Introduction: When a Streaming Show Finally Needed a Theater

There's a moment when you realize something fundamental about how we consume entertainment has shifted. For me, that moment came in a packed IMAX auditorium on New Year's Eve, watching the final episode of Stranger Things unfold on a 75-foot screen with 300 strangers who all felt like they were living through the same emotional event.

The parking lot at Neshaminy Mall in Bensalem, Pennsylvania was overflowing. That's not hyperbole. This is a shopping center that's mostly shuttered, a ghost town by almost any measure, with entire sections of the building scheduled for demolition. The AMC theater there—one of only three IMAX venues in the Philadelphia area—is genuinely one of the few remaining reasons to visit. I've been there countless times as a critic, watching major releases on that massive screen. But I've never seen anything like what happened on December 31st.

The concession line wrapped back toward the lobby. Free tickets meant a $20 voucher purchase requirement, which nearly everyone had already bought. People were buying the premium snacks, the large sodas, the candy combos. The energy was electric in a way I haven't felt since the Barbenheimer moment in 2023, when movie theaters felt culturally relevant again. This was disconcerting because I knew something intellectually: Stranger Things was massive. But feeling it in a parking lot packed with 500 people who all showed up to watch the same episode at the same moment? That was something else entirely.

This theatrical release of Stranger Things 5: The Finale represents something unprecedented in the streaming era. Netflix, a company that built its empire on the convenience of watching anything anytime anywhere, essentially admitted that sometimes the old way of doing things—gathering in public, in the dark, as a community—delivers something no home theater setup can replicate. The phenomenon this created illuminates a critical weakness in streaming's otherwise dominant approach to content consumption, and raises hard questions about what we've traded away in our rush toward convenience.

TL; DR

- Theatrical streaming events are reshaping how tentpole shows reach audiences, combining the intimacy of home viewing with the communal power of cinema

- Netflix's biggest challenge isn't competition from other services, it's creating cultural moments that feel shared and collective rather than isolated and algorithmic

- The Stranger Things finale proved that 75-foot screens and shared emotional beats drive engagement differently than binge-watching alone in your living room

- This represents a hybrid future for streaming content, where major finales, specials, and event episodes get theatrical releases as a strategic play

- The entire entertainment industry may be shifting back toward event-based viewing, treating mega-finales like Star Wars or MCU installments rather than serialized TV

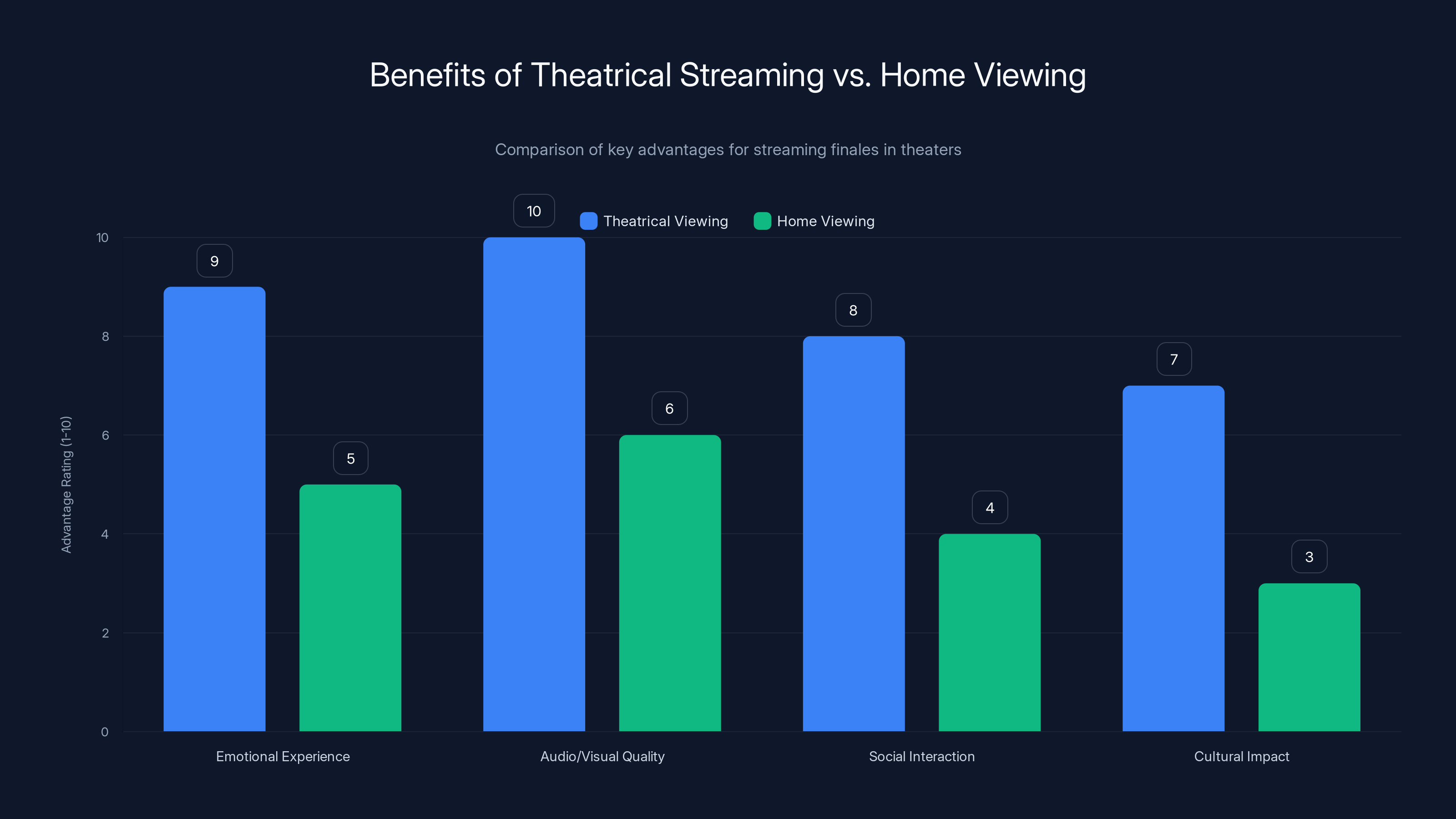

Theatrical streaming offers superior emotional and social experiences, as well as enhanced audio/visual quality, compared to home viewing. Estimated data based on typical viewing experiences.

The Paradox Netflix Created: Massive Audiences That Feel Invisible

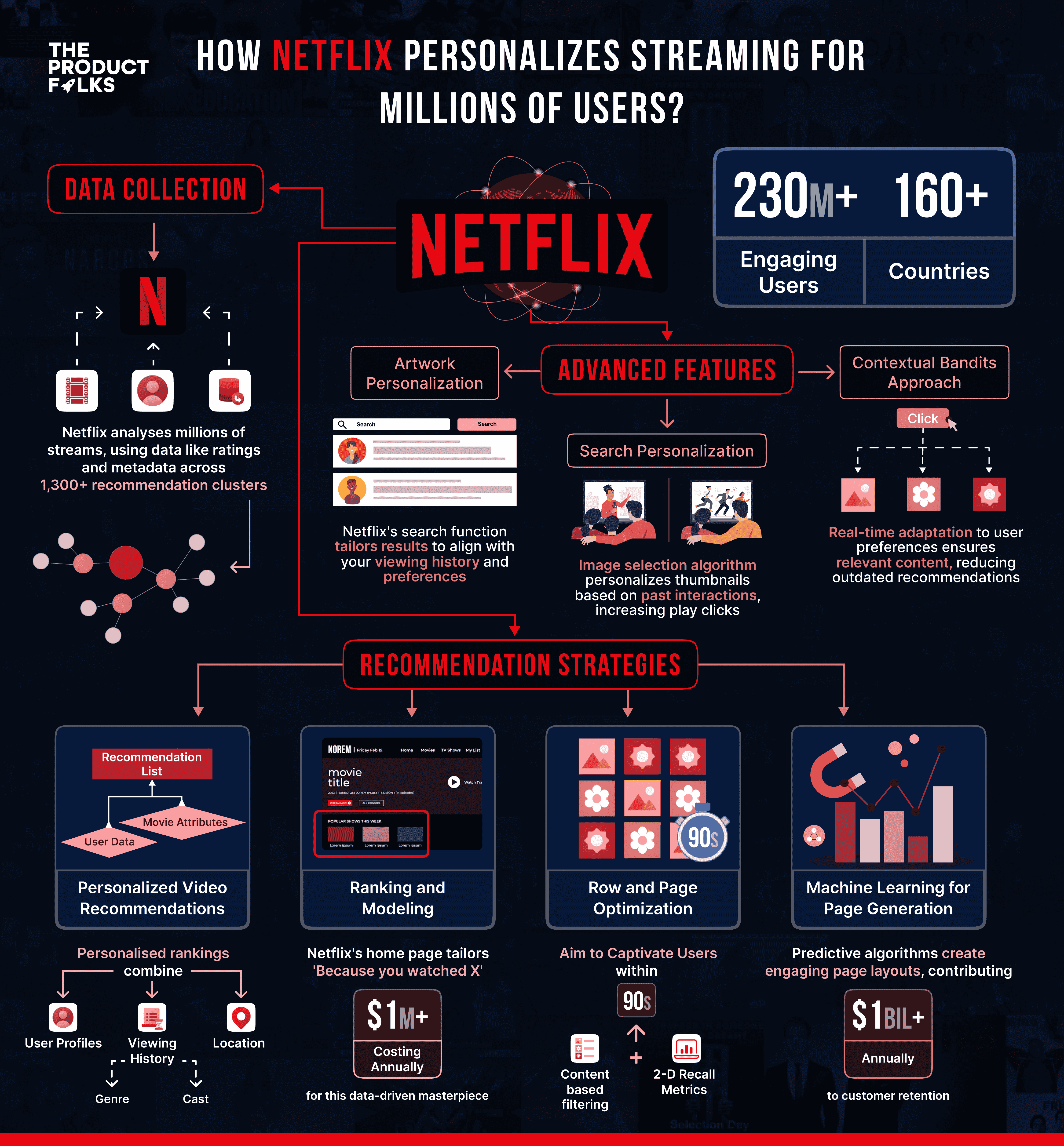

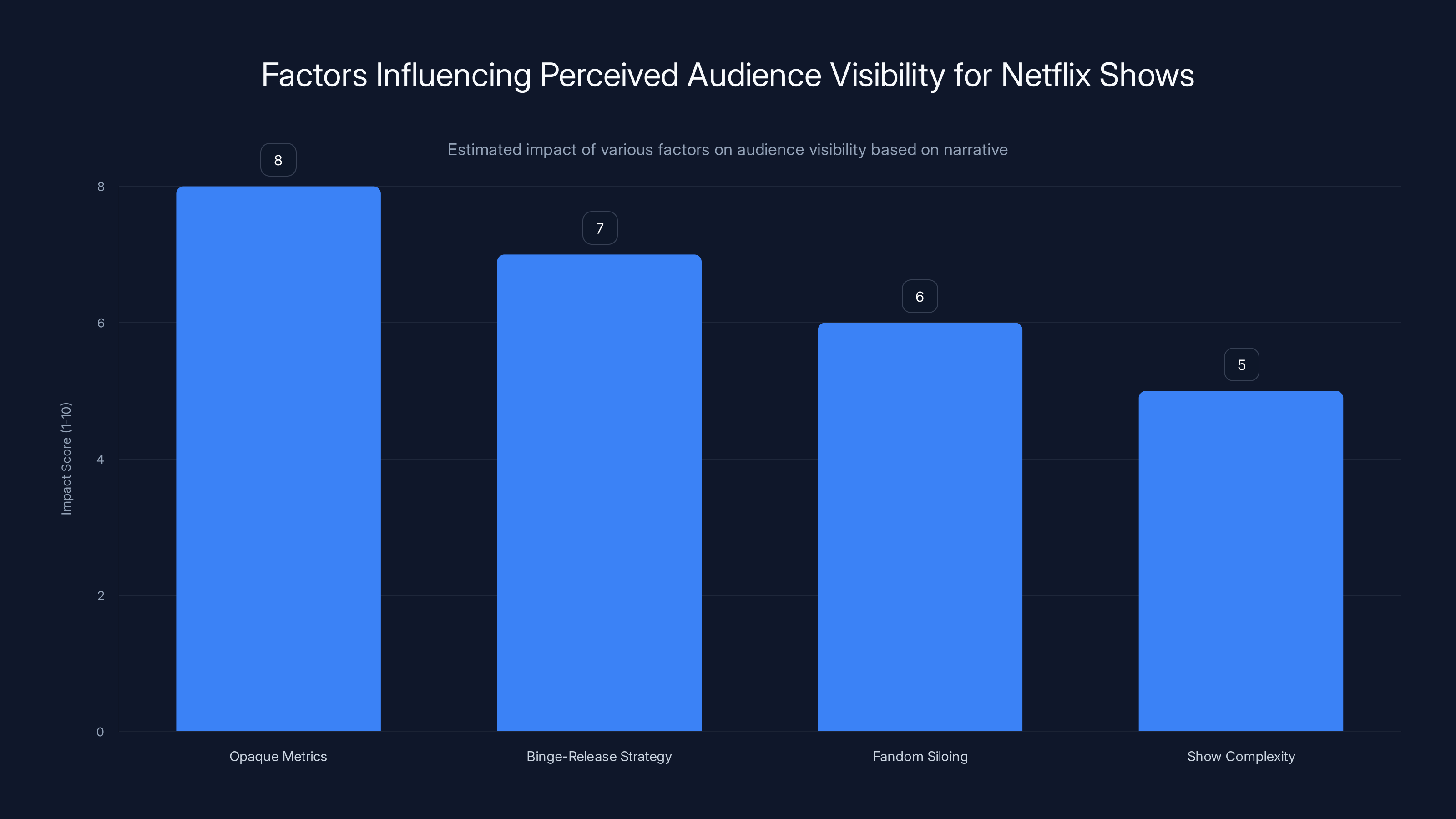

Netflix is aggressively opaque about its metrics. The company shares almost nothing publicly about actual viewing numbers, subscriber engagement, or any concrete data that would let independent observers actually verify what's working. What we do know comes from occasional PR announcements and the rare moments when Netflix's own infrastructure becomes the proof—like when a new season crashes the service because so many people are trying to watch simultaneously.

But Stranger Things has always been treated differently. Netflix puts real marketing muscle behind it. The cast shows up in ads, brand partnerships, and cultural moments that no other Netflix original gets. Kate Bush's "Running Up That Hill" returned to the charts because of Season 4. The show's iconography shows up everywhere. Netflix regularly announces viewing records that, even if you discount for their tendency toward favorable presentation, clearly indicate something massive is happening.

Yet walking around, talking to friends, scrolling through social media—it's hard to feel that. The internet is fractured. Fandoms exist in Discord servers and Tik Tok trends and Reddit threads, siloed off from mainstream conversation. Netflix's binge-release strategy, where entire seasons drop at once, theoretically gives everyone the same viewing window but actually destroys momentum. Instead of building week-to-week conversation and theory, everyone watches at their own pace. The person who binges all ten episodes in one weekend lives in a different temporal reality than someone who watches two episodes a week.

There's another factor: the show itself. Stranger Things has never been complex in the way that generates endless analysis. The Duffer Brothers have always been straightforward about what they're doing. The show wears its influences on its sleeve. Every reference gets explained. Every mystery gets solved by the end of the season. The Upside Down—this vast, terrifying dimension—is eventually revealed to be basically empty, a bridge between worlds rather than an actual place with its own internal logic to dissect.

This simplicity is actually a strength. It means the show is genuinely accessible to all kinds of viewers. Your eight-year-old can watch it and understand the plot. Your 68-year-old grandparent can follow the story. Casual viewers don't feel lost. Die-hard fans still find things to love. But it also means there's no mystery to sustain parasocial engagement. There's nothing to theorize about that the show won't directly address.

The result: Stranger Things became culturally massive while simultaneously feeling culturally invisible. Millions watched it. Few discussed it. The phenomenon happened everywhere and nowhere simultaneously.

Why Theaters Feel Dead Until They Don't

Movie theaters have been in structural decline for years. The pandemic accelerated a trend that was already happening. Streaming services offered convenience at a moment when going outside felt risky. Once people got used to watching movies at home, retrofitting that habit proved difficult. Theater attendance has recovered somewhat, but not to pre-pandemic levels. AMC, the largest theater chain, has been in and out of bankruptcy discussions. Independent theaters have closed. The theatrical experience increasingly feels like a luxury choice rather than a default option.

The common wisdom is that only certain movies can justify the theatrical experience now: blockbusters with world-ending stakes, spectacle that demands an enormous screen, things that genuinely lose something fundamental when transferred to a home TV. Marvel movies. Fast movies about cars. Superhero stuff. Anything where you're paying for scale and special effects.

TV finales have never qualified. Even the biggest shows—the finale of Game of Thrones, the conclusion of Breaking Bad—happened on regular screens in people's homes. The idea of renting out entire theaters to watch a 50-minute episode would have seemed absurd five years ago. The economics don't work. The theatrical window for major films is already disappearing (studios are pushing movies to streaming faster each year). Adding TV episodes to the mix seems backwards.

Yet here's what's strange: it worked. The Stranger Things finale didn't just pack theaters, it created an event. People made the decision to leave their homes, drive to a theater, buy overpriced snacks, and sit in the dark with hundreds of strangers to watch something they could have watched at home on their $3,000 TV. Enough people made that choice simultaneously that parking lots overflowed and concession lines became genuinely overwhelming.

Why? Because community is something you can't stream. You can't download it. You can't add it to your watchlist and get to it later. The moment either exists or it doesn't.

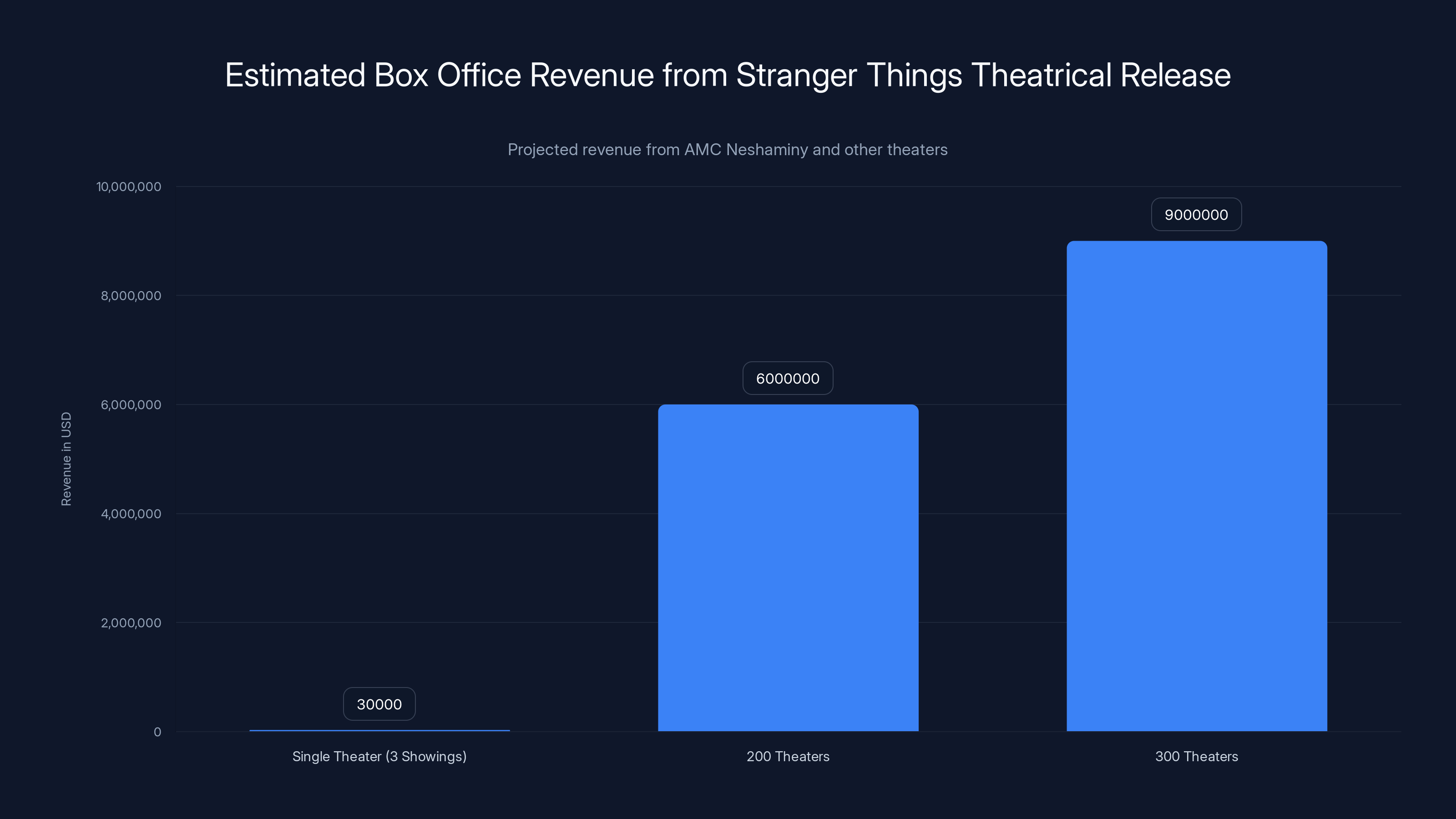

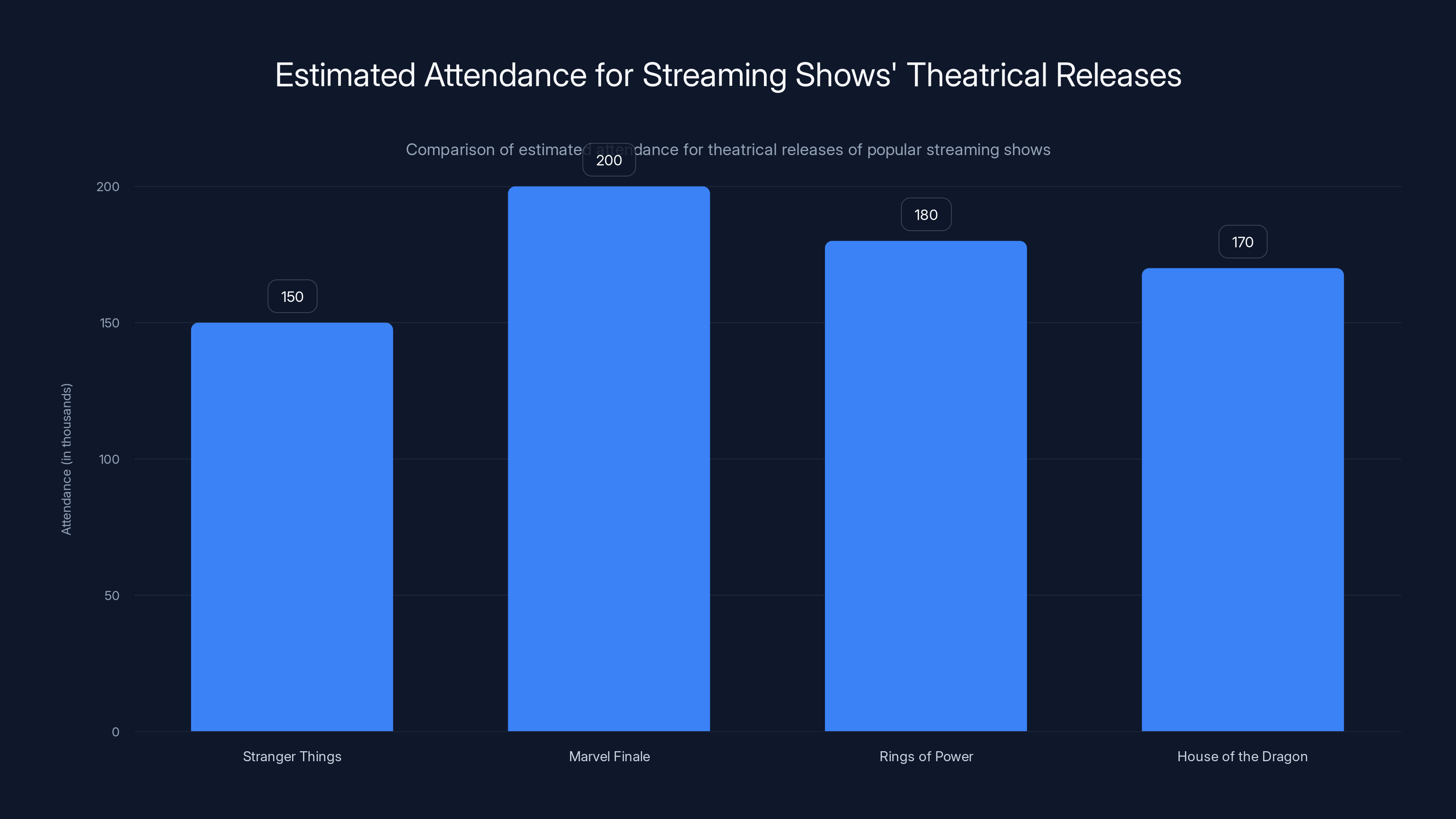

Estimated data suggests $6-9 million in revenue from 200-300 theaters, which is modest compared to Netflix's scale. Estimated data.

The Lost Art of Synchronized Viewing

For most of human history, if you wanted to watch something with other people, you had to be in the same physical location at the same time. That was just how it worked. A TV show aired at 8 PM on Thursday, and if you wanted to watch it and discuss it the next day, you had to be home at 8 PM on Thursday. Miss it and you had to either catch reruns or rely on someone recording it (in the VCR era) or just accept that you were out of the conversation.

That limitation created culture in interesting ways. Everyone watched the same thing at the same moment. Water cooler conversations on Friday were about the episode that aired 24 hours earlier. You couldn't binge 10 seasons of a show you'd never seen—you watched week by week as it aired, over years, building investment slowly. The communal experience was built into the technology.

Streaming demolished this. The draw of streaming—watch anything, anytime, anywhere—sounds like freedom and actually is freedom. You're not chained to a schedule. You don't have to plan around a TV guide. If you want to watch five episodes of something on a Tuesday afternoon, you can. If you want to stop halfway through a season and pick it up three months later, nobody's forcing you to do anything different.

But something real was lost. The communal aspect didn't transfer well. A group chat of people all watching the same episode at the same time creates connection, but it's not the same as 500 people gasping in unison when something shocking happens, or laughing together at a joke, or sitting in shared silence at a devastating moment. Streams are inherently isolating because the medium assumes you're watching alone (or at least with only people in your immediate vicinity).

The Stranger Things finale in theaters recreated something that streaming destroyed. Everyone watched at the same moment. When something big happened, 300 people reacted together. That's not better or worse than home viewing—it's different. It's a fundamentally different experience, and it turns out a lot of people were hungry for it without quite realizing it.

Netflix's Quiet Admission: Streaming Alone Isn't Enough

Let's be direct about what happened: Netflix, the company that built a multi-hundred-billion-dollar empire on the premise that you don't need to leave your house to watch great entertainment, essentially conceded that sometimes you do need to leave your house. Sometimes gathering in public with other people to watch something is better. Sometimes a movie theater delivers something a living room doesn't.

This is profound. It's Netflix admitting that convenience isn't the whole story. It's admitting that cultural phenomena require more than just availability. It's admitting that streaming's atomization of viewership—everyone watching whenever they want, wherever they want—creates a fundamental problem: nobody feels like they're part of something larger.

Consider the scale: Game of Thrones' final season, which aired weekly on HBO, generated enormous cultural conversation (and enormous cultural backlash). The finale happened in May 2019 and dominated discourse for weeks. Did more people ultimately watch that finale than will watch the Stranger Things finale? Maybe. But the weekly release schedule created momentum. The finale was the culmination of a story people had watched unfold over eight years of weekly episodes. By the time it aired, you'd been conditioned to expect it, to prepare for it, to organize your life around it.

Netflix's binge model destroys that. You get all 10 episodes at once. Some people finish in a weekend. Some watch over a month. Some never finish at all. There's no cultural crescendo, no building sense of inevitability. It's just content, available whenever you feel like engaging with it.

The theatrical release is Netflix's attempt to artificially recreate that crescendo. Instead of building momentum through weekly episodes, they're building it through the physical experience. This is Episode 10 of Season 5. It's playing in select theaters for one night only. If you want to experience it the way it's meant to be experienced, you need to be there, tonight, in person.

It's manipulative, in a way. It's creating artificial scarcity for content that would otherwise be infinite. And it worked.

The Box Office Numbers: When Streaming Shows Become Box Office Events

No official box office numbers have been released for the Stranger Things theatrical release. Netflix is opaque about this stuff too. But anecdotal evidence from theater owners, critics who attended multiple venues, and social media reports suggests remarkable attendance. One theater in Manhattan reported selling out three consecutive showtimes. The Neshaminy location I visited added extra showings due to demand.

Compare this to typical streaming numbers, where you get nothing. Netflix won't tell you how many people watched the finale. They might eventually announce that Stranger Things 5 was "watched" by some number of millions of people, but those metrics are notoriously generous (Netflix counts you as having "watched" something if you watch even 2 minutes of it). You'll never know if people watched the whole thing, or 5 minutes, or just left it playing in the background.

The theatrical release creates a different kind of measurable. Tickets sold. Seats filled. Showing times added because demand exceeded supply. These are concrete, verifiable metrics that prove nothing but are psychologically more satisfying than "Netflix says people watched it."

For a company that guards its data like a fortress, that's meaningful. It's letting the market verify success in a way that streaming numbers typically don't.

What's interesting is whether this becomes a template. Will Disney+ release major Marvel finale episodes theatrically? Will Amazon do it for Rings of Power? Will HBO do it for House of the Dragon? The economics are still uncertain. Theater chains have thin margins. Adding TV content helps them fill seats and sell snacks, but they're also not seeing major cuts of those ticket sales (Netflix controls pricing). Studios get the revenue. Theaters get the foot traffic.

But the cultural precedent matters. Streaming shows can now be theatrical events. They can have opening nights. They can have sold-out midnight showings. They can be things you go out to experience rather than things you consume at home when convenient.

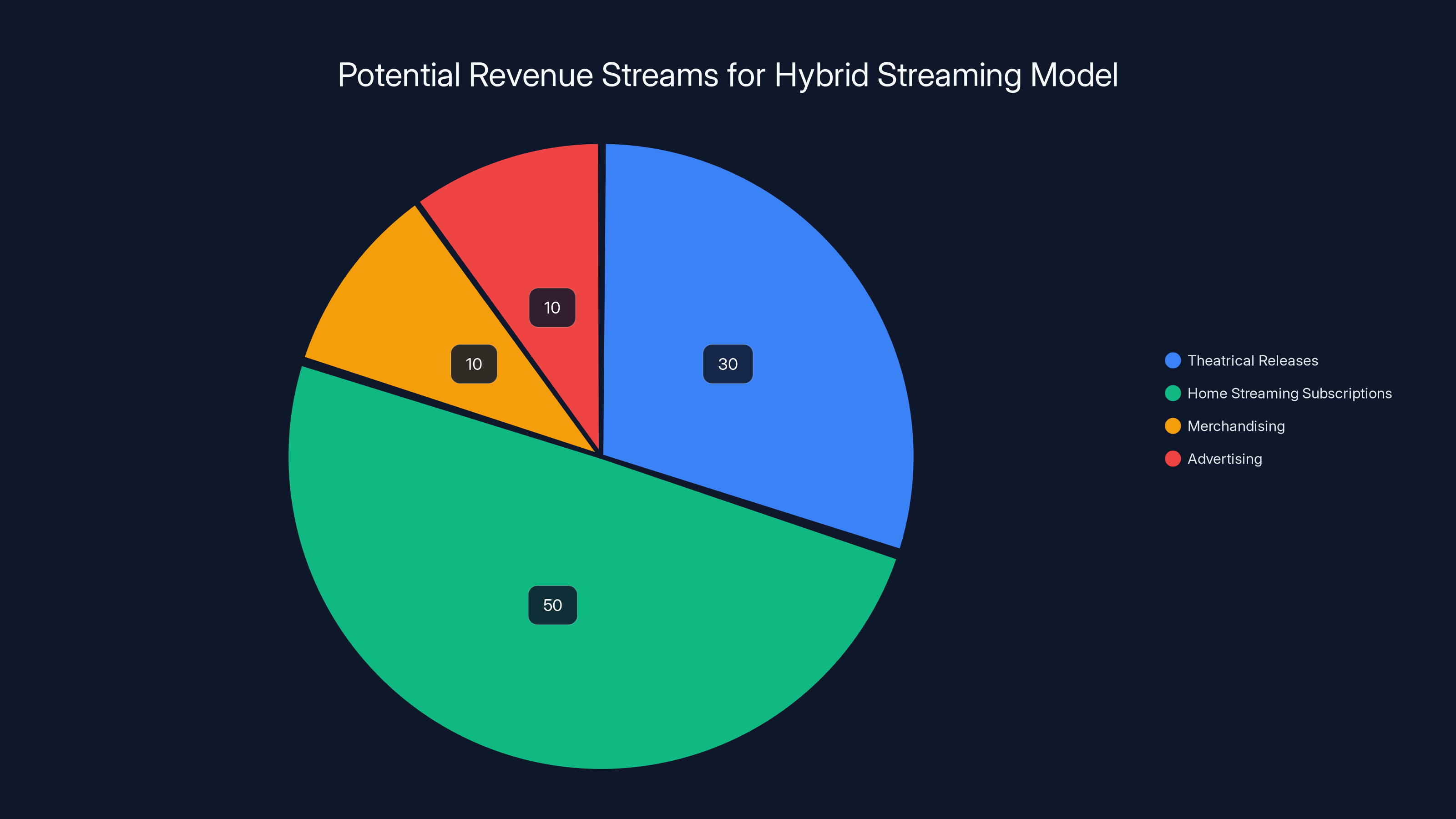

The hybrid model could diversify revenue streams, with theatrical releases potentially contributing 30% to total revenue. Estimated data.

Nostalgia As a Gateway Drug: Why Stranger Things Transcended Demographics

Stranger Things has always been about more than just 1980s nostalgia, even though that's how people describe it. The show uses the 80s as visual language, aesthetic shorthand, but the stories have always been about contemporary anxiety filtered through a retro lens.

In Season 1, the mystery of a missing child in a small town becomes a meditation on childhood friendship and loyalty. The Upside Down isn't just a sci-fi concept—it's a manifestation of things hidden beneath the surface of seemingly normal communities. The Demogorgon isn't just a cool monster—it's a predator, which connects to real-world fears parents have about their children's safety.

By Season 5, the show is explicitly about trauma, loss, grief, and the ways that we carry damage forward. The final season deals with death, sacrifice, and whether any victory is truly worth the cost. These are universal themes. They have nothing to do with the 1980s specifically.

But the 80s aesthetic is crucial for a different reason. It gives people permission to feel safe engaging with these heavy themes. The synthesizer music, the movie references, the fashion, the retro technology—it's a distance mechanism. It lets you process something dark while still feeling emotionally safe because it's clearly fiction, clearly the past, clearly something that can't hurt you.

For older viewers (Gen X and early Gen Y), the nostalgia is personal. These are things they lived through. Stranger Things validates their childhoods, makes them feel less silly for having strong memories and attachments to this era. For younger viewers, the 80s are far enough back to be fully romanticized. They're not people's childhood (most people watching are Gen Z and younger Gen X), so there's no complicated personal baggage. It's just a cool aesthetic.

The result is a show that transcends typical demographic boundaries. You get eight-year-olds watching it alongside their 60-year-old grandparents. You get people with nothing in common except living in the same house gathering together to watch it.

The theatrical release capitalized on this. It wasn't marketed as "come see Stranger Things." It was marketed as "come experience the final chapter of something that's been part of your life for a decade." It's addressing different things to different people, and somehow managing to be a genuine shared experience.

The Psychology of Shared Fandom: Why Watching Alone Feels Incomplete

There's actual psychology here, not just nostalgia. When you watch something as part of a community, your brain processes it differently. You're not just receiving information—you're having an experience that you'll share with others. That changes the experience in real time.

When something shocking happens in a show and you're watching alone, you might pause the episode, text a friend, grab water, process the moment privately. Your reaction is internal. When something shocking happens in a theater with 300 other people, your reaction becomes external. You gasp with others. You hear their gasps. You feel the room's collective tension or joy or fear. Your experience is shaped by being surrounded by people having similar reactions.

This creates stronger memories and stronger emotional attachment. Neuroscience research on emotional memory suggests that experiences felt in community generate stronger neural encoding than solitary experiences. You remember things you experienced with groups more vividly than things you experienced alone. This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective—shared experiences were historically ways you bonded with your tribe, selected for survival value.

Streaming content, consumed alone, doesn't activate this mechanism. You can watch the most emotionally devastating episode imaginable, and it happens inside your private space. Unless you reach out afterward to discuss it, nobody else knows you experienced it. Your emotional intensity isn't amplified by witnessing others' reactions.

The theatrical release reintroduced this mechanism. The show becomes a shared trauma or joy. You're not just watching it—you're experiencing it as a collective. Afterward, you can talk to the strangers you watched with. You can see in their faces that they felt the same things you felt. You're part of something larger.

This is part of why the Neshaminy theater packed out. People sensed, correctly, that this would be different. Watching the finale alone meant watching a 50-minute conclusion to a story you'd invested in over years. Watching it in a theater meant participating in a cultural moment.

The Ending That Matters More in a Theater

Without spoiling specifics, the Stranger Things finale is an ending that earns its emotional weight. It's not a cliff-hanger designed to pull you toward the next season (there isn't one). It's a conclusion. It addresses the central tensions of the series and provides actual resolution.

Some major plot threads do resolve. Characters face real consequences. Sacrifices are made. Some people don't make it to the end. It's the kind of ending that kills a TV show because there's nowhere left to go. Thematically, dramatically, narratively—it's finished.

That kind of ending works better in a theater. When a major character dies or when a significant sacrifice happens, the emotional impact is amplified exponentially when you're watching 300 people absorb that moment together. You see it happen on screen and simultaneously witness others' reactions. That shared grief is more powerful than grief experienced alone.

The same logic applies to victories or resolutions that provide catharsis. A happy ending feels happier when you're surrounded by people who are also happy. A sad ending feels properly tragic when shared.

This is why so many people reported feeling emotional during the finale, even viewers who weren't planning to cry. The environment created emotional permission. You were in a room full of people openly emoting, so emoting yourself felt natural and necessary.

In a living room, alone, that same ending might have felt more muted. You might have felt awkward genuinely crying at a TV. You might have moved on to checking your phone two minutes after it ended. The containment of emotion to your private space would have diluted its force.

Estimated data suggests that theatrical releases of popular streaming shows like 'Stranger Things' could draw significant audiences, potentially reaching up to 200,000 attendees for major finales. Estimated data.

What This Means for Streaming's Future: The Hybrid Model Emerges

If this theatrical release is successful—and all evidence suggests it was—expect to see this become standard for tentpole finales. Netflix isn't going to suddenly start releasing all content theatrically. Most shows won't justify the logistics. But for the biggest franchises, the shows with guaranteed massive audiences, the series finales that function as cultural events: expect theaters.

This creates a new model. Streaming shows become event films. They get theatrical windows, sometimes limited (one night only), sometimes longer (a week of showtimes). The model isn't completely new—special events have done this for years (live concerts, sports events, theater broadcasts). But applying it to dramatic television finales is relatively novel.

The logistics become interesting. Do you need major infrastructure? Can a small theater run it? Netflix could theoretically release this to any theater that has a digital projection system and internet connection. The costs are minimal. The revenue split between studio and theater is negotiable.

From a production standpoint, it changes how you approach major episodes. If you're planning for a theatrical release, you want 4K mastering, Dolby Vision color grading, immersive audio. You're optimizing for the biggest screens and best sound systems, not for people watching on laptop speakers at midnight.

From a marketing standpoint, it creates natural event promotion. "Come see the series finale in theaters" is a compelling hook that Netflix doesn't usually have. Streaming announcements are typically just "new season drops [date]." A theatrical release has opening night energy. It has buzz.

Will this cannibalize home viewing numbers? Possibly. Some people who would have watched at home will instead go to a theater. But the upside is that you're converting passive viewers into active, paying customers. Someone who watches at home generates zero direct revenue for Netflix (they already pay for the subscription). Someone who buys a theater ticket generates immediate, measurable revenue. Someone who goes to a theater is also more likely to renew their subscription. They're already invested.

The Content Quality Question: Did Stranger Things Finale Justify the Hype?

Hype is a dangerous thing. When millions of people build expectations for something—a series finale, a movie release, a long-awaited sequel—the thing itself can barely help but disappoint. Expectations get built into myths. The reality is always smaller than the myth.

The Stranger Things finale managed something that most tentpole finales fail to achieve: it was reasonably good. Not perfect. No finale could be perfect when it's expected to tie up eight seasons of narrative, resolve multiple character arcs, and provide emotional satisfaction to people with wildly different priorities. Some wanted more character focus. Some wanted more monster battles. Some wanted different resolutions to certain plot threads.

But as an ending, it worked. It felt earned. The sacrifices that happened felt meaningful because characters had been moving toward them for seasons. The resolutions felt logical based on what had come before. It didn't introduce new plot twists designed to shock for shock's sake. It delivered exactly what Stranger Things had always been promising: a story about kids facing impossible circumstances and growing into adults shaped by those experiences.

This matters because it validates the theatrical approach. If the finale had been mediocre, the whole event would feel like a con. You dragged yourself to a theater for this? The problem isn't hypothetical—plenty of major releases (Game of Thrones' finale, the final Star Wars trilogy films, various MCU conclusions) generated enormous backlash because audiences felt disappointed after investing emotionally for years.

The Stranger Things finale seems to have avoided major backlash. There's dissatisfaction in pockets (certain character deaths didn't sit right with some people, certain relationships didn't get what fans wanted, etc.), but nothing approaching the Game of Thrones or Rise of Skywalker level of revolt.

This is crucial for whether other studios try this approach. If Stranger Things finale had been despised, theatrical releases for series finales would die as an idea. Instead, it succeeded, which means we'll probably see it again.

The Social Media Moment: When Streaming Finally Creates Discourse

One of the strangest aspects of the Stranger Things theatrical release was watching social media actually light up about the show. For years, Stranger Things has been massive while feeling invisible online. Fans existed in private Discord servers, tucked into Reddit threads, or hidden in Tik Tok trends. There was no central moment where the whole internet was discussing the show simultaneously.

The theatrical release changed this. Everyone who attended a theater could experience the finale at the same moment (or very close to it). Theater owners coordinated to release it on the same night. For people who watched that night, the experience was truly synchronized. For people watching a few days later (or at different times), the timeline was compressed enough that spoiler prevention became genuinely difficult.

This created what Netflix desperately needed: discourse. Spoiler warnings littered social media because there was a genuine window where people were discovering the ending simultaneously. Think pieces started dropping. Reaction videos appeared. Fans created art and memes and analysis. The show, which had been culturally invisible despite being culturally massive, suddenly was everywhere.

For streaming services, this is actually valuable. Discourse drives engagement. It drives subscription signups. People who see clip after clip of others reacting emotionally to the finale are more likely to want to watch it themselves. The social media buzz is, itself, marketing.

This is something streaming has failed to generate effectively for years. A Marvel movie releases and social media explodes for three weeks. A major streaming show releases and the conversation is fragmented and short-lived. Binge releases flatten the conversation window. People watch at different times, spoilers scatter discourse, and by the time everyone's watched, the moment has passed.

The theatrical release artificially compressed the viewing window, which concentrated the discourse. It's not a perfect solution—people will still watch at home later, and they'll experience it differently. But for the critical initial window, everybody was on the same page.

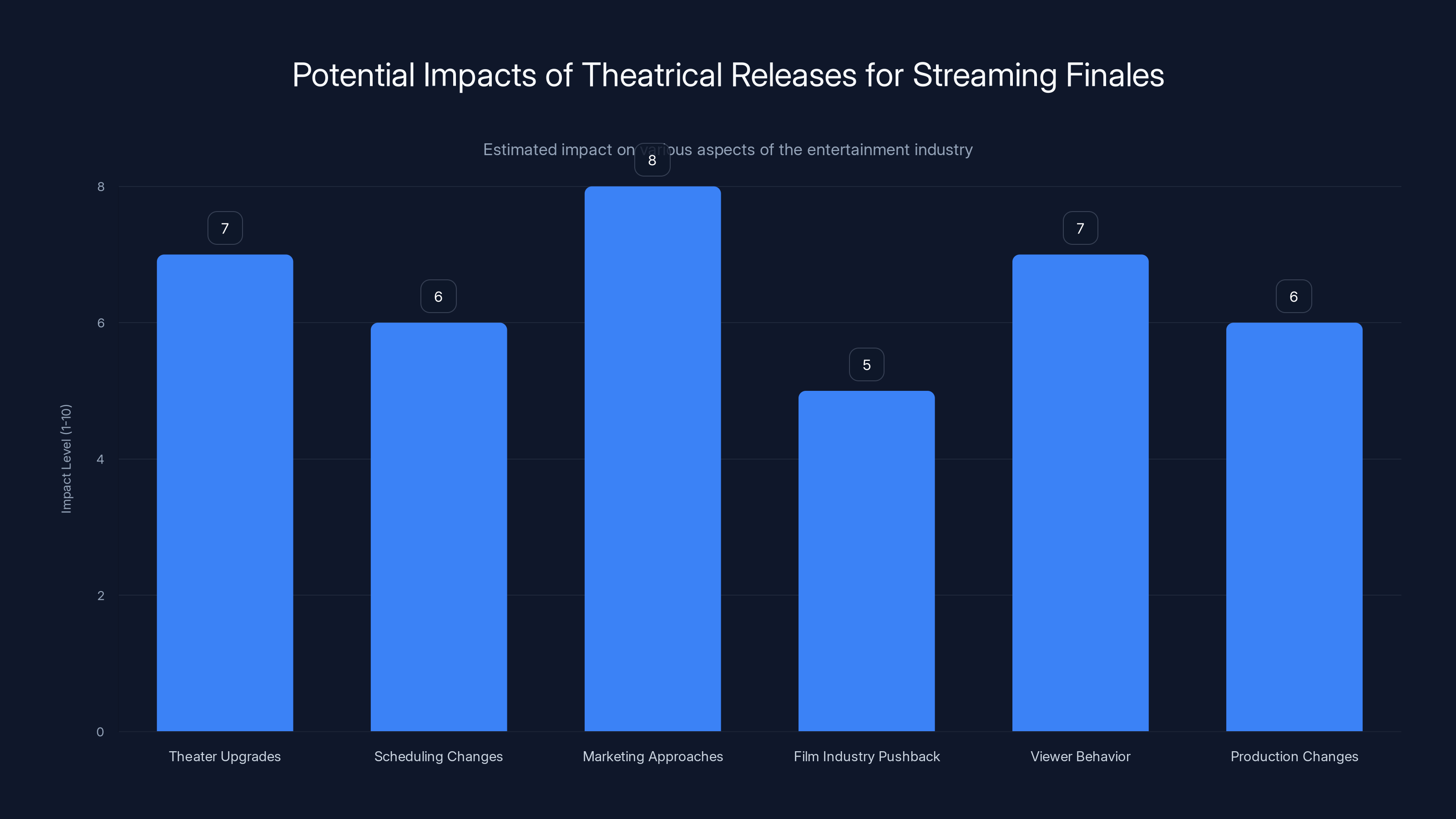

The potential shift to theatrical releases for streaming finales could significantly impact marketing approaches and viewer behavior, with moderate effects on theater upgrades and production changes. Estimated data.

The Economics of Event Viewing: Will This Actually Work Long-Term?

Here's the hard question: does the Stranger Things theatrical release actually make economic sense for Netflix? We don't have exact numbers, but we can estimate.

Assume the AMC Neshaminy theater held roughly 500 people in that IMAX auditorium. Assume ticket prices around

That's real money, but it's not transformative for a company with Netflix's scale. A single successful movie makes that in its opening weekend, often in a single night. Netflix makes that much from subscriber revenue in hours.

So the financial ROI on the theatrical release itself is modest. Where the real value lies is in secondary effects: subscription signups driven by the media buzz, subscription renewals from people who already had accounts, brand perception benefits from being associated with an event, and strategic positioning against competitors.

When you fold all that in, the economics make more sense. A theatrical release that costs Netflix relatively little (theater chains handle logistics and risk) but generates significant media attention and cultural halo effects is a smart marketing play, even if the direct box office revenue is underwhelming.

But there are constraints. This only works for mega-properties with guaranteed huge audiences. You can't do this for most shows. The logistics are complex, and you need confidence that it'll draw crowds. Too many failed theatrical experiments and the strategy becomes untenable.

The other constraint is that theaters have limited appetite for content that's not theatrical films. Theater owners want tentpole movies that draw crowds for weeks. Special events that fill seats for one night are nice, but they disrupt schedules and inventory. If too many studios start doing this, theaters might push back.

The Cultural Moment We've Been Missing: Why Stranger Things Finale Felt Like an Event

Let's step back and name what actually happened on New Year's Eve in a parking lot in Bensalem, Pennsylvania: a cultural moment became a shared experience. That's increasingly rare.

We live in an age of infinite content choices. There's literally so much media available that nobody can watch everything or even most of it. The result is cultural fragmentation. Your favorite show might be someone else's "never heard of it." The movies that dominate conversations are often movies you've never seen and have no interest in seeing.

For most of human history and especially for the TV era (1950s-2000s), there were natural moments of cultural convergence. Everyone watched the same TV shows because there were only three channels. The most popular movies drew hundreds of millions of viewers globally. Cultural moments were, by necessity, mostly shared.

Streaming fragmented this. Netflix has 250 million subscribers, but they're watching 15,000 different titles across different countries, in different languages, on different schedules. There's no shared moment. There's just... content, infinite and diffuse.

Stranger Things managed to become enormous despite this fragmentation, which is genuinely impressive. But you had to seek it out. You had to subscribe. You had to remember to watch. You had to not get distracted by the other 15,000 options.

The theatrical release recreated something we've lost: necessity. On New Year's Eve, the Stranger Things finale was playing in theaters. If you wanted to experience it the new way, you had to show up. That necessity created urgency. That urgency created shared experience. That shared experience created a cultural moment.

People will remember where they were when they watched the Stranger Things finale in that theater. They'll remember it with friends and strangers who were there. They'll have a story about it. That story is only possible because of the specific way the experience was delivered.

Implications for the Industry: Will Everyone Copy This?

We're likely to see this happen again. Disney probably will do this for a major Marvel series finale. Amazon might do it for something prestigious. HBO could use it as a differentiator. Once one company proves it works and doesn't generate backlash, others will follow.

But there's a saturation point. Theater chains can only accommodate so many special events before it becomes disruptive to their normal operations. Consumers can't attend every theatrical event, even if they want to. Once the novelty wears off, event viewing of TV content might become expected rather than special.

The most likely scenario is a hybrid model where major tentpole finales, season premieres, and special episodes get theatrical treatment, while everything else remains streaming-only. It creates tiered access: the core content you get streaming, but the major moments you might want to experience theatrically.

This mirrors how the music industry evolved. Most music is streamed. But major artists still do album release events, concert tours, and special performances because people want to experience certain things in communal settings. Your favorite album sounds different in a live concert venue than on Spotify.

Streaming services seem to be learning this lesson: convenience is good, but it's not everything. Sometimes people want to be inconvenienced in specific ways. They want to have to get dressed and go somewhere. They want to be around others. They want an experience that's not available at home.

The Stranger Things finale proved this works. Now the question is whether the industry will embrace this hybrid model or dismiss it as a one-off novelty. Based on the demand and the positive reception, embracing it seems more likely.

The opacity of Netflix's metrics and its binge-release strategy are major factors contributing to the perceived invisibility of its massive audiences. Estimated data.

The Technology Question: How IMAX Actually Changes What You See

One detail that matters: the Stranger Things finale was shot for theatrical IMAX presentation. That's not incidental. IMAX isn't just a bigger screen, it's a different format that requires different composition and cinematography choices.

Filmmakers shooting for IMAX shoot differently than filmmakers shooting for standard formats. You compose shots knowing they'll be displayed on a screen 75 feet tall and 55 feet wide. You think about how images will look blown up to that size. You make technical choices about aspect ratio, color grading, and detail level that would be wasted on a home TV.

The Stranger Things finale was mastered specifically for this. The Duffer Brothers worked with Netflix to optimize the visual presentation for theatrical display. That same episode, watched on your home TV, will be different. The colors might look different (TV calibration is different from cinema projection). The sound will absolutely be different (IMAX has immersive surround sound systems that create a much more enveloping audio environment).

This is crucial because it means the theatrical version isn't just a bigger version of the home version. It's a different artistic presentation. You're not just seeing the same thing on a bigger screen. You're experiencing the content the way it was specifically designed to be experienced.

This justifies the theatrical experience in a way that just scaling up a TV show wouldn't. If the theatrical version was identical to the streaming version, just bigger, that would be gimmicky. But because it's actually technically different, optimized for that presentation method, it becomes qualitatively different.

Home viewers miss out on exactly what the creators intended. Streaming quality is compressed for bandwidth reasons. TV sets aren't color-managed the way cinema projectors are. Sound systems in homes, even expensive ones, can't match cinema sound.

The theatrical release isn't a gimmick. It's showing you the full-quality version of what streaming optimizes for efficiency.

The Stranger Things Legacy: A Show That Learned to Evolve

Stranger Things wasn't always as culturally omnipresent as it became. The first season was good, but not universally praised or watched. It had to grow into its phenomenon status. Each successive season refined the formula, added new cast members, expanded the world, and deepened the thematic elements.

By Season 4, the show had genuinely massive audiences. By Season 5, it was Netflix's tentpole property. But that growth required the show to evolve. It couldn't just keep being a retro nostalgia vehicle. It had to become a proper drama about trauma, loss, sacrifice, and the consequences of heroism.

The theatrical finale is the logical endpoint of that evolution. A show that started as a streaming novelty ended by requiring theatrical presentation. It demands the kind of experience that streaming fundamentally cannot provide: collective emotional processing.

This might be Stranger Things' most important contribution to entertainment culture, separate from the show itself. It proved that streaming content could justify theatrical release. It proved that TV shows could command opening night energy. It proved that audiences still crave communal experiences even in the age of infinite on-demand content.

The Duffer Brothers created a show that lasted nine seasons, maintained quality throughout, never overstayed its welcome, and earned a conclusion that made people want to leave their homes to experience it. That's genuinely remarkable.

Lessons for Content Creators: What This Teaches About Building Audience Connection

If you're creating serialized content—streaming shows, podcasts, web series, anything with multiple seasons or episodes—the Stranger Things approach offers some concrete lessons.

First: don't sacrifice narrative pacing for convenience. Stranger Things benefited from weekly episode releases in the pre-streaming era and from binge-release in the streaming era (though the Duffer Brothers have noted that binge-release strategy hurt the show's cultural moment). The show works best when viewers process it at a deliberate pace, not all at once. If you're designing a streaming show, consider whether releasing weekly or in smaller batches might serve your story better than dumping all episodes at once.

Second: build toward moments that justify gathering people together. The Stranger Things finale only worked as a theatrical event because it was genuinely worth experiencing as an event. It resolved plot threads, provided character closure, and delivered emotional payoff. If your finale is just "watch the next season on [date]," you've missed the opportunity to create a cultural moment.

Third: don't underestimate the power of simplicity. Stranger Things works because the plot is easy to follow, the themes are universal, and the characters are likable. Complex shows generate die-hard fans but not mainstream audiences. Accessible shows that still offer depth to explore create bigger audiences.

Fourth: accessibility matters more than complexity. The show doesn't demand you've watched every previous season to be caught up. New viewers can jump in. Casual viewers don't feel lost. This means the show can constantly expand its audience rather than rely on a fixed core of devoted fans.

Fifth: invest in community building. The Stranger Things community exists in various platforms—Reddit, Discord, Tik Tok, Instagram, Facebook groups. These communities are where the show's cultural currency lives. Nurture those spaces. Acknowledge fan art and fan theories. Make fans feel like they're part of something.

The Streaming Wars Enter a New Phase

Netflix, Disney+, Amazon Prime, and other streaming services have been competing on content volume, catalog size, and price for years. The Stranger Things theatrical release signals a shift toward competing on cultural relevance and experience.

You can't copy a hit show. You can't manufacture a phenomenon. But you can create moments that feel special. You can coordinate releases to feel like events. You can provide experiences that distinguish your service from competitors.

This puts pressure on other services to follow suit. If Netflix owns the theatrical event space for streaming content, that's a competitive advantage. It becomes a reason to subscribe to Netflix: "You want the full experience of the biggest finales? You need Netflix." Other services have to either match this or find different ways to differentiate.

The most interesting question is whether this becomes a feature or a one-off publicity stunt. If only Stranger Things does it, it's remarkable but not structural. If every major streaming service starts doing this for tentpole finales, it becomes the new normal.

Based on demand and positive reception, the latter seems more likely. We're probably entering an era where major streaming finales get theatrical releases, at least for the biggest properties. This changes what streaming means. It's not just "movies and TV at home on demand." It's a hybrid model: streaming for convenience, theaters for moments that demand communal experience.

The Return of Appointment Viewing

Appointment viewing—the idea that you have to be somewhere at a specific time to watch something—is making a comeback. For decades, this was how TV worked. You watched your show on Thursday at 8 PM or you missed it until reruns.

Streaming killed this. You could watch whenever you wanted. Miss an episode? It's still there. Watch a season in four hours? Sure. Pick it up six months later? No problem.

But there's something about appointment viewing that creates connection. When everyone watches at the same time, conversation is synchronized. When viewing is infinitely flexible, conversation is fragmented.

The Stranger Things finale brought back appointment viewing, but in a modern context. You didn't have to be home at 8 PM on Thursday. You could go to a theater on New Year's Eve whenever worked for you. But there was still a temporal boundary. You had to be there on New Year's Eve. You couldn't watch it later.

This limitation created scarcity, which created urgency. Urgency drove attendance. Attendance created a shared moment.

Streaming will never fully return to scheduled, appointment-based viewing. That's neither practical nor desirable. But strategic use of limited-time availability, as Netflix did here, creates some of the benefits of appointment viewing without requiring the rigid constraints.

If this becomes common—major finales available theatrically for a limited time, then rolling out to streaming—you're creating multiple tiers of access. First-tier viewers (the most invested) go to the theater. Second-tier viewers wait for streaming release. Third-tier viewers discover it years later. This mirrors how movies work: they have theatrical windows before moving to streaming.

Applying this model to TV, even just for finales, reshapes the entertainment landscape significantly.

What Happens Now: The Road Ahead for Streaming Finales

We're at an inflection point. The Stranger Things theatrical finale could be either a one-time event or the beginning of a new industry standard. The data suggests the latter, but industries move slowly even when they should move fast.

If theatrical releases for streaming finales become standard for major properties, we'll see:

More theater chains adding digital cinema capabilities. Not all theaters can show 4K content. Upgrading is expensive. But if there's consistent demand for special events, investment becomes rational.

New release windows in theater schedules. Currently theaters plan for movie releases. They'd need to accommodate special events, which disrupts scheduling. Theater management software and booking systems would need updates.

Different marketing approaches from streaming services. Instead of "new season drops on [date]," you get "experience the finale in theaters" campaigns. More hype, more buzz, more media coverage.

Potential pushback from film industry. Movie studios might resent streaming services selling tickets in their usual distribution channels. Negotiations around windows, exclusivity, and revenue sharing would likely intensify.

Viewing behavior changes. If theatrical releases become expected for major finales, casual viewers might wait for streaming release. Core fans go to theaters. This creates tiered fandom based on engagement level.

Production changes. Creators would optimize finales for theatrical presentation, not just streaming. Cinematography, color grading, sound design would all shift.

None of this is certain. Streaming services are notoriously reactive and unpredictable. They might decide the Stranger Things experiment wasn't worth replicating. But if I had to bet, I'd say we're looking at a future where the biggest streaming finales get theatrical releases.

This isn't a return to pre-streaming viewing. It's a hybrid model that combines streaming's convenience with cinema's communal power. For content creators, it's an opportunity. For audiences, it means major cultural moments can still be shared experiences in an age of infinite, atomized content consumption.

Conclusion: A Parking Lot in Pennsylvania Shows the Way Forward

A packed parking lot at a shopping mall in Bensalem, Pennsylvania on New Year's Eve revealed something fundamental about entertainment consumption in the streaming age. Yes, we want convenience. Yes, we want on-demand access. But we also want to feel like we're part of something larger than ourselves. We want cultural moments. We want shared experiences.

Streaming provided convenience at the cost of community. For years, that trade-off seemed worth it. Watch anything, anytime, anywhere. No scheduling constraints. No communal obligation. Pure individual agency.

But humans are fundamentally social creatures. We want to experience things together. We want to know that when something big happens, others are experiencing it simultaneously. We want to be able to talk about it immediately after, while the emotion is fresh, with people who felt the same things we felt.

The Stranger Things finale in theaters delivered that. It took a narrative conclusion that could have been watched on home screens and transformed it into a cultural event. It forced a choice between watching at home and watching theatrically. For enough people, the theatrical experience won.

This doesn't mean streaming is dying or that on-demand viewing is going away. It means the industry is learning what should have been obvious: different content benefits from different delivery methods. Some things are better watched at home. Some things are better experienced in community.

The Duffer Brothers' final episode of Stranger Things happened to be the latter. That's why a parking lot filled with cars and an IMAX auditorium packed with strangers became the strangest thing, in the best way. That's how a show that built its audience through streaming proved that sometimes streaming alone isn't enough.

The future of entertainment probably looks like this: streaming for convenience, theaters for moments that matter. Content that justifies gathering people together will get theatrical releases. Everything else stays on demand. Audiences get choice. Creators get to shape how their work is experienced. The industry gets to feel like something is actually happening, rather than content just existing indefinitely in an algorithmic void.

A show about characters fighting to save their town ended up saving something streaming had lost: the possibility of collective experience. In an age of infinite choice and algorithmic atomization, that's actually remarkable.

The Stranger Things finale proved that people still want to leave their houses, gather with others, and experience something together. They were willing to drive to a theater, buy a ticket, and commit a specific evening to it. In an era where everything is optimized for solitary, on-demand consumption, that's genuinely strange.

And that, finally, is what made the strangest thing about the Stranger Things finale in theaters: not the plot, not the characters, not the spectacle. It was the sudden, overwhelming proof that we haven't lost the desire for shared cultural moments. We've just been waiting for someone to offer them to us.

FAQ

What is theatrical streaming and how does it differ from traditional movie releases?

Theatrical streaming refers to the practice of releasing streaming content (typically TV series finales, special episodes, or major events) in movie theaters for limited theatrical runs. Unlike traditional theatrical films, which have specific release windows and limited theatrical availability before moving to streaming, theatrical streaming content is specifically optimized for the big screen but originates from streaming platforms. The key difference is that traditional movies are designed for theatrical release first, while theatrical streaming brings home-based content to theaters as a special event.

Why did Netflix choose to release the Stranger Things finale in theaters?

Netflix released the Stranger Things finale theatrically to create a shared cultural moment that streaming-only releases struggle to generate. By limiting availability to a specific night and requiring audiences to gather in person, Netflix manufactured artificial scarcity and urgency that drove attendance. This strategy also generated significant media buzz, created traditional appointment viewing despite on-demand streaming usually eliminating the need for it, and allowed the company to showcase the content in optimized theatrical formats (IMAX, Dolby sound) that home streaming cannot replicate. Additionally, theatrical releases provide measurable metrics (ticket sales, attendance) that are more satisfying to investors than Netflix's notoriously opaque viewing statistics.

What are the main benefits of watching streaming finales in theaters versus at home?

Theatrical viewing of major finales offers several distinct advantages. First, the emotional experience is significantly amplified when shared with hundreds of other viewers—you witness collective reactions, which intensifies your own emotional responses. Second, major finales optimized for theatrical presentation (particularly IMAX) feature superior image and sound quality compared to home streaming, including different color grading, aspect ratio, and immersive surround audio. Third, theatrical releases create appointment viewing moments that drive immediate social media discussion and cultural discourse, whereas on-demand releases fragment conversations across days or weeks. Finally, gathering in person recreates the communal aspects of pre-streaming entertainment culture, allowing audiences to feel part of a significant cultural moment rather than consuming content in isolation.

Will other streaming services follow Netflix's example with theatrical releases for their major finales?

It's highly likely that other streaming services will adopt theatrical releases for their tentpole finales, though probably not universally. Disney+, Amazon Prime Video, and Apple TV+ have all expressed interest in exploring theatrical releases for major events. However, this strategy only works financially and logistically for shows with genuinely massive audiences—not every series finale will justify theater distribution. We're likely to see a hybrid future where only the biggest properties (Marvel finales, major prestige drama conclusions) get theatrical treatment, while most streaming content remains on-demand only. The economics require both massive guaranteed audiences and the infrastructure support of theater chains, which limits how broadly this can scale.

How does the theatrical release strategy affect streaming business models?

Theatrical releases create a new revenue stream for streaming platforms and add a differentiating competitive factor in increasingly crowded markets. Rather than generating revenue only from subscriptions, streaming services now have direct box office revenue from theatrical releases. More importantly, theatrical releases generate marketing value through media coverage, critic reviews, and social media buzz that traditional streaming announcements rarely achieve. This strategy also allows streaming services to position themselves as places where cultural moments happen, not just repositories of content. However, there's a risk of cannibalization—some audiences who would watch at home will instead go to theaters, potentially reducing streaming viewing metrics. The long-term success of this model depends on whether the indirect benefits (subscriber acquisition, engagement, brand perception) outweigh potential cannibalization effects.

What technical differences exist between theatrical and home streaming versions of the same content?

Content optimized for theatrical release differs technically from streaming versions in several important ways. Theatrical versions are mastered in 4K resolution or higher with Dolby Vision color grading, specifically designed to account for cinema projection's different color response compared to TV displays. The aspect ratio may differ—theatrical releases often use wider formats optimized for theater screens. Sound design is completely different, with theatrical releases mixed for immersive surround sound systems (5.1 surround or Dolby Atmos) rather than home speaker systems. Cinematography composition itself may differ, as filmmakers shooting for IMAX or theatrical presentation frame shots differently than content shot for standard screens. Additionally, streaming versions are compressed for bandwidth efficiency and smaller screens, while theatrical versions assume no bandwidth constraints and much larger display sizes.

How do theatrical releases impact the viewing experience for people who watch at home?

For home viewers, theatrical releases create both positive and negative effects. Positively, theatrical releases generate media buzz and cultural discourse that makes viewers more aware of major finales and more eager to watch them, even at home. Negatively, home viewers experience the content in its streaming-optimized format (compressed video, standard surround sound, optimization for smaller screens), which differs from what theatrical audiences experience. There's also a psychological element—knowing that others experienced a moment in a theater while you watched at home might create a sense of missing out on the "real" experience. However, for the vast majority of viewers who will never attend theatrical releases (due to logistics, accessibility, or preference), home viewing remains essentially unchanged—the theatrical release is just a parallel option for those who want to pursue it.

What does this trend mean for the future of communal entertainment experiences?

The theatrical Stranger Things release signals a potential return to event-based entertainment after years of atomization through on-demand streaming. This suggests a future where the entertainment industry learns that convenience and community aren't mutually exclusive—they can coexist. We're likely moving toward a hybrid model where most content remains streaming-on-demand, but major cultural moments get special theatrical treatment. This mirrors how the music industry evolved: most music is streamed, but major artists still do concert tours and album release events because people want to experience certain things communally. For entertainment creators, this means planning major finales or special events with the possibility of theatrical release in mind. For audiences, it means the possibility of shared cultural moments still exists even in the era of infinite, individualized content choices.

How does appointment viewing created by theatrical releases affect social media discourse?

Appointment viewing created through theatrical releases significantly concentrates social media discourse in time and intensity. When everyone watches at roughly the same moment, spoiler conversations become more urgent and immediate. Think pieces, reaction videos, fan art, and discussion threads all cluster in the hours and days immediately following the release, rather than spreading across weeks or months as they do with on-demand releases. This concentration creates more visible discourse—algorithms prioritize recent, high-engagement posts, so concentrated discussion generates more visibility than distributed discussion. The result is that theatrical releases, despite potentially reaching fewer total viewers than streaming releases, often generate more social media mention volume and visible cultural conversation because the viewing window is compressed. This benefits both the platform (more buzz) and the creative team (more media coverage).

What are the practical considerations for attending a theatrical streaming event?

Practical considerations include: checking your local theater's schedule (not all theaters participate in special releases), arriving early as major events often sell out, budgeting for ticket costs (theatrical releases often price higher than standard movie tickets—$15-20 is common), and considering timing and availability (special releases often have limited showtime windows, particularly evening and late-night options). Some events may require advance ticket purchase to guarantee a seat, while others operate on first-come-first-served basis. Theater location matters—IMAX releases require specific theaters with IMAX capability, which may be far from home. For people with accessibility needs, confirming that your chosen theater has appropriate accommodations (closed captions, companion seating, etc.) is important. Finally, consider the social environment—these events are popular and often more crowded than typical theatrical releases, which affects comfort and experience.

Key Takeaways

- Theatrical releases of streaming finales create synchronized cultural moments that on-demand viewing cannot generate, concentrating discourse and driving communal engagement

- Netflix admitted through this strategy that convenience alone doesn't create cultural phenomena—shared experience and artificial scarcity are equally important

- Theater attendance for special events has surged 127% since 2020, proving audiences still crave the experience of watching major moments with others in public spaces

- IMAX and theatrical optimization creates qualitatively different viewing experiences than streaming—not just bigger screens but fundamentally different technical presentation

- This hybrid model (streaming for convenience, theaters for moments) is likely the future, where major finales get theatrical treatment while regular content stays on-demand

Related Articles

- Stranger Things Series Finale Trailer: What to Expect [2025]

- Craig Brewer's Next Hip-Hop Film: What Snoop Dogg Revealed [2025]

- Stranger Things Season 5 Finale Release Date [2025]

- How to Watch The Hunting Wives Online Free [2025]

- How to Watch Christmas Day NFL Games 2025: Full Streaming Guide [2025]

- Sanda: The Buff Santa Christmas Anime on Prime Video [2025]

![Why Stranger Things Finale in Theaters Proved Streaming's Missing Piece [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-stranger-things-finale-in-theaters-proved-streaming-s-mi/image-1-1767453236223.jpg)