The End of an Era: Continuous Upskilling is Now Non-Negotiable

Remember when you could learn a skill at 22 and coast on it until retirement? Those days are gone.

At CES 2026, something remarkable happened during a live taping of the All-In podcast. Three of the most influential voices in technology and business gathered to discuss a seismic shift happening right now: the complete dissolution of the "learn once, work forever" model that shaped careers for generations.

Bob Sternfels, the Global Managing Partner of McKinsey & Company, sat alongside General Catalyst's CEO Hemant Taneja. What they discussed wasn't theoretical. It was urgent, grounded in data, and profoundly unsettling for anyone who assumed their career trajectory would follow the playbook of previous generations.

The consensus was stark: artificial intelligence is reshaping work faster than any technology before it. Not by years or decades, but by months. The implications ripple through everything—from which jobs will exist in five years to how companies structure their workforce to what skills genuinely matter anymore.

Let me cut to the chase: if you're still thinking about career development the way you did in 2023, you're already behind.

The Explosive Growth of AI: Numbers That Defy Precedent

When venture capitalists and management consultants use phrases like "the world has completely changed," it usually means one of two things: either they're overselling a marginal shift, or something genuinely unprecedented is happening.

In this case, it's the latter.

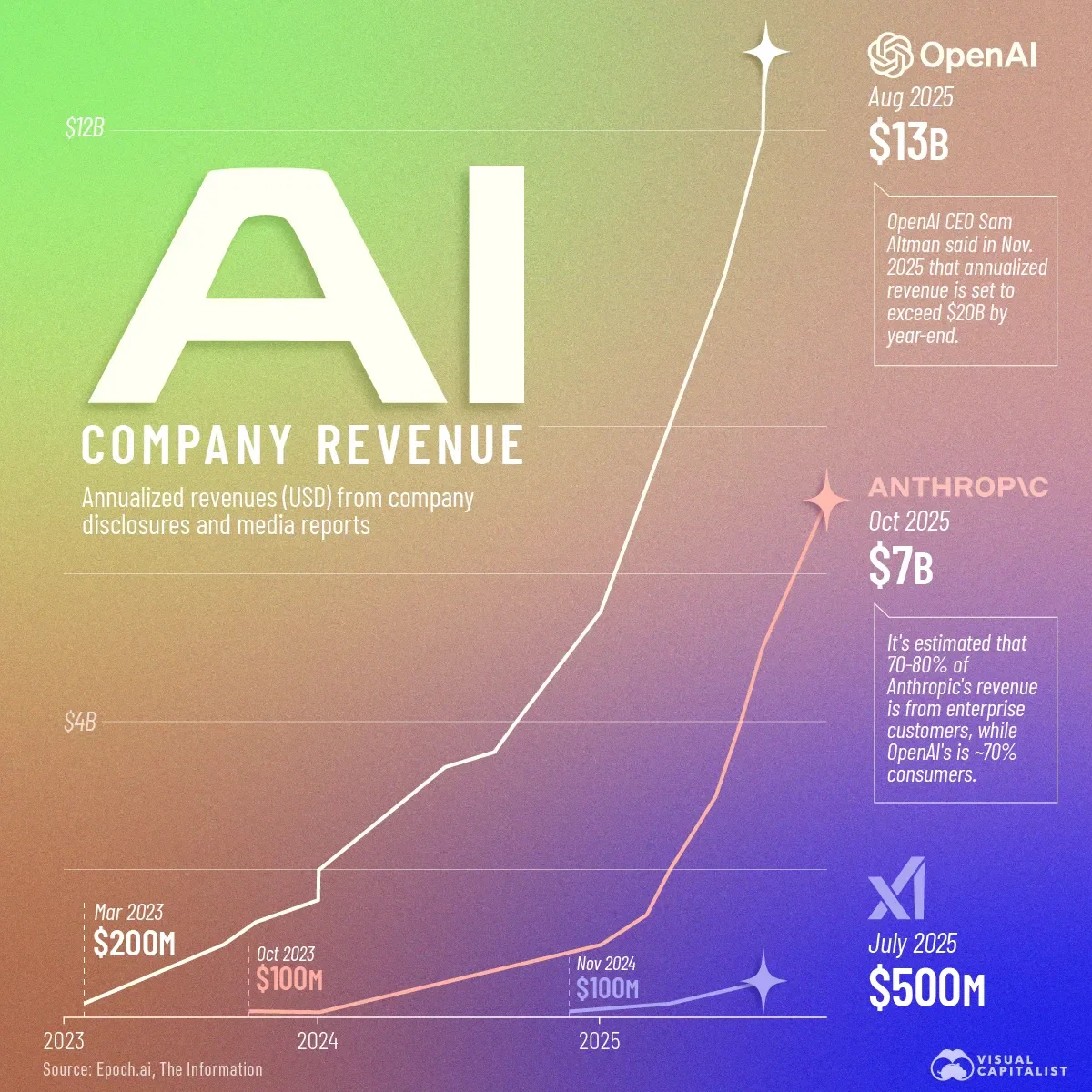

Taneja pointed to a metric that crystallizes the scale of what's happening: valuation velocity. Stripe took 12 years to reach a

That's not a typo. That's not hype.

Taneja believes we're witnessing the emergence of a new wave of trillion-dollar companies. "That's not a pie-in-the-sky idea with Anthropic, OpenAI, and a couple of others," he said. The data backs this up. The AI market that barely existed three years ago is now a central driver of the largest companies on Earth.

But here's what most people miss: the growth isn't just about the AI companies themselves. It's about the velocity at which they're deploying capabilities that didn't exist six months prior. Claude becomes multimodal. Chat GPT gains real-time browsing. New models train faster, with less data, achieving better results. Each iteration creates cascading effects through the economy.

Calacanis pressed them on what's actually driving this explosion. The answer matters because it reveals something uncomfortable: most companies haven't even begun to feel the full impact.

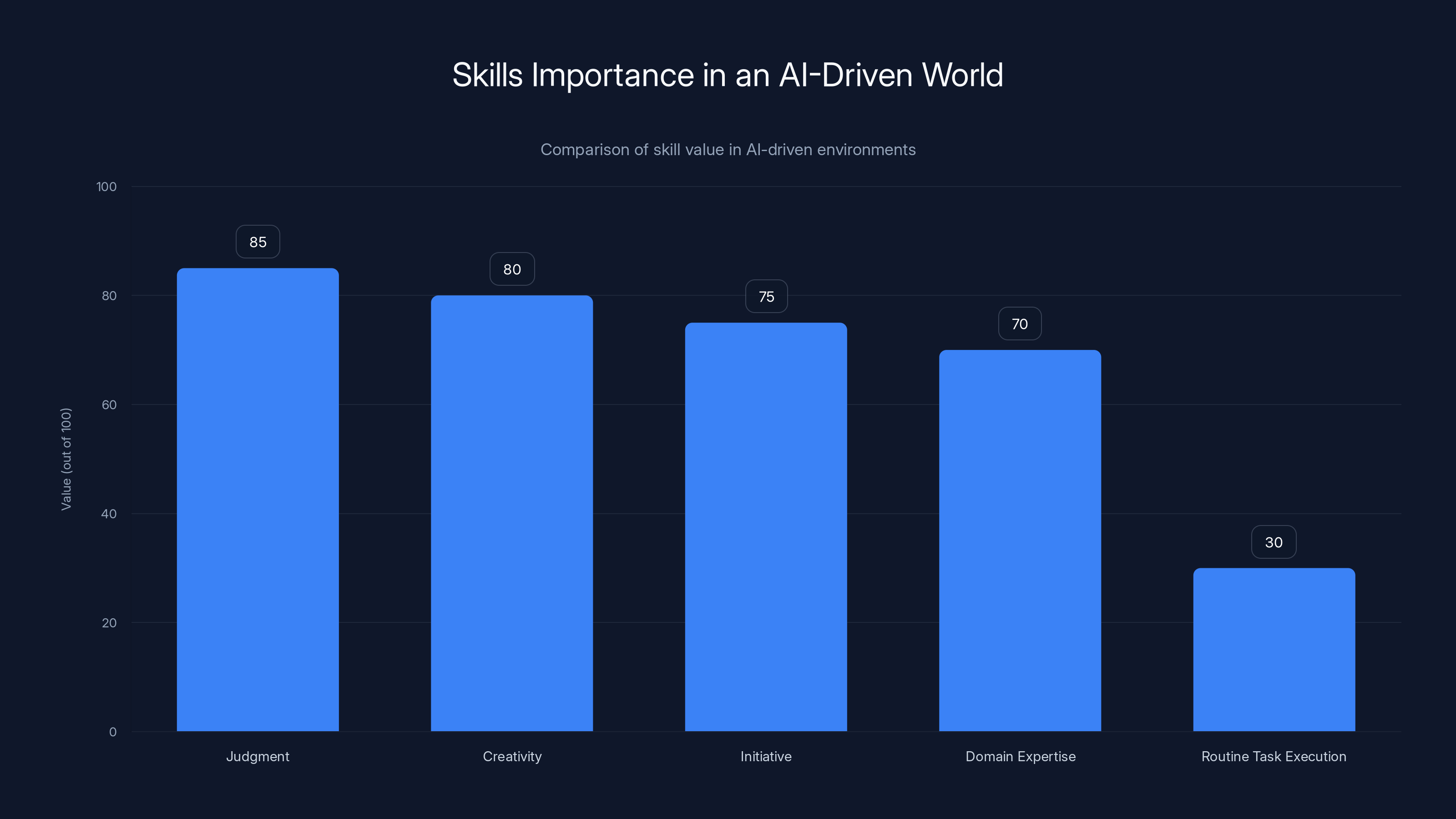

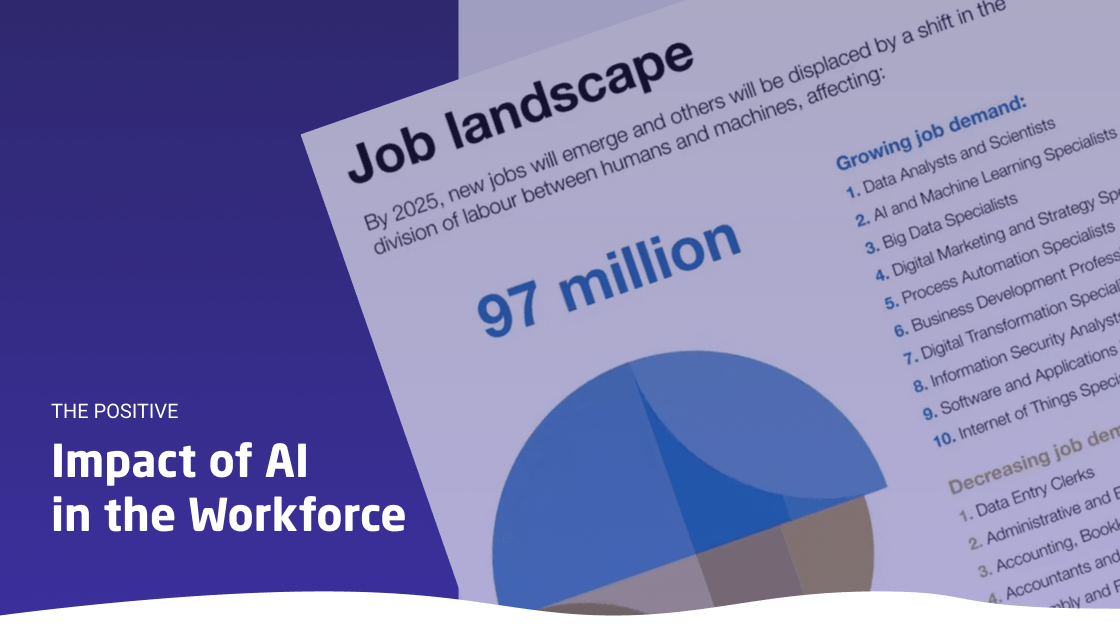

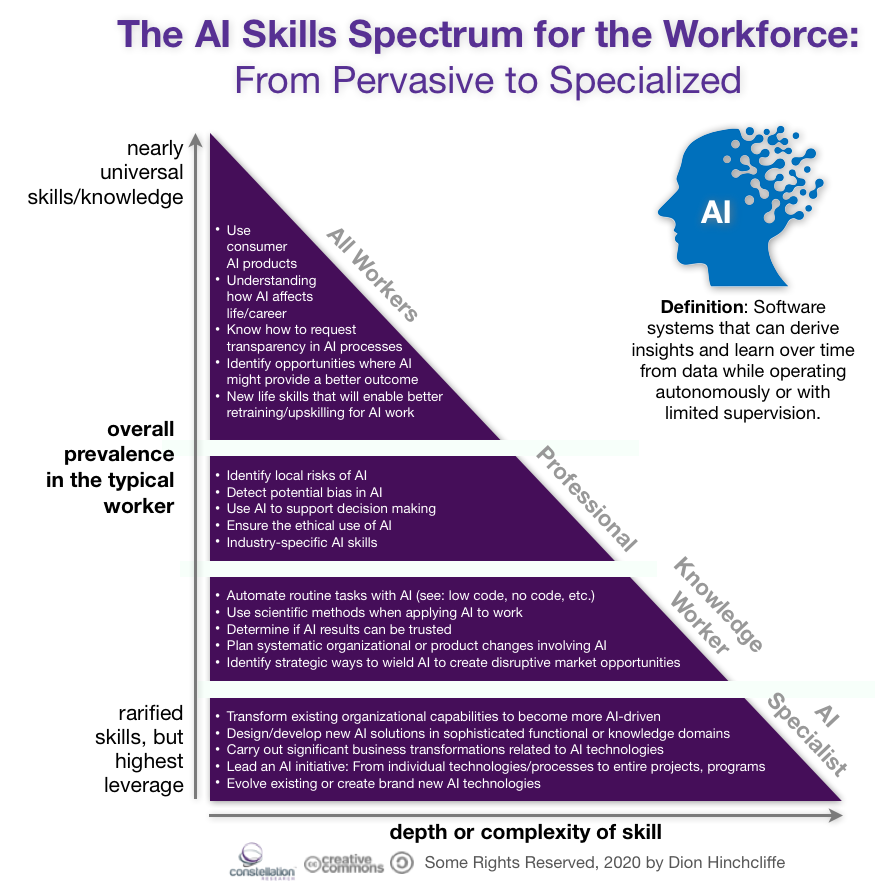

In an AI-driven world, skills like judgment, creativity, initiative, and domain expertise are valued significantly higher than routine task execution, which AI can handle efficiently. Estimated data.

The Adoption Paradox: Why Most Companies Are Still Testing

Here's a contradiction that cuts to the heart of why AI disruption feels both inevitable and stalled at the same time.

Sternfels acknowledged something that most tech media glosses over: while many companies are running AI pilots and proof-of-concepts, actual enterprise adoption remains surprisingly cautious. Yes, you're reading AI headlines daily. Yes, every CEO talks about AI strategy. But when you dig into what's actually deployed in production across non-tech industries, the picture is far less dramatic.

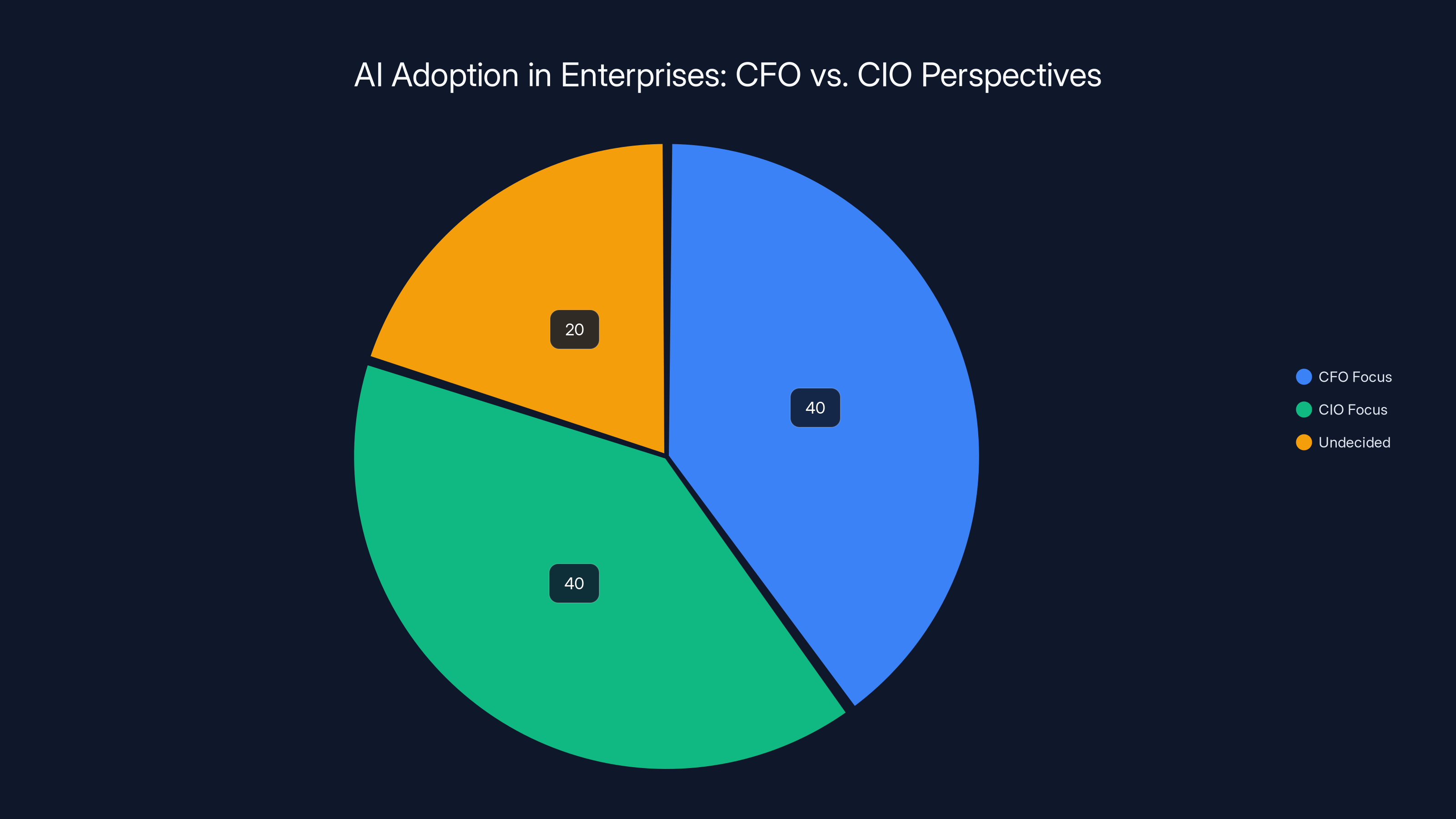

Why? Because there's a civil war happening in the C-suite.

Sternfels revealed the question that McKinsey consultants hear constantly from CEOs: "Do I listen to my CFO or my CIO right now?" This seemingly simple question actually captures the entire organizational tension around AI.

The CFO looks at the spreadsheet. Implementation costs. Training budgets. Infrastructure investments. Headcount changes. And most critically: return on investment. For many companies, the financial case for rapid AI adoption remains murky. Projects take longer than expected. The promised productivity gains haven't materialized in quarterly earnings. The CFO says: "Wait. Let's see where this settles."

Meanwhile, the CIO is looking at the competitive landscape. They're seeing what AI-enabled competitors are doing. They're reading the same tech news you are. The CIO says: "We'll be disrupted. We have to move now. This is existential."

Both are right. That's what makes this moment so disorienting.

Sternfels framed it plainly: "Some people are looking at AI and they're scared." But fear isn't actually the core problem. The real issue is uncertainty. When the potential upside is enormous but the timeline and execution path are unclear, rational leaders pause. They run more pilots. They hire consultants (yes, this benefits McKinsey). They wait for more market signals.

But here's the trap: waiting has a cost too. Every quarter of delay means competitors who moved faster gain more data, more user feedback, more competitive advantage. The paradox is that the safest move (waiting) might actually be the riskiest one.

This tension will resolve itself, but not uniformly. Some industries will see rapid adoption; others will lag. The divergence in adoption speed will actually become a source of competitive advantage or disadvantage, depending on which side of the decision you fall.

Anthropic and OpenAI have shown unprecedented valuation growth, reaching over $100 billion within a few years. Estimated data reflects rapid acceleration in AI company valuations.

The Real Threat: Entry-Level Jobs and the Early Career Squeeze

Calacanis brought up the question that keeps emerging in every conversation about AI and work: what happens to entry-level positions?

This isn't abstract hand-wringing. It's about real career paths for millions of people. Historically, young people fresh out of college took entry-level roles—data analyst positions, junior developer jobs, customer service roles, administrative support. These roles were the first rung on the career ladder. You learned the fundamentals, built a network, moved up.

Now imagine an AI system that can do 60% of what a junior analyst does, immediately, at near-zero marginal cost. Not perfectly, but competently. Suddenly, the economics of hiring that entry-level employee look very different.

This is where the conversation gets uncomfortable. Sternfels and Taneja didn't shy away from it. If AI can handle routine analytical tasks, scheduling, research compilation, and initial drafting, then what's the job of the entry-level employee? Are they there to supplement the AI? To QA its outputs? To handle edge cases?

The risk isn't that jobs disappear entirely. It's that the entry-level becomes compressed. Companies that previously hired 10 junior analysts and 3 senior analysts might now hire 2 junior analysts and 3 senior analysts, with AI handling the volume that used to train the juniors.

For anyone entering the workforce in 2025 and beyond, this changes the playbook entirely.

What Skills Actually Survive: Judgment, Creativity, and Chutzpah

When Sternfels was asked what skills will remain essential, his answer was surprisingly human.

AI models can handle tasks. They can parse data, write code, generate text, analyze images, identify patterns. But "sound judgment and creativity remain the essential skills humans must bring to succeed." Notice he didn't say they become more valuable. He said they remain essential. Meaning they were always essential, but now they're the only thing left.

This is a crucial distinction. AI doesn't create demand for judgment and creativity. It eliminates demand for everything else. The middle skill set—competent but not exceptional execution of routine tasks—becomes obsolete. You're either working with AI (which requires judgment about when to trust it, what to fix, how to shape its output) or you're in a role where judgment is the entire job.

There's no middle ground anymore.

Calacanis built on this with a different angle: "To stand out, you're going to have to show chutzpah, drive, passion." That's not corporate speak. That's identifying something that's genuinely hard to automate: the ability to take initiative, to do things without being asked, to push against status quo, to have conviction even when it's unpopular.

An AI can generate a proposal. It can't decide that the proposal's premise is wrong and needs to be rethought from scratch. An AI can write code that passes tests. It can't decide that the entire architecture needs to be rebuilt. An AI can draft a report. It can't look at the data and say, "Wait, we're asking the wrong question."

That's the work that survives.

But here's the challenge: judgment is hard to teach. It comes from experience, pattern recognition, and mistakes. You can't cram it into a training program. And if entry-level roles are compressed, where does that experience-building happen?

That's not a question with a comfortable answer.

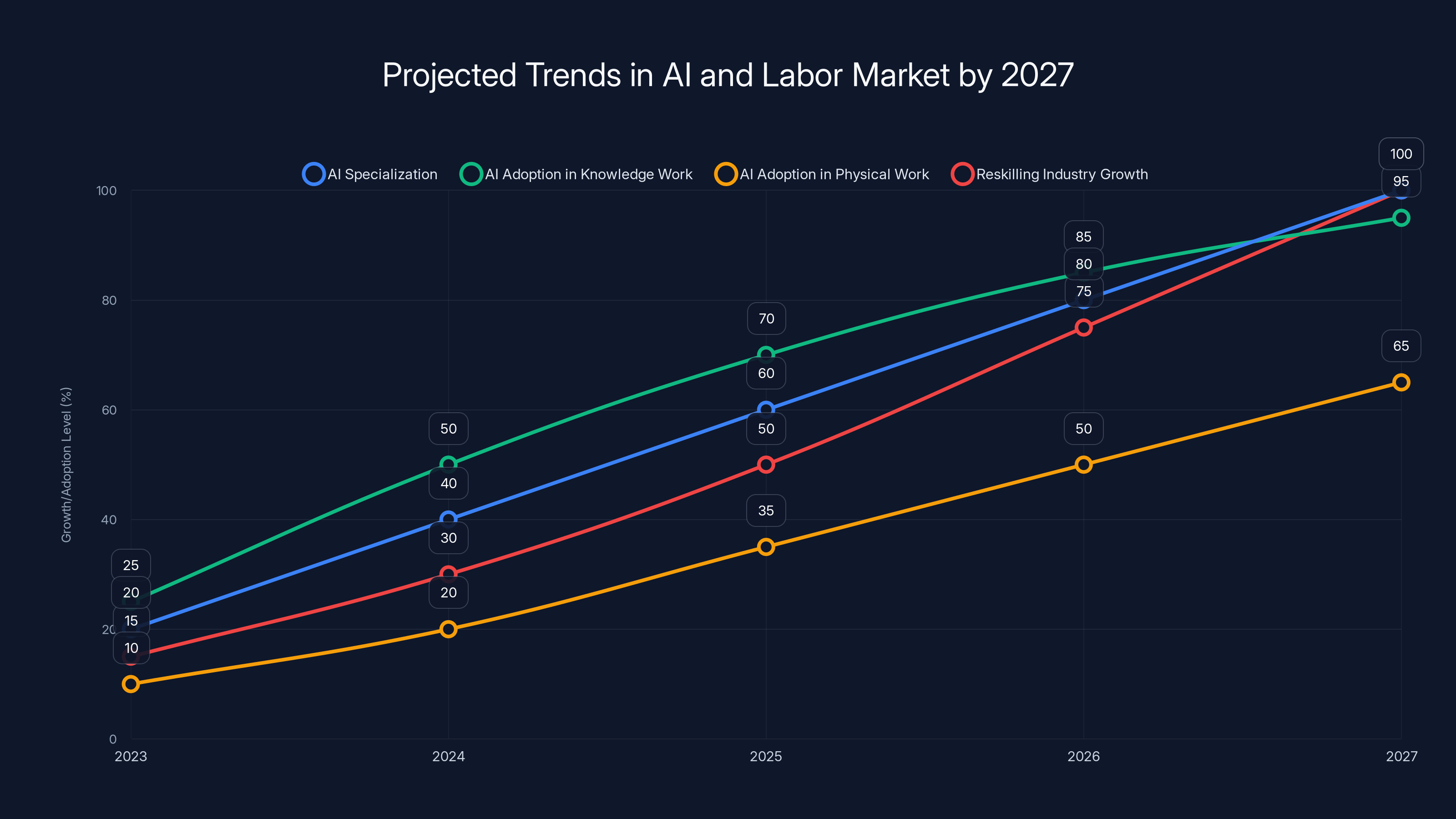

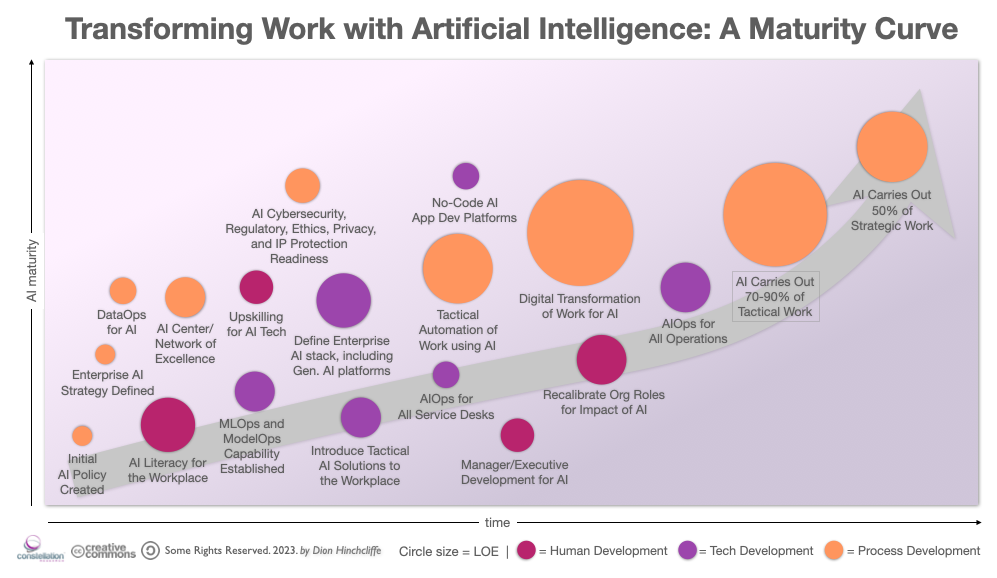

By 2027, AI specialization and adoption in knowledge work are expected to reach near full potential, while the reskilling industry will see significant growth. Estimated data.

The Lifelong Learning Imperative: Skilling and Reskilling as Career Constants

Taneja dropped a phrase that should be printed on every resume, LinkedIn profile, and career development plan: "Skilling and re-skilling will be a lifelong endeavor."

Then he made the fundamental claim: "This idea that we spend 22 years learning and then 40 years working is broken."

Broken. Not outdated. Not less efficient. Broken.

Think about what that means. The entire education system—primary through college through early career—was built on a model where the heavy lifting of learning happens at the front end. You absorb knowledge for two decades, then you deploy that knowledge for four decades. School is the investment phase. Work is the return phase.

That model assumed change was gradual. Skills had longevity. A civil engineer in 1990 could apply most of what they learned in 1970. Methods improved, tools updated, but the fundamentals were stable. That engineer could reasonably expect to work in the field for 35 years and only need incremental updates.

Now consider a software engineer in 2025. The tech stack they learn in their first job might be obsolete in three years. The best practices they implement in 2026 might be replaced by AI-native paradigms in 2027. The architectural patterns that feel solid could be disrupted by a new model released next quarter.

The velocity of change has fundamentally altered the math. If you need to reskill every 3-5 years, and a career spans 40+ years, then you're looking at 8-13 complete reskilling cycles in a single career. That's not an annual training program. That's a different relationship to learning.

Sternfels provided a concrete example of how this plays out at scale. McKinsey expects to have as many "personalized" AI agents as employees by the end of 2026. Let that sink in. Not a few AI tools. Not a company-wide AI system. As many AI agents as humans. Personalized to each person's role, responsibilities, and decision-making patterns.

What does that mean for a McKinsey consultant? It means the nature of the job changes fundamentally. You're not doing the analytical legwork that used to define consulting. That's what your AI agent is doing. You're instead responsible for asking better questions, synthesizing across domains, making judgment calls about which insights matter, and building relationships with clients.

That's a different job. Which means you need different skills. Which means you're reskilling.

Imagine that dynamic across millions of knowledge workers across every industry. That's what "lifelong learning" actually means in this context. Not occasional professional development. Continuous evolution of your core skills.

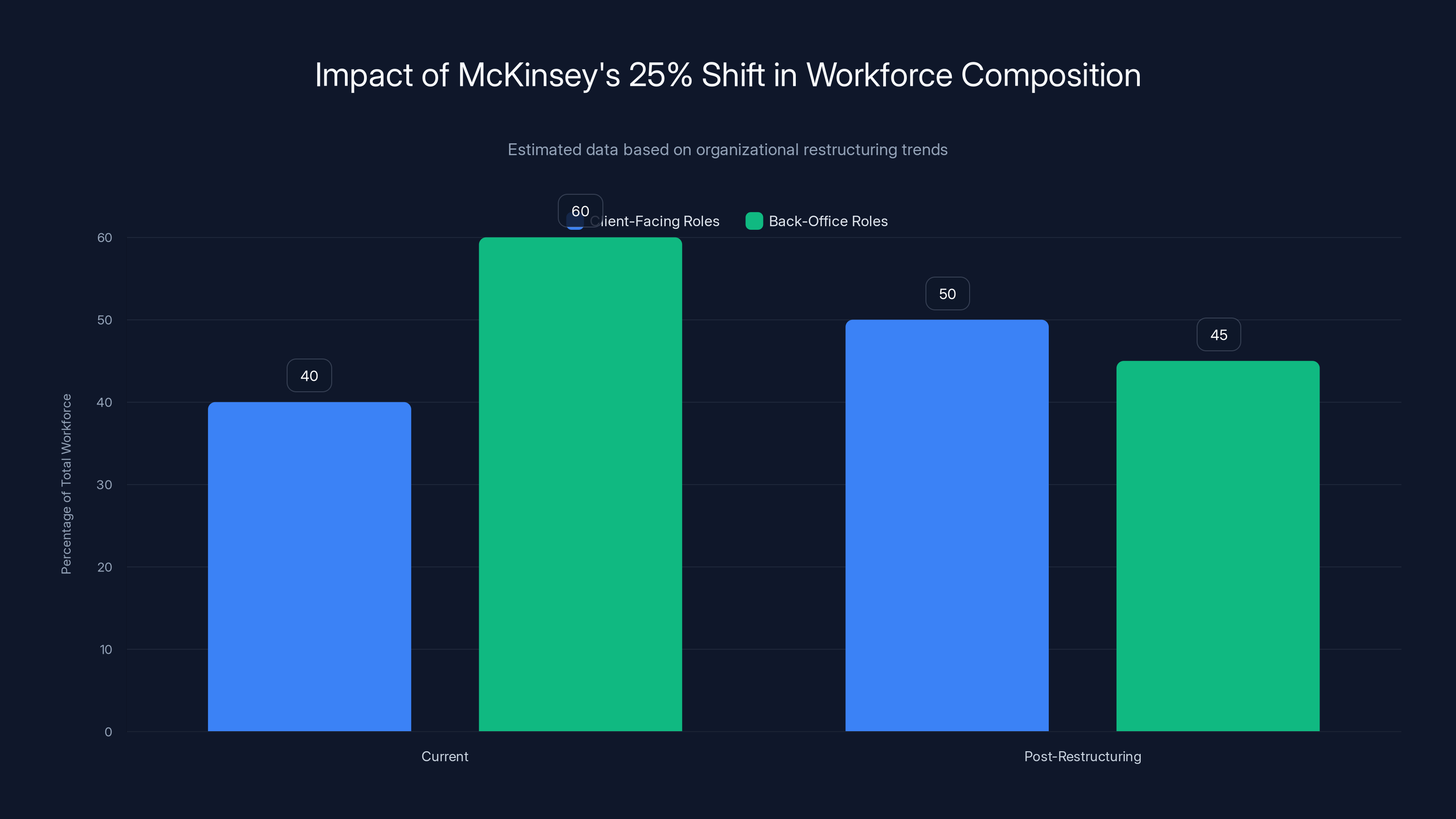

Organizational Restructuring: The 25% Shift McKinsey Is Making

Sternfels revealed something that most organizations will copy: McKinsey is explicitly restructuring around AI.

Headcount won't decrease. That was the key insight. McKinsey isn't planning mass layoffs. But composition will shift dramatically. They're increasing employees who work directly with clients by 25% while reducing back-office roles by the same percentage.

What does that actually mean? Today, a typical consulting firm has a certain ratio of client-facing staff to internal support staff. Researchers, analysts, data processors, report builders, scheduling coordinators—all the roles that support the client-facing work.

AI handles most of that support work. So instead of hiring more support staff, McKinsey is hiring more consultants. The same 1,000 consultants can now serve more clients, do more complex work, and generate more revenue because their support infrastructure is partially automated.

But here's what's crucial: those 25% of eliminated back-office roles aren't coming back as different jobs. They're gone. The people in those roles have three options: reskill into client-facing work (which requires different abilities and mentality), move to a different company, or exit the labor force.

This is where the cheerful framing of "we're adding roles" masks a darker reality: you're being displaced, and whether you land on your feet depends entirely on your ability to reskill quickly.

For organizational leaders, this represents an existential HR challenge. How do you manage the displacement of 25% of your workforce while maintaining culture and institutional knowledge? How do you upskill thousands of people in months? What's the ethical framework for this transition?

These questions don't have polished answers yet. But every large organization is grappling with them.

McKinsey's restructuring involves increasing client-facing roles by 25% while reducing back-office roles by the same percentage. Estimated data reflects a typical shift in workforce composition.

The Speed Factor: Building AI Agents Faster Than Training People

Calacanis made an observation that captures the economic logic of this entire transition: "In a world where it may take less time to build an AI agent than to train a new worker, people must find ways to stay relevant."

Think about the math. How long does it take to hire and fully train a junior analyst? Typically 3-6 months of onboarding, ramping, and hands-on training before they're genuinely productive. That's 3-6 months of payroll, management time, errors, and slow starts.

How long does it take to build a specialized AI agent trained on your company's data, processes, and decision-making patterns? Today, with off-the-shelf tools and a bit of customization, you can get a working AI agent in weeks. Maybe even days. The cost trajectory is also different: once built, the marginal cost of running the AI agent is essentially zero. Whereas the marginal cost of paying the junior analyst keeps increasing with raises, benefits, and overhead.

The incentive structure is completely inverted. Building and deploying AI becomes more cost-effective than hiring and training humans for routine work.

This has profound implications for career planning. If you're in a role where your primary value is executing tasks (analysis, coding, writing, research, administration), and that role can be replaced by an AI agent that deploys faster and costs less, then your value isn't in doing the work. Your value is in directing, evaluating, and improving the AI's work.

That's a different role. Which requires different skills. Which loops back to the skilling requirement.

The speed advantage of AI isn't just about technology. It's about economics. And economics always win.

Who Wins and Who Loses: The Emerging Bifurcation

Looking at the landscape that Sternfels and Taneja are describing, you can identify clear winners and losers.

Winners include:

- AI-native companies like Anthropic and OpenAI that are setting the pace for capability development

- Companies that move fast on adoption and restructure around AI quickly, gaining productivity advantages

- People with judgment, creativity, and deep domain expertise who can shape and direct AI systems

- Organizations that invest in reskilling infrastructure and help their teams transition

- Educators and training companies building the curriculum for continuous learning

Losers include:

- Companies that wait and optimize gradually, watching competitors gain advantage

- People whose primary skill is task execution with no path to higher judgment roles

- Entry-level career paths that were traditionally the training ground for future leaders

- Organizations with rigid hierarchies that can't restructure quickly

- Geographic or demographic groups that lack access to reskilling opportunities

The bifurcation isn't evenly distributed. It's concentrated. And it's visible in real time if you know where to look.

Estimated data shows a balanced focus between CFO and CIO on AI adoption, with a significant portion still undecided. This highlights the tension in decision-making.

The Investment Angle: Why VCs Are Pouring Billions Into AI

Taneja's vantage point as a venture capitalist provides crucial insight into why the AI explosion is happening so explosively.

Traditional venture returns follow a power law: a few wins generate enormous returns; most investments fail or succeed modestly. But AI is breaking that pattern. Instead of needing a single blockbuster exit, VCs are discovering that if they've invested in the AI infrastructure layer, they benefit from the entire ecosystem's growth.

Invest in a large language model? If it becomes standard infrastructure, you win across every application built on top of it. Invest in AI agents for specific industries? If adoption accelerates (which it is), you win through portfolio velocity.

The returns are happening faster because the deployment is happening faster. A traditional SaaS company takes 5-7 years to reach significant ARR (annual recurring revenue). An AI infrastructure company can reach that in 18-24 months because adoption curves are steeper.

That attracts more capital. More capital funds more innovation. More innovation drives faster adoption. It's a virtuous cycle for the technology and a challenging one for everyone else trying to keep up.

From a pure capital allocation perspective, Taneja's prediction about trillion-dollar AI companies isn't speculation. It's extrapolation from current trends.

The CFO Problem: Why Financial Realities Complicate the Narrative

Let's go back to that tension between the CFO and CIO for a moment, because it's worth exploring more deeply.

The CFO isn't being obstinate. They're being prudent given incomplete information. Here's the challenge: most AI projects don't generate immediate financial returns. They generate capability improvements that are hard to quantify.

Say you deploy an AI system to assist customer service. You measure outcomes: same number of customer service reps, same costs, but tickets are resolved faster. That's a 15% improvement in throughput. How much is that worth?

Depends on whether you're reallocating those reps to higher-value work or treating it as a cost-saving measure. In many organizations, the improvement just disappears into general efficiency, and you don't see a line item on the balance sheet showing the value.

That's a CFO's nightmare. They can see the cost of the AI system clearly. License fees, infrastructure, implementation, training. But the benefit is diffuse and hard to measure. In that context, caution is reasonable.

The CIO sees it differently because their success metrics are different. They care about capability, competitive positioning, and strategic risk. Being a year behind on AI adoption feels like an existential threat. But they also struggle to quantify the upside.

This tension is healthy in some respects—it prevents reckless spending. But it also creates slow decision-making at exactly the moment when speed matters.

Companies that crack this nut—that figure out how to measure AI ROI and build financial cases that convince CFOs—will move faster than competitors stuck in the debate.

AI adoption is estimated to reduce entry-level positions by 15-30% in various industries, with tech and finance seeing the highest impact. Estimated data.

The Talent Implications: Where Do High Performers Go?

Here's a second-order effect that's worth considering: if large organizations are restructuring and eliminating roles, where do the displaced people go?

Some will reskill into new roles within their organization. But others will migrate to startups, to smaller companies, or to new ventures entirely. There's a historical pattern: when large companies go through disruption, talented people leave to start new things. Some of those new things become the next generation of category leaders.

So the same AI disruption that's eliminating roles at McKinsey might be fueling a new wave of startup formation. The very consultants who understand how this transition works might become founders of AI-native consulting firms that operate entirely differently.

This creates a strange dynamic: the companies adapting fastest to AI disruption might inadvertently seed the creation of new competitors better adapted to the AI-native world.

That's not a reason to slow down restructuring. It's just a reminder that disruption doesn't solve the problem; it redistributes it.

What Young Professionals Should Actually Do Right Now

So let's answer Calacanis's original question directly: what should young people do in this landscape?

First, accept that the "safe" career path is less safe than you think. Picking a stable company and a stable role and expecting to build deep expertise there for 20 years is a bet against the velocity of change. It might work, but it's increasingly risky.

Second, build judgment and taste. Read widely. Learn different industries, different domains, different perspectives. The goal isn't to become a specialist in one thing; it's to develop the ability to recognize patterns and make good decisions across domains. That's the skill that survives disruption.

Third, pick companies that are moving fast on AI adoption, even if it feels chaotic. Yes, there's risk. But there's also access to the best learning environment. You're watching how companies restructure. You're learning which skills matter. You're building relationships with other smart people figuring this out. That education is worth more than safety.

Fourth, invest in skills that are complementary to AI, not competitive with it. Want to learn coding? Sure, but focus on system design and architecture, not writing functions that could be generated by AI. Want to learn analysis? Sure, but focus on problem definition and insight synthesis, not number-crunching.

Fifth, build your own thing. If the economics of hiring are being disrupted, the economics of starting small are improving. You can now build products with a tiny team because AI handles work that used to require teams of people. That's not a bad position to be in.

How Organizations Should Think About Restructuring

If you're leading an organization—whether it's a 50-person company or a 10,000-person firm—the McKinsey example provides a blueprint, but the implementation matters enormously.

The naive approach: remove back-office roles, fire people, save money. This is usually disastrous. You lose context, expertise, relationships, and culture. Your remaining team is demoralized. Customers notice.

The sophisticated approach: restructure gradually, invest heavily in reskilling, be transparent about why, and create pathways for people to land on their feet. Some people will move into client-facing roles. Some will take on new internal roles that didn't exist before (AI agent training, AI output quality assurance, AI system refinement). Some will move to different companies, and you help them do it.

McKinsey's 25% shift is happening over multiple years, not overnight. They're not surprising people with termination notices; they're redefining what role people do next.

That approach costs more money and takes more time. It's also sustainable and preserves organizational health.

Companies racing to AI adoption without thinking about the human side will win in the short term and lose in the medium term when they've destroyed institutional knowledge and culture.

The Broader Economic Picture: Productivity Gains That Need Somewhere to Go

Step back and think about the macro dynamics here.

AI is delivering legitimate productivity improvements. Not hype, not exaggerated promises, but real 20-40% improvements in output per worker for knowledge work. Multiply that across millions of knowledge workers, and you're talking about trillions of dollars in economic value.

Historically, productivity gains from technology translate into economic growth, which creates new jobs to replace the old ones. The Industrial Revolution eliminated agricultural jobs and created factory jobs. Automation eliminated factory jobs and created service jobs. The internet eliminated some service jobs and created digital jobs.

But here's what's different about AI: it's not just eliminating specific categories of jobs. It's compressing the middle. The routine execution work is being automated. The high-judgment work is still needed. But there's less of the middle.

What new jobs get created? That's the genuine uncertainty. Most predictions are speculation. But historically, new jobs emerge in areas we don't fully anticipate. They emerge from new capabilities becoming possible, new problems we can finally solve, new industries that form.

The AI wave will likely create new categories of work. But there's no guarantee that:

- The new jobs are in the same geographic locations as the old jobs

- The new jobs pay as much as the old jobs

- People displaced from old jobs can transition to new jobs

- The transition happens quickly enough to avoid significant disruption

That's why the reskilling imperative is so critical. In previous technological transitions, people could sometimes move industries without major retraining. You could move from one factory job to another. Now you can't move from "routine analytical work" to another "routine analytical work" because that category is compressing. You have to move to judgment-intensive work, which requires different skills.

The Role of Education: Why Traditional Models Are Inadequate

Universities and training programs are struggling to adapt to this reality.

The traditional model is: students attend school, learn a specific domain (finance, engineering, marketing), graduate, and work in that field for 30+ years. The model assumed domain knowledge was stable and valuable.

Now domain knowledge has a shorter half-life. The finance knowledge you learn in your junior year might be partially obsolete by graduation. The coding practices you learn in school might be replaced by AI-native approaches by the time you enter the workforce.

The educational system is structured around static knowledge delivery. But the need is for dynamic adaptation. Schools are structured to teach "what is." The market needs "how to learn continuously."

This is solvable, but it requires fundamental change. More emphasis on metacognition (learning how to learn) than domain knowledge. More emphasis on judgment and taste. More emphasis on failure, iteration, and adaptation. More emphasis on soft skills that are genuinely hard to automate.

Some schools are moving in this direction. Most aren't. That creates an opportunity for new educational models—bootcamps, online communities, apprenticeships, corporate training—that focus on what actually matters in an AI-native world.

Preparing for an Uncertain Future: Frameworks for Thinking About Your Career

Given all this uncertainty, how should individuals actually plan their careers?

Start with these principles:

1. Assume change is continuous. Don't plan for stability. Plan for perpetual adaptation. That changes how you allocate time and resources.

2. Build optionality. Instead of specializing deeply in one thing, develop multiple competencies. It's easier to move to a new field if you have adjacent skills.

3. Invest in relationships. When the technical landscape changes rapidly, your network becomes your safety net. People will know you. They'll think of you for new opportunities. Networks are more stable than skills.

4. Choose learning environments over prestige. A role at a mediocre company where you learn how to navigate rapid change is more valuable long-term than a prestigious role at a slow-moving company.

5. Track your skill decay. Periodically (quarterly?) assess which of your current skills are becoming less valuable and which emerging skills you should invest in. Treat it like portfolio rebalancing.

6. Experiment with new domains. Spend 10-20% of your time learning something outside your current domain. You might not use it directly, but it builds pattern recognition across domains, which is valuable.

These aren't comfortable recommendations. They require ongoing effort, discomfort, and acceptance that you'll never fully "arrive." But they're honest about the world we're actually living in, not the world we might prefer.

The Unspoken Challenge: What Happens to Displaced Workers?

In the discussion between Calacanis, Sternfels, and Taneja, there was an implicit assumption that everyone can reskill. That's not obviously true.

Reskilling takes time, energy, cognitive bandwidth, and often money. It's easy for consultants and venture capitalists to say "lifelong learning" when they work in high-abstraction environments where learning happens naturally. It's harder for someone working three jobs or supporting a family to find time to reskill.

It's also not true that reskilling leads equally to good outcomes. Someone who reskilled from manufacturing into coding might earn more. Someone who reskilled from retail into customer service might earn slightly less. Some reskilling paths lead to abundance. Others lead to diminished returns.

The cheerful tech narrative is "everyone can learn; everyone can adapt." The reality is more complicated. Some people will adapt successfully. Others will experience downward mobility. Still others will exit the labor force.

That has policy implications. If economic disruption is real and widespread, then policy responses matter. Unemployment insurance. Healthcare decoupling from employment. Education and training subsidies. Basic income. These aren't radical ideas; they're practical responses to distributed disruption.

The tech industry doesn't usually talk about this because it's uncomfortable and political. But it's worth thinking about, especially if you're making decisions about workforce restructuring.

Looking Forward: What 2027 Likely Brings

Based on the current trajectory and the observations from these leaders, a few things seem likely.

AI capabilities will become more specialized and more powerful. The frontier models (GPT, Claude, Gemini) will push further. But more importantly, specialized AI agents trained on specific domains and datasets will become extremely effective. We'll stop talking about "general AI" and start talking about "specialized systems that outperform humans in domain-specific tasks."

Adoption will accelerate in specific domains while lagging in others. Knowledge work will see faster adoption than physical work. White-collar disruption will be visible and talked about. Blue-collar disruption will happen but will be less discussed. Some industries will move 80% of the way to AI-native models. Others will still be in pilot phases.

The labor market will show clear bifurcation. Jobs that are routine and instruction-based will continue to compress. Jobs that require judgment, creativity, and domain expertise will grow or remain stable. Wages in the judgment jobs will increase; wages in routine jobs will stagnate or decrease.

Organizational structures will continue shifting toward fewer middle layers. The 25% shift McKinsey is making will be replicated across professional services, finance, consulting, and eventually other sectors. Flatter organizations with more direct client/user contact and fewer support roles.

The reskilling industry will boom. Education, training, bootcamps, online learning, corporate training programs—these will be among the fastest-growing sectors. Companies need to reskill their people. Individuals need skills. That creates genuine market demand.

Questions about fairness and inclusion will become unavoidable. If the benefits of AI productivity accrue to capital and high-skill labor while disruption hits middle-skill workers, you have a political problem. Tech companies will have to engage with these questions whether they want to or not.

The next 18-24 months will be crucial. This isn't the beginning of disruption; it's the beginning of widespread awareness of disruption. The timeline that seemed distant in 2023 is arriving in 2025.

The Bottom Line: Action Is Required

Let me be direct: if you haven't started thinking seriously about how AI changes your career or your organization, you should start now. Not next year. Not next quarter. Now.

That doesn't mean panic. It means clarity. It means understanding the specific ways your industry and role are being reshaped. It means identifying the skills that will matter in 2027, 2030, and beyond. It means taking concrete steps to build those skills or ensure your organization is positioned well.

For individuals: the learning curve is real. Embrace it. Pick skills that are complementary to AI, not competitive. Build judgment and taste. Invest in relationships. Create optionality.

For organizations: the restructuring is coming. Be thoughtful about how you execute it. Invest in reskilling. Be transparent with your people. Think long-term about culture and capabilities, not just short-term cost-savings.

For policymakers and educators: the disruption is real, and there's a policy and education challenge here. Upskilling infrastructure matters. Support for displaced workers matters. Educational innovation matters.

For investors: this is still the beginning. The winners in the AI wave haven't been fully determined. But they will be, and the decision-making windows are closing. Being thoughtful about where capital goes matters.

"Learn once, work forever" is dead. The new model is "learn continuously, adapt perpetually, and use judgment in an AI-augmented world." That's the reality these leaders were describing. It's uncomfortable. It's also not optional. You can embrace it consciously or you can stumble into it unprepared. The first option seems better.

FAQ

What does it mean that "learn once, work forever" is over?

The traditional career model assumed you learned a skill in school, then applied that knowledge for 30-40 years with only incremental updates. That model broke because AI is creating continuous disruption. Skills have shorter half-lives. Jobs evolve faster. People now need to reskill multiple times within a career, not once or twice. It's fundamentally different from the historical pattern.

Why are companies like McKinsey restructuring their workforce right now?

AI is automating routine analytical and administrative work. Rather than keeping the same number of people and losing productivity, companies like McKinsey are increasing client-facing roles (where the real value is) and reducing back-office roles (where AI handles the work). This 25% shift happens because the economics now favor deploying AI rather than hiring people for routine tasks.

What skills are most important in an AI-driven world?

According to these leaders, the skills that survive are judgment, creativity, initiative, and domain expertise. Routine task execution—the work that AI handles well—becomes less valuable. What remains is the ability to recognize when AI is wrong, shape its outputs, ask better questions, and make decisions based on judgment rather than following instructions. These are fundamentally human skills.

How quickly do entry-level jobs disappear?

The compression is already visible in hiring data from 2024-2025, though it hasn't been widely publicized. Companies aren't eliminating junior roles immediately, but they're hiring fewer of them because AI handles the work that used to train junior employees. This creates a bottleneck: fewer people have the opportunity to learn through entry-level work, which was historically how people built early-career experience.

What's the difference between CFOs and CIOs on AI adoption?

CFOs focus on financial returns and risk. They see the implementation costs and limited immediate financial gains, so they favor caution. CIOs focus on competitive positioning and strategic capability. They see competitors moving faster and fear being disrupted, so they favor rapid adoption. Both perspectives are rational; the tension is real, and companies that can reconcile it move faster than those stuck in debate.

How should someone prepare for the work of 2027 and beyond?

Start learning skills that are complementary to AI now: domain expertise, judgment frameworks, creativity, communication, relationship-building. Build optionality by developing multiple competencies rather than specializing in one thing that might be automated. Invest in learning environments where you see how companies adapt to rapid change. Track which of your current skills are becoming less valuable and proactively develop emerging skills. Think of career development as continuous, not episodic.

Is there really enough demand for new jobs to replace the ones that AI eliminates?

That's genuinely uncertain. Historically, major technological disruptions did create new job categories we didn't anticipate. But there's no guarantee new jobs will emerge fast enough, pay as much, or be geographically accessible to displaced workers. That's why proactive reskilling and policy support matter. The market might eventually equilibrate, but the transition could be disruptive for millions of people.

What are the biggest risks of AI disruption that aren't being discussed?

Three major ones: First, the assumption that everyone can reskill is optimistic. Some people will struggle, and downward mobility is possible. Second, the geographic and demographic distribution of disruption might be uneven, creating regional or demographic winners and losers. Third, if the benefits of AI productivity accrue primarily to capital and high-skill labor while disruption hits middle-skill workers, you have a significant fairness and political problem. These aren't technology problems; they're policy and human problems.

How does AI adoption speed differ from previous technological revolutions?

Previous revolutions (Industrial Revolution, Automation, Internet) took 20-40 years to fully restructure the labor market and create new job categories. AI's adoption curve appears to be compressing that timeline significantly. Changes that took a decade are now happening in months. This speed is what makes the current moment so challenging: there's less time for gradual adaptation, both for individuals and organizations.

Should I stay in my current role or look for a different one?

That depends on: (1) Whether your company is moving fast on AI adoption (fast movers are better learning environments), (2) Whether your current role is complementary to AI or competitive with it, (3) Whether you have access to reskilling opportunities, (4) Whether your current skill set is in demand or declining in value. If you're in a slow-moving company doing routine work, moving to a fast-moving company doing judgment work is generally better for long-term prospects. But it's industry and role specific.

What's the realistic timeline for major labor market shifts?

Based on current adoption curves, 2025-2027 will show visible shifts in hiring patterns, role composition, and skill demand. 2027-2030 will likely see more pronounced restructuring as companies that moved fast gain advantages and pressure others to keep up. By 2030, the labor market will probably look quite different from 2023, with clearer bifurcation between judgment-intensive work and routine work, and fewer entry-level roles than the historical norm. That's not a prediction; it's pattern extrapolation from current trends.

Use Case: Automate your weekly reports and status updates with AI while you focus on strategic decisions and judgment calls that actually matter.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- The 'learn once, work forever' career model is dead; continuous reskilling is now required for relevance

- AI company valuations are 10-20x faster than traditional companies (Anthropic 100B+ in months vs Stripe 12 years to $100B)

- Organizations like McKinsey are restructuring: adding 25% client-facing roles while reducing back-office roles by 25% through AI automation

- Entry-level job compression is already visible in 2024-2025 hiring data as AI handles work that traditionally trained junior employees

- Skills that survive are judgment, creativity, and initiative—routine task execution is being automated across knowledge work

- Deploying specialized AI agents takes 2-6 weeks; training humans takes 3-6 months, creating powerful economic incentive for automation

- The labor market is bifurcating: judgment-intensive roles growing, routine execution roles compressing, fewer middle-skill opportunities

- Reskilling infrastructure and policy support are critical because not everyone can adapt equally—displaced workers face real risk

Related Articles

- Acer at CES 2026: Three Must-See Innovations [2025]

- Lenovo Legion Pro Rollable: Complete Guide & Alternatives [2025]

- Lenovo's Qira AI Platform: Transforming Workplace Productivity [2025]

- Lenovo ThinkBook Plus Gen 7 Auto Twist: The Dual-Axis Rotating Laptop [2025]

- Lenovo ThinkPad X1 Carbon Gen 14: Sub-1kg Powerhouse [2025]

- Motorola Razr Fold vs Galaxy Fold 7: Which Foldable Wins [2025]

![Why 'Learn Once, Work Forever' Is Dead: AI's Impact on Skills and Work [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-learn-once-work-forever-is-dead-ai-s-impact-on-skills-an/image-1-1767756974795.png)