Windows 10's Legacy: What Microsoft Got Right (and How It Led to Windows 11 Problems) [2025]

Windows 10 officially ended support in October 2025, but for millions of users, it was more than just an operating system. It was the version of Windows that finally felt like Microsoft was listening. According to HP's guide on Windows 10 support ending, this OS was pivotal in shaping user expectations.

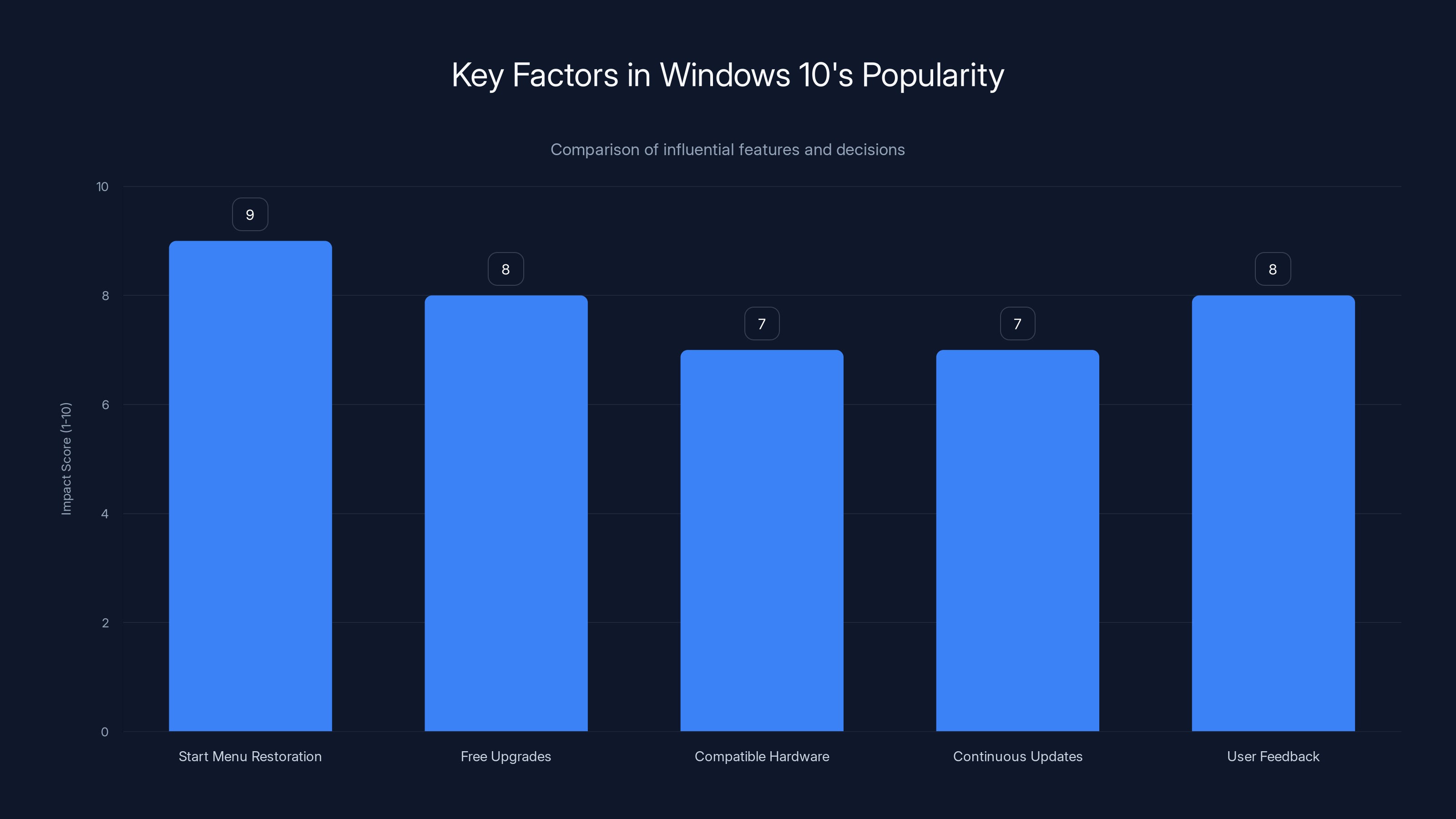

After the catastrophe of Windows 8, Windows 10 arrived like a relief. It brought back the Start menu, ran on virtually any hardware from the last decade, and got free upgrades to basically everyone. It was updated on a regular schedule that actually made sense. And for the first few years, Microsoft seemed genuinely interested in improving the OS based on what people actually wanted, not what some executive thought they should want.

But here's where the story gets complicated: almost everything people complain about in Windows 11 started in Windows 10. The mandatory Microsoft Account sign-in? Windows 10 innovation. Aggressive data collection and telemetry? Windows 10 feature. Software updates that break things, then get "fixed" with more updates? The Windows 10 era introduced that playbook. The confusing mix of old and new design elements scattered throughout the interface? That aesthetic disaster started when Windows 10 tried to have it both ways.

Windows 10 didn't just set up Windows 11 to fail—it also showed us how Microsoft thinks about operating systems now. And if you're frustrated with Windows 11, understanding Windows 10's compromises will help you understand why Microsoft seems to be pushing in a direction that feels more controlling, more fragmented, and honestly, less respectable to the people who actually use these machines.

TL; DR

- Windows 10 succeeded by rolling back Windows 8: A traditional Start menu and familiar interface made it popular enough to become the most-used Windows version since XP.

- Free upgrades and open-source adoption: Windows 10 benefited from Microsoft's culture shift under Satya Nadella, including WSL, Chromium Edge, and more collaborative development.

- The data collection problem started in Windows 10: Aggressive telemetry, privacy concerns, and unclear privacy settings originated during the Windows 10 era, not Windows 11.

- Windows 10 broke things regularly: The "software-as-a-service" update model introduced constant breakage that continues today, despite public beta programs.

- Windows 11 magnified existing problems: Microsoft took Windows 10's uncomfortable compromises and made them worse, removing options while adding more paywalls and AI integrations.

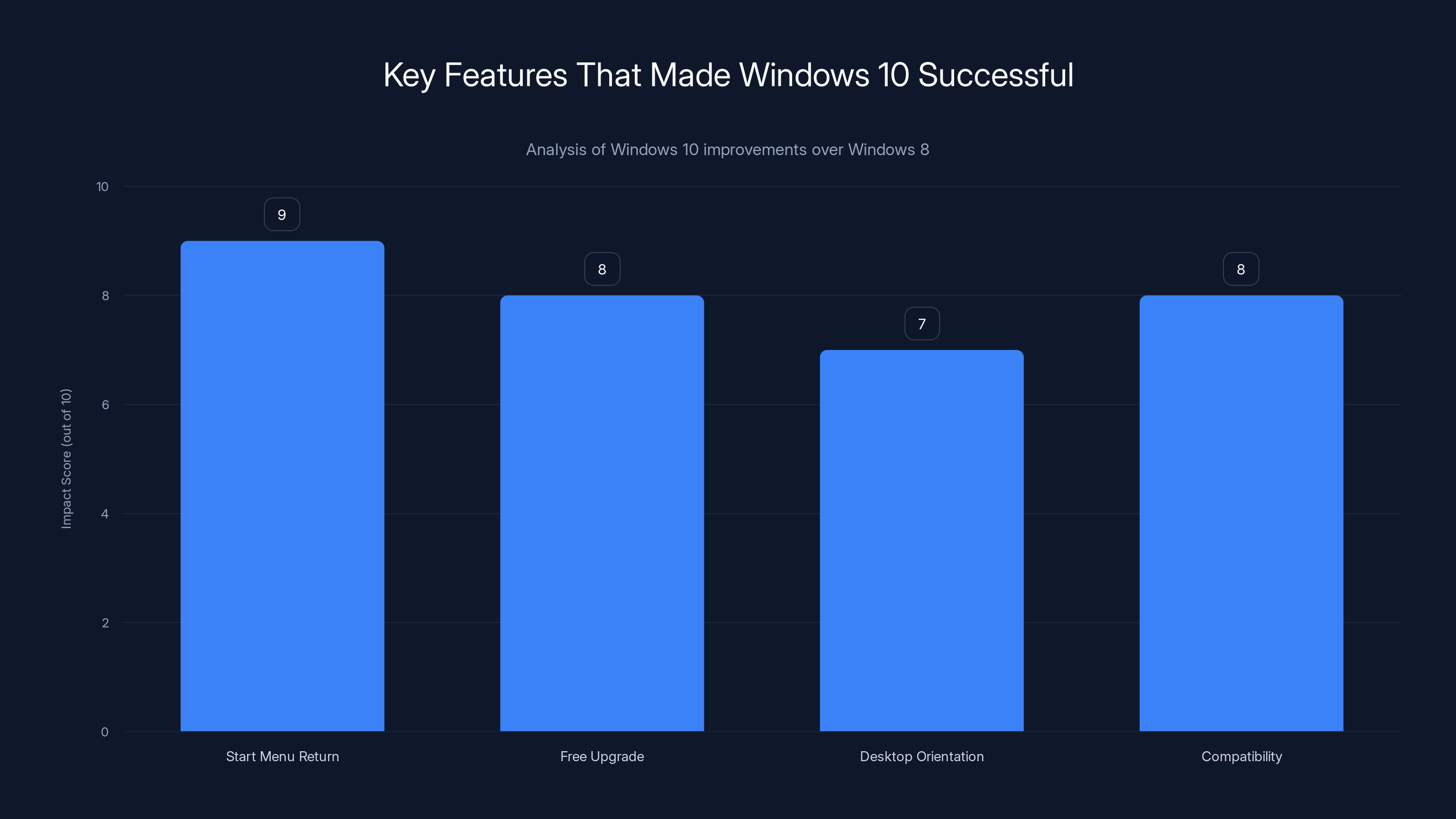

Windows 10's success was driven by the return of the Start Menu, free upgrades, a desktop-oriented interface, and broad hardware compatibility. Estimated data based on feature impact.

What Made Windows 10 Actually Good

When Windows 10 launched in July 2015, Microsoft had just learned one of the harshest lessons in operating system history: if you force users to change how they work, they'll hate you for it. Windows 8 had proven this beyond any doubt.

Windows 8 wasn't actually a bad operating system under the hood. The core improvements were solid. But the full-screen Start menu with large tiles, the emphasis on touchscreen gestures, and the general push to make desktop computing look and feel like smartphone computing created a wall between Windows 8 and the millions of users who worked on traditional keyboards and mice. People had actual work to do. They didn't want to relearn where everything was just because someone at Microsoft decided the future of computing looked like a tablet.

So Windows 10 did something radical for a major OS release: it listened. The Start menu came back, not quite in its Windows 7 form, but recognizable. You could arrange your desktop however you wanted. The default interface was actually desktop-oriented, not tablet-oriented. It was a conscious decision to meet users where they already were instead of forcing them somewhere new.

The other brilliant decision was the free upgrade path. If you were running Windows 7 or Windows 8, you could upgrade to Windows 10 for free. Not a trial. Not a limited license. Free, permanently. Microsoft's logic was smart: get people on the new platform, and worry about monetization later. The company had finally realized that Windows market share meant more than Windows license revenue at this particular moment in history.

But the real genius move was understanding that people had hardware they liked and didn't want to replace. Windows 10 ran on machines from the Windows 7 era. It ran on underpowered laptops. It ran on ancient desktops that people had built themselves. This wasn't an accident—Microsoft actually made an effort to keep system requirements reasonable. You didn't need the latest CPU or 8GB of RAM. It just worked, which was revolutionary for a major OS release.

The update model also changed things fundamentally. Instead of waiting for Windows 11 to ship in 5-7 years with massive changes all at once, Windows 10 got updates twice a year with features, bug fixes, and improvements rolled out on a predictable schedule. This meant developers and users knew when to expect change, and they could plan around it. It also meant Microsoft could move faster—if something was broken, they could fix it in weeks instead of months.

Microsoft also expanded its Insider Program, letting developers and enthusiasts get access to pre-release builds. This wasn't entirely altruistic (it's good testing), but it also gave people a voice. You could see what was coming, test it, report problems, and sometimes actually see your feedback result in changes. That transparency mattered more than people realized.

The open-source shift

Windows 10 launched right as Satya Nadella was reshaping Microsoft's entire philosophy. The company that had once called open source a "cancer" was now contributing to Linux, making Office work on iPad and Android, and completely overhauling Edge to use Chromium instead of a proprietary engine.

For Windows specifically, this meant Windows Subsystem for Linux. This was genuinely innovative. You could run Linux and all its tools directly on Windows, without virtual machines or dual-boot setups. For developers and power users who'd been forced to choose between Windows for gaming and Linux for serious work, this was transformative. It meant Windows became viable for the kind of work that had driven people to Mac and Linux for years.

The Edge switch also mattered more than people realized. The old Edge browser, with its proprietary rendering engine, couldn't run the extensions or handle the web standards that Chrome and Firefox could. Switching to Chromium was an admission that proprietary browser engines were dead, and that compatibility was more important than control. That decision probably frustrated Microsoft executives, but it was the right call.

These decisions signaled that Microsoft wanted to be a platform company that met developers and users where they were, not a company that forced everyone to adopt proprietary, closed ecosystems. For most of Windows 10's life, the company actually seemed to believe that.

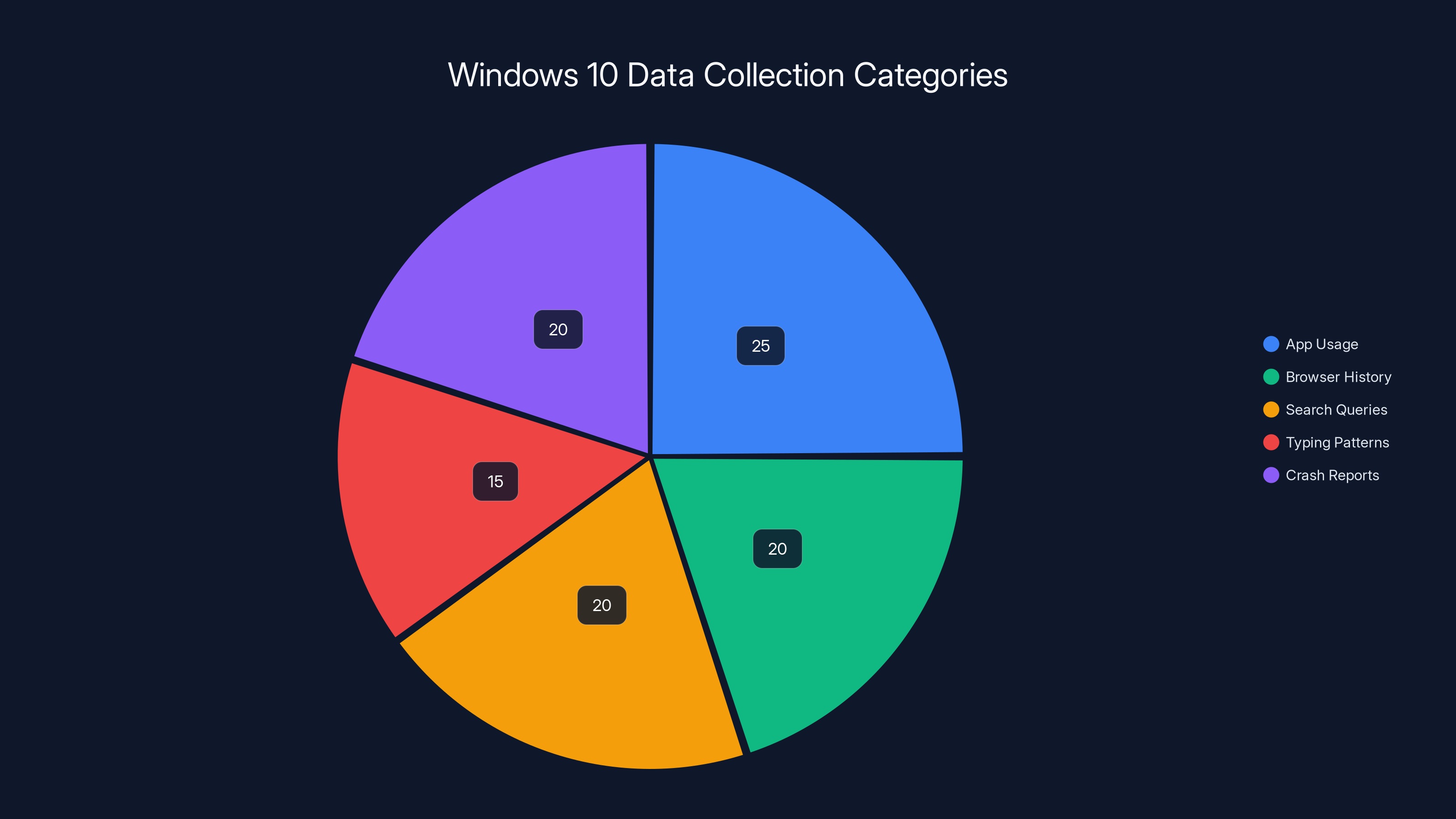

Windows 10 collected diverse data types, with app usage and crash reports being significant focus areas. Estimated data.

The problems that Windows 10 introduced (but nobody noticed)

Windows 10 became beloved because it was such a relief after Windows 8. But if you look carefully at what frustrated people about Windows 11, almost all of it has roots in Windows 10. Microsoft didn't suddenly become a company that didn't care about user experience—they just kept following the trajectory they'd started.

Aggressive data collection and telemetry

Windows 10 wanted to know everything about how you used your computer. Not in a conspiracy-theory way—the company was openly transparent that it was collecting data. But the default settings collected a lot more than Windows 7 did, and the settings to turn it off were buried in menus that most users would never find.

Microsoft's official justification was reasonable: understanding how people used the OS helped them improve it. Knowing which apps crashed, which features people used, what hardware combinations caused problems—that data actually is valuable for OS development. But the breadth of data collection went way beyond crash reports. Windows 10 tracked your app usage, your browser history, your search queries, and your typing patterns. It did this to personalize ads and recommendations.

The frustrating part wasn't that data collection existed—it's that Microsoft didn't make it easy to understand what was being collected or to turn it off. The privacy settings were scattered across multiple menus. Some options did what they said they did, and others seemed to have no effect. People who cared enough to dig deep could find ways to disable most of it, but ordinary users either didn't know they could do this or didn't know there was anything to worry about.

Windows 11 didn't invent this problem—it just made it worse, with fewer options to disable tracking and more integration of cloud services that depend on data collection.

The "SaaS" update model's hidden costs

Windows as a service was supposed to be a good thing. Continuous updates meant bug fixes and features could arrive much faster. Instead of waiting for the next major Windows release, new capabilities could roll out whenever they were ready.

But in practice, the continuous update model meant Windows 10 was broken by its own updates constantly. Feature updates would ship and immediately break printers, audio drivers, or network connectivity for different subsets of users. These weren't edge cases—they affected millions of people. Then Microsoft would release a follow-up update to fix those problems, and sometimes those fixes would break different things.

This happened repeatedly throughout Windows 10's lifecycle, and it happened despite the public beta testing through the Insider Program. The problem was that you can't test every hardware combination—there are too many, and they're too diverse. So problems would make it to the release version, affect millions of users, and then require another update to fix.

Users grew used to the pattern: new feature update arrives, spend a week dealing with unexpected problems or workarounds, finally things stabilize, repeat in six months. It's like living in a house where the landlord occasionally enters and rearranges things without asking, and sometimes breaks things in the process.

What made this particularly frustrating was that Microsoft had beta testers. The Insider Program had millions of people actively testing pre-release versions. The fact that serious problems still made it to release versions meant either the testing wasn't representative enough, or the problems were so subtle that they only appeared in specific real-world configurations.

Windows 11 kept this same update model, and the breakage continued. But at least with Windows 10, most people felt like Microsoft was trying to improve things. With Windows 11, it feels more like the updates are trying to push you toward features and services you don't want.

The Microsoft Account requirement, phase one

One of the most hated aspects of Windows 11 is that Microsoft is increasingly pushing you toward signing in with a Microsoft Account. You can still use a local account, but Windows now actively discourages it and hides that option. Windows 11's setup process practically requires an internet connection and a Microsoft Account.

But this didn't start with Windows 11. Windows 10 introduced the ability to sign in with a Microsoft Account, and on the Home edition, it gradually pushed users toward doing so. It was optional in a way that Windows 11's requirement isn't—you could still create a local account relatively easily. But the default path guided you toward Microsoft Account sign-in.

Microsoft's reasoning was practical: a Microsoft Account meant your settings could sync across devices, your OneDrive could be integrated more seamlessly, and you could manage app purchases and subscriptions in one place. These are genuinely useful features for people in the Microsoft ecosystem.

But it also meant Microsoft could build a profile of who you were, what you owned, and what you did. And it created a dependency—if your account is locked or compromised, you lose access to your entire computer. This is a significant shift from the concept of a personal computer that's yours and yours alone.

Windows 10 didn't force this on most users, so it felt optional. Windows 11 is making it increasingly mandatory, which feels like a breach of the trust that Windows 10 had built.

How Windows 11 made things worse (and broke the trust)

Windows 11 shipped in October 2021 as an incremental update to Windows 10. The original marketing was cautious—yes, it's a new version, but it's built on Windows 10's foundation. Don't expect everything to change.

In practice, Windows 11 kept most of Windows 10's core under the hood but redesigned the interface and changed fundamental assumptions about how users interact with their computers. And in most cases, Microsoft's changes made things worse, removed options that people liked, or introduced more aggressive monetization.

The controversial UI redesign

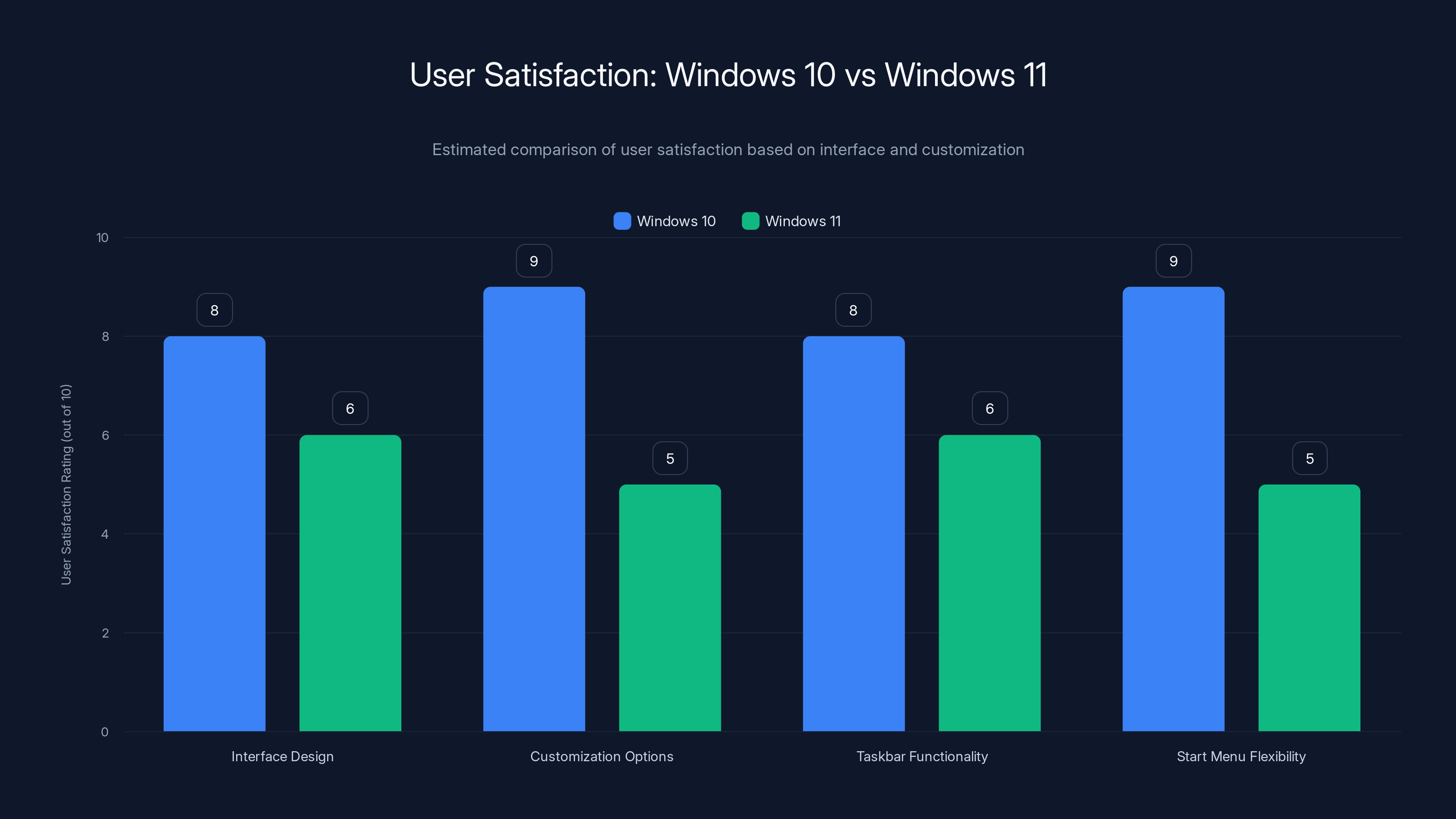

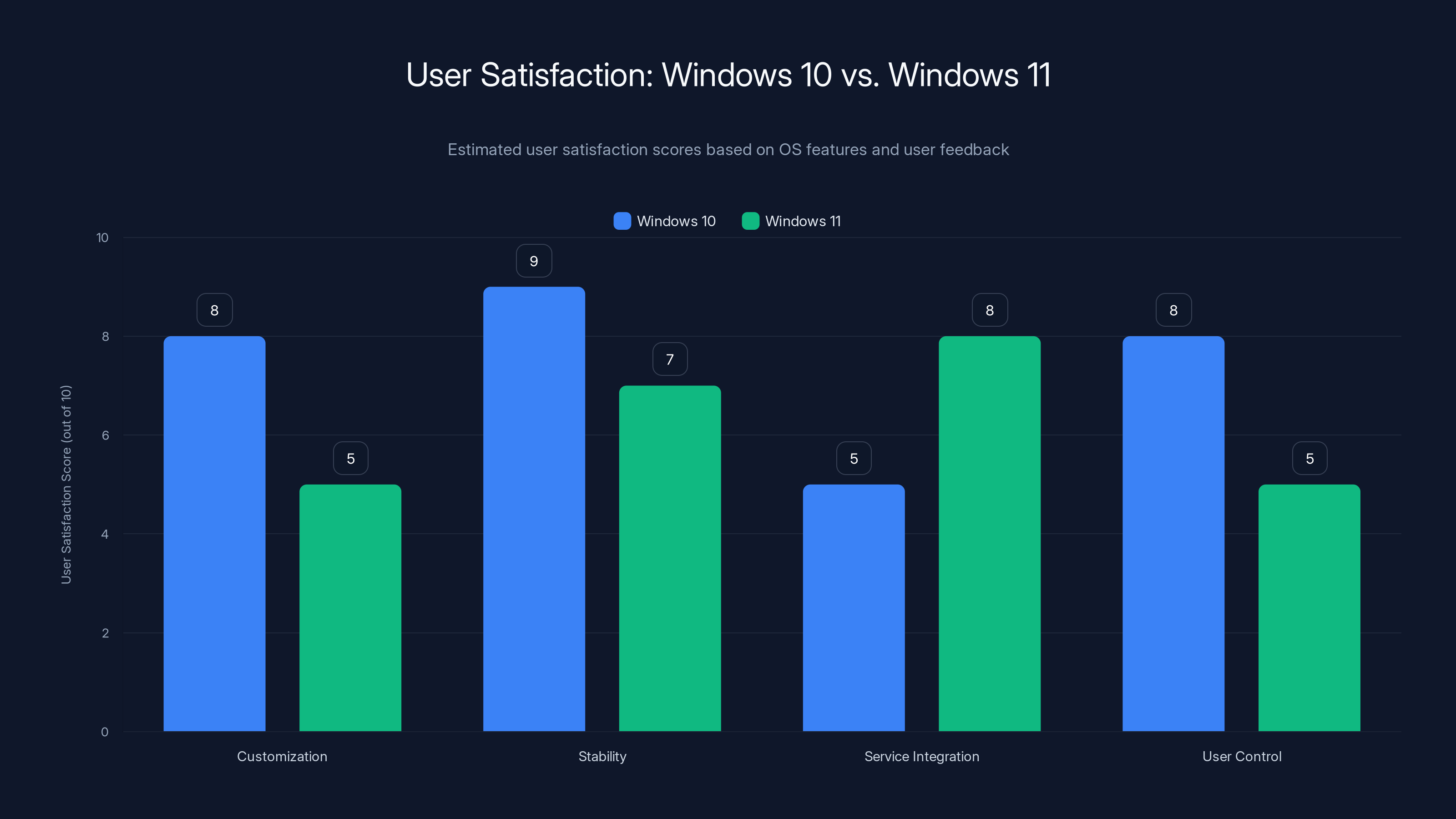

Windows 11's new interface is polarizing. The centered Start menu and taskbar look more modern than Windows 10's left-aligned design. The rounded corners and updated design language feel more cohesive than Windows 10's mishmash of old and new styles.

But it also removed functionality that Windows 10 had. Dragging and dropping to the taskbar behaves differently. Right-clicking on the taskbar gives you fewer options. The Start menu is less customizable. Windows 11 looks cleaner and more minimal, but it's less powerful and less flexible.

There's a philosophy difference here: Windows 10 assumed users wanted to customize their experience, so it gave you lots of options. Windows 11 assumes users want simplicity, so Microsoft removed options and set defaults that work for most people. For people who liked Windows 10's flexibility, this feels like regression.

The hardware requirements that locked people out

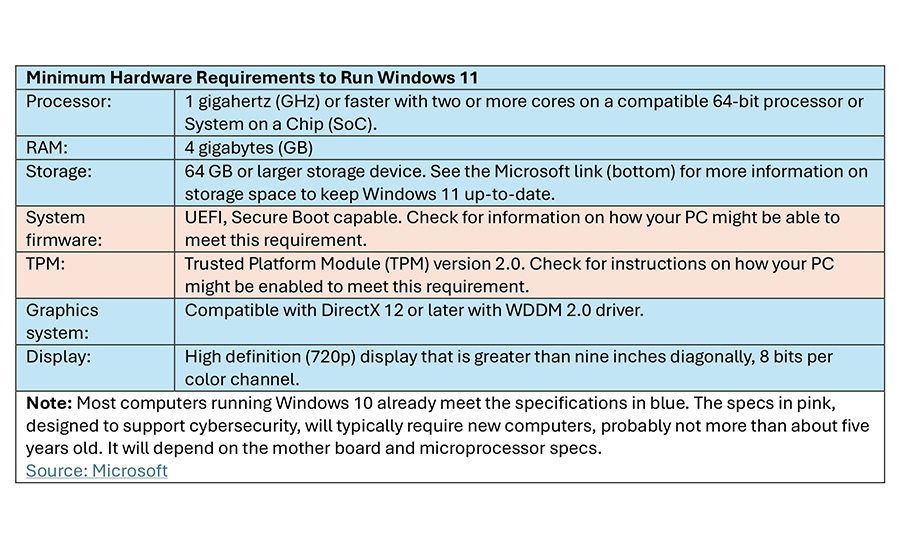

Windows 10 ran on machines from 2007. Windows 11 requires specific hardware: 8GB of RAM, 64GB of storage, TPM 2.0, and UEFI firmware. On paper, this doesn't sound that restrictive. TPM 2.0 became standard on most motherboards around 2016.

But in practice, it meant millions of people with perfectly functional hardware couldn't upgrade. A five-year-old laptop or a gaming PC from 2015 that still worked great? Locked out unless you purchased new hardware. Microsoft's justification was about security—TPM 2.0 enables better encryption and security features—but the effect was that people felt forced to buy new computers.

Windows 10 had no such barrier. You could run it on almost anything. This philosophy of inclusivity was part of why Windows 10 became so widely used. Windows 11's hardware requirements felt like Microsoft was saying, "You can use Windows, but only if you have hardware we approve."

Microsoft did eventually provide a workaround to install Windows 11 on unsupported hardware, but it's not officially supported and Microsoft made it clear that doing so was at your own risk. The barrier exists to push people toward new hardware, and that hardware usually comes pre-installed with Windows 11.

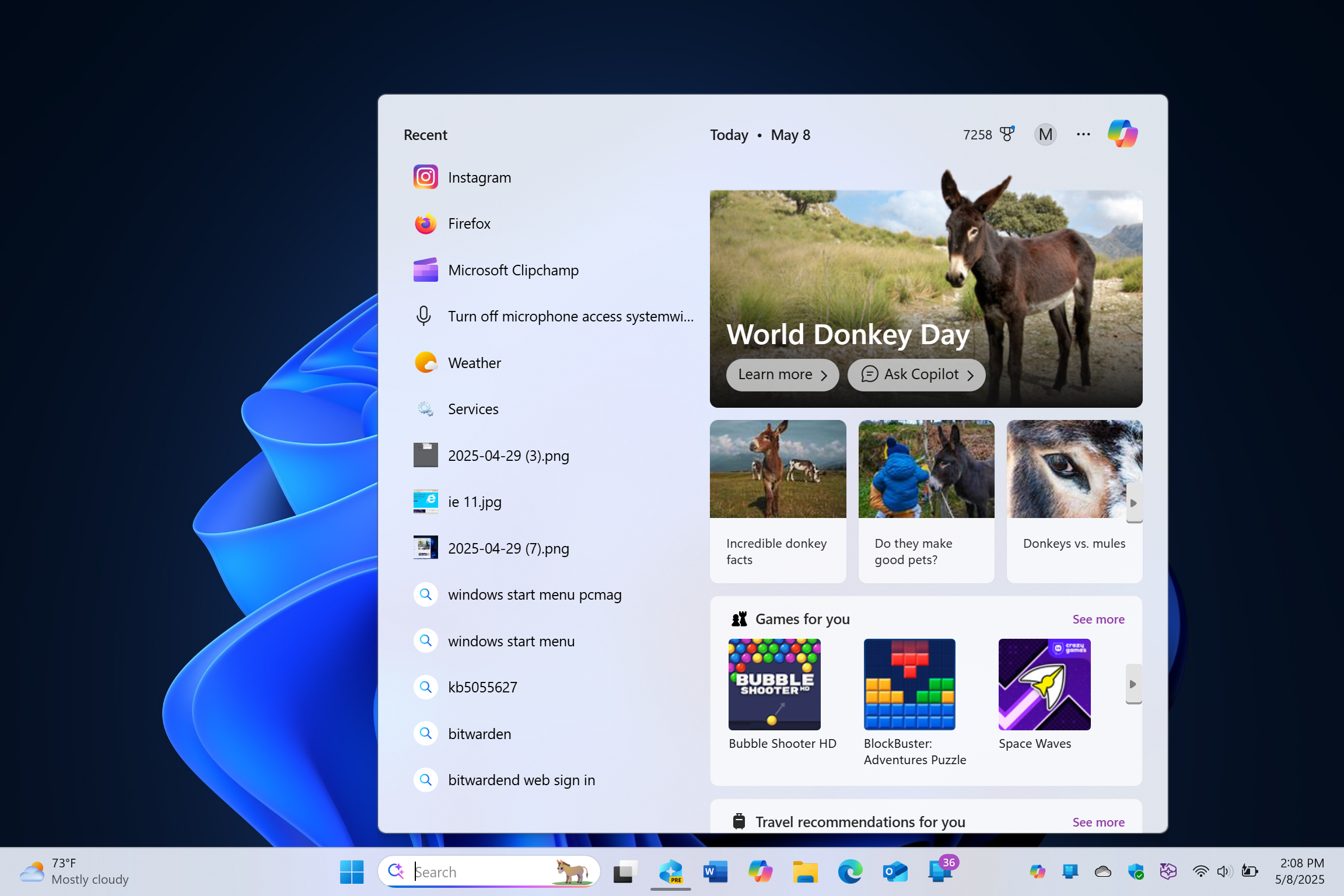

The start menu that tries to sell you things

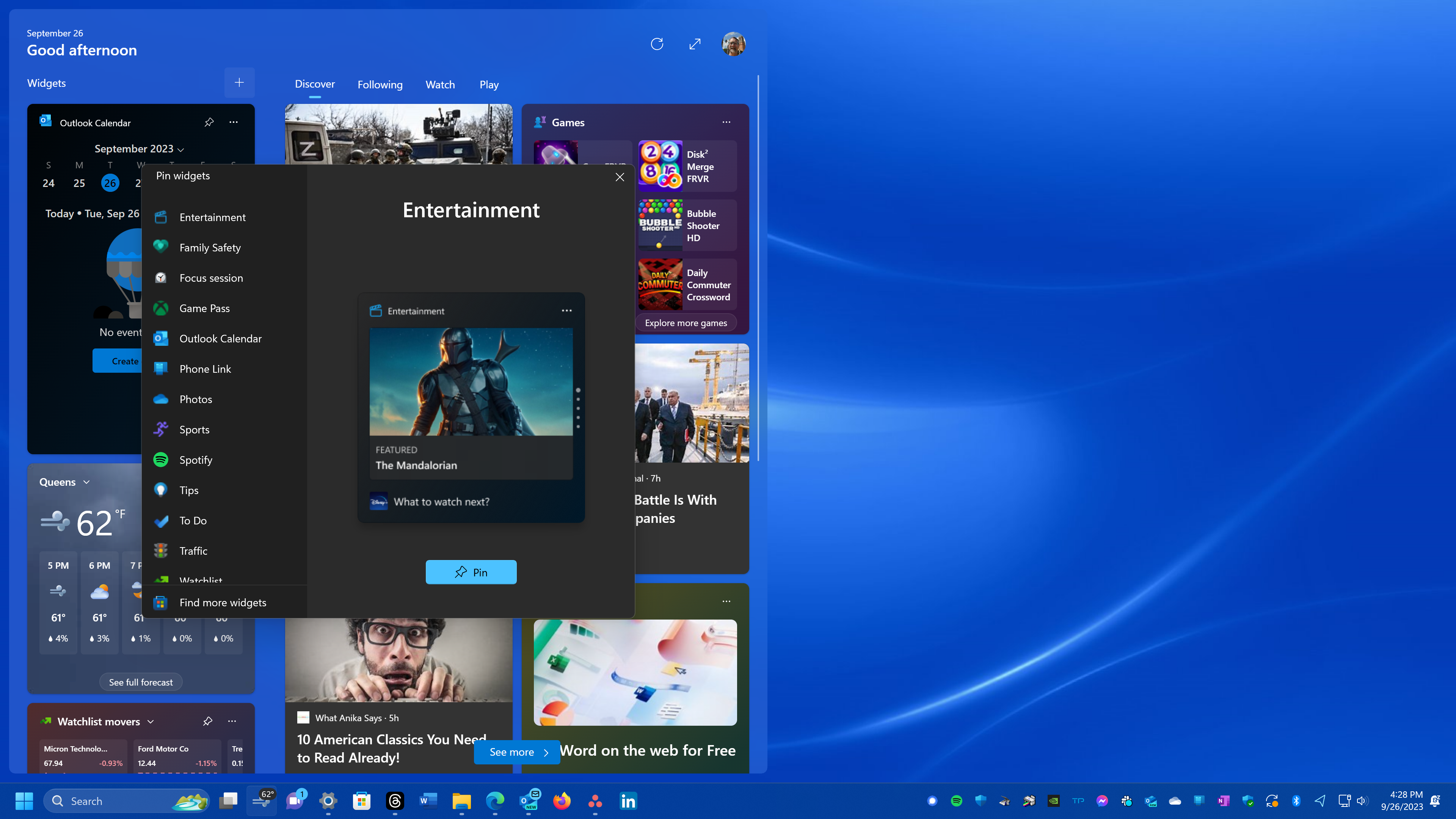

Windows 11's Start menu is mostly functional, but it includes recommendations from the Microsoft Store by default. These aren't ads in the traditional sense—they're just suggestions for apps and games you might want to install. But they're there without you asking, and they're from apps that Microsoft would like you to buy subscriptions for.

Windows 10's Start menu was cluttered with tiles you'd pinned there yourself, or defaults that you could unpin easily. It wasn't selling you anything. It was just your entry point to your computer.

This shift reflects a broader move toward treating Windows as a platform to sell services rather than just an operating system. Windows 11 includes Microsoft Copilot AI integration, OneDrive integration that encourages you to pay for more storage, Game Pass suggestions, and integration with Microsoft 365 services. None of these are bad individually, but together they make Windows 11 feel less like your personal computer and more like a delivery platform for Microsoft's subscription services.

Bing-ification and other unpopular defaults

Windows 11 changed the default search engine in Windows Search to Bing, where Windows 10 had no strong default. It integrated Microsoft Teams into the system in ways that are hard to remove. It pushes OneDrive into your face if you don't subscribe to Microsoft 365. Every Windows 11 update seems to add more Copilot integration and more nudges toward Microsoft services.

None of these individual changes are disasters, but they accumulate. Windows 10 felt like a neutral platform that happened to be made by Microsoft. Windows 11 feels like an advertisement for Microsoft's subscription services that also happens to be an operating system.

Windows 10 changed some defaults too, but those changes felt more about improving the experience and less about pushing services. Windows 11's defaults feel intentionally designed to push you toward subscriptions and Microsoft services.

Windows 10's popularity was driven by restoring the Start menu, offering free upgrades, and maintaining compatibility with older hardware. Estimated data based on qualitative insights.

The design incoherence problem that got worse

Windows 10 was incoherent. It mixed the old Windows 7 Control Panel with the newer Settings app. Some features were in one place, some in another. The design language from different eras of Windows existed side-by-side. This was genuinely annoying—you'd open Settings, not find what you wanted, and have to dig through Control Panel instead.

But Microsoft's reasoning was practical: the old Control Panel had years of functionality that the new Settings app hadn't replicated. Rather than hide or break that functionality, they left both in place. It was messy, but it meant all the legacy features still worked.

Windows 11 theoretically promised to fix this. It would modernize the design, unify the control panels, and make everything cohesive. In reality, Windows 11 is just as incoherent, maybe more so. Settings and Control Panel still both exist. New design elements mix with old ones. The operating system feels like it was assembled from different projects that don't quite talk to each other.

The difference is that Windows 10 felt like the incoherence was temporary—like Microsoft was actively working toward a more unified design. Windows 11 feels like Windows will always be incoherent, and Microsoft has stopped trying to fix it.

Why Windows 10's success set up Windows 11 for criticism

Here's the fundamental problem: Windows 10 was so successful because it felt like Microsoft had stepped back and let the OS be an OS. It wasn't trying to be a phone. It wasn't trying to force a particular workflow. It was stable enough, flexible enough, and non-intrusive enough that people could install it, configure it how they wanted, and get to work.

That success created expectations. People got used to having a choice about how to use their computer. They got used to Microsoft focusing on compatibility and stability rather than pushing services. They got used to being able to customize their experience.

Windows 11 takes the opposite approach. It imposes more choices on you. It pushes services more aggressively. It removes customization options in the name of simplicity. It treats Windows as a platform for delivering Microsoft's services rather than as a tool for your work.

Windows 10 set a baseline for what users expected from Windows, and Windows 11 falls short of that baseline in most areas where it matters. That's why Windows 11 feels like a downgrade to so many people, even though it has more features and better performance in some areas.

The irony is that Windows 10 showed Microsoft how to make an OS people actually like: step back, focus on compatibility, let users customize, and don't push your services. But the company didn't repeat that success with Windows 11. Instead, it doubled down on the opposite approach.

Estimated data suggests that Windows 10 users were generally more satisfied with interface design and customization options compared to Windows 11, which is perceived as less flexible and user-friendly.

What changed at Microsoft between Windows 10 and Windows 11

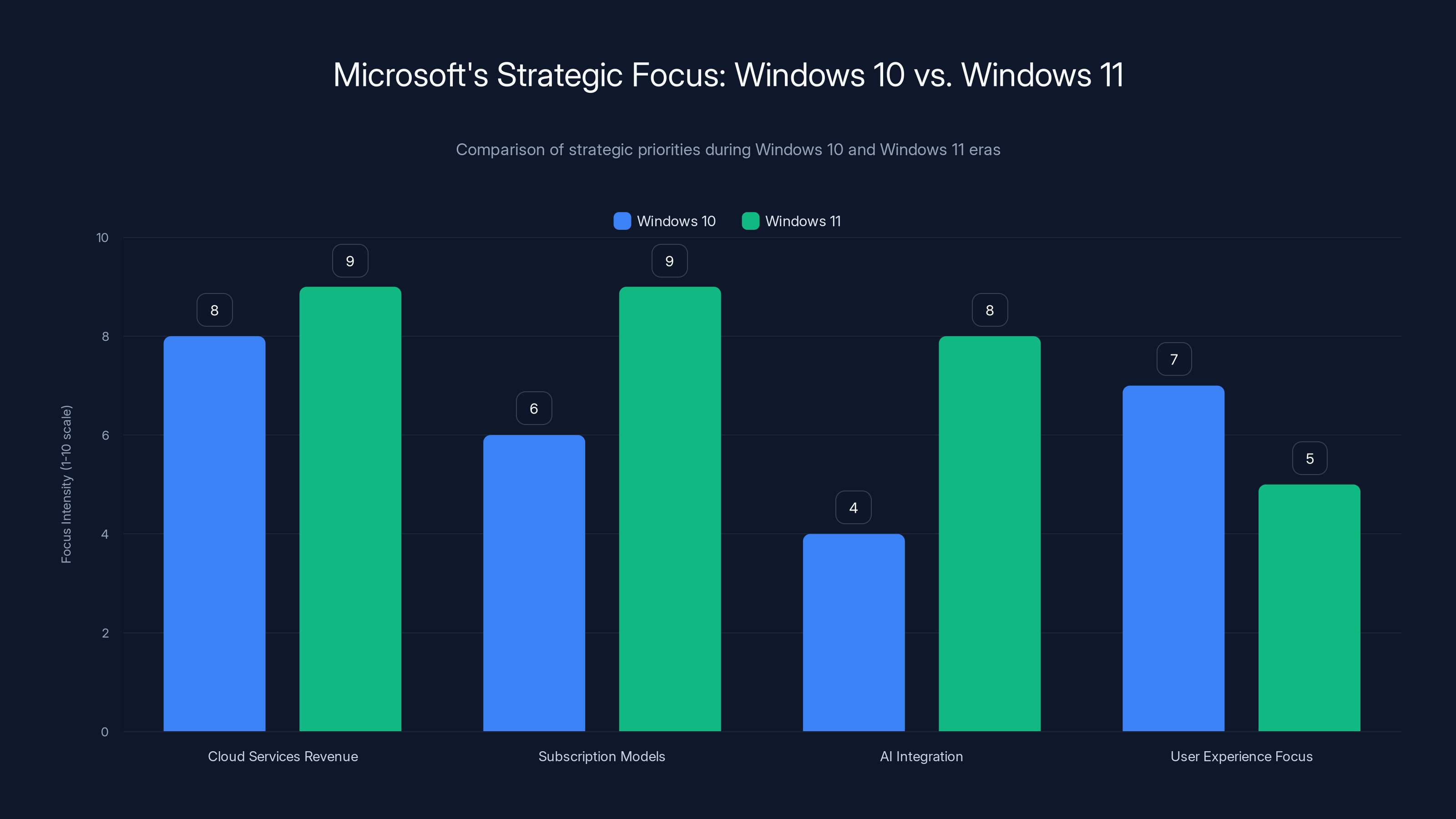

It's tempting to say that Satya Nadella changed Microsoft for the better during the Windows 10 years, and then for the worse during Windows 11. But that's not quite what happened. Nadella's Microsoft has been consistent: increase cloud services revenue, push subscription models, integrate AI everywhere, and use the Windows platform to distribute all of those.

During the Windows 10 years, Microsoft's growth strategy was working through growth, so there was less pressure to monetize Windows users aggressively. The company was making money hand over fist from Azure, Office 365, and other cloud services. Windows could be a solid, non-aggressive platform because the company didn't need to squeeze revenue from every Windows user.

By the time Windows 11 launched, Microsoft's focus had shifted. Subscriptions were even more core to the business plan. The company was building or acquiring AI capabilities, and it needed a distribution channel for those. Windows was suddenly much more strategically important as a platform for pushing subscriptions and AI.

So Windows 11 is actually consistent with where Microsoft was always heading. The company didn't become more evil or less user-focused. It just became more willing to sacrifice user experience in the name of platform objectives.

Windows 10's reputation benefited from timing. It launched right as Microsoft was shifting toward openness and away from aggressive monetization. But that was never the end goal. It was just where the company happened to be at that moment.

The lessons that Windows 10 and Windows 11 teach about platform control

The Windows 10 to Windows 11 transition is a masterclass in how operating system strategy shifts when companies get more powerful. Microsoft had the leverage with Windows 10 and chose not to exercise it aggressively. By Windows 11, the company had even more leverage, and it chose to exercise it.

This happens because once a company has market dominance in a platform, the incentives change. When Windows 10 was winning market share back from Windows 8, Microsoft's incentive was to make users happy so they'd switch. Once Windows had dominant market share again, the incentive shifted to extracting value from that dominance.

For users, the lesson is that an operating system is only as good as the company's current incentives to make it good. If a company has dominant market position and needs to grow revenue, the pressure to monetize users aggressively inevitably increases. You can see this across platforms: Apple's moves toward more control and monetization as iPhone dominance increased, Google's increasing integration of ads and services as Android dominance solidified, Microsoft's increasing push of subscriptions and services as Windows dominance returned.

Windows 10 is remembered fondly partly because it was good, but also partly because it arrived at a moment when Microsoft had incentives aligned with making a good operating system. Windows 11 is disliked partly because it's worse, but also partly because those incentives have realigned.

During Windows 11, Microsoft's focus on cloud services, subscriptions, and AI integration increased, while user experience focus slightly decreased. (Estimated data)

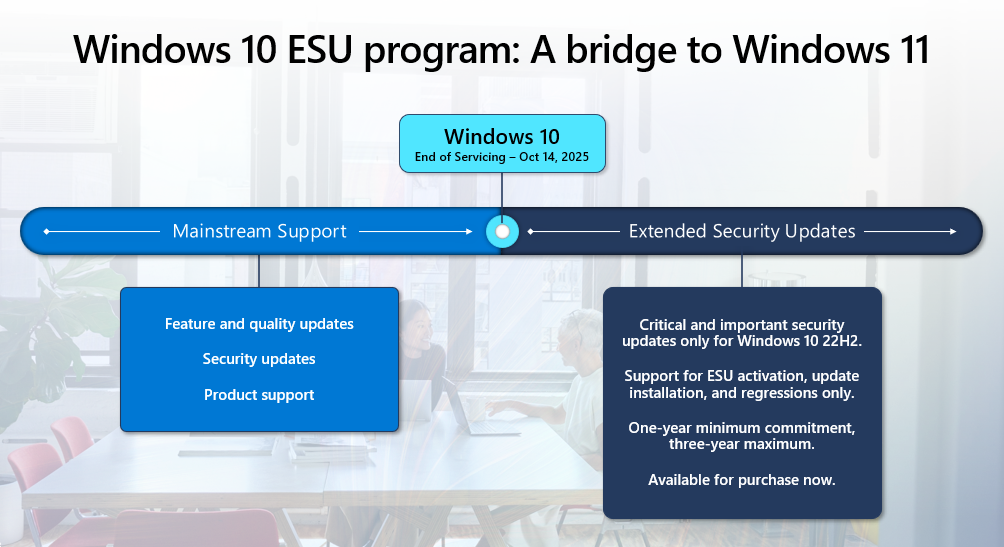

Is Windows 10 really dead?

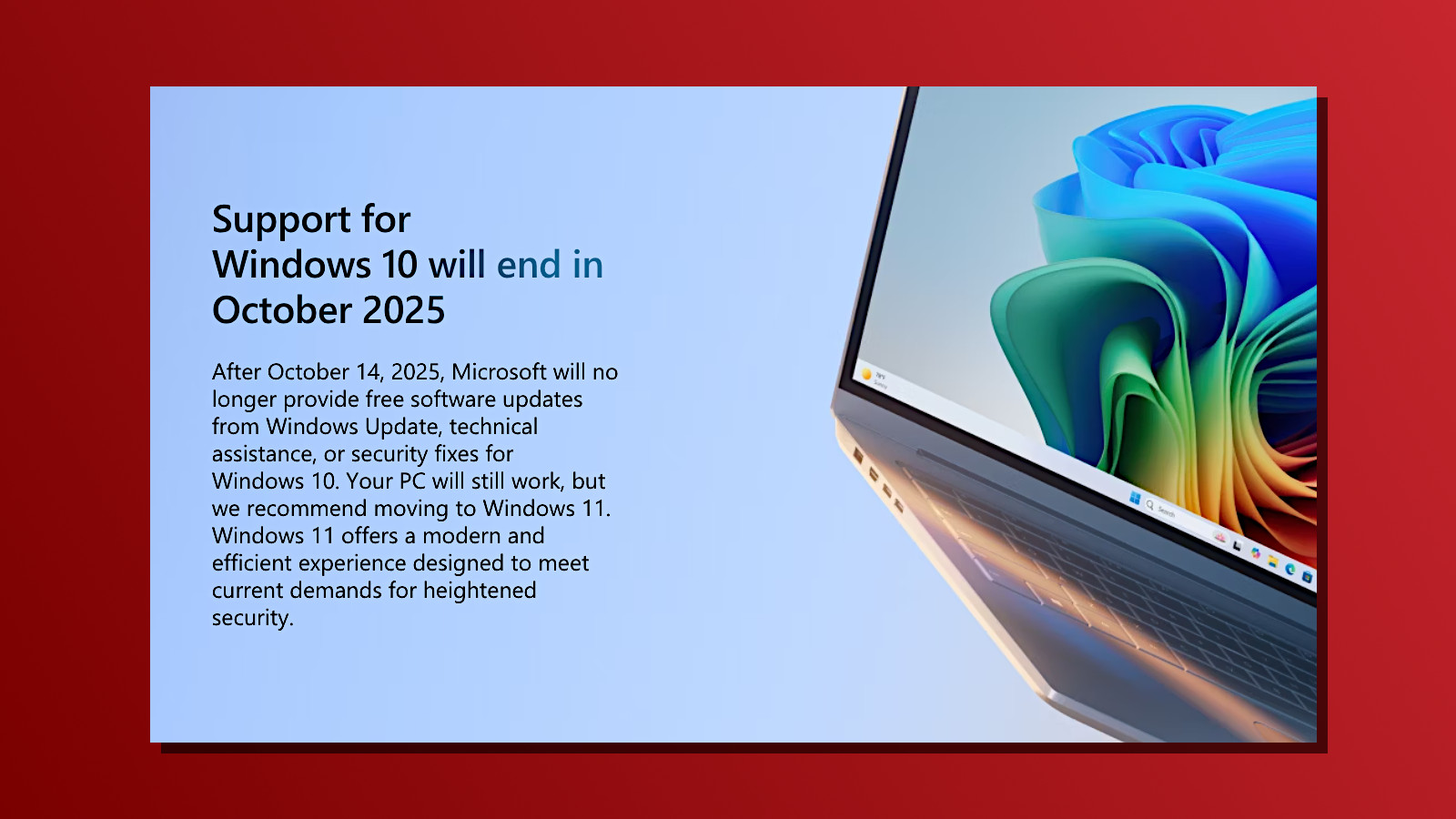

Microsoft's official support for Windows 10 ended October 14, 2025. But in practical terms, Windows 10 will linger for years.

Home users can get free security updates through October 2026. Businesses can get updates through October 2028 by paying for extended support (which is relatively inexpensive). Schools and governments can negotiate their own support timelines.

Even more importantly, the fundamental apps and services in Windows 10 won't stop working. Edge, Windows Defender, and the core system libraries will keep getting updates through at least 2028. Your files won't suddenly stop opening. The internet won't stop working. Windows 10 won't become unusable just because Microsoft stopped pushing updates.

What will change is that security patches will eventually stop coming, apps and games will start requiring Windows 11, and hardware vendors will stop providing drivers for Windows 10. For people doing critical security work or who need cutting-edge driver support, that's a significant problem. For people just checking email and browsing the web, Windows 10 will work for years yet.

The real question is whether upgrading to Windows 11 is worth it. For people with compatible hardware and who don't mind the interface changes, Windows 11 is genuinely solid. The performance is better, the security features are more modern, and the design language is more cohesive.

But for people with older hardware, or who prefer Windows 10's interface, or who are philosophically uncomfortable with Windows 11's push toward subscriptions and cloud services, staying on Windows 10 for a few more years is reasonable. Security patches will still arrive for a while, and even after they stop, Windows 10 will still be usable for years after that.

What Windows 12 needs to learn from this whole mess

If Windows 12 ever arrives, Microsoft needs to learn the lessons from this whole cycle. Windows 8 taught that breaking user habits has consequences. Windows 10 taught that listening to users and giving them choice creates loyalty. Windows 11 taught that removing choice and pushing services creates resentment.

The pattern is clear: when Microsoft tries to be a partner to its users, treating Windows as a tool for their work rather than a platform for monetization, users like it. When Microsoft tries to optimize for extracting value, users resent it.

For Windows 12, that would mean: restore user choice in the interface, make settings actually discoverable, reduce aggressive data collection, stop pushing subscriptions by default, and ensure the update model doesn't regularly break things. In other words, go back to what Windows 10 did right.

But there's no indication that's where Microsoft is heading. Instead, the company is pushing deeper into subscriptions, aggressive Copilot AI integration, and cloud services. Windows 12 will probably be even more aggressively monetized than Windows 11.

So Windows 10's true legacy might be this: it showed Microsoft how to make an operating system people actually love, and then the company chose not to repeat that success. Users who remember Windows 10 will continue to resent Windows 11, not because it's technically bad, but because it's a worse expression of what an operating system should be for its users.

Windows 10 is perceived to offer better customization and user control, while Windows 11 scores higher in service integration. Estimated data based on user feedback trends.

FAQ

What made Windows 10 so popular compared to other versions of Windows?

Windows 10 succeeded primarily because it reversed Windows 8's most unpopular decisions by restoring the traditional Start menu and desktop-first interface, while also offering free upgrades to previous Windows users and compatible hardware requirements that allowed it to run on older machines. Additionally, Microsoft's culture shift under Satya Nadella made Windows 10 feel like the company was genuinely listening to users rather than forcing change for change's sake, and the continuous update model allowed features to improve without waiting for a major new release.

How did Windows 10's design choices create problems for Windows 11?

Windows 10 introduced many of the controversial elements that plague Windows 11, including aggressive telemetry and data collection, the push toward Microsoft Account sign-in, regular update breakage from the SaaS model, and a mixture of old and new design elements. Windows 11 didn't invent these problems, but it magnified them by removing user choice, making data collection harder to disable, requiring hardware specifications that locked people out, and pushing subscriptions and services more aggressively. Windows 11 essentially took Windows 10's compromises and made them worse.

Is Windows 10 actually dead if Microsoft still provides some updates?

Windows 10's official support ended October 14, 2025, but it's not immediately dead in practical terms. Home users get free security updates through October 2026, businesses can purchase extended support through 2028, and critical system apps like Edge and Windows Defender will receive updates through at least 2028 regardless. For casual users, Windows 10 will remain usable and reasonably secure for several years, though eventually security patches will stop arriving and app compatibility will gradually decline as developers target Windows 11.

Why did Microsoft shift its approach between Windows 10 and Windows 11?

Microsoft's incentive structure shifted between the two versions. Windows 10 launched when Microsoft needed to win back market share from Windows 8, so the company prioritized user satisfaction and choice. By Windows 11, Microsoft had restored Windows dominance and needed to grow revenue from subscriptions, cloud services, and AI integration. The company's approach to Windows shifted from being a friendly platform partner to being a distribution channel for monetization strategies, and that change is visible in every controversial aspect of Windows 11.

Should I stay on Windows 10 or upgrade to Windows 11?

The answer depends on your specific situation. If you have compatible hardware and don't mind Windows 11's interface and philosophy, upgrading provides better performance, modern security features, and continued support. If you have older hardware (lacking TPM 2.0 or sufficient RAM), prefer Windows 10's customization options, or are uncomfortable with Windows 11's push toward subscriptions and cloud integration, staying on Windows 10 for the next few years is reasonable since security updates will continue through 2026 and Windows 10 will remain functional long after that. Evaluate your actual needs rather than rushing to upgrade.

What were Windows 10's biggest weaknesses that carry over to Windows 11?

Windows 10's primary weaknesses were aggressive telemetry and data collection (which users often didn't know how to disable), regular breakage from the continuous update model, a confusing mixture of old and new interface elements, and the beginning of the push toward Microsoft Account sign-in. Windows 11 inherited all of these problems and made them worse by removing the ability to disable tracking, continuing the update breakage, failing to unify the interface, and making Microsoft Account sign-in nearly mandatory. These inherited issues, combined with Windows 11's new problems, created frustration among users who remembered Windows 10 as more respectful of user choice.

Looking back at Windows 10's impact

Windows 10 occupies a unique position in operating system history. It was the most widely adopted version of Windows since Windows XP, achieving that status by doing something relatively rare in tech: stepping back and asking users what they actually wanted.

But Windows 10 also sowed the seeds of its own successor's unpopularity. The data collection problem, the update model's instability, the push toward cloud services and accounts, the mixture of old and new design—all of these started in Windows 10. Microsoft just took them further in Windows 11.

What's instructive is that Windows 10 didn't have to be the way it was. Microsoft could have made those choices differently. It could have collected less data. It could have been more careful about update stability. It could have kept the optional nature of Microsoft Account sign-in. It could have made clear decisions about visual design instead of maintaining backward compatibility at the cost of coherence.

But the company made choices that balanced user experience with its own interests, and those choices generally leaned toward the user experience side. With Windows 11, the balance tipped the other way.

For users today, Windows 10's legacy is complicated. It showed that Microsoft can make an operating system that people actually like. It also showed that, given the right business pressures, the company will abandon those principles quickly. Windows 10 was good not because Microsoft is fundamentally a good company, but because the company's incentives happened to align with making something good.

That's the real lesson as Windows 10 heads into the sunset: never assume that a company will continue to make good choices just because they did so once. Watch the incentives. Those tell you what the company will actually do.

Windows 10 earned its place in history by being Windows 8 with a better attitude. Windows 11 earned its reputation by being Windows 10 with a worse attitude. Whether Microsoft learned anything from that cycle will determine whether Windows 12 is remembered as a return to principle or another step down the same path.

Key Takeaways

- Windows 10 succeeded by reversing Windows 8's unpopular decisions, offering free upgrades, and supporting older hardware broadly.

- Almost all complaints about Windows 11 have origins in Windows 10: telemetry, Microsoft Account push, update breakage, design incoherence.

- Microsoft shifted from user-focused design (Windows 10 era) to service-focused monetization (Windows 11 era) as business incentives changed.

- Windows 11 took Windows 10's compromises and removed the user choice that made them acceptable, creating resentment.

- Windows 10's legacy shows that operating systems are only good when companies have incentives aligned with user satisfaction, not extraction.

![Windows 10's Legacy: What Microsoft Got Right (and How It Led to Windows 11 Problems) [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/windows-10-s-legacy-what-microsoft-got-right-and-how-it-led-/image-1-1767015495068.jpg)