Appeals Court Blocks Trump's Research Funding Cuts: What It Means for Universities and Science [2025]

Here's something that almost flew under the radar last month: a federal appeals court decisively rejected the Trump administration's attempt to slash how much money universities receive for indirect research costs. If you've been following scientific funding policy, you know this isn't the first time. The administration already tried this exact move during the first term, Congress blocked it, and now they're facing the same wall again.

But this ruling matters for reasons that go way beyond the headline. It's about congressional power, agency authority, the future of American research infrastructure, and what happens when an administration tries to override explicit legislative mandates. Let me walk you through what happened, why it matters, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- Court Decision: A three-judge federal appeals panel unanimously rejected the Trump administration's effort to cut university research reimbursement rates to a flat 15%, citing explicit congressional prohibition. According to Forbes, this decision was a direct response to Congress's protective measures.

- Congressional Block: Congress passed a budget rider in 2017 specifically to prevent this exact action, and has renewed it annually since then, as detailed in The New York Times.

- What's at Stake: Universities depend on indirect cost reimbursements for lab maintenance, building operations, animal care facilities, and staff salaries—cuts would devastate research infrastructure, as noted by STAT News.

- Next Steps: The administration's only viable option is appealing to the Supreme Court, though the court's track record on research funding is mixed and unpredictable, as reported by Nature.

- Bottom Line: University research funding remains protected for now, but the threat isn't entirely eliminated until the political landscape shifts or the Supreme Court rules.

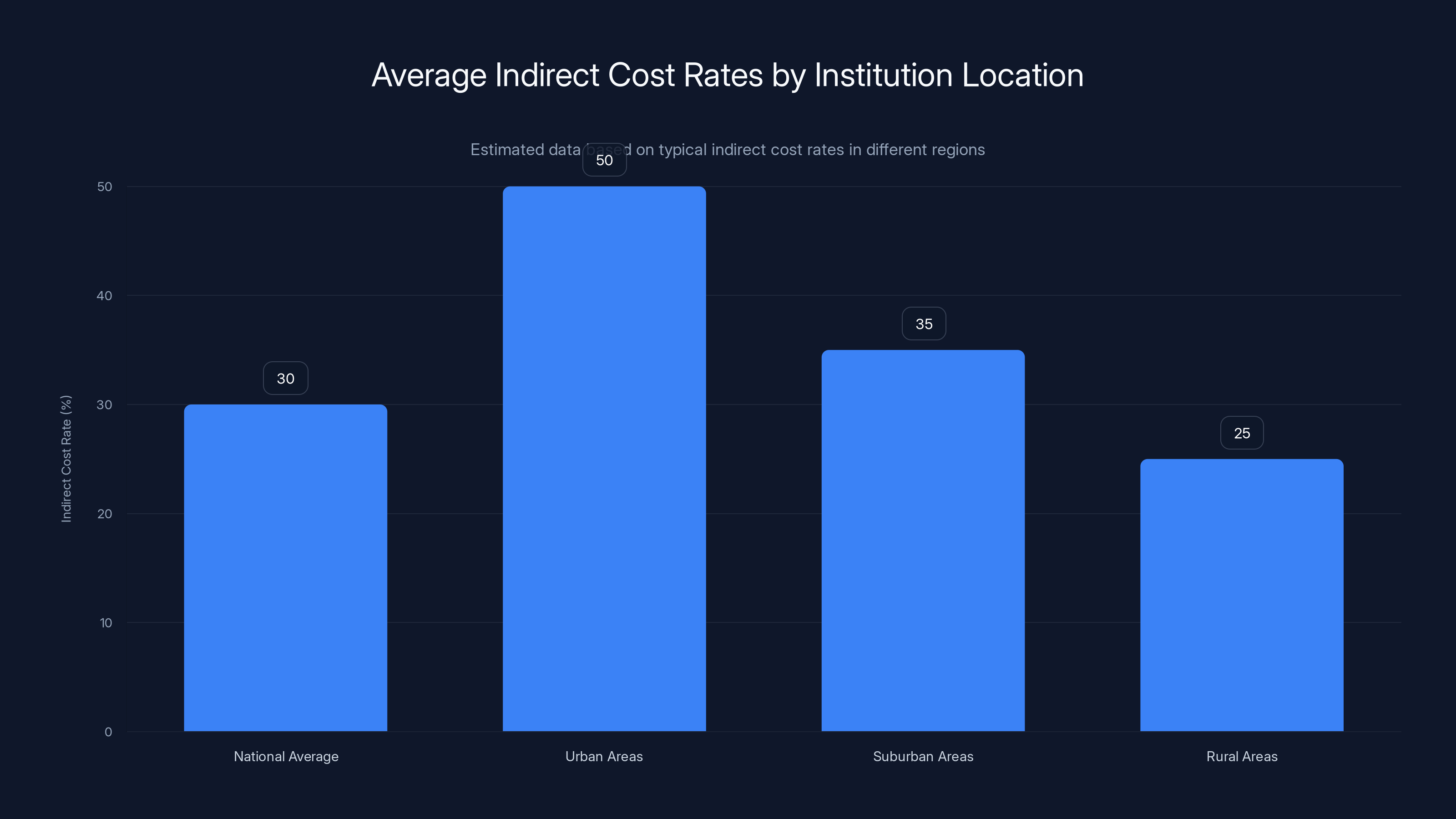

Indirect cost rates vary significantly by location, with urban institutions often exceeding 50% due to higher operational costs. Estimated data.

Understanding Indirect Research Costs: The Hidden Backbone of American Science

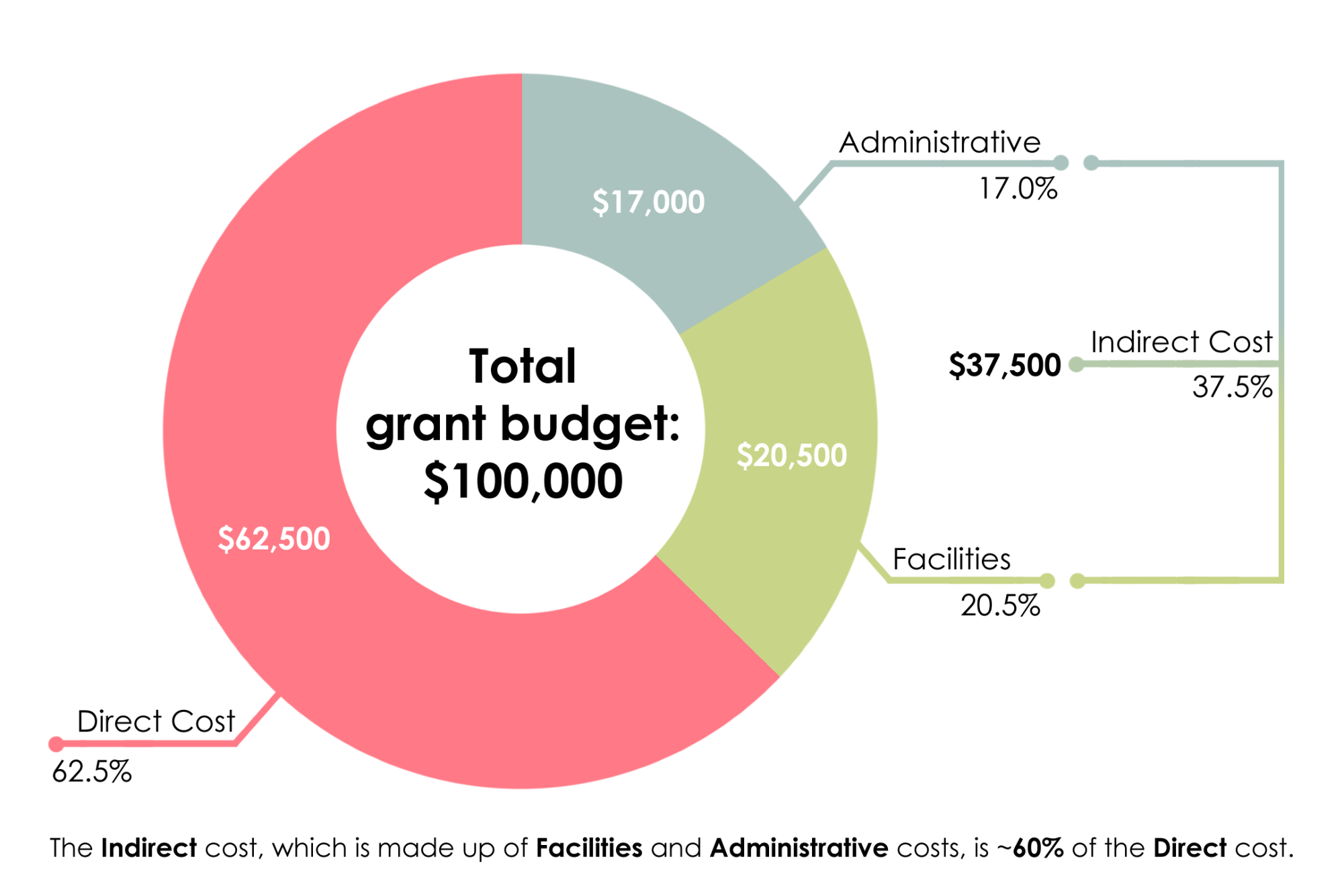

Let's start with something most people don't think about: when a university researcher receives a federal grant from the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation, that grant money only covers the direct costs of the research itself. The chemicals. The equipment. The software licenses. The researcher's salary during the project period.

But here's the part nobody talks about at dinner parties: running a research lab costs way more than just the research.

Who maintains the building? Who pays for the electricity that keeps the lab running 24/7? Who staff the animal care facilities for mice and primates used in medical research? Who manages the hazardous waste disposal? Who provides IT support for the lab's servers and data systems? Who runs the accounting department that ensures grant funds are used appropriately?

All of that falls under "indirect costs." They're real expenses, they're necessary, and they're not optional. Without them, research simply stops happening.

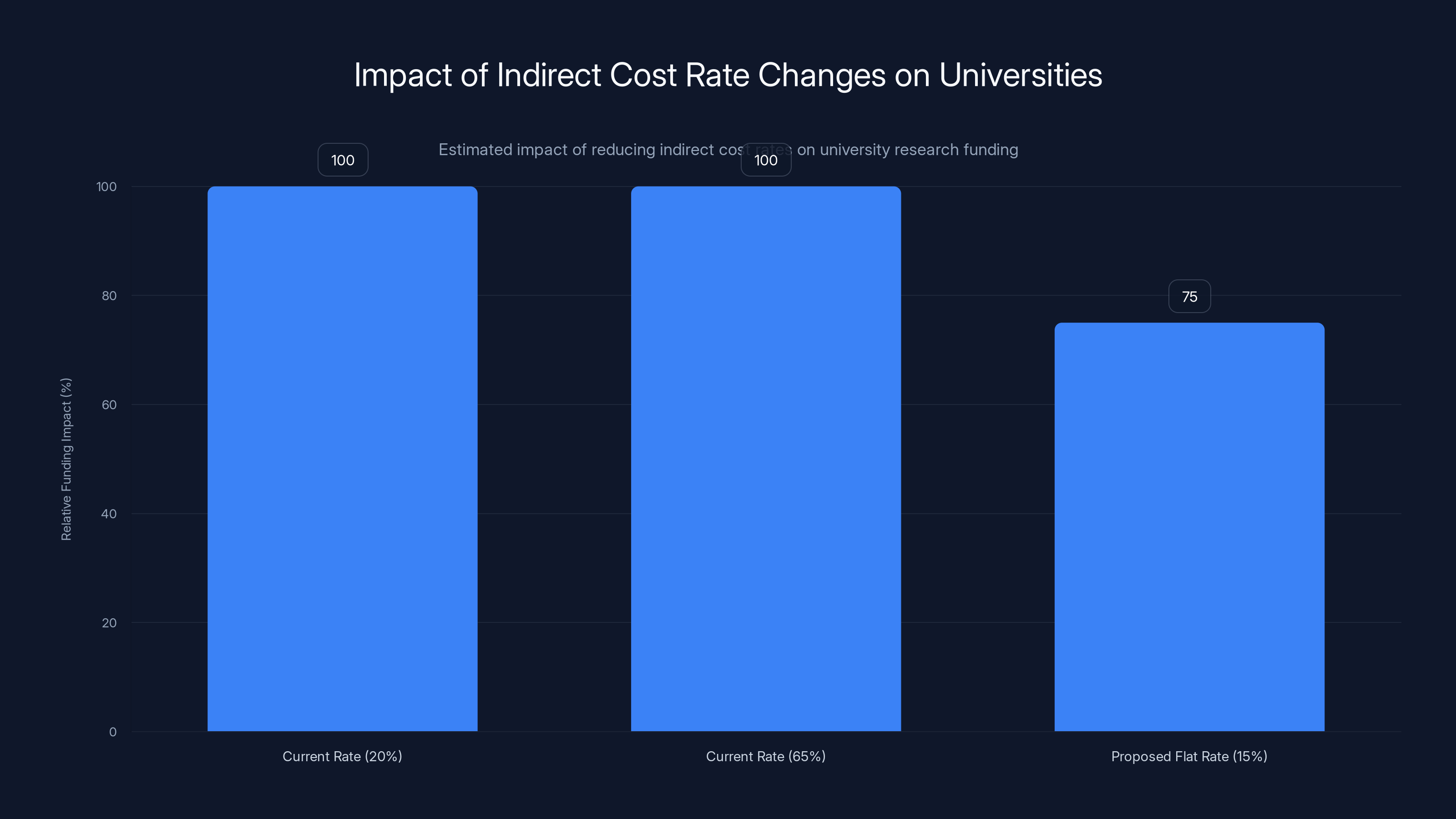

The NIH created a formula-based system to account for these costs. Universities estimate their research-related expenses—both variable and fixed—and negotiate an "indirect cost rate" with the federal government. This rate is expressed as a percentage of the grant's value. So if a university negotiates a 35% indirect cost rate and receives a

Nationally, the average indirect cost rate hovers around 30%. But this varies dramatically by location and institution type. Universities in expensive urban areas—think Boston, San Francisco, New York—often have indirect rates exceeding 50%. Why? Because rent, salaries, and operating costs are genuinely higher in those places. A researcher at MIT or Stanford requires different infrastructure investments than a researcher at a university in a lower-cost area.

The system isn't perfect. Universities negotiate rates, audits happen, and adjustments are made. But it's a system that reflects reality: research infrastructure has real costs, and those costs vary.

The First Trump Attack: Why This Happened Before

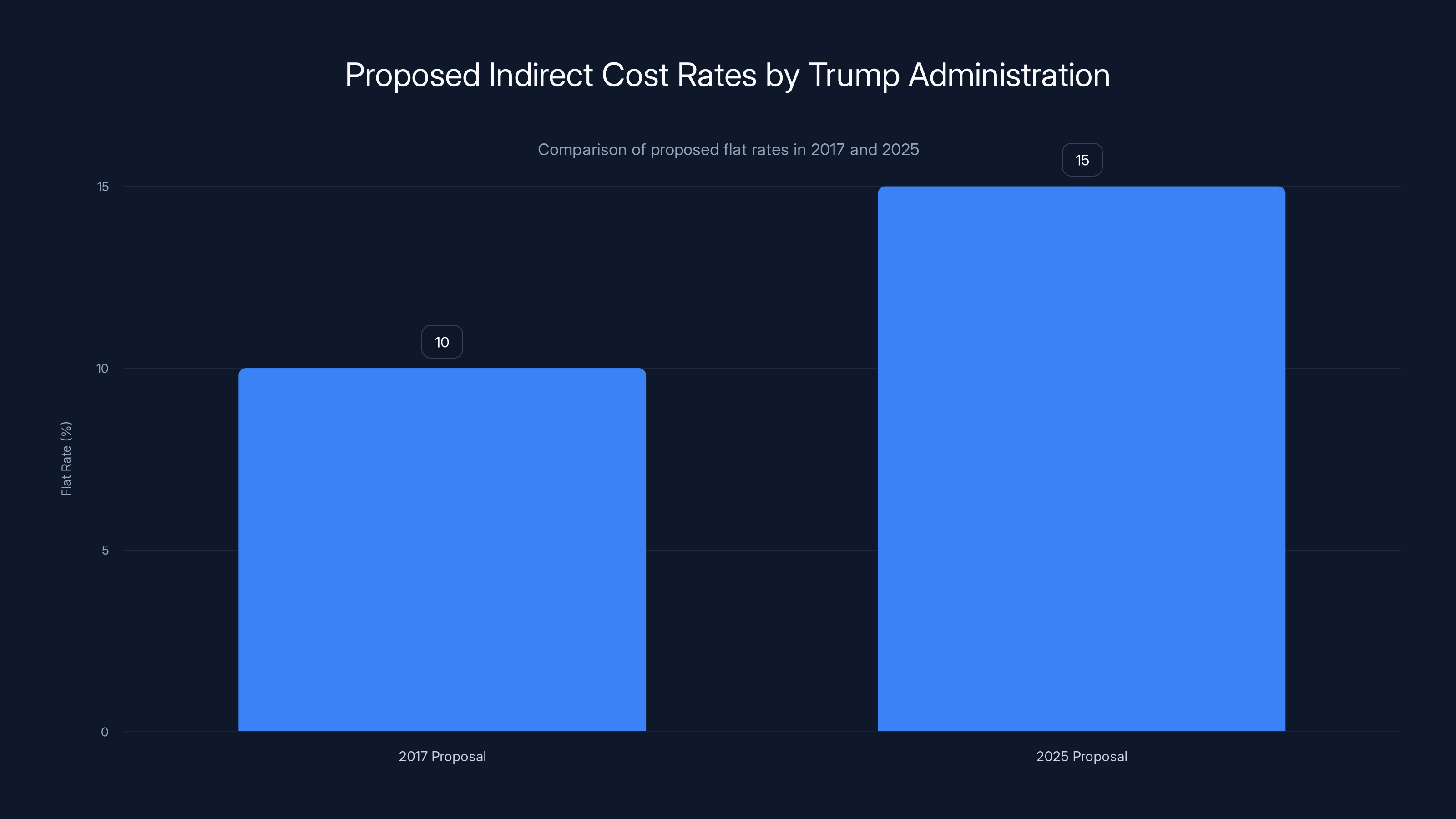

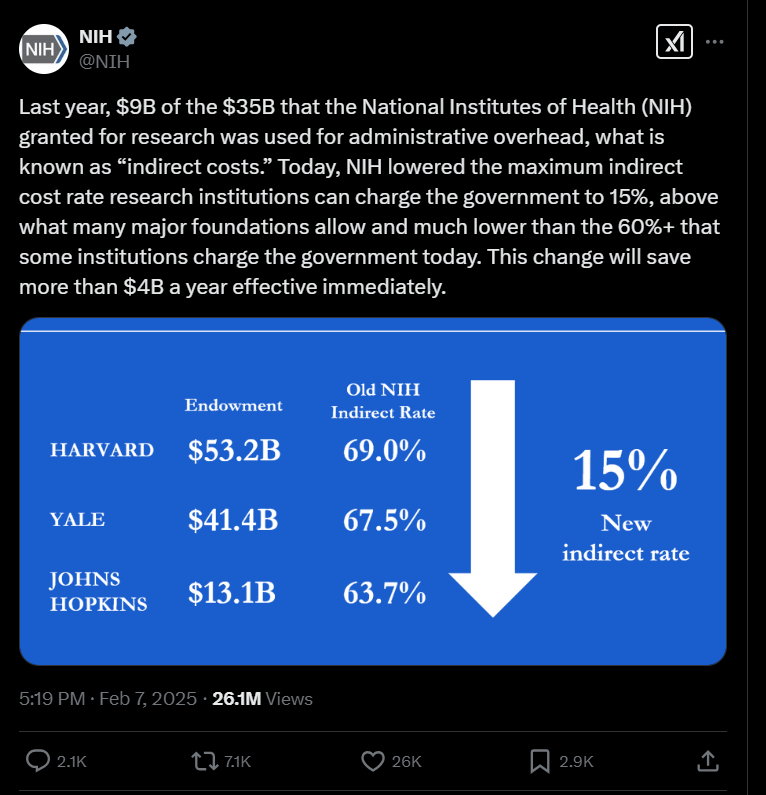

In 2017, during the first Trump administration, something remarkable happened. The White House decided these rates were too high and ordered the NIH to set a universal flat rate of 10% for all universities, regardless of their actual costs.

Think about what that means. A university paying $50,000 monthly for laboratory space in downtown Boston would suddenly have to operate on 10% indirect reimbursement. A university in a lower-cost region would get the same percentage. The system would break, and it would break fast.

But Congress objected. Multiple states sued. Universities mobilized. And Congress responded by attaching a rider to a budget agreement that explicitly prohibited the NIH from implementing this kind of across-the-board rate reduction.

That rider said, in essence: "You can't do this."

The administration backed off. The rates stayed in place. Universities continued operating. Life went on.

Until January 2025, when the Trump administration tried again.

This time, they ordered a flat 15% rate for everyone. Slightly higher than the initial 10% proposal, but still catastrophic for most major research institutions. And they did it the same way: through administrative order, without notice, without the formal comment period required by law, and without congressional input.

States sued immediately. Organizations representing universities and medical schools filed briefs. The system started grinding through the courts.

Why the District Court Said "No"

A federal district court temporarily blocked the new policy, then issued a permanent injunction. The reasoning was straightforward and comprehensive.

First, the process itself violated the Administrative Procedures Act. Federal agencies can't just announce new policies affecting billions of dollars without notice and opportunity for public comment. That's not how government is supposed to work. The Trump administration's approach was legally arbitrary.

Second, the flat 15% rate was arbitrary and capricious compared to the system it replaced. There was no evidence presented that universities were overcharging the government. There was no cost-benefit analysis. There was no documentation showing why this specific rate made sense. It was just a number, imposed from above.

Third, the policy violated existing procedures within the Department of Health and Human Services. The NIH has established formulas, audit processes, and negotiation frameworks. The administration was trying to bypass all of it.

The district court ruling was solid. It checked all the legal boxes. It provided universities with temporary protection. But it didn't mention the most important thing: Congress had already made this decision.

The Appeals Court's Elegant Knockout Punch

When the government appealed the district court's decision, something interesting happened. A three-judge panel from the Court of Appeals didn't bother with all those administrative law questions.

They went straight to the fundamental issue: Congress had explicitly prohibited exactly this action.

Remember that budget rider from 2017? Congress has renewed it every single year since then. It says, plainly, that the NIH can't alter its overhead reimbursement policy. There are some narrow exceptions listed in the language, but they're genuinely narrow.

The government tried to argue that the exceptions were broad enough to cover this new policy. The court disagreed, with what sounds like barely concealed exasperation. The judges wrote that it's "clearly inconsistent" with the limits Congress set. When you look at what Congress originally passed the rider to prevent—exactly what the administration is trying to do now—the legislative history is unambiguous.

The appeals court spent significant effort explaining how their decision is consistent with Supreme Court precedent, particularly a recent awkward split decision about judicial intervention in research funding policy. This is telling. They're writing with an eye toward the Supreme Court, knowing this case might land there.

But the reasoning is airtight. Congress acted. Congress was specific. Congress has renewed its action every year. The administration can't override that through bureaucratic fiat.

The Trump administration proposed a flat indirect cost rate of 10% in 2017, which was later increased to 15% in 2025. Both proposals faced significant opposition from universities and states.

What Research Infrastructure Actually Needs This Money For

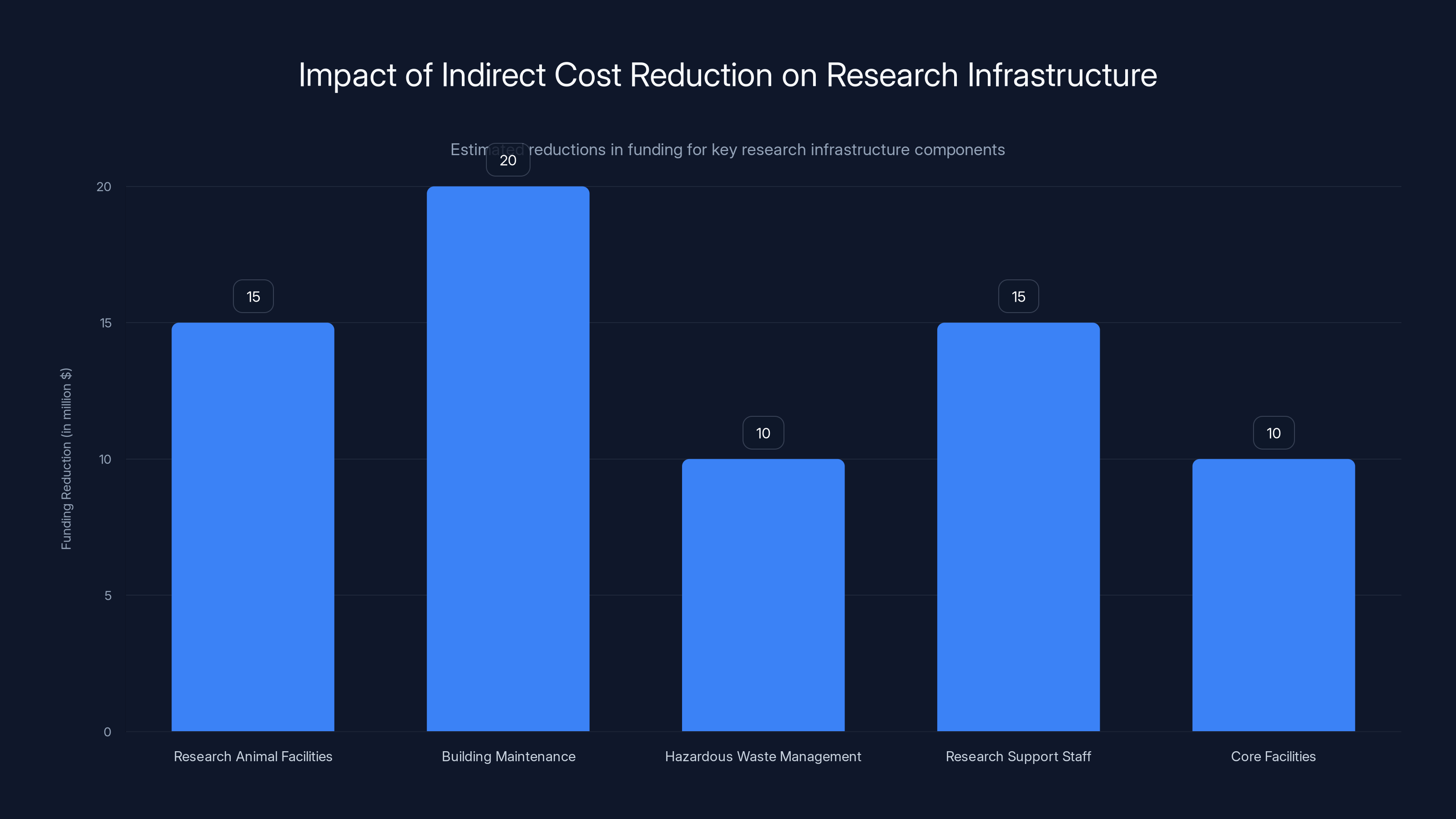

Let's get concrete about what happens if the Trump administration succeeded and these indirect costs got slashed by 70%.

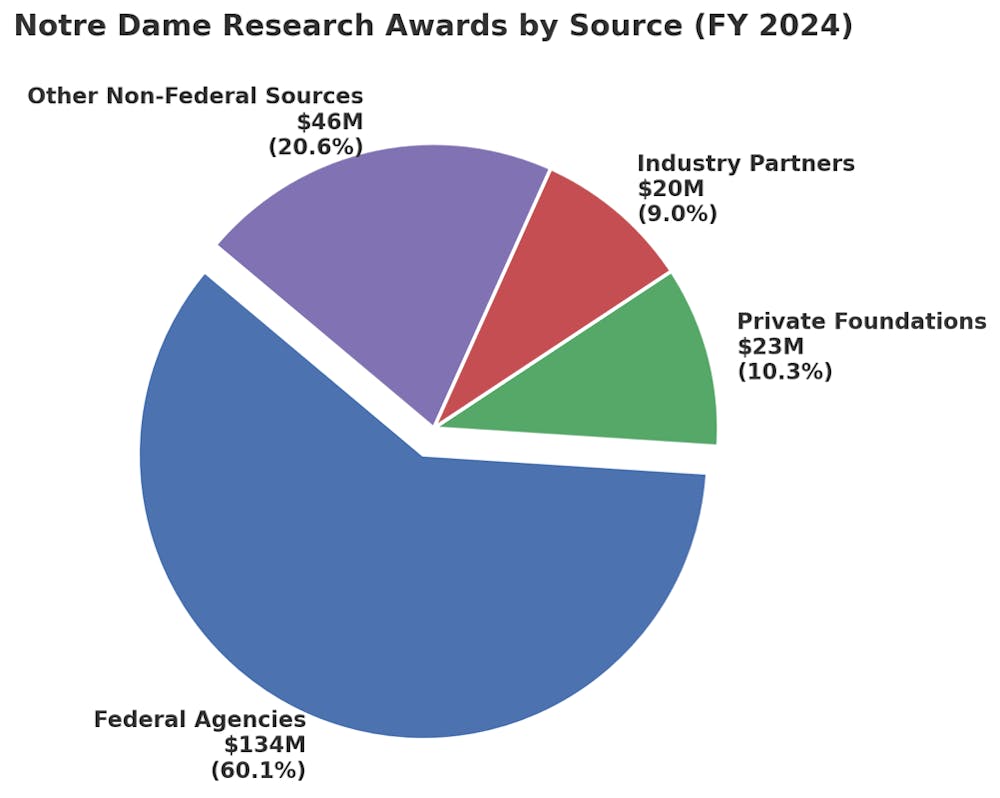

Take a major research university in an expensive city. The NIH funding alone might represent

Now suddenly that drops to 15% of the grant value. That's

What gets cut? Real things. Real people.

Research Animal Facilities: Major universities maintain colonies of laboratory mice, primates, and other animals used in biomedical research. These facilities require 24/7 staffing, climate control, specialized veterinary care, and complex biosafety systems. You can't maintain these with a shoestring budget. Animals die. Research stops.

Building Maintenance and Infrastructure: Research buildings need constant maintenance. HVAC systems, electrical systems, plumbing, fire safety systems. When you defer maintenance, things break. Pipes burst. Electrical systems fail. And when the building system fails, the research stops.

Hazardous Waste Management: Research generates chemical waste, radioactive material, biological waste. This has to be handled by trained professionals according to strict protocols. You can't cut corners on this. Cutting the budget doesn't make the waste go away; it just makes safe disposal harder.

Research Support Staff: Lab managers, research coordinators, data analysts, IT support. These aren't luxuries. They're people who keep research running. Cut their budgets and you lose experienced staff, which means new researchers have to learn everything from scratch.

Core Facilities and Shared Equipment: Major universities maintain shared research facilities: electron microscopy centers, genomics labs, bioinformatics cores. These require expert staff to operate and maintain million-dollar equipment. Without adequate funding, these services degrade or disappear.

The cascade effect would be devastating. Research productivity would plummet. Graduate students wouldn't have functional lab spaces. Early-career researchers would move their labs to other countries. The competitive advantage the United States has in biomedical research, built over decades, would erode rapidly.

The Geographic Justice Problem

There's something important here that often gets missed in policy discussions: the flat-rate approach isn't just economically ignorant, it's geographically unjust.

Universities in expensive urban areas would be devastated. MIT, Stanford, UCSF, Johns Hopkins, Columbia—these institutions would face catastrophic budget shortfalls.

But universities in lower-cost regions would actually fare better proportionally. A university in a mid-sized Midwestern city with a 35% negotiated rate would lose money, but not as drastically as MIT.

The perverse result: a flat-rate policy would punish the most productive research institutions hardest. It would push research away from the major research universities with the best equipment, the most experienced faculty, and the strongest collaborative networks.

It's almost designed to break the research enterprise in ways that would take decades to repair.

Why Congress Cares About This Issue

You might wonder: why does Congress spend its time on research reimbursement rates? Shouldn't they focus on bigger issues?

They do. But they also understand something important: research infrastructure is foundational to American competitiveness and economic growth.

Scientific research funded by federal grants leads to medical breakthroughs, new technologies, and trained researchers. But that only happens if the infrastructure exists to conduct the research. You can't do high-quality biomedical research without proper facilities. You can't train the next generation of scientists without functional labs.

Congress's investment in research funding—through the NIH, NSF, and other agencies—is one of the government's smartest investments. The return on investment is enormous. But only if the infrastructure stays intact.

When the Trump administration tried to slash indirect costs in 2017, Congress responded. Not because they loved universities, but because they understood the policy was bad for American science and American innovation.

They renewed that protection every year since. That's deliberate. That's intentional policy.

And the appeals court recognized that. The judges noted that the appropriations rider was a direct response to the first Trump administration's proposal. Congress wasn't ambiguous. Congress was clear.

The Administrative Procedures Act Problem

Let's talk about the legal framework for how government agencies operate, because this matters beyond just research funding.

The Administrative Procedures Act is one of the most important and underappreciated laws in American governance. It requires federal agencies to follow certain procedures when they implement major policy changes.

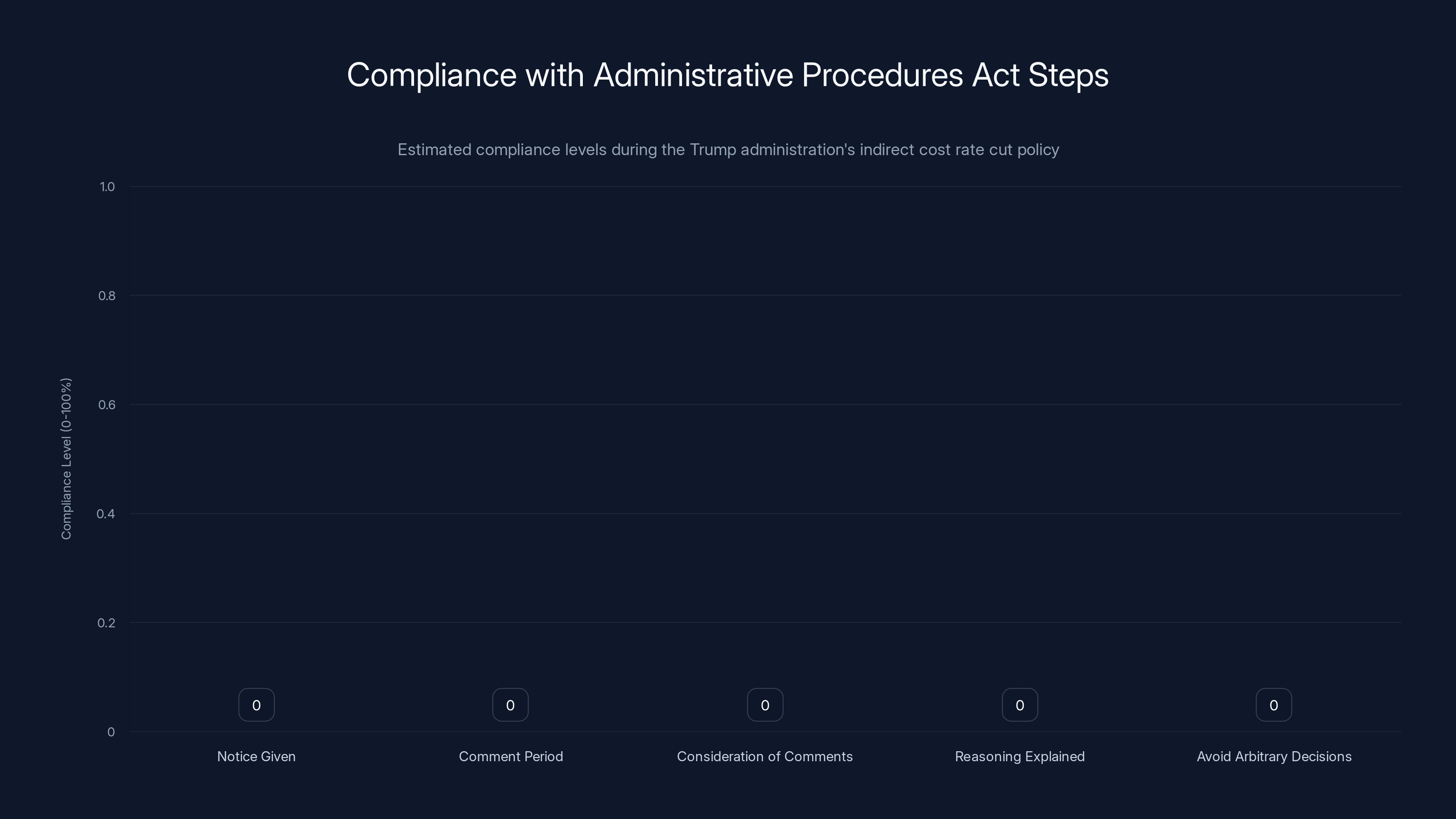

At minimum, agencies must:

- Give notice that they're considering a rule change

- Allow comment from affected parties

- Consider the comments seriously

- Explain their reasoning in writing

- Avoid arbitrary and capricious decision-making

The Trump administration's approach to the indirect cost rate cut ignored all of this. They issued an order. No notice. No comment period. No documented analysis. Just: "New policy, effective immediately."

The district court found this violated the APA. The Trump administration argued that maybe some parts of the APA didn't apply, or maybe they could invoke some emergency exception.

The appeals court didn't need to resolve those arguments because Congress had already prohibited the policy.

But the principle matters. Agencies don't get to impose major policy changes on a whim. There's supposed to be a process. There's supposed to be notice. Affected parties get to respond. Agencies have to explain their thinking.

When that process gets bypassed, courts can step in.

The Supreme Court Wildcard

Here's where things get genuinely uncertain.

The Trump administration can appeal to the Supreme Court. There's nothing stopping them. They almost certainly will.

And here's the uncomfortable truth: the Supreme Court's record on research funding policy is mixed and unpredictable.

There's a recent Supreme Court precedent about judicial intervention in research funding decisions. It wasn't a clean victory for anyone. It was an awkward split decision. Justices disagreed about how much deference courts should give to agency decisions in this area.

The appeals court spent substantial effort explaining how their reasoning aligns with that precedent. But Supreme Court precedent is flexible, and the Court can overturn or reinterpret previous decisions.

If the Supreme Court takes the case—and they might—the outcome is genuinely uncertain. The administration has won several major cases at the Supreme Court on other regulatory and procedural matters. The current Court's composition is more skeptical of agency regulation and more deferential to executive power in some areas.

But even the current Court isn't going to ignore explicit congressional prohibition. Congress said this can't happen. Congress renewed that statement every year. That's powerful language.

Still, nothing is guaranteed.

Estimated data shows significant funding reductions across critical research infrastructure components due to a 70% cut in indirect costs.

What the Trump Administration Could Actually Do

Given the strength of the appeals court ruling and the explicit congressional prohibition, what options does the Trump administration actually have?

Option 1: Appeal to the Supreme Court. We discussed this. It's risky, but it's possible.

Option 2: Work with Congress to repeal the rider. This seems essentially impossible. Congress is actually moving in the opposite direction, trying to increase research funding, not decrease it. The political capital required to convince Congress to allow these cuts is enormous. It's not happening.

Option 3: Use a different mechanism. Could the administration use a different law or regulatory framework to achieve the same goal? Probably not. Congress was specific. They blocked this specific approach. Trying to accomplish the same thing through a different mechanism would likely face the same legal problems.

Option 4: Wait out the current Congress. Eventually, there could be a Congress more sympathetic to this idea. But that's years away, and the political landscape keeps shifting.

Really, the administration's only viable option is the Supreme Court.

The Legislative History Factor

One thing the appeals court emphasized is the importance of legislative history.

When Congress passed the original rider in 2017, they did so in direct response to the Trump administration's 10% flat-rate proposal. The legislative history is clear. Members of Congress explicitly stated they were blocking this action. They debated it. They voted on it. They renewed it.

That matters legally. When interpreting what Congress meant by its language, courts can look at legislative history—what Congress said it was doing at the time.

The appeals court took this seriously. The judges noted that even if the rider's language was slightly ambiguous (which they found it wasn't), the legislative history shows what Congress was trying to prevent.

So even if a Supreme Court justice wanted to find a loophole in the rider's language, they'd have to directly contradict what Congress said it was doing. That's a much harder argument to make.

Why This Ruling Matters Beyond Research Funding

This case is about more than just how universities get reimbursed for research infrastructure. It's about basic constitutional principles.

Congress is the branch of government that controls the purse. Congress decides how much money gets spent, and Congress can attach conditions to spending. That's Article I of the Constitution.

The executive branch—the administration—implements Congress's decisions. They're not supposed to override Congressional spending decisions because they disagree with them. If they could, the separation of powers breaks down.

This case is a straightforward application of that principle. Congress decided indirect cost rates wouldn't be slashed. Congress renewed that decision. The Trump administration tried to override it anyway.

The appeals court said no. Congress's decision stands.

That's not some partisan point. That's how the government is supposed to work.

What Universities Are Saying

University leadership is obviously relieved, but they're also careful. They know this isn't fully settled until the Supreme Court either declines to hear it or rules in their favor.

Major research institutions released statements emphasizing the importance of adequate research infrastructure funding. They talked about their commitment to innovation, to training researchers, to advancing science.

What they didn't say, but what's implied: if this policy had gone through, research would have suffered significantly.

Universities are also looking at what comes next. Is this a one-off threat, or is the administration going to try other approaches to cut research funding? If other cuts are coming, universities need to know, so they can prepare.

The uncertainty is almost as challenging as the cuts themselves.

The Broader Threat to American Research

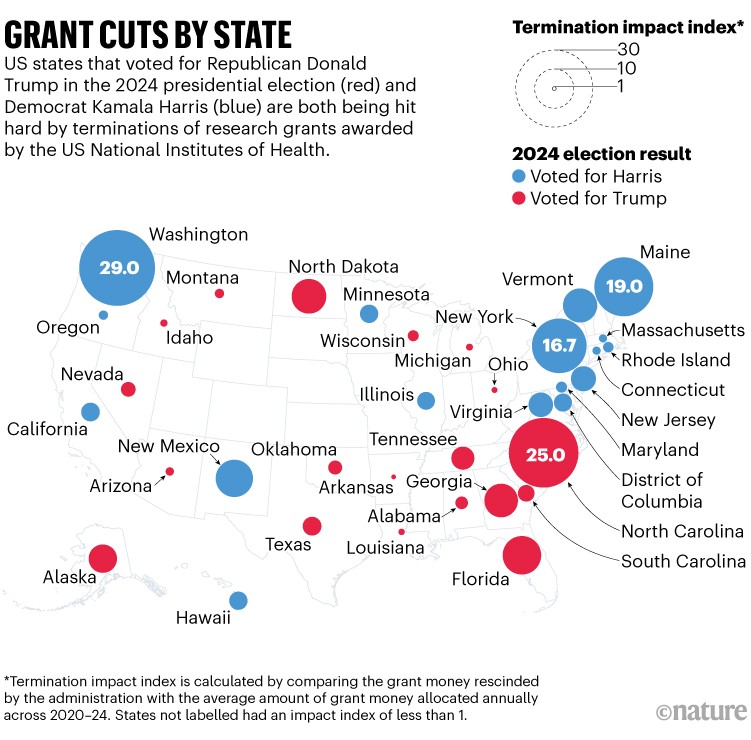

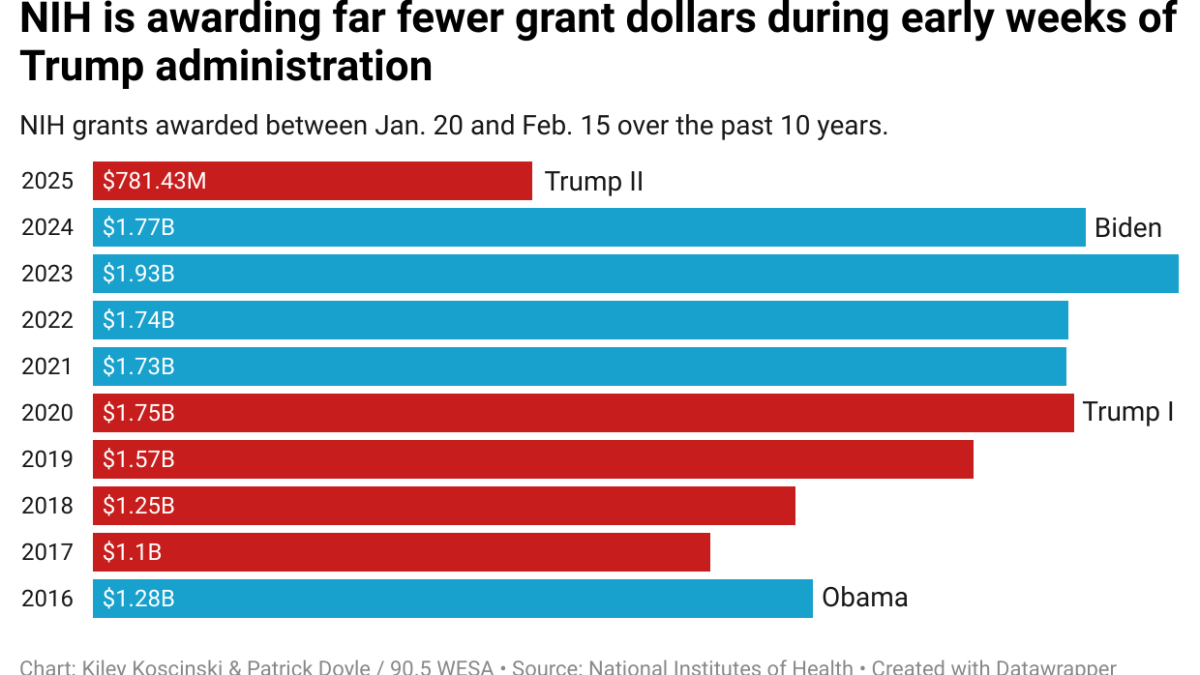

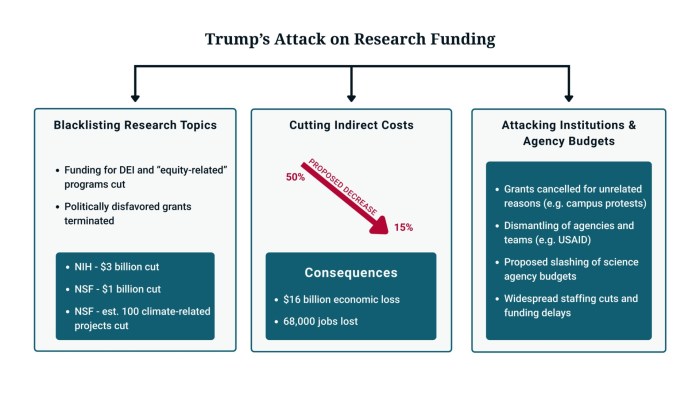

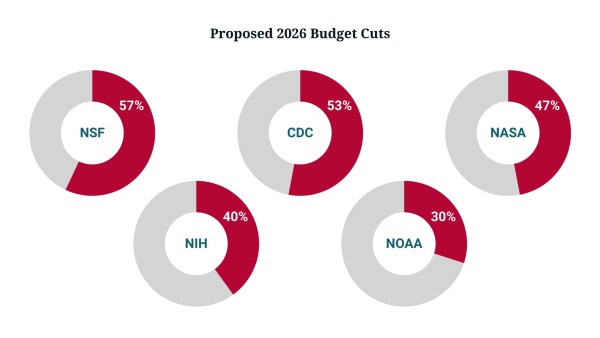

This specific case is about indirect cost rates. But it's happening in a context of broader threats to American scientific funding.

Funding for basic research—the kind that doesn't have immediate commercial application but leads to breakthroughs—is under pressure. Funding for scientific agencies is being questioned. Scientists worry about political interference in research decisions.

The indirect cost rate attack is just one manifestation of a broader skepticism toward research funding in some circles of government.

Scientific organizations worry that if this precedent were set, it could open the door to other cuts. If indirect costs could be slashed arbitrarily, what about direct research funding? What about funding for specific types of research the administration finds politically inconvenient?

The appeals court's firm ruling sends a message: Congress gets to decide research funding policy, not the executive branch unilaterally.

But the fact that the administration tried suggests this might not be the last attempt.

Reducing indirect cost rates to a flat 15% would significantly decrease funding for universities, especially those currently receiving higher rates. Estimated data.

International Competition Angles

Here's something that adds urgency to this debate: other countries are investing heavily in research infrastructure.

China is building world-class research facilities. European countries are coordinating research investments. Other developed nations understand that research infrastructure drives innovation and competitiveness.

If the United States allowed research infrastructure to deteriorate through inadequate funding, the competitive advantage erodes. Researchers move elsewhere. Graduate students pursue opportunities in better-funded environments. The innovation pipeline weakens.

In a globalized knowledge economy, this isn't a minor issue. This is about whether the United States remains a leader in scientific innovation.

The appeals court decision protects that, at least for now.

The Path Forward

If the administration appeals to the Supreme Court, here's what likely happens:

First, the Supreme Court has to decide whether to take the case. They receive thousands of petitions and take only about 70-80 cases per year. This case involves important principles about congressional authority and research funding, so they might take it. But they also might let the appeals court decision stand.

If they take it, there will be briefing from both sides, likely with many supporting briefs from universities, scientific organizations, states, and others with an interest in the outcome.

Then there's argument before the Court, where lawyers from the government and the universities' attorneys will present their cases.

Then the Court will deliberate and eventually issue a decision.

This whole process could take 12-18 months, maybe longer.

In the meantime, indirect cost rates remain intact. Universities can plan around current funding levels. Research continues.

But researchers and administrators certainly feel the uncertainty. Every time the Supreme Court makes a major decision about executive power, observers wonder if this case is next.

What Researchers Actually Care About

At the end of this policy debate, there are thousands of researchers and students and lab staff who just want to do good work.

When research infrastructure funding is uncertain, it's hard to do good work. You can't plan multi-year projects if you don't know whether your facilities will still exist. You can't commit to hiring talented people if you're not sure you can afford to keep them.

Scientific progress requires stability and planning. That's why this policy matters, not just in the abstract, but in the actual day-to-day work of conducting research.

The appeals court decision provides that stability, at least for now.

Historical Context: Why Research Funding Has Always Been Political

Science funding has always been entangled with politics. It's not like there was a pure, non-political era and we've only recently become political.

During the Cold War, research funding was about beating the Soviet Union in the space race and military technology. That was deeply political.

In the 1970s and 1980s, funding for specific diseases depended partly on political priorities. That was political.

What's supposed to prevent pure politics from dominating research decisions is that Congress and the scientific community have established processes and principles. Grant review is supposed to be based on scientific merit. Funding decisions are supposed to follow established procedures.

The Trump administration's approach—just ordering a flat rate cut without process, without evidence, without consultation—violates those principles.

The appeals court protected those principles by enforcing what Congress had already decided.

The Narrow Exceptions That Weren't Actually Narrow

One interesting aspect of the court's decision involves the government's argument about exceptions.

The congressional rider that blocks this policy does include some narrow exceptions. It allows the NIH to make certain adjustments to indirect cost calculations in specific circumstances.

The government argued these exceptions were broad enough to cover the flat-rate policy.

The appeals court said no, with what reads like judicial eye-rolling. The exceptions are narrow. They don't include "implement a completely different system."

This is important because it shows the court was carefully reading what Congress actually wrote, not just accepting the government's creative interpretation.

It's also important because it means Congress's prohibition is genuinely firm. Congress didn't leave loopholes. Congress was specific about what the NIH can and cannot do.

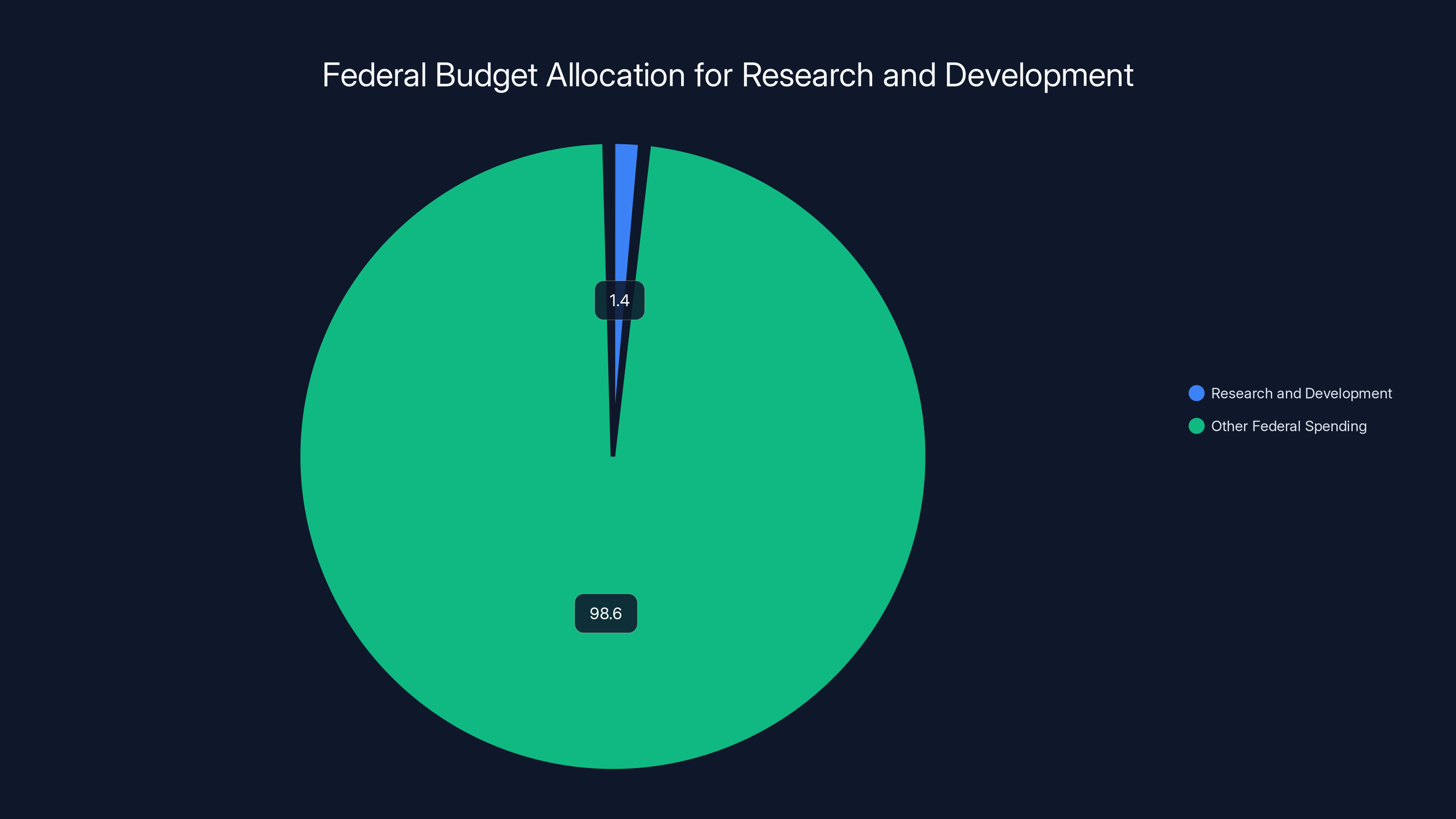

Approximately 1.4% of the federal budget is allocated to research and development, highlighting its importance amidst broader spending priorities.

Looking at Similar Cases

This case joins a larger body of litigation about agency authority and congressional restrictions.

When Congress passes a law or appropriations rider restricting what an agency can do, can the agency ignore it? No. Courts have consistently held that Congress's statutory restrictions bind agencies.

This principle applies across government. If Congress restricts EPA authority in a particular way, the EPA can't ignore it. If Congress restricts Department of Defense procurement in a particular way, Do D can't ignore it.

The Trump administration's approach to the indirect cost rate violated this basic principle. The appeals court enforced it.

Whether the Supreme Court will overturn this reasoning is the major remaining uncertainty.

The Broader Budget Battle

This policy fight is happening in the context of larger debates about government spending.

The Trump administration has pushed for cuts to many government programs. Some of these cuts go through. Some are blocked by courts. Some are blocked by Congress.

Research funding is one arena where this is playing out. Another is environmental regulations. Another is immigration policy. Another is healthcare.

Each of these involves questions about agency authority, congressional intent, and executive power.

The appeals court's decision in this case sends a message: when Congress has explicitly restricted agency action, that restriction matters. Agencies can't just override it.

That principle applies broadly.

What This Means for Future Administrations

One valuable aspect of this decision is that it's not tied to any particular administration or party. It's about basic constitutional principles.

If a future Democratic administration tried to override a congressional restriction on agency action, the same principle would apply. Congress's restriction would stand.

This case establishes (or reaffirms) that Congress controls the purse. Congress sets the terms of federal spending. Agencies implement those terms; they don't override them.

That's foundational to how American government works.

The Role of the States

One often-overlooked aspect of this case is that multiple states were part of the lawsuit.

States sued to protect research funding at state universities. This is important because many of the most prestigious research universities in the country are public institutions. MIT isn't, but UCLA is. University of Michigan is. University of North Carolina is.

If federal research funding got cut, state governments would face pressure to backfill the losses. The economic impact would fall partly on the states.

That's why multiple states joined the lawsuit. It wasn't just about principle; it was about their own fiscal health.

The appeals court ruling protects them from having to absorb those costs, at least for now.

Timing and the 2025 Budget Process

This decision came during a time when Congress was actively working on its budget.

Interestingly, Congress is actually moving to increase some research funding, not decrease it. There's bipartisan support for certain areas of research, including artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and semiconductor manufacturing.

So the political environment is actually working against the Trump administration's goal of cutting research funding.

If the administration wants to succeed at fundamentally changing how research is funded, they'll need Congress to cooperate. And Congress doesn't seem interested.

That makes an appeal to the Supreme Court even more of a long shot.

The Trump administration's indirect cost rate cut policy showed no compliance with the APA's required steps, leading to legal challenges. Estimated data.

The Scientific Community's Response

Major scientific organizations filed briefs in this case supporting the universities.

These organizations understand the importance of research infrastructure. They were genuinely concerned about what would happen if the cuts went through.

Now that the appeals court has ruled in their favor, they're not declaring victory. They know the Supreme Court could overturn this. They're staying engaged, preparing for potential future litigation.

Scientists also understand that this is ultimately a political issue, not just a legal one. Long-term research funding security requires political support, not just court decisions.

The Precedent Question

One reason the appeals court was probably careful in its reasoning: they wanted to establish a clear precedent that could withstand Supreme Court review.

The court emphasized Congress's explicit intent. They focused on the legislative history. They noted that Congress has renewed the restriction every year.

They made a straightforward constitutional argument: Congress controls the purse. Congress decided this. The administration can't override it.

That's a robust principle. It's hard to argue with without essentially saying that executive authority overrides congressional spending restrictions. Almost nobody wants to take that position openly.

The Question of Emergency Powers

One argument the government might make to the Supreme Court: in emergencies, maybe executive power expands and can override certain restrictions.

But there's no emergency here. Research isn't a crisis situation. This is ordinary governance.

The appeals court didn't need to address emergency powers because there's no emergency. But if the Supreme Court takes the case, this argument might come up.

It's not a strong argument, but it's an argument.

Long-Term Research Planning

One concrete impact of the appeals court decision: universities can now make long-term plans around current funding levels.

Research infrastructure projects take years to plan and execute. You can't start a multi-year renovation of research facilities if you don't know whether you'll have the funding to complete it.

Now, universities can move forward with planned upgrades, expansions, and infrastructure improvements.

That's not just administratively important; it's scientifically important. Better facilities support better research.

The Gap Between Ruling and Resolution

One challenge: this decision leaves uncertainty in place for maybe another year or more, until the Supreme Court rules or decides not to take the case.

For universities, that's better than losing the case, but it's still uncertainty. It's hard to make investments when you're not sure about the political and legal environment.

That gap between this ruling and final resolution is something administrators have to manage.

What Comes After This Case

Regardless of whether the Supreme Court takes this case or not, research funding policy will remain contentious.

There are legitimate debates about how much the federal government should spend on research, which areas deserve priority funding, and whether current funding mechanisms are efficient.

Those are reasonable policy questions.

What's not reasonable—what the appeals court rejected—is administration officials trying to circumvent Congress's decisions through bureaucratic fiat, without process, without evidence, without giving affected parties a voice.

Even if you think research funding should be cut, you should want that decision to go through proper processes, with Congressional input, with documented reasoning.

The appeals court reinforced that principle.

The Intersection of Science and Governance

This case sits at an interesting intersection: it's about science funding, but it's also about government structure and how power is supposed to work.

The courts got involved because Congress's authority was at stake. This isn't a case where courts are dictating science policy. It's a case where courts are enforcing what Congress decided.

That's an important distinction.

Scientific communities sometimes worry about courts getting involved in science policy. But in this case, the court was protecting Congress's authority and preventing arbitrary executive action.

That's the proper role for courts.

Preparing for Uncertainty

For universities and researchers, the practical lesson is: don't assume anything is permanently settled.

Policies can change. Courts can overturn decisions. Political environments shift.

The smart approach: plan around the funding you have, but maintain flexibility for potential changes. Build some financial reserves if you can. Don't commit to permanent expenses based on optimistic assumptions about future funding.

That's just prudent management when dealing with government funding and political uncertainty.

The Bigger Picture on Federal Research Spending

The United States spends roughly 1.4% of the federal budget on research and development—about $180 billion annually across all agencies.

That's a significant investment. It produces significant returns in innovation, technological advancement, and trained researchers.

But it's always under pressure. There are always people arguing the government spends too much on research, or should shift research spending to different areas, or should fund research differently.

Those are reasonable debates to have.

What's not reasonable is trying to change policy without process, without evidence, without Congressional input.

The appeals court protected that principle.

FAQ

What exactly are indirect research costs?

Indirect costs are expenses incurred by universities in conducting federally funded research that aren't directly attributed to a specific project. These include building maintenance, utilities, research animal facility operations, hazardous waste management, staff salaries for support services, and IT infrastructure. The NIH reimburses universities for these costs as a percentage of the direct grant amount, typically ranging from 20% to 65% depending on the institution's location and negotiated rates.

Why would cutting indirect costs be so damaging?

Cutting indirect costs to a flat 15% would force universities to operate research facilities on inadequate budgets. Universities would struggle to maintain lab buildings, veterinary facilities, and equipment. Experienced support staff would be laid off. Many research universities would face serious financial crises. The result would be reduced research capacity, fewer training opportunities for graduate students, and loss of competitive advantage to other countries' research institutions. Research in expensive urban areas would be particularly devastated.

How did Congress block this policy?

In 2017, Congress passed a budget rider (an addition to an appropriations bill) explicitly prohibiting the NIH from altering indirect cost reimbursement rates in the manner the Trump administration proposed. This rider has been renewed every year since. The rider doesn't make indirect costs permanent, but it requires that any changes go through proper processes with notice, comment, and Congressional oversight—the administration can't impose changes unilaterally.

What was the court's reasoning in blocking the policy?

The appeals court panel found that Congress had explicitly prohibited exactly what the Trump administration was trying to do. Rather than focusing on whether the policy violated administrative procedures or was arbitrary and capricious, the court simply noted that Congress had made this decision and the executive branch cannot override Congressional spending restrictions. The legislative history made clear that Congress passed the rider specifically to prevent this exact policy proposal.

Could the Supreme Court overturn this decision?

Yes, the Trump administration can appeal to the Supreme Court, and the outcome would be uncertain. The Supreme Court's recent precedent on research funding policy is mixed. However, the appeals court's reasoning about Congressional authority and the prohibition on overriding Congressional spending restrictions is based on fundamental constitutional principles that would be difficult to overturn. Most constitutional scholars believe Congress's control of federal spending is well-established, but Supreme Court decisions are always ultimately unpredictable.

What happens if the Supreme Court doesn't take this case?

If the Supreme Court declines to hear the case, the appeals court decision stands. Indirect cost rates would remain protected, and the Trump administration would need to work with Congress to change the policy. Given that Congress has renewed the protective rider every year and is moving to increase research funding, it's unlikely Congress would cooperate with efforts to cut indirect costs. The policy would effectively be blocked indefinitely unless Congress changes course.

How do universities actually negotiate indirect cost rates?

Universities submit cost studies to the NIH showing their actual facility, administrative, and overhead costs related to research. The NIH reviews these costs and negotiates a rate—a percentage of grant value—that reflects those actual expenses. Rates vary based on location (expensive urban areas get higher rates) and institutional characteristics. Once negotiated, audits can verify that actual costs match the negotiated rates. The current system, while imperfect, reflects genuine geographic and institutional cost differences.

Why does Congress care about this specific policy?

Congress understands that research infrastructure is foundational to American competitiveness, medical innovation, and technological advancement. Federal research funding generates significant returns on investment. If infrastructure funding is inadequate, research productivity declines and competitive advantage is lost to other countries. When the Trump administration tried to cut these costs in 2017, Congress responded to protect an investment it views as strategically important to national interests.

Could the Trump administration try a different approach?

The Trump administration could try to achieve similar cuts through different legal mechanisms, but Congress's rider specifically blocks alterations to the NIH overhead policy. Any substantively similar policy would face the same legal obstacle. The administration's most viable option is appealing to the Supreme Court. Working with Congress to repeal the protective rider seems essentially impossible given current political dynamics and bipartisan interest in maintaining research funding.

What does this decision mean for other research funding policies?

The decision reinforces that Congress controls federal spending and agencies cannot unilaterally override Congressional restrictions. This principle applies broadly across government. It means agencies must follow established procedures, cannot implement major changes without notice and comment, and must respect Congressional limitations on their authority. Future administrations—regardless of political party—would face similar legal constraints when trying to override Congressional spending decisions.

Key Takeaways

This appeals court decision represents a significant victory for research universities and the American research enterprise. The court unanimously rejected the Trump administration's attempt to slash indirect research cost reimbursements, finding that Congress had explicitly prohibited exactly this action. While the administration can appeal to the Supreme Court, the outcome remains uncertain—though the court's reasoning about Congressional authority is based on well-established constitutional principles. For universities, the decision provides stability for long-term planning, though they should prepare for continued political uncertainty around research funding. The case illustrates fundamental principles about how government power is supposed to work: Congress controls the purse, agencies implement Congressional decisions, and the executive branch cannot arbitrarily override legislative intent. Whether the Supreme Court will ultimately affirm or overturn this reasoning will likely be determined within the next 12-18 months.

![Appeals Court Blocks Trump's Research Funding Cuts: What It Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/appeals-court-blocks-trump-s-research-funding-cuts-what-it-m/image-1-1767724814066.jpg)