Why the Electrical Grid Needs Software Right Now

Picture this: it's July in Texas, the grid is stressed to the breaking point, and your air conditioner cuts off for three hours. Your neighbor loses his internet connection during a critical work call. Downtown, a hospital runs on backup generators. None of this happens because there's not enough power. It happens because software isn't smart enough to find and use the power that already exists.

That's the uncomfortable truth about the electrical grid in 2025. We're not facing a simple capacity problem. We're facing a coordination problem. And coordination problems get solved with software.

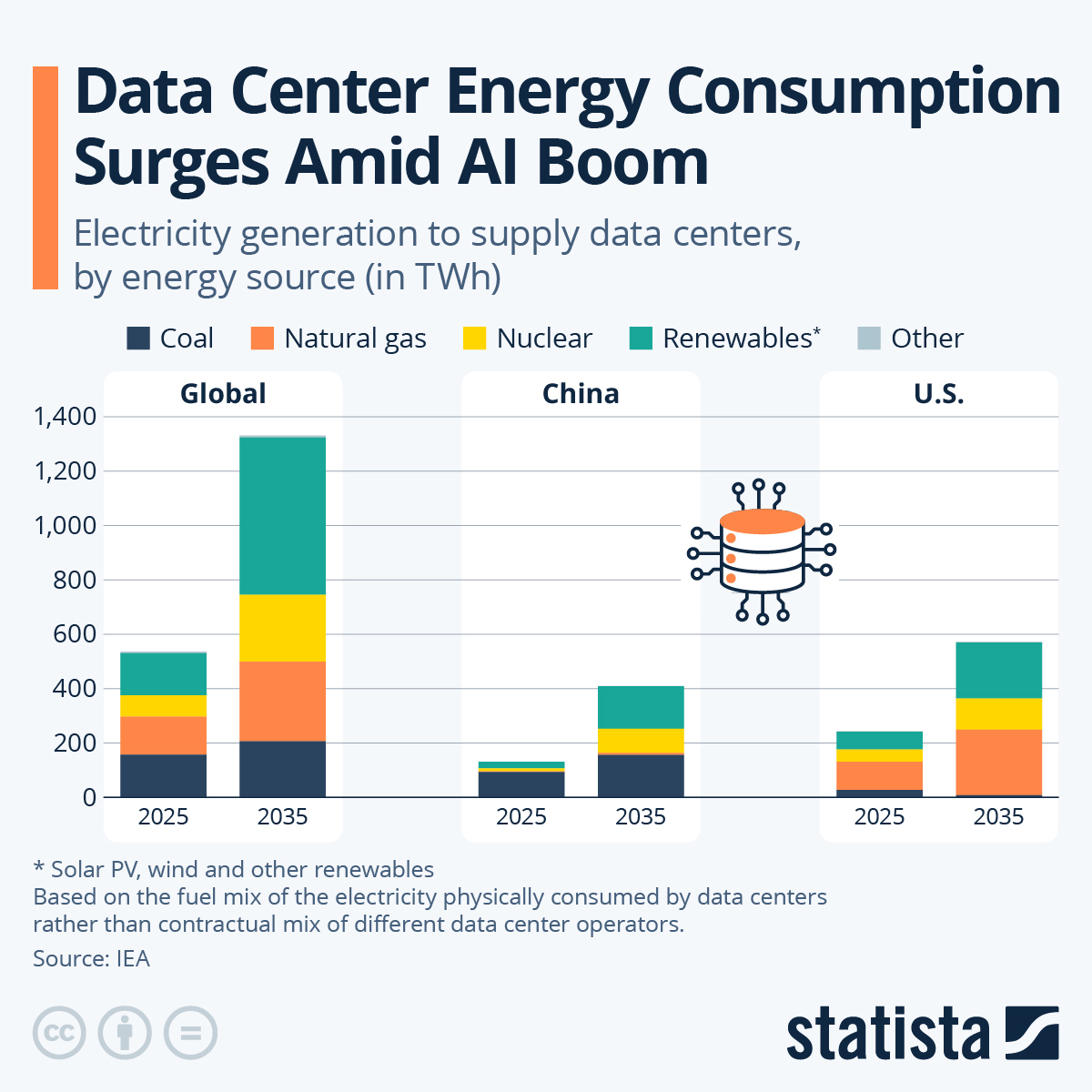

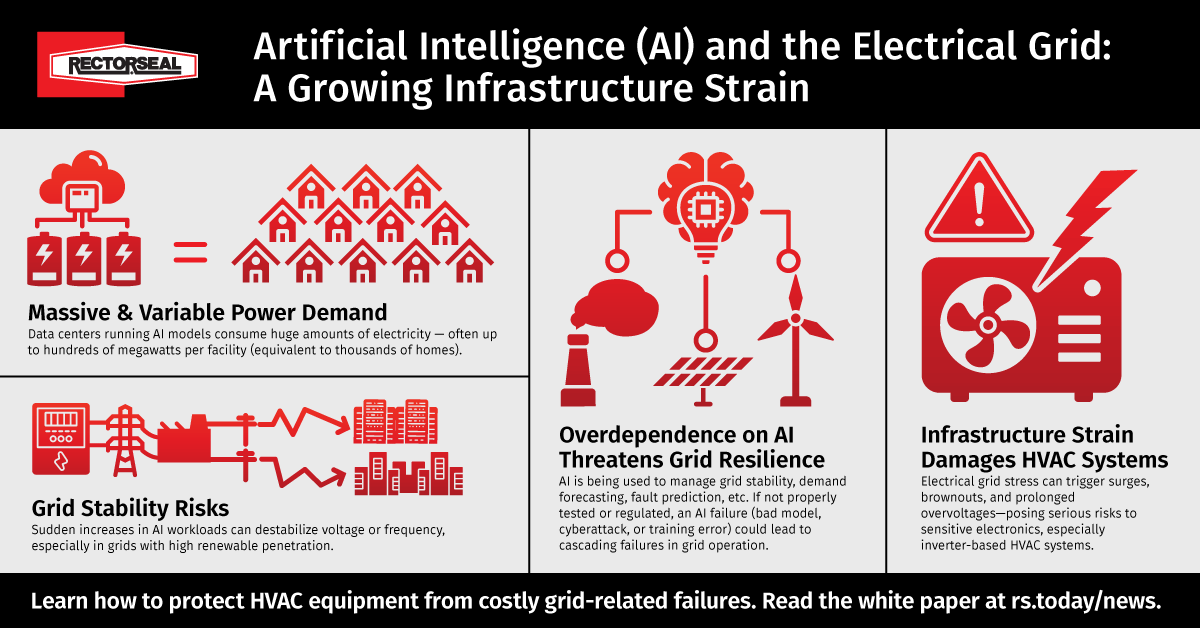

Electricity rates jumped 13% this year, driven almost entirely by data center demand. But here's the kicker: the grid isn't just straining under current load. It's about to get hit with a wave of new demand that will make 2025 look quaint. Data centers will triple their electricity consumption in the next decade. Meanwhile, everyone's buying electric vehicles. Industries are electrifying heating systems. And artificial intelligence is consuming more power with every new model released.

Utilities are scrambling. They're planning expensive new power plants. They're upgrading transmission lines at massive cost. They're lobbying for regulatory changes. But they're missing something obvious: there's already software sitting on the shelf that can squeeze 15% to 25% more capacity out of what they have.

This isn't science fiction. Companies like Gridcare, Yottar, Base Power, and Terralayr are already doing it. And 2026 could be the year when software stops being a nice-to-have and becomes essential infrastructure.

Let me walk you through why.

The Grid's Hidden Problem: Coordination, Not Capacity

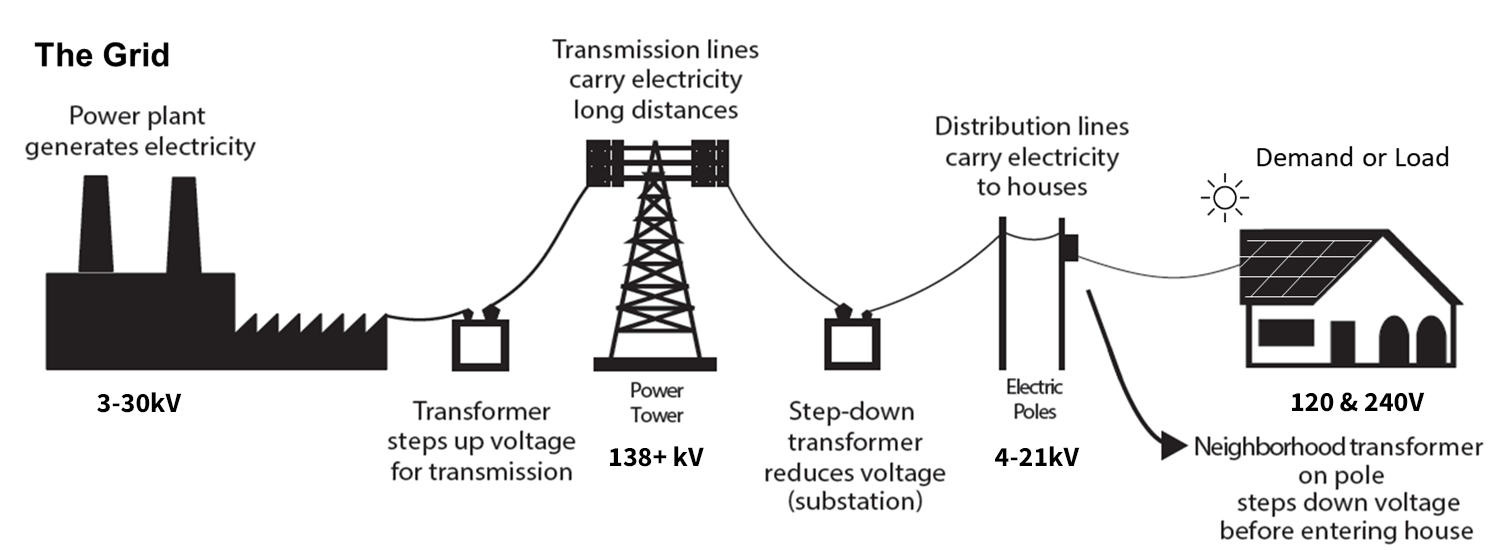

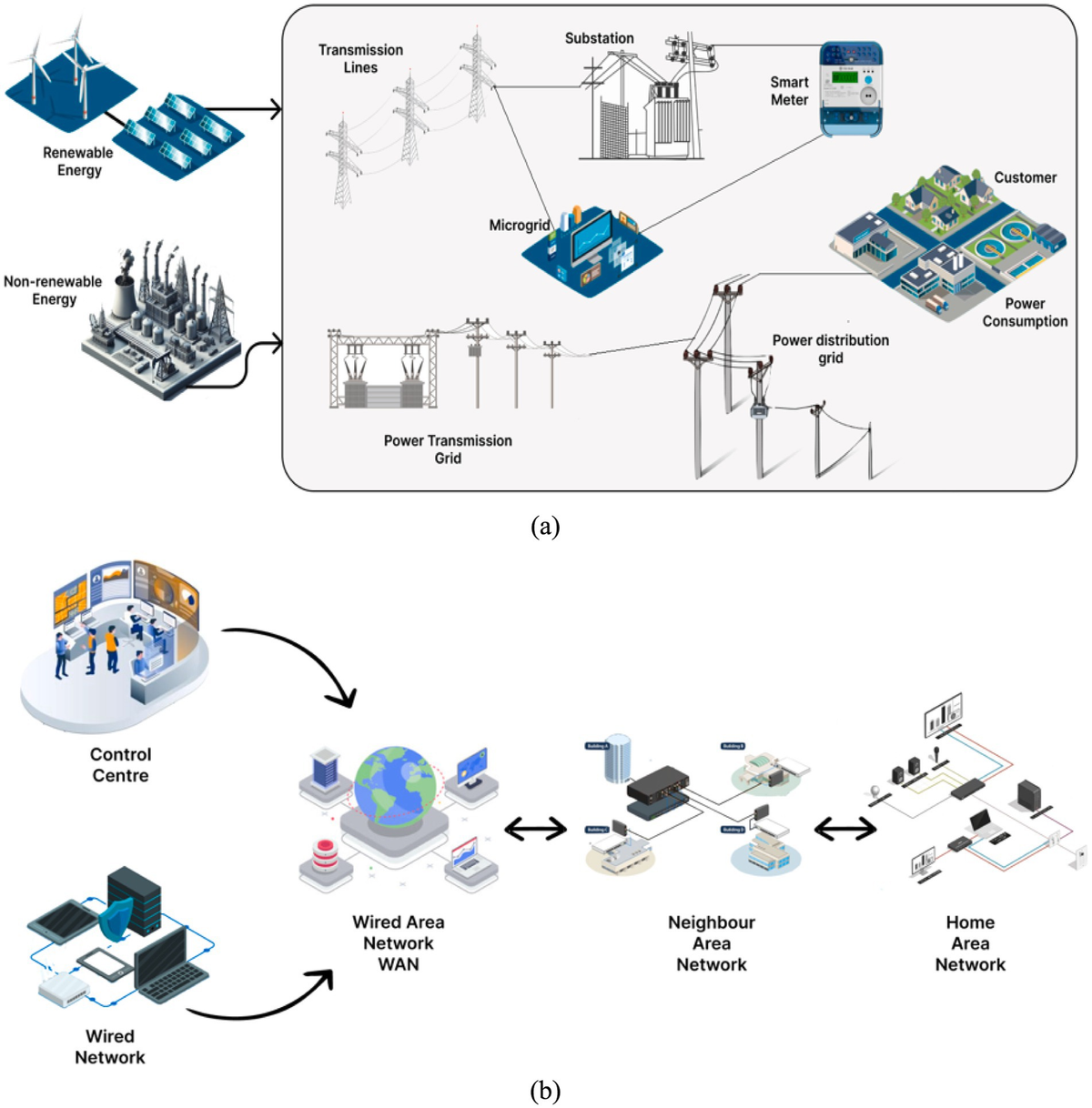

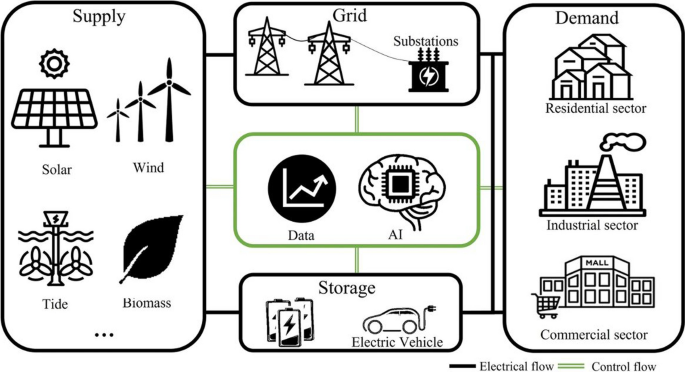

Most people think the electrical grid is struggling because we don't generate enough power. That's partially true. But the real bottleneck is coordination. The grid works like a massive, real-time puzzle. Power needs to flow from where it's generated to where it's consumed, instantly, with zero margin for error. If supply drops even slightly below demand, the whole system becomes unstable.

For decades, this puzzle had predictable pieces. Coal plants hummed along 24/7. Nuclear plants provided steady baseload power. When demand spiked on a hot summer afternoon, utilities fired up natural gas plants. It wasn't elegant, but it was manageable.

Then everything got messy. Solar panels generate power at noon but not at night. Wind turbines produce when the wind blows, not when the grid needs them. Batteries store energy but have fixed capacity and degradation rates. Data centers demand consistent, massive amounts of power at unpredictable times (a new model rollout can double their power draw overnight). Electric vehicles charge on random schedules. Communities rotate brownout and rolling blackout schedules based on historical patterns that no longer apply.

The grid is now trying to solve a real-time optimization problem with 1960s-era tools. Utility companies still use spreadsheets and heuristics to manage distribution. They rely on demand forecasts that assume last year's behavior predicts this year's consumption. They make decisions based on incomplete information about available capacity because they've never had a unified view of the entire network.

This is where software comes in. Software can see the entire grid simultaneously. It can predict demand with machine learning models. It can identify available capacity in real time. It can coordinate assets—batteries, solar arrays, wind turbines, data centers—to optimize consumption and generation. It can make thousands of micro-decisions per second to keep the system balanced.

The grid doesn't need more power plants. It needs better coordination of the power plants it has.

Data centers are projected to increase their electricity consumption from 17% in 2024 to 35% by 2035, indicating a significant rise in energy demand driven by AI and tech giants.

The Data Center Tsunami: 13% Growth Isn't the End of the Story

Let's be specific about what's driving this crisis. Data centers used 17% of all U.S. electricity in 2024. By 2035, that number will hit 35%. That's not a projection, that's a forecast. And it's probably conservative.

Why? Because AI companies are building data centers at a pace that's actually unprecedented. Not historically unprecedented. Unprecedented by modern corporate standards. Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Meta have collectively announced over $200 billion in data center spending. That's not a rounding error. That's the third-largest economy in the world, by itself.

And these aren't normal data centers. AI training clusters need consistent, uninterrupted power. A GPU failure in one rack cascades through the entire training job. Power fluctuations cause bit errors that corrupt weeks of computation. For these facilities, power quality matters as much as quantity.

Everyone understands this intellectually. What they're missing is the magnitude. A modern training cluster for a state-of-the-art language model will consume 100 megawatts continuously. For reference, that's more power than a city of 100,000 people. OpenAI's training clusters consume about as much electricity as the entire country of Morocco. And they're building more.

Utilities look at this and panic. They see a multi-year lag between deciding to build a new power plant and actually generating power from it. They see regulatory hurdles, environmental concerns, local opposition, financing challenges, and construction delays. A natural gas plant takes 2 to 3 years. A nuclear plant takes 10 to 15 years. These companies need massive new generation capacity within 18 months.

That's the gap that software fills. You can't build a power plant in 18 months. You can't even begin the permitting process. But you can deploy software that finds spare capacity, coordinates usage, shifts load to times when supply is abundant, and aggregates small resources into large ones. You can do that in weeks.

Building a power plant is significantly more expensive and time-consuming compared to deploying grid optimization software. Estimated data.

How Software Finds Hidden Capacity: The Gridcare Approach

Gridcare is doing something that sounds simple until you realize how much data it requires. They're mapping the electrical grid at a granular level, identifying which transmission and distribution lines have spare capacity, and matching that capacity to the needs of potential data center operators.

This shouldn't be hard. The utility companies should have this data. They do, technically. But it's scattered across dozens of incompatible systems built over 40 years. Some data is still on paper. Some is in databases that don't talk to each other. Some is classified as confidential because it relates to grid security. No utility has a unified picture of where their spare capacity actually is.

Gridcare built that picture. They gathered transmission and distribution data, cross-referenced it with fiber optic location information (because data centers need redundant network connections, not just power), layered in extreme weather patterns (because line capacity changes with temperature and humidity), and added community sentiment data (because new data centers face local opposition). They built a model that says: "A data center operator needs 50 megawatts in the Southeast. Here are the ten locations where the grid can handle that load without upgrades."

Utilities claim these locations don't exist. Gridcare has found them. They've already identified several sites that utilities overlooked, which means there's probably more. How much? Conservative estimates suggest 15% to 20% of available capacity is invisible to current utility planning processes.

That's astonishing. That means the grid has somewhere between 10 and 15 gigawatts of spare capacity that utilities don't know how to use. That's equivalent to 10 to 15 new coal plants. Nobody needs to build new power generation. They just need software to see what they already have.

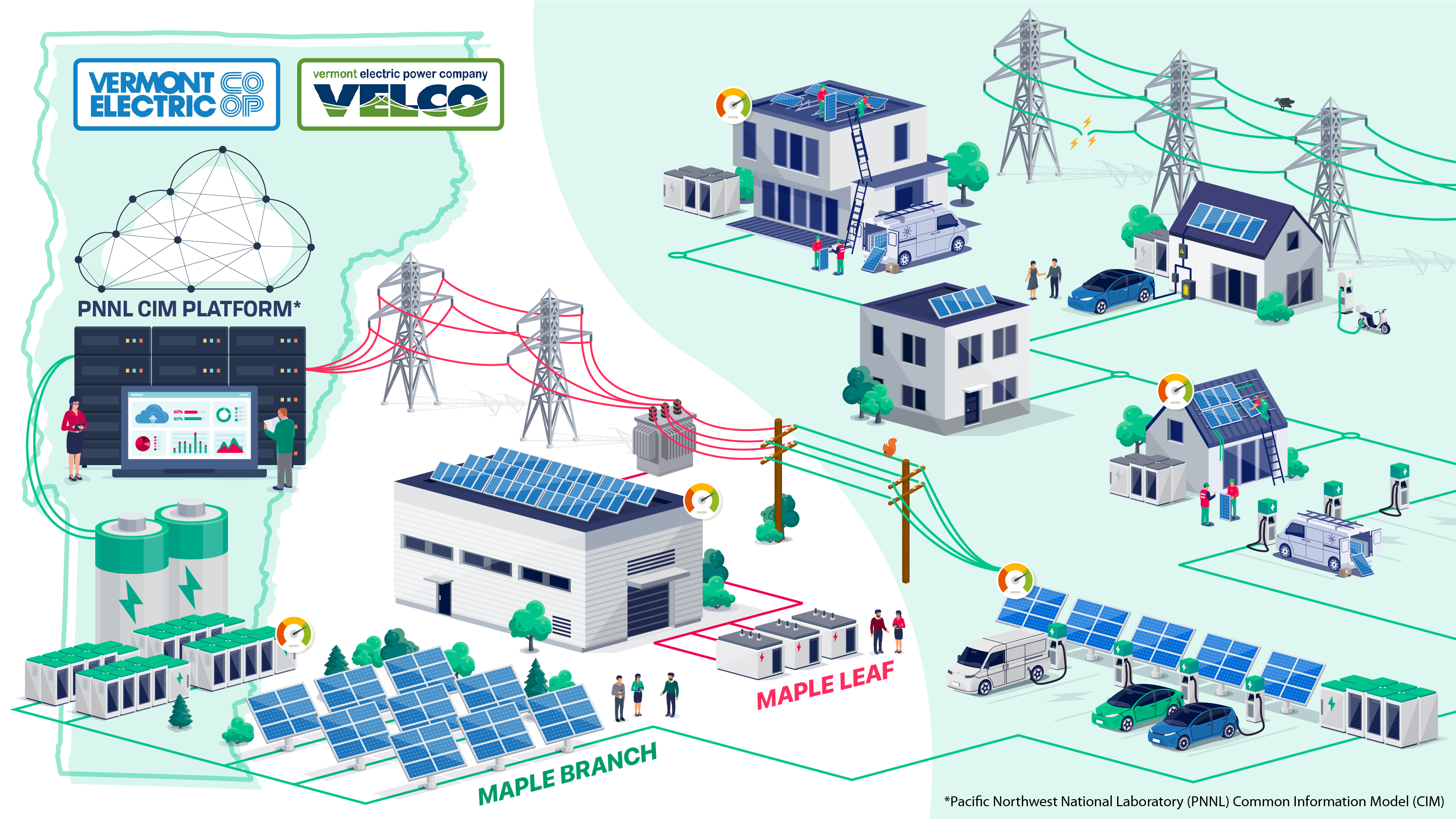

Virtual Power Plants: Turning Distributed Assets Into Coordinated Resources

Here's another angle. The grid doesn't need every power source to be gigantic. It needs all the small sources to act like one giant source.

Imagine 10,000 homes with solar panels and battery systems. Individually, they're worthless for grid operations. A single home's battery might have 5 to 10 kilowatt-hours of storage. The grid operates in megawatts (1,000 kilowatts per megawatt). But what if you coordinated all 10,000 homes so their batteries discharged simultaneously? Now you've got 50 to 100 megawatt-hours of coordinated power. That's useful. That's a power plant that exists only in software.

Base Power is building exactly this in Texas. They lease batteries to homeowners at low cost. Homeowners get backup power during outages. Base Power gets an asset they can dispatch to the grid during peak demand. The homeowner wins because they get cheap battery backup. The grid wins because it gets flexible capacity. Base Power wins because they control thousands of megawatt-hours of distributed storage.

The magic is in the software. The hardware—the batteries—existed before. What didn't exist was a system to coordinate their discharge, predict when they'd be needed, optimize when to charge them (ideally during times of abundant, cheap power), and communicate with the grid in real time. That's pure software.

Terralayr is doing something similar in Germany, except they're not selling batteries. They're aggregating batteries that already exist on the grid—home systems, commercial systems, industrial systems—and coordinating them. The batteries had no coordinated value before. Now they do. The grid gets virtual power plants that scale up and down in seconds.

Let's put numbers on this. A distributed battery system can respond to grid conditions 10 to 100 times faster than a conventional power plant. It can ramp power up or down in milliseconds. It can provide services—frequency support, voltage regulation, reactive power—that conventional plants can't touch. Software is turning residential batteries into grid-stabilizing infrastructure.

Building a new power plant costs significantly more and takes longer than deploying grid optimization software. Software offers a faster ROI and greater flexibility.

Orchestrating Renewables: The Missing Piece

Renewables are wonderful. Solar and wind are increasingly cheap. They've driven electricity costs down in many markets. They've reduced carbon emissions. They're the future.

They're also chaos from a grid operations perspective.

Solar generates power when it's sunny. Wind generates power when it's windy. Neither correlates with when people need electricity. On a hot, still evening (when everyone's running air conditioning and the sun is setting), solar generation drops to zero and wind might be minimal. This is called the "duck curve"—demand stays flat, but supply drops off a cliff. The grid has to instantly switch from renewable sources to conventional sources. If it's not ready, the grid becomes unstable.

Or consider the opposite problem. A spring day with abundant sun and strong winds might push renewable generation so high that there's nowhere for the power to go. Utilities literally have to turn off renewable generators to keep the grid stable. It's called "curtailment." In 2024, about 7% of available wind and solar power was wasted because the grid couldn't use it.

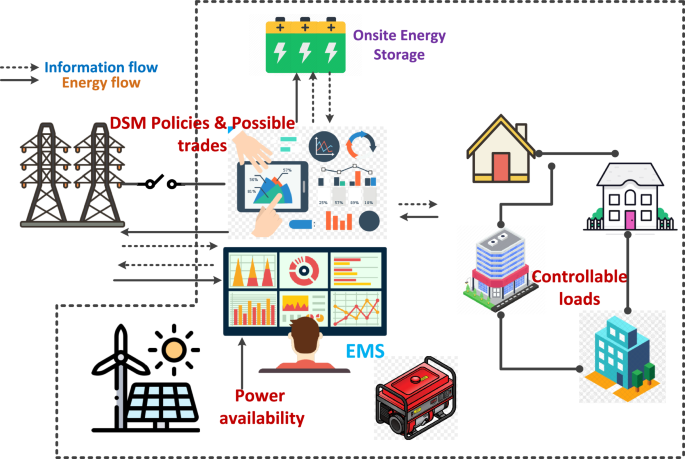

Software is solving this. Companies like Texture, Uplight, and Camus are building systems that coordinate renewable assets with storage and demand. The idea is to match supply and demand in real time.

Here's how it works at scale: A software system looks at the solar forecast for the next 24 hours. It knows the wind forecast. It knows the building load forecast. It knows the battery state. It knows when electric vehicle charging is likely to happen. Based on all this, it makes a plan that minimizes grid stress. If solar is abundant, charge the batteries during peak solar hours and use that stored power during peak demand hours. If wind is strong at night, shift industrial loads (that can be flexible) to nighttime hours. If it's going to be hot tomorrow, pre-cool buildings during early morning when demand is low.

None of this requires new hardware. All of it requires better software. And the coordination value is enormous. Early implementations show 12% to 20% reduction in peak demand, which means utilities need less capacity to handle the same load.

Smart Load Shifting: Making Demand Follow Supply

Traditionally, the grid operates on a simple principle: adjust supply to meet demand. This works when supply is centralized and predictable. It breaks down when supply is distributed and intermittent.

The inverse approach is demand flexibility: adjust demand to match supply. This is just becoming possible at scale.

Consider data centers. Most assume they need consistent, uninterrupted power. What if they could be flexible? What if AI training jobs could be optimized to run more heavily during hours of cheap, abundant power? What if batch processing jobs shifted to nighttime hours when demand is lower and renewable generation is more stable?

This requires software that understands the economics of power usage and builds optimization into job scheduling. A company might save 15% to 20% on electricity costs by running non-critical jobs during off-peak hours. The grid saves enormous capacity because demand becomes smoother and more predictable.

Same principle applies to EVs. Most people charge their cars whenever they plug them in. What if the grid could incentivize charging during specific hours? If electricity costs 5 cents per kilowatt-hour at 2 AM and 15 cents per kilowatt-hour at 6 PM, people charging at off-peak hours would save 60% on charging costs. The grid avoids needing peak generation capacity. Utilities reduce the marginal cost of serving all customers.

Software enables all of this. It can forecast demand. It can adjust prices dynamically. It can coordinate when millions of devices consume power. It can optimize based on individual customer preferences and grid needs. And it's not theoretical—early implementations in Germany, Denmark, and California show 10% to 25% demand reduction during peak hours when smart load shifting is deployed.

In 2024, approximately 7% of available wind and solar power was curtailed due to grid limitations, highlighting the need for better orchestration systems.

The Modernization Challenge: Why Legacy Grid Software Is Failing

Here's what most people don't understand: the utility industry is running on outdated software. Not outdated like "a few years old." Outdated like "designed for a different century."

The power grid control systems at most utilities were built in the 1970s and 1980s. They've been updated, but the underlying architecture is the same. These systems can monitor generation and transmission in real time, but they operate based on limited information and simple heuristics. They don't use machine learning. They don't integrate data from distributed sources. They don't optimize across the entire network simultaneously.

Why? Because that wasn't necessary when the grid was simple. When supply came from a handful of big plants and demand was predictable, simple rules worked fine. When the grid was mostly passive (power flowed in one direction from plants to consumers), you didn't need sophisticated coordination.

Now you do. The grid has become active. Power flows both directions. Supply is distributed. Demand is flexible. The system has millions of controllable devices. You need software that understands the entire network, optimizes across thousands of variables in real time, and learns from patterns in the data.

Nvidia and EPRI (the Electric Power Research Institute) are partnering on this. They're building AI models specifically for grid operations. Google is working with PJM Interconnection (a regional transmission organization serving 65 million people) to deploy AI systems that process the backlog of connection requests from new power sources.

These are big moves. They signal that modernizing grid software is becoming a top priority. And they're working. Early deployments show 8% to 12% improvements in grid efficiency, which translates to massive economic value.

Why Utilities Are Slow to Move: The Reliability Problem

You'd think utilities would be lining up to deploy this software. Lower costs, better efficiency, less capacity stress, happier customers. What's not to like?

Reliability.

The electrical grid is maybe the most critical piece of infrastructure in the modern world. Hospitals depend on it. Data centers depend on it. Financial systems depend on it. Your home depends on it. If the grid fails, society doesn't just get inconvenienced—it breaks.

Utilities take this responsibility seriously. And they should. But it makes them conservative about software changes. Deploying new software on the grid carries genuine risk. A software bug could cause a cascading failure that blacks out a region. An attacker could exploit vulnerabilities to disrupt the grid. A poorly tuned AI model could make optimization decisions that destabilize the system.

For traditional infrastructure companies, the solution is simple: don't deploy new software. Stick with what works. The software might be old, but it's proven. It's thoroughly tested. Its failure modes are understood.

But that solution no longer works. The grid is changing faster than utilities can manage with legacy software. The choices aren't "new software" versus "no software." The choices are "new software deployed carefully with extensive testing" versus "grid failures because the system can't handle current demands."

This is creating an opportunity for startups. They're building software specifically designed to work within utility constraints. They're emphasizing safety, redundancy, and verification. They're working with utilities to test extensively before deployment. They're doing the hard work of building reliability into new systems.

And it's starting to work. Utilities that were reflexively opposed to software changes are beginning to adopt them. The demand is too great. The risk of not adapting is becoming higher than the risk of adapting.

Smart load shifting can lead to significant cost savings: data centers can save an estimated 15-20%, while EV charging can save up to 60% by shifting to off-peak hours. (Estimated data)

The Economics of Software vs. Infrastructure

Let's talk money, because that's ultimately what decides which approach wins.

Building a new natural gas power plant costs

Deploying software to optimize the existing grid costs

The ROI math is straightforward. Software that enables you to squeeze 20% more capacity out of the existing grid saves you

Moreover, software is flexible. If demand trends change, you can update software. If you need different optimization priorities, you can reprogram the system. If a new technology becomes available, you can integrate it. A power plant is rigid. Once it's built, it's built. The only flexibility is whether you run it or shut it down.

Utilities are beginning to understand this. The math is undeniable. Software is cheaper, faster, and more flexible than building new infrastructure. The constraint isn't economics. It's reliability and integration complexity.

Aggregators and Virtual Power Plants: The Future Model

Here's where the grid is heading. Instead of utilities controlling a handful of big generation resources, they'll coordinate millions of small resources. Instead of dumb, passive consumers, they'll work with smart, flexible loads. Instead of binary "on or off" assets, they'll have resources that can modulate power output in real time.

This model requires a different kind of company. Not traditional utilities, though utilities will participate. Not just software companies, though software is essential. Instead, "aggregators"—companies that coordinate distributed resources and serve as intermediaries between asset owners and the grid.

Base Power is an example. They own batteries distributed across Texas. Terralayr owns a portfolio of battery assets across Germany. These companies are not traditional utilities, but they're solving grid problems. They're providing services that the grid actually needs: flexible capacity that can ramp up and down quickly, storage that absorbs excess power, and demand modulation.

This creates new economics. An asset owner might earn 30% to 50% more return on their battery investment if it's coordinated through an aggregator than if it's isolated. The aggregator makes money by optimizing the portfolio. The grid gets flexible capacity. Everyone wins.

The software is what makes this work. You can't coordinate thousands of distributed batteries with manual processes. You can't predict their aggregate capacity without machine learning models. You can't optimize their dispatch without real-time algorithms. The entire value chain depends on software.

This is going to be massive. There's probably $100+ billion in value creation opportunity here as the grid transitions from a centralized generation model to a distributed aggregation model.

Battery asset owners can earn 30% to 50% more return when coordinated through an aggregator, highlighting the economic advantage of this model. Estimated data.

Integration Challenges: Making Heterogeneous Systems Work Together

There's a reason utilities are slow to adopt new technologies. Their systems are complicated. Extremely complicated.

A utility operates generation facilities. It owns transmission lines. It owns distribution infrastructure. It works with independent generators (solar and wind farms). It coordinates with other utilities. It integrates with customer systems (smart meters, EV chargers, home batteries). It works with regulators, stakeholders, environmental groups, and communities.

All of these systems have different software. Different data formats. Different communication protocols. Different update cycles. Integrating new software means making it compatible with this entire ecosystem.

A battery aggregator doesn't just need to optimize batteries. It needs to communicate with utilities. It needs to bid into wholesale electricity markets. It needs to comply with grid regulations. It needs to integrate with customer apps so homeowners can monitor their systems. It needs to handle payments and settlements.

This is genuinely hard. It's not just a technical problem. It's a coordination problem. A business problem. A regulatory problem.

Companies that solve this well will win. Companies that try to build standalone solutions will fail. The startups that are succeeding—Gridcare, Yottar, Base Power—aren't building software that works in isolation. They're building systems that integrate with utility operations, respect regulatory constraints, and create value for all stakeholders.

The Regulatory Landscape: Why Rules Matter

One thing that surprised me was how much regulation matters here. In electricity markets, software deployment isn't just a technical decision. It's a regulatory decision.

Take frequency regulation. The grid operates at 60 Hz in North America. When demand exceeds supply, frequency drops below 60 Hz, which can damage equipment and destabilize the grid. When supply exceeds demand, frequency rises above 60 Hz. The grid operator needs to constantly adjust generation to maintain frequency at exactly 60 Hz.

This has traditionally been done by conventional power plants that can quickly ramp output up or down. The operator calls them, tells them to increase output, and they do. But there's a lag—it takes time for the power plant operator to react.

Now, a battery system with good software can adjust output in milliseconds. It's dramatically faster. So shouldn't utilities use batteries instead of power plants for frequency regulation?

They should. But there's a problem. The market for frequency regulation was designed assuming power plant operators. The rules specify response times that batteries already beat, but they don't account for the economic model of battery operators. The payment structure doesn't make sense for batteries.

So regulators have to write new rules. That takes time. Lots of time. Usually years. And while regulators are writing new rules, the existing rules prevent utilities from deploying the most efficient solutions.

This is gradually changing. FERC (the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission) and regional transmission organizations are updating rules to allow new technologies. But the pace is slow. And it's different in every state and every regional market.

For startups, this creates challenges and opportunities. The challenges are obvious—slower deployment, regulatory uncertainty. The opportunities are that companies that understand the regulatory landscape and work with regulators can move faster than competitors. Yottar has deep relationships with German grid operators and understands that market's rules. Base Power has been working with ERCOT (the Texas grid operator) for years. These relationships matter.

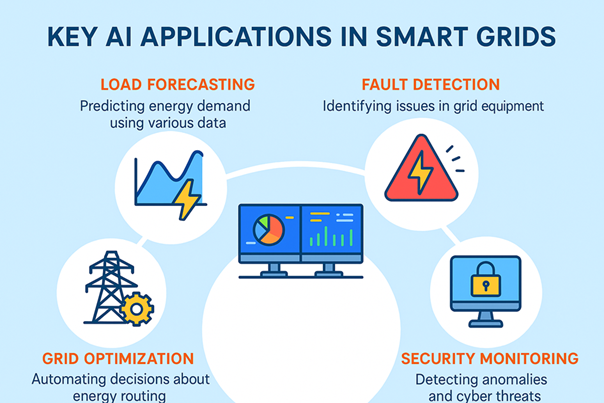

Machine Learning and AI: Making the Grid Intelligent

Let's talk about what software actually does on the grid.

First, there's monitoring. Modern grid monitoring uses thousands of sensors that constantly measure voltage, frequency, power flow, and consumption. This data is streamed to central systems. Traditional systems process this data with fixed rules: if frequency drops below X, do Y. If voltage drops below Z, do W.

Machine learning models can do better. They can learn patterns in the data and predict problems before they happen. If a specific pattern of voltage fluctuations historically precedes a blackout, the model can detect that pattern and trigger preventive action. If certain patterns indicate equipment failure, operators can schedule maintenance before failure occurs.

Second, there's forecasting. Predicting future demand and supply is critical. If the grid operator knows that demand will spike at 6 PM because of air conditioning load, they can position resources to handle that spike. If solar generation will drop at sunset, they can line up other resources in advance.

Traditional forecasting uses historical data and simple models. Machine learning can incorporate much more information. Weather forecasts, time of day, day of week, special events, economic indicators, news events, all of it influences demand. Good models integrate all of it and make better predictions.

Third, there's optimization. The grid at any moment needs to match supply and demand across thousands of assets. This is a massive optimization problem. Traditional approaches use heuristics and rules of thumb. Machine learning models can explore far more possibilities and find better solutions.

Fourth, there's control. Once you've identified what the grid should do, you need to actually do it. Send signals to generators, batteries, flexible loads, and other devices. Coordinate their actions. Monitor outcomes. Adjust in real time. This requires constant decision-making. Machine learning models can make these decisions in milliseconds.

Nvidia and EPRI are building exactly this. Industry-specific AI models trained on power grid data, understanding the physics and economics of electricity, optimized specifically for grid operations. This is different from generic AI. It's AI built for a specific, critical problem.

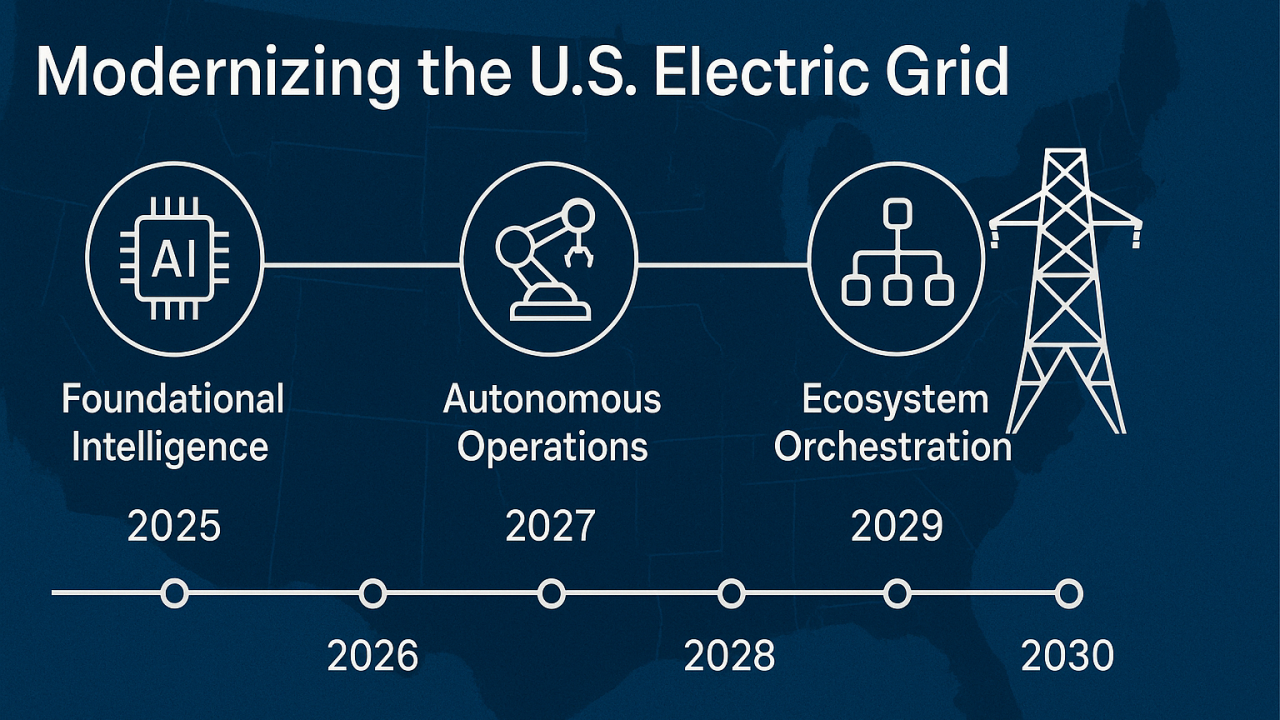

2026: The Year Software Becomes Essential

I think 2026 is when this shifts from interesting to essential. Here's why.

First, the data center wave is becoming impossible to ignore. Companies have committed to so much new capacity that even aggressive deployment of new power plants won't keep up. Software optimization becomes mandatory.

Second, utilities have spent enough years experimenting with new software that the risk profile has shifted. Early deployments have worked. The reliability concerns haven't materialized. The business case is irrefutable. More utilities will commit to modernization in 2026.

Third, regulations are moving. FERC and regional transmission organizations are updating rules. By mid-2026, new market structures will be in place that make deploying advanced software economically attractive rather than economically neutral.

Fourth, the startups have matured. The companies that are surviving this phase—Gridcare, Yottar, Base Power, Terralayr—have learned what works. They've found business models that align incentives. They've proven they can work within utility constraints. They're ready to scale.

Fifth, traditional infrastructure companies are getting into the game. Siemens, ABB, and other industrial automation companies are investing heavily in grid software. When the incumbents move, the market accelerates.

All of this converges in 2026. The grid becomes smarter. Utilities become more operationally efficient. Data centers find more locations to expand. Renewable energy becomes more valuable. Consumers see more stability and lower costs.

None of this means the grid doesn't need new infrastructure. We will absolutely need new generation capacity. But software compounds the value of that infrastructure. It makes existing infrastructure go further. It buys time for new infrastructure to be built.

The Elephant in the Room: Will It Be Enough?

Here's the honest answer: no. Software will not solve the entire grid problem.

Data center demand is growing faster than any optimization can accommodate. Electrification of transportation, heating, and industry will double overall electricity demand in the next 20 years. Renewable energy is growing, but it's not predictable like conventional generation.

The grid absolutely needs new infrastructure. Solar farms, wind farms, nuclear plants, geothermal systems, energy storage facilities—all of it. These take years to build. Permitting takes years. Financing takes years.

What software does is buy time. It squeezes 20% more value out of existing infrastructure. That buys two years of breathing room while new plants are being built. It makes that new infrastructure more valuable when it arrives because the grid is optimized to use it well.

It's not enough to solve the problem. But it's essential to avoiding a crisis while the problem is being solved.

The Path Forward: What This Means for Different Stakeholders

For utilities, the message is clear: modernizing your software isn't optional. It's competitive necessity. Utilities that move fast will be more efficient, more profitable, and better positioned for the future. Those that move slow will find themselves unable to keep up with demand growth and unable to compete on cost.

For startups, there's enormous opportunity. The space is still early. The winning solutions haven't emerged. The companies that solve reliability, regulatory compliance, and integration challenges best will become incumbents.

For investors, this is an interesting time. Software companies solving infrastructure problems tend to have excellent unit economics and strong retention. The grid optimization space has both. Companies in this space are raising at premium valuations. The money is flowing. But the opportunities are real.

For policymakers, the message is that you can't solve grid problems with infrastructure alone. The regulatory framework needs to support software deployment. Rules need to be updated to incentivize the right outcomes. Innovation needs to be encouraged, but not at the expense of reliability.

For consumers, better grid software means more reliable electricity, lower costs, and better integration with renewables. You might not notice the software, but you'll notice the benefits.

Conclusion: Software Is Infrastructure Now

For decades, people thought infrastructure meant physical stuff. Power plants, transmission lines, transformers, cables. You could see it, touch it, build it with cranes and concrete.

Software was auxiliary. Nice to have. Something that made the physical infrastructure work better.

That's inverted now. Software is the critical path. The physical infrastructure exists. But if it's not coordinated with brilliant software, it's essentially useless.

The electrical grid is the proving ground for this shift. We have enough generation capacity if we can coordinate it intelligently. We have enough storage if we can schedule it optimally. We have enough flexibility in demand if we can incentivize and automate it.

The bottleneck is software. The solution is software. The competitive advantage goes to whoever can deploy software that works reliably, integrates with legacy systems, respects regulations, and actually solves the problem.

That's why 2026 matters. That's why these startups matter. That's why utilities are finally paying attention. The grid doesn't need more steel and concrete. It needs more intelligence.

And intelligence runs on software.

FAQ

What exactly is grid optimization software?

Grid optimization software uses real-time data, machine learning, and algorithms to coordinate electricity generation, storage, and consumption across the entire electrical network. It predicts demand, identifies available capacity, coordinates distributed resources like batteries and solar panels, and adjusts loads dynamically to match supply. Essentially, it makes the grid act intelligently instead of reactively, finding more value from existing infrastructure.

How does a virtual power plant actually work?

A virtual power plant aggregates distributed energy resources—home batteries, solar panels, EV chargers, controllable loads—and coordinates them as if they were a single large power plant. Software monitors each asset, predicts their available capacity, and sends signals to discharge or charge them based on grid conditions. When 10,000 home batteries discharge simultaneously under software control, they deliver power equivalent to a conventional power plant, but with faster response times and greater flexibility.

Why can't utilities just build more power plants instead of buying software?

Building a power plant costs

What's preventing faster deployment of grid software?

Utilities are extremely conservative about software changes because the electrical grid is critical infrastructure. A software bug could cause regional blackouts affecting millions of people. Regulatory frameworks were built around traditional power plants and haven't been updated to accommodate new technologies and business models. Integration with legacy systems built over decades is complex. Additionally, utilities operate under strict reliability requirements and prefer proven, tested solutions. These constraints slow deployment, but they exist for good reason.

How much capacity is being wasted on the grid right now?

Estimates suggest 15% to 25% of available grid capacity is invisible to current utility planning processes—either because it exists but utilities can't access it, or because distributed resources aren't coordinated effectively. In the U.S., this represents roughly 10 to 15 gigawatts of wasted capacity, equivalent to 10 to 15 new coal plants. Software that reveals and utilizes this hidden capacity is worth billions of dollars in avoided infrastructure investment.

Will grid software make power cheaper for consumers?

Yes, but indirectly. Utilities that deploy optimization software reduce operational costs by 8% to 12%. These savings don't automatically flow to consumers—that depends on regulatory structure and how profits are distributed. However, utilities that optimize their operations can handle more load without building new infrastructure, which means lower capital costs and lower bill increases for consumers. In markets with more advanced software and favorable regulations (like Denmark), consumers already see lower electricity costs as a result.

What happens when grid software fails or makes a wrong decision?

This is why reliability is the critical constraint. Modern grid software is designed with multiple layers of redundancy. If one decision-making system fails, others take over. If a recommended action would destabilize the grid, safeguards prevent it automatically. Early implementations use extensive monitoring and human oversight—software recommends actions, operators verify them before execution. As systems mature and build track records, more automation becomes possible. The key is that failures don't cascade catastrophically the way they would in a traditional grid.

How does machine learning improve grid forecasting?

Traditional grid forecasting uses historical demand patterns and simple models. Machine learning integrates far more information: weather forecasts, temperature, day of week, special events, economic indicators, social media trends, and years of historical data. Machine learning models can identify subtle patterns that simple models miss. Early implementations show demand forecasting accuracy improvements of 15% to 25%, which translates directly to more efficient grid operations and fewer reserve capacity requirements.

Is grid software secure against cyber attacks?

Security is a legitimate concern, which is why deployment is careful and conservative. Grid software is designed to be resilient against attacks, with redundancy so that no single attack point can compromise the entire system. Commands require authentication and verification. Systems are air-gapped from the internet where possible. However, perfect security is impossible, which is why operators maintain manual override capability. The goal is to make grid operations harder to disrupt with software, not impossible, while building in safeguards that prevent both accidental failures and deliberate attacks from causing cascading failures.

The Bottom Line

The electrical grid in 2025 is at an inflection point. Data center demand has created an urgency that utilities can't ignore. The good news is that we don't need to solve this with infrastructure alone. Smart software can coordinate existing resources far more efficiently. Companies like Gridcare, Yottar, Base Power, and Terralayr have proven the concept works. Regulations are slowly adapting. Utilities are starting to move.

2026 will be the year when grid software stops being novel and becomes essential. The utilities that adapt fastest will be most efficient. The startups that solve the technical and regulatory challenges will become the backbone of modern energy infrastructure. The grid will become smarter, more reliable, and better positioned for the energy demands of an AI-driven world.

The hardware was never the constraint. It's always been coordination. Software solves coordination problems.

Key Takeaways

- The electrical grid coordination crisis is software, not capacity—utilities have 15-25% hidden capacity that existing systems can't see or use

- Data centers will consume 35% of U.S. electricity by 2035, making grid software optimization essential for managing this growth

- Virtual power plants aggregate distributed batteries, solar, and flexible loads into coordinated resources worth billions in avoided infrastructure spending

- Software deployment costs 1.5-3B and 2-3 years for new power plants—the economics heavily favor optimization

- Machine learning forecasting improves demand prediction accuracy 15-25%, directly translating to more efficient grid operations and lower reserve requirements

![Why the Electrical Grid Needs Software Now [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-the-electrical-grid-needs-software-now-2025/image-1-1767028035137.jpg)