meme aren't going away anytime soon. American infrastructure isn't magically becoming better. American politics isn't becoming less dysfunctional. Chinese technology isn't becoming less competitive. The economic entanglement with China isn't unwinding.

What will probably happen is that the specific format of the meme will fade, but the underlying impulse will express itself in different ways. Different meme formats. Different conversations. Different behavioral shifts.

You can already see evolution happening. "Chinamaxxing" is becoming a more specific term. Interest in Chinese products is becoming normalized rather than ironic. Some people are actually learning Mandarin, moving to China, or building businesses around the China-US connection.

The meme might have started as a joke, but it's opening real doors. Real people are engaging more seriously with China, Chinese culture, and Chinese products than they were before.

This suggests that the meme was a symptom of something happening anyway, just a cultural articulation of shifts that were already in motion. The meme didn't cause the shift; it just made the shift legible.

Five years from now, the "very Chinese time" meme probably won't be a thing. But the attitudes it expressed will have become mainstream and normal.

The Broader Cultural Shift: Beyond The Meme

The "very Chinese time" meme is just the most visible expression of a broader reorientation of American culture toward China.

This is happening in multiple domains simultaneously. In technology, American venture capitalists and entrepreneurs are increasingly interested in Chinese technology companies and Chinese business models. In fashion, Chinese designers are getting international attention. In entertainment, Chinese films and shows are finding audiences in America. In education, interest in Chinese language and culture is growing.

This isn't driven by government policy or corporate strategy. It's grassroots. It's young people making their own choices about what they consume, what they value, and what they aspire to.

The meme is just the cultural artifact that makes this shift visible. It's the moment when the underlying trends break through into mainstream awareness.

What's important is recognizing that this isn't just a trend that will reverse. The structural factors that are driving this shift are real and durable. Chinese manufacturing dominance, Chinese technological innovation, Chinese platforms and apps, and Chinese cultural production are all real things that aren't going away.

America could try to resist this through policy (tariffs, export controls, investment restrictions). But the resistance seems increasingly futile. The entanglement is too deep. The economic logic is too strong. The cultural appeal is too genuine.

What we're probably looking at is a long-term reorientation of how Americans view the world and their place in it. The "very Chinese time" meme is just one early articulation of that shift. Many more will follow.

Authenticity, Appropriation, And Intent: The Ethical Questions

There are real ethical questions embedded in the "very Chinese time" meme that deserve serious consideration, even as the meme itself is being treated humorously.

The primary question is: when non-Chinese people adopt Chinese aesthetic, language, or cultural practices, is that appropriation or appreciation?

The answer is complex and depends on context. If you're a non-Chinese person learning Mandarin, studying Chinese history, engaging with Chinese art and literature, and treating Chinese culture with genuine respect and effort, that's appreciation. You're investing time and energy into understanding something outside your own background.

If you're doing it superficially, treating it as a costume or a phase, extracting value while contributing nothing, that's appropriation. You're treating someone else's culture as raw material for your own entertainment.

The "very Chinese time" meme exists in the gray zone. Some participation is clearly appreciation. Some people who engage with the meme are genuinely interested in Chinese culture and are using the meme as an entry point. Others are doing it superficially, as a joke, with no real interest in anything beyond the humor.

What matters ethically is whether the participation includes respect and whether it contributes to actual cultural exchange versus extraction.

One important principle: if you're going to engage with someone else's culture, know something about it. Don't reduce an entire civilization to stereotypes or surface-level consumption. Learn the language, learn the history, learn the contemporary reality. Understand that China has a billion people with a complex, diverse, sophisticated culture that can't be captured in a meme or a trendy jacket.

This is where Chinese diaspora creators have been doing important work. By participating in the meme while also educating, they're modeling what respectful engagement looks like. You can have fun with cultural exchange while also pushing toward deeper understanding.

FAQ

What does "very Chinese time of my life" actually mean?

The phrase is a reference to Tyler Durden's opening monologue in the movie "Fight Club," where he describes a moment of moral crisis or lifestyle transformation. In the meme, people use it to describe a phase of their life when they're consuming primarily Chinese products, using Chinese apps, or adopting perceived Chinese aesthetic and lifestyle choices. It's meant to be humorous and ironic, expressing both admiration for and detachment from the trend.

Why did the meme become so popular in 2024-2025?

The meme resonates because it reflects real changes in American life. A generation of Americans has grown up dependent on Chinese technology, Chinese manufacturing, and Chinese apps. At the same time, they've become skeptical about American institutions and infrastructure. The meme gives them a way to express this reality through humor. It combines genuine admiration for aspects of Chinese technology and efficiency with ironic distance that makes the expression socially acceptable.

Is the meme actually about China or about America?

It's primarily about America. The meme uses China as a mirror to reflect back what Americans perceive they've lost: functional infrastructure, efficient government, technological innovation, and economic dynamism. China in the meme is more abstraction than reality. It's a symbol of what Americans feel their country used to be and what they worry it's becoming. Real Chinese people are diverse and complex, but the meme flattens China into a simplified symbol.

What do Chinese people actually think about the meme?

Reactions are mixed. Some Chinese and Chinese diaspora creators have embraced it as an opportunity to showcase Chinese culture and accomplishments. Others view it as reductive and performative, treating a complex civilization as a trendy aesthetic. Many are skeptical of whether the admiration expressed through the meme translates into genuine respect or understanding of Chinese culture. There's also concern that the meme reduces Chinese identity to stereotypes and consumption choices, which is itself a form of Orientalism.

Does participating in the meme count as cultural appropriation?

It depends on your intent and engagement level. Genuine interest in Chinese products, language, history, and contemporary culture crosses into appreciation. Treating Chinese culture as a trendy costume or surface-level aesthetic while dismissing deeper engagement is closer to appropriation. The ethical line is usually: are you engaging respectfully and learning something, or are you extracting value for entertainment without contributing anything back?

How has technology made China more accessible to Americans?

AI translation tools have made language barriers nearly invisible. You can now engage with Chinese content, Chinese creators, and Chinese commerce without understanding Mandarin. Apps like Tik Tok have given Chinese creators direct access to American audiences. Platforms like DHGate and Ali Express allow direct purchasing from Chinese manufacturers. Together, these changes mean that Americans are engaging with Chinese culture, technology, and commerce in unprecedented ways, often without consciously seeking it out.

Is the meme a sign that America is in decline?

The meme reflects generational perception of relative American decline. Whether actual decline is happening is a complex economic and political question. What's clear is that Americans are reassessing their country's position in the world. Chinese infrastructure, technology, and economic growth appear impressive by comparison to American equivalents. This comparison, whether entirely fair or not, is shaping how younger Americans view their future and their country's place in the world.

What happens to the meme next?

The specific "very Chinese time" format will probably fade, as most memes do. But the underlying impulse it expresses will likely persist and evolve. You'll see it expressed in new meme formats, in changed consumer behavior, in political discourse, and in how younger Americans relate to China and Chinese culture. The meme might be temporary, but the cultural shift it represents is probably more durable.

Why are Gen Z Americans interested in Chinese products and culture?

Multiple factors converge: Chinese technology is genuinely competitive and sometimes superior. Chinese manufacturing is efficient and affordable. Chinese apps like Tik Tok are well-designed. But there's also a generational element. Gen Z is less invested in American exceptionalism and more willing to engage seriously with alternatives. They've grown up in a multipolar world where America doesn't automatically dominate. They're evaluating based on actual product quality and function rather than national branding.

What's the difference between Chinamaxxing and just buying Chinese products?

"Chinamaxxing" implies intentionality and systematic effort. It's not just buying Chinese products because they're available; it's actively choosing Chinese alternatives, prioritizing efficiency and function over American brand loyalty, and potentially engaging more deeply with Chinese culture and values. It suggests a wholesale adoption of a "Chinese" lifestyle optimization approach, at least partly ironically and partly genuinely.

Conclusion: A Meme Reflects A Changing World

The "very Chinese time of my life" meme started as a joke. It still is a joke. But like many memes, it's doing real cultural work underneath the humor.

It's expressing something that people feel but can't always articulate directly: that the world has shifted. That American superiority is no longer automatic. That other countries have figured out how to build functional infrastructure, efficient governance, and innovative technology. That the American Dream, as it's been sold, isn't matching the lived reality of younger Americans.

The meme gives people a way to express these anxieties while maintaining ironic distance. You can joke about becoming Chinese without renouncing your citizenship. You can admire Chinese technology while remaining skeptical of Chinese politics. You can consume Chinese products while maintaining that you're really still American. It's a way of processing transformation that feels too big to name directly.

But underneath the irony, real things are happening. Americans are buying more Chinese products. They're using more Chinese apps. They're engaging with Chinese creators and Chinese culture. They're learning Mandarin. They're traveling to China. They're reassessing what they value and where they think innovation is happening.

The meme didn't cause this shift. But it made the shift visible. It articulated something that a lot of people already felt. It created a shared vocabulary for talking about a profound reorientation in American culture.

In five years, the specific meme will be dead. But the attitudes it expressed will be normal. The reassessment of America's place in the world will have moved further along. The entanglement with Chinese technology and manufacturing will be even deeper. The interest in Chinese culture will have become mainstream rather than ironic.

What started as a joke about becoming Chinese is actually a window into how Americans are coming to terms with not being the undisputed center of the world anymore. It's adaptation. It's realism. It's the sound of a generation growing up and adjusting to a different reality than the one they were promised.

The meme is funny because it's true. And it will probably keep being true for a while.

Key Takeaways

- The meme uses humor to process genuine shifts in American-Chinese economic and cultural relations

- It reflects real dependency on Chinese manufacturing, apps, and technology in daily American life

- The phrase inverts traditional Orientalism, expressing aspiration toward China rather than mockery

- Translation technology and direct commerce platforms have made Chinese culture and products more accessible than ever

- The trend represents generational skepticism about American institutions and exceptionalism

- Real Chinese people have mixed reactions, from appreciation to concerns about cultural reduction

- The specific meme format will fade, but the underlying cultural shift is likely durable and ongoing

![Very Chinese Time: Why The Meme Went Viral [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/very-chinese-time-why-the-meme-went-viral-2025/image-1-1768574778182.jpg)