Ancient Hominin Fossil Reveals Secrets of Human Evolution Split [2025]

Introduction: A Jawbone Changes Everything

Imagine holding a piece of bone so old that modern humans didn't exist when the creature it belonged to walked the Earth. That's what anthropologists experienced when they examined jawbone fragments pulled from a cave in northern Morocco. These weren't just any fragments either. They belonged to hominins who lived at one of the most pivotal moments in human history: the moment when our ancestors began walking a fundamentally different evolutionary path from the ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans.

The fossil record is littered with gaps, and nowhere is that gap more crucial than in understanding the deep branches of the human family tree. We know that around 765,000 to 550,000 years ago, our evolutionary path split from the lineages that would eventually produce Neanderthals and Denisovans. But knowing when something happened and actually seeing the fossil evidence of it are two very different things. For decades, anthropologists could only infer this split from genetic data, from fossils of the later species themselves, and from tantalizing fragments that didn't quite fit neatly anywhere.

Now, a discovery from Grotte à Hominidés (which quite literally translates to "Cave of Hominins") near Casablanca is changing that calculation. A team of researchers led by scientists at the Max Planck Institute examined jawbone fragments, teeth, and vertebrae dated to approximately 773,000 years ago. These fossils sit uncomfortably close to that critical moment of divergence. They're not quite human as we'd recognize ourselves, but they're far more advanced than earlier forms of Homo erectus. They represent something in between: the deep ancestors that connect our species to everything that came before.

What makes this discovery truly remarkable isn't just the age of the bones or their location. It's what they tell us about where human evolution was happening during a moment we thought was relatively empty of evidence. For years, the dominant narrative suggested that the most important evolutionary action in producing modern humans was happening in Europe with Homo antecessor, the proposed ancestor of Neanderthals and Denisovans. But these Moroccan fossils suggest a more complex picture: parallel evolution happening on different continents, populations diverging in real time, and Africa remaining the wellspring of human diversity even as early human populations spread across the globe.

The implications ripple backward and forward through time. If we can establish that North African hominins were evolving in one direction while European populations were evolving in another, we have a clearer picture of how human populations separated from other hominin lineages. We also gain insight into a period of history so distant that it seems almost incomprehensible: a time when multiple human-like species existed simultaneously, when our ancestors were still figuring out what it meant to be human, when every evolutionary adaptation represented a subtle shift that wouldn't show its importance until thousands of years had passed.

Let's excavate this discovery together and understand what these ancient bones reveal about our origins.

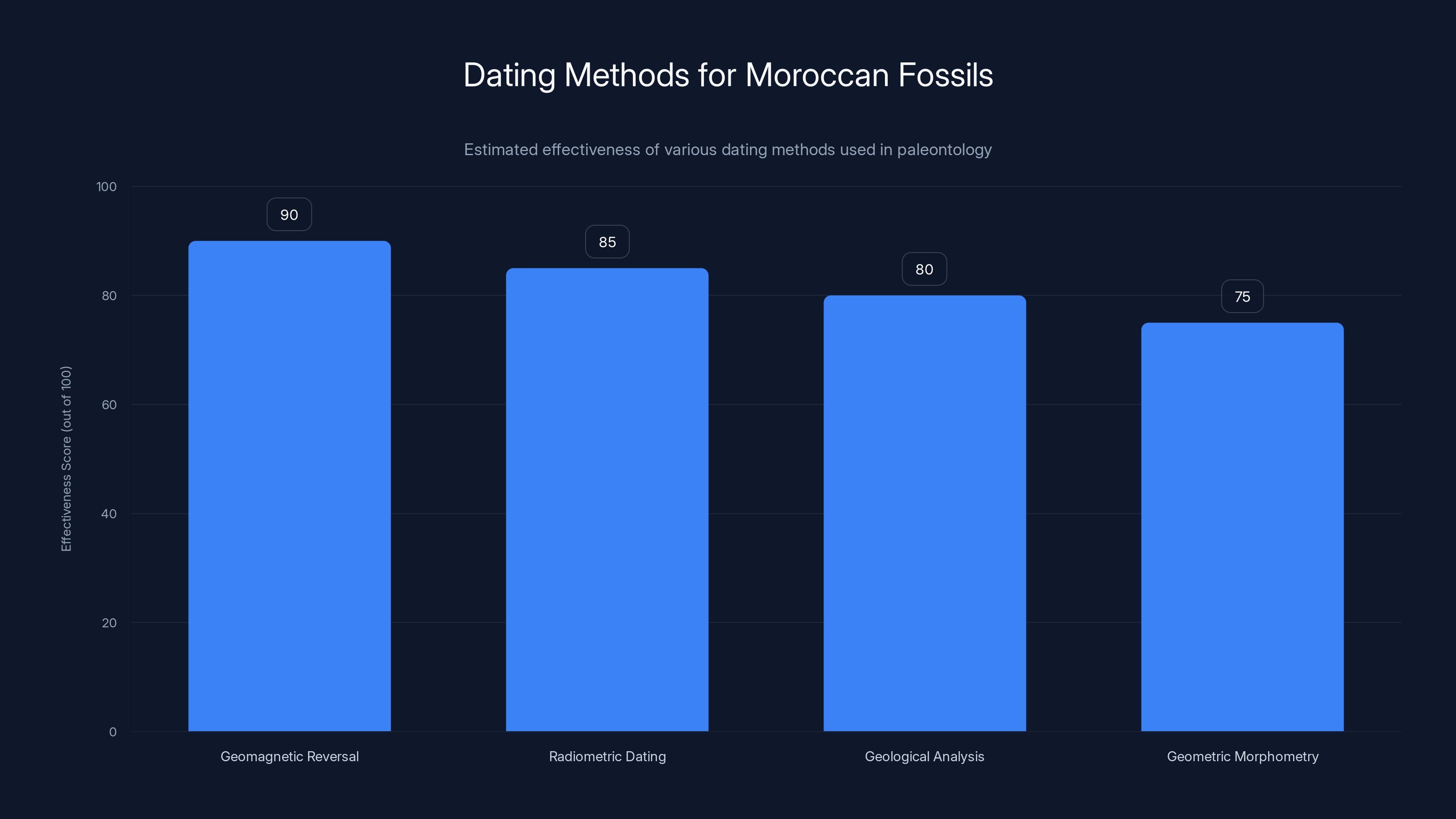

Geomagnetic reversal is estimated to be the most effective method for dating the Moroccan fossils, followed closely by radiometric dating and geological analysis. Estimated data.

TL; DR

- 773,000-year-old fossils from Morocco represent hominins living near the critical divergence point when Homo sapiens' ancestors split from Neanderthal and Denisovan lineages

- North Africa was a major evolutionary hotspot, not a minor backwater, with its own distinct hominin population evolving parallel to European Homo antecessor

- The split likely occurred around 800,000 years ago, slightly earlier than previous estimates based on genetic data alone

- Multiple human species coexisted for hundreds of thousands of years, with complex interactions and genetic admixture that persisted into the modern era

- Better African fossil records are fundamentally changing our understanding of human origins and challenging Eurocentric evolutionary narratives

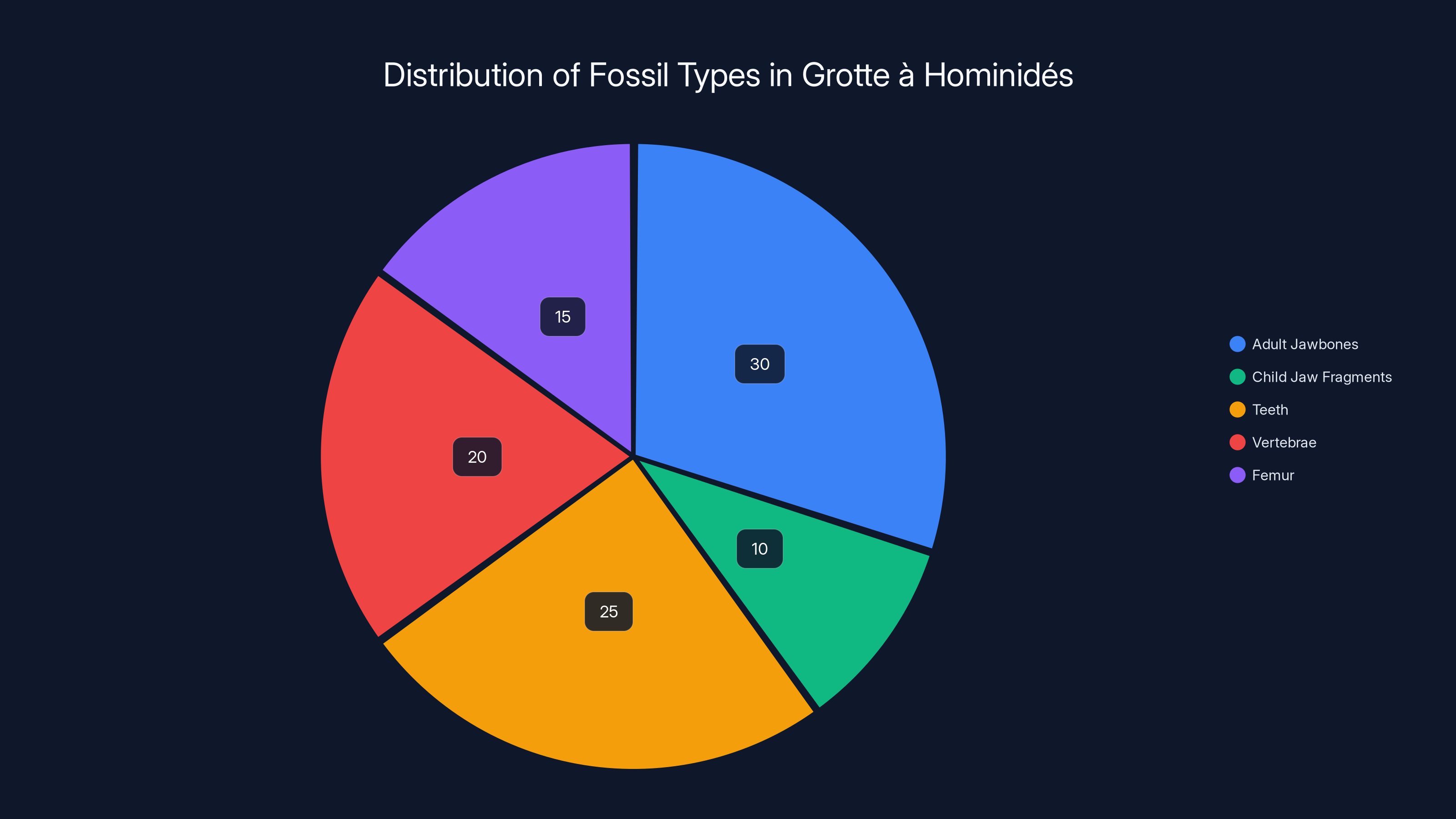

Estimated distribution of fossil types found in Grotte à Hominidés shows a variety of remains, with adult jawbones and teeth being the most prevalent. Estimated data based on narrative description.

The Discovery: From Predator's Den to Scientific Archive

Grotte à Hominidés: A Cave Rich with History

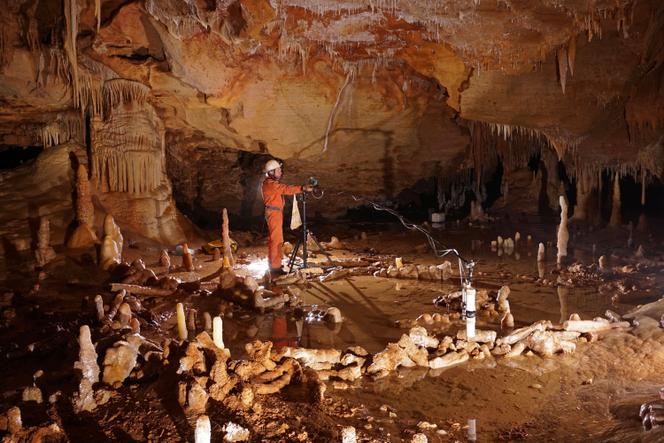

The excavation that produced these remarkable fossils took place in one of those locations that seems almost too perfect for the story: a cave system just southwest of Casablanca, Morocco, literally named the "Cave of Hominins." This wasn't random archaeological luck. Researchers had identified this site based on previous discoveries and understood it held deep time within its rock layers. What they found would require careful, painstaking work to extract and interpret.

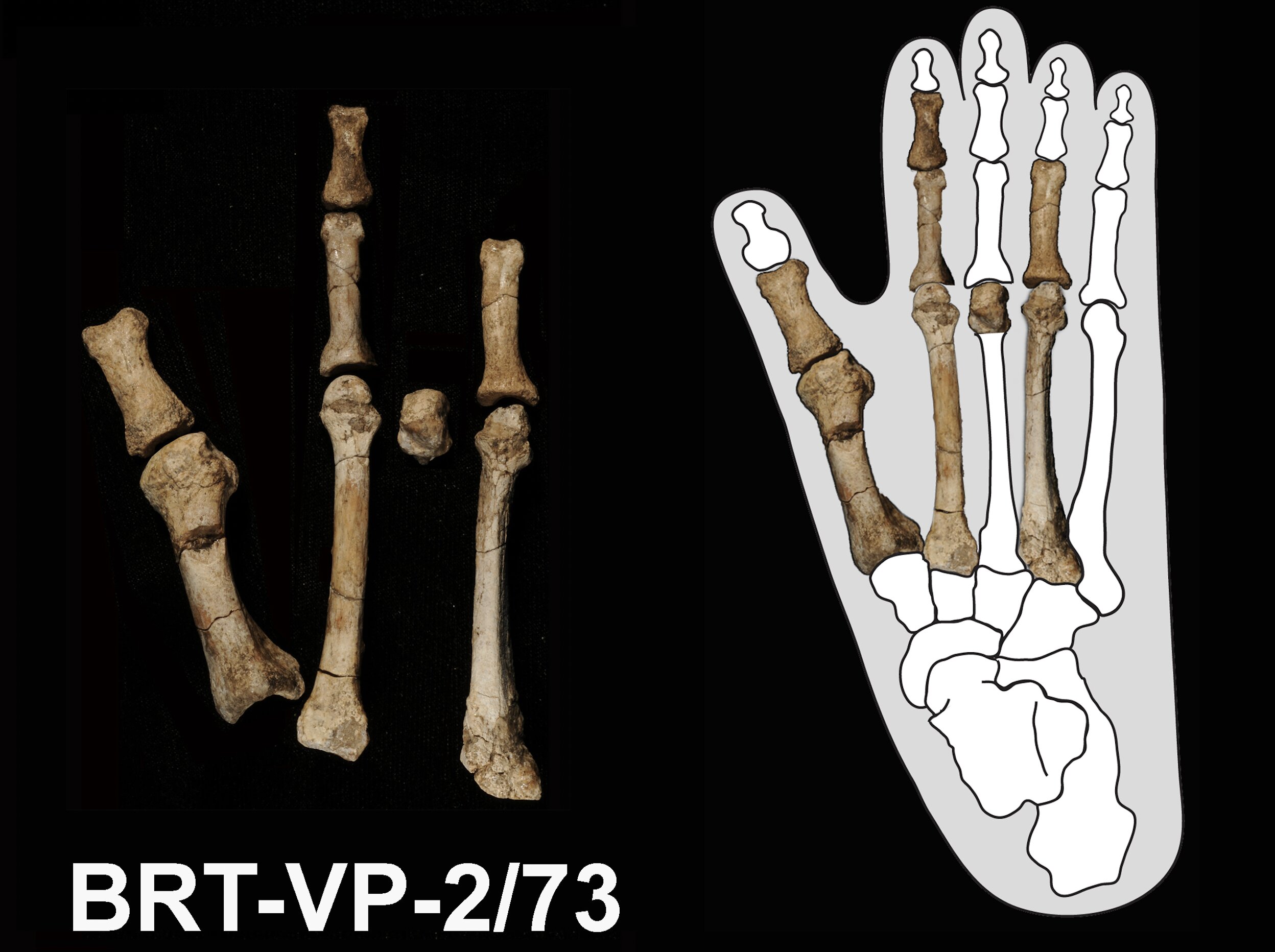

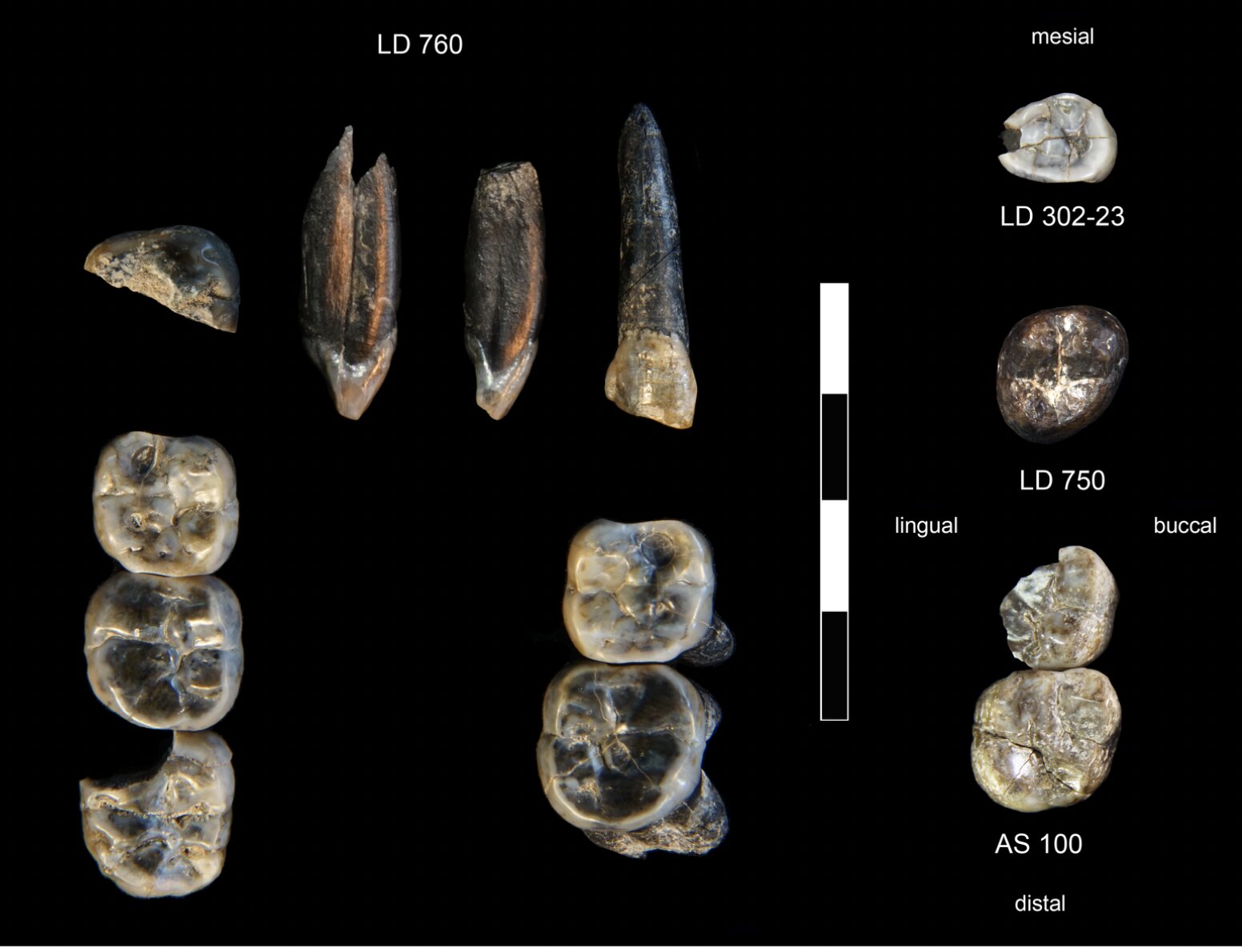

The fossils themselves are fragmentary, as most ancient hominin remains are. An adult's lower jawbone, partially intact. The partial lower jaw of another adult, broken and incomplete. The tiny fragment of a very young child's lower jaw. Scattered teeth that once filled those jaws with the capacity to chew plants, meat, and whatever else these creatures consumed. A handful of vertebrae offering hints about posture and movement. These pieces, individually modest, collectively paint a picture of at least three individuals, probably more, who lived and died in this location 773,000 years ago.

But here's where the story gets darker. One of the more striking pieces of evidence comes from a femur (thighbone) discovered in the same sediment layer. This bone bears unmistakable gnaw marks from sharp carnivore teeth. Someone or something dragged at least some of these remains, consuming parts of them, scattering them through the cave. These weren't careful burials or respectful placements. These were the remains of individuals who became meals for large predators. Their final fate was to be consumed, their bones scattered, their bodies broken. And then, 773,000 years later, their descendants would discover these remains and try to piece together what they could tell us.

The sediment layer containing these fossils is dated using multiple methods, but the key dating marker is elegant in its own right. This layer spans a period of a few thousand years centered on a geomagnetic reversal, a moment when Earth's magnetic field flipped its polarity. This happened approximately 773,000 years ago, providing a datable marker that helps pin down these fossils with reasonable precision. They're not dated to the year, of course, but within a window narrow enough for evolutionary purposes: a snapshot of a specific moment in deep time.

The Excavation and Analysis Process

Once extracted from the cave, these fossils couldn't simply be studied the way a paleontologist might examine a skull sitting on a lab bench. They're fragile. They're incomplete. They're often encased in matrix material that must be carefully removed. Modern paleontology relies heavily on non-destructive imaging techniques that would seem like science fiction a generation ago.

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute, working with colleagues across international teams, deployed micro-CT imaging to create three-dimensional digital models of every bone and tooth. This technique works like a sophisticated medical CAT scan: X-rays are fired at the specimen from multiple angles, and computer algorithms reconstruct the three-dimensional structure from the two-dimensional images. The result is a digital fossil as detailed as the physical one, but one that can be rotated, measured, and compared with precision impossible using physical manipulation alone.

With these digital models in hand, scientists employed a technique called geometric morphometry. This approach goes beyond simple measurements like length or width. Instead, it analyzes the overall shape of anatomical features: how a jawbone curves, where muscle attachment points are located, how the boundary between different tissue types (like enamel and dentine in teeth) is positioned. These shapes can be compared statistically to other fossils, creating a quantitative framework for determining which species or subspecies an individual might belong to.

This is where the real interpretation begins. When researchers compared the shapes of key features in the Moroccan fossils to other hominin species, a picture emerged that was simultaneously familiar and surprising. These weren't quite Homo erectus in the classic sense, yet they retained many features from that earlier species. They weren't yet modern humans, yet they showed hints of the direction evolution was moving. They were caught in the process of transformation.

Understanding the Evolutionary Timeline

The Deep Roots: Homo Erectus and Global Dispersal

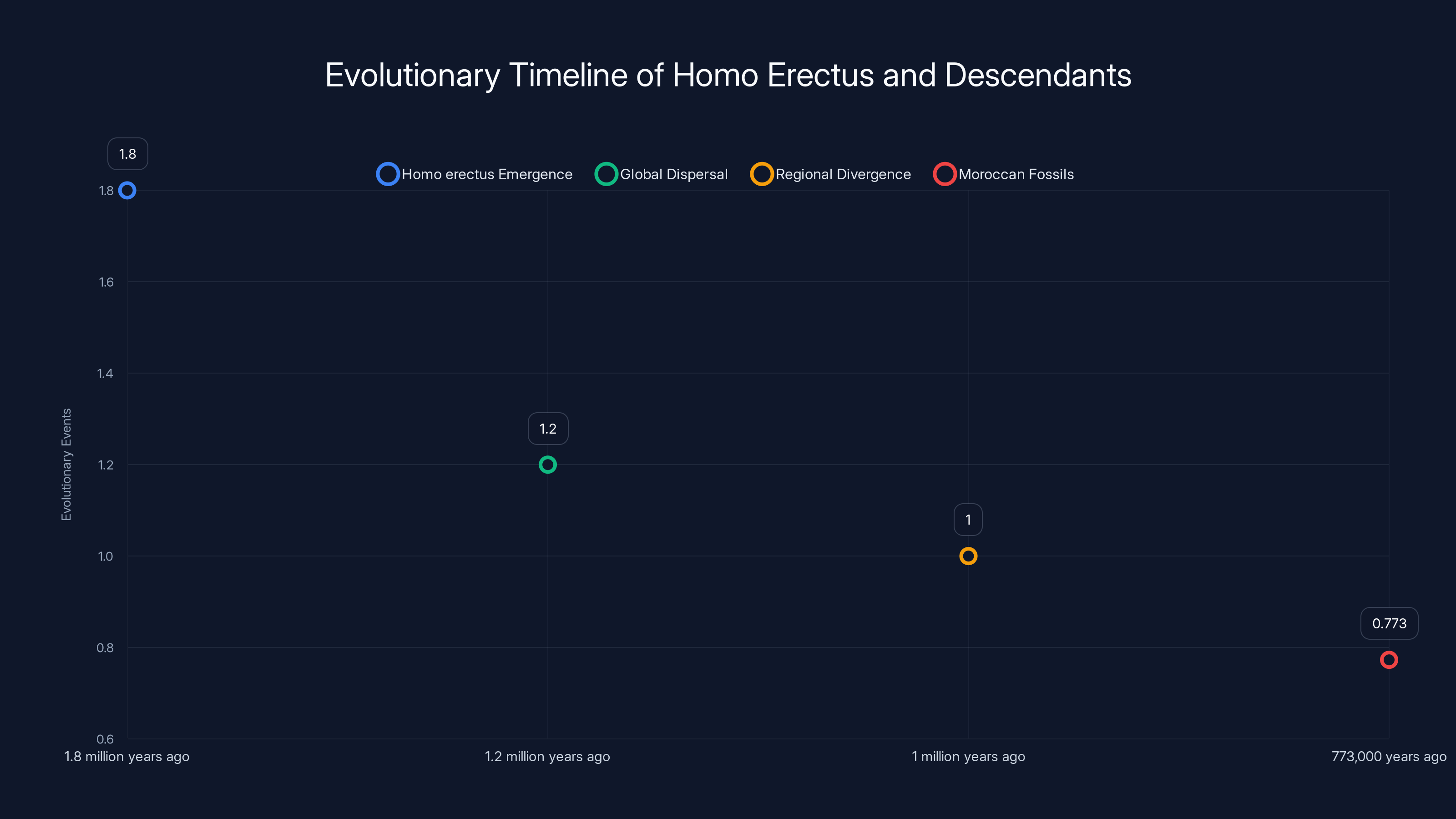

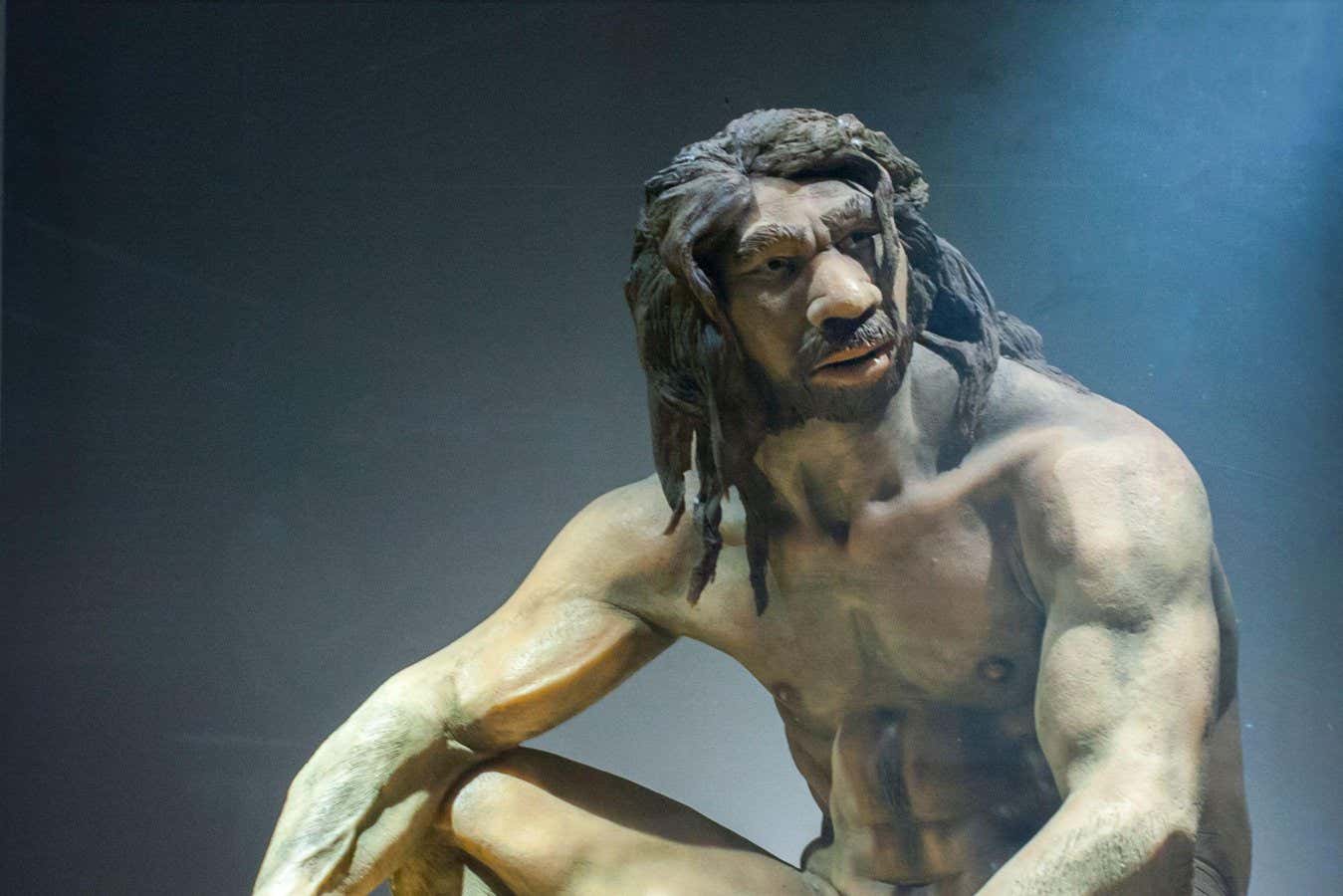

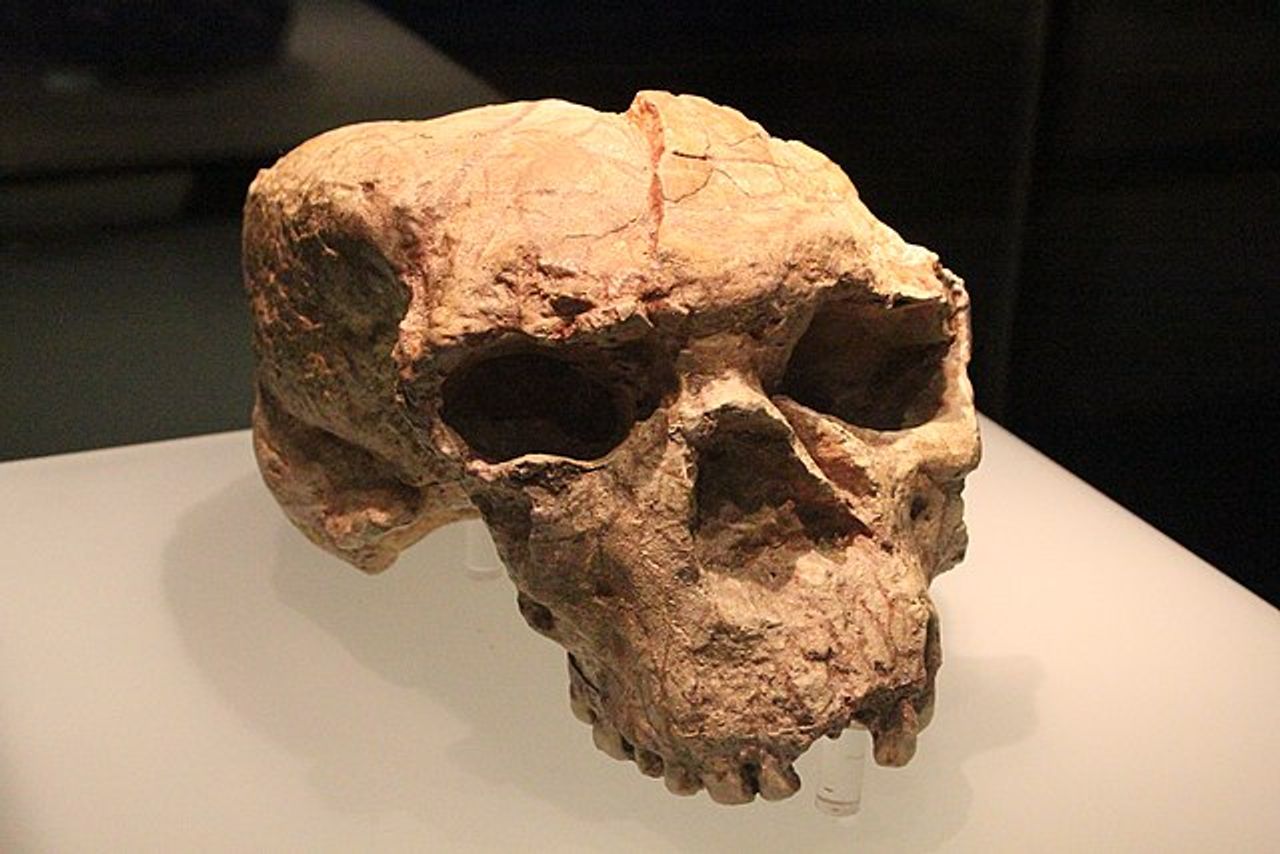

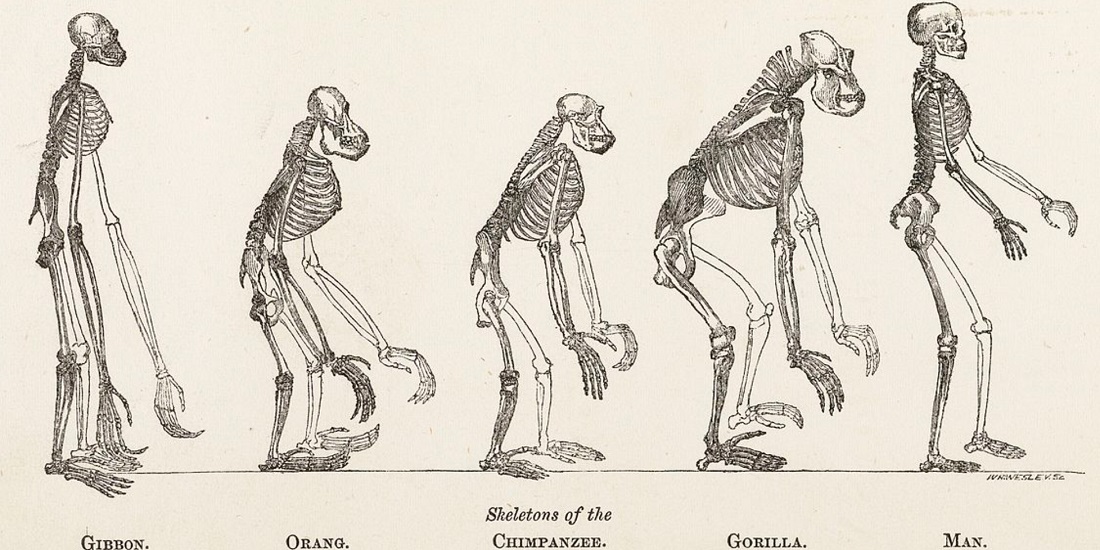

To understand why these 773,000-year-old Moroccan fossils are important, we need to zoom back and understand the larger evolutionary context. About 1.8 million years ago, a species called Homo erectus emerged in Africa. This was a significant evolutionary milestone. Homo erectus had larger brains than its predecessors, more sophisticated tool-making abilities, and the ability to walk with a bipedal gait that was becoming increasingly human-like.

More importantly for our story, Homo erectus was a wanderer. Unlike earlier human ancestors that stayed in Africa, Homo erectus populations spread across the world. They moved into Europe, into Asia, into the Middle East. By 1.2 million years ago, Homo erectus fossils show up in Spain, in China, in Java. For the first time in human history, a human ancestor wasn't confined to a single continent.

But here's where geography and evolution started interacting in complex ways. Once populations of Homo erectus were spread across different continents, separated by vast distances and challenging environments, they began evolving differently. Populations in Southeast Asia evolved in their own directions. Populations in Europe faced their own environmental pressures and selective forces. Populations remaining in Africa continued their own evolutionary journey.

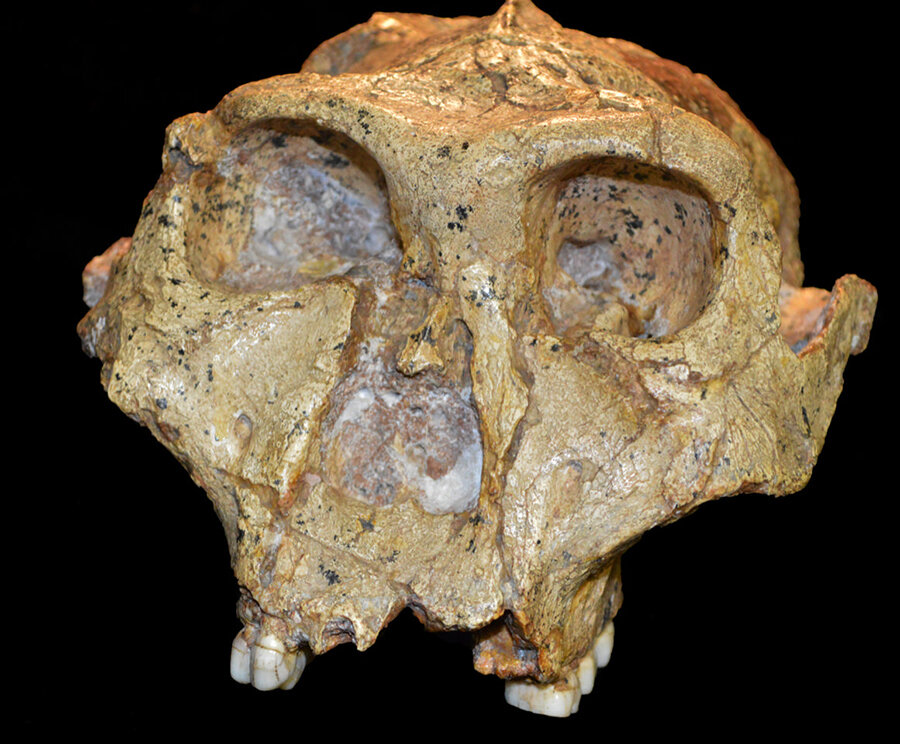

Around a million years ago, this regional divergence began producing distinct species. In Southeast Asia, isolation led to the evolution of Homo floresiensis, a smaller hominin species sometimes called the "Hobbit" due to its reduced body size. Homo luzonensis, discovered in the Philippines, represents another branch of this Asian radiation. In Europe, Homo erectus populations were beginning to show the features that would eventually characterize Homo antecessor and later Neanderthals. And in Africa, the populations that remained there were beginning the slow process of becoming us.

The Critical Split: 765,000 to 550,000 Years Ago

Somewhere in this ocean of time, a crucial split occurred. The lineage that would eventually produce Homo sapiens (modern humans) diverged from the lineage that would produce Neanderthals and Denisovans. This wasn't a sudden event, no dramatic moment where one species transformed into another overnight. It was a gradual splitting apart of populations, a slow accumulation of genetic differences, a drift in different evolutionary directions.

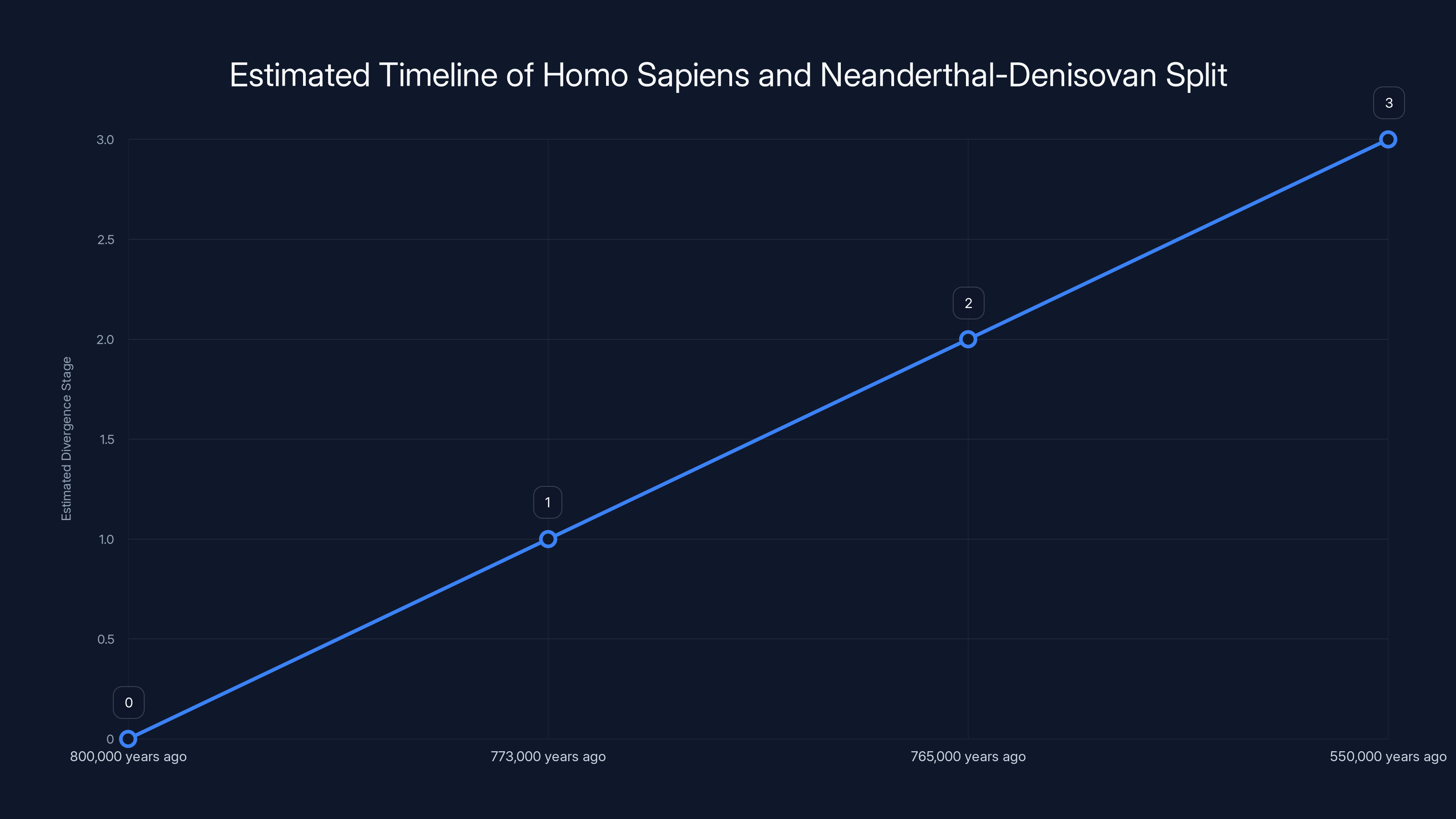

Genetic evidence suggests this split occurred sometime between 765,000 and 550,000 years ago. That's a window of 215,000 years, which sounds precise until you realize we're talking about events occurring when modern humans didn't exist, recorded in DNA molecules that have been degraded and reconstructed through molecular techniques developed only in the last few decades.

The problem with this dating is that it relies on genetic methods alone. We don't have fossils of the actual last common ancestor, the individual or population that represents the point of divergence. We don't have physical evidence of the morphological changes that accompanied this split. We're inferring from the genomes of Neanderthals and Denisovans (recovered from ancient DNA) and modern humans what the timing of divergence must have been. It's like trying to reconstruct a family tree using only DNA, without any photographs or documents.

This is where the Moroccan fossils become crucial. At 773,000 years old, they're dated to precisely the period when genetic evidence suggests this split was occurring or about to occur. If these fossils represent the lineage that would eventually become Homo sapiens, they're incredibly close to the root of that branch. They're not the last common ancestor, but they might be only a few hundred thousand years removed from it.

Neanderthals and Denisovans: Diverging European and Asian Paths

While African populations were continuing their evolutionary journey toward modern humans, populations in Europe and Asia were taking their own paths. The Neanderthals, emerging in Europe and western Asia around 400,000 years ago, adapted to the challenging Ice Age climates of the Eurasian continent. Their stocky build, large brains, and sophisticated hunting strategies represented an evolutionary solution to survival in cold environments.

Denisovans are more mysterious because we have fewer fossils of them. We know they existed in Asia, particularly in Siberia and Southeast Asia, because of recovered ancient DNA. We know they survived into relatively recent times, because Denisovan DNA is found in modern populations, particularly in Oceania and Southeast Asia. A single molar tooth and some finger bone fragments are among the only physical remains we have of them, yet genetic analysis reveals that Denisovans had already undergone substantial evolutionary change by the time the oldest recovered Denisovan DNA samples were created, around 30,000 years ago.

Based on ancient DNA analysis, Neanderthals and Denisovans themselves didn't split from each other until sometime between 470,000 and 430,000 years ago. This means that for perhaps 300,000 years or more, the lineages leading to Neanderthals and Denisovans remained together as a single population or closely related group of populations before geographic separation drove them apart.

Meanwhile, in Africa, the lineage leading to Homo sapiens was undergoing its own transformations. Our species, Homo sapiens, didn't suddenly appear fully formed. Fossils suggest a gradual emergence of recognizable modern human characteristics, with the earliest clear evidence of our species dating to around 300,000 years ago, or possibly earlier depending on how you define "modern human."

This timeline illustrates key evolutionary events of Homo erectus and its descendants, highlighting the global dispersal and regional divergence that led to distinct species. Estimated data based on fossil records.

North Africa: An Overlooked Evolutionary Laboratory

The Importance of African Fossils

For decades, the dominant narrative in human evolutionary studies focused heavily on European evidence. Neanderthal fossils are relatively abundant in Europe. The fossil record of early humans in Europe is reasonably well-documented compared to many parts of the world. Naturally, European scientists studying their own fossil heritage and colleagues worldwide working with accessible European specimens built detailed knowledge of European evolutionary history.

But this created a bias. The story of human origins became, in some ways, a European story. The narrative suggested that the critical evolutionary innovations that created modern humans happened elsewhere, or that Africa was simply a source population with less sophisticated evolution happening there. Meanwhile, Europe was where the important adaptive radiation was occurring, where new species were evolving, where the action was.

The reality is messier and more interesting. Africa is vast. Africa has diverse environments and climates. Africa had multiple hominin populations living in different regions, facing different selective pressures, developing different adaptations. Yet African fossils from this crucial period are relatively rare. Sediments aren't always preserved well. Bones don't always survive. Archaeological work is more difficult, less funded, less studied.

The Moroccan discovery challenges this bias. Here we have evidence that North Africa was not a peripheral backwater in human evolution. It was an active site of evolutionary change, with hominins living and adapting to their environment. These weren't isolated populations; they were part of a larger African population structure that was generating the diversity that would eventually produce modern humans.

Comparing North African and European Populations

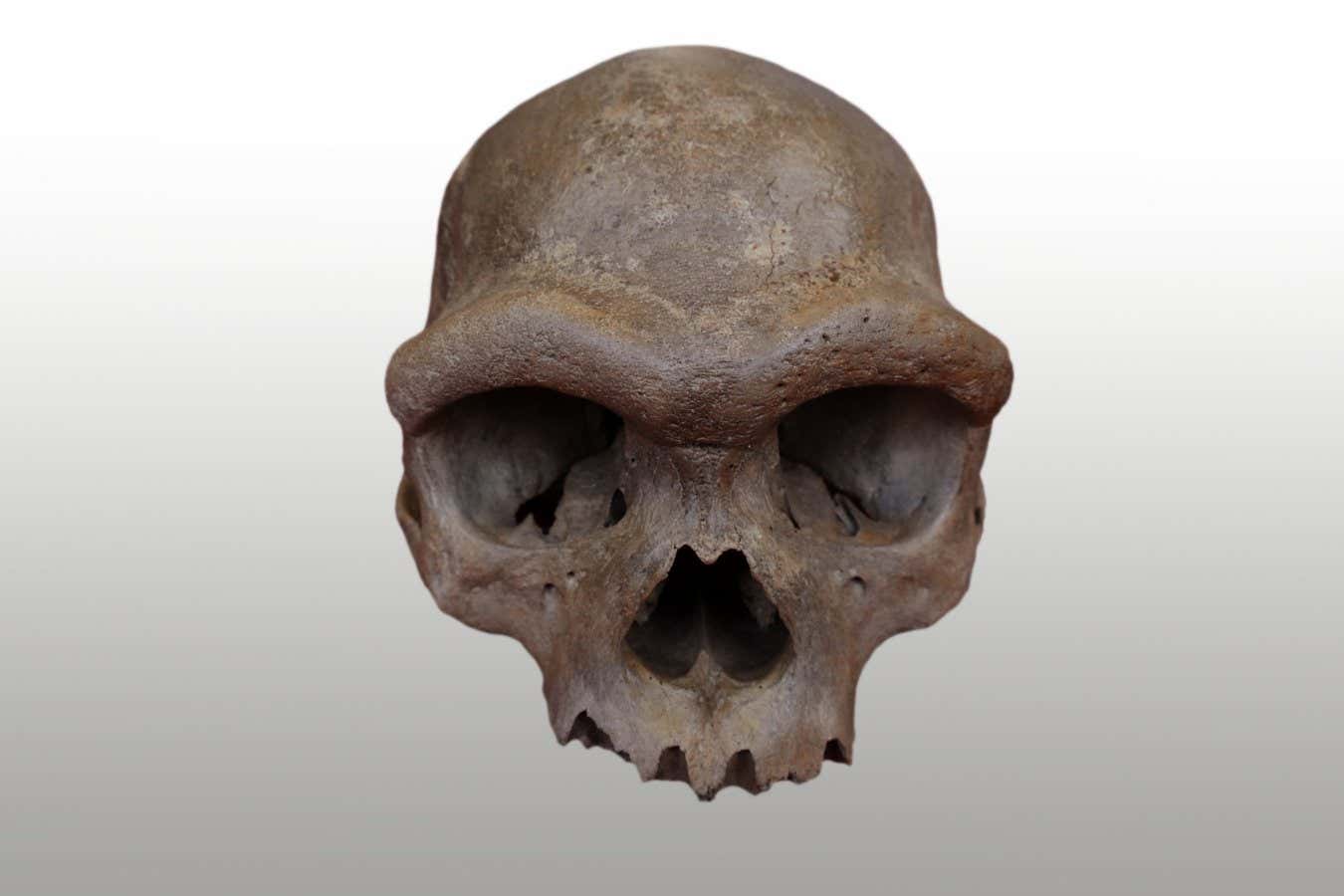

Here's where the analysis gets particularly interesting. The Moroccan fossils are roughly the same age as Homo antecessor from Spain. Homo antecessor is often proposed as a likely ancestor of Neanderthals and Denisovans, representing the population or species that gave rise to those later European and Asian hominins.

When researchers compared the Moroccan fossils to Homo antecessor and to other hominin species, a striking pattern emerged. Both groups share certain features: characteristics in their teeth and lower jaws that link them to their Homo erectus heritage. Both show some of the same adaptations and anatomical solutions to common problems.

But they also differ in important ways. The Moroccan hominins retain certain primitive features, particularly in their chins and certain aspects of their teeth structure. They're showing some novel features in their jaws, particularly in the areas where chewing muscles attached, but they're missing some of the more advanced features that would later define Neanderthals.

The picture that emerges is of two populations that had already been separated for some time, diverging along different evolutionary trajectories. The Spanish Homo antecessor was evolving in directions that would eventually lead to Neanderthals. The Moroccan population was evolving in a different direction, one that would eventually lead to modern humans. Yet at 773,000 years ago, this divergence was still relatively recent. These populations hadn't had hundreds of thousands of years to accumulate vast genetic and morphological differences. They were in the early stages of becoming distinctly different species.

Morphological Analysis: What the Bones Tell Us

Geometric Morphometry and Digital Comparison

Comparing ancient fossils might sound straightforward: put them side by side and look at the differences. But this approach is subjective and limited. Modern paleontology uses quantitative methods that remove human bias and allow for statistical analysis of shape differences.

Geometric morphometry involves identifying specific landmarks on bones and teeth. A landmark might be the point where three anatomical features meet, or the apex of a cusp on a tooth, or any reproducible anatomical point that can be identified on multiple specimens. Once these landmarks are identified, they can be recorded as three-dimensional coordinates. Different species or populations will have different patterns of landmark distribution reflecting their evolutionary history.

The Moroccan fossils and comparison specimens were analyzed this way. Researchers identified landmarks on the jawbones, analyzed the three-dimensional shape of teeth, examined the angles at which muscle attachment points were oriented. Each of these measurements produced data that could be subjected to statistical analysis.

The results revealed something nuanced. The Moroccan fossils weren't identical to Homo erectus, but they retained many Homo erectus-like features. They showed some similarities to later modern human anatomy, but lacked many definitive modern human characteristics. They had some features suggesting relationship to Neanderthals, but were clearly not on the Neanderthal evolutionary trajectory. They were, in essence, an intermediate form: later Homo erectus that was beginning to evolve in the direction of modern humans, but hadn't yet become our species.

Dental Features and Evolutionary Relationships

Teeth are among the most informative parts of the skeleton for evolutionary studies. They preserve well in fossils, they have many anatomical features that vary between species, and they're particularly sensitive to evolutionary change because chewing demands can drive rapid adaptation.

The Moroccan hominin teeth showed an interesting mosaic of features. Some characteristics—the overall size and shape, the structure of the cusps, the pattern of ridges and grooves—retained the general pattern seen in Homo erectus. Other features, particularly in how the roots were structured and how the enamel was distributed, showed hints of the direction evolution was moving toward modern humans.

Crucially, the teeth were missing some features that would later become characteristic of Neanderthals. Neanderthals developed distinctive dental features related to their powerful bite and the way they used their teeth as tools. The Moroccan fossils don't show these incipient Neanderthal features, suggesting they were not on the Neanderthal evolutionary path.

This pattern repeats across different anatomical systems. The jawbones show a mix of ancestral features from Homo erectus and novel features that would later characterize modern humans. The vertebrae show adaptations consistent with the kind of posture and movement we'd expect from advanced hominins. Every feature tells a story of a population in transition, beginning to move in new evolutionary directions but not yet arrived at their eventual destination.

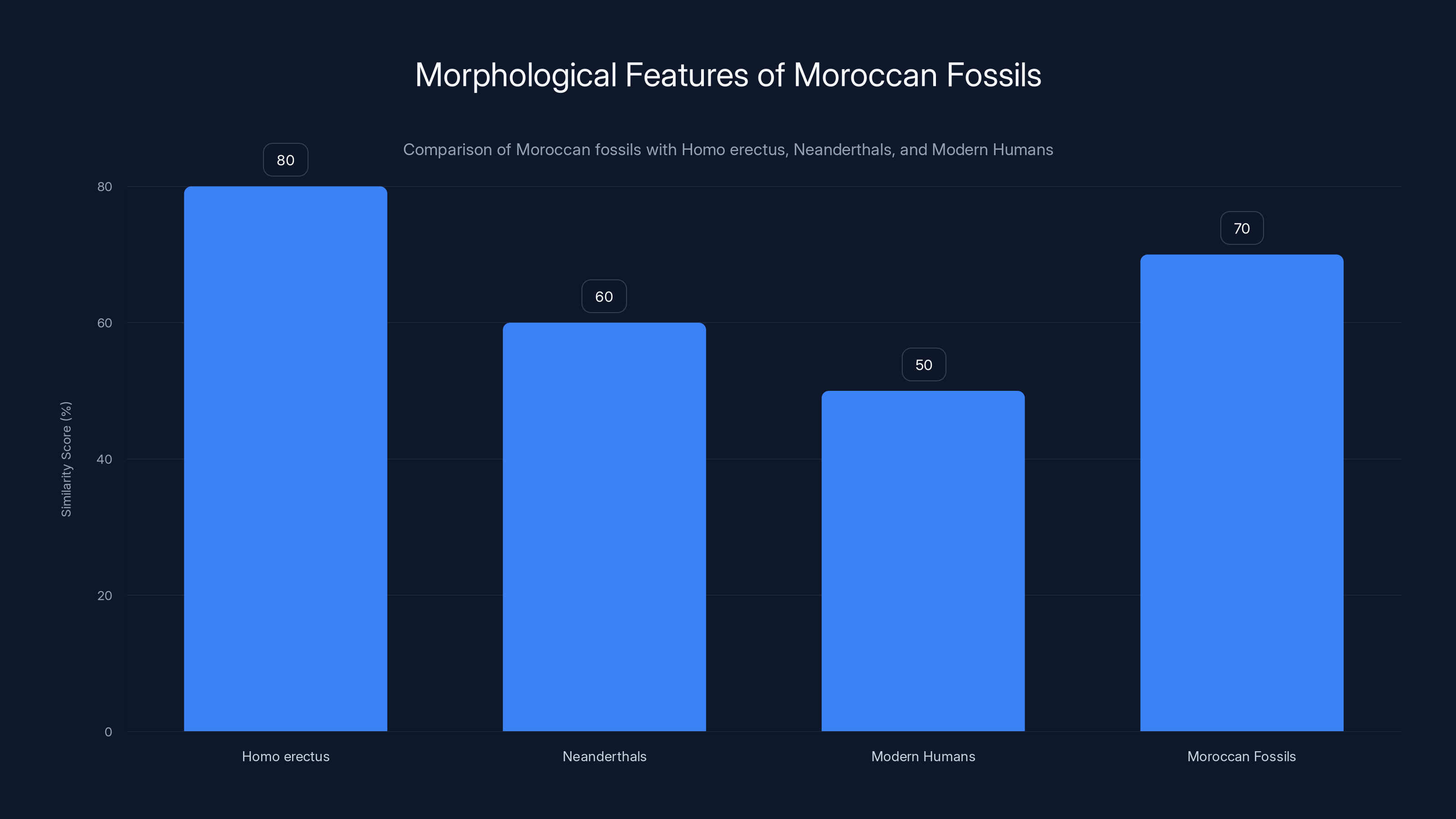

The Moroccan fossils show a high similarity to Homo erectus, indicating an intermediate evolutionary form. Estimated data.

Dating the Great Split: Implications for Human Origins

Reconciling Fossil and Genetic Evidence

One of the most important contributions of the Moroccan discovery is potentially refining our understanding of when the Homo sapiens lineage actually split from the Neanderthal-Denisovan lineage. Genetic evidence pointed to a window of 765,000 to 550,000 years ago. But genetic dates often come with uncertainty. This window is based on mutation rates that are themselves estimates, and there's ongoing debate about the best rates to use.

The Moroccan fossils, at 773,000 years old, sit right at the upper boundary of this genetic window. If these fossils represent the Homo sapiens lineage—which the morphological evidence suggests they do—then the split between our ancestors and the Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestors might have occurred even earlier than genetic estimates suggested. It might have occurred close to 800,000 years ago.

Alternatively, these fossils might represent the last common ancestor of all three lineages, or a population that hadn't yet undergone the split. The reality is probably more complex than simple branching diagrams suggest. Evolutionary divergence is a process that plays out over thousands of years. Populations don't split instantaneously. Instead, geographic isolation gradually increases, gene flow decreases, and populations accumulate different mutations and adaptations. During the period when this splitting was occurring, you might have populations that were intermediate between the ancestral state and the full divergence.

Regardless of the exact interpretation, the Moroccan fossils demonstrate that Africa was a site of significant hominin evolution during this critical period. They suggest that the evolution of modern humans wasn't a simple, linear process starting from a single ancestral population. Instead, it involved geographically distributed populations evolving in response to local conditions, maintaining gene flow across continents, and gradually differentiating into distinct lineages.

Refinement of Evolutionary Timescales

The presence of well-dated fossils from Africa around the time of the proposed split has important implications for refining our evolutionary timescales. Each fossil discovery provides a new data point. Scientists can compare the morphology of fossils to the genetic divergence times suggested by molecular data. When multiple lines of evidence converge—fossil morphology, dating evidence, genetic data—we gain confidence in our understanding of when events occurred.

The Moroccan fossils suggest that the split between Homo sapiens' ancestors and the Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestors probably occurred closer to 800,000 years ago than to 550,000 years ago. This is still in the window that genetic evidence suggested, but it pushes the event toward the earlier end of the range. With more fossil discoveries, this estimate might be further refined.

It's worth noting that these are minimum ages for the split. The actual last common ancestor might have lived earlier than 773,000 years ago. These Moroccan fossils, if they represent our ancestors, lived after the split had already begun. The actual speciation event—the moment when populations diverged completely—might be invisible in the fossil record, a moment of gradual change that no single fossil captures.

Complex Interactions: More Than Just Divergence

Admixture and Genetic Introgression

One of the most surprising discoveries from ancient DNA research is that Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans didn't simply diverge and then stay separate. Instead, they came back into contact multiple times, and when they did, they interbred. This genetic introgression—the transfer of genes from one species or population into another through hybridization—left traces that are still visible in modern human genomes.

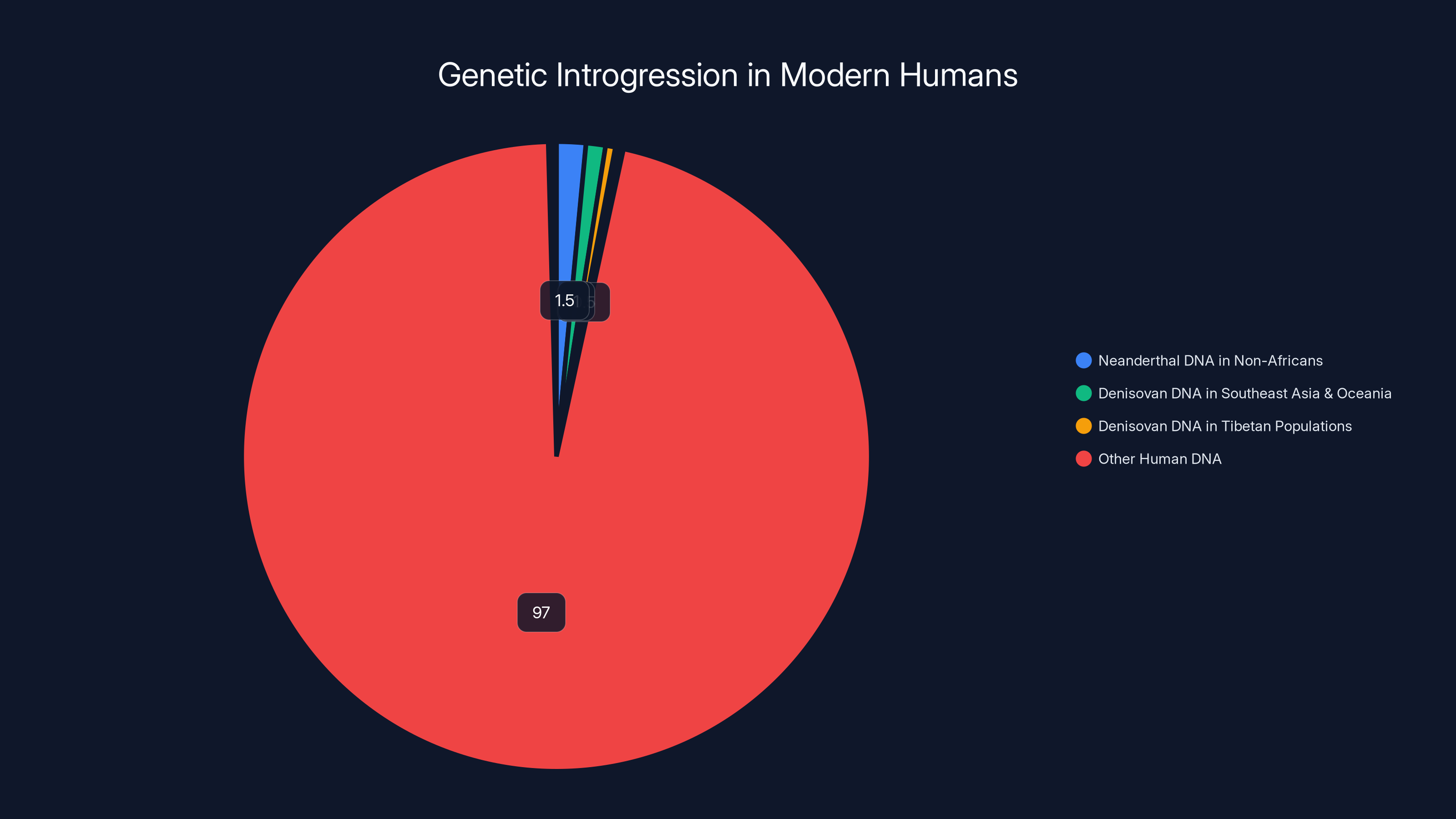

Every non-African modern human carries approximately 1-2% Neanderthal DNA in their genome. This wasn't from a recent event. These genes were incorporated into our ancestors sometime between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, when modern humans moving out of Africa came into contact with Neanderthals living in Europe and western Asia. Some of these Neanderthal genes were neutral, just along for the ride. But some appear to have been advantageous, helping modern humans adapt to new climates and diseases.

Denisovans tell a more complex story. Denisovan DNA appears in modern populations, particularly in Southeast Asia and Oceania, suggesting that modern humans coming into Asia interbred with Denisovans they encountered there. Some Denisovan genes appear to have been important for adapting to high altitudes, as suggested by the distribution of Denisovan genetic variants in Tibetan populations.

More surprisingly, ancient DNA from Neanderthals shows that Neanderthals themselves carried some Denisovan DNA. This indicates that Neanderthals and Denisovans, despite being geographically separated for hundreds of thousands of years, came back into contact at some point and interbred before the Neanderthals went extinct.

This paints a picture far more complex than the simple branching trees often used to illustrate evolutionary relationships. It suggests that hominins didn't evolve in isolated, sealed-off populations. Instead, they remained in loose contact with each other. Periodically, when geography shifted, climates changed, or populations migrated, different species would encounter each other. Sometimes they coexisted peacefully. Sometimes they competed. And sometimes they interbred, exchanging genes that would shape the evolutionary future of their descendants.

Implications for Understanding Modern Human Diversity

The discovery that modern humans carry Neanderthal and Denisovan genes has important implications for understanding human genetic diversity today. Some of the variation we see in human populations might reflect ancient admixture with other hominin species. Genes that help us resist certain diseases, or that affect how our bodies process food, or that influence our risk for various conditions, might have been acquired from Neanderthals or Denisovans thousands of years ago.

This also changes how we think about what it means to be human. We tend to think of species as sharply defined categories, but the reality of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans breeding together challenges that view. At what point did these separate species become "separate" if they could still produce fertile offspring? The answer is that speciation is a process, not an event. Populations gradually diverge, gradually accumulate differences, until at some point they can no longer produce fertile offspring together. But during the transitional period, they might remain partially compatible.

The Moroccan fossils at 773,000 years suggest the Homo sapiens lineage may have split from Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestors earlier than genetic estimates, possibly around 800,000 years ago. Estimated data.

Environmental Context and Adaptive Pressures

North African Climate and Ecology 773,000 Years Ago

Understanding fossils in their environmental context is crucial for interpreting what they tell us about evolution. At 773,000 years ago, North Africa was not the continuous Sahara Desert that covers much of the region today. The climate was more variable, with periods of greater rainfall supporting more extensive vegetation.

The cave system where these fossils were found reflects an environment that supported sizable animal populations. The presence of carnivore teeth marks on the hominin remains indicates the presence of large predators. The fossil assemblage from the same layers includes remains of various animal species that would have coexisted with these hominins. This wasn't a barren landscape; it was an active ecosystem with multiple species competing for resources.

The Moroccan hominins lived in this environment, hunting or scavenging animal meat, gathering plant foods, navigating the challenges of coexisting with large predators. The fact that at least some of their remains ended up in a carnivore's den suggests the danger was very real. Being human-like in intelligence and tool-making ability didn't make ancient hominins the apex predators of their environment. They remained vulnerable, particularly to large cats and other carnivores.

The environmental stability or variability at this time might have played a role in driving evolutionary change. Climate fluctuations in Africa have long been proposed as a driver of human evolution, with changing environments selecting for populations with greater behavioral flexibility, larger brains, and more sophisticated tool use. The Moroccan context provides an important data point for understanding what environments the ancestors of modern humans were evolving in.

Tool Technology and Behavioral Sophistication

Unfortunately, the fossil remains from Grotte à Hominidés don't directly tell us much about the tool technology of these hominins. No stone tools are definitively associated with these fossils in a way that allows clear attribution. However, the period around 773,000 years ago was characterized by increasingly sophisticated tool technology across Africa.

Homo erectus created Acheulean hand axes and other tools that persisted for nearly a million years with relatively little change. But by the time we reach 773,000 years ago, hominin tool technology was beginning to show variation and innovation in different regions. In Africa, tool kits were becoming more diverse, with different tool types serving different purposes. This suggests that the hominins making these tools had more sophisticated cognitive abilities, understanding the relationship between tool form and function in more nuanced ways.

The Moroccan hominins lived during this period of tool innovation. They were likely capable of making and using sophisticated stone tools. They were probably hunting large animals, either as primary predators or as scavengers of kills made by other predators. They were possibly working cooperatively in groups, planning hunts, and teaching younger generations how to make and use tools.

All of this represents the kind of behavioral sophistication that would eventually characterize modern humans. These weren't quite modern humans, but they were moving in that direction, developing the behavioral and cognitive flexibility that would allow their descendants to populate the entire world and develop complex societies.

The Bigger Picture: Africa's Role in Human Evolution

Africa as the Source and Laboratory

The Moroccan discovery reinforces a fundamental principle of human evolutionary biology: Africa is where modern humans evolved. This isn't a speculative statement; it's supported by fossil evidence, genetic evidence, and the fossil records of human cultural and technological development. Modern humans originated in Africa and subsequently dispersed to other continents, not the other way around.

But Africa's role in human evolution extends far beyond being a source population. Africa is where the early hominin lineage emerged millions of years ago. Africa is where Homo erectus first appeared. Africa is where the split between the modern human lineage and other hominin lineages occurred. Africa is where complex language, art, and culture first developed. Africa is where the fundamental adaptations that make us human were first tested by natural selection.

Yet African fossils from crucial periods remain sparse compared to what we have from Europe or Asia. This isn't because Africa has fewer ancient hominins buried in its rock record. It's because of funding disparities, because much of Africa's paleontological wealth lies in remote locations with difficult access, because infrastructure for excavation and research is unevenly distributed, and because of historical biases in which regions scientists focus on.

The Moroccan discovery demonstrates that more fossils are waiting to be found. With continued investment in African paleontology, with training of African scientists to lead research in their own regions, with attention to African sites, we will likely uncover more pieces of this puzzle. Each discovery refines our understanding of what was happening in Africa during these crucial periods when our species was emerging.

Changing the Narrative from Eurocentric to Polycentric

Historically, human evolutionary studies focused disproportionately on European fossils and European sites. This created a narrative in which Europe was the center of action, where the most important evolutionary innovations were occurring, where the fascinating hominin species were living. Africa, by contrast, was treated as peripheral—a source population perhaps, but not the location of exciting evolution.

The reality, increasingly documented by recent discoveries, is different. During the period around 773,000 years ago, Africa had at least one population of advanced hominins, and likely multiple populations living in different regions under different conditions. Europe had Homo antecessor and its descendants. Asia had various populations including the ancestors of Denisovans. These populations weren't all equal, and they weren't all moving in the same evolutionary direction.

By 500,000 years ago, Africa had more advanced hominins that we might call transitional between Homo erectus and modern Homo sapiens. Europe had Neanderthals, which had diverged substantially from African populations. Asia had Denisovans. Multiple evolutionary experiments were playing out simultaneously across different continents, each responding to local environmental pressures and developmental paths.

The Moroccan fossils fit into this increasingly nuanced picture. They show us that Africa wasn't a static place where nothing much happened while Europe and Asia got all the evolutionary excitement. Africa was where the future of humanity was being determined, where the traits and capabilities that would eventually characterize modern humans were being refined by natural selection.

Estimated data shows that non-African humans carry about 1.5% Neanderthal DNA, while Denisovan DNA is more prevalent in Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Tibetan populations. This highlights the complex interactions and genetic introgression among ancient human species.

Fossil Gaps and What They Mean

The Persistent Problem of Incomplete Evidence

Despite the importance of the Moroccan discovery, we should be honest about how much it doesn't tell us. We have jawbone fragments from three individuals. We have some teeth. We have some vertebrae. We have no complete skeleton. We have no skulls that would tell us about brain size and shape. We have no hand bones that would reveal tool-making capabilities. We have bones from a predator's den, fragmentary and scattered, pieces of a story that no single fossil can fully tell.

This is the fundamental challenge of paleontology. Fossils are rare. For every individual that was fossilized and preserved, countless others rotted away or were destroyed. For every fossil that was buried in conditions that allowed fossilization, thousands died in ways that left no trace. We're looking at an infinitesimally small sample of ancient populations, trying to reconstruct the history of entire species and continents.

The gaps in the fossil record are real and significant. Between the time of Homo erectus around a million years ago and the emergence of recognizable modern humans around 300,000 years ago, we have only scattered fossils. Some of these fossils are older, some are younger, some might represent different species or populations. But the gaps mean that for hundreds of thousands of years, we have almost no fossil evidence of what hominins looked like, how they were evolving, what selection pressures were acting on them.

The Moroccan fossils partially fill one of these gaps. But they also highlight how much we still don't know. We don't know if the population these three individuals belonged to survived for another 100,000 years and evolved into modern humans. We don't know if there were other populations with different characteristics living in different parts of Africa. We don't know exactly which African population was ancestral to modern humans, or if multiple populations contributed to our species.

The Importance of Continued Excavation and Discovery

Filling these gaps requires continued work. Paleontologists need to continue excavating sites in Africa, looking for more fossils from this crucial period. They need to develop new dating methods that can better pinpoint when fossils lived. They need to employ new molecular techniques to extract DNA from older fossils, understanding the genetic relationships between different hominin populations.

They also need to continue expanding the geographic scope of their work. Most famous hominin fossils come from a handful of well-known sites. But there are likely many more sites, particularly in Africa, that contain important fossils waiting to be discovered. Each new site potentially gives us a new geographic perspective on how hominin populations were distributed and how they were evolving.

Civilians can contribute to this work. Citizen science projects allow non-professionals to help process and analyze fossil data. Funding from private donors and scientific foundations supports paleontological work. Education about human evolution and the importance of fossil discovery helps build public support for ongoing research. The Moroccan discovery is exciting in part because it demonstrates that major discoveries continue to happen when resources are devoted to looking.

Ancient DNA and the Future of Understanding Hominin Evolution

What We Can Learn from Genetic Material

The Moroccan fossils are dated to 773,000 years ago, which is quite ancient. At this age, the preservation of ancient DNA becomes challenging. DNA degrades over time, chemically damaged by water, heat, and microbial action. The older the fossil, the less likely it is to contain recoverable DNA. Neanderthal DNA has been successfully extracted from fossils less than 100,000 years old. Extracting DNA from the Moroccan fossils, at 773,000 years old, would be extraordinarily difficult and might be impossible.

But techniques are improving. Scientists have recently extracted DNA from much older fossils, pushing back the time limit for DNA recovery. If DNA can be extracted from the Moroccan fossils or from other fossils of similar age, it would provide direct insight into the genetic makeup of the population from which modern humans evolved. We could see exactly which genes were present in our ancestors at this point in their evolution. We could identify mutations that occurred after this time that characterize modern humans. We could directly compare the genetics of the Moroccan population to Neanderthals and Denisovans, understanding exactly how they were related.

Even without DNA from the Moroccan fossils themselves, scientists are working on extracting DNA from other fossils dating from this period and nearby periods. Each new genome from an ancient hominin provides more information about population structure, migration patterns, and evolutionary relationships. The ancient DNA revolution in paleontology has transformed our understanding of human evolution in ways that seemed impossible just two decades ago.

Genomics and Population Reconstruction

Another frontier in understanding these ancient populations involves genomic techniques. By analyzing the DNA of modern populations, scientists can reconstruct the evolutionary history of human populations, identifying points where populations split, where they came back together, where genetic material was exchanged. These "population genomic" analyses have revealed previously unknown migrations, previously undetected admixture, and previously hidden population structure in human evolutionary history.

Applied to ancient hominin genomes, these techniques become even more powerful. We could potentially determine how many separate populations existed 773,000 years ago, how closely related they were, what degree of gene flow occurred between them. We could reconstruct ancient population sizes, identify bottlenecks when populations became very small, and understand which populations were stable and which were expanding or contracting.

This kind of detailed understanding of population history would allow us to connect fossils to specific populations and understand their relationship to our own evolutionary history. The Moroccan fossils could potentially be placed within a detailed map of African hominin populations at this time, allowing us to see not just what these individuals looked like, but where they fit into a larger population structure and evolutionary landscape.

Competing Interpretations and Scientific Debate

Alternative Explanations and Their Merits

While the interpretation of the Moroccan fossils as representing early members of the Homo sapiens lineage is supported by the morphological evidence, alternative interpretations deserve consideration. One possibility is that these fossils represent Homo rhodesiensis, another species that lived in Africa during this period and has sometimes been proposed as ancestral to modern humans.

Homo rhodesiensis has sometimes been treated as synonymous with African Homo erectus, sometimes as a separate species. The classification of early African hominins from this period can be debated, with different scientists preferring different taxonomic frameworks. The Moroccan fossils could be Homo rhodesiensis, or a late form of Homo erectus, or members of a population that was becoming transitional between those categories and modern Homo sapiens.

Another possibility is that these fossils represent a population that was geographically isolated and somewhat divergent from the main lineage leading to modern humans. They might have become extinct without directly contributing to our species. In this case, they would be interesting as examples of human evolution in action, but not as direct ancestors of modern humans.

These alternative interpretations highlight an important point: fossil interpretation involves inference and judgment. When you have incomplete remains, when you're trying to place them on a family tree millions of years in the past, when the boundary between species is itself somewhat arbitrary, reasonable scientists can disagree about what the evidence means.

What's important is that the debate is grounded in data and methodology. The geometric morphometry analysis provides a quantitative framework for comparing the Moroccan fossils to other hominin species. The dating is based on multiple methods, providing confidence in the age estimate. The context, including the environment and the presence of carnivore activity, provides additional interpretive information. All of this allows scientists to debate the meaning of the evidence within a framework of rigorous methodology.

Ongoing Scientific Questions

The Moroccan discovery doesn't close the book on human evolution. Instead, it opens new questions. If these fossils represent the Homo sapiens lineage, what happened to this population after 773,000 years ago? Did it continue evolving into later forms of Homo sapiens? Did it go extinct and get replaced by a different population? Did multiple populations contribute to the ancestry of modern humans?

How much gene flow occurred between the African population(s) and the European Homo antecessor population? The similar age and the fact that both populations were probably part of a larger human species (or closely related species) suggests some possibility of contact or shared ancestry. But the morphological differences suggest they had been separated for some time. Understanding the degree of genetic connection between these populations would help clarify the evolutionary relationships.

What about other African populations during this time? Were the Moroccan hominins representative of all African populations, or were there significant regional variation? Did different African regions have different hominin species? Understanding African diversity is crucial for understanding which population ultimately gave rise to modern humans.

These questions drive ongoing research. They motivate paleontologists to continue excavating, seeking more fossils, more evidence. They inspire molecular biologists to work on extracting ancient DNA and ancient proteins from fossils. They encourage geologists to develop better dating methods that can narrow down the ages of fossils more precisely. The Moroccan discovery is important not as a final answer, but as a key piece of evidence that points toward new understanding.

What This Means for Understanding Modern Humanity

Our Deep Evolutionary Heritage

Humans like to think of ourselves as fundamentally different from all other animals, separated by an unbridgeable gulf. We're intelligent, we create art, we have complex languages, we ponder our own existence. These are genuinely remarkable traits. But they didn't appear overnight. They evolved gradually, through countless small steps, each step building on previous adaptations, each generation slightly different from its ancestors.

The Moroccan fossils remind us that this process of becoming human took an enormously long time. The hominins represented by these jawbones were already quite sophisticated. They had large brains for their time. They were making stone tools. They were hunting large animals. They were living in groups and cooperating with each other. They had intelligence and perception and the ability to plan and learn.

But they weren't us. Their brains were smaller than ours. Their tools, while sophisticated, were simpler than what later humans would make. Their art and language, if they had any, are invisible to us in the fossil record. They were way stations on a long evolutionary path, closer to us than their predecessors, but still distant from what modern humans would become.

Understanding this deep heritage is important for how we see ourselves. We're the products of millions of years of evolution, adaptation, and survival in challenging environments. We carry within our bodies the traces of millions of years of evolutionary history. The genes we have, the physiological systems we rely on, the instincts and drives that motivate us—all of these were shaped by natural selection in ancient environments very different from the modern world.

Evolutionary Success and Contingency

Another lesson from the Moroccan fossils and the broader history of hominin evolution is that success in evolution depends partly on luck. The lineage that led to modern humans survived and thrived. But so did many other hominin lineages. Neanderthals, despite being extinct today, were a successful species for hundreds of thousands of years. Denisovans survived for even longer and contributed genes to modern human populations. Homo floresiensis lived on an isolated island for tens of thousands of years, a successful adaptation to an unusual environment.

The fact that modern humans are here, reading about fossil jaws and evolutionary splits, while Neanderthals and other hominins are extinct, isn't necessarily because we were "better" in any moral sense. It's partly because of luck. We happened to evolve in Africa at a time when Africa was experiencing favorable conditions. We happened to develop the cognitive and behavioral traits that allowed us to survive and adapt to changing environments. We happened to migrate out of Africa at a moment when we had the capabilities to survive in new environments. We happened to encounter Neanderthals at a time when we had a numerical or technological advantage.

Evolution is full of contingency. Small changes in environmental conditions, small differences in which mutations happen to arise, small variations in when populations come into contact—all of these can determine which species survives and which goes extinct. The Moroccan hominins were successful for their time, but their lineage didn't lead to us if they were on a side branch that went extinct. They might have been successful in their immediate environment but poorly adapted to global climate change. They might have been unlucky enough to be in the wrong place when a volcanic eruption or other catastrophe reduced their population.

Implications for Paleoanthropology and Research Methods

The Value of Non-Destructive Imaging

The analysis of the Moroccan fossils demonstrates the importance of modern paleontological techniques. Micro-CT imaging allowed scientists to examine the fossils in extraordinary detail without damaging them. The digital models created from these images can be studied, rotated, and measured in ways that would be impossible with physical specimens. They can be shared with collaborating scientists around the world without moving the actual fossils. They provide a permanent record of the fossils as they appeared at the time of study, useful for future scientists to re-examine if new questions arise or new analytical techniques are developed.

This revolution in paleontological methods has enabled discoveries that would have been impossible in earlier decades. Scientists can now use computational techniques to analyze shapes and relationships that are too complex for human intuition. They can perform statistical analyses that provide quantitative support for comparisons between fossils. They can generate hypotheses about evolutionary relationships that can be tested across many specimens.

These advances in technology are democratizing paleontology in some ways. Scientists without access to famous fossil museums can still study high-quality digital models of specimens. Researchers in developing countries can collaborate on world-class projects using shared digital fossils. The knowledge bottleneck created by having unique, irreplaceable fossils sitting in specific museums in specific countries is gradually breaking down.

International Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing

The Moroccan research involved scientists from the Max Planck Institute in Germany, collaborating with Moroccan colleagues and paleontologists from institutions around the world. This kind of international collaboration is increasingly important for paleontological research. Complex evolutionary questions require diverse expertise: anatomists, paleontologists, geologists, geneticists, statisticians, computer scientists. No single institution has all the expertise needed.

Moreover, fossils belong to the countries where they're found. It's increasingly recognized that paleontological research should involve scientists from the country of origin, should train local scientists, and should contribute to building paleontological expertise and institutions in the regions where fossils are discovered. The Moroccan discovery represents this kind of collaborative research at its best: international expertise combined with local knowledge and investment in building local capacity.

This approach benefits science. Local scientists understand the geological and environmental context of fossil sites better than researchers parachuting in from abroad. They can supervise excavations, maintain fossil collections, and continue research long-term. They can train students and build institutions for long-term paleontological work. International collaboration allows resources and expertise to be shared, accelerating progress and building a global scientific community.

FAQ

What are the Moroccan fossils and why are they important?

The Moroccan fossils are 773,000-year-old jawbone fragments, teeth, and vertebrae discovered near Casablanca in Morocco. They're important because they provide direct fossil evidence from a time period when Homo sapiens' ancestors were splitting away from the ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans, helping us understand how and when this crucial evolutionary divergence occurred.

How do scientists determine the age of fossils like these?

The Moroccan fossils were dated using a geomagnetic reversal event that occurred approximately 773,000 years ago. The sediment layer containing the fossils spans a few thousand years around this magnetic reversal, which provides a reliable dating marker. Scientists use multiple dating methods to confirm fossil ages, including radiometric dating and analysis of surrounding geological features.

What do the fossil features tell us about evolutionary relationships?

Using a technique called geometric morphometry, scientists analyzed the shapes of jawbones, teeth, and other features to compare these fossils to other hominin species. The analysis revealed that the Moroccan hominins retained some primitive features characteristic of Homo erectus but also showed novel features moving in the direction of modern Homo sapiens, suggesting they were in the transitional period between these forms.

Were these fossils definitely ancestors of modern humans?

The fossil evidence suggests these hominins were very close to the ancestors of modern humans, living right around the time of the split between the Homo sapiens lineage and the Neanderthal-Denisovan lineage. However, with fragmentary remains, we can't be absolutely certain these specific individuals were direct ancestors. They might have been side branches or collateral relatives that eventually went extinct. They represent a population that was part of the ancestral lineage leading to modern humans.

How do fossil discoveries change our understanding of human evolution?

Each fossil discovery provides new data about what hominin species looked like, when they lived, where they lived, and what environments they inhabited. Fossils help ground evolutionary theories in physical evidence and allow scientists to test hypotheses about evolutionary relationships. The Moroccan fossils help fill a gap in the fossil record and suggest that Africa was a major site of evolutionary innovation during the period when modern humans were emerging.

What other fossil discoveries are helping us understand human origins?

Many recent discoveries are contributing to our understanding of human evolution. These include fossils of Homo floresiensis in Indonesia, Homo naledi in South Africa, various specimens of Homo antecessor in Spain, and improved fossils and dating of Neanderthals and Denisovans across Europe and Asia. Each discovery adds a new piece to the puzzle of how humans evolved and diversified.

Can we extract DNA from 773,000-year-old fossils?

Extracting DNA from fossils this old is extremely difficult and might be impossible. DNA degrades over time and is only rarely preserved in fossils older than 100,000 years or so. However, techniques are improving, and scientists continue to work on pushing back the limits of DNA preservation and recovery. If DNA could be extracted from the Moroccan fossils, it would provide extraordinary insights into the genetics of our ancestors.

How do Moroccan hominins compare to contemporary European Homo antecessor?

The Moroccan hominins and European Homo antecessor lived at about the same time (both around 773,000 years ago or similar timeframes). Both show a mixture of primitive features inherited from Homo erectus and more advanced features. However, they differ in important ways: the European Homo antecessor shows some features pointing toward Neanderthals, while the Moroccan hominins show features pointing toward modern humans, suggesting they were already on diverging evolutionary paths.

Why is Africa so important for understanding human evolution?

Africa is where human evolution occurred. Modern humans originated in Africa and subsequently spread to other continents. The fossil record shows that Homo erectus emerged in Africa, that the ancestral species for modern humans evolved in Africa, and that the behavioral and technological innovations characterizing modern humans developed in Africa. Finding more African fossils from crucial evolutionary periods helps us understand this history more completely.

What does this discovery tell us about when Neanderthals and Denisovans split from modern human ancestors?

The Moroccan fossils, dated to 773,000 years ago and interpreted as very close to the Homo sapiens lineage, suggest that the split between our ancestors and the Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestors occurred around 800,000 years ago or possibly slightly earlier. This aligns with and potentially refines genetic estimates that suggested this split occurred between 765,000 and 550,000 years ago, pushing toward the earlier end of that range.

How does this discovery affect our understanding of human migration and dispersal?

The Moroccan fossils demonstrate that Africa had multiple populations of advanced hominins at the same time that Europe had Homo antecessor and Asia had other hominin populations. This suggests that human evolution involved geographically distributed populations evolving in somewhat different directions. Understanding these regional populations helps us reconstruct how human populations subsequently dispersed from Africa and adapted to new environments around the world.

Conclusion: A Glimpse Into the Deep Past

Holding the concept of 773,000 years in your mind is genuinely difficult. That's not ancient in the sense that we use the word for historical periods measured in thousands of years. That's incomprehensibly ancient, a moment so distant that the modern world wouldn't be recognizable to anyone living then. The continents were in nearly the same positions they are today, but the world was nonetheless fundamentally different: different climate, different animal species, different plants, different human species.

The fossils from Morocco represent three individuals whose moment in time we can now touch across the vast gulf of geology and evolution. They weren't our ancestors, necessarily, but they were from the population that was ancestral to us. They lived during one of the most significant moments in our evolutionary history, when our lineage was beginning its path away from the lineages that would produce Neanderthals and Denisovans. They were caught at a transitional moment, already more advanced than their predecessors, but not yet become what we would become.

The broader lesson from this discovery is profound. We are the products of an enormously long evolutionary journey. The traits and capabilities that make us human didn't arrive all at once. They accumulated slowly, through countless small changes, each one tested by natural selection in ancient environments. The Moroccan fossils show us one step on this journey, hominins that had already traveled far from our earliest ancestors but still had far to go.

They also remind us that the story of human origins isn't a simple narrative. It's a complex story involving multiple populations, multiple species, continental dispersals, adaptations to different environments, and occasional admixture between diverging lineages. It's a story that continues to be written as paleontologists, geneticists, and other scientists continue to discover new evidence and develop new methods to interpret that evidence.

The Moroccan fossils have answered some questions about our evolutionary history. But they've also highlighted how much remains unknown. More fossils are waiting to be discovered, more genetic information is waiting to be extracted, more analysis is waiting to be done. Each new discovery will add nuance to our understanding of who we are and where we came from. The Moroccan jaw fragments, fragmentary as they are, represent not an endpoint in our understanding of human evolution but a waypoint on a journey that will continue for decades to come.

In studying these ancient bones, we're not just cataloging evolutionary history. We're understanding ourselves: our potential, our limitations, the deep heritage we carry in our bodies and genes. We're learning that humanity is both ancient and young, that we're both products of millions of years of evolutionary refinement and newcomers to a world billions of years old. We're discovering that evolution is creative, producing diversity and innovation under the constraints of physics and chemistry and the ancient survival imperatives that have shaped all life on Earth. The Moroccan fossils are just one piece of this vast story, but they're an important piece, a direct link to our deep past.

Key Takeaways

- 773,000-year-old fossils from Morocco provide direct physical evidence from the moment when Homo sapiens' ancestors diverged from Neanderthal and Denisovan lineages

- North Africa was an active evolutionary laboratory with hominin populations evolving in parallel to European populations, challenging the Eurocentric narrative of human evolution

- The split between modern human ancestors and other hominin lineages likely occurred around 800,000 years ago, slightly earlier than genetic estimates alone suggested

- Multiple human species coexisted for hundreds of thousands of years with evidence of genetic admixture occurring multiple times across the Pleistocene epoch

- Modern paleontological techniques like micro-CT scanning and geometric morphometry enable sophisticated analysis without damaging irreplaceable fossils

![Ancient Hominin Fossil Reveals Secrets of Human Evolution Split [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ancient-hominin-fossil-reveals-secrets-of-human-evolution-sp/image-1-1767804013081.jpg)